Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Sources

- World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Reports (2015-2022): We conducted systematic review of the annual WHO Global Tuberculosis Reports, extracting country-specific and regional data on TB incidence, prevalence, mortality, treatment outcomes, and programmatic indicators. These reports provided standardised metrics enabling cross-national and temporal comparisons.

-

Peer-reviewed literature: We performed a structured review of academic publications indexed in MEDLINE, Embase, and Global Health databases, utilizing the following search strategy:

- Primary search terms: "tuberculosis" OR "TB" AND "mortality" OR "death" OR "fatal outcome"

- Secondary terms: "risk factors", "determinants", "socioeconomic", "healthcare systems", "comorbidity"

- Inclusion criteria: Studies published between January 2000 and December 2022; English, Portuguese, or Spanish language; primary research or systematic reviews with quantitative outcomes

- Exclusion criteria: Case reports, non-human studies, studies without mortality outcomes

- Total studies identified: 1,782; After screening: 412; Included in final analysis: 203

- National tuberculosis programme data: We incorporated granular data from national TB programmes from eight high-burden countries (India, Indonesia, China, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and South Africa), collected between 2018-2022. These data provided detailed insights into subnational variations in TB epidemiology and programme performance.

- Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS): For analysis of socioeconomic correlates of TB outcomes, we utilised DHS data from 17 countries with high TB burdens conducted between 2015-2021, enabling examination of associations between household-level socioeconomic indicators and TB prevalence.

2.2. Analytical Framework

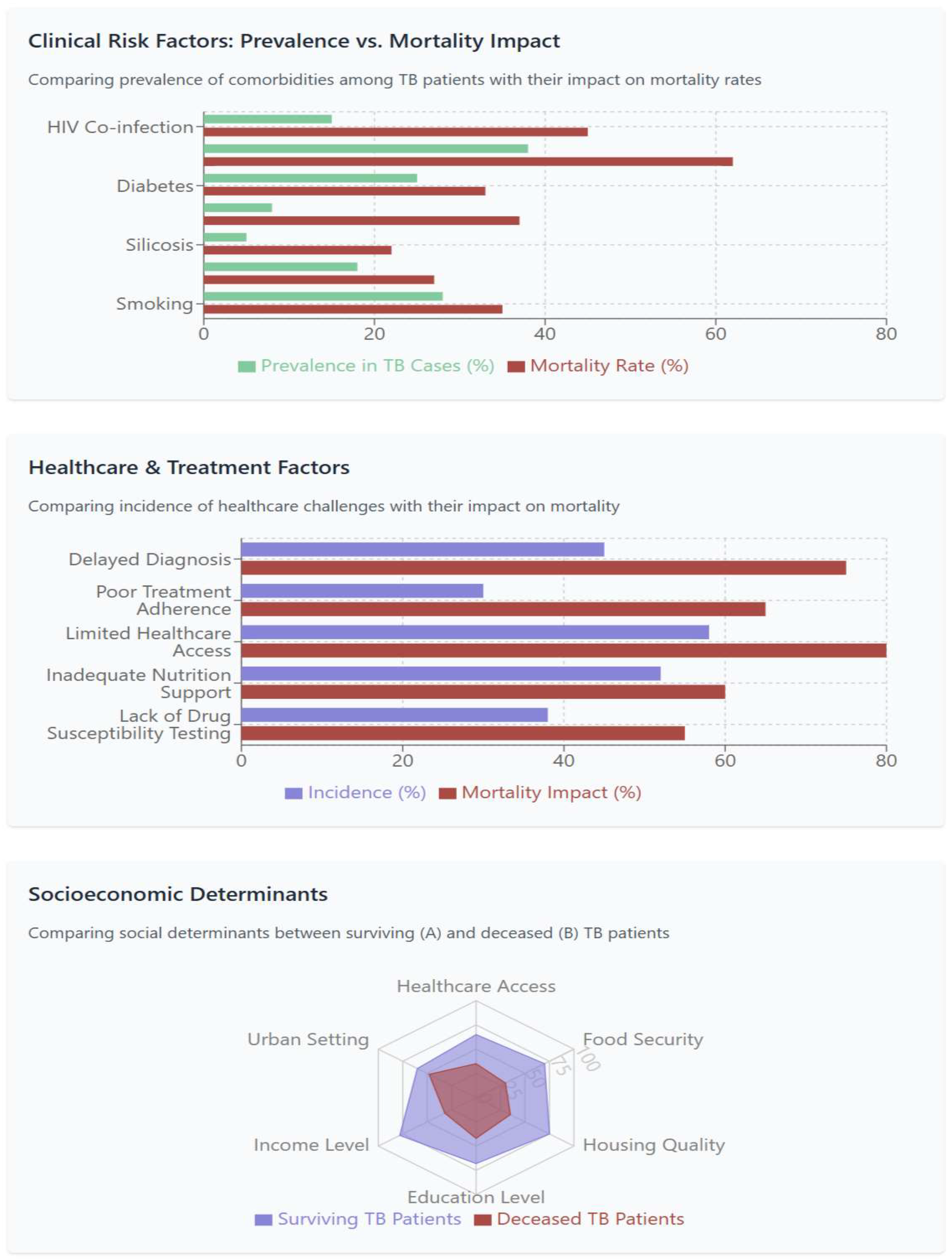

- Proximal risk factors: Including HIV co-infection, diabetes, malnutrition, smoking, alcohol use, and air pollution

- Healthcare system factors: Including access to diagnosis and treatment, quality of care, and health system resilience

- Socioeconomic determinants: Including income, education, housing, and food security

- Structural factors: Including governance, policy frameworks, and economic inequality

