Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

- This review conducts a thorough review of three widely employed generative models: VAEs, GANs, and diffusion models (DMs). We outline algorithms within these generative models that have found extensive applications in the domain of medical image analysis and provide analyses thereof.

- This review categorizes the applications of generative models in medical image analysis into creation and translation. We present an extensive review of creation methods and classify their downstream applications into three distinct categories: classification, segmentation, and others. We classify translation methods based on the target modality.

- This review organizes previous studies into categories and offer practical implementation guidelines gleaned from the lessons learned in these works.

2. Related Works

3. Methodology

4. Generative Models

4.1. Variational Autoencoder

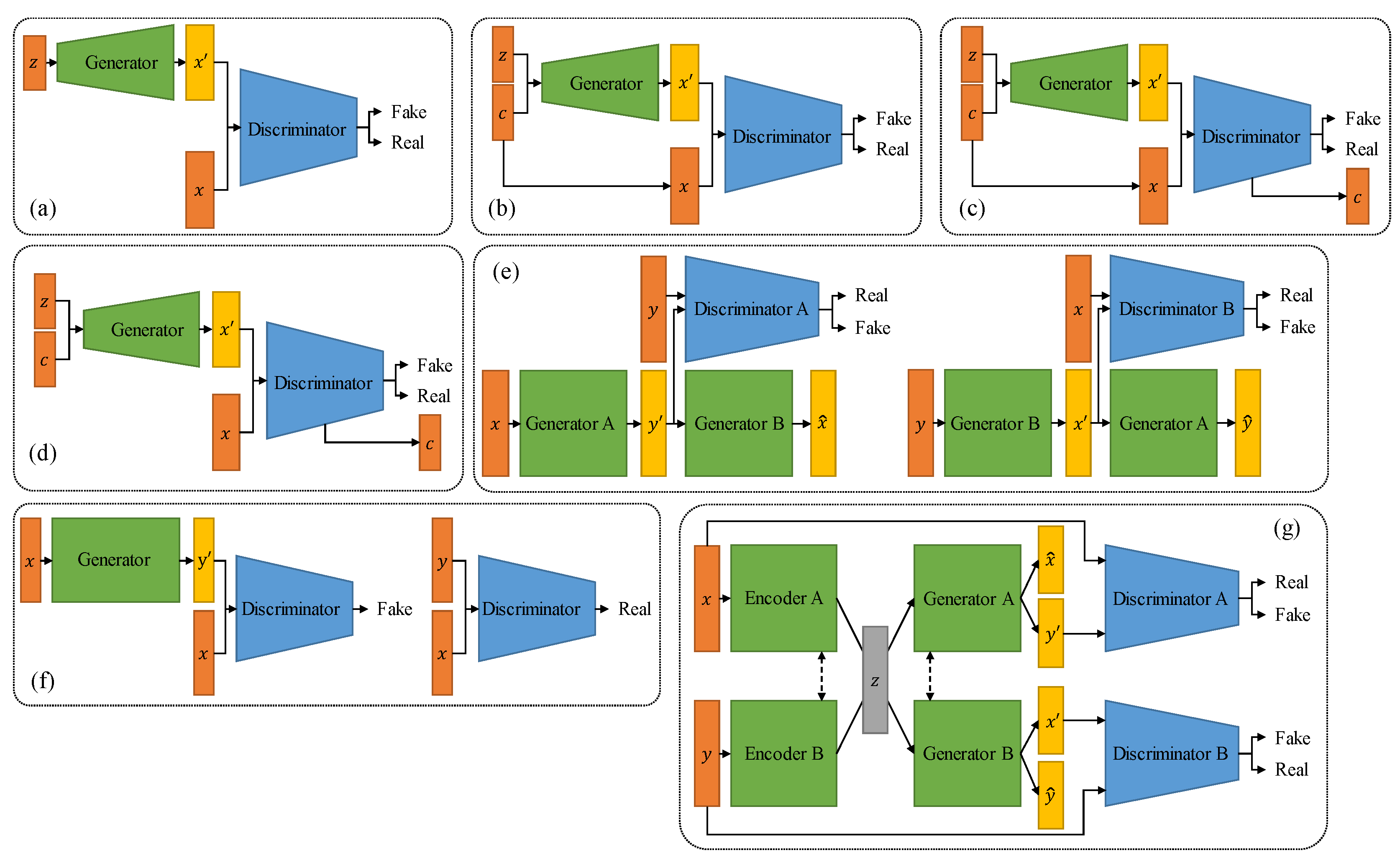

4.2. Generative Adversarial Network

4.3. Diffusion Model

5. Creation

5.1. Metrics of Medical Image Creation

5.2. Classification

5.3. Segmentation

5.4. Other Tasks

6. Translation

6.1. Metrics of Medical Image Translation

6.2. Generating MRI

6.2.1. Multi-Contrast MRI Synthesis

6.2.2. Generating MRI from Other Modalities

6.3. Generating CT

6.4. Generating X-Ray Image

6.5. Generating PET Image

6.6. Generating Ultrasound Image

6.7. Non-Contrast and Contrast-Enhanced Image

7. Discussion

7.1. Implementation Suggestion

7.1.1. Unified Model or Specific Task Model?

7.1.2. GAN or Diffusion Model?

7.1.3. Translation with Prior Knowledge

7.1.4. Other Possible Optimization Strategies for Training

7.2. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| CBCT | Cone Beam Computed Tomography | MRA | Magnetic Resonance Angiography |

| CT | Computed Tomography | MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DM | Diffusion Model | PD | Proton density image |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Image | PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance | PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| FLAIR | Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery | RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network | SSIM | Structural Similarity Index |

| IS | Inception Score | T1w | T1-weighted image |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error | T2w | T2-weighted image |

| MMD | Maximum Mean Discrepancy | US | Ultrasound imaging |

| MS | Mode Score | VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| MSE | Mean Square Error | WD | Wasserstein distance |

References

- X. Chen, X. Wang, K. Zhang, K.-M. Fung, T.C. Thai, K. Moore, R.S. Mannel, H. Liu, B. Zheng, Y.J.M.i.a. Qiu, Recent advances and clinical applications of deep learning in medical image analysis, Medical image analysis, 79 (2022) 102444. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, M.A. Chia, S.K. Wagner, M.S. Ayhan, D.J. Williamson, R.R. Struyven, T. Liu, M. Xu, M.G. Lozano, P.J.N. Woodward-Court, A foundation model for generalizable disease detection from retinal images, Nature, 622 (2023) 156-163. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma, Y. He, F. Li, L. Han, C. You, B.J.N.C. Wang, Segment anything in medical images, Nature Communications, 15 (2024) 654.

- K. Cao, Y. Xia, J. Yao, X. Han, L. Lambert, T. Zhang, W. Tang, G. Jin, H. Jiang, X.J.N.m. Fang, Large-scale pancreatic cancer detection via non-contrast CT and deep learning, Nature Medicine, 29 (2023) 3033-3043. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, Z. Zhuo, L. Qu, Y. Jin, T. Hua, J. Xu, G. Tan, Y. Li, Y. Duan, T.J.S.b. Wang, DeepWMH: A deep learning tool for accurate white matter hyperintensity segmentation without requiring manual annotations for training, Science Bulletin, (2024) S2095-9273 (2024) 00061-00066. [CrossRef]

- Q. Lu, W. Liu, Z. Zhuo, Y. Li, Y. Duan, P. Yu, L. Qu, C. Ye, Y.J.M.I.A. Liu, A transfer learning approach to few-shot segmentation of novel white matter tracts, Medical Image Analysis, 79 (2022) 102454. [CrossRef]

- W. Liu, Z. Zhuo, Y. Liu, C.J.M.I.A. Ye, One-shot segmentation of novel white matter tracts via extensive data augmentation and adaptive knowledge transfer, Medical Image Analysis, 90 (2023) 102968. [CrossRef]

- S. Vellmer, M. Tabelow, H. Zhang, Diffusion MRI GAN Synthesizing Fibre Orientation Distributions for White Matter Simulation, Communications Biology, 8 (2025) 7936. [CrossRef]

- G. Schuit, D. Parra, C. Besa, Perceptual Evaluation of GANs and Diffusion Models for Generating X-rays, arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.07128 (2025).

- O. O. Ejiga, M. Anifowose, L. Yuan, Advancing AI-Powered Medical Image Synthesis: Insights from the MedVQA-GI Challenge, arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.20667 (2025).

- Z. Yang, Y. Li, W. Wang, seg2med: A Segmentation-based Medical Image Generation Framework Using Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.09182 (2025).

- C. Zhao, P. Guo, Y. Xu, MAISI-v2: Accelerated 3D High-Resolution Medical Image Synthesis with Rectified Flow and Region-specific Contrastive Loss, arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.05772 (2025).

- J. Kim, S. Lee, FMed-Diffusion: Federated Learning on Medical Image Diffusion Models for Privacy-Preserving Data Generation, bioRxiv preprint (2025).

- T. Chakraborty, S.M. Naik, M. Panja, B. Manvitha, Ten Years of Generative Adversarial Nets (GANs): A survey of the state-of-the-art, arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16316, (2023). [CrossRef]

- E. Goceri, Medical image data augmentation: techniques, comparisons and interpretations, Artificial Intelligence Review, (2023) 1-45. [CrossRef]

- Kebaili, J. Lapuyade-Lahorgue, S. Ruan, Deep Learning Approaches for Data Augmentation in Medical Imaging: A Review, Journal of Imaging, 9 (2023) 81. [CrossRef]

- S. Dayarathna, K.T. Islam, S. Uribe, G. Yang, M. Hayat, Z. Chen, Deep learning based synthesis of MRI, CT and PET: Review and analysis, Medical Image Analysis, (2023) 103046. [CrossRef]

- T.H. Wang, Y. Lei, Y.B. Fu, J.F. Wynne, W.J. Curran, T. Liu, X.F. Yang, A review on medical imaging synthesis using deep learning and its clinical applications, Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics, 22 (2021) 11-36. [CrossRef]

- X. Yi, E. Walia, P. Babyn, Generative adversarial network in medical imaging: A review, Medical Image Analysis, 58 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Kazeminia, C. Baur, A. Kuijper, B. van Ginneken, N. Navab, S. Albarqouni, A. Mukhopadhyay, GANs for medical image analysis, Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, 109 (2020) 101938.

- Y.Z. Chen, X.H. Yang, Z.H. Wei, A.A. Heidari, N.G. Zheng, Z.C. Li, H.L. Chen, H.G. Hu, Q.W. Zhou, Q. Guan, Generative Adversarial Networks in Medical Image augmentation: A review, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 144 (2022). [CrossRef]

- R. Osuala, K. Kushibar, L. Garrucho, A. Linardos, Z. Szafranowska, S. Klein, B. Glocker, O. Diaz, K. Lekadir, Data synthesis and adversarial networks: A review and meta-analysis in cancer imaging, Medical Image Analysis, (2022) 102704. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, X.Y. Hou, M.Q. Pan, H. Zhang, Attention-based generative adversarial network in medical imaging: A narrative review, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 149 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A.F. Frangi, S.A. Tsaftaris, J.L. Prince, Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 37 (2018) 673-679. [CrossRef]

- A. Oussidi, A. Elhassouny, Deep generative models: Survey, 2018 International conference on intelligent systems and computer vision (ISCV), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1-8.

