Submitted:

03 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Study Population

- Males and females aged 18–70 years.

- Residing in Mexico City or surrounding areas, systemically healthy (without self-reported chronic systemic diseases or conditions).

- With no oral hygiene performed 24 hours before sample collection and without additional use of antiseptic mouthwashes or oral hygiene aids (dental floss, interdental brushes).

- With at least 20 natural teeth (excluding third molars).

- Individuals who have undergone periodontal treatment in the past 12 months.

- Those who had taken antibiotics within the last three months.

- Pregnant or lactating women.

- Individuals using orthodontic appliances.

2.3. Sociodemographic Data

2.4. Clinical Examination and Classification

2.5. Periodontal Classification

- Periodontal Health. No clinical attachment level (CAL) nor radiographical bone loss (RBL) and probing depths (PD) ≤3 mm, assuming no pseudo pockets [31].

- Gingivitis. No CAL nor radiographical bone loss (RBL) and BoP at >10% of the teeth. Including localized and generalized gingivitis [32].

- Periodontitis in stages I or II. Following the criteria for severity, interdental CAL of 1–2 mm (stage I) or 3–4 mm (stage II) and RBL affecting only the coronal third of the root (<15% for stage I and 15–33% for stage II) [2].

- Periodontitis in stages III or IV. Following the criteria for severity, interdental CAL ≥5mm and RBL extending to middle or apical third of the root. There should be evidence of tooth loss ≤4 teeth due to periodontal reasons in stage III, and ≥5 teeth in stage IV [2].

