Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Research Question | Search String |

| RQ 1: | ("food safety" OR "food hygiene") AND ("regulatory framework" OR "regulation" OR "policy" OR "legislation") AND ("small food business*" OR "small and medium enterprise*" OR "informal sector" OR "street vendor*") AND ("SADC" OR "Southern Africa" OR "South Africa" OR "Botswana" OR "Namibia" OR "Zambia" OR "Zimbabwe" OR "Mozambique" OR "Tanzania" OR "Angola" OR "Lesotho" OR "Eswatini" OR “DRC” OR “Malawi” OR “ Mauritius” OR “Seychelles” OR “Madagascar” OR “Comoros”) |

| RQ 2: |

("food safety" OR "food hygiene") AND ("compliance" OR "adherence" OR "implementation" OR "assessment") AND ("small food business*" OR "small and medium enterprise*" OR "informal sector" OR "street vendor*") AND ("SADC" OR "Southern Africa" OR "South Africa" OR "Botswana" OR "Namibia" OR "Zambia" OR "Zimbabwe" OR "Mozambique" OR "Tanzania" OR "Angola" OR "Lesotho" OR "Eswatini" OR “DRC” OR “Malawi” OR “ Mauritius” OR “Seychelles” OR “Madagascar” OR “Comoros”) |

| RQ3: | ("food safety" OR "food hygiene") AND ("regulator*" OR "authority" OR "enforcement" OR "inspection") AND ("challenge*" OR "barrier*" OR "constraint*" OR "difficulty") AND ("informal sector" OR "street vendor*" OR "small food business*") AND ("SADC" OR "Southern Africa" OR "South Africa" OR "Botswana" OR "Namibia" OR "Zambia" OR "Zimbabwe" OR "Mozambique" OR "Tanzania" OR "Angola" OR "Lesotho" OR "Eswatini" OR “DRC” OR “Malawi” OR “ Mauritius” OR “Seychelles” OR “Madagascar” OR “Comoros”) |

| RQ4: | ("best practices" OR "standard") AND ("good practice*" OR "criterion" OR "metric" OR "best guide") AND ("benchmark*" OR "best method*" OR "baseline*" OR "difficulty") AND ("informal sector" OR "street vendor*" OR "small food business*") AND ("SADC" OR "Southern Africa" OR "South Africa" OR "Botswana" OR "Namibia" OR "Zambia" OR "Zimbabwe" OR "Mozambique" OR "Tanzania" OR "Angola" OR "Lesotho" OR "Eswatini" OR “DRC” OR “Malawi” OR “ Mauritius” OR “Seychelles” OR “Madagascar” OR “Comoros”) |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Database | Scopus Google Scholar Web of Science ProQuest |

Thesis and dissertations |

| P - Population | Small food businesses (SFBs), small and medium enterprises (SMEs), or informal food sector actors such as street vendors and small processors, spaza shops, and environmental health practitioners | Exclusively on large-scale food manufacturers, multinational corporations, or formal retail chains. |

| I- Intervention | Only study that addresses food safety Regulations, Policies, Frameworks, or Interventions such as HACCP, hygiene training, and regulatory enforcement. | Solely on food quality, food security, or nutritional value, without a direct link to safety/hygiene regulations. |

| O - Outcome | Studies reporting any of these: Level of Regulatory Compliance, Challenges to Compliance, either for businesses or regulators, and effectiveness of regulatory interventions. | Opinion pieces, editorials, commentaries, or theoretical models that do not report empirical data on compliance or challenges. |

| S - Study Design | Empirical studies, Systematic Reviews for background/context only, but not for primary data extraction. | Non-research articles such as book chapters, conference abstracts without a full paper, dissertations not published in a peer-reviewed journal. |

| G - Geography | Studies conducted in one or more SADC member states: South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, etc. | Studies were conducted in non-SADC African countries like West Africa, North Africa, or outside of Africa. |

| L - Language | Articles published in English. | Articles not published in English |

| T - Timeframe | Articles published from January 2018 to the present | Articles published before January 1, 2018. |