2.3. Statistical Analysis

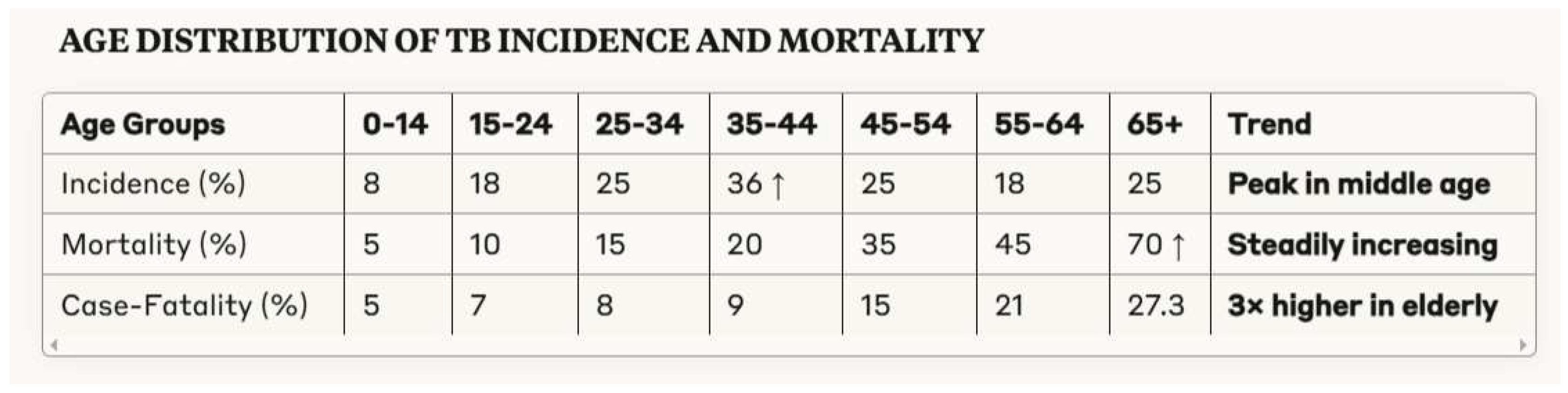

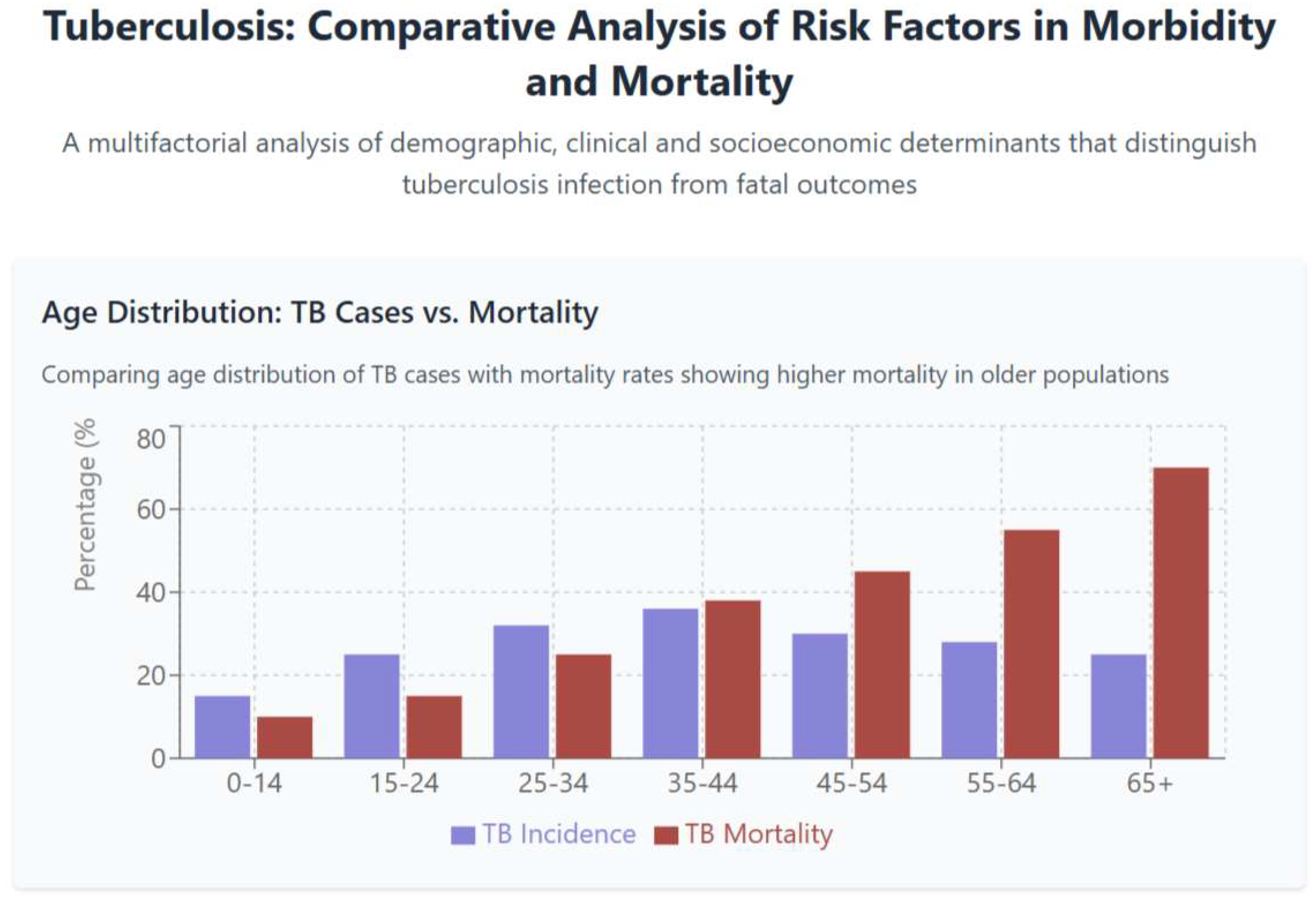

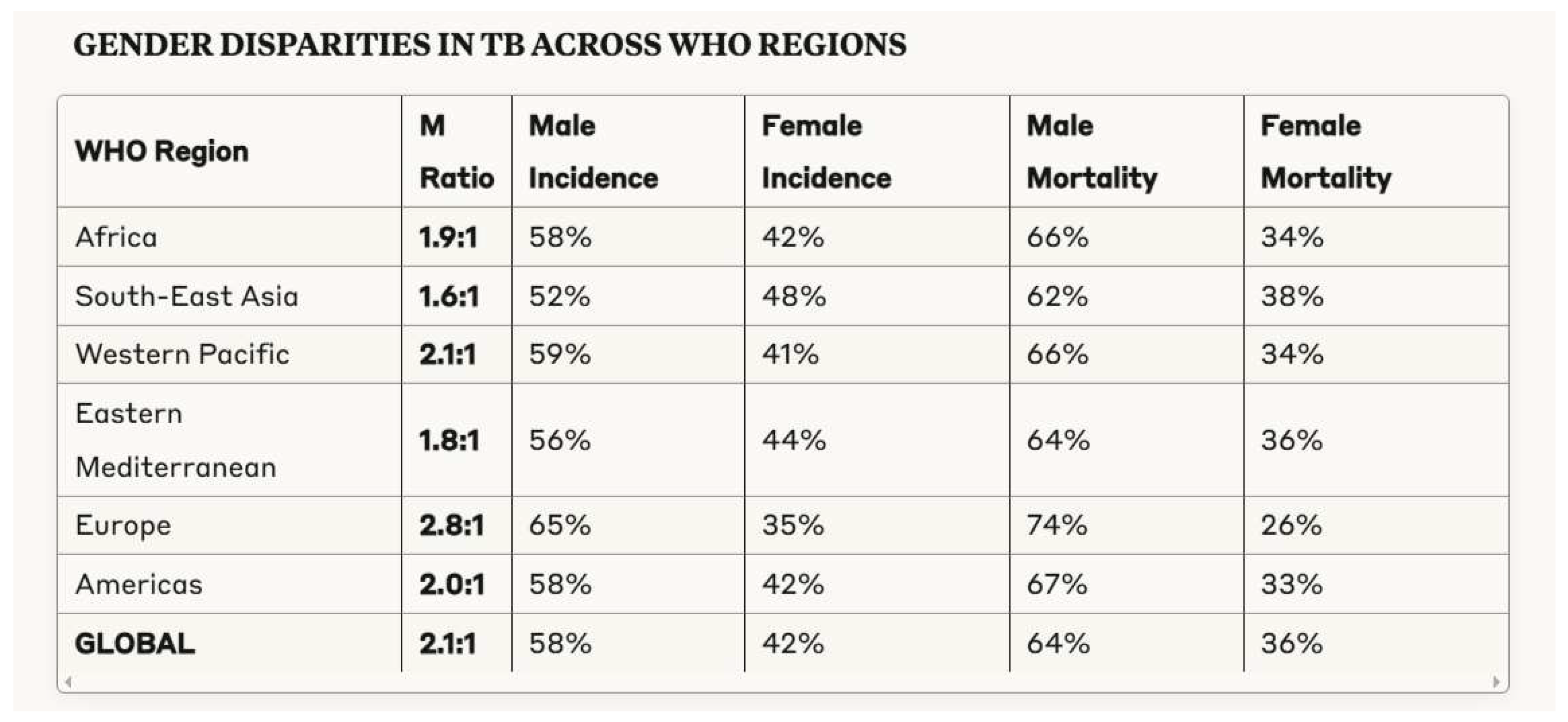

- Descriptive epidemiology: We calculated age-standardised and gender-stratified TB incidence and mortality rates, enabling identification of demographic patterns in disease burden. Direct standardization was performed using the WHO world standard population.

- Correlation analysis: Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to examine associations between TB mortality rates and various socioeconomic indicators, including GDP per capita, Gini coefficient, Human Development Index, and healthcare expenditure. These analyses were conducted at the national level using data from 135 countries with complete datasets for both TB mortality and socioeconomic indicators.

- Regression modelling: Multivariate regression models were developed to identify independent predictors of TB mortality at national level, with adjustment for potential confounding factors. Hierarchical regression models were constructed with structural factors at level 1, healthcare system factors at level 2, and proximal risk factors at level 3. This approach allowed assessment of direct effects and mediation pathways.

