Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

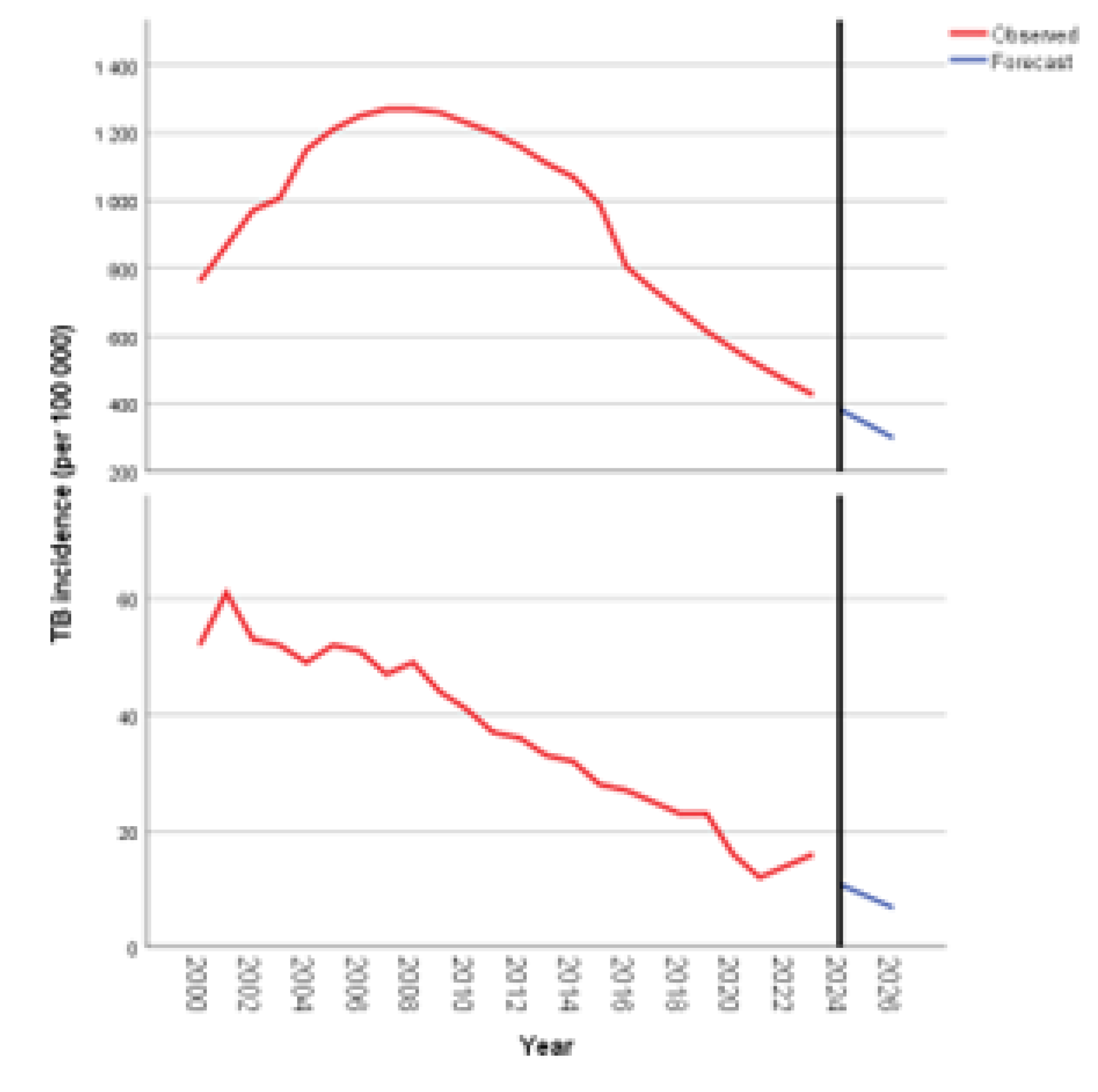

Background: Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health threat, with burdens distributed unevenly across regions. South Africa continues to record some of the world’s highest TB incidence and mortality rates, while Bulgaria—although a low-burden country has shown stagnant or rising mortality among vulnerable groups. Comparing these contrasting settings offers insight into how epidemiological, socio-economic, and health system factors shape TB outcomes. Objective: This study compares TB incidence and mortality trends in South Africa and Bulgaria from 2000 to 2023 and examines how HIV prevalence, migration, poverty, ageing, incarceration, health system performance, and underreporting influence TB dynamics. Methods: A narrative comparative analysis drawing on WHO Global TB Reports, peer-reviewed literature, and demographic and system indicators was conducted across four policy-aligned periods (2000–2009, 2010–2015, 2016–2020, 2021–2023). Results: South Africa experienced a sharp rise in TB incidence in the early 2000s, largely driven by the HIV epidemic and system bottlenecks. Incidence fell substantially after 2010 following ART