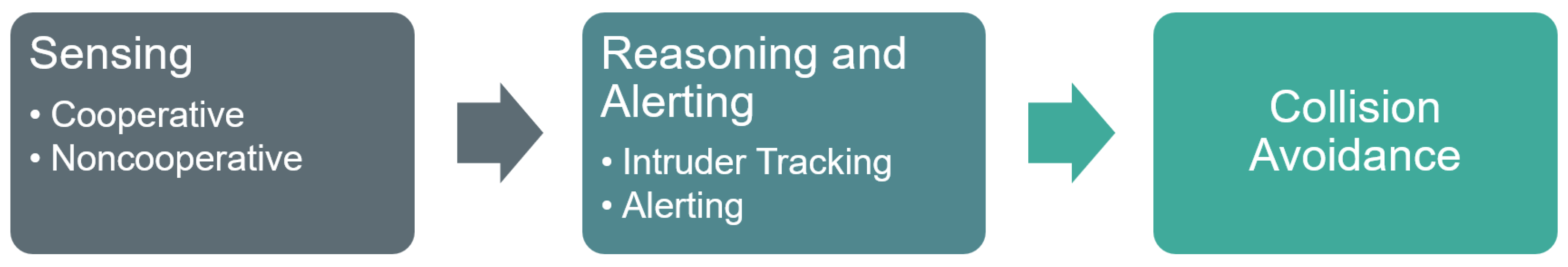

Within the following subsections, various sensors and techniques are analyzed and evaluated with respect to their applicability of detecting cooperative and noncooperative intruders. The discussion begins with a description of the sensor types considered in this work, followed by a presentation of classical and ML methods for object detection.

