Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Isolation and Culture

2.2. Tube Formation Assay on MatrigelTM In Vitro

2.3. Studying the Impact of Serum Starvation on Cellular Morphology

2.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.4. Western Blot

3. Results

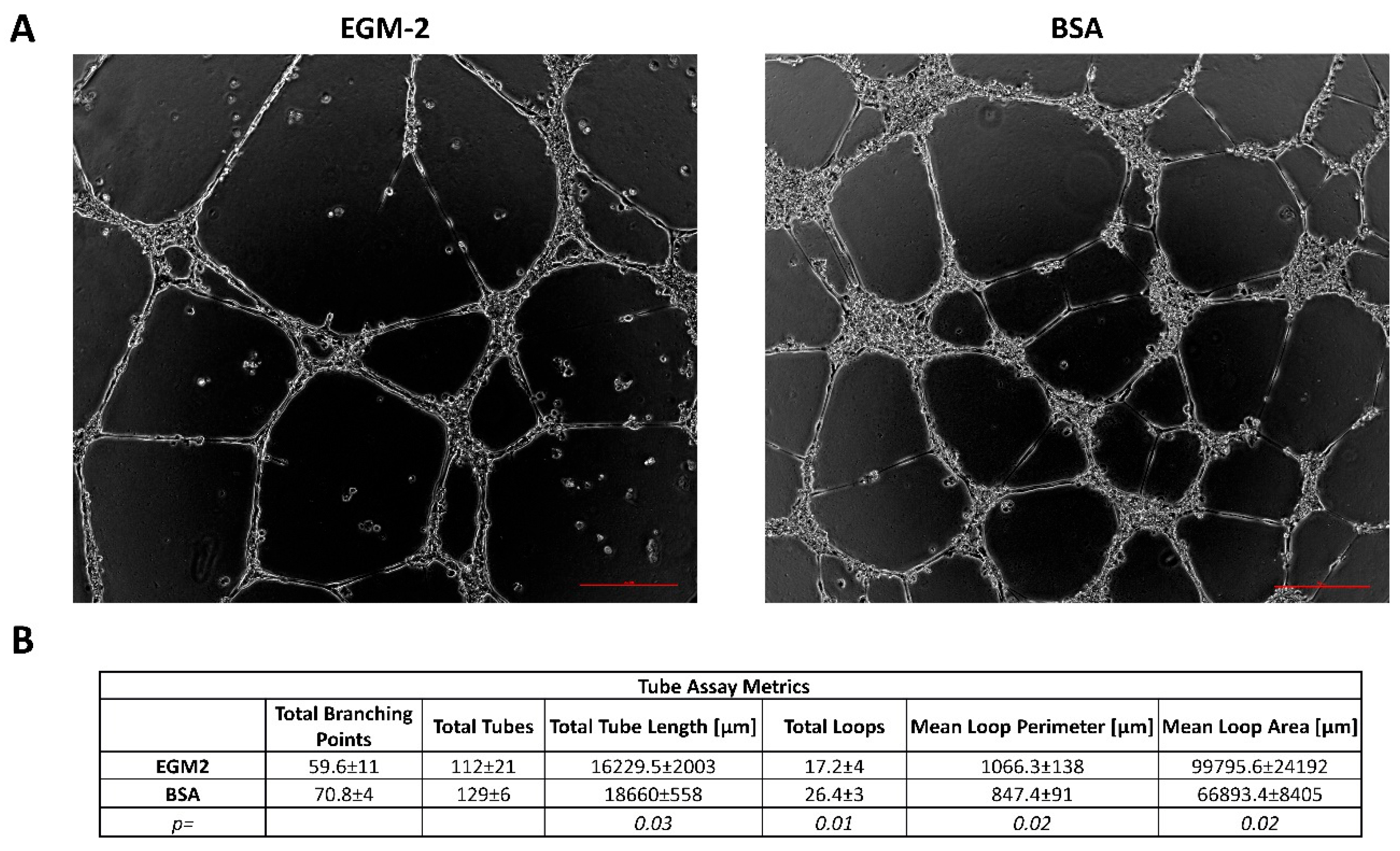

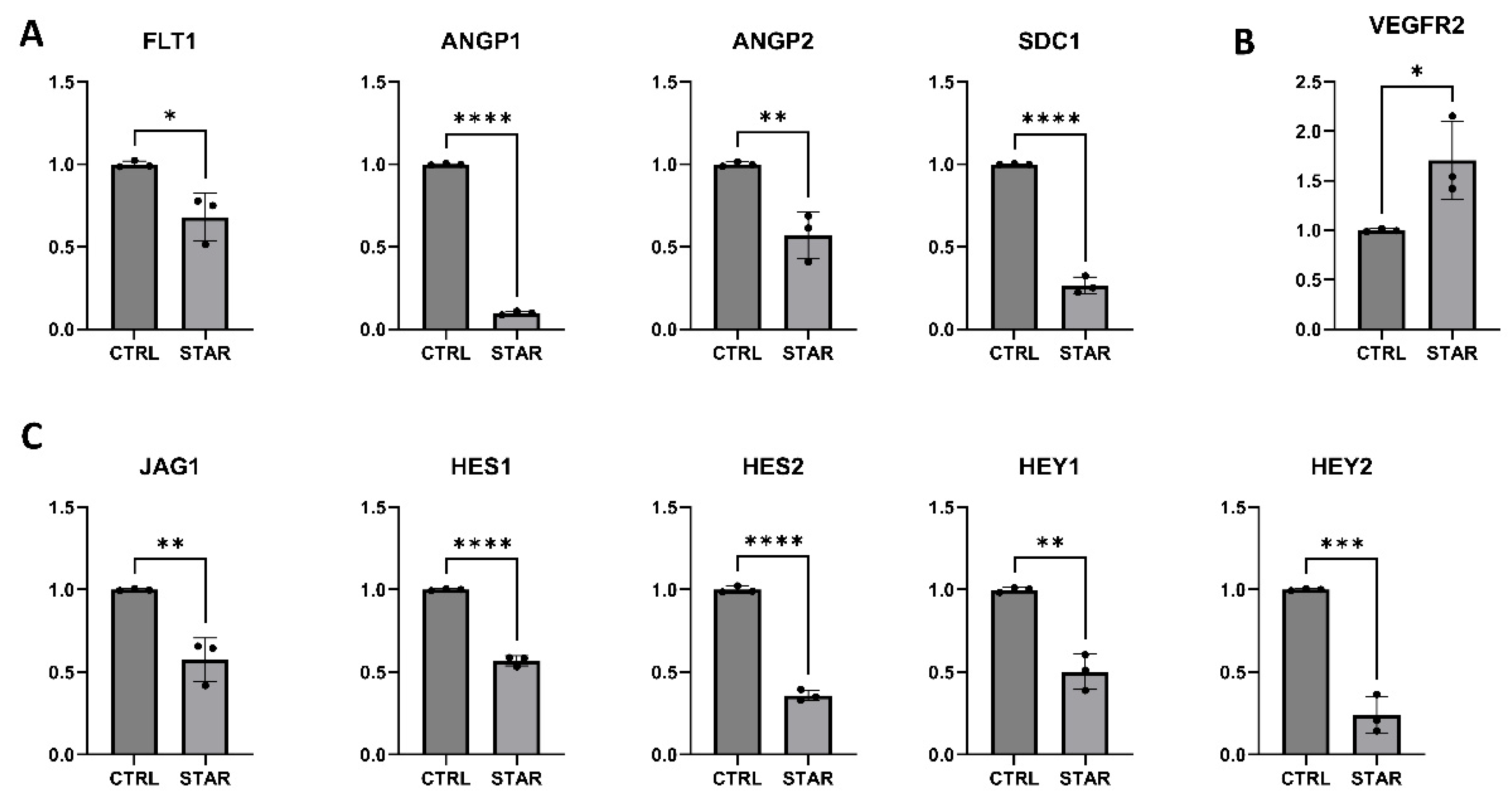

3.1. Endothelial Cells Starvation Enhances Angiogenesis

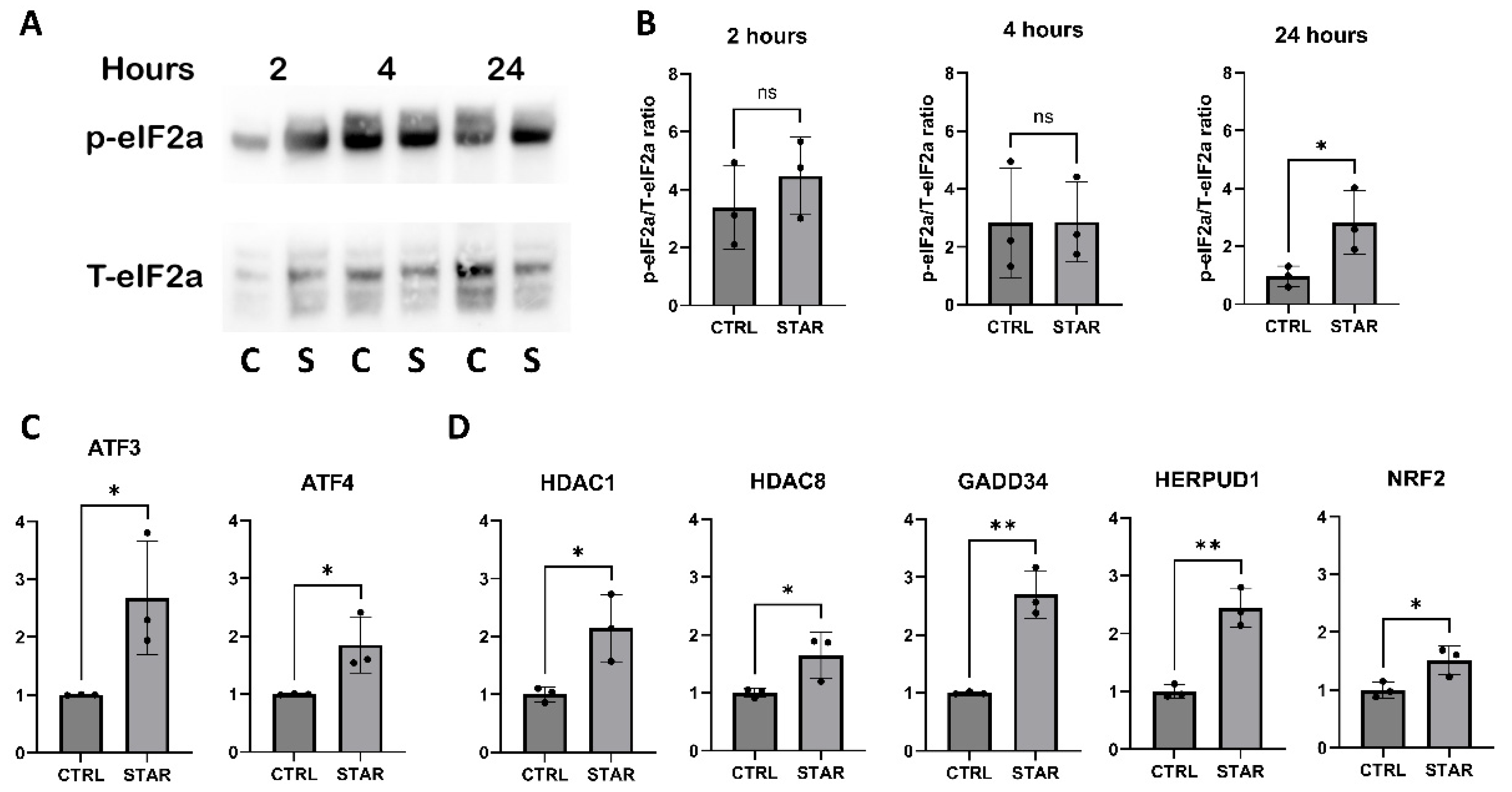

3.2. The Starvation-Associated Stress Phenotype of HUVECS Is Governed by the Integrated Stress Response Signaling

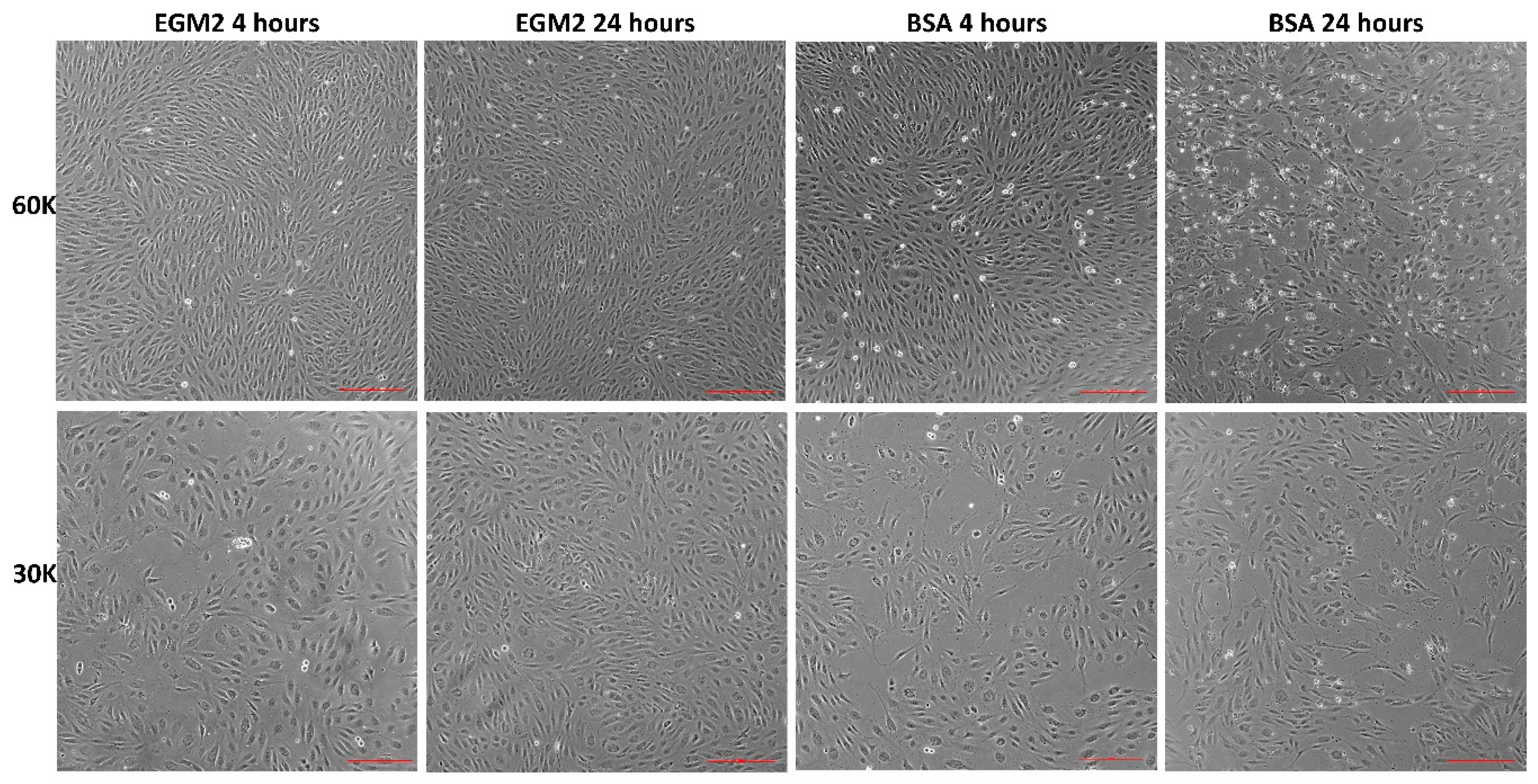

3.3. Starvation Affects HUVECS Viability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATF3 | Activating Transcription Factor 3 |

| ATF4 | Activating Transcription Factor 4 |

