1. Introduction

Bacterial pathogenesis is a multifactorial process governed by an intricate network of biochemical pathways, structural adaptations, and host–pathogen interactions [

1]

. Among the most critical components driving bacterial virulence are metalloproteins, which mediate essential cellular functions including oxidative stress response, enzymatic catalysis, nutrient acquisition, and signaling [

2]

. The dependence of pathogens on metal ions such as zinc, iron, and manganese not only underpins their metabolic and structural integrity but also defines key vulnerabilities that can be exploited therapeutically [

3]

.

Despite the availability of numerous antibiotics, the global rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) underscores the urgent need for new therapeutic paradigms [

4]

. Traditional antibiotics predominantly target bacterial cell wall synthesis, protein synthesis, or nucleic acid replication. However, bacterial adaptation and the evolution of resistance have significantly reduced their long-term efficacy [

5]

. In this context, metalloproteins and their associated metal homeostasis systems represent promising yet underexplored targets for antimicrobial intervention. Understanding the structural and mechanistic roles of these proteins can enable the development of drugs that precisely disrupt bacterial survival mechanisms while minimizing off-target toxicity [

6]

.

This review aims to synthesize current insights into the mechanistic roles of bacterial metalloproteins, highlighting their functional significance in pathogenesis and summarizing key findings that demonstrate how these discoveries inform the design of next-generation antibacterial strategies. Specifically, we emphasize the translational potential of siderophore–antibiotic conjugates, metal trafficking inhibitors, and catalytic metallodrugs as promising approaches to combat antimicrobial resistance. By linking structural biology, biochemical function, and therapeutic innovation, we provide a comprehensive framework for exploiting metalloprotein systems as precision targets in combating multidrug-resistant infections [

7]

.

Entries summarized in tables and figures were identified through structured searches of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science conducted between 2005 and 2025. Keywords included “NDM-1 inhibitors,” “siderophore analogs,” “metal chelators,” “metalloprotein inhibitors,” and “allosteric binders.” Only peer-reviewed articles published in English were considered. Studies were included if they provided mechanistic detail on bacterial metalloprotein function, therapeutic targeting, or translational potential. Exclusion criteria comprised non-peer-reviewed sources, conference abstracts without full data, and reports lacking mechanistic evidence. This systematic approach ensured that the evidence presented is transparent, reproducible, and representative of current research.

1.1. Mechanisms of Metalloprotein Targeting in Bacterial Pathogenesis

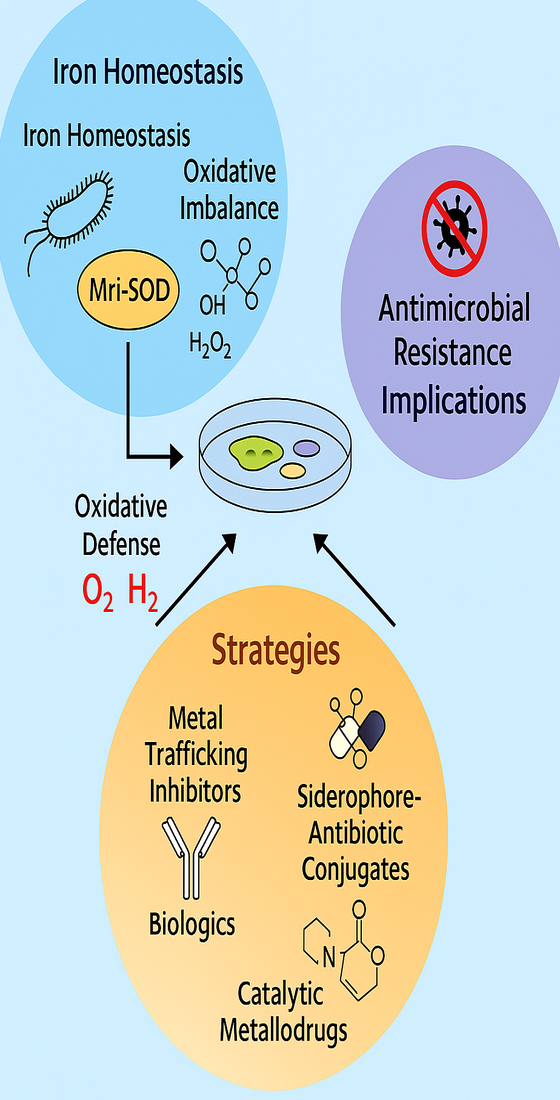

Metalloproteins play indispensable roles in bacterial survival and virulence. Their contribution to pathogenesis can be categorized into four main mechanisms (Figure 1):

1.1.1. Oxidative Stress Response:

Bacterial superoxide dismutases (SODs), particularly those capable of functioning with multiple metal cofactors, play critical roles in pathogen survival under oxidative stress. Staphylococcus aureus, for instance, employs a dual-metal SOD that can function with either iron or manganese, enhancing resistance to host nutritional immunity and calprotectin-mediated metal sequestration [

8].

1.1.2. Enzymatic Activity:

Zinc-dependent enzymes are essential for bacterial DNA replication and repair. Structural studies have shown that zinc coordination is vital for metalloenzyme function, with Choi et al. demonstrating that zinc uptake regulators require binding at three distinct regulatory sites for proper activation [

3]

.

1.1.3. Metal Acquisition Systems:

Bacteria have evolved sophisticated metal uptake systems and metallophores to scavenge essential metal ions from their environment. Acinetobacter baumannii, for example, can use multiple siderophores for iron acquisition, yet only acinetobactin is essential for virulence in infection models [

1,

4]

1.1.4. Host–Pathogen Metal Competition:

The dynamic interplay between bacterial metal acquisition and host-imposed metal restriction defines a critical battleground in infection biology. As demonstrated by Bütof et al., Cupriavidus metallidurans coordinates multiple metal homeostasis systems through an integrated zinc uptake regulon, exemplifying the complexity of bacterial adaptation to metal-limited environments [

5].

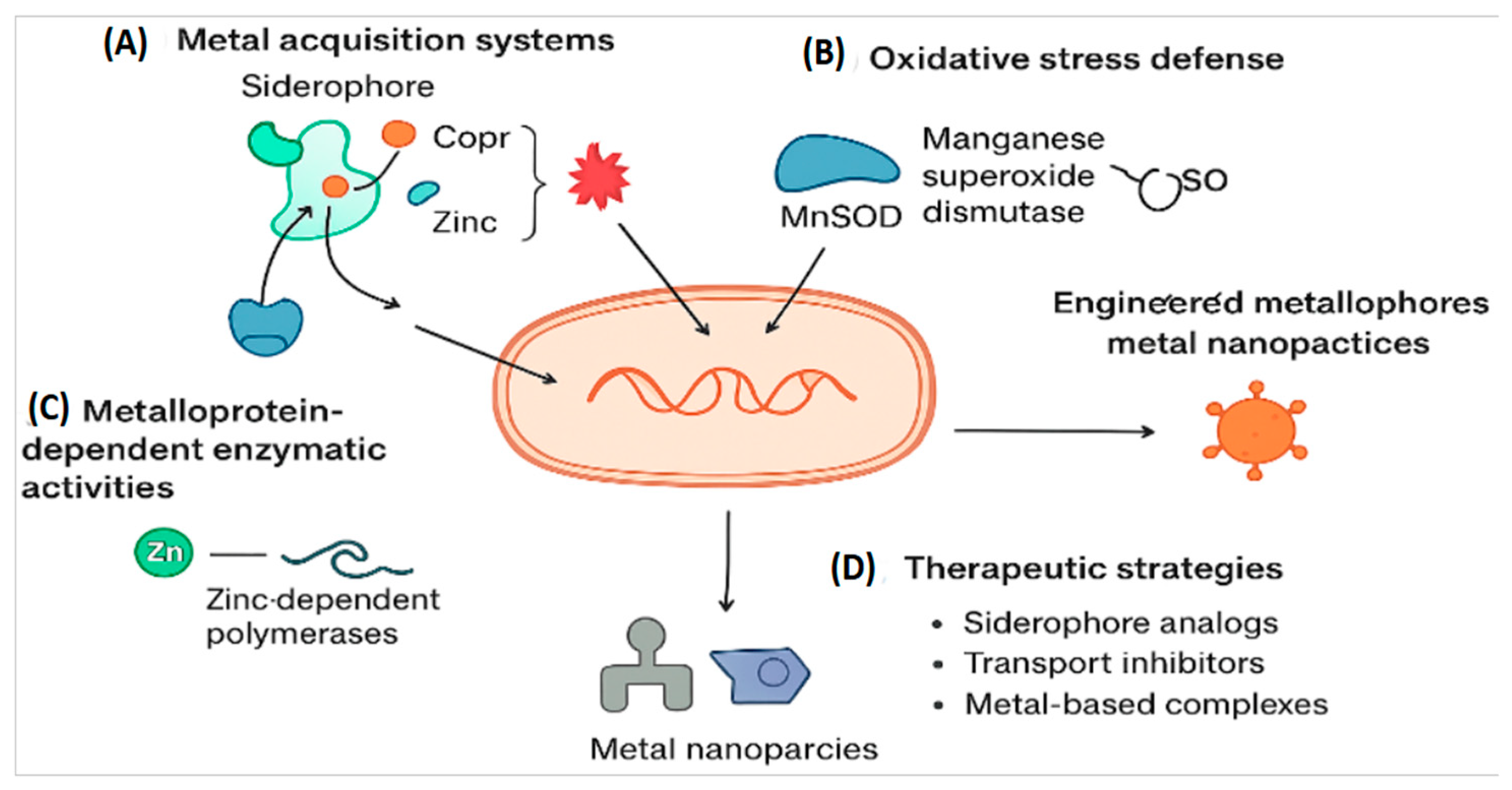

These regulatory mechanisms collectively govern bacterial survival, virulence, and resistance under host-imposed stress. Figure 1 delineates the core mechanistic pathways mediated by metalloproteins, including copper detoxification via Copr operons, oxidative stress defense through manganese- and iron-dependent superoxide dismutases (SODs), siderophore-driven iron acquisition, and zinc-dependent enzymatic functions essential for DNA replication and repair. Figure 2 complements this framework by presenting a comparative overview of therapeutic strategies designed to disrupt metalloprotein activity in pathogenic bacteria. These include iron chelation, siderophore mimicry, enzymatic inhibition, and biological neutralization—each tailored to interfere with metal-dependent processes critical for bacterial fitness.

Among these targets, New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1)—a clinically significant zinc-dependent enzyme—has emerged as a key focus for inhibitor development due to its broad-spectrum β-lactam hydrolysis and its role in carbapenem resistance [

9,

10]

. Recent studies have demonstrated that reversible binding of small-molecule inhibitors, such as OP607 and α-aminophosphonate derivatives, to the zinc-coordinated active site of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) can restore antibiotic efficacy in resistant strains [

11,

12]

. These compounds transiently coordinate the catalytic Zn²⁺ ions without permanently altering the enzyme structure, thereby enabling selective inhibition while minimizing off-target effects [

13]

. This reversible interaction competitively blocks access of β-lactam antibiotics to the active site, allowing these agents to retain antibacterial activity even in the presence of resistance determinants. For instance, NDM-1 hydrolyzes β-lactam antibiotics and serves as a critical resistance determinant in Klebsiella pneumoniae [

9,

10]

, while Mn-SOD protects pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus from host-derived reactive oxygen species. Although mechanistically distinct, these targets share a reliance on metal cofactors, rendering them attractive candidates for selective inhibition strategies.

Notably, reversible inhibitors offer several advantages over irreversible covalent binders: they are less likely to induce compensatory mutations, can be structurally optimized for potency and spectrum, and often exhibit favorable pharmacokinetic profiles. Building on these mechanistic insights, Table 1 summarizes key bacterial metalloproteins implicated in virulence, oxidative stress response, and nutrient acquisition.

1.2. Functional and Therapeutic Implications

Bacterial metalloproteins display remarkable structural diversity yet maintain conserved catalytic domains critical for pathogenesis. Many are structurally distinct from their human counterparts, offering a selective window for drug development with minimal host toxicity [

17] Crystallographic studies, such as those by Šink et al. and Shirakawa et al., have revealed detailed structural and functional insights into essential bacterial metalloenzymes involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis [

9,

18]

. These findings illuminate specific vulnerabilities that can be exploited to design inhibitors that selectively impair bacterial viability without affecting host cells.

