Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

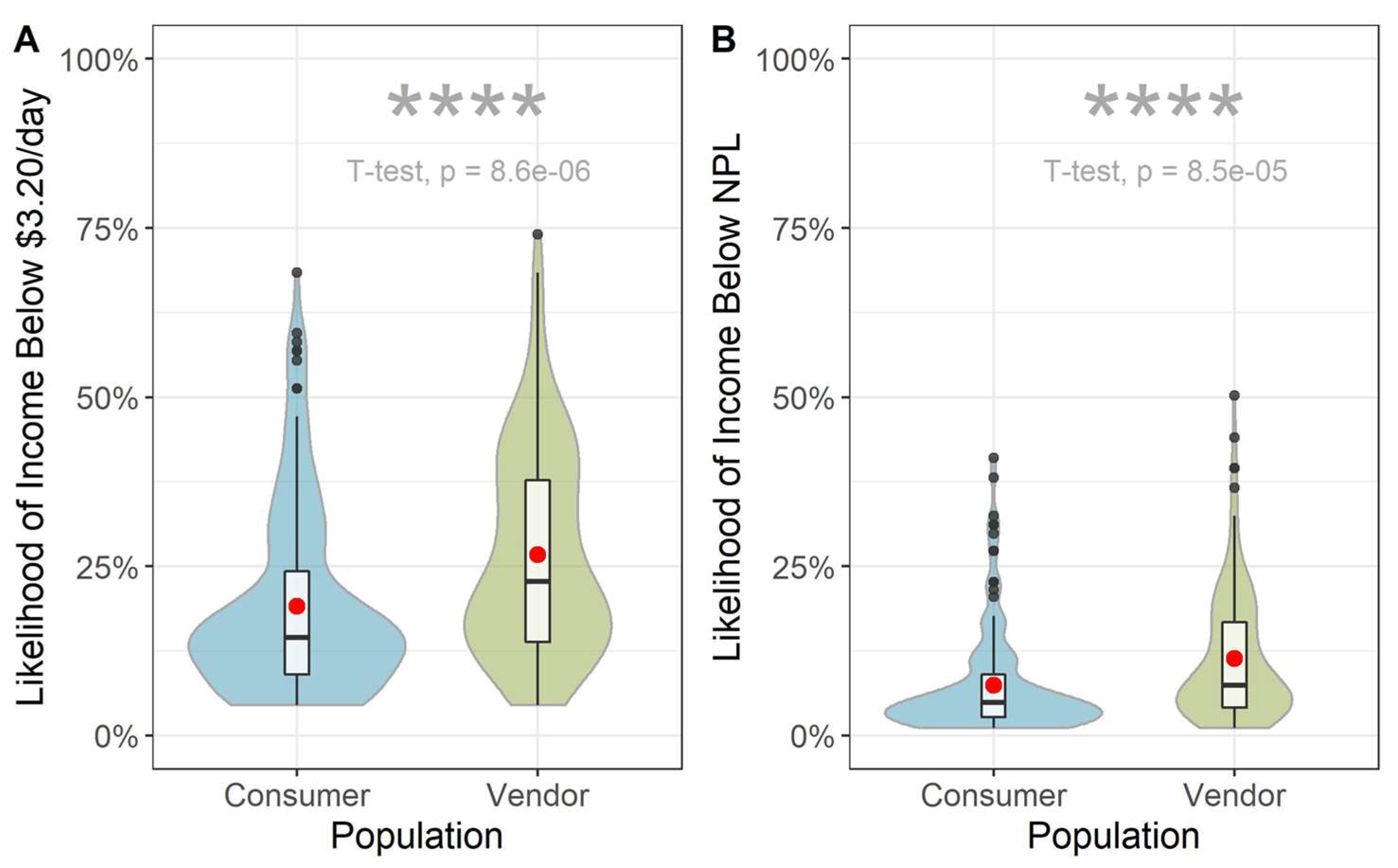

3.1. Respondent demographics

3.2. Consumer survey

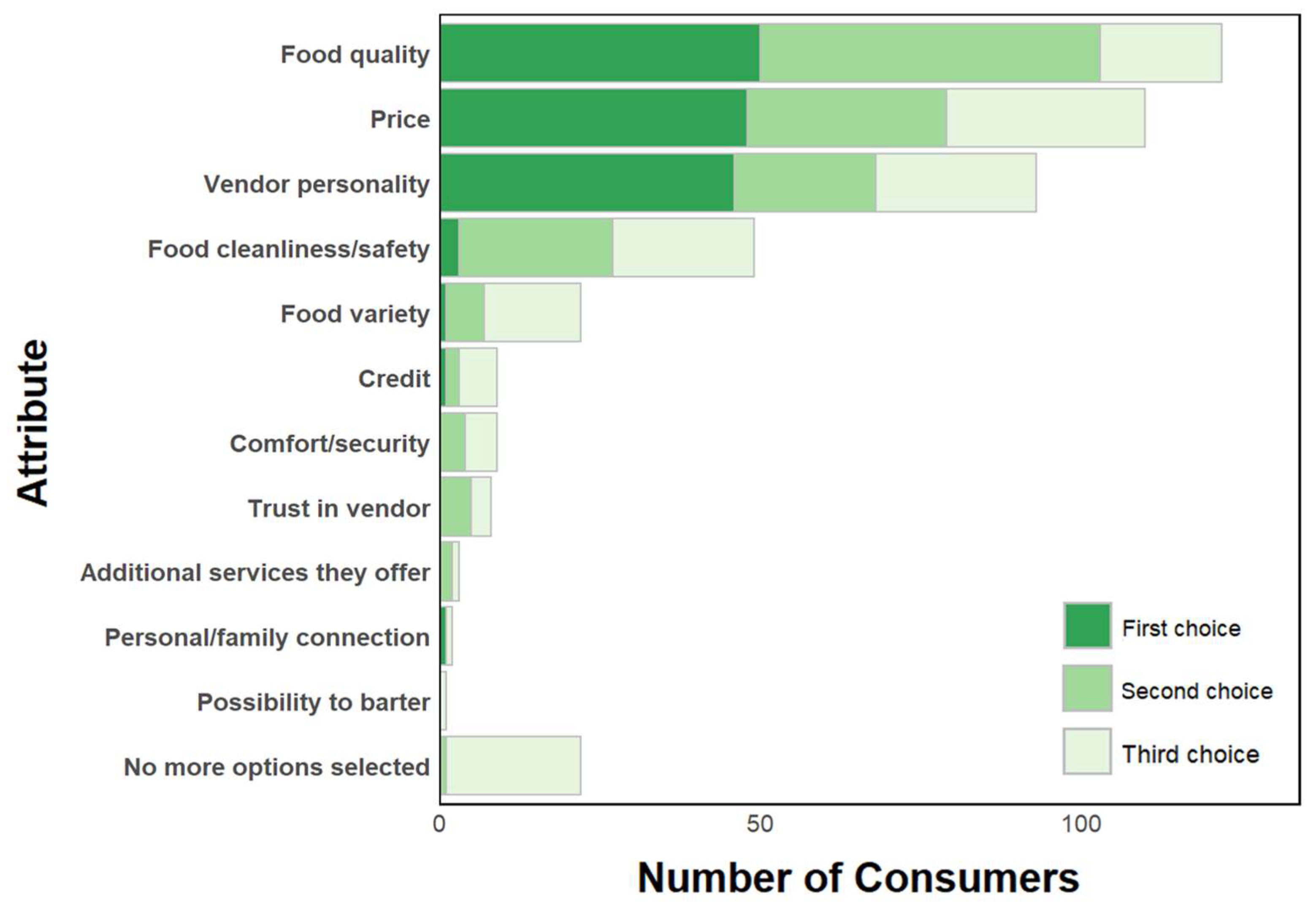

3.2.1. Food Purchasing Motivations and Behaviors

3.2.2. Food Safety Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitudes

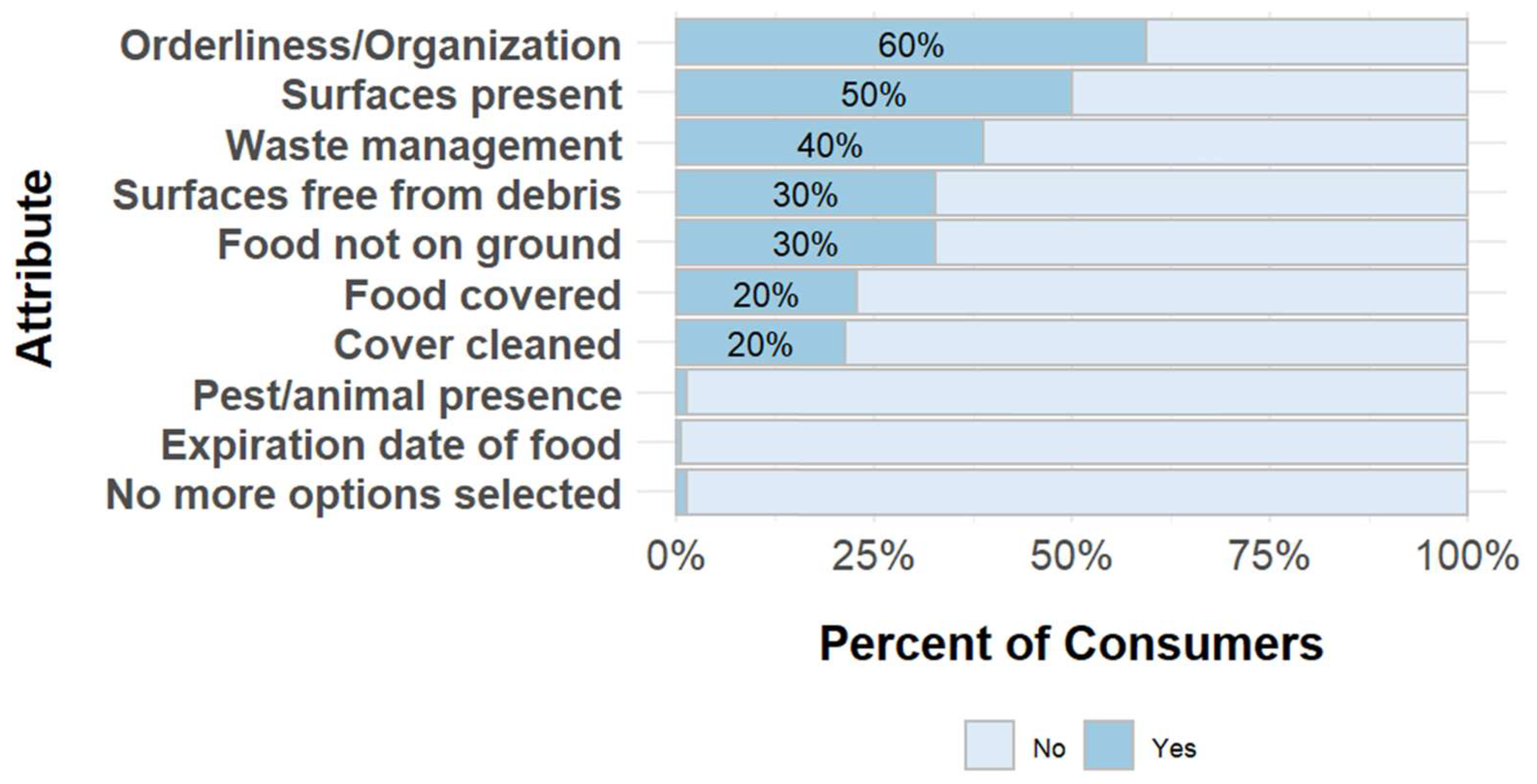

3.2.3. Food Safety Choices and Behaviors

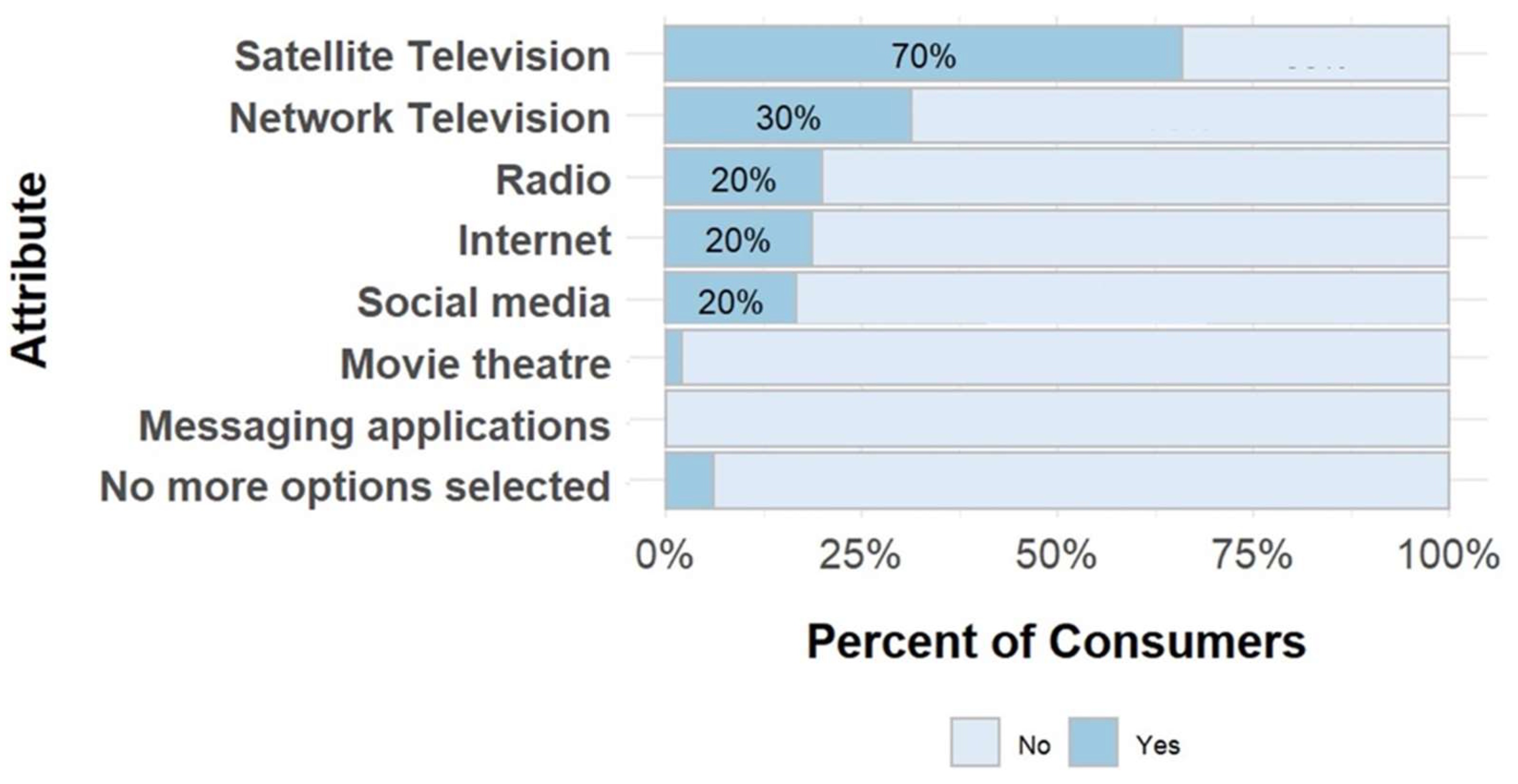

3.2.3. Food Information Sources and Media Use

3.3. Vendor Survey

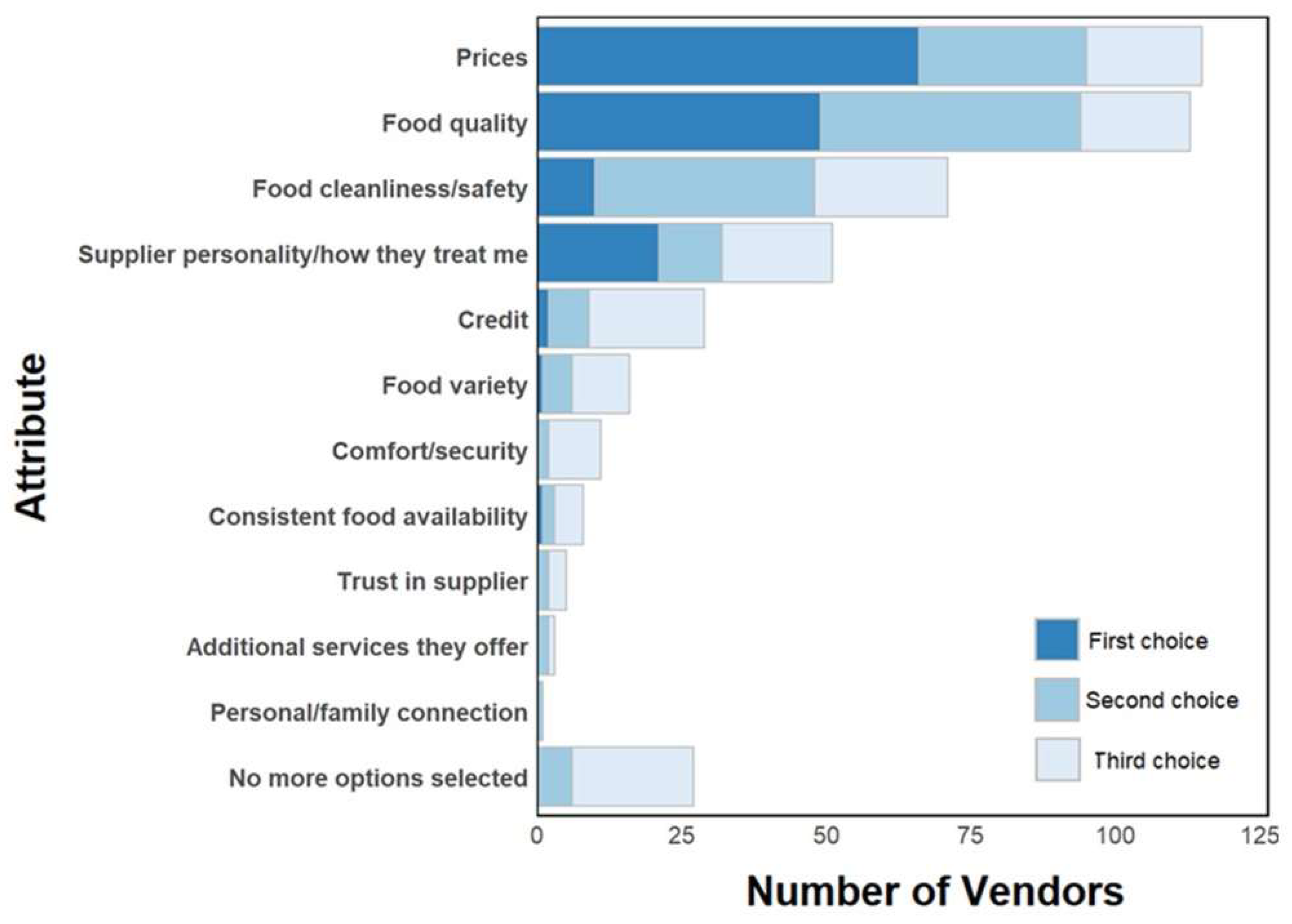

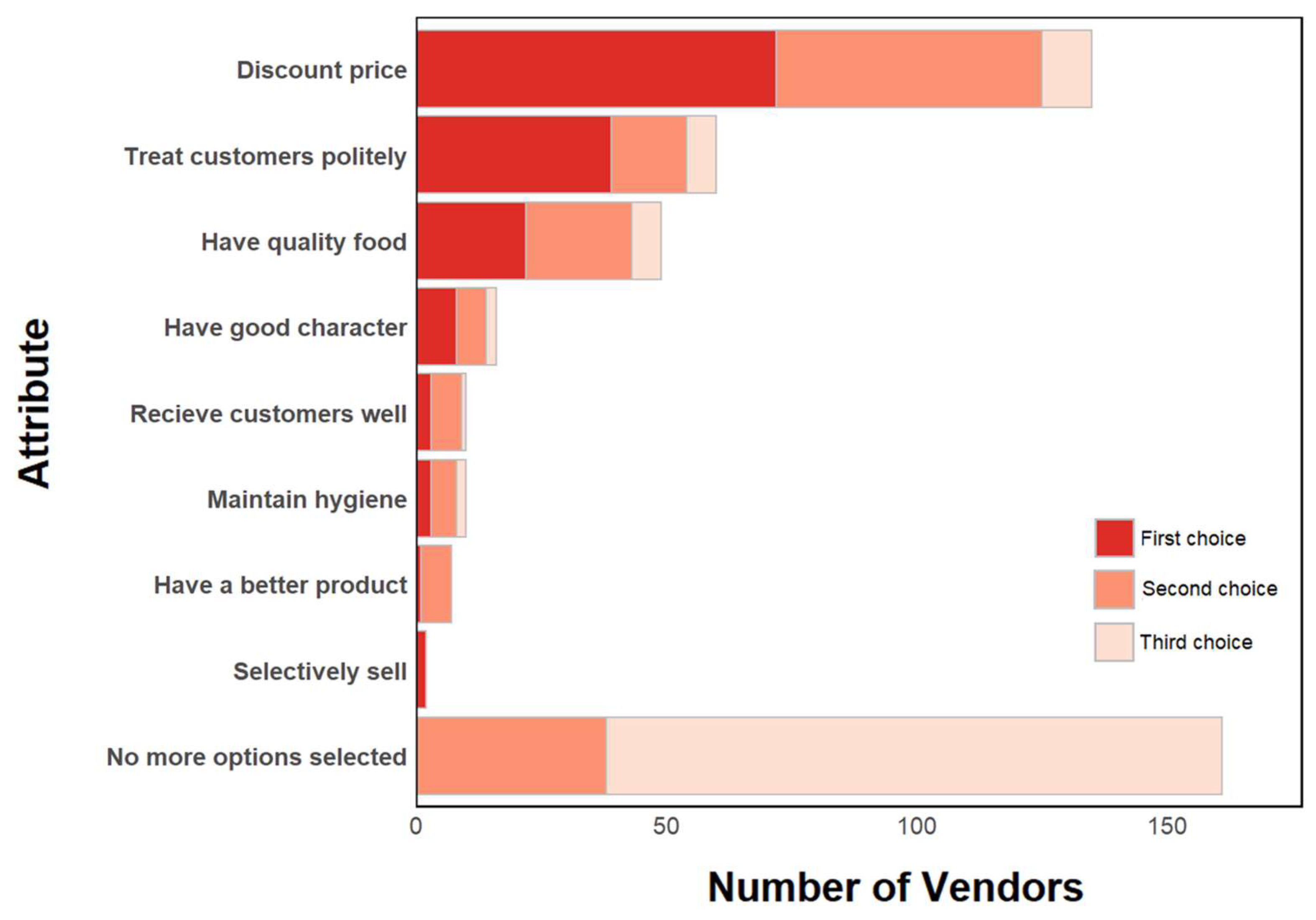

3.3.1. General Food Vending Practices

3.3.2. Food Safety Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitudes

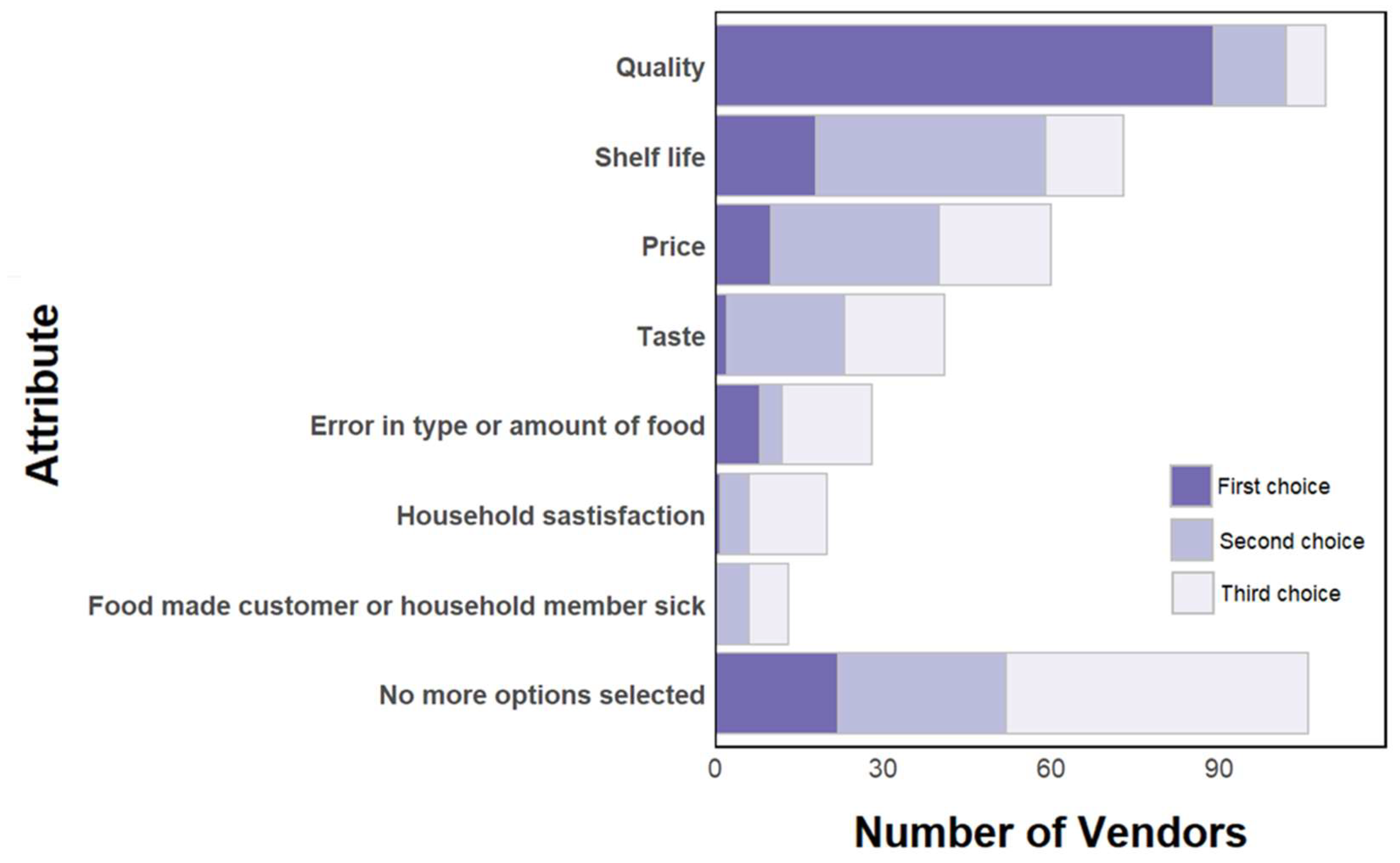

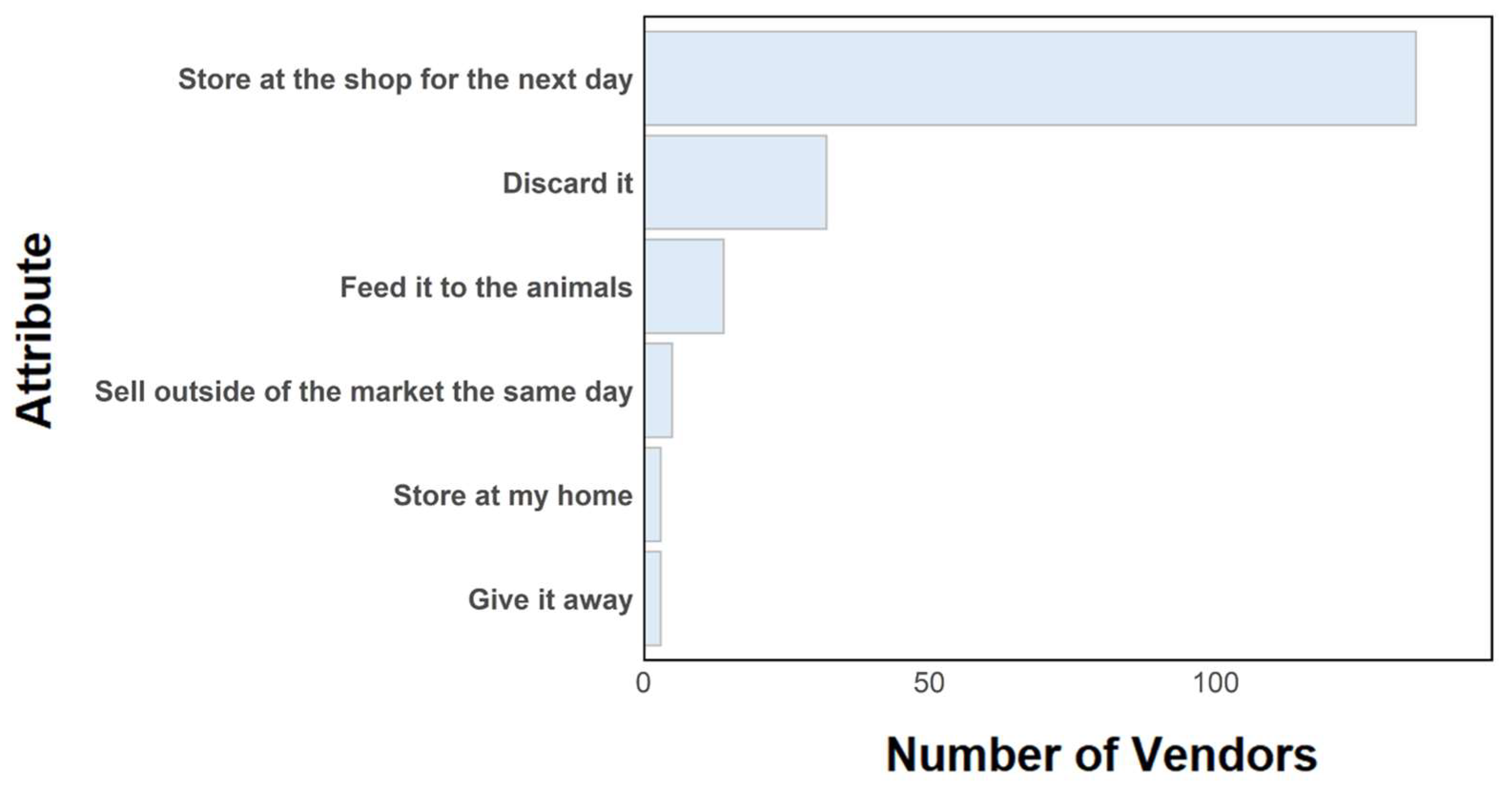

3.3.3. Food Safety Choices and Behaviors

3.3.4. Information Sources and Media Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Consumers’ purchase choice drivers (in this case, food quality and price), as well as vendors’ awareness of what consumers look for;

- Cues or signs of food safety used by consumers (and possibly vendors), and ideally tiers of desirability/acceptability; cues may be specific to food safety or merge with other overlapping characteristics (e.g. freshness, quality, healthiness);

- Vendor’s needs, grievances, and aspirations for their shop and the market;

