Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Work/er Wellbeing: A Historical Overview

2.1. Phase 1: A Focus on Occupational Safety and Risk Mitigation (1900–1950)

2.2. Phase 2: Organisational Psychology – A Remedial Focus (1960–1990)

- Occupational Health Psychology (OHP) is an applied field dedicated to enhancing the quality of working life and safeguarding worker wellbeing. Core concerns include preventing and addressing stress and burnout, shaping safety behaviours and safety culture, supporting healthier work–life balance through policy and programme design, and mitigating or treating the consequences of aggression and bullying at work (Quick, 1999; Schonfeld & Chang, 2017). Today OHP remains more explicitly health-centred, prioritising workers’ wellbeing, safety, and health. Its interventions typically target the reduction of workplace stressors and risks to improve wellbeing.

- Business (Organisational) Psychology is defined as the science and practice of improving working life and organisational functioning. Key domains include personnel selection and recruitment (e.g., designing tests, interviews, and other selection procedures), training and development, performance appraisal and improvement systems, leadership and management development, change and restructuring support, and team effectiveness (Mckenna, 2020). While often intersecting with OHP, Business Psychology has a broader remit encompassing recruitment, performance, leadership, and organisational design. Interventions commonly aim to enhance outcomes such as productivity, retention, and efficiency.

2.3. Phase 3: The Holistic and Positive Wellbeing Era (1990–Present)

- Positive Organisational Psychology (POP; Donaldson & Ko, 2010).This field is concerned with the scientific study of positive subjective experiences in the workplace. Its primary focus is on individual employees and the interface between employees and their organisations. Its key aim is to develop applications that enhance individuals’ quality of life within their work context. Typical topics include occupational wellbeing, positive leadership, job satisfaction, work engagement, motivation, positive relationships, and meaningful work.

- Positive Organisational Behaviour (POB; Luthans, 2002).POB is defined as “the study and application of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace” (Luthans, 2002, p. 59). The emphasis is therefore on individual-level positive psychological states and resources that relate to wellbeing or performance, such as strengths, hope, optimism, resilience, and prosocial behaviour.

- Positive Organisational Scholarship (POS; Cameron et al., 2003).POS is defined as “the study of that which is positive, flourishing, and life-giving in organisations” (Cameron & Caza, 2004, p. 731). It focuses on organisational characteristics and processes, and on their implications for both employees and organisations. This sub-domain examines the interpersonal and structural dynamics that are activated in and through organisations (Cameron & Caza, 2004), including phenomena such as organisational virtuousness, positive deviance, and appreciative cultures (Cameron et al., 2003). Its core concern is the achievement of work-related outcomes through positive means.

3. Work/er Wellbeing: Terminological Clutter

4. Work/er Wellbeing: Definitions in Disarray

5. Tracing the Sources of the Terminological and Conceptual Tangle in Work/er Wellbeing Scholarship

5.1. Interdisciplinary Challenges

- Multidisciplinary research: In this approach, researchers from different disciplines engage with a shared research problem while largely retaining their own disciplinary lenses. The contributing disciplines remain separate, offering parallel inputs to the research question without substantial integration of their methods or theoretical frameworks.

- Interdisciplinary research: This approach is more integrative, involving the deliberate amalgamation of theories, concepts, and methods from multiple disciplines. Researchers collaborate across disciplinary boundaries to co-create new frameworks and methodological approaches, with an emphasis on synthesising and unifying diverse perspectives.

- Transdisciplinary research: This category represents the highest level of integration, extending collaboration beyond academic disciplines to include non-academic stakeholders such as policymakers and practitioners. The focus is on addressing complex, real-world problems, rather than remaining confined to discipline-based theoretical concerns.

