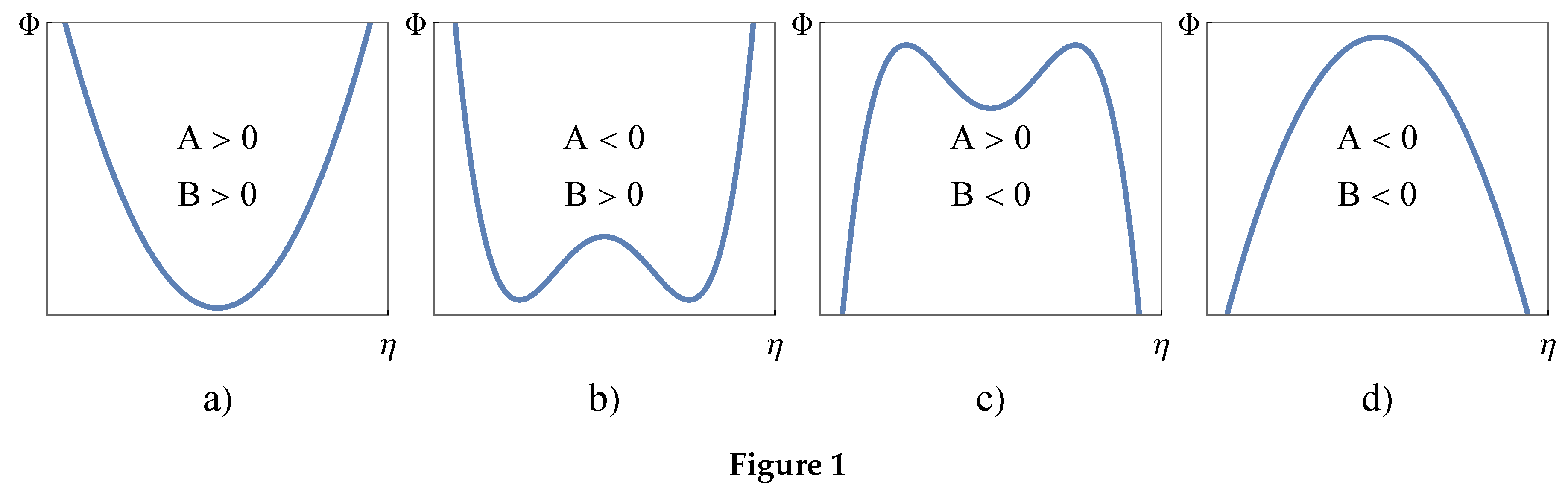

3.1. Uniaxial Ferromagnets

Consider an uniaxial ferromagnet with an easy-axis in parallel to the

z-axis in an external magnetic field in a basal plane. A thermodynamic potential in this case has the following form

where

is the saturation magnetic moment. Equilibrium directions

can be determined from the condition

which gives us two phases:

- a)

the “high-field” phase: , ;

- b)

the angular phase: , .

The last equation determine the magnetization curve in the angular phase if we consider

:

From the condition

at

we can find the high-field phase stability region:

(the equality corresponds to the magnetic field at which the phase loses its stability). The stability region of the angular phase can be easily determined if we consider

in the form

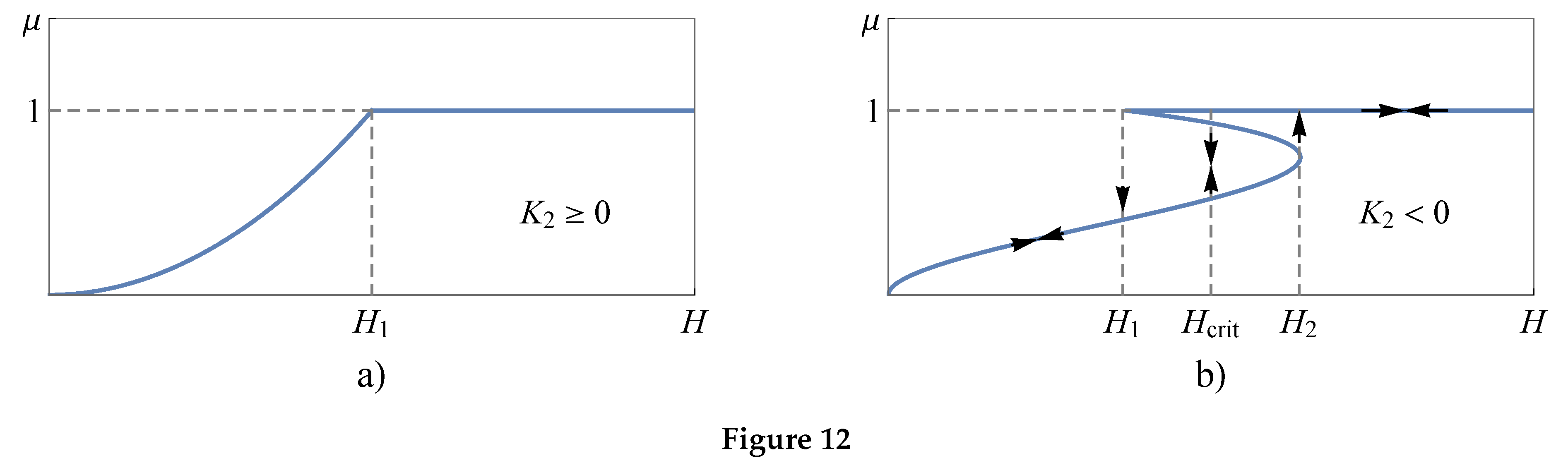

At

the angular phase stable for any

:

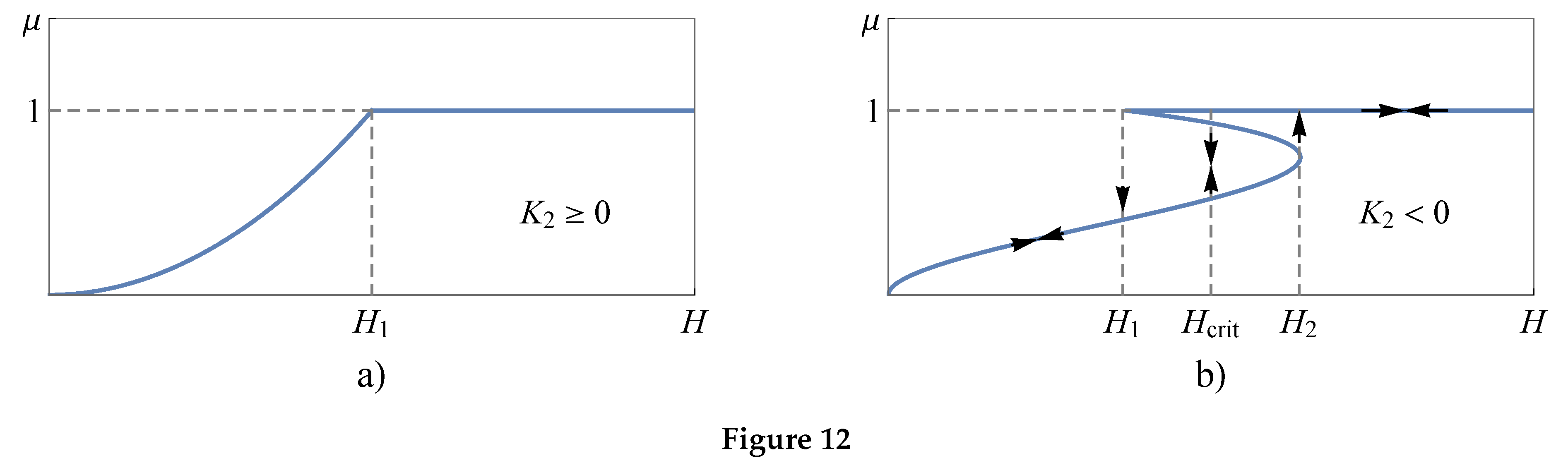

, so the orientational phase transition from the angular phase into the high-field phase will always be a second-order phase transition with the critical field