However, despite the identification of numerous metalloprotein targets, most clinically approved antibiotics still focus on traditional cellular processes—such as peptidoglycan synthesis, protein synthesis, and DNA replication [

19] . While these targets have historically provided effective treatments, the rise of resistance mechanisms has diminished their long-term efficacy. The global burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), responsible for an estimated 1.27 million deaths annually [

20], demands a paradigm shift toward mechanisms less prone to resistance evolution—such as those involving metal homeostasis and metalloprotein function.

1.3. From Mechanisms to Strategies: Integrating Metalloprotein Insights into Antibacterial Development

Understanding the mechanistic roles of bacterial metalloproteins lays the foundation for designing targeted antibacterial strategies. Since pathogenicity and antimicrobial susceptibility are species-dependent, new approaches must move beyond broad-spectrum antibiotics to focus on precision targeting of virulence mechanisms [

21]. Insights from metalloprotein biology enable such precision by linking molecular function to therapeutic vulnerability.

Current antibiotics can be categorized based on their cellular targets—cell wall synthesis (β-lactams, glycopeptides), membrane disruption (polymyxins, lipopeptides), or interference with intracellular machinery (rifamycins, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines). Yet many of these treatments fail to discriminate between pathogens and commensals, leading to microbiome disruption and secondary complications. Moreover, the overuse of these agents has accelerated the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains.

Modern research emphasizes the need to develop novel therapeutics that target metalloprotein-mediated pathways, either by chelating essential metals, blocking metallophore uptake, or inhibiting metal-dependent enzyme activity. These strategies hold promise for overcoming resistance because they target fundamental physiological processes that are less amenable to genetic bypass. Furthermore, combining metalloprotein inhibitors with existing antibiotics could potentiate efficacy while minimizing dosage requirements and toxicity.

During the golden age of antibiotics (1940–1960), most discoveries originated from natural products; however, microorganisms rapidly evolved resistance [

22] . In contrast, metalloprotein-based approaches represent a new frontier in antimicrobial design—one that integrates structural biology, metal biochemistry, and drug discovery. By exploiting the essential yet vulnerable metal-dependent processes of bacteria, researchers can craft more selective, durable, and effective therapies for the post-antibiotic era.

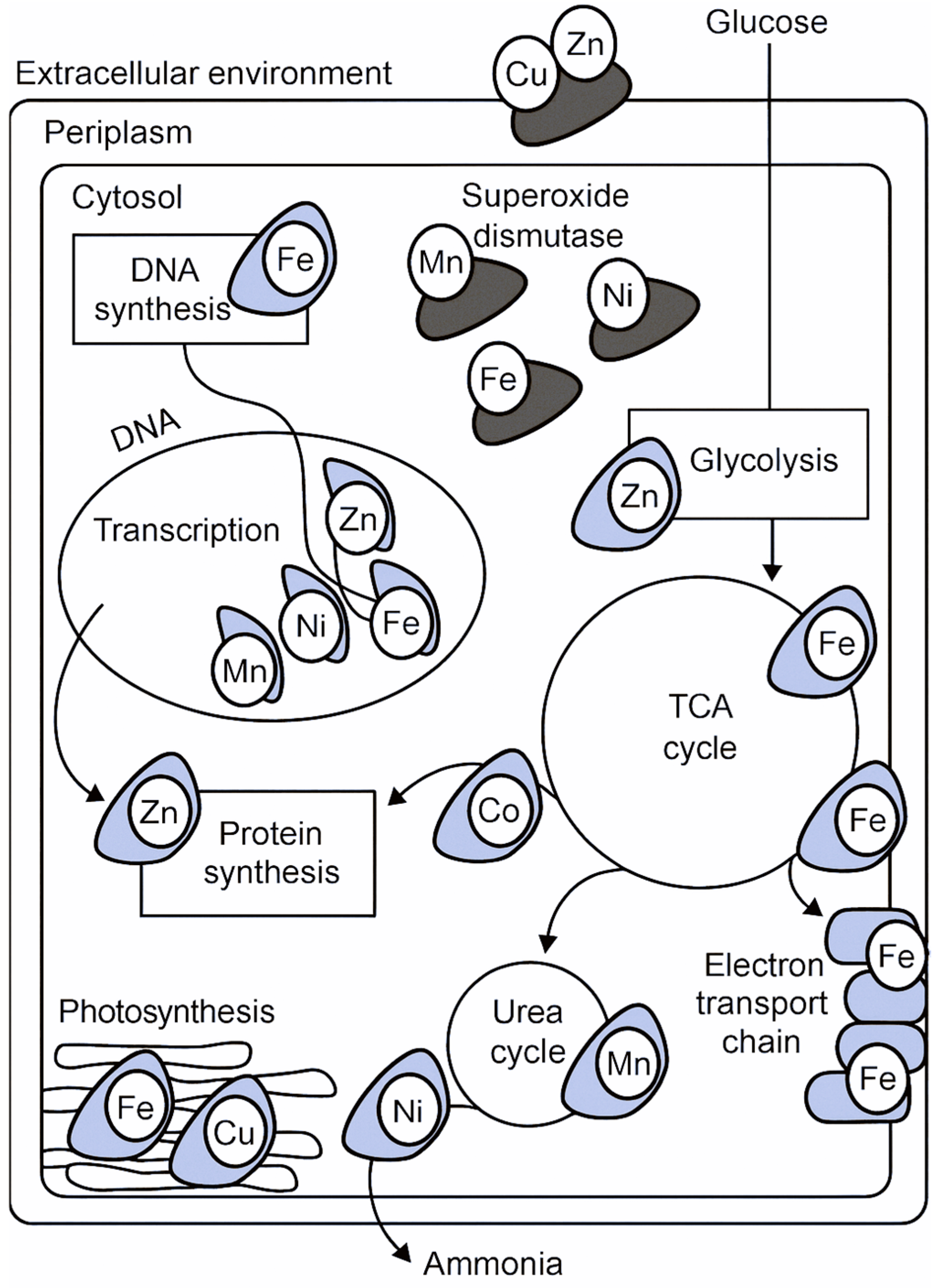

2. Targeting Metal Homeostasis: Experimental Insights

Bacterial metal homeostasis is a finely tuned process that governs the uptake, distribution, and utilization of essential metal ions such as zinc, iron, copper, and manganese. These metals are critical for enzymatic activity, structural stability, and redox regulation. Disrupting this balance presents a promising avenue for antimicrobial development, particularly against multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Recent experimental studies have elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial metal regulation. For example, Colaço et al. characterized Escherichia coli ZinT, a periplasmic protein involved in resistance to toxic metals including cobalt, mercury, and cadmium [

23]

. Their structural analysis revealed specific metal-binding motifs that could serve as templates for designing inhibitors that block metal trafficking or disrupt metalloprotein assembly.

The relationship between metal availability and bacterial virulence has also been extensively investigated. Capdevila et al. demonstrated how pathogens maintain zinc metallostasis at the host–pathogen interface, using regulatory proteins and transport systems to evade host-imposed metal restriction [

24]

. These findings identify key nodes in bacterial metal acquisition that are amenable to therapeutic targeting.

In parallel, host immune responses have evolved to exploit metal toxicity as a defense mechanism. Djoko et al. showed that elevated levels of copper and zinc within phagolysosomes contribute to bacterial killing, highlighting the potential of modulating host metal availability or mimicking these stress conditions pharmacologically [

25]

.

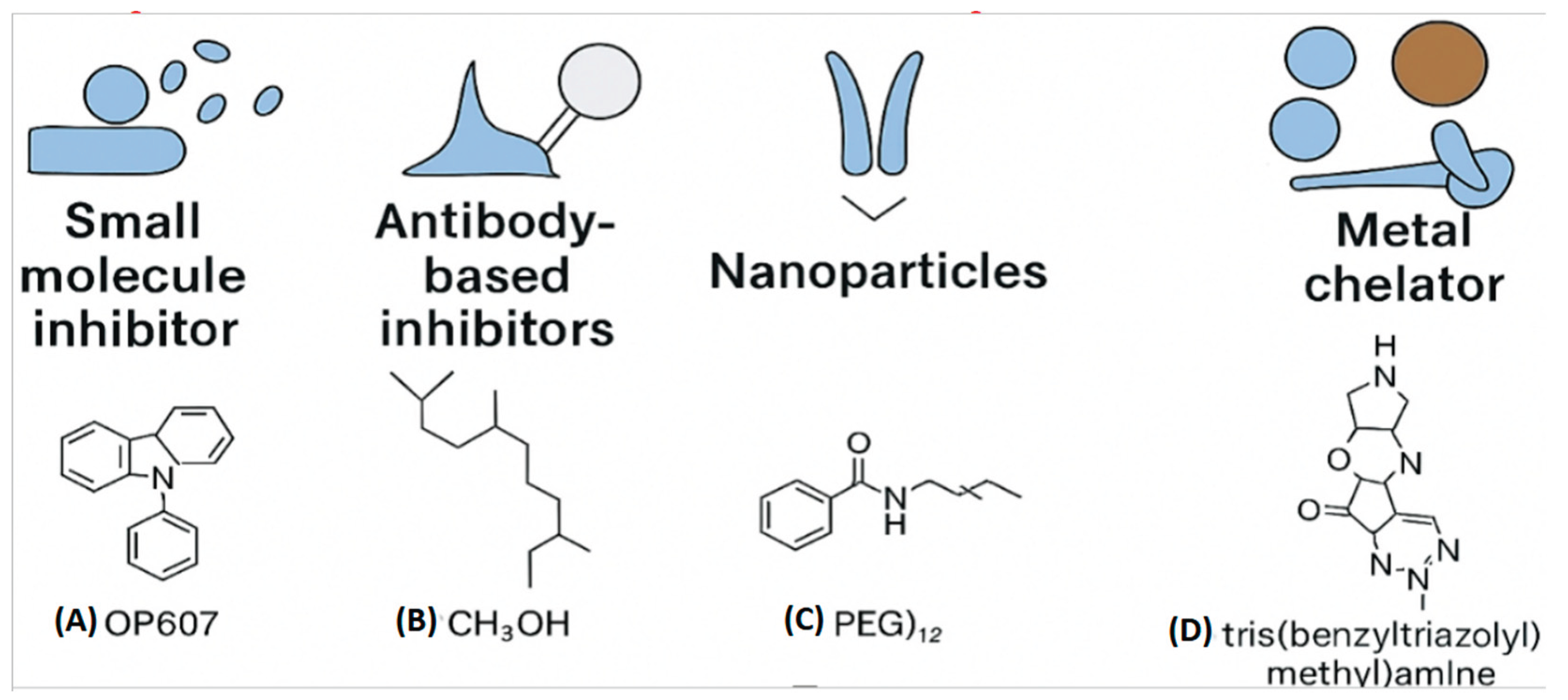

As illustrated in Figure 3, bacterial metal homeostasis integrates membrane transporters (Fe, Zn, Cu, Mn), intracellular trafficking pathways, metallochaperones, and storage proteins. These systems collectively maintain redox balance and enzymatic regulation, while host-imposed metal restriction creates selective pressure that pathogens counteract through specialized uptake and detoxification mechanisms.

Copper contributes indirectly to DNA synthesis by modulating redox homeostasis and nucleotide metabolism. Copper-dependent enzymes influence ribonucleotide reductase activity, which is essential for deoxyribonucleotide production. Dysregulated copper levels can impair DNA replication through oxidative stress and enzyme inhibition [

24,

25]

.

Manganese is a critical cofactor for arginase, the enzyme catalyzing the final step of the urea cycle, thereby regulating nitrogen disposal. Nickel, in turn, is indispensable for bacterial urease, which hydrolyzes urea to ammonia and carbon dioxide, supporting nitrogen metabolism and pathogenic survival in host environments [

23]

.

Integrating these mechanistic insights into the main text helps readers connect biochemical pathways with therapeutic relevance. By clarifying how copper, manganese, and nickel contribute to DNA synthesis and nitrogen metabolism, the review provides a stronger rationale for targeting metalloproteins in antibacterial design. Table 1 complements this by listing representative metalloprotein-targeting agents, including their mechanisms of action, delivery platforms, selectivity profiles, and clinical development stages.

To further guide therapeutic prioritization, Table 2 highlights key bacterial metalloprotein targets and their therapeutic relevance. Notably, Mn-superoxide dismutase in S. aureus emerges as a validated virulence factor, with genetic knockout models confirming its role in oxidative stress resistance. Similarly, iron-siderophore systems in E. coli and S. aureus demonstrate pathogen-specific uptake mechanisms that can be exploited using siderophore analogs or chelators. While copper transport proteins in P. aeruginosa offer unique selectivity, their therapeutic targeting remains challenged by isoform redundancy and host similarity. These insights underscore the need for structure-guided drug design and pathogen-specific delivery platforms.

