1. Introduction

Enteric viruses pose significant global public health concern due to their association with acute gastric enteritis [

1]. Pathogens such as Human Adenoviruses (HAdV), Noroviruses, group A rotavirus (RVA), Hepatitis A virus (HAV), and Enteroviruses are among these viruses [

2]. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the potential environmental sources of these infections in order to develop efficient intervention strategies. With the current rising need for water globally, treated wastewater ends up either in agriculture fields or in domestic homes after recycling, posing a significant public health risk [

3]. This is essential because of occasional deficiencies of wastewater treatment techniques against viruses [

4]. Therefore, wastewater surveillance is central in identifying potential risk areas associated with wastewater.

As such, viral markers for potential enteric viral pathogens presence are required for any intervention to provide meaningful results [

5]. Since HAdV is widely present and stable in the environment, the virus is currently considered a suitable indicator [

5]. In addition to being a viral indicator, HAdV is still one of the main causes of diarrhoea in both immunocompromised adults and younger populations [

6]. Adenovirus is a double-stranded, non-enveloped DNA virus belonging to the family

Adenovidae and comprises six genera, (

Mastadenovirus,

Aviadenovirus,

Atadenovirus,

Siadenovirus,

Ichtadenovirus, and

Testadenovirus) [

3]. The Mastadenoviruses have been implicated in causing most human infections. Currently seven species have been identified as human pathogens namely; Human mastadenovirus A-G [

3]. Human mastadenovirus A, B, and C are implicated in respiratory infections while Human mastadenovirus F serotypes 40 and 41 cause acute gastroenteritis in children younger than 1 year old [

1]. To date over 110 serotypes have been identified [

1,

3].

Rotavirus is also a common cause of acute gastroenteritis, typically expelled into wastewater by infected individuals [

7]. The virus belongs to the genus

Rotavirus in the family

Sedoreoviridae in the order Reovirales. The genus

Rotavirus is classified into distinct species, Rotavirus A-J, with RVA being the most common cause of human infections. While vaccines for RVA have been developed, reports still highlight low efficacy, particularly in developing countries [

8,

9]. Consequently, the investigation of presence of RVA in wastewater can serve as an indicator of vaccine efficacy [

10]. The presence of RVA may serve as the basis of monitoring the effectiveness of the RVA vaccines through monitoring the level of the virus in wastewater.

Therefore, the presence of HAdV and RVA viral pathogens in wastewater emphasizes the need for a robust surveillance system that would enhance tracking of viral pathogens and providing an opportunity to estimate the prevalence, genetic diversity, and geographic distribution [

11,

12]. Wastewater surveillance can help to detect viruses that are not evident by clinical surveillance [

13]. Surveillance of wastewater also provides an opportunity to detect the spread of infections in different areas where resources for clinical diagnosis and reporting systems are limited or unavailable [

14]. It is also valuable for identifying newly introduced viruses in populations or tracking fluctuations resulting from seasonal or precipitation changes [

11,

15]. For this purpose, wastewater surveillance forms an integral part of the “early warning” system [

16,

17].

In Zambia, diarrhea-associated deaths are ranked third in the young population [

18]. Notably, HAdV and RVA are among the top six enteric pathogens associated with moderate to severe diarrhea in Zambia, although the magnitude of HAdV infection remains unclear [

19]. Thus, wastewater surveillance will aid in monitoring the effectiveness of the current interventions in mitigating the prevalence of enteric pathogens. To our knowledge, no report on the detection of HAdV and RVA in wastewater has been published in Zambia. Our study set out to detect HAdV and RVA in wastewater and provide a proof of principle for the establishment of a robust surveillance system for viral pathogens of public health importance in wastewater in Zambia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in Lusaka in a wastewater network system to detect the presence of HAdV and RVA. The study was conducted at 4 sewerage sites that service selected parts of Lusaka District (

Table 1). The sites included two (2) pump stations (Chelstone and Mass media), one stabilization pond (Kaunda square), and one wastewater treatment plant (Manchinchi).

2.2. Sample Collection

Convenient sampling was employed for the four sites in the study. Collection was carried out every Tuesday between 7 am and 9 am for five (5) consecutive weeks from 25th July 2023 to 22nd August 2023. A grab-composite sample (6L) was constituted over a period of 1 hour and collected at intervals of 5 min. The composite sample was aliquoted into various sample containers and bottles for the 3 concentration methods: (i) bag-mediated filtration system (BMFS), (ii) skimmed milk flocculation, and (iii) polyethylene glycol precipitation. The sample bottles were placed on ice-chilled cool boxes and transported to the University of Zambia, School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Disease Control BSL2 laboratory for processing. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the samples were immediately prepared for concentration.

2.3. Viral Concentration

The wastewater samples were subjected to three (3) viral concentration methods prior to nucleic acid extraction.

