I. Introduction

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most devastating manifestation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, accounting for a significant proportion of tuberculosis-related deaths and long-term neurological disability [

1,

2]. The disease arises when

Mycobacterium tuberculosis invades the central nervous system, triggering a granulomatous inflammatory response in the meninges [

3,

4,

5]. This process can result in hydrocephalus, vasculitis, infarctions, and raised intracranial pressure, contributing to its high case fatality and the potential for profound neurocognitive sequelae [

3,

6]. Early diagnosis and initiation of anti-tuberculosis therapy, often supplemented with corticosteroids, are essential to improving outcomes, yet diagnostic delays are common due to the nonspecific early symptoms and limited diagnostic capacity in many healthcare settings [

1,

7].

Globally, TBM poses a major challenge in tuberculosis-endemic regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where the burden of HIV co-infection exacerbates disease severity and complicates clinical management [

8,

9]. HIV-positive individuals are at higher risk of developing disseminated TB, including TBM, and have a poorer prognosis due to immunosuppression and increased likelihood of drug-resistant strains [

10,

11]. In resource-limited environments, the lack of access to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture, imaging, and rapid molecular diagnostics such as Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra compounds the difficulty of confirming TBM, leading to reliance on clinical criteria and empiric treatment [

3,

11]. Despite these challenges, studies focusing specifically on TBM in rural African settings remain limited, especially regarding mortality outcomes and risk factor profiles.

Mozambique is among the 30 countries with the highest tuberculosis (incidence of 361 per 100,000 population) and TB/HIV burden (incidence of 83 per 100,000 population), with significant disparities in healthcare infrastructure between urban and rural areas [

8,

12]. In rural hospitals, the diagnosis and management of TBM are often hindered by insufficient laboratory support, shortages of trained personnel, and delays in referral pathways. While national TB control programs have made progress in expanding diagnostic and treatment services [

13,

14], TBM remains under-recognized and under-reported. The absence of local epidemiological data on TBM contributes to the lack of targeted clinical guidelines for rural health facilities and hampers efforts to improve case detection and survival.

This study aims to describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients diagnosed with TBM at a rural hospital in Mozambique and to identify risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality. By providing evidence from a real-world rural setting, the study seeks to contribute to the limited body of knowledge on TBM in high-burden, resource-constrained environments. Findings from this study may inform clinical decision-making, support context-specific treatment protocols, and highlight areas for health system strengthening and further research.

II. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This was a retrospective observational study conducted at Carmelo Hospital of Chókwè, a rural referral facility in southern Mozambique. The hospital serves a predominantly rural population with a high burden of TB and HIV. The study period spanned six years, from January 2015 to December 2020, and focused specifically on cases of TBM diagnosed and managed at the facility.