3.1.1. Sensor Types

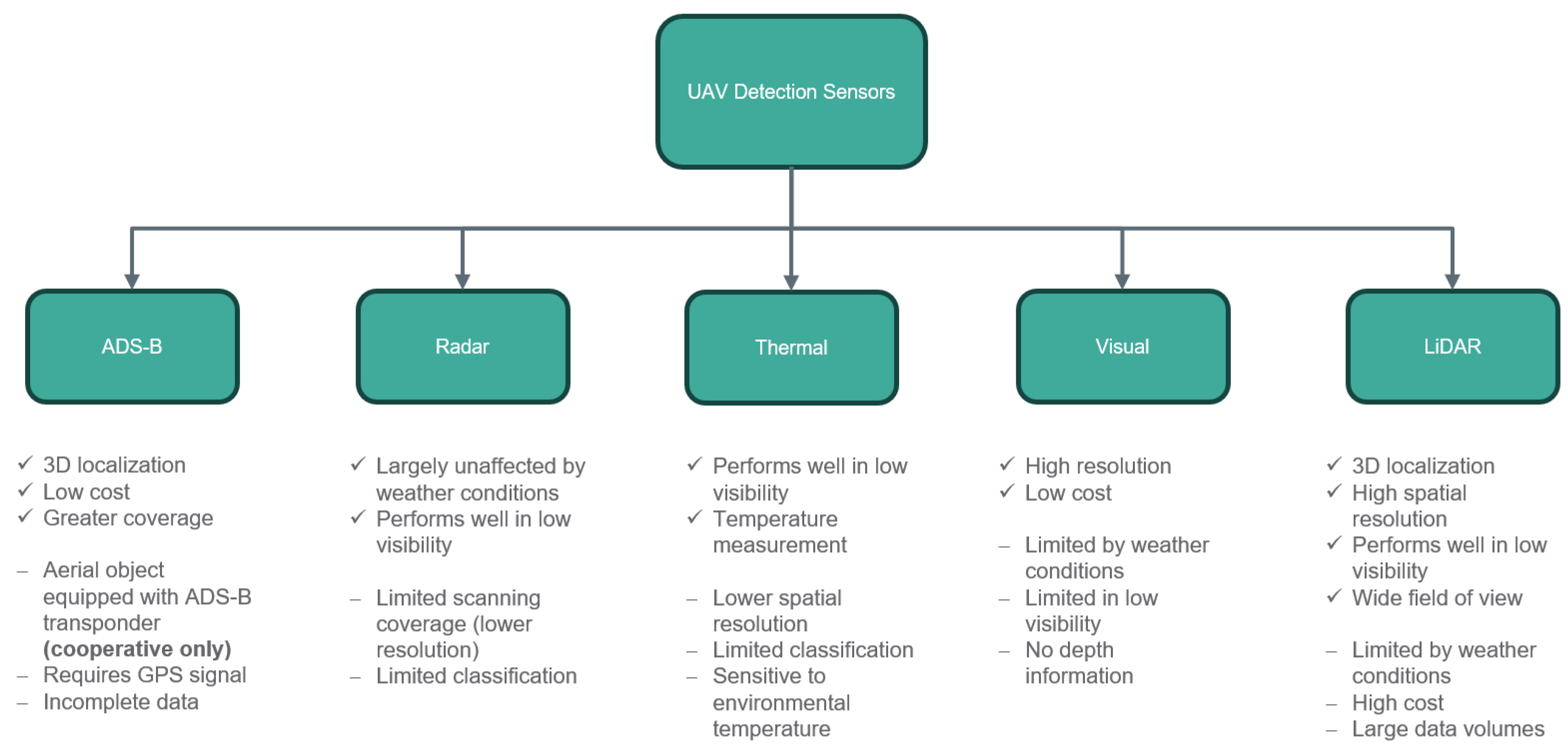

The suitability of specific sensors varies according to whether the detection task involves a cooperative or noncooperative intruder. In comparison with noncooperative intruders, cooperative intruders are aerial objects that actively participate in their own detection in accordance with current aviation standards. This information can be supplied through specific signals by equipped transponders, such as Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B). This technology relies on GNSS-derived data to broadcast information such as position, ground speed, track angle, vertical rate, and timestamp over an RF channel. Such systems allow air vehicles to receive continuous and precise traffic information of surrounding aircraft. However, current ADS-B implementations typically lack encryption and authentication, making them sensitive to intentional interference and intrusion, such as spoofing, jamming, or message injection. Furthermore, in scenarios where manned and unmanned aircraft share low-altitude airspace, potential intruders are not equipped with transponders. To address these limitations and extend detection capabilities to noncooperative intruders, alternative sensing technologies must be integrated to provide robust detection of uncooperative conflicts.

Radar is a widely used active sensing technology for intruder detection due to its capability to operate in various weather and lighting conditions. Radars work by transmitting electromagnetic pulses and analyzing the time delay, Doppler shift, and amplitude of the reflected signals. Range resolution is determined by the transmitted pulse bandwidth. Angular resolution depends on antenna aperture and beamforming method. While radar offers long detection ranges to several kilometers and simultaneous multi-target tracking, its performance can be degraded by clutter, precipitation, or limited scanning coverage, which imposes trade-offs between Field of View (FoV) and update rate.

Thermal sensors detect emitted radiation in the long-wave infrared (IR) spectrum, providing low-light and night-time detection capability. Compared to visual cameras, thermal sensors have a lower angular resolution. Furthermore, the effectiveness of these sensors depends strongly on temperature contrast and atmospheric absorption, although their comparatively low data rates reduce onboard computational load.

Vision sensors are passive systems that extract information from visible light to perform object detection, classification, and tracking. They offer high spatial and angular resolution, which depends on sensor size, and lens optics. Wider FoVs reduce pixel density and effective operation range. High-resolution images produce substantial data rates that require efficient onboard processing. Vision systems are highly sensitive to environmental factors, such as illumination variations, glare, shadows, rain, or fog, which can reduce detection accuracy or cause false alarms.

LiDAR sensors emit laser light to illuminate their surrounding and analyze the reflected pulses to measure distances. This allows to localize objects in 3D and its usage in low-light conditions. Moreover, it overs a wide FoV up to 360° coverage. Nevertheless, this sensor type produces large amounts of data and it remains expensive, despite the growing availability of more affordable models. In addition, smaller sensors are constrained by limited range, and their performance can degrade under adverse weather conditions.

