Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

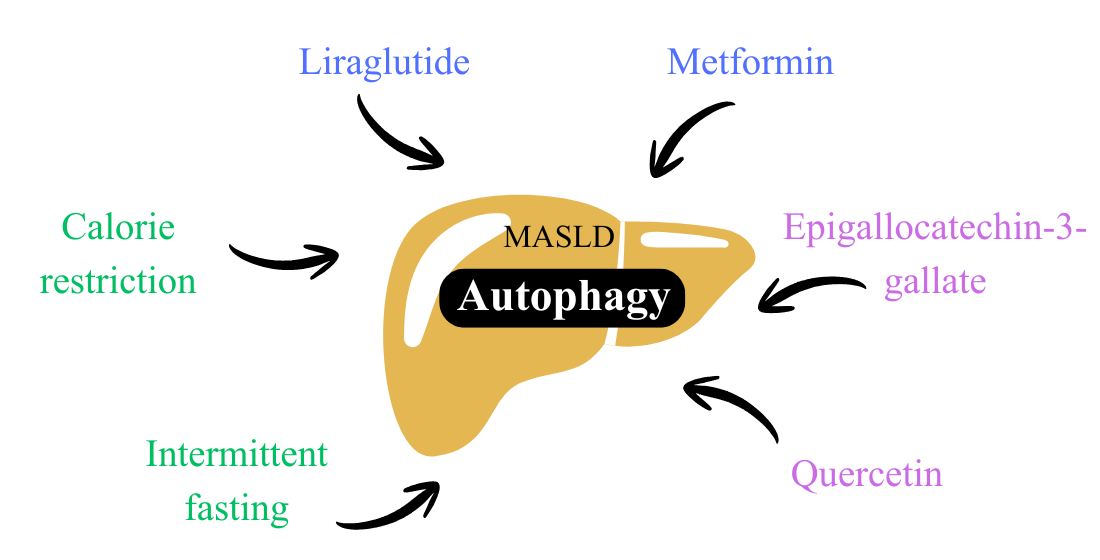

1.1 Pharmacological interventions

1.1.1 GLP-1 analogs

1.1.2 Metformin

1.2. Calorie restriction

1.3. Intermittent fasting

1.4. Bioactive compounds

1.4.1 Epigallocatechin-3-gallate

1.4.2 Quercetin

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ATG5 | Autophagy-related 5 |

| ATG7 | Autophagy-related 7 |

| ATG12 | Autophagy-related 12 |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CMA | Chaperone-mediated autophagy |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FFA | Free fatty acid |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| IF | Intermittent fasting |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| LAMP1 | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 |

| LAMP2A | Lysosomal-associated membrane protein type 2A |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3 |

| LC3-I | Form I of LC3 |

| LC3-II | Form II of LC3 |

| LC3-II/I | Ratio between forms II and I of LC3 |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| NAS | NAFLD Activity Score |

| ox-LDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| p62 | Sequestosome-1 |

| PA | Palmitic acid |

| p-AKT | Phospho-AKT |

| p-AMPK | Phospho-AMPK |

| Parkin | Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin protein ligase |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| Pink-1 | PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 protein |

| p-mTOR | Phospho-mTOR |

| p-PI3K | Phospho-PI3K |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-PCR | Real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TFEB | Transcription factor EB |