2.1. Mechanisms of Action

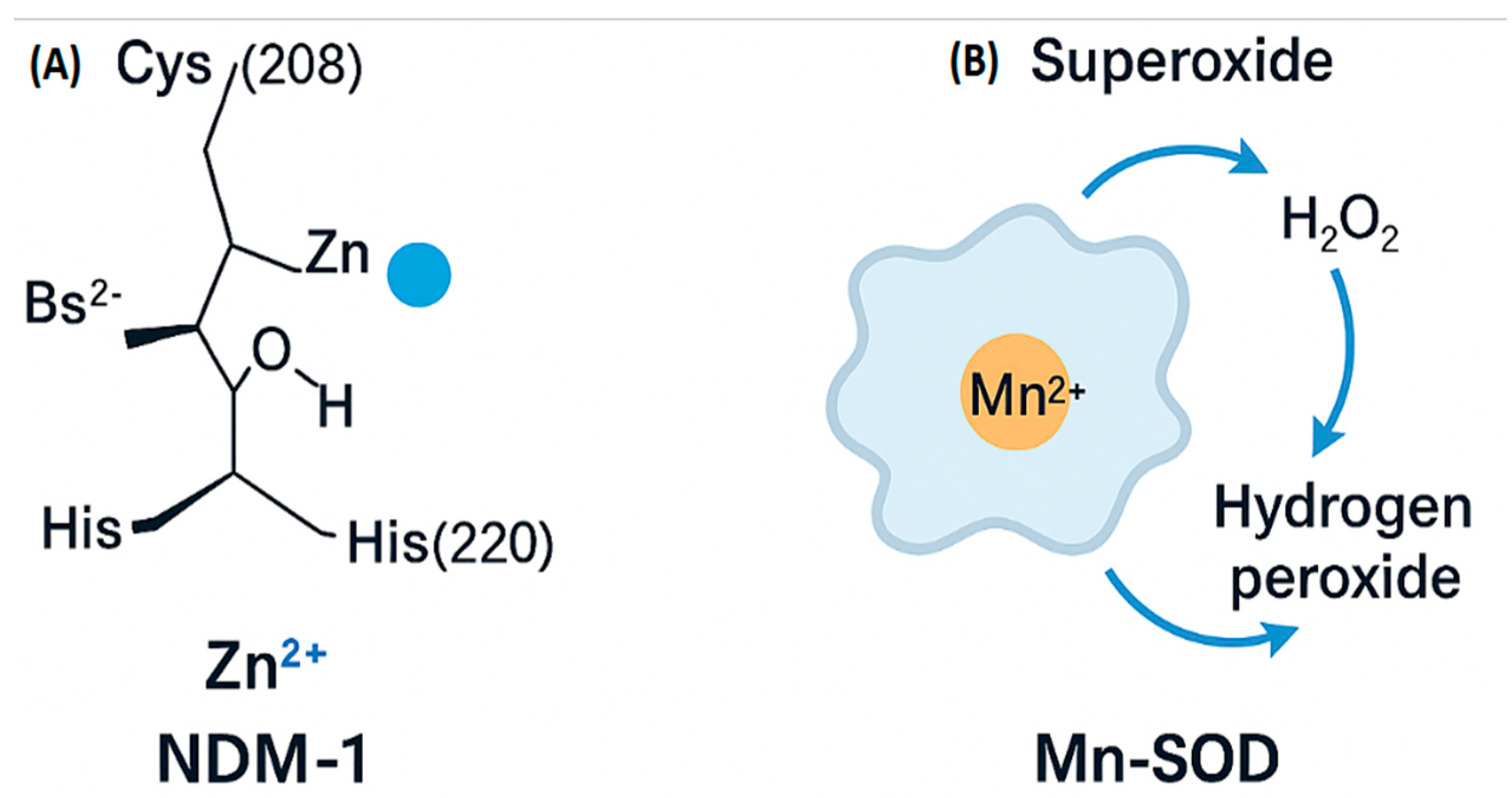

Metalloproteins incorporate essential metal cofactors into their active sites, enabling catalysis of fundamental biochemical reactions. Clinically relevant examples include New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) and Verona Integron-encoded Metallo-β-lactamase-2 (VIM-2), which hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics through zinc-dependent mechanisms, thereby conferring carbapenem resistance [

28,

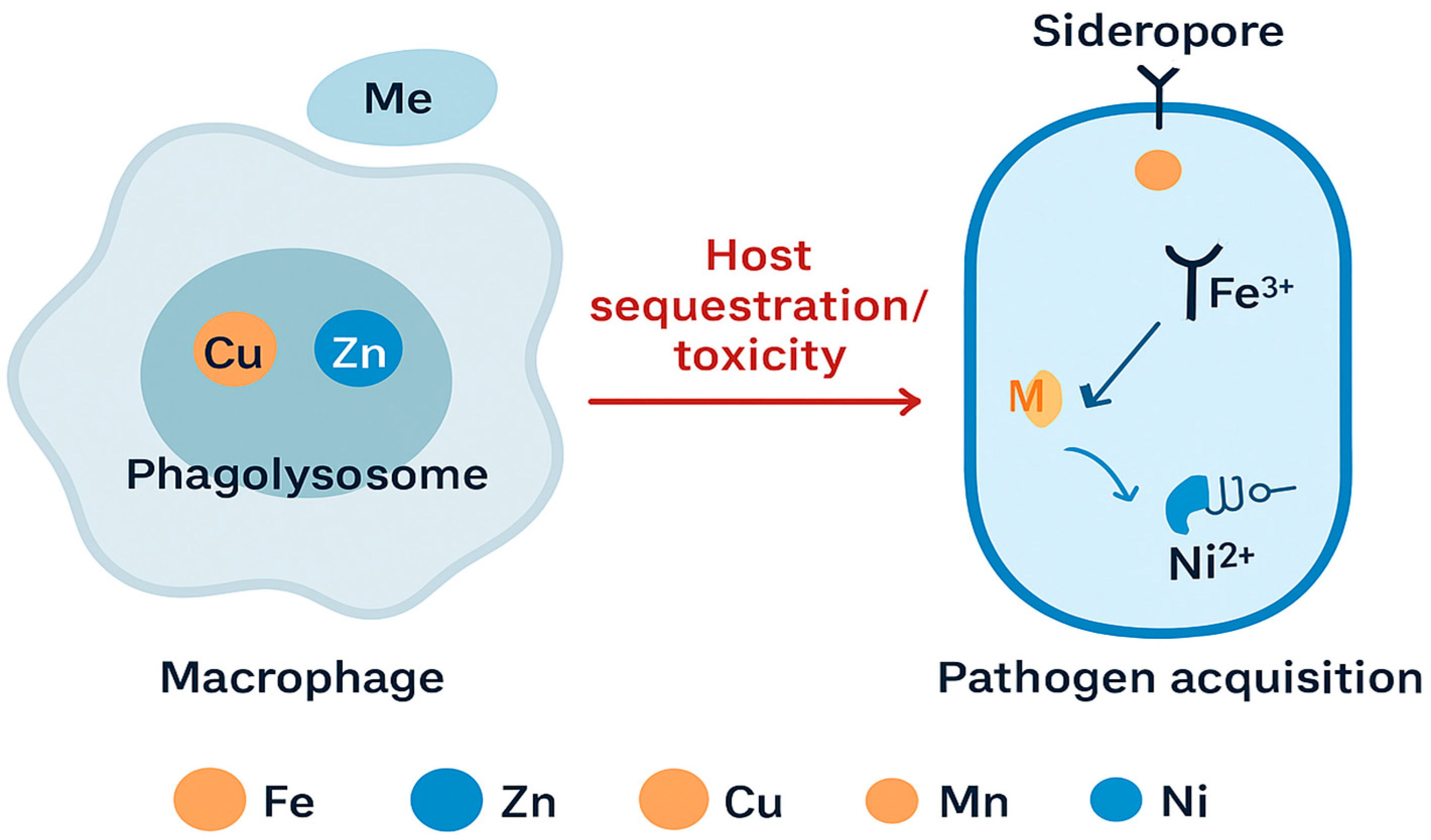

29]. These enzymes rely on precise Zn²⁺ coordination within their catalytic pockets, underscoring how pathogens exploit metal ions for survival. Equally critical is manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), which detoxifies reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protects pathogens from host oxidative stress. The catalytic cycle of Mn-SOD highlights the redox conversion of superoxide radicals into hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen, mediated by Mn²⁺. Together, these examples illustrate the broader principle of host–pathogen metal competition, as depicted in

Figure 4. The schematic shows how macrophage phagolysosomes mobilize copper (Cu²⁺) and zinc (Zn²⁺) ions to intoxicate invading bacteria, while host proteins sequester manganese (Mn²⁺) and zinc to restrict microbial access. In response, pathogens activate high-affinity acquisition systems, including siderophores for iron (Fe³⁺), Mn²⁺ transporters, and Ni²⁺-dependent enzymes. This biochemical tug-of-war defines infection outcomes and provides a framework for therapeutic targeting. Inhibitors that chelate active-site metals or disrupt metalloprotein folding pathways impair bacterial survival under host-imposed metal restriction. Reversible inhibitors, such as α-aminophosphonate derivatives, competitively coordinate catalytic Zn²⁺ ions without permanently altering enzyme structure, restoring antibiotic efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity [

30]. These mechanistic insights underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting metalloproteins with structure-guided precision.

2.2. Importance in Bacterial Survival

Metals fulfill a dual function in bacterial physiology: they act as indispensable cofactors for enzymatic processes and simultaneously serve as stress-inducing agents deployed by host immunity. During infection, macrophage phagolysosomes release toxic concentrations of copper (Cu²⁺) and zinc (Zn²⁺) to impair bacterial viability, while host proteins such as calprotectin sequester manganese (Mn²⁺) and zinc, limiting microbial access to these essential nutrients. In countermeasure, pathogens activate high-affinity metal acquisition systems, including siderophores for iron (Fe³⁺), Mn²⁺ transporters, and Ni²⁺-dependent urease enzymes that facilitate nitrogen metabolism and enhance survival under hostile conditions. This dynamic interplay is illustrated in

Figure 5, which depicts the competitive exchange of metal ions between host and pathogen.

Panel A shows the molecular structure of the enzyme NDM-1 (New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1), highlighting the coordination of a Zn²⁺ ion by key amino acid residues (Cys208, His, His220), along with a hydroxyl group and Bs²⁻, illustrating the metal-binding environment essential for enzymatic activity.

Panel B illustrates the catalytic function of Mn-SOD (Manganese Superoxide Dismutase), where a Mn²⁺ ion facilitates the conversion of superoxide into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), representing a bacterial detoxification strategy against oxidative stress.

Understanding these mechanisms is pivotal for identifying therapeutic targets that disrupt microbial metal homeostasis.

2.3. Potential for Drug Development

Historically, metal-based compounds such as gold salts and arsenicals were used to treat infections and inflammatory diseases. Modern bioinorganic chemistry has revived interest in metal-containing antibiotics that disrupt bacterial metabolism through redox cycling, membrane destabilization, or enzymatic inhibition [

32,

33].

Two primary mechanisms define metal-based antibacterial action:

Extracellular disruption: Charged species and ionic metals destabilize the bacterial envelope and proton motive force.

Intracellular targeting: Metal pharmacophores penetrate cells and undergo organometallic transformations triggered by bacterial reductants.

For example, OP607—a nanoparticle-based iron chelator—has demonstrated biofilm inhibition with low toxicity [

34]. Similarly, α-aminophosphonate inhibitors of NDM-1 selectively bind zinc at the β-lactamase active site, restoring antibiotic efficacy in resistant strains [

30].

Figure 6 illustrates two distinct catalytic strategies for metalloprotein targeting, presented in panels A and B.

Panel A depicts the reversible coordination of Zn²⁺ by an α-aminophosphonate inhibitor at the active site of NDM-1. The inhibitor engages key functional groups (NH₂, CH₃, C=O) and interacts with the zinc ion through nitrogen and oxygen atoms, demonstrating how metal chelation can disrupt enzymatic activity.

Panel B shows the Mn-SOD catalytic cycle, where a Mn²⁺ ion facilitates the conversion of superoxide into oxygen and water. This detoxification mechanism exemplifies how metal-dependent enzymes protect bacteria from oxidative stress.

Together, these panels highlight how metal coordination chemistry can be leveraged to impair bacterial survival and enhance therapeutic precision.

