Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Quantum Statistical Model

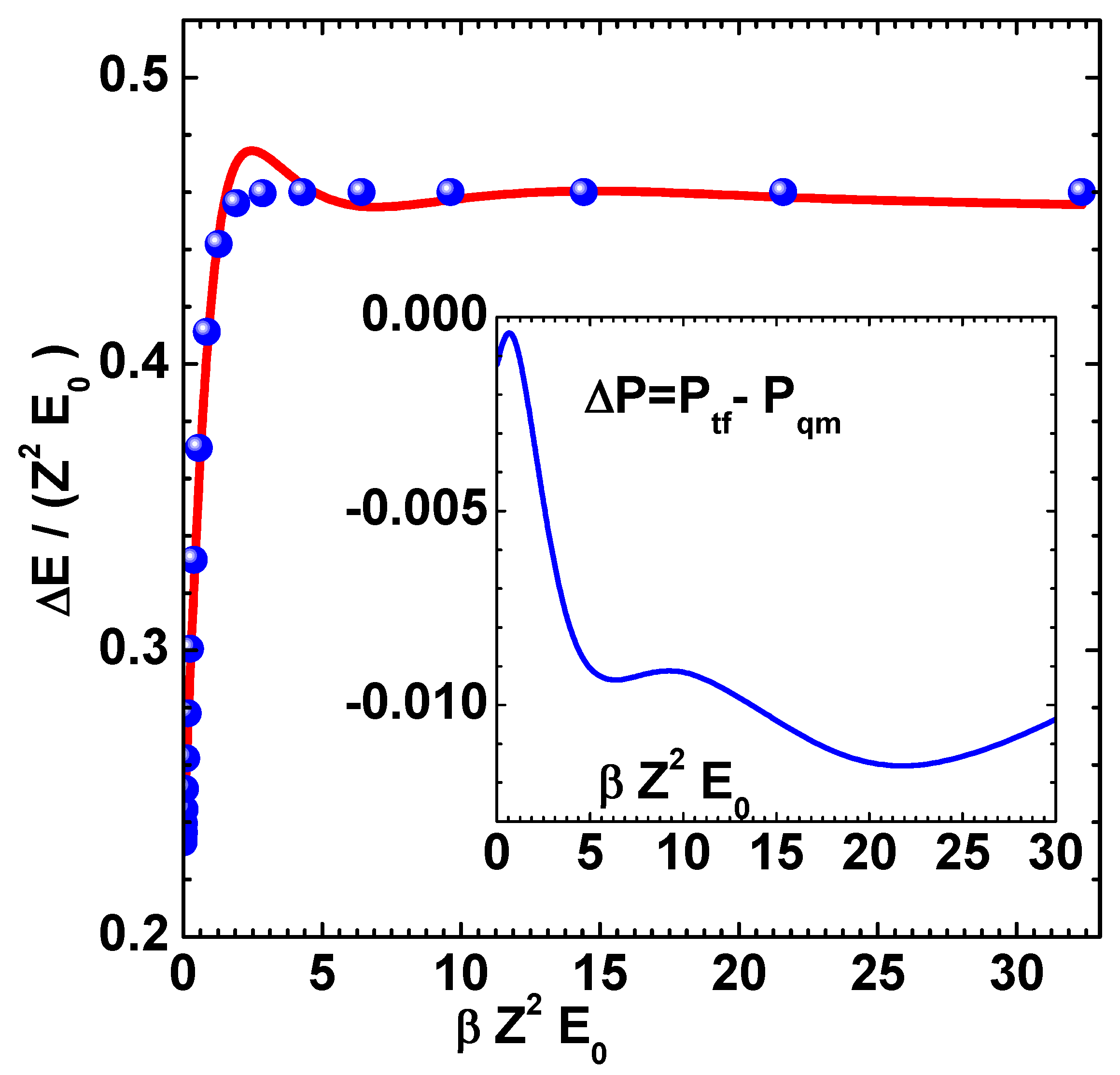

3. Englert-Schwinger Functional

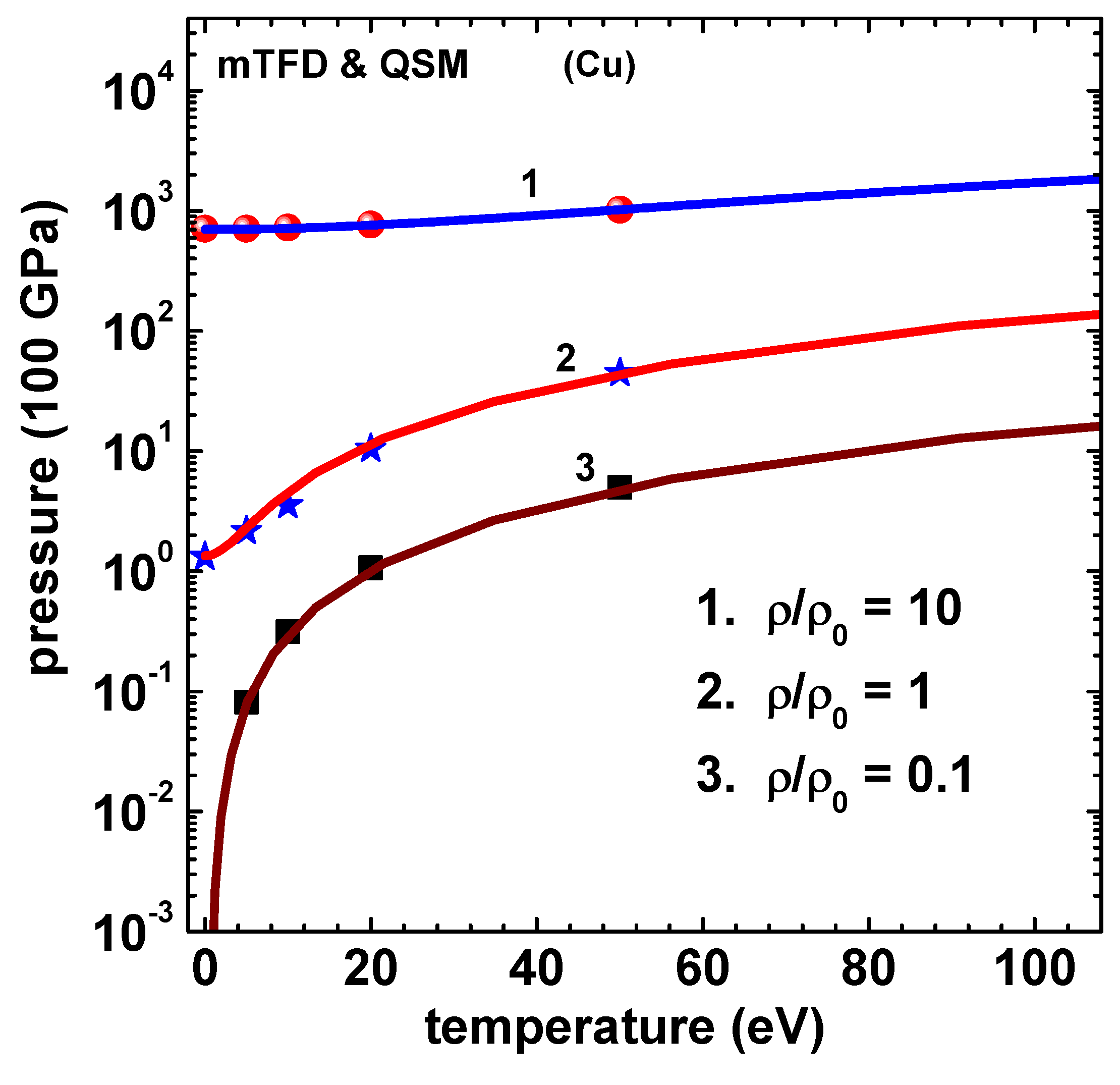

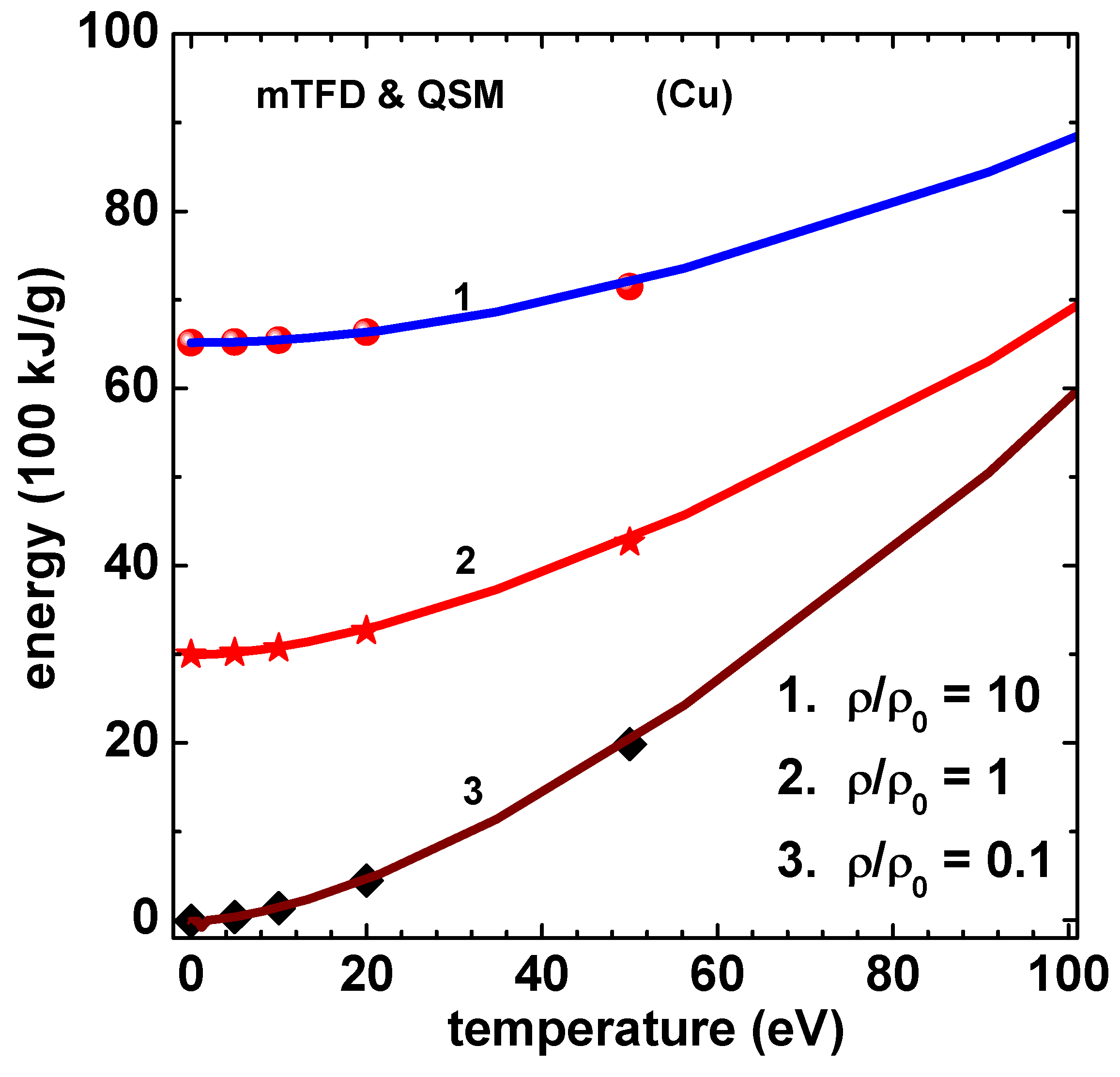

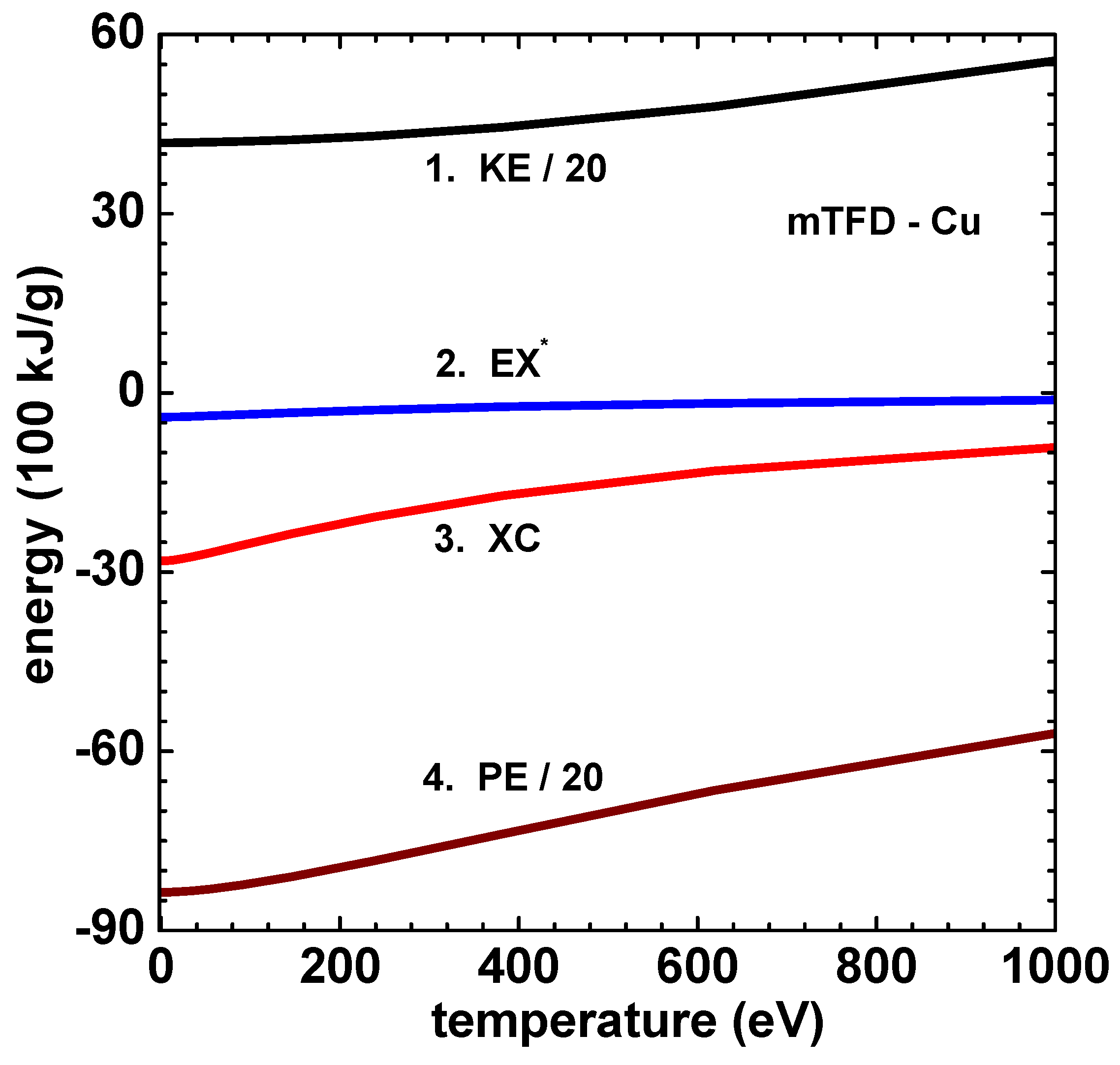

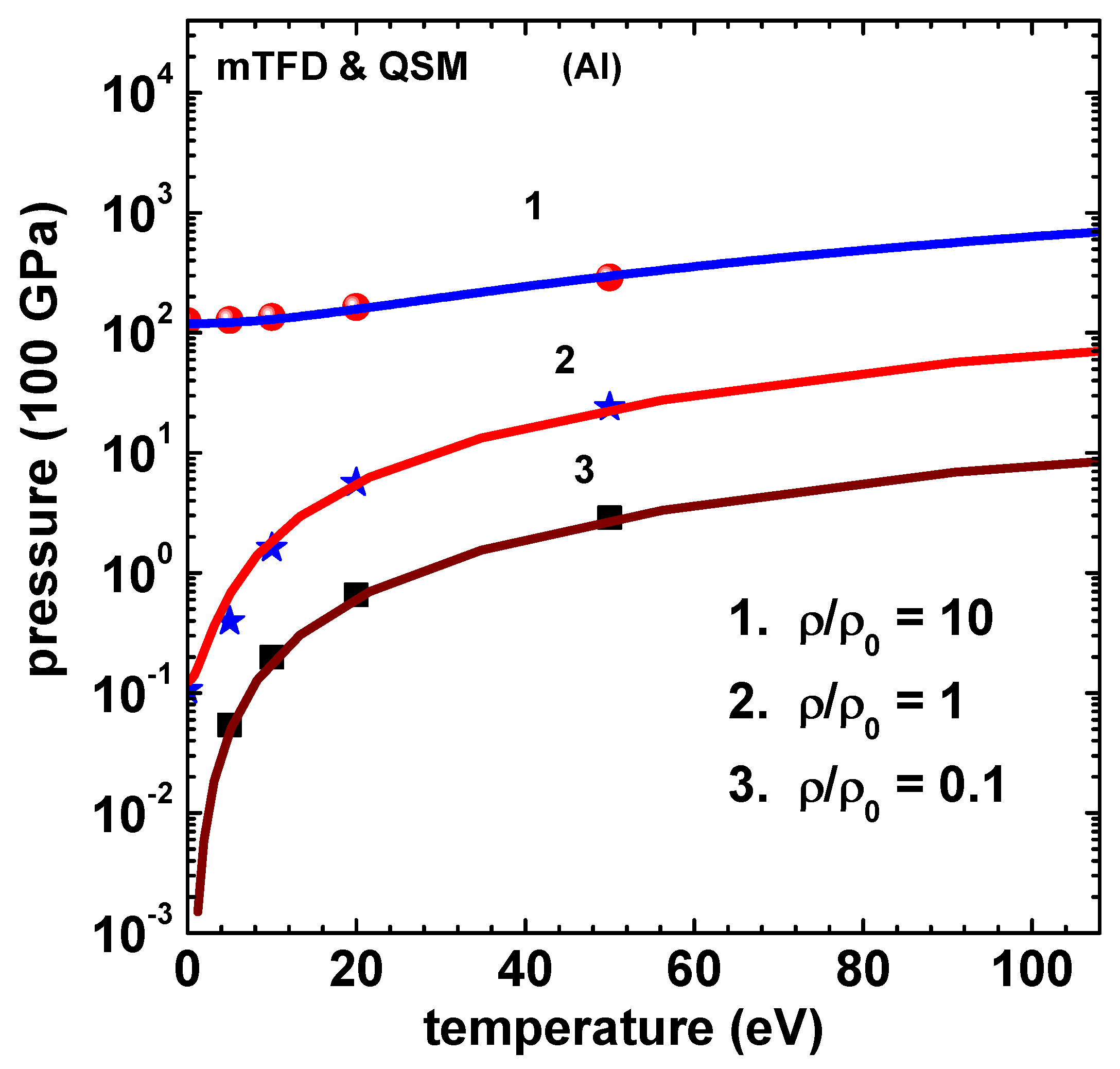

