1. Introduction

Immune monitoring for clinical trials and routine diagnostics primarily relies on detecting antigen-specific antibodies in the serum/plasma of test subjects. Such pre-existing antibodies, however, reflect only the ability of the host to immediately combat an invading antigen. This occurs under optimal conditions through instantaneous neutralization (blockade of receptor binding domains and/or impairing the antigen’s association with host cells), complement fixation, precipitation through formation of immune complexes, and/or opsonization of the antigen to promote its clearance. Accordingly, preformed serum antibodies constitute the first wall of acquired humoral defense [

1]. Importantly, antibodies in serum are relatively short-lived molecules which possess a half-life of ~3 weeks or less when not associated with immunoglobulin (Ig)-binding receptors such as the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) [

2]. Their continued presence in serum therefore depends on ongoing replenishment by antibody-secreting plasma cells. While plasma cells

per se can be long-lived [

3], competition for survival niches located primarily in the bone marrow frequently limits their lifespan [

4,

5]. Subsequently, antibody levels can decline within months after vaccinations or infections [

6,

7,

8], leaving the host susceptible to (re-)infection. Serum antibodies therefore provide fading evidence for past immune encounters and of established immunological memory.

When pre-existing antibodies can no longer prevent (re-)infections, B

mem serve as the second wall of acquired humoral defense [

1]. B

mem , in contrast to antibodies in plasma/serum, are long-lived in vivo [

9]. While (unlike plasma cells/blasts) B

mem do not secrete antibodies constitutively, upon antigen reencounter they rapidly give rise to secondary immune responses that produce new generations of plasma cells and B

mem. Having undergone clonal expansion, Ig class switching, and affinity maturation during previous immune encounter(s), B

mem-derived secondary antibody responses are faster and more robust compared to the initial antigen encounter. Therefore, studying B

mem unveils the immune potential that has been acquired to combat future antigen challenges when pre-existing antibodies are no longer sufficient to convey protection.

When interpreting the frequently discordant results obtained by measuring antigen-specific antibody levels vs. B

mem in blood [

7], it must be considered that the differentiation of B cells into the plasma cell and B

mem lineages follows different instructive pathways (reviewed in [

10,

11]). During an immune response, antigen-specific (naïve and/or memory) B cells become activated and subsequently are recruited into germinal centers (GCs) within secondary lymphoid organs (spleen and/or lymph nodes) where they undergo additional clonal expansions while also acquiring somatic hypermutations (SHM) within the genes encoding their B cell antigen receptors (BCR). Subsequently, as the consequence of SHM, the daughter cells (these are called GC B cells at this differentiation stage) will express BCRs with slightly different affinity for the eliciting antigen. As these SHM are random, some of the daughter cells will acquire an increased affinity, while others will remain unchanged or even exhibit a reduced affinity for the antigen in comparison to the parental B cell. Through positive selection, the GC B cell subclones with an increased affinity for the eliciting antigen undergo further rounds of proliferation and acquisition of SHM with only the subclones achieving the highest affinity for the eliciting antigen eventually being recruited into the plasma cell lineage. This process is collectively termed affinity maturation. In contrast, antigen-specific B cells possessing a reduced affinity for the eliciting antigen will exit the germinal center and instead join the B

mem cell compartment [

11]. As a consequence, the plasma cells (and hence serum antibodies) reflect on the high affinity end of the B cell repertoire generated through the immune response, whereas the B

mem repertoire will also include subclones with lower affinity for the antigen. The immunological significance of this dichotomy is that plasma cells predominantly contribute to protection against the original version of an invading infectious organism (i.e., the “homotype”) whereas B

mem also prepare the host for encounters with newly emerging future variants (“heterotypes”): while some B

mem subclones will possess a modest affinity for the homotype, they may fortuitously be endowed with an increased affinity for a heterotype and enable an anamnestic (secondary) antibody responses even at the first encounter with the heterotype [

12]. Because of the distinct requirements for plasma- and B

mem lineage differentiation, and the variability in plasma cell life spans, the frequencies of antigen-specific B

mem and serum antibody levels are frequently discordant [

7] and the former are more reliable in revealing past infections than plasma/serum antibody titers ([

7] and Kirchenbaum,

manuscript in preparation). Circulating antibodies and B

mem, reflecting wall 1

vs. 2, respectively, reveal different aspects of acquired humoral immunity, the understanding of which is equally important for immune monitoring.

For all the above reasons, the need has emerged to include assessment of antigen-specific B

mem, encompassing their affinity distribution and cross-reactivity profiles, into immunodiagnostics [

13]. Once isolated from the body, serum antibodies are stable and can be stored and shipped at 4◦C (or frozen) for years. Moreover, as they detect abundant molecules in solution, many antibody-detecting tests can be performed with minute quantities of serum. Both of these properties facilitate sero-diagnostics and explain its widespread usage. B

mem in contrast, perish shortly after isolation from the body, and either need to be tested right away, or cryopreserved for later testing [

14,

15]. Furthermore, because antigen-specific B

mem are rare among peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), typically constituting << 0.1% thereof [

16], substantial numbers of PBMC are commonly required for their reliable detection and study. Optimizing PBMC utilization for B

mem analysis is therefore critical for the inclusion of these important assays in the immune diagnostic armamentarium; this is the focus of the present communication.