2.2. Study Population and Case Selection

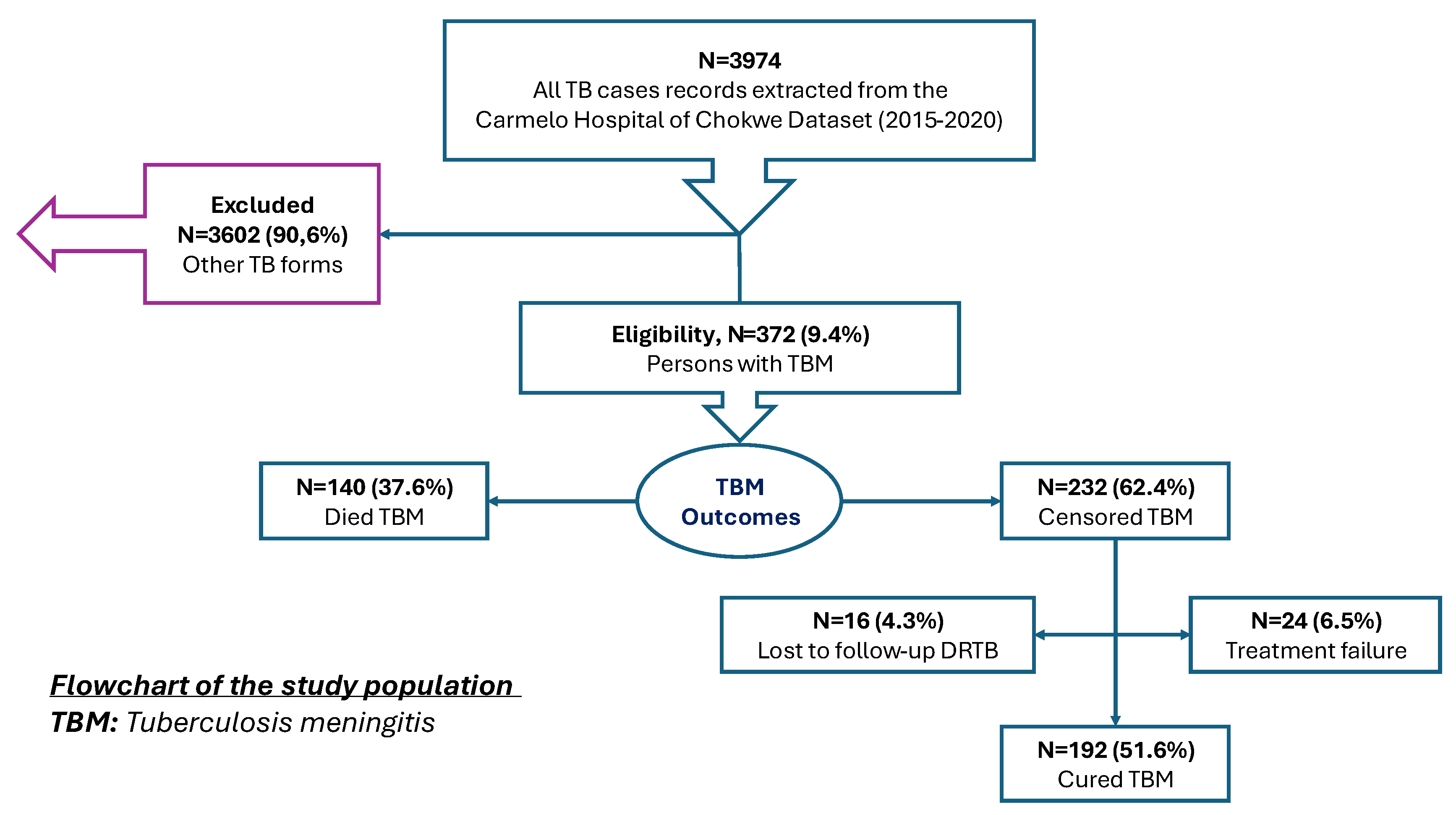

Medical records of all TB patients registered in the hospital’s tuberculosis database during the study period were reviewed. A total of 3,974 TB cases were recorded. From these, 372 cases (9.4%) were identified as having TBM and were included in the analysis. Cases of pulmonary TB and other extrapulmonary forms were excluded (N=3,602; 90.6%). TBM cases were identified based on clinical documentation in the medical records following a hospital-adapted screening and diagnostic algorithm. (

Figure 1).

2.2.1. TBM Screening and Diagnostic Criteria

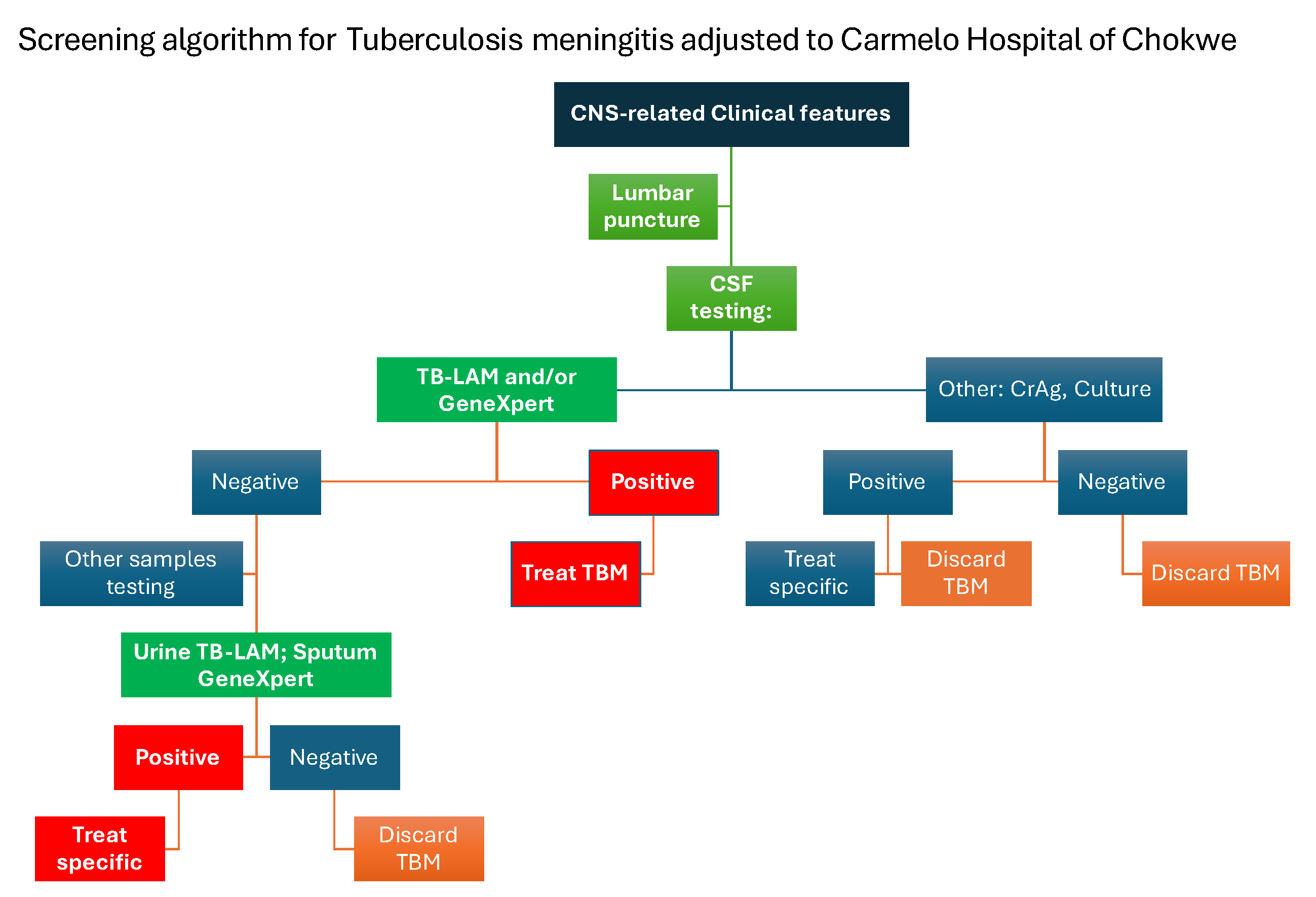

At Carmelo Hospital, the diagnosis of TBM followed a structured screening algorithm integrating clinical assessment with stepwise laboratory testing. Patients presenting with central nervous system (CNS)-related clinical features—such as headache, neck stiffness, altered mental status, or seizures—underwent lumbar puncture for CSF testing.

Initial CSF testing included TB-LAM and/or Xpert MTB/RIF Utra. A positive result on either test led to immediate initiation of TBM treatment. If the result was negative, further diagnostic steps were pursued. These included CSF analysis for other aetiologies such as cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) and culture. Positive findings for non-TB pathogens resulted in treatment specific to the identified condition, and TBM was discarded as a diagnosis.

In cases where both CSF TB-LAM/Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra and CrAg/culture were negative, additional testing using non-CSF samples was performed. Urine TB-LAM or sputum Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra tests were used to further evaluate for extrapulmonary TB. A positive result in these tests prompted treatment of TB, while negative results led to the exclusion of TBM.

