1. Introduction

The United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHLM) declaration on tuberculosis (TB) includes global targets to accelerate action to prevent and treat TB among children and adolescents [

1]. However, adolescent TB was a neglected area until a road map of for fighting TB among children (<15 years) and adolescents (10–19 years) globally was release in 20181 and a similar roadmap focusing on Ethiopia specifically was released in 2019 [

2]. Yet, adolescents have their own peculiar characteristics that expose them for TB, including homelessness, incarceration, and substance use [

3]. Also, the Ethiopian Health Management Information System (HMIS) started capturing routine data disaggregated for children and adolescents in 2021.

As they are transitioning between child and adult health services, adolescents face specific age-related challenges in accessing appropriate care in high burden settings for TB, which could be due to the absence of dedicated adolescent health services that include TB [

4,

5]. Evidence has also shown that adolescents have a high prevalence of TB [

6] and experience a high lost-to-follow-up rate [

7]. Adolescents are also a recognized key population in the global human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, and having HIV can make them susceptible to developing TB disease [

8].

In general, the proportion of males with notified TB cases is higher than females in Ethiopia, which could be due to economic and access factors inherent in the male dominated society, where men have more power than women and some level of privileged access to health care9 and accordingly to diagnostic services. Yet, a simple male-to-female TB disease disaggregation without considering different age categories could be misleading. Disaggregation of gender-based TB in the different age categories accordingly could be important for TB prevention and control, as risks factors could vary depending on both age and gender [

10,

11]. Specifically, TB among adolescents remains neglected in that the characteristics of TB among that age group have not been well described or understood and interventions have not been designed to address their specific needs. For instance, routine national data failed to capture the 10–19-years age category based on type of TB [

6,

7].

Few interventions target TB among adolescents in Ethiopia, and those that do, such as school screening campaigns, tend to be erratic. Yet, school children and teenagers (10–19 years) usually interact with one another and therefore are easily exposed to infection [

12,

13,

14]. Also, little has been described about the implications of sex and gender for the surveillance and response to TB program in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study is to describe types of TB based on gender, age (including adolescent), and geographic setting in Ethiopia to inform future policy and service delivery improvements to better serve these communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Settings

Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa, and adolescents make up 24% of its general population [

15]. The country also has relatively high TB rates, with the respective incidence and mortality estimates of 126 and 17 per 100,000 population in 2022. In Ethiopia 4% of TB cases are also HIV infection9 while HIV prevalence in the general population is 0.9% and is higher among women (1.2%) than men (0.6%) [

16].

2.2. Interventions

Led by Management Sciences for Health, the USAID Eliminate TB Project has advocated TB prevention and reduction among adolescents since 2021. The project collaborated with the National TB Program to include age disaggregation of adolescents in the TB reporting program. The national TB guidelines and training manual, as well as monitoring and evaluation training materials, were revised to include childhood and adolescent TB. The Eliminate TB Project has also supported the national TB program in building the capacity of health care personnel working in pediatrics and TB clinics on childhood and adolescent TB. Accordingly, the adolescent age category (10-19 years) became part of the TB program reporting system in July 2021.

2.3. Data Source

Ministry of Health District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2)-based reporting was used to collate TB data from July 2022 to March 2024 based on type of TB, age, gender, HIV status, geographic setting, and region.

2.4. Data Quality

Lot quality assurance sampling (LQAS) and quarterly data quality assurance systems were used in health facilities and districts in the country to ensure data quality. Each reporting unit checked the completeness and consistency of data before sending it to the next level.

2.5. Data Analysis

The male-to-female ratio was described among age categories of 5 years interval (up until >=65 years), HIV positive status, types of TB (extra-pulmonary TB [EPTB], clinically diagnosed pulmonary TB [clinical PTB], and bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB (BCPTB)), and geographic categories (among agrarian, pastoralist, and city administration of the country) using error bar graphs. In addition, bivariate and multivariable logistics analyses were undertaken for the male-to-female ratio of TB based on age categories (<5 years, 5–9 years, 10–19 years (adolescent), and >=20 years), types of TB, regions in Ethiopia, and geographic categories using STATA version 17. A two-sample proportion test was applied to compare the BCTB among adolescents and adults.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Review Committee of each Regional Health Bureau (RHB) reviewed and approved the study protocol using the routine DHIS2. As the DHIS2 data are aggregate data, they do not capture any personal identifying information.

3. Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

In July 2022–March 2024, 290,450 TB cases were detected in Ethiopia—42.6% (123,871) among females and 9.4% (27,160) among children under 15 years of age. The range for the proportion of TB among females was 20.7%; 52.5% in the 10–14-years age category and 31.8% in the >=65-years category. Young female adolescent in the 10–14-years age group have the highest proportion of TB among females at 52.5%.

Of TB patients with HIV infections, 52.5% were among females, 55.3% were among female older children and young adolescent, and 52.9% were among adults above 15 years of age.

Overall, adolescents account for 14.5% (42,228) of all TB cases, and the proportion of BCPTB among them was 47.8% (20,185). Of BCPTB adolescents, 47.3% were among females, even though females account for only 44% of all TB patients. Pastoralist regions (Benishangul Gumuz, Afar, and Gambella) have higher proportions of TB cases among males (>60%) (

Table 1).

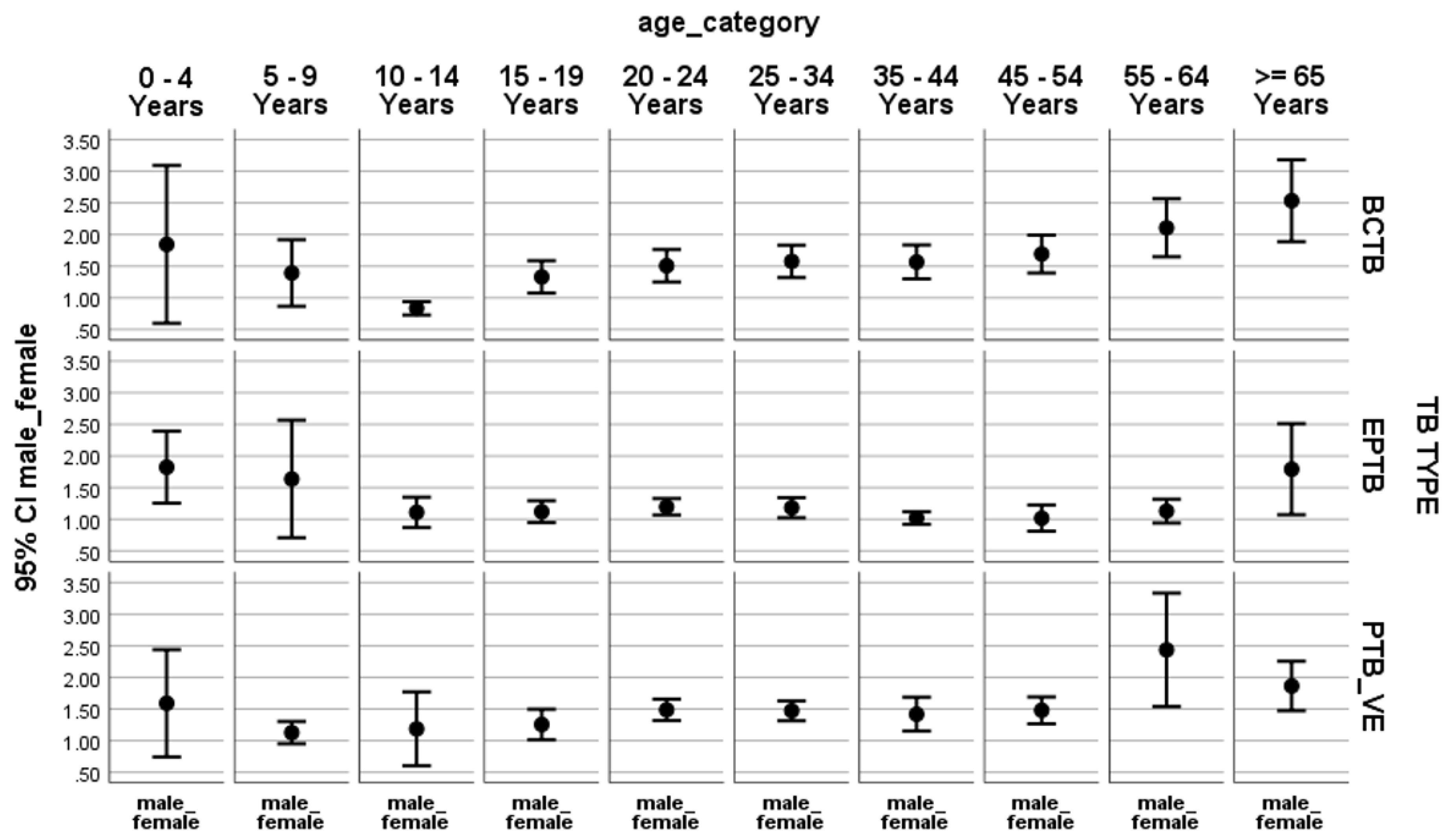

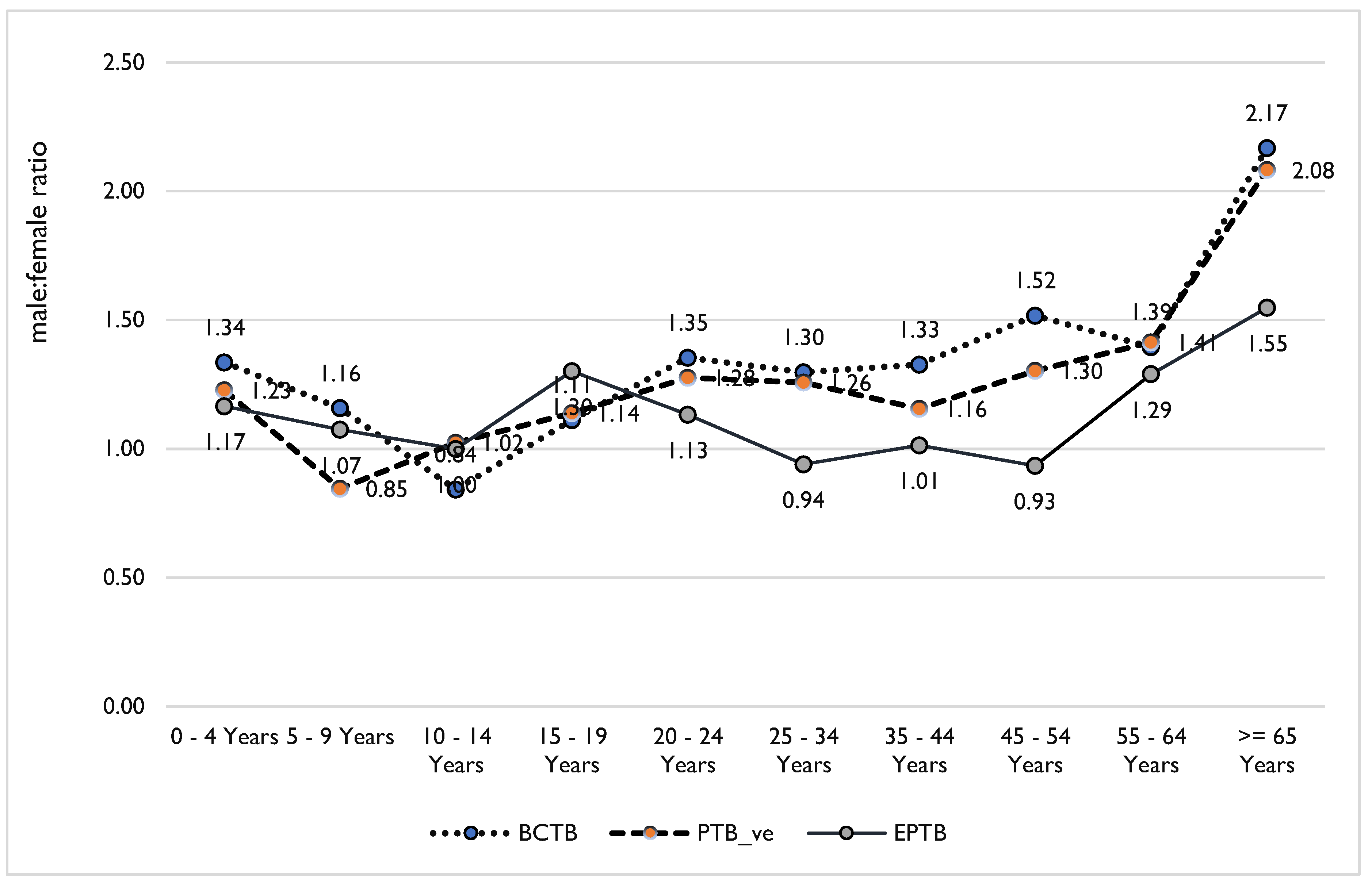

For all forms of TB, the male-to-female ratio (M:F) is greater than one for the age groups older than 55 years. Exceptionally, the M:F is less than one for the 10–14-years age group. Among the BCPTB cases, M:F was less than one in children 10-14 years of age (or young adolescents) but greater than one and steadily increasing in the age categories older than that. For EPTB, M:F ran around one (tending towards females), except in the 0–4-years, 20–34-years, and >=65-years age categories. Among clinical PTB patients, M:F is more than one categorically in adults and about one in children (

Figure 1).

