Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

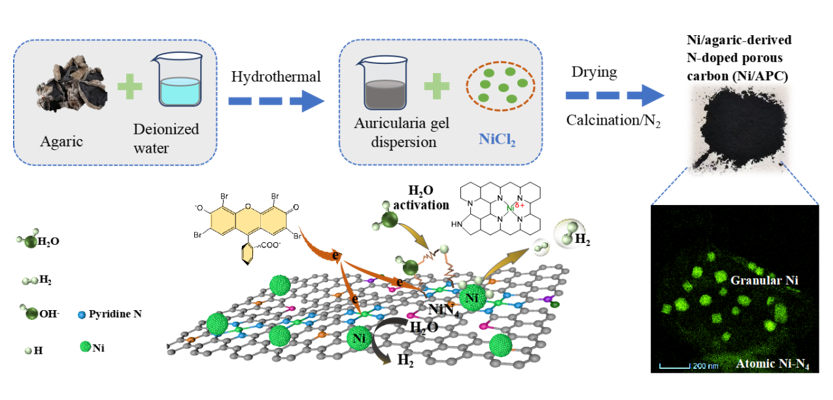

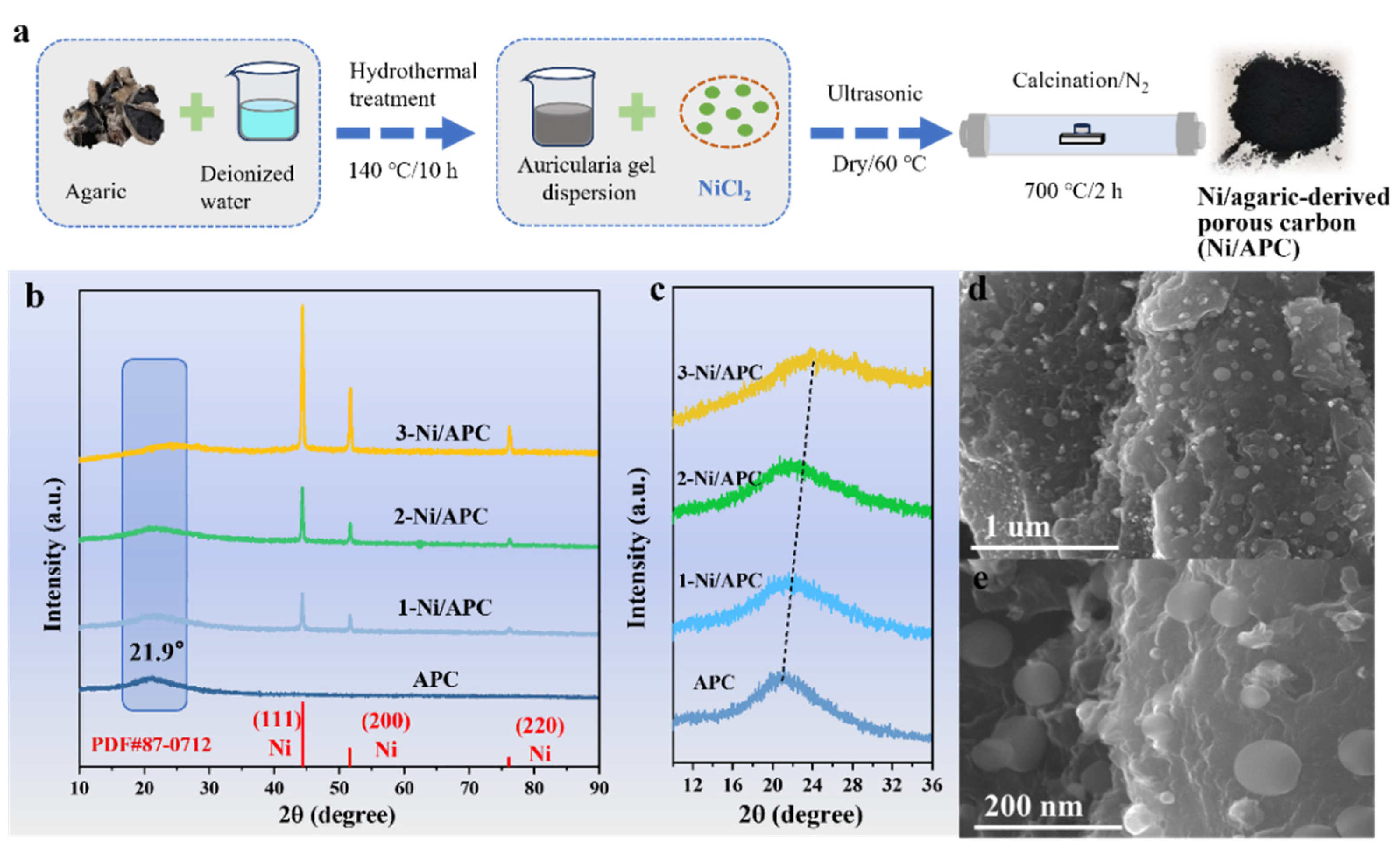

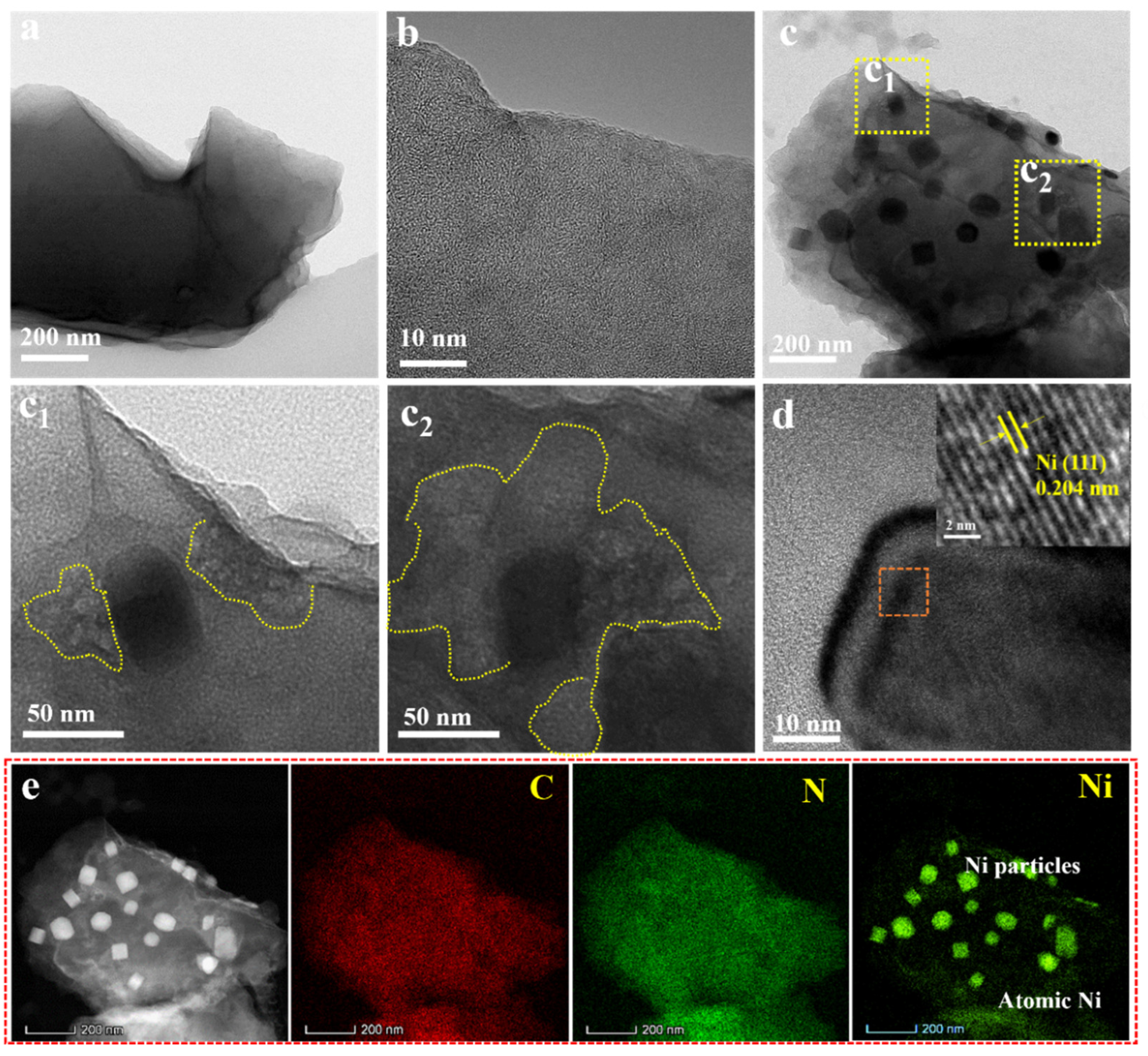

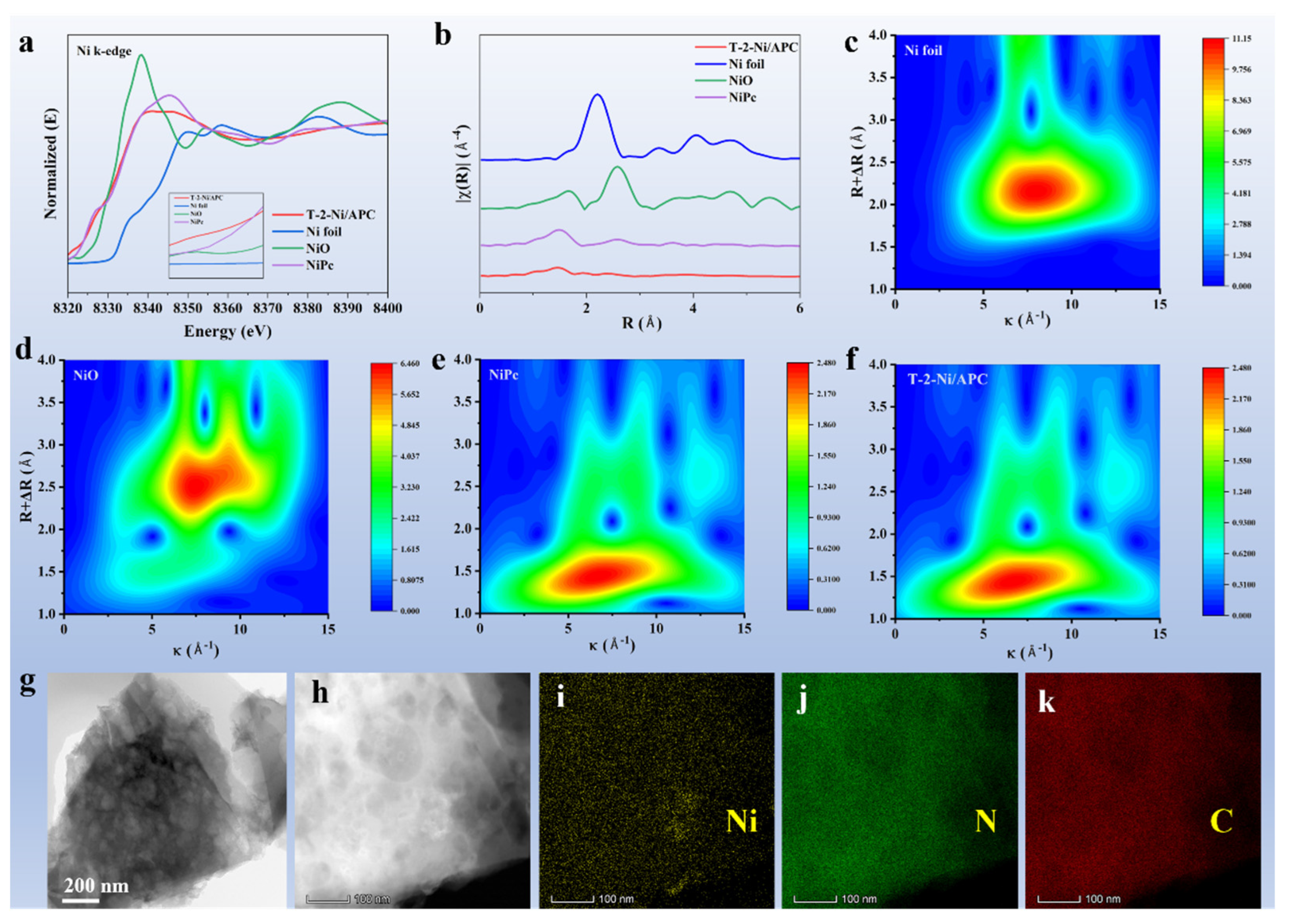

2.2. Preparation of Ni/Agaric-Derived N-Doped Porous Carbon (APC) Composites

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Photocatalytic Performance

2.5. Electrochemical Test

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, W.Y.; Ai, P.; Yuan, L.W.; Peng, S.Q.; Li, Y.X. In-situ converting CoO@Co/RGO into Co/Co(OH)2/RGO for improved dye-sensitized photocatalytic H2 evolution. Fuel 2024, 369, 31785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.D.; Li, Y.X. Precisely loading Pt on Tb4O7/CN heterojunction for efficient photocatalytic overall water splitting: design and mechanism. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2024, 342, 123393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Q.; Peng, S.Q.; Li, Y.X. Constructing an open-structured J-type ZnIn2S4/In(OH)3 heterojunction for photocatalytical hydrogen generation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 5215–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Peng, S.Q.; Li, Y.X. Template-free synthesis of hollow Ni/reduced graphene oxide composite for efficient H2 evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 13072–13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.Z.; Lu, G.X. 750 nm visible light-driven overall water splitting to H2 and O2 over boron-doped Zn3As2 photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2023, 338, 123045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaar, N.; Wu, S.M.; Qin, S.S.; Hamrouni, A.; Sarma, B.B.; Doronkin, D.E.; Denisov, N.; Lachheb, H.; Schmuki, P. Single-atom catalysts on C3N4: minimizing single atom Pt loading for maximized photocatalytic hydrogen production efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202416453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.X.; Wang, X.C. Peroxide production by porphyrins. Nat. Energy 2023, 8, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.R.; Yan, B.; Xu, H.K.; Li, H.; He, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, G. NiCS3: a cocatalyst surpassing Pt for photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2024, 659, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Mei, X.; Yuan, L.W.