1. Introduction

Enteroviruses (EVs), transmitted via various routes, account for approximately 60% of all human infections worldwide [

1]. They are a major cause of childhood infections, spreading not only through direct contact but also through indirect contact with contaminated objects [

2]. EVs are prevalent mainly in temperate regions during the summer and early autumn. Although most infections are asymptomatic, EVs can cause neurological disorders and other illnesses. These viruses can survive indoors for several days, posing a transmission risk from asymptomatic individuals [

3,

4,

5].

EV D68 was first identified in 1962 and was rarely reported until the 2014 outbreak in the United States, which continued until early 2015. This virus primarily affects children and can cause a wide range of respiratory symptoms, ranging from mild illness to severe respiratory distress [

6].

Keswick et al. [

7] suggested that asymptomatic viral shedding via infected individuals in daycare centers can serve as a source of infection for uninfected children and their families. Some EVs can survive on surface vectors for extended periods, acting as secondary sources of infection. Hand washing, strict hygiene management, and proper disinfection measures have been emphasized in high-risk environments, such as daycare centers, hospitals, and restaurants [

8].

EVs are non-enveloped viruses that can persist on surface vectors for weeks to months [

9]. Studies have shown that echoviruses, coxsackieviruses, and polioviruses can remain infectious for 2–12 d or longer on painted wood, glass, and fabric surfaces [

10]. Existing research indicates that viral surface persistence plays a crucial role in the spread of infection [

1], highlighting the importance of understanding environmental transmission routes [

11]. Epidemiological studies have confirmed that contaminated surfaces are potential vectors for disease transmission [

9].

Pappas et al. [

12] detected rhinovirus and EV RNA in approximately 20% of objects in pediatric waiting rooms, suggesting that these objects can act as transmission vectors. Additionally, EVs can survive on nonporous surfaces (e.g., countertops) for at least 45 d; even small amounts of the virus can cause infections [

9]. Many viral infections in healthy adults are asymptomatic or clinically inconspicuous, which complicates transmission control. Surface vectors, including both porous and nonporous surfaces that harbor pathogens, play a critical role in the spread of infections [

9].

The droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) method allows for accurate detection and quantification of low target substance concentrations in environmental samples by separating the sample into tens of thousands of tiny droplets and performing independent PCR reactions in each droplet. Moreover, as ddPCR reactions occur in isolated droplets, they are less affected by various inhibitory substances, such as soil, organic matter, and chemicals, in environmental samples compared to real-time PCR. Therefore, ddPCR is highly reliable for the analysis of environmental samples [

13].

In this study, we aimed to investigate EVs in daycare center environments using highly sensitive ddPCR and examine the effectiveness of environmental cleaning and disinfection in blocking viral transmission. We evaluated hygiene management by confirming EV presence on frequently touched surfaces in daycare centers.