Antigen-specific B

mem are best detected via the specificity of the surface BCR they express, or alternatively, based on the specificity of the antibody they secrete following terminal differentiation. One technique suitable for this purpose is staining PBMC with labelled antigen probes, followed by the identification of antigen probe-labelled B cells by flow cytometry [

16,

17]. The other technique relies on detecting antigen-specific B cells via the antibody secretory footprint they generate when seeded onto antigen-coated membranes [

18,

19]: this test system is called ELISPOT (enzyme linked immunosorbent spot assay) when the detection of the antigen-bound antibodies occurs through enzyme-catalyzed precipitation and deposition of a visible substrate, or FluoroSpot, if fluorescence-tagged detection antibodies are used. As both assay variants follow the same basic principle and differ only in the means of visualizing the secretory footprints, here they are collectively termed ImmunoSpot. In this communication we focus exclusively on ImmunoSpot assays because, compared to antigen probe staining, B cell ImmunoSpot assays require less PBMC, are more suitable for high-throughput work flows, can be automated, and can be readily validated for clinical testing [

15].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Need for Testing PBMC in B Cell ImmunoSpot Assays in Serial Dilution

Having pioneered an affinity capture coating (ACC) strategy for ImmunoSpot [

24] (illustrated in

Supplemental Figure S1A), that facilitates development of B cell ImmunoSpot assays detecting B

mem specific for essentially any antigen, we established such assays for infectious disease-related antigens to which most humans have likely been exposed, and thus against which B

mem would have been generated. These were the Spike (S-antigen) and Nucleocapsid (NCAP) proteins of the ancestral Wuhan-Hu-1 strain of SARS-CoV-2, hemagglutinin (HA) proteins representing seasonal influenza A viruses (CA/09, H1N1 or TX/12, H3N2), seasonal influenza B virus (Phuket/13, Yamagata lineage), Epstein-Barr virus (EBNA1), and human cytomegalovirus (gH pentamer complex). Enabled by the new approach, we set out to screen a library of PBMC obtained from healthy adult donors for the presence of B

mem with reactivity against this antigen panel. Of note, the PBMC samples were collected in May 2022 or later, at which point the majority of donors had either been infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and/or received one or more doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

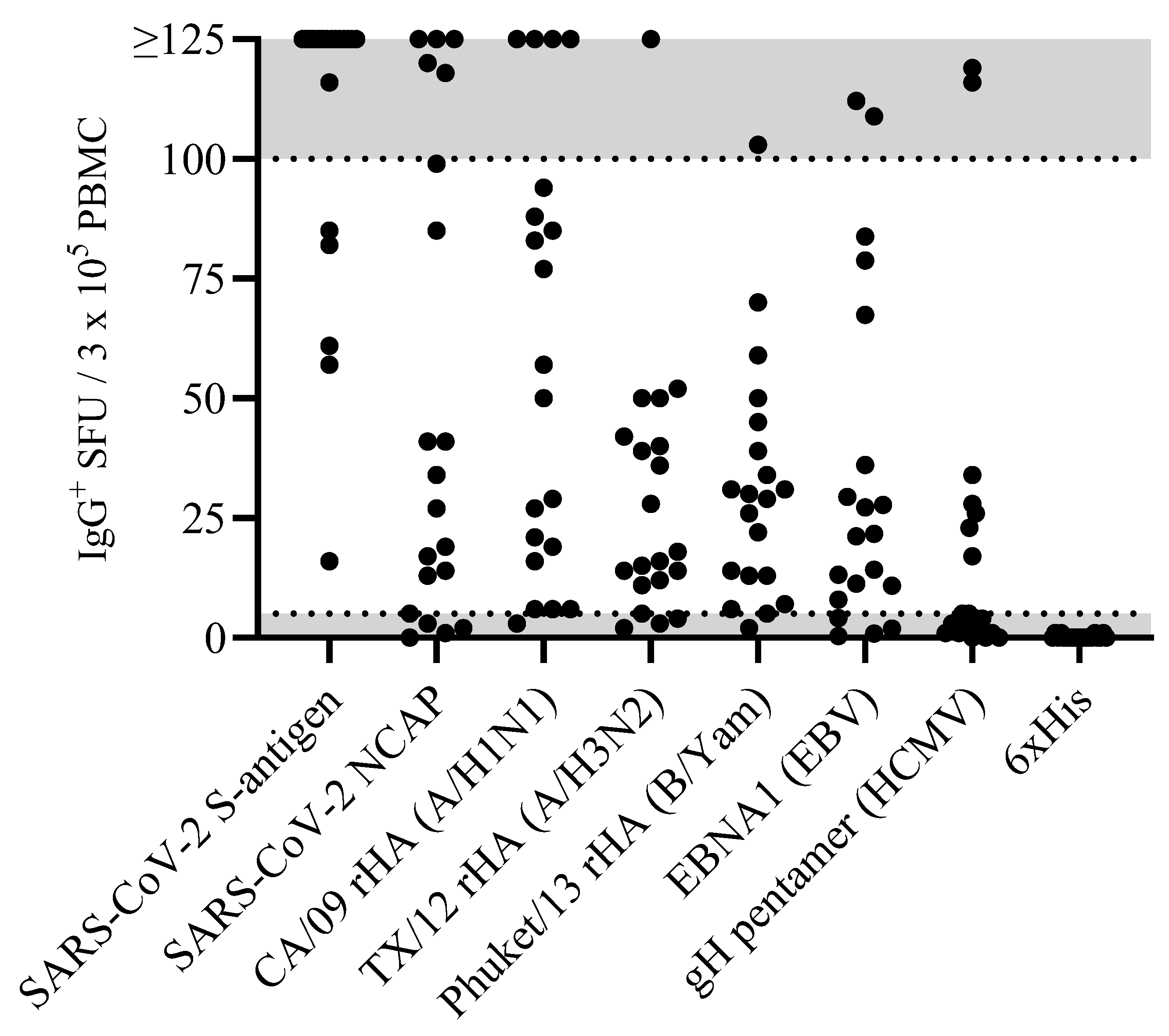

As commonly done for functional assays, including the traditional (T and) B cell ImmunoSpot approach, in our intial screening we tested for IgG

+ antibody-secreting cell (ASC) reactivity to each antigen at a fixed cell number of 3 x 10

5 PBMC per well. At this seeding density the PBMC sediment into a monolayer on the bottom of the 96 well plate; which is ideal for the detection of secretory footprints originating from rare individual lymphocytes using the ImmunoSpot approach [

26]. Moreover, samples were tested in duplicate to counter well-to-well variatiations that can be expected in particular when detecting low frequency events [

15,

27].