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.X.; Peng, S.Q. Tuning metal-support interaction of NiCu/graphene cocatalysts for enhanced dye-sensitized photocatalytic H2 evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 593, 153459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.B.; Fu, X.B.; You, X.M.; Zhao, E.; Li, F.F.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.X.; Wang, X.L.; Yao, Y.F. Synergistic promotion of single-atom Co surrounding a PtCo alloy based on a g-C3N4 nanosheet for overall water splitting. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 6958–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Yang, T.Y.; Li, H.; Tong, R.; Peng, S.Q.; Han, X. Transformation of Fe-B@Fe into Fe-B@Ni for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2020, 578, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.J.; Liu, X.T.; Zhao, X.J.; Wang, X.J.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.P.; Mu, H.Y.; Li, F.T. The tuned Schottky barrier of a CoP co-catalyst via the bridge of ohmic contact from molybdenum metal for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 28830–28842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.D.; Li, X.T.; Yang, C.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Li, S.; Sun, X.; Tao, X. Large-size, porous, ultrathin NiCoP nanosheets for efficient electro/photocatalytic water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Li, W.T.; Li, Y.X.; Peng, S.Q.; Xu, Z. One-step synthesis of nickel oxide/nickel carbide/graphene composite for efficient dye-sensitized photocatalytic H2 evolution. Catal. Today 2019, 335, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blach, D.D.; Kern, D.B.S.; Wang, B.P.; Long, R.; Ma, Q.; Prezhdo, O.V.; Blackburn, J.L.; Huang, L. Long-range charge transport facilitated by electron delocalization in MoS2 and carbon nanotube heterostructures. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 3439–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Huang, B.B.; Wang, P. Single-atom modified graphene cocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction on halide perovskite. Chin. J. Catal. 2024, 64, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.K.; Wang, T.Z.; Zou, J.J.; Li, Y.D.; Zhang, C.J. Amorphous nickel oxides supported on carbon nanosheets as high-performance catalysts for electrochemical synthesis of hydrogen peroxide. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 5911–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.L.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, Z.R.; Lu, Q.Y.; Gao, F. Agaric-derived N-doped carbon nanorod arrays@nanosheet networks coupled with molybdenum carbide nanoparticles as highly efficient pH-universal hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 5159–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M.; Xie, X.J.; Huang, L. In situ exsolved Co components on wood ear-derived porous carbon for catalyzing oxygen reduction over a wide pH range. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 10695–10703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.L.; Song, F.X.; Zhou, L.J.; Chen, Q.L.; Pan, L.; Yang, M. Co1-xS/Co3S4@N, S-co-doped agaric-derived porous carbon composites for high-performance supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 426, 140825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, X.T.; Yu, J.; Cai, J.X.; Yang, Z.Y. Manganese monoxide/biomass-inherited porous carbon nanostructure composite based on the high water-absorbent agaric for asymmetric supercapacitor. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 4284–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.T.