1. Introduction

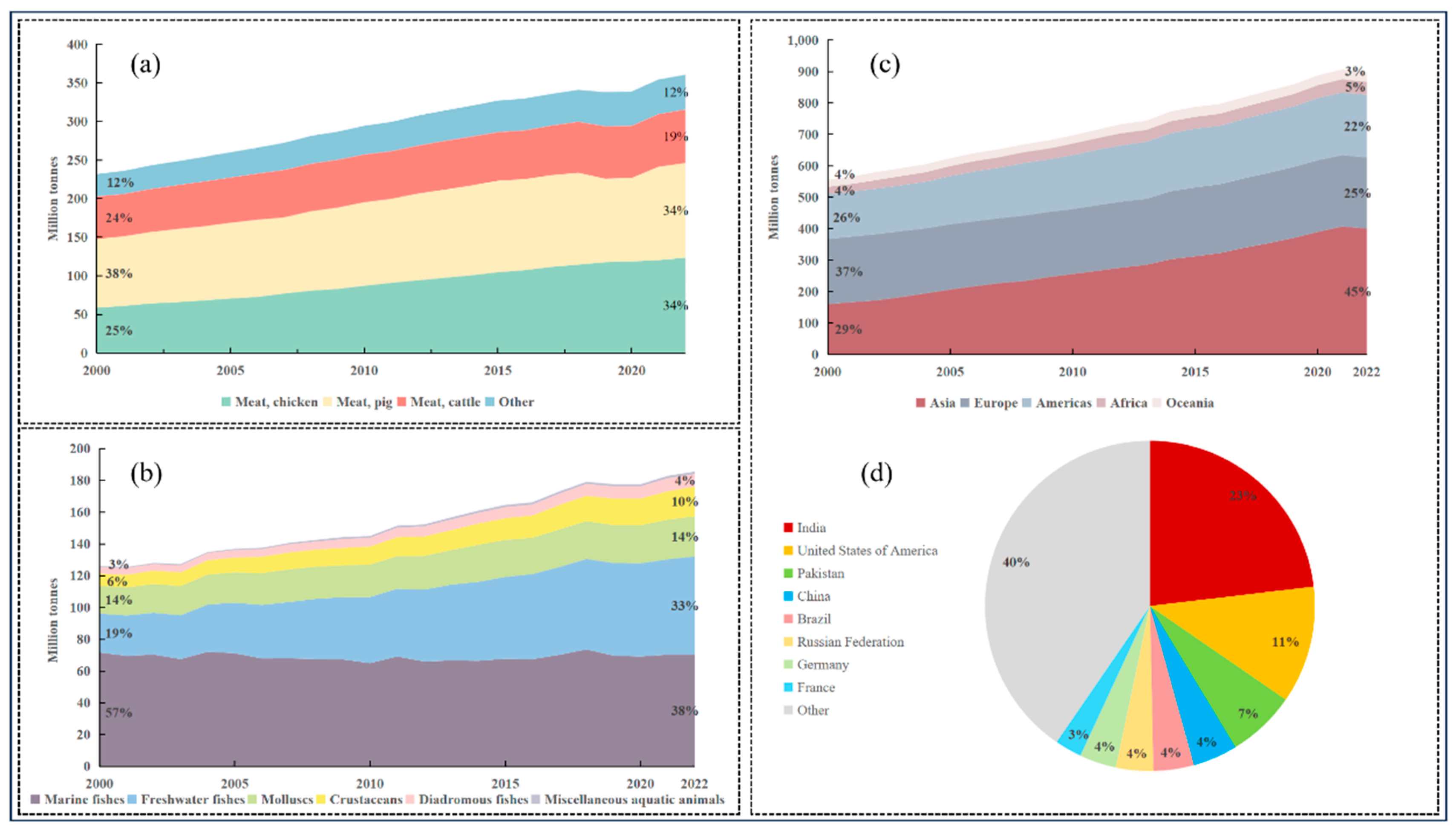

Over the past two decades, surging demand for animal protein has driven unprecedented growth in the livestock and aquaculture sectors. Global meat production surged from ~230 million tons in 2000 to ~360 million tons in 2020 (2.2% annual growth), with poultry emerging as the dominant category, rising from 25% to 34% of total output (

Figure 1a). Concurrently, fisheries production (encompassing capture and aquaculture) grew from ~126 million tons to ~185 million tons (1.9% annual growth), marked by aquaculture overtaking wild-capture fisheries to account for 54% of global supply by 2020 (

Figure 1b). Milk production has followed a similarly steep trajectory, expanding from ~556 million tons to ~897 million tons during the same period (2.4% annual growth) (

Figure 1c). By 2022, India (23%), the United States (11%), Pakistan (7%), China (4%), and Brazil (4%) collectively contributed nearly half of global milk output (

Figure 1d). This production intensification—particularly in poultry and aquaculture—prioritizes efficiency but fosters conditions conducive to high-intensity antimicrobial use (

World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Pocketbook 2024, 2024). The escalating reliance on prophylactic and growth-promoting antimicrobial applications is correlated with the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in food chains. Animal agriculture constituted 73% of global antimicrobial consumption in 2017, with projections indicating an 8% increase from 99,502 metric tons in 2020 to 107,472 metric tons by 2030 (Ranya et al., 2023). The global food system faces a critical paradox: animal-derived foods provide essential nutrients for billions, yet their intensified production increasingly threatens food safety through the residues of veterinary drugs (VDRs).

Veterinary pharmaceutical misuse stems from multifaceted challenges, including knowledge gaps among farmers, economic pressures favoring short-term gains, and fragmented regulations. Key contamination pathways include feedstuff contamination through medicated premixes or cross-contamination, therapeutic overuse such as incorrect dosages or extended treatment durations, non-adherence to withdrawal periods, and environmental dissemination via manure, wastewater, and soil runoff. Human exposure occurs through the consumption of contaminated animal products, uptake via polluted water or crops, and occupational contact, thereby heightening the risks of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), endocrine disruption, allergic reactions, and organotoxicity.

Mitigating this crisis requires a multifaceted approach. Central tenets include: Promoting judicious antimicrobial use through evidence-based guidelines, strict adherence to dosage regimens, and enforced withdrawal periods; Strengthening capacity-building initiatives for stakeholders—including veterinarians, producers, and processors—via training programs and extension services to foster awareness of residue risks and regulatory compliance; Enhancing post-harvest surveillance through advanced analytical techniques (e.g., liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, nanomaterial-based biosensors) to detect trace residues in complex food matrices; and Accelerating the development of antimicrobial alternatives, such as bacteriophages, bacteriocins, bioactive plant extracts, and probiotics, to reduce dependency on conventional antibiotics.

In recent years, numerous professional studies have addressed the above concerns from various perspectives. However, these studies are relatively scattered and cannot provide a systematic and comprehensive understanding of recent developments. This systematic review will provide a comprehensive synthesis of the current state of knowledge concerning VDRs in the food chain through the critical examination of their origins, exposure pathways, and associated health/environmental hazards. Particular emphasis is placed on exploring innovative mitigation strategies to reduce such residues in food products, with the dual objectives of safeguarding public health and promoting ecological sustainability in livestock production systems.