Accounting for the possibility that the frequency of B

mem specific for any given antigen in a PBMC test sample can be quite low, it seemed justifiable to test the PBMC at a cell input close to the monolayer maximum to ensure that even antigen-specific B

mem occurring at low frequencies could be detected. Raw data obtained for 20 representative donors against the 8 antigens in our panel are shown in

Figure 1. Notably, the number of antigen-reactive IgG

+ ASC varied considerably between individual donors, ranging from above the upper limit of quantifcation (ULOQ) (> 125 SFU per well, see below) to below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ, < 5 SFU/well). The data also revealed that no donor exhibited a consistently high or low responder status against all antigens in the panel; to the contrary, in line with the premise that each individual possesses a unique exposure history to environmental pathogens [

28], the magnitude of viral antigen-reactive IgG

+ ASC detected within and among different donors varied greatly (

Supplemental Table S1). Moreover, a spectrum of secretory footprint morphologies was often observed within the same assay well, as well as distinct morphologies in wells coated with different viral antigens (

Supplemental Figure S2). Therefore, these data serve to illustrate that testing PBMC at a fixed number is not suited for reliably establishing the frequency of antigen-specific IgG

+ B

mem cells in ImmunoSpot assays.

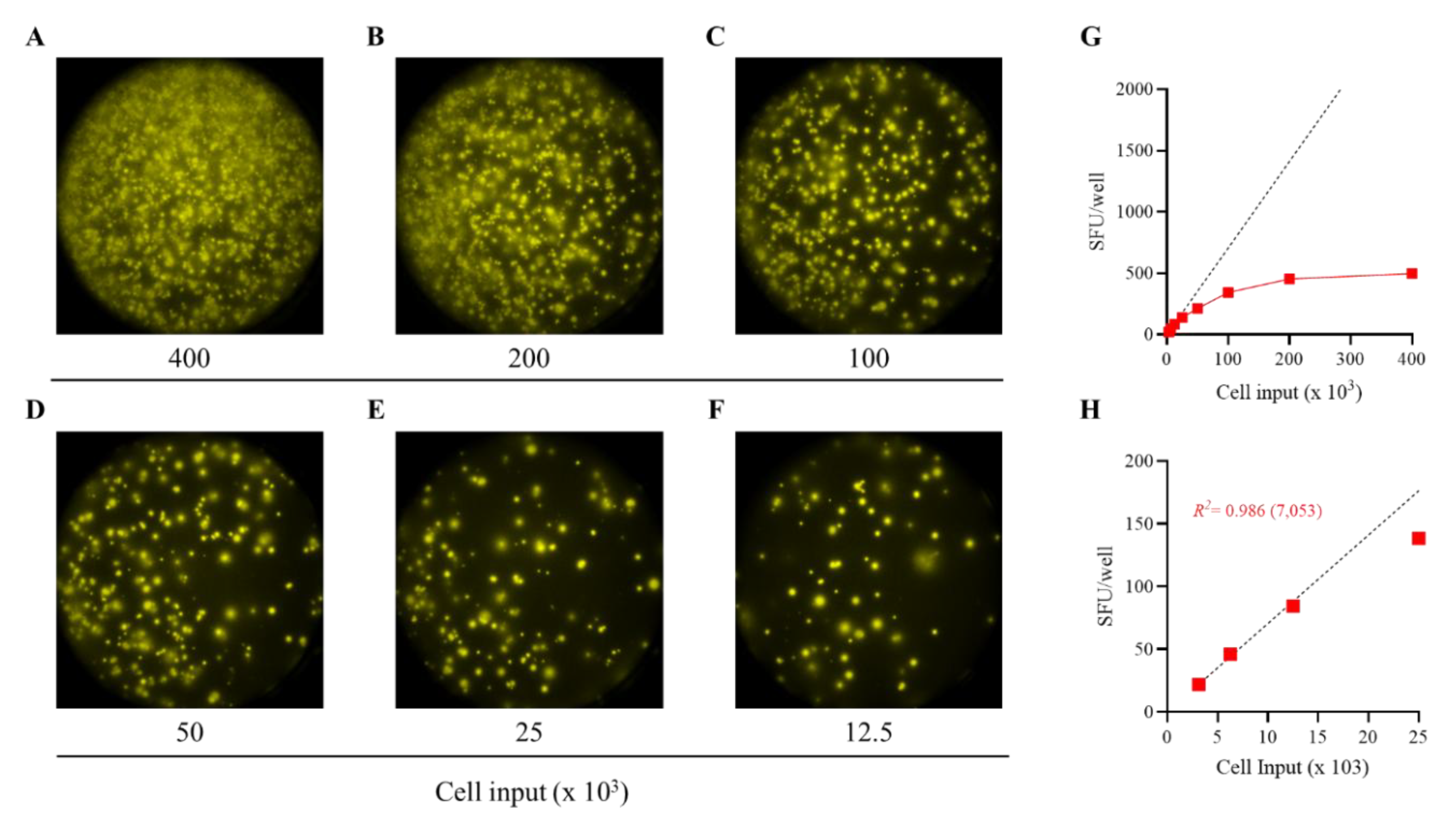

To more precisely determine the frequency of antigen-specific IgG

+ B

mem in donors that initially yielded a result above the assay’s ULOQ, we re-evaluated such antigen/PBMC combinations using a 2-fold serial dilution approach. As shown for a representative sample in

Figure 2, a close to perfect linear relationship was seen between the number of SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S-antigen)-specific IgG

+ secretory footprints (spot forming units, SFU) counted and PBMC plated, but only when the antigen-specific SFU counts were less than 100 per well (