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Chen, D.L.; Sun, C.H.; Yang, Z.Y. A simple and recyclable molten-salt route to prepare superthin biocarbon sheets based on the high water-absorbent agaric for efficient lithium storage. Carbon 2020, 157, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Cui, Y.; Su, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, D.; Liao, Y.; Liu, S.; Fang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Lu, G.; Li, Z. Constructing a strong interfacial interaction in a Rh/RGO catalyst to boost photocatalytic hydrogen evolution under visible light irradiation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6(11), 6317–6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannath, K.A.; Shim, K.; Seo, K.D.; Saputra, H.A.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, H.J.; Park, D.S. A multifunctional Mo-N/Fe-N interfaced MoS2/FeNC electrocatalyst for energy conversion applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 10899–10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.Y.; Wang, K.N.; Yuan, C.; Chen, P.F.; Zhao, W.; Wang, A.J.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, W.H. Innovative bipyridine-bridged metal porphyrin polymer for robust and superior electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 5998–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Han, X.; Shen, W.W.; Ji, F.; Liu, M.L.; Song, Y.Y.; He, W.W. Construction of NiS/CTF heterojunction photocatalyst with an outstanding photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 9, 110415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Kil, H.S.; Kim, J.; Mochida, I.; Nakabayashi, K.; Rhee, C.K.; Miyawaki, J.; Yoon, S.H. Highly graphitized carbon from non-graphitizable raw material and its formation mechanism based on domain theory. Carbon 2017, 121, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Yu, S.J.; Zhang, Y.S.; Cheng, H.; Yang, X.X.; Li, Q.H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Zhou, H. Ni transformation and hydrochar properties during hydrothermal carbonization of cellulose. Fuel 2025, 382, 133772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Hou, Y.J.; Li, B. Facile synthesis of a hollow Ni–Fe–B nanochain and its enhanced catalytic activity for hydrogen generation from NaBH4 hydrolysis. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 25873–25880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Leng, Y.M.; Zhai, L.L.; Bao, C.Z.; Zhang, J.L.; Hou, J.K.; Xiang, Z.H. Hierarchical pore engineering of MOF-5 derived electrocatalysts with high mass transfer for zinc-air flow batteries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.W.; Du, P.; Liang, W.H.; Zhang, H.; Wu, P.; Cai, C.X.; Yan, Z.J. Single-atom-sized Ni–N4 sites anchored in three-dimensional hierarchical carbon nanostructures for the oxygen reduction reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 15012–15022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Nishchakova, A.D.; Trubina, S.V.; Stonkus, O.A.; Asanov, I.P.; Okotrub, A.V. Ni-N4 sites in a single-atom Ni catalyst on N-doped carbon for hydrogen production from formic acid. J. Catal. 2021, 402, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.B.; Wu, B.; Zhang, D.T.; Zhu, X.H.; Luo, S.Z.; You, Y.; Chen, K.; Long, J.C.; Zhu, J.X.; Liu, L.P.; Xi, S.B.; Petit, T.; Wang, D.S.; Zhang, X.M.; Xu, Z.C.; Mai, L.Q. Optimizing electronic synergy of atomically dispersed dual-metal Ni-N4 and Fe-N4 sites with adjacent Fe nanoclusters for high-efficiency oxygen electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.L.; Fu, C.L.; Li, D.M.; Ai, X.; Yin, H.Y.; Li, Y.H.; Li, X.Y.; Cao, L.Y.; Huang, J.F. High-density low-coordination Ni single atoms anchored on Ni-embedded nanoporous carbon nanotubes for boosted alkaline hydrogen evolution. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Bi, W.T.; Chen, M.L.; Sun, Y.X.; Ju, H.X.; Yan, W.S.; Zhu, J.F.; Wu, X.J.; Chu, W.S.; Wu, C.Z.; Xie, Y. Exclusive Ni-N4 sites realize near-unity CO selectivity for electrochemical CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14889–14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.C.; Long, S.S.; Chen, B.L.; Jia, W.L.; Xie, S.J.; Sun, Y.; Tang, X.; Yang, S.L.; Zeng, X.H.; Lin, L. Inducing electron dissipation of pyridinic N enabled by single Ni-N4 sites for the reduction of aldehydes/ketones with ethanol. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6398–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.F.; Liu, F.S.; Zang, X.C.; Xin, L.T.; Xiao, W.P.; Xu, G.R.; Li, H.; Li, Z.J.; Ma, T.Y.; Wang, J.S.; Wu, Z.X.; Wang, L. Microwave quasi-solid state to construct strong metal-support interactions with interfacial electron-enriched Ru for anion exchange membrane electrolysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoki, M.; Katoh, R. Estimation of quantum yields of weak fluorescence from eosin Y dimers formed in aqueous solutions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.J.; Seo, D.H.; Baek, J.H.; Kang, M.J.; Kim, S.K.; Zheng, X.L.; Cho, I.S. Crystal reconstruction of Mo:BiVO4: improved charge transport for efficient solar water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2208196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Peng, S.Q.; Cai, X. Enhancement of photocatalytic H2 evolution of eosin Y-sensitized reduced graphene oxide through a simple photoreaction. Beilstein J. Nanotech 2014, 5, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Tian, D.X.; Zhao, J.J. Computational design of ternary NiO/MPt interface active sites for H2O dissociation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 20040–20048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhao, G.Q.; Cui, P.X.; Cheng, N.Y.; Lao, M.M.; Xu, X.; Dou, S.X.; Sun, W.P. Nickel single atom-decorated carbon nanosheets as multifunctional electrocatalyst supports toward efficient alkaline hydrogen evolution. Nano Energy 2021, 83, 105850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.C.; Cao, L.S.; Wang, M.L.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, M.; Shao, Z.G. A robust Ni single-atom catalyst for industrial current and exceptional selectivity in electrochemical CO2 reduction to CO. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 8331–8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.L.; Fu, C.L.; Li, D.M.; Ai, X.; Yin, H.Y.; Li, Y.H.; Li, X.Y.; Cao, L.Y.; Huang, J.F. High-density low-coordination Ni single atoms anchored on Ni-embedded nanoporous carbon nanotubes for boosted alkaline hydrogen evolution. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).