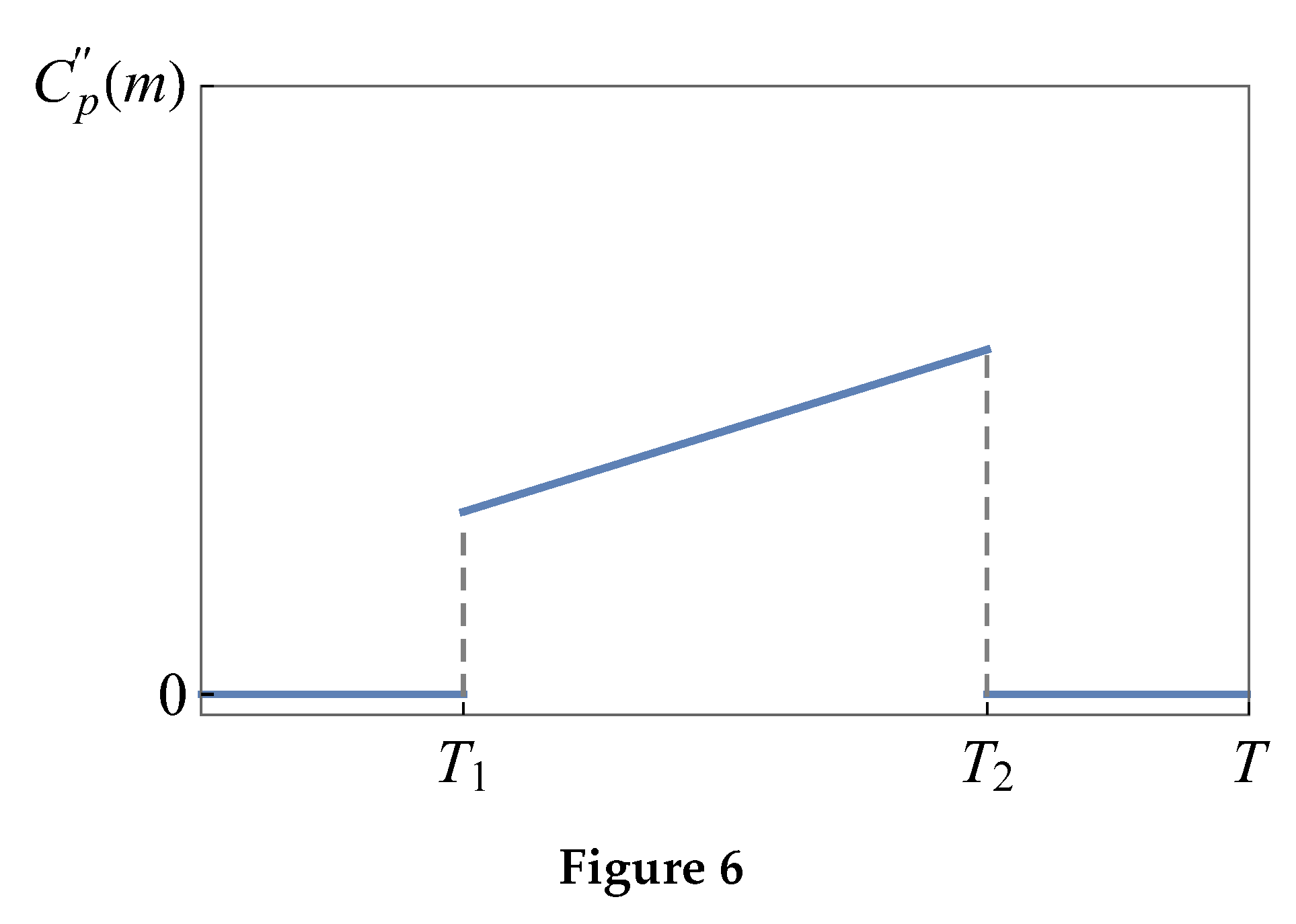

(Figure 6), at which the phase stability loss occurs and the values of the thermodynamic potentials equalize. At

the angular phase loses stability at

which corresponds to the value of the magnetic field

The field

of the stability loss of the angular phase corresponds to a point on the magnetization curve, in which

The TDP of the angular and high-field phases match up at

, which can be determined by the equation

at

The solution of these equations gives us

Thus, at the transition from the angular phase into the high-field phase is a first-order phase transition.

Two different options of magnetization curves in a hard direction of the uniaxial ferromagnet shown in the Figure 6.

There is regions at in the magnetization curve corresponding to metastable states, which leads to hysteresis in single-domain samples. In multi-domain samples a hysteresis-free option of the first-order transition is possible.

All of the results above can be used for the analysis of a transition from the easy-plane phase into the easy-axis phase at . For this analysis the replacement is needed in all of the expressions for the critical fields.

3.2. Anisotropic Antiferromagnets. “Spin-Flop” Transitions

An interaction energy of an antiferromagnet with an external magnetic field can be determined in the following form:

where

is the normalized antiferromagnetism vector (

where

are the magnetization of the sublattices,

);

is the perpendicular susceptibility (susceptibility at

),

is the parallel susceptibility (susceptibility at

).