Figure 2H); at higher cell inputs for this antigen/donor combination the confluence of SFU and elevated membrane staining (occuring due to an ELISA effect in which antibodies escape into the supernatant and then subsequently bind to the antigen-coated membrane distally from the source ASC —visible in

Figure 2A-C) resulted in undercounting of individual SFU (

Figure 2G). The data show that secretory footprints of individual ASC could be accurately detected under 100 SFU/well, constituting the ULOQ for this particular donor. For other donors, owing either to variable antigen-specfic SFU morphologies and/or fortuitously finding the optimal serial dilution window, the ULOQ can be slightly lower or higher than 100 SFU/well. Taking this into consideration, we denoted a “gray zone” as the ULOQ in

Figure 1. Nevertheless, for antigen-specific assays, the linearity region of the curve rarely exceeds 125 SFU/well (data not shown).

The LLOQ can be conservatively set at 5 SFU/well. According to Poisson’s rule, which applies when measuring antigen-specific lymphocytes [

15], the well-to-well variation in SFU generated by rare ASC increases dramatically at lower precursor frequencies. Therefore, in such instances, a multitude of replicates would be required to firmly establish their actual abundance in a test sample. Importantly, only in a narrow window, between 125 and 10 SFU/well are antigen-specific SFU counts reliable for frequency calculations. Depending on the frequency of antigen-specific ASC in a test sample, as well as the resulting secretory footprint morphologies, the ideal “Goldilocks range” for frequency calculations will be unique to each PBMC/antigen combination and hence can only be consistently established using a serial dilution testing approach. Serial dilutions are therefore necessary for achieving accurate B

mem frequency measurements in PBMC samples in which antigen-specific B

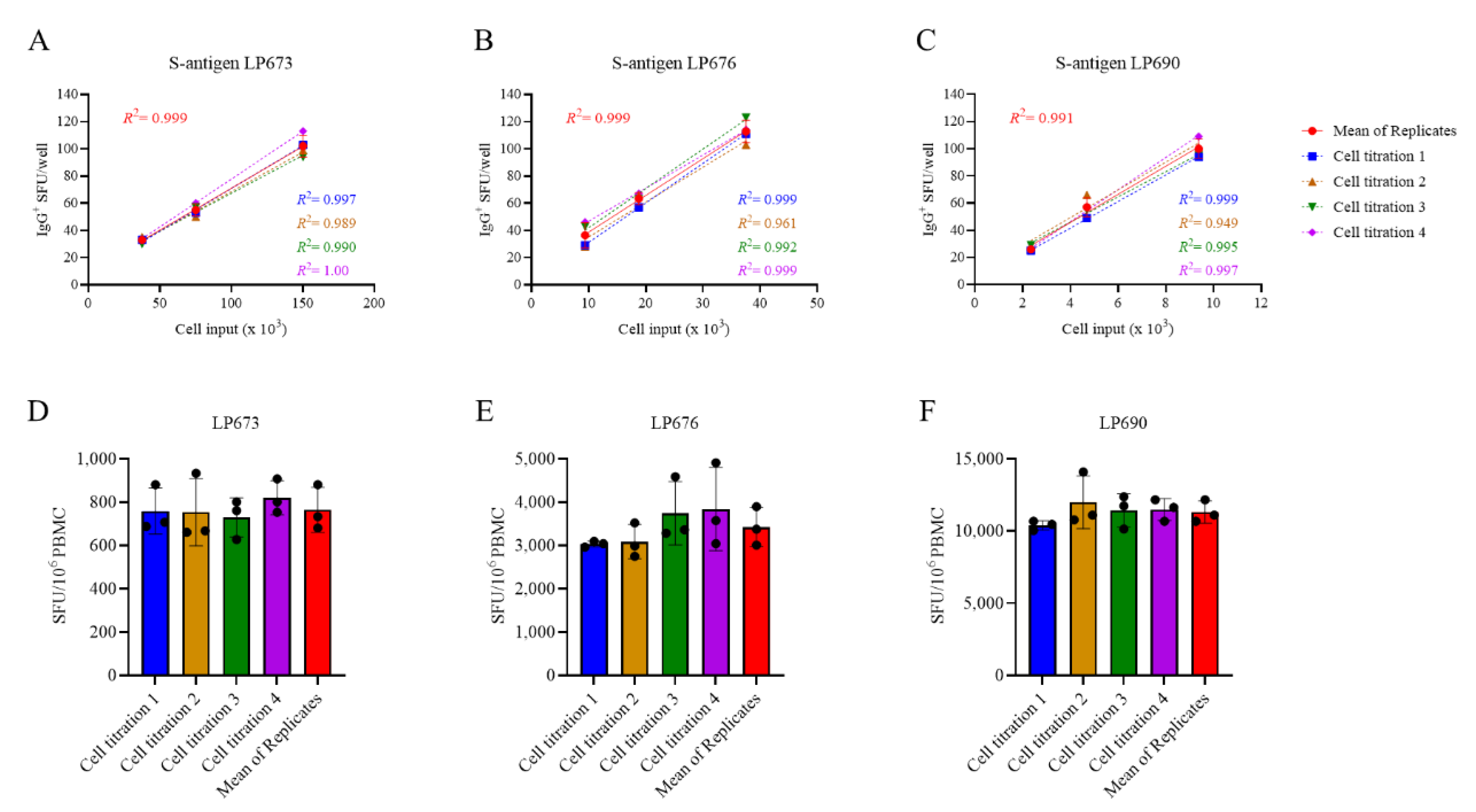

mem-derived ASC are abundant, but this increases the number of PBMC required for testing. Observing the close to perfect linear relationship between PBMC numbers plated and SFU detected per well, we sought to test the hypothesis that the serial dilution strategy itself could substitute for the reliance on technical replicates. In