2. The Sources of Veterinary Drug Residues in Food Chains

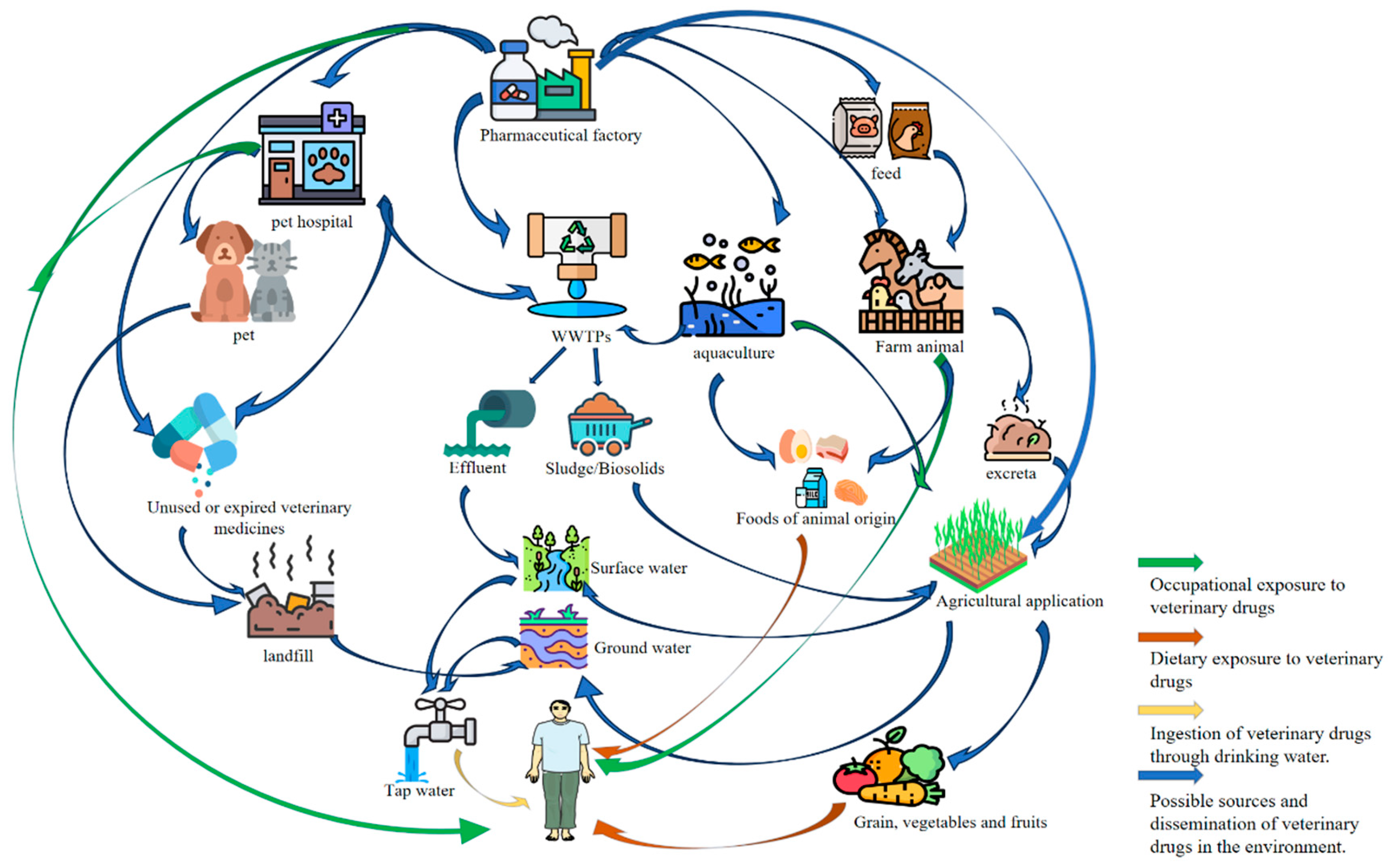

VDRs, encompassing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), their metabolic byproducts, and process-related impurities, represent persistent contaminants that infiltrate edible animal tissues following the administration of therapeutic or prophylactic drugs. These residues emerge as critical food safety concerns due to their multi-origin nature and potential human health impacts. As shown in

Figure 2, a systematic categorization of contamination pathways reveals four primary interfaces where VDRs penetrate the agro-food chain. Firstly, Feed Production Vulnerabilities Contamination initiates at primary production through cross-contamination of feedstuffs with APIs, often exacerbated by non-compliant inclusion of antimicrobial growth promoters exceeding regulatory thresholds. Secondly, Husbandry Practices and Withdrawal Protocol Breaches. Suboptimal rearing conditions frequently culminate in unauthorized drug administration practices, including prolonged off-label use, dosage deviations, and altered administration routes—particularly evident during withdrawal periods before slaughter. There is also the widespread misuse of sedatives/anesthetics to reduce transport stress and the illegal use of preservatives in carcass processing. In addition, Slaughterhouse Malpractices, Including Illicit β-agonist administrations—most notably clenbuterol hydrochloride ("lean meat agents")—to enhance carcass leanness, coupled with indiscriminate pesticide applications during processing, introduce cumulative toxicological risks. Lastly, Environmental Dissemination and Bioaccumulation: Beyond direct inputs, agro-environmental residues cyclically re-enter food chains via contaminated water/soil matrices, perpetuating a "farm-to-fork" contamination cycle. This environmental reservoir amplifies exposure risks across all trophic levels.

2.1. Feed Contamination

The quality and safety of animal feed not only exert a profound impact on the healthy growth of livestock and poultry but also possess an indirect influence on food safety and human health. Incidents about the safety of animal products caused by feed and feeding inputs occasionally arise.

Feed represents a critical vector for VDRs in animal-derived foods. Risks primarily originate from two sources: illicit incorporation of veterinary drugs into feed formulations and historical reliance on antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs). Since the 1946 discovery of antibiotics' growth-enhancing properties (Moore et al., 1946), sub-therapeutic doses of antibiotics have been systematically administered in intensive farming systems to enhance growth rates, improve feed conversion efficiency, and prevent disease. AGPs demonstrate multifaceted benefits, including reduced morbidity/mortality from subclinical infections, enhanced weight gain, optimized production costs, improved reproductive performance, and superior meat quality (Mărgărita et al., 2022). By the 21st century, nearly 88% of U.S. grower-phase swine received antibiotic-supplemented feed, reflecting widespread adoption in industrialized agriculture (Mărgărita et al., 2022). Furthermore, antimicrobials used during the fermentation or processing of feed components (e.g., vitamins, distillers' grains, insect meal) may inadvertently contaminate finished feeds.

However, the global proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), particularly multidrug-resistant "superbugs," has elevated AMR into a paramount public health crisis. In response, the European Union implemented a comprehensive AGP ban in 2006, with subsequent global restrictions. Nevertheless, non-compliant feed producers continue illicit veterinary drug supplementation to meet market demands for accelerated growth and lean meat yields, often employing unregulated additives that result in hazardous drug accumulation in food animals.

A secondary contamination pathway arises during feed production, transport, and storage. Cross-contamination frequently occurs between feed batches processed on shared equipment, where residual material from antibiotic-containing feeds infiltrates subsequent batches. This phenomenon, influenced by drug physicochemical properties, equipment design, and cleaning protocols, proves particularly challenging to mitigate (McEvoy, 2002). Transport vehicles and storage facilities retaining antibiotic residues further exacerbate contamination risks. Eleni et al. (Eleni et al., 2016) quantified this issue through Monte Carlo simulations, demonstrating that when antimicrobial-containing feeds constitute 2% of national production, approximately 5.5% (95% CI: 3.4–11.4%) of total annual feed output becomes cross-contaminated, with farm-level storage posing the highest contamination probability. Such antibiotic-contaminated feeds constitute a major reservoir of VDRs in animal products, posing significant threats to human health, food safety, and ecological security.

2.2. Irrational Use of Drugs

The irrational use of drugs is characterized by indiscriminate prophylactic administration, non-adherence to prescribed dosage and dosing schedules, incorrect route or site of administration, excessive drug dosage at a single injection site, off-label use of drugs (unauthorized utilization in animals for which they are not approved, usage in another animal species for which they are suitable, treatment of conditions other than those specified), etc. (Rupp et al., 2024), resulting in impaired excretion through normal metabolic processes in animals, leading to increased residual amounts or prolonged retention time. A Ghanaian poultry sector survey revealed tetracyclines as the predominant antimicrobial class, with 86% of farms implementing prophylactic drug regimens. Consequently, 24.3% of sampled farms exhibited tetracycline residues in eggs, of which 92.9% continued commercial egg sales during hen treatment phases. The study also documented regulatory breaches: 44.3% used disinfectants, while 17.4% and 2.6% administered two human-grade antibiotics off-label, violating usage protocols (Johnson et al., 2019). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), limited access to veterinary expertise and weak pharmaceutical regulation exacerbate the risks of antimicrobial misuse. Farm operators frequently self-prescribe antimicrobials based on empirical knowledge rather than professional consultation, predominantly sourcing medications from private veterinary pharmacies. Notably, poultry farmers demonstrate marginally better antimicrobial stewardship than pastoralists in knowledge-attitude-practice metrics (Caudell et al., 2020).

2.3. Too Short a Withdrawal Period

The withdrawal period is defined as the period from the discontinuation of drug administration in animals to the approval for the slaughter or marketing of their products (like milk and eggs). During this period, drug residues in the animal's body are gradually metabolized and excreted, with residue levels decreasing below specified limits. The length of the withdrawal period is influenced by various factors, including animal species, type of drug, formulation, dosage, route of administration, distribution within the body, and farming environment (Yongtao et al., 2022).

Global regulatory fragmentation persists, as withdrawal periods are established based on jurisdictional Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs). Although drug labels specify withdrawal timelines, practical compliance is undermined by diagnostic variability (disease severity/type), off-protocol dosing, and economic constraints. While pre-slaughter residue testing is theoretically mandated, small-scale producers often lack resources for analytical verification, prioritizing therapeutic outcomes over residue control and AMR mitigation ("Validation of the Declared Withdrawal Periods of Antibiotics," 2018).

Non-compliance manifests as premature slaughter—whether intentional (due to economic incentives) or accidental (resulting from management errors)—leading to MRL violations. A Bangladesh study of 4,200 post-withdrawal poultry samples detected 55% antibiotic residue exceedances, with fluoroquinolones (enrofloxacin (ENR): 38%; ciprofloxacin: 27%) demonstrating chronic non-compliance, revealing systemic governance failures in reconciling livestock productivity and food safety (Hjorth et al., 2024) ("Validation of the Declared Withdrawal Periods of Antibiotics," 2018).

2.4. Environmental Pollution

Veterinary antibiotics enter the environment primarily through livestock excreta (urine/feces), wastewater effluent, improper drug disposal, pharmaceutical production discharge, and aquaculture runoff (

Figure 2). Climate change and water scarcity drive the reuse of treated wastewater and livestock manure in agriculture, offering resource efficiency but introducing risks of antibiotic residues, resistance genes, and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) into ecosystems (Cabello et al., 2016).

In livestock farming, 30–90% of administered antibiotics are excreted as active compounds or metabolites, with manure containing concentrations ranging from tens of mg/kg to higher levels (Zhou et al., 2020). Paul et al. (Paul et al., 2017) demonstrated cross-contamination via pasture, detecting phenylbutazone residues in grazing cattle weeks after initial exposure. Similarly, aquaculture discharges 70–80% of antibiotics into surrounding water and sediment due to low aquatic uptake (Jie et al., 2023). These pollutants infiltrate agricultural systems via manure fertilization, wastewater irrigation, and biosolid reuse, contaminating soil and water through leaching or runoff (Jie et al., 2023). Antibiotic emissions correlate directly with usage rates, with soil acting as the primary reservoir. In China, annual emissions of 80 veterinary antibiotics (2010–2020) ranged from 23,110 to 40,850 tons, with 56%, 23%, and 18% accumulating in soil, freshwater, and marine systems, respectively (Shuaiqi Li et al., 2024).