expansion, GeneXpert implementation, and increased programmatic investment. In Bulgaria, TB incidence steadily declined, yet mortality remains disproportionately high due to underdiagnosis, population ageing, socioeconomic vulnerability, and surveillance gaps. Conclusion: Despite differing epidemiological profiles, both countries show how TB persists at the nexus of social inequity and system performance. Strengthened, equity-focused strategies are needed to improve early diagnosis, treatment outcomes, and progress toward TB elimination.

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Country-Specific Trends in TB Incidence and TB Mortality

4.1. TB Incidence and TB Mortality (2000-2023)

4.2. Time-Series Analysis

4.2.1. Absolute Change

4.2.2. Dynamic Index

4.2.3. Growth Rate

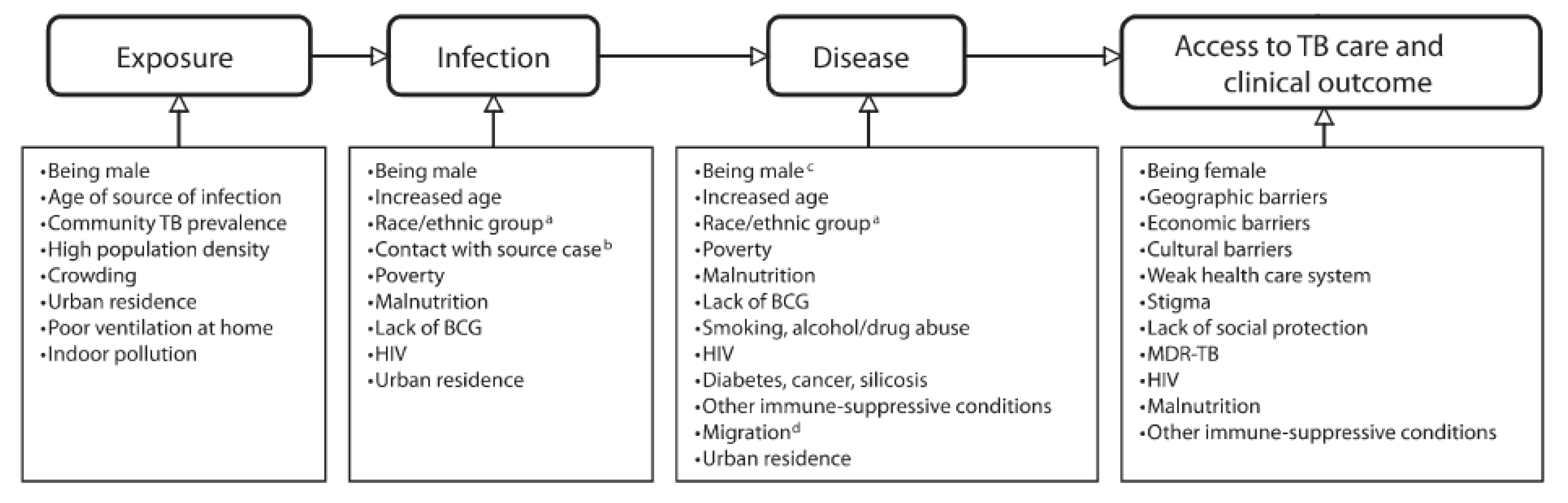

5. Social Determinants of Tuberculosis

| Year | Income (GDP per capita in USD) | Poverty ratio at $2.15 a day (% population) | % population below the national poverty line | Unemployment rate (%) | UHC service coverage index | Year | Income (GDP per capita in USD) | Poverty ratio at $2.15 a day (% population) | % population below the national poverty line | Unemployment rate (%) | UHC service coverage index |