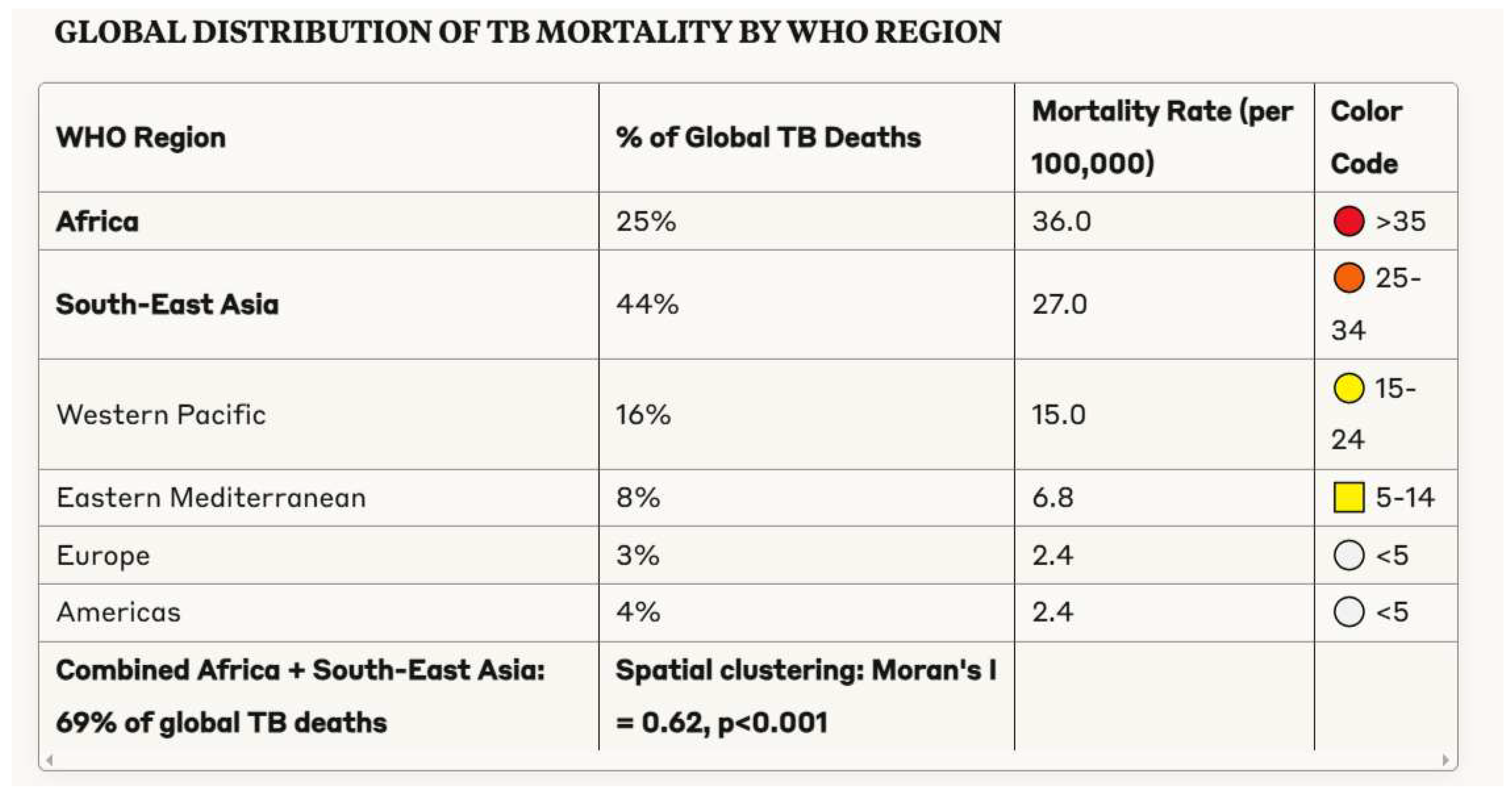

- Geospatial analysis: ArcGIS (version 10.8) was utilised to visualise geographical variations in TB burden and mortality, identifying spatial clusters and correlations with socioeconomic indicators. Spatial autocorrelation was assessed using Moran's I statistic, and hotspot analysis was performed using Getis-Ord Gi* statistic.

2.4. Limitations

- Data quality: The reliability and completeness of TB surveillance data varies substantially across settings, with potential underestimation of disease burden in countries with limited diagnostic capacity or incomplete vital registration systems.

- Ecological fallacy: Some analyses were conducted at national level, risking ecological fallacy when inferring individual-level relationships from aggregate data. We have been careful to distinguish between associations observed at population level versus individual level throughout our analysis.

- Temporality: Cross-sectional analyses limit causal inference regarding the relationship between socioeconomic factors and TB outcomes. We have therefore been careful to present these as associations rather than causal relationships, except where longitudinal data or natural experiments provide stronger evidence for causality.

- Unmeasured confounding: Despite comprehensive adjustment for known confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured variables may influence observed associations.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Patterns in Tuberculosis Morbidity and Mortality

