Author Summary

Humans do not rely on pheromones to recognize the sex of others. Unlike animals that depend on chemical signals, humans develop sex recognition through hearing and vision, starting with the voice. Fetuses hear voices before birth, infants show early brain responses to voices, and children learn to match voice with visual cues. During puberty, sex hormones reorganize deep brain circuits that motivate sexual behavior, linking voice and vision to the hypothalamus. This developmental pathway: hearing and seeing -> subcortical activation, forms a natural learning system for sex recognition. This article proposes a new model showing that the human voice provides the first and most reliable cue for identifying sex, offering a testable alternative to pheromone-based theories.

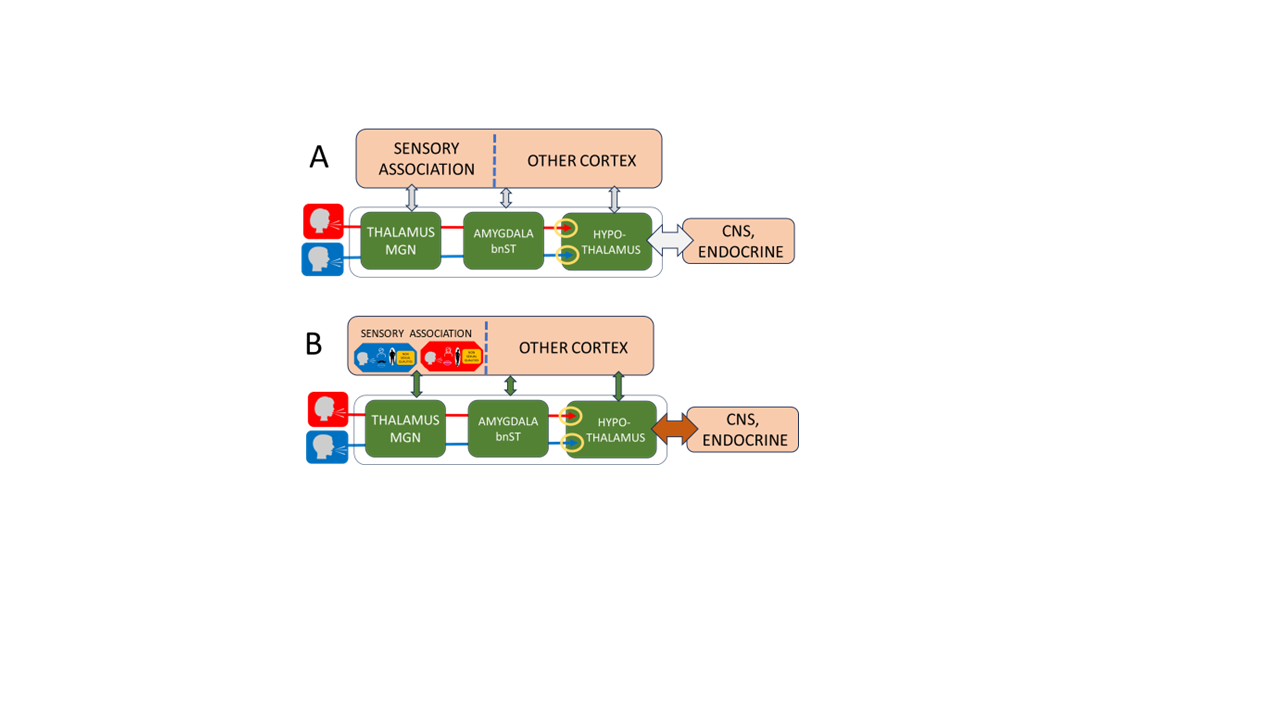

Figure 1. Pheromone-based models propose that putative chemical cues are detected by the main olfactory epithelium and influence hypothalamic activity. However, the absence of a functional vomeronasal organ, pseudogenization of vomeronasal receptor genes, and the lack of any identified human sex pheromone reduce the biological plausibility of this pathway; reported effects on mate choice are weak and inconsistent. By contrast, the Human Sex Recognition (HSR) model emphasizes a developmental auditory–visual pathway.