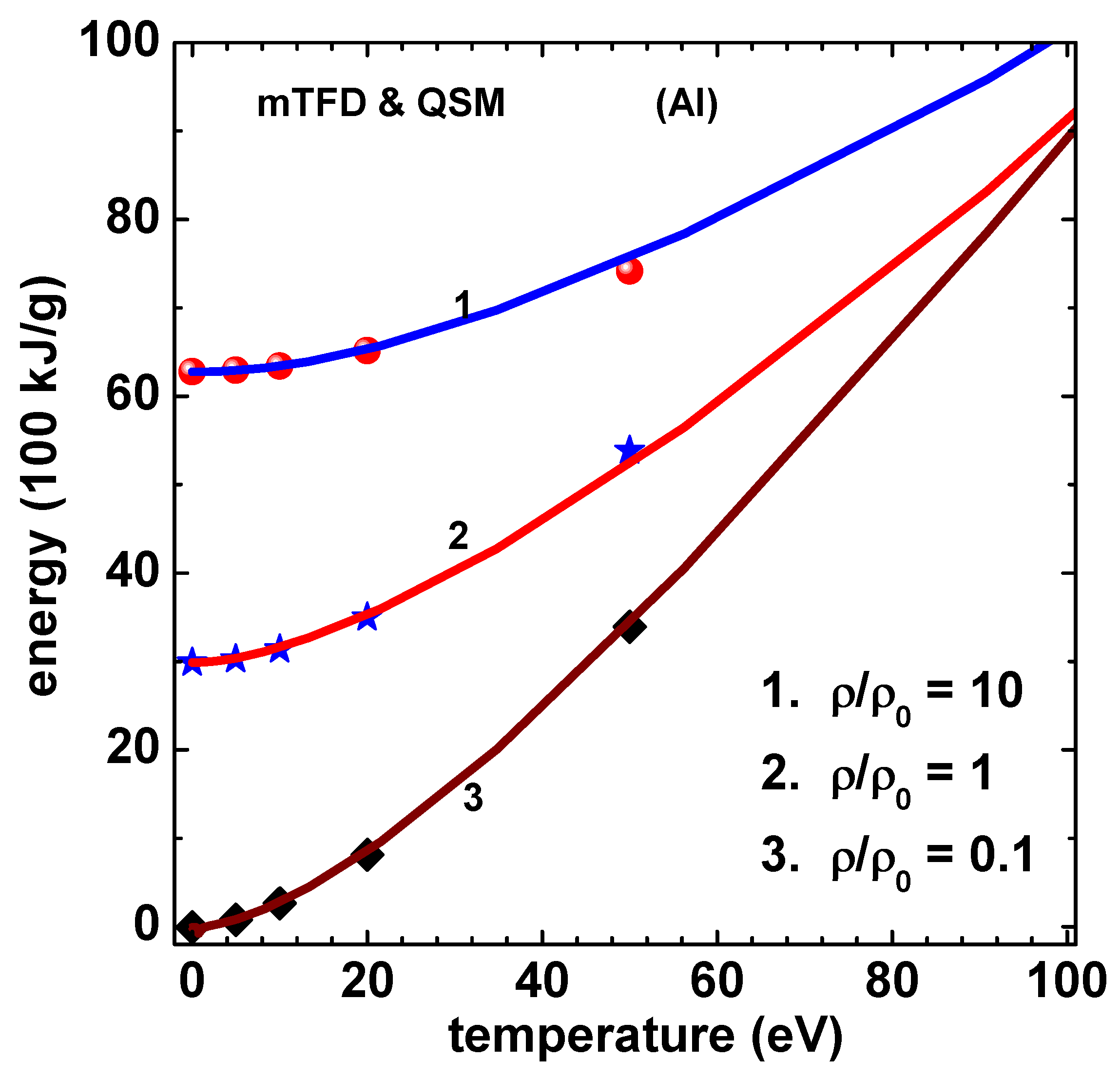

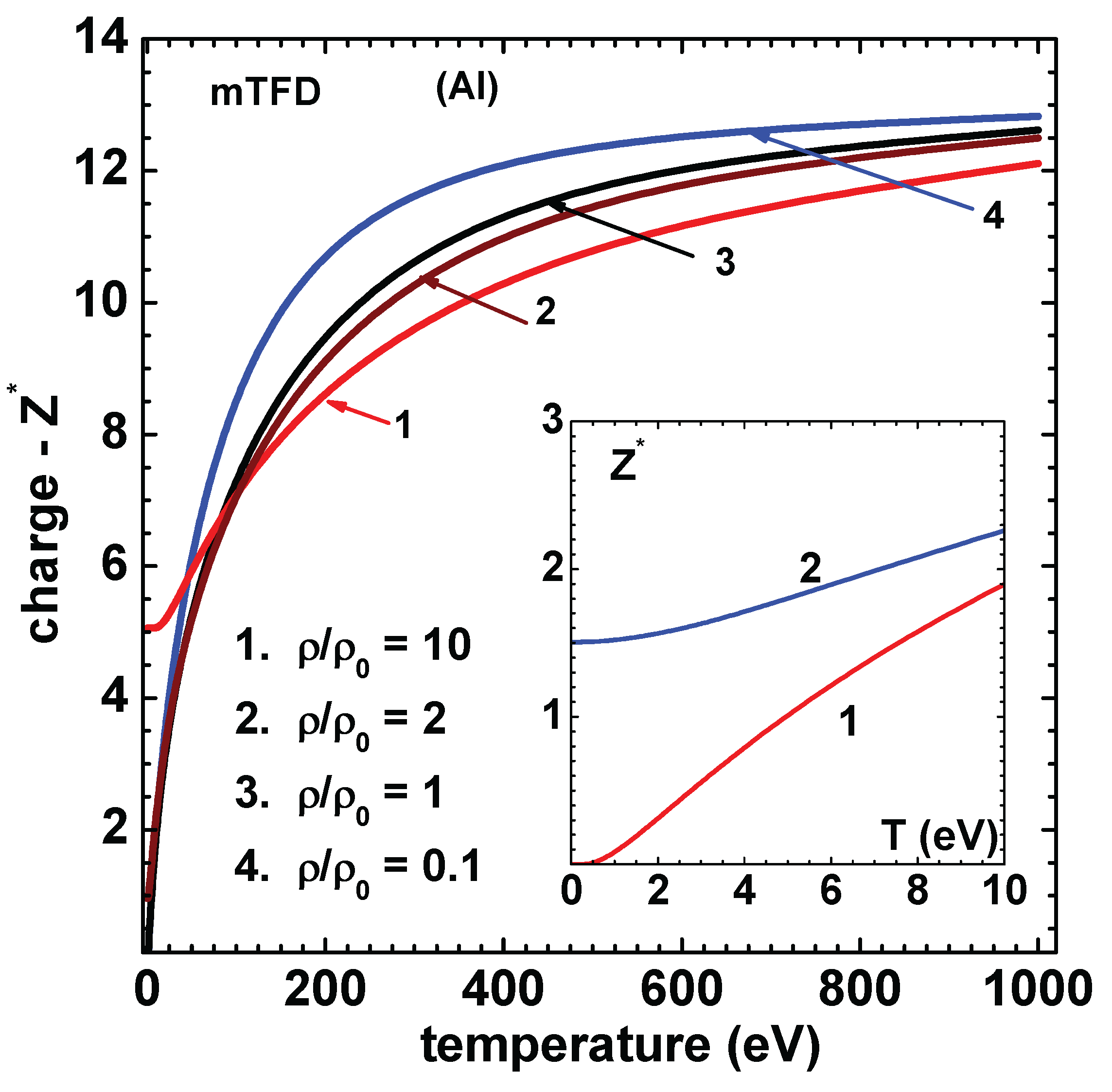

4. Thermodynamic Functions

5. Numerical Scheme

6. Numerical Results

7. Summary

8. Appendix

8.1. Kinetic Free Energy

8.2. Gradient Energy Density

8.2.1. Bloch Density

8.2.2. Corrected Density

