Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

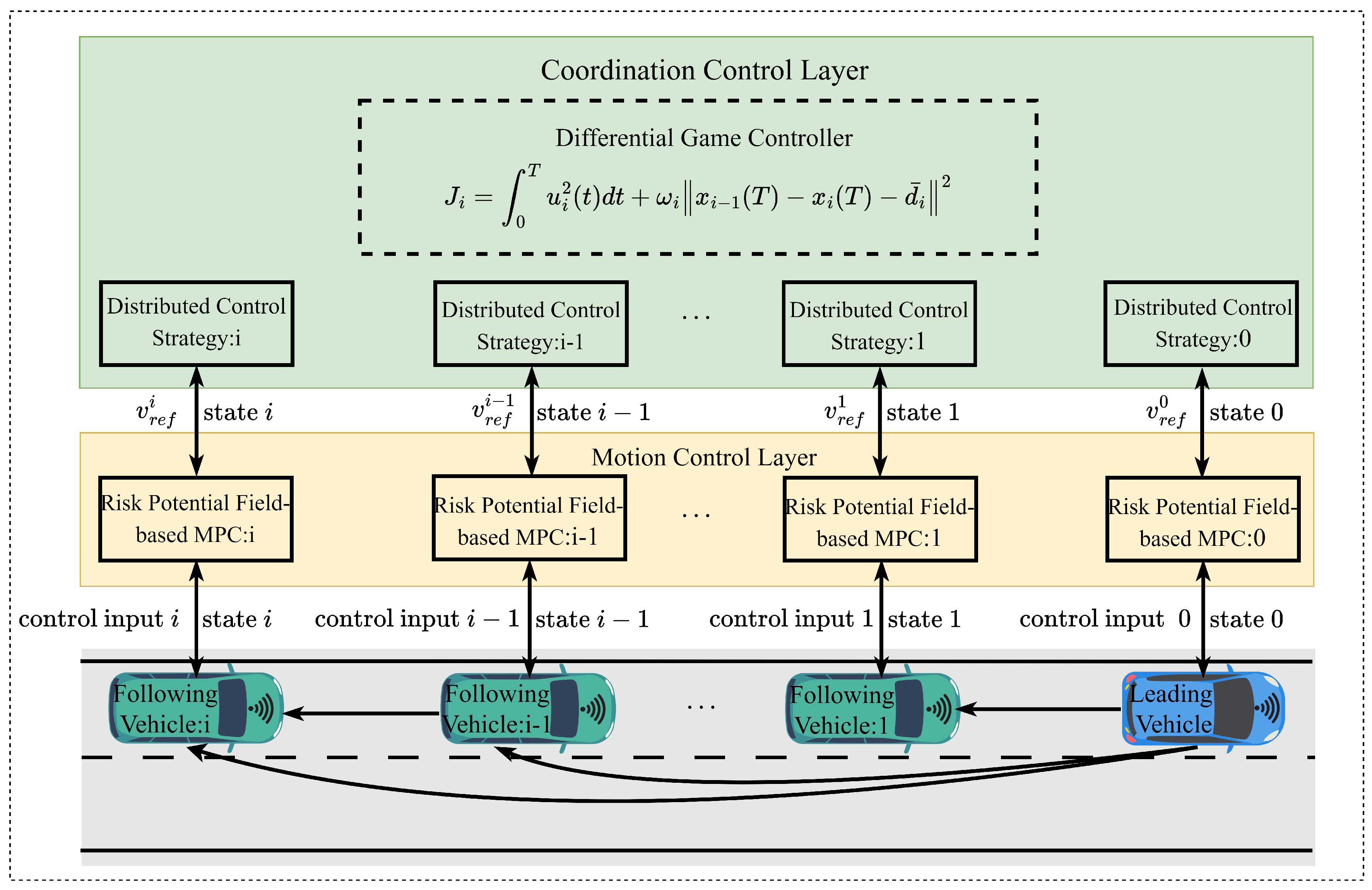

2. Hierarchical Cooperative Control Framework

3. Differential Game-Based Longitudinal Controller

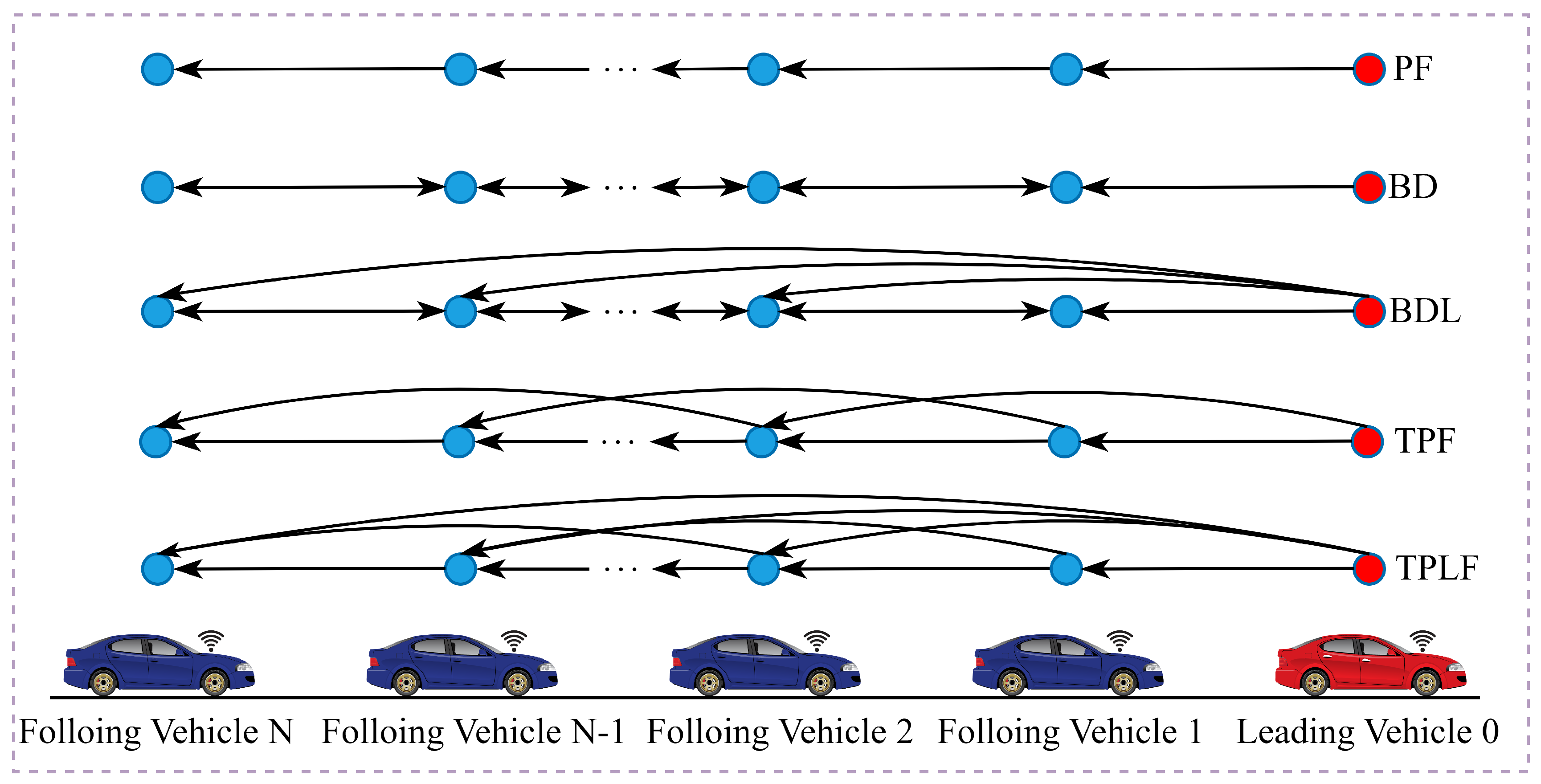

3.1. CAV Communication Topology

3.2. Longitudinal Vehicle Dynamics Modeling for CAV Platoons

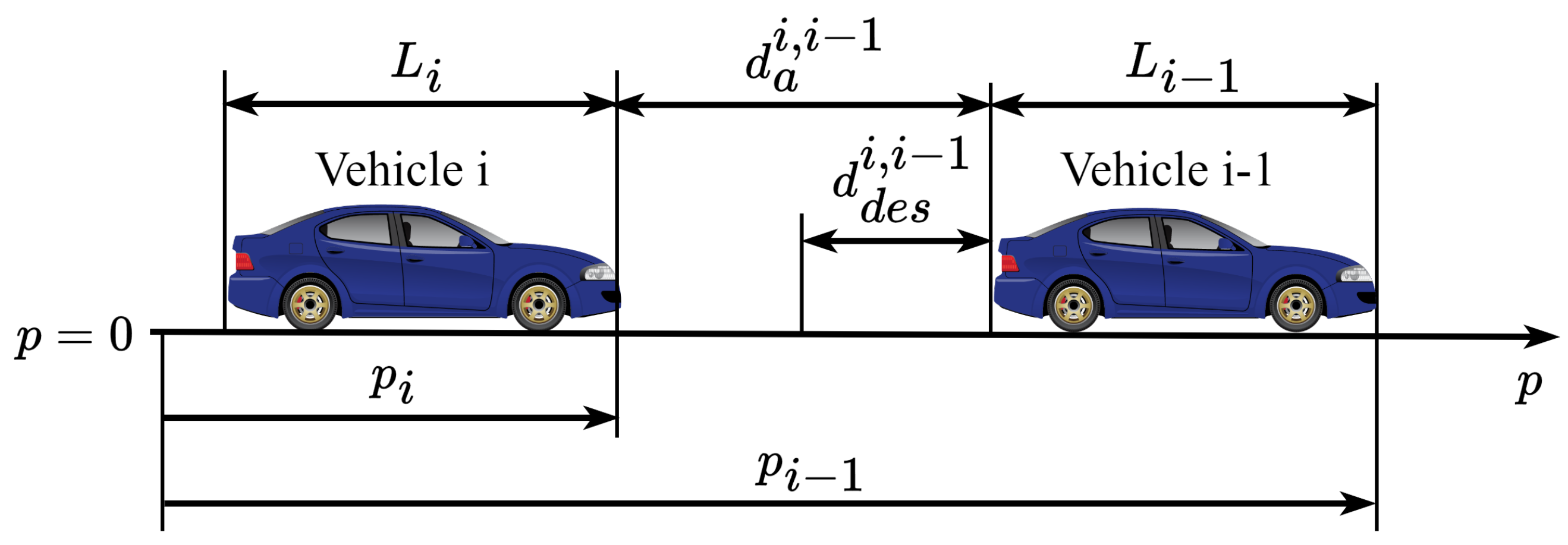

3.3. Inter-Vehicle Spacing Policy for CAV Platoons

3.4. Differential Game-Based Longitudinal Control Strategy for CAV Platoons

3.4.1. Open-Loop Nash Equilibrium of the Differential Game

3.4.2. Estimated Open-Loop Nash Equilibrium of the Differential Game

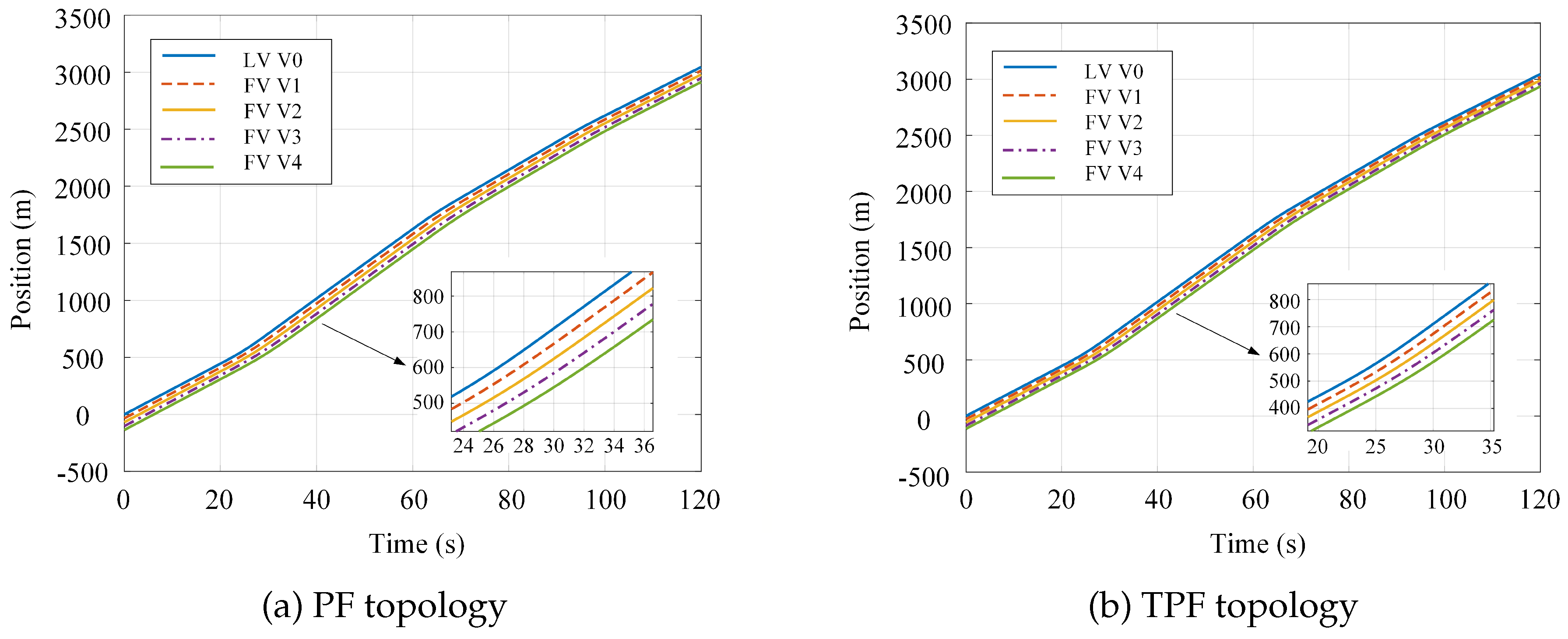

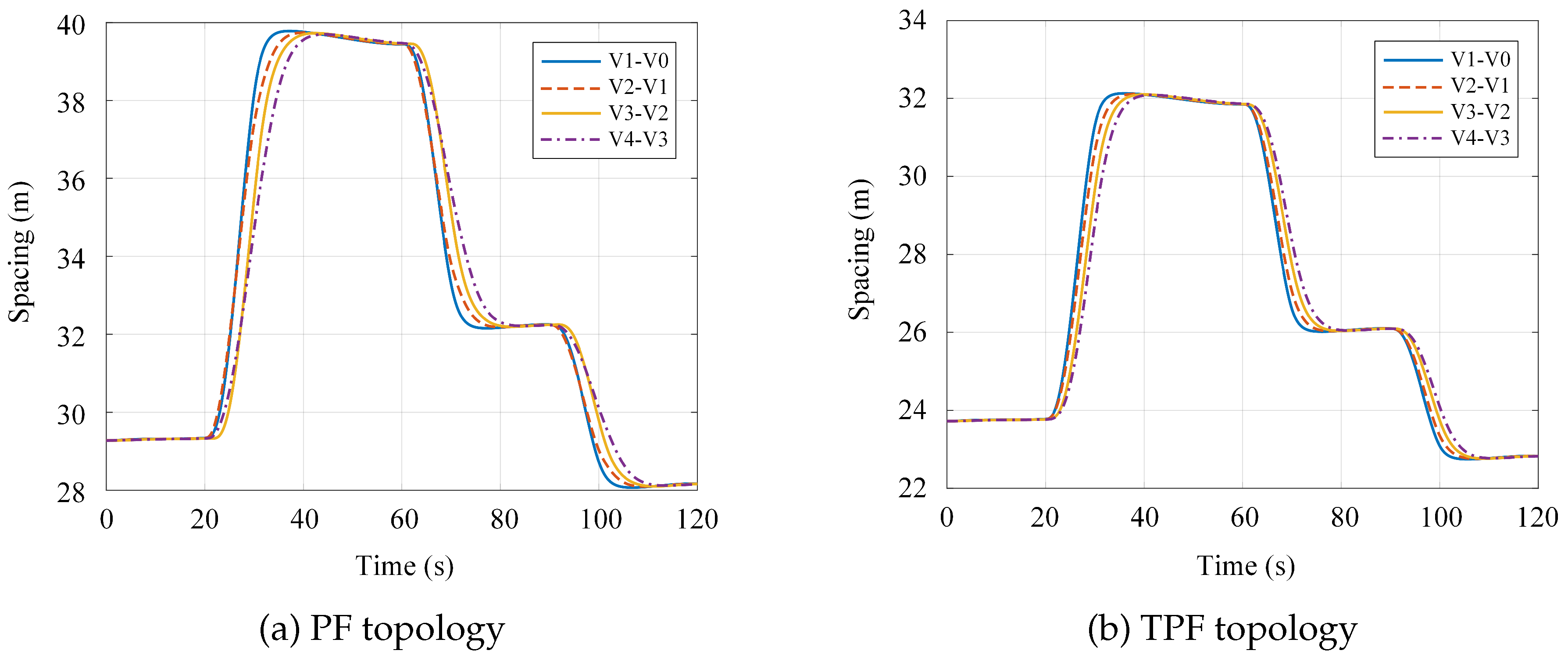

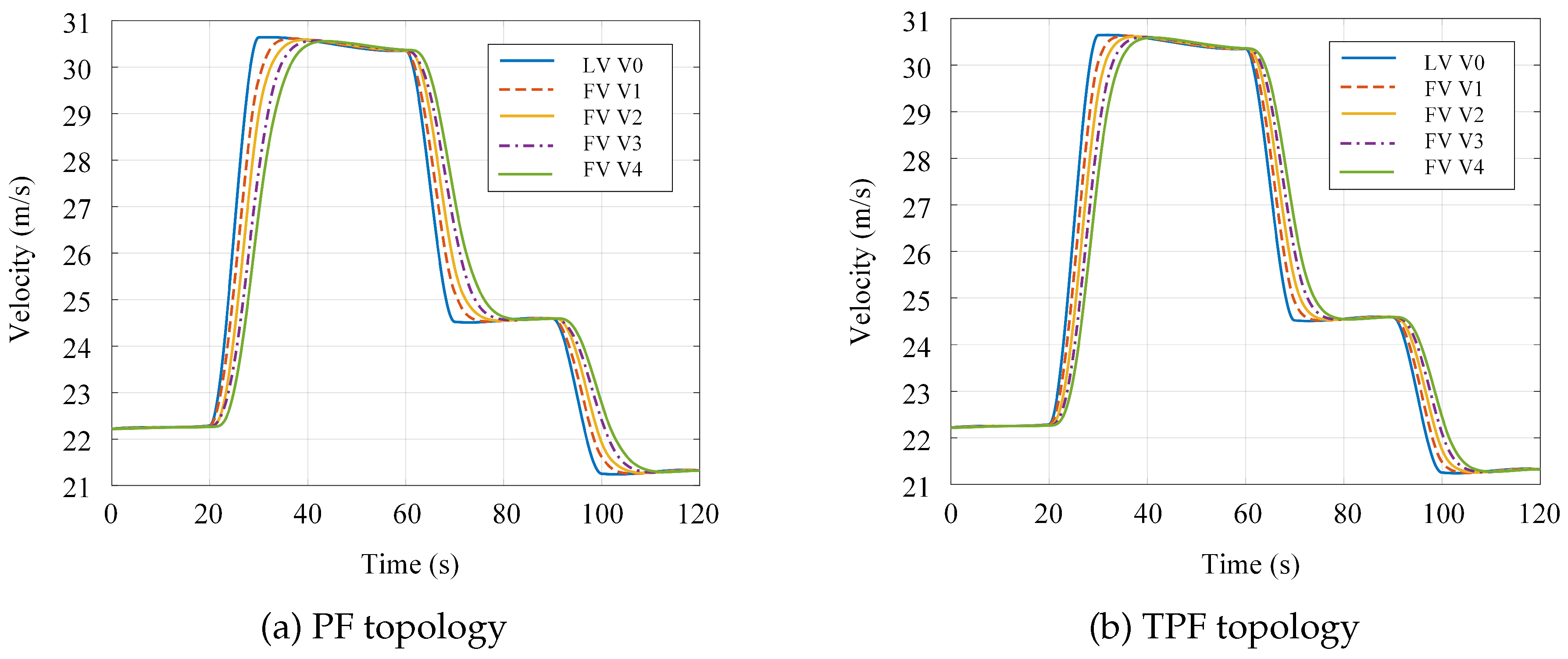

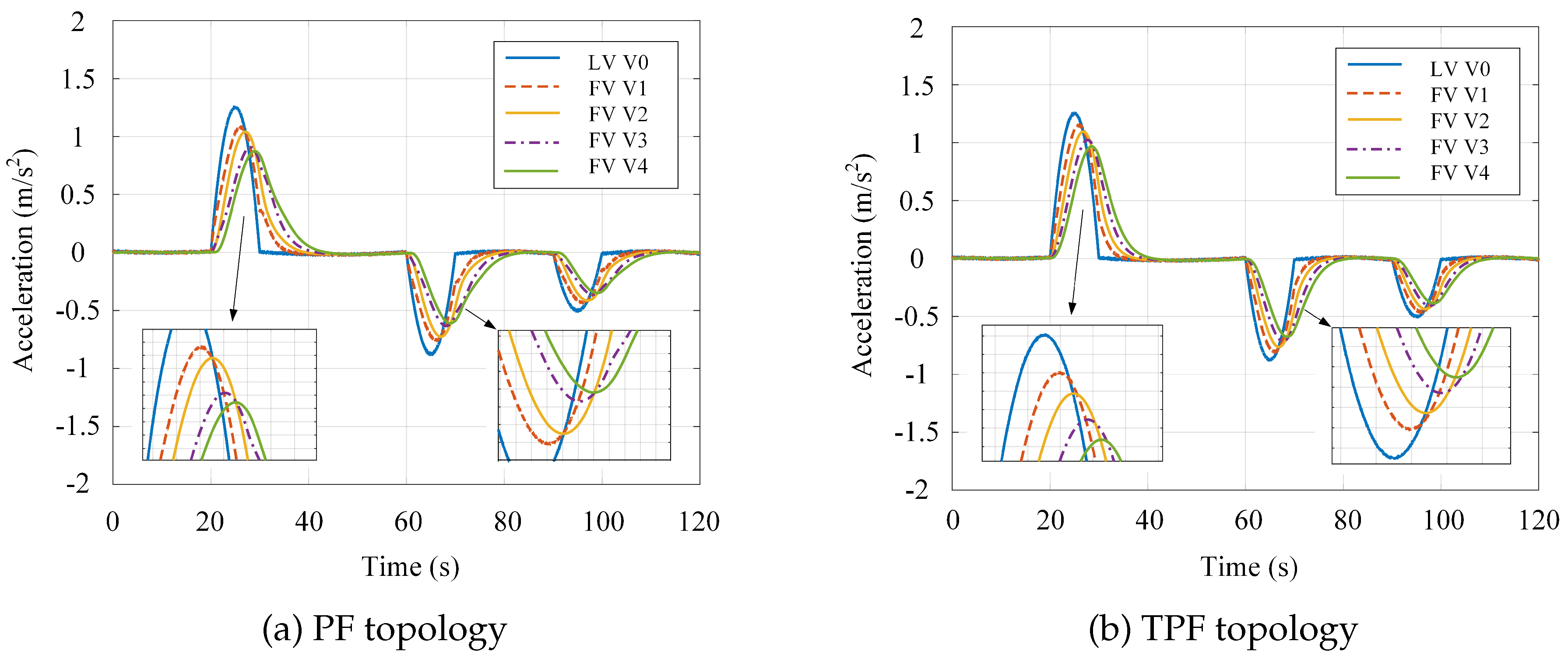

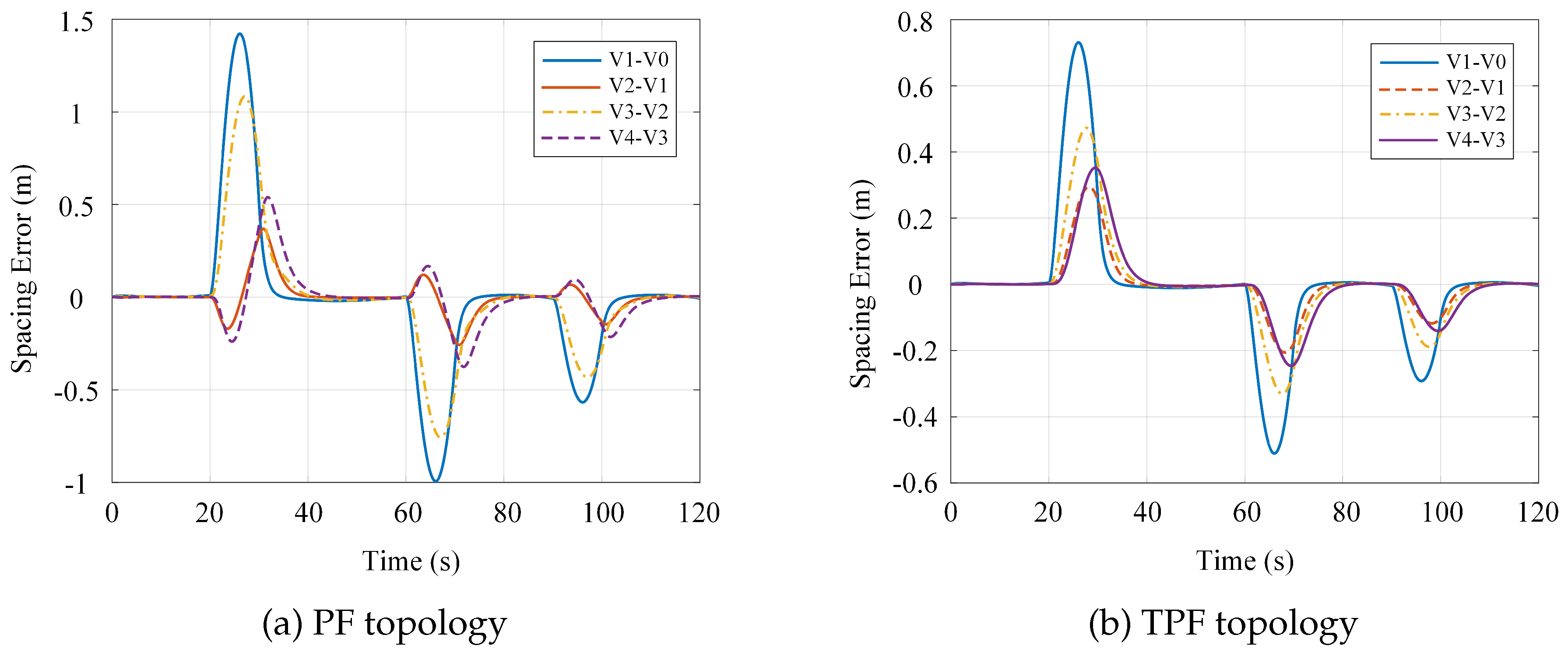

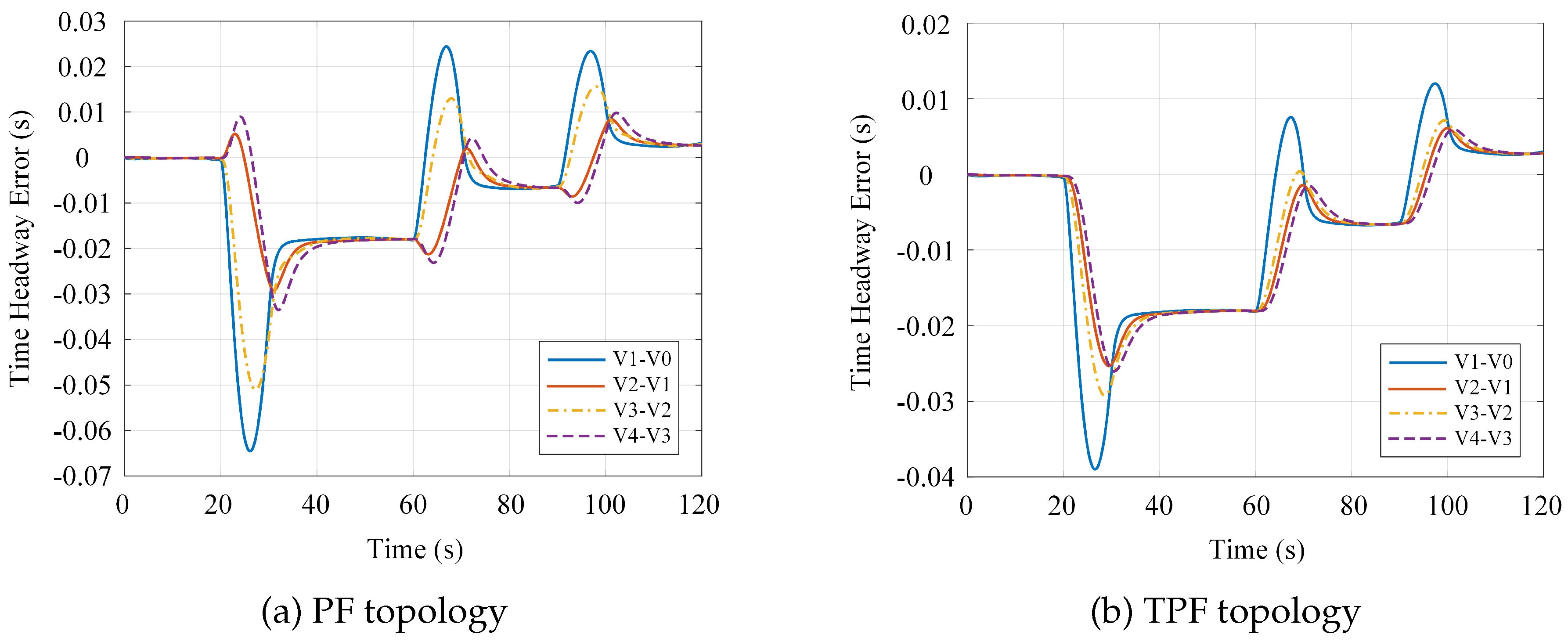

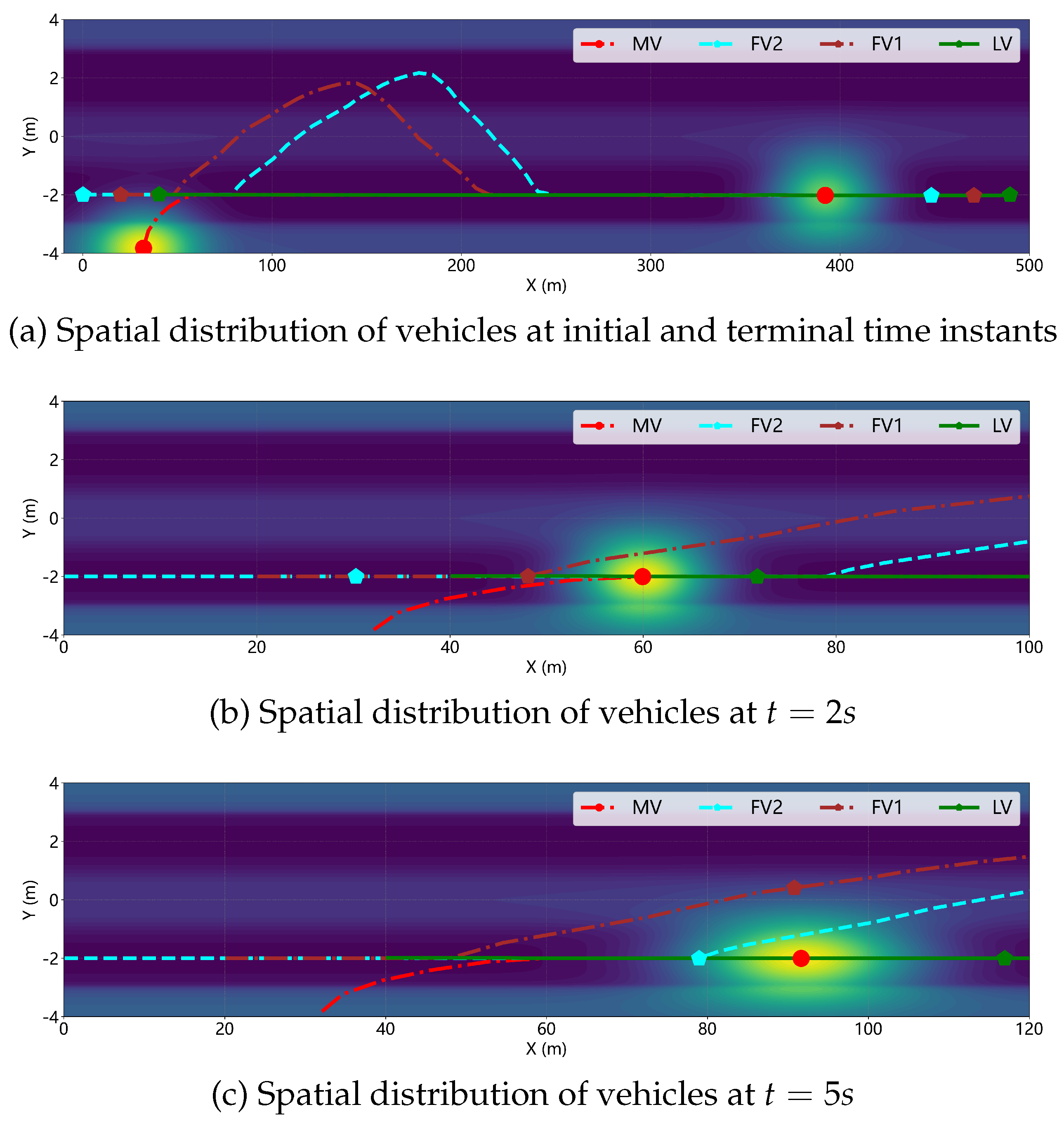

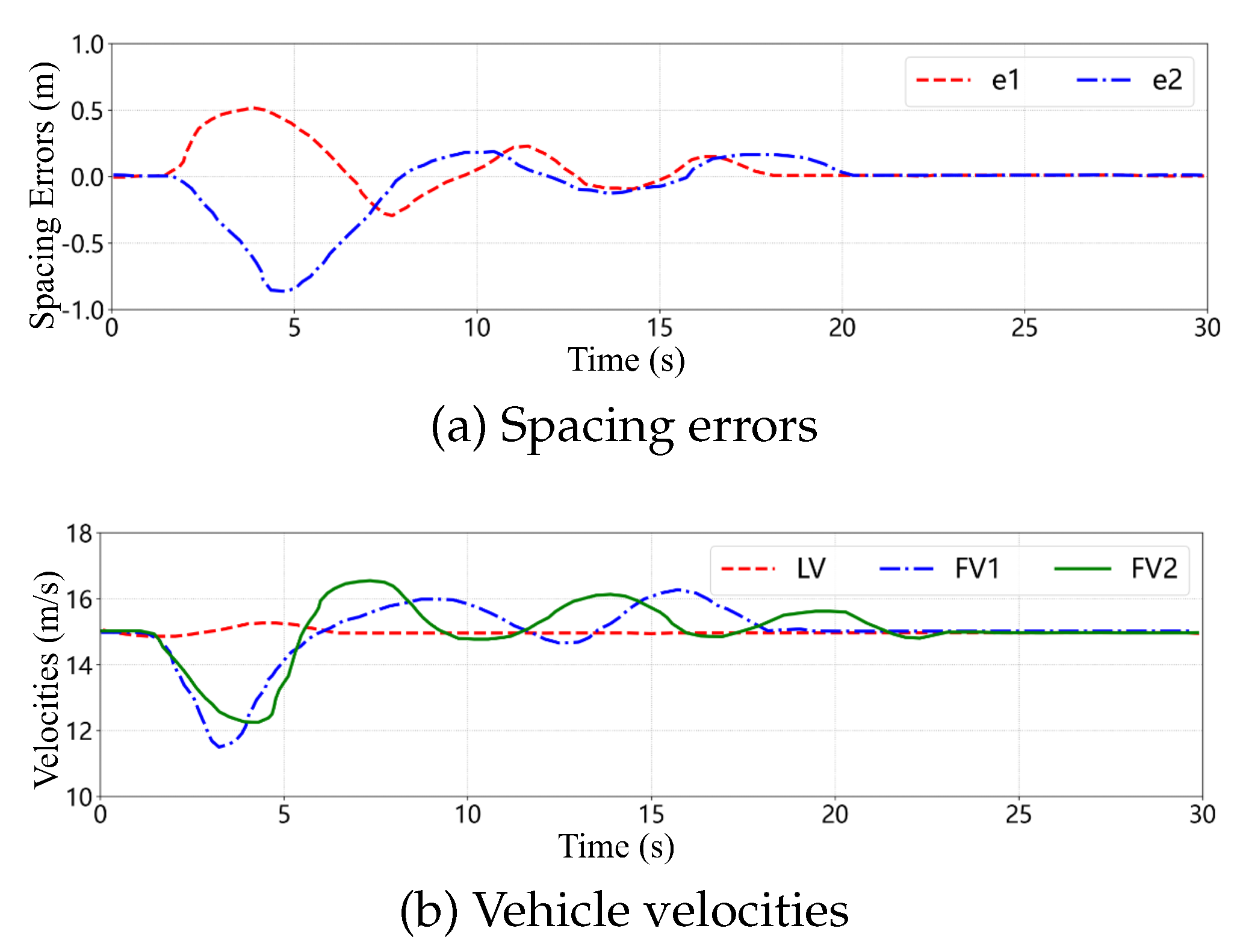

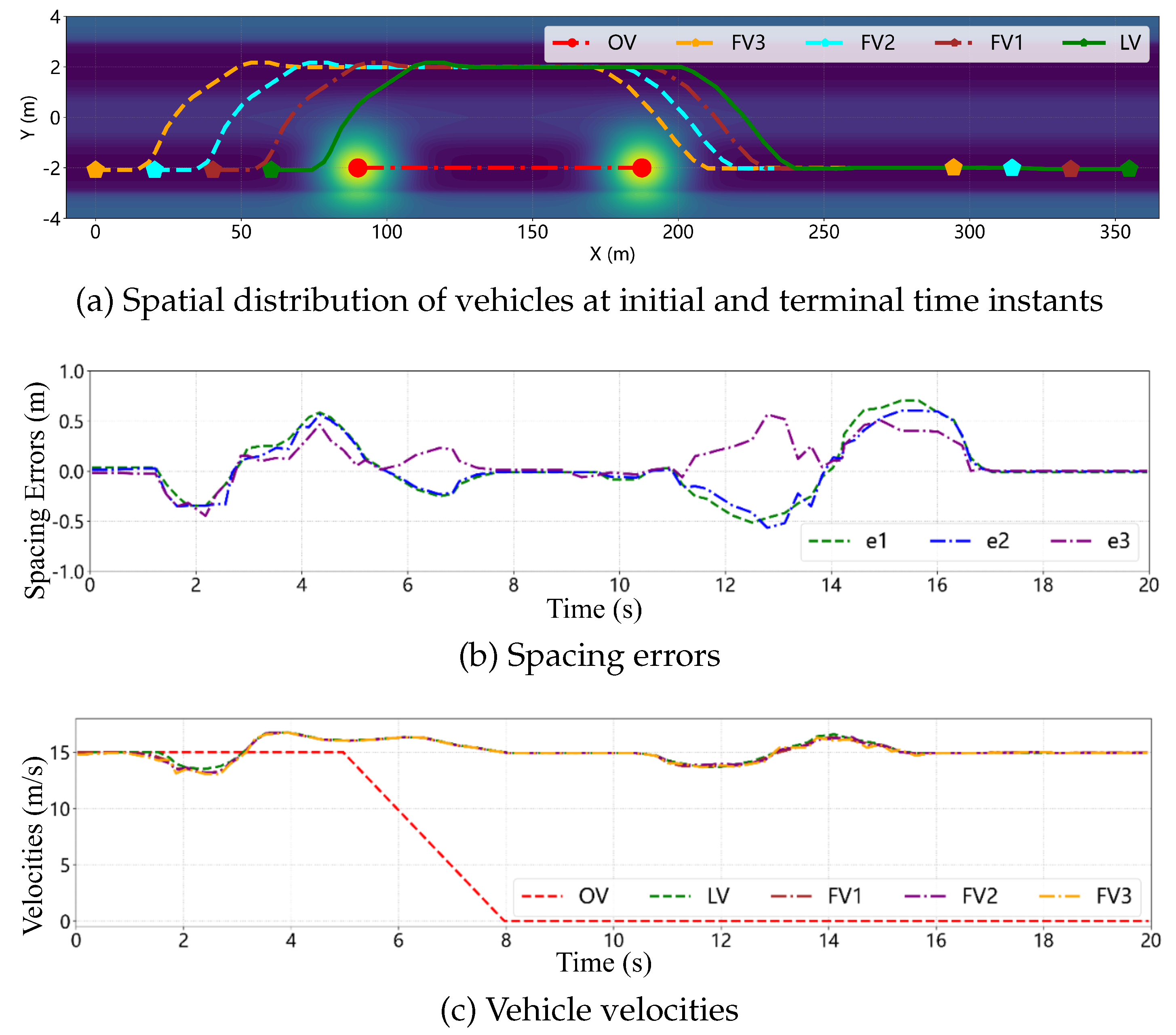

3.4.3. Simulation Validation of the Differential Game-Based Control Strategy

4. Risk Potential Field-Based MPC Lateral Controller

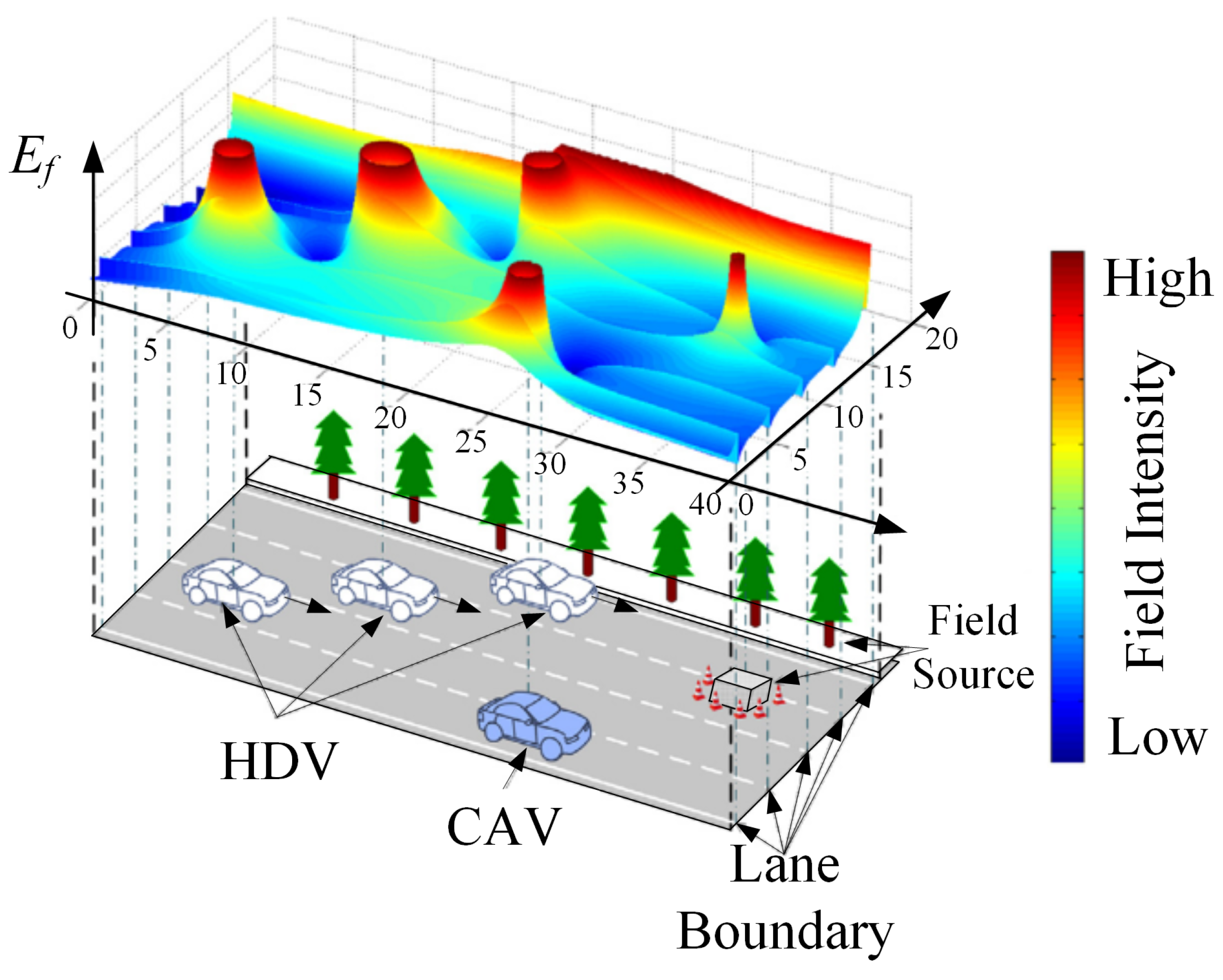

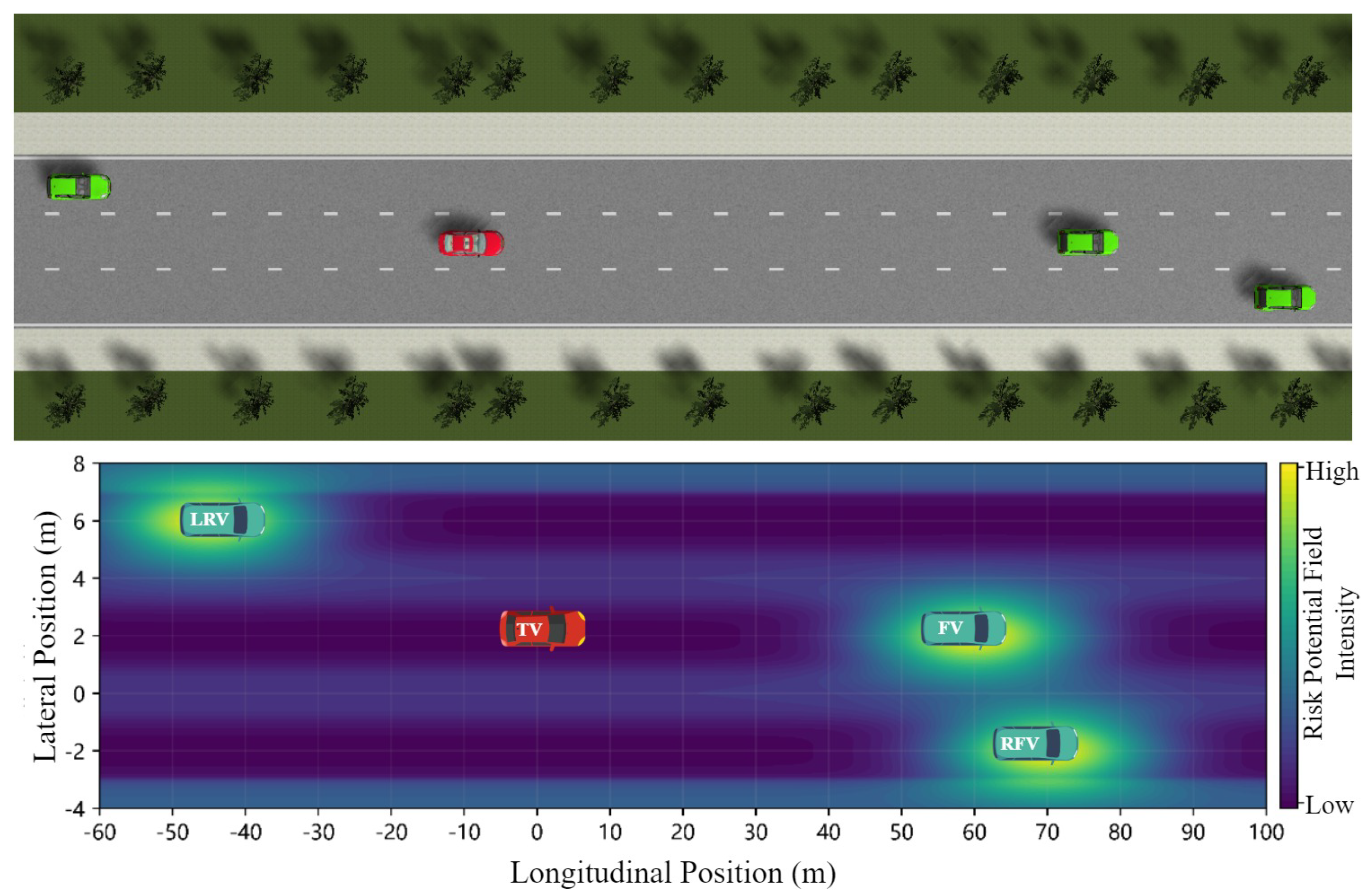

4.1. Risk Potential Field Modeling

4.2. Risk Potential Field-Based MPC Lateral Control Strategy for CAV Platoons

5. Co-Simulation Platform and Experimental Validation

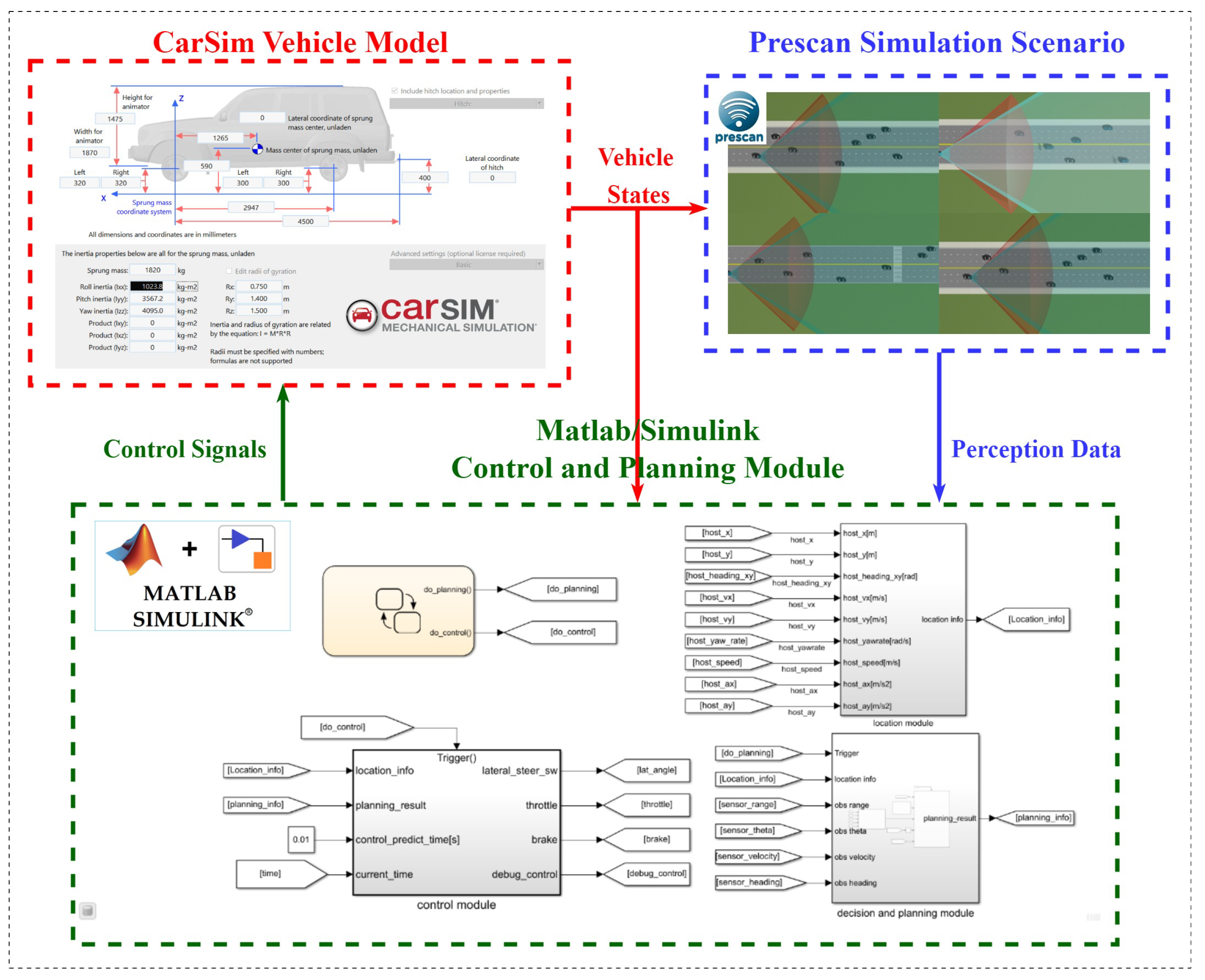

5.1. Co-Simulation Platform Architecture

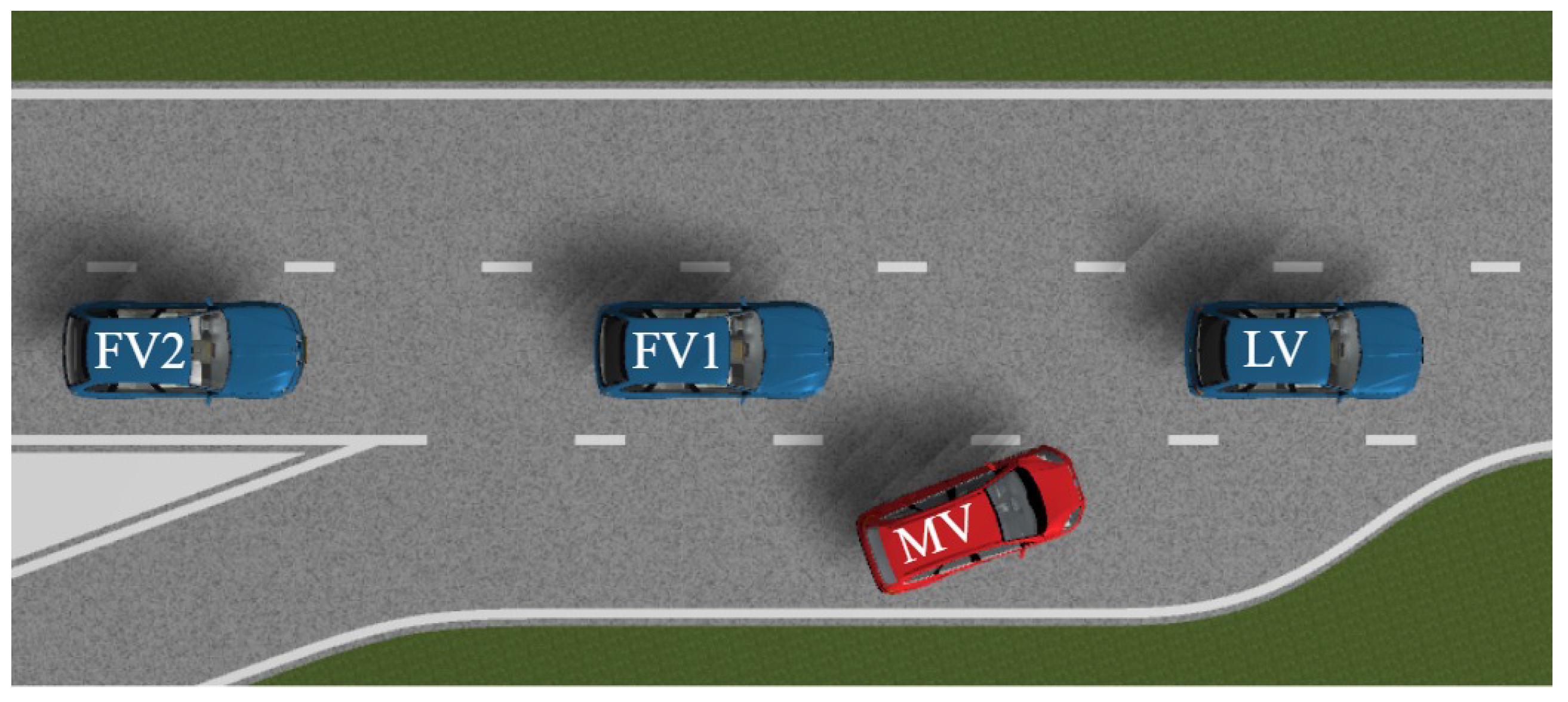

5.2. Ramp Merging Scenario

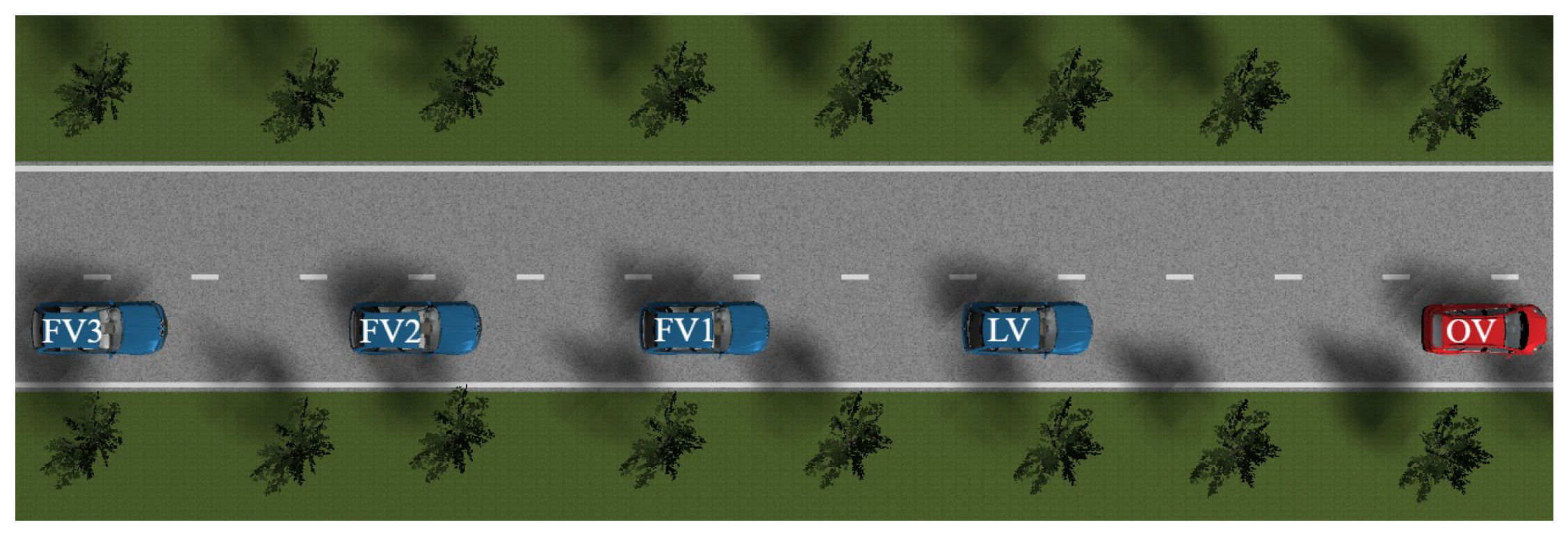

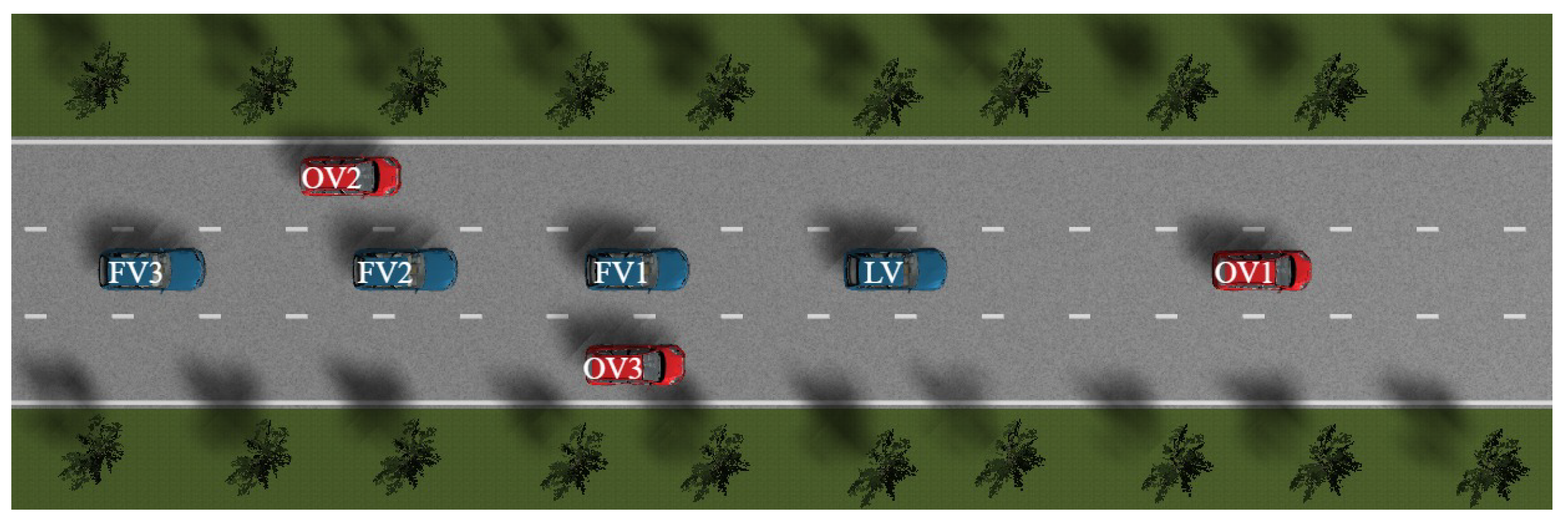

5.3. Emergency Braking Scenario of Obstacle Vehicle

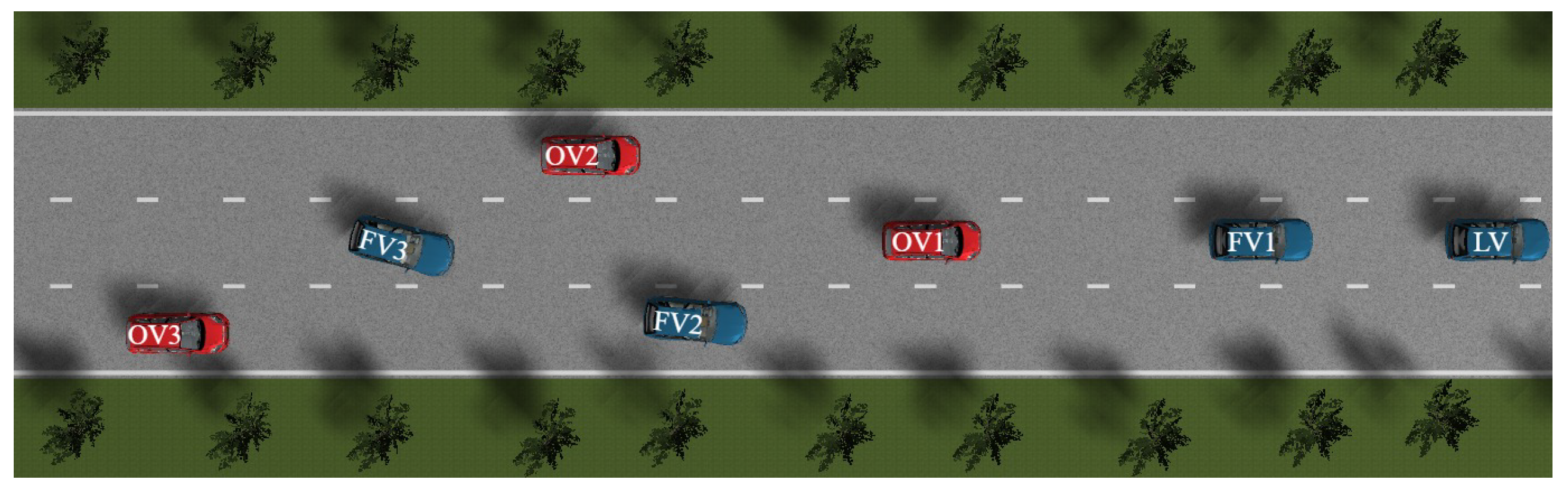

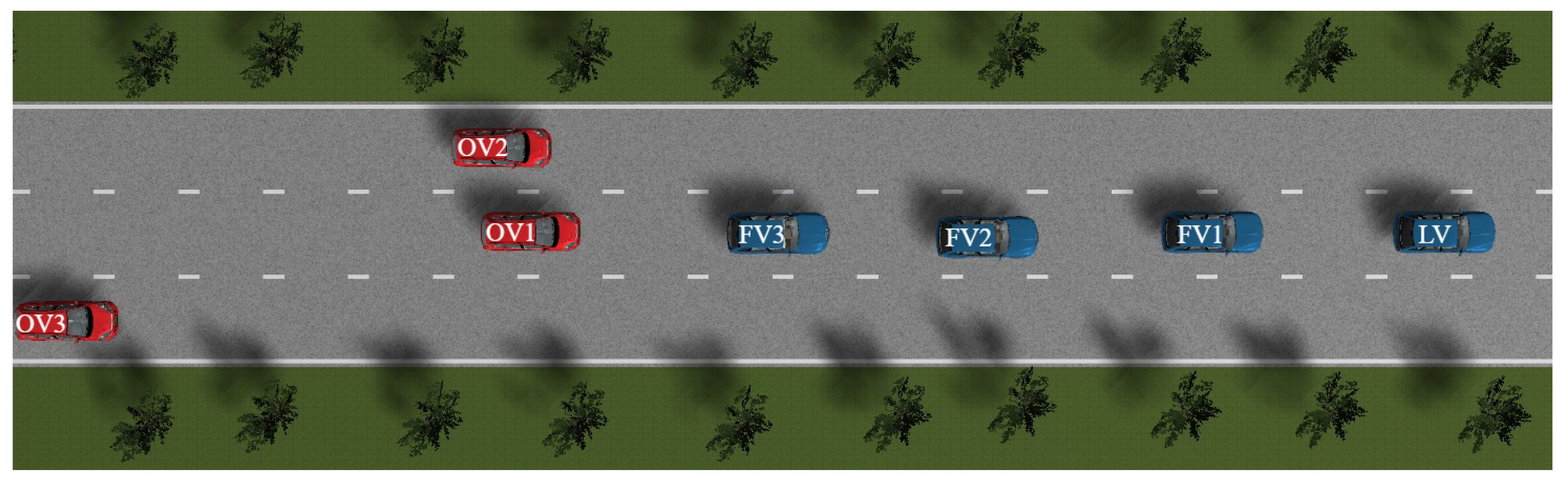

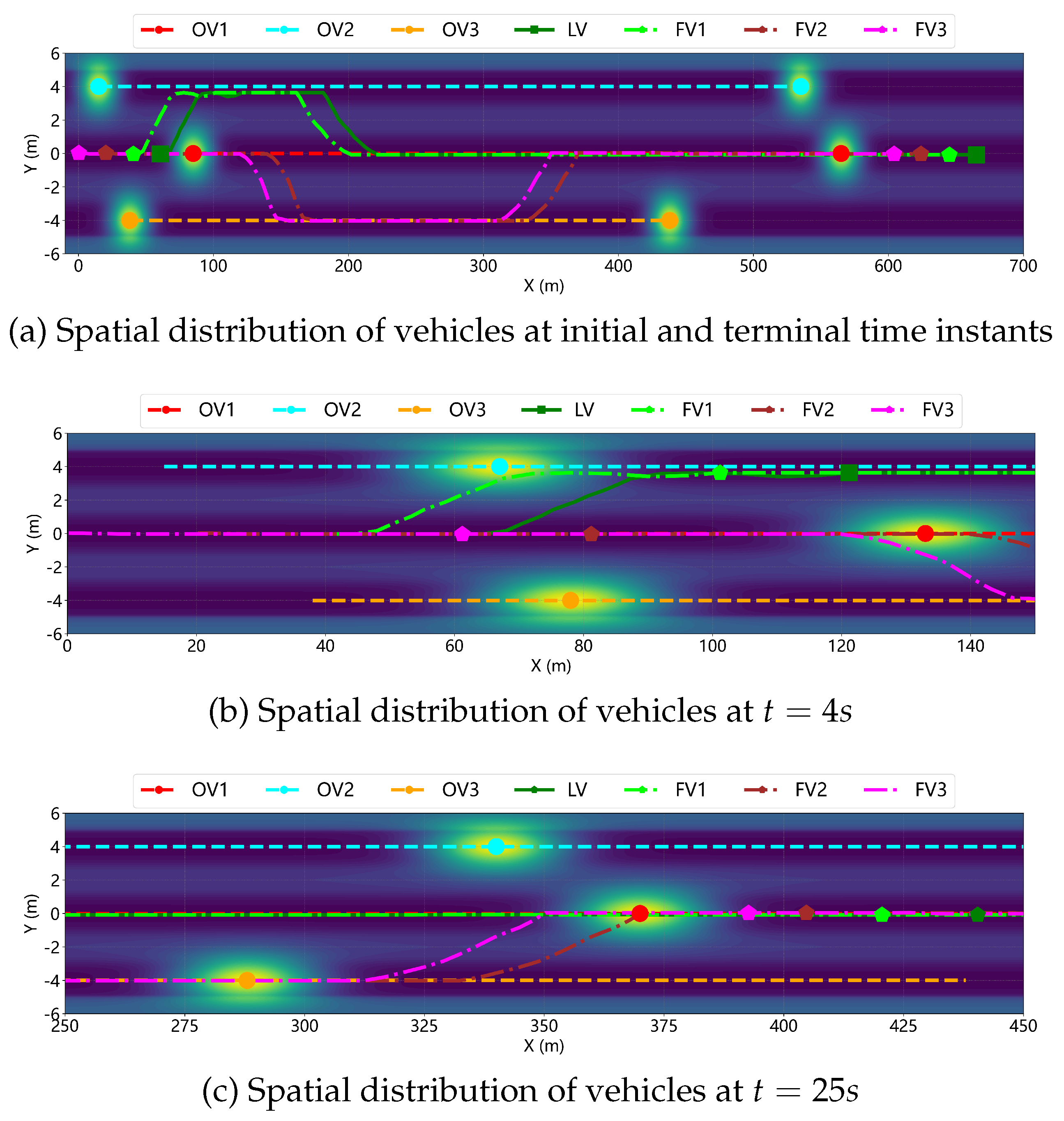

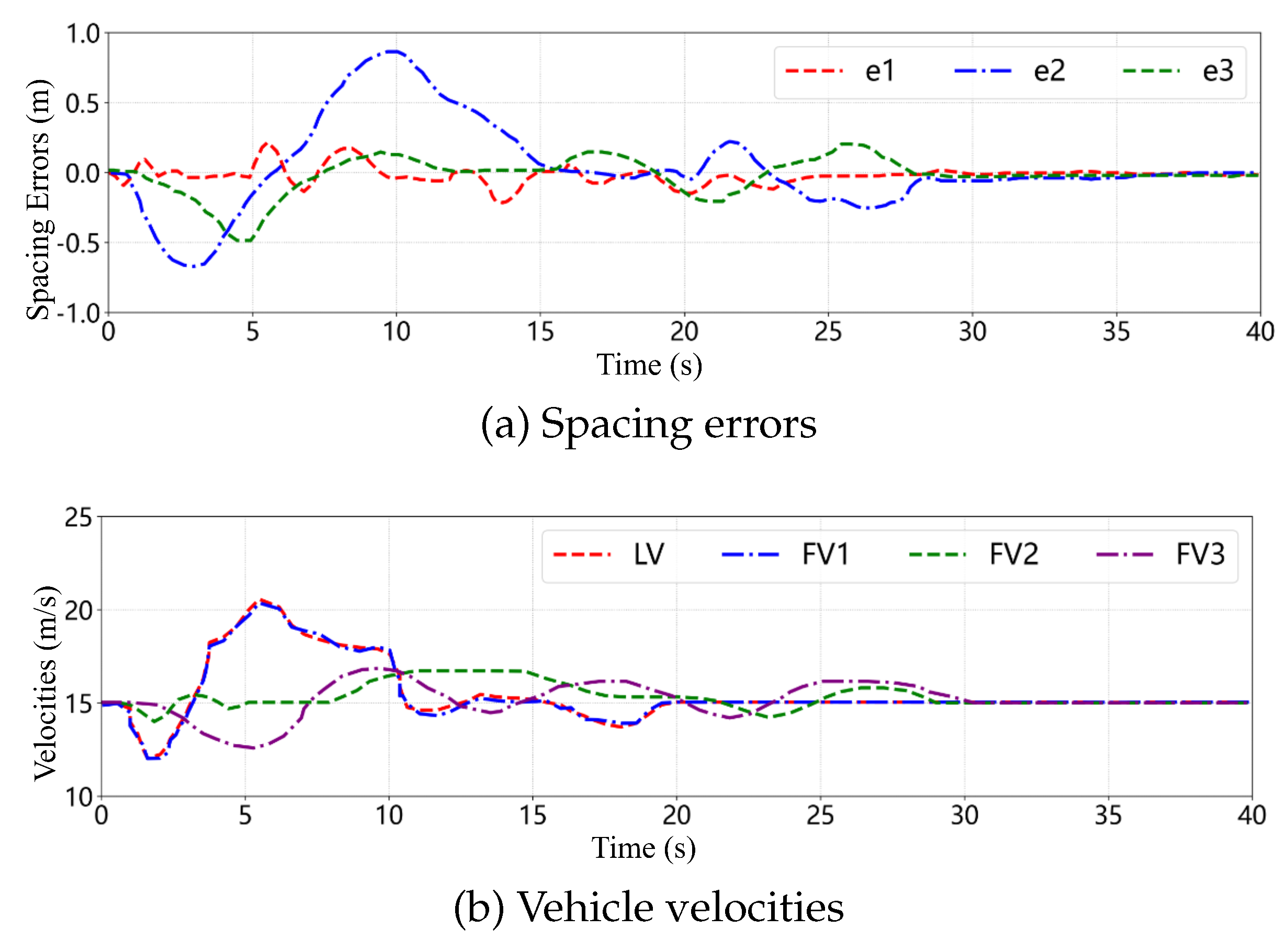

5.4. Multi-Lane Cooperative Obstacle Avoidance Scenario