2.6. Saliva Samples

2.7. Microbial Evaluation

2.8. Statical Analysis

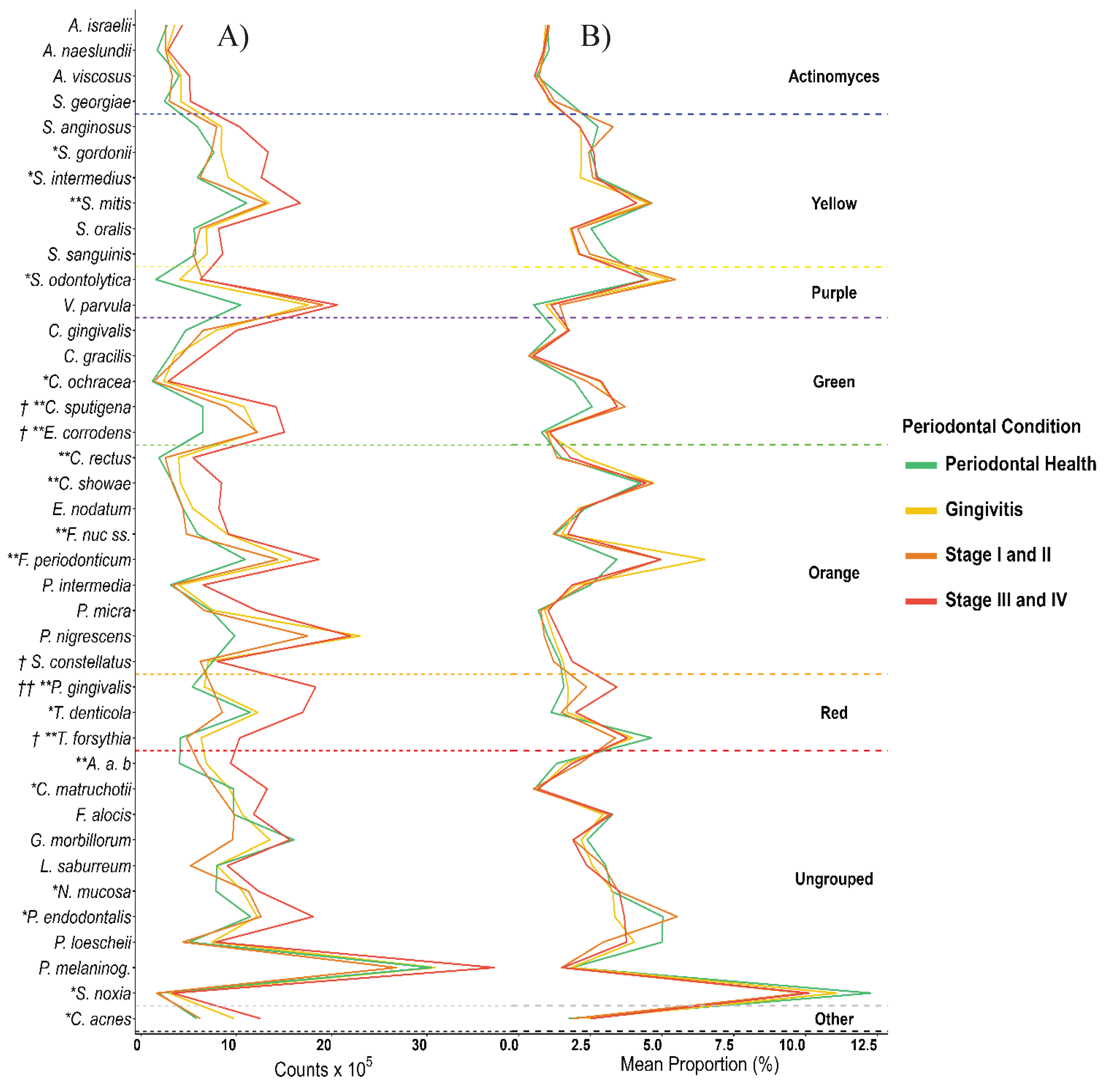

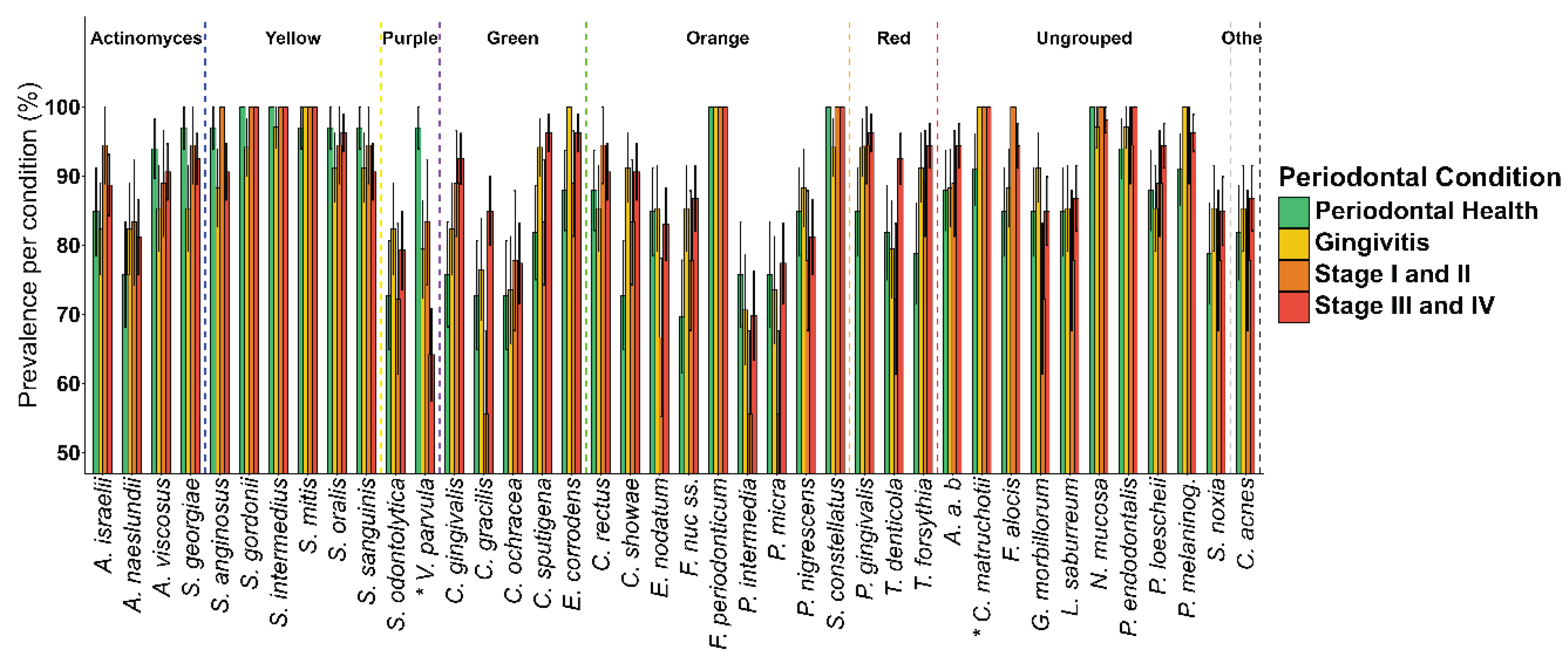

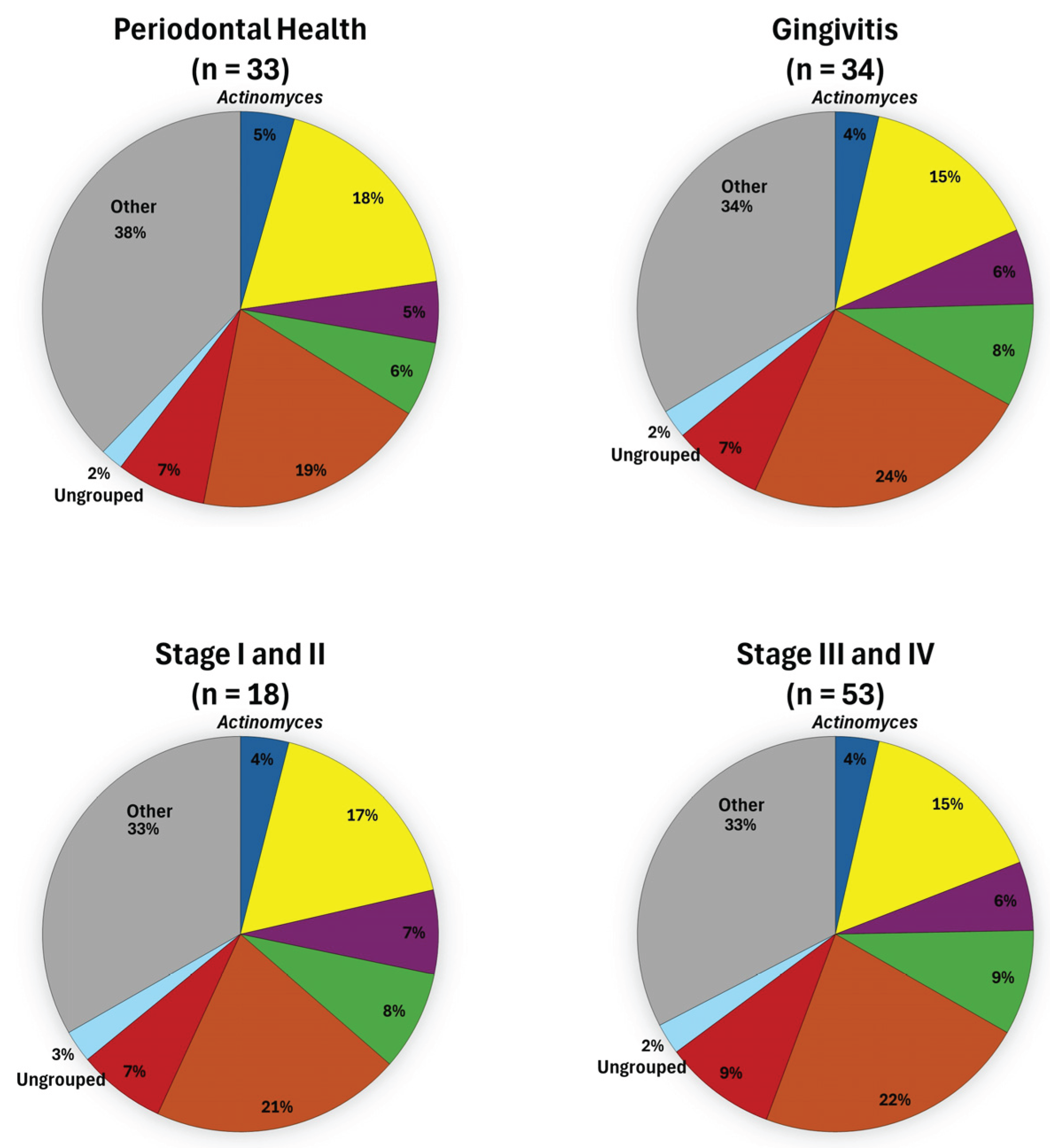

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chapple, I.L.; Mealey, B.L.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Bartold, P.M.; Dommisch, H.; Eickholz, P.; Geisinger, M.L.; Genco, R.J.; Glogauer, M.; Goldstein, M. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri--Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of periodontology 2018, 89, S74–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri--Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of periodontology 2018, 89, S173–S182. [Google Scholar]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Alba, A.L.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Konstantinidis, A.; Makrilakis, K.; Taylor, R. Periodontitis and diabetes: A two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socransky, S.; Haffajee, A. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontology 2000 2005, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serón, C.; Olivero, P.; Flores, N.; Cruzat, B.; Ahumada, F.; Gueyffier, F.; Marchant, I. Diabetes, periodontitis, and cardiovascular disease: Towards equity in diabetes care. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1270557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pinto, R.; Pietropaoli, D.; Munoz-Aguilera, E.; D’Aiuto, F.; Czesnikiewicz-Guzik, M.; Monaco, A.; Guzik, T.J.; Ferri, C. Periodontitis and hypertension: Is the association causal? High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention 2020, 27, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, C.; American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, C. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes care 2022, 45, S144–S174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioguardi, M.; Crincoli, V.; Laino, L.; Alovisi, M.; Sovereto, D.; Mastrangelo, F.; Lo Russo, L.; Lo Muzio, L. The role of periodontitis and periodontal bacteria in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liccardo, D.; Marzano, F.; Carraturo, F.; Guida, M.; Femminella, G.D.; Bencivenga, L.; Agrimi, J.; Addonizio, A.; Melino, I.; Valletta, A. Potential bidirectional relationship between periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in physiology 2020, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, W.; Takeshita, T.; Shibata, Y.; Matsuo, K.; Eshima, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Yamashita, Y. Compositional stability of a salivary bacterial population against supragingival microbiota shift following periodontal therapy. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Rasiah, I.A.; Wong, L.; Anderson, S.A.; Sissons, C.H. Variation in bacterial DGGE patterns from human saliva: Over time, between individuals and in corresponding dental plaque microcosms. Archives of oral biology 2005, 50, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belstrøm, D.; Sembler-Møller, M.L.; Grande, M.A.; Kirkby, N.; Cotton, S.L.; Paster, B.J.; Holmstrup, P. Microbial profile comparisons of saliva, pooled and site-specific subgingival samples in periodontitis patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares Nunes, L.A.; Mussavira, S.; Sukumaran Bindhu, O. Clinical and diagnostic utility of saliva as a non-invasive diagnostic fluid: A systematic review. Biochemia medica 2015, 25, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, J.M.; Schafer, C.A.; Schafer, J.J.; Farrell, J.J.; Paster, B.J.; Wong, D.T. Salivary biomarkers: Toward future clinical and diagnostic utilities. Clinical microbiology reviews 2013, 26, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E.; Bushnell, B.; Coleman-Derr, D.; Bowman, B.; Bowers, R.M.; Levy, A.; Gies, E.A.; Cheng, J.-F.; Copeland, A.; Klenk, H.-P. High-resolution phylogenetic microbial community profiling. The ISME journal 2016, 10, 2020–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Umeda, M.; Benno, Y. Molecular analysis of human oral microbiota. Journal of periodontal research 2005, 40, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Smith, C.; Martin, L.; Haffajee, J.A.; Uzel, N.G.; Goodson, J.M. Use of checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization to study complex microbial ecosystems. Oral microbiology and immunology 2004, 19, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socransky, S.; Smith, C.; Martin, L.; Paster, B.; Dewhirst, F.; Levin, A. “ Checkerboard” DNA-DNA hybridization. Biotechniques 1994, 17, 788–792. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Casarrubias, R.; Castro-Alarcón, N.; Reyes-Fernández, S.; Salazar-Hernández, E.; Vázquez-Villamar, M.; Romero-Castro, N.S. Subgingival microbiota and genetic factors (A-2570G, A896G, and C1196T TLR4 polymorphisms) as periodontal disease determinants. Frontiers in Dental Medicine 2025, 6, 1576429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mager, D.L.; Ximenez--Fyvie, L.A.; Haffajee, A.D.; Socransky, S.S. Distribution of selected bacterial species on intraoral surfaces. Journal of clinical periodontology 2003, 30, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ximénez--Fyvie, L.A.; Haffajee, A.D.; Socransky, S.S. Comparison of the microbiota of supra--and subgingival plaque in health and periodontitis. Journal of clinical periodontology 2000, 27, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, R.J.J.; Tan, K.S.; Chen, T.; Al--Hebshi, N.N.; Goh, C.E. Quantifying periodontitis--associated oral dysbiosis in tongue and saliva microbiomes—An integrated data analysis. Journal of Periodontology 2025, 96, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Kook, J.-K.; Park, S.-N.; Lim, Y.K.; Choi, G.H.; Jung, J.-S. Characteristics of the salivary microbiota in periodontal diseases and potential roles of individual bacterial species to predict the severity of periodontal disease. Microbiology Spectrum 2023, 11, e04327-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianeta, R.; Iniesta, M.; Castillo, D.M.; Lafaurie, G.I.; Sanz, M.; Herrera, D. Characterization of the subgingival cultivable microbiota in patients with different stages of periodontitis in Spain and Colombia. A cross-sectional study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Choi, Y. Point-of-care diagnosis of periodontitis using saliva: Technically feasible but still a challenge. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 2015, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical, A. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri--implant diseases and conditions–Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. 2018, 89, S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J.C.; Vermillion, J.R. The oral hygiene index: A method for classifying oral hygiene status. The Journal of the American Dental Association 1960, 61, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health, O. Oral health surveys: Basic methods. World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Weijden, G.A.; Timmerman, M.F.; Saxton, C.A.; Russell, J.I.; Huntington, E.; Van der Velden, U.; Van der Weijden, F. Intra--/inter--examiner reproducibility study of gingival bleeding. Journal of periodontal research 1994, 29, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.; Mealey, B.; Van Dyke, T.; Bartold, P.; Dommisch, H.; Eickholz, P.; Geisinger, M.; Genco, R.; Glogauer, M.; Goldstein, M. set al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol 89. [CrossRef]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Silva, C.O.; Tatakis, D.N. Plaque--induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. Journal of clinical periodontology 2018, 45, S44–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navazesh, M.; Christensen, C. A comparison of whole mouth resting and stimulated salivary measurement procedures. Journal of dental research 1982, 61, 1158–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, A.P.; Vogelstein, B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Analytical biochemistry 1983, 132, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Azuceno, C.; Martínez-Hernández, M.; Maldonado-Noriega, J.-I.; Rodríguez-Hernández, A.-P.; Ximenez-Fyvie, L.-A. Probiotic monotherapy with Lactobacillus reuteri (Prodentis) as a coadjutant to reduce subgingival dysbiosis in a patient with periodontitis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.; Socransky, S.; Sansone, C. “Reverse” DMA hybridization method for the rapid identification of subgingival microorganisms. Oral microbiology and immunology 1989, 4, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerland, M.W.; Hosmer, D.W. Tests for goodness of fit in ordinal logistic regression models. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2016, 86, 3398–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffen, A.L.; Beall, C.J.; Campbell, J.H.; Firestone, N.D.; Kumar, P.S.; Yang, Z.K.; Podar, M.; Leys, E.J. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. The ISME journal 2012, 6, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wara--Aswapati, N.; Pitiphat, W.; Chanchaimongkon, L.; Taweechaisupapong, S.; Boch, J.A.; Ishikawa, I. Red bacterial complex is associated with the severity of chronic periodontitis in a Thai population. Oral diseases 2009, 15, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ximenez--Fyvie, L.A.; Almaguer--Flores, A.; Jacobo--Soto, V.; Lara--Cordoba, M.; Moreno--Borjas, J.Y.; Alcantara--Maruri, E. Subgingival microbiota of periodontally untreated Mexican subjects with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2006, 33, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximenez--Fyvie, L.A.; Almaguer--Flores, A.; Jacobo--Soto, V.; Lara--Cordoba, M.; Sanchez--Vargas, L.O.; Alcantara--Maruri, E. Description of the subgingival microbiota of periodontally untreated Mexican subjects: Chronic periodontitis and periodontal health. Journal of periodontology 2006, 77, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.-B.; Song, H.-Y.; Son, M.J.; Li, L.; Rhyu, I.-C.; Lee, Y.-M.; Koo, K.-T.; An, J.-S.; Kim, J.S. Diagnostic models for screening of periodontitis with inflammatory mediators and microbial profiles in saliva. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigasaki, O.; Aoyama, N.; Sasaki, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Mizutani, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Gokyu, M.; Umeda, M.; Izumi, Y.; Iwata, T. Porphyromonas gingivalis, the most influential pathogen in red--complex bacteria: A cross--sectional study on the relationship between bacterial count and clinical periodontal status in Japan. Journal of Periodontology 2021, 92, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damgaard, C.; Danielsen, A.K.; Enevold, C.; Massarenti, L.; Nielsen, C.H.; Holmstrup, P.; Belstrøm, D. Porphyromonas gingivalis in saliva associates with chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Journal of oral microbiology 2019, 11, 1653123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-J.; Jeong, H.-o.; Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Joo, J.-Y.; Shin, Y.; Kang, J.; Park, A.K. Prediction of chronic periodontitis severity using machine learning models based on salivary bacterial copy number. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10, 571515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Ohara, N. Molecular mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis-host cell interaction on periodontal diseases. Japanese Dental Science Review 2017, 53, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jongh, C.A.; de Vries, T.J.; Bikker, F.J.; Gibbs, S.; Krom, B.P. Mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis to translocate over the oral mucosa and other tissue barriers. Journal of oral microbiology 2023, 15, 2205291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, B.M.; Grippaudo, C.; Polizzi, A.; Blasi, A.; Isola, G. The Key Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis Linked with Systemic Diseases. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-T.; Jeong, J.; Mun, S.; Yun, K.; Han, K.; Jeong, S.-N. Comparison of the oral microbial composition between healthy individuals and periodontitis patients in different oral sampling sites using 16S metagenome profiling. Journal of Periodontal & Implant Science 2022, 52, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Han, H.