This diagnostic algorithm allowed for a pragmatic, tiered approach to TBM diagnosis in a resource-limited setting, supporting rapid treatment decisions while accounting for differential diagnoses (

Figure 2).

2.3. Data Collection and Variables

A standardized data extraction tool was used to collect information from medical records, including demographic data (age, sex), clinical presentation, HIV status, laboratory results (CSF, Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra, TB-LAM), and treatment details. Outcome variables included in-hospital mortality (primary outcome), loss to follow-up, treatment failure, and treatment success (cure or completion). Patients were followed from admission until treatment outcome or hospital discharge.

2.4. Outcomes definitions

Died TBM: Patients with TBM who died during hospitalization or TB treatment.

Cured TBM: Patients who completed treatment and had a documented favourable clinical response.

Treatment failure: Clinical deterioration or persistent symptoms despite TB treatment.

Lost to follow-up: Patients who discontinued treatment or were transferred to other facilities with unknown outcome.

Censored: Patients still under treatment or with missing final outcome documentation.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics, stratified by mortality outcome. Continuous variables were reported as means or medians, and categorical variables as proportions. The primary outcome was time to death from the date of TBM diagnosis. Mortality incidence rates were calculated per 100 person-months of observation. Survival time was estimated using Kaplan–Meier curves, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. To identify factors independently associated with mortality, univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were fitted. Variables with p < 0.2 in univariable analysis or of clinical relevance were included in the multivariable model. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals and log–log plots.

III. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Mortality Outcomes

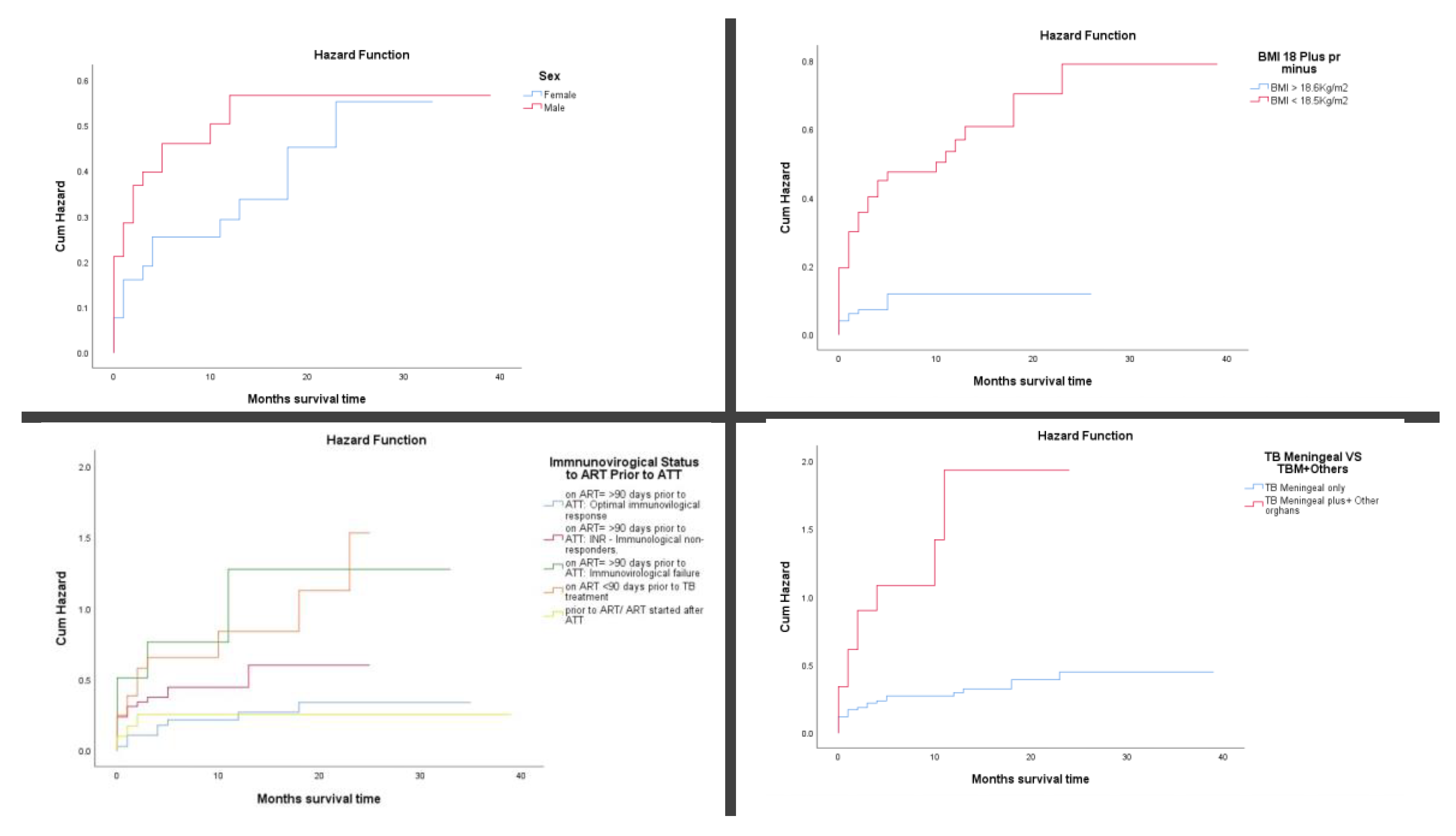

A total of 372 patients with TBM were included in the study from 2015 to 2020. During the treatment follow-up period, 140 patients (37.6%) died, corresponding to an overall mortality incidence of 3.76 deaths per 100 person-months (95% CI: 3.14–3.76) over 3,720 person-months of observation. The majority of patients were male (56.5%), and males accounted for a higher proportion of deaths (60.0%). The incidence of mortality was notably higher in males (4.44 per 100 person-months) compared to females (2.30 per 100 person-months).