| Republic of South Africa | |||||||||||

| 2000 | 3220 | 36.8 | 53.0 | 19.84 | 43 | 2012 | 8080 | n/a | 21.79 | ||

| 2001 | 2850 | 48.7 | 57.0 | 19.73 | 2013 | 7330 | n/a | 22.04 | |||

| 2002 | 2690 | 57.3 | 48.5 | 19.66 | 2014 | 6860 | 20.5 | 55.5 | 22.61 | ||

| 2003 | 4060 | 14 | 43.3 | 19.73 | 2015 | 6110 | n/a | 55.5 | 22.87 | 70 | |

| 2004 | 5220 | n/a | 55.0 | 19.63 | 2016 | 5650 | 21.5 | 55.5 | 24.02 | ||

| 2005 | 8840 | 28.3 | 66.6 | 19.56 | 51 | 2017 | 6620 | 21.5 | 55.5 | 23.99 | 71 |

| 2006 | 6080 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 19.43 | 2018 | 6910 | 47.6 | 55.5 | 24.22 | ||

| 2007 | 6590 | n/a | 47.6 | 19.39 | 2019 | 6530 | 48.4 | 55.5 | 25.54 | 71 | |

| 2008 | 6180 | 62.4 | 62.1 | 19.51 | 2020 | 5580 | 18.9 | 55.5 | 24.34 | 71 | |

| 2009 | 6370 | n/a | 39.0 | 20.51 | 2021 | 6840 | 6.3 | 50.0 | 28.77 | 71 | |

| 2010 | 7970 | 18 | 53.2 | 23.18 | 63 | 2022 | 6520 | 21.5 | 56.8 | 28.84 | |

| 2011 | 8850 | 14 | 53.2 | 21.42 | 2023 | 6020 | 21.5 | 55.5 | 27.99 | 79 | |

| Bulgaria | |||||||||||

| 2000 | 1621 | 7.9 | 16.22 | 56 | 2012 | 7430 | 2.3 | 21.2 | 12.27 | ||

| 2001 | 1770 | 7.9 | 17.3 | 19.92 | 2013 | 7690 | 1.8 | 21.0 | 12.94 | ||

| 2002 | 2090 | 7.9 | 18.11 | 2014 | 7910 | 1.7 | 21.8 | 11.42 | |||

| 2003 | 2720 | 14 | 20.6 | 13.73 | 2015 | 7080 | 3.4 | 22.0 | 9.14 | 70 | |

| 2004 | 3390 | 10 | 21.7 | 12.04 | 2016 | 7570 | 2 | 22.9 | 7.58 | ||

| 2005 | 3900 | n/a | 22.0 | 10.08 | 61 | 2017 | 8380 | 1.4 | 23.4 | 6.16 | 72 |

| 2006 | 4520 | 5.8 | 28.5 | 8.95 | 2018 | 9440 | 0.9 | 22.0 | 5.21 | ||

| 2007 | 5890 | 1.8 | 16.0 | 6.88 | 2019 | 9840 | 0.9 | 23.8 | 4.23 | 76 | |

| 2008 | 7270 | 1.3 | 20.6 | 5.61 | 2020 | 10200 | 0.2 | 22.1 | 5.13 | 73 | |

| 2009 | 6990 | 1.3 | 20.7 | 6.82 | 2021 | 12270 | 0.7 | 22.9 | 5.27 | 73 | |

| 2010 | 6860 | 2 | 22.3 | 10.28 | 65 | 2022 | 13640 | 9.0 | 20.6 | 4.27 | |

| 2011 | 7860 | 2.5 | 21.2 | 11.26 | 2023 | 15890 | 0.7 | 30.3 | 4.30 | ||

5.1. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Its Association with TB Outcomes