2.3.1. Skimmed Milk Flocculation

Composite wastewater sample (500 mL) was used for the direct skimmed milk flocculation method. Briefly, skimmed milk powder (0.5 g) was dissolved in 50 mL of sterile water to obtain 1% (w/v) skimmed milk solution [

20]. The

pH of the solution was carefully adjusted to 3.5 using 1M HCl. Five mL of 1% skimmed milk solution was added to 500 mL of the wastewater composite sample to obtain a final concentration of 0.01% (w/v). Samples were stirred for 8 hours, and flocs were allowed to settle at room temperature for another 8 hours. The supernatant was carefully removed with serological pipettes without agitating the flocs. A final volume of 50 mL containing the flocs was transferred to 50 mL falcon tubes and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was carefully removed, and pellets carefully dislodged. The pellets were resuspended in 2mL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer saline (PBS),

pH 7.5. The final concentrated sample was aliquoted in small working volumes (~200 μL) and stored at -80 °C until viral nucleic acid extraction.

2.3.2. Bag-Mediated Filtration System (BMFS)

Samples were collected into the BMFS bag and processed as described previously [

21]. Briefly, wastewater (6,000 mL) from the composite sample was collected in sampling bags with a pre-screen mesh (249-μm pore size) over the opening. The composite sample was filtered into the collection bag mounted on a custom-made tripod stand (BoundaryTEC, Minneapolis, MN, USA). A ViroCap

TM filter (Scientific Methods, Inc., Granger, IN, USA) was attached to the bag’s outlet port and the sample was allowed to flow through the filter by gravity. The average volume filtered was about 5,400 mL, over an average of 90 min to 3 hours (the time for filtration was dependent on the amount and size of fecal debris in the wastewater. The filter was transported under a cold chain to the University of Zambia for viral elution and secondary concentration with skimmed milk. To elute the virus from the viral cup filter, the beef extract eluate was injected into the filter inlet and incubated for 30 min before recovering the eluate through the filter outlet using a peristaltic pump.

2.3.2.1. Secondary Concentration Procedure

The skimmed milk secondary flocculation procedure was conducted at the laboratory. A total of three (3) mL of 1% w/v skimmed milk was added to the eluate. The pH of the mixture was adjusted to the range of 3.0-4.0 using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl). To coagulate the proteins in flocs, the eluate was incubated at room temperature and shaken evenly for 2 hours. The sample was aliquoted into 50 mL conical tubes and centrifuged at 3,500 x g, 4°C for 30 min. The sample was returned to the biosafety cabinet (BSC) and the supernatant was decanted. The pellets were completely resuspended in 10 mL of sterile PBS, pH 7.4 by vigorous vortexing. The concentrated sample was aliquoted in 1 mL working volumes and stored at -80 °C until use.

2.3.3. Polyethylene Glycol-Based (PEG) Concentration

PEG precipitation was performed as previously described [

22]. Briefly, 14 g of PEG 8000 and 1.17g of NaCl were added to 100 mL of the composite sample. The PEG 8000 and NaCl were completely dissolved by vigorous shaking. The sample was stirred at 200 rpm, 4°C for 4 hours followed by centrifugation at 6,500 x g, at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet re-suspended in 6 mL of sterile PBS (

pH 7.4). The final concentrated sample was aliquoted in small working volumes (~200 μL) and stored at -80°C until use.

2.4. Nucleic Acid Extraction

About 200 µL of the sample was extracted using Qiagen QIAamp® mini RNA or DNA kits (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA). The total nucleic acids were eluted in 60 µL of the elution buffer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To minimize freezing and thawing, each sample was aliquoted into 50 µL volumes and stored at -80°C until use.

2.5. Genomic Screening of Adenovirus and Rotavirus

2.5.1. Detection of Adenovirus and Rotavirus on PCR

HAdV and RVA were detected using a one-step TaqPath qPCR protocol following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 20 µL total volume of each reaction was prepared to consist of the following: 1 µL of primer and probe mix (

Table 2), 15 µL of TaqPath Master Mix, 2 µL of total nucleic acid sample and 2 µL of nuclease free water. The mixture was run under the following conditions: pre-incubation at 25°C for 2 min, followed by reverse transcription incubation at 50°C for 15 min, enzyme activation at 95°C for 2 min, 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C for 3 sec, and 60°C for 30 sec. For HAdV detection, the reverse transcription step was omitted. A sample was considered positive for HAdV and RVA when the cycle threshold value was less than 32.