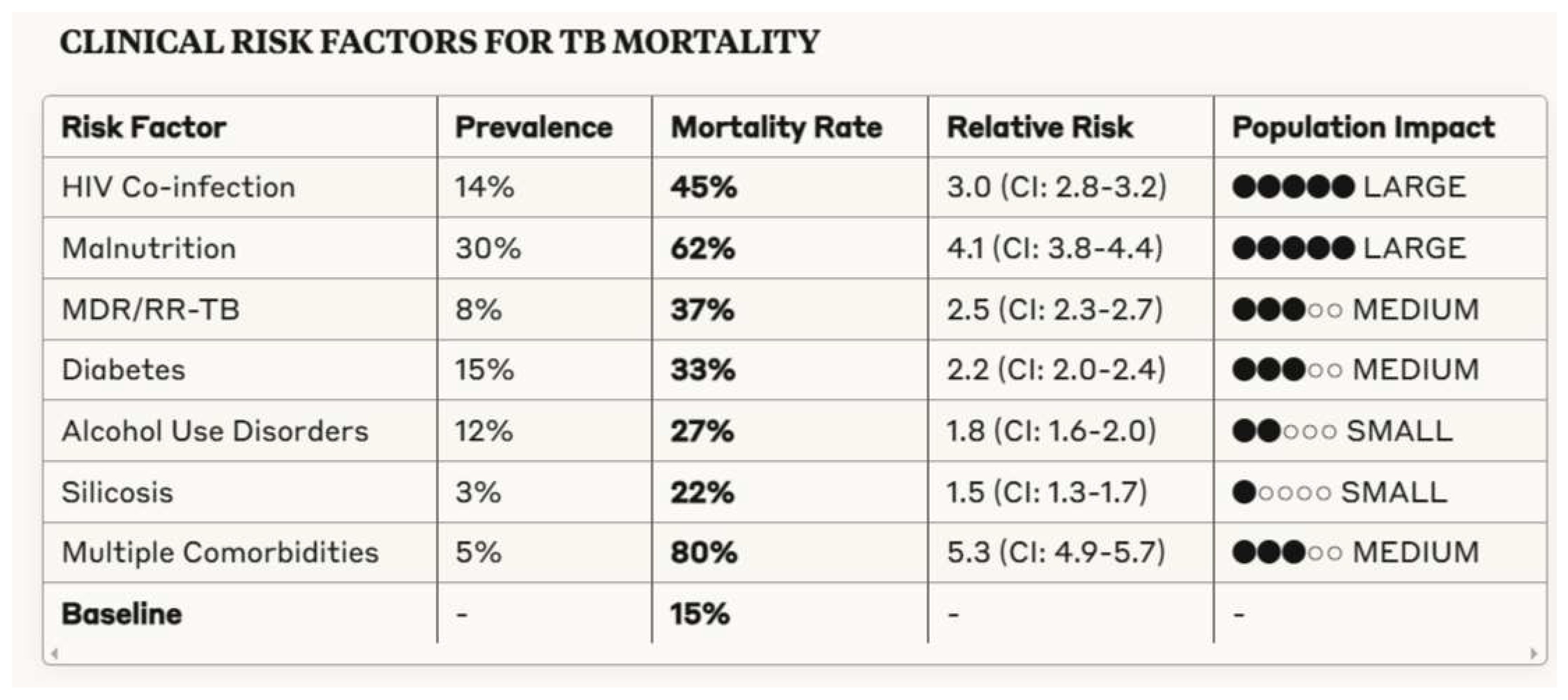

3.2. Clinical Determinants of Tuberculosis Outcomes

3.3. Healthcare System Factors Influencing Tuberculosis Outcomes

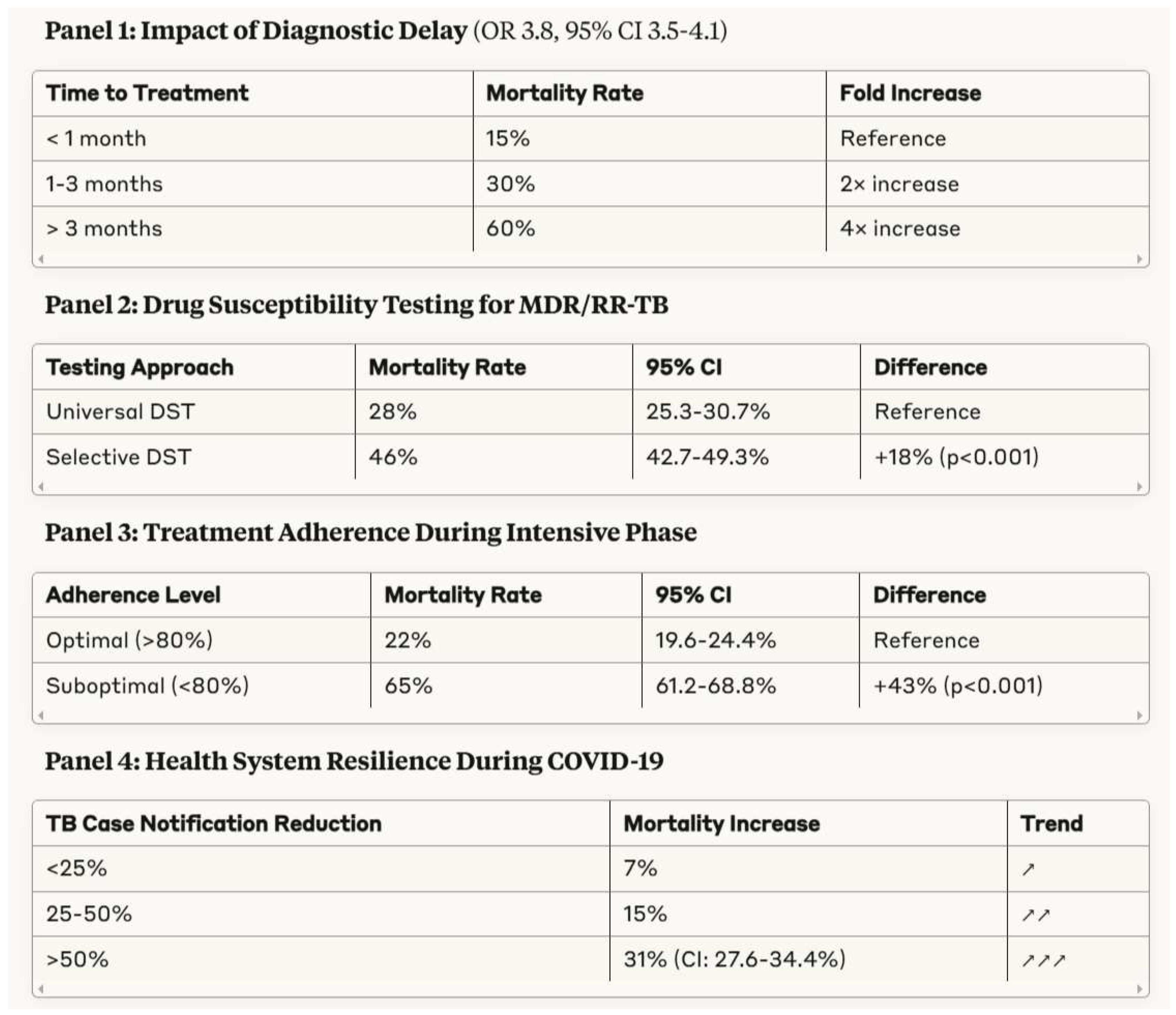

- Diagnostic Delay: Mortality progressively increases with time from symptom onset to treatment initiation (OR 3.8, 95% CI 3.5-4.1)

- Access to Drug Susceptibility Testing: Universal DST reduces MDR/RR-TB mortality by 18 percentage points compared to selective testing (28% vs. 46%, p<0.001)

- Treatment Adherence: Suboptimal adherence (<80% of doses) during intensive phase is associated with tripled mortality (65% vs. 22%, p<0.001)

- Health System Resilience: Countries with >50% reduction in TB notifications during COVID-19 saw 31% increase in mortality (95% CI: 27.6-34.4%)