A. Innate network. Innate auditory mechanisms distinguish male and female voices and relay this information through partially separate subcortical pathways that include the medial geniculate nucleus (MGN), amygdala, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), ultimately reaching hypothalamic regions that regulate sexual behavior (yellow circles). Neurons in these pathways connect with additional subcortical and cortical systems. Many of these connections are plastic and are modified by associative learning (vertical arrows).

B. Developmental integration. During childhood, associations form between auditory and visual cues corresponding to the speaker’s sex. These cross-modal associations emerge first in sensory association cortex and later extend into broader cortical networks (green vertical arrows). During this period, both the hypothalamic–gonadal axis and the neural circuits linking sensory pathways to the developing sexual system are immature, and sexual behavior is not expressed. At puberty, gonadal hormones restructure connections between the hypothalamus, CNS, and reproductive organs (brown arrow), enabling sexual motivation and behavior to emerge.

Overview

Human sex recognition is an effortless and universal human ability, yet the biological and developmental mechanisms that support it remain incompletely characterized. Research on pheromonal signaling in rodents and other nonhuman mammals has been instrumental in establishing core principles of sex recognition, social communication, and neural specialization across species, and has strongly influenced hypotheses about human sex recognition. On this basis, pheromonal cues have often been assumed to play a central role in humans, shaping interpretations of a limited set of behavioral and olfactory findings.

In humans, however, no specific sex pheromone has been identified, and the anatomical and genetic systems that mediate pheromonal communication in many nonhuman mammals—such as a functional vomeronasal organ and intact vomeronasal receptor families—are vestigial or absent. These human-specific biological constraints suggest that pheromonal mechanisms alone may be insufficient to account for the robustness, early emergence, and developmental continuity of human sex recognition, motivating the consideration of additional mechanisms grounded in human sensory access and neural development.

The Human Sex Recognition (HSR) model addresses this gap by proposing that the human voice serves as the earliest and most reliable biological cue to sex. In this account, infants exhibit early sensitivity to vocal signals, and children readily acquire stable auditory–visual associations linking sex-typical voices with corresponding visual features well before the onset of sexual behavior. At puberty, hormonal and neurodevelopmental changes reorganize hypothalamic and limbic pathways involved in motivation and affect, conferring new motivational significance on associations learned during earlier developmental stages. This developmental sequence—early auditory access, cross-modal learning in childhood, and pubertal neural remodeling—forms the core structure of the HSR model.

This manuscript has two aims. First, it presents the structure and developmental foundations of the HSR model and situates it within the broader context of human sensory, cognitive, and neural development. Second, it evaluates empirical and biological evidence relevant to human sex recognition and examines how the HSR framework complements pheromone-based sex recognition (HPSR) models by incorporating mechanisms well established in animal research while addressing domains in which pheromonal explanations are comparatively weak in humans. Although no new empirical data are introduced, the synthesis highlights systematic differences in the scope, effect sizes, and biological plausibility of the supporting evidence. Part I presents the theoretical and developmental formulation of the HSR model, and Part II examines comparative empirical findings and the biological constraints relevant to pheromone-based accounts.

1. Introduction

Origins and Evolution of the Model

The Human Sex Recognition (HSR) model represents the most recent iteration of a theoretical framework developed over more than a decade to account for the biological and developmental foundations of human sex recognition. The earliest formulation (Salu, 2011) proposed that the human voice functions as a primary innate biological cue, serving as nature’s agent for anchoring associations with other sensory inputs—particularly visual signals—during development. That work emphasized the role of prenatal auditory exposure and early postnatal learning in preparing later sexual behavior.