A wide range of antibiotics released into the environment through various channels is absorbed by plants, and certain antibiotics even accumulate within plants, entering the food chain through plant uptake. Hu et al. (Hu et al., 2010) employed a simplistic migration model to prognosticate the accumulation of antibiotics in soil and discovered that vegetables absorb antibiotics in soil primarily through water transportation and passive absorption. The separate sampling and detection of antibiotics in leaves, stems, and roots revealed that the highest concentration of antibiotics was present in plant leaves, while the lowest concentration was in roots, indicating biological accumulation. Moreover, since the 1950s, antibiotics have been employed to control specific bacterial diseases in high-value fruits, vegetables, and ornamental plants. At present, the most commonly used antibiotics on plants are streptomycin (SM) and a small amount of oxytetracycline. For instance, the United States Environmental Protection Agency-approved SM and oxytetracycline applications combat citrus greening disease in Florida (McKenna, 2019).

3. Human Exposure to Veterinary Drug Residues

The widespread use of veterinary antibiotics in livestock production, driven by growth-promoting agents and therapeutic interventions, has significantly heightened concerns over human exposure to residual antimicrobial compounds through animal-derived food products. Multimodal pathways exist for potential contact with these hazardous substances, including both direct and indirect environmental dissemination. Antibiotic residues have been ubiquitously detected across diverse environmental matrices. In aquatic compartments, contamination affects groundwater (GW) aquifers, propagates through SW systems, infiltrates municipal drinking water supplies, and persists in wastewater treatment effluents. Within terrestrial ecosystems, residues infiltrate river sediments, accumulate in agricultural soils, adsorb to atmospheric particulates, and even translocate into plant tissues (e.g., leafy vegetables). This environmental persistence creates a nested web of exposure risks. Primary routes include ingestion of contaminated foodstuffs and drinking water, while secondary pathways involve dermal absorption through contact with polluted soil/water or inhalation of antibiotic-laden aerosols (

Figure 2).

3.1. Food Intake

The global proliferation of antibiotic use in intensive livestock and aquaculture systems has rendered human exposure to VDRs through animal-derived foods virtually inescapable. As primary dietary sources of high-quality protein, lipids, and essential amino acids, these products—including meats (pork, beef, lamb), poultry (chicken, duck), eggs, seafood (fish, crustaceans, mollusks), and dairy—form staple components of daily nutrition. Compounding this inevitability, cumulative evidence indicates that animal-derived foods are the primary pathway for unintentional human antibiotic intake. Regulatory countermeasures, such as veterinary drug restrictions in the EU, US, and Japan, alongside China's implementation of MRLs since the late 1990s, have yet to fully mitigate contamination. Persistent veterinary drug violations are documented globally. For example, LC-MS/MS analysis of 146 poultry samples from Fujian, China, detected 39 antibiotics (quinolones, tetracyclines, sulfonamides) in 47.3% of samples, with 11.6% exceeding MRLs. Notably, 26% of egg samples surpassed regulatory thresholds (Yang et al., 2020). Separately, studies in Ethiopian slaughterhouses reported oxytetracycline residues above MRLs in 10% of kidney samples and 3.3% of muscle samples (Abdeta et al., 2024). Beyond animal products, environmental dispersion facilitates the uptake of antibiotics in plant-based foods. Analysis of commercial vegetables (lettuce, tomatoes, cauliflower, and broad beans) detected seven antibiotics (16 targeted) at 0.09–3.61 ng/g fresh weight (Tadić et al., 2021), confirming produce as a secondary exposure vector (

Figure 2).

The FAO/WHO Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) addresses these risks through global health evaluations, establishing Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) thresholds based on chronic exposure toxicology. Contemporary studies underscore persistent challenges: UK market analyses found >35% of 34 animal-derived foods exceeding ADIs for amoxicillin, ampicillin, and ENR (Seo et al., 2024). Such multi-residue occurrences not only reflect the complexity of systemic contamination but also potentiate synergistic health impacts.

Acute exposure consequences manifest through both historical precedents and emerging threats. High-concentration residues at livestock injection sites create localized "hotspots," where single-meal consumption of affected meat cuts induces acute toxicity. This mechanism underlies Europe’s clenbuterol poisoning outbreaks linked to veal liver and beef consumption (Jorge et al., 2005). Immediate health outcomes range from allergic reactions and gastrointestinal distress to life-threatening toxicity, emphasizing the dual necessity of chronic risk management and acute exposure prevention frameworks.

3.2. Potable Water

Economic growth has accelerated the production and consumption of antibiotics for agricultural purposes, resulting in a greater amount of antibiotics being discharged into the environment and being present in aquatic environments–including SW, GW, and, surprisingly, tap water. Antibiotic residues originating from livestock farming, aquaculture operations, and pharmaceutical or hospital effluents frequently persist through wastewater treatment processes, ultimately contaminating SW ecosystems (Danner et al., 2019). For instance, along the northern Persian Gulf coastline in Iran, azithromycin, erythromycin, norfloxacin, and tetracycline were detected in SWs at average concentrations ranging from 1.21 to 51.50 ng/L (Kafaei et al., 2018). Notably, regions hosting API manufacturing facilities exhibit extreme contamination levels. Investigations near major API production zones revealed well water in six adjacent villages contaminated with high concentrations of ciprofloxacin, ENR, moxifloxacin, and trimethoprim, while nearby lakes contained ciprofloxacin and ENR at concentrations exceeding 6,500 ng/L (Jerker et al., 2009). These findings highlight the critical role of inadequate wastewater management in pharmaceutical industries in exacerbating antibiotic pollution across the surface, groundwater, and drinking water supplies.

Despite water treatment protocols, residual antibiotics persist in drinking water systems, particularly in regions reliant on GW. Regional disparities in contamination patterns are evident: in Baghdad, Iraq, ciprofloxacin demonstrated the highest detection frequency among antibiotics identified in treated drinking water from two municipal plants (Mahmood et al., 2019). Comparative analyses of water sources in China revealed the presence of 58 antibiotics in filtered tap water samples, with roxithromycin being the most prevalent. In contrast, foreign-brand bottled water sold in China contained fewer contaminants (36 antibiotics) but elevated dicloxacillin levels (Ben et al., 2020). The pervasive release of antibiotics into aquatic environments has been directly linked to the proliferation of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs). This phenomenon is exacerbated by the coupling of ARGs with MGEs, which facilitates horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and accelerates the dissemination of resistance traits, posing a significant challenge to global public health (Cabello et al., 2016).

3.3. Occupational Exposure

The widespread use of veterinary antibiotics in livestock production substantially elevates risks of ARB strain development. Such resistance traits can be disseminated to humans through direct animal contact, food consumption, wastewater exposure, and fecal contamination pathways (Koch et al., 2017). Prolonged occupational exposure in livestock environments profoundly alters human microbial ecology: studies reveal that farm workers subjected to microbe-rich settings for over 5 hours exhibit persistent skin microbiome restructuring and ARG enrichment, establishing them as potential vectors for transmitting resistant genes to broader populations (Chen et al., 2024). This risk is particularly pronounced among workers exposed to subtherapeutic antibiotic levels. For instance, poultry workers demonstrate a 32-fold higher likelihood of harboring gentamicin-resistant E. coli compared to the general public, with livestock farmers also showing elevated carriage rates of multidrug-resistant E. coli (Price et al., 2007). Occupational exposure routes include dermal absorption and respiratory intake during routine practices. Analyses of pig farm dust collected over two decades identified up to five antibiotics per sample (e.g., tylosin, tetracyclines, sulfadiazine), indicating chronic inhalation risks for workers (Gerd et al., 2003). Biological monitoring further corroborates these hazards: urinary antibiotic concentrations in poultry workers surpassed both bacterial inhibitory thresholds and safe daily intake limits, confirming systemic exposure (Paul et al., 2019).

Pharmaceutical production personnel face parallel risks. Workers engaged in antibiotic manufacturing processes—including grinding, granulation, and tablet compression—are routinely exposed to antibacterial agents. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that occupational contact correlates with the development of progressive multidrug resistance (MDR). For example, antibiotic facility workers exhibit significantly higher MDR bacterial carriage rates than non-exposed populations, with resistance severity escalating alongside employment duration (Sarker et al., 2014). These findings underscore the dual occupational hazards posed by antibiotic use in agriculture and the pharmaceutical industries.

4. Toxic Effects of Drug Residues in Food

Pharmacologically active compounds may potentially pose certain latent health risks to humans, encompassing toxicological hazards (acute and chronic toxicity, allergic reactions, carcinogenic, teratogenic, and mutagenic effects) and microbial hazards (disruption of intestinal flora equilibrium, induction of intestinal bacteria to develop resistance). The hazards demonstrate a dose-response relationship, signifying that specific degrees of harm only arise when VDRs accumulate to a certain extent within the human body.

4.1. Acute and Chronic Toxic Effects

Long-term consumption of veterinary drug-contaminated foods can cause acute or chronic toxicity when accumulated residues reach critical thresholds. Acute symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, neurotoxicity, dizziness, and convulsions) may arise from high-dose exposure to fluoroquinolones (Du et al., 2023). Sulfonamides impair kidney function and hematopoiesis, whereas chloramphenicol (CAP) overexposure risks fatal aplastic anemia. Tetracyclines inhibit bone/tooth development by binding to calcium, erythromycin induces acute hepatotoxicity, and gentamicin causes vestibular nerve damage (Arsène et al., 2022). Aminoglycosides are linked to ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity (Peloquin et al., 2004).