- D.P. Kingma, M. Welling, Auto-encoding variational bayes, arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114, (2013).

- T. Salimans, D. Kingma, M. Welling, Markov chain monte carlo and variational inference: Bridging the gap, International conference on machine learning, PMLR, 2015, pp. 1218-1226.

- T.D. Kulkarni, W.F. Whitney, P. Kohli, J. Tenenbaum, Deep convolutional inverse graphics network, Advances in neural information processing systems, 28 (2015).

- K. Gregor, I. Danihelka, A. Graves, D. Rezende, D. Wierstra, Draw: A recurrent neural network for image generation, International conference on machine learning, PMLR, 2015, pp. 1462-1471.

- M. Pesteie, P. Abolmaesumi, R.N. Rohling, Adaptive augmentation of medical data using independently conditional variational auto-encoders, IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 38 (2019) 2807-2820. [CrossRef]

- L.Y.H. Alex, J. Galeotti, Ultrasound Variational Style Transfer to Generate Images Beyond the Observed Domain, 1st Workshop on Deep Generative Models for Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (DGM4MICCAI) / 1st MICCAI Workshop on Data Augmentation, Labelling, and Imperfections (DALI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 14-23.

- R. Wei, A. Mahmood, Recent advances in variational autoencoders with representation learning for biomedical informatics: A survey, Ieee Access, 9 (2020) 4939-4956. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, J. Pouget-Abadie, M. Mirza, B. Xu, D. Warde-Farley, S. Ozair, A. Courville, Y. Bengio, Generative adversarial networks, Communications of the ACM, 63 (2020) 139-144.

- Kazerouni, E.K. Aghdam, M. Heidari, R. Azad, M. Fayyaz, I. Hacihaliloglu, D. Merhof, Diffusion models in medical imaging: A comprehensive survey, Medical Image Analysis, (2023) 102846. [CrossRef]

- P. Isola, J.-Y. Zhu, T. Zhou, A.A. Efros, Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1125-1134.

- J.-Y. Zhu, T. Park, P. Isola, A.A. Efros, Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks, Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2223-2232.

- B. Sun, S.F. Jia, X.L. Jiang, F.C. Jia, Double U-Net CycleGAN for 3D MR to CT image synthesis, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, (2023). [CrossRef]

- S.U.H. Dar, M. Yurt, L. Karacan, A. Erdem, E. Erdem, T. Cukur, Image Synthesis in Multi-Contrast MRI With Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 38 (2019) 2375-2388. [CrossRef]

- H. Pang, S. Qi, Y. Wu, M. Wang, C. Li, Y. Sun, W. Qian, G. Tang, J. Xu, Z. Liang, NCCT-CECT image synthesizers and their application to pulmonary vessel segmentation, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 231 (2023) 107389. [CrossRef]

- S. Pan, T. Wang, R.L. Qiu, M. Axente, C.-W. Chang, J. Peng, A.B. Patel, J. Shelton, S.A. Patel, J. Roper, 2D medical image synthesis using transformer-based denoising diffusion probabilistic model, Physics in Medicine & Biology, 68 (2023) 105004. [CrossRef]

- Z. Dorjsembe, S. Odonchimed, F. Xiao, Three-dimensional medical image synthesis with denoising diffusion probabilistic models, Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, 2022.

- M. Özbey, O. Dalmaz, S.U. Dar, H.A. Bedel, Ş. Özturk, A. Güngör, T. Çukur, Unsupervised medical image translation with adversarial diffusion models, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Z.-X. Cui, C. Cao, S. Liu, Q. Zhu, J. Cheng, H. Wang, Y. Zhu, D. Liang, Self-score: Self-supervised learning on score-based models for mri reconstruction, arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.00835, (2022).

- C. Peng, P. Guo, S.K. Zhou, V.M. Patel, R. Chellappa, Towards performant and reliable undersampled MR reconstruction via diffusion model sampling, International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Springer, 2022, pp. 623-633.

- D. Hu, Y.K. Tao, I. Oguz, Unsupervised denoising of retinal OCT with diffusion probabilistic model, Medical Imaging 2022: Image Processing, SPIE, 2022, pp. 25-34.

- B. Kim, I. Han, J.C. Ye, DiffuseMorph: unsupervised deformable image registration using diffusion model, European Conference on Computer Vision, Springer, 2022, pp. 347-364.

- Y. Yang, H. Fu, A. Aviles-Rivero, C.-B. Schönlieb, L. Zhu, DiffMIC: Dual-Guidance Diffusion Network for Medical Image Classification, arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10610, (2023).

- Rahman, J.M.J. Valanarasu, I. Hacihaliloglu, V.M. Patel, Ambiguous medical image segmentation using diffusion models, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 11536-11546.

- J. Wolleb, R. Sandkühler, F. Bieder, P. Valmaggia, P.C. Cattin, Diffusion models for implicit image segmentation ensembles, International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, PMLR, 2022, pp. 1336-1348.

- S.-C. Huang, A. Pareek, M. Jensen, M.P. Lungren, S. Yeung, A.S. Chaudhari, Self-supervised learning for medical image classification: a systematic review and implementation guidelines, NPJ Digital Medicine, 6 (2023) 74. [CrossRef]

- A. Obukhov, M. Krasnyanskiy, Quality assessment method for GAN based on modified metrics inception score and Fréchet inception distance, Software Engineering Perspectives in Intelligent Systems: Proceedings of 4th Computational Methods in Systems and Software 2020, Vol. 1 4, Springer, 2020, pp. 102-114.

- E. Miranda, M. Aryuni, E. Irwansyah, A survey of medical image classification techniques, 2016 international conference on information management and technology (ICIMTech), IEEE, 2016, pp. 56-61.

- L. Gao, L. Zhang, C. Liu, S.J.A.i.i.m. Wu, Handling imbalanced medical image data: A deep-learning-based one-class classification approach, 108 (2020) 101935. [CrossRef]

- H. Salehinejad, E. Colak, T. Dowdell, J. Barfett, S. Valaee, Synthesizing Chest X-Ray Pathology for Training Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 38 (2019) 1197-1206. [CrossRef]

- S.Y. Pan, T.H. Wang, R.L.J. Qiu, M. Axente, C.W. Chang, J.B. Peng, A.B. Patel, J. Shelton, S.A. Patel, J. Roper, X.F. Yang, 2D medical image synthesis using transformer-based denoising diffusion probabilistic model, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 68 (2023).

- P. Chlap, H. Min, N. Vandenberg, J. Dowling, L. Holloway, A.J.J.o.M.I. Haworth, R. Oncology, A review of medical image data augmentation techniques for deep learning applications, 65 (2021) 545-563. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Kaissis, M.R. Makowski, D. Rückert, R.F.J.N.M.I. Braren, Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging, 2 (2020) 305-311. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, T. Lei, R. Cui, B. Zhang, H. Meng, A.K.J.I.I.P. Nandi, Medical image segmentation using deep learning: A survey, 16 (2022) 1243-1267. [CrossRef]

- P.F. Guo, P.Y. Wang, R. Yasarla, J.Y. Zhou, V.M. Patel, S.S. Jiang, Anatomic and Molecular MR Image Synthesis Using Confidence Guided CNNs, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 40 (2021) 2832-2844. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, L.D. Yu, D.C. Chen, W.D. Pan, C. Shi, Y. Niu, X.W. Yao, X.B. Xu, Y. Cheng, Dense GAN and multi-layer attention based lesion segmentation method for COVID-19 CT images, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 69 (2021). [CrossRef]

- S. Amirrajab, C. Lorenz, J. Weese, J. Pluim, M. Breeuwer, Pathology Synthesis of 3D Consistent Cardiac MR Images Using 2D VAEs and GANs, 7th International Workshop on Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging (SASHIMI)Singapore, SINGAPORE, 2022, pp. 34-42.

- C. Han, Y. Kitamura, A. Kudo, A. Ichinose, L. Rundo, Y. Furukawa, K. Umemoto, Y.Z. Li, H. Nakayama, I.C. Soc, Synthesizing Diverse Lung Nodules Wherever Massively: 3D Multi-Conditional GAN-based CT Image Augmentation for Object Detection, 7th International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV)Quebec City, CANADA, 2019, pp. 729-737. [CrossRef]

- A. Kamli, R. Saouli, H. Batatia, M.B. Ben Naceur, I. Youkana, Synthetic medical image generator for data augmentation and anonymisation based on generative adversarial network for glioblastoma tumors growth prediction, Iet Image Processing, 14 (2020) 4248-4257.

- Z.Y. Li, Q.Y. Fan, B. Bilgic, G.Z. Wang, W.C. Wu, J.R. Polimeni, K.L. Miller, S.Y. Huang, Q.Y. Tian, Diffusion MRI data analysis assisted by deep learning synthesized anatomical images (DeepAnat), Medical Image Analysis, 86 (2023).

- M. Frid-Adar, I. Diamant, E. Klang, M. Amitai, J. Goldberger, H. Greenspan, GAN-based synthetic medical image augmentation for increased CNN performance in liver lesion classification, Neurocomputing, 321 (2018) 321-331. [CrossRef]

- Q.Q. Zhang, H.F. Wang, H.Y. Lu, D. Won, S.W. Yoon, I.C. Soc, Medical Image Synthesis with Generative Adversarial Networks for Tissue Recognition, 6th IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI)New York, NY, 2018, pp. 199-207.

- Y.J. Lin, I.F. Chung, Ieee, Medical Data Augmentation Using Generative Adversarial Networks X-ray Image Generation for Transfer Learning of Hip Fracture Detection, International Conference on Technologies and Applications of Artficial Intelligence (TAAI)Kaohsiung, TAIWAN, 2019.

- J. Yang, S.Q. Liu, S. Grbic, A.A.A. Setio, Z.B. Xu, E. Gibson, G. Chabin, B. Georgescu, A.F. Laine, D. Comaniciu, Ieee, CLASS-AWARE ADVERSARIAL LUNG NODULE SYNTHESIS IN CT IMAGES, 16th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Venice, ITALY, 2019, pp. 1348-1352.

- R.Z.J. Choong, S.A. Harding, B.Y. Tang, S.W. Liao, Ieee, 3-To-1 Pipeline: Restructuring Transfer Learning Pipelines for Medical Imaging Classification via Optimized GAN Synthetic Images, 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE-Engineering-in-Medicine-and-Biology-Society (EMBC)Montreal, CANADA, 2020, pp. 1596-1599.

- S. Menon, J. Galita, D. Chapman, A. Gangopadhyay, J. Mangalagiri, P. Nguyen, Y. Yesha, Y. Yesha, B. Saboury, M. Morris, Generating Realistic COVID-19 x-rays with a Mean Teacher plus Transfer Learning GAN, 8th IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data)Electr Network, 2020, pp. 1216-1225.

- P. Ahmad, Y. Wang, M. Havaei, CT-SGAN: Computed Tomography Synthesis GAN, 1st Workshop on Deep Generative Models for Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (DGM4MICCAI) / 1st MICCAI Workshop on Data Augmentation, Labelling, and Imperfections (DALI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 67-79.

