Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Subjects

2.2. Polyclonal B Cell Stimulation

2.3. Murine B Cell Hybridoma

2.4. Recombinant Proteins

2.5. B Cell ImmunoSpot® Assays

2.5.1. Antigen-Specific Human IgG B Cell ELISPOT

2.5.2. Pan Human IgG B cell ELISPOT

2.5.3. Murine B cell ELISPOT

2.5.4. Image Acquisition and SFU Counting

2.6. Statistical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rationale

3.2. Studies of IgG+ B Cell Hybridomas in ImmunoSpot Assays

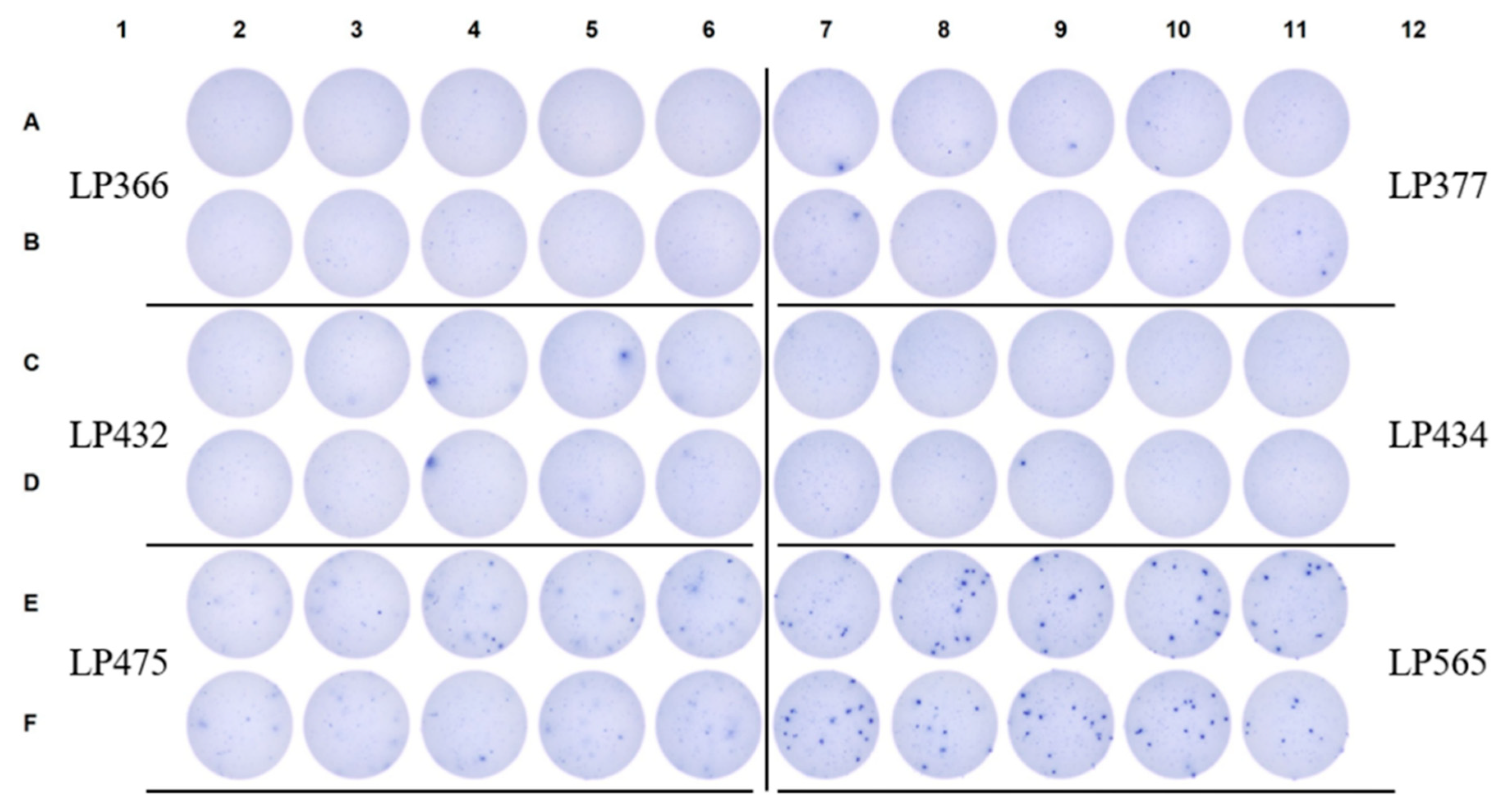

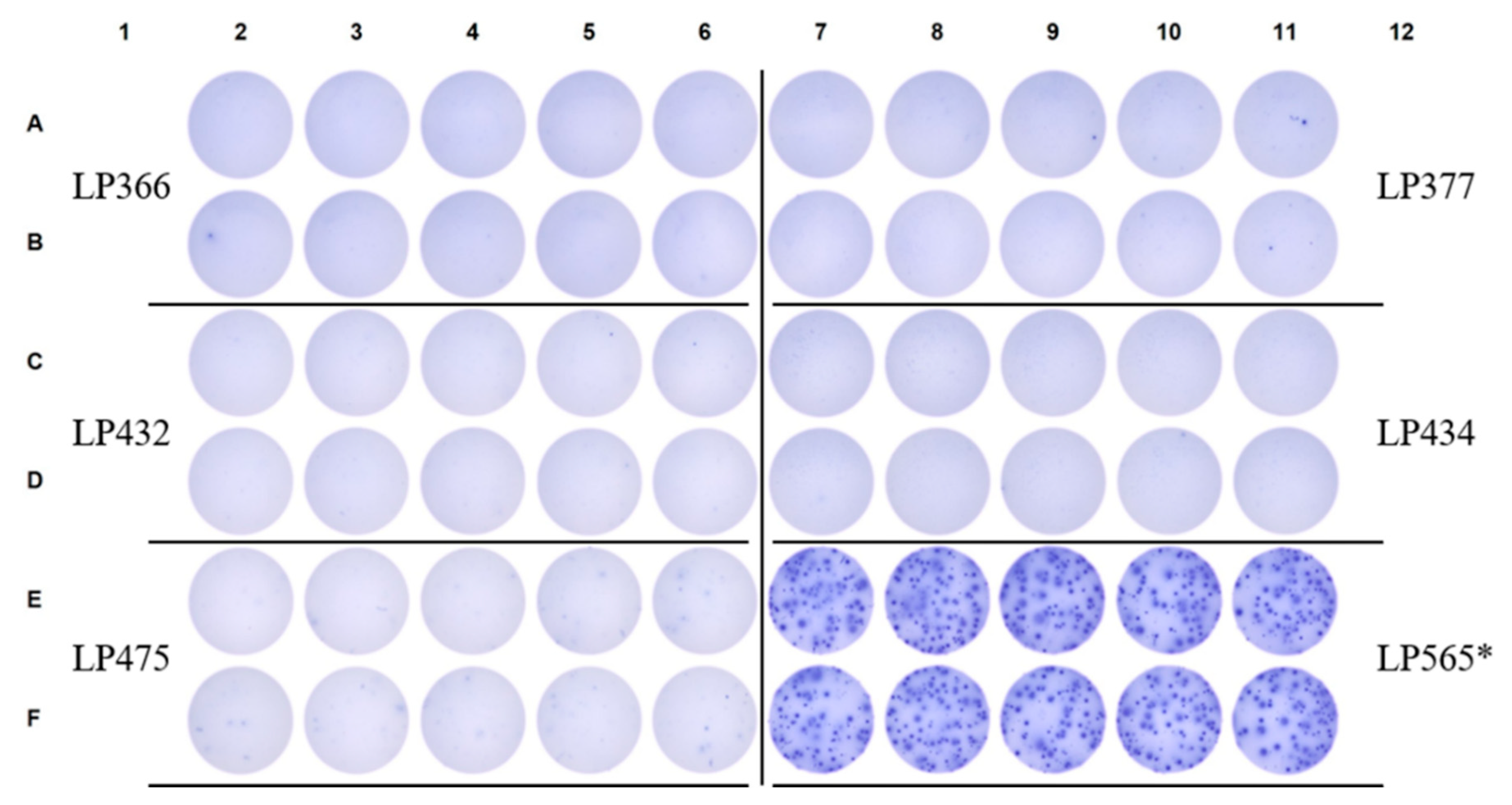

3.3. Studies of Bmem-Derived IgG+ ASCs in PBMC

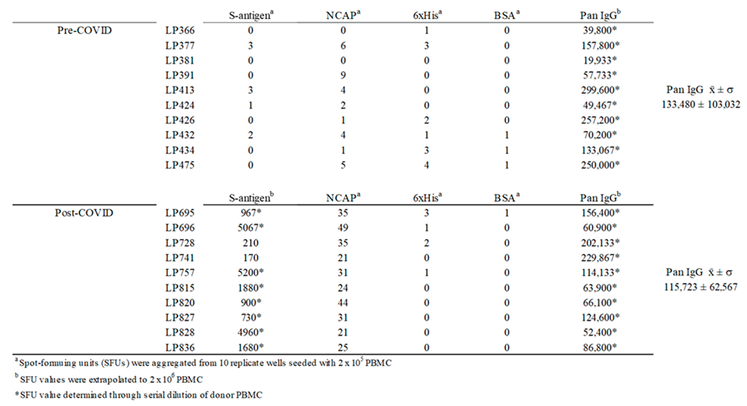

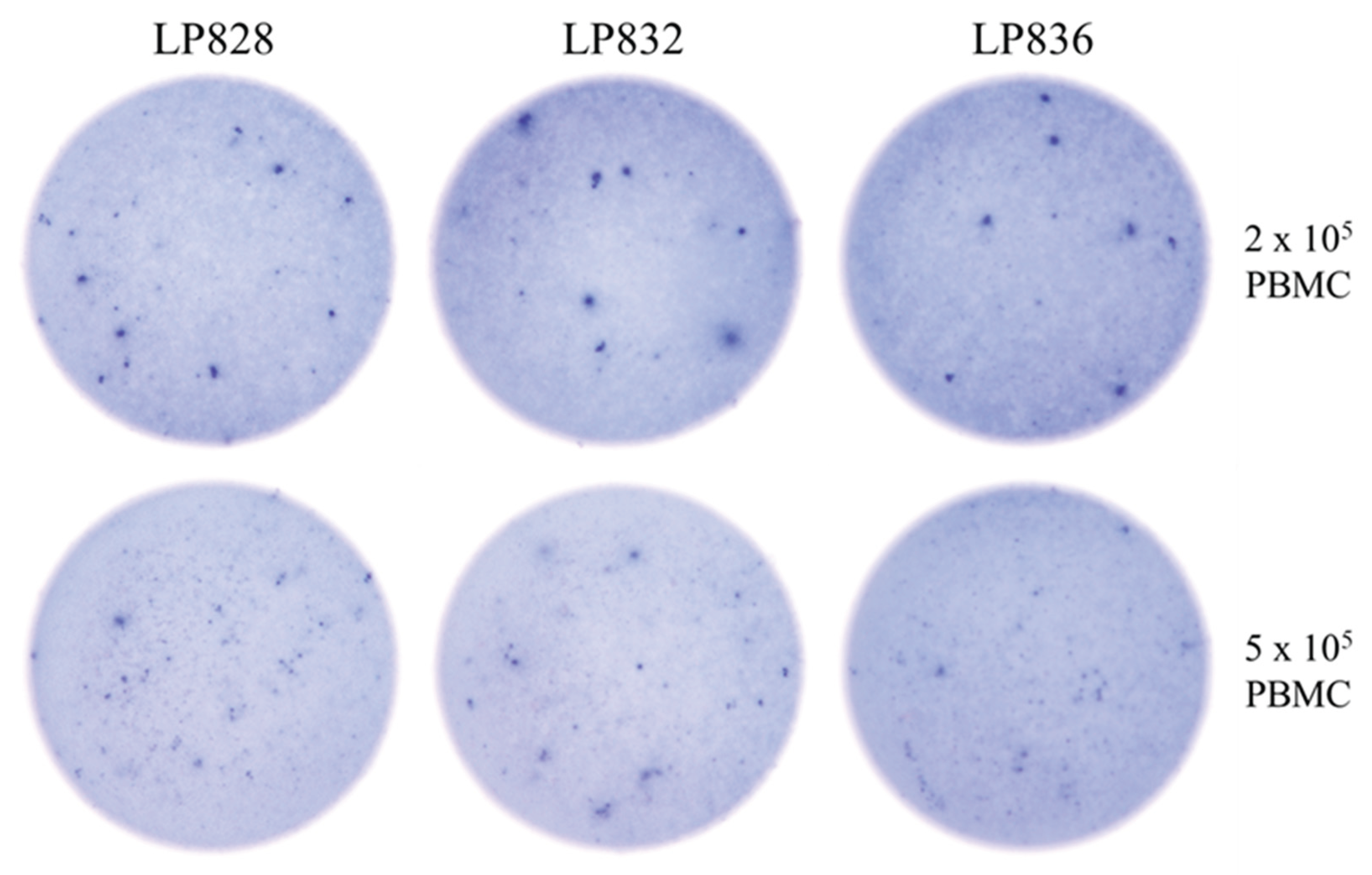

