1. Introduction

It is estimated that 1.25 million children developed tuberculosis (TB) in 2022, but half of them were not diagnosed and/or not reported to the national TB programs.1 One of the reasons for high number of missing cases among children is the lack of confidence or competence of the healthcare worker to diagnose TB in children and the poor diagnostic performance of the currently available bacteriological tests in young children. Bacteriological confirmation of pulmonary TB (PTB) in children is challenging because of its paucibacillary nature and the difficulty in collecting sputum.2 The yield of bacteriological examination is low, around 15% for smear microscopy and 40% for culture among children admitted to hospital, and even lower in children attending ambulatory care, who tend to have less severe disease.

Clinicians often need to decide whether to treat for TB while awaiting the result of microbiology tests, or when the test is negative or indeterminate, or when there is no test due to inability to collect an appropriate sample or no access to the laboratory diagnostic.

Therefore, the decision is often made clinically based on a combination of symptoms, evidence of TB infection—either tuberculin skin testing (TST) or interferon gamma release assay (IGRA)—and TB-related abnormalities on the chest X-ray (CXR). The clinical diagnosis of PTB can be challenging, particularly in young children.3 The usual symptoms of PTB (chronic cough, prolonged fever, and weight loss or failure to thrive) are common in young children living in poverty and may be caused by conditions other than TB, and so lack specificity. Tests to support a clinical diagnosis such as CXR and tests for TB infection are not always available in primary level health facilities in endemic settings. Various scoring systems have been developed and applied in some countries for many decades: these are usually based on expert opinion with adaptation based on local experience.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 These scoring systems have not been well validated because evaluation of diagnostic accuracy is limited by the lack of a “gold” reference standard. Despite these limitations, a clinical approach that includes a scoring system has value for guiding health care workers’ decision making for diagnosing and treating TB in children.4