- A.A.E. Ambita, E.N.V. Boquio, P.C. Naval, COViT-GAN: Vision Transformer for COVID-19 Detection in CT Scan Images with Self-Attention GAN for Data Augmentation, 30th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ICANN)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 587-598.

- H. Che, S. Ramanathan, D.J. Foran, J.L. Nosher, V.M. Patel, I. Hacihaliloglu, Realistic Ultrasound Image Synthesis for Improved Classification of Liver Disease, 2nd International Workshop on Advances in Simplifying Medical UltraSound (ASMUS)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 179-188.

- T. Pang, J.H.D. Wong, W.L. Ng, C.S. Chan, Semi-supervise d GAN-base d Radiomics Model for Data Augmentation in Breast Ultrasound Mass Classification, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 203 (2021). [CrossRef]

- R. Toda, A. Teramoto, M. Tsujimoto, H. Toyama, K. Imaizumi, K. Saito, H. Fujita, Synthetic CT image generation of shape-controlled lung cancer using semi-conditional InfoGAN and its applicability for type classification, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 16 (2021) 241-251. [CrossRef]

- S.K. Venu, Improving the Generalization of Deep Learning Classification Models in Medical Imaging Using Transfer Learning and Generative Adversarial Networks, 13th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 218-235.

- G.Y. Zhang, K.X. Chen, S.L. Xu, P.C.A. Cho, Y. Nan, X. Zhou, C.A.F. Lv, C.S. Li, G.T. Xie, Lesion synthesis to improve intracranial hemorrhage detection and classification for CT images, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 90 (2021). [CrossRef]

- R.N. Abirami, P. Vincent, V. Rajinikanth, S. Kadry, COVID-19 Classification Using Medical Image Synthesis by Generative Adversarial Networks, International Journal of Uncertainty Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems, 30 (2022) 385-401. [CrossRef]

- A. Fernandez-Quilez, O. Parvez, T. Eftestol, S.R. Kjosavik, K. Oppedal, Improving prostate cancer triage with GAN-based synthetically generated prostate ADC MRI, Conference on Medical Imaging - Computer-Aided DiagnosisElectr Network, 2022.

- Q. Guan, Y.Z. Chen, Z.H. Wei, A.A. Heidari, H.G. Hu, X.H. Yang, J.W. Zheng, Q.W. Zhou, H.L. Chen, F. Chen, Medical image augmentation for lesion detection using a texture-constrained multichannel progressive GAN, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 145 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Z. Liang, J.X. Huang, S. Antani, Image translation by Ad cycleGAN for COVID-19 X-ray images: A new approach for controllable GAN, Sensors, 22 (2022) 9628. [CrossRef]

- J.W. Mao, X.S. Yin, G.D. Zhang, B.W. Chen, Y.Q. Chang, W.B. Chen, J.Y. Yu, Y.G. Wang, Pseudo-labeling generative adversarial networks for medical image classification, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 147 (2022). [CrossRef]

- D.I. Moris, J. de Moura, J. Novo, M. Ortega, Unsupervised contrastive unpaired image generation approach for improving tuberculosis screening using chest X-ray images, Pattern Recognition Letters, 164 (2022) 60-66. [CrossRef]

- E. Ovalle-Magallanes, J.G. Avina-Cervantes, I. Cruz-Aceves, J. Ruiz-Pinales, Improving convolutional neural network learning based on a hierarchical bezier generative model for stenosis detection in X-ray images, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 219 (2022). [CrossRef]

- P.M. Shah, H. Ullah, R. Ullah, D. Shah, Y.L. Wang, S. ul Islam, A. Gani, J. Rodrigues, DC-GAN-based synthetic X-ray images augmentation for increasing the performance of EfficientNet for COVID-19 detection, Expert Systems, 39 (2022).

- Y.F. Chen, Y.L. Lin, X.D. Xu, J.Z. Ding, C.Z. Li, Y.M. Zeng, W.F. Xie, J.L. Huang, Multi-domain medical image translation generation for lung image classification based on generative adversarial networks, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 229 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, J.H. Lee, C. Kim, K.N. Jin, C.M. Park, GAN based ROI conditioned Synthesis of Medical Image for Data Augmentation, Conference on Medical Imaging - Image ProcessingSan Diego, CA, 2023.

- A. Wali, M. Ahmad, A. Naseer, M. Tamoor, S.A.M. Gilani, StynMedGAN: Medical images augmentation using a new GAN model for improved diagnosis of diseases, Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 44 (2023) 10027-10044. [CrossRef]

- F. Tom, D. Sheet, Ieee, SIMULATING PATHO-REALISTIC ULTRASOUND IMAGES USING DEEP GENERATIVE NETWORKS WITH ADVERSARIAL LEARNING, 15th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Washington, DC, 2018, pp. 1174-1177.

- L. Bargsten, A. Schlaefer, SpeckleGAN: a generative adversarial network with an adaptive speckle layer to augment limited training data for ultrasound image processing, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 15 (2020) 1427-1436. [CrossRef]

- N.J. Cronin, T. Finni, O. Seynnes, Using deep learning to generate synthetic B-mode musculoskeletal ultrasound images, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 196 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y.L. Qu, W.Q. Su, X. Lv, C.F. Deng, Y. Wang, Y.T. Lu, Z.G. Chen, N. Xiao, Synthesis of Registered Multimodal Medical Images with Lesions, 29th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks (ICANN)Bratislava, SLOVAKIA, 2020, pp. 774-786.

- A. Zama, S.H. Park, H. Bang, C.W. Park, I. Park, S. Joung, Generative approach for data augmentation for deep learning-based bone surface segmentation from ultrasound images, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 15 (2020) 931-941. [CrossRef]

- A. Fernandez-Quilez, S.V. Larsen, M. Goodwin, T.O. Gulsrud, S.R. Kjosavik, K. Oppedal, Ieee, IMPROVING PROSTATE WHOLE GLAND SEGMENTATION IN T2-WEIGHTED MRI WITH SYNTHETICALLY GENERATED DATA, 18th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Nice, FRANCE, 2021, pp. 1915-1919.

- J.Z. Liang, J.Y. Chen, Ieee, Data Augmentation of Thyroid Ultrasound Images Using Generative Adversarial Network, IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IEEE IUS)Electr Network, 2021.

- S.Z. Yao, J.H. Tan, Y. Chen, Y.H. Gu, A weighted feature transfer gan for medical image synthesis, Machine Vision and Applications, 32 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J. Gao, W.H. Zhao, P. Li, W. Huang, Z.K. Chen, LEGAN: A Light and Effective Generative Adversarial Network for medical image synthesis, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 148 (2022). [CrossRef]

- J.M. Liang, X. Yang, Y.H. Huang, H.M. Li, S.C. He, X.D. Hu, Z.J. Chen, W.F. Xue, J. Cheng, D. Ni, Sketch guided and progressive growing GAN for realistic and editable ultrasound image synthesis, Medical Image Analysis, 79 (2022). [CrossRef]

- D. Lustermans, S. Amirrajab, M. Veta, M. Breeuwer, C.M. Scannell, Optimized automated cardiac MR scar quantification with GAN-based data augmentation, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 226 (2022). [CrossRef]

- F. Lyu, M. Ye, A.J. Ma, T.C.F. Yip, G.L.H. Wong, P.C. Yuen, Learning From Synthetic CT Images via Test-Time Training for Liver Tumor Segmentation, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41 (2022) 2510-2520. [CrossRef]

- M. Platscher, J. Zopes, C. Federau, Image translation for medical image generation: Ischemic stroke lesion segmentation, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 72 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S. Sasuga, A. Kudo, Y. Kitamura, S. Iizuka, E. Simo-Serra, A. Hamabe, M. Ishii, I. Takemasa, Image Synthesis-Based Late Stage Cancer Augmentation and Semi-supervised Segmentation for MRI Rectal Cancer Staging, 2nd MICCAI International Workshop on Data Augmentation, Labeling, and Imperfections (DALI)Singapore, SINGAPORE, 2022, pp. 1-10.

- S. Shabani, M. Homayounfar, V. Vardhanabhuti, M.A.N. Mahani, M. Koohi-Moghadam, Self-supervised region-aware segmentation of COVID-19 CT images using 3D GAN and contrastive learning, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 149 (2022). [CrossRef]

- I. Sirazitdinov, H. Schulz, A. Saalbach, S. Renisch, D.V. Dylov, Tubular shape aware data generation for segmentation in medical imaging, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 17 (2022) 1091-1099. [CrossRef]

- D. Tomar, B. Bozorgtabar, M. Lortkipanidze, G. Vray, M.S. Rad, J.P. Thiran, I.C. Soc, Self-Supervised Generative Style Transfer for One-Shot Medical Image Segmentation, 22nd IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV)Waikoloa, HI, 2022, pp. 1737-1747.

- A. Beji, A.G. Blaiech, M. Said, A. Ben Abdallah, M.H. Bedoui, An innovative medical image synthesis based on dual GAN deep neural networks for improved segmentation quality, Applied Intelligence, 53 (2023) 3381-3397. [CrossRef]

- J. Mendes, T. Pereira, F. Silva, J. Frade, J. Morgado, C. Freitas, E. Negrao, B.F. de Lima, M.C. da Silva, A.J. Madureira, I. Ramos, J.L. Costa, V. Hespanhol, A. Cunha, H.P. Oliveira, Lung CT image synthesis using GANs, Expert Systems with Applications, 215 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Z.R. Shen, X. Ouyang, B. Xiao, J.Z. Cheng, D.G. Shen, Q. Wang, Image synthesis with disentangled attributes for chest X-ray nodule augmentation and detection, Medical Image Analysis, 84 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Xing, G. Papanastasiou, S. Walsh, G. Yang, Less is More: Unsupervised Mask-guided Annotated CT Image Synthesis with Minimum Manual Segmentations, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y.P. Zhang, Q. Wang, B.L. Hu, MinimalGAN: diverse medical image synthesis for data augmentation using minimal training data, Applied Intelligence, (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Han, H. Hayashi, L. Rundo, R. Araki, W. Shimoda, S. Muramatsu, Y. Furukawa, G. Mauri, H. Nakayama, Ieee, GAN-BASED SYNTHETIC BRAIN MR IMAGE GENERATION, 15th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Washington, DC, 2018, pp. 734-738.

- L.H. Lee, J.A. Noble, Ieee, GENERATING CONTROLLABLE ULTRASOUND IMAGES OF THE FETAL HEAD, IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Iowa, IA, 2020, pp. 1761-1764.

- Z.W. Wang, Y. Lin, K.T. Cheng, X. Yang, Semi-supervised mp-MRI data synthesis with StitchLayer and auxiliary distance maximization, Medical Image Analysis, 59 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J.A. Rodriguez-de-la-Cruz, H.G. Acosta-Mesa, E. Mezura-Montes, Ieee, Evolution of Generative Adversarial Networks Using PSO for Synthesis of COVID-19 Chest X-ray Images, IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (IEEE CEC)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 2226-2233.

- Z.R. Shen, X. Ouyang, Z.C. Wang, Y.Q. Zhan, Z. Xue, Q. Wang, J.Z. Cheng, D.G. Shen, Nodule Synthesis and Selection for Augmenting Chest X-ray Nodule Detection, 4th Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV)Univ Sci & Technol Beijing, Zhuhai, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2021, pp. 536-547.