2.5.2. Conventional PCR and Sequencing of Adenovirus

To detect the presence of human Adenovirus in wastewater, two PCR reactions targeting the hexon gene were performed using the Quick Taq Hs Dye Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) following the manufacturer's instructions using primers in

Table 2. The initial reactions did not include any positive control, as it was not available. The initial PCR targeting the hexon gene was performed with primer pairs Hex1DegFw, and Hex2DegRv yielding 301bp product. The amplicon was identified as HAdV sequence, which was subsequently used as a template for designing primers for the next PCR. The second PCR overlapping the capsid and hexon genes was performed using primer pairs; Adeno Cap17467Fw and Adeno Hex 18185Rv yielding a 718bp amplicon. Both PCRs were performed with conditions: 94°C for 2 min, 94°C for 30 sec, 54°C for 30 sec, 68°C for 1 min, and final extension at 68°C for 5 min. The PCR products for the first and second PCRs were observed on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

The PCR products were purified using the Promega PCR Product and Gel Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Subsequently, the purified PCR products were sequenced using Big Dye Cycle Sequencing kit V3.1. The successful sequences were processed on a 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using Genetyx Version 12.0 (GENETYX Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized using the R package dplyr v1.0.7 (RStudio, Boston, MA, USA) and visualized using the basic R program. Additionally, a comparison of the positivity among sites was carried out using ANOVA, and Tukey’s HSD test was applied for multiple comparisons with significance of p-value ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Detection of Adenovirus and Rotavirus

Of the 20 samples tested, 18/20 (90%) and 14/20 (70%) samples tested positive for HAdV and RVA on qPCR, respectively (

Table 3). The 16 positives for HAdV were distributed by site namely, Chelstone (n = 3), Kaunda square (n=5), Mass media (n=5), and Manchinchi (n=5) (

Table 3). Equally, for RVA the 14 positives consisted of; Chelstone (n=3), Kaunda square (n=4), Mass media (n=3), and Manchinchi (n=5). On conventional PCR for HAdV, 18 /20 were positive consisting of Chelstone (n= 3), Kaunda square (n=5), Mass media (n=5), and Manchinchi (n=5) (

Table 3).