5.2. Poverty and TB Outcomes

5.3. Income and TB Outcomes

5.4. Unemployment Rate and TB

5.5. UHC SCI and TB Outcomes

6. Discussion

7. Policy Implications and Recommendations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- African Development Bank Group. South Africa Economic Outlook. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/south-africa/south-africa-economic-outlook (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Barberis, I.; Bragazzi, N. L.; Galluzzo, L.; Martini, M. The History of Tuberculosis: From the First Historical Records to the Isolation of Koch’s Bacillus. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2017, 58(1), E9–E12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, A.; Bhargava, M.; Pai, M. Tuberculosis: A Biosocial Problem That Requires Biosocial Solutions. Lancet 2024, 403, 2467–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabrovska, N.; Spasova, A.; Galacheva, A.; Kostadinov, D.; Yanev, N.; Milanov, V.; Gabrovski, K.; Velizarova, S. Tuberculosis in Adolescents in Bulgaria for a Three-Year Period: 2018–2020. Children 2022, 9, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, H. M.; Ehrlich, R.; Somdyala, N.; et al. Stigma Relating to Tuberculosis Infection Prevention and Control Implementation in Rural Health Facilities in South Africa—A Qualitative Study Outlining Opportunities for Mitigation. BMC Glob. Public Health 2024, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colema, C.; Maughan, S. The Road to UHC: Progress in South Africa’s Journey to Universal Health Coverage; Rural Health Advocacy Project: Johannesburg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cramm, J. M.; Koolman, X.; Møller, V.; Nieboer, A. P. Socio-Economic Status and Self-Reported Tuberculosis: A Multilevel Analysis in a Low-Income Township in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J. Public Health Afr. 2011, 2(2), e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.; Gray, A.; Cois, A.; Ndlovu, N.; Massyn, N.; Boerma, T. Is South Africa Closing the Health Gaps between Districts? Monitoring Progress towards Universal Health Service Coverage with Routine Facility Data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlatu, N.; Longo-Mbenza, B.; Apalata, T. Predictors of Tuberculosis Incidence and the Effects of Multiple Deprivation Indices on Tuberculosis Management in OR Tambo District over a 5-Year Period. PLoS One 2022, 17(3), e0264811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T. N.; Varleva, T.; Zamfirova, M.; Tyufekchieva, M.; Keshelava, A.; Hristov, K.; et al. Strategic Investment in Tuberculosis Control in the Republic of Bulgaria. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlinger, S.; Stracker, N.; Hanrahan, C.; Nonyane, B. A. S.; Mmolawa, L.; Tampi, R.; et al. Tuberculosis Patients with Higher Levels of Poverty Face Equal or Greater Costs of Illness. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2019, 23(11), 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Economy: Bulgaria Country Profile 2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fenta, M. D.; Ogundijo, O. A.; Warsame, A. A. A.; et al. Facilitators and Barriers to Tuberculosis Active Case Findings in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M. R. L.; Bonfim, R. O.; Bossonario, P. A.; Maurin, V. P.; Valença, A. B. M.; Abreu, P. D.; et al. Social Protection as a Right of People Affected by Tuberculosis: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, J. R.; Boccia, D.; Evans, C. A.; Adato, M.; Petticrew, M.; Porter, J. D. H. The Social Determinants of Tuberculosis: From Evidence to Action. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101(4), 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaca, A.; Malinga, T.; Iwu-Jaja, C. J.; Nnaji, C. A.; Okeibunor, J. C.; Kamuya, D.; Wiysonge, C. S. Strengthening the Health System as a Strategy to Achieving a Universal Health Coverage in Underprivileged Communities in Africa: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19(1), 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katende-Kyenda, L. N. Determinants of Non-Adherence to Anti-Tuberculosis Treatment in a Public Primary Healthcare in South Africa: Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh-Brown, M. R.; Sumner, T.; Sweeney, S.; Vassall, A.; Jensen, H. T. Estimating the Health and Macroeconomic Burdens of Tuberculosis in India, 2021-2040: A Fully Integrated Modelling Study. PLoS Med. 2024, 21(12), e1004491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lienhardt, C. From Exposure to Disease: The Role of Environmental Factors in Susceptibility to and Development of Tuberculosis. Epidemiol. Rev. 2001, 23(2), 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinjenko, S.; Magwood, O.; Wu, S.; Wei, X. Burden of Tuberculosis among Vulnerable Populations Worldwide: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23(12), 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Making Health a Right for All: Universal Health Coverage and Tuberculosis: Discussion Paper. March 2014.