- H. Sungmin, R. Marinescu, A.V. Dalca, A.K. Bonkhoff, M. Bretzner, N.S. Rost, P. Golland, 3D-StyleGAN: A Style-Based Generative Adversarial Network for Generative Modeling of Three-Dimensional Medical Images, 1st Workshop on Deep Generative Models for Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (DGM4MICCAI) / 1st MICCAI Workshop on Data Augmentation, Labelling, and Imperfections (DALI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 24-34.

- M.U. Kiru, B. Belaton, X. Chew, K.H. Almotairi, A.M. Hussein, M. Aminu, Comparative analysis of some selected generative adversarial network models for image augmentation: a case study of COVID-19 x-ray and CT images, Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 43 (2022) 7153-7172. [CrossRef]

- B. Cepa, C. Brito, A. Sousa, Ieee, Generative Adversarial Networks in Healthcare: A Case Study on MRI Image Generation, IEEE 7th Portuguese Meeting on Bioengineering (ENBENG)Porto, PORTUGAL, 2023, pp. 48-51.

- L. Kong, C. Lian, D. Huang, Y. Hu, Q.J.A.i.N.I.P.S. Zhou, Breaking the dilemma of medical image-to-image translation, 34 (2021) 1964-1978.

- J. Korhonen, J. You, Peak signal-to-noise ratio revisited: Is simple beautiful?, 2012 Fourth International Workshop on Quality of Multimedia Experience, IEEE, 2012, pp. 37-38.

- D. Brunet, E.R. Vrscay, Z.J.I.T.o.I.P. Wang, On the mathematical properties of the structural similarity index, 21 (2011) 1488-1499. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharma, G. Hamarneh, Missing MRI Pulse Sequence Synthesis Using Multi-Modal Generative Adversarial Network, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39 (2020) 1170-1183. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhou, H.Z. Fu, G. Chen, J.B. Shen, L. Shao, Hi-Net: Hybrid-Fusion Network for Multi-Modal MR Image Synthesis, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39 (2020) 2772-2781. [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Wang, Q.M.J. Wu, F. Pourpanah, DC-cycleGAN: Bidirectional CT-to-MR synthesis from unpaired data, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 108 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Lei, T.H. Wang, S.B. Tian, X. Dong, A.B. Jani, D. Schuster, W.J. Curran, P. Patel, T. Liu, X.F. Yang, Male pelvic multi-organ segmentation aided by CBCT-based synthetic MRI, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Bazangani, F.J. Richard, B. Ghattas, E. Guedj, FDG-PET to T1 Weighted MRI Translation with 3D Elicit Generative Adversarial Network (E-GAN), Sensors, 22 (2022) 4640. [CrossRef]

- B.T. Yu, L.P. Zhou, L. Wang, J. Fripp, P. Bourgeat, Ieee, 3D CGAN BASED CROSS-MODALITY MR IMAGE SYNTHESIS FOR BRAIN TUMOR SEGMENTATION, 15th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Washington, DC, 2018, pp. 626-630.

- B. Yu, L. Zhou, L. Wang, Y. Shi, J. Fripp, P. Bourgeat, Ea-GANs: edge-aware generative adversarial networks for cross-modality MR image synthesis, IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 38 (2019) 1750-1762. [CrossRef]

- B. Cao, H. Zhang, N.N. Wang, X.B. Gao, D.G. Shen, I. Assoc Advancement Artificial, Auto-GAN: Self-Supervised Collaborative Learning for Medical Image Synthesis, 34th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence / 32nd Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference / 10th AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial IntelligenceNew York, NY, 2020, pp. 10486-10493.

- A.Z.M. Shen, B.Y.F. Chen, C.K.S. Zhou, D.B. Georgescu, E.X.Q. Liu, F.T.S. Huang, Ieee, LEARNING A SELF-INVERSE NETWORK FOR BIDIRECTIONAL MRI IMAGE SYNTHESIS, IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Iowa, IA, 2020, pp. 1765-1769.

- K. Wu, Y. Qiang, K. Song, X.T. Ren, W.K. Yang, W.J. Zhang, A. Hussain, Y.F. Cui, Image synthesis in contrast MRI based on super resolution reconstruction with multi-refinement cycle-consistent generative adversarial networks, Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 31 (2020) 1215-1228. [CrossRef]

- B.Y. Xin, Y.F. Hu, Y.F. Zheng, O.G. Liao, Ieee, MULTI-MODALITY GENERATIVE ADVERSARIAL NETWORKS WITH TUMOR CONSISTENCY LOSS FOR BRAIN MR IMAGE SYNTHESIS, IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Iowa, IA, 2020, pp. 1803-1807.

- B.T. Yu, L.P. Zhou, L. Wang, Y.H. Shi, J. Fripp, P. Bourgeat, Sample-Adaptive GANs: Linking Global and Local Mappings for Cross-Modality MR Image Synthesis, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39 (2020) 2339-2350. [CrossRef]

- M. Islam, N. Wijethilake, H.L. Ren, Glioblastoma multiforme prognosis: MRI missing modality generation, segmentation and radiogenomic survival prediction, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 91 (2021).

- V. Kumar, M.K. Sharma, R. Jehadeesan, B. Venkatraman, G. Suman, A. Patra, A.H. Goenka, D. Sheet, Ieee, Learning to Generate Missing Pulse Sequence in MRI using Deep Convolution Neural Network Trained with Visual Turing Test, 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE-Engineering-in-Medicine-and-Biology-Society (IEEE EMBC)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 3419-3422.

- Y.M. Luo, D. Nie, B. Zhan, Z.A. Li, X. Wu, J.L. Zhou, Y. Wang, D.G. Shen, Edge-preserving MRI image synthesis via adversarial network with iterative multi-scale fusion, Neurocomputing, 452 (2021) 63-77. [CrossRef]

- M.W. Ren, H. Kim, N. Dey, G. Gerig, Q-space Conditioned Translation Networks for Directional Synthesis of Diffusion Weighted Images from Multi-modal Structural MRI, International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 530-540.

- U. Upadhyay, V.P. Sudarshan, S.P. Awate, I.C. Soc, Uncertainty-aware GAN with Adaptive Loss for Robust MRI Image Enhancement, 18th IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 3248-3257.

- C.J. Wang, G. Yang, G. Papanastasiou, S.A. Tsaftaris, D.E. Newby, C. Gray, G. Macnaught, T.J. MacGillivray, DiCyc: GAN-based deformation invariant cross-domain information fusion for medical image synthesis, Information Fusion, 67 (2021) 147-160. [CrossRef]

- K. Yan, Z.Z. Liu, S. Zheng, Z.Y. Guo, Z.F. Zhu, Y. Zhao, Coarse-to-Fine Learning Framework for Semi-supervised Multimodal MRI Synthesis, 6th Asian Conference on Pattern Recognition (ACPR)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 370-384.

- H.R. Yang, J. Sun, L.W. Yang, Z.B. Xu, A Unified Hyper-GAN Model for Unpaired Multi-contrast MR Image Translation, International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 127-137.

- M. Yurt, S.U.H. Dar, A. Erdem, E. Erdem, K.K. Oguz, T. Cukur, mustGAN: multi-stream Generative Adversarial Networks for MR Image Synthesis, Medical Image Analysis, 70 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B. Zhan, D. Li, Y. Wang, Z.Q. Ma, X. Wu, J.L. Zhou, L.P. Zhou, LR-cGAN: Latent representation based conditional generative adversarial network for multi-modality MRI synthesis, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- T.X. Zhou, S. Canu, P. Vera, S. Ruan, Feature-enhanced generation and multi-modality fusion based deep neural network for brain tumor segmentation with missing MR modalities, Neurocomputing, 466 (2021) 102-112. [CrossRef]

- N.Y. Zhu, C. Liu, X.Y. Feng, D. Sikka, S. Gjerswold-Selleck, S.A. Small, J. Guo, I. Alzheimer’s Dis Neuroimaging, Ieee, DEEP LEARNING IDENTIFIES NEUROIMAGING SIGNATURES OF ALZHEIMERiS DISEASE USING STRUCTURAL AND SYNTHESIZED FUNCTIONAL MRI DATA, 18th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Nice, FRANCE, 2021, pp. 216-220.

- H.A. Amirkolaee, D.O. Bokov, H. Sharma, Development of a GAN architecture based on integrating global and local information for paired and unpaired medical image translation, Expert Systems with Applications, 203 (2022). [CrossRef]

- O. Dalmaz, M. Yurt, T. Cukur, ResViT: Residual Vision Transformers for Multimodal Medical Image Synthesis, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41 (2022) 2598-2614. [CrossRef]

- P. Huang, D.W. Li, Z.C. Jiao, D.M. Wei, B. Cao, Z.H. Mo, Q. Wang, H. Zhang, D.G. Shen, Common feature learning for brain tumor MRI synthesis by context-aware generative adversarial network, Medical Image Analysis, 79 (2022).

- J.X. Li, H.J. Chen, Y.F. Li, Y.H. Peng, J. Sun, P. Pan, Cross-modality synthesis aiding lung tumor segmentation on multi-modal MRI images, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 76 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Lin, H. Han, S.K. Zhou, Ieee, DEEP NON-LINEAR EMBEDDING DEFORMATION NETWORK FOR CROSS-MODAL BRAIN MRI SYNTHESIS, 19th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (IEEE ISBI)Kolkata, INDIA, 2022.

- L.M. Xu, H. Zhang, L.Y. Song, Y.R. Lei, Bi-MGAN: Bidirectional T1-to-T2 MRI images prediction using multi-generative multi-adversarial nets, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 78 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Yurt, M. Ozbey, S.U.H. Dar, B. Tinaz, K.K. Oguz, T. Cukur, Progressively volumetrized deep generative models for data-efficient contextual learning of MR image recovery, Medical Image Analysis, 78 (2022). [CrossRef]

- B. Zhan, L. Zhou, Z. Li, X. Wu, Y. Pu, J. Zhou, Y. Wang, D. Shen, D2FE-GAN: Decoupled dual feature extraction based GAN for MRI image synthesis, Knowledge-Based Systems, 252 (2022) 109362. [CrossRef]

- X.Z. Zhang, X.Z. He, J. Guo, N. Ettehadi, N. Aw, D. Semanek, J. Posner, A. Laine, Y. Wang, PTNet3D: A 3D High-Resolution Longitudinal Infant Brain MRI Synthesizer Based on Transformers, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41 (2022) 2925-2940. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhu, Q. He, Y. Huang, Z.H. Zhang, J.M. Zeng, L. Lu, W.M. Kong, F.Q. Zhou, DualMMP-GAN: Dual-scale multi-modality perceptual generative adversarial network for medical image segmentation, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 144 (2022). [CrossRef]

- B. Cao, Z.W. Bi, Q.H. Hu, H. Zhang, N.N. Wang, X.B. Gao, D.G. Shen, AutoEncoder-Driven Multimodal Collaborative Learning for Medical Image Synthesis, International Journal of Computer Vision, 131 (2023) 1995-2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Kawahara, H. Yoshimura, T. Matsuura, A. Saito, Y. Nagata, MRI image synthesis for fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted images with deep learning, Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine, (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, S. Pasumarthi, B. Duffy, E. Gong, K. Datta, G. Zaharchuk, One model to synthesize them all: Multi-contrast multi-scale transformer for missing data imputation, IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, (2023). [CrossRef]