Each sensor type exhibits inherent limitations described in the previous paragraphs and summarized in

Figure 2, which has resulted in relatively limited research on single-sensor approaches within this research field. For instance, Aldao et al. [

27] investigate a LiDAR-based system, while Corucci et al. [

28] present a radar-based solution. However, no single technology can currently provide accurate, continuous, and robust information on all airspace participants. This motivates the use of multi-sensor systems, in which complementary sensing technologies are combined to enable more reliable detection of uncooperative intruders. Even cooperative surveillance technologies such as ADS-B can be improved through the integration with complementary sensors to achieve enhanced intrusion detection and increased robustness.

Much research can be found about intruder detection systems composed by multiple sensors. The most common combinations of sensor technologies are optical, IR and radar, like the system proposed by Fasano et al. in [

29,

30] where a Detect and Avoid (DAA) system composed by pulsed Ka-Band radars, optical and IR cameras is proposed. Similarly, in [

31], Salazar et al. proposed a DAA system for a fixed wing UAV composed of a Laser Radar (LADAR), a Millimeter Wave (MMW) radar, optical cameras, and IR cameras. Other sensor technologies which are gaining interest in the scientific community for the development of DAA systems are LiDARs, whose integration in a DAA system together with radar sensors is discussed by de Haag et al. in [

32]. Similarly, in [

33] the development of a DAA system is carried out using a LiDAR sensor in combination with a stereo-camera.

For the detection of intruders in the airspace, either a collaborative approach between airborne and ground-based sensors can be implemented, or to rely solely on ground-based sensors approaches. Coraluppi et al. in [

34,

35], described a detection system composed of diverse airborne and ground-based sensors. In [

36], the development of a DAA system composed by diverse ground-based sensors are described.

Table 2 shows a summary of the sensor technologies surveyed.

3.1.2. Classical Approaches for Detection

Based on these sensor characteristics and operating principles, numerous algorithms have been proposed in the literature for detecting intruders in the airspace using sensor data. Each algorithm is tailored to a specific sensing modality and exploits the particular characteristics and functioning of the sensor for which it is designed.

For

ADS-B, research focuses on data validation—flagging intrusions and anomalies without modifying the ADS-B protocol itself to avoid costly changes. Early work by Kacem et al. [

37] combined lightweight cryptography with flight-path modeling to verify message authenticity and plausibility with negligible overhead. Leonardi et al. [

38] instead used RF fingerprinting to extract transmitter-specific features from ADS-B signals, distinguishing legitimate from spoofed messages (reporting detection rates up to 85% with low-cost receivers). Ray et al. [

39] propose a cosine-similarity method to detect replay attacks in large SDR datasets, successfully identifying single, swarm, and staggered scenarios.

Radar target detection typically relies on Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) processing [

40]. CFAR adaptively sets thresholds—often via a sliding-window estimate—to maintain a specified false-alarm probability; many practical systems use CA-, OS-, GO-CFAR and related variants. Recent work refines CFAR for real-time, cluttered settings. Sim et al. [

41] for instance, present an FPGA-optimized CFAR for airborne radars, sustaining high detection performance under load. Complementarily, Safa et al. [

42] introduce a low-complexity nonlinear detector (kernel-inspired, correlation-based) that replaces the statistical modeling step in classical CFAR, outperforming OS-CFAR for indoor drone obstacle avoidance where dense multipath/clutter degrades CFAR. Beyond CFAR, Doppler and micro-Doppler methods exploit target motion for the detection [

43]. Regardless of the specific detector, low–slow–small (LSS) UAVs remain challenging to detect with a radar sensor. Classical CFAR schemes struggle to reliably detect targets with low Radar Cross Section (RCS), while Doppler-based methods have difficulties with slow-moving objects. To address these algorithmic limitations, Shao et al. [

44] reformulate and retune a classical CFAR-based processing chain to improve LSS detection in complex outdoor environments.