3. Innovative Approaches to Target Metalloproteins: Toward Mechanism-Informed Antibacterial Design.

Metalloproteins, defined by their essential metal-binding domains, represent privileged targets in antibacterial drug discovery. Their structural dependence on transition metals such as zinc, manganese, and copper renders them vulnerable to inhibitors that disrupt metal coordination, enzymatic activity, or trafficking. Recent advances in structural biology, cryo-electron microscopy, and predictive modeling (e.g., AlphaFold) have enabled a shift from empirical screening to mechanism-informed design [

35,

36]. This section explores three major therapeutic modalities—small molecules, biologics, and catalytic metallodrugs—each leveraging distinct strategies to impair metalloprotein function.

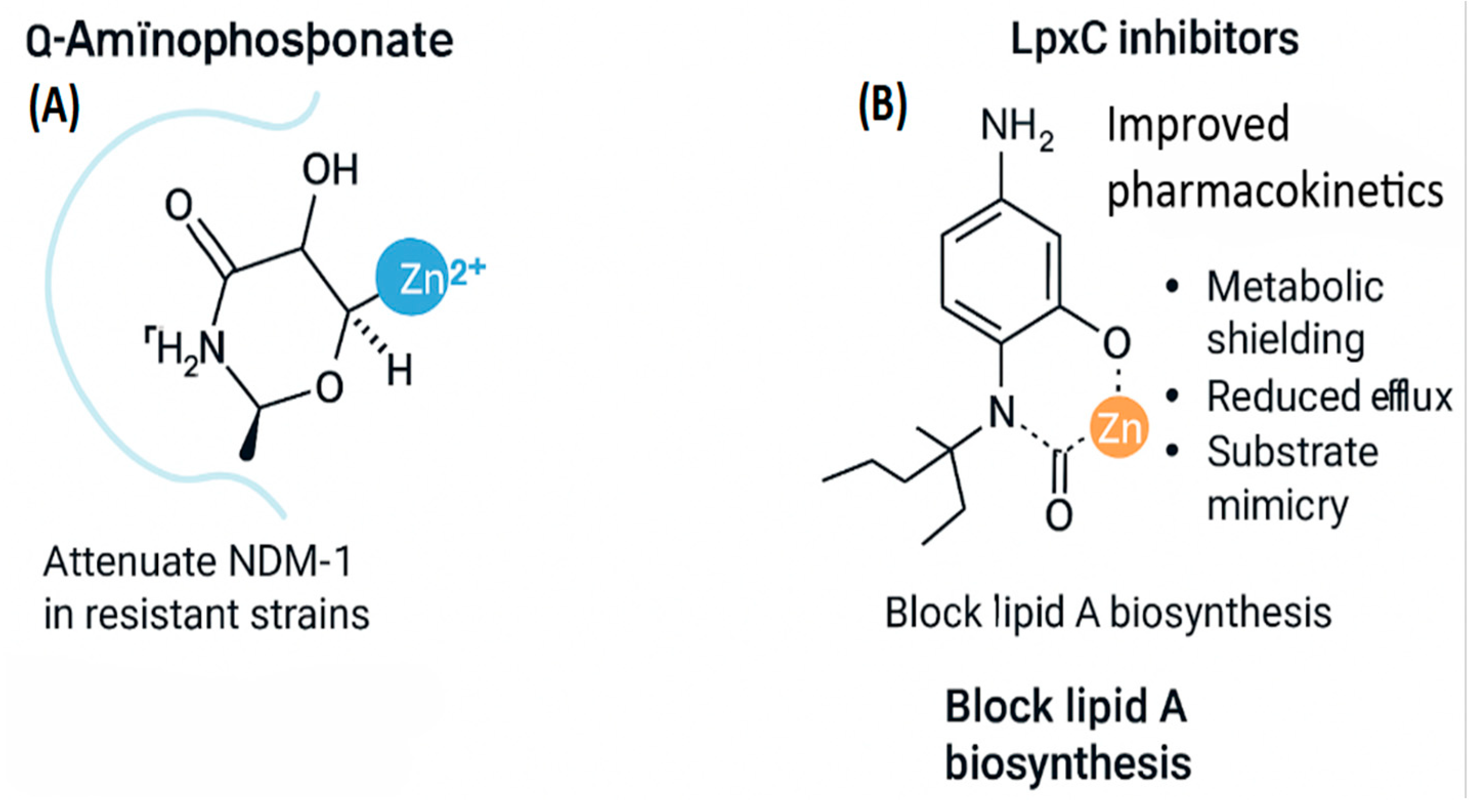

3.1. Small Molecule Inhibitors: Beyond Chelation

Traditional metal chelators, while effective at sequestering essential ions, suffer from poor selectivity and systemic toxicity due to indiscriminate stripping of host cofactors such as Zn²⁺ and Fe³⁺. As discussed in

Section 1.2, this lack of specificity limits their clinical applicability. To overcome these challenges, modern small-molecule inhibitors are designed to engage bacterial metalloproteins through non-catalytic pockets, allosteric sites, or transition-state mimics—preserving isoform selectivity and minimizing host interference.

A prime example is the class of α-aminophosphonate derivatives targeting New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1), a zinc-dependent enzyme responsible for hydrolyzing β-lactam antibiotics. These compounds feature a phosphonic acid moiety that reversibly coordinates Zn²⁺ in the NDM-1 active site, mimicking the tetrahedral geometry of the hydrolytic transition state. The scaffold includes:

A benzene ring substituted with amino (–NH₂) and hydroxyl (–OH) groups to enhance solubility and hydrogen bonding.

A central amine linker that positions the phosphonate for optimal interaction.

A bidentate phosphonic acid group (–PO(OH)₂) that stabilizes the inhibitor–enzyme complex without permanently displacing Zn²⁺.

Figure 7 (A) illustrates how α-aminophosphonates engage the NDM-1 active site with reversible binding, preserving enzymatic architecture while restoring β-lactam efficacy in resistant strains. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies reveal that electron-donating substituents on the aromatic ring enhance binding affinity, while steric bulk near the phosphonate reduces activity due to impaired access to the metal center [

37,

38].

Another notable example is the class of LpxC inhibitors, which block zinc-dependent lipid A biosynthesis—a critical step in Gram-negative outer membrane formation. These inhibitors typically contain a hydroxamate group that chelates the catalytic Zn²⁺, flanked by hydrophobic moieties that engage the enzyme’s substrate-binding tunnel. Their improved pharmacokinetics arise from:

Steric shielding of the hydroxamate group, preventing metabolic degradation.

Polarity tuning, which reduces susceptibility to efflux via RND transporters.

Scaffold rigidification, enhancing binding specificity and minimizing off-target interactions.

Figure 7 (B) shows a hydroxamate-based LpxC inhibitor chelating Zn²⁺, flanked by hydrophobic domains that engage the substrate-binding tunnel. Pharmacokinetic enhancements include metabolic shielding, reduced efflux susceptibility, and scaffold rigidification. These design principles reflect a broader trend toward modular inhibitor architectures, enabling fine-tuned engagement with bacterial metalloprotein motifs while minimizing host toxicity. The integration of cryo-electron microscopy and AlphaFold-based modeling has further enabled the identification of cryptic binding pockets and isoform-specific vulnerabilities, accelerating rational drug design [

35,

36].

3.2. Monoclonal Antibodies and Biologics: Precision Targeting

Biologics offer unmatched specificity for surface-exposed metalloproteins, particularly those involved in host invasion and oxidative stress regulation. Engineered tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) and antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) exemplify this modality [

39,

40]. However, their clinical deployment faces key biophysical and pharmacological challenges:

Limited tissue penetration arises from large molecular size (~150 kDa for IgG) and poor diffusion across epithelial barriers. Glycosylation patterns and charge distribution further restrict movement through dense extracellular matrices.

Binding-site barriers result in peripheral sequestration, where high-affinity binding near vasculature prevents deeper tissue access.

Immunogenicity risks are elevated in chronic infections, where repeated exposure to recombinant proteins may trigger host immune responses.

Recent advances in nanobody engineering and bispecific antibody formats address these limitations. Nanobodies (~15 kDa) exhibit improved penetration and reduced immunogenicity, while bispecifics enable dual targeting of metalloproteins and immune effectors. For instance, biologics directed against manganese superoxide dismutases (MnSODs) or copper transport proteins can synergize with host nutritional immunity, enhancing pathogen clearance while minimizing resistance pressure [

41,

42].

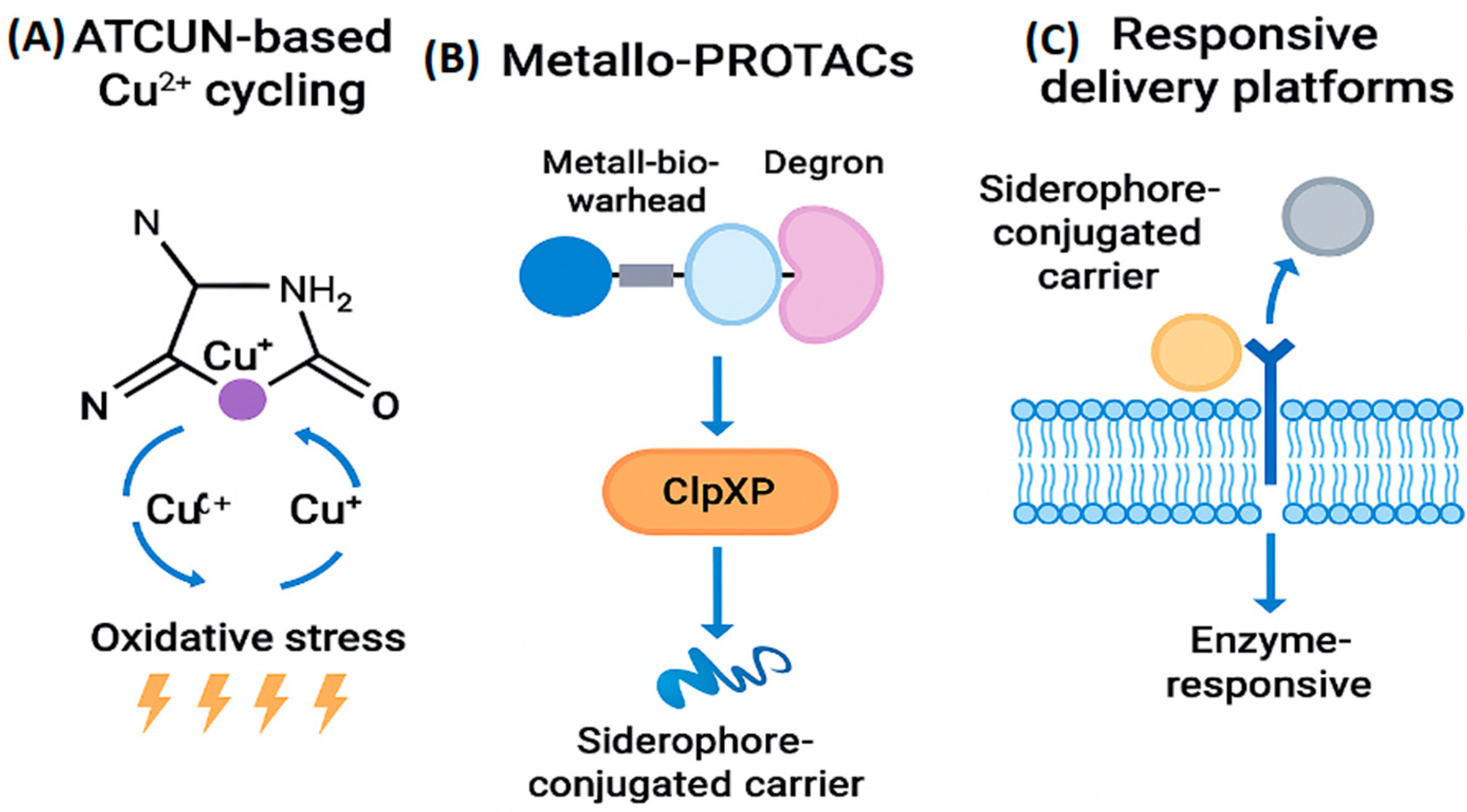

3.3. Catalytic Metallodrugs and Metallo-PROTACs: Mechanistic Innovation

Catalytic metallodrugs represent a frontier in antimicrobial design, exploiting redox cycling, prodrug activation, and organometallic transformations to selectively disrupt bacterial metabolism. One class, based on the ATCUN (amino-terminal copper and nickel binding) motif, generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) within bacterial cells by cycling Cu²⁺/Cu⁺. This induces oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins without harming host tissues, due to differential redox buffering [

43].