- R. Touati, S. Kadoury, A least square generative network based on invariant contrastive feature pair learning for multimodal MR image synthesis, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 18 (2023) 971-979. [CrossRef]

- R. Touati, S. Kadoury, Bidirectional feature matching based on deep pairwise contrastive learning for multiparametric MRI image synthesis, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 68 (2023). [CrossRef]

- B. Wang, Y. Pan, S. Xu, Y. Zhang, Y. Ming, L. Chen, X. Liu, C. Wang, Y. Liu, Y. Xia, Quantitative Cerebral Blood Volume Image Synthesis from Standard MRI Using Image-to-Image Translation for Brain Tumors, Radiology, 308 (2023) e222471. [CrossRef]

- Z.Q. Yu, X.Y. Han, S.J. Zhang, J.F. Feng, T.Y. Peng, X.Y. Zhang, MouseGAN plus plus : Unsupervised Disentanglement and Contrastive Representation for Multiple MRI Modalities Synthesis and Structural Segmentation of Mouse Brain, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 42 (2023) 1197-1209. [CrossRef]

- J. Jiang, Y.-C. Hu, N. Tyagi, P. Zhang, A. Rimner, G.S. Mageras, J.O. Deasy, H. Veeraraghavan, Tumor-aware, adversarial domain adaptation from CT to MRI for lung cancer segmentation, Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2018: 21st International Conference, Granada, Spain, September 16-20, 2018, Proceedings, Part II 11, Springer, 2018, pp. 777-785.

- C.B. Jin, H. Kim, W. Jung, S. Joo, E. Park, Y.S. Ahn, I.H. Han, J.I. Lee, X.N. Cui, CT-based MR Synthesis using Adversarial Cycle-consistent Networks with Paired Data Learning, 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI)Beijing, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2018.

- X. Dong, Y. Lei, S. Tian, T. Wang, P. Patel, W.J. Curran, A.B. Jani, T. Liu, X. Yang, Synthetic MRI-aided multi-organ segmentation on male pelvic CT using cycle consistent deep attention network, Radiotherapy and Oncology, 141 (2019) 192-199. [CrossRef]

- H. Yang, K.J. Xia, A.Q. Bi, P.J. Qian, M.R. Khosravi, Ieee, Abdomen MRI synthesis based on conditional GAN, 6th Annual Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI)Las Vegas, NV, 2019, pp. 1021-1025.

- X. Chen, C.F. Lian, L. Wang, H.N. Deng, S.H. Fung, D. Nie, K.H. Thung, P.T. Yap, J. Gateno, J.J. Xia, D.G. Shen, One-Shot Generative Adversarial Learning for MRI Segmentation of Craniomaxillofacial Bony Structures, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39 (2020) 787-796. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Xu, X.H. Zeng, H. Zhang, W.S. Li, J.B. Lei, Z.W. Huang, BPGAN: Bidirectional CT-to-MRI prediction using multi-generative multi-adversarial nets with spectral normalization and localization, Neural Networks, 128 (2020) 82-96. [CrossRef]

- J.X. Chen, J. Wei, R. Li, TarGAN: Target-Aware Generative Adversarial Networks for Multi-modality Medical Image Translation, International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 24-33.

- Y. Lei, T.H. Wang, S.B. Tian, Y.B. Fu, P. Patel, A.B. Jani, W.J. Curran, T. Liu, X.F. Yang, Male pelvic CT multi-organ segmentation using synthetic MRI-aided dual pyramid networks, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- R. Touati, W.T. Le, S. Kadoury, A feature invariant generative adversarial network for head and neck MRI/CT image synthesis, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H. Kang, A.R. Podgorsak, B.P. Venkatesulu, A.L. Saripalli, B. Chou, A.A. Solanki, M. Harkenrider, S. Shea, J.C. Roeske, M. Abuhamad, Prostate segmentation accuracy using synthetic MRI for high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy treatment planning, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 68 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X. Han, MR-based synthetic CT generation using a deep convolutional neural network method, Medical physics, 44 (2017) 1408-1419. [CrossRef]

- H.F. Sun, Q.Y. Xi, J.W. Sun, R.B. Fan, K. Xie, X.Y. Ni, J.H. Yang, Research on new treatment mode of radiotherapy based on pseudo-medical images, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 221 (2022). [CrossRef]

- C.H. Jiang, X. Zhang, N. Zhang, Q.Y. Zhang, C. Zhou, J.M. Yuan, Q. He, Y.F. Yang, X. Liu, H.R. Zheng, W. Fan, Z.L. Hu, D. Liang, Synthesizing PET/MR (T1-weighted) images from non-attenuation-corrected PET images, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- J.B. Jiao, A.I.L. Namburete, A.T. Papageorghiou, J.A. Noble, Self-Supervised Ultrasound to MRI Fetal Brain Image Synthesis, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39 (2020) 4413-4424. [CrossRef]

- A. Thummerer, B.A. de Jong, P. Zaffino, A. Meijers, G.G. Marmitt, J. Seco, R. Steenbakkers, J.A. Langendijk, S. Both, M.F. Spadea, A.C. Knopf, Comparison of the suitability of CBCT- and MR-based synthetic CTs for daily adaptive proton therapy in head and neck patients, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang, H. Pang, Y. Wu, J. Xu, Z. Liang, S. Xia, C. Jin, R. Chen, S.J.M. Qi, B. Engineering, Computing, InspirationOnly: synthesizing expiratory CT from inspiratory CT to estimate parametric response map, (2025) 1-18. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang, H. Pang, Y. Wu, J. Xu, L. Liu, S. Li, S. Xia, R. Chen, Z. Liang, S.J.C.M. Qi, P.i. Biomedicine, BreathVisionNet: A pulmonary-function-guided CNN-transformer hybrid model for expiratory CT image synthesis, 259 (2025) 108516. [CrossRef]

- P. Yu, H. Zhang, D. Wang, R. Zhang, M. Deng, H. Yang, L. Wu, X. Liu, A.S. Oh, F.G.J.n.D.M. Abtin, Spatial resolution enhancement using deep learning improves chest disease diagnosis based on thick slice CT, 7 (2024) 335. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Yang, J. Sun, A. Carass, C. Zhao, J. Lee, J.L. Prince, Z.B. Xu, Unsupervised MR-to-CT Synthesis Using Structure-Constrained CycleGAN, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 39 (2020) 4249-4261. [CrossRef]

- R. Wei, B. Liu, F.G. Zhou, X.Z. Bai, D.S. Fu, B. Liang, Q.W. Wu, A patient-independent CT intensity matching method using conditional generative adversarial networks (cGAN) for single x-ray projection-based tumor localization, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y.W. Zhang, C.P. Li, Z.H. Dai, L.M. Zhong, X.T. Wang, W. Yang, Breath-Hold CBCT-Guided CBCT-to-CT Synthesis via Multimodal Unsupervised Representation Disentanglement Learning, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 42 (2023) 2313-2324. [CrossRef]

- X. Dong, T.H. Wang, Y. Lei, K. Higgins, T. Liu, W.J. Curran, H. Mao, J.A. Nye, X.F. Yang, Synthetic CT generation from non-attenuation corrected PET images for whole-body PET imaging, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 64 (2019). [CrossRef]

- X.R. Zhou, W.W. Cai, J.J. Cai, F. Xiao, M.K. Qi, J.W. Liu, L.H. Zhou, Y.B. Li, T. Song, Multimodality MRI synchronous construction based deep learning framework for MRI-guided radiotherapy synthetic CT generation, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 162 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Li, J.H. Zhu, Z.B. Liu, J.J. Teng, Q.Y. Xie, L.W. Zhang, X.W. Liu, J.P. Shi, L.X. Chen, A preliminary study of using a deep convolution neural network to generate synthesized CT images based on CBCT for adaptive radiotherapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 64 (2019). [CrossRef]

- X. Liang, L.Y. Chen, D. Nguyen, Z.G. Zhou, X.J. Gu, M. Yang, J. Wang, S. Jiang, Generating synthesized computed tomography (CT) from cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) using CycleGAN for adaptive radiation therapy, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 64 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Y.G. Zhang, Y.R. Pei, H.F. Qin, Y.K. Guo, G.Y. Ma, T.M. Xu, H.B. Zha, Ieee, MASSETER MUSCLE SEGMENTATION FROM CONE-BEAM CT IMAGES USING GENERATIVE ADVERSARIAL NETWORK, 16th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Venice, ITALY, 2019, pp. 1188-1192.

- A. Thummerer, P. Zaffino, A. Meijers, G.G. Marmitt, J. Seco, R. Steenbakkers, J.A. Langendijk, S. Both, M.F. Spadea, A.C. Knopf, Comparison of CBCT based synthetic CT methods suitable for proton dose calculations in adaptive proton therapy, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- L.Y. Chen, X. Liang, C.Y. Shen, D. Nguyen, S. Jiang, J. Wang, Synthetic CT generation from CBCT images via unsupervised deep learning, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L.W. Deng, M.X. Zhang, J. Wang, S.J. Huang, X. Yang, Improving cone-beam CT quality using a cycle-residual connection with a dilated convolution-consistent generative adversarial network, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 67 (2022). [CrossRef]

- L.W. Deng, Y.F. Ji, S.J. Huang, X. Yang, J. Wang, Synthetic CT generation from CBCT using double-chain-CycleGAN, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 161 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Joseph, I. Biji, N. Babu, P.N. Pournami, P.B. Jayaraj, N. Puzhakkal, C. Sabu, V. Patel, Fan beam CT image synthesis from cone beam CT image using nested residual UNet based conditional generative adversarial network, Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine, 46 (2023) 703-717. [CrossRef]

- A. Szmul, S. Taylor, P. Lim, J. Cantwell, I. Moreira, Y. Zhang, D. D’Souza, S. Moinuddin, M.N. Gaze, J. Gains, C. Veiga, Deep learning based synthetic CT from cone beam CT generation for abdominal paediatric radiotherapy, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 68 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Z.L. Hu, Y.C. Li, S.J. Zou, H.Z. Xue, Z.R. Sang, X. Liu, Y.F. Yang, X.H. Zhu, D. Liang, H.R. Zheng, Obtaining PET/CT images from non-attenuation corrected PET images in a single PET system using Wasserstein generative adversarial networks, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- F. Rao, B. Yang, Y.W. Chen, J.S. Li, H.K. Wang, H.W. Ye, Y.F. Wang, K. Zhao, W.T. Zhu, A novel supervised learning method to generate CT images for attenuation correction in delayed pet scans, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 197 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J.T. Li, Y.W. Wang, Y. Yang, X. Zhang, Z.J. Qu, S.B. Hu, Small animal PET to CT image synthesis based on conditional generation network, 14th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI)Shanghai, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2021.

- X.D. Ying, H. Guo, K. Ma, J. Wu, Z.X. Weng, Y.F. Zheng, I.C. Soc, X2CT-GAN: Reconstructing CT from Biplanar X-Rays with Generative Adversarial Networks, 32nd IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)Long Beach, CA, 2019, pp. 10611-10620.