| ULK1 | Unc-51–like kinase 1 |

| WB | Western blot |

References

- Yanai, H; Yoshida, H. Metabolic-Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease—Its Pathophysiology, Association with Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Disease, and Treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(20), 15493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L; Wang, X; Chen, K. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2024, 35(2), 112–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W-K; Chuah, K-H; Rajaram, RB; Goh, K-L. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): a state-of-the-art review. J Obes Metab Syndr 2023, 32(3), 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M; Sanyal, AJ; George, J; Sanyal, A; Neuschwander-Tetri, B; Tiribelli, C; Kleiner, DE; Brunt, E; Bugianesi, E; Yki-Järvinen, H; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 2020, 73(1), 202–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangro, P; Cubero, FJ; Trautwein, C. Metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): an update of the recent advances in pharmacological treatment. J Physiol Biochem 2023, 79(4), 869–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, RO; Salles, JE; Oliveira, CP; Cotrim, HP; Carvalho, M; Borges, JL; de Paiva, A; Lottenberg, A; Bertoluci, MC. Brazilian evidence-based guideline for screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in adult individuals with overweight or obesity: a joint position statement. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2023, 67(6), e000646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zechner, R; Madeo, F; Kratky, D. Cytosolic lipolysis and lipophagy: two sides of the same coin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18(11), 671–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluchowski, NL; Becuwe, M; Walther, TC; Farese, RV. Lipid droplets and liver disease: from basic biology to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 14(6), 343–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubek, P; Rychter, AM; Ratajczak, AE; Szymczak-Tomczak, A; Zawada, A; Eder, P; Dobrowolska, A; Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. Autophagy alterations in obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: the evidence from human studies. Intern Emerg Med 2024, 19(5), 1207–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, SG; Selvaraj, A; Thomas, G. MTOR Complex1–S6K1 signaling: at the crossroads of obesity, diabetes and cancer. Trends Mol Med 2007, 13(6), 252–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, SH; Frigerio, F; Watanabe, M; Picard, F; Joaquin, M; Sticker, M; Fumagalli, S; Allegrini, PR; Kozma, SC; Auwerx, J; et al. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature 2004, 431(7005), 200–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, RA; Sabatini, DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168(6), 960–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H; Zhang, J; Lin, C; Zhang, L; Liu, B; Ouyang, L. Targeting autophagy-related protein kinases for potential therapeutic purpose. Acta Pharm Sin B 2020, 10(4), 569–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y; Ao, N; Yang, J; Wang, X; Jin, S; Du, J. The preventive effect of liraglutide on the lipotoxic liver injury via increasing autophagy. Ann Hepatol 2020, 19(1), 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifari, F; Manfrini, R; Dei Cas, M; Berra, C; Siano, M; Zuin, M; Paroni, R; Folli, F. Multiple target tissue effects of GLP-1 analogues on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Pharmacol Res 2018, 137, 219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T; Weng, J. Hepatic functions of GLP-1 and its based drugs: current disputes and perspectives. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2016, 311(3), E620-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosal, S; Datta, D; Sinha, B. A meta-analysis of the effects of glucagon-like-peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP1-RA) in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Sci Rep 2021, 11(1), 22063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z; Yuan, T; Hu, X; Shi, H; Mo, X; Chen, X. Liraglutide protects against inflammatory stress in non-alcoholic fatty liver by modulating Kupffer cells M2 polarization via cAMP-PKA-STAT3 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 510(1), 20–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y; Yang, P; Li, Z; Chen, Y; Zhang, L; Liu, T; Xie, Z; Zhou, S. Liraglutide Improves Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease In Diabetic Mice By Modulating Inflammatory Signaling Pathways. Drug Des Devel Ther 2019, 13, 4065–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, PN; Buchholtz, K; Cusi, K; Linder, M; Okanoue, T; Ratziu, V; Sanyal, AJ; Sejling, A-S; Harrison, SA. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Subcutaneous Semaglutide in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2021, 384(12), 1113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, S; Tabrizi, R; Nowrouzi-Sohrabi, P; Jalali, M; Atkin, SL; Alipour, S; Jamialahmadi, T; Sahebkar, A. GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Effects on Lipid and Liver Profiles in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 2021, 8936865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y; Ji, L; Zhu, C; Xiao, Y; Zhang, J; Lu, J; Yin, J; Wei, L. Liraglutide Alleviates Hepatic Steatosis by Activating the TFEB-Regulated Autophagy-Lysosomal Pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 602574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q; Sha, S; Sun, L; Zhang, J; Dong, M. GLP-1 analogue improves hepatic lipid accumulation by inducing autophagy via AMPK/mTOR pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 476(4), 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z; Huang, L; Chen, J; Chen, T; Kong, D; Wei, Q; Chen, Q; Deng, B; Li, Y; Zhong, S. Liraglutide