Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

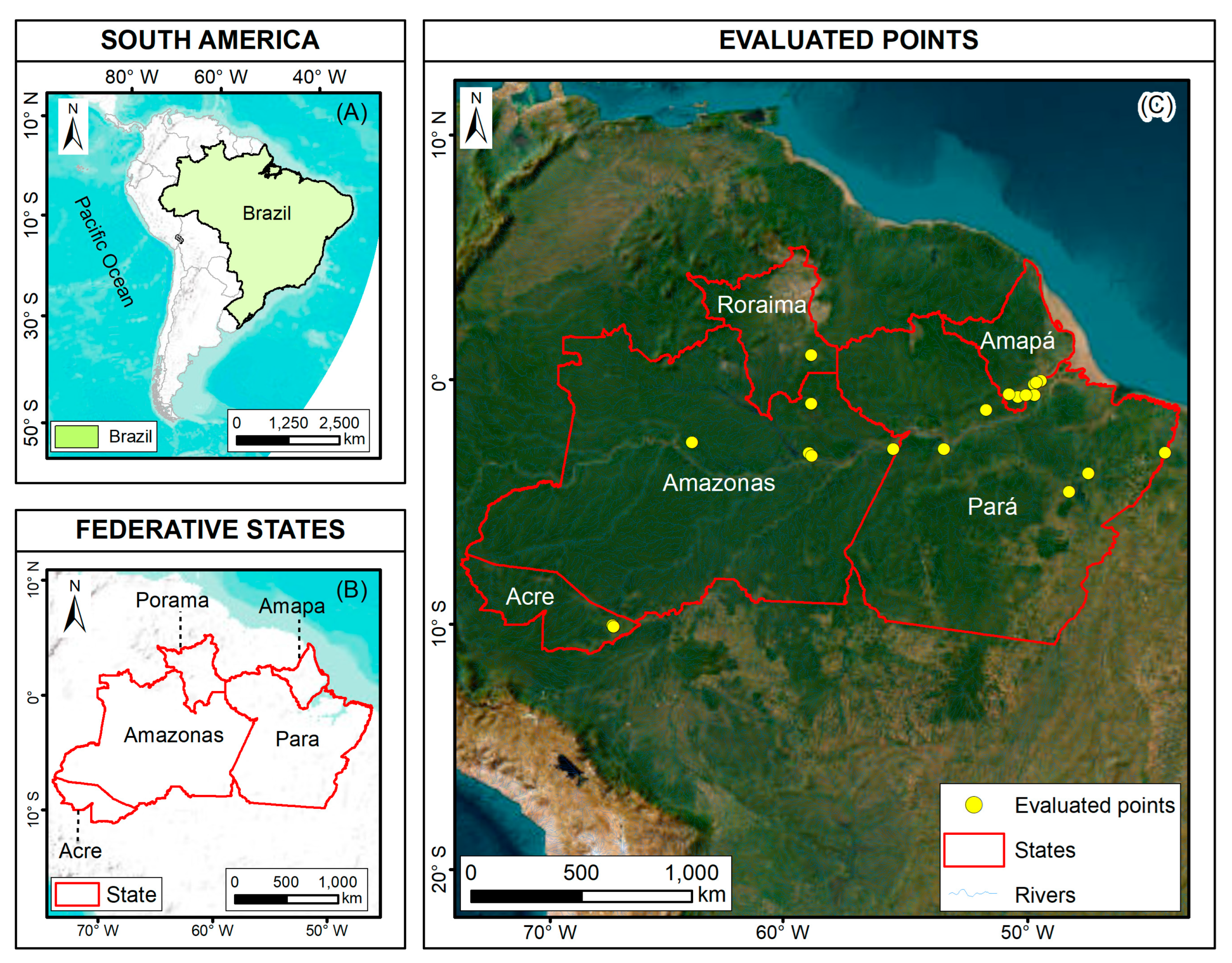

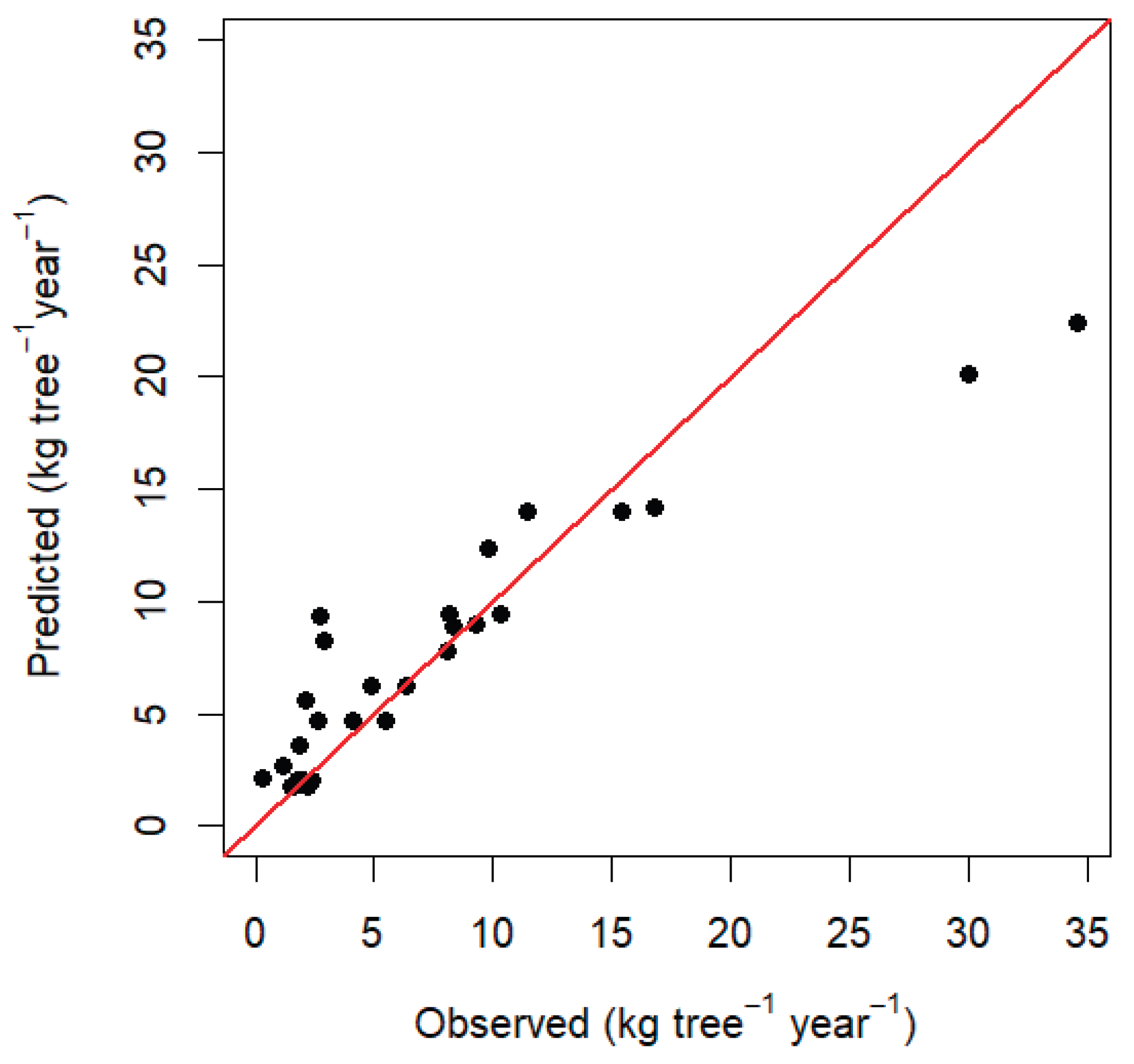

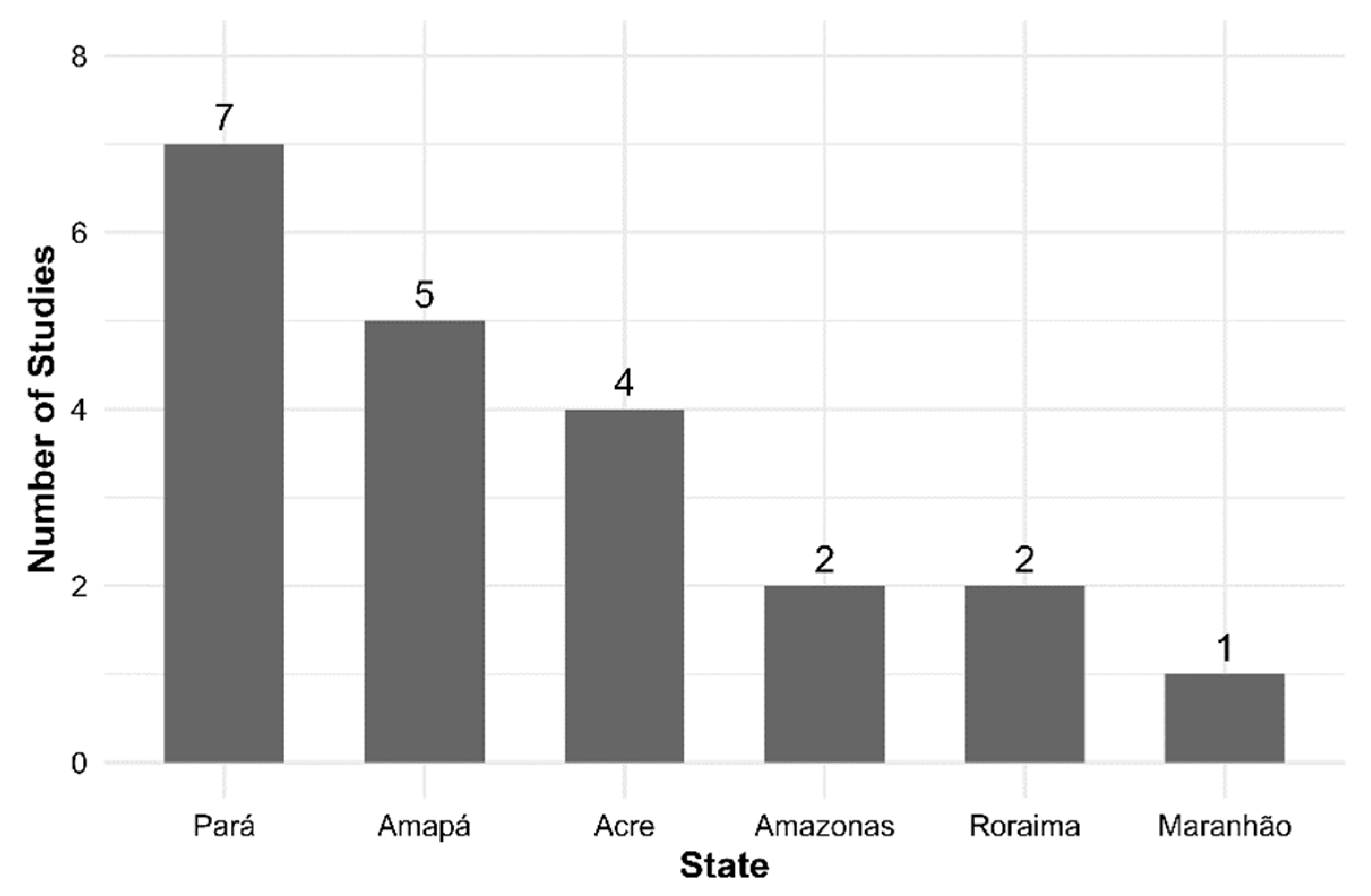

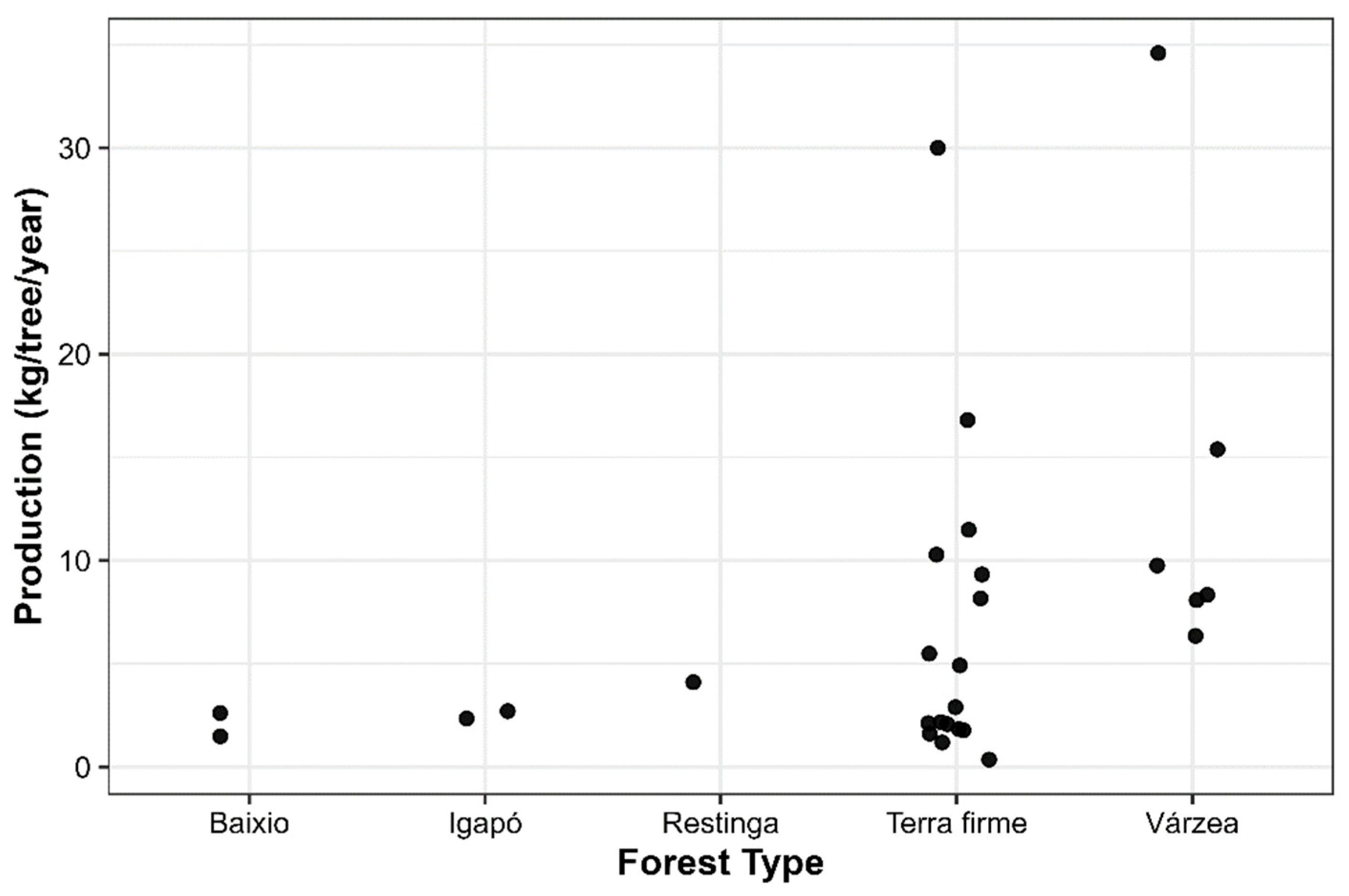

Carapa guianensis Aubl., widely distributed throughout the Amazon, is recognized for its ecological, economic, and social importance, and constitutes a key source of income for numerous extractive communities. However, fruit production exhibits marked spatial variation that may be influenced by soil properties and climatic factors. In this study, we assessed this variability using data from 21 studies conducted in the Brazilian Amazon, incorporating georeferenced information from each site on climate and soil characteristics. Environmental variables were evaluated using Random Forest models. Average fruit productivity showed a broad range (0.34 to 34.6 kg·tree⁻¹·year⁻¹), with higher values in várzea forests (16.5 kg·tree⁻¹·year⁻¹) and lower values in igapó forests (2.5 kg·tree⁻¹·year⁻¹). The model explained 42% of the observed variability (R² = 0.83 in cross-validation), identifying soil organic carbon, mean annual temperature, and clay content as the most influential predictors. These findings demonstrate that fruit production is shaped by the interaction between edaphic and climatic conditions, which determine the species’ productivity patterns, and highlight the need to foster adaptive management strategies that ensure the sustainable use of andiroba across Amazonian ecosystems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Acquisition of Fruit Production Data