A subsequent refinement (Salu, 2020) focused on the contribution of subcortical structures to sexual development, highlighting the role of the medial geniculate nucleus (MGN), amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), and hypothalamus in shaping sexual orientation and the expression of sexual motivation. This work emphasized the interaction between early sensory learning and later hormonal modulation of motivational circuits.

The present HSR framework integrates these earlier formulations within a unified developmental trajectory, informed by contemporary findings on cortical–subcortical interactions, multisensory learning, and neuroendocrine maturation. Rather than proposing a single moment of sex recognition, the model describes a staged process in which early sensory access, experience-dependent learning, and pubertal neural reorganization interact to produce the robust and automatic capacity for sex recognition observed in humans.

AI-based language tools were used to assist with editorial clarity but did not contribute to the scientific content or theoretical development of the model.

2. Developmental Architecture of Human Sex Recognition

Prenatal foundations

The HSR model begins prenatally, when auditory exposure establishes the earliest biological substrate for sex recognition. By late gestation, the fetal auditory system is sufficiently mature to process external sounds, including speech. Fetuses demonstrate sensitivity to speech rhythms, discriminate sounds by pitch, and distinguish familiar from unfamiliar voices (Kisilevsky et al., 2003; Kisilevsky et al., 2009). Neurophysiological evidence confirms that the auditory pathway is functional during late gestation and responsive to external voices (Chelli & Chanoufi, 2008).

These findings suggest that the auditory system is primed before birth to encode sex-differentiated vocal features, such as pitch, timbre, and prosody. Importantly, this exposure occurs before the maturation of visual systems and long before the emergence of sexual behavior, positioning auditory cues as the earliest available scaffold for later sex recognition.

Auditory scaffold in infancy

Immediately after birth, infants exhibit specialized neural responses to voices. Neuroimaging studies show selective activation to vocal stimuli in early infancy (Grossmann et al., 2010), with evidence of voice-selective cortical processing by four months of age (Calce et al., 2024). By approximately 4–5 months, infants can discriminate between unfamiliar voices and reliably differentiate female voices (Yu et al., 2024).

These findings indicate that voice processing is not only present early but functionally specialized. Within the HSR model, the voice serves as the primary recognition axis during infancy, providing a stable and continuously available cue that can be accessed without visual attention, motor coordination, or explicit learning strategies.

Childhood cross-modal learning

As visual systems mature during infancy and early childhood, auditory information becomes increasingly integrated with visual cues. Cortical regions involved in face and biological motion processing—such as the fusiform face area (FFA), superior temporal sulcus (STS), and occipitotemporal cortex—support the binding of auditory and visual features into stable multimodal representations.

Empirical studies show that infants and young children can match voices to faces by sex (Richoz et al., 2017), and by the end of the first year of life, they integrate vocal cues with biological motion and body form (Johnson et al., 2021). In some contexts, vocal information may even outweigh visual cues for social judgments (Blasi et al., 2023). These findings support the view that sex recognition in childhood is not tied to a single modality but emerges from experience-dependent cross-modal learning organized around an early auditory scaffold.

Within the HSR framework, this period is critical for establishing durable associations between voices and sex-typical visual features. These associations are formed well before sexual motivation emerges and are shaped by extensive real-life exposure rather than explicit instruction.

Pubertal expansion and motivational reorganization

Puberty introduces a major transformation in the functional significance of previously learned sensory associations. Gonadal hormones reorganize hypothalamic and limbic circuits involved in motivation, affect, and social behavior (Sisk & Zehr, 2005). In parallel, the human voice undergoes pronounced pubertal changes, increasing its salience as a sex-differentiated cue (Salu, 2011). These changes are universal and perceptually obvious, requiring no specialized instrumentation to detect.