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, K.; Shen, C.; Li, X.; Lu, J. Uncertainty quantification for safe and reliable autonomous vehicles: A review of methods and applications. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garikapati, D.; Shetiya, S.S. Autonomous vehicles: Evolution of artificial intelligence and the current industry landscape. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, L.; Xia, C.; Olson, D.L. The impacts of connected autonomous vehicles on mixed traffic flow: A comprehensive review. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2024, 635, 129454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Liu, X. Research on World Models for Connected Automated Driving: Advances, Challenges, and Outlook. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 8986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Bouroche, M. Longitudinal Car-Following Control of Connected Autonomous Vehicles in Realistic Scenarios: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, W.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y. Vehicle platoon in road traffic: A Survey of Modeling, Communication, Controlling and Perspectives. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2025, 130757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Yang, K.; Hashemi, E.; Wang, H. Longitudinal and lateral control methods from single vehicle to autonomous platoon. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2023, 2, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, L.M.; Wei, Z.; Yang, K.; Jiang, L.; Hashemi, E.; et al. A holistic robust motion control framework for autonomous platooning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 15213–15226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.; Qi, X.; Chen, D.; Jiang, K.; Liu, Z.E.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, H. Multi-agent reinforcement learning for connected and automated vehicles control: Recent advancements and future prospects. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, M.; Rafael, S.; Bandeira, J.M. Vehicle platooning: A detailed literature review on environmental impacts and future research directions. Future Transportation 2024, 4, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braiteh, F.E.; Bassi, F.; Khatoun, R. Platooning in connected vehicles: a review of current solutions, standardization activities, cybersecurity, and research opportunities. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gong, S.; Zhou, A.; Li, T.; Peeta, S. Cooperative adaptive cruise control for connected autonomous vehicles by factoring communication-related constraints. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2020, 113, 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.T.; Zhuang, Y.L.; Zhu, W.X. Traffic flow bifurcation control of autonomous vehicles through a hybrid control strategy combining multi-step prediction and memory mechanism with PID. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation 2024, 137, 108136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Meng, Y.; Wang, F.Y.; Wu, D. Interval type-2 fuzzy hierarchical adaptive cruise following-control for intelligent vehicles. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2022, 9, 1658–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turri, V.; Besselink, B.; Johansson, K.H. Cooperative look-ahead control for fuel-efficient and safe heavy-duty vehicle platooning. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2016, 25, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Pant, Y.V. Improving safety in mixed traffic: A learning-based model predictive control for autonomous and human-driven vehicle platooning. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 293, 111673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Chen, J.; Zhao, F.; Chen, X.; Xuan, L. Research on Fast Stochastic Model Predictive Control-Based Eco-Driving Strategy for Connected Mixed Platoons. Automotive Engineering 2024, 46, 1587–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Wang, H.; Pi, D.; Sun, X.; Wang, X. Research on collaborative adaptive cruise control based on MPC and improved spacing policy. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering 2025, 239, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, F.; Huang, L.; Yu, S.; Shi, S. Longitudinal Control of Connected Vehicle Platoon based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Control and Decision 2024, 39, 1879–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Min, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Fang, Y.; Song, X. Deep deterministic policy gradient based cooperative platoon longitudinal control strategy. Journal of Chang’an University(Natural Science Edition) 2021, 41, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Lv, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W. Collaborative control of vehicle platoon based on deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024, 73, 14399–14414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, J.; Han, J.; Chen, Z. Personalized car-following control based on a hybrid of reinforcement learning and supervised learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 6014–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. Hybrid car following control for CAVs: Integrating linear feedback and deep reinforcement learning to stabilize mixed traffic. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2024, 167, 104773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Ran, B. Connected automated vehicle cooperative control with a deep reinforcement learning approach in a mixed traffic environment. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2021, 133, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafhalla, A.K.Y.; Elobaid, M.E.; Tayfour Ahmed, A.E.; Filali, A.; SidAhmed, N.M.O.; Attia, T.A.; Mohajir, B.A.I.; Altamimi, J.S.; Adam, T. Computer-Aided Efficient Routing and Reliable Protocol Optimization for Autonomous Vehicle Communication Networks. Computers 2025, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, U.; Ahanger, T.A. Enhancing Intelligent Transport Systems Through Decentralized Security Frameworks in Vehicle-to-Everything Networks. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2025, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, T.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Stability analysis and controller design of the Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control platoon considering a rate-free time-varying communication delay and uncertainties. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2025, 170, 104913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakerimanesh, A.; Qiu, T.Z.; Tavakoli, M. Stability and intervehicle distance analysis of vehicular platoons: Highlighting the impact of bidirectional communication topologies. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2024, 32, 1124–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.A.; Mozelli, L.A. Robust longitudinal control for vehicular platoons using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 25, 14401–14410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, A.; Lui, D.G.; Petrillo, A.; Santini, S. Cooperative driving of heterogeneous uncertain nonlinear connected and autonomous vehicles via distributed switching robust PID-like control. Information Sciences 2023, 625, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Qu, X.; Ran, B. Enhancing Vehicle Platoons in Connected and Automated Environments With an Improved Spectral Clustering-Based Pinning Control Strategy. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z. A Bidirectional Distance Balancing Strategy for Connected Automated Vehicles Platoon in Mixed Traffic Flow. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sun, Q.; Pan, Q. Robust Tracking Control of Underactuated UAVs Based on Zero-Sum Differential Games. Drones 2025, 9, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hu, S.; Yuan, F.; Yang, J. Game-Aware MPC-DDP for Mixed Traffic: Safe, Efficient, and Comfortable Interactive Driving. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2025, 16, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, G. Game-Theoretic Decision-Making for Autonomous Vehicles at Unsignalized Intersections under Communication Interferences: A Novel Risk-Adaptive Approach. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhuang, W.; Yin, G.; Chen, B. A Game-Theoretical Framework for Safe Decision Making and Control of Mixed Autonomy Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Ye, X. A Distributed Game-Based Traffic Control Model for Unsignalized Intersections in a Connected Vehicle Environment. Transportation Research Record 2025, 03611981251382910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jond, H.B.; Platoš, J. Differential game-based optimal control of autonomous vehicle convoy. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 24, 2903–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.; Jond, H.B. Vehicle swarm platooning as differential game. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR); IEEE, 2021; pp. 885–890. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Shi, J.; Zhuang, W.; Li, Z.; Song, Z. Analyzing the impact of mixed vehicle platoon formations on vehicle energy and traffic efficiencies. Applied Energy 2025, 377, 124448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhu, J.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, Y. Multi-vehicle dynamic interaction in autonomous driving: integrating game theory and the potential field method. Transportmetrica B: Transport Dynamics 2025, 13, 2425969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Qu, D.; Song, H.; Wang, T.; Zhao, Z. Car-following characteristics and model of connected autonomous vehicles based on safe potential field. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2022, 586, 126502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Qu, D.; Wang, K.; Wei, C.; Li, A. Risk-Aware Lane Change and Trajectory Planning for Connected Autonomous Vehicles Based on a Potential Field Model. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Cao, D.; Wang, Z. Integrated decision making and motion control for autonomous emergency avoidance based on driving primitives transition. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 72, 4207–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, G.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y.; Feng, J.; Shen, T.; Cai, G. A MAS-based hierarchical architecture for the cooperation control of connected and automated vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 72, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Chakraborty, S.; Ozbay, K.; Jiang, Z.P. Data-Driven Combined Longitudinal and Lateral Control for the Car Following Problem. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasekhipour, Y.; Fadakar, I.; Khajepour, A. Autonomous driving motion planning with obstacles prioritization using lexicographic optimization. Control Engineering Practice 2018, 77, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Khajepour, A.; Zhang, Y.; Rasekhipour, Y.; Cao, D. Crash mitigation in motion planning for autonomous vehicles. IEEE transactions on intelligent transportation systems 2019, 20, 3313–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Liu, M.; Xiong, H.; Sio, K.; Long, Z.; Bu, X. Integrated Motion Control for Autonomous Vehicles Operating under Nonlinear Disturbances. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2025, 116264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, N.P.; Khajepour, A.; Hashemi, E. MPC-PF: Socially and spatially aware object trajectory prediction for autonomous driving systems using potential fields. IEEE transactions on intelligent transportation systems 2023, 24, 5351–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, P.; Pant, A.; Hedrick, K. Disturbance propagation in vehicle strings. IEEE Transactions on automatic control 2004, 49, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vehicle Type | PF Topology | TPF Topology |

|---|---|---|

| Leader v0 | ||

| Follower v1 | ||