5.2. Legacy Terminology

5.3. The Construct of Wellbeing

5.4. Category Errors

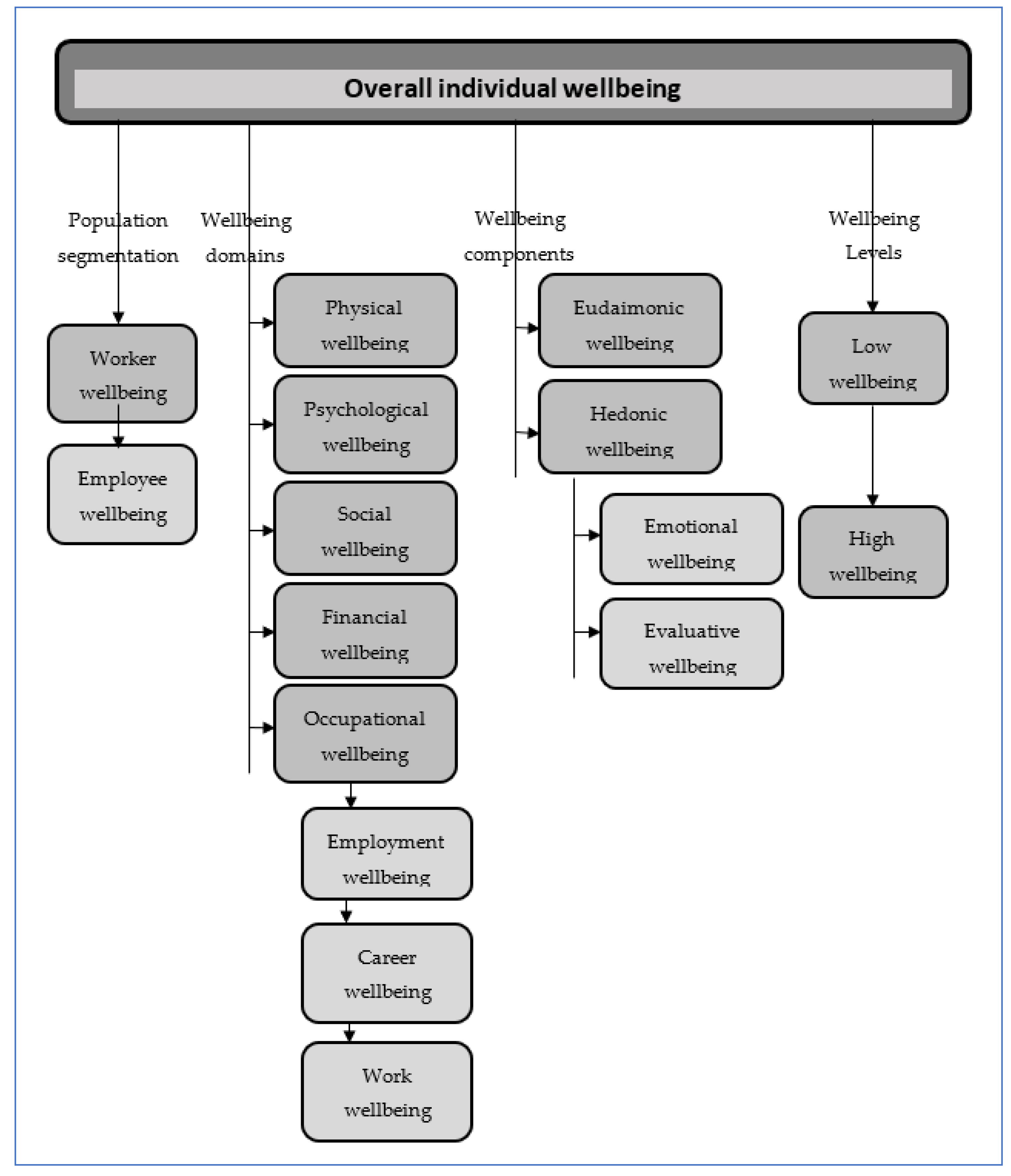

- Context free concepts: These are concepts that refer to general or overall wellbeing.

- Wellbeing domains: These are context-specific concepts, such as such as psychological wellbeing, physical wellbeing, social wellbeing, occupational wellbeing, etc.

- Components of wellbeing: These refer to terms such as happiness, hedonic, or eudaimonic wellbeing, etc.

- Population segmentations: Referring for example to worker wellbeing, employee wellbeing, entrepreneur wellbeing, etc.

- Levels of wellbeing: Use of terms such as flourishing, languishing, suffering, illbeing, etc.

6. Reconceptualising Work/er Wellbeing: Towards an Integrative Meta-Framework

6.1. Mapping the Key Concepts that Feature in Work/er Wellbeing Scholarship

6.1.1. Overall Wellbeing

6.1.2. Wellbeing Domains

- Physical wellbeing

- Psychological wellbeing

- Social wellbeing

- Financial wellbeing

- Occupational wellbeing

- Occupational wellbeing: We treat this construct both as a domain of overall wellbeing and as an overarching term that encompasses wellbeing within the vocational sphere. It encompasses three specific occupational domains:

- Employment wellbeing

- Career wellbeing

- Work wellbeing

6.1.3. Population Segmentations

- Worker wellbeing

- Employee wellbeing

6.1.4. Components of Wellbeing

- Eudaimonic wellbeing, and

- Hedonic wellbeing, which is commonly subdivided into:

- Emotional wellbeing

- Evaluative wellbeing

6.1.5. Levels of Wellbeing

7. Defining the Key Terms in the Work/er Wellbeing Scholarship

7.1. Distinguishing the Concepts of Health and Wellbeing

7.2. Components of Wellbeing

- Hedonia, characterised by the pursuit of pleasure, and

- Eudaimonia, concerned with optimal functioning across life domains.

- Cognitive component: This involves an evaluation of one’s overall life satisfaction, requiring a subjective assessment of contentment with key life domains such as health, relationships, work, and finances.

- Emotional component: This reflects the frequency with which individuals experience positive emotions (e.g., excitement, joy, love) and negative emotions (e.g., fear, anger, disgust) over a given period.

7.3. Levels of Wellbeing

- Flourishingis defined as a desired state of overall wellbeing, indicating the relative attainment of a condition where all aspects of a person’s life are positive, and their living environments are conducive (Lomas & VanderWeele, 2023).

- Thriving is conceptualised as a desired state of overall wellbeing attained despite facing challenging or inhospitable contexts and circumstances (Lomas et al., 2023).