- Competition and collaboration dynamics among vendors, also considering market governance and oversight from local public entities;

- Gender roles, and whether intervention pathways or content should differ between genders (and possibly other population segments);

- Current practices, especially those that could be reinforced, made easier, or slightly modified to potentially yield public health benefits;

- Costs of implementing new practices, and implications on food prices, in tandem with consumers’ willingness to pay for specific perceived benefits;

- Trusted sources of information, including media channels.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

References

- Jaffee S, Henson S, Unnevehr L, Grace D, Cassou E. The safe food imperative: Accelerating progress in low-and middle-income countries. The World Bank; 2018.

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Review of Food Safety Policy and Legislation in Ethiopia. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2022 Jan. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/Review%20of%20Food%20Safety%20Policy%20in%20Ethiopia.pdf.

- Grace, D. Food Safety in Low and Middle Income Countries. IJERPH. 2015;12: 10490–10507. [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, H. Review on food safety system: Ethiopian perspective. Afr J Food Sci. 2013;7: 431–440. [CrossRef]

- Havelaar AH, Kirk MD, Torgerson PR, Gibb HJ, Hald T, Lake RJ, et al. World Health Organization Global Estimates and Regional Comparisons of the Burden of Foodborne Disease in 2010. von Seidlein L, editor. PLoS Med. 2015;12: e1001923. [CrossRef]

- Roesel K, Grace D. Food safety and informal markets: Animal products in sub-Saharan Africa. Routledge; 2014.

- Nordhagen S, Hagos S, Gebremedhin G, Lee J. Vendor capacity and incentives to supply safer food: a perspective from urban Ethiopia. Food Sec. 2025 [cited 26 Mar 2025]. [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). EatSafe Learnings from Phase I Research in Hawassa, Ethiopia. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2023 Feb. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/EatSafe-Learnings-from-Phase-I-Research-in-Ethiopia.pdf.

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Food Safety Hazards and Risk Associated with Fresh Vegetables: Assessment from a Traditional Market in Southern Ethiopia. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2023. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/Food_Safety_Hazards_Risk_Fresh_Vegetables_%20Traditional_Market_Southern_Ethiopia.pdf.

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Literature Review on Foodborne Disease Hazards in Food and Beverages in Ethiopia. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2022 Mar. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/Literature%20Review%20on%20Foodborne%20Disease%20Hazards%20in%20Foods%20and%20Beverages%20in%20Ethiopia.pdf.

