Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. DNA Extraction, 16s Amplicon PCR, and Sequencing

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.4. Taxa Abundance Analysis

2.5. Diversity

2.6. Pathway’s Inference

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

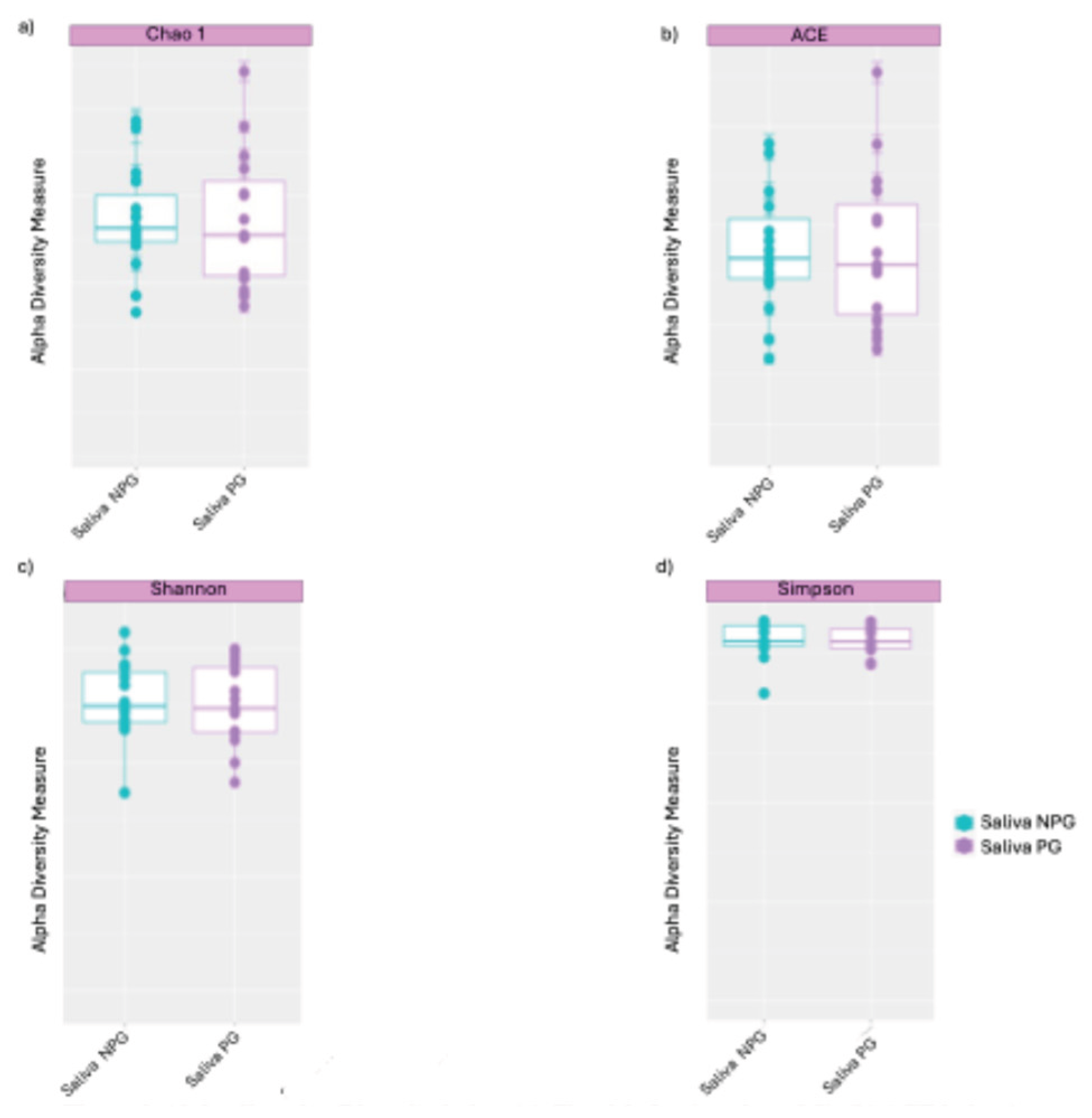

3.1. The Diversity Between the Two Groups

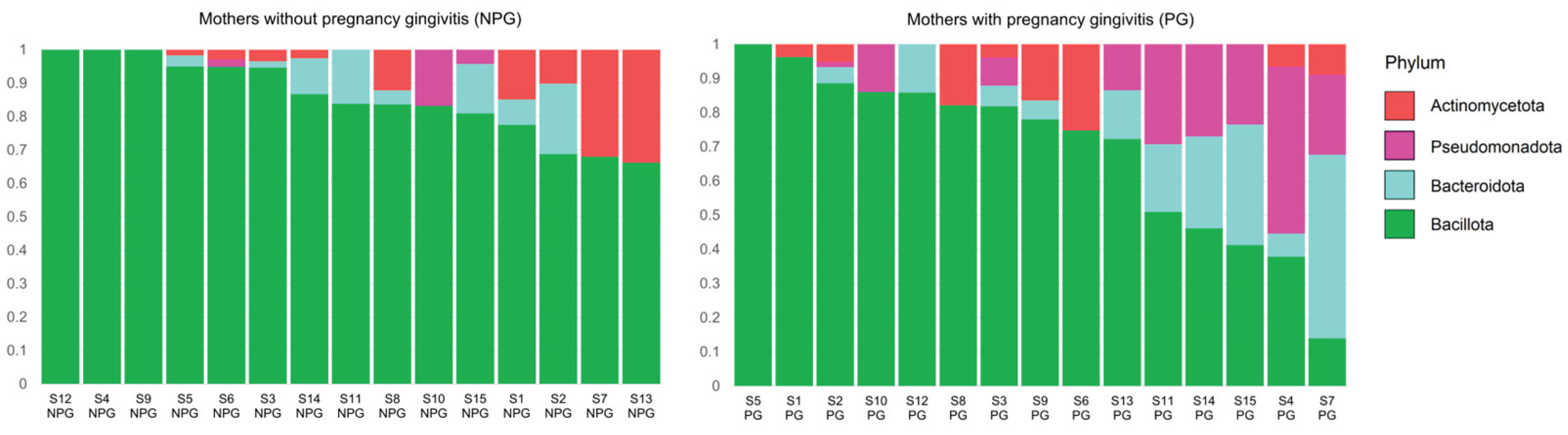

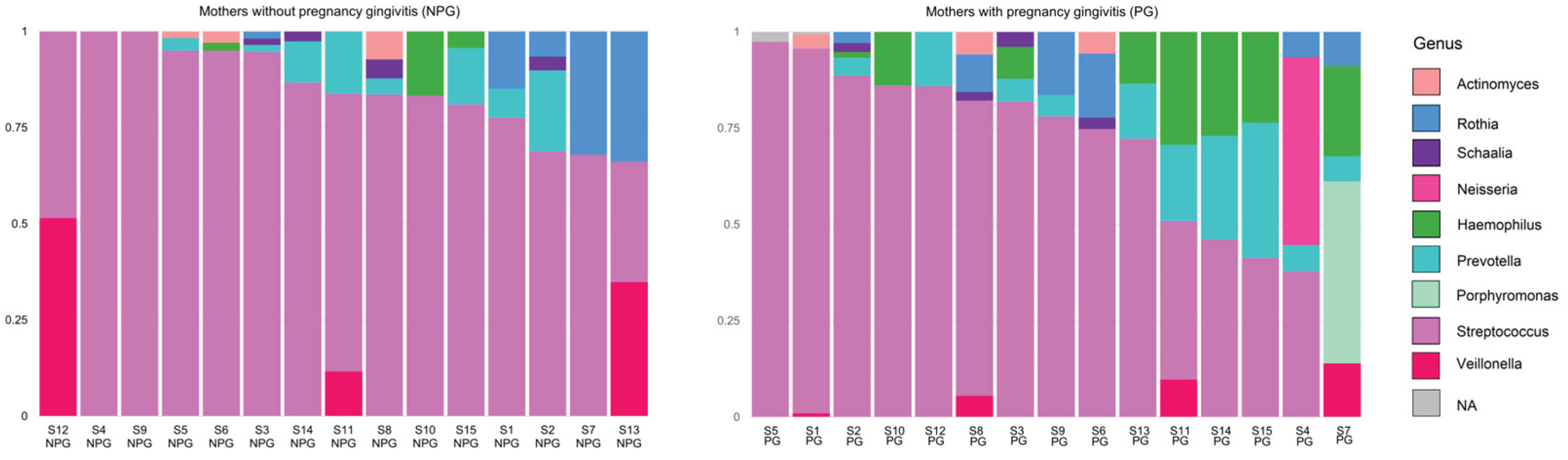

3.2. Relative Abundance of Bacteria at Phylum and Genus Level in Saliva Samples from Mothers

3.3. Relative Abundance of Bacteria at Phylum and Genus Level in Newborn Samples

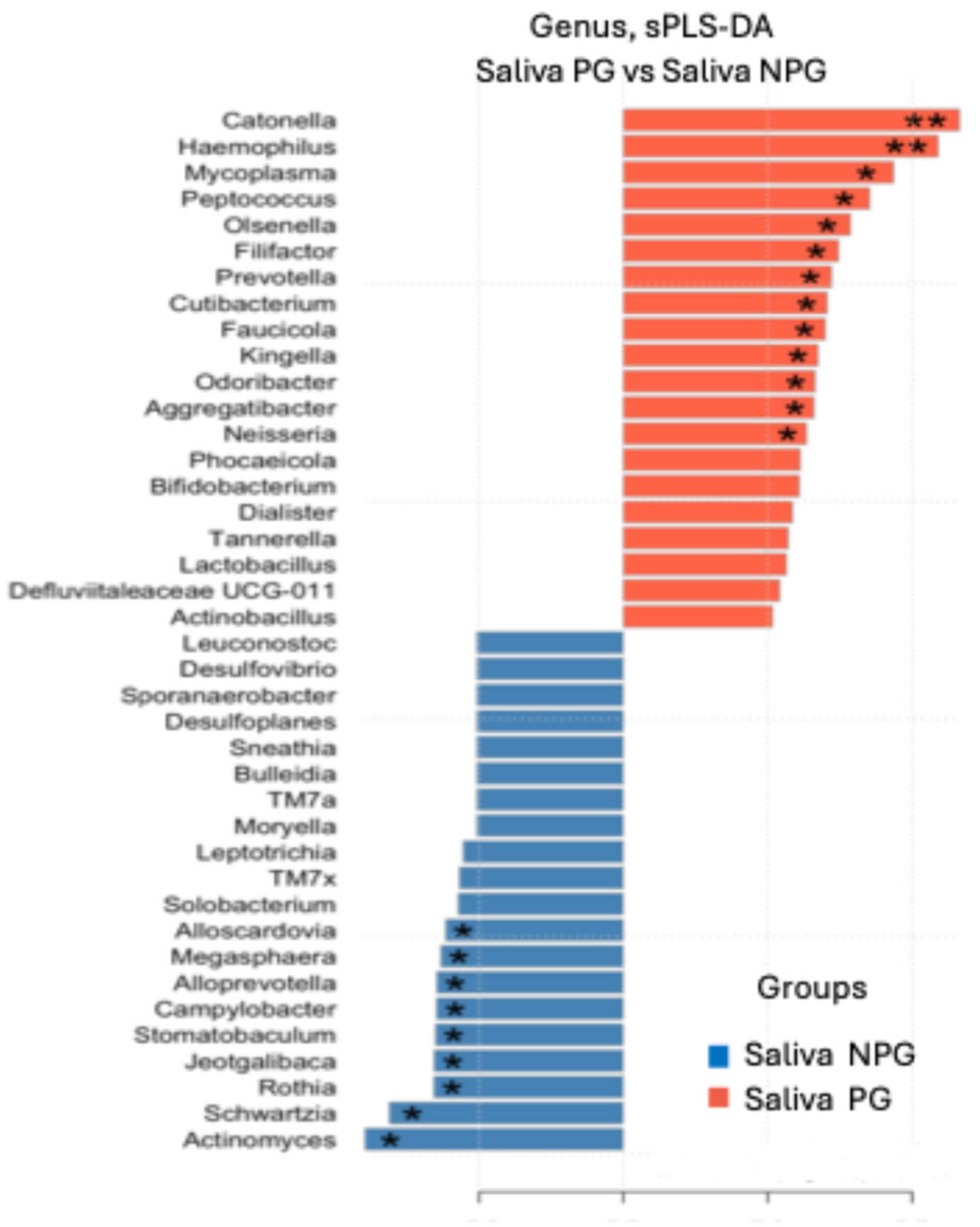

3.4. Differential Genera Were Found Between Groups

3.5. Phylum and Genera Coincidence Analysis by Study Group

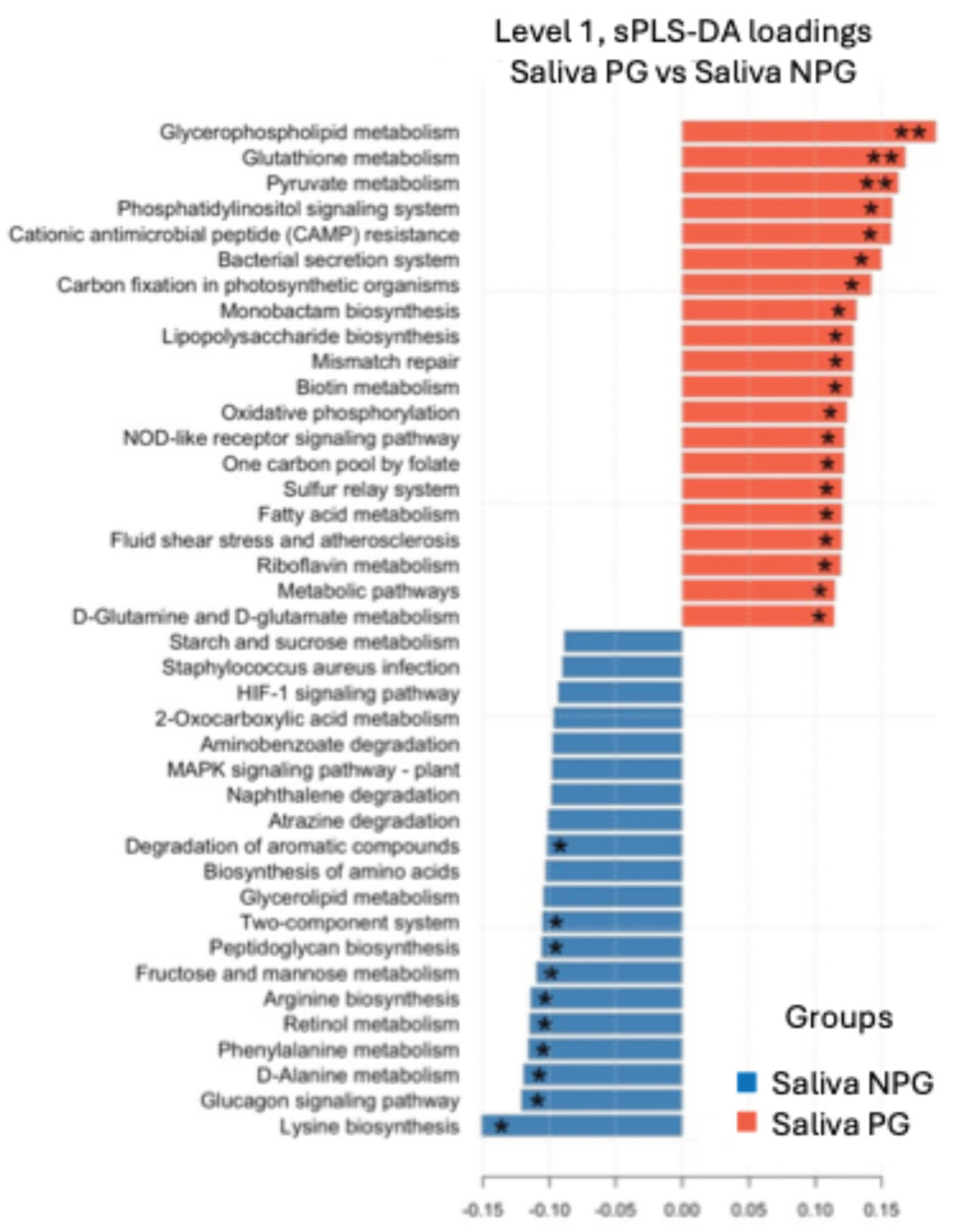

3.6. Metabolic Pathway Prediction