VDRs also disrupt endocrine and hormonal systems, interfering with hormone synthesis or activity. This imbalance elevates risks of reproductive disorders, developmental abnormalities, and chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions (Hou et al., 2024). Endocrine-disrupting effects include estrogen-induced feminization in males, skeletal malformations, and carcinogenic impacts on female reproductive organs (Jeong et al., 2010). Such residues may exert reversible or irreversible biological effects on individuals and populations, particularly compromising adolescent growth and development.

4.2. Development of Bacterial Resistance

The escalating crisis of AMR stems predominantly from antibiotic overuse, particularly in livestock production, where consumption volumes exceed human medical applications. This practice facilitates AMR transmission from animals to humans through diverse pathways, with 2020 surveillance data from 87 countries underscoring alarming resistance levels in life-threatening bloodstream pathogens and rising drug resistance in community-acquired infections (Organization, 2022). Recognized as a persistent global health emergency, AMR threatens to precipitate pandemic-scale outbreaks. In 2019 alone, antibiotic-resistant infections directly caused 1.27 million deaths, while drug-resistant pathogens contributed to nearly 50 million fatalities (Abdus et al., 2023). Projections indicate AMR-related mortality could reach 10 million annually by 2050, surpassing cancer deaths (Abdus et al., 2023), with current estimates attributing 5 million annual deaths globally to antimicrobial resistance (Hopkins, 2024). Pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and the ESKAPE group (Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, etc.) exhibit pan-resistance to conventional therapies, exacerbated by agricultural antibiotic use that selects for resistant foodborne pathogens, a trend predicted to amplify future food safety risks (Nathan & Cars, 2014).

Environmental contamination plays a crucial role in the dissemination of AMR. Unregulated antibiotic discharge, coupled with inefficient wastewater treatment systems, allows residual antibiotics and ARGs to persist in ecosystems. Junjie et al. (Junjie et al., 2021) identified 11 ARGs, one integron, and one transposon in water and soil near a Chinese pharmaceutical facility, with downstream ARG abundance significantly exceeding upstream non-polluted areas (p < 0.05). The study further confirmed significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) between MGEs and ARG abundance. HGT mechanisms enable pathogens to acquire resistance traits, propagating multidrug-resistant strains through environmental and biological vectors. The gut microbiomes of humans and animals serve as hotspots for ARG exchange, as evidenced by the presence of quinolone and carbapenem resistance genes in untreated animal feces (Tina et al., 2020).

Human exposure risks extend beyond agricultural settings through three interconnected routes: aquatic systems, food chains, and companion animals (Martinez, 2009). Wastewater treatment deficiencies allow antibiotics and ARGs to infiltrate drinking water supplies, while contaminated irrigation and manure fertilization introduce resistance elements into crops, silently propagating through food systems (Jie et al., 2023). Concurrently, the global rise in pet ownership has established new AMR transmission pathways. Veterinary antibiotic use often relies on empirical prescriptions rather than susceptibility testing, which can foster resistance in pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Notably, 60% of human pathogens originate from zoonotic sources (Klous et al., 2016).

4.3. Cause Dysbiosis of the Flora

The gut microbiota, dominated by diverse bacterial populations exceeding 1,000 species (predominantly anaerobic), represents a vital symbiotic ecosystem. In adults, the intestinal tract harbors approximately 10^14 bacterial cells—tenfold the human cell count—with a collective microbiome encoding over 5 million genes, surpassing host genetic capacity by two orders of magnitude (Felix & Fredrik, 2013). This microbial consortium functionally parallels metabolic organs like the liver, orchestrating critical host processes including nutrient metabolism, skeletal development, immune modulation, and pathogen exclusion. Emerging evidence reveals cross-organ regulatory roles, exemplified by antibiotic-disrupted microbiota altering pulmonary inflammatory responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge (Jacobs et al., 2020). Furthermore, gut microbes biochemically interface with host systems through metabolites and neuromodulators, as demonstrated by microbiota-mediated regulation of the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) system, which governs intestinal motility and secretion (Choo et al., 2023).

Antibiotic exposure disrupts this intricate symbiosis through non-selective antimicrobial activity. While targeting pathogens, broad-spectrum antibiotics indiscriminately eradicate commensal species, precipitating microbiota imbalance (dysbiosis) with systemic repercussions (Ianiro et al., 2016). Clinical studies corroborate these effects: low-dose erythromycin/azithromycin regimens in healthy adults impair microbial carbohydrate metabolism and short-chain fatty acid synthesis, coinciding with altered systemic immune biomarkers (IL-5, IL-10, MCP-1) and metabolic regulators (5-HT, C-peptide) (Choo et al., 2023). Antibiotic-driven diversity loss follows concentration-dependent patterns, as evidenced by moxifloxacin reducing bacterial richness proportionally to dosage (Burdet et al., 2019).

Antibiotic perturbation exhibits heterogeneity across gut microbial populations. Short-term meropenem/gentamicin/vancomycin combination therapy induces Enterobacteriaceae and Peptostreptococcus proliferation alongside Bifidobacterium depletion and diminished butyrate producers—a metabolic shift with potential oncogenic implications given microbiota's role in colorectal carcinogenesis (Palleja et al., 2018). Early-life exposures exert lasting impacts: neonates exposed to intrapartum maternal antibiotics display reduced Bacteroidetes abundance and enriched Firmicutes (particularly Clostridia and Enterococci), establishing dysbiotic trajectories (Azad et al., 2016). These interindividual variabilities in antibiotic susceptibility underscore the complexity of microbiota-host interactions, positioning gut microbial integrity as both a therapeutic target and a vulnerability in modern pharmacotherapy (Armin et al., 2021).

4.4. Carcinogenic, Teratogenic, and Mutagenic Effects

In recent years, scientists have demonstrated that exposure to low doses of antibiotics is correlated with numerous human health issues, including obesity, carcinogenicity, reproductive effects, teratogenicity, and mutagenicity. The genetic toxicity and carcinogenicity of certain antibiotics pose safety hazards to target animals and humans. For instance, Cao et al. (Cao et al., 2018) discovered that the long-term and persistent use of antibiotics can lead to the proliferation of colonic polyps, presenting a potential threat to the development of cancer. The excessive intake of estrogen residues by women may give rise to breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer; aflatoxin and tetracycline can induce liver cancer (Beyene, 2015). Mutagenic drugs contain certain chemicals, such as alkylating agents and DNA base analogs, which can induce mutagenic activity and potentially cause gene mutations or chromosomal breaks, thereby influencing human fertility (Beyene, 2015). SM, kanamycin, and tetracycline are regarded as teratogenic and must be thoroughly avoided during pregnancy since they interfere with fetal development. These drugs can result in hearing impairment and developmental inadequacies (Afshan & Neha, 2021).

4.5. Anaphylaxis

When humans ingest animal food containing allergenic VDRs, the antigenic molecules in the veterinary drugs might bind to immunoglobulin E in the human body. This binding process triggers the release of inflammatory mediators by immune cells, including histamine, which leads to the occurrence of allergic symptoms in the skin and respiratory system, as well as delayed hypersensitivity reactions. Some antibiotics, such as penicillin and sulfonamides, can induce allergic reactions in certain individuals, even anaphylactic shock. Penicillin-type drugs are prone to eliciting allergic reactions, ranging from mild skin reactions and contact dermatitis to anaphylactic shock that can result in death (Arsène et al., 2022). Sulfonamide drugs may impair the hematopoietic function of humans. Tetracyclines mainly cause specific allergic reactions, such as allergic rashes, dermatitis, and respiratory difficulties (Hamilton & Guarascio, 2019).

5. Mitigation Strategies for Drug Residues in Animal-Derived Foods

The control of VDRs in animal-derived food products remains a persistent and multifaceted challenge within contemporary food safety frameworks. This intricate public health issue necessitates coordinated multi-sectoral collaboration, requiring not only scientific husbandry practices and regulatory compliance among animal agriculture practitioners but also strengthened governmental oversight through enhanced policy support and technical advisement from specialized agencies. Parallel to institutional efforts, effective mitigation strategies must incorporate consumer engagement through awareness campaigns and participatory supervision mechanisms. Implementation of integrated monitoring networks, coupled with precision education initiatives for livestock producers and standardized quality management protocols, enables stakeholders to collectively advance judicious veterinary drug use in farming operations. Such multidimensional governance approaches demonstrate the substantial potential to minimize non-compliant residue occurrences without compromising production efficiency. Furthermore, the strategic development of antibiotic alternatives – encompassing bacteriophage therapies, antimicrobial peptides, and plant-derived compounds (e.g., botanical extracts) – has emerged as a critical pillar in sustainable livestock systems. These innovations provide evidence-based strategies to simultaneously ensure food safety, optimize animal health outcomes, and address AMR concerns across the agri-food chain.

5.1. Rational use of Antibiotics in Animal farming

Vaccination serves as a cost-effective cornerstone in reducing high-impact diseases and antibiotic reliance, particularly in antibiotic-free poultry production systems, where it mitigates infections like coccidiosis and curbs AMR emergence (Hopkins, 2024). Equally critical is the rational selection of veterinary drugs, as substandard or counterfeit antibiotics—reported in 6.5% of tested samples, often with incorrect API content or mislabeled components—compromise treatment efficacy and exacerbate AMR risks (Vidhamaly et al., 2022). Farmers must prioritize drugs from licensed manufacturers with valid certifications (e.g., Veterinary Drug GMP) to ensure quality.