Undernutrition was common, with 72.8% of patients presenting with a BMI <18.5 kg/m². This group represented 92.1% of all deaths, with a mortality incidence of 4.76 per 100 person-months, in contrast to 0.99 per 100 person-months among patients with a BMI >18.6 kg/m². These findings highlight undernutrition as a major risk factor for TBM mortality.

Among patients who had been on antiretroviral treatment (ART) for ≥90 days prior to initiating TB treatment, those with an optimal immunological response had the lowest mortality incidence (2.04 per 100 person-months). In contrast, immunological non-responders (INR) and those with immunovirological failure experienced significantly higher mortality (4.44 and 22.22 per 100 person-months, respectively). Patients who had initiated ART <90 days before starting TB treatment had a mortality incidence of 8.00 per 100 person-months, while those who initiated ART after TB treatment or had no ART history had a lower but still notable incidence (2.02 per 100 person-months). These results underscore the critical role of ART timing and immune reconstitution in TBM outcomes.

Most patients (84.1%) presented with isolated TB meningitis, while 15.9% had TBM with additional organ involvement. The latter group experienced significantly higher mortality, with an incidence of 39.83 per 100 person-months, compared to 2.48 per 100 person-months among those with isolated meningeal disease.

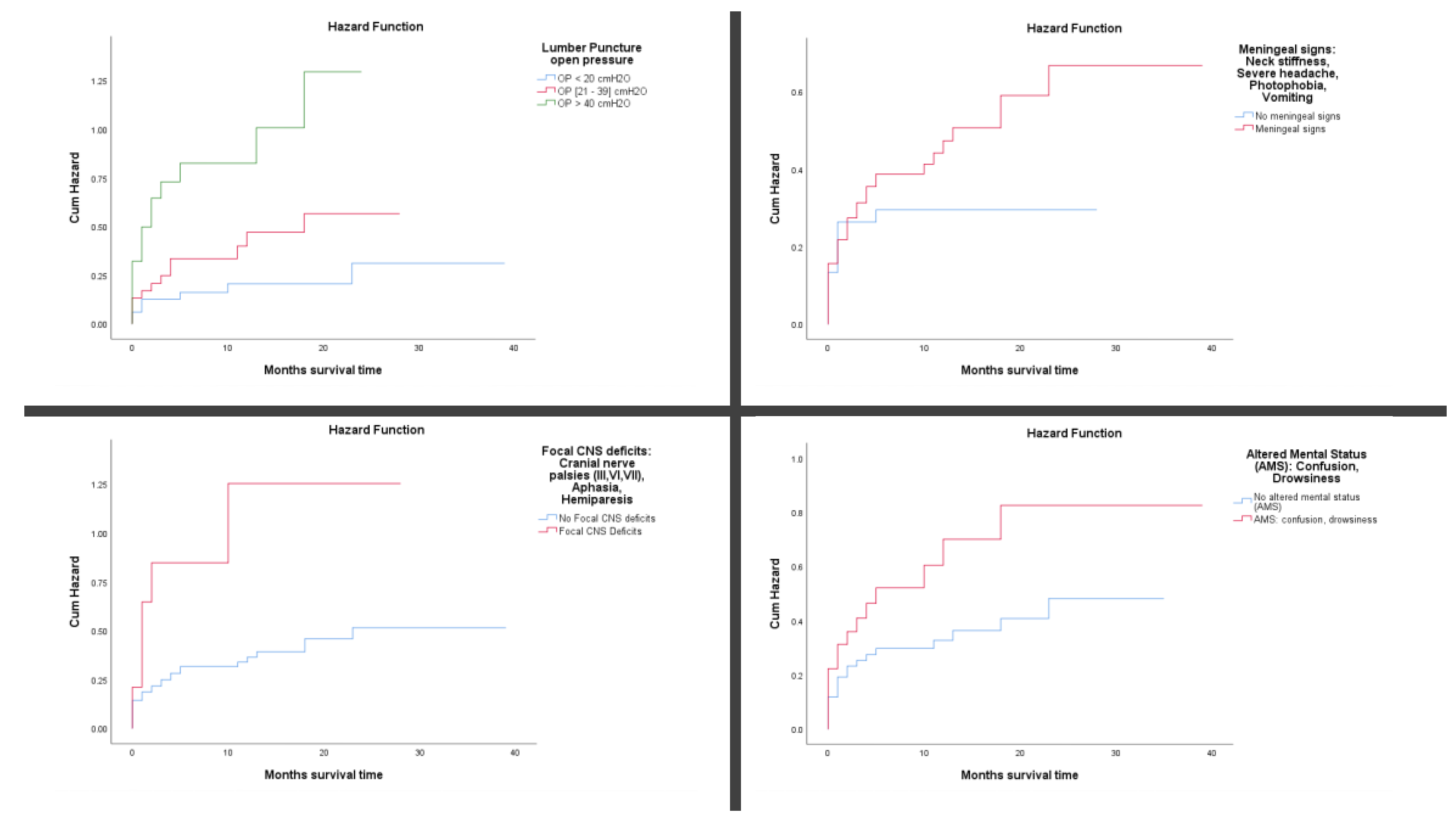

Among patients with recorded CSF opening pressure, mortality increased with pressure levels. Those with pressures >40 cmH₂O had the highest mortality incidence (31.37 per 100 person-months), while those with pressures between 21–39 cmH₂O and <20 cmH₂O had lower rates (3.57 and 1.58 per 100 person-months, respectively).

Neurological Signs and Symptoms like meningeal signs (e.g., neck stiffness, photophobia, severe headache, vomiting) were present in 74.2% of patients and associated with a higher mortality incidence (3.82 per 100 person-months) than those without such signs (2.78 per 100 person-months). Focal CNS deficits (e.g., cranial nerve palsies, aphasia, hemiparesis) were observed in 11.3% of patients and markedly increased mortality risk (33.33 per 100 person-months) compared to patients without deficits (3.09 per 100 person-months).