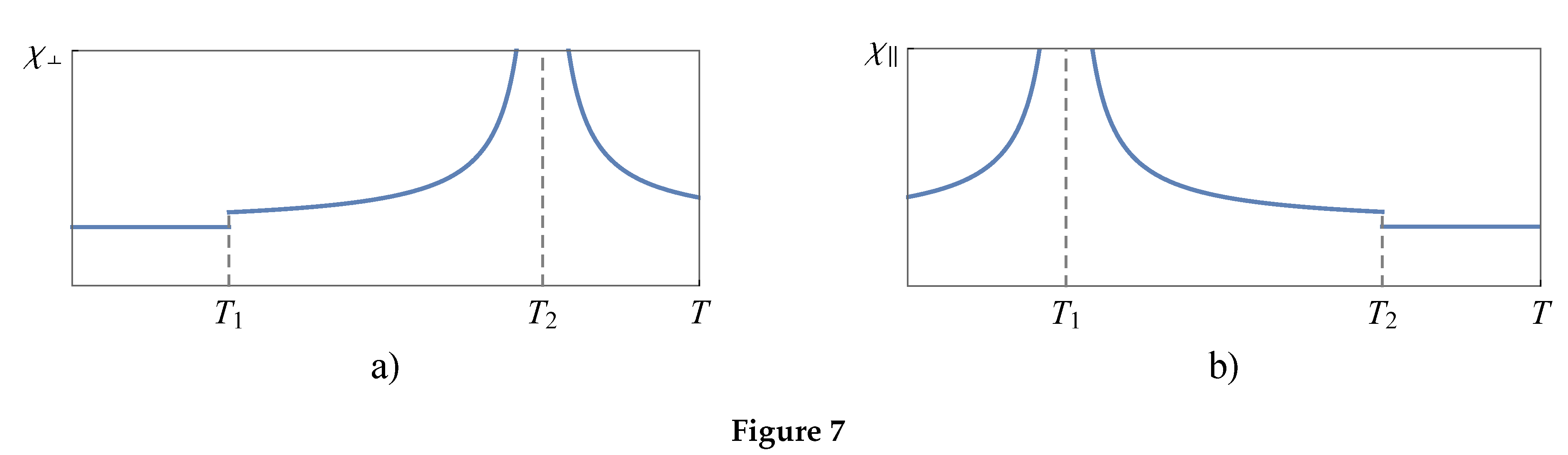

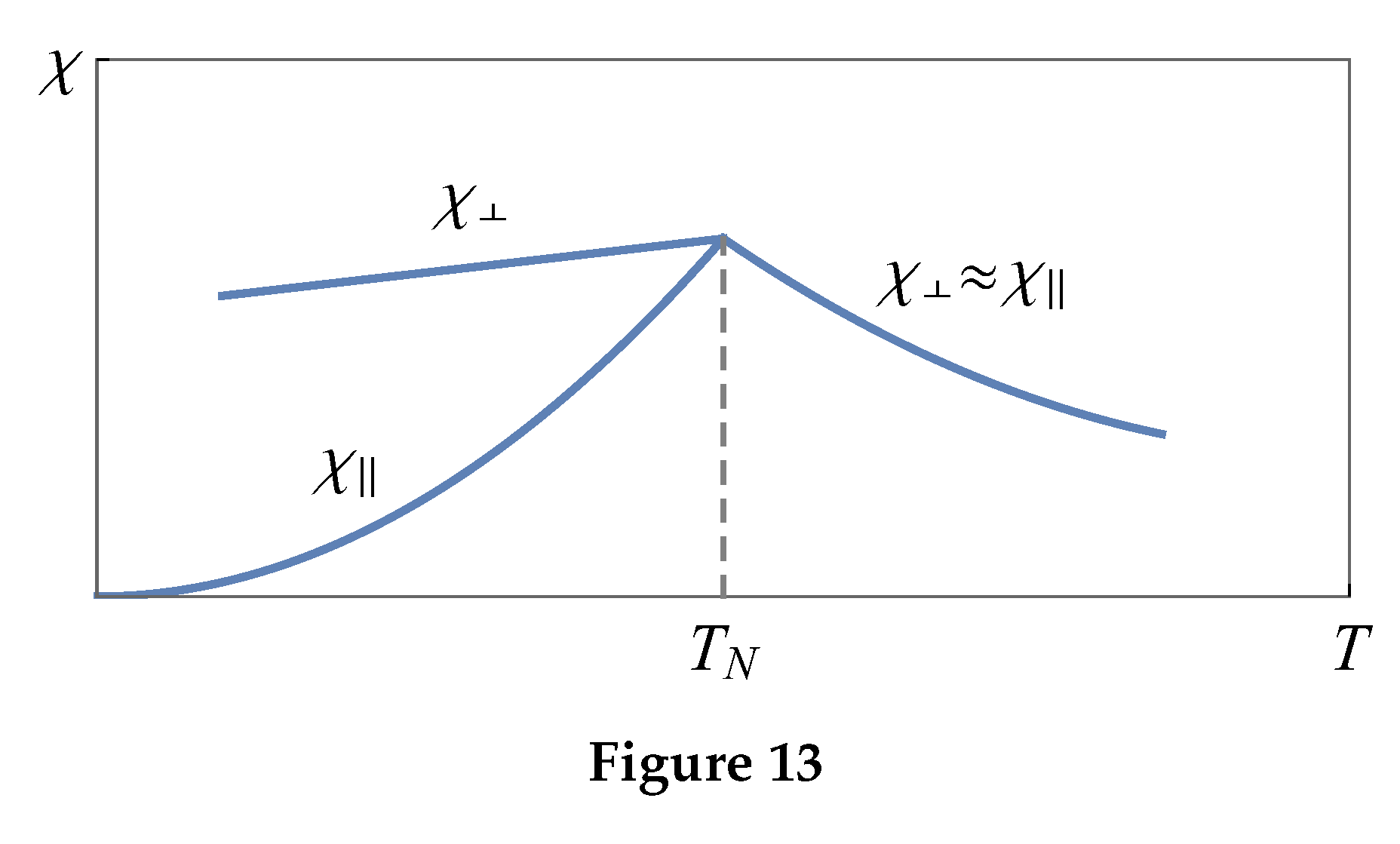

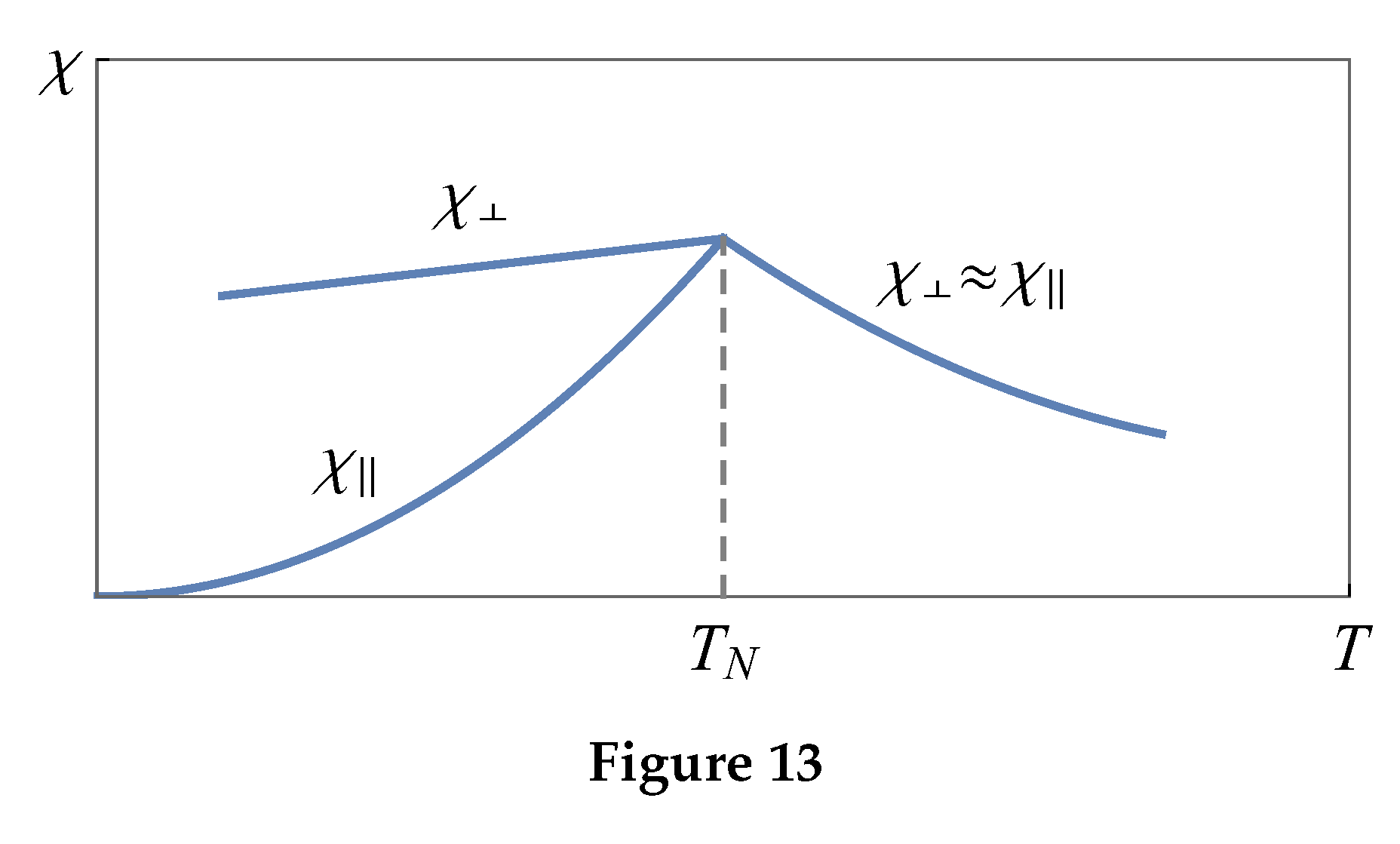

A characteristic temperature dependence of and for weakly anisotropic antiferromagnets like MnF shown in the Figure .

In the transverse phase () of the antiferromagnet the Zeeman energy is less by than in the longitudinal phase ().

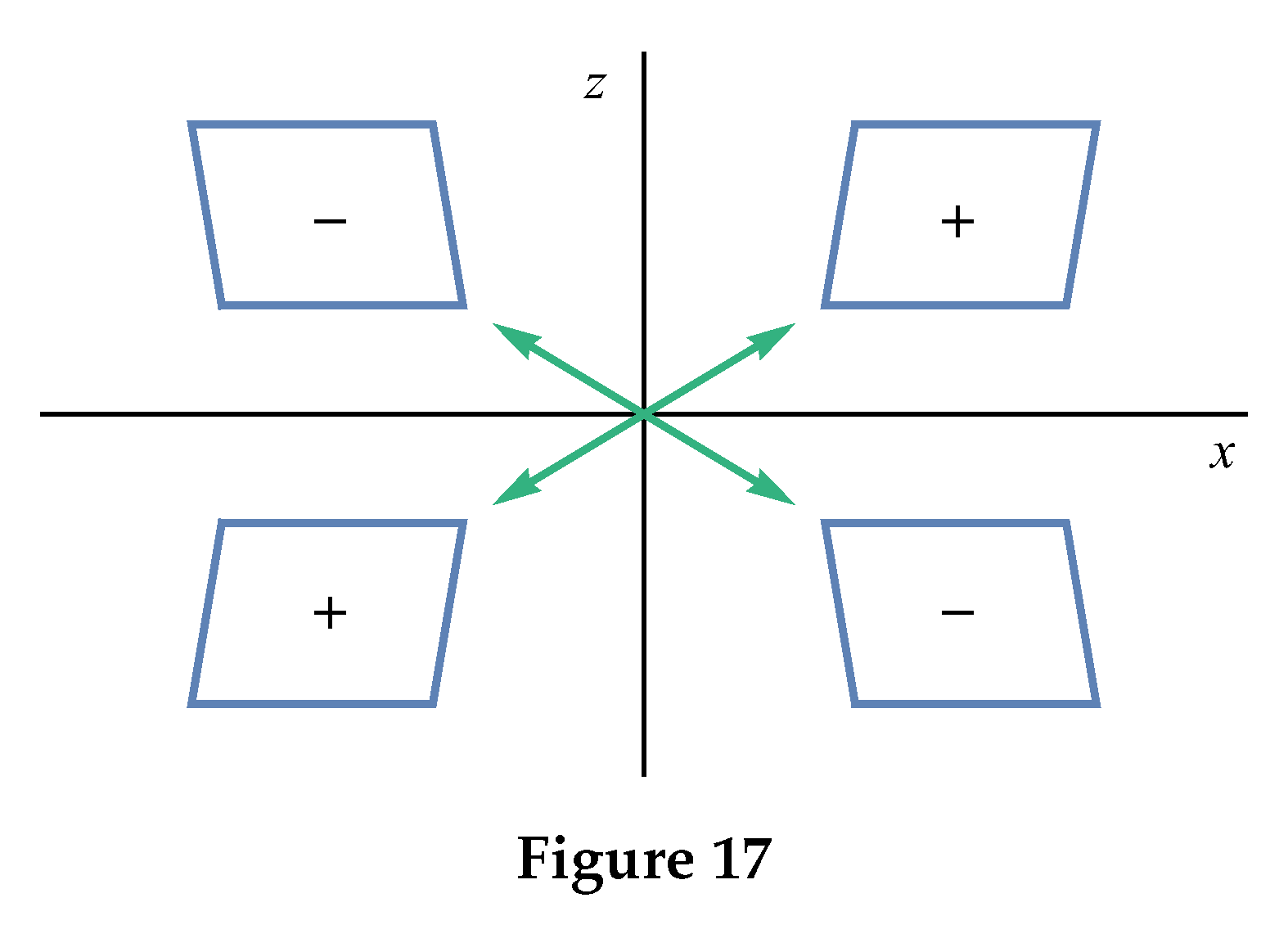

Let us consider a rhombic anisotropic antiferromagnet in external magnetic fields oriented along one of the crystallographic axes, e.g.

z-axis. A TDP, which is describing rotation processes of

in one of the planes, will has the following form:

where

is the angle between the

z-axis and the vector

.