| ATG5 | Autophagy Related 5 |

| ATG7 | Autophagy Related 7 |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B (PKB) |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| CCL2 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (MCP-1) |

| EBM | Endothelial Basal Medium |

| EC | Endothelial Cells |

| EGM-2 MV | Endothelial Growth Medium-2 Microvascular |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 Alpha |

| EIF2AK1 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 Alpha Kinase 1 (HRI) |

| EIF2AK2 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 Alpha Kinase 2 (PKR) |

| EIF2AK3 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 Alpha Kinase 3 (PERK) |

| EIF2AK4 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 Alpha Kinase 4 (GCN2) |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERAD | ER-Associated Degradation |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| GADD34 | Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-inducible Protein 34 |

| GCN2 | General Control Nonderepressible 2 (EIF2AK4) |

| HDAC1 | Histone Deacetylase 1 |

| HDAC8 | Histone Deacetylase 8 |

| HERPUD1 | Homocysteine Inducible ER Protein With Ubiquitin Like Domain 1 |

| HRI | Heme-Regulated Inhibitor (EIF2AK1) |

| HUVECSs | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| ICAM1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| ISR | Integrated Stress Response |

| KDR | Kinase Insert Domain Receptor (VEGFR2) |

| MAPKAPK2 | MAPK-Activated Protein Kinase 2 |

| NAD⁺ | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (oxidized form) |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 |

| p38 | p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| p62/SQSTM1 | Sequestosome-1 |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PERK | Protein Kinase RNA-like ER Kinase (EIF2AK3) |

| PKR | Protein Kinase R (EIF2AK2) |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SA-β-gal | Senescence-Associated Beta-Galactosidase |

| sFlt-1 | Soluble Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1 (sVEGFR1) |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle (Krebs cycle) |

| TLA | Three Letter Acronym |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFR1 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 1 (Flt-1) |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (KDR) |