2. Materials and Methods

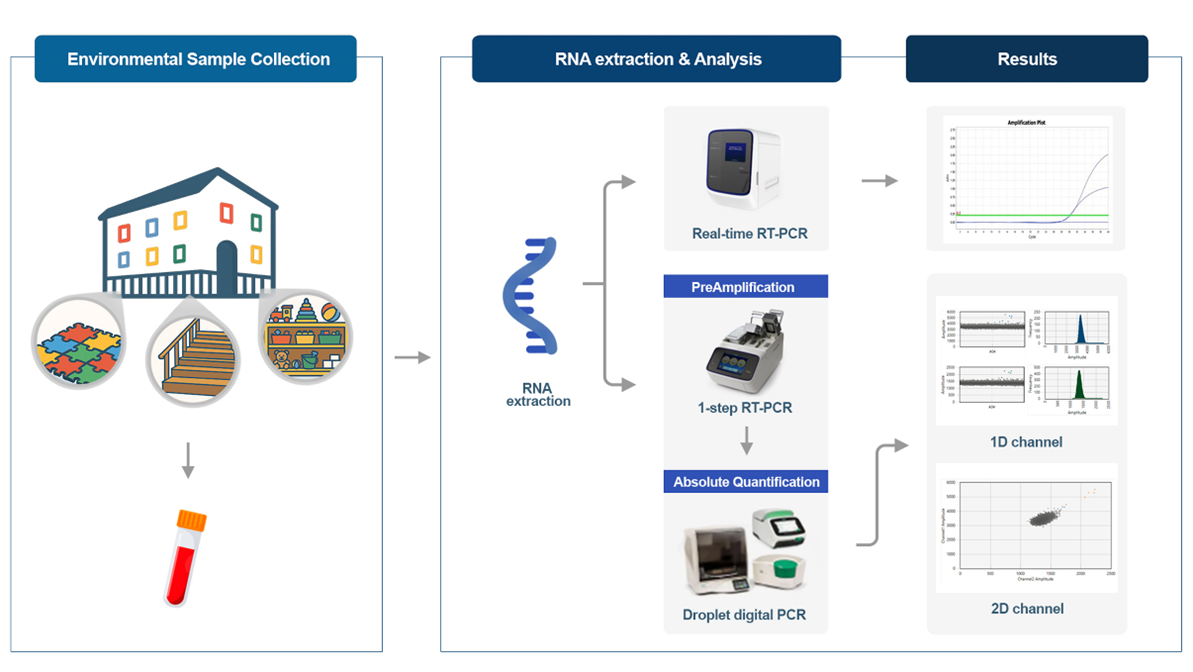

2.1. Environmental Sample Collection

From April to July 2024, 300 environmental samples were collected at two-week intervals over seven sampling events from a daycare center in Sejong. Samples were collected and placed into a viral transport medium (ASAN Pharmaceutical, Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Samples were collected from approximately 10 classrooms, playrooms, reading rooms, hallways, dining rooms, stairs, and elevators frequently used by children aged 0–5 years. The surfaces of objects and places frequently touched by infants and young children, such as toys, books, desks, chairs, and mats, were swabbed over a 10 × 10 cm area using a single swab [

14]. Up to four swabs were used for large surfaces, such as floors. The number of samples collected from each target was as follows: 82 from floors, 52 from toys, 36 from desks, 28 from mats, 16 from shelves, 10 from teaching aids, 8 from books/bookcases, 14 from chairs, and 54 from other sources such as carts and handles.

2.2. RNA Extraction, Real-Time RT-PCR, and ddPCR Analysis

RNA was extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini QIAcube Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and QIAcube Connect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To detect EVs in the environment, the 7500 Fast Real-Time RT-PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and droplet digital PCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) instruments were used. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using a human EV/EV71 multiplex real-time PCR kit (Kogenbiotech, Seoul, Republic of Korea), which is a widely used method for EV detection.

Compared to real-time RT-PCR, ddPCR was employed because it is more sensitive for quantitatively detecting EVs at low concentrations in the environment; a two-step assay was conducted. In the first step, pre-amplification was performed using the PreAmplification pool (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and TaqPath 1-step Master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the ProFlex PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). In the second step, the initial PCR products were further amplified and quantitatively analyzed using a Custom Multiplex assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and 2x ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

The PreAmplification pool and Customs Multiplex assay used for analysis included Pan Enterovirus (Pan EV) and Enterovirus D68 (EV D68); a custom control (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used as a positive control for gating in ddPCR.

2.3. Real-Time RT-PCR and Droplet Digital PCR Conditions

Real-time RT-PCR was performed using a standardized protocol provided by the Human EV/EV71 Multiplex Real-Time PCR Kit (Kogenbiotech, Seoul, Republic of Korea). For ddPCR, custom conditions were set to simultaneously detect Pan EV and EV D68. For quantitative analysis, the first PCR reaction was prepared with a total reaction volume of 10 μL using 2.5 μL of the PreAmplification Pool, 2.5 μL of TaqPath 1-Step Master Mix, and 5 μL of extracted RNA. The amplification was performed under the conditions listed in

Table 1. After amplification, the DNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and diluted to approximately 330 ng.

For the second amplification, a mixture was prepared with 11 μL of 2× ddPCR Supermix for Probes (No dUTP), 2 μL of Custom Multiplex Assay (900 nM), χ μL of the first PCR product, and DW (1-χ) μL to achieve a final volume of 22 μL. The second amplification step was performed under the conditions listed in

Table 2.