Figure 3A-C, PBMC from three SARS-CoV-2 S-antigen-reactive subjects were serially diluted in four replicate wells for each dilution—SFU counts are shown for the Goldilocks range of <125 SFU/well only. The mean SFU counts at the designated cell inputs were first calculated, and it was established that the mean SFU counts originating from 2-fold serially diluted PBMC closely followed a linear function. Moreover, very similar regression lines were also obtained when the same calculations were performed using each of the replicates separately. Moreover, frequencies were calculated by extrapolation using either the individual SFU counts within a singlet serial dilution or using the mean counts from the quadruplicates (

Figure 3D-F). In each instance, the frequency of S-antigen-specific IgG

+ ASC per 10

6 PBMC was not significantly different between the respective singlet serial dilutions, nor were they different from the frequency determined using the mean SFU count from the four replicate wells at each cell dilution. The conclusion that singlet serial dilutions enable accurate frequency determinations was also confirmed for several additional antigens (data not shown), and for determining the frequency of ASC producing different classes of immunoglobulin (IgA, IgM or IgG) (

Supplemental Figure S3). Collectively, these data demonstrate that serial dilutions performed in single wells yield nearly equivalent data compared to results obtained from serial dilutions performed in quadruplicate; however, the former approach requires only a quarter as many PBMC, representing the first subtantial saving on blood volumes needed for routine testing.

3.2. Multiplexing B Cell ImmunoSpot Assays

Immunoglobulins (Ig) occur in four major classes (IgA, IgE, IgG, and IgM) and there are four IgG subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4). While all of these molecules share the task of specific antigen recognition, they can fundamentally differ in the effector functions they elicit upon binding to antigen. Comprehensive immune monitoring therefore needs to account for each of these Ig classes and subclasses, including the Bmem that are pre-committed to secrete them. Traditional ELISPOT assays measure one analyte at a time: one would need to run 4 single-color assays to cover all the Ig classes, plus an additional 4 single-color assays to segregate each of the IgG subclasses, necessitating increased PBMC utilization. Multiplexing the detection of Ig classes and/or IgG subclasses is the most practical solution to this requirement, and -as we will show in the following--can be accomplished without increasing the need for additional PBMC test material.

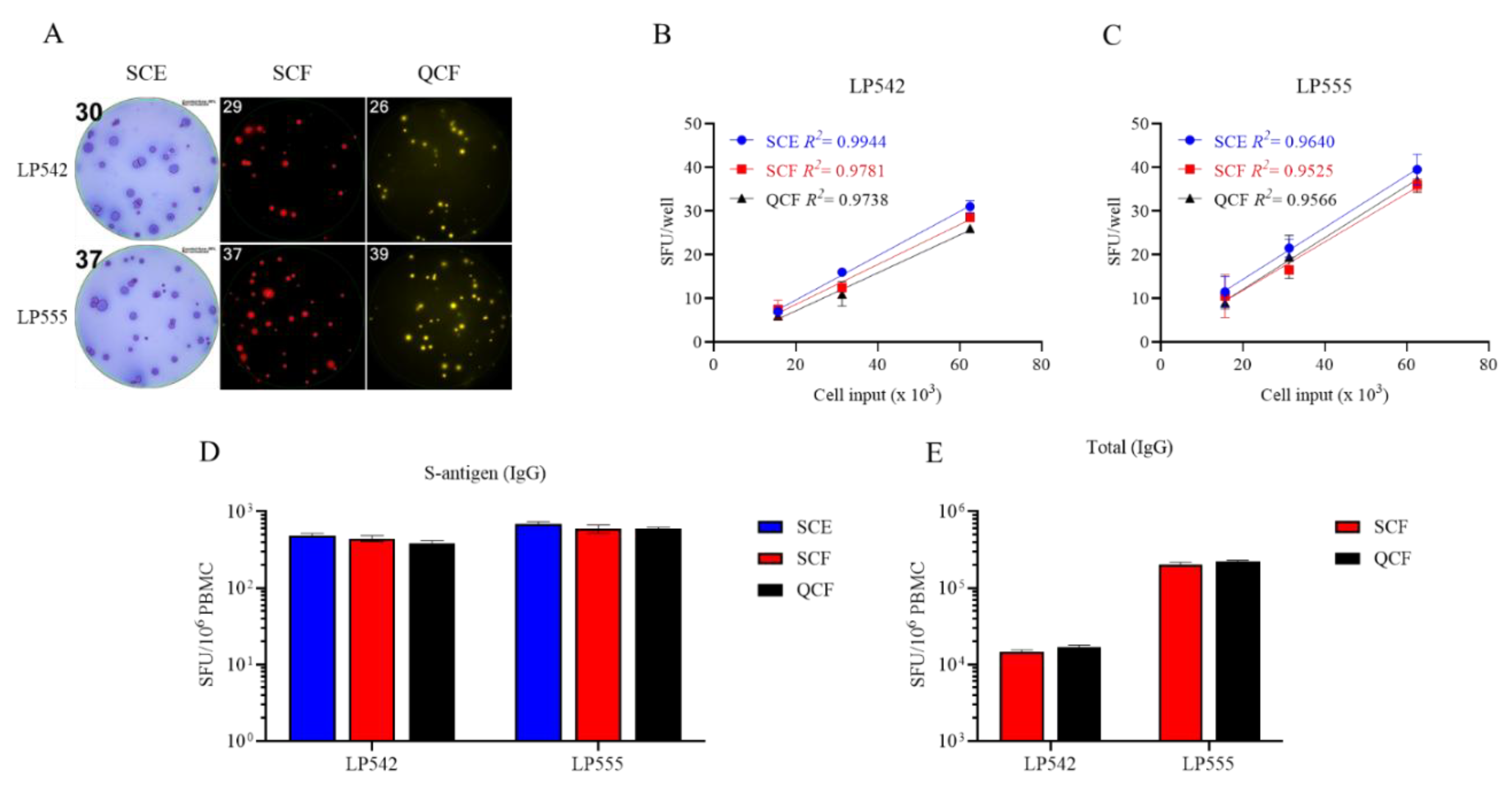

While 4-color B cell ImmunoSpot analysis is already commerically available [

14], so far its sensitivity for detecting the individal antigen-specific Ig analytes has not been formally established vs. their single color measurements. Multiplexing in FluoroSpot analysis is currently limited to four analytes owing to the requirement that each fluorescence-tagged detection antibody possess distinct excitation/emission properties that do not overlap, so that each can be visualized without leaking into the other’s detection channels and therefore permitting automated single-color counting in each color plane without the need for compensation [