- Languishing denotes a lower level of wellbeing located around the middle of the wellbeing continuum (Keyes, 2002). It can be defined as an ambivalent condition characterised by a relative absence of positive states of quality, without the presence of distinctly low-quality states (Lomas et al., 2023)

- Struggling is a lower state of wellbeing, described as an ambivalent condition in which individuals attain some personal states of quality while simultaneously experiencing personal states that lack quality (Lomas et al., 2023).

- Illbeing (floundering or ailing) can be understood as an undesirable condition characterised by the absence of personal states of quality alongside the presence of personal states that lack quality (Lomas et al., 2023; Venning et al., 2013).

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldrich, M. Safety first: Technology, labor, and business in the building of American work safety, 1870-1939; JHU Press, 1997; Vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Allard-Poesi, F.; Hollet-Haudebert, S. The sound of silence: Measuring suffering at work. Human Relations 2017, 70(12), 1442–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubouin-Bonnaventure, J.; Fouquereau, E.; Coillot, H.; Lahiani, F. J.; Chevalier, S. Virtuous organizational practices: a new construct and a new inventory. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 724956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’yuninnisa, R. N.; Carminati, L.; Wilderom, C. P. Promoting employee flourishing and performance: The roles of perceived leader emotional intelligence, positive team emotional climate, and employee emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Organizational Psychology 2024, 2, 1283067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, A. L.; Peterson, S. J.; Reina, C. S. Understanding well-being at work: Development and validation of the eudaimonic workplace well-being scale. PloS One 2019, 14(4), e0215957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, T. G.; Roman, G.; Khan, M.; Lee, M.; Sahbaz, S.; Duthely, L. M.; Knippenberg, A.; Macias-Burgos, M. A.; Davidson, A.; Scaramutti, C.; Gabrilove, J.; Pusek, S.; Mehta, D.; Bredella, M. A. What is well-being? A scoping review of the conceptual and operational definitions of occupational well-being. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2023, 7(1), e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, A. J.; Dillman Taylor, D. L.; Lambie, G. W. Wellness in the Helping Professions: Historical Overview, Wellness Models, and Current Trends. Journal of Wellness 2020, 2(2), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Macky, K. High-involvement work processes, work intensification and employee well-being. Work Employment and Society 2014, 28(6), 963–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, R.; Goswami, T. G. A systematic literature review of work stress. International Journal of Management Studies 2018, 3(9), 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K. S.; Caza, A. Introduction: Contributions to the discipline of positive organizational scholarship. American Behavioral Scientist 2004, 47(6), 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K. S.; Dutton, J. E.; Quinn, R. E. Cameron, K. S., Dutton, J. E., Eds.; Introduction. In Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline; Berrett-Koehler, 2003; pp. 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chari, R.; Chang, C. C.; Sauter, S. L.; Sayers, E. L. P.; Cerully, J. L.; Schulte, P.; Schill, A. L.; Uscher-Pines, L. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health: a new framework for worker well-being. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2018, 60(7), 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J.; Harter, J. Wellbeing at work; Simon and Schuster, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, P. J.; Melchert, T. P.; Connor, K. Measuring well-being: A review of instruments. The Counseling Psychologist 2016, 44(5), 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danna, K.; Griffin, R. W. Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management 1999, 25(3), 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.; Delany, K.; Napier, J.; Hogg, M.; Rushworth, M. The Value of Occupational Health to Workplace Wellbeing; The Society of Occupational Medicine, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L.; Ryan, R. M. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies 2008, 9(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Neve, J. E.; Ward, G. Why Workplace Wellbeing Matters: The Science Behind Employee Happiness and Organizational Performance; Harvard Business Press, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A. B.; Peeters, M. C.; Breevaart, K. New directions in burnout research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2021, 30(5), 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist 2000, 55(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doble, S. E.; Santha, J. C. Occupational well-being: Rethinking occupational therapy outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 2008, 75(3), 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I.; Ko, I. Positive organizational psychology, behavior, and scholarship: A review of the emerging literature and evidence base. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2010, 5(3), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I.; Lee, J. Y.; Donaldson, S. I. Evaluating Positive Psychology Interventions at work: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 2019, 4, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. I.; van Zyl, L. E.; Donaldson, S. I. PERMA+ 4: A framework for work-related wellbeing, performance and positive organizational psychology 2.0. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12, 817244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C. Chen, P. Y., Cooper, C. L., Eds.; Conceptualizing and Measuring Wellbeing at Work. In Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide; Wiley, 2014; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, C. D. Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews 2010, 12(4), 384–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriana, N.; Hutagalung, F. D.; Awang, Z.; Zaid, S. M. Happiness at work: A cross-cultural validation of happiness at work scale. PLOS One 2021, 17(1), e0261617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgeard, M. J. C.; Jayawickreme, E.; Kern, M.; Seligman, M. E. P. Doing the right thing: Measuring wellbeing for public policy. International Journal of Wellbeing 2011, 1(1), 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mata, O.; Zerón-Félix, M. A review of the theoretical foundations of financial well-being. International Review of Economics 2022, 69(2), 145–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M.; Christianson, M. K.; Price, R. H. Happiness, health, or relationships? Managerial practices and employee well-being tradeoffs. Academy of Management Perspectives 2007, 21(3), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, D. Safety and health at the heart of the past, present, and future of work. American Journal of Public Health 2020, 110(3), 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grut, A. Organization in occupational health. International Labour Review 1951, 63(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hamling, K.; Jarden, A.; Schofield, G. Recipes for occupational wellbeing: an investigation of the associations with wellbeing in New Zealand workers. New Zealand Journal of Human Resource Management 2015, 12(2), 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, R. Positive psychology: The basics; Routledge, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Horst, D. J.; Broday, E. E.; Bondarick, R.; Serpe, L. F.; Pilatti, L. A. Quality of working life and productivity: An overview of the conceptual framework. International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research 2014, 2(5), 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T. C.; Lawler, J.; Lei, C. Y. The effects of quality of work life on commitment and turnover intention; An International Journal; Social Behavior and Personality, 2007; Volume 35, 6, pp. 735–750. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P.; Ferrett, E. Introduction to health and safety at work; Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A. S. Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies 2014, 15(6), 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V. Eudaimonic and hedonic orientations: Theoretical considerations and research findings. In Handbook of eudaimonic well-being; Springer International Publishing, 2016; pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Huta, V. How distinct are eudaimonia and hedonia? It depends on how they are measured. Journal of Well-Being Assessment 2020, 4(3), 511–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarden, R. J.; Siegert, R. J.; Koziol-McLain, J.; Bujalka, H.; Sandham, M. H. Wellbeing measures for workers: a systematic review and methodological quality appraisal. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1053179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayman, M.; Glazzard, J.; Rose, A. Tipping point: The staff wellbeing crisis in higher education. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers Media SA, August 2022; Vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T. A.; Weiss, H. M.; Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D.; Hulin, C. L. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. Journal of Applied Psychology 2017, 102(3), 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, T. L. Interpretation of educational measurements; World Book Company, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Kenttä, P.; Virtaharju, J. A metatheoretical framework for organizational wellbeing research: Toward conceptual pluralism in the wellbeing debate. Organization 2023, 30(3), 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2002, 43, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M. Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly 1998, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L.; Annas, J. Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2009, 4(3), 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinowska, H.; Sienkiewicz, Ł. J. Influence of algorithmic management practices on workplace well-being–evidence from European organisations. Information Technology & People 2023, 36(8), 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine, A. K.; Rudolph, C. W.; Schmitt, A.; Zacher, H. Thriving at work: An investigation of the independent and joint effects of vitality and learning on employee health. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2023, 32(1), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerk, J. J. Spirituality, meaning in life, and work wellness: A research agenda. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 2005, 13(1), 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, A.; Gadanecz, P. Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian Teachers. Current Psychology 2022, 41(1), 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, P. A.; Rinne, R. Developing wellbeing at work: Emerging dilemmas. International Journal of Wellbeing 2015, 5(2), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P.; Cooper, C. L. Cooper, C., Leiter, M., Eds.; The state of the art of workplace wellbeing. In The Routledge companion to wellbeing at work; Routledge, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, M. J.; Dieppe, P.; Medina-Lara, A. Review of 99 self-report measures for assessing wellbeing in adults: Exploring dimensions of well-being and developments over time. BMJ Open 2016, 6(7), e010641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lintong, E. M. S.; Bukidz, D. P. Leadership and human resource management in improving employee welfare: A literature review. Jurnal Ekonomi Perusahaan 2024, 31(1), 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchfield, P.; Cooper, C.; Hancock, C.; Watt, P. Work and wellbeing in the 21st century. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2016, 13(11), 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T. Towards a positive cross-cultural lexicography: Enriching our emotional landscape through 216 ‘untranslatable’ words pertaining to well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2016, 11(5), 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T.; VanderWeele, T. J. Toward an expanded taxonomy of happiness: A conceptual analysis of 16 distinct forms of mental wellbeing. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 2023, 00221678231155512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, T.; Pawelski, J. O.; VanderWeele, T. J. A flexible map of flourishing: The dynamics and drivers of flourishing, well-being, health, and happiness. International Journal of Wellbeing 2023, 13(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. Positive organisational behaviour: Implications for the workplace. Academy of Management Executive 2002, 16, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lyall, C.; Bruce, A.; Tait, J.; Meagher, L. Interdisciplinary research journeys: Practical strategies for capturing creativity; Bloomsbury Academic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Magnier-Watanabe, R.; Benton, C.; Orsini, P.; Uchida, T. Predictors of subjective wellbeing at work for regular employees in Japan. International Journal of Wellbeing 2023, 13(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makikangas, A.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Schaufeli, W. The longitudinal development of employee well-being: A systematic review. Work & Stress 2016, 30(1), 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Schaufeli, W. The longitudinal development of employee well-being: A systematic review. Work & Stress 2016, 30(1), 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F. Well-Being as Having, Loving, Doing, and Being: An Integrative Organizing Framework for Employee Well-Being. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2025, 46, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Leiter, M. P. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 2001, 52(1), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, E. Business psychology and organizational behaviour; Routledge, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, M. C.; Rutjens, D. Applying a Positive (Organizational) Psychology Lens to the Study of Employee Green Behavior: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, Article 838932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, M. B.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress 2017, 31(2), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M. D.; Baldwin, D. R.; Datta, S. Health to Wellness A Review of Wellness Models and Transitioning Back to Health. International Journal of Health Wellness & Society 2018, 9(1). [Google Scholar]