3. Results

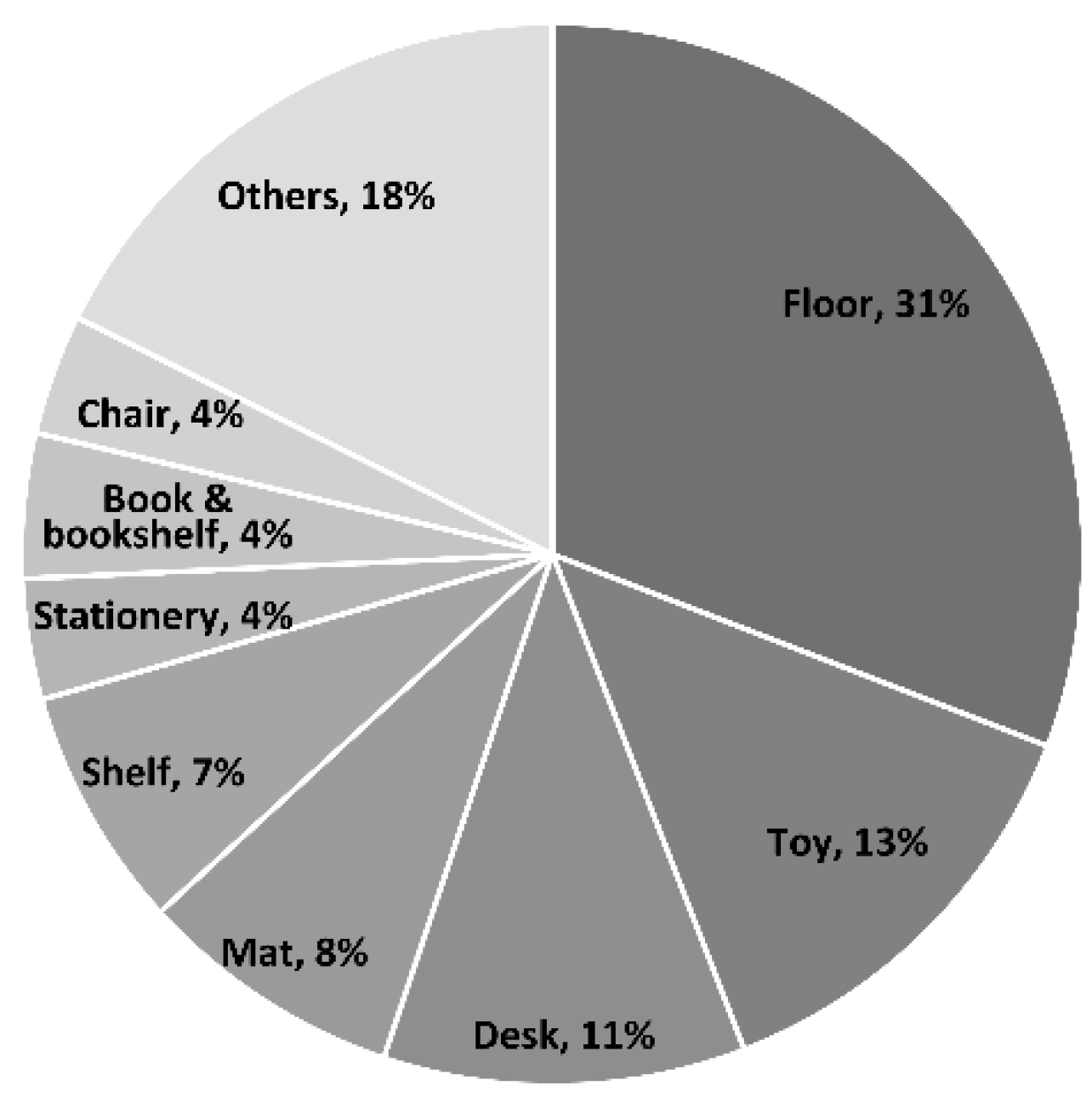

Of the 300 environmental samples, 136 tested positive for EVs by Real-time RT-PCR or ddPCR. Among these, 45 samples tested positive for EV by human EV/EV71 multiplex real-time PCR (Ct 27.50–36.98). EV71 was not detected in any of the samples. Quantitative ddPCR analysis identified 88 samples with Pan EV (range: 1.12–505 copies/20 µL) and 104 samples with EV D68 (range: 1.12–309 copies/20 µL). Among these, 25 samples showed overlapping detection. There was no correlation between the Ct values from Real-time RT-PCR and the concentrations measured using ddPCR. The detected viruses were most frequently found on floors (42 samples, 31%), followed by toys (18 samples, 13%) and desks (15 samples, 11%) (

Figure 1).