2.2. Environmental Variables

2.3. Random Forest

3. Results

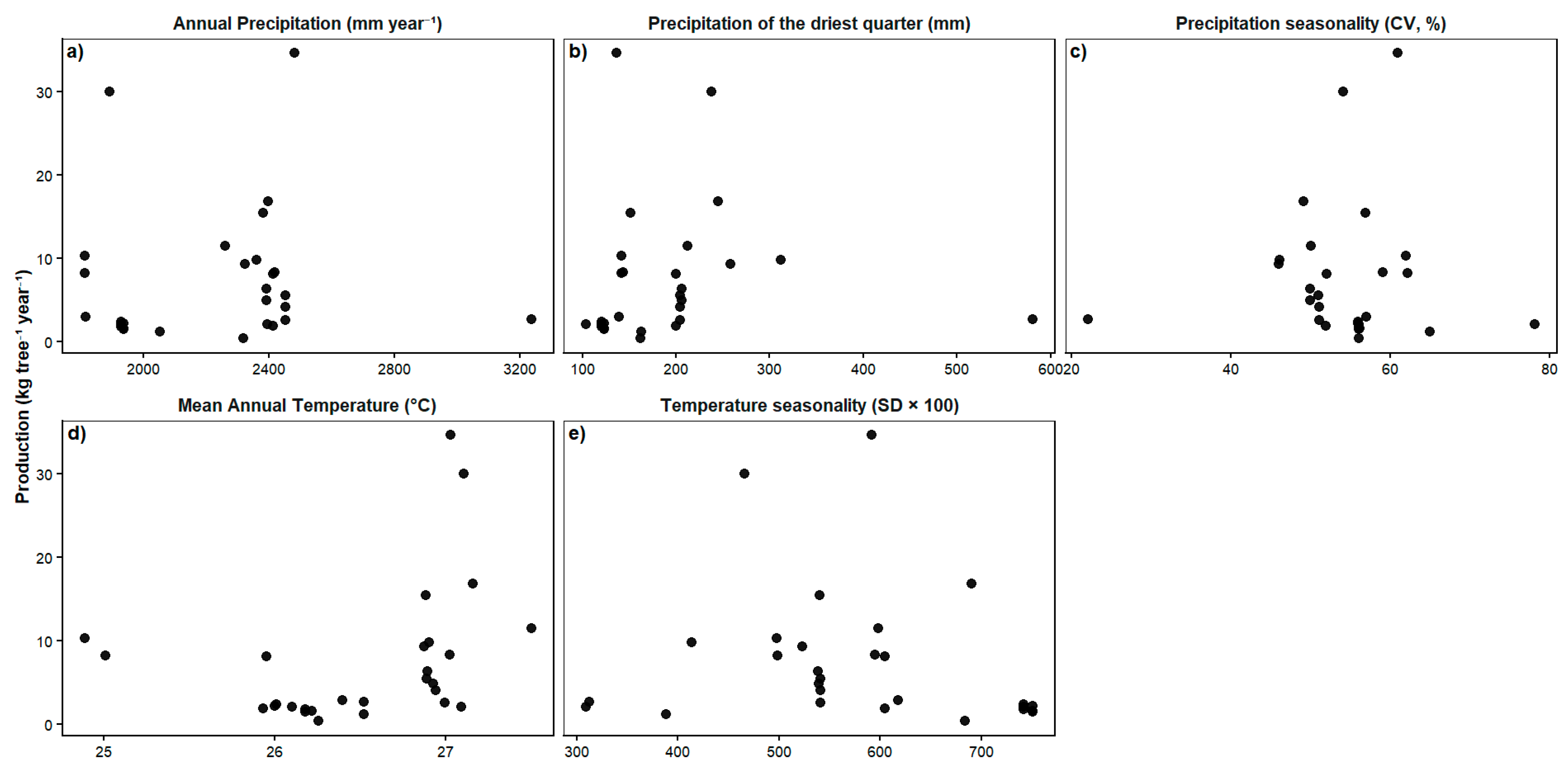

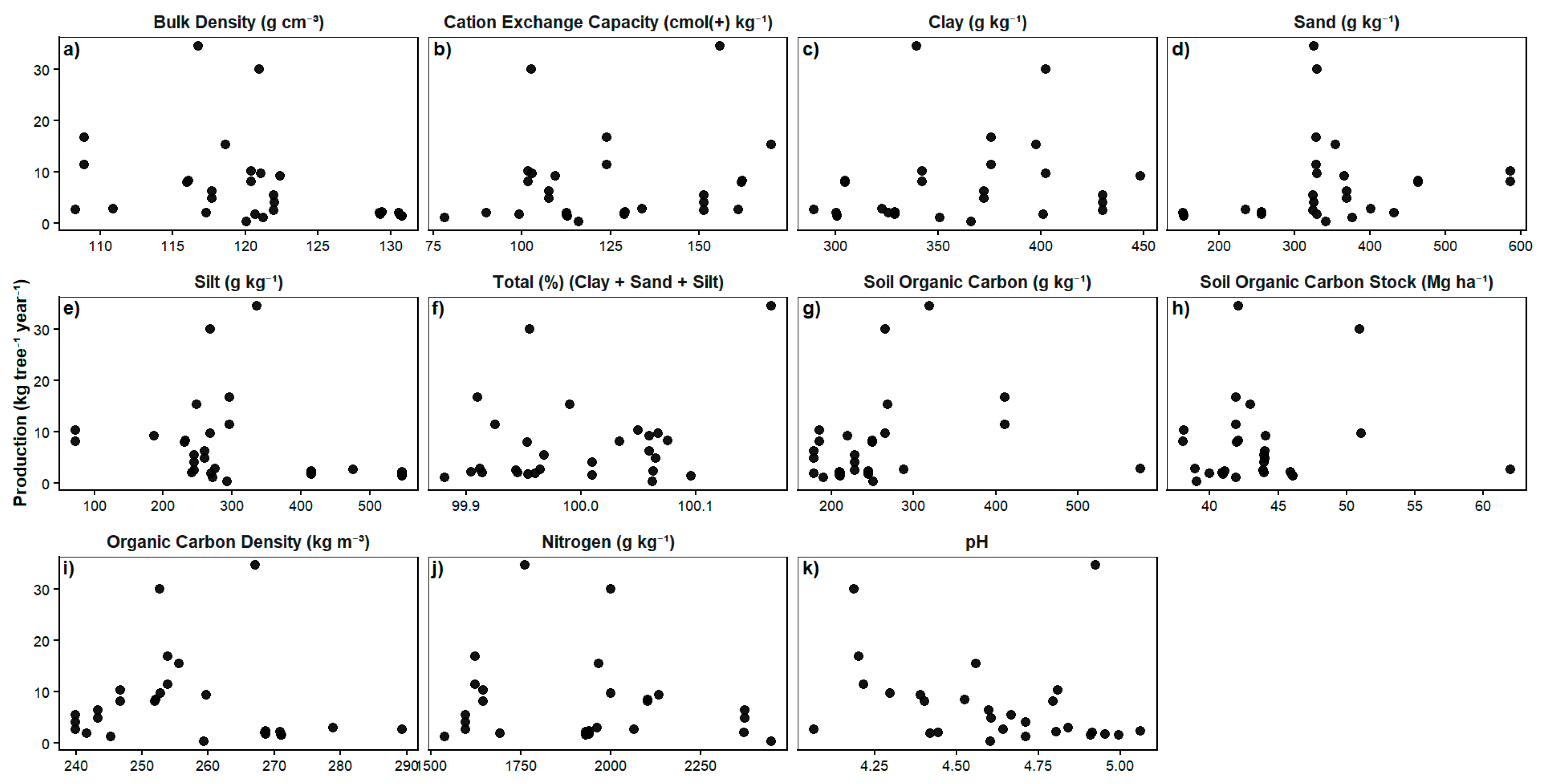

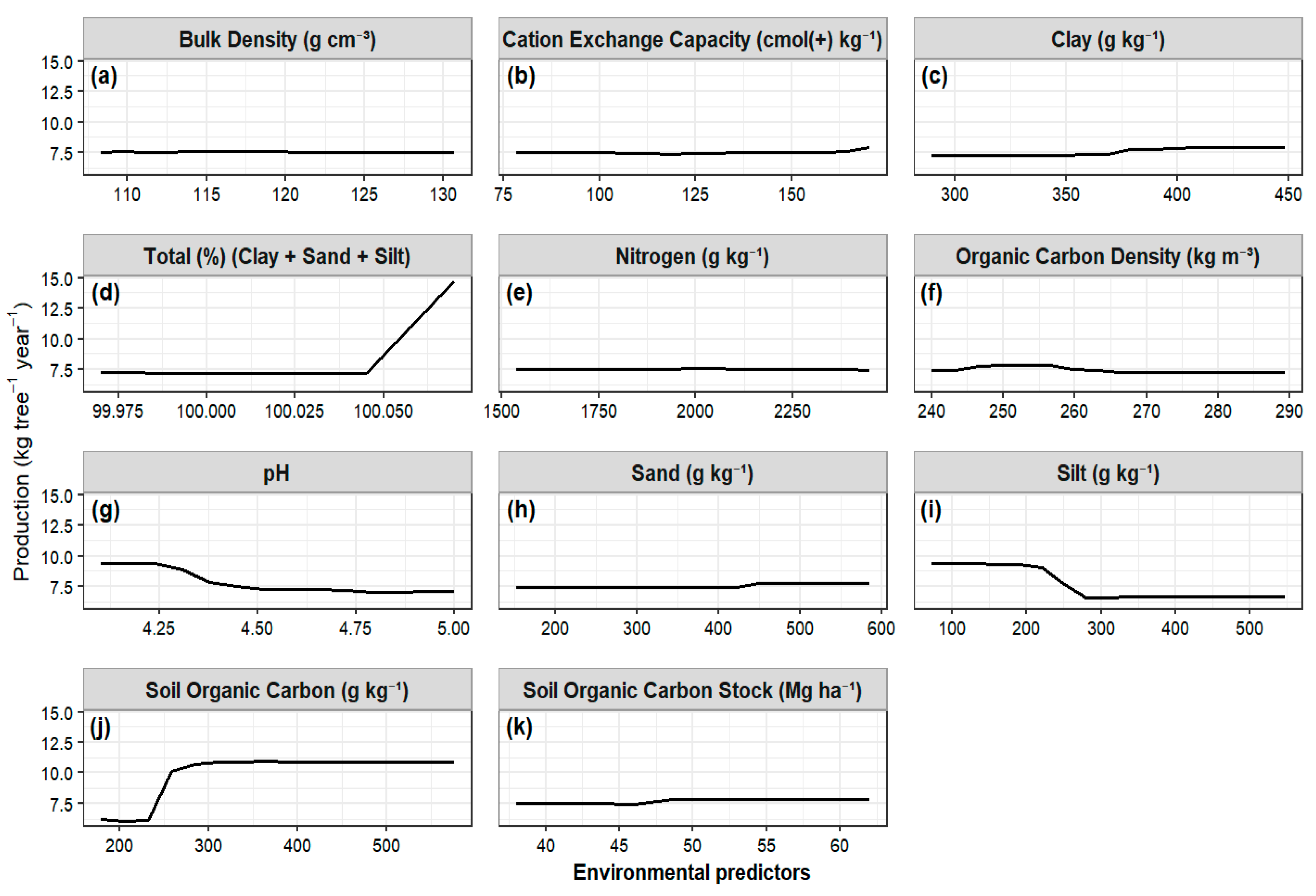

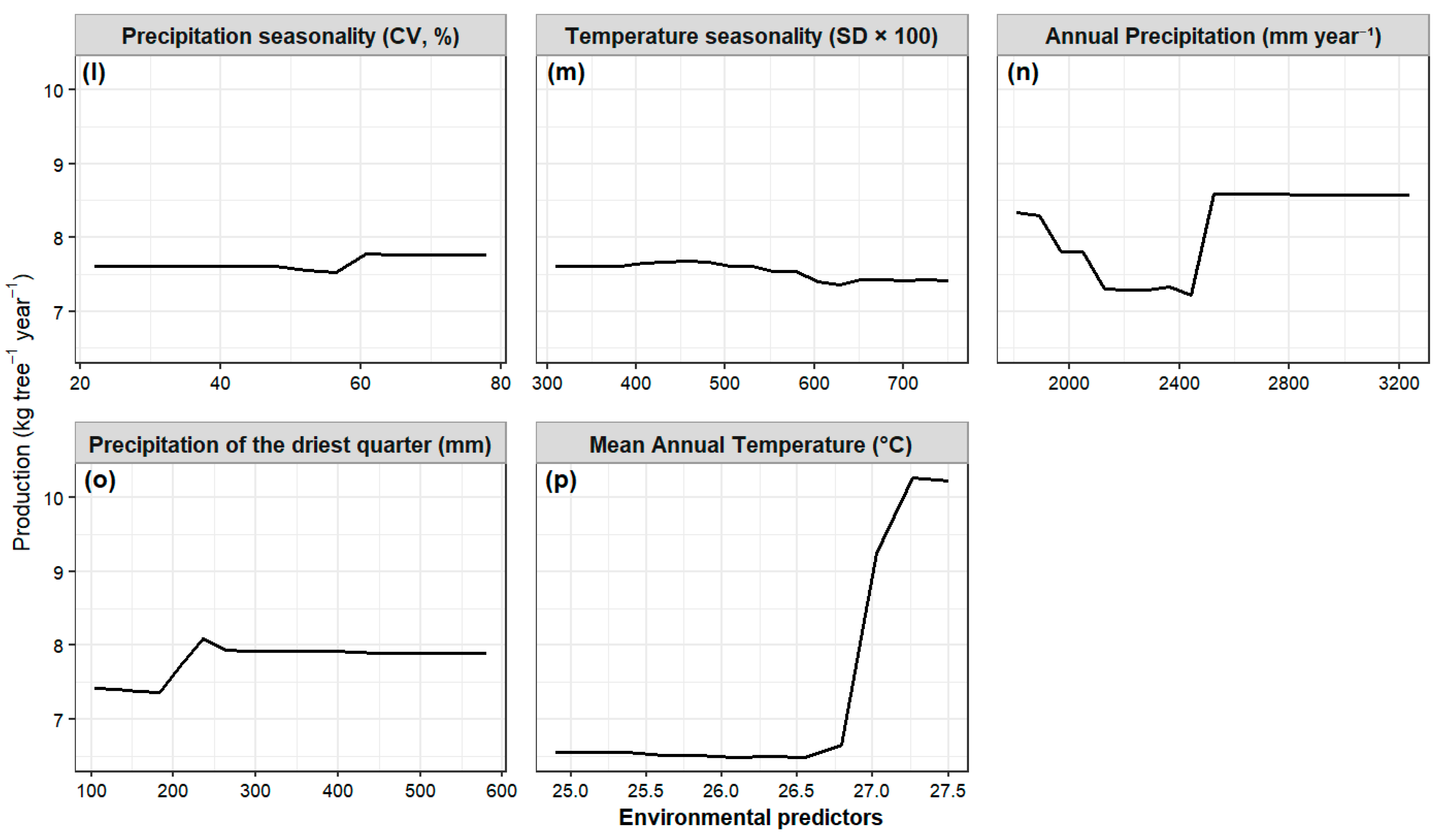

Relationship Between Fruit Production and Environmental Variables

4. Discussion

Influence of Climatic Factors and Forest Type

Importance of Edaphic Factors

Model Performance and Ecological Implications

Model Performance and Methodological Considerations

Implications for Management, Conservation, and Climate

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Baccini, A.; Walker, W.; Carvalho, L.; Farina, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Houghton, R. A. Tropical forests are a net carbon source based on aboveground measurements of gain and loss. Science 2017, 358, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, O. C.; Cunha, J. M. D.; Campos, M. C. C.; Brito Filho, E. G. D.; Pereira, M. G.; Silva, G. A. D.; Santos, L. A. C. D. Radicular biomass and organic carbon of the soil in forest formations in the southern amazonian mesoregion. Revista Árvore 2021, 45, e4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. L; Lewis, S. L.; Sullivan, M. J.; Prado, P. I.; Ter Steege, H.; Barbier, N.; Irume, M. V. Consistent patterns of common species across tropical tree communities. Nature 2024, 625, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A. L.; Norby, R. J.; Andersen, K. M.; Valverde-Barrantes, O.; Fuchslueger, L.; Oblitas, E.; Quesada, C. A. Fine-root dynamics vary with soil depth and precipitation in a low-nutrient tropical forest in the Central Amazonia. Plant-Environment Interactions 2020, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. A.; Clark, D. B.; Oberbauer, S. F. Field-quantified responses of tropical rainforest aboveground productivity to increasing CO2 and climatic stress, 1997–2009. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2013, 118, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lourdes Pinheiro Ruivo, M.; de Andrade Cunha, D.; da Silva Castro, R. M.; Lopes, E. L. N.; Leal Matos, D. C.; de Oliveira, R. D. Igapó ecosystem soils: features and environmental importance. In Igapó (Black-water flooded forests) of the Amazon Basin; Springer International Publishing: Randall W. Cham, 2018; pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, S. F.; Benigno Paes, J.; Chaves Arantes, M. D.; Martinez Lopez, Y.; Fassina Brocco, V. Análise física e avaliação do efeito antifúngico dos óleos de andiroba, copaíba e pinhão-manso. Floresta 2018, 48, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L. S.; Pereira, A. M.; Farias, M. D. S.; Oliveira, R. L.; Junior, D.; Quaresma, J. N. N. Valorization of Andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) residues through optimization of alkaline pretreatment to obtain fermentable sugars. BioResources 2020, 15, 894–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A. J.; de Queiroz Guerra, F. G. P. Aspectos econômicos da cadeia produtiva dos óleos de andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) e copaíba (Copaifera multijuga Hayne) na Floresta Nacional do Tapajós–Pará. Floresta 2010, 40, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, K. I. P.; Silva, R. C.; de Santana Botelho, A.; de Almeida Araújo, L.; Caldas, I. F. R.; de Souza Pinheiro, W. B. Use of Carapa guianensis Aubl. agro-industrial waste as an alternative for obtaining bioproducts. Comptes Rendus. Chimie 2025, 28, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, A. E.; Razafindratsima, O. H.; Rakotonirina, P.; Wright, P. C. Fruiting phenology is linked to rainfall variability in a tropical rain forest. Biotropica 2018, 50, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D. P.; Tobias, J. A.; Sheil, D.; Meijaard, E.; Laurance, W. F. Maintaining ecosystem function and services in logged tropical forests. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2014, 29, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Tan, Z.; Pinel, S.; Xu, D.; Amaral, J. H. F.; Fassoni-Andrade, A. C.; Bisht, G. Drivers and impacts of sediment deposition in Amazonian floodplains. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, I. D. K.; Camargo, J. L. C.; Sampaio, P. D. T. B. Sementes e plântulas de andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl. e Carapa procera DC): aspectos botânicos, ecológicos e tecnológicos. Acta amazônica 2002, 32, 647–647. [Google Scholar]

- Fick, S. E.; Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F. D. A.; Nobre, C. A. R. L. O. S.; Genin, C. A. R. O. L. I. N. A.; Frasson, C. M. R.; Fernandes, D. A.; Silva, H. A. R. L. E. Y.; FOLHES, R. V. N. E. R. Bioeconomy for the Amazon: concepts, limits, and trends for a proper definition of the tropical forest biome. In São Paulo: WRI Brasil; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garwood, N. C.; Metz, M. R.; Queenborough, S. A.; Persson, V.; Wright, S. J.; Burslem, D. F.; Valencia, R. Seasonality of reproduction in an ever-wet lowland tropical forest in Amazonian Ecuador. Ecology 2023, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugaasen, T.; Peres, C. A. Floristic, edaphic and structural characteristics of flooded and unflooded forests in the lower Rio Purús region of central Amazonia, Brazil. Acta Amazonica 2006, 36, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, R. J.; Cameron, S. E.; Parra, J. L.; Jones, P. G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W. J.; Piedade, M. T. F.; Wittmann, F.; Schöngart, J.; Parolin, P. Amazonian