- Hsieh FY, Liu AA. Adequacy of sample size in health studies. Stanley Lemeshow, David W. Hosmer Jr., Janelle Klar and Stephen K. Lwanga published on behalf of WHO by Wiley, Chichester, 1990. No. of pages: xii + 233. Price:£D17.50. Statistics in Medicine. 1990;9: 1382–1382. [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2021.

- Team, RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. 2022. Available: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Poverty Probability Index. Ethiopia. In: PPI [Internet]. 2020 [cited 6 Oct 2022]. Available: https://www.povertyindex.org/country/ethiopia.

- Misra S, Li H, He J. Machine learning for subsurface characterization. Cambridge, MA: Gulf Professional Publishing, an imprint of Elsevier; 2020.

- Jaffee S, Henson S. Promoting Food Safety in the Informal Markets of Low and Middle-Income Countries: The Need for a Rethink. Food Protection Trends. 2024;44: 376–382.

- Rheinländer T, Olsen M, Bakang JA, Takyi H, Konradsen F, Samuelsen H. Keeping up appearances: perceptions of street food safety in urban Kumasi, Ghana. J Urban Health. 2008;85: 952–964. [CrossRef]

- Nordhagen S, Hagos S, Gebremedhin G, Lee J. Understanding consumer beliefs and choices related to food safety: a qualitative study in urban Ethiopia. Public Health Nutr. 27: e239. [CrossRef]

- Nordhagen S, Lee J, Onuigbo-Chatta N, Okoruwa A, Monterrosa E, Lambertini E, et al. “Sometimes You Get Good Ones, and Sometimes You Get Not-so-Good Ones”: Vendors’ and Consumers’ Strategies to Identify and Mitigate Food Safety Risks in Urban Nigeria. Foods. 2022;11: 201. [CrossRef]

- Isanovic S, Constantinides SV, Frongillo EA, Bhandari S, Samin S, Kenney E, et al. How Perspectives on Food Safety of Vendors and Consumers Translate into Food-Choice Behaviors in 6 African and Asian Countries. Curr Dev Nutr. 2023;7: 100015. [CrossRef]

- Leveraging Consumer Demand to Drive Food Safety Improvements in Traditional Markets: FTF EatSafe’s Research & Implementation Results. In: GAIN [Internet]. [cited 28 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/resources/reports-and-publications/leveraging-consumer-demand-drive-food-safety-improvements.

- Noor AYM, Toiba H, Setiawan B, Wahib Muhaimin A, Nurjannah N. Indonesian Consumers’ Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Certified Vegetables: A Choice-Based Conjoint Approach. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing. 2024;36: 617–642. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann V, Moser CM, Herrman TJ. Demand for Aflatoxin-Safe Maize in Kenya: Dynamic Response to Price and Advertising. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2021;103: 275–295. [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Sekyere E, Owusu V, Jordaan H. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for beef food safety assurance labels in the Kumasi Metropolis and Sunyani Municipality of Ghana. Food Control. 2014;46: 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Alimi BA, Oyeyinka AT, Olohungbebe LO. Socio-economic characteristics and willingness of consumers to pay for the safety of fura de nunu in Ilorin, Nigeria. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops & Foods. 2016;8: 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Wongprawmas R, Canavari M. Consumers’ willingness-to-pay for food safety labels in an emerging market: The case of fresh produce in Thailand. Food Policy. 2017;69: 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Alphonce R, Alfnes F. Consumer willingness to pay for food safety in Tanzania: an incentive-aligned conjoint analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2012;36: 394–400. [CrossRef]

- Alimi BA, Workneh TS. Consumer awareness and willingness to pay for safety of street foods in developing countries: a review. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2016;40: 242–248. [CrossRef]

- Vuong H, Pannell D, Schilizzi S, Burton M. Vietnamese consumers’ willingness to pay for improved food safety for vegetables and pork. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 2024;68: 948–972. [CrossRef]

- Zhong S, Werner C. The hidden strength of small business: Social networks and wet market vendors in China. Economic Anthropology. 2025;12: e12323. [CrossRef]

- Nordhagen S, Lee J, Monterrosa E, Onuigbo-Chatta N, Okoruwa A, Lambertini E, et al. Where supply and demand meet: how consumer and vendor interactions create a market, a Nigerian example. Food Sec. 2023 [cited 8 Sep 2023]. [CrossRef]

- Osafo R, Balali GI, Amissah-Reynolds PK, Gyapong F, Addy R, Nyarko AA, et al. Microbial and Parasitic Contamination of Vegetables in Developing Countries and Their Food Safety Guidelines. Journal of Food Quality. 2022;2022: e4141914. [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kwasi H, Mohindra A, Booth A, Laar A, Wanjohi M, Graham F, et al. Factors influencing dietary behaviours in urban food environments in Africa: a systematic mapping review. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23: 2584–2601. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF, editor. Children, food and nutrition. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2019.

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Food Safety Attitudes and Practices in Traditional Markets in Nigeria: A Quantitative Formative Assessment. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2022 Apr.

- Food Safety Perceptions and Practices in Ethiopia: A Focused Ethnographic Study. In: GAIN [Internet]. [cited 28 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/resources/reports-and-publications/food-safety-perceptions-and-practices-ethiopia-focused.

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Evaluation of Consumer and Vendor Behaviors in a Traditional Food Market in Hawassa, Ethiopia. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2022 Sep. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/Evaluation%20of%20Consumer%20and%20Vendor%20Behaviors%20in%20a%20Traditional%20Food%20Market%20in%20Hawassa%2C%20Ethiopia.pdf.