Improves Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Diabetic Mice by Activating Autophagy Through AMPK/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2024, 17, 575–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W; Ju, L; Qiu, M; Xie, Q; Chen, Y; Shen, W; Sun, W; Wang, W; Tian, J. Liraglutide ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by enhancing mitochondrial architecture and promoting autophagy through the SIRT1/SIRT3–FOXO3a pathway. Hepatol Res 2016, 46(9), 933–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S; Shah, RB; Singhal, S; Dutta, SB; Bansal, S; Sinha, S; Haque, M. Metformin: a review of potential mechanism and therapeutic utility beyond diabetes. Drug Des Devel Ther 2023, 17, 1907–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, SD; Farrelly, FV; Brennan, PN. Role of anti-diabetic medications in the management of MASLD. Frontline Gastroenterol 2025, 16(3), 239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugianesi, E; Gentilcore, E; Manini, R; Natale, S; Vanni, E; Villanova, N; David, E; Rizzetto, M; Marchesini, G. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Metformin versus Vitamin E or Prescriptive Diet in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2005, 100(5), 1082–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, R; Lutchman, G; Kleiner, DE; Ricks, M; Feld, JJ; Borg, BB; Modi, A; Nagabhyru, P; Sumner, AE; Liang, TJ. Clinical trial: pilot study of metformin for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008, 29(2), 172–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D; Ma, Y; Liu, J; Deng, Y; Zhou, B; Wen, Y; Li, M; Wen, D; Ying, Y; Luo, S. Metformin Alleviates Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in a Mouse Model of High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Promoting Transcription Factor EB-Dependent Autophagy. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 689111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C; Fang, L; Zhang, H; Zhang, W-S; Li, X-O; Du, S-Y. Metformin Induces Autophagy via the AMPK-mTOR Signaling Pathway in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Cancer Manag Res 2020, 12, 5803–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Most, J; Tosti, V; Redman, LM; Fontana, L. Calorie restriction in humans: an update. Ageing Res Rev 2017, 39, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, RJ; Anderson, RM; Johnson, SC; Kastman, EK; Kosmatka, KJ; Beasley, TM; Allison, DB; Cruzen, C; Simmons, HA; Kemnitz, JW. Caloric Restriction Delays Disease Onset and Mortality in Rhesus Monkeys. Science 2009, 325(5937), 201–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, RJ; Beasley, TM; Kemnitz, JW; Johnson, SC; Weindruch, R; Anderson, RM. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simancas-Racines, D; Annunziata, G; Verde, L; Fascì-Spurio, F; Reytor-González, C; Muscogiuri, G; Frias-Toral, E; Barrea, L. Nutritional Strategies for Battling Obesity-Linked Liver Disease: the role of medical nutritional therapy in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (masld) management. Curr Obes Rep 2025, 14(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutoukidis, DA; Astbury, NM; Tudor, KE; Morris, E; Henry, JA; Noreik, M; Jebb, SA; Aveyard, P. Association of Weight Loss Interventions With Changes in Biomarkers of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA Intern Med 2019, 179(9), 1262–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M; Macho-González, A; Diaz, A; Lindenau, K; Santiago-Fernández, O; Zeng, M; Massey, AC; de Cabo, R; Kaushik, S; Cuervo, AM. Calorie restriction and calorie-restriction mimetics activate chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121(26), e2317945121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S; Jiang, J; Zhang, G; Bu, Y; Zhang, G; Zhao, X. Resveratrol and caloric restriction prevent hepatic steatosis by regulating SIRT1-autophagy pathway and alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress in high-fat diet-fed rats. PLoS One 2017, 12(8), e0183541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasim, I; Majeed, CN; DeBoer, MD. Intermittent Fasting and Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2022, 14(3), 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z; Kong, AP-S; Wong, VW-S; Hui, HX. Intermittent fasting and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: the potential role of the gut-liver axis. Cell Biosci 2025, 15(1), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, MJ; Manoogian, ENC; Zadourian, A; Lo, H; Fakhouri, S; Shoghi, A; Wang, X; Fleischer, JG; Navlakha, S; Panda, S. Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metab 2020, 31(1), 92–104.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y; Liu, Y; Zhao, L; Zhou, Y. Effect of 5: 2 fasting diet on liver fat content in patients with type 2 diabetic with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2022, 20(8), 459–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johari, MI; Yusoff, K; Haron, J; Nadarajan, C; Ibrahim, KN; Wong, MS; Hafidz, MIA; Chua, BE; Hamid, N; Arifin, WN. A Randomised Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness and Adherence of Modified Alternate-day Calorie Restriction in Improving Activity of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1), 11232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, TO; Akyuz, EY; Karadag, DY; Yilmaz, Y; Eren, F. Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Liver Steatosis and Fibrosis, Serum FGF-21 and Autophagy Markers in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: a randomized controlled trial. Life 2025, 15(5), 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, R; Liu, B; Bensalem, J; Sargeant, TJ; Page, AJ; Wittert, GA; Hutchison, AT; Heilbronn, LK. Intermittent fasting activates markers of autophagy in mouse liver, but not muscle from mouse or humans. Nutrition 2022, 101, 111662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, L; De Masi, L; Sirignano, C; Maresca, V; Basile, A; Nebbioso, A; Rigano, D; Bontempo, P. Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG): pharmacological properties, biological activities and therapeutic potential. Molecules 2025, 30(3), 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janota, B; Janion, K; Bużek, A; Janczewska, E. Dietary Strategies in the Prevention of MASLD: a comprehensive review of dietary patterns against fatty liver. Metabolites 2025, 15(8), 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefer, M; Petrovic, A; Roguljic, LK; Kolaric, TO; Kizivat, T; Wu, CH; Tabll, AA; Smolic, R; Vcev, A; Smolic, M. Green Tea Polyphenol (-)-Epicatechin Pretreatment Mitigates Hepatic Steatosis in an In Vitro MASLD Model. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46(8), 8981–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J; Wang, S; Zhang, T; Zi, M; Wang, S; Zhang, Q. Green tea epigallocatechin gallate attenuate metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease by regulation of pyroptosis. Lipids Health Dis 2025, 24(1), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, I; Ortiz-Flores, M; Villarreal, F; Fonseca-Coronado, S; Ceballos, G; Meaney, E; Nájera, N. Is it possible to treat nonalcoholic liver disease using a flavanol-based nutraceutical approach? Basic and clinical data. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2022, 33(6), 703–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C; Song, H-D; Son, Y; Cho, YK; Ahn, S-Y; Jung, Y-S; Yoon, YC; Kwon, SW; Lee, Y-H. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Reduces Visceral Adiposity Partly through the Regulation of Beclin1-Dependent Autophagy in White Adipose Tissues. Nutrients 2020, 12(10), 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J; Farah, BL; Sinha, RA; Wu, Y; Singh, BK; Bay, B-H; Yang, CS; Yen, PM. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG), a Green Tea Polyphenol, Stimulates Hepatic Autophagy and Lipid Clearance. PLoS One 2014, 9(1), e87161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S-N; Kwon, H-J; Akindehin, S; Jeong, H; Lee, Y-H. Effects of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate on Autophagic Lipolysis in Adipocytes. Nutrients 2017, 9(7), 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamarina, AB; Oliveira, JL; Silva, FP; Carnier, J; Mennitti, LV; Santana, AA; de Souza, GHI; Ribeiro, EB; do Nascimento, CMO; Lira, FS. Green Tea Extract Rich in Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Prevents Fatty Liver by AMPK Activation via LKB1 in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. PLoS One 2015, 10(11), e0141227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, F; Hadidi, M. Recent Advances in Potential Health Benefits of Quercetin. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16(7), 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W; Sun, C; Mao, L; Ma, P; Liu, F; Yang, J; Gao, Y. The biological activities, chemical stability, metabolism and delivery systems of quercetin: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2016, 56, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, M; Kadota, K; Shimono, K; Shirakawa, Y; Sato, H; Tozuka, Y. Enhanced solubility of quercetin by forming composite particles with transglycosylated materials. J Food Eng 2015, 149, 248–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, I; Sotiropoulou, M; Vailas, M; Kapetanakis, EI; Valsami, G; Tsaroucha, A; Schizas, D. Quercetin’s Potential in MASLD: investigating the role of autophagy and key molecular pathways in liver steatosis and inflammation. Nutrients 2024, 16(22), 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L; Liu, J; Mei, G; Chen, H; Peng, S; Zhao, Y; Yao, P; Tang, Y. Quercetin and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a review based on experimental data and bioinformatic analysis. Food Chem Toxicol 2021, 154, 112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P; Lin, H; Xu, Y; Zhou, F; Wang, J; Liu, J; Zhu, X; Guo, X; Tang, Y; Yao, P. Frataxin-Mediated PINK1–Parkin-Dependent Mitophagy in Hepatic Steatosis: the protective effects of quercetin. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018, 62(16), e1800164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miltonprabu, S; Tomczyk, M; Skalicka-Woźniak, K; Rastrelli, L; Daglia, M; Nabavi, SF; Alavian, SM; Nabavi, SM. Hepatoprotective effect of quercetin: from chemistry to medicine. Food Chem Toxicol 2017, 108, 365–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou, M; Katsaros, I; Vailas, M; Lidoriki, I; Papatheodoridis, GV; Kostomitsopoulos, NG; Valsami, G; Tsaroucha, A; Schizas, D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2021, 27(6), 319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z; Zhang, J; Li, M; Xing, Z; Li, X; Qing, J; Zhang, Y; Zhu, L; Qi, M; Zou, X. Mechanism of action of quercetin in regulating cellular autophagy in multiple organs of Goto-Kakizaki rats through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Front Med 2024, 11, 1442071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L; Gao, C; Yao, P; Gong, Z. Quercetin Alleviates High-Fat Diet-Induced Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Accumulation in the Liver: implication for autophagy regulation. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 607531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsaros, I; Sotiropoulou, M; Vailas, M; Papachristou, F; Papakyriakopoulou, P; Grigoriou, M; Kostomitsopoulos, N; Giatromanolaki, A; Valsami, G; Tsaroucha, A. The Effect of Quercetin on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and the Role of Beclin1, P62, and LC3: an experimental study. Nutrients 2024, 16(24), 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Model | Intervention | Effect on autophagy (In vivo) |