For

thermal sensors, small-target detection is often based on simple intensity thresholding. However, this becomes challenging in low-resolution imagery, where targets occupy only a few pixels and their contrast against clutter is low. To address this, Jakubowicz et al. [

45] propose a statistical framework for detecting aircraft in very low-resolution IR images (

) that combines sensitivity analysis of simulated IR signatures, quasi–Monte Carlo sampling of uncertain conditions, and detection tests based on level sets and total variation. Experiments on 90,000 simulated images show that these level-set–based statistics significantly outperform classical mean- and max-intensity detectors, particularly under realistic cloudy-sky backgrounds modeled as fractional Brownian noise. Complementary to this, Qi et al. [

46] formulate IR small-target detection as a saliency problem and exploit the fact that point-like targets appear as isotropic Gaussian-like spots whereas background clutter is locally oriented. They use a second-order directional derivative filter to build directional channels, apply phase-spectrum–based saliency detection, and fuse the resulting maps into a high–signal-to-clutter “target-saliency” map from which targets are extracted by a simple threshold, achieving higher SCR gain and better ROC performance than several classical filters on real IR imagery with complex backgrounds.

For

Visual sensors, target detection is usually performed from image sequences from which appearance cues (e.g., shape, texture, apparent size) are extracted to localize obstacles and support trajectory prediction, thereby extending situational awareness. High target speed, agile maneuvers, cluttered backgrounds, and changing illumination remain key challenges, especially for reliably distinguishing cooperative from noncooperative aircraft at useful ranges. Optical flow is a classical approach for vision-based CA; Chao et al. [

47] compared motion models that use flow for UAV navigation. However, standard optical-flow methods are insensitive to objects approaching head-on, as such motion induces little lateral displacement in the image. Mori et al. [

48] mitigate this by combining SURF feature matching and template matching across frames to track relative size changes, enabling distance estimation to frontal obstacles. Mejías et al. [

49] proposed a classical vision-based sense-and-avoid pipeline that combines morphological spatial filtering with a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) temporal filter to detect and track small, low-contrast aircraft above the horizon, estimating the target’s bearing and elevation as inputs to a CA control strategy. This work was extended by Molloy et al. [

50] to the more challenging below-horizon case by adding image registration and gradient subtraction, while retaining HMM-based temporal filtering to robustly detect intruding aircraft amid structured ground clutter. Another noteworthy study is presented by Dolph et al. [

51], where several classical computer-vision pipelines for intruder detection—including SURF feature matching, optical-flow tracking, FAST-based frame differencing, and Gaussian-mixture background modeling—are systematically evaluated, providing insight into their practical performance and limitations for long-range visual DAA.

LiDAR sensors deliver accurate distance measurements and 3D data that help differentiate tiny, fast-moving objects such as drones from other aerial targets through their motion and size patterns by analyzing and interpreting the point cloud data. Therefore, classical approaches focusing on point cloud clustering techniques to detect objects of interest. Aldao et al. [

52] used a Second Order Cone Program (SOCP) to detect intruders and estimate their motion. Based on this information, avoidance trajectories are computed in real time. Dewan et al. [

53] used RANSAC [

54] to estimate motion cues combined with a Bayesian approach to detect dynamic objects. Their approach effectively addresses the challenges posed by partial observations and occlusions. Lu et al. [

55] used density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) to make a first clustering step followed by an additional geometric segmentation method for dynamic objects by using an adaptive covariance Kalman filter. Their learning free technique enables real-time tracking and CA onboard. While DBSCAN is good for uniform point cloud density, it shows weaknesses when segment obstacles with low density. Zheng et al. [

56] try to overcome this limitation by developing a new clustering method called clustering algorithm based on relative distance and density (CBRDD).

Classical techniques, in contrast to ML approaches, require no training and thus do not depend on the extensive datasets needed for ML models. Nonetheless, over all mentioned sensor types purely classical (non–AI) vision pipelines for object detection are increasingly being replaced by learning-based methods in modern systems because ML approaches solve many limitations that classical techniques cannot overcome which is examined in detail in the subsequent section.