floodplain forests: Ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klimas, C. A.; Kainer, K. A.; Wadt, L. H. Population structure of Carapa guianensis in two forest types in the southwestern Brazilian Amazon. Forest Ecology and Management 2007, 250, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, C. A.; Kainer, K. A.; Wadt, L. H.; Staudhammer, C. L.; Rigamonte-Azevedo, V.; Correia, M. F.; da Silva Lima, L. M. Control of Carapa guianensis phenology and seed production at multiple scales: a five-year study exploring the influences of tree attributes, habitat heterogeneity and climate cues. Journal of Tropical Ecology 2012, 28, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, C. A.; Wadt, L. H. D. O.; Castilho, C. V. D.; Lira-Guedes, A. C.; da Costa, P.; da Fonseca, F. L. Variation in Seed Harvest Potential of Carapa guianensis Aublet in the Brazilian Amazon: A Multi-Year, Multi-Region Study of Determinants of Mast Seeding and Seed Quantity. Forests 2021, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A. F. L. D.; Campos, M. C. C.; Silva, J. D. B.; Araújo, W. D. O.; Mantovanelli, B. C.; Souza, F. G. D.; Oliveira, F. P. D. The stability of aggregates in different Amazonian agroecosystems is influenced by the texture, acidity, and availability of Ca and Mg in the soil. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londres, M.; Schulze, M.; Staudhammer, C. L.; Kainer, K. A. Population structure and fruit production of Carapa guianensis (Andiroba) in Amazonian floodplain forests: Implications for community-based management. Tropical Conservation Science 2017, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, J. D. P.; Ferreira, L. M. M.; Martins, G. C.; Nascimento, D. G.; Dílson Gomes Nascimento, S. A. Produção, biometria de frutos e sementes e extração do óleo de andiroba. Carapa guianensis Aublet.) sob manejo comunitário em Parintins, AM 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, I.; Peres, C. A.; Morellato, L. P. C. Continental-scale patterns and climatic drivers of fruiting phenology: A quantitative Neotropical review. Global and Planetary Change 2017, 148, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, D. M.; Kobe, R. K. Fruit production is influenced by tree size and size-asymmetric crowding in a wet tropical forest. Ecology and Evolution 2019, 9, 1458–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnini, F.; Muñiz-Miret, N. Vegetation and soils of tidal floodplains of the Amazon estuary: a comparison of várzea and terra firme forests in Pará, Brazil. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 1999, 11, 420–437. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43582545.