- Page, K. M.; Vella-Brodrick, D. A. The ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ of employee well-being: A new model. Social Indicators Research 2009, 90(3), 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Maheshwari, M.; Malik, N. A systematic literature review on employee well-being: Mapping multi-level antecedents, moderators, mediators and future research agenda. Acta Psychologica 2025, 258, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. D. The subjective evaluation of well-being in adulthood: Findings and implications. Ageing International 2004, 29(2), 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peethambaran, M.; Naim, M. F. Employee flourishing-at-work: a review and research agenda. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 2025, 33(8), 2592–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, J. D. Well-being as need fulfillment: implications for theory, methods, and practice. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 2024, 58(4), 1541–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipera, M.; Fragouli, E. Employee wellbeing, employee performance & positive mindset in a crisis. The Business & Management Review 2021, 12(2), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, E.; Lee, P. Child well-being: a systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research 2003, 61(1), 9–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R. K.; Hati, L. The measurement of employee well-being: development and validation of a scale. Global Business Review 2022, 23(2), 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J. C. Occupational health psychology: The convergence of health and clinical psychology with public health and preventive medicine in an organizational context. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 1999, 30(2), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, K. S.; Shalini, T. R.; Kumar, S.; Ashwini, V. Sengupta, S. S., Jyothi, P., Kalagnanam, S., Charumathi, B., Eds.; Exploring the Organizational and Individual roles influencing Employee Well-being. In Organisation, Purpose and Values; Routledge, 2024; pp. 538–553. [Google Scholar]

- Rautenbach, C.; Rothmann, S. Antecedents of flourishing at work in a fast-moving consumer goods company. Journal of Psychology in Africa 2017, 27(3), 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redelinghuys, K.; Rothmann, S.; Botha, E. Flourishing-at-work: The role of positive organizational practices. Psychological Reports 2019, 122(2), 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riitsalu, L.; Atkinson, A.; Pello, R. The bottlenecks in making sense of financial well-being. International Journal of Social Economics 2023, 50(10), 1402–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, L. J. Wellness: A review of theory and measurement for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development 2009, 87(2), 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 57(6), 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D.; Boylan, J. M.; Kirsch, J. A. Lee, M. T., Kubzansky, L. D., VanderWheele, T. J., Eds.; Eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. In Measuring well-being; Oxford University Press, 2021; pp. 92–135. [Google Scholar]

- Salavera, C.; Urbón, E. Emotional wellbeing in teachers. Acta Psychologica 2024, 245, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, S. A. F. M. Applying Positive Organizational Psychology to Foster a Healthy Workplace Environment: A Systematic and Interactive Review. Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems 2025, 4(1), 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Saraswati, J. M. R.; Milbourn, B. T.; Buchanan, A. J. Re-imagining occupational wellbeing: Development of an evidence-based framework. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 2019, 66(2), 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D. R. C.; Dantas, R. A. S.; Marziale, M. H. P. Quality of life at work: Brazilian nursing literature review. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 2008, 21, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, I. S.; Chang, C. H. Occupational health psychology; Springer Publishing Company, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, P.; Vainio, H. Well-being at work–overview and perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2010, 422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Wellbeing; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2018, 13(4), 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M.; Lyubomirsky, S. Revisiting the sustainable happiness model and pie chart: Can happiness be successfully pursued? The Journal of Positive Psychology 2021, 16(2), 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Tay, L.; & Nesher Shoshan, H. A review on health and well-being at work: More than stressors and strains. Personnel Psychology 2023, 76(2), 473–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A. M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science 2005, 16(5), 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavropoulos, T. G.; Andreadis, S.; Kontopoulos, E.; Kompatsiaris, I. SemaDrift: A hybrid method and visual tools to measure semantic drift in ontologies. Journal of Web Semantics 54 2019, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M. B. Familiar medical quotations; Little Brown, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. Working paper: Current measures and the challenges of measuring children’s wellbeing; Office for National Statistics, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Valtonen, A.; Saunila, M.; Ukko, J.; Treves, L.; Ritala, P. AI and employee wellbeing in the workplace: An empirical study. Journal of Business Research 2025, 199, 115584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, L. E.; Stander, M. W.; Rothmann, S. Positive Organisational Psychology 2.0: Embracing the Technological Revolution to Advance Individual, Organisational, and Societal Well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology 2023, 19(4), 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venning, A.; Wilson, A.; Kettler, L.; Eliott, J. Mental health among youth in South Australia: A survey of flourishing, languishing, struggling, and floundering. Australian Psychologist 2013, 48, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J. Making a healthy change: a historical analysis of workplace wellbeing. Management & Organizational History 2022, 17(1–2), 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. B. Decision latitude, job demands, and employee well-being. Work & Stress 1990, 4(4), 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N., Eds.; Well-being and the workplace. In Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology; Russell Sage Foundation, 1999; pp. 392–412. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P.; Nielsen, K. Wellbeing and Work Performance. In Handbook of Well-Being; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M.; Donaldson, S. I.; Luthans, F. Warren, M., Donaldson, S. I., Eds.; Taking positive psychology to the workplace: Positive organizational psychology, positive organizational behavior, and positive organizational scholarship. In Scientific advances in positive psychology; Praeger, 2017; pp. 195–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wartenberg, G.; Aldrup, K.; Grund, S.; Klusmann, U. Satisfied and high performing? A meta-analysis and systematic review of the correlates of teachers’ job satisfaction. Educational Psychology Review 2023, 35(4), 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassell, E.; Dodge, R. A multidisciplinary framework for measuring and improving wellbeing. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res 2015, 21(1), 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wicken, A. W. Wellness in industry. Work 2000, 15(2), 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijngaards, I.; King, O. C.; Burger, M. J.; van Exel, J. Worker well-being: What it is, and how it should be measured. Applied Research in Quality of Life 2022, 17(2), 795–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. H. I. Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2015, 36(5), 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Definition |

