Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Design and Period

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Techniques

2.5. Data Collection Method

2.5.1. Data Collection Tools

2.5.2. Data Quality Control

2.6. Methods of Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Socio Demographic Characteristics of the Households

3.2. Behavioural Characterstics of the Study Participants

3.3. Environmental Factors

3.4. Clinical Characterstics of Children

3.5. Relative Burden of NTDs Among Urban Slum and Rural Children

3.6. Univariate and Multivariable Logistic Regression Models for Risk Factors Associated with NTDs

| Variable | Responses | NTD (n = 1048) | COR (95 % CI) | P value | AOR (95 % CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||||

| Residence | Urban | 77 | 435 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 160 | 376 | 2.4 (1.8, 3.3) | 0.000 | 4.3 (0.28. 63.5) | 0.291 | |

| Highest educational level of the house head | Can’t read and write | 144 | 404 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Read and write | 33 | 177 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.79) | 0.0020.8 | 0.55 (0.15 2.0) | 0.363 | |

| Primary school | 26 | 77 | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) | 0.826 | 0.17 (0.02, 1.4) | 0.104 | |

| Secondary school | 14 | 39 | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 0.983 | 0.34 (0.027, 4.2) | 0.400 | |

| College and above | 20 | 114 | 0.5 (0.29, 0 .8) | 0.007 | 0.58 (0.05 7.1) | 0.669 | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 101 | 149 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Merchant | 26 | 157 | 0.2 (0.15, 0.4) | 0.000 | 0.88 (0.06, 12.6) | 0.923 | |

| Government employed | 28 | 175 | 0.24 (0.15, 0 .4) | 0.000 | 12.5 (1.17, 132.4) | 0.036 | |

| Housewife | 45 | 230 | 0.29 (0.19, 0.4) | 0.000 | 1.41 (0.18, 7.1) | 0.884 | |

| Others | 37 | 100 | 0.5 (0.35, 0 .8) | 0.009 | 0.9 (0.07, 12.3) | 0.945 | |

| Monthly income | Low income | 175 | 402 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Good income | 62 | 409 | 0.35 (0.25, 0.5) | 0.000 | 0.13 (.03, 0.57) | 0.007 | |

| Household size | One to five | 111 | 418 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Greater than five | 126 | 393 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 0.203 | 2.66 (0.5, 13.9) | 0.245 | |

| Enrergy source for cooking | Wood/Mud | 210 | 590 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Electiricity | 27 | 221 | 0.34(0.22, 0.5) | 0.000 | 0.89 (0.02, 36.3) | 0.949 | |

| Number of children | One to three | 133 | 492 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Greater than three | 104 | 319 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) | 0.210 | 1.4 (0.26, 7.7) | 0.681 | |

| Age of the child | 0 to 5 years | 94 | 289 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6 to 10 years | 102 | 330 | 1.01 (0.67, 1.5) | 0.940 | 1.002 (0.24, 4.1) | 0.997 | |

| 11 to 18 years | 41 | 192 | 0.68 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.159 | 1.04 (0.17, 6.4) | 0.968 | |

| Educational status of the child | Under school | 58 | 147 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary or secondary school | 131 | 490 | 0.68 (0.47, 0.97) | 0.034 | 1.3 (0.26, 6.3) | 0.758 | |

| Not attending school | 48 | 174 | 0.7 (0.45, 1.0) | 0.112 | 0.83 (0.17, 4.1) | 0.819 | |