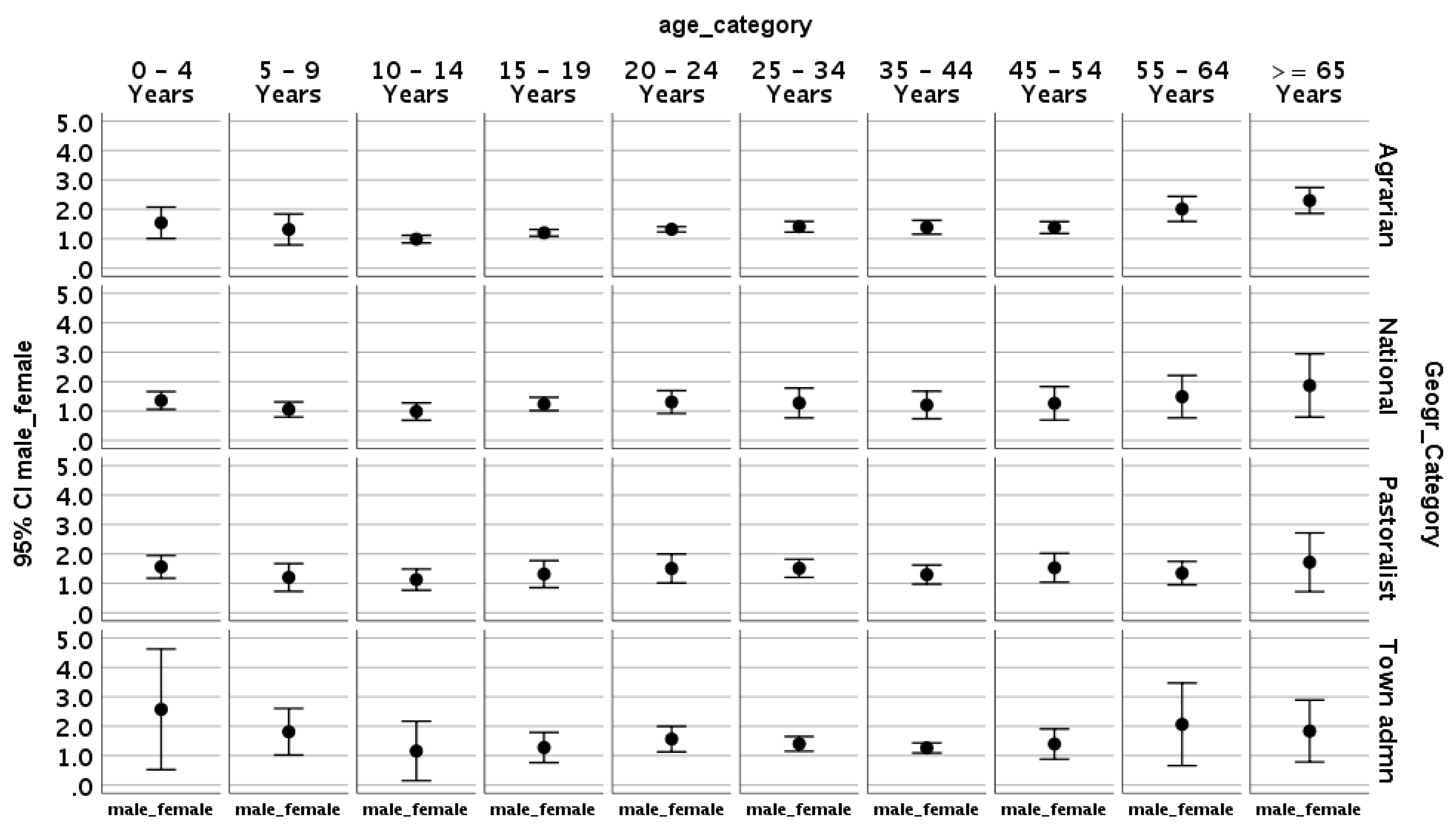

In the agrarian regions (regions where 75% of the population makes its living through farming, i.e., Oromia, Amhara, SNNP and Tigray), M:F is greater than one until 5years of age, drops below one after 5 years of age, drops more drastically after 15 years of age, and then steadily increasing after that until it once again is greater than 0ne over 55 years of age. A similar M:F pattern is noted in the overall national data as well as those from the pastoral regions and cities administrations (

Figure 2).

Both bivariate and multivariable analyses indicated that M:F is associated with age and types of TB. Compared to children <5 years of age, M:F is 26% greater among children aged 5–9 years (AOR 1.26, 95% CI 0.51-2.01) and 53% greater among 10–19 years (AOR 1.53, 95% CI 0.87-2.18). EPTB cases are higher among males in children <10 years of age, while BCTB cases are higher among female in children 10–14 years of age. Also, EPTB is equally or more prevalent among females 34–54 years of age (p-value<0.001) (

Table 2 and

Figure 3) than among males in the same age category.

The 47.8% proportion of BCPTB cases among adolescents is greater than the 44.7% proportion of BCPTB among all age groups (Z-score = 7.5, p value = 0.0001). Also, the proportion of female BCPTB patients among adolescents (47.3%) is greater than the proportion of female BCPTB patients (44%) among all TB patients (Z-score = 5.0; p value <0.0001). This difference is also statistically significant in the Sidama, Oromia, and South Ethiopia regions (Z-score=4.1-7.8, p-value<0.01).

4. Discussion

Ethiopia is on the World Health Organization’s list of 30 high TB burden countries—third in Africa and eighth in the world—and reports a high proportion of TB cases among males [

9]. However, our findings suggest that gender-based TB analysis consider different age categories to allow for a better understanding of age and gender TB epidemiology. Unlike with all forms of TB cases in adults, BCPTB cases are higher among females than males among older children and young adolescents in Ethiopia.

