Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

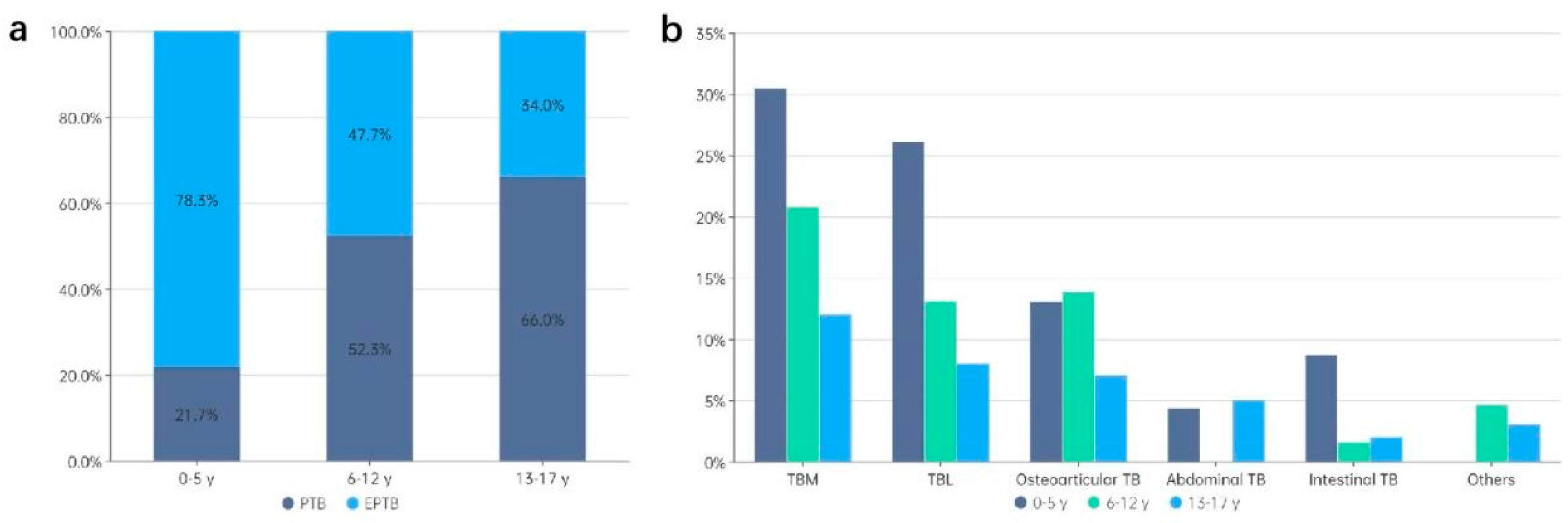

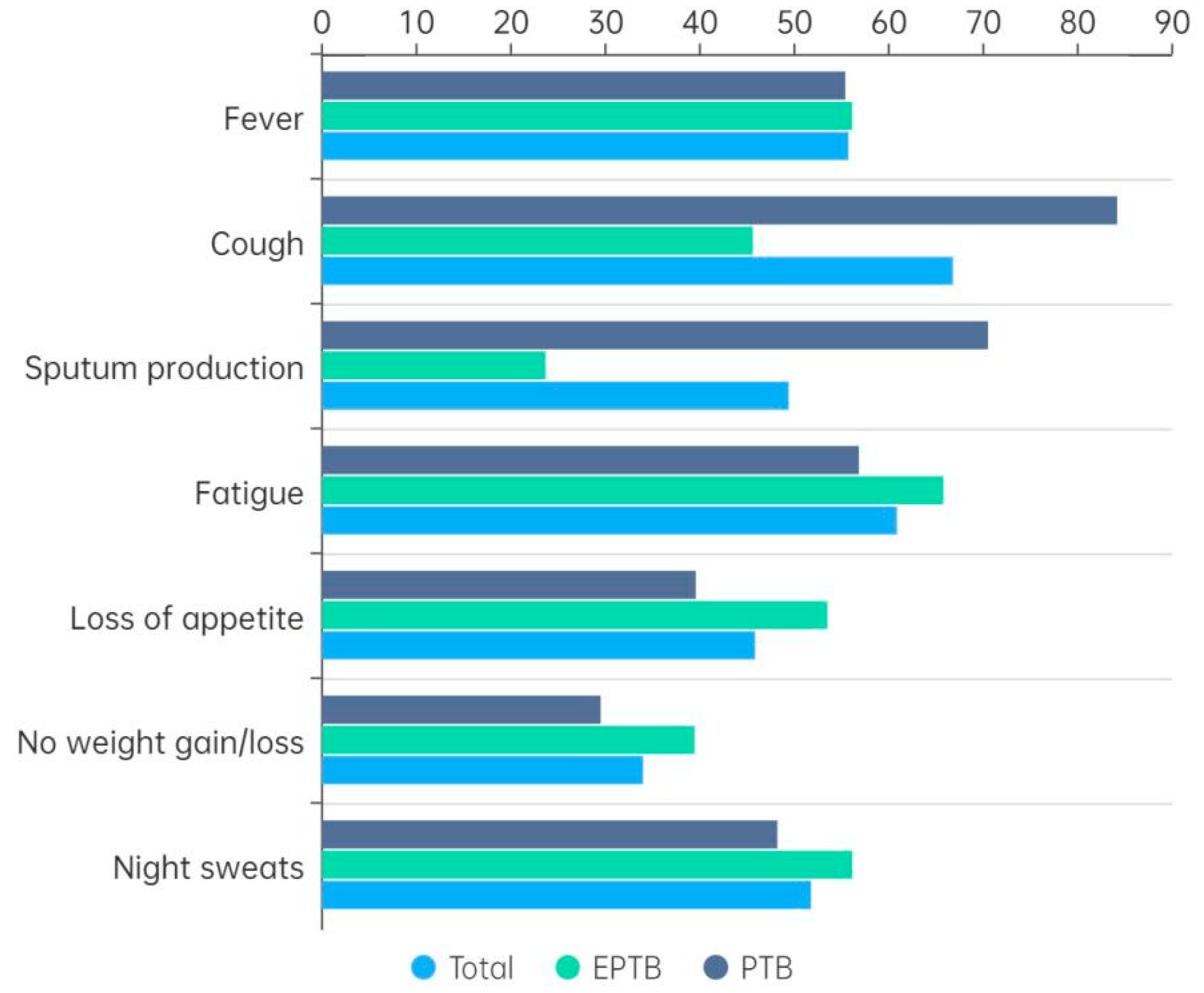

Background: Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a significant public health concern among children and adolescents in high-burden countries, including China. However, there is a paucity of literature concerning the clinical features and epidemiological characteristics of childhood TB in Xinjiang, the region with the highest TB burden in China. Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted of children and adolescents aged 0-17 years who were hospitalized with TB between January 2020 and December 2022. A comprehensive analysis of demographic, clinical and laboratory data on different types of TB was conducted, and risk factors for extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) and severe TB were explored. Results: Among the 253 children and adolescents, 55.3% had pulmonary TB (PTB) and 45.1% had EPTB. The younger children (0-5 years) were more affected by EPTB (78.3%). The most prevalent clinical symptoms were fever (82.2%), cough (79.4%), fatigue (66.4%), and night sweats (52.6%). Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) was the predominant form of EPTB, accounting for 40.4% of cases. Younger age and rural residence were significant risk factors for both EPTB and severe TB. Laboratory results demonstrated high positivity rates for tuberculin skin tests (96.1%) and interferon-γ release assays (84.5%) in all patients, with lower rates of positive smear microscopy and GeneXpert results in EPTB cases. Conclusion: The epidemiology of childhood TB in Xinjiang is characterized by a high incidence of EPTB, with a particularly high prevalence of TBM among younger children. The improvement of early diagnosis of TB in children and adolescents is of critical importance for the enhancement of disease outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Diagnosis of TB