Metallo-PROTACs (proteolysis-targeting chimeras) extend this concept by hijacking bacterial degradation pathways to eliminate intracellular metalloproteins. While bacteria lack canonical E3 ligases, synthetic biology approaches may enable the engineering of surrogate degradation systems using ClpXP or Lon proteases. These chimeras typically consist of:

A metal-binding warhead that engages the target metalloprotein.

A linker domain optimized for bacterial permeability and stability.

A degron motif recognized by bacterial proteases, triggering selective degradation.

Challenges include metal lability, off-target reactivity, and limited compatibility with bacterial proteostasis machinery. To overcome these, responsive delivery platforms—such as enzyme-activated nanoparticles and siderophore-conjugated carriers—localize drug action to infection sites. These platforms exploit bacterial uptake pathways and microenvironmental cues (e.g., pH, protease activity) to release payloads near biofilms or intracellular niches, preserving host metal equilibrium and minimizing systemic toxicity [

43].

Figure 8 presents three mechanistically distinct strategies that advance the design of metal-based antimicrobial therapeutics:.

Panel A illustrates ATCUN motif–based catalytic metallodrugs, where Cu²⁺ ions cycle between oxidation states (Cu²⁺ ↔ Cu⁺) to generate oxidative stress, disrupting bacterial integrity through redox-mediated damage.

Panel B depicts Metallo-PROTACs, which combine a metallobioactive warhead with a degron to selectively target bacterial proteins for degradation via the ClpXP protease system. This approach leverages siderophore-conjugated carriers for targeted delivery.

Panel C shows enzyme-responsive delivery platforms, where siderophore-conjugated carriers transport therapeutic payloads across bacterial membranes and release them in response to specific enzymatic cues.

Together, these strategies exemplify how metal coordination, targeted degradation, and responsive delivery can be harnessed to enhance the precision and potency of antimicrobial interventions.

3.4. Future Directions and Expert Perspective

Progress in metalloprotein-targeted antibacterial development depends on integrating structural biology, bioinorganic chemistry, and infection-specific pharmacology to create mechanism-informed therapies. Although recent advances—such as α-aminophosphonate inhibitors, LpxC inhibitors, nanobody formats, and catalytic metallodrugs—demonstrate translational promise, several fundamental challenges must be addressed to advance the field.

A major limitation is the lack of standardised, physiologically relevant infection models. Many current systems do not accurately represent host-imposed metal restriction or intoxication, spatial metal gradients in tissues, redox conditions generated during inflammation, or the biofilm-associated microenvironments that modulate metalloprotein expression and metal uptake pathways. Because metalloprotein function is strongly conditioned by metal availability and immune pressure, these discrepancies reduce the predictive value of preclinical studies. Establishing harmonised, metal-aware models—incorporating nutritional immunity factors such as calprotectin, realistic Zn/Mn gradients, copper-mediated toxicity, and infection-site pharmacokinetics—will improve reproducibility and help identify therapeutics with genuine translational potential.

Equally important is the shift toward multi-targeting strategies that address the redundancy and adaptability of bacterial metal homeostasis networks. Bacteria frequently evade single-inhibitor pressure by activating alternative siderophore systems, expressing paralogous metalloenzymes, rewiring oxidative stress responses, or altering membrane permeability and metal flux. Future antibacterial design should therefore integrate complementary mechanisms of action, including dual-pathway inhibition (e.g., siderophore blockade plus Mn-SOD inhibition), rational drug combinations based on network topology, bifunctional inhibitors that couple metal-binding pharmacophores with allosteric modulators, and catalytic metallodrugs or metallo-PROTACs capable of disabling multiple essential nodes.

Together, model standardisation and redundancy-aware multi-target strategies form a coherent roadmap for future innovation. Evaluating inhibitors within realistic microenvironmental constraints will sharpen mechanistic insight and translational accuracy, while multi-target agents will reduce evolutionary escape and increase therapeutic durability. As next-generation metalloprotein inhibitors continue to mature, integrating these principles will be crucial for achieving selective, resistance-resilient, and clinically actionable antibacterial therapies.

4. Critical Appraisal and Innovation Pathways

Targeting bacterial metalloproteins represents a paradigm shift in antimicrobial design [

44]. By focusing on pathogen-specific processes—such as metal acquisition, redox regulation, and enzymatic detoxification—this approach enables

selective inhibition with minimal impact on host physiology and commensal microbiota [

45].

4.1. Isoform Selectivity and Structural Precision

Non-chelating inhibitors, allosteric binders, and biologics offer enhanced specificity for bacterial metalloproteins. Advances in cryo-electron microscopy and AlphaFold-based modeling have enabled the identification of cryptic binding pockets and pathogen-restricted motifs [

46]. These tools support rational drug design by revealing isoform-specific vulnerabilities that are not apparent from sequence data alone. For example, AlphaFold3 has been used to model ligand interactions in cryo-EM maps, improving inhibitor docking accuracy [

47] .

4.2. Delivery Platform Optimization

Responsive nanoparticles and siderophore–antibiotic conjugates exploit bacterial transport mechanisms to achieve intracellular delivery. These platforms improve therapeutic index and reduce systemic exposure by localizing drug action to infection. The “Trojan horse” strategy—where antibiotics are linked to siderophores—has shown promise against Gram-negative pathogens with impermeable outer membranes [

48].

Figure 4 illustrates these delivery modalities, including enzyme-triggered release and receptor-mediated uptake.

4.3. Multi-Target Resistance Mitigation

Functional redundancy and transporter mutations necessitate multi-pronged strategies. Comparative genomics and resistance modeling can guide the selection of conserved virulence-associated targets to reduce resistance emergence [

49]. Tools like gSpreadComp integrate genomic and plasmid data to rank therapeutic candidates based on resistance risk and evolutionary conservation [

50].

4.4. Interdisciplinary Integration for Clinical Translation

Bridging structural biology, bioinformatics, medicinal chemistry, and infection-specific pharmacology is essential. Systems biology approaches—incorporating transcriptomic and proteomic data—can refine target prioritization and predict host–pathogen interactions under therapeutic pressure [

51]. These models help simulate drug behavior in complex infection microenvironments, such as biofilms and intracellular niches [

52].

To accelerate progress, we recommend:

-

Mapping Metalloprotein Networks:

Conduct metagenomic profiling across diverse pathogens to delineate conserved and strain-specific vulnerabilities[

53]. This includes mining environmental and clinical datasets to identify underexplored metalloprotein families.

-

Designing Hybrid Therapeutics:

Develop dual-function agents that inhibit microbial growth while attenuating virulence. Examples include molecules that combine enzymatic inhibition with immunomodulatory or quorum-sensing disruption effects [

54].

-

Refining Host–Pathogen Metal Dynamics:

Investigate metal competition at infection sites to define therapeutic windows and minimize collateral effects on host metalloproteins. Leveraging host metal sequestration mechanisms may offer adjunctive therapeutic benefits [

55].

-

Standardizing In Vivo Models:

Create infection models that accurately recapitulate microenvironments such as biofilms, abscesses, and intracellular niches. These should incorporate immune modulation, metal availability, and pharmacokinetic parameters to predict clinical outcomes [

56]

Among the strategies reviewed, receptor-mediated delivery systems and non-chelating pocket binders demonstrate the highest translational potential due to their specificity, reduced host toxicity, and compatibility with existing antibiotic regimens. Biologics—including monoclonal antibodies and TIMPs—offer exceptional selectivity but face challenges in cost, immunogenicity, and tissue penetration. Catalytic metallodrugs and metallo-PROTACs, while mechanistically novel, require further validation to address concerns related to metal lability and host reactivity. In contrast, Zn-chelating agents, despite historical utility, rank lowest due to poor isoform selectivity and systemic toxicity risks [

1,

26].

This framework supports the development of mechanism-informed antibacterial agents that align with ecological stewardship and personalized medicine.

5. Case Studies of Metalloprotein-Targeted Antibacterial Strategies

Disrupting bacterial metal homeostasis has emerged as a promising therapeutic avenue, particularly by targeting iron and zinc metabolism. Iron chelators such as 2,2′-bipyridyl sequester ferric ions, depriving pathogens of cofactors essential for respiration, DNA synthesis, and enzymatic catalysis [

57,

58]. In

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, iron deprivation reduces biofilm biomass and suppresses quorum-sensing regulators (lasR, rhlI), while in

Escherichia coli siderophore-mediated uptake is impaired, leading to bacteriostasis[

30,

59]. Gallium-based compounds extend this principle by mimicking iron and competitively disrupting iron-dependent enzymes; gallium nitrate has progressed into clinical trials for cystic fibrosis infections, underscoring translational relevance.

Zinc sequestration represents another potent strategy, particularly against metallo-β-lactamases such as NDM-1. These enzymes rely on zinc ions for hydrolytic activity, and targeted chelation collapses their catalytic function. In murine models infected with NDM-1-producing

Klebsiella pneumoniae, zinc deprivation reduced bacterial burden significantly [

60,

61]. Reversible inhibitors such as OP607 coordinate catalytic Zn²⁺ ions without permanently altering enzyme structure, restoring carbapenem efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity [

62].

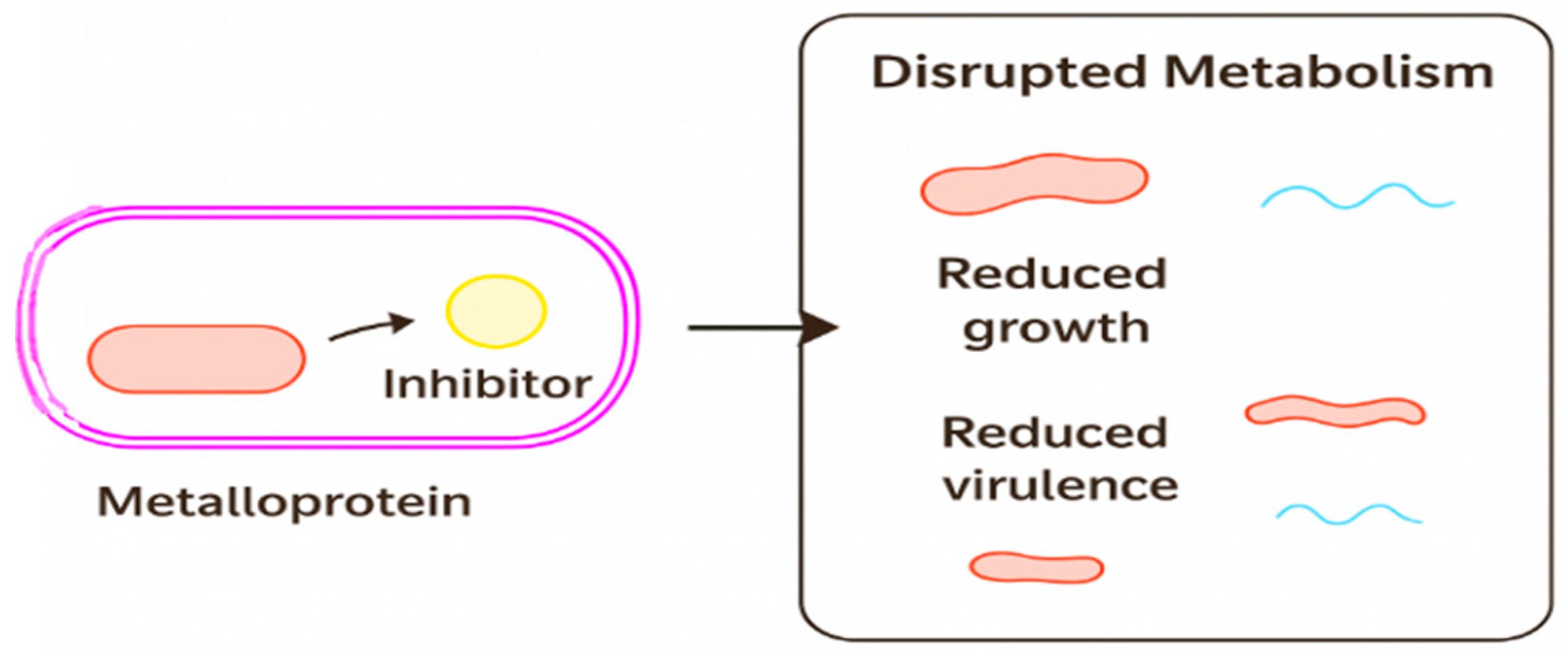

Figure 9 schematically illustrates this principle: metalloprotein inhibition disrupts enzymatic activity, leading to metabolic collapse and reduced virulence.