14]. In systematic studies we have established here that traditional single-color enzymatic ELISPOT assays and four-color fluorescent analysis provide indistinguishable antigen-specific IgG SFU counts within the linear range (

Figure 4); however, in ELISPOT the linearity in S-antigen-specific SFU counts broke down earlier than FluoroSpot in large part due to the increased size of individual secretory footprints and elevated membrane staining in wells with a high density of SFU – both attributable to enzymatic amplification. Similarly, we previously demonstrated that pan (total) Ig SFU counts were also equivalent between single-color enzymatic ELISPOT and single- or four-color FluoroSpot assays [

20].

With this notion in mind, we systematically studied PBMC obtained from healthy human donors in order to determine the frequency of ASC that secrete the four Ig classes and the four IgG subclasses. Following five days of in vitro polyclonal stimulation, the donor PBMC were plated at 2 x 10

5 cells per well and then serially diluted 2-fold. The results shown in

Supplemental Table S2 established that a) even for a single Ig class or IgG subclass the frequency of pan Ig ASC can vary substantially between healthy individuals, and b) that in all individuals IgM-, IgG- and IgG1-secreting ASC substantially outnumbered ASC secreting other classes/subclasses. In most instances the SFU counts originating from IgM

+, IgG

+ or IgG1

+ ASC were above the linear range for accurate frequency calculations at the same PBMC inputs at which ASC secreting the rarer classes/subclasses (IgA, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4) were exceedingly infrequent, if not undetectable. Lastly, these studies established that – except if one is particularly interested in the rarer Ig classes and subclasses - starting the serial dilution at 2-3 x 10

4 PBMC per well is sufficient for multiplexed pan Ig measurements.

Systematic four-color ImmunoSpot studies conducted to establish the frequency of B

mem-derived ASC reactive with SARS-CoV-2 S-antigen representing the prototype Wuhan-Hu-1 strain were consistent with results shown in

Figure 1 for single-color IgG analysis (Yao et al, manuscript in preparation). Collectively, these data confirmed the prevalence of the IgG class, and specifically the IgG1 subclass, within the antigen-specific ASC compartment.

Based on the data presented, and all experience we gained so far, we recommend for initial B

mem characterization to perform tests in which the PBMC are serially diluted starting at 1-3 x 10

5 cells per well for each antigen, and at 1-3 x 10

4 PBMC per well for the pan Ig assay. Since these tests can each be conducted using a single well serial dilution approach without compromising the resolution of the results, and because the detection of four Ig classes or IgG subclasses can be multiplexed using four-color detection systems, even when starting with a 3 x 10

5 PBMC input, 1.2 x 10

6 cells from the polyclonal stimulation cultures are sufficient for measuring all four Ig classes and four IgG subclasses per antigen with an additional 1.2 x 10

5 cells needed for establishing the frequency of ASC producing each of the four Ig classes or IgG subclasses (irrespective of antigen specificity). The recommended plate layout for routine PBMC testing in B cell ImmunoSpot assays (

Supplemental Figure S4) accomodates frequency determinations for both antigen-specific and pan Ig B

mem of all classes and subclasses despite the considerable variability of frequencies in which such B

mem occur in blood, except for those being present at very low frequencies.

3.3. Extending the Lower Limit of Detection

As can be seen in

Figure 1, when tested at 3 x 10

5 PBMC per well, there are still some donors in whom antigen-specific IgG

+ ASC were not detected above the positivity threshold (>5 SFU per 3 x 10

5 PBMC). Such an outcome may reflect two fundamentally different scenarios: either such donors have not been exposed to the antigen (true negative) or the frequency of B

mem specific for the antigen in question was below the detection limit of the assay as performed for this particular donor (false negative). Owing to the heterogeneous and often unverifiable antigen exposure histories of human subjects, determining the distinction between a true negative

vs. a false negative test result is not a simple task. SARS-CoV-2 S- and NCAP antigens provide here a rare opportunity to distinguish between immunologically naïve and antigen-exposed individuals. As shown in

Supplemental Table S3, subjects whose PBMC were cryopreserved before the introduction of the SARS-CoV-2 virus into the human population exhibited negligible IgG

+ ASC reactivity when 1 x 10

5 or 2 x 10

5 PBMC were tested against SARS-CoV-2 S-antigen or NCAP, respectively. Such samples serve as true negatives and yielded the expected results. In contrast, donors who had either recovered from verified SARS-CoV-2 infection or completed the primary COVID-19 mRNA vaccination series possessed clearly elevated frequencies of S-antigen reactive B

mem-derived IgG

+ ASC and provided 100% diagnostic specificity when tested at 1 x 10

5 PBMC or lower inputs per well. However, these positive test results were seen using samples isolated within half a year following verified infection or vaccination and raised the question whether testing 2 x 10

5 PBMC would suffice for reliably detecting S-antigen or NCAP-specific B

mem in samples from subjects whose prior infection and/or vaccination history was unknown.