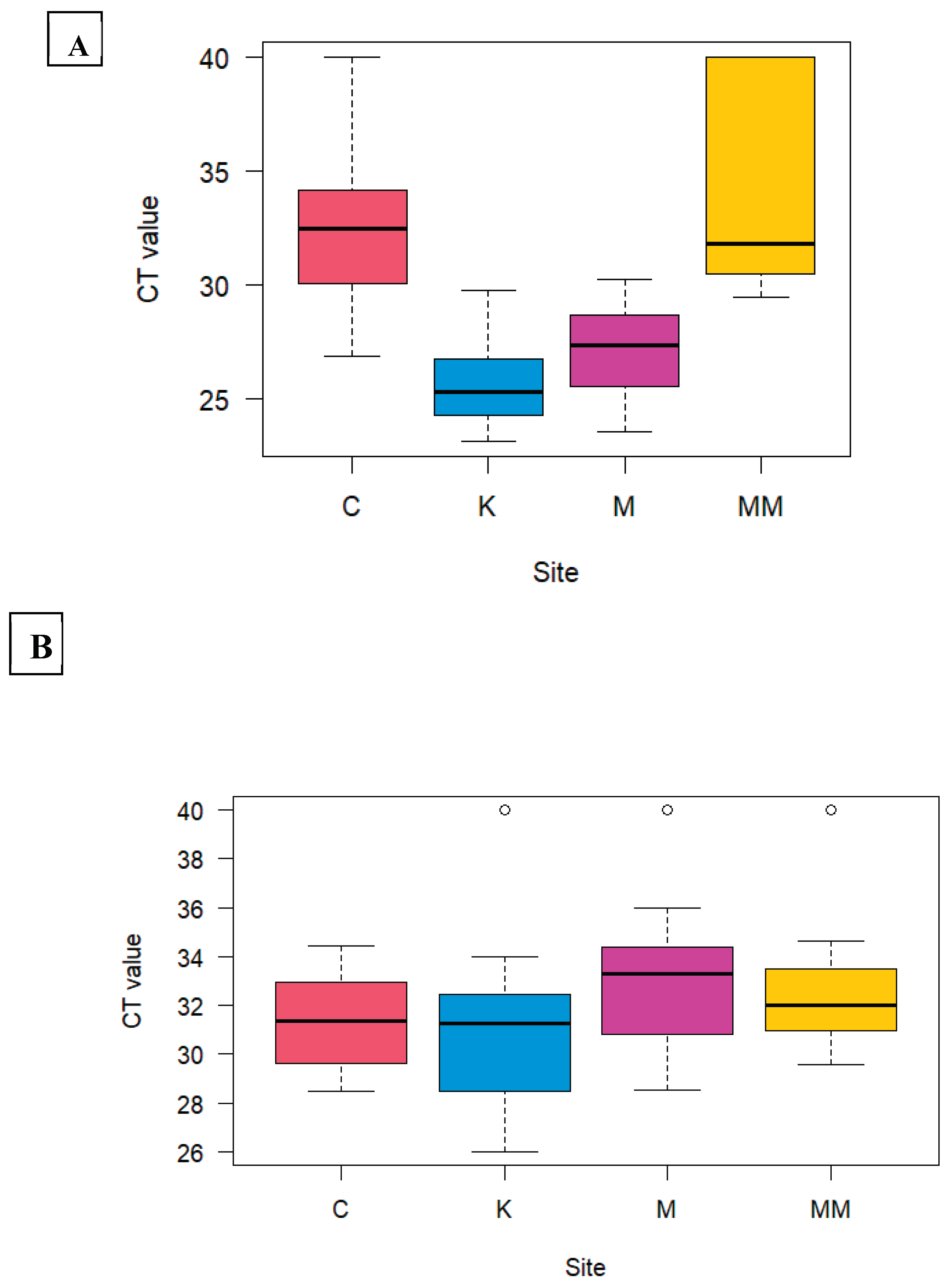

HAdV detection among the study sites showed a significant difference (P <0.05) between Kaunda square and Chelstone, Manchinchi and Chelstone, Kaunda square and Mass media, and Manchinchi and Mass media (

Figure 3A) (

Table 4). RVA did not show significant difference in positivity in all the sites (

Figure 3B)(

Table 5).

On conventional PCR, 11/18 were successfully sequenced and BLASTn revealed a nucleotide sequence similarity to HAdV with the percentage identity ranging from 98.48% to 99.53% (

Table 6).