Beyond these salient changes, acoustic analyses reveal that subtler sex-related differences in vocal parameters emerge gradually between approximately 5 and 15 years of age, allowing reliable classification of a child’s sex from speech alone (Chen et al., 2022). Neuroimaging evidence further indicates that adolescents show increased hypothalamic responsiveness to visual sex cues compared to children, reflecting a developmental shift in motivational weighting across modalities (Nowling et al., 2024).

Within the HSR model, puberty does not initiate sex recognition but reorganizes its motivational significance. Associations established earlier through auditory–visual learning are now integrated into hypothalamic–limbic circuits, supporting sexual attraction, orientation, and behavior.

3. Complementary Evaluation of Human Sex Recognition Models

Research on pheromonal signaling has played a foundational role in elucidating sex recognition and social communication in nonhuman mammals, providing a rich empirical framework for understanding how biologically relevant cues can guide development and behavior. These findings have naturally informed hypotheses about human sex recognition, leading to models that emphasize chemosensory mechanisms as potential contributors to human sexual development.

In humans, several studies have reported hypothalamic activation in response to putative chemosignals such as androstadienone and estratetraenol (Savic et al., 2001; Savic & Lindström, 2008). These findings suggest that chemosensory inputs may influence neural systems involved in arousal, affect, or social evaluation. However, behavioral effects associated with these compounds are variable, context-dependent, and not consistently linked to explicit sex recognition. Moreover, no universal human sex pheromone has been identified, and the developmental role of chemosensory cues in early sex recognition remains unclear.

The HSR model addresses these limitations by focusing on sensory channels that are developmentally accessible from the prenatal period onward and that support continuous, high-fidelity learning through real-world exposure. Rather than rejecting pheromonal mechanisms, the HSR framework incorporates insights from animal research while proposing that, in humans, auditory and visual cues constitute the primary scaffolding for sex recognition, with chemosensory influences acting, at most, as modulators of affect or motivation.

4. Scientific Criteria and Model Evaluation

A useful scientific model must be biologically feasible, developmentally grounded, and empirically falsifiable. The HSR model satisfies these criteria by generating specific predictions tied to sensory access, neural development, and learning history.

Because the model is grounded in well-characterized developmental processes—prenatal auditory sensitivity, infant voice selectivity, cross-modal learning, and pubertal neuroendocrine reorganization—it yields predictions that can be tested using established behavioral, neuroimaging, and developmental methods. Importantly, the model predicts differential outcomes under sensory deprivation conditions, allowing it to be empirically distinguished from models that emphasize chemosensory primacy.

By contrast, pheromone-based models in humans face greater challenges in specifying developmental mechanisms, identifying invariant stimuli, and generating clear falsifiable predictions about early sex recognition. This difference does not diminish the importance of pheromonal research in animals, but it highlights the need for models that reflect human-specific sensory ecology and developmental trajectories.

5. Predictions and Testable Hypotheses

The HSR model generates a set of empirically testable predictions:

-

Developmental timing

Children should reliably classify sex by voice earlier than by face, reflecting earlier auditory access and learning.

-

Sensory deprivation

Congenital or early auditory deprivation should impair the development of sex recognition more strongly than olfactory impairment.

-

Pubertal reorganization

Adolescents should exhibit increased hypothalamic and limbic responsiveness to visual sex cues compared to children, reflecting the integration of earlier learned associations into motivational circuits.

-

Chemosensory predictions

If pheromone-based models are correct, olfactory deprivation should directly impair sex recognition from auditory or visual cues. Although anosmia and smell loss are associated with changes in sexual behavior, intimacy, or mood (Croy et al., 2013; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2020), no studies to date demonstrate a direct impairment in voice- or face-based sex recognition in individuals with olfactory deficits.

-

Neural pathway differentiation

The HSR model predicts that male and female voices may engage partially distinct neural pathways from the medial geniculate nucleus (MGN) to hypothalamic and limbic structures, with possible overlap. Existing neuroimaging studies already demonstrate sex-differentiated cortical processing of voices, including tonotopic organization (Talavage et al., 2004), hemispheric asymmetries (Lattner et al., 2004), sex-specific voice activations (Sokhi et al., 2005), gender-sensitive processing (Charest et al., 2012), and distinct representations of pitch and timbre (Allen et al., 2016). These approaches could be extended to test subcortical pathway differentiation predicted by the HSR framework.