- Medina-Marino, A.; de Vos, L.; Daniels, J. Social Isolation, Social Exclusion, and Access to Mental and Tangible Resources: Mapping the Gendered Impact of Tuberculosis-Related Stigma among Men and Women Living with Tuberculosis in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Glob. Public Health 2025, 3, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. National Tuberculosis Control Programme (NTP) in Bulgaria. 2021-2025. [Google Scholar]

- Musilová, B. The Long Road to Inclusion: Factors Influencing Persistent Marginalization of Roma in Slovakia through the Lens of Public Policy. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Nalugwa, T.; Annerstedt, K. S.; Nabwire, S.; West, N. S.; Kadota, J. L.; Atkins, S.; et al. Identifying Mechanisms by Which Social Determinants of Health Impact TB Diagnostic Evaluation Uptake in Uganda: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical Institute. Poverty and Social Inclusion Indicators in Bulgaria.

- NDoH; Republic of South Africa. Policy Dialogue on Universal Health Coverage in South Africa, December 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Policy-Dialogue-Report.pdf.

- NDoH; Republic of South Africa. National Health Insurance for South Africa: Towards Universal Health Coverage, Version 40; Department of Health: Pretoria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NDoH; Republic of South Africa. National TB Recovery Plan 4.0, April 2025; Pretoria. Available online: https://www.health.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/TB-Recovery-Plan-4_final_250526.pdf.

- Nguyen, T. A.; Teo, A. K. J.; Zhao, Y.; Quelapio, M.; Hill, J.; Morishita, F.; Marais, B. J.; Marks, G. B. Population-Wide Active Case Finding as a Strategy to End TB. Lancet Reg. Health–West. Pac 2024, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhassengo, P. P. The TB-Poverty Cycle: Dynamics, Determinants, and Consequences of Economic Hardship Faced by People with TB in Mozambique. Doctoral Dissertation, Karolinska Institutet, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ntuli, T. T. Socio-Economic Risk Factors for Acquired Multi-Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Among Tuberculosis Patients in South Africa, Tshwane Health District: A Retrospective Study; University of Johannesburg: South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski, G.; Dąbrowska, A.; Pilaczyńska-Cemel, M.; Krawiecka, D. Unemployment in TB Patients – Ten-Year Observation at Regional Center of Pulmonology in Bydgoszcz, Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2014, 20, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sacks, E.; Schleiff, M.; Were, M.; Chowdhury, A. M.; Perry, H. B. Communities, Universal Health Coverage and Primary Health Care. Bull. World Health Organ. 2020, 98(11), 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanchev, K. Administrative Unfairness: The Case of Roma in Bulgaria. ПУБЛИЧНИ ПОЛИТИКИ. bg 2021, 12(2), 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, H.; Bozzola, M.; Ravetti, C. Tuberculosis and Labour Market Participation: Evidence from South Africa. South. Afr. J. Econ. 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Situation Analysis of Children and Adolescents in South Africa 2024; UNICEF for Every Child: Pretoria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vanleeuw, L.; Zembe-Mkabile, W.; Atkins, S. I'm Suffering for Food": Food Insecurity and Access to Social Protection for TB Patients and Their Households in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One 2022, 17(4), e0266356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walt, M.; Moyo, S. The First National TB Prevalence Survey | South Africa 2018.

- WHO; Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; WHO Press: Geneva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; World Bank Group; OECD. Tracking Universal Health Coverage 2021: Global Monitoring Report; WHO: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; WHO Press: Geneva, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Country Classifications by Income Level for 2024-2025. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/world-bank-country-classifications-by-income-level-for-2024-2025.

- World Bank. Database: Indicators. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator?tab=all.