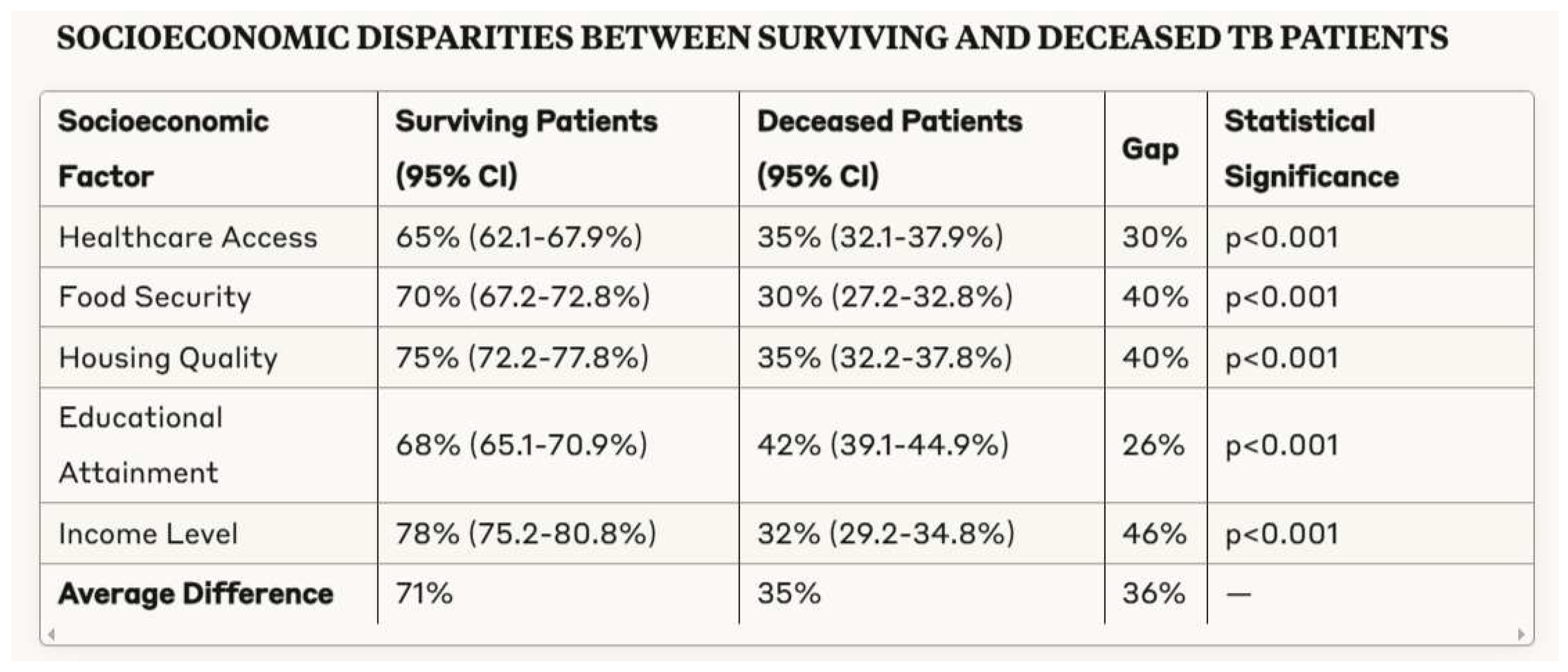

3.4. Socioeconomic Determinants of Tuberculosis Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Tuberculosis and Socioeconomic Development

4.2. Health System Strengthening for Tuberculosis Elimination

4.3. Addressing Social Determinants of Tuberculosis

4.4. Clinical Interventions and Potential Therapeutic Targets

4.5. Framework for Tuberculosis Elimination

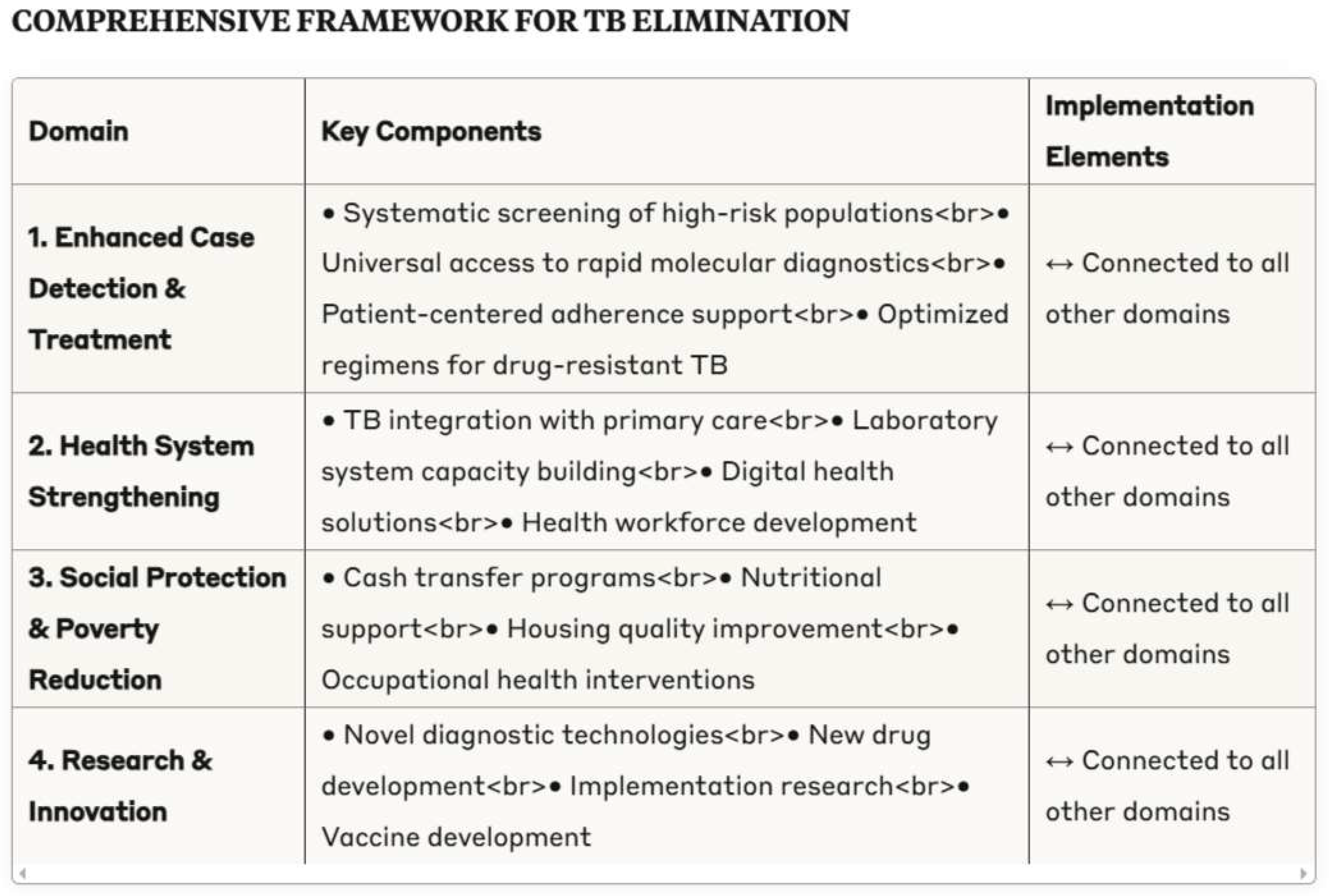

-

Enhanced case detection and treatment optimization

- ○

- Systematic screening of high-risk populations

- ○

- Universal access to rapid molecular diagnostics

- ○

- Patient-centered adherence support

- ○

- Optimized regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis

-

Health system strengthening

- ○

- Integration of tuberculosis services within primary care

- ○

- Laboratory system capacity building

- ○

- Digital health solutions for surveillance and patient support

- ○

- Health workforce development

-

Social protection and poverty reduction

- ○

- Cash transfer programmes for tuberculosis patients

- ○

- Nutritional support integrated with treatment

- ○

- Housing quality improvement in high-burden areas

- ○

- Occupational health interventions in high-risk industries

-

Research and innovation

- ○

- Novel diagnostic technologies with point-of-care potential

- ○

- New drug development targeting resistant strains

- ○

- Implementation research on service delivery models

- ○

- Vaccine development for prevention of infection and disease

5. Conclusion

- 5.

- Pronounced demographic disparities in tuberculosis mortality, with elderly individuals experiencing case-fatality rates nearly three times those of younger adults despite lower incidence

- 6.

- Significant clinical risk factors including HIV co-infection (RR 3.0), malnutrition, and drug resistance, with compounding effects when multiple comorbidities coexist

- 7.