6. Chemosensory Influences in Humans: A Modulatory Role

Some authors have argued that, even in the absence of a functional vomeronasal organ, humans may process socially relevant chemosignals via the main olfactory system (Herz & Inzlicht, 2014). Such signals may influence bonding, stress responses, or emotional context. Within the HSR framework, these effects are fully compatible with a modulatory role for chemosensory inputs.

However, as emphasized by Trotier (2011), human sexuality involves a complex integration of psychological, cognitive, and social processes that extend beyond the pheromonal mechanisms governing mate recognition in many nonhuman species. From this perspective, chemosensory cues may shape emotional tone or arousal but are unlikely to function as primary recognition mechanisms for sex in humans.

7. Biological Feasibility and Comparative Perspective

Biological feasibility is a critical criterion for evaluating any model of human behavior. The HSR model aligns with comparative evidence across vertebrates, where auditory signals—such as song in birds or calls in amphibians—often play a central role in sex recognition. These parallels suggest that reliance on acoustic cues for sex recognition is evolutionarily conserved and biologically parsimonious.

In humans, pubertal voice changes driven by sex hormones further underscore the biological preparation of vocal cues for recognizing sexually mature individuals. Visual cues may provide redundant or complementary information, enhancing robustness. Together, these features support the biological plausibility of the HSR model while remaining consistent with insights derived from animal research on communication and recognition.

8. Interpreting Effect Size, Sample Scale, and Error Bounds

The comparison summarized in Table X relies on effect size rather than statistical significance alone. In particular, the h statistic is used as a standardized measure of the magnitude of a difference between proportions, independent of sample size. This distinction is important because statistical significance can be achieved with small effects in small samples, while effect size reflects the practical and perceptual strength of a phenomenon.

In studies of putative human chemosignals, reported effects are typically modest and derived from relatively small, laboratory-based samples. As a result, confidence intervals remain wide, and replication across contexts has been inconsistent. By contrast, the Human Sex Recognition (HSR) model is supported by developmental phenomena that are expressed continuously across everyday human interaction, beginning in infancy and extending across the lifespan. These include voice-based sex classification, cross-modal voice–face matching, and pubertal vocal differentiation, all of which are observed repeatedly across cultures and contexts.

Although these observations are not derived from a single experimental dataset, their effective sample size is extraordinarily large, encompassing countless naturalistic exposures accumulated over development. From a statistical perspective, such massive observational scale substantially constrains plausible error ranges, even when individual experimental effect sizes are moderate. This distinction between limited laboratory sampling and pervasive real-world exposure is central to evaluating the relative robustness of competing models.

Accordingly, the comparison in Table X should not be interpreted as a contest between isolated experiments, but as a contrast between narrowly sampled effects and developmentally entrenched phenomena whose reliability is supported by scale, consistency, and biological plausibility.

9. Conclusion

Human sex recognition emerges from a developmental trajectory organized around an auditory–visual–subcortical axis. Prenatal and early postnatal exposure to voices provides the initial scaffold; childhood experience supports cross-modal learning; and pubertal neuroendocrine changes reorganize motivational circuits that confer sexual significance on earlier learned associations.

The HSR model integrates mechanisms corroborated by pheromonal research while proposing additional developmental processes that address domains in which pheromonal explanations are comparatively weak in humans. By generating falsifiable predictions and grounding sex recognition in human-specific sensory access and neural development, the HSR framework offers a complementary and biologically grounded account of the human sex instinct.