- World Health Organization. Universal Health Coverage, 2025. Available online: https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/uhc2030/Documents/UN_HLM_2023/Action_Agenda_2023/UHC_Action_Agenda_long_2023.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Zumla, A.; Sahu, S.; Ditiu, L.; Singh, U.; Park, Y. J.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Osei-Wusu, S.; Asogun, D.; Nyasulu, P.; Tembo, J.; Kapata, N.; Alyaqoubi, F.; Maani, A. A.; Blumberg, L.; Zumla, A.; Ahmed, R.; Go, U.; Hui, D. S.; Goletti, D.; Petersen, E. Inequities Underlie the Alarming Resurgence of Tuberculosis as the World's Top Cause of Death from an Infectious Disease—Breaking the Silence and Addressing the Underlying Root Causes. IJID Reg. 2025, 14 Suppl 2, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Incidence per 100 000 | Mortality per 100,000 population | Year | Incidence per 100 000 | Mortality per 100,000 population |

| SA | |||||

| 2000 | 762 | 95 | 2012 | 1160 | 93 |

| 2001 | 867 | 113 | 2013 | 1110 | 77 |

| 2002 | 971 | 132 | 2014 | 1070 | 71 |

| 2003 | 1007 | 146 | 2015 | 988 | 61 |

| 2004 | 1150 | 150 | 2016 | 805 | 55 |

| 2005 | 1210 | 155 | 2017 | 738 | 53 |

| 2006 | 1250 | 160 | 2018 | 677 | 49 |

| 2007 | 1270 | 157 | 2019 | 615 | 45 |

| 2008 | 1270 | 155 | 2020 | 562 | 34 |

| 2009 | 1260 | 138 | 2021 | 513 | n/a |

| 2010 | 1230 | 124 | 2022 | 468 | n/a |

| 2011 | 1200 | 107 | 2023 | 427 | n/a |

| Bulgaria | |||||

| 2000 | 52 | 4 | 2012 | 36 | 2 |

| 2001 | 61 | 4 | 2013 | 33 | 2 |

| 2002 | 53 | 4 | 2014 | 32 | 2 |

| 2003 | 52 | 4 | 2015 | 28 | 2 |

| 2004 | 49 | 4 | 2016 | 27 | 2 |

| 2005 | 52 | 4 | 2017 | 25 | 1 |

| 2006 | 51 | 4 | 2018 | 23 | 1 |

| 2007 | 47 | 4 | 2019 | 23 | 1 |

| 2008 | 49 | 3 | 2020 | 16 | 1 |

| 2009 | 44 | 3 | 2021 | 12 | 1 |

| 2010 | 41 | 3 | 2022 | 14 | 1 |

| 2011 | 37 | 2 | 2023 | 16 | 1 |

|

Year x (t) |

Absolute levels(yi) |

Absolute change ∆i/0 (with fixed base, 2000) |

Absolute change ∆i/i-1 (with the base chained) |

Dynamic index(with fixed base, 2000) | Dynamic index (with the base chained) | Growth rate Ri/0(with fixed base, 2000) | Growth rate Ri/i-1 (with the base chained) |

| Republic of South Africa | |||||||

| 2000 | 762 | – | – | 100.0 | 100.0 | – | – |

| 2001 | 867 | 105 | 105 | 113.8 | 113.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 |