3.4. Improving the Detection Limit of Rare Antigen-Specific IgG+ Bmem in ImmunoSpot Assays

|

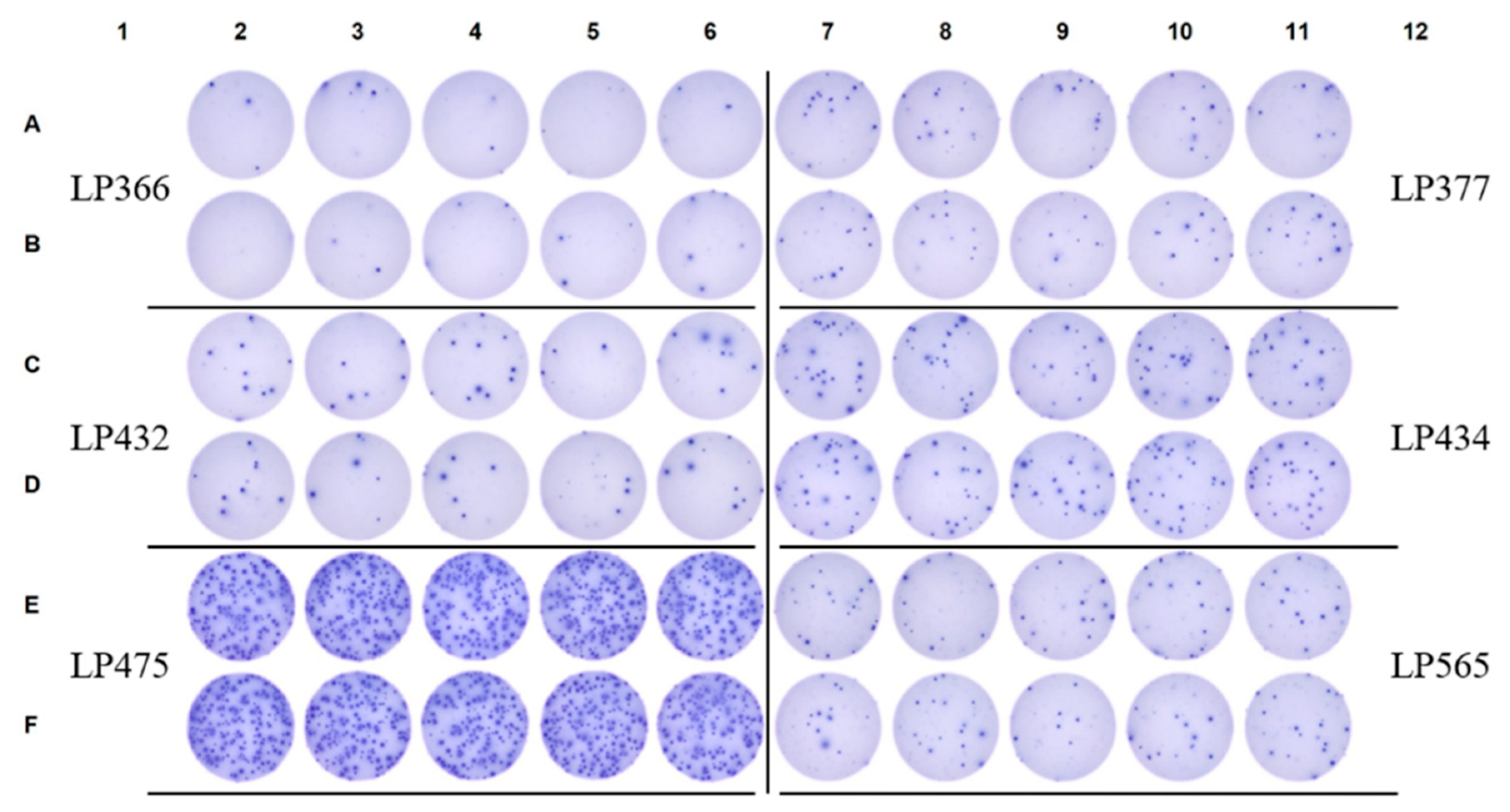

3.5. SFU Morphology Distinguishes Between Cognate and Cross-Reactive Bmem

4. Summary and Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elhanati, Y.; Sethna, Z.; Marcou, Q.; Callan, C.G., Jr.; Mora, T.; Walczak, A.M. Inferring processes underlying B-cell repertoire diversity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015, 370. [CrossRef]

- Mostoslavsky, R.; Alt, F.W.; Rajewsky, K. The lingering enigma of the allelic exclusion mechanism. Cell 2004, 118, 539-544. [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Weiss, Y.; Navon, Y.; Milo, I.; Azulay, N.; Keren, L.; Fuchs, S.; Ben-Zvi, D.; Noor, E.; Milo, R. The