3.1.3. Machine Learning Approaches for Detection

AI-based methods in this field have advanced rapidly in recent years. Deep learning approaches, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), consistently outperform traditional techniques by handling complex scenarios, diverse object appearances, and dynamic environments where classical algorithms often struggle.

Real-time performance is equally critical, and many approaches rely on YOLO-family detectors [

57] for their strong accuracy–speed balance. Beyond CNN-based architectures, transformer-based models have also gained prominence. DETR [

58] introduced an anchor-free, end-to-end paradigm that models images as sequences of patches, integrates global context, and directly predicts bounding boxes and categories — eliminating anchor boxes and non-maximum suppression (NMS). Although later variants improve efficiency, they still fall short of real-time requirements for UAV operations. RF-DETR [

59] addresses this limitation through a hybrid encoder and IoU-aware queries, establishing the first real-time end-to-end detector. CNNs offer efficiency and maturity, transformers provide enhanced global context, and emerging foundation models leverage the strengths of both: they learn generalized, transferable representations, support multiple tasks, and can leverage massive unlabeled or weakly labeled datasets.

The number of available datasets for both single and multiple sensor configurations in the context of aerial object detection and tracking has grown in parallel with these methodological advancements, reflecting the increasing interest in AI-driven detection of aerial objects. In this regard, not only the volume of data but also its quality, representativeness, and fidelity to real-world conditions are critical, as they directly influence model performance, generalization, and robustness. To enable reliable pattern recognition and decision-making, datasets must therefore provide both high-quality samples and sufficient variability while minimizing inherent biases.

Table 3 shows a collection of available open source datasets recorded from different sensors to support ML-based aerial object detection from moving as well as stationary sensor setups.

The Airborne Object Tracking Dataset [

60] published in 2021 contains nearly 5k high resolution grayscale flight sequences resulting in over 5.9M images with more than 3.3M annotated airborne objects and is one of the largest public available datasets in this area. Vrba et al. [

61] created a dataset for UAV detection and segmentation in point clouds. It consists of 5.455 scans from two LiDAR types and contain three UAV types. To compensate for the weaknesses of a specific sensor type, multi-modal approaches are increasingly being developed as well as their corresponding datasets. Yuan et al. [

62] published a multi-modal dataset containing 3D LiDAR, mmWave radar and audio data. Patrikar et al. [

63] published a dataset combining visual data with speech and ADS-B trajectory data while Svanström et al. [

64] collected 90 audio clips, 365 IR and 285 RGB videos. However, acquiring real-world recordings to generate datasets presents significant challenges due to the high time and cost requirements, as well as the difficulty of covering certain scenarios (e.g., collisions with specific objects like birds). To address these limitations, AI-supported data annotation and synthetic generated datasets serve as a valuable alternative. While the first technique decreases time and manual annotation effort, the latter one enables the generation and validation of initial hypotheses using the developed methodologies in the absence of real data. UAVDB [

65] combined bounding box annotations with predictions of the foundation model SAM2 to generate high-quality masks for instance segmentation. Lenhard et al. [

66] published SynDroneVision, a RGB-based drone detection dataset, for surveillance applications containing diverse backgrounds, lighting conditions, and drone models. In contrast to the previous Aldao et al. [

67] developed a LiDAR Simulator to generate realistic point clouds of UAVs. After reviewing the current data landscape and briefly examining techniques to address missing data, the discussion now turns to potential machine learning applications that require such datasets to train and fine-tune the AI models. In the following paragraphs, AI approaches are discussed for each sensor.