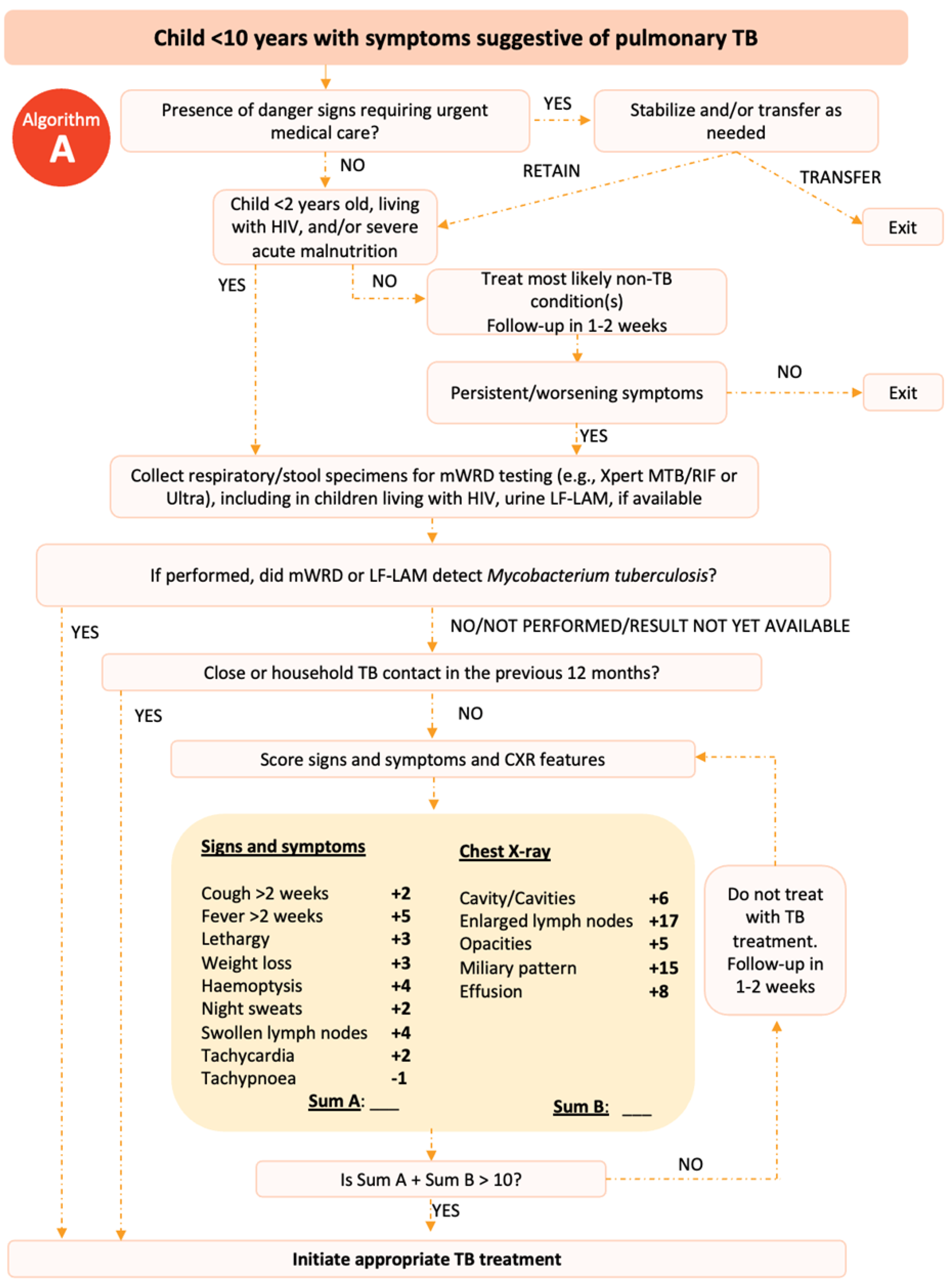

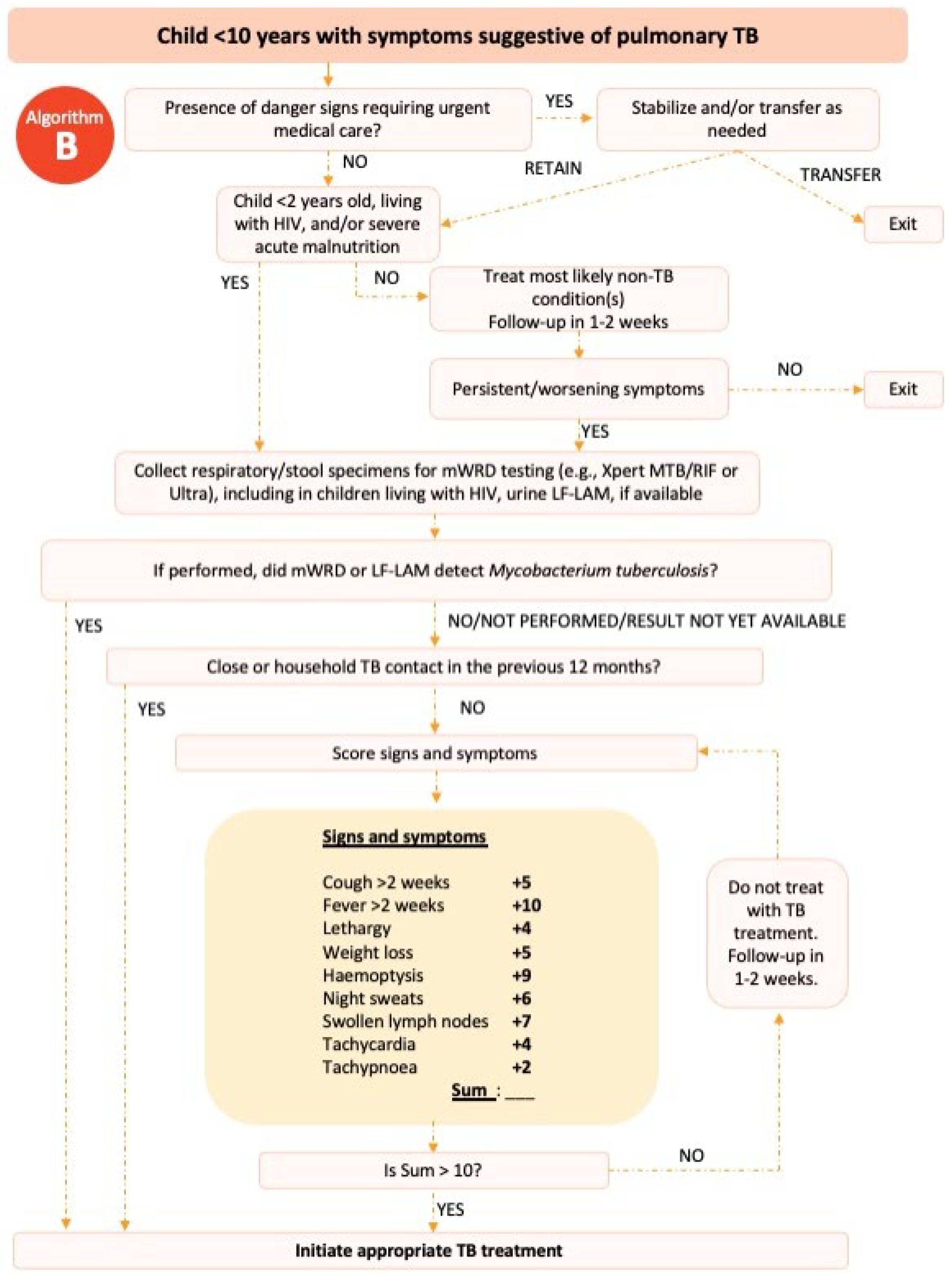

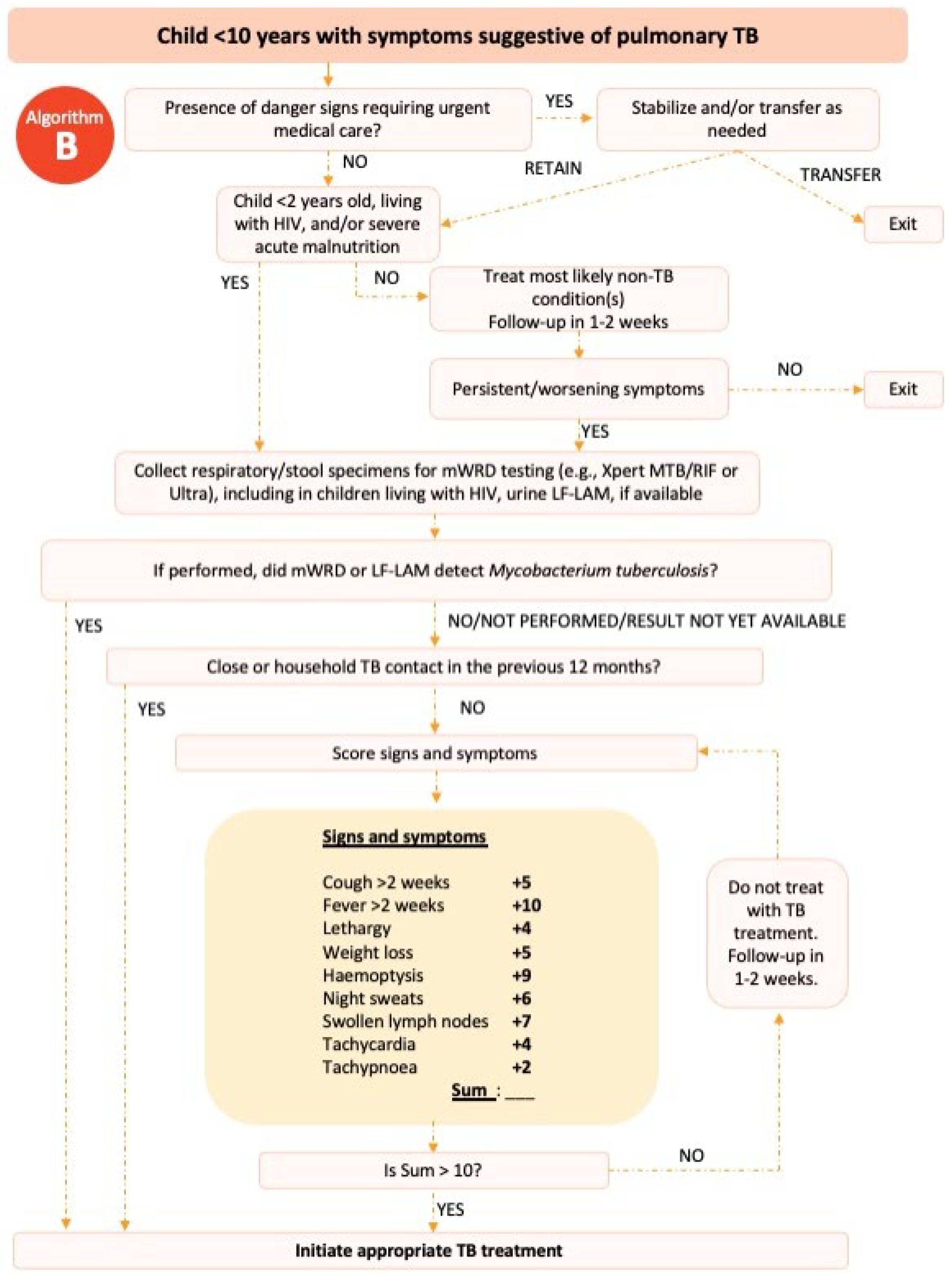

In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) published an example of a treatment decision algorithm for children aged <10 years (

Figure 1 &2).

11,12 The treatment decision algorithm included two scoring systems: one that scored CXR findings; and one that did not for when CXR was unavailable or uninterpretable. The weighting and cut-offs for these scoring systems were developed and validated using data from over 4000 children with presumptive PTB.

13 The cut-off scores were chosen prioritizing sensitivity over specificity to minimize the numbers of children with TB not treated while accepting that this would lead to overdiagnosis and the treatment of children without TB.