total mass, number, and distribution of immune cells in the human body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2308511120. [CrossRef]

- Cyster, J.G.; Allen, C.D.C. B Cell Responses: Cell Interaction Dynamics and Decisions. Cell 2019, 177, 524-540. [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.Z.; Hong, T.; Huang, C.; Huang, W.; Mu, Q. B cell memory: from generation to reactivation: a multipronged defense wall against pathogens. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 117. [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, M.; Kwak, K.; Pierce, S.K. B cell memory: building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Moran, I.; Shinnakasu, R.; Phan, T.G.; Kurosaki, T. Generation of memory B cells and their reactivation. Immunol Rev 2018, 283, 138-149. [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Eludin, Z.; Drabovich, A.P. Redefining serological diagnostics with immunoaffinity proteomics. Clin Proteomics 2023, 20, 42. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, H.R.; Parai, D.; Dash, G.C.; Peter, A.; Sahoo, S.K.; Pattnaik, M.; Rout, U.K.; Nanda, R.R.; Pati, S.; Bhattacharya, D. IgG antibody response against nucleocapsid and spike protein post-SARS-CoV-2 infection. Infection 2021, 49, 1045-1048. [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.G.; Lustig, Y.; Cohen, C.; Fluss, R.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Doolman, R.; Asraf, K.; Mendelson, E.; Ziv, A.; et al. Waning Immune Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine over 6 Months. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, e84. [CrossRef]

- Seow, J.; Graham, C.; Merrick, B.; Acors, S.; Pickering, S.; Steel, K.J.A.; Hemmings, O.; O'Byrne, A.; Kouphou, N.; Galao, R.P.; et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol 2020, 5, 1598-1607. [CrossRef]

- Achiron, A.; Gurevich, M.; Falb, R.; Dreyer-Alster, S.; Sonis, P.; Mandel, M. SARS-CoV-2 antibody dynamics and B-cell memory response over time in COVID-19 convalescent subjects. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021, 27, 1349 e1341-1349 e1346. [CrossRef]