| 2002 | 971 | 209 | 104 | 127.4 | 111.9 | 27.4 | 11.9 |

| 2003 | 1007 | 245 | 36 | 132.2 | 103.7 | 32.2 | 3.7 |

| 2004 | 1150 | 388 | 143 | 150.9 | 114.2 | 50.9 | 14.2 |

| 2005 | 1210 | 448 | 60 | 158.8 | 105.2 | 58.8 | 5.2 |

| 2006 | 1250 | 488 | 40 | 164 | 103.3 | 64.0 | 3.3 |

| 2007 | 1270 | 508 | 20 | 166.7 | 101.6 | 66.7 | 1.6 |

| 2008 | 1270 | 508 | 0 | 166.7 | 100.0 | 66.7 | 0.0 |

| 2009 | 1260 | 498 | -10 | 165.4 | 99.2 | 65.4 | -0.8 |

| 2010 | 1230 | 468 | -30 | 161.4 | 97.6 | 61.4 | -2.4 |

| 2011 | 1200 | 438 | -30 | 157.5 | 97.6 | 57.5 | -2.4 |

| 2012 | 1160 | 398 | -40 | 152.2 | 96.7 | 52.2 | -3.3 |

| 2013 | 1110 | 348 | -50 | 145.7 | 95.7 | 45.7 | -4.3 |

| 2014 | 1070 | 308 | -40 | 140.4 | 96.4 | 40.4 | -3.6 |

| 2015 | 988 | 226 | -82 | 129.7 | 92.3 | 29.7 | -7.7 |

| 2016 | 805 | 43 | -183 | 105.6 | 81.5 | 5.6 | -18.5 |

| 2017 | 738 | -24 | -67 | 96.9 | 91.7 | -3.1 | -8.3 |

| 2018 | 677 | -85 | -61 | 88.8 | 91.7 | -11.2 | -8.3 |

| 2019 | 615 | -147 | -62 | 80.7 | 90.8 | -19.3 | -9.2 |

| 2020 | 562 | -200 | -53 | 73.8 | 91.4 | -26.2 | -8.7 |

| 2021 | 513 | -249 | -49 | 67.3 | 91.3 | -32.7 | -8.7 |

| 2022 | 468 | -294 | -45 | 61.4 | 91.2 | -38.6 | -8.8 |

| 2023 | 427 | -335 | -41 | 56 | 91.2 | -43.9 | -8.8 |

| Bulgaria | |||||||

| 2000 | 52 | – | – | 100.0 | 100.0 | – | – |

| 2001 | 61 | 9 | 9 | 117.3 | 117.3 | 17.3 | 17.3 |

| 2002 | 53 | 1 | -8 | 101.9 | 86.9 | 1.9 | -13.1 |

| 2003 | 52 | 0 | -1 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 0.0 | -1.9 |

| 2004 | 49 | -3 | -3 | 94.2 | 94.2 | -5.8 | -5.8 |

| 2005 | 52 | 0 | -3 | 100 | 106.1 | 0.0 | 6.1 |

| 2006 | 51 | -1 | -1 | 98.1 | 98.1 | -1.9 | -1.9 |

| 2007 | 47 | -5 | -4 | 90.4 | 92.2 | -9.6 | -7.8 |

| 2008 | 49 | -3 | 2 | 94.2 | 104.3 | -5.8 | 4.3 |

| 2009 | 44 | -8 | -5 | 84.6 | 89.8 | -15.4 | -10.2 |

| 2010 | 41 | -11 | -3 | 78.8 | 93.2 | -21.2 | -6.8 |

| 2011 | 37 | -15 | -4 | 71.2 | 90.2 | -28.8 | -9.8 |

| 2012 | 36 | -16 | -1 | 69.2 | 97.3 | -30.8 | -2.7 |

| 2013 | 33 | -19 | -3 | 63.5 | 91.7 | -36.5 | -8.3 |

| 2014 | 32 | -20 | -1 | 61.5 | 96.9 | -38.5 | -3.0 |

| 2015 | 28 | -24 | -4 | 53.8 | 87.5 | -46.2 | -12.5 |

| 2016 | 27 | -25 | -1 | 51.9 | 96.4 | -48.1 | -3.6 |

| 2017 | 25 | -27 | -2 | 48.1 | 92.5 | -51.9 | -7.4 |

| 2018 | 23 | -29 | -2 | 44.2 | 92.0 | -55.8 | -8.0 |

| 2019 | 23 | -29 | 0 | 44.2 | 100.0 | -55.8 | 0.0 |

| 2020 | 16 | -36 | -7 | 30.8 | 69.6 | -69.2 | -30.4 |

| 2021 | 12 | -40 | -4 | 23.1 | 75.0 | -76.9 | -25.0 |

| 2022 | 14 | -38 | 2 | 26.9 | 116.7 | -73.1 | 16.7 |

| 2023 | 16 | -36 | 2 | 30.8 | 114.3 | -69.2 | 14.3 |

| Republic of South Africa | Bulgaria | |

| Social determinant | TB incidence trend | |

| GDP per capita | r=-0.246, p=0.247, N=24 | r=-0.910*, p=0.001, N=24 |

| % Population below the national poverty line | r=0.674*, p=0.001, N=24 | r=0.378, p=0.083, N=24 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | r=0.805*, p=0.001, N=24 | r=0.723*, p=0.001, N=24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).