- A. Lewis, E. Mahmoodi, Y.Y. Zhou, M. Coffee, E. Sizikova, I.C. Soc, Improving Tuberculosis (TB) Prediction using Synthetically Generated Computed Tomography (CT) Images, IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCVW)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 3258-3266.

- G. Li, L. Bai, C.W. Zhu, E.H. Wu, R.B. Ma, A Novel Method of Synthetic CT Generation from MR Images based on Convolutional Neural Networks, 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI)Beijing, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2018.

- M. Maspero, M.H.F. Savenije, A.M. Dinkla, P.R. Seevinck, M.P.W. Intven, I.M. Jurgenliemk-Schulz, L.G.W. Kerkmeijer, C.A.T. van den Berg, Dose evaluation of fast synthetic-CT generation using a generative adversarial network for general pelvis MR-only radiotherapy, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 63 (2018). [CrossRef]

- D. Nie, R. Trullo, J. Lian, L. Wang, C. Petitjean, S. Ruan, Q. Wang, D. Shen, Medical Image Synthesis with Deep Convolutional Adversarial Networks, Ieee Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 65 (2018) 2720-2730. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiang, Q. Wang, D. Nie, L.C. Zhang, X.Y. Jin, Y. Qiao, D.G. Shen, Deep embedding convolutional neural network for synthesizing CT image from T1-Weighted MR image, Medical Image Analysis, 47 (2018) 31-44. [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Ge, D.M. Wei, Z. Xue, Q. Wang, X. Zhou, Y.Q. Zhan, S. Liao, Ieee, UNPAIRED MR TO CT SYNTHESIS WITH EXPLICIT STRUCTURAL CONSTRAINED ADVERSARIAL LEARNING, 16th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Venice, ITALY, 2019, pp. 1096-1099.

- A. Largent, J.C. Nunes, H. Saint-Jalmes, J. Baxter, P. Greer, J. Dowling, R. de Crevoisier, O. Acosta, Ieee, PSEUDO-CT GENERATION FOR MRI-ONLY RADIOTHERAPY: COMPARATIVE STUDY BETWEEN A GENERATIVE ADVERSARIAL NETWORK, A U-NET NETWORK, A PATCH-BASED, AND AN ATLAS BASED METHODS, 16th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Venice, ITALY, 2019, pp. 1109-1113.

- Y.Z. Liu, Y. Lei, Y.N. Wang, G. Shafai-Erfani, T.H. Wang, S.B. Tian, P. Patel, A.B. Jani, M. McDonald, W.J. Curran, T. Liu, J. Zhou, X.F. Yang, Evaluation of a deep learning-based pelvic synthetic CT generation technique for MRI-based prostate proton treatment planning, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 64 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Y.Z. Liu, Y. Lei, Y.N. Wang, T.H. Wang, L. Ren, L.Y. Lin, M. McDonald, W.J. Curran, T. Liu, J. Zhou, X.F. Yang, MRI-based treatment planning for proton radiotherapy: dosimetric validation of a deep learning-based liver synthetic CT generation method, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 64 (2019). [CrossRef]

- G. Zeng, G. Zheng, Hybrid generative adversarial networks for deep MR to CT synthesis using unpaired data, Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2019: 22nd International Conference, Shenzhen, China, October 13–17, 2019, Proceedings, Part IV 22, Springer, 2019, pp. 759-767.

- H. Arabi, G. Zeng, G. Zheng, H. Zaidi, Novel adversarial semantic structure deep learning for MRI-guided attenuation correction in brain PET/MRI, European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging, 46 (2019) 2746-2759.

- K. Boni, J. Klein, L. Vanquin, A. Wagner, T. Lacornerie, D. Pasquier, N. Reynaert, MR to CT synthesis with multicenter data in the pelvic area using a conditional generative adversarial network, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020).

- H. Emami, M. Dong, C.K. Glide-Hurst, I.C. Soc, Attention-Guided Generative Adversarial Network to Address Atypical Anatomy in Synthetic CT Generation, 21st IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IEEE IRI)Electr Network, 2020, pp. 188-193.

- L. Fetty, T. Lofstedf, G. Heilemann, H. Furtado, N. Nesvacil, T. Nyholm, D. Georg, P. Kuess, Investigating conditional GAN performance with different generator architectures, an ensemble model, and different MR scanners for MR-sCT conversion, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- L.L. Liu, A. Johansson, Y. Cao, J. Dow, T.S. Lawrence, J.M. Balter, Abdominal synthetic CT generation from MR Dixon images using a U-net trained with ‘semi-synthetic’ CT data, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- H.A. Massa, J.M. Johnson, A.B. McMillan, Comparison of deep learning synthesis of synthetic CTs using clinical MRI inputs, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 65 (2020). [CrossRef]

- R. Oulbacha, S. Kadoury, Ieee, MRI TO CT SYNTHESIS OF THE LUMBAR SPINE FROM A PSEUDO-3D CYCLE GAN, IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Iowa, IA, 2020, pp. 1784-1787.

- A. Abu-Srhan, I. Almallahi, M.A.M. Abushariah, W. Mahafza, O.S. Al-Kadi, Paired-unpaired Unsupervised Attention Guided GAN with transfer learning for bidirectional brain MR-CT synthesis, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 136 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Bajger, M.S. To, G. Lee, A. Wells, C. Chong, M. Agzarian, S. Poonnoose, Ieee, Lumbar Spine CT synthesis from MR images using CycleGAN - a preliminary study, International Conference on Digital Image Computing - Techniques and Applications (DICTA)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 420-427.

- H. Chourak, A. Barateau, E. Mylona, C. Cadin, C. Lafond, P. Greer, J. Dowling, R. de Crevoisier, O. Acosta, Ieee, Voxel-Wise Analysis for Spatial Characterisation of Pseudo-CT Errors in MRI-Only Radiotherapy Planning, 18th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Nice, FRANCE, 2021, pp. 395-399.

- H. Emami, M. Dong, S.P. Nejad-Davarani, C.K. Glide-Hurst, SA-GAN: Structure-Aware GAN for Organ-Preserving Synthetic CT Generation, International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 471-481.

- S.K. Kang, H.J. An, H. Jin, J.I. Kim, E.K. Chie, J.M. Park, J.S. Lee, Synthetic CT generation from weakly paired MR images using cycle-consistent GAN for MR-guided radiotherapy, Biomedical Engineering Letters, 11 (2021) 263-271. [CrossRef]

- R.R. Liu, Y. Lei, T.H. Wang, J. Zhou, J. Roper, L.Y. Lin, M.W. McDonald, J.D. Bradley, W.J. Curran, T. Liu, X.F. Yang, Synthetic dual-energy CT for MRI-only based proton therapy treatment planning using label-GAN, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Y.X. Liu, A.N. Chen, H.Y. Shi, S.J. Huang, W.J. Zheng, Z.Q. Liu, Q. Zhang, X. Yang, CT synthesis from MRI using multi-cycle GAN for head-and-neck radiation therapy, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 91 (2021). [CrossRef]

- S. Olberg, J. Chun, B.S. Choi, I. Park, H. Kim, T. Kim, J.S. Kim, O. Green, J.C. Park, Abdominal synthetic CT reconstruction with intensity projection prior for MRI-only adaptive radiotherapy, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 66 (2021). [CrossRef]

- R.Z. Wang, G.Y. Zheng, Ieee, DISENTANGLED REPRESENTATION LEARNING FOR DEEP MR TO CT SYNTHESIS USING UNPAIRED DATA, IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 274-278.

- S. Zenglin, P. Mettes, G. Zheng, C. Snoek, Frequency-Supervised MR-to-CT Image Synthesis, 1st Workshop on Deep Generative Models for Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (DGM4MICCAI) / 1st MICCAI Workshop on Data Augmentation, Labelling, and Imperfections (DALI)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 3-13.

- S.P. Ang, S.L. Phung, M. Field, M.M. Schira, Ieee, AN IMPROVED DEEP LEARNING FRAMEWORK FOR MR-TO-CT IMAGE SYNTHESIS WITH A NEW HYBRID OBJECTIVE FUNCTION, 19th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (IEEE ISBI)Kolkata, INDIA, 2022.

- G. Dovletov, D.D. Pham, S. Lörcks, J. Pauli, M. Gratz, H.H. Quick, Grad-CAM guided U-net for MRI-based pseudo-CT synthesis, 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), IEEE, 2022, pp. 2071-2075.

- G. Dovletov, D.D. Pham, J. Pauli, M. Gratz, H. Quick, Improved MRI-based Pseudo-CT Synthesis via Segmentation Guided Attention Networks, 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC) / 9th International Conference on Bioimaging (BIOIMAGING)Electr Network, 2022, pp. 131-140.

- P. Eshraghi Boroojeni, Y. Chen, P.K. Commean, C. Eldeniz, G.B. Skolnick, C. Merrill, K.B. Patel, H. An, Deep-learning synthesized pseudo-CT for MR high-resolution pediatric cranial bone imaging (MR-HiPCB), Magnetic resonance in medicine, 88 (2022) 2285-2297.

- A.G. Hernandez, P. Fau, S. Rapacchi, J. Wojak, H. Mailleux, M. Benkreira, M. Adel, Generation of synthetic CT with Deep Learning for Magnetic Resonance Guided Radiotherapy, 16th International Conference on Signal-Image Technology and Internet-Based Systems (SITIS)Dijon, FRANCE, 2022, pp. 368-371.

- A. Jabbarpour, S.R. Mahdavi, A.V. Sadr, G. Esmaili, I. Shiri, H. Zaidi, Unsupervised pseudo CT generation using heterogenous multicentric CT/MR images and CycleGAN: Dosimetric assessment for 3D conformal radiotherapy, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 143 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, M.K. Sigona, T.J. Manuel, L.M. Chen, C.F. Caskey, B.M. Dawant, Synthetic CT Skull Generation for Transcranial MR Imaging-Guided Focused Ultrasound Interventions with Conditional Adversarial Networks, Conference on Medical Imaging - Image-Guided Procedures, Robotic Interventions, and ModelingElectr Network, 2022.

- Q. Lyu, G. Wang, Conversion between ct and mri images using diffusion and score-matching models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.12104, (2022).

- S.H. Park, D.M. Choi, I.H. Jung, K.W. Chang, M.J. Kim, H.H. Jung, J.W. Chang, H. Kim, W.S. Chang, Clinical application of deep learning-based synthetic CT from real MRI to improve dose planning accuracy in Gamma Knife radiosurgery: a proof of concept study, Biomedical Engineering Letters, 12 (2022) 359-367.

- Ranjan, D. Lalwani, R. Misra, GAN for synthesizing CT from T2-weighted MRI data towards MR-guided radiation treatment, Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine, 35 (2022) 449-457.