2.1. Study Selection and Data Extraction

3. Results and Discussion

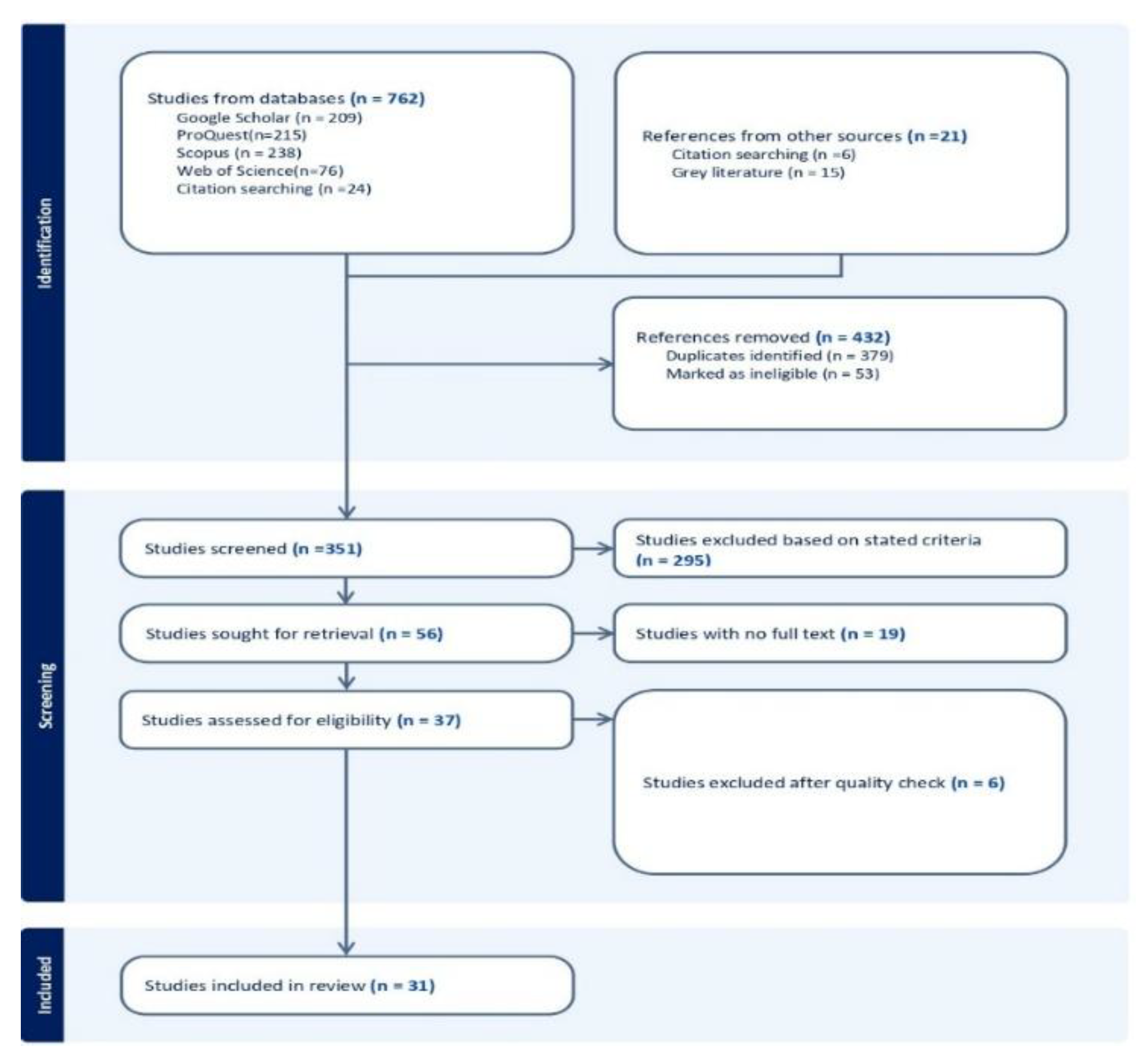

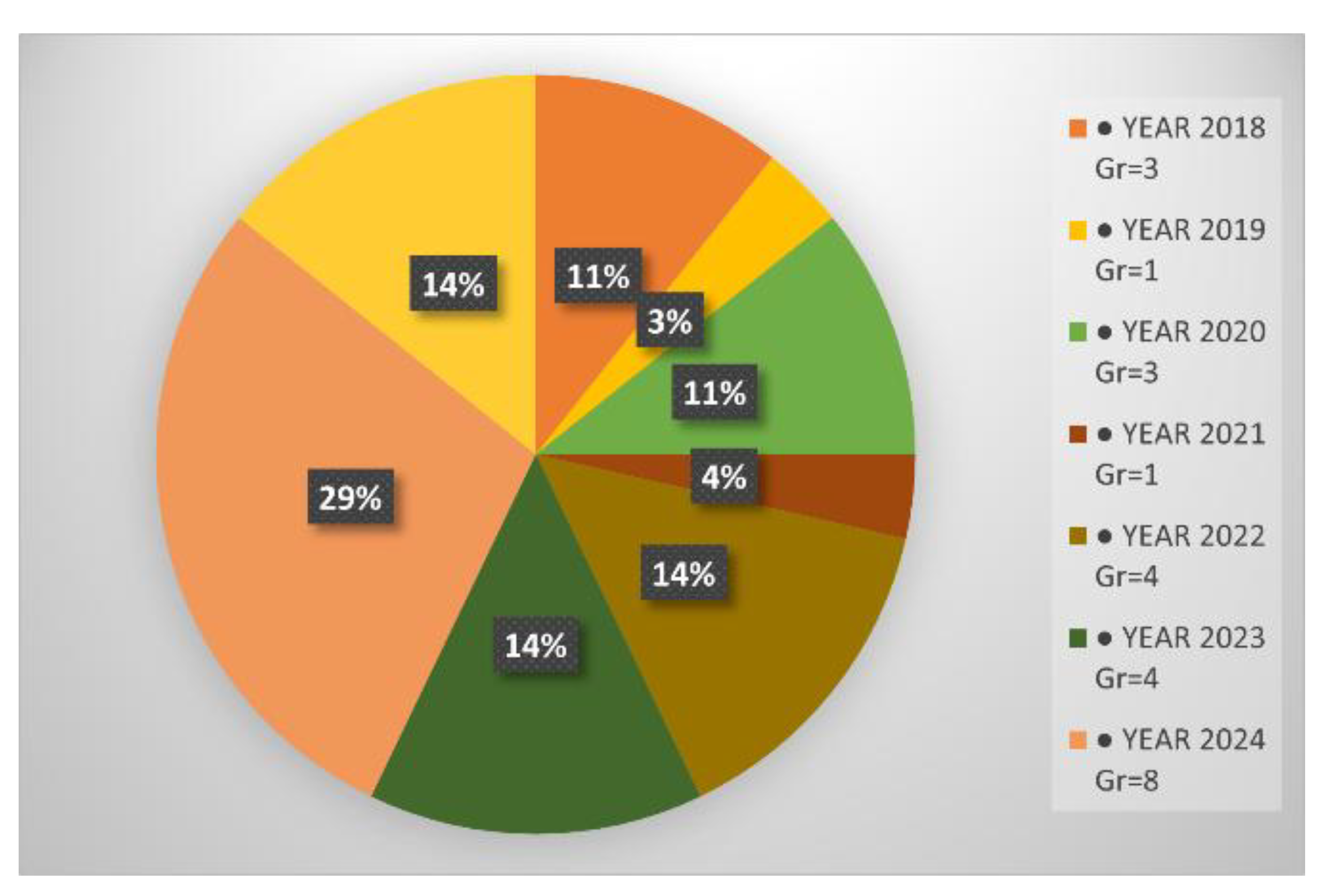

3.1. Search Result

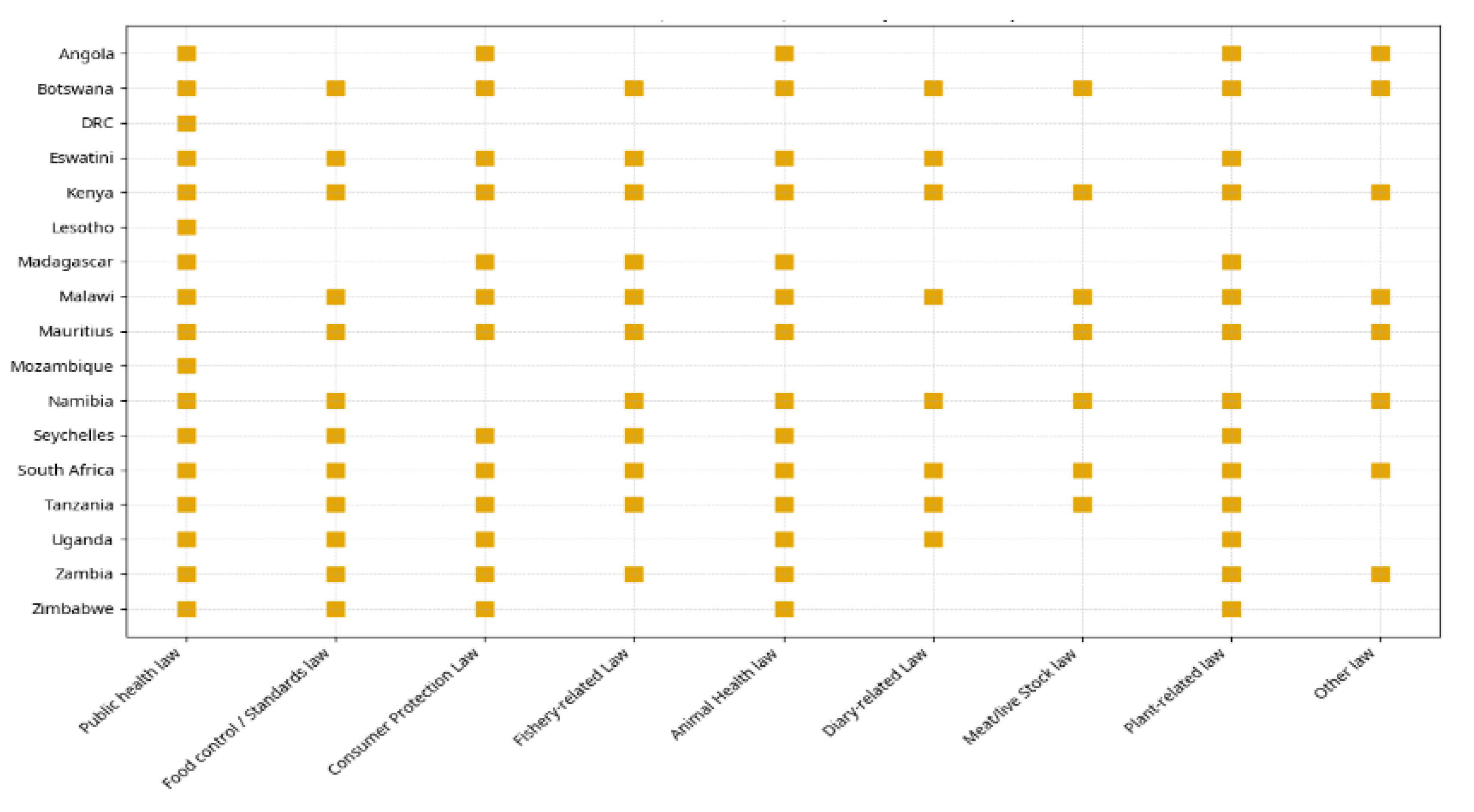

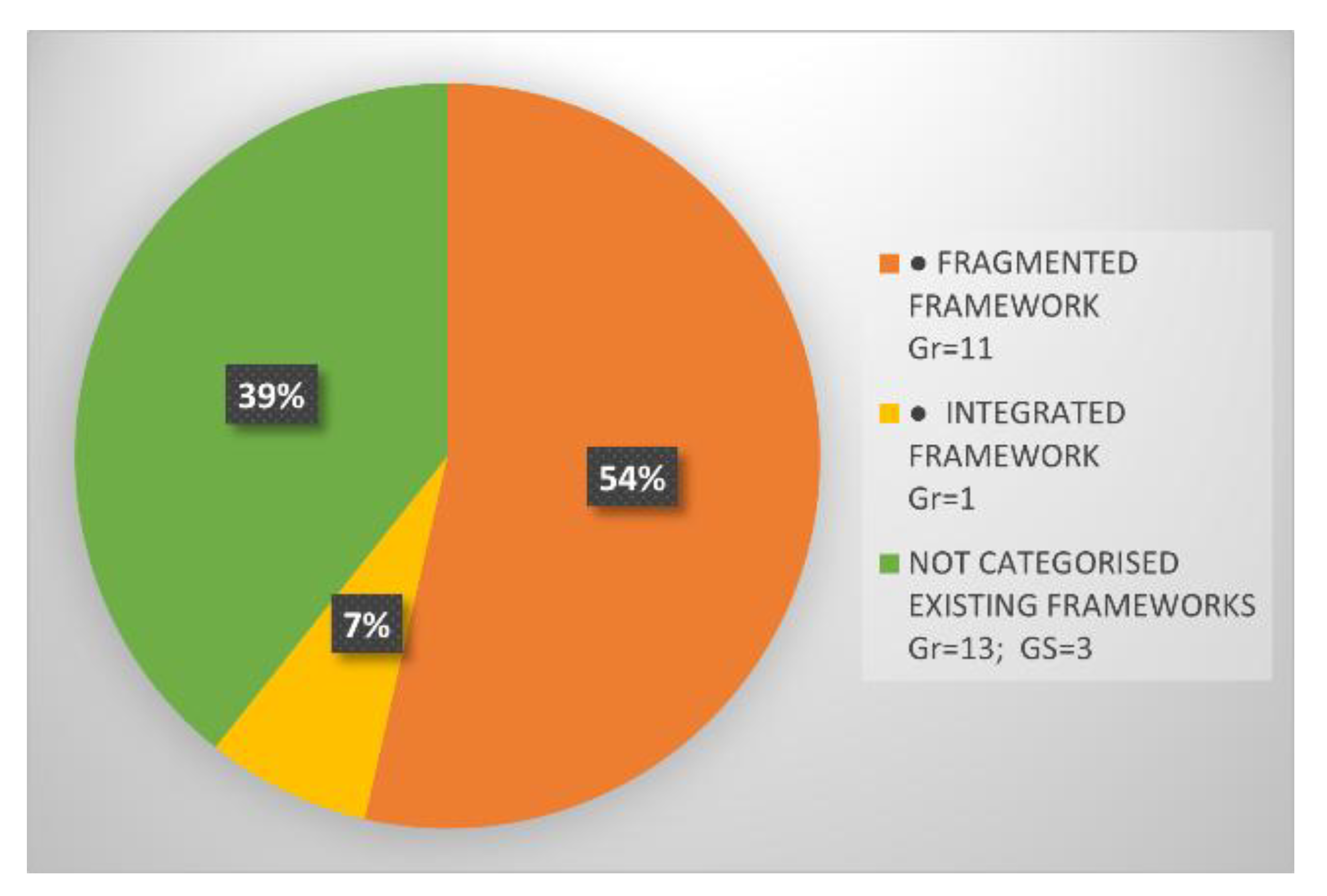

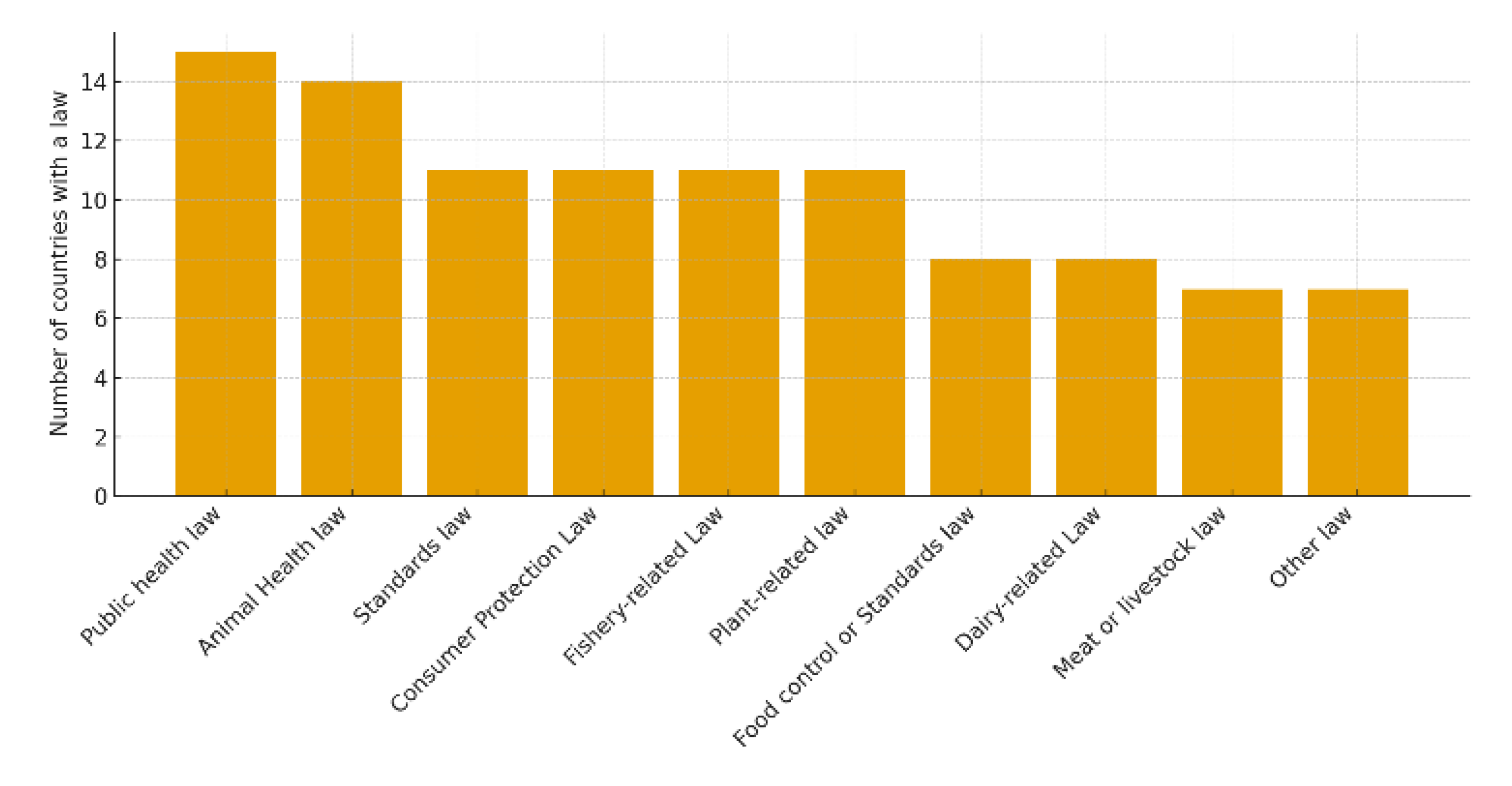

3.2. What Food Safety Regulatory Framework Exists for SFB Within the SADC States?

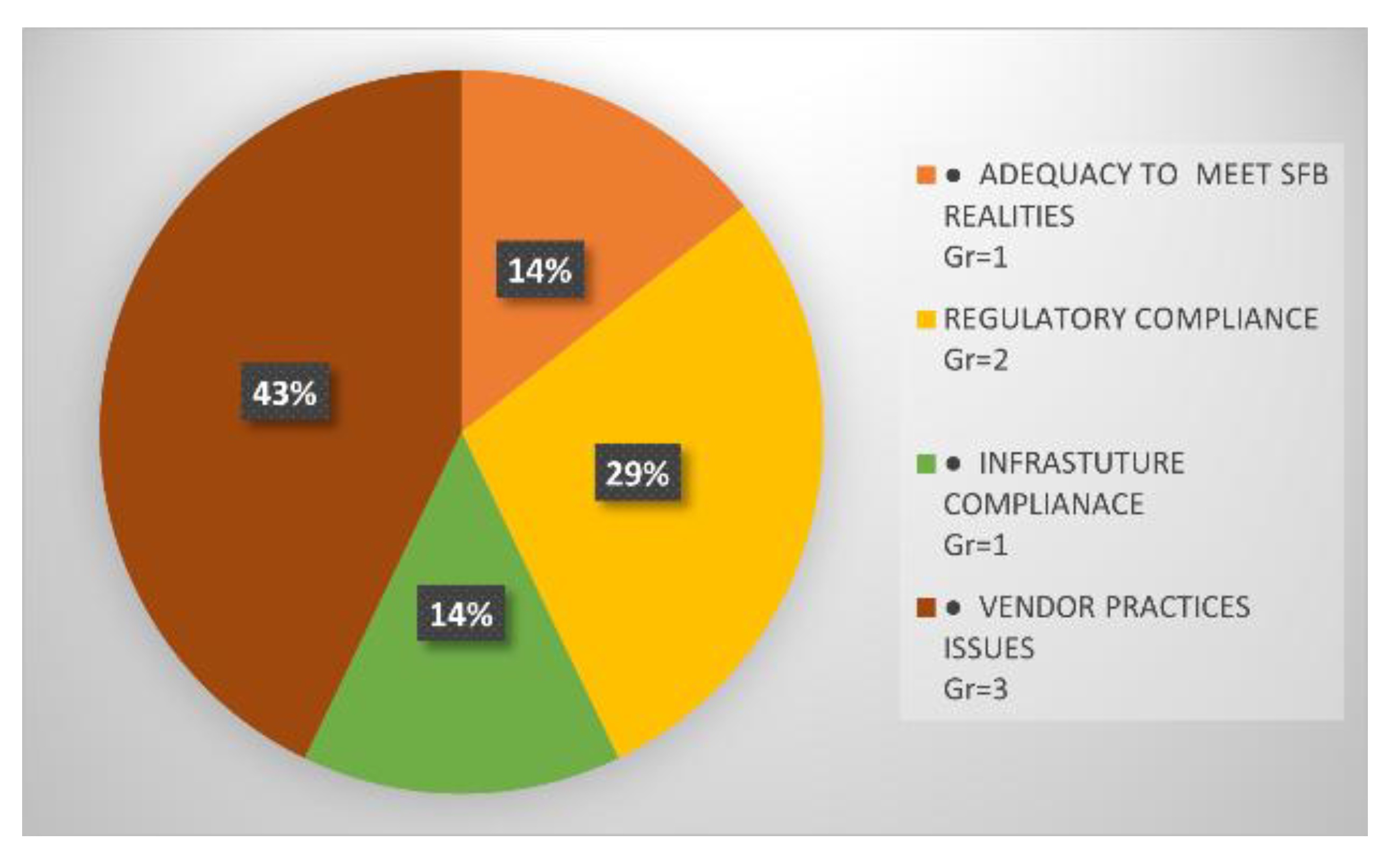

3.3. What Is the Compliance Level

3.3.1. Vendor Compliance:

3.3.2. Regulatory Compliance:

3.4. Emergence of Best Practices for Improving Food Safety Regulation in SADC.

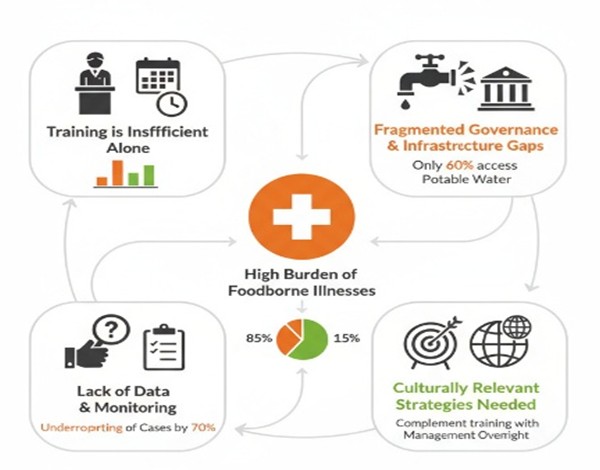

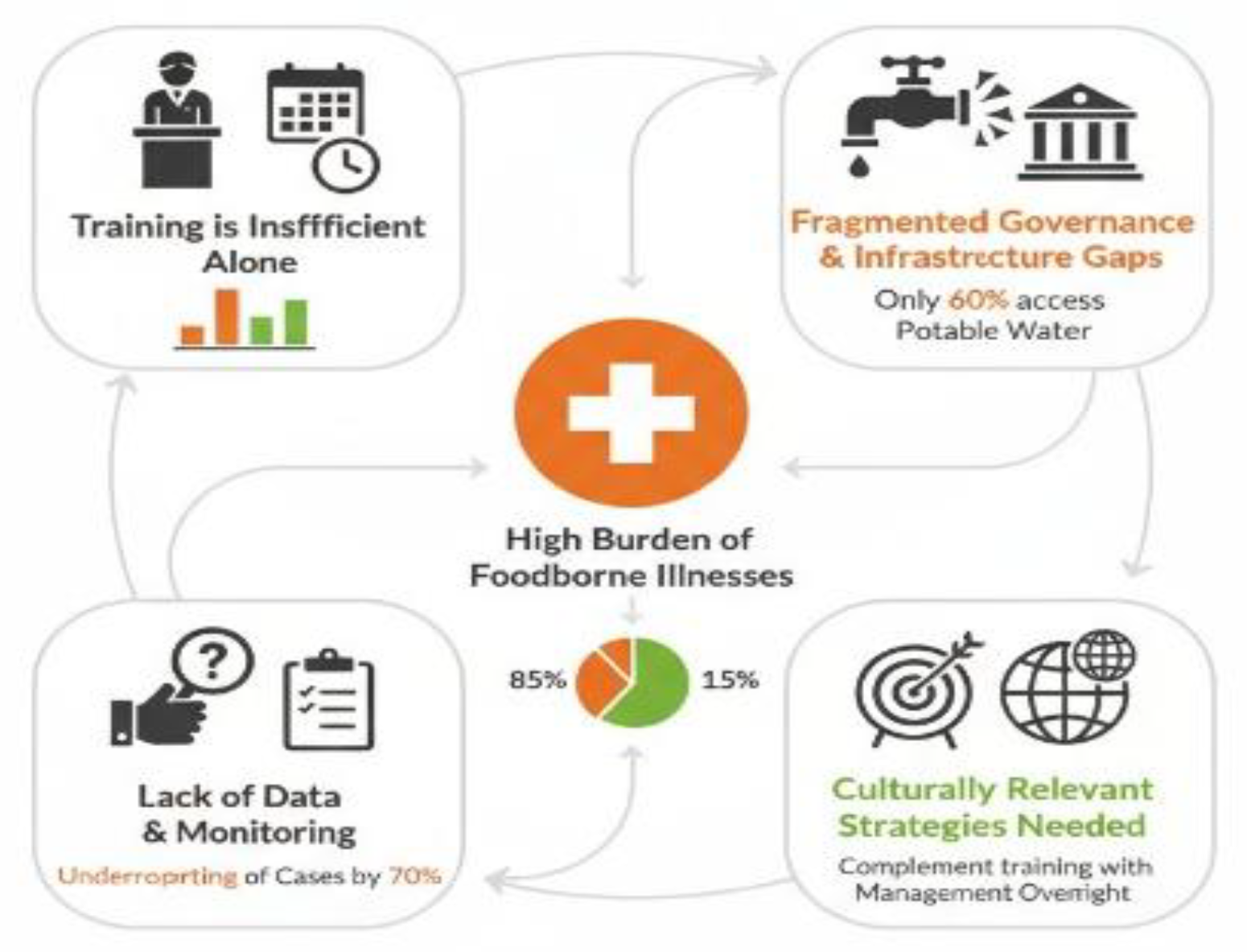

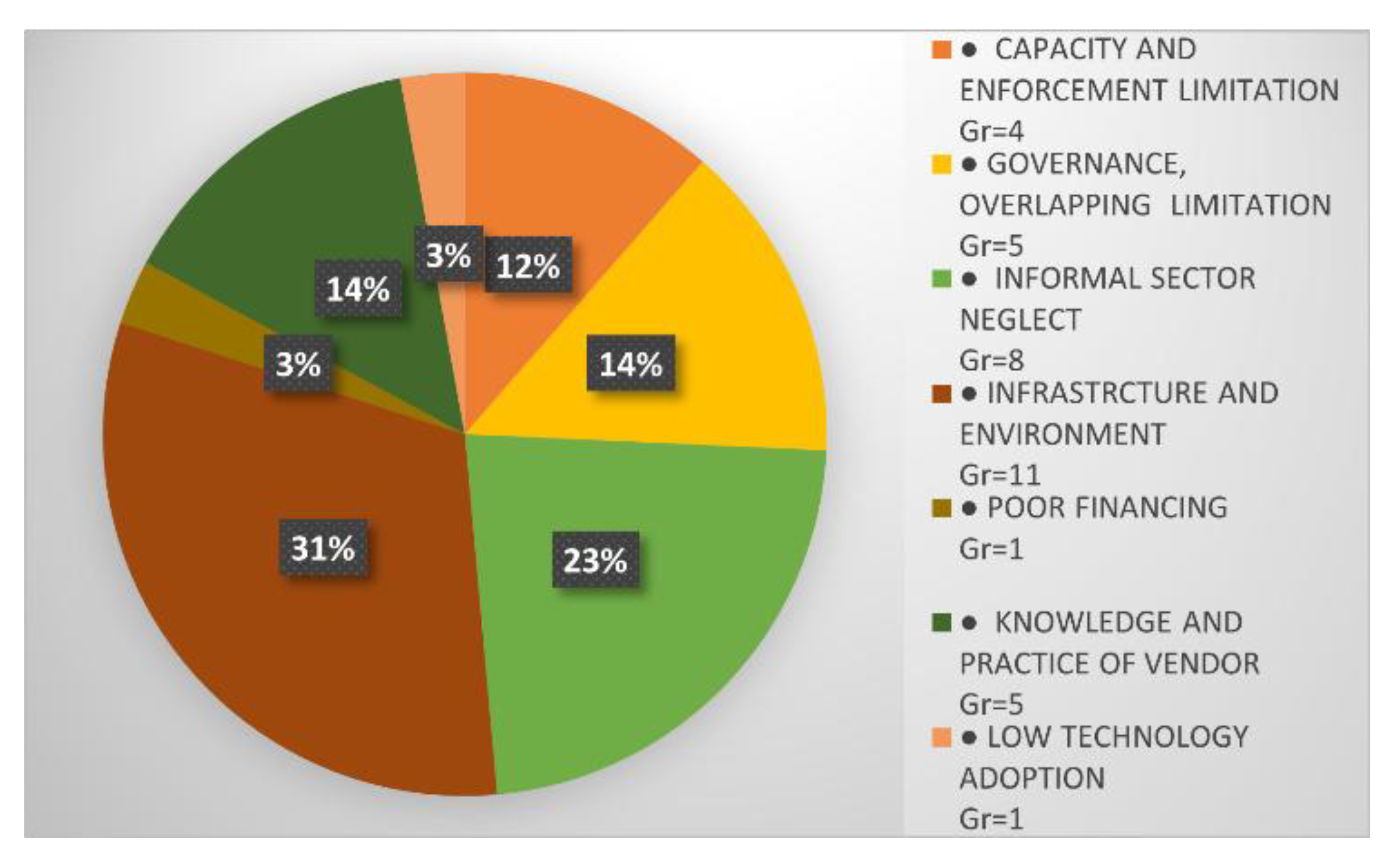

3.5. Limitations to Addressing Food Safety Regulation Among the SFBs?

4. Conclusion and Recommendation:

5. Limitations of the Study

Author’s contribution

Competing Interest

Funding Information

