Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model and Method

3. Results

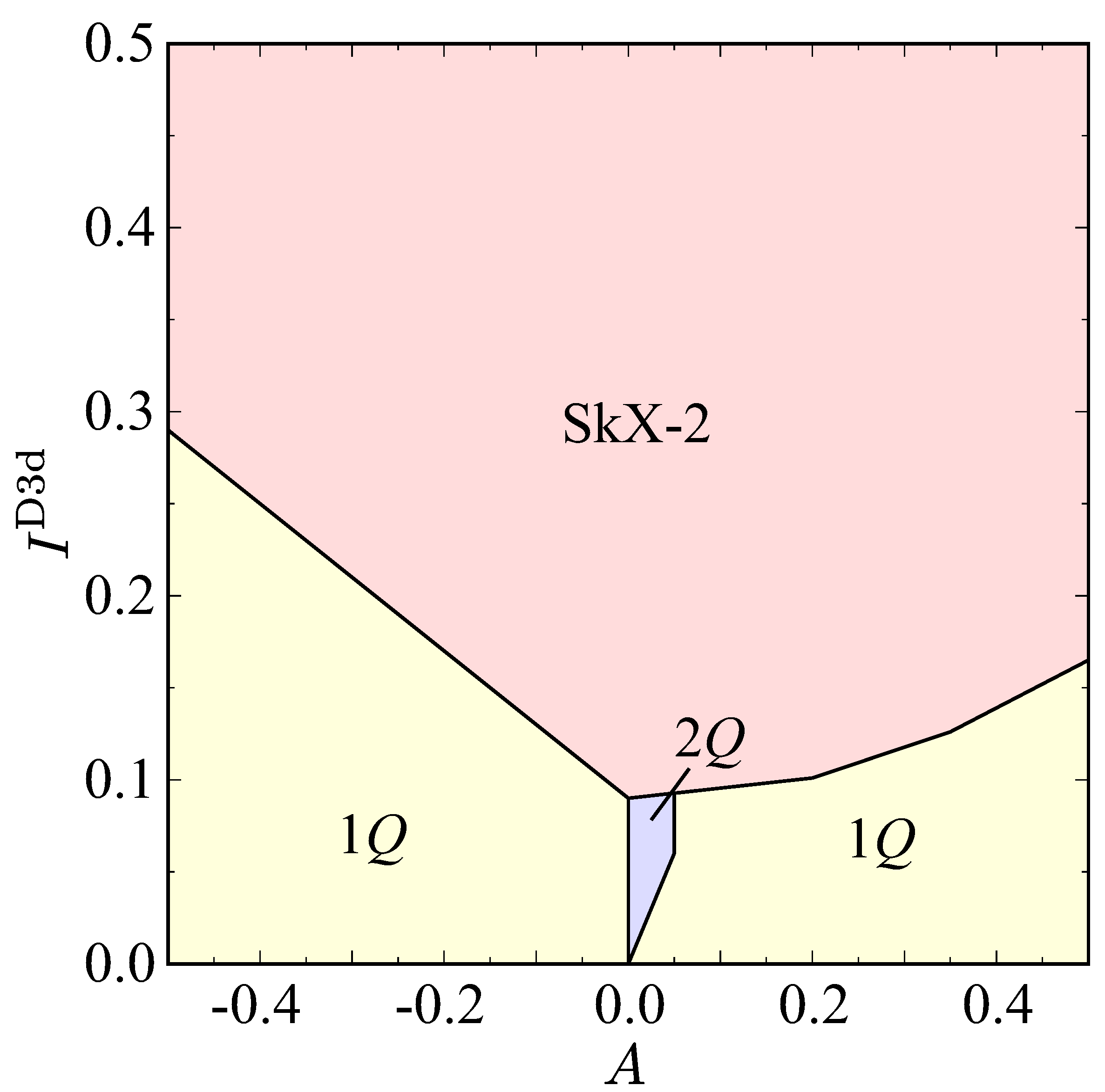

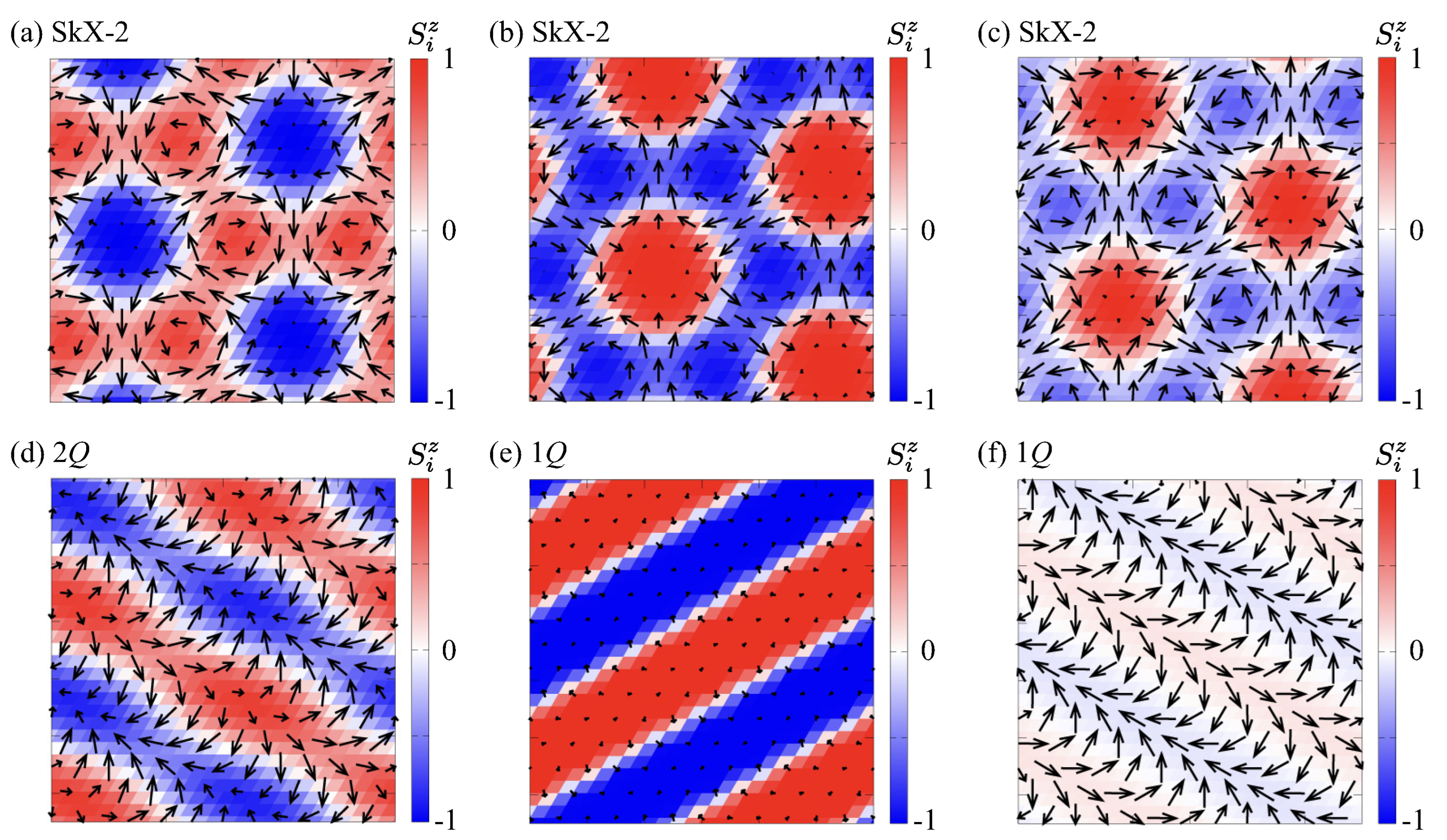

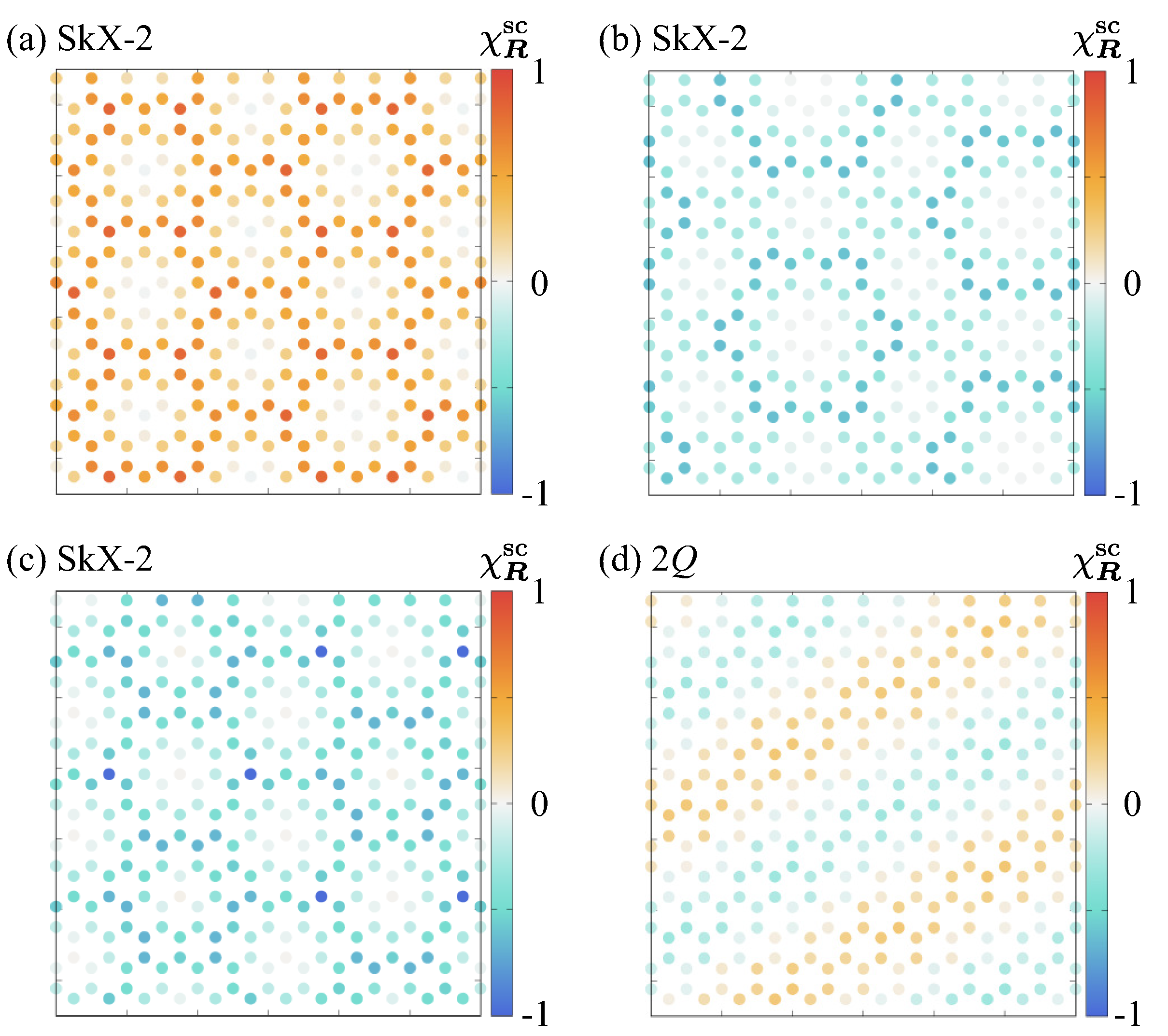

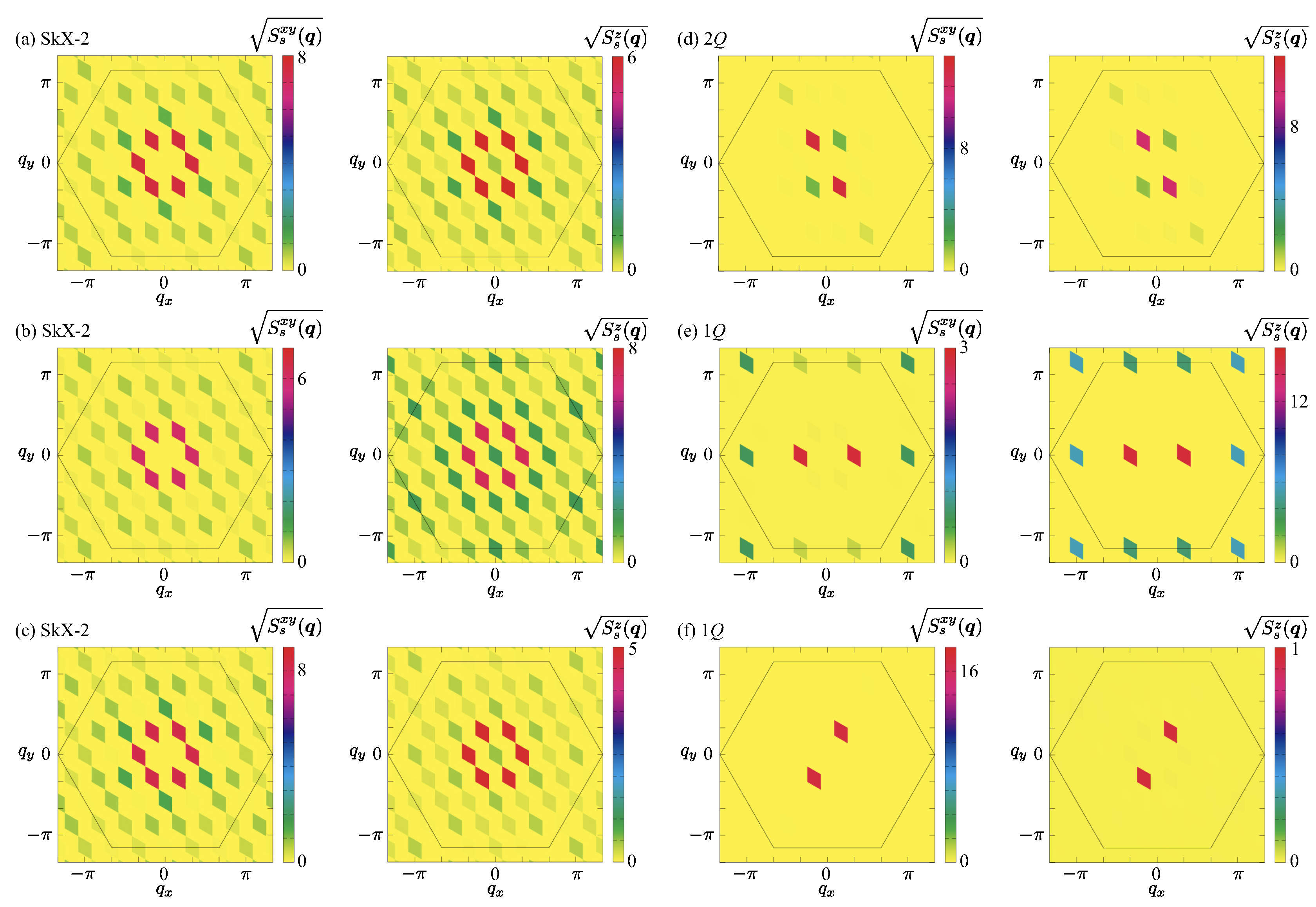

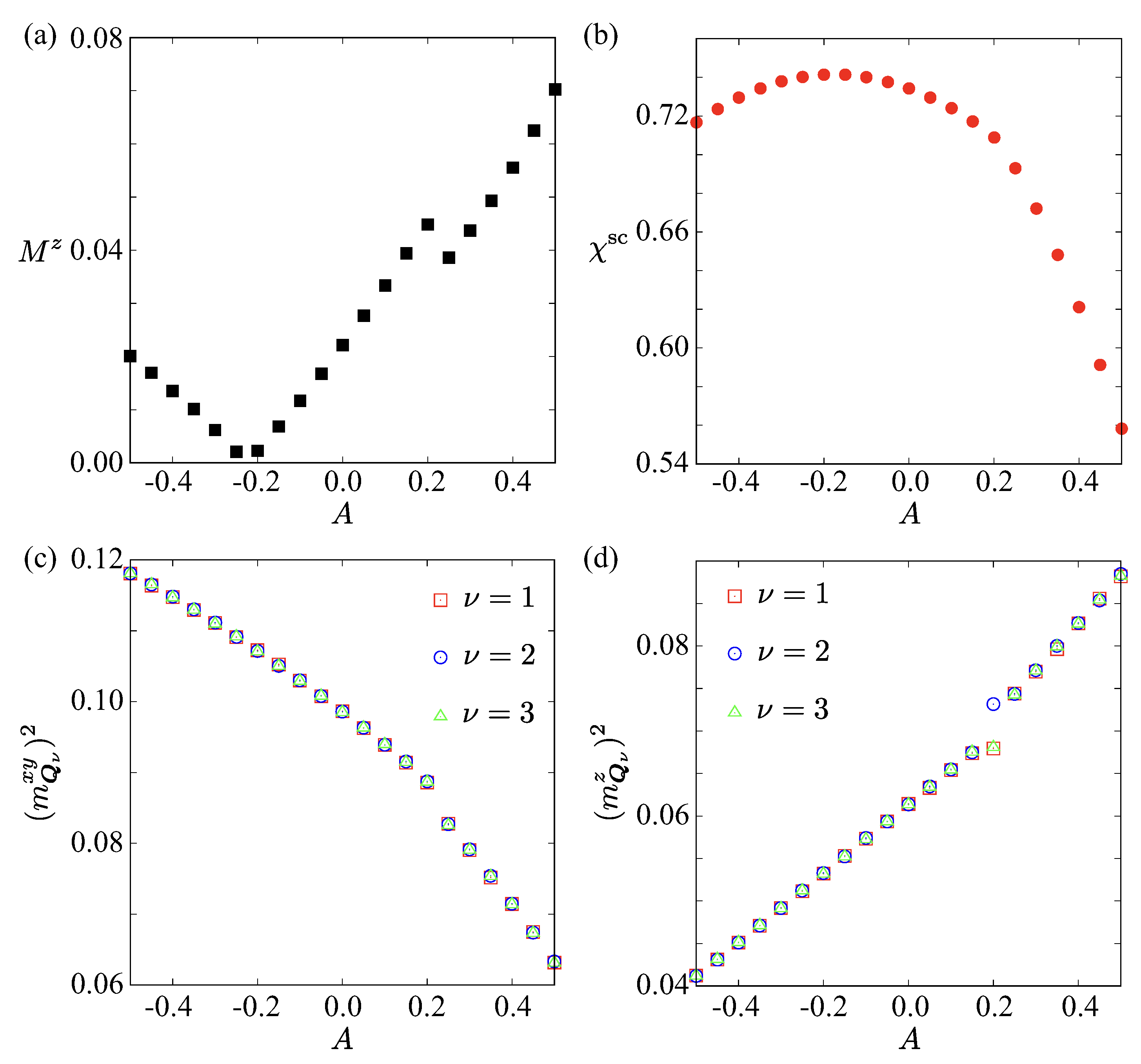

3.1. Zero Magnetic Field

3.2. Nonzero Magnetic Fields

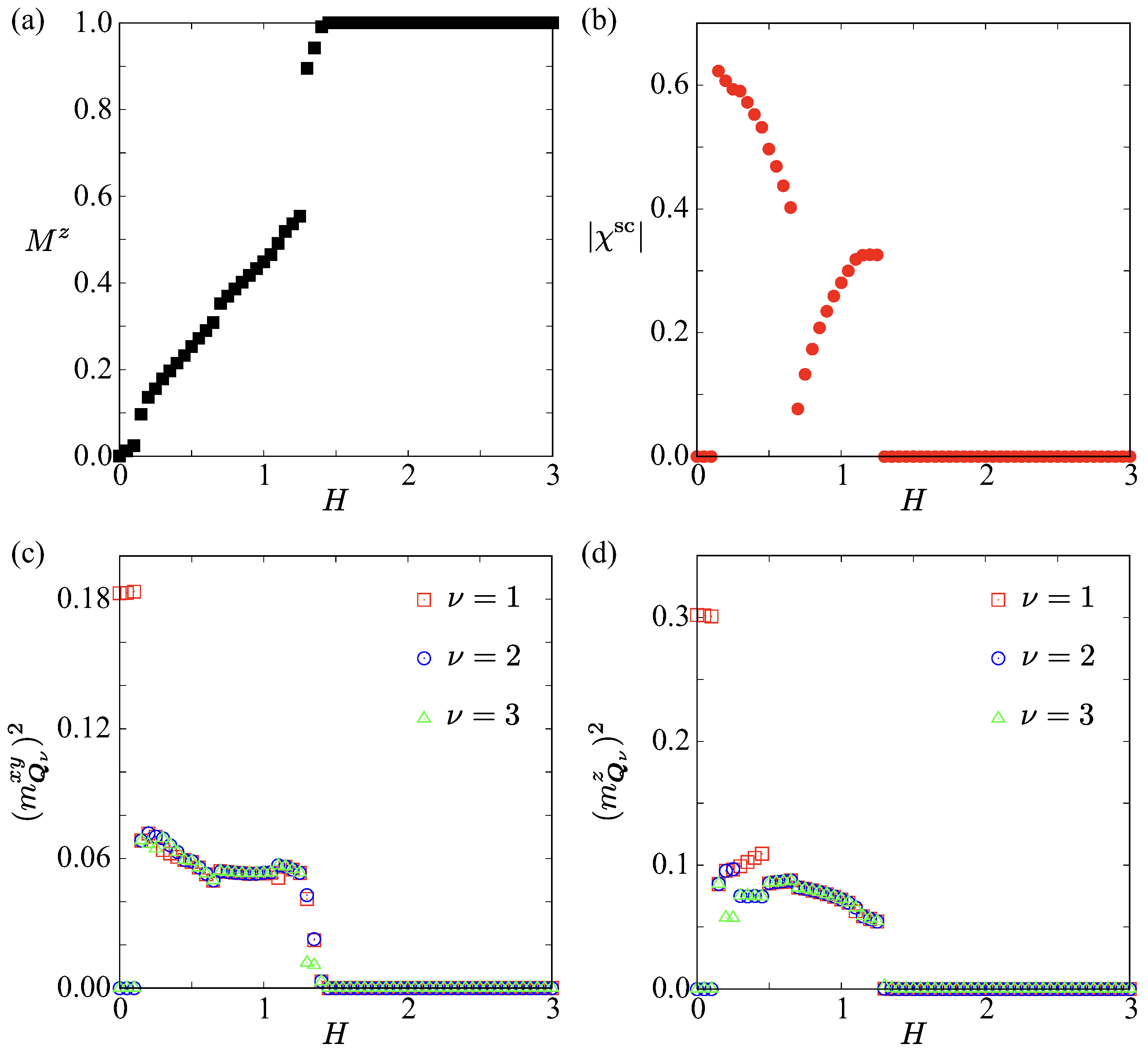

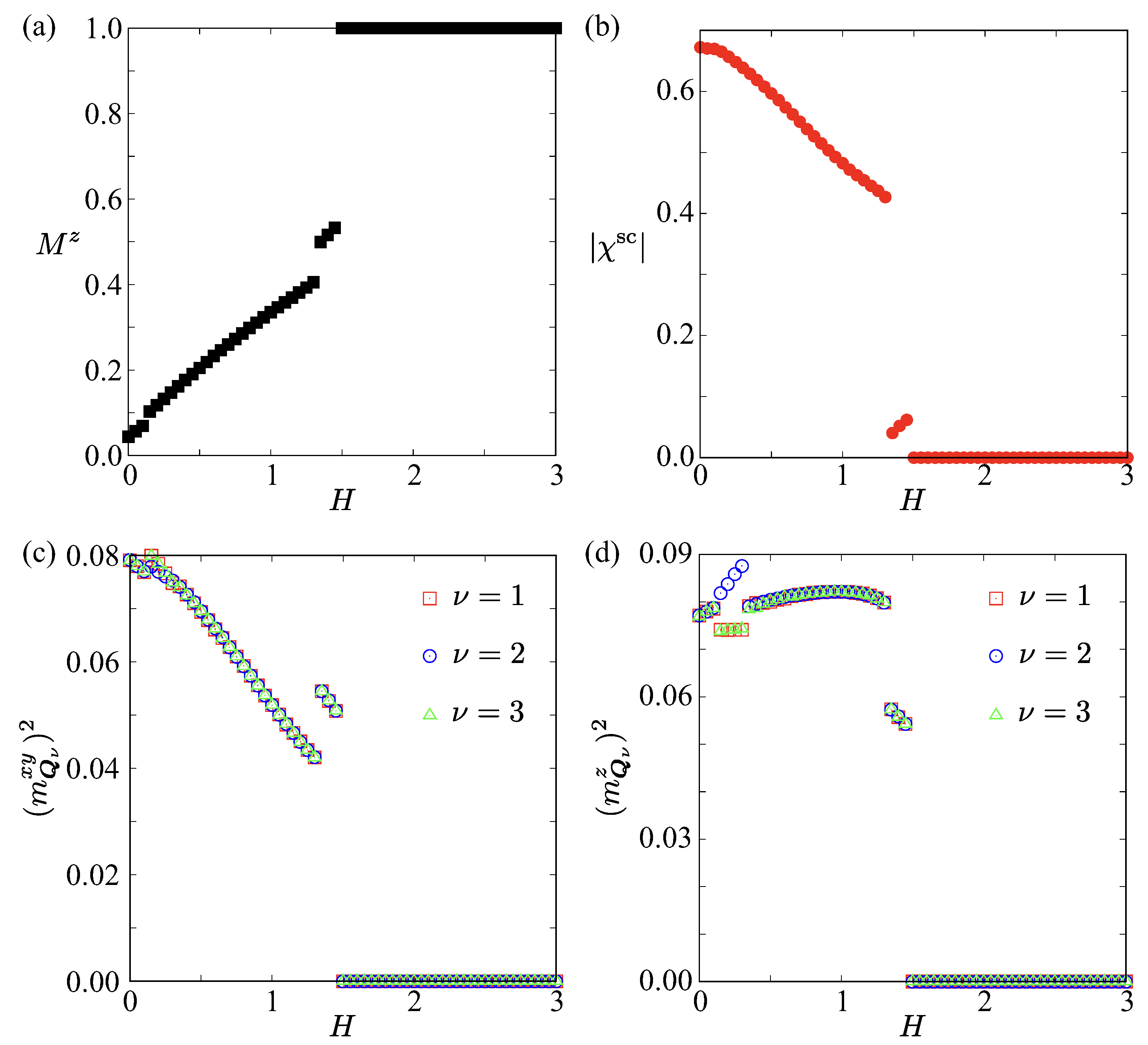

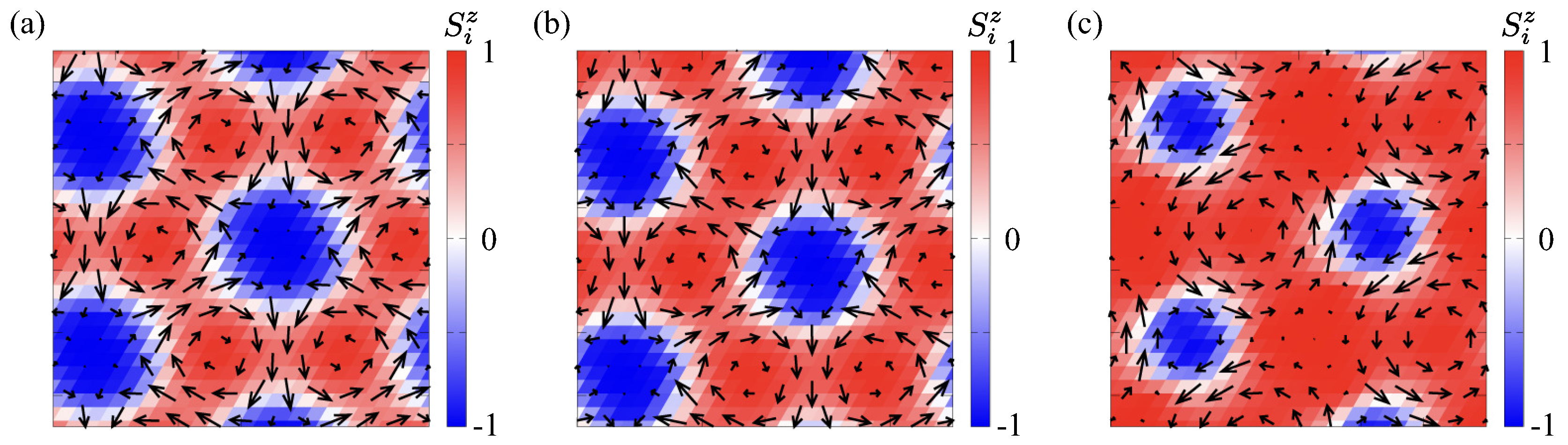

3.2.1. Weak -Type and Easy-Axis Anisotropies

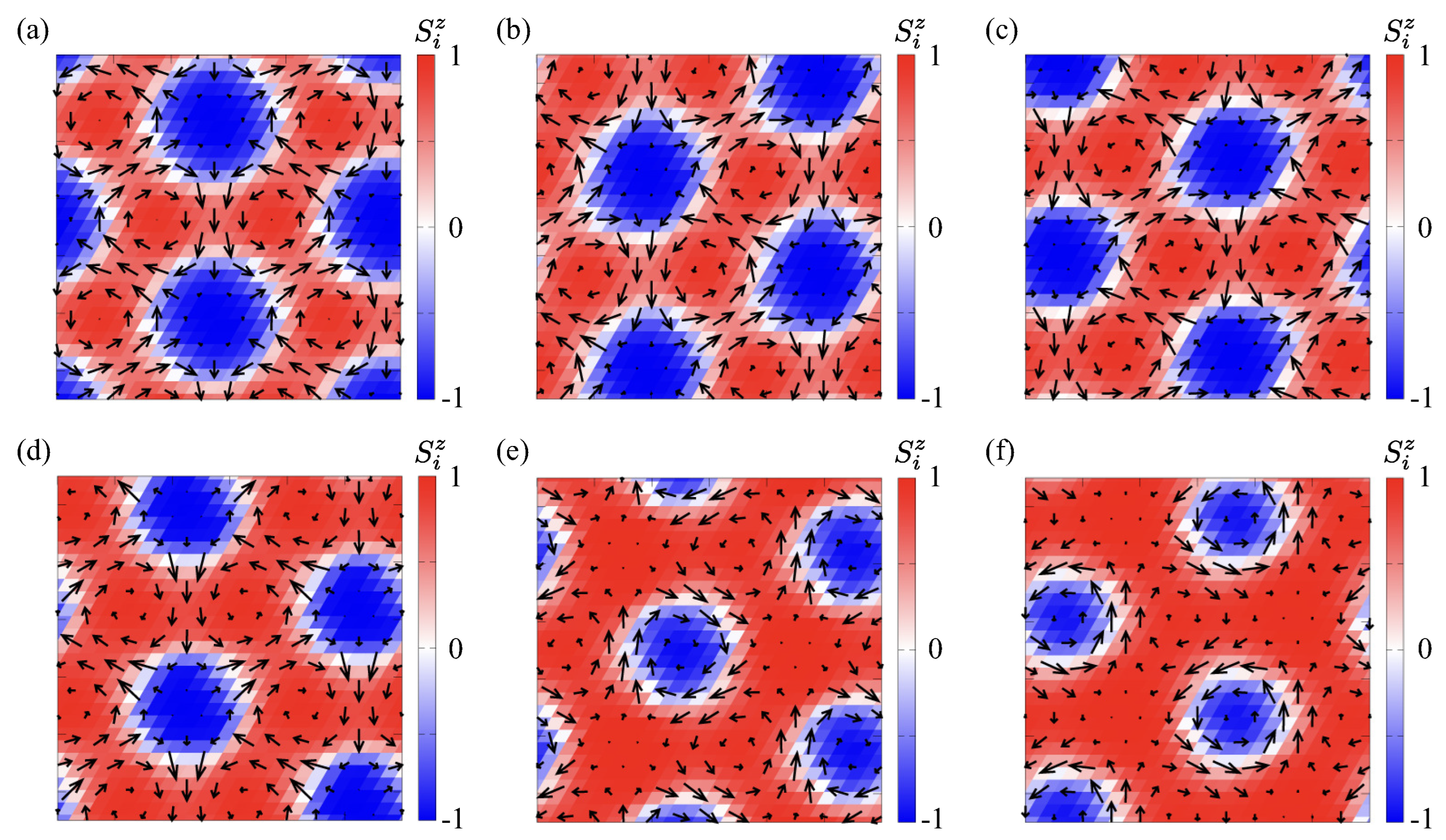

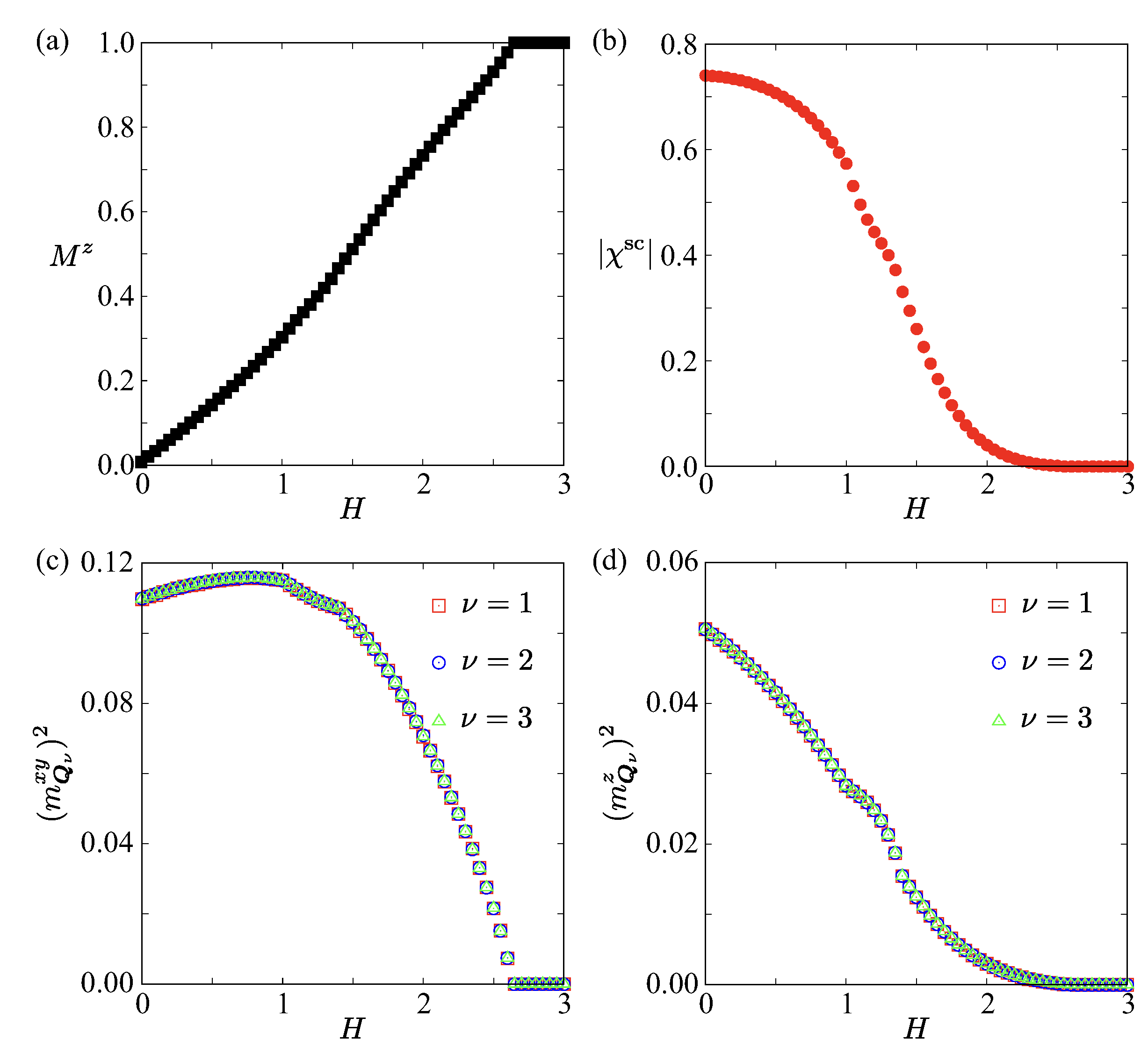

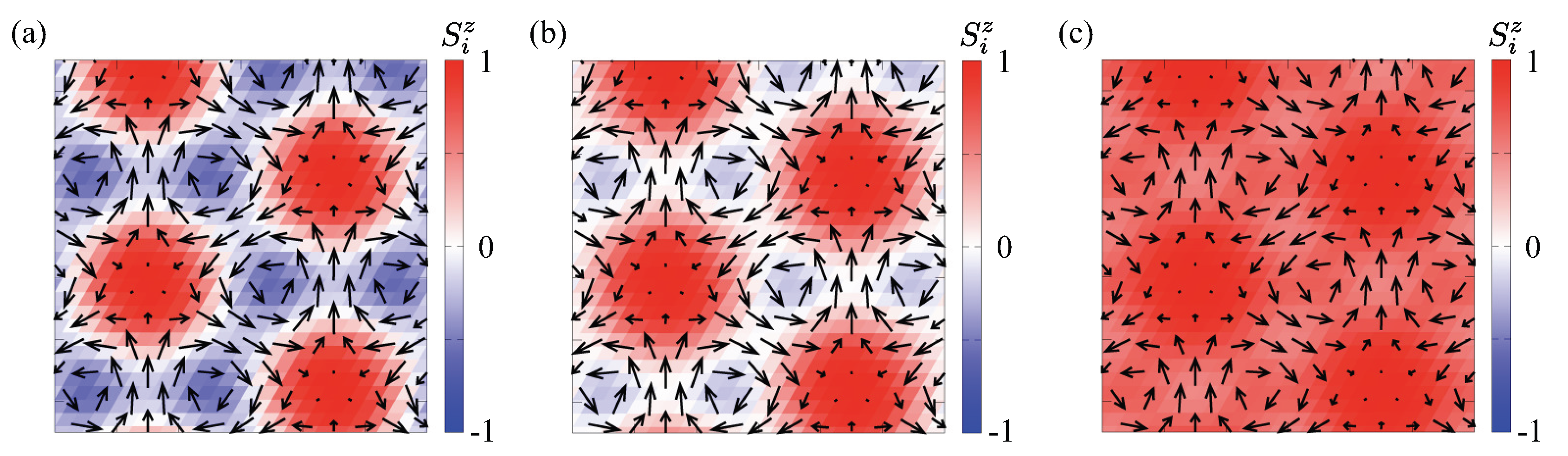

3.2.2. Weak -Type and Easy-Plane Anisotropies

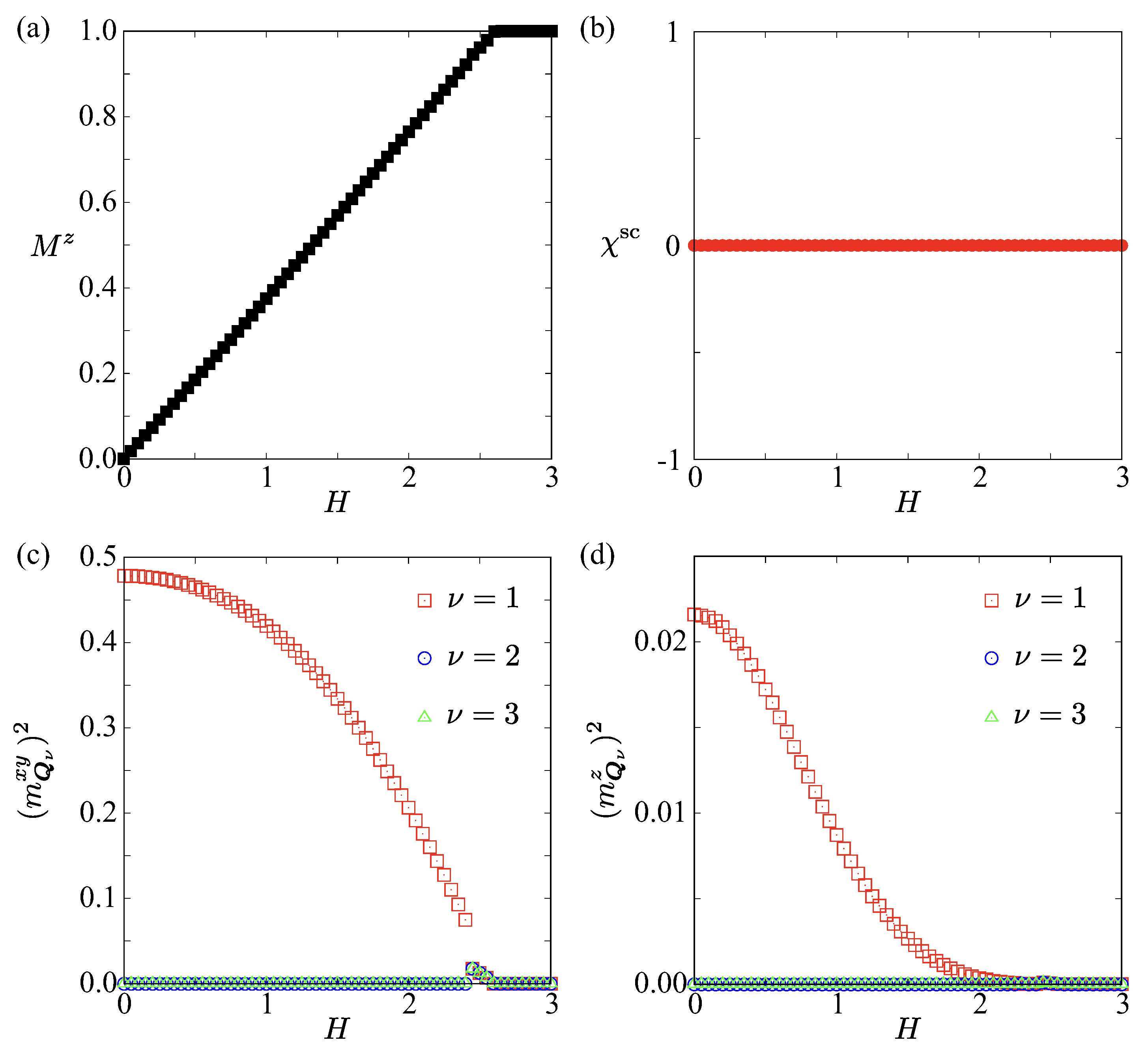

3.2.3. Strong -Type and Easy-Axis Anisotropies

3.2.4. Strong -Type and Easy-Plane Anisotropies

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Skyrme, T. A non-linear field theory. Proc. Roy. Soc 1961, 260, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A unified field theory of mesons and baryons. Nucl. Phys. 1962, 31, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Yablonskii, D.A. Thermodynamically stable “vortices" in magnetically ordered crystals: The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 1989, 68, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, A.; Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1994, 138, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fert, A.; Cros, V.; Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, W. Skyrmion-electronics: An overview and outlook. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 2040–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchio, G.; Büttner, F.; Tomasello, R.; Carpentieri, M.; Kläui, M. Magnetic skyrmions: from fundamental to applications. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2016, 49, 423001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fert, A.; Reyren, N.; Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 17031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, K.M.; Park, T.E.; Xia, J.; Ezawa, M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, G.; Woo, S. Skyrmion-electronics: writing, deleting, reading and processing magnetic skyrmions toward spintronic applications. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2020, 32, 143001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Panagopoulos, C. Physical foundations and basic properties of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2020, 2, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Kanazawa, N. Magnetic Skyrmion Materials. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichhardt, C.; Reichhardt, C.J.O.; Milošević, M.V. Statics and dynamics of skyrmions interacting with disorder and nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2022, 94, 035005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgushi, K.; Murakami, S.; Nagaosa, N. Spin anisotropy and quantum Hall effect in the kagomé lattice: Chiral spin state based on a ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, R6065–R6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.; Oohara, Y.; Yoshizawa, H.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Spin chirality, Berry phase, and anomalous Hall effect in a frustrated ferromagnet. Science 2001, 291, 2573–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatara, G.; Kawamura, H. Chirality-driven anomalous Hall effect in weak coupling regime. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 71, 2613–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C.; Binz, B.; Rosch, A.; Ritz, R.; Niklowitz, P.G.; Böni, P. Topological Hall Effect in the A Phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 186602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, K.; Ezawa, M.; Nagaosa, N. Quantized topological Hall effect in skyrmion crystal. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 115417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, K.; Bibes, M.; Kohno, H. Topological Hall effect from strong to weak coupling. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 033705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.; Dai, B.; Li, J.; Huang, H.; Chong, S.K.; Wong, K.L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Deng, P.; Eckberg, C.; et al. Distinguishing the two-component anomalous Hall effect from the topological Hall effect. ACS nano 2022, 16, 17336–17346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.; Cros, V.; Rohart, S.; Thiaville, A.; Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romming, N.; Hanneken, C.; Menzel, M.; Bickel, J.E.; Wolter, B.; von Bergmann, K.; Kubetzka, A.; Wiesendanger, R. Writing and deleting single magnetic skyrmions. Science 2013, 341, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, S.A.; Sturla, M.B.; Rosales, H.D.; Cabra, D.C. Stability of skyrmions in perturbed ferromagnetic chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 064439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Bheemarasetty, V.; Duan, J.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, G. Fundamental physics and applications of skyrmions: A review. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 563, 169905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, C.V.; Guimarães, A.P. Analysis of stability and transition dynamics of skyrmions and skyrmioniums in ferromagnetic nanodisks: A micromagnetic study at finite temperature. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 064437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1958, 4, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 1960, 120, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 2006, 442, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, B.; Vishwanath, A.; Aji, V. Theory of the Helical Spin Crystal: A Candidate for the Partially Ordered State of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 207202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binz, B.; Vishwanath, A. Theory of helical spin crystals: Phases, textures, and properties. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 214408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, B.; Vishwanath, A. Chirality induced anomalous-Hall effect in helical spin crystals. Physica B 2008, 403, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.D.; Onoda, S.; Nagaosa, N.; Han, J.H. Skyrmions and anomalous Hall effect in a Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya spiral magnet. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 054416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, S.; von Bergmann, K.; Menzel, M.; Brede, J.; Kubetzka, A.; Wiesendanger, R.; Bihlmayer, G.; Blügel, S. Spontaneous atomic-scale magnetic skyrmion lattice in two dimensions. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Binz, B.; Jonietz, F.; Pfleiderer, C.; Rosch, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 2009, 323, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Jonietz, F.; Bauer, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Keiderling, U.; Everschor, K.; et al. Long-Range Crystalline Nature of the Skyrmion Lattice in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 217206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, D.; Shibata, K.; Kanazawa, N.; Yu, X.Z.; Tokura, Y. Crystal chirality and skyrmion helicity in MnSi and (Fe, Co)Si as determined by transmission electron microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 024408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Garst, M.; Pfleiderer, C. Specific Heat of the Skyrmion Lattice Phase and Field-Induced Tricritical Point in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 177207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.N.; Butenko, A.B.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Monchesky, T.L. Chiral skyrmions in cubic helimagnet films: The role of uniaxial anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 094411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Onose, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Park, J.H.; Han, J.H.; Matsui, Y.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 2010, 465, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Neubauer, A.; Münzer, W.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Pedersen, B.; Böni, P.; Rosch, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Skyrmion lattice domains in Fe1-xCoxSi. Proceedings of the J. Phys. Conf. Ser. IOP Publishing 2010, 200, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzer, W.; Neubauer, A.; Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Franz, C.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Pedersen, B.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Skyrmion lattice in the doped semiconductor Fe1-xCoxSi. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 041203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Garst, M.; Pfleiderer, C. History dependence of the magnetic properties of single-crystal Fe1-xCoxSi. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 235144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Kanazawa, N.; Onose, Y.; Kimoto, K.; Zhang, W.; Ishiwata, S.; Matsui, Y.; Tokura, Y. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebech, B.; Bernhard, J.; Freltoft, T. Magnetic structures of cubic FeGe studied by small-angle neutron scattering. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1989, 1, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, S.; Yu, X.Z.; Ishiwata, S.; Tokura, Y. Observation of skyrmions in a multiferroic material. Science 2012, 336, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Chacon, A.; Wagner, M.; Bauer, A.; Brandl, G.; Pedersen, B.; Berger, H.; Lemmens, P.; Pfleiderer, C. Long-Wavelength Helimagnetic Order and Skyrmion Lattice Phase in Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 237204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, S.; Kim, J.H.; Inosov, D.S.; Georgii, R.; Keimer, B.; Ishiwata, S.; Tokura, Y. Formation and rotation of skyrmion crystal in the chiral-lattice insulator Cu2OSeO3. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 220406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumaji, T.; Nakajima, T.; Ukleev, V.; Feoktystov, A.; Arima, T.h.; Kakurai, K.; Tokura, Y. Néel-Type Skyrmion Lattice in the Tetragonal Polar Magnet VOSe2O5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 237201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.W.; Chen, C.C.; Kakarla, D.C.; Tiwari, A.; Wang, C.W.; Gooch, M.; Deng, L.Z.; Chu, C.W.; Yang, H.D.; Wu, H.C. Enhanced Néel-type skyrmion stability in polar VOSe2O5 through tunable magnetic anisotropy under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 024441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Chung, S.; Kawamura, H. Multiple-q States and the Skyrmion Lattice of the Triangular-Lattice Heisenberg Antiferromagnet under Magnetic Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 017206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Stabilization mechanisms of magnetic skyrmion crystal and multiple-Q states based on momentum-resolved spin interactions. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Frustration-induced skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 183004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Mostovoy, M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Lin, S.Z.; Kamiya, Y.; Batista, C.D. Vortices, skyrmions, and chirality waves in frustrated Mott insulators with a quenched periodic array of impurities. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utesov, O.I. Thermodynamically stable skyrmion lattice in a tetragonal frustrated antiferromagnet with dipolar interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 064414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utesov, O.I. Mean-field description of skyrmion lattice in hexagonal frustrated antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 054435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystal and spiral phases in centrosymmetric bilayer magnets with staggered Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 014408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Effective spin model in momentum space: Toward a systematic understanding of multiple-Q instability by momentum-resolved anisotropic exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.R.; Sugawara, H.; Matsuda, T.D.; Sato, H.; Mallik, R.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic anisotropy, first-order-like metamagnetic transitions, and large negative magnetoresistance in single-crystal Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 12162–12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumaji, T.; Nakajima, T.; Hirschberger, M.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Taguchi, Y.; Arima, T.h.; Tokura, Y. Skyrmion lattice with a giant topological Hall effect in a frustrated triangular-lattice magnet. Science 2019, 365, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Spitz, L.; Nomoto, T.; Kurumaji, T.; Gao, S.; Masell, J.; Nakajima, T.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; et al. Topological Nernst Effect of the Two-Dimensional Skyrmion Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 076602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Iyer, K.K.; Paulose, P.L.