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stinson LF, Payne MS, Keelan JA. Planting the seed: Origins, composition, and postnatal health significance of the fetal gastrointestinal microbiota. Crit Rev Microbiol 2017;43:352–69. [CrossRef]

- Zakis DR, Paulissen E, Kornete L, Kaan AM (Marije), Nicu EA, Zaura E. The evidence for placental microbiome and its composition in healthy pregnancies: A systematic review. J Reprod Immunol 2022;149. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Viggiano AK, Aranda-Romo S, Salgado-Bustamante M, Ovando-Vázquez C. Meconium Microbiota Composition and Association with Birth Delivery Mode. Adv Gut Microbiome Res 2022;2022:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, Petrosino J, Versalovic J. The Placenta Harbors a Unique Microbiome. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:237ra65-237ra65. [CrossRef]

- Tapiainen T, Paalanne N, Tejesvi MV, Koivusaari P, Korpela K, Pokka T, et al. Maternal influence on the fetal microbiome in a population-based study of the first-pass meconium. Pediatr Res 2018;84:371–9. [CrossRef]

- Zakis DR, Paulissen E, Kornete L, Kaan AM (Marije), Nicu EA, Zaura E. The evidence for placental microbiome and its composition in healthy pregnancies: A systematic review. J Reprod Immunol 2022;149. [CrossRef]

- Mishra A, Lai GC, Yao LJ, Aung TT, Shental N, Rotter-Maskowitz A, et al. Microbial exposure during early human development primes fetal immune cells. Cell 2021;184:3394-3409.e20. [CrossRef]

- Zaura E, Nicu EA, Krom BP, Keijser BJF. Acquiring and maintaining a normal oral microbiome: current perspective. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014. [CrossRef]

- Balan P, Brandt BW, Chong YS, Crielaard W, Wong ML, Lopez V, et al. Subgingival Microbiota during Healthy Pregnancy and Pregnancy Gingivitis. JDR Clin Transl Res 2020;XX:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Wu M, Chen S-W, Jiang S-Y. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:623427. [CrossRef]