8.2.3. Corrected Free Energy Density

8.2.4. QSM-Free Energy Density

8.3. Exchange Free-Energy

8.4. Exchange-Correlation Free-Energy

8.5. Stationary Property of Free Energy

8.6. Strongly Bound Electrons

8.7. Solution via Nyström’s Method

References

- Nikiforov, A. F. ; Novikov, V. G. ; Uvarov, V. B. Quantum-statistical models of hot dense matter: Methods for computation of opacity and equation of state. In Progress in Mathematical Physics, volume 37, Eds: De Monvel, A.B. ; Kaiser, G. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland, 2005.

- R.P. Feynman, N. Metropolis and E. Teller. Equation of state of elements based on the generalized Fermi-Thomas theory. Phys. Rev. 1949, 75, 1561. [CrossRef]

- Latter, R. Thermal behavior of Thomas-Fermi statistical model of atoms. Phys. Rev. 1955, 99, 1854.

- Shemyakin, O. P. ; Levashov, P. R. ; Obruchkova, L. R. ; Khishchenko, K. V. Thermal contribution to thermodynamic functions in the Thomas-Fermi model. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2010, 43, 335003. [CrossRef]

- Pert, G. J. Approximations for the rapid evaluation of the Thomas-Fermi equation. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1999, 32, 272. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, R.D; Ashkin, J. Extension of the Thomas-Felllli-Dirac Statistical Theory of the Atom to Finite Temperatures. Phys. Rev. 1957, 105, 144. [CrossRef]

- Kalitkin, N. N. ; Kuz’mina, L. V. Curves of cold compression at high pressures. Sov. Phys. Solid State 1972, 13, 1938.