Copper-based agents exploit redox cycling to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) within bacterial cells. In E. coli, copper complexes overwhelm antioxidant defenses, reducing catalase activity and triggering oxidative stress–mediated cell death. While effective, selectivity remains a challenge, as mammalian cells also depend on redox balance. Controlled delivery platforms are therefore essential to localize copper activity to infection sites.

Emerging modalities further expand the therapeutic landscape. Metallo-PROTACs irreversibly degrade metalloproteins rather than transiently inhibiting them; platinum-based PROTACs targeting thioredoxin reductase have achieved complete enzyme clearance in resistant

Staphylococcus aureus. Responsive nanoparticles represent another innovation, releasing inhibitors only in infection sites with elevated protease activity, thereby reducing systemic toxicity [

24,

43].

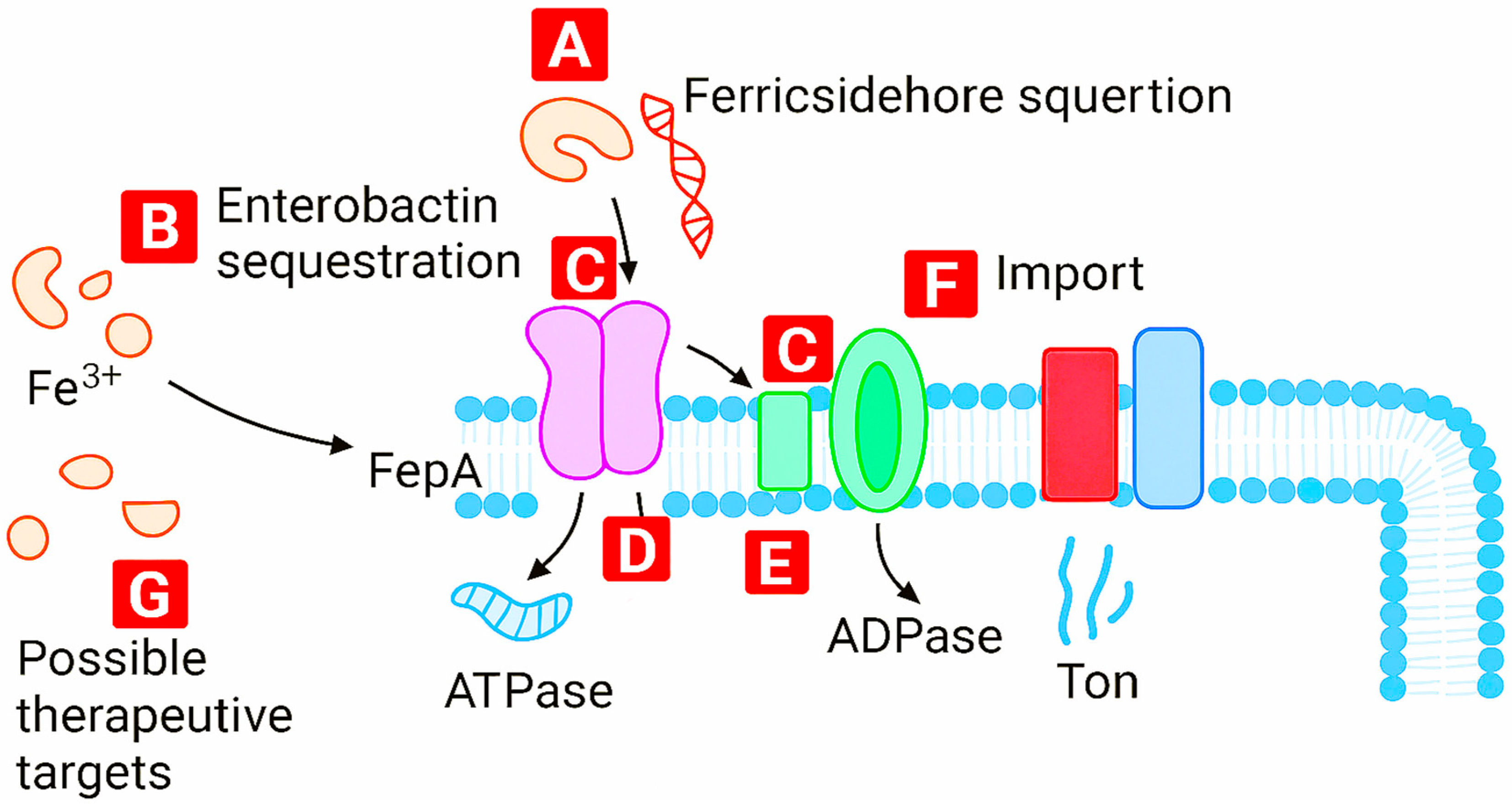

Figure 5 maps the iron uptake network in Gram-negative bacteria, identifying regulatory nodes (A–G) that govern siderophore biosynthesis, transport, and feedback control. This systems-level view enables rational targeting of bottlenecks in metal trafficking.

Table 3 provides a comparative overview of strategic modalities, highlighting advantages and limitations. Zn-chelating agents offer high potency but suffer from poor isoform selectivity and systemic toxicity. Non-chelating binders achieve improved specificity by targeting allosteric pockets, though their design requires detailed structural data. Biologics such as TIMPs and monoclonal antibodies provide exceptional selectivity but face challenges in tissue penetration and cost [

16,

43]. Metallo-PROTACs and responsive nanoparticles enable spatial control and irreversible inhibition, though formulation complexity remains a barrier to clinical translation.

Recent efforts have also focused on receptor-mediated delivery systems that exploit pathogen-specific uptake pathways. Siderophore–antibiotic conjugates, for example, utilize bacterial iron transporters to achieve targeted intracellular delivery, minimizing collateral damage to host cells [

63,

64].

Figure 10 integrates these concepts by mapping regulatory feedback loops in iron acquisition, offering a framework for rational intervention.

Collectively, these case studies validate the mechanistic rationale behind metalloprotein targeting while emphasizing the need for pathogen-specific selectivity, scalable delivery platforms, and regulatory frameworks attuned to next-generation antimicrobials. By combining structural biology, bioinorganic chemistry, and infection pharmacology, metal-focused strategies can evolve from conceptual promise to clinically actionable therapies [

11,

12,

62].

While multiple studies support the efficacy of gallium-based antimicrobials in disrupting iron metabolism, their translational potential remains limited by host toxicity and narrow-spectrum activity. In contrast, manganese chelation strategies appear more promising due to their broader impact on oxidative stress pathways. However, the risk of off-target effects on host metalloproteins must be critically evaluated. This suggests that dual-targeting approaches—combining metal chelation with efflux pump inhibition—may offer a more robust therapeutic window [

43].

These case studies not only validate the mechanistic rationale behind metalloprotein targeting but also underscore the need for integrating such strategies into drug development pipelines that prioritize pathogen-specific selectivity, scalable delivery platforms, and regulatory frameworks attuned to next-generation antimicrobial agents.

6. Strategic Challenges and Translational Pathways in Metalloprotein Targeting

Although remarkable progress has been made in elucidating the mechanisms and therapeutic potential of bacterial metalloproteins, the field of metalloprotein-targeted antibacterial research remains in its infancy. Only a limited number of bacterial metalloproteins have been characterized in sufficient detail, and the biochemistry and structure–activity relationships of their inhibitors are still poorly understood. As drug design ventures into less established territories of medicinal chemistry, caution and multidimensional innovation are essential.

One key challenge is the limited success of target-based computational methods, such as molecular docking and computer-aided drug design (CADD), in developing effective inhibitors for bacterial metalloproteins like metallothioneins. Although target-based screening against many metalloprotein families has yielded promising enzyme inhibitors, these often fail in cellular systems where the targeted proteins can be circumvented through redundant or compensatory pathways [

65]. Addressing such complexity will require multi-parameter strategies that combine broad-spectrum inhibition with selective targeting to avoid bypass mechanisms. For example, TEM-1 β-lactamase—despite a 50% invariant sequence—can develop resistance through mutations affecting only ~10% of its active site residues, dramatically altering acylation rates and antibiotic hydrolysis [

66]. Hence, designing robust inhibitors necessitates comprehensive coverage of potential mutational landscapes through integrated structural, genomic, and evolutionary analyses.

Furthermore, achieving specificity and selectivity poses one of the greatest hurdles in metalloprotein-targeted therapy. Target proteins frequently exist as multiple isoforms with over 90% sequence similarity to non-target homologs, leading to off-target effects. Advanced crystallographic and bioinformatic tools are now being leveraged to predict metal-binding residues, identify off-target metalloproteins, and guide ligand optimization toward highly selective metallodrugs [

67]. Integrative bioinformatics pipelines that match three-dimensional protein models with selective ligands enable rational design of compounds with controlled metal coordination geometries and predictable binding affinities. This approach, when coupled with experimental validation of metal–ligand complexes, represents a promising pathway toward achieving selectivity without compromising potency [

68].

Beyond selectivity, regulatory and developmental hurdles remain formidable. Despite the urgent global demand for new antimicrobials, the clinical pipeline remains alarmingly sparse. Only a handful of novel antibiotics have reached late-stage trials, and most are derivatives of existing scaffolds [

26]. Encouragingly, pharmacological screenings of hundreds of metal-containing compounds have revealed dozens with potent activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains, demonstrating the untapped potential of metal-based complexes [

26].

Gallium, a Group IIIA metal, is structurally and chemically similar to ferric iron (Fe³⁺), allowing it to mimic iron and interfere with bacterial iron metabolism. Unlike iron, gallium is redox-inactive and cannot participate in Fenton reactions or catalyze essential enzymatic processes. This unique property enables gallium compounds to disrupt iron-dependent pathways in bacteria, leading to impaired DNA synthesis, respiration, and oxidative stress management. Multiple in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial activity of gallium-based compounds, particularly against

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other iron-scavenging pathogens. Gallium nitrate and gallium-protoporphyrin IX have shown efficacy in inhibiting biofilm formation and growth by targeting iron-regulated virulence systems. These findings underscore gallium’s potential as an iron mimetic therapeutic agent. However, their translational application remains constrained by host toxicity at therapeutic concentrations and a relatively narrow antimicrobial spectrum. Additionally, delivery and stability challenges in physiological environments further limit clinical advancement [

12].

To overcome these barriers, future research must adopt a holistic, genome-to-phenotype approach. Although progress in metalloprotein biology has been significant, much of our knowledge is derived from a small subset of model organisms such as

E. coli or

S. aureus [

42]. Predicting metalloproteins at a genomic scale—across diverse pathogenic taxa—is essential for mapping their evolutionary distribution, functional roles, and virulence associations. Comparative genomics and proteomics now enable the mining of entire microbial lineages for conserved and divergent metalloprotein families, offering a foundation for precision-targeted drug discovery. Integrating computational predictions with biochemical assays, structural biology, and cellular validation can transform these genomic insights into actionable therapeutic leads.

Equally critical are collaborative research initiatives and global capacity building. Addressing the escalating crisis of antibiotic resistance demands sustained international cooperation, encompassing not only data sharing and technology transfer but also long-term training and infrastructure development. Collaborative networks that unite computational biologists, chemists, and microbiologists are essential for translating fundamental discoveries into viable therapeutics. Educational initiatives must therefore expand to include interdisciplinary training in bioinorganic chemistry, computational biology, and translational microbiology, ensuring the next generation of scientists can tackle these complex challenges effectively.

At the global health level, antibiotic resistance represents one of the most pressing biomedical threats of the 21st century. Effective mitigation requires cross-border collaboration, particularly in regions where resistant infections are most prevalent—Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and South America. Establishing new laboratories, promoting access to diagnostic technologies, and fostering research partnerships in these regions are crucial for a coordinated response. Moreover, the rise of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria poses unique challenges due to their impermeable outer membranes, diverse virulence factors, and rapid horizontal gene transfer. Innovative approaches such as microbiome engineering, synthetic microbial competition, and bio-inspired drug delivery systems offer new hope for counteracting these resilient pathogens.

In parallel, ethical and regulatory frameworks must evolve to ensure that antimicrobial research complies with biosafety and responsible research guidelines. According to European Commission (EC) directives on BSL-2 organisms, all research involving pathogenic bacteria must adhere to established Risk Assessment Protocols and Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) standards [

15].

Collaborative projects that integrate ethics training, open decision-making, and transparent data management represent a model for sustainable, ethically aligned scientific progress.