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full meaning |

| CAC | Codex Alimentarius Commission |

| DoH | Department of Health |

| FBD | Foodborne Diseases |

| HACCP | Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point |

| LMICs | Low- Middle-Income Countries |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| SADC | Southern Africa Development Communities |

| SFBs | Small Food Businesses |

Appendix 1

| S/N | Author, Year | Type of Source | Title of Article | Method | Analysis and Result | Conclusion |

| 1. | (Kasapila, 2023) | Discussion Paper | A review of public health-related food laws in East and Southern Africa, EQUINET, Discussion Paper | A desk-based review of public domain legal text and standards that includes international, regional, national, and local documents. Extracted provisions for 17 East and Southern African countries. From September to December 2022. It translated a document into English. | The instruments were mapped, which include the World Health Organization International Health Regulations, Codex guidance, FAO, and WHO food laws, and ISO food safety systems, WTO SPS and TBT rules, SADC food safety guidelines, and AU NEPAD harmonization efforts. The principles identified include prevention across the farm-to-fork continuum. National laws across the 17 countries prohibit adulteration, set standards for labelling, premises requirements, empower inspectors, testing, seizure, or recall. Coverage varies across countries. Processed foods, fortified foods, supplements, and detailed microbial standards have low regulations. Governance is fragmented, led by Health ministries, yet responsibilities sit in Trade, industry, agriculture, and parastatal boards, making harmonization a problem. Many countries do not have biosafety and GMO Acts. Consumer protection is not in-depth. |