- Winklmeier, S.; Eisenhut, K.; Taskin, D.; Rubsamen, H.; Gerhards, R.; Schneider, C.; Wratil, P.R.; Stern, M.; Eichhorn, P.; Keppler, O.T.; et al. Persistence of functional memory B cells recognizing SARS-CoV-2 variants despite loss of specific IgG. iScience 2022, 25, 103659. [CrossRef]

- Van Elslande, J.; Oyaert, M.; Lorent, N.; Vande Weygaerde, Y.; Van Pottelbergh, G.; Godderis, L.; Van Ranst, M.; Andre, E.; Padalko, E.; Lagrou, K.; et al. Lower persistence of anti-nucleocapsid compared to anti-spike antibodies up to one year after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2022, 103, 115659. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Koppert, S.; Becza, N.; Kuerten, S.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. Antibody Levels Poorly Reflect on the Frequency of Memory B Cells Generated following SARS-CoV-2, Seasonal Influenza, or EBV Infection. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, A.; Vizcarra, P.; Martin-Hondarza, A.; Gomez-Maldonado, S.; Haemmerle, J.; Velasco, H.; Casado, J.L. Impact of SARS-CoV-2-specific memory B cells on the immune response after mRNA-based Comirnaty vaccine in seronegative health care workers. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1002748. [CrossRef]

- Morell, A.; Terry, W.D.; Waldmann, T.A. Metabolic properties of IgG subclasses in man. J Clin Invest 1970, 49, 673-680. [CrossRef]

- Lightman, S.M.; Utley, A.; Lee, K.P. Survival of Long-Lived Plasma Cells (LLPC): Piecing Together the Puzzle. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 965. [CrossRef]

- Palm, A.E.; Henry, C. Remembrance of Things Past: Long-Term B Cell Memory After Infection and Vaccination. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1787. [CrossRef]

- Terlutter, F.; Caspell, R.; Nowacki, T.M.; Lehmann, A.; Li, R.; Zhang, T.; Przybyla, A.; Kuerten, S.; Lehmann, P.V. Direct Detection of T- and B-Memory Lymphocytes by ImmunoSpot(R) Assays Reveals HCMV Exposure that Serum Antibodies Fail to Identify. Cells 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Dan, J.M.; Mateus, J.; Kato, Y.; Hastie, K.M.; Yu, E.D.; Faliti, C.E.; Grifoni, A.; Ramirez, S.I.; Haupt, S.; Frazier, A.; et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021, 371. [CrossRef]

- Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Pawelec, G.; Lehmann, P.V. The Importance of Monitoring Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells, and How ImmunoSpot Assays Are Suitable for This Task. Cells 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Becza, N.; Liu, Z.; Chepke, J.; Gao, X.H.; Lehmann, P.V.; Kirchenbaum, G.A. Assessing the Affinity Spectrum of the Antigen-Specific B Cell Repertoire via ImmunoSpot((R)). Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2768, 211-239. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Becza, N.; Stylianou, G.; Tary-Lehmann, M.; Todryk, S.M.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. SARS-CoV-2 Infection or COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination Elicits Partially Different Spike-Reactive Memory B Cell Responses in Naive Individuals. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Boonyaratanakornkit, J.; Taylor, J.J. Techniques to Study Antigen-Specific B Cell Responses. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1694. [CrossRef]

- Bozhkova, M.; Gardzheva, P.; Rangelova, V.; Taskov, H.; Murdjeva, M. Cutting-edge assessment techniques for B cell immune memory: an overview. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2024, 38, 2345119. [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, G.; Cookson, S.; T. Nassif, J.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; V. Lehmann, P.; M. Todryk, S. A comparison of Flow Cytometry- versus ImmunoSpot- or Supernatant-Based Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Specific Memory B Cells in Peripheral Blood. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, A.; Pazos-Castro, D.; Urselli, F.; Grydziuszko, E.; Mann-Delany, O.; Fang, A.; Walker, T.D.; Guruge, R.T.; Tome-Amat, J.; Diaz-Perales, A.; et al. Production and use of antigen tetramers to study antigen-specific B cells. Nat Protoc 2024, 19, 727-751. [CrossRef]

- Becza, N.; Yao, L.; Lehmann, P.V.; Kirchenbaum, G.A. Optimizing PBMC Cryopreservation and Utilization for ImmunoSpot((R)) Analysis of Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.C. The Emergence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Annu Rev Virol 2024, 11, 21-42. [CrossRef]

- https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/vaccines. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/vaccines (accessed on.