7. Concluding Perspectives

Antibiotic resistance continues to outpace drug innovation, threatening global health and demanding a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategy. Selective targeting of bacterial metalloprotein pathways, particularly those involved in iron acquisition, oxidative stress defense, and virulence regulation, offers a promising route toward next-generation antibacterial agents with high precision and low host toxicity.

By critically examining current approaches, this review highlights the key limitations of traditional antibiotics—namely poor selectivity, rapid resistance emergence, and microbiome disruption—and contrasts them with the mechanistic precision of metalloprotein-targeting agents. These include siderophore–antibiotic conjugates, catalytic metallodrugs, and antibody-based biologics, each offering new therapeutic horizons. Their success, however, depends on overcoming obstacles related to delivery, specificity, and adaptive resistance.

Moving forward, a mechanism-informed framework for antibacterial development should integrate:

Genomic profiling to identify pathogen-specific vulnerabilities.

Structure-guided drug design to create non-chelating inhibitors and selective biologics.

Responsive delivery systems tailored to infection microenvironments.

Multi-target strategies that disrupt metal trafficking and virulence simultaneously.

As the post-antibiotic era approaches, innovation in metalloprotein-targeting therapeutics offers a critical lifeline. These strategies not only impair bacterial survival but also redefine the antibacterial paradigm by prioritizing precision, safety, and sustainability. Continued investment in bioinorganic chemistry, structural biology, systems pharmacology, and translational research will be essential to fully realize the therapeutic potential of metalloproteins and to restore the delicate balance between human health and microbial evolution.

Funding

This research received a specific grant from the National Science Foundation (NCN).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses sincere gratitude to Prof. Ziarno for his invaluable guidance and constructive feedback, which greatly enhanced the analytical rigor and clarity of this review. Appreciation is also extended to the staff of the Metalloprotein Biology Laboratory at the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, for their support and for generously hosting the author during the internship period.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The author declares no conflict of interest related to the content, data interpretation, or publication of this manuscript.

References

- F., J.; Staats, C. C.; Pontes, M. H. Editorial: Metal Homeostasis in Microbial Physiology and Virulence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1183137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, S. L. The Role of Metal Ions in the Virulence and Viability of Bacterial Pathogens. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47(1), 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Koh, J.; Cha, S.; Roe, J. Activation of Zinc Uptake Regulator by Zinc Binding to Three Regulatory Sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52(8), 4185–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrangsu, P.; Rensing, C.; Helmann, J. D. Metal Homeostasis and Resistance in Bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15(6), 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnwal, A.; Jassim, A. Y.; Mohammed, A. A.; Mohammad Said, A. R.; Selvaraj, M.; Malik, T. Addressing the global challenge of bacterial drug resistance: Insights, strategies, and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1517772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, V.; Zineddu, S.; Messori, L. Metal Compounds as Antimicrobial Agents: Smart Approaches for Discovering New Effective Treatments. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, K. J.; Chopra, I.; Fishwick, C. W. G. Structure-Based Discovery of Antibacterial Drugs. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8(4), 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl-Fie, T. E.; Skaar, E. P. Nutritional Immunity beyond Iron: A Role for Manganese and Zinc. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14(2), 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa, K. T.; Sala, F. A.; Miyachiro, M. M.; Job, V.; Trindade, D. M.; Dessen, A. Architecture and Genomic Arrangement of the MurE–MurF Bacterial Cell Wall Biosynthesis Complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120(21), e2219540120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossolini, G. M. Extensively Drug-Resistant Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: An Emerging Challenge for Clinicians and Healthcare Systems. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 277(5), 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. M.; Reid-Yu, S. A.; Wang, W.; King, D. T.; De Pascale, G.; Strynadka, N. C.; Walsh, T. R.; Coombes, B. K.; Wright, G. D. AMA Overcomes Antibiotic Resistance by NDM and VIM Metallo-β-Lactamases. Nature 2014, 510(7506), 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palica, K.; Deufel, F.; Skagseth, S.; Di Santo Metzler, G. P.; Thoma, J.; Andersson Rasmussen, A.; Valkonen, A.; Sunnerhagen, P.; Leiros, H.-K.; Andersson, H.; Erdelyi, M. α-Aminophosphonate Inhibitors of Metallo-β-Lactamases NDM-1 and VIM-2. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14(11), 2277–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, A. K.; El-Khateeb, M.; Taha, Z. A.; et al. Anti-Bacterial and Anti-Fungal Properties of a Set of Transition Metal Complexes Bearing a Pyridine Moiety and [B(C₆F₅)₄]₂ as a Counter Anion. Molecules 2025, 30(15), 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, V.; Frey, C.; Normant, V.; et al. The Role of FoxA, FiuA, and FpvB in Iron Acquisition via Hydroxamate-Type Siderophores in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Goetsch, L.; Dumontet, C.; Corvaïa, N. Strategies and Challenges for the Next Generation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16(5), 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, M. I.; Skaar, E. P. Nutritional Immunity: Transition Metals at the Pathogen–Host Interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10(8), 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Su, Z.; Chen, P.; Tian, X.; Wu, L.; Tang, D.-J.; Li, P.; Deng, H.; Ding, P.; Fu, Q.; Tang, J.-L.; Ming, Z. Structural Basis for Zinc-Induced Activation of a Zinc Uptake Transcriptional Regulator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49(11), 6511–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šink, R.; Kotnik, M.; Zega, A.; Barreteau, H.; Gobec, S.; Blanot, D.; et al. Crystallographic Study of Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis Enzyme MurD: Domain Movement Revisited. PLoS ONE 2016, 11(3), e0152075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C. J. L.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance. Lancet 2022, 399(10325), 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Bian, X.; Li, Y.; et al. In Vitro Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of FL058 (a Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitor) Combined with Meropenem against Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1282480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 and CRISPR-Assisted Cytidine Deaminase Enable Precise and Efficient Genome Editing in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01834-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Siderophore Regulation by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa BfmRS Two-Component System in Response to Osmotic Stress. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaço, H. G.; Santo, P. E.; Matias, P. M.; Bandeiras, T. M.; Vicente, J. B. Roles of Escherichia coli ZinT in Cobalt, Mercury and Cadmium Resistance and Structural Insights into the Metal Binding Mechanism. Metallomics 2016, 8(3), 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, D. A.; Wang, J.; Giedroc, D. P. Bacterial Strategies to Maintain Zinc Metallostasis at the Host–Pathogen Interface. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291(40), 20858–20868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoko, K. Y.; Ong, C. L.; Walker, M. J.; McEwan, A. G. The Role of Copper and Zinc Toxicity in Innate Immune Defense against Bacterial Pathogens. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290(31), 18954–18961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K. At the Nexus of Antibiotics and Metals: The Impact of Cu and Zn on Antibiotic Activity and Resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25(10), 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, L. D.; Skaar, E. P. Transition Metals and Virulence in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016, 50, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Reid-Yu, S.; Wang, W.; et al. Aspergillomarasmine A Overcomes Metallo-β-Lactamase Antibiotic Resistance. Nature 2014, 510, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, G.; Di Guilmi, A. M.; Hall, B. G. Structure-Based Phylogeny of the Metallo-β-Lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49(7), 2778–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palica, K.; Deufel, F.; Skagseth, S.; et al. α-Aminophosphonate Inhibitors of Metallo-β-Lactamases NDM-1 and VIM-2. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14(11), 2277–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl-Fie, T. E.; Skaar, E. P. Nutritional Immunity Beyond Iron: A Role for Manganese and Zinc. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14(2), 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemire, J.; Harrison, J.; Turner, R. Antimicrobial Activity of Metals: Mechanisms, Molecular Targets and Applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Ye, Z.; Hsieh, C. Y.; et al. MetalProGNet: A Structure-Based Deep Graph Model for Metalloprotein–Ligand Interaction Predictions. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 2054–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Bisen, M.; Harjai, K.; et al. Advances in Nanotechnology for Biofilm Inhibition. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 21391–21409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y. Single-Particle Cryo-EM at Crystallographic Resolution. Cell 2015, 161, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hu, Y.; Xu, F.; et al. Chelation Strategies in Antimicrobial Design. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hao, Q. Crystal Structure of NDM-1 Reveals Zinc-Binding Site. PLoS ONE 2011, 6(9), e24621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Ragusa, M. A.; Lo Buglio, G.; Scilabra, S. D.; Nicosia, A. The Repertoire of Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteases: Evolution, Regulation of Extracellular Matrix Proteolysis, Engineering and Therapeutic Challenges. Life 2022, 12(8), 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. K.; Stylianopoulos, T. Delivering Nanomedicine to Solid Tumors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békés, M.; Langley, D. R.; Crews, C. M. PROTAC Targeted Protein Degraders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Siderophore-Conjugated Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Li, Z.; Liao, B.; et al. Microcalorimetric Study of the Effect of Manganese on the Growth and Metabolism in a Heterogeneously Expressing Manganese-Dependent Superoxide Dismutase (Mn-SOD) Strain. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 130, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A. J.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.; et al. Persistent Metagenomic Signatures of Early-Life Hospitalization and Antibiotic Treatment in the Infant Gut Microbiota and Resistome. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4(12), 2285–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K. W.; Skaar, E. P. Metal Limitation and Toxicity at the Interface between Host and Pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38(6), 1235–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokidis, M. G.; Koumadorakis, D. E.; Lazaros, K.; Ivantsik, O.; Exarchos, T. P.; Vrahatis, A. G.; Kotsiantis, S.; Vlamos, P. AlphaFold3: An Overview of Applications and Performance Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26(8), 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haloi, N.; Howard, R. J.; Lindahl, E. Cryo-EM Ligand Building Using AlphaFold3-like Model and Molecular Dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21(8), e1013367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, V.; Gao, M.-L.; Sterk, F. A. C.; Innocenti, P.; Slingerland, C. J.; Martin, N. I. ACS Infect. Dis. 2025, 11(8), 2301–2309. [CrossRef]

- Sherry, N. L.; Lee, J. Y. H.; Giulieri, S. G.; Connor, C. H.; Horan, K.; Lacey, J. A.; Lane, C. R.; Carter, G. P.; Seemann, T.; Egli, A.; Stinear, T. P.; Howden, B. P. Genomics for Antimicrobial Resistance—Progress and Future Directions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e01082-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasmanas, J. C.; Magnúsdóttir, S.; Zhang, J.; Smalla, K.; Schloter, M.; Stadler, P. F.; Ponce, A. C.; Rocha, U. Integrating Comparative Genomics and Risk Classification by Assessing Virulence, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Plasmid Spread in Microbial Communities with gSpreadComp. GigaScience 2025, 14, giaf072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.; Hale, C.; Clare, S.; Palmer, S.; Bartholdson Scott, J.; Baker, S.; Dougan, G. Using a Systems Biology Approach To Study Host–Pathogen Interactions. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7(2), BAI-0021-2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. E. In Computational Systems Pharmacology and Toxicology; Richardson, R. J., Johnson, D. E., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2017; pp 1–18.