The SADC has a very good number of food-related laws in text, but very inconsistent, fragmented, and often incomplete in addressing modern reality. It calls for the creation of Food Acts where it is absent, that integrate risk assessment along the food value chain. It also recommends moving HACCP from voluntary to legal grounds, and more regulations in the informal food sector. |

| 2. | (Southern African Development Community (SADC), 2011) | Online Report | Regional Guidelines for the regulation of Food Safety in SADC Member State. | Consultation with Member state Stakeholders endorsed by Ministers focusing on Codex Standards. It I documented as a model law to be adopted by Member State. | It was identified that the existing policies were fragmented, multiagency food safety responsibilities, non-uniform concept and methods of implementation. There should be a Food Safety Expert Working Group, ad hoc committee to handle technicalities, then constitute a National food Safety coordinating forum. |

Clear Objectives must be set with three key parts: terms, policy and a model law. Risk analysis must be the basis with strong alignment with Codex in terms of traceability, inspection, certification, scientific and technical capacity like a regional rapid alert system. |

| 3. | (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 2014) | Grey Literature | Food and Nutrition Security Strategy, 2015 to 2025 | a Regional Policy Strategy consultation and Ministerial approvals. |

To facilitate the development of food safety policies, legislative, and institutional framework and mechanisms to strengthen the coordination of food safety management. Harmonize and monitor the enforcement of food safety standards including updating and implementing national legislation and regulations to meet the international food safety standards such as the Codex Alimentarius |

Facilitate the accreditation of all food testing laboratories in the region to international or regional food safety institutions: and Facilitate the establishment of a regional network of food testing laboratories. This must be achieved by 2025 |

| 4. | (McCallion et al., 2025) | Journal article | “Interventions in food business organizations to improve food safety culture: a rapid evidence assessment” | A video observation to evaluate the effectiveness of newly developed hand washing pictograms on employees’ hand washing behavior, which included the use of signage with handwashing pictograms with explanations in English and Spanish in high traffic areas, and the habits of employees were measured before and after the intervention. | Microbial analysis was conducted on food contact surfaces, equipment, and hand hygiene before training, four weeks after training, and six months after training. Questionnaires were used to assess changes in food handlers' behavior concerning handwashing at the same time points. The results indicated an increase in knowledge and improvement in behavior surrounding handwashing four weeks after training. It was observed that food handlers relaxed after six months of training and did not maintain the improved behavior over time. | It concluded that while knowledge training can lead to improvements in handwashing practice and some behaviors among food handlers, it is often insufficient on its own to sustain long-term changes in food safety practices. Interventions, like signage, provision of thermometers, and incentives, are necessary to enhance compliance with food safety behaviors like handwashing, thermometer use, and surface cleaning, but it's inadequate. Thereby, suggesting that training should be complemented with strategies aimed at improving management styles and staff oversight to achieve desired outcomes in food safety |

| 5. | (Leahy et al., 2022) | Review article | “Foodborne zoonoses control in LMICs: Identifying aspects of interventions relevant to traditional markets which act as hurdles when mitigating disease transmission.” | It conducted a review of selected case studies drawn from two prior bodies of work, then complemented it with a non-systematic literature search focused on market infrastructure, vendors, consumers, and governance at traditional markets, intending to understand how interventions to reduce foodborne zoonoses have been applied at the market level and to identify barriers and enablers to implementation. | Analysed different case studies such as Infrastructure interventions in Uganda and Nigeria. Vendor-focused education to see if it aligns with their beliefs. Cultural and practical constraints, consumer side, and government interventions. | The review concluded that to achieve sustainable food safety gains, interventions tailored to local cultural, social, and economic contexts, with additional government regulations that work with them. Effective strategies should combine and synergize measures across vendors, consumers, and regulators. |

| 6. | (Sosah & Donkor, 2025) | Review article | Microbial foodborne outbreaks in Africa: a systematic review | An SLR following PRISMA guidelines, capturing foodborne outbreak data, hospitalizations, deaths, country, and year. | 31 papers covering 42 countries across Africa. Covering 877,067 infections 2, 064 hospitalizations, and 2,061 deaths. Food vehicles most implicated are processed, raw meats, cereals, legumes, tubers, and vegetables. Deadliest agents Clostridium botulinum and Listeria monocytogenes. | The study concluded that Africa faces a heavy preventable burden from foodborne outbreaks exacerbated by poor hygiene, inadequate infrastructure, and limited compliance. It is suggested that to reduce this burden, investment should be made in regulations, surveillance, practical hygiene training and retraining, and strong public enlightenment programs |

| 7. | (Thow et al., 2018) | Policy analysis | Improving policy coherence for food security and nutrition in South Africa: a qualitative policy analysis | Content review across nutrition, agriculture, and economic policy documents. 14 interviews with 22 actors from Cape Town, Pretoria, and Johannesburg. Data was analyzed using NVivo. | Three coalitions emerged within the policy system: Economic Growth, Food Security, and Health Coalition. | Priority opportunities were identified as target changes to economic policy that meet both nutrition and economic objectives. Stronger links between producers and consumers through fiscal incentives that make fresh and healthy foods more accessible and affordable. |

|

8. |

(Saxena & Saini, 2019) |

Narrative review article |

Hygiene and Sanitary Practices of Street Food Vendors: A Review. |

It reviewed studies on street food hygiene, personal practices, microbial quality, and risk factors. It aggregates its findings rather than launching new research |

Analysis showed that vendors across all locations show poor hygienic practices, storage practices, and handling. Poor infrastructure, sanitary systems, and waste management. |

It concluded that SFVs widely follow poor hygienic practices, calling for interventions. |

| 9. | (Dama et al., 2024) | Journal article | Food policy analyses and prioritization of food systems to achieve safer food for South Africa | It’s a qualitative and multi-stage design. First, did SLR using PRISMA principles to map challenges and solutions on food safety in South Africa. It then conducted a semi-structured stakeholder interview using a purposive sampling method across all nine provinces. It later did a content analysis using Atlas.Ti to synthesize both the literature review and interview data. Finally, ranked Best Worst scaling with a standardized interval score gotten from best versus worst frequencies. | The results showed 34 distinct challenges, prominent amongst them include weak training and capacity amongst regulators, fragmented institutions and mandates, limited infrastructure, low technology adoption, under regulation of the informal food sector. After the interview and content analysis, the highly rated items include collaborative research to design proactive strategies, mandatory screening of food handlers, tighter enforcement of existing policies, a campaign against food fraud, stronger surveillance, a coordinated communication strategy, and clear consumer-facing information strategies to address complexities, identify priority areas. | Research and technology-led actions are central to transforming South Africa’s food system towards safer food. It recommends collaborative research to curb complexities in the system, stronger and smarter enforcement, continuous surveillance with modern traceability, practical training, public communication, and reliable infrastructure. It also emphasized a harmonised and coordinated framework across multiple agencies. |

| 10. | (Agunyai & Ojakorotu, 2024) | Journal article | Data-driven innovations and sustainability of Food Security: Can Asymmetric Information Be Blamed for Food Insecurity in Africa | It conducted a multistage qualitative systematic review and meta-ethnography, with explicit screening criteria of 108 studies. | Africa’s growing internet and mobile uptake have not translated into food security because of a lack of timely information along the food chain. The review maps structural drivers of asymmetric information, which include skill gaps, weak electrification and connectivity, prevalence of middlemen along the food chain. | Smartphones and digital platforms have high potential to improve food access and usage if the government and stakeholders fix the information gap. It calls for rural electrification, low-cost internet, and dissemination of accurate, practical food and nutrition information |

| 11. | (Asiegbu et al., 2020) | Journal article | Microbial Quality of RTE Street-vended food Groups sold in Johannesburg metropolis, South Africa. | A cross-sectional study with stratified random sampling in Johannesburg, 205 RTE was collected. Microbial testing was done using ISO standards. | 85.37% has aerobic microbial growth, 46.36% Listeria growth, and 78.18% Enterobacteriaceae. | RTE represented a public health concern with large aerobic growth. it calls for vendor education and enforcement of food safety legislation. |

| 12. | (Letuka et al., 2021) | Journal article | Street food handler food safety knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported practices, and consumer perception about street food vending in Maseru, Lesotho | The survey was cross cross-sectional descriptive on-site survey using semi semi-structured questionnaire for 50 SFVs and 93 consumers, with an observational checklist. Data was analysed using statistical tools | Vendors were mostly female 60%, safety knowledge was scored 49%, 95% had a positive attitude, zero vendors used gloves, 64% wore aprons, 98% prepared meals in advance, 84% reported checking of expiry dates.62% protect their meals from pests, 60% had access to potable water. 74% of consumers ate occasionally, and 10% reported illness after consumption. | There is a hygiene and infrastructure gap knowledge is low despite positive attitudes towards food safety. It recommends compulsory food safety training with frequent inspection, practical use of protective clothing, and adequate infrastructure. |

| 13. | (Boatemaa et al., 2019) | Journal article | Awakening from Listeriosis Crisis: food safety challenges, practices, and governance in the food retail sector in South Africa | SLR process across three pieces of evidence, national food safety policies and regulations, and company reports between 2013 to 2018. Thematic analysis guided by FAO food safety risk analysis. | 74 documents total; 13 policies, 47 media articles | Food safety requires shared responsibility among all stakeholders, backed by stronger government synergised enforcement across government parastatals |

| 14. | (Cook et al., 2024) | Journal article | Nutritional, economic, social, and governance implications of traditional food markets for vulnerable populations in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review | Web search was done between March to April 2023 for articles between 2015 – 2023. The 73 study was examined using PRISMA guidelines. | Geographic locations examined are East and Southern Africa, with South Africa 8, Zambia 8. The nutrition theme dominates with 47, and governance with 27and other work on food safety regulations. The result showed a rough and multilevel governance. Regulators and the informal trader association divide responsibilities but have non-synergized policies. |