References

- Pietrocola, F.; Demont, Y.; Castoldi, F.; Enot, D.; Durand, S.; Semeraro, M.; Baracco, E.E.; Pol, J.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Bordenave, C.; et al. Metabolic Effects of Fasting on Human and Mouse Blood in Vivo. Autophagy 2017, 13, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinin, A.; Zubkova, E.; Menshikov, M. Integrated Stress Response (ISR) Pathway: Unraveling Its Role in Cellular Senescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, J.K.; Matuszcak, C.; Trepel, M.; Körbelin, J. Vascular Endothelial Cells: Heterogeneity and Targeting Approaches. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchia, P.; Conte, R.; Balza, E.; Petretto, A.; Mauri, P.; Mingari, M.C.; Carnemolla, B. A Novel Human Anti-Syndecan-1 Antibody Inhibits Vascular Maturation and Tumour Growth in Melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 2022–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, J.B.; Ambler, C.A.; Monaco, K.-A.; Johnson, N.; Rapoport, R.G.; Bautch, V.L. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor Flt-1 Negatively Regulates Developmental Blood Vessel Formation by Modulating Endothelial Cell Division. Blood 2002, 99, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharinen, P.; Alitalo, K. The Yin, the Yang, and the Angiopoietin-1. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 2157–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehling, M.; Adams, S.; Benedito, R.; Adams, R.H. Notch Controls Retinal Blood Vessel Maturation and Quiescence. Development 2013, 140, 3051–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil, A.; Gutiérrez-García, A.K.; Guenter, R.; Rose, J.B.; Beck, A.W.; Chen, H.; Ren, B. Notch Signaling in Vascular Endothelial Cells, Angiogenesis, and Tumor Progression: An Update and Prospective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Lim, A.; Edderkaoui, M.; Osipov, A.; Wu, H.; Wang, Q.; Pandol, S. Role Of YAP Signaling in Regulation of Programmed Cell Death and Drug Resistance in Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, T.; Liu, C. CCN3/NOV Inhibition Attenuates Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis of Mouse Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells by Blocking the Activation of P38 MAPK: An in Vitro Study. Brain Res. 2024, 1827, 148756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Che, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.; Lei, Y.; Lu, Z.; Sun, N.; He, J. PLAU Directs Conversion of Fibroblasts to Inflammatory Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts, Promoting Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression via UPAR/Akt/NF-ΚB/IL8 Pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won Jun, H.; Kyung Lee, H.; Ho Na, I.; Jeong Lee, S.; Kim, K.; Park, G.; Sook Kim, H.; Ju Son, D.; Kim, Y.; Tae Hong, J.; et al. The Role of CCL2, CCL7, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 in Interaction of Endothelial Cells and Natural Killer Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Valk, J. Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS): Past – Present – Future. ALTEX 2018, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkmajer, S.; Chibalin, A. V. Serum Starvation: Caveat Emptor. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2011, 301, C272–C279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, F.D.; Hamilton, K.D. Nutrient Deprivation Increases Vulnerability of Endothelial Cells to Proinflammatory Insults. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 67, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioli, M.G.; Bielli, A.; Agostinelli, S.; Tarquini, C.; Arcuri, G.; Ferlosio, A.; Costanza, G.; Doldo, E.; Orlandi, A. Antioxidant Treatment Prevents Serum Deprivation- and TNF-α-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction through the Inhibition of NADPH Oxidase 4 and the Restoration of β-Oxidation. J. Vasc. Res. 2014, 51, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M.; Fritsche-Guenther, R.; Bartsch, C.; Vietzke, A.; Eisenberger, A.; Stangl, K.; Stangl, V.; Kirwan, J.A. Serum Starvation Accelerates Intracellular Metabolism in Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M.; Witt, E.; Völker, U.; Stangl, K.; Stangl, V.; Hammer, E. Serum Starvation Induces Sexual Dimorphisms in Secreted Proteins of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs) from Twin Pairs. Proteomics 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M.; Guo, P.; Zhang, H. Effects of Serum Starvation and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Stimulation on the Expression of Notch Signalling Pathway Components. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestas, J.; Ley, K. Monocyte-Endothelial Cell Interactions in the Development of Atherosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2008, 18, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelken, N.A.; Coughlin, S.R.; Gordon, D.; Wilcox, J.N. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 in Human Atheromatous Plaques. J. Clin. Invest. 1991, 88, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, N.; Browning, J.; Howard, T.; Winterford, C.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Gobé, G. Apoptosis in Vascular Endothelial Cells Caused by Serum Deprivation, Oxidative Stress and Transforming Growth Factor-β. Endothelium 1999, 7, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Trinidad, F.R.; Arrieta Ruiz, M.; Solanes Batlló, N.; Vea Badenes, À.; Bobi Gibert, J.; Valera Cañellas, A.; Roqué Moreno, M.; Freixa Rofastes, X.; Sabaté Tenas, M.; Dantas, A.P.; et al. Linking In Vitro Models of Endothelial Dysfunction with Cell Senescence. Life 2021, 11, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, A.M.; Odell, A.F.; Mughal, N.A.; Issitt, T.; Ulyatt, C.; Walker, J.H.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S.; Ponnambalam, S. A Biphasic Endothelial Stress-Survival Mechanism Regulates the Cellular Response to Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 2297–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Mattioli, M.; Walter, P. The Integrated Stress Response: From Mechanism to Disease. Science (80-. ) 2020, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakos-Zebrucka, K.; Koryga, I.; Mnich, K.; Ljujic, M.; Samali, A.; Gorman, A.M. The Integrated Stress Response. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17, 1374–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wek, R.C. Role of EIF2α Kinases in Translational Control and Adaptation to Cellular Stress. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a032870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonyushkin, T.; Oskolkova, O. V.; Philippova, M.; Resink, T.J.; Erne, P.; Binder, B.R.; Bochkov, V.N. Oxidized Phospholipids Regulate Expression of ATF4 and VEGF in Endothelial Cells via NRF2-Dependent Mechanism: Novel Point of Convergence Between Electrophilic and Unfolded Protein Stress Pathways. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longchamp, A.; Mirabella, T.; Arduini, A.; MacArthur, M.R.; Das, A.; Treviño-Villarreal, J.H.; Hine, C.; Ben-Sahra, I.; Knudsen, N.H.; Brace, L.E.; et al. Amino Acid Restriction Triggers Angiogenesis via GCN2/ATF4 Regulation of VEGF and H2S Production. Cell 2018, 173, 117–129.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; He, Y.; Miao, X.; Yu, B. ATF4-Mediated Histone Deacetylase HDAC1 Promotes the Progression of Acute Pancreatitis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Back, S.H.; Hur, J.; Lin, Y.-H.; Gildersleeve, R.; Shan, J.; Yuan, C.L.; Krokowski, D.; Wang, S.; Hatzoglou, M.; et al. ER-Stress-Induced Transcriptional Regulation Increases Protein Synthesis Leading to Cell Death. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.H.; Cao, L.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Lombard, D.B.; Liu, J.; Bruns, N.E.; Tsokos, M.; Alt, F.W.; Finkel, T. A Role for the NAD-Dependent Deacetylase Sirt1 in the Regulation of Autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 3374–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Forward primer | Reverse primer | |