With this specific question in mind, cryopreserved PBMC (collected between May and October 2022) were subjected to polyclonal stimulation and evaluated for B

mem-derived IgG

+ ASC reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 S-antigen and NCAP representing the ancestral Wuhan-Hu-1 strain (

Supplemental Table S4). Owing to the elevated frequency of S-antigen specific B

mem-derived IgG

+ ASC detected in earlier experiments (

Figure 1 and data not shown), these samples were exclusively tested using a singlet serial dilution approach starting at 2 x 10

5 PBMC per well. However, to account for the possibility that NCAP-specific B

mem frequencies could be low, we tested these samples using either a singlet serial dilution approach starting at 2 x 10

5 or by seeding replicate wells with 5 x 10

5 PBMC. Notably, B

mem-derived IgG

+ ASC reactivity against the S-antigen was readily apparent in 100% of these donors (n=10) and supports the notion that S-antigen-specific B

mem were generated as a consequence of prior infection(s) and/or vaccination(s). Half (5/10) of these donors, however, did not exhibit clearly elevated numbers of NCAP-reactive B

mem-derived IgG

+ ASC when tested at an initial starting input of 2 x 10

5 PBMC per well. Had these five donors indeed avoided prior SARS-CoV-2 virus infection despite its widespread early in 2022 [

29], or were the frequencies of NCAP-reactive B

mem in such PBMC samples merely below the detection limit of the assay as performed? Only through modifying the testing procedure and seeding 5 x 10

5 PBMC per well to augment the assay’s detection limit could this question be addressed. Among the donors that yielded <5 NCAP-reactive IgG

+ SFU in wells seeded with 2 x 10

5 PBMC, 4 of 5 donors demonstrated an increased number of NCAP-reactive SFU in wells seeded with 5 x 10

5 PBMC. Nevertheless, the resulting SFU counts were not necessarily increased by 2.5-fold as might be expected. However, when the SFU counts from the four replicate NCAP-coated wells seeded with 5 x 10

5 PBMC were aggregated together, entailing a 10-fold increase in the number of PBMC tested in the assay, it became more evident that 8 of 10 donors had likely been previously infected; albeit such cannot be definitively confirmed. Furthermore, when testing PBMC at high cell inputs, and particularly when aiming to detect very low frequencies of antigen-specific ASC, it is advisable to incorporate an irrelevant antigen into the test to serve as a comparator for “chance” reactivity.

As such, B cell ImmunoSpot assays are capable of detecting individual ASC so long as (a) these cells don’t compete for real estate on the membrane for their respective secretory footprints being captured (as shown above, this is a limitation readily overcome by performing serial dilutions when measuring high frequency ASC populations) and (b) the PBMC do not pile up in layers on the membrane. In the latter case of cell crowding, bystander cells in the lower stratum can be expected to hinder the generation of secretory footprints on the antigen-coated membrane by ASC in the upper strata. From direct visualization of PBMC on the membrane, we already know that cell inputs >1 x 10

6 PBMC per well exceed a single stratum (i.e. a monolayer) when input into a standard 96 well plate [

26]. To experimentally address how many PBMC can be plated per well before cell crowding starts to interfer with detection of ASC at single cell resolution, we admixed polyclonally simulated PBMC (that contained ASC at an optimal “Goldilocks number”, i.e., ~ 50 SFU per well) with increasing numbers of autologous unstimulated PBMC (that do not contain IgG

+ ASC). The results are shown in

Supplemental Figure S6, indicating that PBMC inputs exceeding 5 x 10

5 per well can undermine the ability to discern individual secretory footprints. Therefore, if extending the lower limit of detection is intended, the number of PBMC interrogated can be indefinitely increased by testing additional replicates, each at 5 x 10

5 PBMC per well.

Collectively, the data presented so far suggest that testing of uncharacterized PBMC for antigen-specific ASC should start at 3-5 x 105 PBMC per well, and progress in a 2-fold serial dilution. This approach should permit reliable detection and accurate quantification of ASC populations existing at intermediate to high frequencies. If a donor is in the low/ambiguous frequency range, subsequent retesting at 5 x 105 PBMC per well in replicates will enable extending the limit of detection and of quantification. Such a fail safe strategy requires, however, that additional vials of cryopreserved PBMC are set aside (see below). As an alternative, to accomodate the scenario in which Bmem frequencies in the study cohort could also exist at low frequencies, in the first test one could perform a serial dilution in singlet wells and also set up replicate wells with an input of 5 x 105 PBMC. In such a testing approach, the serial dilution would adequately cover the intermediate to high ASC frequency range, while the replicate wells seeded with the highest cell input would enable low frequency measurements.

3.4. Targeted Cryopreservation of PBMC for Testing (And Re-Testing) in B Cell ImmunoSpot Assays

In previous work we have established protocols according to which PBMC can be cryopreserved without loss of functionality for later testing in B cell ImmunoSpot assays [

14,

20] and we have shown the high reproducibilty of the data (CV<20%) when different aliquots of the same sample are tested on different days, even by different investigators [

15]. Such robust assay performance is essential for the ability to (a) test clinical samples in central laboratories remote from sites where they were collected, and (b) independent of the time point of collection (c) to test PBMC of different donors side-by-side in a single high throughput experiment avoiding inter-assay variations of results; (d) to reproduce results by testing repeatedly aliquots of the same blood draw, and (e) to extend the results of the first screening run if needed or intended, e.g., to lower detection limits, or to perform subsequent B cell cross-reactivity or affinity spectrum analysis by ImmunoSpot [

30,

31]. For the latter two options it is essential to first establish the “Goldilocks PBMC number” that yields ~50 SFU per well for a given antigen/sample combination. Cryopreservation is also essential (f) for generating reference PBMC with established B

mem frequencies for antigens of interest [

7], as well as for (g) the ability to validate B cell ImmunoSpot assays [

15].