- H.F. Sun, Q.Y. Xi, R.B. Fan, J.W. Sun, K. Xie, X.Y. Ni, J.H. Yang, Synthesis of pseudo-CT images from pelvic MRI images based on an MD-CycleGAN model for radiotherapy, Physics in Medicine and Biology, 67 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S.I.Z. Estakhraji, A. Pirasteh, T. Bradshaw, A. McMillan, On the effect of training database size for MR-based synthetic CT generation in the head, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 107 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, S.S. Xu, H.B. Chen, Y. Sun, J. Bian, S.S. Guo, Y. Lu, Z.Y. Qi, CT synthesis from multi-sequence MRI using adaptive fusion network, Computers in Biology and Medicine, 157 (2023). [CrossRef]

- X.M. Liu, J.L. Pan, X. Li, X.K. Wei, Z.P. Liu, Z.F. Pan, J.S. Tang, Attention Based Cross-Domain Synthesis and Segmentation From Unpaired Medical Images, Ieee Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence, (2023). [CrossRef]

- G. Parrella, A. Vai, A. Nakas, N. Garau, G. Meschini, F. Camagni, S. Molinelli, A. Barcellini, A. Pella, M. Ciocca, V. Vitolo, E. Orlandi, C. Paganelli, G. Baroni, Synthetic CT in Carbon Ion Radiotherapy of the Abdominal Site, Bioengineering-Basel, 10 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J.Y. Wang, Q.M.J. Wu, F. Pourpanah, An attentive-based generative model for medical image synthesis, International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics, (2023). [CrossRef]

- L.F. Wang, Y. Liu, J. Mi, J. Zhang, MSE-Fusion: Weakly supervised medical image fusion with modal synthesis and enhancement, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 119 (2023). [CrossRef]

- B. Zhao, T.T. Cheng, X.R. Zhang, J.J. Wang, H. Zhu, R.C. Zhao, D.W. Li, Z.J. Zhang, G. Yu, CT synthesis from MR in the pelvic area using Residual Transformer Conditional GAN, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics, 103 (2023). [CrossRef]

- T. Nyholm, S. Svensson, S. Andersson, J. Jonsson, M. Sohlin, C. Gustafsson, E. Kjellén, K. Söderström, P. Albertsson, L. Blomqvist, MR and CT data with multiobserver delineations of organs in the pelvic area—Part of the Gold Atlas project, Medical physics, 45 (2018) 1295-1300. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Zhong, Z.L. Chen, H. Shu, Y.K. Zheng, Y.W. Zhang, Y.K. Wu, Q.J. Feng, Y. Li, W. Yang, QACL: Quartet attention aware closed-loop learning for abdominal MR-to-CT synthesis via simultaneous registration, Medical Image Analysis, 83 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, S. Miao, T. Mansi, R. Liao, Unsupervised X-ray image segmentation with task driven generative adversarial networks, Medical Image Analysis, 62 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y.X. Huang, F.X. Fan, C. Syben, P. Roser, L. Mill, A. Maier, Cephalogram synthesis and landmark detection in dental cone-beam CT systems, Medical Image Analysis, 70 (2021). [CrossRef]

- C. Peng, H.F. Liao, N. Wong, J.B. Luo, S.K. Zhou, R. Chellappa, I. Assoc Advancement Artificial, XraySyn: Realistic View Synthesis From a Single Radiograph Through CT Priors, 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence / 33rd Conference on Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence / 11th Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial IntelligenceElectr Network, 2021, pp. 436-444.

- P.H.H. Yuen, X.H. Wang, Z.P. Lin, N.K.W. Chow, J. Cheng, C.H. Tan, W.M. Huang, CT2CXR: CT-based CXR Synthesis for Covid-19 Pneumonia Classification, 13th International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging (MLMI)Singapore, SINGAPORE, 2022, pp. 210-219.

- L.Y. Shen, L.Q. Yu, W. Zhao, J. Pauly, L. Xing, Novel-view X-ray projection synthesis through geometry-integrated deep learning, Medical Image Analysis, 77 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Yan, H. Lee, E. Somer, V. Grau, Generation of Amyloid PET Images via Conditional Adversarial Training for Predicting Progression to Alzheimer’s Disease, 1st International Workshop on PRedictive Intelligence in MEdicine (PRIME)Granada, SPAIN, 2018, pp. 26-33.

- H. Emami, M. Dong, C. Glide-Hurst, CL-GAN: Contrastive Learning-Based Generative Adversarial Network for Modality Transfer with Limited Paired Data, European Conference on Computer Vision, Springer, 2022, pp. 527-542.

- S.Y. Hu, B.Y. Lei, S.Q. Wang, Y. Wang, Z.G. Feng, Y.Y. Shen, Bidirectional Mapping Generative Adversarial Networks for Brain MR to PET Synthesis, Ieee Transactions on Medical Imaging, 41 (2022) 145-157. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, X.H. He, L.B. Qing, F. Gao, B. Wang, BPGAN: Brain PET synthesis from MRI using generative adversarial network for multi-modal Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 217 (2022). [CrossRef]

- A. Ben-Cohen, E. Klang, S.P. Raskin, S. Soffer, S. Ben-Haim, E. Konen, M.M. Amitai, H. Greenspan, Cross-modality synthesis from CT to PET using FCN and GAN networks for improved automated lesion detection, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 78 (2019) 186-194. [CrossRef]

- S. Olut, Y.H. Sahin, U. Demir, G. Unal, Generative Adversarial Training for MRA Image Synthesis Using Multi-contrast MRI, 1st International Workshop on PRedictive Intelligence in MEdicine (PRIME)Granada, SPAIN, 2018, pp. 147-154.

- V.M. Campello, C. Martin-Isla, C. Izquierdo, S.E. Petersen, M.A.G. Ballester, K. Lekadir, Combining Multi-Sequence and Synthetic Images for Improved Segmentation of Late Gadolinium Enhancement Cardiac MRI, 10th International Workshop on Statistical Atlases and Computational Modelling of the Heart (STACOM)Shenzhen, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2019, pp. 290-299.

- J.F. Zhao, D.W. Li, Z. Kassam, J. Howey, J. Chong, B. Chen, S. Li, Tripartite-GAN: Synthesizing liver contrast-enhanced MRI to improve tumor detection, Medical Image Analysis, 63 (2020). [CrossRef]

- A. Bone, S. Ammari, J.P. Lamarque, M. Elhaik, E. Chouzenoux, F. Nicolas, P. Robert, C. Balleyguier, N. Lassau, M.M. Rohe, Ieee, CONTRAST-ENHANCED BRAIN MRI SYNTHESIS WITH DEEP LEARNING: KEY INPUT MODALITIES AND ASYMPTOTIC PERFORMANCE, 18th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI)Nice, FRANCE, 2021, pp. 1159-1163.

- M.Q. Pan, H. Zhang, Z.C. Tang, Y.H. Zhao, J. Tian, Ieee, Attention-Based Multi-Scale Generative Adversarial Network for synthesizing contrast-enhanced MRI, 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE-Engineering-in-Medicine-and-Biology-Society (IEEE EMBC)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 3650-3653.

- C.C. Xu, D. Zhang, J. Chong, B. Chen, S. Li, Synthesis of gadolinium-enhanced liver tumors on nonenhanced liver MR images using pixel-level graph reinforcement learning, Medical Image Analysis, 69 (2021). [CrossRef]

- H.W. Chen, S.A. Yan, M.X. Xie, J.L. Huang, Application of cascaded GAN based on CT scan in the diagnosis of aortic dissection, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 226 (2022). [CrossRef]

- T. Hu, M. Oda, Y. Hayashi, Z.Y. Lu, K.K. Kumamaru, T. Akashi, S. Aoki, K. Mori, Aorta-aware GAN for non-contrast to artery contrasted CT translation and its application to abdominal aortic aneurysm detection, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 17 (2022) 97-105. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xue, B.E. Dewey, L.R. Zuo, S. Han, A. Carass, P.Y. Duan, S.W. Remedios, D.L. Pham, S. Saidha, P.A. Calabresi, J.L. Prince, Bi-directional Synthesis of Pre- and Post-contrast MRI via Guided Feature Disentanglement, 7th International Workshop on Simulation and Synthesis in Medical Imaging (SASHIMI)Singapore, SINGAPORE, 2022, pp. 55-65.

- C. Chen, C. Raymond, W. Speier, X.Y. Jin, T.F. Cloughesy, D. Enzmann, B.M. Ellingson, C.W. Arnold, Synthesizing MR Image Contrast Enhancement Using 3D High-Resolution ConvNets, Ieee Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 70 (2023) 401-412. [CrossRef]

- R.A. Khan, Y.G. Luo, F.X. Wu, Multi-level GAN based enhanced CT scans for liver cancer diagnosis, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 81 (2023). [CrossRef]

- A. Killekar, J. Kwiecinski, M. Kruk, C. Kepka, A. Shanbhag, D. Dey, P. Slomka, Pseudo-contrast cardiac CT angiography derived from non-contrast CT using conditional generative adversarial networks, Conference on Medical Imaging - Image ProcessingSan Diego, CA, 2023.

- E. Kim, H.H. Cho, J. Kwon, Y.T. Oh, E.S. Ko, H. Park, Tumor-Attentive Segmentation-Guided GAN for Synthesizing Breast Contrast-Enhanced MRI Without Contrast Agents, Ieee Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine, 11 (2023) 32-43. [CrossRef]

- N.-C. Ristea, A.-I. Miron, O. Savencu, M.-I. Georgescu, N. Verga, F.S. Khan, R.T. Ionescu, CyTran: A Cycle-Consistent Transformer with Multi-Level Consistency for Non-Contrast to Contrast CT Translation, Neurocomputing, (2023). [CrossRef]

- S.H. Welland, G. Melendez-Corres, P.Y. Teng, H. Coy, A. Li, M.W. Wahi-Anwar, S. Raman, M.S. Brown, Using a GAN for CT contrast enhancement to improve CNN kidney segmentation accuracy, Conference on Medical Imaging - Image ProcessingSan Diego, CA, 2023.

- H.X. Zhang, M.H. Zhang, Y. Gu, G.Z. Yang, Deep anatomy learning for lung airway and artery-vein modeling with contrast-enhanced CT synthesis, International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 18 (2023) 1287-1294.

- L.M. Zhong, P.Y. Huang, H. Shu, Y. Li, Y.W. Zhang, Q.J. Feng, Y.K. Wu, W. Yang, United multi-task learning for abdominal contrast-enhanced CT synthesis through joint deformable registration, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 231 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M.E.J.A.r.o.n. Raichle, Positron emission tomography, 6 (1983) 249-267.

- J.E.J.C.c.m. Aldrich, Basic physics of ultrasound imaging, 35 (2007) S131-S137.

- Grimwood, J. Ramalhinho, Z.M.C. Baum, N. Montana-Brown, G.J. Johnson, Y.P. Hu, M.J. Clarkson, S.P. Pereira, D.C. Barratt, E. Bonmati, Endoscopic Ultrasound Image Synthesis Using a Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Network, 2nd International Workshop on Advances in Simplifying Medical UltraSound (ASMUS)Electr Network, 2021, pp. 169-178.

- R.J. Kim, E. Wu, A. Rafael, E.-L. Chen, M.A. Parker, O. Simonetti, F.J. Klocke, R.O. Bonow, R.M.J.N.E.J.o.M. Judd, The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction, 343 (2000) 1445-1453.