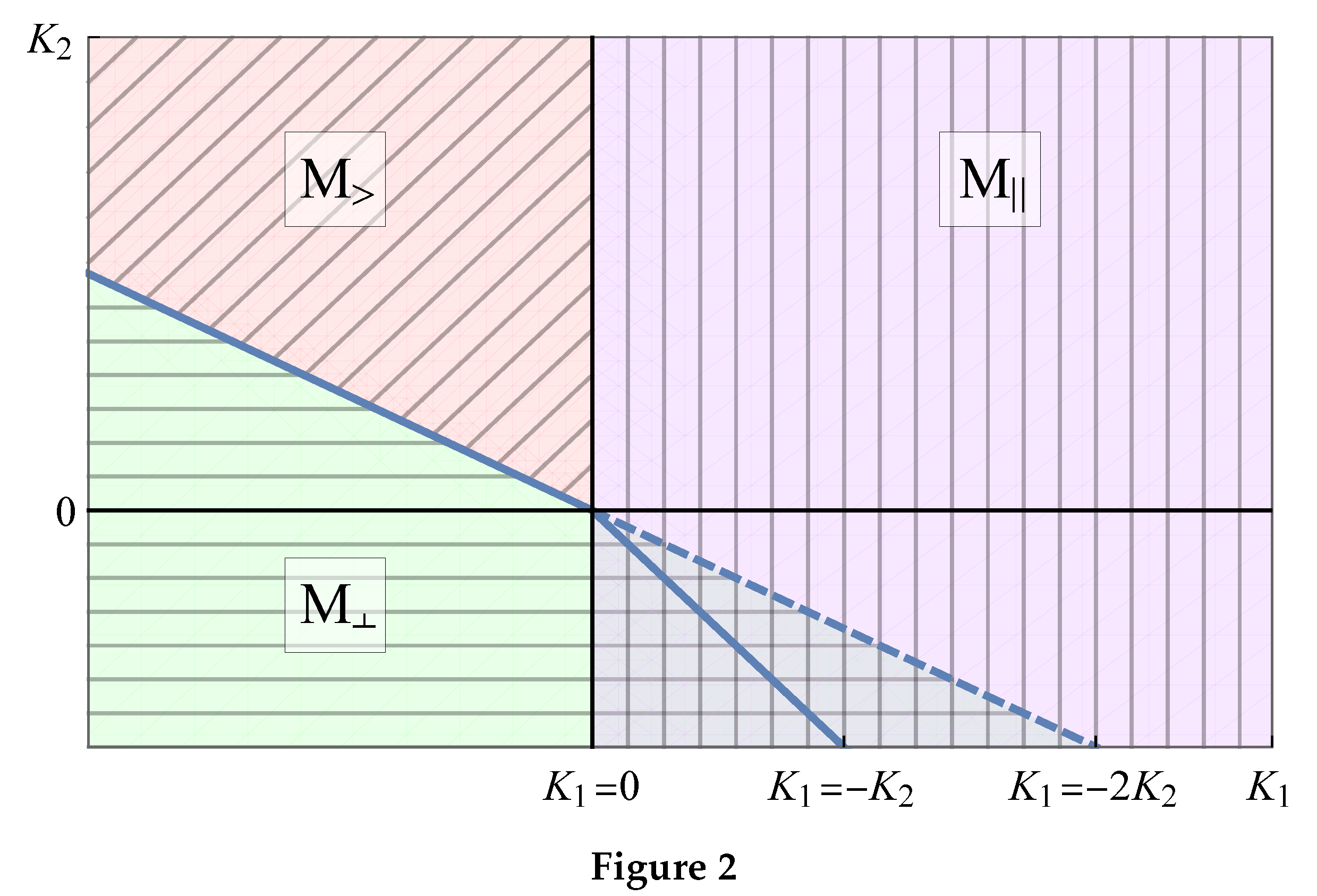

Obviously, that taking into account the external magnetic field in this case leads to a renormalization of the first anisotropy constant. Thus, the analysis of the antiferromagnet behavior in the field can be based on the

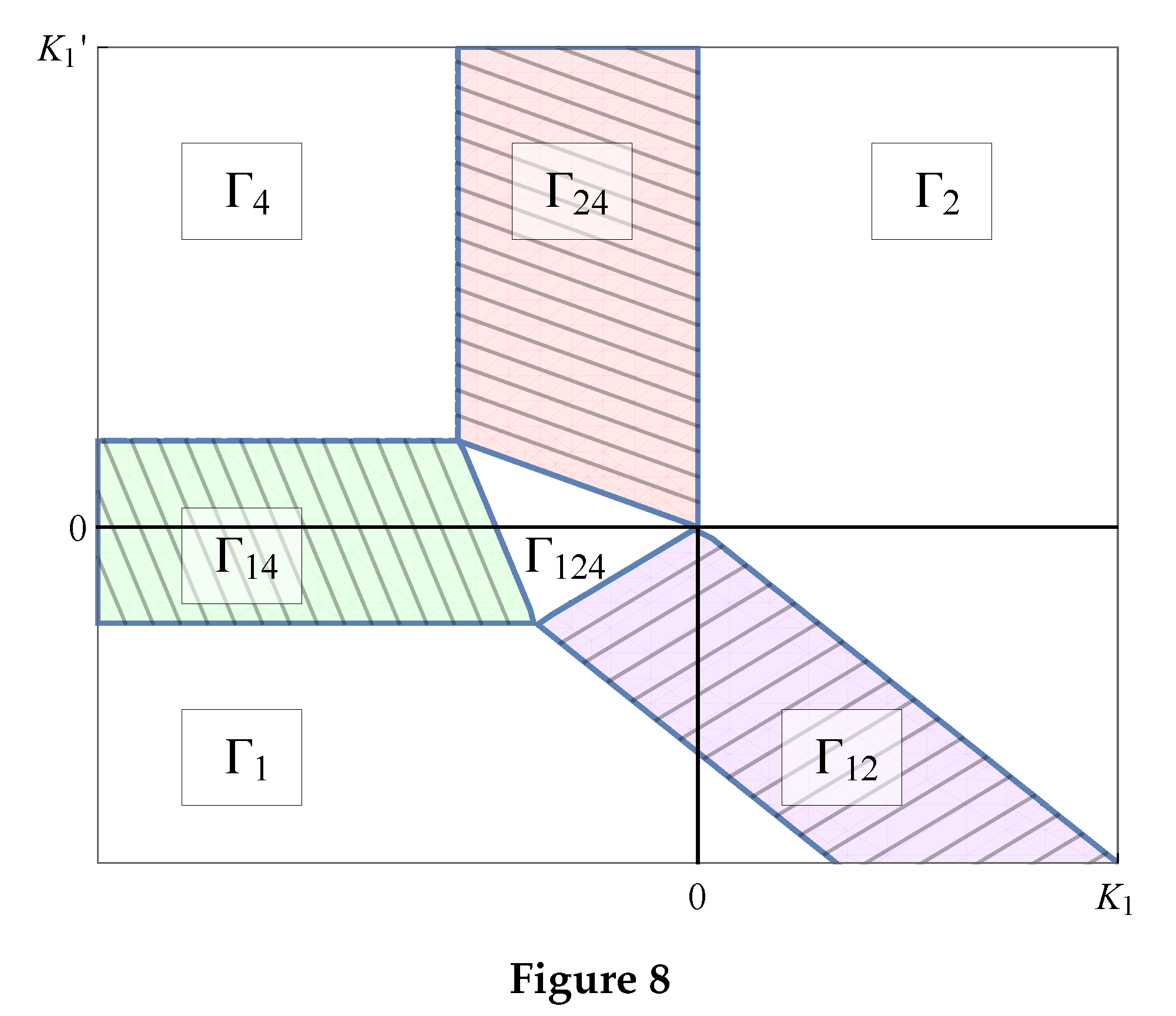

Section 2.1, in particular the phase diagram on the Figure .