2.3. Laboratory Tests

2.4. TB Classification

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

3.2. Distribution of TB Types by Age

3.3. Clinical Symptoms by TB Type

3.4. Risk Factors Associated with EPTB or Severe TB

3.5. Laboratory Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Clinical Trial

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| EPTB | Extrapulmonary tuberculosis |

| PTB | Pulmonary tuberculosis |

| TBM | Tuberculous meningitis |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| TBL | Lymphatic tuberculosis |

| DTB | Disseminated tuberculosis |

| TST | Tuberculin skin test |

| IGRA | Interferon-γ release assay |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette-Guérin |

| OR | Odds ratios |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization, Global tuberculosis report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Yom An, Alvin Kuo Jing Teo, Chan Yuda Huot, Sivanna Tieng, Kim Eam Khun, Sok Heng Pheng, Chhenglay Leng, Serongkea Deng, Ngak Song, Daisuke Nonaka, Siyan Yi. Barriers to childhood tuberculosis case detection and management in Cambodia: the perspectives of healthcare providers and caregivers. BMC infectious diseases. 2023; 23(1): 80. [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure Michael Ukoaka, Faithful Miebaka Daniel, Precious Miracle Wagwula, Mohamed Mustaf Ahmed, Ntishor Gabriel Udam, Olalekan John Okesanya, Adetola Babalola, Tajuddeen Adam Wali, Samson Afolabi, Raphael Augustine Udoh, Iniubong Godswill Peter, Lina Abdulhameed Maaji. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculosis in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2024; 24(1):1447. [CrossRef]