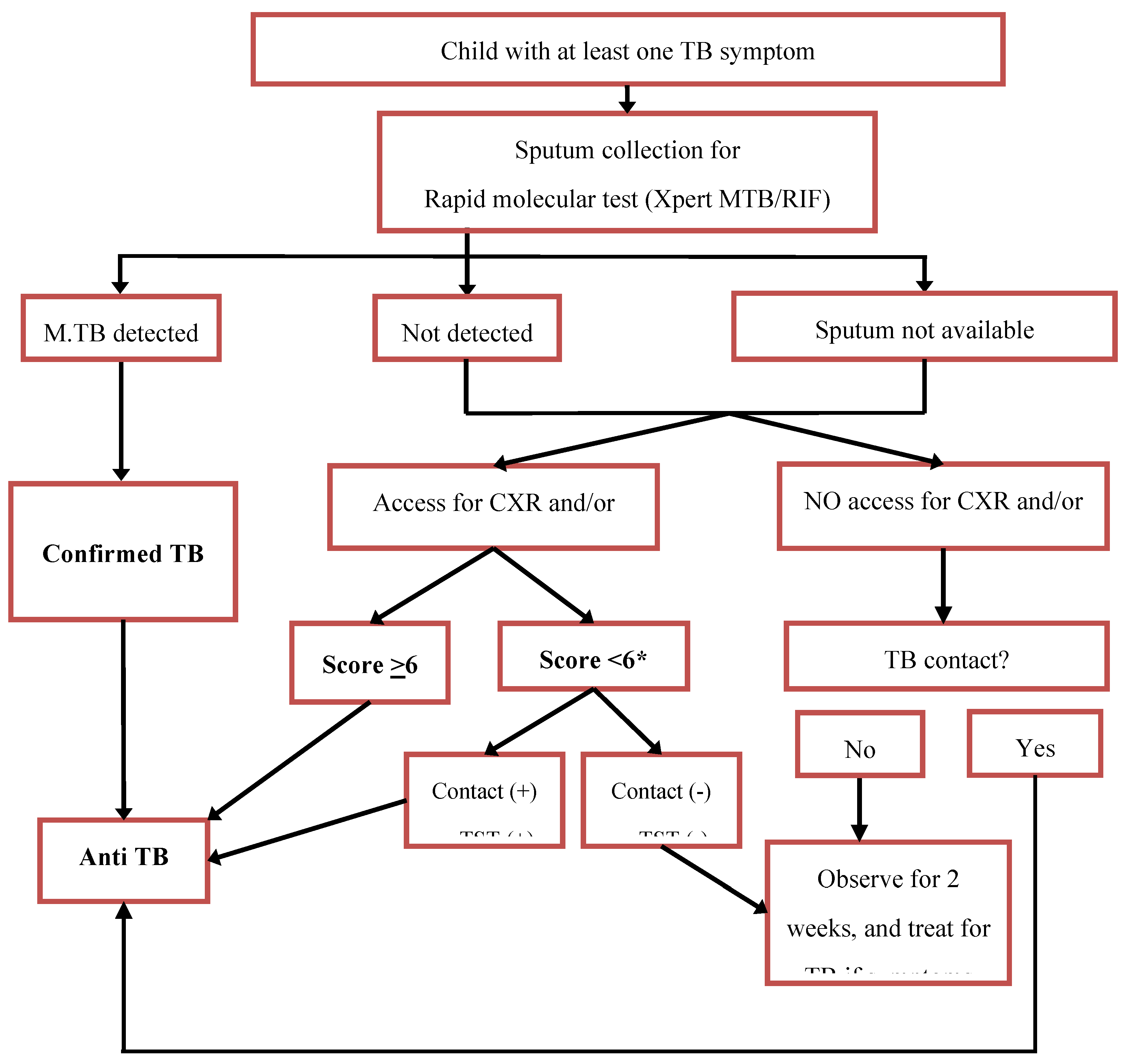

In Indonesia, the Indonesia Paediatric Society (IPS) developed a scoring system to diagnose TB in children in 2000 (

Table 1), with a total score of

> 6 is diagnosed as TB disease. This scoring system had recognized limitations such as the potential for overdiagnosis and inability for some health facilities to perform CXR or TST.

14 Therefore, in 2016 the IPS in collaboration with the Indonesian National TB Program (NTP) developed an algorithm to diagnose TB in children, which incorporated the scoring system and provided options for those who work in limited resource settings, in which access to CXR or TST is limited (

Figure 2). Following the release of the WHO treatment decision algorithm in 2022, we planned to revise the approach to diagnosis and treatment decisions for children in Indonesia. We describe the evaluation of the WHO algorithm in our setting and the process to develop the latest Indonesian algorithm.

2. Methods

2.1. Evaluation of the WHO Treatment Decision Algorithm

We conducted a retrospective study, involving 10 hospitals (eight district hospitals and two provincial hospitals) in five provinces (West Sumatra, West Java, Yogyakarta, East Java, and West Nusa Tenggara) in Indonesia. The study included all children aged 0-10 years who were evaluated for PTB by attending doctors in the study hospitals in 2022 based on an ICD-10 code of Z03.0 (observation of suspected tuberculosis), A15 (respiratory tuberculosis, bacteriologically and histologically confirmed), A16 (respiratory tuberculosis not confirmed bacteriologically, molecularly or histologically), or A19 (miliary tuberculosis) in their medical record. We then reviewed these records and excluded children with incomplete medical record data; and children with comorbidities other than HIV or malnutrition.

For children included in the study, we then retrospectively reviewed their medical records and extracted data on symptoms, signs, results of TST or IGRA, CXR, sputum laboratory test (smear or rapid molecular diagnostic) and the final diagnosis made by the attending doctor at each hospital. We only recorded the interpretation of CXR and TST written in the medical record. A panel of paediatricians with child TB expertise and experience (RT, FFY and DAW) then assessed the data for each child using two different to make a diagnosis: the WHO algorithm published in 2022 (

Figure 1 if information on the interpretation of CXR was available and

Figure 2 if information on the interpretation of CXR was not available) and the Indonesia algorithm developed in 2016 (

Figure 3). Each paediatrician assessed all patients independently, with discordance resolved by consensus to reach a final TB diagnosis. We then compared the number, proportion and agreement of TB diagnosis made by the attending doctor with those made by the expert panel using the WHO algorithm and those made by the expert panel using the 2016 Indonesian algorithm. We also did a detailed review in each case.