Optimal administration methods and drug compatibility further enhance therapeutic outcomes. Intravenous or intramuscular routes ensure rapid absorption, while synergistic combinations (e.g., ivermectin + abamectin) broaden antimicrobial spectra, reduce dosages, and combat resistant nematodes (Ballent et al., 2020). Conversely, incompatible pairings (e.g., aminoglycosides + magnesium sulphate) may amplify toxicity. Pharmacokinetic interactions, such as altered drug metabolism, and pharmacodynamic effects, like vitamin D alleviating levofloxacin-induced nephrotoxicity, underscore the need for evidence-based compatibility (Mhaibes & Abdul-Wahab, 2023).

Targeted therapy hinges on pathogen-specific diagnostics (e.g., culture and susceptibility testing) to align antibiotics with the causative microorganism, minimizing unnecessary exposure. Strict adherence to evidence-based treatment durations and dosages—tailored to the animal’s age, weight, and health status—prevents underdosing (risk of relapse/resistance) and overdosing (toxicity/resistance). Regular monitoring ensures adaptive adjustments, balancing efficacy with safety. Together, these strategies form a cohesive framework to optimize antimicrobial use, safeguard animal and public health, and mitigate AMR proliferation.

5.2. Strengthen the Supervision and Education of Veterinary Drugs

Combating VDRs demands a holistic approach integrating education, governance, and technology. Governments, industry associations, and environmental organizations must utilize both modern platforms (e.g., social media, online tools) and traditional outreach (e.g., village bulletins, training workshops) to raise awareness among farmers about the ecological and health risks linked to antibiotic misuse and poor livestock waste management. Educational initiatives should emphasize shifting from reactive “end-of-pipe” practices to proactive strategies that combine “source prevention, process control, and waste treatment,” supported by technologies like bio-fermentation beds, organic fertilizer systems, and biogas plants to harmonize productivity with environmental sustainability (Shao et al., 2021).

Governments play a central role in strengthening regulatory frameworks through digitized oversight systems, including online prescription platforms, electronic antibiotic logs, and withdrawal-period monitoring tools to ensure compliance. Capacity-building efforts, such as cooperative-led training programs, are essential to equip farmers with scientific disease management skills, responsible antibiotic use, and withdrawal protocols (Shao et al., 2021). Preventive measures like expanding mandatory vaccination coverage and subsidizing biosecurity tools (e.g., disinfectants) can further reduce reliance on antibiotics. Simultaneously, strict audits of veterinary drug and feed manufacturers, coupled with tracking antibiotic production, sales, and on-farm usage, are critical to curb non-compliant practices and evaluate resistance trends (Werner et al., 2018).

Enhancing farmers’ risk perception and incentivizing participation in traceability systems are pivotal to curbing antibiotic overuse. By synergizing education, policy enforcement, technological innovation, and data-driven regulation, stakeholders can effectively minimize drug residues, safeguard public health, and advance sustainable livestock production (Cabello et al., 2016).

5.3. Develop Alternative Varieties of Antibiotics

The rise of AMR in pathogenic bacteria poses a critical global public health threat. Addressing this crisis requires reducing antimicrobial use in agriculture. Current efforts to replace conventional antibiotics focus on identifying eco-friendly alternatives that offer lower resistance risks alongside performance-enhancing benefits. Leading candidates include probiotics, Phage, organic acids, antimicrobial peptides, botanical extracts, nanoparticles, and antibodies (Abs)(

Table 1). These innovations aim to balance sustainable livestock productivity with reduced AMR progression, aligning with global health and environmental priorities.

5.3.1. Probiotics

Probiotics have arisen as potential substitutes for AGPs on account of their distinctive mechanisms of action, such as regulating the number of microorganisms in the intestinal microbiome and pathogen colonization, enhancing animal growth performance, and intestinal health. The administration of live probiotic microorganisms intravenously may contribute to increasing intestinal microbial diversity, facilitating the growth of beneficial bacteria, eliminating pathogens, modulating immune function, and detoxifying. Furthermore, probiotics can ameliorate intestinal-related functions, like promoting the secretion of digestive enzymes, nutrient absorption, and the generation of short-chain fatty acids, thereby elevating growth performance and feed conversion efficiency (Hussain et al., 2024). Kang et al. (Kang et al., 2024) carried out in vivo and in vitro antagonistic activities of two probiotic strains and grapefruit seed extract against Clostridium difficile. They demonstrated that GSE and these two novel probiotics can act as alternative therapeutic approaches for alleviating Clostridium difficile infection by regulating the intestinal microbiome.

5.3.2. Phage

Upon attachment to its bacterial host, a phage injects its genetic material into the bacterial cell and exploits the bacterial replication system to produce new phage particles. This sequence of events is known as the lytic cycle, which concludes with the lysis or bursting of the bacterial cell, simultaneously freeing new phages that can infect additional bacteria. The capacity of phages to self-multiply in the infected area constitutes a distinct advantage, as it might diminish the necessity for repetitive treatments. The specificity of phages in therapeutic applications brings forth both benefits and challenges. On one hand, phages can precisely target pathogenic bacteria, thereby avoiding harm to beneficial bacteria and reducing interference with the host microbiome. Nevertheless, this specificity implies that we must possess a comprehensive understanding of the bacterial pathogens to select the appropriate phages for treatment, which renders the treatment process more intricate than that of traditional broad-spectrum antibiotics (Olawade et al., 2024). Molendijk et al. (Molendijk et al., 2024) compared the effects of phages and the reference antibiotic (fusidic acid) in treating burn wound infections. They discovered that phage therapy exhibited potential superiority over antibiotics in treating burn wound infections, particularly during the treatment phase.

5.3.3. Organic Acids

Given their advantages of being non-polluting, non-resistant to antibiotics, and leaving no residues, the European Union allows the use of acidifiers or organic acids (OAs) and their salts in poultry farming. Incorporating OAs into poultry diets aids in the production of prebiotics and probiotic lactic acid bacteria. OAs can serve as alternatives to AGPs, positively impacting the production efficiency and intestinal health of livestock and poultry. By supplementing OAs, one can improve growth performance indicators and carcass characteristics, lower intestinal pH, increase the production of gastric protease, enhance the digestion and absorption of nutrients, stimulate immune responses, and suppress the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria (Abd El-Ghany, 2024). Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2018) demonstrated that the combination of OAs and medium-chain fatty acids exhibits significant antibacterial effects and alleviates early weaning diarrhea in piglets by regulating intestinal microbiota and strengthening the intestinal barrier function.

5.3.4. Antimicrobial Peptide

AMPs encompass host defence peptides that originate from the innate immune systems of diverse living organisms, such as animals, plants, bacteria, and fungi. These peptides can exhibit their antimicrobial activities through various mechanisms. They can disrupt the cell walls and membranes of bacteria, act intracellularly, combine dual destruction mechanisms, and inhibit the formation of biofilms (Jasminka et al., 2022). In this investigation, Xia et al. (Xia et al., 2024) conducted a zebrafish culture experiment in which zebrafish were fed diets enriched with AMP or antibiotics, aiming to assess the impact of these interventions on the microbiome and antibiotic resistance profiles of zebrafish intestinal samples. The findings revealed that the absolute abundance of ARGs was lower in the AMP-treated group compared to the antibiotic-treated group.

5.3.5. Botanical Extracts

Chinese herbs boast a wide array of sources, are relatively inexpensive, possess low toxicity and side effects, and are abundant in saponins, proteins, amino acids, mineral elements, vitamins, as well as polysaccharides, flavonoids, alkaloids, organic acids, and volatile oils. These properties can facilitate the growth and development of animals and enhance their production performance. Compared with traditional antibiotics, natural herbal extracts exhibit broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and low resistance. Dietary supplementation with Achyranthes japonica extract demonstrates dose-dependent enhancements in broiler production parameters, including an increase in growth performance indices, an improvement in total tract nutrient digestibility, modulation of the cecal microbiota profile, a reduction in excreted ammonia emissions, and a decrease in abdominal adipose deposition compared to the control group (Park & Kim, 2020). W. Bendowski et al.(Bendowski et al., 2022) reported that Silybum marianum supplementation in broilers reduced footpad lesion incidence, enhanced welfare and production metrics, and improved breast muscle physicochemical properties. Elevated enzymatic activity and antioxidant potential were also observed in serum and muscles compared to controls.

5.3.6. Nanoparticles

Nanotechnology, as an emergent science, is extensively employed in diverse research domains, encompassing medicine, and has conferred substantial benefits. For instance, metal nanoparticles such as silver (Ag), gold (Au), silver oxide (Ag₂O), zinc oxide (ZnO), titanium dioxide (TiO₂), calcium oxide (CaO), copper oxide (CuO), and magnesium oxide (MgO) have manifested considerable potential in the antibacterial field (Abayeneh, 2023). Concerning the antibacterial mechanisms of these metal nanoparticles, current research has disclosed several potential pathways. These mechanisms comprise but are not restricted to: direct impairment of nucleic acids, destruction of cell walls and cell membranes through the formation of pits and holes, perturbation of normal cell structure and function, initiation of protein oxidation, interruption of the electron transfer process, inhibition of cell division, promotion of the formation of reactive oxygen species, leading to enzyme degradation or inhibition, inactivation or leakage of cellular substances, and disruption of flagella, cell integrity, and extracellular matrix, etc. (Abayeneh, 2023). For example, Raza et al. (Raza et al., 2024) assessed the potential of zinc oxide and copper oxide nanoparticles as substitutes for florfenicol in the treatment of avian cholera.