- LaMar D. FastQC 2015. https://qubeshub.org/resources/fastqc.

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 2016;13:581–3. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2020). — European Environment Agency n.d.

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, Mcglinn D, et al. Package “vegan” Title Community Ecology Package Version 2.5-7 2020.

- Wemheuer F, Taylor JA, Daniel R, Johnston E, Meinicke P, Thomas T, et al. Tax4Fun2: Prediction of habitat-specific functional profiles and functional redundancy based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Environ Microbiomes 2020;15:1–12.

- Rohart F, Gautier B, Singh A, Cao KAL. mixOmics: An R package for ‘omics feature selection and multiple data integration 2017;13:e1005752.

- Worley B, Powers R. PCA as a predictor of OPLS-DA model reliability. Curr Metabolomics 2016;4:97–103.

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:11971–5. [CrossRef]

- Mueller NT, Differding MK, Østbye T, Hoyo C, Benjamin-Neelon SE. Association of birth mode of delivery with infant faecal microbiota, potential pathobionts, and short chain fatty acids: a longitudinal study over the first year of life. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2021;128:1293–303. [CrossRef]

- Park JY, Yun H, Lee S been, Kim HJ, Jung YH, Choi CW, et al. Comprehensive characterization of maternal, fetal, and neonatal microbiomes supports prenatal colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. Sci Rep 2023;13:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Collado MC, Schwab C, Zurich E, Pilar SM, Nagpal R, Tsuji H, et al. Sensitive Quantitative Analysis of the Meconium Bacterial Microbiota in Healthy Term Infants Born Vaginally or by Cesarean Section. Front Microbiol 2016;7. [CrossRef]