- Critical healthcare system determinants including diagnostic delay (OR 3.8 for mortality), limited access to drug susceptibility testing, and treatment adherence challenges

- 8.

- Substantial socioeconomic gradients between surviving and deceased tuberculosis patients across multiple domains including healthcare access, food security, housing quality, and income level

- 9.

- Geographical concentration of tuberculosis mortality in specific regions and populations, suggesting benefit from targeted, intensive interventions

- Implementation research on optimal approaches to active case-finding in diverse settings

- Development and evaluation of integrated interventions addressing tuberculosis and comorbidities, particularly HIV and diabetes

- Prospective studies examining the impact of social protection programmes on tuberculosis outcomes

- Basic and translational research on novel therapeutic targets addressing drug resistance and treatment duration

Conflict of Interest Statement

References

- Atun, R. , Weil, D.E., Eang, M.T., & Mwakyusa, D. (2010). Health-system strengthening and tuberculosis control. The Lancet, 375(9732), 2169-2178. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M., Das, D., Venugopal, K., & Howden-Chapman, P. (2013). Tuberculosis associated with household crowding in a developed country. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(8), 715-721. [CrossRef]

- Bald, D., Villellas, C., Lu, P., & Koul, A. (2017). Targeting energy metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a new paradigm in antimycobacterial drug discovery. mBio, 8(2), e00272-17. [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, K. , Nam, S.L., Ramalingam, B., & Pozo-Martin, F. (2017). Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: towards a new conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(8), 431-435. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.R. , Atun, R., Cohen, T., Dye, C., Fraser, H., Gomez, G.B.,... & Yadav, P. (2017). Tuberculosis. In D.T. Jamison, H. Gelband, S. Horton, P. Jha, R. Laxminarayan, C.N. Mock, & R. Nugent (Eds.), Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Bynum, H. (2012). Spitting Blood: The History of Tuberculosis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cegielski, J.P. , & McMurray, D.N. (2004). The relationship between malnutrition and tuberculosis: evidence from studies in humans and experimental animals. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 8(3), 286-298.

- Colvin, C. , Mugyabuso, J., Munuo, G., Lyimo, J., Oren, E., Mkomwa, Z.,... & Richardson, D. (2014). Evaluation of community-based interventions to improve TB case detection in a rural district of Tanzania. Global Health: Science and Practice, 2(2), 219-225. [CrossRef]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Conradie, F. , Diacon, A.H., Ngubane, N., Howell, P., Everitt, D., Crook, A.M.,... & Nix-TB Trial Team. (2020). Treatment of highly drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(10), 893-902. [CrossRef]

- Cox, H. , Kebede, Y., Allamuratova, S., Ismailov, G., Davletmuratova, Z., Byrnes, G.,... & Mills, C. (2006). Tuberculosis recurrence and mortality after successful treatment: impact of drug resistance. PLoS Medicine, 3(10), e384. [CrossRef]

- Dahl, J.L. , Kraus, C.N., Boshoff, H.I., Doan, B., Foley, K., Avarbock, D.,... & Barry, C.E. (2003). The role of RelMtb-mediated adaptation to stationary phase in long-term persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(17), 10026-10031. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.M. (2006). The history of tuberculosis. Respiratory Medicine, 100(11), 1862-1870. [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, D.W. , Basu, S., & Andrews, J.R. (2013). Is passive diagnosis enough? The impact of subclinical disease on diagnostic strategies for tuberculosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 187(5), 543-551. [CrossRef]

- Drain, P.K. , Bajema, K.L., Dowdy, D., Dheda, K., Naidoo, K., Schumacher, S.G.,... & Shah, M. (2018). Incipient and subclinical tuberculosis: a clinical review of early stages and progression of infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 31(4), e00021-18. [CrossRef]

- Drain, P. , & Drain, P.K. (2019). Urine lipoarabinomannan for tuberculosis diagnosis: evolution and prospects. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 14(1), 12-20.

- Dubos, R. , & Dubos, J. (1952). The White Plague: Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Company.

- Farmer, P. (1999). Infections and Inequalities: The Modern Plagues. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Furin, J., Cox, H., & Pai, M. (2019). Tuberculosis. The Lancet, 393(10181), 1642-1656.

- Gagneux, S. (2018). Ecology and evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16(4), 202-213. [CrossRef]

- Getahun, H. , Gunneberg, C., Granich, R., & Nunn, P. (2010). HIV infection-associated tuberculosis: the epidemiology and the response. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(Supplement_3), S201-S207. [CrossRef]

- Goude, R., Amin, A.G., Chatterjee, D., & Parish, T. (2008). The arabinosyltransferase EmbC is inhibited by ethambutol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 52(2), 804-806. [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, J.R. , Boccia, D., Evans, C.A., Adato, M., Petticrew, M., & Porter, J.D. (2011). The social determinants of tuberculosis: from evidence to action. American Journal of Public Health, 101(4), 654-662. [CrossRef]

- Harper, I. (2010). Extreme condition, extreme measures? Compliance, drug resistance, and the control of tuberculosis. Anthropology & Medicine, 17(2), 201-214.

- Hershkovitz, I. , Donoghue, H.D., Minnikin, D.E., Besra, G.S., Lee, O.Y., Gernaey, A.M.,... & Spigelman, M. (2008). Detection and molecular characterization of 9,000-year-old Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithic settlement in the Eastern Mediterranean. PloS One, 3(10), e3426. [CrossRef]

- Horton, K.C. , MacPherson, P., Houben, R.M., White, R.G., & Corbett, E.L. (2016). Sex differences in tuberculosis burden and notifications in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 13(9), e1002119. [CrossRef]

- Karumbi, J., & Garner, P. (2015). Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5), CD003343. [CrossRef]

- Keshavjee, S., & Farmer, P.E. (2012). Tuberculosis, drug resistance, and the history of modern medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(10), 931-936.

- Kim, J.Y. , Farmer, P., & Porter, M.E. (2013). Redefining global health-care delivery. The Lancet, 382(9897), 1060-1069. [CrossRef]

- Kranzer, K. , Afnan-Holmes, H., Tomlin, K., Golub, J.E., Shapiro, A.E., Schaap, A.,... & Corbett, E.L. (2013). The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active tuberculosis disease: a systematic review. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 17(4), 432-446. [CrossRef]

- Lönnroth, K. , Jaramillo, E., Williams, B.G., Dye, C., & Raviglione, M. (2009). Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Social Science & Medicine, 68(12), 2240-2246. [CrossRef]

- Lönnroth, K. , Castro, K.G., Chakaya, J.M., Chauhan, L.S., Floyd, K., Glaziou, P., & Raviglione, M.C. (2010). Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010-50: cure, care, and social development. The Lancet, 375(9728), 1814-1829.