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Chung, J. Identification of potential oral microbial biomarkers for the diagnosis of periodontitis. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, M.; Ruan, Q.; Zhong, S.; Li, J.; Qi, W.; Xie, C.; Wang, X.; Abuduxiku, N.; Ni, J. Periodontal bacteria influence systemic diseases through the gut microbiota. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2024, 14, 1478362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pilar Angarita-Díaz, M.; Fong, C.; Medina, D. Bacteria of healthy periodontal tissues as candidates of probiotics: A systematic review. European journal of medical research 2024, 29, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Shetty, N.D.; Kamath, D.G. Commensalism of Fusobacterium nucleatum-The dilemma. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 2024, 28, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggen-Bueno, V.; Del Toro-Arreola, S.; Baltazar-Díaz, T.A.; Vega-Magaña, A.N.; Peña-Rodríguez, M.; Castaño-Jiménez, P.A.; Sánchez-Orozco, L.V.; Vera-Cruz, J.M.; Bueno-Topete, M.R. Intestinal dysbiosis in subjects with obesity from western mexico and its association with a proinflammatory profile and disturbances of folate (B9) and carbohydrate metabolism. Metabolites 2024, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenartova, M.; Tesinska, B.; Janatova, T.; Hrebicek, O.; Mysak, J.; Janata, J.; Najmanova, L. The oral microbiome in periodontal health. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021, 11, 629723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.; Kumar, S.P.; Rajan, R.; Mamillapalli, A. Salivary microbiota dysbiosis and elevated polyamine levels contribute to the severity of periodontal disease. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagaitkar, J.; Daep, C.A.; Patel, C.K.; Renaud, D.E.; Demuth, D.R.; Scott, D.A. Tobacco smoke augments Porphyromonas gingivalis-Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Lamont, R.J. Polymicrobial communities in periodontal disease: Their quasi--organismal nature and dialogue with the host. Periodontology 2000 2021, 86, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, O.-J.; Kwon, Y.; Park, C.; So, Y.J.; Park, T.H.; Jeong, S.; Im, J.; Yun, C.-H.; Han, S.H. Streptococcus gordonii: Pathogenesis and host response to its cell wall components. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, A.A.; Al-Taweel, F.B.; Al-Sharqi, A.J.B.; Gul, S.S.; Sha, A.; Chapple, I.L.C. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: From symbiosis to dysbiosis. Journal of Oral Microbiology 2023, 15, 2197779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, D.-P.; O, S.J.; Flavia, T.; Zhang, Y.; Jorge, F.-L. Longitudinal host-microbiome dynamics of metatranscription identify hallmarks of progression in periodontitis. Microbiome 2025, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Pu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhang, T.; Yang, S. Elongation factor Tu promotes the onset of periodontitis through mediating bacteria adhesion. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2025, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira-Junior, R.; Åkerman, S.; Klinge, B.; Boström, E.A.; Gustafsson, A. Salivary microbial profiles in relation to age, periodontal, and systemic diseases. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qin, Y.; Geng, J.; Qu, J.; Cheng, Q.; Li, K.; Zhang, D. Effect of age and systemic inflammation on the association between severity of periodontitis and blood pressure in periodontitis patients. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T.; Lamster, I.B.; Levin, L. Current concepts in the management of periodontitis. International dental journal 2021, 71, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Mun, S. Association of Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference with Periodontal Disease. Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry 2025, 23, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, A.; Thorsnes, A.; Lie, S.A.; Methlie, P.; Bunaes, D.F.; Reinholtsen, K.K.; Leknes, K.N. Periodontitis in obese adults with and without metabolic syndrome: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekar, A.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Russo, D.; Uzunçıbuk, H.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. Correlation of Body Mass Index With Severity of Periodontitis: A Cross--Sectional Study. Clinical and Experimental Dental Research 2025, 11, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reytor-González, C.; Parise-Vasco, J.M.; González, N.; Simancas-Racines, A.; Zambrano-Villacres, R.; Zambrano, A.K.; Simancas-Racines, D. Obesity and periodontitis: A comprehensive review of their interconnected pathophysiology and clinical implications. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11, 1440216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkat, M.; Janakiram, C. Association between body mass index and severity of periodontal disease among adult South Indian population: A Cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 2023, 48, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedghi, L.; DiMassa, V.; Harrington, A.; Lynch, S.V.; Kapila, Y.L. The oral microbiome: Role of key organisms and complex networks in oral health and disease. Periodontology 2000 2021, 87, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belstrøm, D.; Holmstrup, P.; Nielsen, C.H.; Kirkby, N.; Twetman, S.; Heitmann, B.L.; Klepac-Ceraj, V.; Paster, B.J.; Fiehn, N.-E. Bacterial profiles of saliva in relation to diet, lifestyle factors, and socioeconomic status. Journal of oral microbiology 2014, 6, 23609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regueira-Iglesias, A.; Suárez-Rodríguez, B.; Blanco-Pintos, T.; Relvas, M.; Alonso-Sampedro, M.; Balsa-Castro, C.; Tomas, I. The salivary microbiome as a diagnostic biomarker of periodontitis: A 16S multi-batch study before and after the removal of batch effects. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2024, 14, 1405699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population (n = 138) |