- R.R.J.R. Edelman, Contrast-enhanced MR imaging of the heart: overview of the literature, 232 (2004) 653-668. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Mallio, A. Radbruch, K. Deike-Hofmann, A.J. van der Molen, I.A. Dekkers, G. Zaharchuk, P.M. Parizel, B.B. Zobel, C.C.J.I.r. Quattrocchi, Artificial intelligence to reduce or eliminate the need for gadolinium-based contrast agents in brain and cardiac MRI: a literature review, 58 (2023) 746-753.

- H. Alqahtani, M. Kavakli-Thorne, G. Kumar, Applications of generative adversarial networks (gans): An updated review, Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 28 (2021) 525-552. [CrossRef]

- J. Ho, A. Jain, P. Abbeel, Denoising diffusion probabilistic models, Advances in neural information processing systems, 33 (2020) 6840-6851.

- F.-A. Croitoru, V. Hondru, R.T. Ionescu, M.J.I.T.o.P.A. Shah, M. Intelligence, Diffusion models in vision: A survey, (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. Song, C. Meng, S. Ermon, Denoising diffusion implicit models, arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02502, (2020).

- Yang, Z. Zhang, Y. Song, S. Hong, R. Xu, Y. Zhao, W. Zhang, B. Cui, M.-H.J.A.C.S. Yang, Diffusion models: A comprehensive survey of methods and applications, 56 (2023) 1-39. [CrossRef]

- B. Cao, H. Zhang, N. Wang, X. Gao, D. Shen, Auto-GAN: self-supervised collaborative learning for medical image synthesis, Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2020, pp. 10486-10493. [CrossRef]

- L. Sun, J. Wang, Y. Huang, X. Ding, H. Greenspan, J.J.I.j.o.b. Paisley, h. informatics, An adversarial learning approach to medical image synthesis for lesion detection, 24 (2020) 2303-2314. [CrossRef]

- M. Azadmanesh, B.S. Ghahfarokhi, M.A. Talouki, H.J.E.S.w.A. Eliasi, On the local convergence of GANs with differential Privacy: Gradient clipping and noise perturbation, 224 (2023) 120006. [CrossRef]

- G. Hinton, O. Vinyals, J.J.a.p.a. Dean, Distilling the knowledge in a neural network, (2015).

- T. Miyato, T. Kataoka, M. Koyama, Y.J.a.p.a. Yoshida, Spectral normalization for generative adversarial networks, (2018).

- C. Kim, S. Park, H.J.J.I.T.o.N.N. Hwang, L. Systems, Local stability of wasserstein GANs with abstract gradient penalty, 33 (2021) 4527-4537.

- J. Yim, D. Joo, J. Bae, J. Kim, A gift from knowledge distillation: Fast optimization, network minimization and transfer learning, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 4133-4141.

- X. Wang, K. Yu, S. Wu, J. Gu, Y. Liu, C. Dong, Y. Qiao, C. Change Loy, Esrgan: Enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial networks, Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) workshops, 2018, pp. 0-0.

- T. Salimans, I. Goodfellow, W. Zaremba, V. Cheung, A. Radford, X.J.A.i.n.i.p.s. Chen, Improved techniques for training gans, 29 (2016).

- T.-C. Wang, M.-Y. Liu, J.-Y. Zhu, A. Tao, J. Kautz, B. Catanzaro, High-resolution image synthesis and semantic manipulation with conditional gans, Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 8798-8807.

| Symbol | Name | Formula |

| IS | Inception Score | |

| MS | Mode Score | |

| MMD | Kernel Maximum Mean Discrepancy | |

| WD | Wasserstein distance | |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance |

| Paper | Model | Anatomy | Modality | Dimension |

| [65] | DCGAN, ACGAN | Liver | CT | 2D |

| [66] | DCGAN, WGAN, BEGAN | Thyroid | OCT | 2D |

| [67] | ACGAN | Limb | X-ray | 2D |

| [30] | ICVAE | Spine, brain | Ultrasound, MRI | 2D |

| [54] | DCGAN | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [68] | - | Lung | CT | 3D |

| [69] | PGGAN | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [70] | MTT-GAN | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [71] | CT-SGAN | Chest | CT | 3D |

| [72] | COViT-GAN | Chest | CT | 2D |

| [73] | Two stage GAN | Liver | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [74] | TripleGAN | Breast | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [75] | InfoGAN | Lung | CT | 2D |

| [76] | GAN | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [77] | LSN | Brain | CT | 2D |

| [78] | StyleGAN2 | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [79] | DCGAN, cGAN | Prostate | MRI | 2D |

| [80] | TMP-GAN | Breast, pancreatic | X-ray, CT | 2D |

| [81] | CycleGAN | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [82] | PLGAN | Ophthalmology, Brain, Lung | OCT, MRI, CT, X-ray | 2D |

| [83] | CUT | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [84] | HBGM | Coronary | X-ray | 2D |

| [85] | DC-GAN | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [86] | MI-GAN | Chest | CT | 2D |

| [87] | StyleGAN2 | Chest | X-ray | 2D |

| [55] | DDPM | Chest, heart, pelvis, abdomen | MRI, CT, X-ray | 2D |

| [88] | StynMedGAN | Chest, brain | MRI, CT, X-ray | 2D |

| Paper | Model | Anatomy | Modality | Dimension |

| [89] | Two stage GAN | Intravascular | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [90] | SpeckleGAN | Intravascular | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [91] | CycleGAN | Gastrocnemius medialis muscle | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [92] | Private | - | - | 2D |

| [93] | Pix2Pix | bone surface | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [31] | VAE | - | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [94] | Pix2Pix | Prostate | MRI | 2D |

| [59] | CG-SAMR | Brain | MRI | 3D |

| [95] | GAN, VAE | Thyroid | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [96] | WFT-GAN | - | - | 2D |

| [60] | Dense GAN | Lung | CT | 2D |

| [61] | VAE, GAN | Cardiac | MRI | 3D |

| [97] | LEGAN | Retinal | Digital Retinal Images | 2D |

| [98] | spGAN | Lung, hip joint, ovary | Ultrasound | 2D |

| [99] | cGAN | cardiac | MRI | 2D |

| [100] | SR-TTT | Liver | CT | 2D |

| [101] | Pix2Pix, CycleGAN, SPADE | Brain | MRI | 2D |

| [102] | SPADE | Rectal | MRI | 3D |

| [103] | 3D GAN | Lung | CT | 3D |

| [104] | - | Lung | X-ray | 2D |

| [105] | - | Brain | MRI | 3D |

| [106] | DCGAN | Retinal, coronary, knee | X-ray, MRI | 2D |

| [107] | Pix2Pix | Lung | CT | 2D |

| [108] | - | Cheat | X-ray | 2D |

| [109] | Pix2Pix | Lung | CT | 2D |

| [110] | MinimalGAN | Retinal fundus | Nature | 2D |

| Paper | Model | Anatomy | Modality | Dimension | Task |

| [111] | DCGAN, WGAN | Brain | MRI | 2D | None |

| [62] | MCGAN | Lung nodules | CT | 3D | Object detection |

| [63] | SMIG | Brain glioblastoma | MRI | 3D | Tumors growth prediction |

| [112] | InfoGAN | Fetal head | Ultrasound | 2D | None |

| [113] | Private | Prostate | MRI | 2D | Prostate cancer Localization |

| [114] | DCGAN-PSO | Lung | X-ray | 2D | None |

| [115] | U-Net | Lung nodules | X-ray | 2D | Object detection |

| [116] | 3D-StyleGAN | Brain | MRI | 3D | None |

| [117] | CGAN, DCGAN, f-GAN, WGAN, CycleGAN | Lung | X-ray, CT | 2D | None |

| [118] | DCGAN | Brian | MRI | 2D | None |

| [64] | DeepAnat | Brian | MRI | 3D | Neuroscientific applications |

| Symbol | Name | Formula |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error | |

| MSE | Mean Square Error | |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error | |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio | |

| SSIM | Structural similarity index |

| Paper | Dataset | Dimension | Modality translation | Model | |

| Name | Paired image | ||||

| [127] | BraTS 2015 | 3D | T1→FLAIR | 3D cGAN | Yes |

| [38] | MIDAS, IXI, BraTS | 2D | T1↔T2 | pGAN, cGAN | Yes, No |

| [128] | BraTS 2015, IXI | 3D | T1→FLAIR; T1→T2 | Ea-GANs | Yes |

| [129] | BraTS 2018 | 2D | T1, T2, T1ce, FLAIR (Three-to-One) | Auto-GAN | Yes |

| [122] | ISLES 2015, BraTS 2018 | 2D | T1, T2, DWI; T1, T1ce, T2, FLAIR (generating the missing contrast(s)) |

MM-GAN | Yes |

| [130] | BraTS 2018 | 2D | T1↔T2 | - | Yes |

| [131] | Private | 2D | T1↔T2 | CACGAN | No |

| [132] | BraTS 2018 | 2D | T2→(FLAIR, T1, T1ce) | TC-MGAN | Yes |

| [133] | BraTS 2015, SISS 2015 | 3D | T1→FLAIR; T1→T2 | SA-GAN | Yes |

| [123] | BraTS 2018 | 2D | T1↔T2; T1↔FLAIR; T2↔FLAIR; T1, T2, FLAIR (Two-to-One) |

Hi-Net | Yes |

| [134] | BraTS 2017, TCGA | 2D | (T1ce, FLAIR)→T2 | - | Yes |

| [135] | BraTS 2018 | 2D | T1, T2, T1ce, FLAIR (generating the missing contrast(s)) |

- | Yes |

| [136] | BraTS 2015 | 2D | T1→FLAIR; T1→T2 | EP-IMF-GAN | Yes |

| [137] | HCP 500 | 2D | B0→DWI; B0, T2→DWI; B0, T1, T2→DWI | - | Yes |

| [138] | Private, IXI | 2.5D | T1→T2 | - | Yes |

| [139] | IXI | 2D | T2↔PD | DiCyc | No |

| [140] | BraTS 2015 | 2D | T1↔T2 | - | No |

| [141] | IXI, BraTS 2019 | 2D | Unified model | Hyper-GAN | Yes |

| [142] | IXI, ISLES | 2D | T1↔T2; T1↔PD; T2↔PD; T1↔FLAIR; T2↔FLAIR; T1, T2, PD (Two-to-One); T1, T2, FLAIR (Two-to-One) |

mustGAN | Yes |

| [143] | BraTS 2015 | 2D | T1, T1ce→FLAIR; T1, T2→FLAIR; T1, T1ce→T2 | LR-cGAN | Yes |

| [144] | BraTS 2018 | 3D | T1, T2, T1ce, FLAIR (generating the missing contrast(s)) |

- | Yes |

| [145] | ADNI | 2D | T1→CBV | DeepContrast | Yes |

| [146] | Private | 2D | PD↔T2 | - | No |

| [147] | IXI, BraTS | 2D | T1, T2, PD (Two-to-One); T1, T2, FLAIR (Two-to-One) PD↔T2; FLAIR↔T2 |

ResViT | Yes |

| [97] | IXI | 2D | T2→PD | TR-GAN | Yes |

| [148] | BraTS2019 | 3D | T1, T2, T1ce, FLAIR (generating the missing contrast(s)) |

CoCa-GAN | Yes |

| [149] | - | 2D | T2↔DWI | CICVAE | No |

| [150] | BraTS2019 | 2D | T1→T2 | NEDNet | Yes |