The higher TB burden among adult males, as compared to females in the same age group, could be due to a greater prevalence of TB risk factors among those men, such as silicosis, imprisonment, alcohol use, deprivation, HIV, cancer, and smoking [

11]. A social networking study tried to explain the predominant TB among males, looking at whether distinct mixing patterns by sex and TB disease indicated that TB cases have proportionally more adult male contacts [

17]. The higher TB burden among males might also be due to their economic advantage in the Ethiopian culture, which might give them easier access to TB diagnostic services. The gender differences related to health-seeking behavior, stigma, domestic responsibility, access to economy, lack of patient-centered care, and access to health care could also contribute to the TB burden difference between male and females [

18].

Moreover, the lower TB burden among females in pastoralist regions (Afar, Gambella, Benishangul, and Somalia) might indicate a weak TB program in these areas, where society is male dominated, and lifestyles tend to be nomadic or mobile [

19]. Weak health systems in pastoralist regions could hinder efforts for TB care and control [

19,

20] as passive TB case finding may miss a relatively high number of TB cases among females who cannot easily visit health facilities for TB diagnosis. This could be due to different socioeconomic and cultural factors that might lead to barriers in accessing health care, leaving behind unnotified TB cases in women [

21]. The engagement of girls and women in the health extension program in Ethiopia [

22] could be a good opportunity to empower them to address barriers for accessing to TB diagnosis and treatment service.

Like in our study, finding from Zimbabwe explained that EPTB rate was lower among reproductive age males compared to their females’ counterparts mainly ascribed to high HIV among females [

23]. Studies from Asia also found that while TB of all types was reportedly more prevalent in males, a higher preponderance of EPTB was observed in females [

24]. EPTB can lead to pregnancy complications in women, and it warrants surveillance and advocacy for enhancing the development of new diagnostics and new drugs that consider the special needs of women—specifically those living with HIV and those who are pregnant and lactating [

25].

The persistent age-related trend in immunologic susceptibility among adolescents and young adults [

26] might explain the increasing TB burden among older children, young adolescents, and then adults in our study. That is, puberty is associated with changes in immunity that may contribute to an increased risk of progression to TB disease among these age groups [

26,

27,

28]. Moreover, our study indicated a shift from the less transmissible TB (EPTB and clinical PTB) among <5 years children to highly transmissible forms of TB (bacteriologically confirmed PTB) among older children and adolescents, which could also be attributable to age-related immunologic susceptibility [

3]. Moreover, latent TB infections among children could express themselves as TB disease during adolescence for those affected by malnutrition and HIV [

3,

29] Therefore, TB prevention and control activities could consider the age shift for the different types of TB in Ethiopia.

Specifically, older children and adolescents (10–19 years) are highly affected by infectious TB diseases. This could be partly attributable to the fact that adolescents usually spend their time in school and can easily be exposed for TB transmission [

13,

14]. It could also be due to health challenges associated with pregnancy and childbirth, which may increase the risk of developing TB [

20,

31]. Hence, older children and adolescents could be a focus area for actively detecting TB cases, which ought to be linked to TB infection control in setting adolescents frequent, such as schools, colleges, and universities.

BCPTB cases not only were higher among adolescents; they also were higher among female adolescents. That is, about half of TB cases among adolescents are infectious cases, as are 47% among females’ adolescents in Ethiopia. This might be due to late presentation, higher transmission, and low infection prevention and TB prevention services among these groups. Our study is in line with studies that confirmed adolescent females are more susceptible than males to TB, [

32] TB risk for females increases around the time of menarche, and females have a higher risk of disease progression when compared to age-matched male adolescents [

10,

26,

27]. The study has also shown that an increased BCTB risk for females relative to males appears to peak at mid-adolescence (10–14 years), which is similar to the results of a recent pooled analysis from high income countries.10 These results could be attributable to higher vulnerability to HIV among female adolescents,[

3,

26,

27] but the real reason has yet to be explored in Ethiopia. However, TB screening could be integrated into reproductive health services in schools to deal with the TB epidemic among younger girls. Also, health extension workers (HEWs) could undertake proactive TB screening among female adolescents in the community at religious gatherings and schools.

The study used aggregate routine DHIS2 data; the lack of patient-level data therefore means risk factors for TB could not be exhaustively analyzed. Data from Tigray was not part of this study as DHIS2 was interrupted in the region due to conflict.