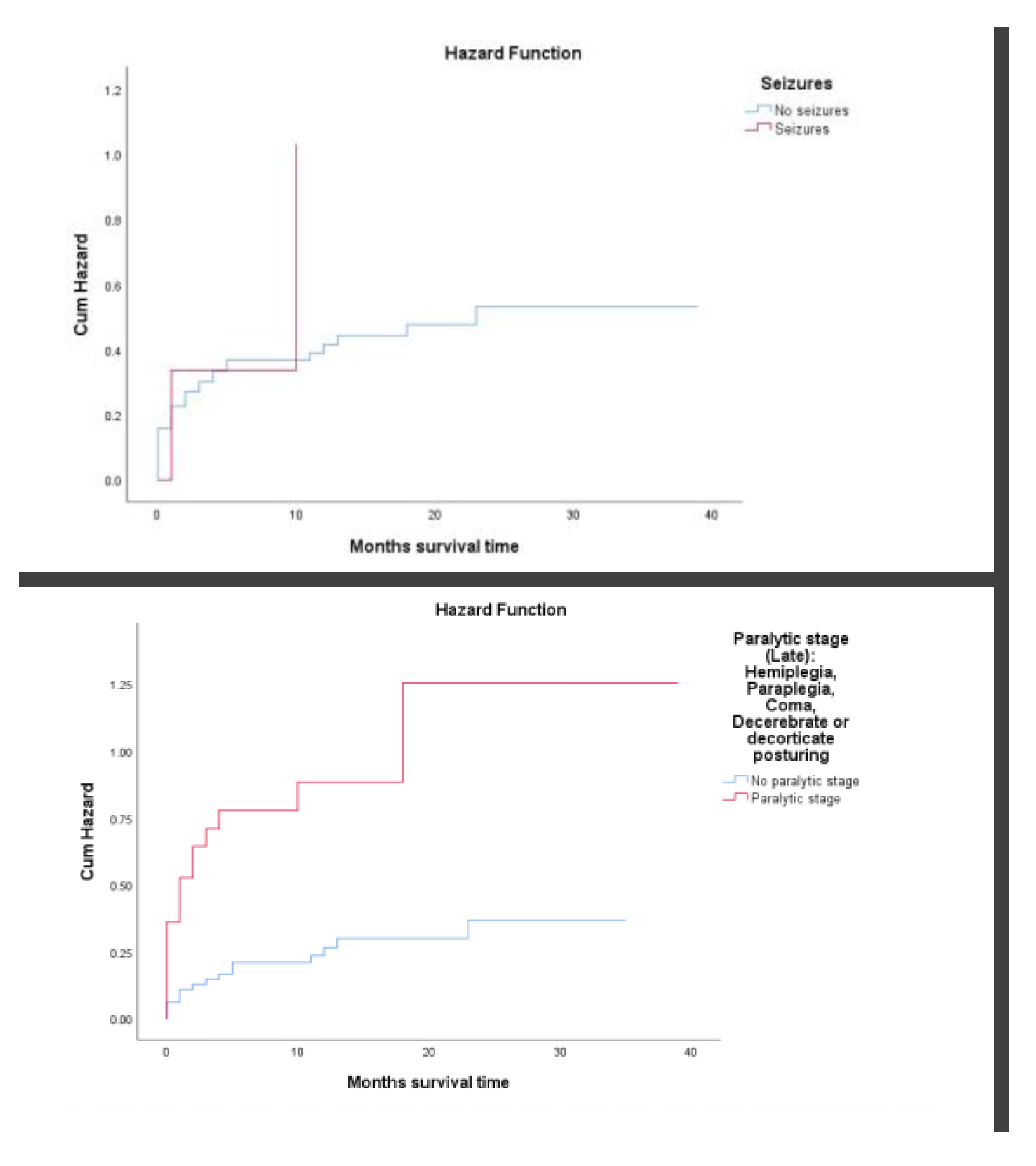

Altered mental status (AMS), including confusion or drowsiness, was seen in 32.3% of patients and associated with a higher mortality incidence (5.56 per 100 person-months) than in patients without AMS (2.89 per 100 person-months). Seizures were reported in only 3.8% of patients but carried a high mortality incidence (8.57 per 100 person-months). Late-stage neurological compromise (paralytic stage, including hemiplegia, coma, or decerebrate/decorticate posturing) was observed in 32.8% of patients and associated with significantly elevated mortality (21.31 per 100 person-months) compared to those without such features (2.07 per 100 person-months). (

Table 1)

3.2. Predictors of Mortality in Patients with Tuberculous Meningitis

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis identified several independent predictors of mortality. Male sex was independently associated with increased mortality. Compared to females, males had a 1.80-fold higher adjusted hazard of death (aHR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.21–2.68; p = 0.004). Patients with BMI <18.5 kg/m² had significantly higher risk of death than those with BMI >18.6 kg/m². In the adjusted model, undernourished patients had a 2.75 times greater hazard of mortality (aHR: 2.75; 95% CI: 1.41–5.36; p = 0.003).

The immune and virological response to ART prior to anti-TB treatment initiation was strongly predictive of survival. INR had a 2.16-fold increased risk of death compared to those with optimal immune recovery (aHR: 2.16; 95% CI: 1.29–3.62; p = 0.003). Patients with immunovirological failure showed an even higher hazard (aHR: 2.82; 95% CI: 1.54–5.16; p = 0.001). Those who initiated ART <90 days before TB treatment also faced elevated mortality (aHR: 2.01; 95% CI: 1.19–3.38; p = 0.009). Being ART-naïve or starting ART after TB treatment was not significantly associated with mortality (aHR: 0.69; p = 0.278).

Patients with TBM involving other organs in addition to the meninges had more than double the hazard of death compared to those with isolated TBM (aHR: 2.07; 95% CI: 1.31–3.29; p = 0.002). Elevated cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure was a strong independent predictor of mortality: moderate elevation (21–39 cmH₂O): aHR 2.08 (95% CI: 1.25–3.46; p = 0.005) and marked elevation (>40 cmH₂O): aHR 3.83 (95% CI: 2.33–6.31; p < 0.001).