- Nascimento, G. O.; Souza, D. P.; Santos, A. S.; Batista, J. F.; Rathinasabapathi, B.; Gagliardi, P. R.; Gonçalves, J. F. Lipidomic profiles from seed oil of Carapa guianensis Aubl. and Carapa vasquezii Kenfack and implications for the control of phytopathogenic fungi. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 129, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I. D. S. D. S.; Moragas Tellis, C. J.; Chagas, M. D. S. D. S.; Behrens, M. D.; Calabrese, K. D. S.; Abreu-Silva, A. L.; Almeida-Souza, F. Carapa guianensis Aublet (Andiroba) Seed Oil: Chemical Composition and Antileishmanial Activity of Limonoid-Rich Fractions. BioMed Research International 2018, 2018, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolin, P.; Oliveira, A. C.; Piedade, M. T. F.; Wittmann, F.; Junk, W. J. Pioneer trees in Amazonian floodplains: three key species form monospecific stands in different habitats. Folia Geobotanica 2002, 37, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastana, D. N. B.; Modena, É. D. S.; Wadt, L. H. D. O.; Neves, E. D. S.; Martorano, L. G.; Lira-Guedes, A. C.; Guedes, M. C. Strong El Niño reduces fruit production of Brazil-nut trees in the eastern Amazon. Acta Amazonica 2021, 51, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penido, C.; Conte, F. P.; Chagas, M. S. S.; Rodrigues, C. A. B.; Pereira, J. F. G.; Henriques, M. G. M. O. Antiinflammatory effects of natural tetranortriterpenoids isolated from Carapa guianensis Aublet on zymosan-induced arthritis in mice. Inflammation Research 2006, 55, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, R.; Venter, M.; Aragon-Osejo, J.; González-del-Pliego, P.; Hansen, A. J.; Watson, J. E.; Venter, O. Tropical forests are home to over half of the world’s vertebrate species. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2022, 20, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, L.; de Sousa, L. M.; Batjes, N. H.; Heuvelink, G. B. M.; Kempen, B.; Ribeiro, E.; Rossiter, D. SoilGrids 2.0: Producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. Soil. 2021, 7, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Vallejo, E.; Pena-Claros, M.; Bongers, F.; Toledo, M.; Poorter, L. Effects of Amazonian Dark Earths on growth and leaf nutrient balance of tropical tree seedlings. Plant and Soil. 2015, 396, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing . R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Raspe, D.; Silva, I. D.; Silva, E. D.; Saldana, M.; Silva, C. D.; Cardozo-Filho, L. Valorization of Carapa guianensis Aubl. seeds treated by compressed n-propane. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2024, 96, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. N.; Cunha, H. F. A.; Lira-Guedes, A. C.; Gomes, S. C. P.; Guedes, M. C. Saberes tradicionais em uma unidade de conservação localizada em ambiente periurbano de várzea: etnobiologia da andirobeira (Carapa guianensis Aublet). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 2014, 9, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Conant, R. T.; Paul, E. A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant and soil. 2002, 241, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, P.; Pierce, A. R.; Laird, S. A.; Guillen, A. Tapping the Green Market: Certification and Management of Non-Timber Forest Products; Earthscan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Slik, J. F.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Aiba, S. I.; Alvarez-Loayza, P.; Alves, L. F.; Ashton, P.; Hurtado, J. An estimate of the number of tropical tree species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 7472–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. K.; de Assis Oliveira, F.; Gholz, H. L.; Baima, A. Soil carbon stocks after forest conversion to tree plantations in lowland Amazonia, Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management 2002, 164, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D. G.; Stahle, D. W.; Torbenson, M.; Barbosa, A. C. M. C.; Howard, I.; Feng, S.; Villalba, R. Multi-decadal changes in wet season precipitation totals over the eastern Amazon. AGU Fall Meeting 2019, 2019, December; AGU. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, R. D. A. D.; Moura, V.; Paloschi, R. A.; Aguiar, R. G.; Webler, A. D.; Borma, L. D. S. Assessing drought response in the Southwestern Amazon forest by remote sensing and in situ measurements. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanner, G. C.; Gimenez, B. O.; Wright, C. L.; Menezes, V. S.; Newman, B. D.; Collins, A. D.; Warren, J. M. Dry season transpiration and soil water dynamics in the Central Amazon. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, H.; Costa, P. D.; Kamiski, P. E. Estrutura, distribuição espacial e produção de sementes de andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) no sul do estado de Roraima. Ciência Florestal 2009, 19, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, H. Variações na produção de sementes e recomendações para o manejo de uso múltiplo da andirobeira. Pesquisa Florestal Brasileira 2017, 37, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrego, L. E.; Galeano, A.; Peñuela, C.; Sánchez, M.; Toro, E. Climate-related phenology of Mauritia flexuosa in the Colombian Amazon. Plant Ecology 2016, 217, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velastegui-Montoya, A.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Peña-Villacreses, G.; de Lima, A.; Herrera-Franco, G. Land use and land cover in tropical forest: global research. Forest 2022, 13, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadt, L. H.; Kainer, K. A.; Gomes-Silva, D. A. Population structure and nut yield of a Bertholletia excelsa stand in Southwestern Amazonia. Forest Ecology and Management 2005, 211, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzeler, A. M. V.; Júnior, S. M. A.; Gomes, J. T.; Gouveia, E. H. H.; Henriques, H. Y. B.; Chaves, R. H.; Tuji, F. M. Therapeutic effect of andiroba oil (Carapa guianensis Aubl.) against oral mucositis: an experimental study in golden Syrian hamsters. Clinical Oral Investigations 2018, 22, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, F.; Schöngart, J.; Junk, W. J. Phytogeography, species diversity, community structure and dynamics of central Amazonian floodplain forests. In Amazonian floodplain forests: ecophysiology, biodiversity and sustainable management; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2010; pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, F.; Householder, E. Why rivers make the difference: A review on the phytogeography of forested floodplains in the Amazon Basin. Forest structure, function and dynamics in western Amazonia 2017, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, F.; Householder, J. E.; Piedade, M. T. F.; Schöngart, J.; Demarchi, L. O.; Quaresma, A. C.; Junk, W. J. A review of the ecological and biogeographic differences of Amazonian floodplain forests. Water 2022, 14, 3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarkent, Ç.; Oncel, S. S. Recent progress in microalgal squalene production and its cosmetic application. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2022, 27, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | State | Municipality | Study area | Forest type | Longitude (°) | Latitude (°) | Number of trees | Mean DBH (cm) | Mean fruit production (kg tree⁻¹ year⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dias (2001) | Pará | Belterra | Floresta Nacional do Tapajós” (FLONA Tapajós) | Terra firme | 54°45'0.00"W | 2°40'0.12"S | 192 | 41.5 | 10.29 |