- Francine, P. Systems Biology: New Insight into Antibiotic Resistance. Microorganisms 2022, 10(12), 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J. Metagenomic Identification of Pathogens and Antimicrobial-Resistant Genes in Bacterial Positive Blood Cultures by Nanopore Sequencing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1283094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, N. S.; Riber, L. Metagenomics as a Transformative Tool for Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance: Highlighting the Impact of Mobile Genetic Elements with a Focus on the Complex Role of Phages. Antibiotics 2025, 14(3), 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräff, Á. T.; Barry, S. M. Siderophores as Tools and Treatments. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskey, R. C.; Xiao, J.; Hyoju, S.; et al. Enterobactin Inhibits Microbiota-Dependent Activation of AhR to Promote Bacterial Sepsis in Mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, M.; Ayodeji, O. E.; Yetunde, B. B.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity of Mixed Antibiotic–Vitamin Metal Complexes Involving Metronidazole and Vitamin B1 (Thiamine). Asian J. Chem. Sci. 2024, 14(6), 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, L.; Hagiya, H.; Gotoh, K.; et al. New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase Inhibitors: A Systematic Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13(14), 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Sato, Y.; et al. Identification of Actinomycin D as a Specific Inhibitor of the Alternative Pathway of Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Bian, X.; Li, Y.; et al. In Vitro Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of FL058 (a Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitor) Combined with Meropenem against Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1282480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalk, I. J. Bacterial siderophores: Diversity, uptake pathways and applications. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2024, 23(1), 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsube, T.; Echols, R.; Arjona Ferreira, J. C.; Krenz, H. K.; Berg, J. K.; Galloway, C. Cefiderocol, a Siderophore Cephalosporin for Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections: Pharmacokinetics and Safety in Subjects with Renal Impairment. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 57(5), 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, J. R.; Skaar, E. P. Acinetobacter baumannii Can Use Multiple Siderophores for Iron Acquisition, but Only Acinetobactin Is Required for Virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16(10), e1008995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serebnitskiy, Z.; Orban, K.; Finkel, S. E. A Role for Dps Ferritin Activity in Long-Term Survival of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e01837-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, C. M.; Prieto, J. M.; Martí, M. Precision Docking for Metalloproteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64(5), 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; et al. A Manganese-Superoxide Dismutase from Thermus thermophilus HB27 Suppresses Inflammatory Responses and Alleviates Experimentally Induced Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25(10), 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M. R.; Videira, M. A.; Lima, J. C.; Saraiva, L. Mechanistic Insights into Staphylococcus aureus IsdG-Ferrochelatase Interactions: A Key to Understanding Haem Homeostasis in Pathogens. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 269, 112878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Mechanistic pathways of metalloprotein-mediated bacterial pathogenesis. (A) Copper resistance operons (Copr) and zinc transport systems facilitate detoxification and metal homeostasis under host-imposed stress. (B) Oxidative stress defense mediated by manganese- and iron-dependent superoxide dismutases (SOD = superoxide dismutase), which neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS). (C) Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition supports bacterial metabolism and virulence. (D) Zinc-dependent polymerases are essential for DNA replication and repair. These mechanisms illustrate how metalloproteins enable bacterial survival and virulence under host stress conditions.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic pathways of metalloprotein-mediated bacterial pathogenesis. (A) Copper resistance operons (Copr) and zinc transport systems facilitate detoxification and metal homeostasis under host-imposed stress. (B) Oxidative stress defense mediated by manganese- and iron-dependent superoxide dismutases (SOD = superoxide dismutase), which neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS). (C) Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition supports bacterial metabolism and virulence. (D) Zinc-dependent polymerases are essential for DNA replication and repair. These mechanisms illustrate how metalloproteins enable bacterial survival and virulence under host stress conditions.

Figure 2.

Structural diversity of antimicrobial agents targeting metalloproteins. (A) OP607 zinc-binding scaffold that inhibits metallo-β-lactamases. (B) Antibody-based inhibitors designed for selective epitope binding. (C) Nanoparticle systems (PEG = polyethylene glycol) engineered for drug delivery and stability. (D) Metal chelators such as tris(benzyltriazolyl)methylamine sequester essential ions. This figure highlights distinct therapeutic modalities and their mechanisms of action.

Figure 2.

Structural diversity of antimicrobial agents targeting metalloproteins. (A) OP607 zinc-binding scaffold that inhibits metallo-β-lactamases. (B) Antibody-based inhibitors designed for selective epitope binding. (C) Nanoparticle systems (PEG = polyethylene glycol) engineered for drug delivery and stability. (D) Metal chelators such as tris(benzyltriazolyl)methylamine sequester essential ions. This figure highlights distinct therapeutic modalities and their mechanisms of action.

Figure 3.

Cellular roles of metal ions in bacterial metabolism. The diagram shows how essential metals contribute to bacterial processes across compartments. Iron (Fe) supports DNA synthesis, the TCA cycle, electron transport, and photosynthesis. Zinc (Zn) is involved in transcription, protein synthesis, and glycolysis. Manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co) enable superoxide dismutase activity, urea cycle function, and ammonia processing. Copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) in the extracellular environment reflect host-imposed stress responses. Glucose uptake links nutrient acquisition to intracellular pathways.

Figure 3.

Cellular roles of metal ions in bacterial metabolism. The diagram shows how essential metals contribute to bacterial processes across compartments. Iron (Fe) supports DNA synthesis, the TCA cycle, electron transport, and photosynthesis. Zinc (Zn) is involved in transcription, protein synthesis, and glycolysis. Manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co) enable superoxide dismutase activity, urea cycle function, and ammonia processing. Copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) in the extracellular environment reflect host-imposed stress responses. Glucose uptake links nutrient acquisition to intracellular pathways.

Figure 4.

Host–pathogen competition for essential metal ions. This illustration depicts the dynamic exchange of metal ions between host immune cells and bacterial pathogens. Macrophage phagolysosomes mobilize copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) ions to intoxicate invading microbes, while host proteins sequester manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and other metals to restrict microbial access. In response, pathogens deploy siderophores and specialized transporters to acquire iron (Fe³⁺), manganese (Mn), and nickel (Ni²⁺), enabling survival under metal-limited conditions. The diagram highlights opposing strategies of host sequestration and pathogen acquisition, emphasizing the role of metal homeostasis in infection outcomes.

Figure 4.

Host–pathogen competition for essential metal ions. This illustration depicts the dynamic exchange of metal ions between host immune cells and bacterial pathogens. Macrophage phagolysosomes mobilize copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) ions to intoxicate invading microbes, while host proteins sequester manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and other metals to restrict microbial access. In response, pathogens deploy siderophores and specialized transporters to acquire iron (Fe³⁺), manganese (Mn), and nickel (Ni²⁺), enabling survival under metal-limited conditions. The diagram highlights opposing strategies of host sequestration and pathogen acquisition, emphasizing the role of metal homeostasis in infection outcomes.

Figure 5.

Mechanisms of action of bacterial metalloproteins. (A) Chemical structure of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1 ) active site showing Zn²⁺ coordination with Cys208, His220, and a bridging sulfide. (B) Catalytic cycle of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), converting superoxide radicals (O₂⁻) into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and water.

Figure 5.

Mechanisms of action of bacterial metalloproteins. (A) Chemical structure of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1 ) active site showing Zn²⁺ coordination with Cys208, His220, and a bridging sulfide. (B) Catalytic cycle of manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), converting superoxide radicals (O₂⁻) into hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and water.

Figure 6.

Catalytic mechanisms of metalloprotein inhibition and detoxification. (A) Structural representation of an α-aminophosphonate inhibitor reversibly coordinating Zn²⁺ in the NDM-1 active site. (B) Mn-SOD catalytic cycle illustrating manganese-mediated detoxification of superoxide radicals. .

Figure 6.

Catalytic mechanisms of metalloprotein inhibition and detoxification. (A) Structural representation of an α-aminophosphonate inhibitor reversibly coordinating Zn²⁺ in the NDM-1 active site. (B) Mn-SOD catalytic cycle illustrating manganese-mediated detoxification of superoxide radicals. .

Figure 7.

Zinc-coordinated inhibitors of bacterial resistance and lipid biosynthesis. (A) Q-aminophosphonate coordinates Zn²⁺ via hydroxyl, amino, and carbonyl groups, reducing NDM-1 activity in resistant strains. (B) LpxC inhibitor coordinates Zn²⁺ through an amide and aromatic ring, improving pharmacokinetics by shielding metabolism, limiting efflux, and mimicking substrates to block lipid A biosynthesis.

Figure 7.

Zinc-coordinated inhibitors of bacterial resistance and lipid biosynthesis. (A) Q-aminophosphonate coordinates Zn²⁺ via hydroxyl, amino, and carbonyl groups, reducing NDM-1 activity in resistant strains. (B) LpxC inhibitor coordinates Zn²⁺ through an amide and aromatic ring, improving pharmacokinetics by shielding metabolism, limiting efflux, and mimicking substrates to block lipid A biosynthesis.

Figure 8.

Metal-driven strategies for bacterial disruption. (A) ATCUN motif–based compounds cycle Cu²⁺/Cu⁺ to generate ROS, damaging bacterial biomolecules. (B) Metallo-PROTACs combine a metal-binding warhead, linker, and degron to promote ClpXP-mediated protein degradation. (C) Responsive delivery platforms use siderophore-conjugated carriers and enzyme cues to release payloads near biofilms and intracellular niches.

Figure 8.

Metal-driven strategies for bacterial disruption. (A) ATCUN motif–based compounds cycle Cu²⁺/Cu⁺ to generate ROS, damaging bacterial biomolecules. (B) Metallo-PROTACs combine a metal-binding warhead, linker, and degron to promote ClpXP-mediated protein degradation. (C) Responsive delivery platforms use siderophore-conjugated carriers and enzyme cues to release payloads near biofilms and intracellular niches.

Figure 9.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the effect of a metalloprotein inhibitor on bacterial metabolism. The illustration shows how an inhibitor interacts with a bacterial metalloprotein, leading to disrupted cellular metabolism. This disruption impairs key physiological functions and results in reduced bacterial growth and virulence. The schematic emphasizes the therapeutic potential of targeting metalloproteins as a strategy for antimicrobial intervention.

Figure 9.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the effect of a metalloprotein inhibitor on bacterial metabolism. The illustration shows how an inhibitor interacts with a bacterial metalloprotein, leading to disrupted cellular metabolism. This disruption impairs key physiological functions and results in reduced bacterial growth and virulence. The schematic emphasizes the therapeutic potential of targeting metalloproteins as a strategy for antimicrobial intervention.

Figure 10.

Mechanism of ferric siderophore import and therapeutic intervention points in bacterial cells. (A) Ferric siderophore secretion into the extracellular environment initiates iron acquisition. (B) Enterobactin binds Fe³⁺ with high affinity and is recognized by outer membrane transporter FepA. (C) FepA facilitates translocation of the ferric siderophore complex across the outer membrane. (D) ATPase and (E) ADPase provide energy for transport via the TonB-dependent system. (F) The ferric complex is imported into the cytoplasm for metabolic use. (G) Potential therapeutic targets include siderophore biosynthesis, transporter inhibition, and energy-coupling disruption.

Figure 10.

Mechanism of ferric siderophore import and therapeutic intervention points in bacterial cells. (A) Ferric siderophore secretion into the extracellular environment initiates iron acquisition. (B) Enterobactin binds Fe³⁺ with high affinity and is recognized by outer membrane transporter FepA. (C) FepA facilitates translocation of the ferric siderophore complex across the outer membrane. (D) ATPase and (E) ADPase provide energy for transport via the TonB-dependent system. (F) The ferric complex is imported into the cytoplasm for metabolic use. (G) Potential therapeutic targets include siderophore biosynthesis, transporter inhibition, and energy-coupling disruption.

Table 1.

Selective bacterial metalloprotein inhibitors and their reported activities. Representative inhibitors are listed with their mechanisms of action, delivery methods, selectivity indices, toxicity profiles, and clinical development stages. Entries were identified as described in the Introduction.

Table 1.

Selective bacterial metalloprotein inhibitors and their reported activities. Representative inhibitors are listed with their mechanisms of action, delivery methods, selectivity indices, toxicity profiles, and clinical development stages. Entries were identified as described in the Introduction.

| Clinical Stage |

Toxicity Profile |

Selectivity Index |

Delivery Method |

Target Mechanism |

Agent |

| Preclinical |

Potential host metal depletion |

Moderate |

Systemic (small molecule) |

Chelates Fe³⁺, disrupts metalloenzymes |

2,2′-Bipyridyl [1,14] |

| Experimental (in vivo) |

Low (host-independent) |

High |

Endogenous bacterial secretion |

Siderophore-mediated Fe³⁺ sequestration |

Enterobactin (overproduced) [1,4] |

| Phase I/II clinical trials |

Minimal off-target effects |

High |

Intravenous or oral |

Zinc-binding at β-lactamase active site |

NDM-1 Inhibitors [10,11] |

| Preclinical |

Low toxicity, favorable pharmacokinetics |

High |

Topical/systemic nanoparticle |

Chelates Fe³⁺, inhibits biofilm formation |

OP607 [12,13] |

| Early-stage development |

Low systemic toxicity |

Very high |

Intravenous (biologic) |

Surface metalloprotein neutralization |

Antibody-based inhibitors [15,16] |

Table 2.

Key bacterial metalloprotein targets, their roles in virulence, and therapeutic strategies. The table outlines representative metalloproteins, associated pathogens, mechanisms, therapeutic approaches, supporting evidence, advantages, and limitations. Entries were identified as described in the Introduction.

Table 2.

Key bacterial metalloprotein targets, their roles in virulence, and therapeutic strategies. The table outlines representative metalloproteins, associated pathogens, mechanisms, therapeutic approaches, supporting evidence, advantages, and limitations. Entries were identified as described in the Introduction.

| Limitations |

Advantages |

Evidence |

Therapeutic Strategy |

Mechanism |

Pathogens |

Target Class |

| Selectivity challenges |

Unique bacterial targets |

In vitro inhibition |

Small molecule inhibitors |

Copper uptake & oxidative stress |

P. aeruginosa |

Copper Transport Proteins [26] |

| Resistance via transporter mutations |

Pathogen-specific |