| Overall wellbeing | Personal wellbeing may be understood as life satisfaction derived from an individual’s perceptions of their health, happiness, and sense of purpose (Litchfield et al., 2016). |

| Overall health | Overall health comprises a range of factors, including physical, mental, and social wellbeing, and is not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (Jarden et al., 2023). |

| Worker wellbeing | Chari et al. (2018) conceptualised worker wellbeing as a quality-of-life construct, referring to an individual’s health in relation to environmental, organisational, and psychosocial factors associated with work. Wellbeing is understood as the experience of positive perceptions and enabling conditions at, and outside of, work, that allow workers to thrive and realise their full potential. The authors further stressed that worker wellbeing should encompass both work and nonwork domains and should be assessed using both subjective and objective indicators. |

| Jarden et al. (2023) proposed that worker wellbeing can be understood as the balance between an individual’s resources and the challenges they face at work, with key components including subjective wellbeing, eudaimonic wellbeing, and social wellbeing. | |

| Employee wellbeing | Employee wellbeing refers to the overall quality of an individual’s experience at work, encompassing their physical, psychological, social, financial, and spiritual wellbeing (Pandey et al., 2025). |

| Page and Vella-Brodrick (2009) posited that subjective and psychological wellbeing should be regarded as key components of employee wellbeing. | |

| Warr (1990) defined employee wellbeing as the overall quality of an employee’s experience and functioning at work. He later refined this definition (Warr, 1999), describing it as the employee’s experience and functioning, incorporating both physical and psychological dimensions. | |

| Martela (2025) conceptualised employee wellbeing as a broad, subjective umbrella construct that encompasses the various factors that make work a positive experience for employees. | |

| Kinowska and Sienkiewicz (2023) observed that employee wellbeing is frequently conceptualised in terms of psychological wellbeing, which comprises two perspectives: a hedonic perspective, concerned with positive emotions and satisfaction, and a eudaimonic perspective, centred on the realisation of human potential. | |

| Employee wellbeing can be defined as an evaluation of employees’ physical, mental, and social state, encompassing both their work and non-work life experiences (Pipera & Fragouli, 2021). | |

| Grant et al. (2007) defined employee wellbeing as the overall quality of employees’ experience and functioning in the workplace. | |

| Boxall and Macky (2014) conceptualised employee wellbeing as a holistic construct comprising job satisfaction, physical health, mental health, and relationship outcomes. | |

| Danna and Griffin (1999) described employee wellbeing as encompassing employees’ physical and mental health, spanning both their work and broader life experiences. | |

| Employee wellbeing can be defined as how individuals feel and function within their workplaces. (Valtonen et al., 2025). | |

| Zheng et al. (2015) maintained that employee wellbeing can be understood as employees’ quality of life and psychological state in the workplace. | |

| Occupational wellbeing | Occupational wellbeing denotes the sense of meaning and satisfaction that individuals derive from their occupational lives (Doble & Santha, 2008). |

| Saraswati et al. (2019) proposed a framework in which occupational wellbeing is understood as the subjective meaning a person ascribes to their occupational life. It comprises several intrinsic needs: agency, accomplishment, affirmation, pleasure renewal, coherence, and companionship. | |

| Work wellbeing | Laine and Rinne (2015), in their review of 316 papers, observed that most contemporary definitions of work wellbeing employ subjective wellbeing as a key indicator, referring to individuals’ cognitive and affective evaluations of their lives. Psychological wellbeing constitutes another core component of work wellbeing, reflecting positive psychological functioning. |

| Work/place wellbeing | De-Neve and Ward (2025) used the term work wellbeing interchangeably with workplace wellbeing and observed that researchers frequently conflate workplace wellbeing with workplace subjective wellbeing (often labelled workplace happiness) and therefore proposed a definition of workplace wellbeing grounded in subjective wellbeing. Workplace subjective wellbeing, in their view, comprises three elements: evaluative job satisfaction, emotional experiences at work, and eudaimonic work wellbeing, that is, experiencing work as purposeful, worthwhile, or meaningful. They further argued that eudaimonia is embedded within subjective wellbeing. |