| Dias (2001) | Pará | Belterra | Floresta Nacional do Tapajós” (FLONA Tapajós) | Terra firme | 50°0'0.00"W | 4°10'0.12"S | 137 | 41.3 | 9.67 |

| Dias (2001) | Pará | Belterra | Floresta Nacional do Tapajós” (FLONA Tapajós) | Terra firme | 54°45'0.00"W | 2°40'0.12"S | 86 | 37.4 | 8.17 |

| Plowden (2004). | Pará | Nova Esperança do Piriá | Aldeia de Tekohaw | Terra firme | 46°33'25.30"W | 2°37'35.35"S | 46 | 39.4 | 1.2 |

| Mellinger (2006) | Amazonas | Mara | Reserva de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Amanã | Igapó | 64°38'24.00"W | 2°31'42.00"S | 42 | 45.4 | 2.7 |

| Lima (2007) | Acre | Rio Branco | Reserva Florestal da Embrapa Acre | Baixio | 67°44'28.00"W | 9°58'29.00"S | 26 | N.A. | 1.48 |

| Lima (2007) | Acre | Rio Branco | Reserva Florestal da Embrapa Acre | Terra firme | 67°44'28.00"W | 9°58'29.00"S | 23 | N.A. | 2.16 |

| Pena (2007) | Pará | Breu_Branco | Empresa Izabel medeiros do Brasil | Terra firme | 49°18'31.90"W | 3°27'2.80"S | 50 | 44.95 | 2.12 |

| Wadt et al.(2008) | Acre | Rio Branco | Reserva Florestal da Embrapa Acre | Terra firme | 67°44'28.00"W | 9°58'29.00"S | 118 | 25 | 1.6 |

| Guedes et al.(2008) | Amapá | Mazagão | Escola Família Agrícola (EFA) doCarvão | Várzea | 51°22'0.00"W | 0°10'60.00"S | 6 | 10 | 15.4 |

| Lima et al.(2009) | Amapá | Macapá | APA da Fazendinha | Várzea | 51°7'41.78"W | 0°3'10.39"S | 30 | 44.4 | 34.6 |

| Gomes (2010) | Amapá | Mazagão | Reserva florestal da Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária | Terra firme | 51°58'0.00"W | 0°40'0.00"S | 34 | 38.1 | 4.9 |

| Gomes (2010) | Amapá | Mazagão | Reserva florestal da Empresa_Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária | Várzea | 51°58'0.00"W | 0°40'0.00"S | 12 | 23.7 | 6.35 |

| Klimas (2011) | Acre | na | Reserve of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) | Terra firme | 67°42'19.00"W | 10°1'28.00"S | 168 | 37.5 | 1.77 |

| Klimas (2011) | Acre | na | Reserve of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) | Igapó | 67°42'19.00"W | 10°1'28.00"S | 184 | 37.5 | 2.33 |

| Nascimento (2013) | Amazonas | Parintins | Comunidade N. S. do Rosário | Terra firme | 56°41'36.60"W | 2°42'38.52"S | 15 | N.A. | 16.8 |

| Pinto (2013) | Amazonas | Manaus | Reserva Florestal Ducke | Terra firme | 59°58'59.88"W | 2°55'0.12"S | 30 | N.A. | 9.31 |

| Pinto (2013) | Amazonas | Manaus | Reserva Florestal Ducke | Terra firme | 59°52'59.88"W | 3°1'0.12"S | 30 | N.A. | 9.31 |

| Marques (2012) | Roraima | Sao Joao da Baliza | Área de reserva legal de uma propirdade particular | Várzea | 59°54'41.00"W | 0°57'2.00"S | 73 | 47.75 | 9.76 |

| Klimas (2012) | Acre | na | Forest reserve of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) | Terra firme | 67°42'19.00"W | 10°1'28.00"S | 352 | 32.5 | 2.06 |

| Barros (2014) | Amapá | Laranjal do Jarí | Reserva Extrativista Rio Cajari (RESEX) Cajari) | Terra firme | 52°18'19.01"W | 0°33'42.98"S | 62 | N.A. | 1.84 |

| Barros (2014) | Amapá | Mazagão | Estação Experimental da Embrapa | Várzea | 51°17'20.00"W | 0°6'54.00"S | 16 | N.A. | 8.09 |

| da Silva (2015) | Amapá | Mazagão | Campo_Experimental_do_Mazagão_da_Embrapa | Várzea | 51°17'20.00"W | 0°6'54.00"S | 16 | 30 | 8.35 |

| Martins (2016) | Pará | Almeirim | Cafezal /Paru | Terra firme | 53°9'34.85"W | 1°9'55.76"S | 20 | 40.7 | 2.9 |

| Tonini (2017) | Roraima | São João da Baliza | Terra firme | 59°54'41.00"W | 0°57'2.00"S | 121 | 20 | 29.99 | |

| Londres (2017) | Pará | Gurupá | Reserva de desemvolvimento Sustentavel (RDS) Itatupã-Baquiá | Terra firme | 51°21'35.64"W | 0°34'48.36"S | 67 | 55 | 5.5 |

| Londres (2017) | Pará | Gurupá | Reserva de desemvolvimento Sustentavel (RDS) Itatupã-Baquiá | Baixio | 51°21'35.64"W | 0°34'48.36"S | 120 | 35 | 2.6 |

| Londres (2017) | Pará | Gurupá | Reserva de desemvolvimento Sustentavel (RDS) Itatupã-Baquiá | Restinga | 51°21'35.64"W | 0°34'48.36"S | 40 | 28 | 4.1 |

| Lourenço et al..(2017) | Pará | Gurupá | Reserva de desemvolvimento Sustentavel (RDS) Itatupã-Baquiá | Terra firme | 56°41'36.71"W | 2°42'38.53"S | 21 | 55 | 11.47 |

| Correa et al. (2020) | Amapá | Porto Grande | Projeto de Assentamento Nova Canaã | Terra firme | 51°40'20.86"W | 0°35'12.16"S | 26 | N.A. | 0.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).