5. Conclusions

The higher proportion of infectious TB cases among school-age older children and young adolescents could necessitate high-quality TB services that are accessible and acceptable to adolescents of both genders to facilitate timely diagnosis and support medication adherence and treatment completion for early control of TB transmission. TB among adolescents may be addressed through its integration into reproductive health and youth friendly clinics and pediatric clinics. In addition, HEWs could consider conducting TB screening of female adolescents at religious and school settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zewdu Gahsu.; methodology,Zewdu Gashu, Taye letta, Atakility.; software, Zewdu Gashu and Amtatachew Moges; validation, Atakilty, Taye Letta and Amtatachew.; formal analysis, Zewdu Gashu; investigation, Taye letta and Amtatachew Moges; resources, Taye letta; data curation, Amtatachew; writing—original draft preparation, Zewdu Gashu; writing—review and editing, Zewdu Gashu and Atakilty; visualization, Taye letta and Amtatachew Moges; supervision, Taye letta.; project administration, Taye letta.; funding acquisition, Zewdu Gshu All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Global Health Bureau, Office of Health, Infectious Disease, US Agency for International Development (USAID) financially supported this study through the USAID Eliminate TB Project under the terms of Agreement No. 72066320CA00009. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Review Committee of each Regional Health Bureau (RHB) reviewed and approved the study protocol using the routine DHIS2.

Informed Consent Statement

As the DHIS2 data are aggregate data, they do not capture any personal identifying information.

Data Availability Statement

All data used here are available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the USAID-supported Eliminate TB Project for its comprehensive and uninterrupted support of the TB program in Ethiopia, as well as all staff from the project and federal and regional hospitals who were involved in data collection and compilation. The Global Health Bureau, Office of Health, Infectious Disease, USAID financially supported the study through the USAID Eliminate TB Project under the terms of Agreement No. 72066320CA00009. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

BCPTB Bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB

DHIS2 Health District Health Information System 2

EPTB Extra-pulmonary TB

HIV Human immunodeficiency virus

LQAS Lot quality assurance sampling

TB Tuberculosis

UNHLM United Nations High-Level Meeting

References

- Sahu S, Ditiu L, Zumla A. After the UNGA High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis—what next and how? The Lancet Global Health. 2019 May 1;7(5):e558-60.

- National Roadmap towards ending children and adolescent TB in Ethiopia, 2019. National Roadmap towards ending Childhood and Adolescent TB in Ethiopia (ephi.gov.

- Laycock KM, Enane LA, Steenhoff AP. Tuberculosis in adolescents and young adults: Emerging data on TB transmission and prevention among vulnerable young people. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2021 Aug 5;6(3):148.

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh AC, Patton GC. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. The Lancet. 2012 Apr 28;379(9826):1630-40.

- Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, Arora M, Azzopardi P, Baldwin W, Bonell C, Kakuma R. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet. 2016 Jun 11;387(10036):2423-78.

- Nduba V, Van’t Hoog AH, Mitchell E, Onyango P, Laserson K, Borgdorff M. Prevalence of tuberculosis in adolescents, western Kenya: implications for control programs. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015 Jun 1;35:11-7.

- Enane LA, Lowenthal ED, Arscott-Mills T, Matlhare M, Smallcomb LS, Kgwaadira B, Coffin SE, Steenhoff AP. Loss to follow-up among adolescents with tuberculosis in Gaborone, Botswana. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2016 Oct 1;20(10):1320-5.

- UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2019. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.

- World Health Organization, 2023. Global TB report 2023. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373828/9789240083851-eng.pdf?

- Peer V, Schwartz N, Green MS. Gender differences in tuberculosis incidence rates—A pooled analysis of data from seven high-income countries by age group and time period. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023 Jan 10;10:997025.