3.2. Comparison of Viral Concentration Methods

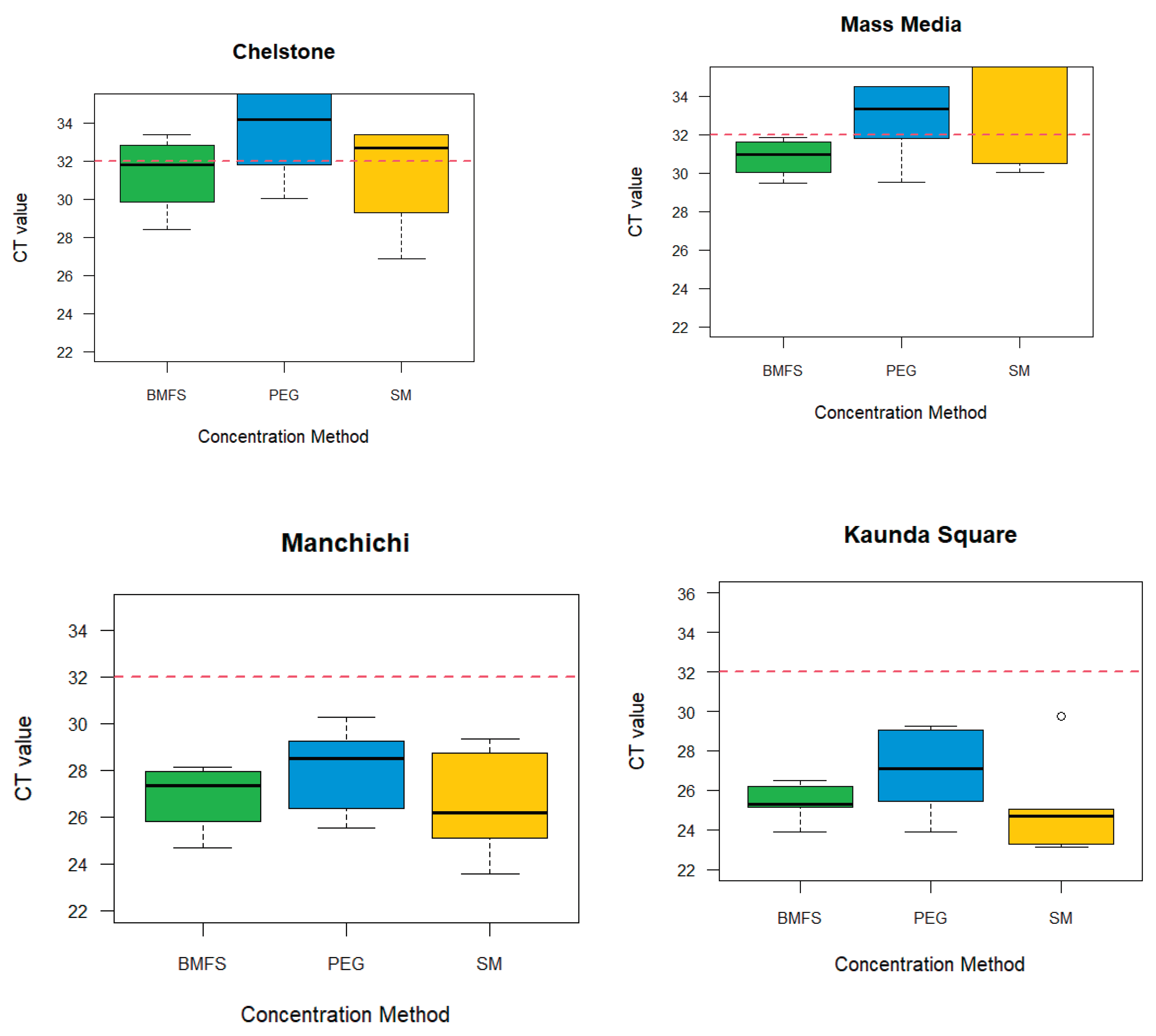

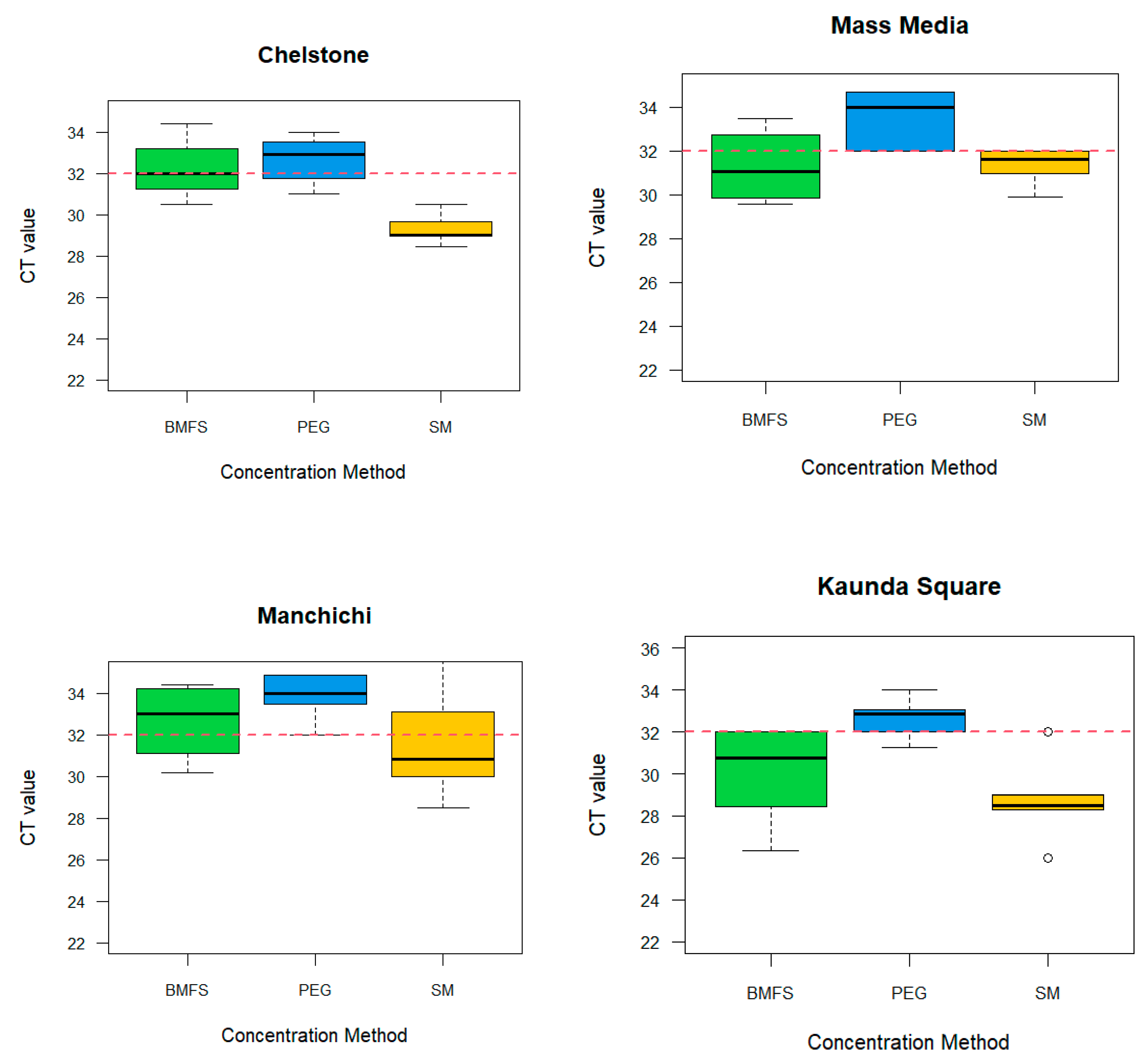

We examined the effectiveness of three viral concentration methods namely, BMFs, PEG precipitation, and SM flocculation using HAdV and RVA. The results from the three methods (BMFs, PEG and SMF) showed that the effectiveness varied from site to site (

Figure 1). Out of the 20 samples, BMFS and SM flocculation had 14/20, (70%) HAdV positives each and PEG precipitation 13/20, (65%)

Supplementary Table S7). On the other hand, SM flocculation (10/20, 50%), was most consistent on RVA positivity from all the study sites, followed by PEG (6/20, 30%), and BMFs (7/20, 35%) (

Figure 2,

Supplementary Table S7). However, there was no significant difference among concentration methods

Figure 1.