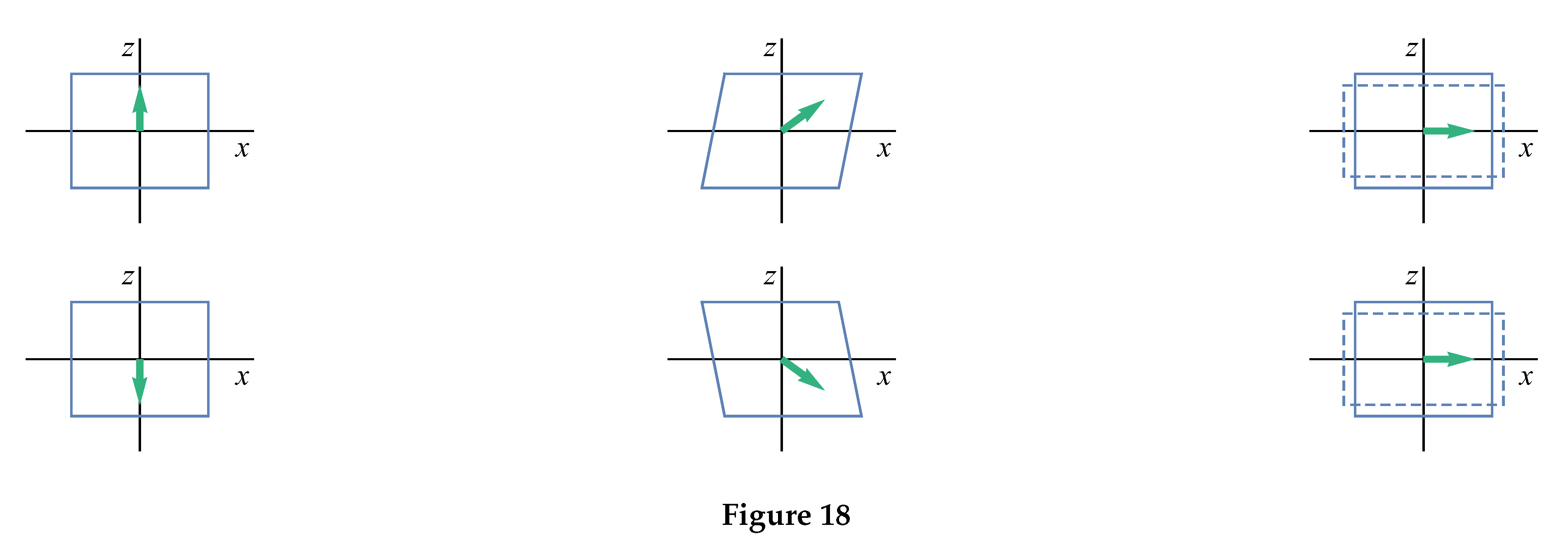

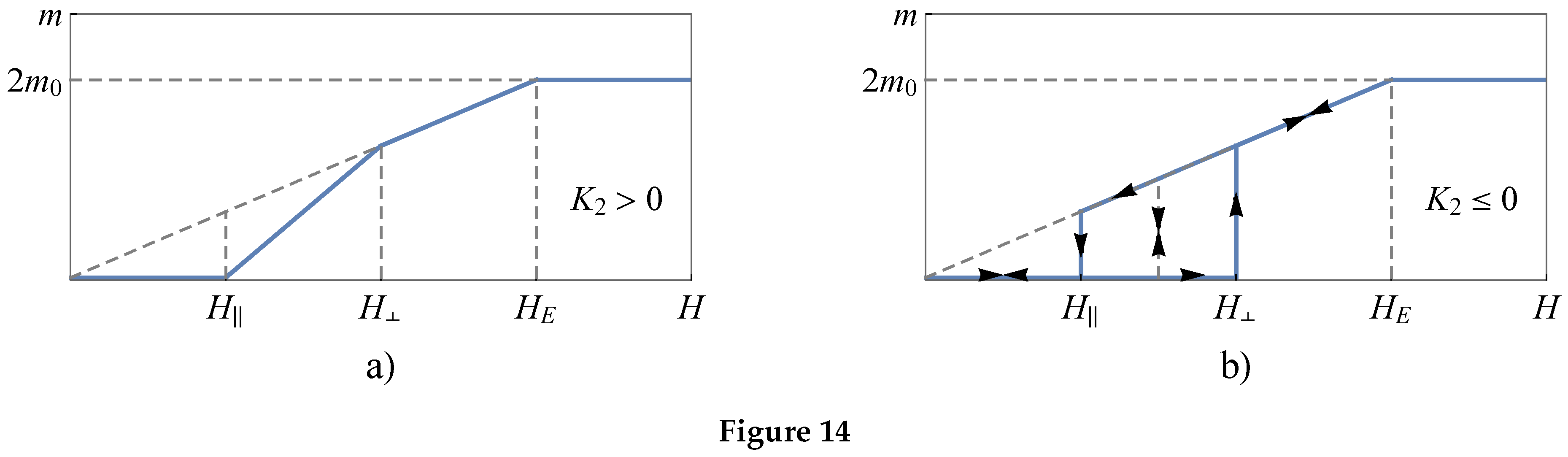

At

and the initial phase

the inclusion of the external magnetic field

leads to a “spin-flop” transition from the longitudinal phase

into the transverse phase

, which is starting at

as a second order phase transition (the transition into the angular phase), and ending at

also, as a second order phase transition (the transition from the angular phase into transverse phase).

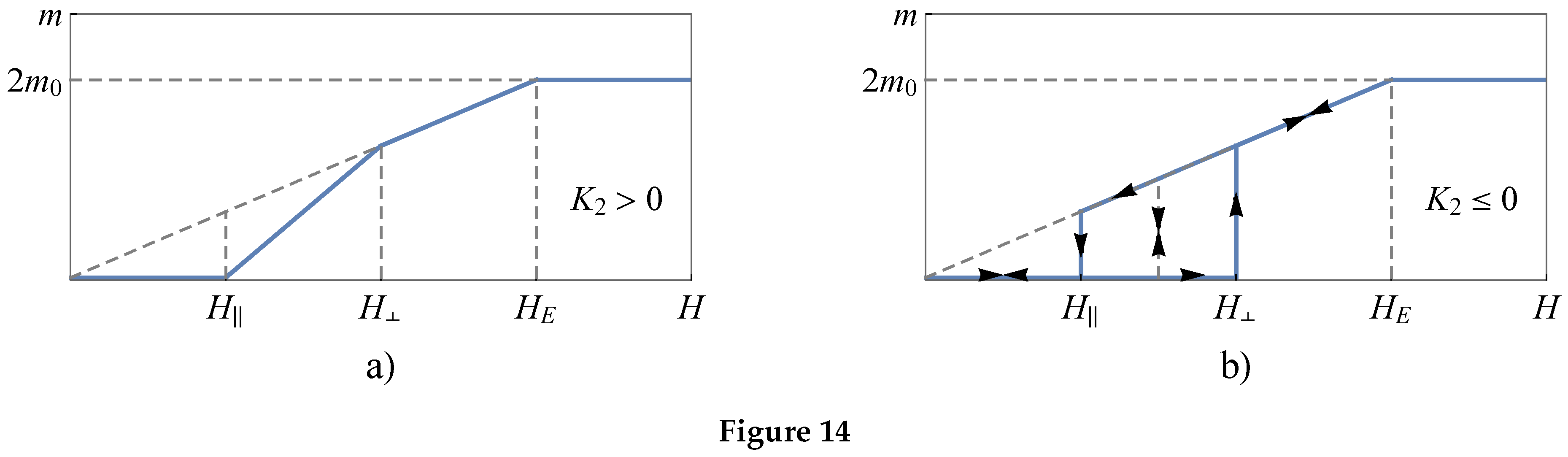

At and the initial longitudinal phase loses the stability at , and the transverse phase became stable at (). Thus, in the region of fields the longitudinal and transverse phases can coexist. Equality of the thermodynamic potentials of both phases takes place at , and .

In an external magnetic field, which is exceeded the maximum of the critical fields , , , gradual “contraction” of the magnetic moments of the sublattices 1 and 2 to the direction of the magnetic field H occurs. So, in the sufficiently large magnetic field ( for the weakly anisotropic antiferromagnets, is the exchange field) a ferromagnetic structure is realized.

Schematically a magnetization curve of the antiferromagnet in our case shown in the Figure 7. The magnetic susceptibility on the region

(Figure 7a) or

(Figure 7b) matches with

, and on the region

it matches with

. On the region

(Figure 7a) the susceptibility has a “rotational” character:

where we used the following relations:

Let us pay attention to that

at

from the right and at

from the left. At

(low temperature) and

(

) the rotational susceptibility

can significantly exceed

.