2.2 Development of the New Algorithm

Based on the findings of the evaluation, the study team developed a proposed new algorithm by revising the 2016 algorithm with adaptations informed by the 2022 WHO algorithm. The proposed algorithm was then reviewed through a series of in-person and online meetings, attended by child TB experts from the IPS, representatives from the NTP, general practitioners from primary health centers, pediatricians from district hospitals, the province and district TB officers, and representative from non-government organizations to reach consensus.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA, presented as counts, mean or median and proportion, as appropriate. Cohen’s Kappa was used to evaluate agreement between: the expert panel in making the diagnosis; the attending doctors and the expert panel; and the WHO algorithm and the 2016 Indonesian algorithm. Kappa scores were categorized using the following cutoffs: 0 = no agreement, 0.10–0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial, 0.81–0.99 = near perfect, 1 = perfect). Comparison was also made on patient characteristics between those diagnosed as TB or as not TB with full agreement by all three approaches using Chi-square test for categorical variables, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for medians, with a p value of less than 0.05 considered significant.

2.4. Ethical Clearance

We obtained ethical approval from the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

3. Results

A total of 523 eligible children were included to the study. The characteristics of the children are summarized in

Table 2. More than half of the children were less than 5 years of age. The most common symptom at initial presentation was cough. HIV test was not routinely performed in all children and of those who were tested, seven children had a positive result. Most children underwent TST and CXR as part of TB work-up. Microbiology tests were performed in 51.2% of the children. Of these, 13 were bacteriologically confirmed: eight on Xpert MTB/RIF, six on sputum smear and one on both.

The proportion of children diagnosed with TB by the attending doctors was 70.9% (371 / 523), diagnosed by the expert panel using WHO algorithm was 56.4% (295 / 523) and using the Indonesia guideline was 47% (246 / 523). The agreement of TB diagnosis between the attending doctor and the expert panel using the WHO algorithm was fair (Cohen’s Kappa 0.27); meanwhile the agreement when the expert panel using the Indonesia algorithm was moderate (Cohen’s Kappa 0.45). The agreement between the WHO algorithm and the Indonesia algorithm was moderate with Cohen’s Kappa of 0.42.

By all three approaches, there was full agreement on the diagnosis of TB in 185 children and that 99 children did not have TB. The characteristics of these children are presented and compared in

Table 3. The ages of these groups were similar but those diagnosed with TB were significantly more likely to have a known TB contact or a CXR with abnormalities suggestive of TB.

To develop a new algorithm in Indonesia, we analyzed the above results and reviewed each case. Our findings reveal that attending doctors diagnosed a larger number of TB cases (371; 71%) compared to the expert panel, either using the Indonesia algorithm (246; 47%) or the WHO algorithm (295; 56.4%). A detailed review of each case revealed concerns with both algorithms, which may lead to overdiagnosis. We revised the Indonesian algorithm with adaptation from the WHO algorithm. In the new algorithm, there is opportunity for a doctor to make decisions based on each condition of the patient (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This study documented that doctor in hospital setting in Indonesia diagnosed TB in more children than the expert panel did. Confirming a tendency towards overdiagnosis challenging due to the lack of a reference standard, and quantifying this tendency is complicated as the WHO and Indonesia algorithms also have a potential bias towards overdiagnosis and overtreatment. A tendency towards overdiagnosis is generally considered more acceptable than a tendency to not detect and treat children with TB given the risk of severe disease and death, and the low risk of adverse event of anti TB treatment in this population.15 However, best practice would indicate that unnecessary treatment should be minimized whenever possible. While treatment decision algorithms serve as valuable guides, the diverse characteristics of individual patients and varying access to diagnostic tools require clinicians to make a clinical decision based on each patient’s findings. Therefore, ongoing clinical training with monitoring of practice and mentorship are necessary to support healthcare workers in providing optimal decision.