HAdV: Comparison of viral concentration methods for the detection in wastewater by site based on the cycle threshold of 32.

Figure 1.

HAdV: Comparison of viral concentration methods for the detection in wastewater by site based on the cycle threshold of 32.

Figure 2.

RVA: Comparison of viral concentration methods for the detection in wastewater by site based on the cycle threshold of 32.

Figure 2.

RVA: Comparison of viral concentration methods for the detection in wastewater by site based on the cycle threshold of 32.

Figure 3.

HAdV (A) and RVA (B); Analysis of the difference in the positivity of using Tukey’s HSD on ANOVA on the four study sites namely: Chelstone (C), Mass media (MM), Kaunda square (K), Manchinchi (M).

Figure 3.

HAdV (A) and RVA (B); Analysis of the difference in the positivity of using Tukey’s HSD on ANOVA on the four study sites namely: Chelstone (C), Mass media (MM), Kaunda square (K), Manchinchi (M).

4. Discussion

We investigated the presence of HAdV and RVA in wastewater as an alternative method for supplementary surveillance of enteric pathogens. To our knowledge, this is the first report of RVA and HAdV detection from wastewater in Zambia and this may set a basis for employing viral pathogen investigation in sewage and as a potential environmental surveillance strategy for other pathogens.

Our objective, was fulfilled by screening 20 untreated wastewater samples from four sites in five weeks, of which 18 and 14 were positive for HAdV and RVA respectively, resulting in a prevalence of 90% (18/20) and 70% (14/20), respectively. The results are consistent with the global trend which showed that HAdV is more prevalent in wastewater than RVA [

5]. Notably the prevalence for HAdV was higher than those that were obtained in other African countries like South Africa (64%), Morocco (45.5%), and Egypt (67%) [

3,

7]. However, when compared with other regions outside Africa such as Brazil (100%), Norway (92%), Michigan (99%), and Greece (92.3%) the prevalence for HAdV was lower [

1,

3]. This variance could be attributable to differences in the intervention strategies, sampling and detection methods [

24,

25].

With regard to RVA, the prevalence (70%) fell within the global prevalence of RVA of 38%-67% [

10], hence this is a significant finding because diarrhea-associated death is among the major health problems globally. Furthermore, recent reports have shown that one in every 260 children born dies from RVA-associated infections [

10,

18]. Detection of RVA, a regularly implicated acute gastroenteritis-causing pathogen in the young population, is critical in developing effective control measures in communities. By conducting virus surveillance in wastewater to identify high-risk areas, the negative public health impact may be mitigated. The high prevalence of RVA detected in our study suggests that considerable effort is necessary to improve the current RVA control interventions that are being employed in communities.

The high level of detection of these two enteric viruses in wastewater is an indication that surveillance of wastewater is critical in assessing the effectiveness of current interventions and in identifying areas for potential outbreaks occurrence. Therefore, surveillance of wastewater is essential in understanding how prevalent these pathogens are in the communities. This is important because HAdV and RVA are among the most implicated enteric viruses that cause respiratory infection and acute gastral enteritis in children, respectively [

3,

10].

We compared three viral concentration methods for wastewater analysis. All the methods were effective for the viruses under investigation. With regard to the cost associated with these methods, SM and PEG may be recommended for routine surveillance in resource limited settings. Nonetheless, BMFS and SM were the favoured for HAdV, while SM flocculation was the most effective for RVA. While some studies have suggested that PEG precipitation was an effective viral concentration method, it was the least effective in our study [

2,

26,

27]. In addition, other viral concentration method such as ultracentrifugation have been reported to be effective in wastewater viral concentration [

24].

We also compared the number of positives per site and our study revealed that viral shedding differed by site. This suggests that more interventions may be employed in areas service by Manchinchi and Kaunda square treatment sites. The differences in sites emphasizes the need for targeted surveillance of enteric pathogens in wastewater when identifying potential risk areas [

11,

28]. This is critical in guiding policy towards the control of pathogenic enteric and other related public health illnesses in Zambia.