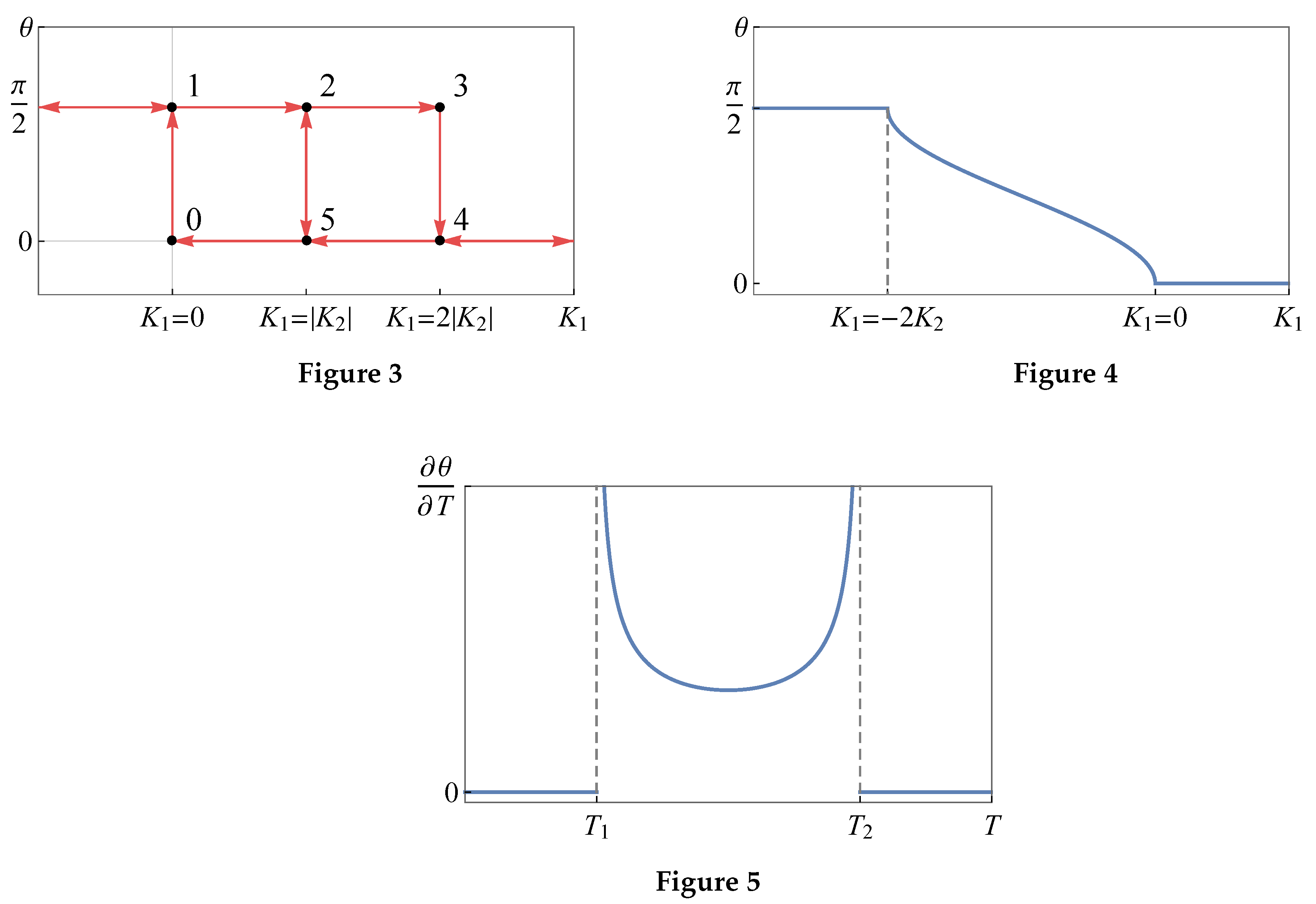

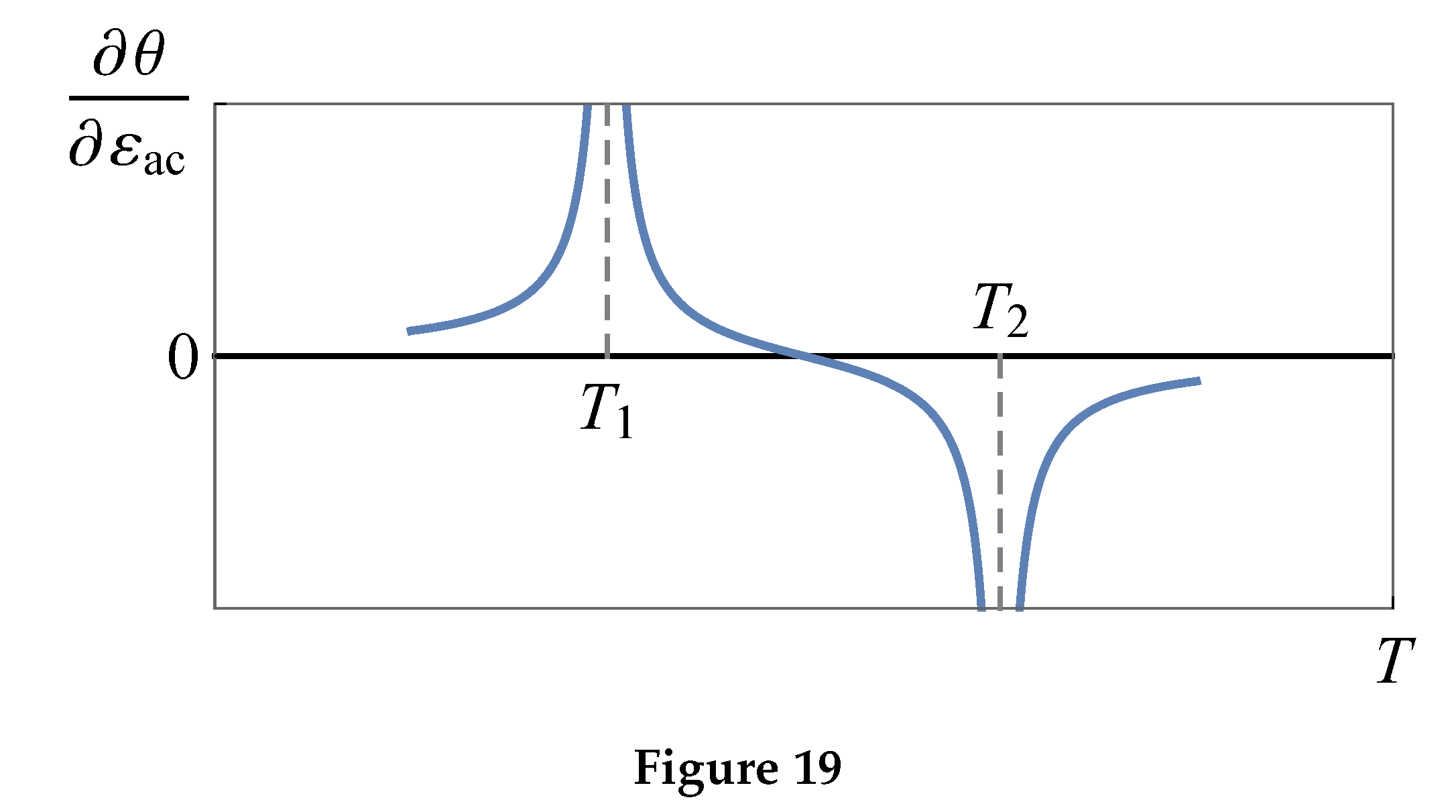

3.3. Metamagnetic Transitions in High-Anisotropy Magnets

Considering the “spin-flop” transitions we implicitly assumed that a magnetic anisotropy energy is small in comparison with an exchange energy. There is, actually, a wide enough class of high-anisotropy magnets, which has the anisotropy energy comparable with the exchange energy, or even exceeds it. For a research of the peculiarities of orientational transitions induced by a magnetic field in such systems we restrict ourselves with case, and also with the region of sufficiently low temperatures, at which in antiferromagnets.

A model thermodynamic potential for the analysis of the orientational phase transition in the certain plane can be determined in the following form:

where

I is the exchange constant,

are the orientation angle of sublattices magnetic moments,

is the orientation angle of the external magnetic field

.

A minimization of the TDP in the magnetic field

H, which is directed along the anisotropy axis (

), gives us three equilibrium phases:

A research of the stability of this structures shows that the antiparallel ordering of the magnetic moments

,

exist in the region

where

,

are the anisotropy and the exchange field respectively. The second state

with the flipped lattices is stable in the region

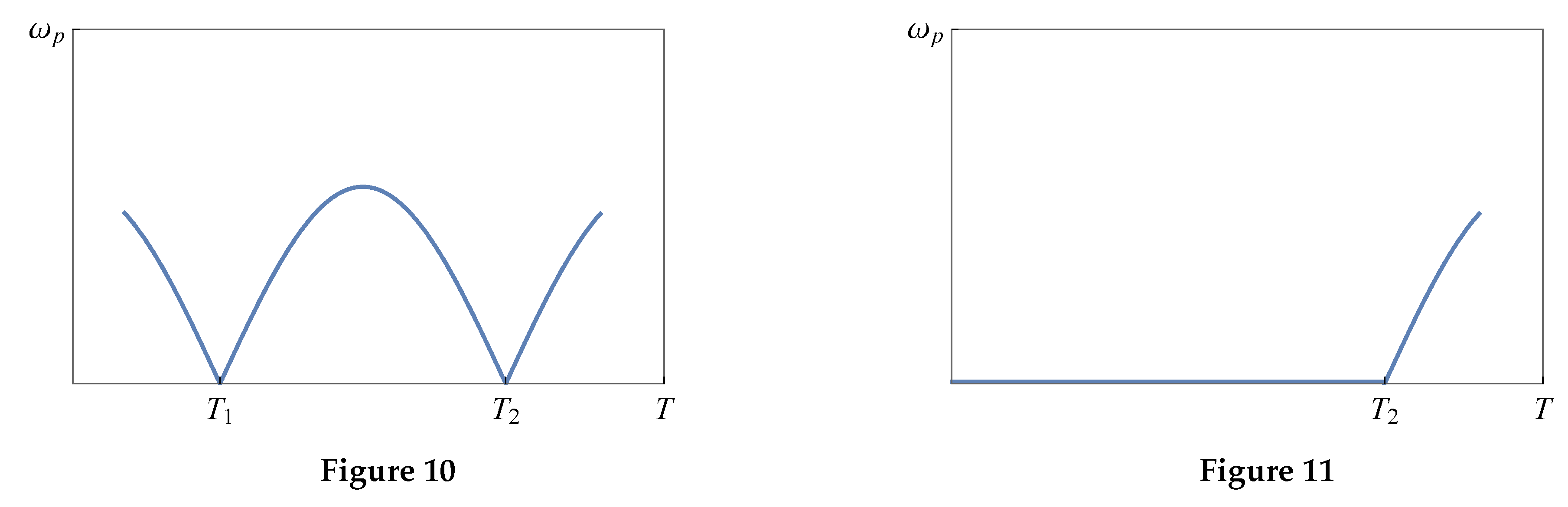

The magnetic fields and are the analogues of and for the weakly anisotropic antiferromagnet (Figure 7b). The existing of overlapping phases witness about a possibility of hysteresis.

The state with the flipped sublattices at the increasing of the magnetic field smoothly transit into a “ferromagnet” state in the magnetic field .