Meningeal signs (e.g., neck stiffness, vomiting, photophobia) were independently associated with increased mortality (aHR: 2.87; 95% CI: 1.74–4.75; p < 0.001). Focal CNS deficits and seizures, although significant in crude analysis, were not statistically significant in the adjusted model (aHRs: 1.46 and 0.89, respectively; p > 0.1). Altered mental status (AMS) was not significantly associated with mortality after adjustment (aHR: 1.06; p = 0.793). Presence of paralytic signs (e.g., coma, hemiplegia, decerebrate posture) was a strong independent predictor of death (aHR: 2.15; 95% CI: 1.31–3.56; p = 0.003).

Overall, the multivariable model underscores that male sex, undernutrition, poor ART response or timing, high CSF opening pressure, disseminated TB, and late-stage neurological deterioration were significant independent predictors of mortality among TBM patients in this rural Mozambican setting. (

Table 2)

3.3. Cumulative Mortality Rate

Cumulative mortality rate using Kaplan–Meier plots and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests revealed significant differences in mortality across several clinical and demographic variables (

Figure 3A-D). Men with TB meningitis had a higher cumulative incidence of death than women, exceeding 40% by three months of follow-up (

p = 0.039). Undernourished patients (BMI <18.5 kg/m²) experienced significantly greater mortality, with cumulative deaths surpassing 40% within three months of follow-up (

p < 0.001). Among HIV-positive patients, those with immunovirological failure despite being on ART for more than 90 days prior to TB treatment initiation had over 50% mortality by three months of follow-up (

p < 0.001). TB meningitis with concurrent involvement of other organs was associated with particularly poor outcomes, with cumulative mortality exceeding 90% at three months of follow-up (

p < 0.001).

Elevated CSF opening pressure was another strong predictor of early death; patients with pressures ≥40 cmH₂O had cumulative mortality above 65% (

p < 0.001). The presence of meningeal signs, such as neck stiffness and photophobia, was also associated with worse survival, with a 3-month mortality rate of over 31.5% compared to those without such signs (

p = 0.029). Focal neurological deficits, including cranial nerve palsies and hemiparesis, significantly increased the risk of death, with cumulative incidence exceeding 85% within three months of follow-up (

p < 0.001). Similarly, altered mental status (e.g., confusion, drowsiness) was linked to a higher risk of early mortality, with over 36% dying by three months of follow-up (

p < 0.001). (

Figure 3E-F)

Seizures, although less common, were associated with a 3-month cumulative mortality above 34% (

p = 0.001). Finally, patients in the paralytic stage, marked by severe neurological compromise such as coma or decerebrate posturing, had markedly worse outcomes, with more than 64.5% dying within the first three months of follow-up (

p < 0.001). (

Figure 3I-J)

Figure 3I-J.

Survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier cumulative hazard plots and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests (seizures and late paralytic stage). Figure 3I: Presenting seizures had higher cumulative incidence of death above 34% after 3 months of follow-up (log Rank test p=0.001). Figure 3J: Presenting paralytic stage had higher cumulative incidence of death above 64.5% after 3 months of follow-up (log Rank test p=0.000).

Figure 3I-J.

Survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier cumulative hazard plots and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests (seizures and late paralytic stage). Figure 3I: Presenting seizures had higher cumulative incidence of death above 34% after 3 months of follow-up (log Rank test p=0.001). Figure 3J: Presenting paralytic stage had higher cumulative incidence of death above 64.5% after 3 months of follow-up (log Rank test p=0.000).

IV. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of mortality and its associated risk factors among patients diagnosed with TBM at a rural hospital in Mozambique over a six-year period. The overall mortality rate of 37.6% highlights the severe prognosis of TBM in resource-limited settings and is consistent with findings from other high-burden TB/HIV countries, where diagnostic delays, limited access to neuroimaging, and advanced disease presentation remain common challenges [

15,

16].

Several demographic and clinical factors were independently associated with increased mortality as found in other similar studies [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Male sex was significantly linked to higher mortality risk, possibly reflecting gender differences in health-seeking behaviour and delayed presentation. Malnutrition, defined by a BMI <18.5 kg/m², emerged as a powerful predictor of death, underscoring the impact of poor nutritional status on immune function and disease progression. These findings support the urgent need for nutritional interventions as part of comprehensive TBM care.

HIV co-infection and ART status played a critical role in patient outcomes. Patients who had been on ART for more than 90 days but exhibited immunological non-response or immunovirological failure faced significantly higher mortality. Similarly, those who initiated ART shortly before TB treatment experienced worse outcomes than those with optimal immune recovery. Contributing to existing studies [

18,

19,

21,

22], our findings further specify which subgroups of HIV co-infected individuals are at greatest risk of death: those with failed immune reconstitution despite ART, and those initiating ART in the early phase of TB treatment. These distinctions are crucial in guiding clinical decision-making and patient monitoring. The results reinforce the importance of early HIV diagnosis, timely ART initiation, and sustained immunovirological monitoring in TB/HIV co-infected individuals, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Neurological severity at presentation was another key determinant of mortality. Elevated CSF opening pressure—particularly values above 40 cmH₂O—was strongly associated with poor survival, likely reflecting increased intracranial pressure, hydrocephalus, or extensive inflammation. The presence of meningeal signs, focal neurological deficits, altered mental status, and progression to paralytic stages (e.g., coma or decerebrate posturing) were all associated with significantly increased risk of death. These findings reaffirm earlier evidence on the prognostic value of neurological signs and highlight the continued relevance of early lumbar puncture with CSF pressure measurement in the clinical workup of TBM, especially in settings where advanced neuroimaging is not readily available [

16,

20,

21,

22].

Patients with TBM and additional extrapulmonary involvement—indicative of disseminated TB—had particularly poor outcomes, with over 90% mortality within three months. This highlights a more aggressive disease phenotype that likely requires intensified monitoring, broader organ support, and possibly modified therapeutic approaches. Notably, we found limited literature specifically addressing mortality outcomes among TBM patients with concurrent extrapulmonary TB involvement [

23,

24,

25]. In light of our findings, a deeper investigation into this high-risk subgroup is warranted to better understand underlying mechanisms and to inform tailored clinical management strategies.