Effect on autophagy (In vitro) |

DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | MASLD: C57BL/6J mice fed HFD for 18 weeks, plus HepG2 cells and primary hepatocytes treated with PA |

In vivo: 0.4 mg/kg, once daily for 4 weeks; In vitro: 0.0001–0.0005 mM for 24h |

↑ ATG7 protein expression (WB), ↑ beclin 1 protein expression (WB), ↓ LC3-II protein expression (WB), ↓ p62 protein expression (WB), ↑ TFEB expression in the nuclear fraction (WB) in the liver | ↓ LC3-II protein expression (WB) and ↓ p62 protein expression (WB) | 10.3389/fcell.2020.602574 |

| [14] | MASLD: Sprague-Dawley rats fed HFD for 12 weeks, plus HepG2 cells treated with PA | In vivo: 0.05–0.2 mg/kg, twice daily for 4 weeks; In vitro: 1×10−5, 5×10−5, 1×10−4 or 5×10−4 mM for 24h | ↑ LC3-II/I protein expression (WB), ↑ beclin 1 protein expression (WB), ↑ ATG7 protein expression (WB) in the liver | ↑ LC3-II/I protein expression (WB), ↑ beclin 1 protein expression (WB), ↑ ATG7 protein expression (WB), ↑ p-AMPK protein expression (WB), ↑ p-mTOR protein expression (WB) | 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.06.023 |

| [23] | MASLD: C57BL/6 mice fed HFD for 12 weeks, plus L-O2 cells treated with FFA | In vivo: 0.1 mg/kg, once daily for 12 weeks; In vitro: 0.0001 mM for 24h | ↑ LC3-II protein expression (WB), ↓ p62 protein expression (WB) in the liver | ↑ p-AMPK protein expression (WB), ↓ p-mTOR protein expression (WB), ↑ beclin 1 protein expression (WB) | 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.05.086 |

| [24] | MASLD and T2DM: Sprague-Dawley rats fed HFD, plus 1% STZ | 3.6 mg/kg, twice daily for 4 weeks |

↑ LC3-II/I protein expression (WB), ↑ LC3 gene expression (RT-PCR), ↑ beclin 1 gene and protein expression (WB and RT-PCR), ↑ p-AMPK protein expression (WB), ↑ AMPK gene expression (RT-PCR), ↓ p-mTOR protein expression (WB), ↓ mTOR gene expression (RT-PCR) in the liver | - | 10.2147/DMSO.S447182 |

| [25] | MASLD: C57BL/6J mice fed HFD for 16 weeks | 150 mg/kg, once daily for 4 weeks | ↓ p62 gene and protein expression (WB and RT-PCR), ↑ beclin 1 gene and protein expression (WB and RT-PCR), ↑ LC3-II/I protein expression (WB); ↑ LC3 gene expression (RT-PCR) in the liver | - | 10.1111/hepr.12634 |

| Reference | Model | Intervention | Effect on autophagy | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | MASLD: C57BL/6J mice fed HFD for 14 weeks | 300 mg/kg, once daily for 9 weeks | ↑ LC3-II protein expression (WB), ↓ p62 protein expression (WB), ↑ TFEB protein expression in the nuclear fraction (WB) in the liver | 10.3389/fphar.2021.689111 |