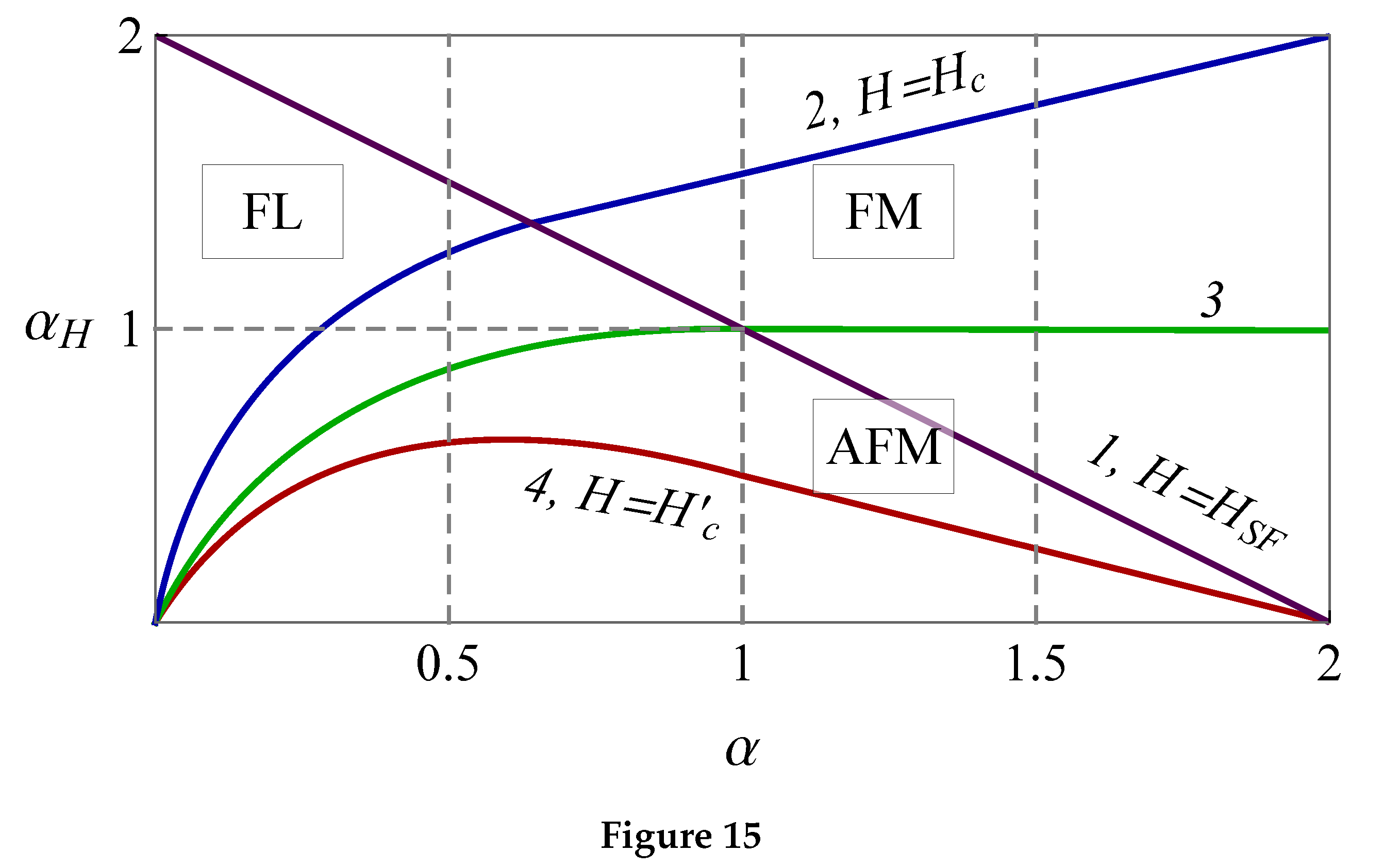

With the increasing of the anisotropy constant, or the anisotropy field , the magnitude of the magnetic field decreases, but the magnitude of the magnetic field increases. With this the stability regions of the antiferromagnet phase (, ) and ferromagnet phase () expand, and simultaneously the stability region of the angular phase () narrows. Physically this fact corresponds to the minimum of the anisotropy energy in the ferro- and antiferromagnet phases, unlike the angular phase.

At

the upper border of the antiferromagnetic phase stability is compared with the lower border of the ferromagnetic phase stability

. At

energies of the three phases

become equal and, with a further increase in

, the phase with flipped sublattices becomes energetically unfavorable for any

H. Magnets for which the condition

is valid are called metamagnets. Because of this condition, in metamagnets there is no phenomenon of flipping magnetic sublattices.

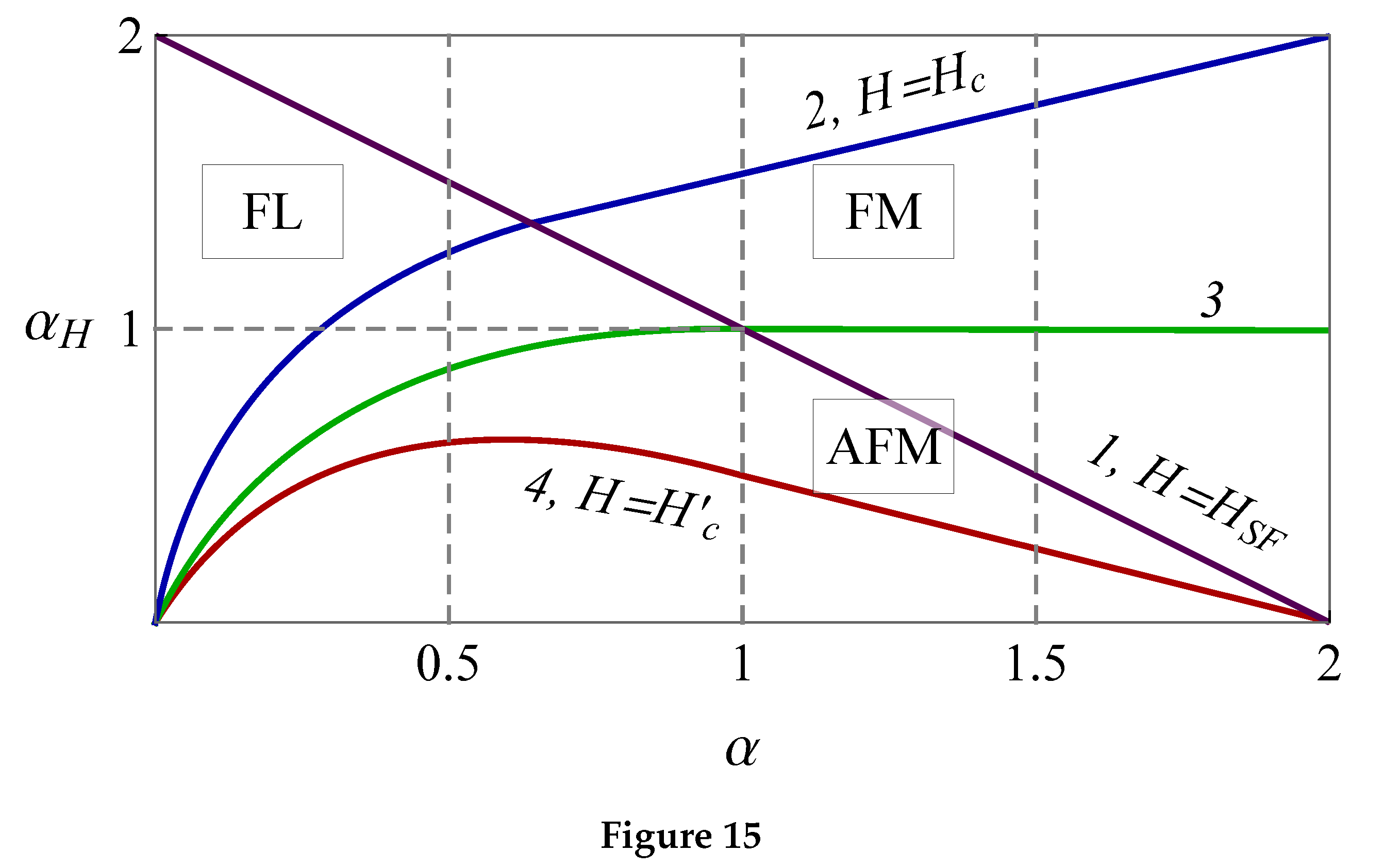

Figure shows the phase diagram of the system described by the TDP (

88) in coordinates

,

. It can be seen from the figure that at

, i.e. at

, there is always the phase with flipped sublattices FL (between the phase lines 1 and 3). The transition from the antiferromagnetic phases (AFM) to the FL-phase can be delayed, this phenomenon analogous to overheating during a first-order phase transition such as melting. The reverse transition FL–AFM can also be delayed (this is shown in Figure by the lines 2 and 4). At

, the FL-phase is absent. With an increase in the external field at

, the AFM-phase transforms into the FM-phase, i.e. into a ferromagnet induced by the field. The region

of the phase diagram is the region of the metamagnetic state existence.