| Follower v2 | ||

| Follower v3 | ||

| Follower v4 |

| Parameter Name | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Dynamics Parameters | ||

| Vehicle mass (kg) | m | 1500 |

| Yaw moment of inertia (kg·m2) | 2500 | |

| Distance from CG to front axle (m) | 1.2 | |

| Distance from CG to rear axle (m) | 1.6 | |

| Front tire cornering stiffness (N/rad) | ||

| Rear tire cornering stiffness (N/rad) | ||

| Vehicle length (m) | L | 4.5 |

| Powertrain time constant (s) | 0.65 | |

| Spacing Policy Parameters | ||

| Standstill spacing (m) | r | 5.0 |

| Time headway (s) | h | 1.2 |

| Risk Potential Field Parameters | ||

| Potential well depth | 1.0 | |

| Potential field steepness coefficient | 0.5 | |

| Minimum standstill spacing (m) | 2.0 | |

| CAV response time delay (s) | 0.1 | |

| Safety distance adjustment coefficient | 0.8 | |

| Maximum comfortable deceleration (m/s2) | 4.0 | |

| Lane line intensity gain | 50 | |

| Road boundary intensity gain | 200 | |

| Lane line attenuation coefficient | 0.8 | |

| Boundary attenuation coefficient | 0.5 | |

| Longitudinal correction coefficient | l | 2.0 |

| Lateral correction coefficient | w | 1.5 |

| Longitudinal velocity weighting factor | 0.1 | |

| Attenuation exponent | k | 2.0 |

| MPC Controller Parameters | ||

| Prediction horizon | 6 | |

| Control horizon | 3 | |

| Discretization time step (s) | T | 0.1 |

| State tracking weight | Q | diag(10, 1) |

| Control increment weight | R | 0.1 |

| Risk potential field weight | P | 5.0 |

| Slack variable weight | ||

| Constraint Parameters | ||

| Maximum longitudinal velocity (m/s) | 30 | |

| Minimum longitudinal velocity (m/s) | 0 | |

| Maximum steering angle (rad) | 0.5 | |

| Maximum steering rate (rad/s) | 0.3 | |

| Road adhesion coefficient | 0.85 | |

| Simulation Scenario Parameters | ||

| Desired cruising velocity (m/s) | 15 | |

| Initial inter-vehicle spacing (m) | 20 | |

| Lane width (m) | – | 3.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).