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic and transport anomalies in R2RhSi34pt0ex(R=Gd, Tb, and Dy) resembling those of the exotic magnetic material Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 144440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spachmann, S.; Elghandour, A.; Frontzek, M.; Löser, W.; Klingeler, R. Magnetoelastic coupling and phases in the skyrmion lattice magnet Gd2PdSi3 discovered by high-resolution dilatometry. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 184424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kabeya, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Araki, K.; Katoh, K.; Ochiai, A. Spin trimer formation in the metallic compound Gd3Ru4Al12 with a distorted kagome lattice structure. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 054410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Nakajima, T.; Gao, S.; Peng, L.; Kikkawa, A.; Kurumaji, T.; Kriener, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; et al. Skyrmion phase and competing magnetic orders on a breathing kagome lattice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Hayami, S.; Tokura, Y. Nanometric skyrmion lattice from anisotropic exchange interactions in a centrosymmetric host. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 023039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. Magnetic anisotropies and skyrmion lattice related to magnetic quadrupole interactions of the RKKY mechanism in the frustrated spin-trimer system Gd3Ru4Al12 with a breathing kagome structure. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 184433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, N.D.; Nakajima, T.; Yu, X.; Gao, S.; Shibata, K.; Hirschberger, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Peng, L.; et al. Nanometric square skyrmion lattice in a centrosymmetric tetragonal magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, N.; Nomura, T.; Imajo, S.; Nomoto, T.; Arita, R.; Sudo, K.; Kimata, M.; Khanh, N.D.; Takagi, R.; Tokura, Y.; et al. Quantum oscillations in the centrosymmetric skyrmion-hosting magnet GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.D.A.; Khalyavin, D.D.; Mayoh, D.A.; Bouaziz, J.; Hall, A.E.; Holt, S.J.R.; Orlandi, F.; Manuel, P.; Blügel, S.; Staunton, J.B.; et al. Double-Q ground state with topological charge stripes in the centrosymmetric skyrmion candidate GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, L180402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremeev, S.; Glazkova, D.; Poelchen, G.; Kraiker, A.; Ali, K.; Tarasov, A.V.; Schulz, S.; Kliemt, K.; Chulkov, E.V.; Stolyarov, V.; et al. Insight into the electronic structure of the centrosymmetric skyrmion magnet GdRu2Si2. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6678–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ezawa, M. High-topological-number magnetic skyrmions and topologically protected dissipative structure. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 024415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, R.; Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Zero-Field Skyrmions with a High Topological Number in Itinerant Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 147205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Spontaneous skyrmionic lattice from anisotropic symmetric exchange in a Ni-halide monolayer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S.; Tsuzuki, H.; Itoh, H.; Ohsawa, T. Magnetic structure of high-order skyrmion number produced in a nanodisk via micromagnetic simulation with long-range dipole-dipole interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 064417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Okubo, T.; Motome, Y. Phase shift in skyrmion crystals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eto, R.; Pohle, R.; Mochizuki, M. Low-Energy Excitations of Skyrmion Crystals in a Centrosymmetric Kondo-Lattice Magnet: Decoupled Spin-Charge Excitations and Nonreciprocity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 017201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yatsushiro, M. Nonlinear nonreciprocal transport in antiferromagnets free from spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 014420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Effect of magnetic anisotropy on skyrmions with a high topological number in itinerant magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 094420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple-Q magnetism by anisotropic bilinear-biquadratic interactions in momentum space. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 513, 167181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple skyrmion crystal phases by itinerant frustration in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 023705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Noncoplanar multiple-Q spin textures by itinerant frustration: Effects of single-ion anisotropy and bond-dependent anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 054422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Lin, S.Z.; Batista, C.D. Meron, skyrmion, and vortex crystals in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric itinerant magnets without horizontal mirror plane. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenko, A.B.; Leonov, A.A.; Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N. Stabilization of skyrmion textures by uniaxial distortions in noncentrosymmetric cubic helimagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 052403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Z.; Saxena, A.; Batista, C.D. Skyrmion fractionalization and merons in chiral magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 224407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Monchesky, T.L.; Romming, N.; Kubetzka, A.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Wiesendanger, R. The properties of isolated chiral skyrmions in thin magnetic films. New. J. Phys. 2016, 18, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Kézsmárki, I. Asymmetric isolated skyrmions in polar magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 014423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. In-plane magnetic field-induced skyrmion crystal in frustrated magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 224418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, P.; Moore, M.W.; Wilkinson, C.; Ziebeck, K.R.A. Neutron diffraction study of the incommensurate magnetic phase of Ni0.92Zn0.08Br2. J. Phys. C: Solid State Physics 1981, 14, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, L.; Rossat-Mignod, J.; Adam, A.; Billerey, D.; Terrier, C. Inelastic neutron scattering investigation of the magnetic excitations in the helimagnetic state of NiBr2. Journal de Physique 1982, 43, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, S.; Nambu, Y.; Tonomura, H.; Sakai, O.; Jonas, S.; Broholm, C.; Tsunetsugu, H.; Qiu, Y.; Maeno, Y. Spin disorder on a triangular lattice. Science 2005, 309, 1697–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, N.; Ronning, F.; Williams, D.; Scott, B.; Luo, Y.; Thompson, J.; Bauer, E. Investigation of the physical properties of the tetragonal CeMAl4Si2 (M= Rh, Ir, Pt) compounds. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2014, 27, 025601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, M.A.; Kittel, C. Indirect Exchange Coupling of Nuclear Magnetic Moments by Conduction Electrons. Phys. Rev. 1954, 96, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, T. A Theory of Metallic Ferro- and Antiferromagnetism on Zener’s Model. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1956, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosida, K. Magnetic Properties of Cu-Mn Alloys. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Lin, S.Z.; Batista, C.D. Skyrmion Crystal from RKKY Interaction Mediated by 2D Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 207201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimori, A. A new type of antiferromagnetic structure in the rutile type crystal. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1959, 14, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, T.A. Some Effects of Anisotropy on Spiral Spin-Configurations with Application to Rare-Earth Metals. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.J. Phenomenological Discussion of Magnetic Ordering in the Heavy Rare-Earth Metals. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, M.; Aoki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Honda, F.; Nakashima, M.; Amako, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Sakakibara, T.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Giant Hall resistivity and magnetoresistance in cubic chiral antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 023701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Frontzek, M.D.; Matsuda, M.; Nakao, A.; Munakata, K.; Ohhara, T.; Kakihana, M.; Haga, Y.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Unique Helical Magnetic Order and Field-Induced Phase in Trillium Lattice Antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 013702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, C.; Matsumura, T.; Nakao, H.; Michimura, S.; Kakihana, M.; Inami, T.; Kaneko, K.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Magnetic Field Induced Triple-q Magnetic Order in Trillium Lattice Antiferromagnet EuPtSi Studied by Resonant X-ray Scattering. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 093704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, M.; Aoki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Honda, F.; Nakashima, M.; Amako, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Harima, H.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Unique Magnetic Phases in the Skyrmion Lattice and Fermi Surface Properties in Cubic Chiral Antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 094705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Ganesan, V. A-phase, field-induced tricritical point, and universal magnetocaloric scaling in EuPtSi. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 125113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, T.; Kakihana, M.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Magnetic field versus temperature phase diagram for H‖[001] in the trillium lattice antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 053703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Tabata, C.; Kaneko, K.; Nakao, H.; Kakihana, M.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Single helicity of the triple-q triangular skyrmion lattice state in the cubic chiral helimagnet EuPtSi. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Kurauchi, K.; Tsukagoshi, M.; Higa, N.; Nakao, H.; Kakihana, M.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Helicity Unification by Triangular Skyrmion Lattice Formation in the Noncentrosymmetric Tetragonal Magnet EuNiGe3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 93, 074705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, R.; White, J.; Hayami, S.; Arita, R.; Honecker, D.; Rønnow, H.; Tokura, Y.; Seki, S. Multiple-q noncollinear magnetism in an itinerant hexagonal magnet. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Field-Direction Sensitive Skyrmion Crystals in Cubic Chiral Systems: Implication to 4f-Electron Compound EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 073705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Fujishiro, Y.; Hayami, S.; Moody, S.H.; Nomoto, T.; Baral, P.R.; Ukleev, V.; Cubitt, R.; Steinke, N.J.; Gawryluk, D.J.; et al. Transition between distinct hybrid skyrmion textures through their hexagonal-to-square crystal transformation in a polar magnet. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, T. Single-band Hubbard model with spin-orbit coupling. Zeitschrift für Physik B Condensed Matter 1983, 49, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhtman, L.; Aharony, A.; Entin-Wohlman, O. Bond-dependent symmetric and antisymmetric superexchange interactions in La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomskii, D.; Mostovoy, M. Orbital ordering and frustrations. J. Phys. A 2003, 36, 9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackeli, G.; Khaliullin, G. Mott insulators in the strong spin-orbit coupling limit: From Heisenberg to a quantum compass and Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 017205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.D.; Wang, X.; Chen, G. Anisotropic spin model of strong spin-orbit-coupled triangular antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 035107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, P.A.; Zhu, Z.; White, S.R.; Chernyshev, A.L. Anisotropic-Exchange Magnets on a Triangular Lattice: Spin Waves, Accidental Degeneracies, and Dual Spin Liquids. Phys. Rev. X 2019, 9, 021017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Luscher, M. Definition and statistical distributions of a topological number in the lattice O(3) σ-model. Nucl. Phys. B 1981, 190, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Locking of skyrmion cores on a centrosymmetric discrete lattice: Onsite versus offsite. Phys. Rev. Research 2021, 3, 043158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, Y.; Batista, C.D. Magnetic Vortex Crystals in Frustrated Mott Insulator. Phys. Rev. X 2014, 4, 011023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).