- Ghatak S, Srinivas K, Milton AAP, Priya GB, Das S, Lindahl JF. Limiting the spillover of zoonotic pathogens from traditional food markets in developing countries and a new market design for risk-proofing. Epidemiol Health. 2023;45: e2023097. [CrossRef]

- Lazaro J, Kapute F, Holm RH. Food safety policies and practices in public spaces: The urban water, sanitation, and hygiene environment for fresh fish sold from individual vendors in Mzuzu, Malawi. Food Science & Nutrition. 2019;7: 2986–2994. [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Qualitative Behavioral Research in Traditional Markets in Kebbi State, Nigeria. EatSafe: Evidence and Action Towards Safe, Nutritious Food; 2022 Jul. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/resources/reports-and-publications/qualitative-behavioral-research-traditional-food-markets-kebbi.

- Rapid Market Assessment Tool for Food Safety In Traditional Markets. In: GAIN [Internet]. [cited 28 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/resources/reports-and-publications/rapid-market-assessment-tool-food-safety-traditional-markets.

- Market Assessment Tools for Traditional Markets. In: GAIN [Internet]. [cited 28 Feb 2025]. Available: https://www.gainhealth.org/resources/reports-and-publications/market-assessment-tools-traditional-markets.

- USAID Advancing Nutrition. Methods, Tools, and Metrics for Evaluating Market Food Environments in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Arlington, VA, USA: USAID Advancing Nutrition; 2021.

- Turner C, Kalamatianou S, Drewnowski A, Kulkarni B, Kinra S, Kadiyala S. Food Environment Research in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Adv Nutr. 2020;11: 387–397. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | Demographics | |

|

Vendors (N=150) |

Consumers (N=150) |

||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Number of household residents | 5.1 (2) | 4.7 (2.1) | |

| Number of household residents <5 years of age | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.7) | |

| Age (years) | 30.5 (11) | 32 (10) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Sex | Men | 22 (15 %) | 52 (35 %) |

| Women | 128 (85 %) | 98 (65 %) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 109 (73 %) | 94 (63 %) |

| Not married | 32 (21 %) | 47 (31 %) | |

| Education1 | Divorced | 3 (2 %) | 4 (3 %) |

| Widowed | 6 (4 %) | 5 (3 %) | |

| Primary (0 - 4th Grade) | 32 (21 %) | 12 (8 %) | |

| Secondary (5th Grade - 12th grade) | 94 (63 %) | 78 (52 %) | |

| Post-secondary | 5 (3 %) | 44 (29 %) | |

| Post-secondary (tvet)2 | 4 (3 %) | 9 (6 %) | |

| Never attended school (illiterate) | 12 (8 %) | 3 (2 %) | |

| Language3 | Amharic | 87 (58 %) | 118 (79 %) |

| Sidama | 6 (4 %) | 12 (8 %) | |

| Wolayita | 55 (37 %) | 16 (11 %) | |

| Responses | Responses, by Gender | |||

| Foods1 | N | % 1 |

Men N (%) 2 |

Women N (%) 2 |

| Tomatoes | 139 | 93% | 49 (35%) | 90 (65%) |

| Leafy greens | 126 | 84% | 38 (30%) | 88 (70%) |

| Roots/tubers | 80 | 53% | 26 (33%) | 54 (68%) |

| Legumes | 66 | 44% | 19 (29%) | 47 (71%) |

| Eggs | 25 | 17% | 7 (28%) | 18 (72%) |

| Poultry | 21 | 14% | 6 (29%) | 15 (71%) |

| Grains | 17 | 11% | 1 (6%) | 16 (94%) |

| Milk or Dairy Products | 9 | 6% | 0 (0%) | 9 (6%) |

| Perception | Agreement | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| People get sick from eating kale | 19% | 55% | 10% | 15% | 1% |

| People get sick from eating lettuce | 15% | 61% | 11% | 13% | 1% |

| People get sick from eating tomatoes | 15% | 47% | 13% | 23% | 2% |

| Food safety differs between vendors | 3% | 10% | 11% | 65% | 10% |

| Trust that vendors sell safe food | 3% | 15% | 10% | 63% | 9% |

| Prefer to buy from vendors that have a food safety certification or license (if available) | 6% | 28% | 5% | 49% | 13% |

| Media | Responses | Responses, by Gender | ||

| N | % 1 | Men, N (%) 2 | Women, N (%) 2 | |

| Medical professional (doctor/nurse) | 100 | 67% | 34 (34%) | 66 (66%) |

| Friends or family | 94 | 63% | 35 (37%) | 59 (63%) |

| Food packaging / labels | 71 | 47% | 27 (38%) | 44 (62%) |

| Experts on radio or TV | 50 | 33% | 22 (44%) | 28 (56%) |

| Internet / social media | 44 | 29% | 16 (36%) | 28 (64%) |

| Journalists (newspaper) / show hosts (TV/radio) | 24 | 16% | 12 (50%) | 12 (50%) |

| Local religious leader | 15 | 10% | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) |

| A famous person you like | 9 | 6% | 6 (67%) | 3 (33%) |

| Government agencies | 4 | 3% | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) |

| Perception | Agreement | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Can find suppliers that sell high quality foods | 2% | 4% | 3% | 66% | 25% |

| Knowing how to choose safe foods | 1% | 1% | 1% | 65% | 33% |

| Will spend a bit more time selecting safer foods | 1% | 3% | 4% | 62% | 31% |

| Will spend a bit more money selecting safer foods | 0% | 2% | 3% | 62% | 33% |

| Perception | Agreement | ||||

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither1 | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| Proud of the quality of the food sold | 2% | 1% | 1% | 58% | 39% |

| Satisfied with shop operations | 3% | 10% | 8% | 52% | 27% |

| Rules for preserving food quality/safety exist | 15% | 21% | 10% | 45% | 9% |

| Rules for keeping the shop clean exist | 14% | 23% | 7% | 45% | 11% |

| It is sometimes difficult to keep the shop clean | 13% | 35% | 3% | 39% | 11% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).