- Marçôa R, Ribeiro AI, Zão I, Duarte R. Tuberculosis and gender-Factors influencing the risk of tuberculosis among men and women by age group. Pulmonology. 2018 May-Jun; 24 (3): 199-202. [CrossRef]

- Andrews JR, Morrow C, Walensky RP, Wood R. Integrating social contact and environmental data in evaluating tuberculosis transmission in a South African township. The journal of infectious diseases. 2014 Aug 15;210(4):597-603.

- Moges B, Amare B, Yismaw G, Workineh M, Alemu S, Mekonnen D, Diro E, Tesema B, Kassu A. Prevalence of tuberculosis and treatment outcome among university students in Northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective study. BMC Public Health. 2015 Dec;15(1):1-7.

- Mekonnen A, Petros B. Burden of tuberculosis among students in two Ethiopian universities. Ethiopian medical journal. 2016 Oct;54(4):189.

- CSA, IJ. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. 2016;1(1).

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. HIV related estimates and projections in Ethiopia for the year 2021–2022.

- Miller PB, Zalwango S, Galiwango R, Kakaire R, Sekandi J, Steinbaum L, Drake JM, Whalen CC, Kiwanuka N. Association between tuberculosis in men and social network structure in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2021 Dec; 21:1-9.

- Danarastri S, Perry KE, Hastomo YE, Priyonugroho K. Gender differences in health-seeking behaviour, diagnosis and treatment for TB. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2022 Jun;26(6):568.

- Jode HD, Flintan FE. How to do gender and pastoralism. 2020.

- Atun R, Weil DE, Eang MT, Mwakyusa D. Health-system strengthening and tuberculosis control. The Lancet. 2010 Jun 19;375(9732):2169-78.

- Holmes CB, Hausler H, Nunn P. A review of sex differences in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 1998 Feb 1;2(2):96-104.

- Assefa Y, Gelaw YA, Hill PS, Taye BW, Van Damme W. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Globalization and health. 2019 Dec;15:1-1.

- Humayun M, Chirenda J, Ye W, Mukeredzi I, Mujuru HA, Yang Z. Effect of gender on clinical presentation of tuberculosis (TB) and age-specific risk of TB, and TB-human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. InOpen forum infectious diseases 2022 Oct 1 (Vol. 9, No. 10, p. ofac512). US: Oxford University Press.

- Mehraj J, Khan ZY, Saeed DK, Shakoor S, Hasan R. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis among females in South Asia—gap analysis. International journal of mycobacteriology. 2016 Dec 1;5(4):392-9.

- WHO. Tuberculosis in women. 2018. Tuberculosis in women (who.

- Seddon JA, Chiang SS, Esmail H, Coussens AK. The wonder years: what can primary school children teach us about immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis? Frontiers in immunology. 2018 Dec 13;9:2946.

- Cruz AT, Hwang KM, Birnbaum GD, Starke JR. Adolescents with tuberculosis: a review of 145 cases. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2013 Sep 1;32(9):937-41.

- Chiang SS, Dolynska M, Rybak NR, Cruz AT, Aibana O, Sheremeta Y, Petrenko V, Mamotenko A, Terleieva I, Horsburgh CR, Jenkins HE. Clinical manifestations and epidemiology of adolescent tuberculosis in Ukraine. ERJ Open Research. 2020 Jul 1;6(3).

- Tchakounte Youngui B, Tchounga BK, Graham SM, Bonnet M. Tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pathogens. 2022 Dec 9;11(12):1512.

- Mathad JS, Gupta A. Tuberculosis in pregnant and postpartum women: epidemiology, management, and research gaps. Clinical infectious diseases. 2012 Dec 1;55(11):1532-49.

- Rendell NL, Batjargal N, Jadambaa N, Dobler CC. Risk of tuberculosis during pregnancy in Mongolia, a high incidence setting with low HIV prevalence. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2016 Dec 1;20(12):1615-20.

- Thakur S, Chauhan V, Kumar R, Beri G. Adolescent females are more susceptible than males for tuberculosis. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 2021 Jan 1;13(1):3-6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).