One study reported that infectious EVs persisted on all tested surfaces, with the longest survival occurring at 4 °C. There was no significant difference in viral stability between porous and nonporous toys. Smooth, nonporous surfaces have also been found to be more supportive of viral stability [

15]. Similarly, in our study, desks, shelves, bookcases, and chairs were made of wood, but desks had a smooth surface because they were covered with vinyl acetate, which may have influenced viral stability. Consequently, a relatively higher virus detection rate may have been observed on desks. Additionally, floors composed of harder and smoother materials than mats likely provided favorable conditions for virus survival, resulting in higher detection rates. In contrast, EVs on toys were primarily detected on non-rigid materials, such as cloth and wooden blocks, rather than on plastic. Other samples included infant carts, carts, stairs and door handles, elevator interiors, elevator buttons, food trays, and forks, with handles, elevator interiors, and cart interiors showing the highest detection rates.

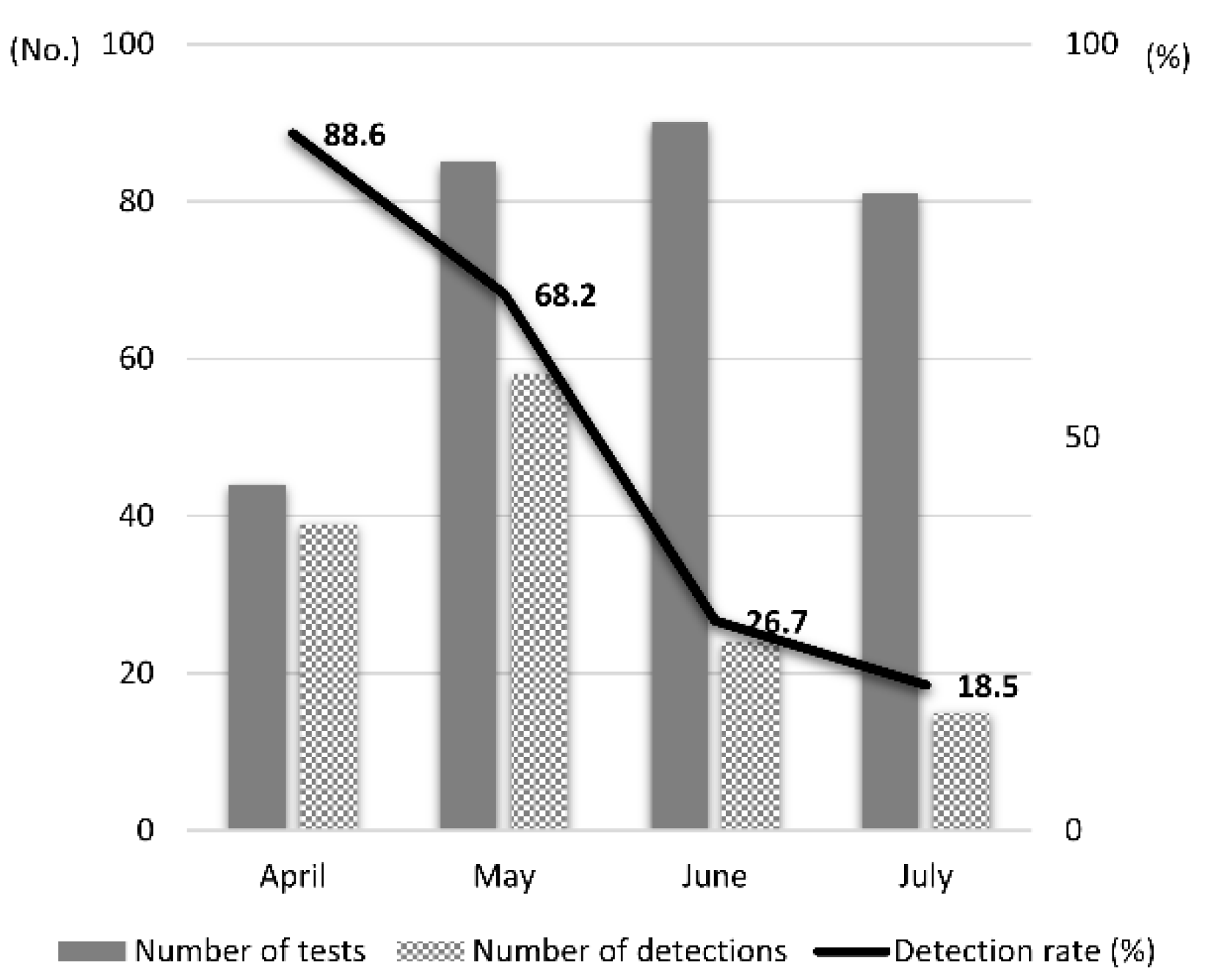

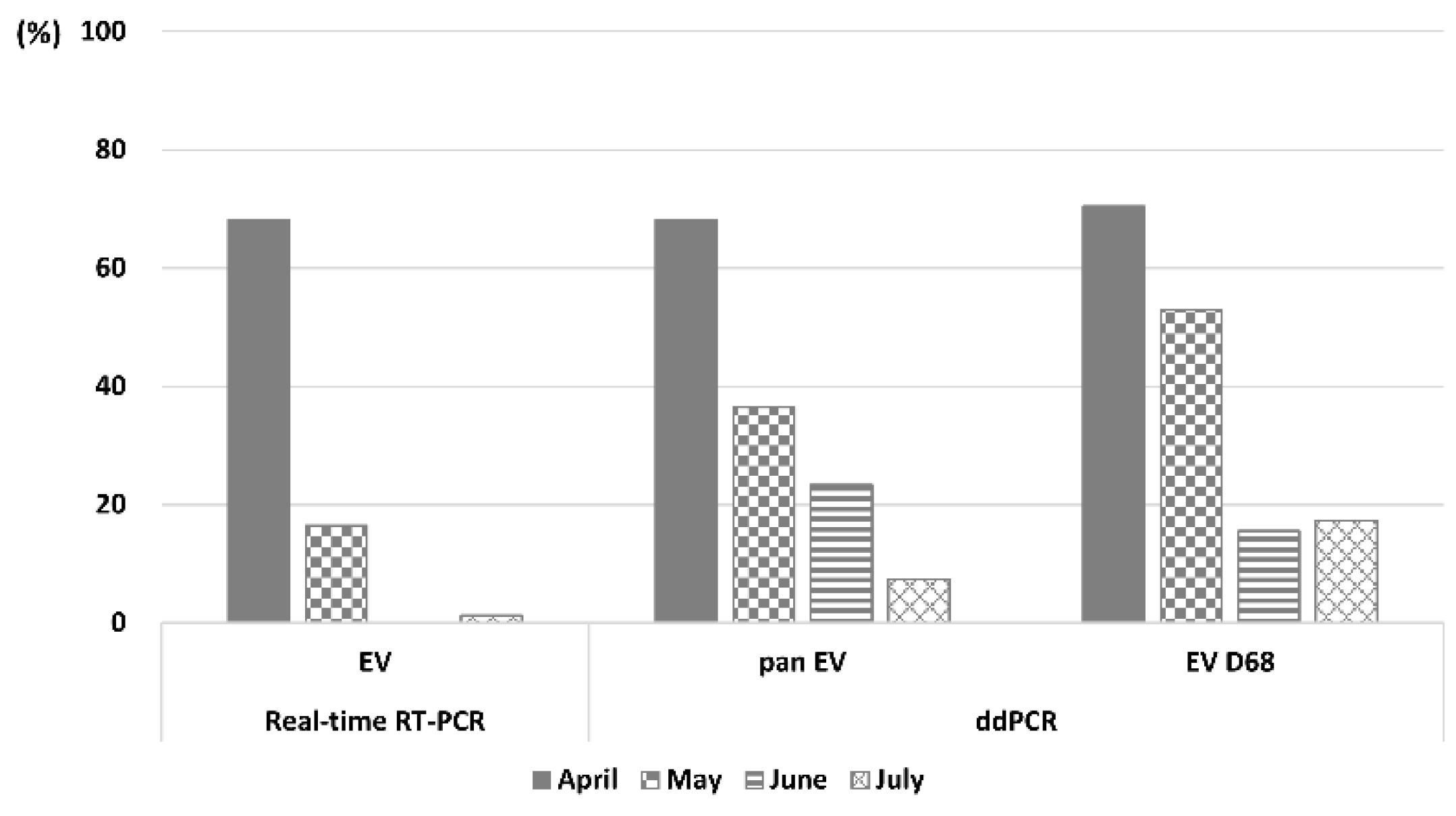

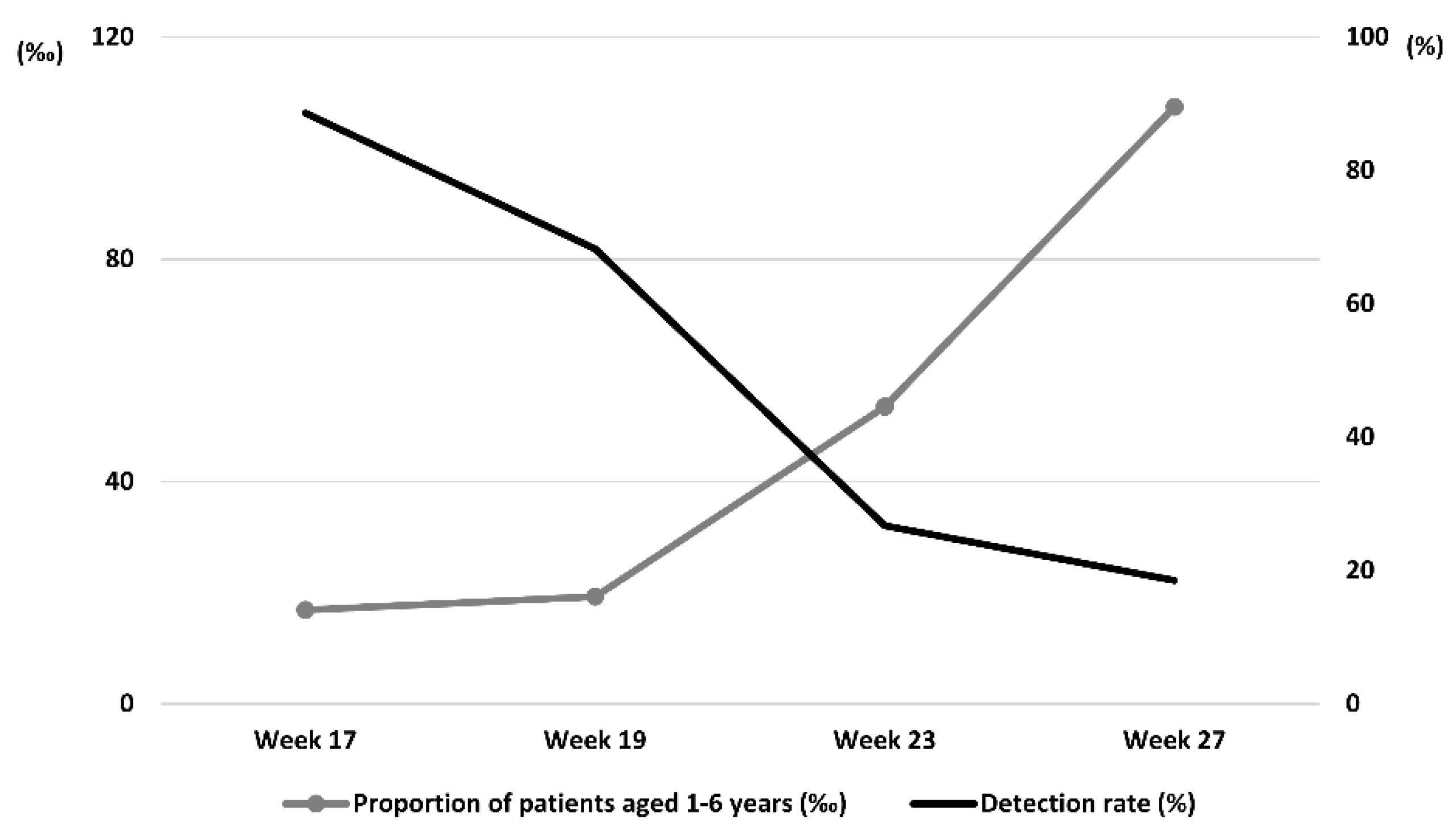

The highest detection rates were observed on the floor, followed by toys and desks. The monthly EV detection rates showed a gradually decreasing trend: 88.6% in April, 68.2% in May, 26.7% in June, and 18.5% in July (

Figure 2). Real-time RT-PCR and ddPCR showed similar monthly detection rates (

Figure 3). This trend contrasts with the nationwide increase in patient numbers, suggesting that enhanced hygiene and safety measures, including indoor environmental cleaning and disinfection, may have contributed to the decrease in virus detection (

Figure 4). National patient proportion data were obtained from the Republic of Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) Infectious Disease Web Portal [“

https://npt.kdca.go.kr/pot/is/st/hfmd.do (accessed on February 19, 2025)].

In the survey conducted in April (week 17), environmental samples were collected from stair handrails and floors. Two weeks later, upon retesting the same samples from week 19, neither EV nor pan EV was detected. Additionally, EV D68 was either not detected or showed a decrease in copy number (

Table 3). These results suggest that virus monitoring can raise awareness of the importance of hygiene management and that disinfection and cleaning can effectively block viral transmission in the environment.