Our careful review of the WHO algorithm highlighted that a decision to treat TB disease could easily be reached by a single abnormal finding, such as hilar lymphadenopathy or a positive test for infection. Hilar lymph nodes enlargement is the most common radiological finding in the CXR of children with TB16,17 and represents a highly specific radiological abnormality for PTB in children. However, interpreting this finding can be very challenging especially without training.18,19,20 The hilum, which is composed of pulmonary arteries and veins, major bronchi, and lymph nodes, is the most complex region to interpret in the chest radiogram.21,22 Previous studies documented that inter and intra-observer agreement in interpreting hilar lymph node enlargement on the chest radiogram was poor to moderate.23,24,25 Insufficient experience as well as lack of competence of doctors in reading chest radiogram in children should be taken into account. Progress is being made in computer-aided detection of common radiological patterns of TB in children, which offer promising solutions to address these challenges.

TST and IGRA are tests for TB infection and cannot distinguish between TB disease and infection. Despite the limitation, the tests can help clinician to decide the diagnosis of TB in children when history of close contact with a TB patient was unknown or unclear. This was a reason for their inclusion in the Indonesia scoring system and algorithm. However, this may also lead to overdiagnosis when the diagnosis is made based on positive result of TST/IGRA and symptom only. On the other hand, the unavailability and lack of sustainability of these tests in health facilities can be a barrier for diagnosis if they are required as an essential component of the assessment. To address this issue, in 2016 the Indonesia algorithm was developed to include guidelines for making diagnostic decisions in the absence of TST/IGRA and CXR. This allows clinicians to start TB treatment without delay even if these tests are not available.

The new algorithm for child TB in Indonesia adopts some of the approaches in the WHO algorithm, such as identification of danger signs and high-risk children. We did not adopt the WHO scoring system but used the scoring system developed by the IPS because of time and resources constraints to conduct a study to develop a new scoring system. This is one of the limitations of the new algorithm because the Indonesia scoring system was developed based solely on literature review and expert consensus, rather than on the local data from Indonesia. Additionally, how the variables were chosen and how the weight of each variable was determined, is not well-described. In the revised algorithm we included an option allowing healthcare workers to make their own clinical decisions if the child’s clinical condition does not align with the algorithm’s guidelines. While this flexibility is intended to accommodate individual clinical judgement, it may not be suitable for all healthcare workers. A simpler and “strict” algorithm may be preferable, in particular for those with less clinical confidence and experience. There is also a risk that allowing healthcare workers discretion could lead to varying diagnostic approaches and potential overdiagnosis. As for any new tool, training and dissemination with ongoing review and mentoring of healthcare workers will be vital for uptake and maintaining quality of care.

Ideally, external validation of the WHO algorithm should be conducted in a prospective design study and compared to the reference standard of microbiological confirmation. The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which relies on data from medical record without a reference standard. This study was not aimed to evaluate the diagnostic values of the three approaches, but rather to evaluate their agreement. Although this may not provide robust scientific evidence, it gives a description of the diagnostic yield of both WHO and Indonesia algorithm for tuberculosis in children. This information is important as one of the considerations for implementing the new WHO treatment decision algorithm in Indonesia. Another significant limitation was that the study did not review the chest radiograph directly; instead, it used interpretations recorded in the medical records. Further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the Indonesia childhood TB algorithm and to develop a new scoring system, including assessment of the diagnostic value, feasibility and cost-effectiveness.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that diagnosing TB in children using algorithm and scoring systems has limitations in interpretation and accuracy. While a simple algorithm is essential to assist healthcare workers in making clinical diagnosis and treatment decision, especially at the peripheral levels of care, it is challenging to develop a universal algorithm applicable across all patient contexts, resources and skill levels. A prospective evaluation of the new algorithm is needed to assess its potential for overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis, as well as the acceptability and feasibility is required.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, R.T.; methodology, R.T. and F.F.Y.; software, R.T.; validation, R.T., F.F.Y., and D.A.W.; formal analysis, R.T. and M.B.A.; investigation, R.T.; resources, B.N., M.B.A., F.M., S.A.K.I., E.O.; data curation, R.T. and F.F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, R.T., F.F.Y., D.A.W., B.N., M.B.A., F.M., S.A.K.I., T.T.P., and E.O.; visualization, R.T.; supervision, R.T., F.F.Y.,D.A.W., B.N.; project administration, R.T.; funding acquisition, R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. .