4.2. Strength and Limitations

This study has several strengths. It included a relatively large number of patients with TB meningitis over a six-year period, which allowed for meaningful analysis of mortality patterns in a rural hospital setting. By using routinely collected clinical data, the study reflects real-world conditions in a resource-limited environment. A key strength was the ability to differentiate between subgroups of HIV co-infected patients, such as those with optimal immune response, immunological non-response, and immunovirological failure; an area not often explored in detail. The study also incorporated a broad range of clinical indicators, including CSF opening pressure, neurological status, ART history, BMI, and extent of TB involvement, to better understand factors associated with poor outcomes. The use of survival analysis and multivariable Cox regression helped to identify independent predictors of mortality while accounting for potential confounders. Additionally, the study contributes to the limited evidence on TBM outcomes among patients with disseminated TB, highlighting an area that may require further research.

There are however several limitations. First, its retrospective design, based on routine clinical records, made it susceptible to missing or incomplete data, which may have introduced misclassification or limited the ability to fully adjust for confounders. Second, TBM diagnosis in many cases relied on clinical algorithms rather than microbiological confirmation, due to constrained diagnostic capacity. This may have led to diagnostic uncertainty or underestimation of TBM cases. Third, the study lacked detailed data on adjunctive therapies such as corticosteroids, patient adherence to TB and HIV treatment, and the precise timing of ART initiation relative to TB treatment. Lastly, the single-centre design may limit generalizability to other healthcare settings in Mozambique or the broader sub-Saharan African context.

V. Conclusions and Recommendations

Tuberculous meningitis continues to carry a high mortality burden in rural Mozambique, particularly among men, malnourished patients, and individuals with HIV co-infection and poor immunological response to ART. Elevated CSF pressure, disseminated TB, and advanced neurological signs at presentation were strong predictors of death. These findings underscore the urgent need for early diagnosis, prompt lumbar puncture with pressure assessment, and integrated HIV and nutritional support services at the point of care. Strengthening diagnostic infrastructure and implementing early intervention pathways are essential steps toward improving TBM outcomes in low-resource settings.

5.1. What the Bullet Points of This Study?

Prioritize Early Diagnosis & Triage: Implement urgent lumbar puncture (LP) with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure measurement for patients presenting with central nervous system symptoms (e.g., headache, neck stiffness, altered mental status) in high TB/HIV burden areas. Expand access to and utilization of rapid point-of-care diagnostic tests like Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra and TB-LAM on CSF and other samples (e.g., urine, sputum) to confirm tuberculous meningitis (TBM) quickly. Actively use identified risk factors (male sex, malnutrition, disseminated disease) to flag high-risk patients for immediate, intensive management.

Aggressively Manage Intracranial Hypertension: Routinely measure and actively manage elevated CSF pressure, identified as a critical predictor of death. Perform therapeutic LPs for pressures exceeding 40 cmH₂O. Train healthcare workers in managing intracranial hypertension using available interventions like acetazolamide or osmotic agents, especially where neurosurgical support is limited. Screen all TBM patients for signs of disseminated TB involving other organs, given its association with extremely high mortality.

Integrate & Optimize HIV, TB, and Nutritional Care: Ensure timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV co-infected patients, generally within 2 weeks of starting TB treatment, while carefully weighing risks in severe neurological cases. Crucially, avoid starting ART less than 90 days before TB treatment initiation due to the associated higher mortality risk. Regularly monitor CD4 counts and viral loads to detect and promptly address immunovirological failure. Embed robust nutritional assessment and support, including therapeutic feeding programs, into routine TB/HIV care, particularly targeting patients with low BMI (<18.5 kg/m²).

Standardize Neurological Assessment and Adjunctive Care: Develop and implement protocols for consistent staging of neurological severity at presentation. Train clinicians to recognize high-risk late-stage neurological signs (e.g., coma, decerebrate posturing, hemiplegia) that necessitate intensive monitoring and care. Ensure the consistent use of adjunctive corticosteroids per WHO guidelines in eligible TBM patients. Recognize focal neurological deficits and seizures as indicators of poor prognosis requiring heightened vigilance.

Strengthen Health System Capacity: Invest in building sustainable diagnostic capacity in rural settings, including deploying affordable tools and maintaining reliable supplies of essential tests (Xpert, TB-LAM). Develop and disseminate context-specific clinical guidelines for TBM management tailored to the realities of resource-limited hospitals, emphasizing the critical steps identified (LP/pressure management, integrated care). Enhance training programs for frontline healthcare workers focusing on TBM recognition, safe LP procedures, complication management, and integrated HIV/TB/nutrition care. Strengthen referral pathways for complex cases requiring advanced care.

Author Contributions

E.N. contributed to the study design, data acquisition, study implementation, data analysis and its interpretation, with a major contribution to writing the first draft, reviewing, and editing. He read and approved final version. I.M contributed on study design, data acquisition, data analysis and its interpretation, writing review and editing, and approved the final version. D.O. contributed on data analysis and its interpretation, writing, reviewing, editing, and approved the final version. J.M.R.R. contributed on study design, data analysis and its interpretation, writing, reviewing, editing, and approved the final version.