It concluded by advocating that traditional markets are indispensable for low-cost and nutritious meals. It is social part of SSA urban centres but its potential is affected by food safety problems, inadequate infrastructure, gender inequalities, and uncoordinated regulation. It therefore proposed an investment in market infrastructure, stronger nutrition-focused programs, and expanded access to finance to improve food safety metrics. |

| 15. | (Sepadi & Hutton, 2025) | Journal article | Health and Safety Practices as Drivers of Business performance in Informal Street Food Economies: An integrative Review of Global and Southern African Evidence | A review was done using Atlas Ti, narrative synthesis with vote counting, findings were mapped to the Health Belief Model construct and Balanced Scorecard dimensions. Used 76 articles. | 70% of the article was moderate to high. Most of the study was quantitative research and had a cross-sectional design, with qualitative case studies. 73% reported a positive link between hygiene and food safety compliance and outcomes of business performance like consumer trust, revenue and inspection outcomes. | It is finalized by reporting that health and safety practices are not only a compliance responsibility but are an important strategy that improves vendor performance because it earns the consumer trust and operational benefits. This strategy will improve if there is adequate infrastructure to support them, well-trained vendors, and if irregular enforcement is eliminated. This would help build models that match vendor realities to build a sustainable food system. |

| 16. | (Desye et al., 2023) | Journal Article | Food safety knowledge, attitude and practice of street food vendors and associated factors in low and middle-income countries LMICs: a systematic review and meta-analysis | Review with registered protocol called PROSPERO data was analysed using STATA 14 with random effects models, meta prop. It identified bias via funnel plots and Egger's test, sensitivity, and subgroups by country. | 14 cross-sectional studies of 2,989 vendors across LMICs, Lesotho ranked high in food safety practice. Secondary education has six times higher odds. |

There was a distinct gap between what the vendors know, their beliefs, and their actions. Frequent practical training and tailored health education, coupled with the provision of low-cost hygiene materials and supportive oversight, are used to improve practice and reduce food safety risk. It therefore seeks coordinated NGO and local governments' implementation and requests future evidence that includes broader designs using simple language and pictograms. |

| 17. | (Kimanya, 2024) | Journal article | Contextual interlinkages and authority levels for strengthening coordination of national food safety control in Africa | FAO and WHO guidelines were synthesized with CODEX text to contextualize all stakeholders all the African food chain. | There are interlinkages of how food safety measures intersect with health, agriculture, trade, and standards in relation to food business operators, consumers, and regulators have a responsibility in the adoption of Good Manufacturing Practices, hygiene, standards, and consumer information. The weighed multi-agency, single agency, and integrated coordination. |

The study advocates for autonomous national food safety agency to be hosted by the Ministry of Health and gives power to the multisectoral board. With specific job responsibility well spelt out, separate risk assessment from risk management and raise consumer awareness. It must align all the sector policies with food safety along the farm-to-fork continuum. |

| 18. | (Mphaga et al., 2024) | Journal article | “Unlocking food safety, a comprehensive review of South Africa’s food control and safety landscape from an environmental health perspective” | Narrative review of South Africa’s food control and safety system, drawing from different sources from 2000 to 2023, using 27 studies; 17 ARTICLES, 8 legislative documents, 2 government guidelines. | The synthesis of legislative and practice evidence to diagnose. Findings: inadequate penalties, fragmented multi-agency governance that affects enforcement, a limited number of inspectors and laboratories, complex labelling, and emerging e-commerce risks. | The study concluded that South Africa’s food safety network is complex, defragmented, and vulnerable the existing Act R638 needs to be backed with stricter penalties. A more centralized National food control authority it should be complimented with adequate capacity building. It also recommended modern detection technologies and system consolidation. |

| 19. | (Kinyua & Thebe, 2023) | Journal article | Driver of Scale and sustainability of Food Safety Interventions in informal Markets: Lessons from the Tanzanian Dairy Sector. | Mixed method design anchored on the theory of change framework. Data was sourced from reviews, surveys, and key informant interviews with stakeholders. Data was analysed with STATA. | The results showed reach was limited in terms of training of stakeholders. There was a weak enabling environment, an inconsistent policy, limited financing and staffing; trader association support was absent. Sensitization of the public vanished after the donor support stage. | The study argues that there is need for a clear policy, financing, and staff upgrade. Training of vendors should be valuable for them which accommodates lifelong learning methods, engages technologies with practical refresher courses. |

| 20. | (Madilo et al., 2024) | Journal article | “Challenges with food safety adoption: A review” | |||

| 21. | (Makhunga & Hlongwana, 2024) | Scientific report | Food handling practices and sanitary conditions of charitable food assistance programs in eThekwini district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study of 196 charitable food assistance programs across five municipalities, with onsite observation with 37 standardized list | 94% female, 60.7% had more than 10 years of experience in food service, and 87.7% had never attended formal food safety training in the last five years. | Personal hygiene, staff facilities, product information, food hygiene, storage, and pest control were scored poorly. |

| 22. | (Mbombo-Dweba et al., 2022) | Journal article |

A descriptive cross-sectional study of food hygiene practices among informal ethnic food vendors in Gauteng, South Africa | Immigrant-led ethnic food shops in Gauteng province were surveyed using the snowball sampling technique. A total of 40 respondents were collected. A checklist to assess compliance with the WHO 5 Keys to Safer Food was used. | 95% operated in permanent structures and had access to running water, 0% had a thermometer, 65% do not own a freezer, 55% had a microwave. 65% were not aware of the holding temperature. | Hygiene practices were grossly inadequate, with weak cold storage, and poor hot holding, raising high risk of contamination. |

| 23. | (Gadaga & Mutukumira, 2020) | Journal article | Responsiveness of Food safety emergencies in Eswatini: The case of Listeriosis Outbreak in South Africa | Descriptive review and case study analysis. A review of the food control system, legislation, institutions, laboratory capacity, and emergency procedure following a Listeriosis outbreak in Eswatini from 2017 to 2018 | 1049 confirmed with 209 death cases from the consumption of processed meat, exported to 15 African countries, including the study area. Regulatory instruments in existence were few, and outdated sampling and testing procedures were not specified; punishments were not deterrent. There is no accredited national food testing laboratory; Eswatini could not perform in-country testing and only relied on awareness and recall of food products. | The country must strengthen its food control system, modernize its legislation and food safety regulations, set up accredited food laboratories with molecular capacity, and delegate clear responsibility to government parastatals. |

| 24. | (Mkhwanazi et al., 2024) | Journal article | Food safety governance in South Africa | Review and report and grey literature from different databases. | Lack of coordination among national departments, limited industry partnership, and general inefficiency linked to overlapping mandates | Recommends a centralized, transparent, and collaborative government food control system to manage complexities and improve public health protection. |

| 26. | (Oladipo-Adekeye & Tabit, 2021) | |||||

| 27. | Gordon et al.,2020 | White paper | Technical considerations for the implementation of food safety and quality systems in developing countries | It is a narrative chapter to synthesize regulatory, technical, and market requirements | Inconsistent and fragmented standards and regulations | A centralized food control system is mandatory. |

| 28. | (Sandra Boatemaa Kushitor et al., 2022) | Journal article | The complex challenge of governing food systems: the case of South African food policy | 97 policies were gathered, 91 were analysed and coded against 7 domains: agriculture, environment, social protection, health, land, education, and rural development. | The result was assessed through the lens of independence from other sectors, the presence of coordination mechanisms, and evidence of a learning ethos. | They identified that policy making and implementation operate independently and fail to share information which limits learning and weakens impact. It was recommended that South Africa needs a tangible implementation plan supported by effective coordination, consolidated monitoring, and an evaluation approach. |

| 29. | (Unnevehr, 2022) | Journal article | Addressing food safety challenges in rapidly developing food systems | Narrative, state-of-the-art economic review with specific illustration. Focusing on: rising cost, market incentives, and suitable policies using the listeriosis crisis of South Africa. | From 2017 – 2018, 1060 cases of Listeriosis were confirmed, with 216 deaths, resulting in an economic impact of $260 million in mortality costs, $10.4 million in hospitalization, and $15 million in productivity and export losses | A risk assessment shift can guide public action, using emerging technologies to sharpen incentives and detection. The investment is not commensurate with the level of challenge. We have to build strong surveillance, management capacity, and use technologies smartly. |

| 30. | (Ayalew et al., 2023) | Book Chapter | A Paradigm Shift in Food Safety for Africa. |