- Stinson LF, Boyce MC, Payne MS, Keelan JA. The not-so-sterile womb: Evidence that the human fetus is exposed to bacteria prior to birth. Front Microbiol 2019;10:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Martínez C, Santaella-Pascual M, Yagüe-Guirao G, Martínez-Graciá C. Infant gut microbiota colonization: influence of prenatal and postnatal factors, focusing on diet. Front Microbiol 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Bearfield C, Davenport ES, Sivapathasundaram V, Allaker RP. Possible association between amniotic fluid micro-organism infection and microflora in the mouth. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;109:527–33. [CrossRef]

- Balan P, Chong YS, Umashankar S, Swarup S, Loke WM, Lopez V, et al. Keystone Species in Pregnancy Gingivitis: A Snapshot of Oral Microbiome During Pregnancy and Postpartum Period. Front Microbiol 2018;9. [CrossRef]

- Han Y, Ding P-H. Advancing periodontitis microbiome research: integrating design, analysis, and technology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2025;15. [CrossRef]

- Abusleme L, Hoare A, Hong BY, Diaz PI. Microbial signatures of health, gingivitis, and periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2021;86:57–78. [CrossRef]

- Sanz M, Beighton D, Curtis MA, Cury JA, Dige I, Dommisch H, et al. Role of microbial biofilms in the maintenance of oral health and in the development of dental caries and periodontal diseases. Consensus report of group 1 of the Joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2017;44 Suppl 18:S5–11. [CrossRef]

- Abusleme L, Hoare A, Hong BY, Diaz PI. Microbial signatures of health, gingivitis, and periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2021;86:57–78. [CrossRef]

- Ihekweazu FD, Versalovic J. Development of the Pediatric Gut Microbiome: Impact on Health and Disease. Am J Med Sci 2018;356:413–23. [CrossRef]

- Korpela K, Renko M, Vänni P, Paalanne N, Salo J, Tejesvi MV, et al. Microbiome of the first stool and overweight at age 3 years: A prospective cohort study. Pediatr Obes 2020;15:e12680. [CrossRef]

- Almeida-da-Silva CLC, Savio LEB, Coutinho-Silva R, Ojcius DM. The role of NOD-like receptors in innate immunity. Front Immunol 2023;14:1122586. [CrossRef]

- Ye C, Kapila Y. Oral microbiome shifts during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes: Hormonal and Immunologic changes at play. Periodontol 2000 2021;87:276–81. [CrossRef]

- He Q, Kwok L-Y, Xi X, Zhong Z, Ma T, Xu H, et al. The meconium microbiota shares more features with the amniotic fluid microbiota than the maternal fecal and vaginal microbiota. Gut Microbes n.d.;12:1794266. [CrossRef]

- Moles L, Gómez M, Heilig H, Bustos G, Fuentes S, Vos W de, et al. Bacterial Diversity in Meconium of Preterm Neonates and Evolution of Their Fecal Microbiota during the First Month of Life. PLOS ONE 2013;8:e66986. [CrossRef]

- Taylor KD, Wood AC, Rotter JI, Guo X, Herrington DM, Johnson WC, et al. Metagenomic Study of the MESA: Detection of Gemella Morbillorum and Association With Coronary Heart Disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2024;13:e035693. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal NT, Chen RY, Griffin NW, Hibberd MC, Khalid A, Sadiq K, et al. A shared group of bacterial taxa in the duodenal microbiota of undernourished Pakistani children with environmental enteric dysfunction. mSphere 2024;9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S-M, Huang S-L. The Commensal Anaerobe Veillonella dispar Reprograms Its Lactate Metabolism and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production during the Stationary Phase. Microbiol Spectr 2023;11:e03558-22. [CrossRef]

- Theis KR, Florova V, Romero R, Borisov AB, Winters AD, Galaz J, et al. Sneathia: an emerging pathogen in female reproductive disease and adverse perinatal outcomes. Crit Rev Microbiol 2021;47:517–42. [CrossRef]

- Kim SY, Youn Y-A. Gut Dysbiosis in the First-Passed Meconium Microbiomes of Korean Preterm Infants Compared to Full-Term Neonates. Microorganisms 2024;12:1271. [CrossRef]

- Bolourian A, Mojtahedi Z. Streptomyces, shared microbiome member of soil and gut, as ‘old friends’ against colon cancer. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2018;94:fiy120. [CrossRef]

- Bacterial Diversity in Meconium of Preterm Neonates and Evolution of Their Fecal Microbiota during the First Month of Life | PLOS One n.d. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0066986 (accessed November 2, 2025).