- Jing Tong, Mengqiu Gao, Yu Chen, Jie Wang. A case report about a child with drug-resistant tuberculous meningitis. BMC infectious diseases. 2023; 23(1):83. [CrossRef]

- Temesgen Yihunie Akalu, Archie C A Clements, Adhanom Gebreegziabher Baraki, Kefyalew Addis Alene. Protocol for a systematic review of long-term physical sequelae and financial burden of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. PloS one. 2023; 18(5):e0285404. [CrossRef]

- Maogui Hu, Yuqing Feng, Tao Li, Yanlin Zhao, Jinfeng Wang, Chengdong Xu, Wei Chen. Unbalanced Risk of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in China at the Subnational Scale: Spatiotemporal Analysis. JMIR public health and surveillance. 2022; 8(7):e36242. [CrossRef]

- Gunasekera KS, Zelner J, Becerra MC, et al. Children as sentinels of tuberculosis transmission: disease mapping of programmatic data. BMC medicine, 2020, 18(1): 234. [CrossRef]

- National Health and Family Planning commission of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnosis for Pulmonary tuberculosis (WS288-2017). Released on 2017-11-09. Implemented on 2018-05-01.

- National Health and Family Planning commission of the People’s Republic of China. Classification of tuberculosis (WS196-2017). Released on 2017-11-09. Implemented on 2018-05-01.

- Xi-Rong Wu, Qing-Qin Yin, An-Xia Jiao, Bao-Ping Xu, Lin Sun, Wei-Wei Jiao, Jing Xiao, Qing Miao, Chen Shen, Fang Liu, Dan Shen, Adong Shen. Pediatric tuberculosis at Beijing Children’s Hospital: 2002-2010. Pediatrics. 2012; 130(6): e1433-40.

- Mathur MB, Ding P, Riddell CA, VanderWeele TJ. Website and R package for computing E-values. Epidemiology, 2018, 29(5), e45-e47. [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele TJ & Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2017, 167(4), 268-274.

- Meng Li, Mingcheng Guo, Ying Peng, Qi Jiang, Lan Xia, Sheng Zhong, Yong Qiu, Xin Su, Shu Zhang, Chongguang Yang, Peierdun Mijiti, Qizhi Mao, Howard Takiff, Fabin Li, Chuang Chen, Qian Gao. High proportion of tuberculosis transmission among social contacts in rural China: a 12-year prospective population-based genomic epidemiological study. Emerging microbes & infections. 2022;11(1):2102-2111. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Liu, H. Y. Yao, E. Y. Liu. Analysis of factors affecting the epidemiology of tuberculosis in China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(4):450-454.

- Baazeem, M, Kruger, E, Tennant, M. Current Status of Tertiary Healthcare Services and Its Accessibility in Rural and Remote Australia: A Systematic Review. Health Sci Rev (Oxf). 2024-03-01; 100158. [CrossRef]

- Katherine C Horton, Peter MacPherson, Rein M G J Houben, Richard G White, Elizabeth L Corbett. Sex Differences in Tuberculosis Burden and Notifications in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2016;13(9): e1002119. [CrossRef]

- Shang WJ, Liu M. Epidemic trend of tuberculosis in adolescents in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2024;45(1): 78-86.

- Kaitlyn M Berry, Carly A Rodriguez, Rebecca H Berhanu, Nazir Ismail, Lindiwe Mvusi, Lawrence Long, Denise Evans. Treatment outcomes among children, adolescents, and adults on treatment for tuberculosis in two metropolitan municipalities in Gauteng Province, South Africa. BMC public health. 2019;19(1):973. [CrossRef]

- Samson Omongot, Winters Muttamba, Irene Najjingo, Joseph Baruch Baluku, Sabrina Kitaka, Stavia Turyahabwe, Bruce Kirenga. Strategies to resolve the gap in adolescent tuberculosis care at four health facilities in Uganda: The teenager’s TB pilot project. PloS one. 2024; 19(4):e0286894. [CrossRef]

- Suman Thakur, Vivek Chauhan, Ravinder Kumar, Gopal Beri. Adolescent Females are More Susceptible than Males for Tuberculosis. Journal of global infectious diseases. 2021;13(1):3-6. [CrossRef]

- Olivier Neyrolles, Lluis Quintana-Murci. Sexual inequality in tuberculosis. PLoS Med, 2009, 6(12): e1000199. [CrossRef]

- Fugang Wang, Wenxiu Zhu, Xiaomei Wang, Chao Luo, Fan Yu. Status of vitamin D levels in Karamay residents of Xinjiang province. Chin J Osteoporosis & Bone Miner Res. 2019, 12(2): 132-135.