For

ADS-B, research focuses on different AI-supported prediction approaches, which are useful to identify abnormal flight behavior or other safety-critical anomalies. Shafienya et al. [

68] developed a CNN model with Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) deep model structure to predict 4D flight trajectories for long-term flight trajectory planning. While the CNN part is used for spatial feature extraction, GRU extracts temporal features. The TTSAD model [

69] is focusing on detecting anomalies in ADS-B data by first predicting temporal correlations in ADS-B signals and further applying a reconstruction module to capture contextual dependencies. Finally, the reconstruction differences are predicted to determine anomalies. Ahmed et al. [

70] introduced a deep learning architecture using TabNet, NODE, and DeepGBM models to classify ADS-B messages and detect attack types, achieving up to 98% accuracy in identifying anomalies. Similarly, Ngamboé et al. [

71] developed an xLSTM-based intrusion detection system that outperforms transformer-based models for detecting subtle attacks, with an F1-score of 98.9%.

With

Radar sensors, the velocity and range of airborne targets can be derived. Zhao et al. [

72] focused on target and clutter classification by applying a new GAN-CNN-based detection method. By combining GAN and CNN architectures they are able to locate the target in multidimensional space of range, velocity and angle-of-arrival. Wang et al. [

73] presented a CNN-based method for the detection of UAVs in the airspace with a Pulse-Doppler Radar sensor. The method consists in a CNN with two heads: a classifier to identify targets and a regressor that estimates the offset from the patch center. Their outputs are then processed by a NMS module that combines probability, density, and voting cues to suppress and control false alarms. Tests with simulated and real data showed that the proposed method outperformed the classical CFAR algorithm. Tm et al. [

74] propose a CNN architecture to perform single shot target detection from R-D data of an airborne radar.

Thermal sensors pose challenges for AI detection methods because thermal noise, temperature fluctuations, and cluttered environments degrade signal clarity and consistency. To overcome these challenges, GM-DETR [

75] provides a fine-grained context-aware fusion module to enhance semantic and texture features for IR detection of small UAV swarms combined with a long-term memory mechanism to further improve the robustness. Gutierrez et al. [

76] compared popular detector architectures which are YOLOv9, GELAN, DETR and ViTDet and showed that CNN-based detectors stands out for real-time detection speed while transformer-based models provide higher accuracies in varying and complex conditions.

For

Visual sensors AI models are used for detection, supported by additional filtering and refinement processes. For instance [

77,

78] used AI-based visual object detection. Arsenos et al. [

79] used an adapted YOLOv5 model. Their approach allows to detect UAVs at distances of up to 145 meters. Yu et al. [

80] used YOLOv8 combined with an additional slicing approach to further increase detection accuracy of tiny objects. Approaches like [

81] employed CenterTrack a tracking-by-detection method resulting in a joint detector-tracker by representing objects as center points and modeling only the inter-frame distance offsets. Karampinis et al. [

82] took the detection pipeline from [

79]. They formulated the task as an image-to-image translation problem and employed a lightweight encoder–decoder network for depth estimation. Despite current limitations of foundation models regarding processing speed, such models facilitate multi-task annotation generation while requiring minimal supervision as described in [

83].

For

LiDAR sensors ML-models learn geometric properties of point clouds to identify and detect objects of interest. Key challenges include large differences in point cloud density and accuracy among LiDAR sensors, as well as motion distortion and real-time processing requirements. Xiao et al. [

84] developed an approach based on two Lidar sensors. The LiDAR 360 gives a 360° coverage while the Livox Avia provides focused 3D point cloud data for each timestamp. Objects of interest are identified by using a clustering-based learning detection approach (CL-Det). Afterwards, DBSCAN is used to further cluster the detected objects. By combining both sensors, they demonstrate the potential for real-time, precise UAV tracking in sparse data conditions. Zhange et al. [

85] presented DeFlow, which employs GRU refinement to transition from voxel-based to point-based features. A novel loss function was developed that compensates the imbalance between static and dynamic points.

The field of AI-based object detection and tracking has made continuous progress in tackling challenges such as reliably tracking of very small aerial objects with unpredictable flight patterns. Key research directions include achieving real-time performance, modeling and uncertainty prediction, and effectively leveraging appearance information for robust tracking.

Table 4 provides the summary of the presented classical and ML approaches for aerial object detection examined in this survey.