Despite the peak outbreaks of hand, foot, and mouth diseases, the EV detection rate showed a decreasing trend. The detection rates of EVs analyzed using Real-time RT-PCR and ddPCR also showed a decreasing trend over time. A comparison of data from weeks 17 to 27 showed that while the nationwide patient proportion increased, the EV detection rate tended to decrease: Patient proportion (‰) = (Number of hand, foot, and mouth disease cases/Total number of patients treated at sample hospitals) * 1,000, where patient count refers to reported cases of hand, foot, and mouth disease with complications.

Comparing the EVs detected by Real-time RT-PCR and pan EV detected by ddPCR, EVs were detected in 45 samples, whereas Pan EV was detected in 88 samples, indicating that ddPCR had approximately twice the detection rate. This suggests that ddPCR is advantageous for detecting trace amounts of viruses in the environment, and can be used as a reliable analytical method for sensitive virus detection in environmental samples [

16].

4. Discussion

EVs can survive on surface vectors for extended periods; factors such as surface type, temperature, and humidity can affect their persistence [

8]. The persistence and stability of viruses are influenced by various factors, including environmental surface materials, temperature, humidity, and the concentration and type of the virus [

15].

Consequently, viral survival on surfaces is affected not only by internal factors, such as the characteristics of the surface and virus, but also by external factors, such as temperature and humidity. Viruses can cause infections, even in small amounts, if they survive on surfaces long enough to come into contact with the host. Several studies have shown that most respiratory and enteric viruses can survive in fomites and hands under certain conditions and can be transferred from fomites to hands. Therefore, disinfecting both the fomites and hands is an important method for blocking viral transmission [

9]. Particularly, as EVs can survive on various surfaces, close contact among children in crowded classrooms and placing contaminated toys or utensils into their mouths pose a high risk of exposure. Other studies have suggested that using appropriate disinfectants and regular disinfection can more rapidly inactivate EVs [

15].

This study had limitations in comparing virus detection rates based on surface type because we did not consider that hard surfaces can play an important role in viral transmission [

17] or that environmental variability, such as high humidity, affects EV survival [

18].

Although some studies suggest a potential discrepancy between viral RNA detection and viral infectivity [

2], analysis using ddPCR is highly useful for accurate and sensitive detection of minute amounts of viruses in environmental samples compared to Real-time RT-PCR, indicating that ddPCR can more accurately measure viral load, making it a crucial tool for environmental surveillance and preventing virus spread. Therefore, ddPCR may play an important role in the prevention and control of infectious diseases in public places and work environments.

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the importance of hygiene habits for maintaining health, preventing disease spread and stresses, and the need to simultaneously promote hand hygiene and environmental disinfection to improve public health [

19,

20]. Hand hygiene and environmental disinfection are crucial for preventing infectious diseases [

19,

20,

21].

The results in

Table 3 demonstrate that disinfection plays a crucial role in blocking viral transmission by showing the differences in virus detection before and after disinfection. Therefore, understanding the possibility of viral survival on environmental surfaces is important to effectively block transmission in daycare centers. Thoroughly disinfecting the fomites frequently encountered by asymptomatic children and strengthening personal hygiene management are essential. This can minimize the spread of infections in public places.

Considering these points comprehensively, a multifaceted approach is needed to manage environmentally mediated viruses, such as EVs. The strict management of environmental surfaces and reinforcement of personal hygiene should be combined, with an emphasis on establishing practical and efficient public health policies and guidelines. Particularly in spaces such as day care centers, where infection-vulnerable individuals, such as infants and young children, primarily live, we must establish an environmental management system.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the presence of EVs in the indoor environment of daycare centers using real-time RT-PCR and ddPCR. EVs were detected in the environment through both methods, with ddPCR identifying more than twice as many positives as real-time RT-PCR. These findings suggest that ddPCR may be more useful for detecting trace amounts of viruses in the environment. Additionally, environmental EVs may contribute to potential viral transmission. After disinfecting the same materials and sampling them again two weeks later, no viruses were detected; periodic ventilation and disinfection over time resulted in a decrease in viral load. These findings suggest that environmental hygiene management can reduce virus transmission. As virus infectivity assays and virus viability under environmental conditions were not considered in this study, future research should examine these aspects in greater detail.