Cryopreservation of PBMC for testing in functional assays is already well-established and is traditionally done at 10 million PBMC/vial. The data shown above, however, suggest that only 1-2 x 106 PBMC following the 5-day polyclonal stimulation would be sufficient to establish the frequency of Bmem specific for an antigen even when the assessment extends to all four Ig classes and four IgG subclasses. Even if the PBMC would need to be retested, e.g., to extend the lower detection limit, only a few million more cells at most (far less than 10 million) would be needed. The question therefore arose, whether PBMC can be cryopreserved in lower numbers per cryovial than 10 million to avoid the waste of precious cell material.

To address this question, PBMC collected by leukapheresis were either directly subjected to polyclonal stimulation immediately upon receipt, without cryopreservation, i.e., were tested “fresh”, or following cryopreservation in aliquots containing 10, 5, or 2 x 10

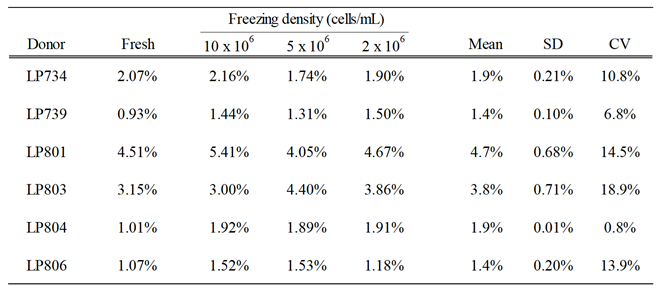

6 PBMC per vial. To allow for batch testing of multiple donors’ samples in parallel, cryopreserved aliquots were thawed two weeks or more after being generated, subjected to polyclonal stimulation and then tested for ASC activity in ImmunoSpot assays. Pan Ig and antigen-specific ASC frequencies were established using the singlet two-fold serial dilution strategy described above. In

Table 1, the frequencies of S-antigen-specific IgG

+ ASC are represented as the percentage of all IgG

+ ASC. The results are essentially identical for fresh and frozen cells, and notably, irrespective of the number of PBMC cryopreserved per vial. Collectively, these data indicate, at least for healthy adult donors, that cryopreserving a custom number of PBMC is feasible. However, whether this conclusion can be extended to donors with different disease states or those undergoing various therapies would need to be verified in each specific clinical scenario.

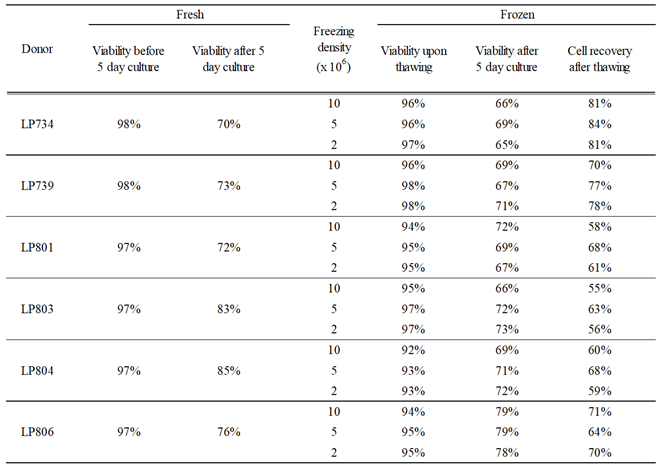

The above experiment also provided insights into cell losses associated with the cryopreservation of PBMC obtained from healthy adult donors at various cell densities. As seen in

Table 2, the viabilities of PBMC frozen at the various cell densities upon thawing and following the polyclonal stimulation were indistinguishable and mirrored what was observed using freshly isolated cell material. Data accumulated over the years documenting cell recovery following the in vitro polyclonal stimulation procedure when starting with samples cryopreserved at 10 million PBMC per vial confirm the conclusion that with rare exceptions at least 50% of the PBMC can be recovered after cryopreservation followed by a 5-day polyclonal stimulation culture (

Supplementary Figure S6B). This finding may serve as a guide for the planning B cell immunoSpot assays cryopreserving custom numbers of PBMC for optimized cell utilization.

4. Summary and Conclusions

As the amount of blood/PBMC available is one of the primary limitations for conducting cell-based immune monitoring, we focused in this publication on the logistic of how to optimize PBMC utilization for detection of antigen-specific Bmem cells using ImmunoSpot assays. We have established that while testing PBMC in serial dilution is necessary for defining the frequency of antigen-specific ASC when they are abundant, doing so in singlet wells provides in most cases results that are just as accurate as tests performed with additional technical replicates. We have also established that four-color multiplexed Ig class- or subclass determinations are an additional means for maximizing PBMC utilization without compromising on assay sensitivity. When testing healthy donors for Bmem specific for antigens representing ubiqitous and commonly encountered viruses, we conclude that an initial screening approach that starts at 3-5 x 105 PBMC per well, with subsequent serial dilutions, will accommodate the majority of cases where Bmem frequencies are in the intermediate to high range. This can readily be accomplished using 0.6 – 1 x 106 PBMC per donor following the 5 days of polyclonal stimulation; which is obtainable from 2 mL, or more conservatively 3 mL, of blood even following cryopreservation. If, for some donors, Bmem frequencies are below the assay’s lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) when tested using the proposed approach (i.e., <10 SFU per 3-5 x 105 PBMC), yet it is desired to augment the LLOQ, thawing additional aliquots and retesting the sample(s) at 5 x 105 PBMC per well in replicate wells is a viable strategy. The calculatable need for cells, and the predictable recovery of PBMC following their cryopreservation and subsequent polyclonal stimulation makes it possible to customize the number of PBMC cryopreserved per vial and achieve optimal sample utilization for downstream testing. Notably, while all findings reported here were made using PBMC obtained from healthy adult donors, our findings should catalyze similar studies to be undertaken using patient or pediatric samples (where PBMC are particularly limiting), as such information should be taken into consideration for achieving optimal sample utilization in the context of a clinical trial.