| Workplace wellbeing | Wallace (2022) conceptualised workplace wellbeing as a biopsychosocial construct encompassing physical, mental, and social health. |

| According to Leiter and Cooper (2017) workplace wellbeing encompasses physical health and comfort, mental health, a predominance of positive over negative affect, and favourable attitudes towards one’s work. | |

| Workplace well-being, is “defined as an employee’s subjective evaluation of his or her ability to develop and optimally function within the workplace” (Bartels et al., 2019, p.3) and incorporates 11 dimensions: Six that are incorporated in Ryff’s (1989) Psychological Wellbeing model (purpose, autonomy, mastery, relationship, and self acceptance), and five drawn from Keyes’ (1998) Social Wellbeing model (social integration, social acceptance, social contribution, social actualization, and social coherence). | |

| Workplace wellbeing refers to employees’ overall experience and functioning, encompassing both physical and psychological dimensions. It is a construct that is partly determined by employees’ personality traits and partly shaped by their working conditions (Kinowska & Sienkiewicz, 2023). | |

| Wellbeing at work | Fisher (2014) proposed that wellbeing at work comprises three components: subjective wellbeing at work (including positive attitudinal judgements and the experience of positive and negative affect), eudaimonic wellbeing at work (involving engagement in growth-oriented, self-actualising behaviours), and social wellbeing at work (centred on the relational aspects of work). |

| Work wellness | Work wellness is an optimal state of living that each individual can attain, encompassing physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing. It may be defined as a way of life oriented towards optimal health and wellbeing, in which body, mind, and spirit are integrated to enable fuller participation in both human and natural communities (Klerk, 2005). |

| Wicken (2000) described work wellness as a component of overall wellness, defined as the process of becoming aware of and making choices toward a more successful existence. It encompassed several dimensions such as social, spiritual, physical, occupational, emotional and intellectual. | |

| Employee welfare | Lintong and Bukidz (2024) defined employee welfare as a state in which individuals feel happy, healthy, and safe, and have opportunities to develop their potential. |

| Quality of work life | Horst et al. (2014) defined quality of work life as employees’ evaluation of the demands they face and the aspirations they hold in relation to working conditions, remuneration, professional development, work–family and role balance, safety, and social interactions in the workplace. |

| Quality of work life refers to the favourable workplace conditions and environments that support employees’ welfare and wellbeing (Huang et al., 2007). | |

| Quality of life at work | Quality of life at work “has been understood as the dynamic and comprehensive management of physical, technological, social, and psychological factors that affect culture and renew the organisational environment” (Schmidt et al., 2008, p.331). |

| Subjective Wellbeing at Work | Subjective wellbeing at work refers to employees’ day-to-day emotional experiences at work, both positive and negative, as well as their satisfaction with their work (Magnier-Watanabe et al., 2023). |

| Workplace happiness | Workplace happiness describes employees’ experience of feeling energised and enthusiastic about their work, perceiving it as meaningful and purposeful, enjoying positive relationships at work, and feeling committed to their jobs (Kun & Gadanecz, 2022). |

| Happiness at work | Fitriana et al. (2021) defined happiness at work as feeling good about one’s work, feeling positive about job characteristics, and feeling aligned with the organisation as a whole, reflected in pleasant judgements and experiences such as positive feelings, flow at work, moods, and emotions. |

| Job satisfaction | Judge et al. (2017) defined job satisfaction as the overall evaluative judgement one holds about one’s job. It represents an assessment of the favourability of the job, typically conceptualised along a continuum from positive to negative. Organisational psychologists distinguish between overall satisfaction—one’s evaluation of the job as a whole—and facet satisfactions, which concern specific aspects of the job, such as work tasks, pay, promotions, supervision, or coworkers, such as those that make up the job. |

| Workplace flourishing | According to Rautenbach (2015) workplace flourishing comprises three dimensions: emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing. |

| Flourishing at work | Flourishing at work refers to a high state of employee wellbeing that arises from positive work experiences and the effective management of job-related factors (Redelinghuys et al., 2019). |

| Thriving at work | Spreitzer et al. (2005) conceptualised thriving at work as a psychological state characterised by employees’ vitality and learning. Thriving employees feel energised and alive, while simultaneously perceiving that they are gaining new knowledge and skills. |

| Concept | Definition | Notes | Synonymous terms |

| Overall wellbeing | A continuum that reflects the relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality across key life domains (Lomas et al., 2023). | Represents “a life well lived.” Aggregates several wellbeing domains (physical, psychological, occupational, financial, and social wellbeing). |