Comparison of evidence supporting voice-based human sex recognition (HSR) and pheromone-based sex recognition (HPSR), considering effect size (h), experimental sample size, effective observational scale, ecological context, and biological plausibility. Effect size estimates reflect representative magnitudes reported in the literature for sex classification or sex-linked neural responses, rather than pooled meta-analytic estimates.

The comparison summarized in

Table 1 emphasizes effect size and inferential robustness rather than statistical significance alone. Cohen’s

h is reported as a standardized measure of the magnitude of differences in classification performance, independent of sample size. This distinction is critical because statistically significant results may reflect small effects in limited samples, whereas effect size provides a more direct indication of perceptual and behavioral reliability.

In studies supporting pheromone-based accounts, effects are typically derived from laboratory paradigms involving instructed sniffing of isolated chemosensory samples in relatively small participant groups. These methods are well suited for detecting subtle physiological or affective modulation under controlled conditions but necessarily abstract chemosensory cues from the multisensory and social environments in which human sex recognition normally occurs. As a result, confidence intervals remain wide and replication across contexts has been variable.

By contrast, the HSR model is supported by phenomena that operate continuously in naturalistic settings, including voice-based sex classification, cross-modal voice–face matching, and developmentally embedded learning beginning in infancy. Although individual experimental studies may involve modest sample sizes, the effective observational scale is extremely large due to the accumulation of real-world exposure across development. From an inferential perspective, such scale substantially constrains plausible error ranges, even when individual experimental effect sizes are moderate.

Accordingly, the comparison in Table X should be interpreted not as a contest between isolated experiments, but as a contrast between episodic laboratory effects and developmentally entrenched mechanisms whose reliability is supported by scale, consistency, and biological plausibility.

Note on effect size estimates.

Cohen’s h values are reported as approximate ranges intended to convey the typical magnitude of differences observed in voice-based versus chemosensory paradigms relevant to human sex recognition. For HSR, h values in the large to very large range (h ≈ 1.1–1.3) are consistent with reported classification accuracies of ~90–98% for voice-based sex identification across languages and contexts, relative to chance performance. For HPSR, h values in the very small range (h ≈ 0.05–0.25) reflect modest deviations from chance commonly reported in laboratory studies examining behavioral or neural responses to isolated chemosensory compounds (e.g., hypothalamic activation or forced-choice judgments), rather than explicit sex classification performance. These ranges are illustrative of relative effect magnitude and robustness, not formal pooled estimates.

AI Assistance Disclosure

The author used AI-based language tools to assist with editing, restructuring, and clarity of presentation. All scientific content, theoretical framework, interpretations, and conclusions are the author’s own and are based on prior published work and cited empirical literature.

References

- Allen, E.J.; Burton, P.C.; Olman, C.A.; Oxenham, A.J. Representations of pitch and timbre variation in human auditory cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 2016, 37, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin, P.; Zatorre, R.; Ahad, P. Human temporal-lobe regions sensitive to voice. Nature Neuroscience 2002, 5, 965–970. [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, C.H.; et al. Young children’s attributes are better conveyed by voices than by faces. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calce, R.P.; et al. Voice categorization in the four-month-old human brain. Current Biology 2024, 34, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, S.; Belin, P. Integrating face and voice in person perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2007, 11, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charest, I.; Pernet, C.; Latinus, M.; Crabbe, F.; Belin, P. Cerebral processing of voice gender studied using a continuous carryover fMRI design. Cerebral Cortex 2012, 23, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelli, D.; Chanoufi, B. Fetal audition: Myth or reality? Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction 2008, 37, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Togneri, R.; Maybery, M.; Tan, T. Automated sex classification of children’s voices and changes in differentiating factors with age. arXiv. 2022. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.13112.