Periodontal Health (n = 33) |

Gingivitis (n = 34) |

Stage I-II (n = 18) |

Stage III-IV (n = 53) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(μ±sd) | 39.23±13.72 | 30.82±10.84 | 39.68±13.46 | 31.28±10.85 | 46.8±11.9 | 2.1x10-7 |

| Sex | 0.61* | |||||

| Male (n (%)) | 56(40.57) | 13(39.3) | 16(47.05) | 5(27.7) | 22(41.5) | |

| Female (n (%)) | 82(59.43) | 20(60.7) | 18(52.95) | 13(72.3) | 31(58.5) | |

| Marital status | 0.25* | |||||

| Single (n (%)) | 88 (63.76) | 26 (78.8) | 24 (70.5) | 11 (61.1) | 27 (50.9) | |

| Married (n (%)) | 50 (36.23) | 7 (22.2) | 10 (29.5) | 7 (38.9) | 26 (49.1) | |

| Education | 0.052* | |||||

| Complete primary (n (%)) | 8 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.71) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.66) | |

| Middle school (n (%)) | 25 (18.1) | 4 (12.12) | 9 (26.47) | 4 (22.22) | 8 (15.09) | |

| High school (n (%)) | 17 (12.3) | 3 (9.09) | 3 (8.82) | 3 (16.67) | 8 (15.09) | |

| University (n (%)) | 71 (51.4) | 22 (66.67) | 14 (41.18) | 7 (38.89) | 26 (49.06) | |

| Postgraduate (n (%)) | 17 (12.3) | 4 (12.12) | 3 (8.82) | 2 (11.11) | 8 (15.09) | |

| Occupation | 0.001* | |||||

| Homework (n (%)) | 17 (12.3) | 2 (6.06) | 4 (11.76) | 1 (5.56) | 10 (18.87) | |

| Student (n (%)) | 26(18.8) | 11 (33.33) | 6 (17.65) | 6 (33.33) | 3 (5.66) | |

| Workman (n (%)) | 16(11.5) | 1 (3.03) | 2 (5.88) | 3 (16.67) | 10 (18.87) | |

| Professional (n (%)) | 57 (41.3) | 18 (54.55) | 13(38.24) | 7 (38.89) | 19 (35.85) | |

| Other (n (%)) | 22 (15.9) | 1 (3.03) | 9 (26.47) | 1 (5.56) | 11 (20.75) | |

| Clinical variables | ||||||

| BMI (μ±sd) | 26.56±4.87 | 25.20±4.65 | 25.86±4.16 | 25.73±3.9 | 28.1±5.3 | 0.029* |

| CAL (μ±sd) | 4.89±2.32 | 3.63±1.59 | 4.17±1.6 | 4±0 | 6.4±2.6 | 1.4x10-14 |

| RBL (μ±sd) | 19.09±7.43 | 14.96±2.7 | 17.4±5.9 | 16.61±2.6 | 20.4±8.9 | 9.02x10-8 |

| PD (μ±sd) | 4.18±1.36 | 3.1±0.44 | 3.4±0.6 | 4±0 | 5.3±1.4 | 2.09x10-19 |

| BoP (μ±sd) | 25.15±21.1 | 3±3.4 | 27.8±15.8 | 30.1±20.8 | 35.5±20.7 | 1.23x10-14 |

| Surfaces with biofilm greater than 2/3 (μ±sd) | 27.5±22.7 | 14.3±14.6 | 22.1±18.7 | 31.6±21.37 | 37.9±24.6 | 2.4x10-5 |

| DMFT | 9.9±5.37 | 9.2±5.3 | 9.9±6 | 8.3±5.6 | 10.9±4.7 | 0.27 |

| Missing teeth (μ±sd) | 0.6±1.4 | 0.8±1.5 | 0.6±1.22 | 0.1±0.64 | 0.7±1.5 | 0.53 |

| OR | (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Marital status Surfaces with biofilm greater than 2/3 |

1.103 | (1.057–1.566) | < 0.001 |

| 0.335 | (0.117–0.956) | 0.034 | |

| 1.025 | (1.006–1.046) | 0.008 | |

| DMFT BMI |

0.877 | (0.802–0.956) | 0.003 |

| 1.067 | (0.977–1.167) | 0.149 | |

|

A. actinomycetemcomitans C. acnes C. ochracea C. rectus |

1.106 | (0.982–1.254) | 0.101 |

| 1.060 | (0.998 -1.130) | 0.043 | |

| 0.599 | (0.430–0.907) | 0.001 | |

| 1.326 | (1.012–1.758) | 0.057 | |

|

F. nucleatum sensu stricto P. endodontalis |

0.838 | (0.772–0.907) | < 0.001 |

| 0.939 | (0.895–0.985) | 0.009 | |

| P. gingivalis | 1.218 | (1.10–1.349) | < 0.001 |

| S. odontolytica | 1.130 | (1.046–1.224) | 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).