- Perrot, F. Zero-temperature equation of state of metals in the statistical model with density gradient correction. Physica 1979, A 98, 555. [CrossRef]

- More, R. M. Quantum-statistical model for high-density matter. Phys. Rev. 1979, A 19, 1234. [CrossRef]

- Perrot, F. Gradient correction to the statistical electronic free energy at nonzero temperatures: Application to equation-of-state calculations. Phys. Rev. 1979, A 20, 586. [CrossRef]

- Fromy, P; Deutsch, C and Maynard, G. Thomas-Fermi-like and average atom models for hot dense and hot matter. Physics Plasmas 1996, 3, 714. [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J. Thomas-Fermi model: The leading correction Phys. Rev. 1980, A 22, 1827.

- Schwinger, J. Thomas-Fermi model: The Second correction Phys. Rev. 1981, A 24, 2353.

- Englert, B. G and Schwinger, J. Thomas-Fermi revisited: The outer regions of the atom Phys. Rev. 1982, A 26, 2622. [CrossRef]

- Venkat Ramana, A. S. and Menon, S. V. G. Application of the Englert–Schwinger model to the equation of state and the fullerene molecule Physica 2011, A 390, 1575. [CrossRef]

- Menon, S. V. G. Analytical Representations of Thermodynamic Functions of Thomas-Fermi Model, Phys of Plasmas 32, (10), 5.0293395, DOI: 10.1063/5.0293395. [CrossRef]

- Antia, H. M. Rational function approximations for Fermi-Dirac integrals. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Series 1993, 84, 101. [CrossRef]

- Mermin, N. D. Thermal Properties of the Inhomogeneous Electron Gas . Phys. Rev. 1965, 137, A 1441. [CrossRef]

- Goth, S; Dornheim, T; Sjostrom, T; Malone, F. D; Foulkes, W. M. C; Bonitz, M. Ab initio Exchane-Correlation free energy of uniform electron gas at warm dense matter conditions. [CrossRef]

- Perrot, F; Darmma-wardana, M. W. C. Spin-polarized electron liquid at arbitrary temperatures: Exchane-Correlation energies, electron-distribution functions, and the state response functions. Phys. Rev. 2000-II, B 62, 16536. [CrossRef]

- Faussurier, G Exchane-Correlation potential at finite temperature. Phys. Plasmas 2025, 32, 072713.

- Szichman, H. Eliezer, S. and Salzmann, D. Calculation of the Moments of the Charge state distribution in hot and dense plasmas using the Thomas-Fermi models J. Quant. Spec. Rad. Trans. 1987, 38, 281. [CrossRef]

- Karasiev, V. V. Chakraborty, D. Trickey, S. B. Improved analytical representation of combinations of Fermi–Dirac integrals for finite-temperature density functional calculations Comp.Phys.Comm. 2015, 192, 114.

- Goano, M. Computation of complete and incomplete Fermi–Dirac integral ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 19955, 21, 221.

- K. E. Atkinson, The numerical solution of integral equations on the second kind Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J. F. and Cowan, R. D. Atomic Binding Energies from a Modified Thomas-Fermi-Dirac Theory Phys. Rev. 1963, 132, 236. [CrossRef]

- March, N. H. and Plaskett, J. S. The Relation between the Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin and the Thomas-Fermi Approximations Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 1956, A 235, 419. [CrossRef]

- Bartel, J. Brack, M. and Durand, M. Extended Thomas-Fermi Ttheory at finite temperature. Nuclear Physics bf 1985 A 445, 263. [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbeck, G. E. Beth, E. The quantum theory of the non-ideal gas I - Deviations from classical theory. Physica 1936, 3, 729. [CrossRef]

- Landau, L. D. and Lifshitz, E. M. Statistical Physics. In Course of Theoretical Physics, Volume 5, 3rd Edition, Part 1( Revised and Enlarged by Lifshitz, E. M and Pitaevskii, L. P. Translated by Sykes, J. B. and Kerarsley, M. J.) Pergamon Press, Oxford, New York, Beijing 1989.

- Horovitz, B. Thieberger, R. Exchange integral and specific heat of electron gas. Physica 1974, 71, 99. [CrossRef]

- Ichimaru, S; Iyetomi, H; Tanaka, S. Statistical physics of dense plasmas: Thermodynamics, transport coefficients and dynamic correlations. Phys. Rep. 1987, 149, 91. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).