| [31] | MHCC97H and HepG2 cells | 10 mM, for 12–72 h | ↑ LC3-II protein expression (WB), ↓ p62 protein expression (WB), ↑ p-AMPK protein expression (WB), and ↓ p-mTOR protein expression (WB) in both cell lines | 10.2147/CMAR.S257966 |

| Reference | Model | Intervention | Effect on autophagy | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | Fisher-344 rats aged 4, 12, and 22 months | 40% calorie restriction of energy intake | Robust CMA activation in tissues of aged rodents via LAMP2A stabilization | 10.1073/pnas.2317945121 |

| [38] | Wistar rats fed HFD for 18 weeks | 70% calorie restriction of energy intake | ↑ LC3-II gene and protein expression (RT-PCR and WB), ↑ beclin 1 gene expression (RT-PCR), ↑ SIRT1 gene and protein expression (RT-PCR and WB), ↓ p62 gene and protein expression (RT-PCR and WB) in the liver | 10.1371/journal.pone.0183541 |

| Reference | Model | Intervention | Effect on autophagy | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44] | Obese humans with MASLD | Diet with 22–25 kcal/kg/day, plus IF 16:8 (16 h fasting and 8 h feeding) for 8 weeks | ↑ Serum ATG5 in the IF group (ELISA) | 10.3390/life15050696 |

| [45] | C57BL/6 mice fed HFD for 8 weeks | IF 24 h, on 3 non-consecutive days/week for 8 weeks | ↑ LC3 protein and gene expression (WB and qRT-PCR) in the liver of control and HFD-fed animals, ↑ LAMP1 protein expression in the liver of control animals (WB), and ↑ beclin 1 gene expression (qRT-PCR) in the liver of control animals. | 10.1016/j.nut.2022.111662 |

| Reference | Model | Intervention | Effect on autophagy | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | C57BL/6 mice fed HFD for 8 weeks | 20 mg/kg, once daily for 2 weeks | ↑ LC3-II/I protein expression (WB), ↑ beclin 1 protein expression (WB), ↑ ATG7 and ATG12 protein expression (WB) in gonadal white adipose tissue | 10.3390/nu12103072 |

| [52] | Primary mouse hepatocytes | 0.04 mM, for 24 h | ↑ LC3-II protein expression (WB), ↓ p62 protein expression (WB), ↑ AMPK protein expression (WB) | 10.1371/journal.pone.0087161 |

| [53] | Differentiated adipocytes (C3H10T1/2) | 0.01 mM, for 24 h | ↑ LC3 protein expression (WB) and ↑ AMPK protein expression (WB) | 10.3390/nu9070680 |

| [54] | Swiss rats fed HFD for 16 weeks | 50 mg/kg, once daily for 16 weeks | ↑ SIRT1 and p-AMPK protein expression (WB) in the liver | 10.1371/journal.pone.0141227 |

| Reference | Model | Intervention | Effect on autophagy | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [63] | Goto-Kakizaki rats fed HFD for 10 weeks | 50 or 75 mg/kg, once daily for 8 weeks | ↑ LC3 protein expression (WB), ↑ beclin 1 protein expression (WB), and ↑ Pink1/Parkin protein expression (WB), ↓ p62 protein expression (WB), ↓ mTOR protein expression (WB), ↓ p-mTOR protein expression (WB), ↓ PI3K protein expression (WB), ↓ p-PI3K protein expression (WB), ↓ AKT protein expression (WB), and ↓ p-AKT protein expression (WB), in the liver | 10.3389/fmed.2024.1442071 |

| [64] | ApoE mice (C57BL/6J background) fed HFD for 24 weeks | 100 mg/kg, once daily for 24 weeks | ↑ Protein expression of LC3-II (WB), ↓ Protein expression of p62 (WB), ↓ Protein expression of mTOR (WB) in the liver | 10.1155/2015/607531 |

| [65] | C57BL/6J mice fed HFD for 12 weeks | 10 and 50 mg/kg, once daily for 4 weeks | ↑ Expression of LC3 and p62 in the liver (IHC), ↑ Protein expression of LC3 in the liver (WB) | 10.3390/nu16244282 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).