5.3.7. Antibody

Abs, primarily generated in mammals, present valuable alternative therapeutic strategies for treating bacterial infections. They can either directly bind to the bacterial surface or indirectly counteract the toxins and virulence factors that contribute to such infections. The research was conducted by El-Kafrawy. et al. (El-Kafrawy et al., 2023) have discovered that the utilization of albumin IgY Abs produced by immunized chickens can effectively treat bacterial infections in both animals and humans. Emelianova et al. (Emelianova et al., 2022) utilized high-dilution specific Abs in conjunction with antibiotics, resulting in a significant improvement in the survival rate of mice infected with pneumonia-inducing Klebsiella pneumonia. The effectiveness of this combination was comparable to that of the reference drug Gentamicin. Furthermore, high-dilution Abs also enhanced the in vitro antibacterial activity of antibiotics against resistant strains of Klebsiella pneumonia.

6. Food Safety Assurance Measures

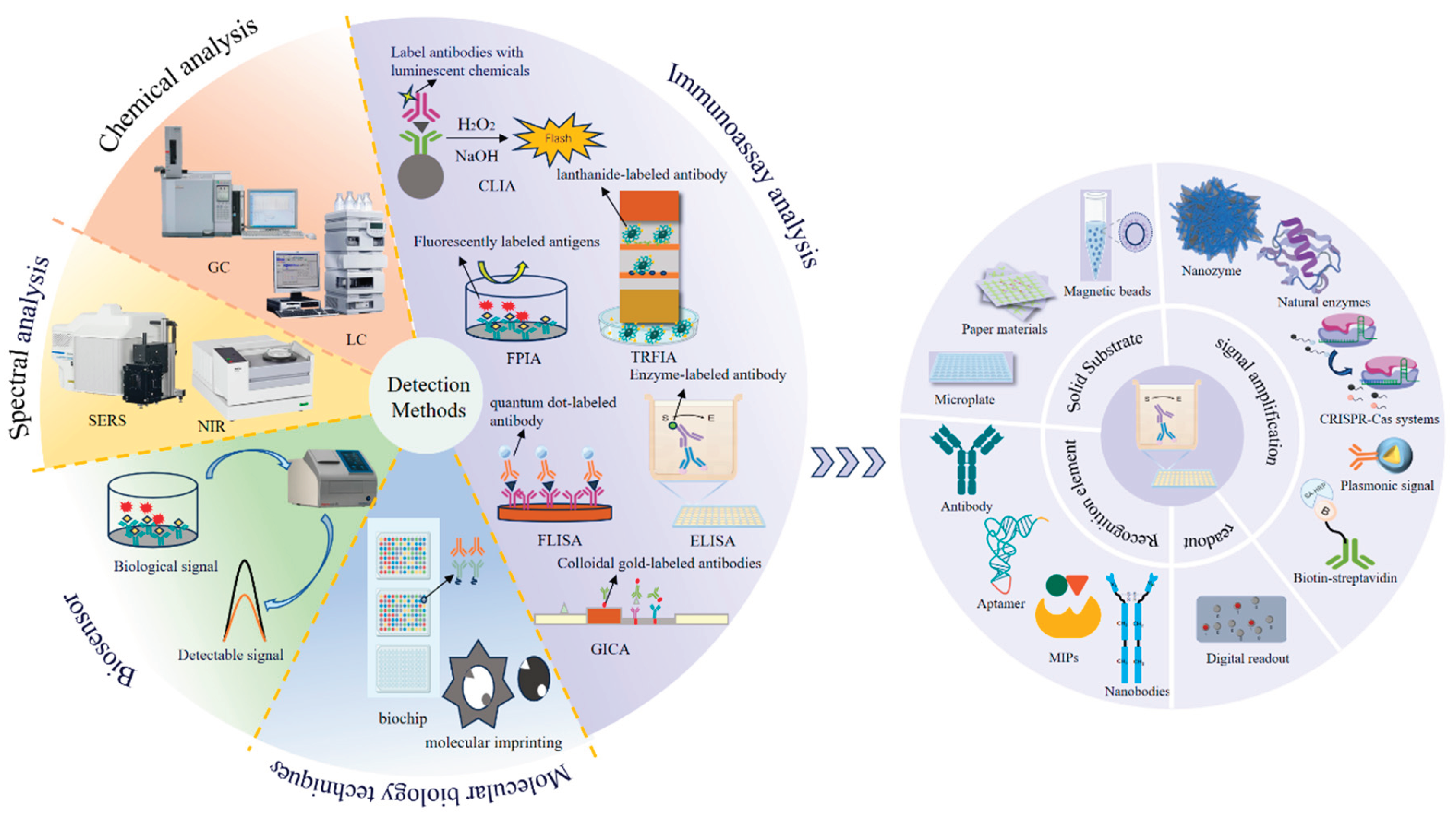

The controlled use of veterinary pharmaceuticals in modern animal husbandry serves dual purposes: effectively preventing and treating livestock diseases while improving productivity metrics. However, this practice inevitably results in persistent drug residues within the food chain, creating significant public health risks through bioaccumulation and chronic exposure pathways. Precise identification and quantification of residual compounds – including antibiotics, antiparasitics, and growth promoters – in meat, eggs, dairy products, and related items necessitate continuous advancements in analytical methodologies. The development of detection platforms emphasizing operational efficiency, analytical sensitivity, methodological accuracy, and user accessibility has become paramount for ensuring food safety and protecting consumer health. Concurrent with escalating global food safety regulations, the field of veterinary drug analysis has witnessed transformative innovations. Emerging detection systems, building upon conventional chromatographic and immunological techniques, now integrate nanotechnology-based biosensors, high-resolution mass spectrometry, biochip technology, etc. (

Table 2) (

Figure 3), collectively redefining residue monitoring capabilities.

6.1. Chemical Analysis Method

6.1.1. Gas Chromatography

Gas chromatography (GC) is primarily employed for the detection and analysis of volatile or semi-volatile organic compounds. In GC, the sample is introduced into the heated vaporization chamber via an injector, and the components of the sample are vaporized and conveyed by the carrier gas. The separation of diverse components is accomplished through the separation effect of the chromatography column, and the detection signal is obtained at the detector. GC boasts the advantages of high separation efficiency, high sensitivity, and rapid analysis speed, and is frequently utilized to detect residues of pesticides and volatile organic pollutants. The detectors linked to GC mainly encompass nitrogen-phosphorus detectors, electron capture detectors, and mass spectrometry detectors. Shuyu et al. (Shuyu et al., 2023) developed an innovative column-pre-treatment derivatization gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS) technique for the precise determination of decoquinate residues in chicken tissue. Before the derivatization step, the polar functional groups within the compound structure were eliminated by hydrogenation reduction, which not only decreased the molecular weight but also effectively enhanced the volatility of decoquinate, creating favourable conditions for the subsequent chromatographic analysis.

6.1.2. Liquid Chromatography

Liquid chromatography (LC) and its advanced derivatives, including high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC), are widely employed for detecting non-volatile or thermally labile compounds. These techniques separate sample components under high-pressure column conditions through differential partitioning between mobile and stationary phases, offering high throughput, sensitivity, and specificity for VDR analysis. The integration of UHPLC with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) further enhances analytical capabilities by combining chromatographic resolution with mass spectrometry’s selectivity, enabling rapid identification of residues, metabolites, and derivatives in complex matrices. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) platforms, such as quadrupole-linear ion trap (Q-LIT) and orbitrap-based systems, provide unparalleled mass accuracy (<1 ppm) and resolution (>100,000 FWHM), facilitating non-targeted screening and structural elucidation of veterinary drugs. This capability is demonstrated by Vardali et al. (Vardali et al., 2018), who utilized ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-QTOF-MS) to analyze 20 VDRs (tetracyclines, quinolones, sulfonamides) in European seabass tissues. Similarly, Lu et al. (Lu et al., 2021) established a PRiME extraction workflow coupled with UHPLC-Q-LIT/electrostatic field orbitrap HRMS for multi-class detection (sulfonamides, β-lactams, macrolides) in sheep milk.

6.2. Immunological Technique

Immunological analysis is a form of biochemical analysis that exploits the specific binding reaction between antigens and Abs. It typically exhibits high selectivity and low detection limits and is extensively employed for the determination of various antigens, semi-antigens, or Abs. It is generally classified into several methods, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), colloidal gold immunoassay (CGIA), chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA), fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA), quantum dot fluorescence immunoassay (FLISA), and time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay (TRFIA).

6.2.1. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

ELISA is a widely used diagnostic technique that detects and quantifies target molecules through the specific binding of Abs and antigens. Traditional ELISA employs microplates as solid substrates and Abs as recognition elements, but its limitations—such as operational complexity, high costs, and limited sensitivity—have driven innovations in its four core components: solid substrates, recognition elements, signal amplification systems, and readout methods (

Figure 3) (Ping et al., 2022).

To improve portability and analytical efficiency, paper-based analytical devices and magnetic bead (MB) systems have emerged as viable alternatives to conventional microplate platforms. A notable example is the nanofiber membrane-integrated paper-based ELISA system, which facilitates rapid visual identification of trace CAP through enhanced capillary action (Zhao et al., 2020). Concurrently, MB-based platforms exhibit superior reaction kinetics owing to their high surface-to-volume ratio, enabling efficient biomolecular interactions. The implementation of small test tube formats provides additional advantages: their expanded reaction chambers not only accommodate greater sample and reagent volumes for improved detection sensitivity but also serve as integrated optical cuvettes for direct spectrophotometric measurement of colorimetric signals, thereby eliminating transfer steps and minimizing potential contamination risks (Ping et al., 2022).

Recognition elements have expanded beyond traditional Abs. Aptamers, with their low cost and stability, achieve quantitative CAP detection in fish at 16 pg/mL (Zhiwei et al., 2024). Nanobodies, derived from camelid Abs, combine high stability and sensitivity, such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled nanobodies detecting ENR in milk at 6.48 ng/mL (Yang et al., 2025). Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), synthetic Ab mimics, offer robustness and cost-effectiveness, even outperforming natural Abs in some applications (Smolinska-Kempisty et al., 2016).