Funding

This research was full supported by the Tinpswalo Research Association to Fight AIDS and TB. No external funding was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Bioethics Committee for Health of Gaza (IRB0002657 – Comité Institucional de Bioética para a Saúde de Gaza, 19/CIBS-Gaza/2021 and permission to perform the study was also obtained from the Gaza Health Directorate (Direcção Provincial de Saúde de Gaza, DPS-Gaza/30-04-2019). This study received a Research Determination from the University Miguel Hernandez de Elche-Spain under the authorization code COIR (Solicitud Código de Investigación Responsable [COIR]: ADH.SPU.JMRR.EEA.23). The need for written informed consent to participate in the study and for its publication was explicitly waived by IRB0002657 (Comité Institucional de Bioética para a Saúde de Gaza, 19/CIBS-Gaza/2021). All information obtained during the study was kept confidential. Analysis was performed on de-identified aggregated data. Furthermore, this study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent to participate in the routine program was waived by IRB because we performed analysis on routine administrative data. All information obtained during the analysis was kept confidential. Analysis was performed on de-identified aggregated data. Furthermore, this analysis was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets utilized in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request; however, they are not publicly accessible due to privacy constraints.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the staff of the Carmelo Hospital of Chókwè, Gaza, Mozambique for their co-operation, Dr Santos Matsinhe and Nurse Sergio Ussivane for their excellent technical assistance. The authors also want to express their gratitude to Sister Maria Elisa Verdu and Sister Maria Serra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any agency to which they are affiliated

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| aHR |

Adjusted hazard ratios |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CI: |

Confidence intervals |

| CSF |

Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CHC: |

Carmelo Hospital of Chókwè |

| CXR |

Chest X-ray examination |

| ART |

Antiretroviral therapy |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| PLWH |

People living with HIV |

| TBM |

Tuberculous meningitis |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Lin, F.; Tuberculous meningitis diagnosis and treatment: classic approaches and high-throughput pathways. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2025 Jan 10 15. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1543009/full (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Kalita J, Misra UK, Ranjan P. Predictors of long-term neurological sequelae of tuberculous meningitis: a multivariate analysis. European Journal of Neurology [Internet]. 2007, 14, 33–7. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01534.x (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyelo CM, Solomons RS, Walzl G, Chegou NN. Tuberculous Meningitis: Pathogenesis, Immune Responses, Diagnostic Challenges, and the Potential of Biomarker-Based Approaches. Journal of Clinical Microbiology [Internet]. 2021, 18, 59. Available online: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jcm.01771-20 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Isabel BE, Rogelio HP. Pathogenesis and immune response in tuberculous meningitis. Malays J Med Sci. 2014, 21, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dastur DK, Manghani DK, Udani PM. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms in neurotuberculosis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1995, 33, 733–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites G, Chau TT, Mai NT, Drobniewski F, McAdam K, Farrar J. Tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000, 68, 289–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao WF, Leng EL, Liu SM, Zhou YL, Luo CQ, Xiang ZB, et al. Recent advances in microbiological and molecular biological detection techniques of tuberculous meningitis. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1202752/full (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 Oct p. 68. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 10 November 2024].

- Chin, JH. Tuberculous meningitis. Neurol Clin Pract [Internet]. 2014, 4, 199–205. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4121465/ (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenforde MW, Gertz AM, Lawrence DS, Wills NK, Guthrie BL, Farquhar C, et al. Mortality from HIV-associated meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society [Internet]. 2020, 23, e25416. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jia2.25416 (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottberg A von, Meintjes G. Meningitis: a frequently fatal diagnosis in Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2019, 19, 676–8. Available online: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(19)30111-2/fulltext (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PNCT. Relatorio Anual 2024. Maputo: MISAU; 2024 Maio p. 81.

- Programa Nacional de Controle da Tuberculose. Relatorio Anual 2023. Maputo: MISAU; 2023.

- PNCT. Plano Estratégico Nacional para acabar com a Tuberculose em Moçambique 2023 - 2030. Maputo: Ministério da Saúde; 2023 p. 129.

- Seid G, Alemu A, Dagne B, Gamtesa DF. Microbiological diagnosis and mortality of tuberculosis meningitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0279203. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0279203 (accessed on 7 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki Rad M, Haddad M, Sheybani F, Shirazinia M, Dadgarmoghaddam M. Mortality predictors and diagnostic challenges in adult tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort of 100 patients. Tropical Medicine and Health [Internet]. 2025, 53, 58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasar KK, Pehlivanoglu F, Sengoz G. Predictors of mortality in tuberculous meningitis: a multivariate analysis of 160 cases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010, 14, 1330–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kagimu E, Bangdiwala A, Kasibante J, Kabahubya M, Gakuru J, Timothy M, et al. Predictors of Early Mortality in HIV-associated Tuberculous Meningitis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2023, 10, ofad500. [CrossRef]

- George EL, Iype T, Cherian A, Chandy S, Kumar A, Balakrishnan A, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with meningeal tuberculosis. Neurology India [Internet]. 2012, 60, 18, https://journals.lww.com/neur/fulltext/2012/60010/predictors_of_mortality_in_patients_with_meningeal.4.67aspx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Gu Z, Chen X, Yu X, Meng X. Analysis of risk factors for long-term mortality in patients with stage II and III tuberculous meningitis. BMC Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2024, 24, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao LTP, Heemskerk AD, Geskus RB, Mai NTH, Ha DTM, Chau TTH, et al. Prognostic Models for 9-Month Mortality in Tuberculous Meningitis. Clinical Infectious Diseases [Internet]. 2018, 66, 523–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marais S, Pepper DJ, Schutz C, Wilkinson RJ, Meintjes G. Presentation and Outcome of Tuberculous Meningitis in a High HIV Prevalence Setting. PLOS ONE [Internet]. 2011, 6, e20077, https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0020077. [Google Scholar]

- Kalangi H, Boadla LR, Perlman DC, Yancovitz SR, George V, Salomon N. A true challenge: Disseminated tuberculosis with tuberculous meningitis in a patient with underlying chronic liver disease. IDCases [Internet]. 2024, 37, e02065, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214250924001410. [CrossRef]

- Aslan S, Gulsun S, Atalay B. Disseminated tuberculosis complicated with tuberculous meningitis, miliary tuberculosis, and thoracal bone fracture while investigating a cervical lymphadenopathy. Tuberculosis: a hidden enemy? Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2010, 15, 129–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal T, Hurley P, McCormick M. Disseminated tuberculosis with tuberculous meningitis in an immunocompetent host. Oxf Med Case Reports [Internet]. 2014, 2014, 125–8, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4370030/. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).