General wellbeing, global wellbeing, complete wellbeing |

| Population segmentation | |||

| Worker wellbeing | A continuum that reflects a worker’s relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality across key life domains (Lomas et al., 2023). | The overall wellbeing of working people (Wijngaards et al., 2022). Similar to overall wellbeing, it aggregates several wellbeing domains. |

|

| Employee wellbeing | A continuum that reflects an employee’s relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality across key life domains (Lomas et al., 2023). | The overall wellbeing of those employed by organisations (Wijngaards et al., 2022). Similar to overall wellbeing, it aggregates several wellbeing domains |

|

| Work-related domains | |||

| Occupational wellbeing | A continuum that reflects the relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality in the occupational domain. | An overarching term that encompasses a person’s employment wellbeing, career wellbeing, and work wellbeing. | |

| Employment wellbeing | A continuum that reflects the relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality in the employment domain. | Pertains specifically to the domain of employment, encompassing wellbeing in relation to one’s current employment circumstances, including unemployment, employment, overemployment, underemployment, and other related conditions. | |

| Career wellbeing | A continuum that reflects the relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality in the career domain. | Refers specifically to the career domain, encompassing an individual’s longer-term career trajectory and mobility across workplaces and roles. | |

| Work wellbeing | A continuum that reflects the relative attainment of a personal subjective state of quality in their current work domain. | Denotes wellbeing specifically in relation to an individual’s present work situation. | Workplace wellbeing, wellbeing at work |

| Concept | Definition | Notes | Synonymous terms |

| Overall happiness | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment and emotional experience across key life domains. | Includes both the emotional experience and the evaluative component. Aggregates several life domains (physical, psychological, occupational, financial, and social wellbeing). |

General / global / overall subjective wellbeing, general / global happiness |

| Life satisfaction | A continuum that reflects a person’s overall contentment with life across key life domains. | Contains the evaluative component of happiness. | Satisfaction with life. |

| Emotional wellbeing | A continuum that reflects a person’s emotional experience across key life domains. | Contains the emotional experience of happiness. |

General / overall / global emotional wellbeing, hedonic / affective wellbeing |

| Population segmentation | |||

| Worker happiness | A continuum that reflects a worker’s contentment and emotional experience across key life domains. | Pertains to working people. Includes both an emotional experience and the evaluative component. Aggregates several life domains (physical, psychological, occupational, financial, and social wellbeing). |

Worker Subjective Wellbeing |

|

Employee happiness |

A continuum that reflects an employee’s contentment and emotional experience across key life domains. | Pertains to employees. Includes both an emotional experience and the evaluative component. Aggregates several life domains (physical, psychological, occupational, financial, and social wellbeing). |

Employee Subjective Wellbeing |

| Worker life satisfaction | A continuum that reflects a worker’s contentment with life across key life domains. | Contains the evaluative component of happiness. | Worker satisfaction with life. |

|

Employee life satisfaction |

A continuum that reflects an employee’s contentment with life across key life domains. | Contains the evaluative component of happiness. | Employee satisfaction with life. |

| Worker emotional wellbeing | A continuum that reflects a worker’s emotional experience across key life domains. | Contains the emotional component of happiness. | Worker hedonic / affective wellbeing |

|

Employee emotional wellbeing |

A continuum that reflects an employee’s emotional experience across key life domains | Contains the emotional component of happiness. | Employee hedonic / affective wellbeing |

| Work-related domains | |||

|

Happiness with one’s occupational state |

A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment and emotional experience within their current occupation. | Includes both the emotional experience and the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the occupational domain. |

Subjective occupational wellbeing |

| Happiness with one’s employment | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment and emotional experience within their current employment. | Includes both the emotional experience and the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the employment domain. |

Subjective employment wellbeing |

| Happiness with one’s career | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment and emotional experience within their career domain. | Includes both the emotional experience and the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the career domain. |

Subjective career wellbeing |

| Happiness with work | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment and emotional experience within their current work domain | Includes both the emotional experience of quality and the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the work domain. |

Workplace happiness, Happiness at work, subjective wellbeing at work, subjective work wellbeing |

| Satisfaction with one’s occupational state | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment with their current occupational state. | Includes only the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the occupational domain. |

Occupational satisfaction |

| Satisfaction with one’s employment | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment with their current employment. | Includes only the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the employment domain. |

Employment satisfaction |

| Satisfaction with one’s career | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment with their career, | Includes only the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the career domain. |

Career satisfaction |

| Satisfaction with work | A continuum that reflects a person’s contentment with their current work. | Includes only the evaluative component. Refers specifically to the work domain. |

Job / work / workplace satisfaction |

| Occupation related hedonic wellbeing | A continuum that reflects a person’s emotional experience within their current occupation. | Includes only the emotional component. Refers specifically to the occupational domain. |

Occupation related emotional / affective wellbeing |

| Employment related hedonic wellbeing | A continuum that reflects a person’s emotional experience within their current employment. | Includes only the emotional component. Refers specifically to the employment domain. |

Employment related emotional / affective wellbeing |

|

Career related Hedonic wellbeing |

A continuum that reflects a person’s emotional experience within their career. | Includes only the emotional component. Refers specifically to the career domain. |

Career related emotional / affective wellbeing |

| Work related hedonic wellbeing | A continuum that reflects a person’s emotional experience within their current work. | Includes only the emotional component. Refers specifically to the work domain. |

Job / work / related emotional / affective wellbeing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).