Policy synthesis to consolidate African Union frameworks and initiatives to propose a continental shift in food safety regulation | Fragmented mandates, weak surveillance and labs, hazard-based rather than risk-based control, bias toward export chains, while domestic and informal markets dominate actual consumption. Africa sits in a “transitioning” risk zone where demand and supply chain complexity outpace public and private control capacity. | Africa must prioritize establishing the Africa Food Safety Agency, developing and funding national risk-based strategies, implementing the AU food safety framework, strengthening surveillance, and conducting national burden studies. Innovations such as whole genome sequencing, big data, blockchain, and Internet of Things can help if SADC and other regions can avoid the divide. |

| 31 | (Rugji et al., 2025) | Journal article | Utilization of AI, reshaping the future of food safety, agriculture, and food security: a critical review | It synthesizes recent research on AI methods, machine learning, deep learning, computer vision, predictive modeling, robotics, supply chain tools, and policy development across food safety and security. | AI supports early warning, risk prediction, and rapid detection. It can also predict the accuracy of microbial count under different conditions. Microbiome analytics to classify metagenomic profiles with 90% accuracy have been reported. The are slim digitized food safety data, privacy and data sharing constraints, and limited data literacy within the workforce. | It recognizes fast-evolving AI policy frameworks across regions, like the EU’s proposed AI Act and national guidance in several countries, highlighting uneven regulatory readiness for food uses. |

Appendix 2

| S/N | Countries | Public health law |

Food control / Standards law |

Standards law | Consumer Protection Law |

Fishery-related Law | Animal Health law | Diary-related Law | Meat/livestock law |

Plant-related law | Other law |

| 1. | Angola | IHR, 2005 | N/A | N/A | Consumer Protection Law, 2003 |

N/A | Animal Health Act, CAP No. 65 Of 2004 |

N/A | N/A | Law No. 5/21 Approving the Plant Health Act, 2021 |

N/A |

| 2. | Botswana | Public Health Act, CAP 63:01 Amended as Act 11 of 2013 |

Food Control Act 65:05 of 1993 |

Standards Act CAP 43:07, 1995 |

Consumer Protection Act, CAP 42:07 |

Fish Protection Act, CAP 37:01, 1975 |

Diseases of Animals Act. CAP 37:01, 2008 |

N/A | Livestock And Meat Industries Act, CAP 36:03, 2007 |

Plant Protection Act, CAP 35:02, 2007 |

N/A |

| 3. | Comoros | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4. | Democratic Republic of Congo | IHR, 2005 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 5. | Eswatini | Public Health Act, 1969 |

N/A | Standards and Quality Act, 2003 |

The Protection of Freshwater Fish Act. 1937 |

The Animal Diseases Act, 1965 |

Daily Act, 6/1968 | Veterinary Public Health Act, 2013 (Act No. 17 of 2013) |

The Seeds and Plant Varieties Act, 2000 The Plant Health Protection Act, 2020 |

N/A | |

| 6. | Lesotho | Public Health Order (No. 12 1970). |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Stock Diseases, 1996 |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 7. | Madagascar | IHR, 2005 | Decree No. 93 -844 | N/A | Order No. 8333/2001 |

N/A | Law No. 2000 – 018. | Decree No. 2011 – 588 |

N/A | N/A | Order No. 24657/2004 |

| 8. | Malawi | Public Health Act, CAP 34:01 of 1948 |

N/A | Malawi Bureau of Standards Act, CAP 51:02, 2012 |

Consumer Protection Act, CAP 48:10 Competition and Fair Trading Act, 2000 |

Fisheries Conservation and Management Act, No.25, 1997 |

Control and Diseases of Animals Act, CAP 66:02, 1987 |

Milk and Milk Products Act, CAP 67:05, 1972 |

Meat and Meat Products Act, CAP 67:02 |

Seed Act, CAP 67:06 Of 1997 Plant Protection Act, 2018 |

Biosafety Act CAP 60:03 of 2007 |

| 9. | Mauritius | Public Health Act. CAP 277 of 1925 |

Food Act, 2022, Act No. 12 of 2022 |

Mauritius Standards Bureau Act, Act 12 0f 1993 |

Fair Trading Act, 1980 |

Fisheries and Marine Resources Act. 2007, Act No. 27 of 2007 |

The Animal Diseases Act, Act 9/ 1925 |

N/A | Meat Act Act No. 54 of 1974 |

Seeds Act, 2013 (No. 10 of 2013) Plant Protection Act, 2006 |

Biosafety Act, Act No. 3 of 2004 |

| 10. | Mozambique | IHR, 2005 | N/A | Standards Act (Law Decree 02/93) |

Decree No. 76/2009 |

Decree No. 17/2001 | Ministerial Order No. 100/87 |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Ministerial Order No. 80/87 Plant Genetic Resources |

| 11. | Namibia | Public Health Act, Act No. 2 Of 2015 |

N/A | Standards Act, Act, No. 18 of 2005 |

N/A | Marine Resources Act, Act, No. 27 of 2000 |

Animal Health Act No.1 of 2011 |

Diary Industry Act (Acct 30 0f 1961) |

Meat Industry Act, Act No. 12 of 1961 |

Plant Quarantine Act, No 7, 2008 |

Biosafety Act No.7 of 2008 |

| 12. | Seychelles | Public Health Act 2015, Act 13 of 2015 |

Food Act, 2014 (Act 8 of 2014) |

Seychelles Bureau Of Standards Act. 2014(No. 2 of 2014) |

Consumer Protection Act 2010(Act 30 of 2010) |

Fisheries Act, 2014 (Act 20 of 2014) |

Animals (Diseases And Imports) Act, 1981 |

N/A | N/A | Plant Protection Act, 1996(Chapter 171. A 1996) |

N/A |

| 13. | South Africa | National Health Act, 2003(Act 61 Of 2003) |

Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Amendment Act, 2007 (Act 54 of 1972, Amended as Act 39 of 2007) |

Standards Act, 2008(Act 08 of 2008) |

Consumer Protection Act ( Act 68 of 2008) |

Sea Fisheries Act, 1998(Act 12 of 1988) |

Animal Diseases Act, 1984 (Act 35 of 1984) |

Diary Industry Act (Act 30 0f 1961 as Amended by the Diary Industry Laws Amendment Act, 1972) |

Meat safety Act 40 of 2000 |

Plant Health (Phytosanitary), Bill B14-2021) |

Genetically Modified Organisms Act 15 of 1997 |

| 14. | Tanzania | Public Health Act, 2009 (No. 1 of 2010) |

Tanzania Food, Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 2003(No. 1 of 2003). |

The Standards Act, (Act No. 2 of 2009) |

Fair Competition Act, 2003 |

The Fisheries Act, 2003, (Act No. 22 of 2003) |

The Animal Diseases Act, 2003 (Act No. 17 Of 2003) |

Dairy Industry Act, 2004(No 8 of 2004) |

Meat Industry Act, 2006 (No. 10 of 2006) |

The Plant Protection And Health Act, 2015 |

|

| 15. | Zambia | Public Health Act (CAP, 22 of 1995) |

Food and Drugs (1972) |

Standards Act 2017 (No. 4 of 2017) |

Competition and Consumer Protection Act, 2010 |

Fisheries Act, 2011 | Animal Health Act, 2010 |

Diary Industry Development Act, 2010 |

N/A | Plants Pests and Diseases Act, 1994 (CAP 233, 1994) |

Biosafety Act, 2007 |

| 16. | Zimbabwe | Public Health Act (CAP 15- 17, No. 11/2018) |

Food and Standards Act. 2001 |

Food and Food Standards Act (CAP 15:04, 2001) |

Consumer Protection Act, 2019 |

Parks and Wildlife Act (CAP 20:14), 1991 |

Animal Health Act, (CAP 36:02, 1988) |

Diary Act (CAP 18:08) Revised Edition of Act No. 28 of 1937 Amended by Act No. 22 of 2001 |

N/A | Plant Pests and Diseases Act, 2001 |

N/A |

References

- Agunyai, S. C.; Ojakorotu, V. Data-Driven Innovations and Sustainability of Food Security: Can Asymmetric Information Be Blamed for Food Insecurity in Africa? [Article]. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2024, 16(20), Article 8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, B. A.; Amenu, K.; Girma, S.; Grace, D.; Srinivasan, R.; Roothaert, R.; Knight-Jones, T. J. D. Knowledge, attitude and practice of tomato retailers towards hygiene and food safety in Harar and Dire Dawa, Ethiopia [Article]. Food Control 2023, 145, Article 109441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Granada, Y.; Neuhofer, Z. T.; Bauchet, J.; Ebner, P.; Ricker-Gilbert, J. Foodborne diseases and food safety in sub-Saharan Africa: current situation of three representative countries and policy recommendations for the region. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2021, 16(2), 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimi, K.; Adebayo, O. C. Food Safety Practices among Vendors in State Secondary Schools in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo State. Food Science and Engineering 2024, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiegbu, C. V.; Lebelo, S. L.; Tabit, F. T. Microbial quality of ready-to-eat street vended food groups sold in the Johannesburg metropolis, South Africa [Article]. Journal of Food Quality and Hazards Control 2020, 7(1), 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, A., Kareem, F. O., & Grace, D. (2023). A paradigm shift in food safety for Africa. https://doi.org/https://hdl.handle.net/10568/135104.