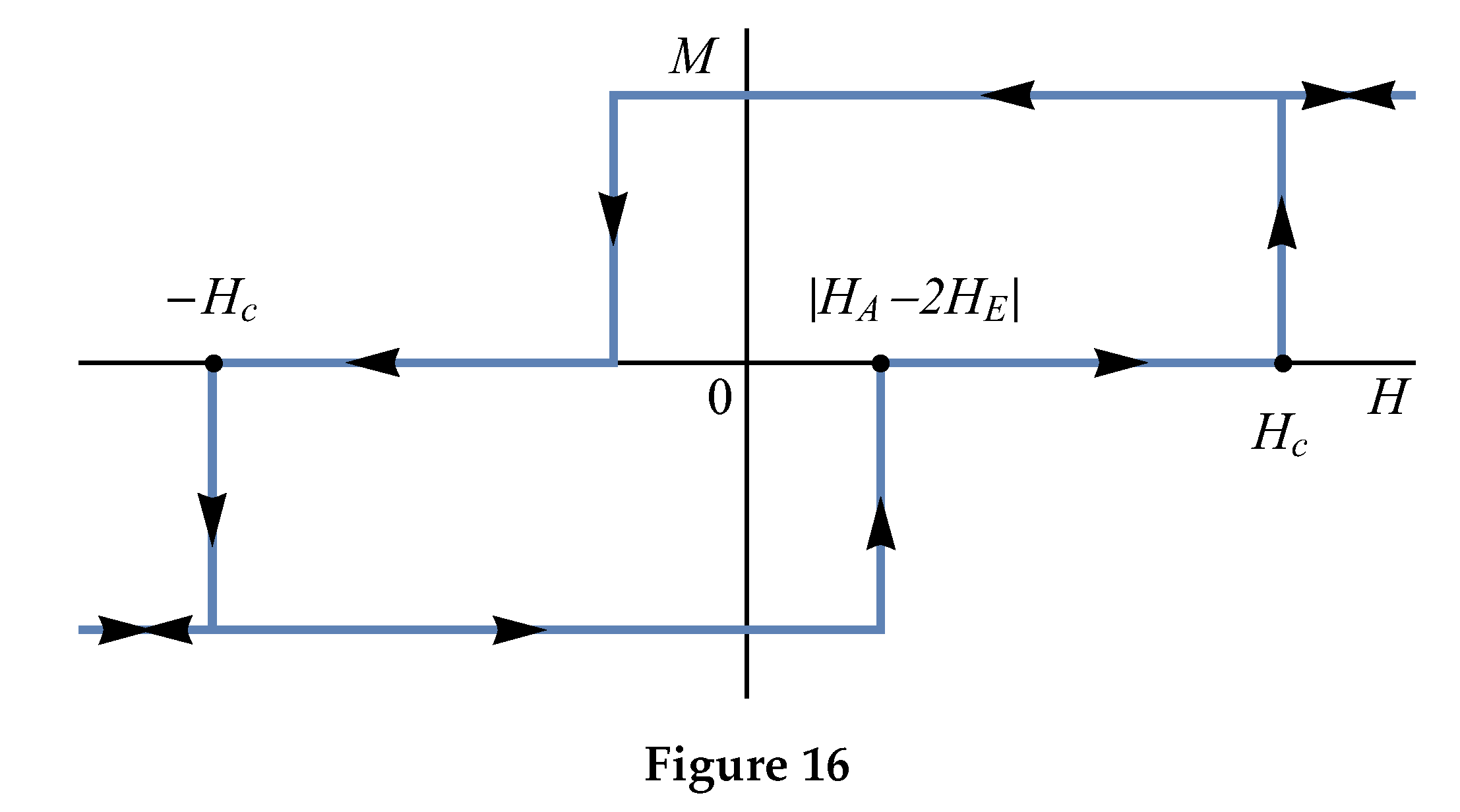

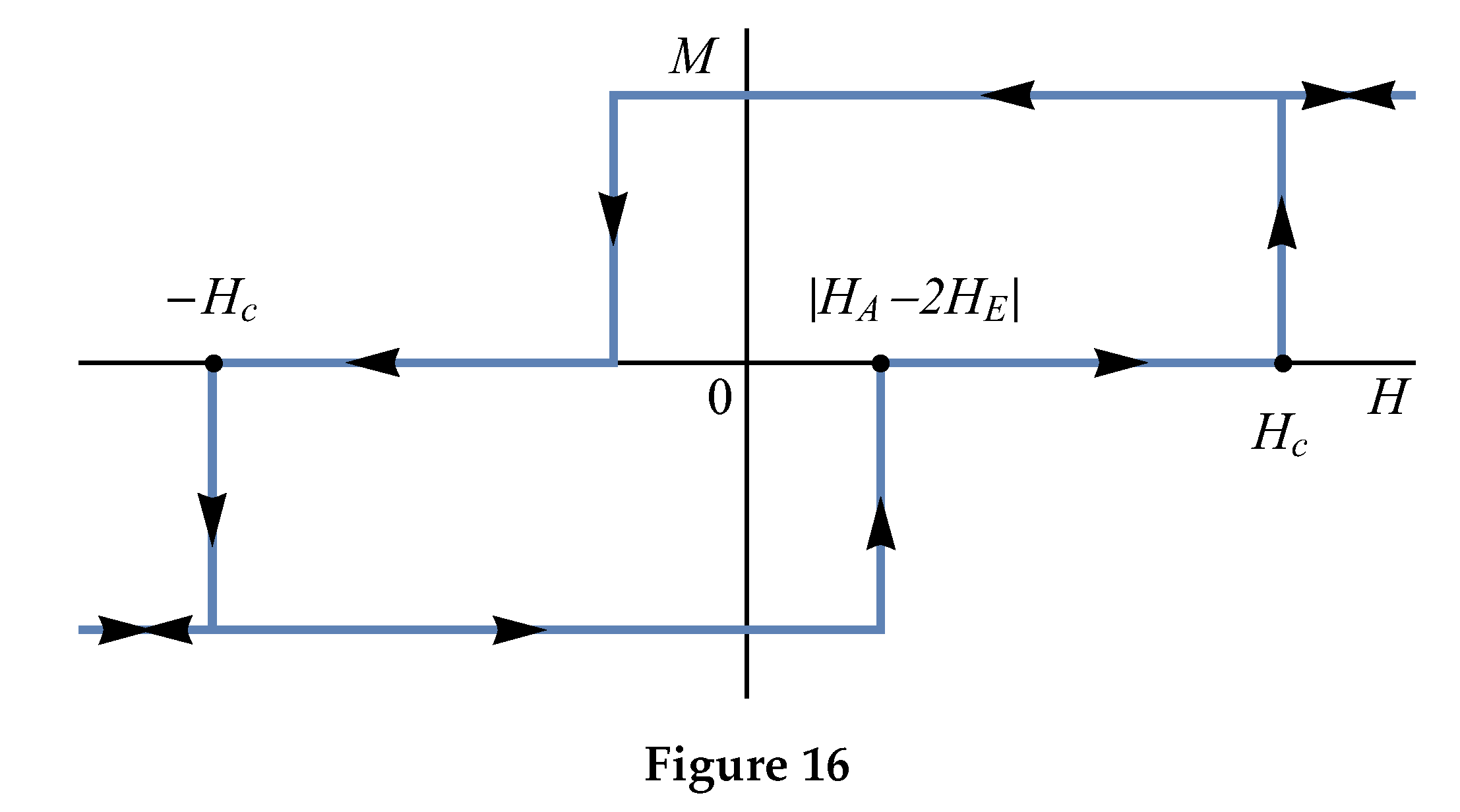

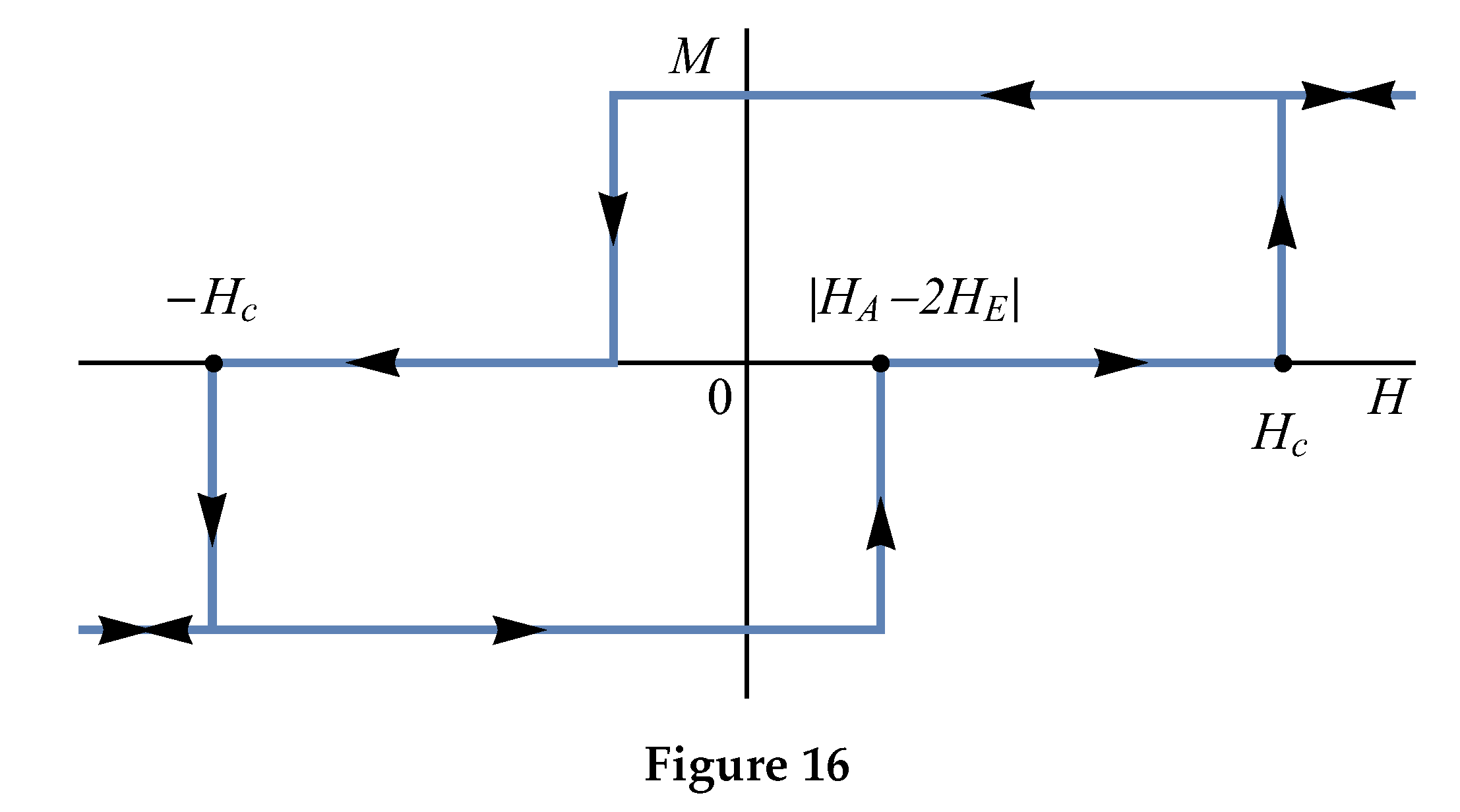

The transition AFM–FM in an external field is called the “spin-flip” transition. A typical magnetization curve for metamagnets is shown in Figure . We note that a decrease in the field to zero after the spin-flip transition can not be accompanied by a return of the system to the AFM state (this requires ). Thus, after turning off the field, the metamagnet can remain in the FM state, it will have remanent magnetization. If the value of , which plays the role of the coercive force in this case, is sufficiently large, then such a metamagnet can be used as the material for permanent magnets.