Signal amplification systems have evolved to address the limitations of natural enzymes like HRP. Nanocatalysts (e.g., Au-Pt/SiO₂ nanoparticles), CRISPR-Cas systems, biotin-streptavidin complexes, and plasmonic resonance strategies enhance sensitivity and reduce reliance on unstable enzymes under extreme conditions. Readout methods have shifted from analog to digital approaches. Digital ELISA partitions samples into tens of thousands of microreactors for single-molecule counting, achieving 1,000-fold higher sensitivity than traditional methods (Akama et al., 2019). However, its application to small molecules (e.g., haptens) remains unreported (Akama et al., 2019; Ping et al., 2022).

These advancements—including portable substrates, stable recognition elements, novel amplification strategies, and digital readouts—address the limitations of conventional ELISA and expand its utility in resource-limited settings and veterinary drug monitoring. Nevertheless, challenges persist in adapting digital ELISA for small-molecule detection, underscoring the need for continued innovation (Ping et al., 2022).

6.2.2. Colloidal Gold Immunoassay Assay

Employing colloidal gold (where gold chloride is reduced and polymerized to form gold particles of specific sizes) as a tracer, it is combined with macromolecular substances such as proteins and detected through immune reactions. This technology, aside from its facile operation, rapid response, and short time consumption, also possesses the merits of low cost and high specificity, being particularly suitable for field detection. Haiping et al. (Haiping et al., 2023) employed CGIA to achieve rapid, on-site, and semi-quantitative detection of Tetracycline (TC) in seawater. They achieved a visible limit of detection (vLOD) of TC in seawater at 20 µg L⁻1, with results observable by the naked eye within 10 minutes. This method remains unaffected by variations in sea temperature, pH value, and salinity. Additionally, Hong et al. (Hong et al., 2022) created a colloidal gold immunoassay strip for detecting pirimiphos-methyl in agricultural products and the environment. Their strip exhibited excellent performance, accurately identifying positive samples. The detection limit was set at 30 μg/kg, and the average recovery rate of pirimiphos-methyl in spiked samples ranged between 80.4% and 110.5%.

6.2.3. Chemiluminescence Immunoassay Assay

CLIA technology integrates high-sensitivity chemical luminescence detection with highly specific immune reactions. The primary principle of this technology lies in marking the chemical luminescence substance on the antigen (or Ab) or acting on the chemical luminescence substrate with enzymes. Under catalytic and oxidative actions, the chemical luminescence substance is excited from the ground state to the excited state, which is unstable. The luminescence substance then reverts to the ground state and releases photons. Since the intensity of the light signal is linearly correlated with the concentration of the analyte within a certain range, an optical detection system can be employed to quantitatively detect the light signal and determine the content of the analyte. Wu et al. (Wu et al., 2011) designed a chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA) for the quantitative measurement of sulfamethoxazole. This method had a detection limit of 3.2 pg/mL, a linear range of 10 to 2000 pg/ml, intra-day and inter-day precisions below 13% and 18% respectively, and a recovery rate ranging from 85% to 105%. Furthermore, Yu et al. (Yu et al., 2014) introduced a CLEIA based on the HRP-luminol-hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) chemical luminescence system for the high-sensitivity detection of ENR. When compared to ELISA and HPLC, CLEIA demonstrated significant advantages, enabling high-throughput and real-time detection.

6.2.4. Fluorescence Polarization Immunoassay Assay

FPIA is a relatively mature quantitative immunoassay technique. In a solution, a known concentration of fluorescently labeled antigen and the target (antigen) compete for binding with a certain amount of Ab. The fluorescently labeled antigen molecules are small and rotate rapidly, resulting in low fluorescence polarization intensity. However, when the labeled antigen binds to the Ab to form an antigen-Ab complex, it rotates slowly, causing high fluorescence polarization intensity. In the competitive process, the more target molecules there are, the more they bind to the Ab, and the less the Ab binds to the labeled antigen, leading to lower fluorescence polarization intensity. By utilizing the relationship between the labeled antigen and the fluorescence polarization intensity, the number of target molecules in the solution can be calculated. Liuchuan et al. (Liuchuan et al., 2021) created nine tracers by linking various haptens with fluorescein. These tracers were then matched with four monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and the optimal tracer-mAb pair was selected to establish a high-sensitivity FPIA for detecting amantadine in chicken meat. During actual testing of chicken meat samples, the detection limit was found to be 0.9 μg/kg, with a recovery rate ranging from 76.5% to 89.3%. Dong et al. (Dong et al., 2019) synthesized ten fluorescently labeled Ractopamine (RAC) derivatives, known as tracers, and developed a rapid FPIA for detecting RAC in pork using a polyclonal Ab specifically prepared for RAC. The detection limit of this method was 0.56 μg/kg, and the recovery rate ranged from 74.8% to 86.6%.

6.2.5. Fluorescence Immunoassay Assay

Quantum dots, abbreviated as QDs, are semiconductor quantum dot nanocrystals with dimensions ranging from 1 to 10 nm. They possess advantages such as colour tunability, low photobleaching, intense fluorescence, a narrow emission spectrum, and a wide excitation spectrum, thus rendering them promising fluorescent probes. Through the combination of quantum dots with immunoanalytical techniques, the signal can be amplified, leading to high sensitivity, and they have been widely applied in the fields of environmental and food safety. For instance, Xin et al. (Xin et al., 2024) presented a fluorescence immunoassay utilizing quantum dot fluorescence for the precise quantification of florfenicol residues in animal-derived food and feed. This method exhibited exceptional sensitivity, with a detection limit of 0.3 ng/mL and a quantitative range spanning from 0.6 to 30.4 ng/mL. In a separate study, Erqun et al. (Song et al., 2015) integrated a multi-colour QD-based immunofluorescence technique with an array analysis method to facilitate simultaneous, sensitive, and visual detection of SM, TC, and penicillin G (PC-G) in milk.

6.2.6. Time-Resolved Fluoro Immunoassay Assay

TRFIA technology is a marker immunoassay technique that emerged in the 1980s. It utilizes lanthanide elements to label antigens or Abs and measures fluorescence by employing time-resolved technology based on the luminescence characteristics of lanthanide chelate complexes. Through the detection of both wavelength and time parameters, effective signal discrimination can be accomplished to eliminate non-specific fluorescence interference, thereby significantly enhancing the analytical sensitivity. The attention it has received in the field of VDR detection has been escalating year by year. A strip test based on time-resolved fluorescent microsphere immune probes (TRFMs-LFIA) has been developed for the simultaneous detection of ceftiofur (CEF) and its metabolite desfuroylceftiofur, with LOD of 0.97 ng/mL and 0.41 ng/mL, respectively, and IC50 of 12.92 ng/mL and 12.58 ng/mL, respectively (Shuxian Li et al., 2024).

6.3. Spectrum Technology

Spectral technology utilizes the characteristic features of emission, absorption, or scattering spectral series of various chemical substances to detect and identify them. It is highly sensitive, easy to use, and requires no laboratory environment to realise high-efficiency and high-precision online detection. The applications of spectral technology in the detection of VDRs primarily encompass surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS).

6.3.1. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy serves as a non-destructive analytical method that enables the examination of a sample's chemical composition, phase and morphological characteristics, crystallinity, and intermolecular interactions. It can rapidly and quantitatively analyze the components of diverse substances. In surface-enhanced Raman scattering, when target molecules adsorb onto solid substrates featuring metal nanostructures on the surface or onto metal nanoparticles such as gold and silver, the plasmon resonance effect of the metal surface can significantly enhance the Raman scattering signal of the molecules, with a strength that can be enhanced by 10^6 to 10^15 times in comparison to normal Raman spectra. It is capable of quantitatively identifying ultra-low concentration molecules in complex biological mixtures and providing comprehensive information. The sensitivity can reach the level of single molecules, facilitating rapid and non-destructive analysis of trace and ultratrace samples. Gao et al. (Gao et al., 2025) developed a solid-phase extraction - SERS approach for detecting multiple antibiotic residues in dairy products. This method offers high sensitivity and throughput for identifying sodium tetracycline, sulfapyridine, and benzathine penicillin, with detection limits as low as 2.237, 2.644, and 4.662 ppb, respectively. In another study, Shuai et al. (Shuai et al., 2022) utilized SERS in conjunction with spectral pretreatment techniques to detect nitrofurantoin in honey. By refining the experimental process and enhancing the spectral calibration method, they achieved a minimum detection limit of 0.1321 mg/kg for nitrofurantoin.

6.3.2. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

NIRS is a significant analytical technique having a wavelength range between visible light and mid-infrared spectra, typically delineated as 780 nm to 2500 nm. This spectral domain primarily registers the vibrational information of hydrogen-containing groups (such as C-H, O-H, and N-H), thereby rendering NIRS highly sensitive and precise for the analysis of organic compounds and biomolecules. Presently, NIRS has been applied and promoted in diverse analytical fields due to its technical merits of rapid analysis speed, high detection efficiency, excellent test reproducibility, and non-destructive sampling. It can not only circumvent the problems of complex operation and environmental pollution in the sample pretreatment process of conventional detection, but also satisfy different detection requirements, such as on-site detection and multi-parameter simultaneous detection. Conceicao et al. (Conceição et al., 2018) applied Fourier transform NIRS to identify antibiotic residues in milk, successfully differentiating various antibiotics dissolved therein. Meanwhile, Wu et al. (Wu et al., 2018) utilized NIRS alongside partial least squares regression to detect tetracycline residues in milk, achieving a sensitivity of 5 micrograms per litre, with a data model correlation coefficient exceeding 0.89.