5. Conclusions

The demonstration of HAdV and RVA in Zambian wastewater has been reported for the first time in this investigation. The approaches should be harnessed and utilized to track wastewater-borne pathogens as well as identification of potential risk areas for enteric virus outbreaks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org,. Table S7; Sites showing the results and the methods used for detection of HAdV, and RVA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda, Fred Chimpukutu, Musole Chipoya, Muzala Kapina, Joyce Siwila and King Nalubamba; Data curation, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda and Fred Chimpukutu; Formal analysis, Ngonda Saasa, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda and Joyce Siwila; Funding acquisition, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire, Mulenga Mwenda, Todd Jennings, Misheck Shawa, Kajihara Masahiro, Ayato Takada, Hirofumi Sawa, Roma Chilengi, Earnest Muyunda, King Nalubamba and Bernard Hang’ombe; Investigation, Ngonda Saasa, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda, Andrew Mukubesa, Doreen Shempela, Jay Sikalima, Carol Chiyesu, Bruce Muvwanga, Sarah Nampokolwe, Clement Sulwe, Thokozile Khondiwa, Wizaso Mwasinga, Jelaimo Mumeka and Misheck Shawa; Methodology, Ngonda Saasa, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda, Fred Chimpukutu, Thokozile Khondiwa, Conceptor Mulube and Joyce Siwila; Project administration, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire, Mulenga Mwenda and Fred Njobvu; Resources, Mulenga Mwenda, Fred Chimpukutu, Doreen Shempela, Jay Sikalima, Ameck Kamanga, Edgar Simulundu, Jelaimo Mumeka, John Simwanza, Patrick Sakubita, Otridah Kapona, Chilufya Mulenga, Musole Chipoya, Kunda Musonda, Nathan Kapata, Nyambe Sinyange, Muzala Kapina, Joyce Siwila, Kajihara Masahiro, Ayato Takada, Hirofumi Sawa, Simulyamana Choonga, Roma Chilengi, Earnest Muyunda, King Nalubamba and Bernard Hang’ombe; Supervision, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire and Fred Chimpukutu; Validation, Ngonda Saasa and Joseph Ndebe; Visualization, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda and Misheck Shawa; Writing – original draft, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda and Fred Chimpukutu; Writing – review & editing, Ngonda Saasa, Ethel M’kandawire, Joseph Ndebe, Mulenga Mwenda, Fred Chimpukutu, Andrew Mukubesa, Fred Njobvu, Doreen Shempela, Jay Sikalima, Clement Sulwe, Thokozile Khondiwa, Todd Jennings, Ameck Kamanga, Edgar Simulundu, Conceptor Mulube, Wizaso Mwasinga, Jelaimo Mumeka, John Simwanza, Patrick Sakubita, Otridah Kapona, Chilufya Mulenga, Musole Chipoya, Kunda Musonda, Nathan Kapata, Nyambe Sinyange, Muzala Kapina, Joyce Siwila, Misheck Shawa, Kajihara Masahiro, Ayato Takada, Hirofumi Sawa, Simulyamana Choonga, Roma Chilengi, Earnest Muyunda, King Nalubamba and Bernard Hang’ombe.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the Bayer Cares Foundation through a grant to PATH-Zambia (AWD-585926) and by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grants JP223fa627005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the National Health Research Authority (NHRA) Ref No: NHRA000001/14/11/2022 and wastewater samples potentially containing Rotavirus and Adenoviruses were processed in accordance with standard biosafety guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study is are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University of Zambia School of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Disease Control for the generous ongoing support for disease surveillance. We would like to thank the Lusaka Water Supply and Sanitation Company, particularly the staff working at the wastewater treatment plants and pump stations for supporting the research teams during the sample collection. We would also like to thank the PATH operations team for their support in ensuring that all the logistics were in place throughout the period of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fong TT, Phanikumar MS, Xagoraraki I, Rose JB. Quantitative detection of human adenoviruses in wastewater and combined sewer overflows influencing a Michigan river. Appl Environ Microbiol 2010;76. [CrossRef]

- Ali W, Zhang H, Wang Z, Chang C, Javed A, Ali K, et al. Occurrence of various viruses and recent evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater systems. J Hazard Mater 2021;414. [CrossRef]

- Allayeh AK, Al-Daim SA, Ahmed N, El-Gayar M, Mostafa A. Isolation and Genotyping of Adenoviruses from Wastewater and Diarrheal Samples in Egypt from 2016 to 2020. Viruses 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Osuolale O, Okoh A. Incidence of human adenoviruses and Hepatitis A virus in the final effluent of selected wastewater treatment plants in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Virol J 2015;12. [CrossRef]

- El-Senousy WM, Barakat AB, Ghanem HE, Kamel MA. Molecular epidemiology of human adenoviruses and rotaviruses as candidate viral indicators in the Egyptian sewage and water samples. World Appl Sci J 2013;27. [CrossRef]

- Soltane R, Allayeh AK. Occurrence of enteroviruses, noroviruses, rotaviruses, and adenoviruses in a wastewater treatment plant. Journal of Umm Al-Qura University for Applied Sciences 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Adefisoye MA, Nwodo UU, Green E, Okoh AI. Quantitative PCR Detection and Characterisation of Human Adenovirus, Rotavirus and Hepatitis A Virus in Discharged Effluents of Two Wastewater Treatment Facilities in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Food Environ Virol 2016;8. [CrossRef]