- Huiling Wu, Maimaitiming Tuerxunjiang, Xianhua Wang, Jimeng Li. Survey on the health status of 1008 junior high school students in Changji City, Xinjiang. Journal of Medical Pest Control. 2019, 35(7):697-699.

- Hussein Hamdar, Ali Alakbar Nahle, Jamal Ataya, Ali Jawad, Hadi Salame, Rida Jaber, Mohammad Kassir, Hala Wannous. Comparative analysis of pediatric pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis: A single-center retrospective cohort study in Syria. Heliyon. 2024;10(17):e36779. [CrossRef]

- Yu Pang, Jun An, Wei Shu, Fengmin Huo, Naihui Chu, Mengqiu Gao, Shibing Qin, Hairong Huang, Xiaoyou Chen, Shaofa Xu. Epidemiology of Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis among Inpatients, China, 2008-2017. Emerging infectious diseases. 2019;25(3):457-464. [CrossRef]

- Ping Chu, Yan Chang, Xuan Zhang, Shujing Han, Yaqiong Jin, Yongbo Yu, Yeran Yang, Guoshuang Feng, Xinyu Wang, Ying Shen, Xin Ni, Yongli Guo, Jie Lu. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis among pediatric inpatients in mainland China: a descriptive, multicenter study. Emerging microbes & infections. 2022;11(1):1090-1102. [CrossRef]

- Melanie M Dubois, Meredith B Brooks, Amyn A Malik, Sara Siddiqui, Junaid F Ahmed, Maria Jaswal, Farhana Amanullah, Mercedes C Becerra, Hamidah Hussain. Age-specific Clinical Presentation and Risk Factors for Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis Disease in Children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2022;41(8):620-625. [CrossRef]

- Sadhna B Lal, Rishi Bolia, Jagadeesh V Menon, Vybhav Venkatesh, Anmol Bhatia, Kim Vaiphei, Rakesh Yadav, Sunil Sethi. Abdominal tuberculosis in children: A real-world experience of 218 cases from an endemic region. JGH open. 2020;4(2):215-220. [CrossRef]

- Elena Bonifachich, Monica Chort, Ana Astigarraga, Nora Diaz, Beatriz Brunet, Stella Maris Pezzotto, Oscar Bottasso. Protective effect of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination in children with extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, but not the pulmonary disease. A case-control study in Rosario, Argentina. Vaccine. 2006; 24(15):2894-9. [CrossRef]

- Qiong Liao, Yangming Zheng, Yanchun Wang, Leping Ye, Xiaomei Liu, Weiwei Jiao, Yang Liu, Yu Zhu, Jihang Jia, Lin Sun, Adong Shen, Chaomin Wan. Effectiveness of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination against severe childhood tuberculosis in China: a case-based, multicenter retrospective study. International journal of infectious diseases. 2022; 121:113-119. [CrossRef]

- Wan-Li Kang, Gui-Rong Wang, Mei-Ying Wu, Kun-Yun Yang, A Er-Tai, Shu-Cai Wu, Shu-Jun Geng, Zhi-Hui Li, Ming-Wu Li, Liang Li, Shen-Jie Tang. Interferon-Gamma Release Assay is Not Appropriate for the Diagnosis of Active Tuberculosis in High-Burden Tuberculosis Settings: A Retrospective Multicenter Investigation. Chinese medical journal. 2018; 131(3):268-275. [CrossRef]

- Miettinen OS. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol, 1974; 99:325-32. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n(%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 101 (39.9) |