Author Contributions

Kyung-Seon Kim: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis and investigation, Writing-original draft preparation Hye-Jin Jang: Methodology Seo-Youn Koo: Methodology Jeong-Hyun Lee: Writing-review and editing In-Hae Choi: Investigation; Chae-Hyeon Sim: Investigation Ni-Na Yoo: Investigation Jin-Gyun Eom: Conceptualization, Supervision Kyoung-Yong Jung: Supervision Eun-Ok Bang: Supervision: Yoon-Seok Chung: Writing-review and editing

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the daycare center staff for providing the environmental samples and for their active cooperation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vasickova, P.; Pavlik, I.; Verani, M.; Carducci, A. Issues concerning survival of viruses on surfaces. Food Environ. Virol. 2010, 2, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittikul, P.; Sriburin, P.; Rattanamahaphoom, J.; Nuprasert, W.; Thammasonthijarern, N.; Thaipadungpanit, J.; Hattasingh, W.; Kosoltanapiwat, N.; Puthavathana, P.; Chatchen, S. Stability and infectivity of enteroviruses on dry surfaces: Potential for indirect transmission control. Biosaf. Health 2023, 5, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, G.; Fratini, M.; Della Libera, S.; Iaconelli, M.; Muscillo, M. Viral infections acquired indoors through airborne, droplet or contact transmission. Ann. Ist Super. Sanita 2013, 49, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, I.P., Jr.; Giamberardino, H.I.; Raboni, S.M.; Debur, M.C.; de Lourdes Aguiar Oliveira, M.L.A.; Burlandy, F.M.; da Silva, E.E. Simultaneous enterovirus EV-D68 and CVA6 infections causing acute respiratory distress syndrome and hand, foot and mouth disease. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Salort, M.; Oberste, M.S.; Pallansch, M.A.; Abedi, G.R.; Takahashi, S.; Grenfell, B.T.; Grassly, N.C. The seasonality of nonpolio enteroviruses in the United States: Patterns and drivers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 3078–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lednicky, J.A.; Bonny, T.S.; Morris, J.G.; Loeb, J.C. Complete genome sequence of enterovirus D68 detected in classroom air and on environmental surfaces. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, e00579-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keswick, B.H.; Pickering, L.K.; DuPont, H.L.; Woodward, W.E. Survival and detection of rotaviruses on environmental surfaces in day care centers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, F.X.; Pintó, R.M.; Bosch, A. Survival of enteric viruses on environmental fomites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 3704–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, S.A.; Gerba, C.P. Significance of fomites in the spread of respiratory and enteric viral disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1687–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnage, N.L.; Gibson, K.E. Sampling methods for recovery of human enteric viruses from environmental surfaces. J. Virol. Methods 2017, 248, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrakar, S.B.; Henley, J.; Gurian, P.L.; Gerba, C.P.; Mitchell, J.; Enger, K.; Rose, J.B. Persistence analysis of poliovirus on three different types of fomites. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 122, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, D.E.; Hendley, J.O.; Schwartz, R.H. Respiratory viral RNA on toys in pediatric office waiting rooms. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, K.B.; Han, Y.S.; Jeong, R.D. Application of reverse transcription droplet digital PCR for detection and quantification of tomato spotted wilt virus. Res. Plant Dis. 2021, 27, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Park, S.; Cho, K.; Yoo, J.E.; Lee, S.; Ko, G. Comparison of swab sampling methods for norovirus recovery on surfaces. Food Environ. Virol. 2018, 10, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharin, S.N.A.N.; Tan, S.L.; Sam, I.C.; Chan, Y.F. Stability of enteroviruses on toys commonly found in kindergarten. Trop. Biomed. 2023, 40, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, D.; Tafuro, M.; Mancusi, A.; Girardi, S.; Capuano, F.; Proroga, Y.T.R.; Corrado, F.; D’Auria, J.L.; Coppola, A.; Rofrano, G.; et al. Sponge Whirl-Pak sampling method and droplet digital RT-PCR assay for monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces in public and working environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahl, M.C.; Sadler, C. Virus survival on inanimate surfaces. Can. J. Microbiol. 1975, 21, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, A.; Schwebke, I.; Kampf, G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, J.D.; Lee, M.B. Enteric outbreaks in long-term care facilities and recommendations for prevention: A review. Epidemiol. Infect. 2009, 137, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniford, L.J.; Schmidtke, K.A. A systematic review of hand-hygiene and environmental-disinfection interventions in settings with children. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, V.; Biran, A.; Deverell, K.; Hughes, C.; Bellamy, K.; Drasar, B. Hygiene in the home: Relating bugs and behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).