| ATF3 | GTG CCG AAA CAA GAA GAA GG | TCT GAG CCT TCA GTT CAG CA |

| ATF4 | GGT TCT CCA GCG ACA AGG | TCT CCA ACA TCC AAT CTG TCC |

| NRF2 | AAA CCA GTG GAT CTG CCA AC | GAC CGG GAA TAT CAG GAA CA |

| HK1 | GGA CTG GAC CGT CTG AAT GT | ACA GTT CCT TCA CCG TCT GG |

| SQSTM1 | CTG CCC AGA CTA CGA CTT GTG T | TCA ACT TCA ATG CCC AGA GG |

| GADD34 | TCC GAC TGC AAA GGC GGC TCA | CAG CCA GGA AAT GGA CAG TGA C |

| HPRT | CAT TAT GCT GAG GAT TTG GAA AGG | CTT GAG CAC ACA GAG GGC TAC A |

| HERPUD1 | CCA ATG TCT CAG GGA CTT GCT TC | CGA TTA GAA CCA GCA GGC TCC T |

| TEAD1 | CCT GGC TAT CTA TCC ACC ATG TG | TTC TGG TCC TCG TCT TGC CTG T |

| Sirt1 | AAA TGC TGG CCT AAT AGA GTG G | TGG TGG CAA AAA CAG ATA CTG A |

| CCL2 | AGT CTC TGC CGC CCT TCT | GTG ACT GGG GCA TTG ATT G |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).