- Loureiro, R.B. , Villa, T.C.S., Ruffino-Netto, A., Peres, R.L., Braga, J.U., Zandonade, E., & Maciel, E.L. (2014). Access to the diagnosis of tuberculosis in health services in the municipality of Vitória, ES, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 19(4), 1233-1244.

- MacLean, E. , Sulis, G., Denkinger, C.M., Johnston, J.C., Pai, M., & Khan, F.A. (2019). Diagnostic accuracy of stool Xpert MTB/RIF for the detection of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 57(6), e02057-18. [CrossRef]

- Mangtani, P. , Abubakar, I., Ariti, C., Beynon, R., Pimpin, L., Fine, P.E.,... & Rodrigues, L.C. (2014). Protection by BCG vaccine against tuberculosis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 58(4), 470-480. [CrossRef]

- McKeown, T. (1976). The Modern Rise of Population. London: Edward Arnold. [CrossRef]

- Medical Research Council. (1948). Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. British Medical Journal, 2(4582), 769-782.

- Nery, J.S. , Rodrigues, L.C., Rasella, D., Aquino, R., Barreira, D., Torrens, A.W.,... & Barreto, M.L. (2017). Effect of Brazil's conditional cash transfer programme on tuberculosis incidence. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(7), 790-796. [CrossRef]

- North, E.J., Jackson, M., & Lee, R.E. (2014). New approaches to target the mycolic acid biosynthesis pathway for the development of tuberculosis therapeutics. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(27), 4357-4378. [CrossRef]

- Pethe, K., Bifani, P., Jang, J., Kang, S., Park, S., Ahn, S., ... & Keller, T.H. (2013). Discovery of Q203, a potent clinical candidate for the treatment of tuberculosis. Nature Medicine, 19(9), 1157-1160. [CrossRef]

- Ramage, H.R. , Connolly, L.E., & Cox, J.S. (2009). Comprehensive functional analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis toxin-antitoxin systems: implications for pathogenesis, stress responses, and evolution. PLoS Genetics, 5(12), e1000767. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.T. , Morrow, C.D., Kalil, D.B., Bekker, L.G., & Wood, R. (2014). Shared air: a renewed focus on ventilation for the prevention of tuberculosis transmission. PloS One, 9(5), e96334. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.A. , & Buikstra, J.E. (2003). The Bioarchaeology of Tuberculosis: A Global View on a Reemerging Disease. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Sahu, S. , Ditiu, L., & Zumla, A. (2021). After COVID-19, TB and other respiratory diseases in low and middle-income countries will still need strengthened healthcare systems and public health infrastructure. Journal of Infection, 28(3), 175-177.

- Samuel, B. , Volkmann, T., Cornelius, S., Mukhopadhay, S., MejoJose, Mitra, K.,... & Chadha, V.K. (2018). Relationship between nutritional support and tuberculosis treatment outcomes in West Bengal, India. Journal of Tuberculosis Research, 6(2), 132-141.

- Schrager, L.K. , Harris, R.C., & Vekemans, J. (2020). Research and development of new tuberculosis vaccines: a review. F1000Research, 8, F1000 Faculty Rev-1025. [CrossRef]

- Siroka, A. , Ponce, N.A., & Lönnroth, K. (2016). Association between spending on social protection and tuberculosis burden: a global analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(4), 473-479. [CrossRef]

- Stuckler, D. , King, L., Robinson, H., & McKee, M. (2008). WHO's budgetary allocations and burden of disease: a comparative analysis. The Lancet, 372(9649), 1563-1569. [CrossRef]

- Subbaraman, R. , de Mondesert, L., Musiimenta, A., Pai, M., Mayer, K.H., Thomas, B.E., & Haberer, J. (2019). Digital adherence technologies for the management of tuberculosis therapy: mapping the landscape and research priorities. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e001018. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T. , & Amor, Y.B. (2012). The co-management of tuberculosis and diabetes: challenges and opportunities in the developing world. PLoS Medicine, 9(7), e1001269.

- Szreter, S. (1988). The importance of social intervention in Britain's mortality decline c. 1850–1914: a re-interpretation of the role of public health. Social History of Medicine, 1(1), 1-38.

- Tanimura, T. , Jaramillo, E., Weil, D., Raviglione, M., & Lönnroth, K. (2014). Financial burden for tuberculosis patients in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. European Respiratory Journal, 43(6), 1763-1775. [CrossRef]

- TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group. (2015). A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(9), 808-822.

- Treatment Action Group. (2022). Tuberculosis Research Funding Trends, 2005-2021. New York: Treatment Action Group.

- van Rie, A., Warren, R., Richardson, M., Victor, T.C., Gie, R.P., Enarson, D.A., ... & van Helden, P.D. (1999). Exogenous reinfection as a cause of recurrent tuberculosis after curative treatment. New England Journal of Medicine, 341(16), 1174-1179. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meeren, O. , Hatherill, M., Nduba, V., Wilkinson, R.J., Muyoyeta, M., Van Brakel, E.,... & Tait, D.R. (2018). Phase 2b controlled trial of M72/AS01E vaccine to prevent tuberculosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(17), 1621-1634.

- Whitehead, M. , & Dahlgren, G. (2007). Concepts and principles for tackling social inequities in health: Levelling up Part 1. Copenhagen: World Health Organization.

- Wilson, L.G. (1990). The historical decline of tuberculosis in Europe and America: its causes and significance. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 45(3), 366-396. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2014). The End TB Strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO Housing and Health Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Global Tuberculosis Report 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on TB Detection and Mortality in 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization & International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. (2011). Collaborative Framework for Care and Control of Tuberculosis and Diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Zumla, A., Nahid, P., & Cole, S.T. (2013). Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 12(5), 388-404. [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A. , Rao, M., Wallis, R.S., Kaufmann, S.H., Rustomjee, R., Mwaba, P.,... & Maeurer, M. (2016). Host-directed therapies for infectious diseases: current status, recent progress, and future prospects. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 16(4), e47-e63. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).