| Female | 152 (60.1) |

| Age group, y | |

| 0-5 | 23 (9.1) |

| 6-12 | 130 (51.4) |

| 13-17 | 100 (39.5) |

| Residence | |

| City | 58 (22.9) |

| County | 52 (20.6) |

| Rural | 143 (56.5) |

| BCG vaccination | |

| Yes | 108 (42.7) |

| No Unknown |

9 (3.6) 136 (53.7) |

| Time from onset of symptoms to hospital visit, d | |

| 0-30 | 138 (54.5) |

| 31-60 | 35 (13.8) |

| 61-90 | 12 (4.7) |

| >90 | 68 (26.9) |

| TB type | |

| PTB | 139 (54.9) |

| EPTB | 114 (45.1) |

| Tuberculous meningitis | 46/114 (40.4) |

| Lymphatic TB | 31/114 (27.2) |

| Osteoarticular TB | 28/114 (24.6) |

| Abdominal TB | 6/114 (5.3) |

| Intestinal TB | 6/114 (5.3) |

| Contact history | |

| Yes | 49 (19.4) |

| No | 93 (36.7) |

| Unknown | 111 (43.9) |

| Severity of TB | |

| Severe | 79 (31.2) |

| Non-severe | 174 (68.8) |

| Clinical manifestations | |

| Fever | 141 (55.7) |

| Cough | 169 (66.8) |

| Sputum production | 125 (49.4) |

| Fatigue | 154 (60.9) |

| Loss of appetite | 116 (45.8) |

| No weight gain or loss | 86 (34.0) |

| Night sweats | 131 (51.8) |

| Characteristics | Total (n=253) | PTB (n=139) | EPTB (n=114) | Crude RR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | P Value | E value | PAF | |

| Age groups, y | ||||||||||

| 0-5 | 23 | 5 (21.7) | 18 (78.3) | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. | |||

| 6-12 | 130 | 68 (52.3) | 62 (47.7) | 0.609 (0.460-0.807) | <0.001 | 0.557 (0.429-0.724) | <0.001 | 2.99 | -40.9 | |

| 13-17 | 100 | 66 (66.0) | 34 (34.0) | 0.434 (0.307-0.615) | <0.001 | 0.413 (0.298-0.571) | <0.001 | 4.28 | -56.2 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 101 | 57 (56.4) | 44 (43.6) | 1.00 | Ref. | |||||

| Female | 152 | 82 (53.9) | 70 (46.1) | 1.057 (0.798-1.400) | 0.698 | |||||

| Residence | ||||||||||

| City | 58 | 40 (69.0) | 18 (31.0) | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. | |||

| County | 52 | 25 (48.1) | 27 (51.9) | 1.673 (1.052-2.662) | 0.030 | 1.732 (1.115-2.691) | 0.014 | 2.86 | 8.7 | |

| Rural | 143 | 74 (51.7) | 69 (48.3) | 1.555 (1.022-2.365) | 0.039 | 1.666 (1.102-2.519) | 0.016 | 2.72 | 22.6 | |

| BCG vaccinated | ||||||||||

| Yes | 108 | 63 (58.3) | 45 (41.7) | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. | |||

| No | 9 | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | 1.867 (1.233-2.825) | 0.003 | 1.727 (1.164-2.561) | 0.007 | 2.85 | 1.5 | |

| Unknown | 136 | 74 (54.4) | 62 (45.6) | 1.094 (0.820-1.461) | 0.542 | 1.115 (0.843-1.477) | 0.446 | 1.47 | 5.5 | |

| Time from onset of symptoms to hospital visit, d | ||||||||||

| 0-30 | 138 | 77 (55.8) | 61 (44.2) | 1.00 | Ref. | |||||

| 31-60 | 35 | 20 (57.1) | 15 (42.9) | 0.970 (0.633-1.485) | 0.887 | |||||

| 61-90 | 12 | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) | 0.943 (0.470-1.889) | 0.868 | |||||

| >90 | 68 | 35 (51.5) | 33 (48.5) | 1.098 (0.807-1.494) | 0.553 | |||||

| Contact history | ||||||||||

| Yes | 49 | 26 (53.1) | 23 (46.9) | 1.00 | Ref. | |||||

| No | 93 | 51 (54.8) | 42 (45.2) | 0.962 (0.663-1.396) | 0.839 | |||||

| Unknown | 111 | 62 (55.9) | 49 (44.1) | 0.940 (0.654-1.353) | 0.741 | |||||

| Diagnostic Test | Total (n=253) | PTB (n=139) | EPTB (n=114) | P value |

| TST (positive) | 99/103 (96.1%) | 63/64 (98.4%) | 36/39 (92.3%) | 0.151 |

| IGRA (positive) | 196/232 (84.5%) | 107/128 (83.6%) | 89/104 (85.6%) | 0.678 |

| Smear microscopy (positive) | 35/225 (15.6%) | 29/130 (22.3%) | 6/95 (6.3%) | 0.001 |

| MTB culture (positive) | 59/176 (33.5%) | 38/100 (38%) | 21/76 (27.6%) | 0.149 |

| Gene Xpert (positive) | 82/183 (44.8%) | 60/113 (53.1%) | 22/70 (31.4%) | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).