- Steele AD, Victor JC, Carey ME, Tate JE, Atherly DE, Pecenka C, et al. Experiences with rotavirus vaccines: can we improve rotavirus vaccine impact in developing countries? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019;15. [CrossRef]

- Duncan Steele A, Groome MJ. Measuring rotavirus vaccine impact in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020;70. [CrossRef]

- Atabakhsh P, Kargar M, Doosti A. Detection and evaluation of rotavirus surveillance methods as viral indicator in the aquatic environments. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2021;52. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair RG, Choi CY, Riley MR, Gerba CP. Chapter 9 Pathogen Surveillance Through Monitoring of Sewer Systems. Adv Appl Microbiol, vol. 65, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Xagoraraki I, O’Brien E. Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Early Detection of Viral Outbreaks, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Qi R, Huang Y ting, Liu J wei, Sun Y, Sun X feng, Han HJ, et al. Global Prevalence of Asymptomatic Norovirus Infection: A Meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2018;2–3. [CrossRef]

- Kitajima M, Ahmed W, Bibby K, Carducci A, Gerba CP, Hamilton KA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: State of the knowledge and research needs. Science of the Total Environment 2020;739. [CrossRef]

- Savolainen-Kopra C, Paananen A, Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Simonen ML, Lappalainen M, et al. A large Finnish echovirus 30 outbreak was preceded by silent circulation of the same genotype. Virus Genes 2011;42. [CrossRef]

- Hellmér M, Paxéus N, Magnius L, Enache L, Arnholm B, Johansson A, et al. Detection of pathogenic viruses in sewage provided early warnings of hepatitis A virus and norovirus outbreaks. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014;80. [CrossRef]

- Prevost B, Lucas FS, Goncalves A, Richard F, Moulin L, Wurtzer S. Large scale survey of enteric viruses in river and waste water underlines the health status of the local population. Environ Int 2015;79. [CrossRef]

- Shachakanza J, Zulu JM, Maimbolwa M. Incidence of Rotavirus Infection among Under-Five Children Attending Health Centres in Selected Communities of Ndola, Copperbelt Province, Zambia. Health N Hav 2019;11. [CrossRef]

- Chisenga CC, Bosomprah S, Makabilo Laban N, Mwila- Kazimbaya K, Mwaba J, Simuyandi M, et al. vAetiology of Diarrhoea in Children Under Five in Zambia Detected Using Luminex xTAG Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel. Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Open Access 2018;03. [CrossRef]

- Prata C, Ribeiro A, Cunha Â, Gomes NCM, Almeida A. Ultracentrifugation as a direct method to concentrate viruses in environmental waters: Virus-like particle enumeration as a new approach to determine the efficiency of recovery. Journal of Environmental Monitoring 2012;14. [CrossRef]

- Fagnant CS, Sánchez-Gonzalez LM, Zhou NA, Falman JC, Eisenstein M, Guelig D, et al. Improvement of the Bag-Mediated Filtration System for Sampling Wastewater and Wastewater-Impacted Waters. Food Environ Virol 2018;10. [CrossRef]

- Philo SE, Keim EK, Swanstrom R, Ong AQW, Burnor EA, Kossik AL, et al. A comparison of SARS-CoV-2 wastewater concentration methods for environmental surveillance. Science of the Total Environment 2021;760. [CrossRef]

- Jothikumar N, Cromeans TL, Hill VR, Lu X, Sobsey MD, Erdman DD. Quantitative real-time PCR assays for detection of human adenoviruses and identification of serotypes 40 and 41. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005;71. [CrossRef]

- Fumian TM, Leite JPG, Castello AA, Gaggero A, Caillou MSL de, Miagostovich MP. Detection of rotavirus A in sewage samples using multiplex qPCR and an evaluation of the ultracentrifugation and adsorption-elution methods for virus concentration. J Virol Methods 2010;170. [CrossRef]

- Elmahdy EM, Ahmed NI, Shaheen MNF, Mohamed ECB, Loutfy SA. Molecular detection of human adenovirus in urban wastewater in Egypt and among children suffering from acute gastroenteritis. J Water Health 2019;17. [CrossRef]

- Haramoto E, Malla B, Thakali O, Kitajima M. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Science of the Total Environment 2020;737. [CrossRef]

- Bonanno Ferraro G, Mancini P, Veneri C, Iaconelli M, Suffredini E, Brandtner D, et al. Evidence of Saffold virus circulation in Italy provided through environmental surveillance. Lett Appl Microbiol 2020;70. [CrossRef]

- Asghar H, Diop OM, Weldegebriel G, Malik F, Shetty S, Bassioni L El, et al. Environmental surveillance for polioviruses in the global polio eradication initiative. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014;210. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).