6.4. Biosensor Technology

Biosensors typically consist of a recognition element (or receptor) and a transducer element. A biosensor is generally comprised of a recognition element (or receptor) and a transducer element. It is a specialized device that employs a biological sensing unit, relying on component recognition, to convert recognizable biological signals into detectable electrical, optical, acoustic, or thermal signals through appropriate energy conversion principles. Additionally, it adopts suitable techniques to ensure high selectivity during signal amplification for the target object. Owing to their strong specificity, rapid analysis speed, high precision, low cost, portability, and flexibility, biosensors are extensively utilized. Depending on the type of transducer element used, biosensors can be classified into electrochemical, semiconductor, optical, thermistor, and piezoelectric biosensors, which are applicable for analysing indicators such as toxic and harmful substances, food components, food additives, and food freshness (Ma et al., 2021). Peng et al. (Peng et al., 2018) developed a multiplexed lateral flow immunoassay, termed the AuNCs-MLFIA sensor, utilizing highly luminescent green gold nanoclusters. This sensor can detect samples without prior treatment in just 18 minutes. Furthermore, the AuNCs-MLFIA sensor can be integrated with a portable fluorescence reader for quantitative detection. The IC50s for clenbuterol and RAC were 0.06 and 0.32 μg/L, respectively, with detection limits of 0.003 and 0.023 μg/L. Zhang and his team (Zhang et al., 2016) crafted a highly sensitive amperometric immunosensor by integrating zinc sulphide quantum dots (ZnSQDs) and polyaniline nanocomposites with gold electrodes and clenbuterol Abs. This biosensor exhibited a remarkable detection limit of 5.5 pg/mL at an operating potential of 0.21 V versus Ag/AgCl.

6.5. Molecular Biological Technique

As traditional analytical techniques such as chromatography and mass spectrometry continue to evolve, molecular biology techniques are being increasingly employed in food testing. They are playing an ever more significant role in the detection of pesticides and VDRs, the identification of genetically modified products, the detection of allergens, and the discrimination of pathogenic microorganisms. Among the molecular biology techniques utilized in the domain of VDR detection are biological chip technology and molecular imprinting technology.

6.5.1. Biochip Technology

Biosensor technology leverages the specific interactions between biomolecules to construct a miniaturized biochemical analysis system. By employing microfabrication and microelectronics techniques, it achieves the high-density immobilization of DNA, antigens, Abs, cells, or tissues onto a solid-phase carrier, thereby forming a dense two-dimensional molecular array. The integration of biochemical analyses on a single chip surface enables swift, precise, and high-throughput detection of target biomolecules. Song et al. (Song et al., 2022) designed a paper-based microfluidic chip that incorporates a boronate-affinity metal-organic framework and molecularly imprinted polymer for the swift detection of hazardous veterinary drugs in food. The chip utilizes a uniform zeolite-8 membrane framework as both the support and enrichment layer, employing a highly targeted boronate-affinity surface imprinting technique to develop the recognition layer. The detection of antibiotic residues, such as kanamycin, was accomplished through liquid flow channels, with high specificity and visualization. The entire analysis process is rapid and efficient and can be completed within 30 minutes. Mi-Sun et al. (Mi-Sun et al., 2016) developed a simple and sensitive method for the detection of ENR. The method immobilized a monoclonal Ab specific to ENR on the chip and covalently bound fluorescent microspheres to ENR molecules. Based on the principle of competitive binding between the ENR in the solution and the ENR fixed on the microspheres (ENR MPs), high dynamic range detection of ENR was achieved.

6.5.2. Molecular Imprinting Technique

Molecular imprinting technology is a technique that generates MIPs with complementary size, shape, and functional groups to a template molecule, customizing the binding sites. MIPs possess a specific spatial arrangement, and the polymers not only recognise the size and shape of molecules but also form covalent or non-covalent bonds with the target molecule to attain specific binding capabilities. Molecular imprinting is also referred to as "biosynthetic Abs." Chemically produced MIPs outperform Abs in terms of specific adsorption of target materials, simplicity in production and preparation, short cycle, low cost, mild storage conditions, and material stability (resistance to high temperature, high pressure, and solvent erosion), and are extensively utilized in environmental monitoring, food analysis applications, and drug analysis. MIPs generally exhibit strong affinity, specificity, and stability, and can selectively adsorb specific compounds in complex matrix samples. The application of molecular imprinting in VDR detection mainly involves filling the solid-phase extraction tower with the filler, achieving the enrichment, purification, and separation of specific compounds. For instance, Wen et al. (Wen et al., 2024) combined MIPs with functional materials such as MOFs and COFs and expanded their application scope in sample processing. Additionally, molecular imprinting technology can be employed as a biosynthetic biosensor in VDR detection, where the analyte is combined with the recognition element to generate a chemical signal that is converted into an electrical or physical signal for molecule measurement. Recently, Zhang et al. (Zhang et al., 2025) synthesized a unique molecularly imprinted CoWO4/g-C3N4 nanomaterial through a combination of hydrothermal and electrochemical polymerization methods. This MIP-CoWO4/g-C3N4 nanocomposite serves as an innovative sensing platform for detecting furazolidone (FRZ), exhibiting a low detection limit of 2.61×10-13 mol L-1 and considerable sensitivity.

7. Conclusions

The presence of VDRs in animal-derived foods represents a critical and multifaceted challenge to global public health and food safety. Antibiotics, in particular, are the most frequently detected residues, with their misuse and overuse in animal husbandry contributing to a wide range of health risks. Human exposure to these residues occurs primarily through dietary intake, drinking water, and occupational contact, pathways that facilitate the entry of these compounds into the human body and subsequently lead to adverse health effects. These effects include acute and chronic toxicities, allergic reactions, disruptions to gastrointestinal microbiota, and the development of antibiotic resistance—a growing global health crisis. The emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance, driven by the inappropriate use of antibiotics in livestock production, not only complicates the treatment of infections but also threatens the efficacy of critical antibiotics, underscoring the urgency of addressing this issue.

Addressing this challenge demands a holistic mitigation framework. Foremost, the veterinary sector must adopt evidence-based drug stewardship, emphasizing preventive healthcare, precision diagnostics, and optimized therapeutic protocols to minimize antibiotic dependency. Concurrently, regulatory authorities should enforce stringent oversight through policy harmonization, real-time residue monitoring networks, and industry-wide education programs to curtail pharmaceutical misuse. Complementing these measures, the emergence of antibiotic alternatives—such as bacteriophage therapeutics, engineered antimicrobial peptides, and phytogenic additives—offers sustainable production models that decouple livestock productivity from chemical reliance.

Advancements in VDR detection technologies, encompassing novel materials and innovative methodologies, have significantly enhanced the precision, efficiency, and versatility of food safety monitoring. While established techniques such as GC/LC remain indispensable for complex matrix analysis, and immunological methods including ELISA and CGIA continue to enable rapid on-site screening, these conventional approaches are now being effectively augmented through integration with non-destructive analytical platforms – particularly real-time spectroscopic techniques like Raman and NIR spectroscopy. The integration of biosensors with molecularly imprinted polymers has particularly revolutionized detection paradigms through improved molecular selectivity and analytical throughput. As emerging technologies evolve toward intelligent and automated solutions, their integration with rational medication practices, robust regulatory frameworks, and alternative therapeutic strategies will be pivotal in fortifying food safety systems and safeguarding public health. This multidimensional approach ultimately promises to deliver more resilient contamination control and safer food supply chains.

In summary, we have gained a complete understanding of the sources, exposure pathways, health impacts, mitigation, and safety assurance of veterinary drug residues in the food chain. This makes us deeply realize that the residues of veterinary drugs in the food chain are a complex food safety issue that involves livestock practices, veterinary science, public policies, and consumer behavior. Although it is unrealistic to completely eliminate residues, through a sound and effective "farm to table" comprehensive management system - including strict regulation, responsible medication, continuous monitoring, and technological innovation - we can effectively control its risks, while ensuring animal health and production efficiency, and ensuring public food safety and health.

Author Contributions

Yiting Wang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Jiacan Wang: Data curation, Investigation. Linwei Zhang: Conceptualization, Data curation. Shiyun Han: Conceptualization, Data curation. Xiaoming Pan: Conceptualization, Data curation. Hao Wen: Conceptualization, Data curation. Hongfei Yang: Conceptualization, Data curation. Xu wang: Conceptualization, Data curation. Dapeng Peng: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Programs of China (2024YFF1105705, 2023YFD1301001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32373067).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations |

| 5-hydroxytryptamine ( 5-HT) |

| Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) |

| Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) |

| Antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) |

| Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) |

| Antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) |

| Antibodies (Abs) |

| Antibody (Ab) |

| Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) |

| Chemiluminescence immunoassay assay (CLIA) |

| Chloramphenicol (CAP) |

| Colloidal gold immunoassay assay (CGIA) |

| Enrofloxacin (ENR) |

| Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) |

| Fluorescence immunoassay assay (FLISA) |

| Fluorescence polarization immunoassay assay (FPIA) |

| Furazolidone (FRZ) |

| Gas chromatography (GC) |

| Groundwater (GW) |

| High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) |

| Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) |

| Liquid chromatography (LC) |

| Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) |

| Maximum Residue Limits (MRLs) |

| Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) |

| Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) |

| Multidrug resistance (MDR) |

| Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) |

| Organic acids (OAs) |

| Penicillin G (PC-G) |

| Ractopamine (RAC) |

| Streptomycin (SM) |

| Surface water (SW) |