- Yao, L.; Becza, N.; Maul-Pavicic, A.; Chepke, J.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. Four-Color ImmunoSpot((R)) Assays Requiring Only 1-3 mL of Blood Permit Precise Frequency Measurements of Antigen-Specific B Cells-Secreting Immunoglobulins of All Four Classes and Subclasses. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2768, 251-272. [CrossRef]

- Pinna, D.; Corti, D.; Jarrossay, D.; Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. Clonal dissection of the human memory B-cell repertoire following infection and vaccination. Eur J Immunol 2009, 39, 1260-1270. [CrossRef]

- Franke, F.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Kuerten, S.; Lehmann, P.V. IL-21 in Conjunction with Anti-CD40 and IL-4 Constitutes a Potent Polyclonal B Cell Stimulator for Monitoring Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- The Following Reagent was Deposited by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Obtained through BEI Resources; N., N.S.-R.C., Isolate USA-WA1/2020, Heat Inactivated, NR-52286. Available online: https://www.; 2021), b.o.C.a.N.-a.a.o.M.

- Hsieh, C.L.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Schaub, J.M.; DiVenere, A.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K.C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A.G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Structure-based Design of Prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spikes. bioRxiv 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sautto, G.A.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Abreu, R.B.; Ecker, J.W.; Pierce, S.R.; Kleanthous, H.; Ross, T.M. A Computationally Optimized Broadly Reactive Antigen Subtype-Specific Influenza Vaccine Strategy Elicits Unique Potent Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies against Hemagglutinin. J Immunol 2020, 204, 375-385. [CrossRef]

- Koppert, S.; Wolf, C.; Becza, N.; Sautto, G.A.; Franke, F.; Kuerten, S.; Ross, T.M.; Lehmann, P.V.; Kirchenbaum, G.A. Affinity Tag Coating Enables Reliable Detection of Antigen-Specific B Cells in Immunospot Assays. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Karulin, A.Y.; Katona, M.; Megyesi, Z.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. Artificial Intelligence-Based Counting Algorithm Enables Accurate and Detailed Analysis of the Broad Spectrum of Spot Morphologies Observed in Antigen-Specific B-Cell ELISPOT and FluoroSpot Assays. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2768, 59-85. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Kurosaki, T. Memory B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2024, 24, 5-17. [CrossRef]

- Weskamm, L.M.; Dahlke, C.; Addo, M.M. Flow cytometric protocol to characterize human memory B cells directed against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antigens. STAR Protoc 2022, 3, 101902. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, P.V.; Karulin, A.Y.; Becza, N.; Yao, L.; Liu, Z.; Chepke, J.; Maul-Pavicic, A.; Wolf, C.; Koppert, S.; Valente, A.V.; et al. Theoretical and practical considerations for validating antigen-specific B cell ImmunoSpot assays. J Immunol Methods 2025, 537, 113817. [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.M.; Ansari, A.M.; Frater, J.; Klenerman, P.; Dunachie, S.; Barnes, E.; Ogbe, A. The impact of pre-existing cross-reactive immunity on SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccine responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 304-316. [CrossRef]

- Changrob, S.; Yasuhara, A.; Park, S.; Bangaru, S.; Li, L.; Troxell, C.A.; Halfmann, P.J.; Erickson, S.A.; Catanzaro, N.J.; Yuan, M.; et al. Common cold embecovirus imprinting primes broadly neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 S2. J Exp Med 2025, 222. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Obraztsova, A.; Shang, F.; Oludada, O.E.; Malapit, J.; Busch, K.; van Straaten, M.; Stebbins, E.; Murugan, R.; Wardemann, H. Affinity-independent memory B cell origin of the early antibody-secreting cell response in naive individuals upon SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Immunity 2024, 57, 2191-2201 e2195. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).