Funding

This research was funded by the WHO Indonesia under Grant Number 203028579, as part of the development of the revised national guidelines for childhood tuberculosis. .

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Medical Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada (protocol KE/1157/09/2022) on 14th September 2022. .

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. .

Data Availability Statement

Due to data privacy concerns, data is not made publicly available. However, reasonable data requests may be granted through contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledged Professor Stephen M Graham for help with writing the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

TB Tuberculosis

PTB Pulmonary tuberculosis

WHO World Health Organization

TST Tuberculin skin test

IGRA Interferon Gamma Released Assay

CXR Chest X-Ray

IPS Indonesia Paediatric Society

NTP National tuberculosis program

References

- World Health Organization. 2023. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. Geneva: World Health organization.

- Detjen AK et al. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 451–61. [CrossRef]

- Marais BJ et al. A refined symptom-based approach to diagnose pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1350-9. [CrossRef]

- Graham SM. The use of diagnostic systems for tuberculosis in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78(3):334-9. [CrossRef]

- Edwards K. The diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis. PNG Med J. 1987;30:169–78.

- Nair PM, Philip E. A scoring system for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. Indian Pediatr. 1981;18:299–303.

- Toledo A et al. Diagnostic criteria for pediatric tuberculosis. Rev Mex Pediatr. 1979;46:239–43.

- Sant’Anna CC, Santos MARC, Franco R. Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis by score system in children and adolescents: a trial in a reference center in Bahia, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2004;8:305–10. [CrossRef]

- Santos SC et al. Scoring system for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in indigenous children and adolescents under 15 years of age in the state of Mato Grosso du Sul, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(1): 84-91.

- Hatherill M et al. Structured approaches for the screening and diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis in a high prevalence region of South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(4):312-20. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis. Module 5: Management of tuberculosis in.

- children and adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2022. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: module 5: Management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Gunasekera KS et al. Development of treatment-decision algorithms for children evaluated for pulmonary tuberculosis: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023 May;7(5):336-346. [CrossRef]

- Triasih R, Graham SM. Limitations of the Indonesian Pediatric Tuberculosis Scoring System in the context of child contact inves-.

- tigation. Paediatr Indones. 2011;51:332-7.

- Frydenberg AR, Graham SM. Toxicity of first-line drugs for treatment of tuberculosis in children: review. Trop Med Int Health 2009; 14: 1329–37. [CrossRef]

- Marais BJ et al. Radiographic signs and symptoms in children treated for tuberculosis: possible implications for symptom-based.

- screening in resource-limited settings. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006; 25: 237–240.

- Kruk A et al. Symptom-based screening of child tuberculosis contacts: improved feasibility in resource- limited settings. Pediatrics 2008; 121: e1646–e1652.

- Triasih R et al. An evaluation of chest X-ray in the context of community-based screening of child tuberculosis contacts. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(12):1428-34. [CrossRef]

- Swingler GH et al. Diagnostic accuracy of chest radiography in detecting mediastinal lymphadenopathy in suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child. 2005 Nov;90(11):1153-6. [CrossRef]

- George A et al. Intrathoracic tuberculous lymphadenopathy in children: a guide to chest radiography. Pediatr Radiol. 2017 Sep;47(10):1277-1282. [CrossRef]

- Andronikou S et al. Usefulness of lateral radiographs for detecting tuberculous lymphadenopathy in children—confirmation using.

- sagittal CT reconstruction with multiplanar crossreferencing. S Afr J Radiol 2012; 16: 87–92.

- Sarkar J et al. Approach to unequal hilum on chest X-ray. J Assoc Chest Phys 2013; 1: 32–37.

- Du Toit G, Swingler G, Iloni K. Observer variation in detecting lymphadenopathy on chest radiography. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2002; 6: 814–817.

- Balabanova Y et al. Variability in interpretation of chest radiographs among Russian clinicians and implications for screening programmes: observational study. BMJ 2005; 331: 379–382. [CrossRef]

- Zellweger J P et al. Intra-observer and overall agreement in the radiological assessment of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006; 10: 1123–1126.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).