- Croy, I.; Bojanowski, V.; Hummel, T. Men without a sense of smell exhibit a strongly reduced number of sexual relationships, women exhibit reduced partnership security – a reanalysis of previously published data. Biological Psychology 2013, 92, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCasper, A.J.; Fifer, W. Of human bonding: Newborns prefer their mother’s voice. Science 1980, 208, 1174–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCasper, A.J.; Spence, M.J. Prenatal maternal speech influences newborn listening preferences. Infant Behavior and Development 1986, 9, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulac, C.; Torello, A.T. Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2003, 4, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, M.; Johnson, S. Early developmental differences in voice and face recognition. Developmental Science 2013, 16, 739–748. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, T.; Oberecker, R.; Koch, S.P.; Friederici, A.D. The developmental origins of voice processing in the human brain. Neuron 2010, 65, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S.; Inzlicht, M. Sex differences in response to physical and social cues: A review. Hormones and Behavior 2014, 66, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, J.; Getty, L.A.; Clark, M.J.; Wheeler, K. Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 97 1995, 3099–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummer, T.A.; McClintock, M.K. Putative human pheromones and their effects on attention. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34 2009, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, S.; et al. Androstadienone modulates women’s mood and cortisol. Journal of Neuroscience 2002, 22, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.P.; Dong, M.; Ogren, M.; Senturk, D. Infants’ identification of gender in biological motion displays. Infancy 2021, 26, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisilevsky, B.S.; et al. Effects of experience on fetal voice recognition. Psychological Science 2003, 14, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisilevsky, B.; et al. Fetal sensitivity to properties of maternal speech and language. Infant Behavior and Development 2009, 32, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattner, S.; Meyer, M.E.; Friederici, A.D. Voice perception: Sex, pitch, and the right h Lecanuet, J.P.; Schaal, B. (1996). Fetal sensory competencies. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology;emisphere. Human Brain Mapping 2004, 68 24, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, M. Human vomeronasal organ: Vestigial or functional? Chemical Senses 2001, 26, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowling, D.; et al. Sex differences in development of functional connections in the face processing network. NeuroImage 2024, 283, 120384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszkiewicz, A.; et al. Consequences of undetected olfactory loss for human romantic and sexual activity. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2020, 49, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, C.R.; McAleer, P.; Latinus, M.; et al. The human voice areas: Anatomical and functional organization. Cerebral Cortex 25 2015, 4656–4669. [Google Scholar]

- Richoz, A.R.; et al. Audio-visual perception of gender by infants emerges earlier for female than male faces. Frontiers in Psychology 2017, 8, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Salu, Y. The roots of sexual arousal and sexual orientation. Medical Hypotheses 2011, 76, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salu, Y. Nature controls nurture in the development of sexual orientation, and voice is nature’s agent. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, I.; Berglund, H.; Gulyas, B.; Roland, P. Smelling of odorous sex hormone-like compounds causes sex-differentiated hypothalamic activations. Neuron 2001, 31, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, I.; Lindström, P. PET and MRI show differences in cerebral asymmetry and functional connectivity between homosexual and heterosexual subjects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 2008, 105, 9403–9408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, T.K.; Lyndon, A.; Little, A.C.; Roberts, S.C. Evidence for sex pheromones in humans? Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275 2008, 2723–2729. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk, C.L.; Zehr, J.L. Pubertal hormones organize the adolescent brain and behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 2005, 26, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokhi, D.S.; Hunter, M.D.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Woodruff, P.W.R. Male and female voices activate distinct regions in the male brain. NeuroImage 2005, 27, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talavage, T.M.; Sereno, M.I.; Melcher, J.R.; Ledden, P.J.; Rosen, B.R.; Dale, A.M. Tonotopic organization in human auditory cortex revealed by progressions of frequency sensitivity. Journal of Neurophysiology 2004, 91, 1282–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotier, D. Vomeronasal organ and human pheromones. European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases 2011, 128, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.E.; Johnson, T.J.; Fecher, N. Learning to identify talkers: Do 4.5-month-old infants recognize unfamiliar female talkers? JASA Express Letters 2024, 4, 015203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).