- Huang Z, Yu K, Xiao Y, Wang Y, Xiao D, Wang D. Comparative Genomic Analysis Reveals Potential Pathogenicity and Slow-Growth Characteristics of Genus Brevundimonas and Description of Brevundimonas pishanensis sp. nov. Microbiol Spectr 2022;10:e0246821. [CrossRef]

- Hedberg ME, Moore ERB, Svensson-Stadler L, Hörstedt P, Baranov V, Hernell O, et al. Lachnoanaerobaculum gen. nov., a new genus in the Lachnospiraceae: characterization of Lachnoanaerobaculum umeaense gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from the human small intestine, and Lachnoanaerobaculum orale sp. nov., isolated from saliva, and reclassification of Eubacterium saburreum (Prévot 1966) Holdeman and Moore 1970 as Lachnoanaerobaculum saburreum comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2012;62:2685–90. [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa H, Kurushima J, Hashimoto Y, Tomita H. Progress Overview of Bacterial Two-Component Regulatory Systems as Potential Targets for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Antibiotics 2020;9:635. [CrossRef]

- Sirithanakorn C, Cronan JE. Biotin, a universal and essential cofactor: synthesis, ligation and regulation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2021;45:fuab003. [CrossRef]

- Janah L, Kjeldsen S, Galsgaard KD, Winther-Sørensen M, Stojanovska E, Pedersen J, et al. Glucagon Receptor Signaling and Glucagon Resistance. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:3314. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y, Wu Y, Zhang Q, Xiao X. Crosstalk between glucagon-like peptide 1 and gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. mBio 2023;15:e02032-23. [CrossRef]

- Murakami KS. Structural Biology of Bacterial RNA Polymerase. Biomolecules 2015;5:848–64. [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan S, Dethlefsen S, Blank LM, Siemann-Herzberg M, Schmid A. The Functional Structure of Central Carbon Metabolism in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014;80:5292–303. [CrossRef]

- Gillner DM, Becker DP, Holz RC. Lysine biosynthesis in bacteria: a metallodesuccinylase as a potential antimicrobial target. J Biol Inorg Chem JBIC Publ Soc Biol Inorg Chem 2013;18:10.1007/s00775-012-0965–1. [CrossRef]

- Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E, Turroni F, Mahony J, et al. The First Microbial Colonizers of the Human Gut: Composition, Activities, and Health Implications of the Infant Gut Microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2017;81:10.1128/mmbr.00036-17. [CrossRef]

- Park JY, Yun H, Lee S been, Kim HJ, Jung YH, Choi CW, et al. Comprehensive characterization of maternal, fetal, and neonatal microbiomes supports prenatal colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. Sci Rep 2023;13:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chang YS, Li CW, Chen L, Wang XA, Lee MS, Chao YH. Early Gut Microbiota Profile in Healthy Neonates: Microbiome Analysis of the First-Pass Meconium Using Next-Generation Sequencing Technology. Child Basel Switz 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Yu K, Rodriguez M, Paul Z, Gordon E, Gu T, Rice K, et al. Transfer of oral bacteria to the fetus during late gestation. Sci Rep 2021;11:708. [CrossRef]

- Dodson B, Suner T, Haar ELV, Han YW. Oral Microbiome and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N 1989 2025;93:e70107. [CrossRef]

| Mothers without gingivitis (NPG) (n=15) | Mothers with gingivitis (PG) (n=15) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.21 (±6.2) | 28.13 (±5.9) | 0.35 |

| Gestation age at recruitment (weeks) | 33.5 (±1.9) | 35.4 (±1.9) | 0.77 |

| Pregnancy number | 2.5 (±1.2) | 2.3 (±1.2) | 0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).