- Battersby, S., & Miles, D. (2025). Ethics and the Environmental Health Profession: The Importance of Being Ethical. Taylor & Francis.

- Boatemaa, S.; Barney, M.; Drimie, S.; Harper, J.; Korsten, L.; Pereira, L. Awakening from the listeriosis crisis: Food safety challenges, practices and governance in the food retail sector in South Africa. Food Control 2019, 104, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büthe, T.; Harris, N.; Hale, T.; Held, D. Codex alimentarius commission. In Handbook of Transnational Governance: Institutions and Innovations; 2011; pp. 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Chilenga, C.; Masamba, K.; Kasapila, W.; Ndhlovu, B.; Munkhuwa, V.; Rafoneke, L.; Machira, K. Mycotoxin management in sub-Saharan Africa: A comprehensive systematic review of policies and strategies in Malawi. Toxicology Reports 2024, 101871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.; Trevenen-Jones, A.; Sivasubramanian, B. Nutritional, economic, social, and governance implications of traditional food markets for vulnerable populations in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic narrative review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8, 1382383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dama, T. I.; Loki, O.; Fitawek, W.; Mpuzu, S. M. Food policy analyses and prioritisation of food systems to achieve safer food for South Africa. Applied Food Research 2024, 4(2), 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulations governing general hygiene requirements for food premises and the transport of food, and related matters (R638 of 2018). Government Gazette,, (2018). https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201806/41730gon638.pdf.

- Desye, B.; Tesfaye, A. H.; Daba, C.; Berihun, G. Food safety knowledge, attitude, and practice of street food vendors and associated factors in low-and middle-income countries: A Systematic review and Meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(7), e0287996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Thirty Fourth Regional Conference on Food Safety, Rome, 17 to 24 November 2007, Bridging the gap between food safety policies and implementation. Retrieved November from; 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Strategic priorities for food safety within the FAO Strategic Framework 2022 to 2031. In FAO; Rome, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); S. Food and Nutrition Security Strategies; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gadaga, T. H.; Mutukumira, A. N. Responsiveness to Food Safety Emergencies in Eswatini—The Case of Listeriosis Outbreak in South Africa—. Engineering in Agriculture, Environment and Food 2020, 13(3), 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.; Ferrara, L.; Calogero, A.; Montesano, D.; Naviglio, D. Relationships between food and diseases: What to know to ensure food safety. Food Research International 2020, 137, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibb, H. J.; Barchowsky, A.; Bellinger, D.; Bolger, P. M.; Carrington, C.; Havelaar, A. H.; Oberoi, S.; Zang, Y.; O'Leary, K.; Devleesschauwer, B. Estimates of the 2015 global and regional disease burden from four foodborne metals - arsenic, cadmium, lead and methylmercury. Environ Res 2019, 174, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.; DeVlieger, D.; Vasan, A.; Bedard, B. Technical considerations for the implementation of food safety and quality systems in developing countries. In Food safety and quality systems in developing countries; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D. Food safety in developing countries: an overview. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, D.; Dipeolu, M.; Alonso, S. Improving food safety in the informal sector: nine years later. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology 2019, 9(1), 1579613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, S., Jaffee, S., & Wang, S. (2023). New directions for tackling food safety risks in the informal sector of developing countries. https://doi.org/https://hdl.handle.net/10568/130652.

- Hunter-Adams, J.; Battersby, J.; Oni, T. Fault lines in food system governance exposed: reflections from the listeria outbreak in South Africa. Cities & Health 2018, 2(1), 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, S., Henson, S., Unnevehr, L., Grace, D., & Cassou, E. (2018). The safe food imperative: Accelerating progress in low-and middle-income countries. World Bank Publications.

- Kasapila, W. (2023). A review of public health-related food laws in east and southern Africa. https://doi.org/https://equinetafrica.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/EQ%20ESA%20Food%20law%20review%20Jan2023.pdf.

- Kimanya, M. E. Contextual interlinkages and authority levels for strengthening coordination of national food safety control systems in Africa. Heliyon 2024, 10(9), Article e30230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyua, C.; Thebe, V. Drivers of Scale and Sustainability of Food Safety Interventions in Informal Markets: Lessons from the Tanzanian Dairy Sector [Article]. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15(17), Article 13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushitor, S. B.; Alimohammadi, S.; Currie, P. Narrative explorations of the role of the informal food sector in food flows and sustainable transitions during the COVID-19 lockdown [Article]. PLOS Sustainability and Transformation 2022, 1(12), e0000038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushitor, S. B.; Drimie, S.; Davids, R.; Delport, C.; Hawkes, C.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Ngidi, M.; Slotow, R.; Pereira, L. M. The complex challenge of governing food systems: The case of South African food policy. Food Security 2022, 14(4), 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A. Regulatory “Reliance” in Global Trade Governance. European Journal of Risk Regulation 2024, 15(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, E.; Mutua, F.; Grace, D.; Lambertini, E.; Thomas, L. F. Foodborne zoonoses control in low-and middle-income countries: Identifying aspects of interventions relevant to traditional markets which act as hurdles when mitigating disease transmission. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6, 913560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letuka, P.; Nkhebenyane, J.; Thekisoe, O. Street food handlers' food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices and consumers' perceptions about street food vending in Maseru, Lesotho [Article]. British Food Journal 2021, 123(13), 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madilo, F. K., Kunadu, A. P. H., & Tano-Debrah, K. (2024). Challenges with food safety adoption: A review. JOURNAL OF FOOD SAFETY, 44(1), e13099. https://doi.org/ARTN e13099.

- 10.1111/jfs.13099.

- Makhunga, S.; Hlongwana, K. Food handling practices and sanitary conditions of charitable food assistance programs in eThekwini District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. SCIENTIFIC REPORTS 2024, 14(1), Article 26366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbombo-Dweba, T. P.; Mbajiorgu, C. A.; Oguttu, J. W. A descriptive cross-sectional study of food hygiene practices among informal ethnic food vendors in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Italian Journal of Food Safety 2022, 11(2), 9885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallion, S.; Beacom, E.; Dean, M.; Gillies, M.; Gordon, L.; McCabe, A.; McMahon-Beattie, U.; Hollywood, L.; Price, R. Interventions in food business organisations to improve food safety culture: a rapid evidence assessment. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2025, 65(26), 5066–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhwanazi, N. S.; Adelle, C.; Korsten, L. Food safety governance in South Africa. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphaga, K. V.; Moyo, D.; Rathebe, P. C. Unlocking food safety: a comprehensive review of South Africa's food control and safety landscape from an environmental health perspective. BMC PUBLIC HEALTH 2024, 24(1), Article 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwamakamba, L.; Mensah, P.; Takyiwa, K.; Darkwah-Odame, J.; Jallow, A.; Maiga, F. Developing and maintaining national food safety control systems: experience from WHO African region. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 2012, 12(4), 6291–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanza, P. M. A Equity-focused Monitoring and Evaluation and Performance of School-based Health Projects. The African journal of monitoring and evaluation 2024, 2(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo-Adekeye, O. T.; Tabit, F. T. The food safety knowledge of street food vendors and the sanitary compliance of their vending facilities, Johannesburg, South Africa. JOURNAL OF FOOD SAFETY 2021, 41(4), Article e12908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J. M.; Akl, E. A.; Brennan, S. E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piližota, V. Fruits and vegetables (including herbs). In Food Safety Management; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 235–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugji, J.; Erol, Z.; Taşçı, F.; Musa, L.; Hamadani, A.; Gündemir, M. G.; Karalliu, E.; Siddiqui, S. A. Utilization of AI–reshaping the future of food safety, agriculture and food security–a critical review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2025, 65(26), 5136–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G.; Saini, P. Hygiene and Sanitary Practices of Street Food Vendors: A Review. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepadi, M. M.; Hutton, T. Health and Safety Practices as Drivers of Business Performance in Informal Street Food Economies: An Integrative Review of Global and South African Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2025, 22(8), 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, S. (2023a). Crackdown on illicit goods and expired foods gets underway in parts of Gauteng. https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/ crackdown-on-illicit-goods-and-expired-foods-gets-under-way-in- partsof-gauteng-bcfed479-b6c7-4a20-a7db-0fdaf9c88bb9.

- Sithole, S. (2023b). Fake food flooding South Africa’s townships, health and safety concerns relating to food safety fraud..https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/fake-food-flooding-sas-townships-50b98259-944b-4bb0-97b871566c2f58#:~:text=About%203km%20from%20Krugersdorp%2C%20tucked,Grand%2DPa%20medication%20for%20headaches.

- Sosah, F. K.; Donkor, E. S. Microbial foodborne outbreaks in Africa: a systematic review. International Health 2025, ihaf058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern African Development Community (SADC). (2011). SADC regional food safety regulation: an assessment 2010. Gaborone, Southern African Development Communities. Regional_Guidelines_for_the_Regulation_of_Food_Safety_in_SADC_Member_States__EN.pdf.

- Thow, A. M.; Greenberg, S.; Hara, M.; Friel, S.; Dutoit, A.; Sanders, D. Improving policy coherence for food security and nutrition in South Africa: a qualitative policy analysis. Food Security 2018, 10(4), 1105–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnevehr, L. J. Addressing food safety challenges in rapidly developing food systems. Agricultural Economics 2022, 53(4), 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).