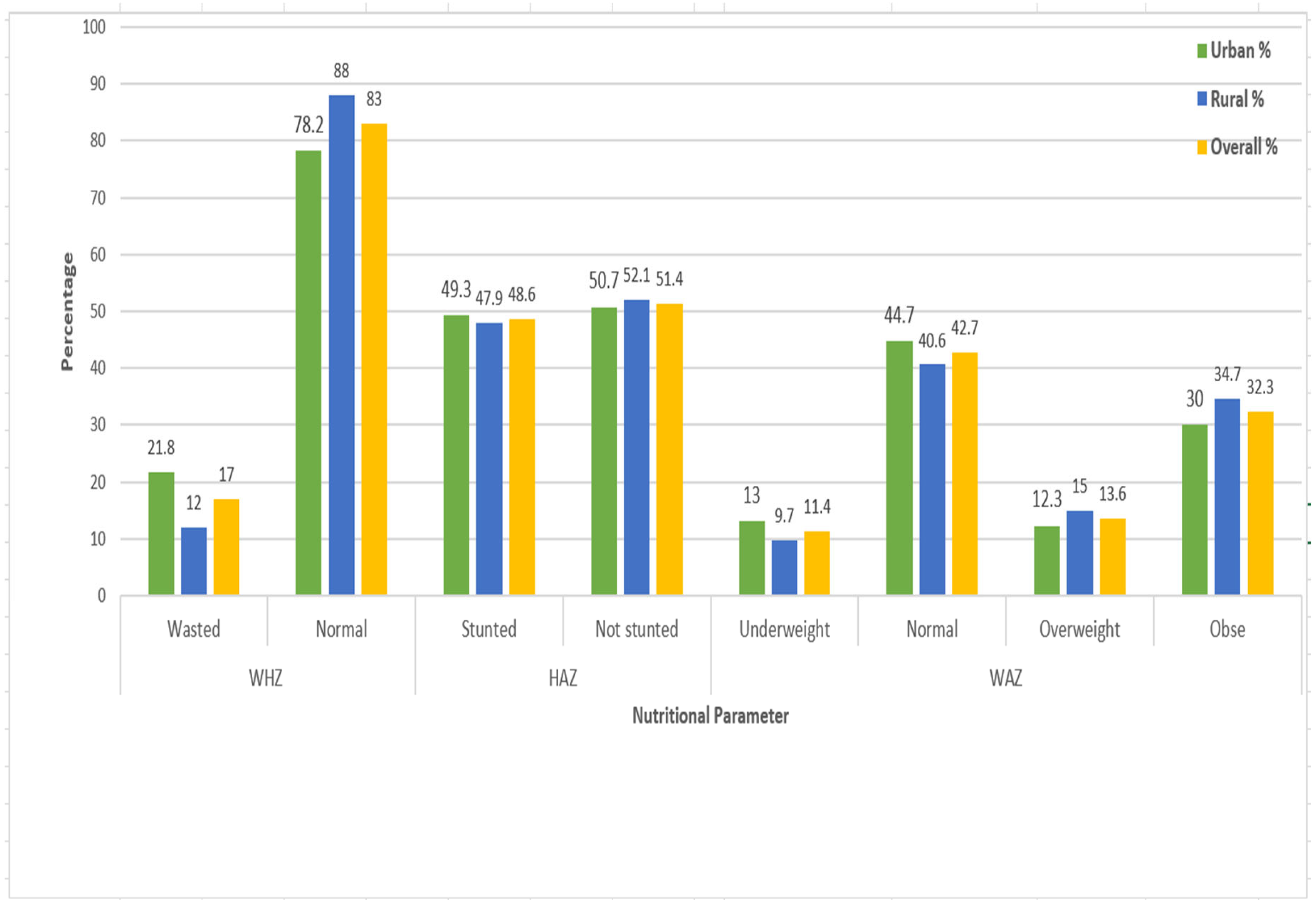

| WHZ | Wasted | 26 | 110 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Normal | 157 | 509 | 0.77 (0.4, 1.4) | 0.416 | 1.6 (0.3, 9.1) | 0.567 | |

| HAZ | Stunted | 108 | 392 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Not stunted | 124 | 405 | 0.87 (0.6 1.3) | 0.472 | 0.46 (0.15, 1.4) | 0.182 | |

| WAZ | Underweight | 30 | 87 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Normal | 98 | 341 | 0.73 (0.38, 1.4) | 0.352 | 0.74 (0.14 3.9) | 0.722 | |

| Overweight | 35 | 105 | 0.86 (0.4. 1.8) | 0.703 | 0.6 (0.08, 4.3) | 0.616 | |

| Obse | 69 | 264 | 0.71 (0.37 1.4) | 0.316 | 0.5 (0.07, 3.7) | 0.520 | |

| Sharing clothes | Yes | 173 | 505 | 1.6 (1.19, 2.2) | 0.003 | 0.62 (0.16, 2.3) | 0.479 |

| No | 64 | 306 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Wearing shoe | Yes | 172 | 544 | 1.3 (0.9, 1.8) | 0.110 | 1.8 (0.55, 5.8) | 0.337 |

| No | 65 | 267 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Child playing with soil | Yes | 178 | 435 | 2.6 (1.9, 3.6) | 0.000 | 5.8 (1.52, 22.0) | 0.010 |

| No | 59 | 376 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Raw vegitable eating habit | Yes | 94 | 433 | 0.57 (0.4, 0.77) | 0.000 | 0.42 (0.13, 1.3) | 0.140 |

| No | 143 | 378 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Child hand washing critical times | One critical time | 95 | 263 | 1 | 0.059 | 1 | |

| Two critical times | 87 | 329 | 1.04 (0.7, 1.5) | 0.831 | 0.35 (0.1, 1.2) | 0.097 | |

| Three or more critical times | 55 | 219 | 2.04 (1.17, 3.6) | 0.012 | 11.2 (1.7, 74.9) | 0.013 | |

| Frequency of washing child face per day | Once | 94 | 304 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Twowice | 85 | 261 | 1.05 (0.7, 1.5 | 0.763 | 1.7 (0.6, 4.86) | 0.285 | |

| Three times | 58 | 246 | 0.76 (0.5, 1.1) | 0.149 | 0.47 (0.09, 2.4) | 0.369 | |

| Hygiene condition of child face | Clean | 94 | 511 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Unclean | 143 | 300 | 2.6 (1.9, 3.5) | 0.000 | 0.74 (0.2, 2.8) | 0.663 | |

| Presence of flies in the child faces | Yes | 162 | 301 | 3.7 (2.7, 4.98) | 0.000 | 20.3 (4.7, 88.6) | 0.000 |

| No | 75 | 510 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Presence of animal dung in the compound | Yes | 146 | 348 | 2.1 (1.6, 2.9) | 0.000 | 1.9 (0.3, 11.2) | 0.488 |

| No | 91 | 463 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Type of drinking water source | Improved | 209 | 679 | 0.42 (0.26, .66) | 0.000 | 0.11 (0.02, 0.73) | 0.022 |

| Unimproved | 28 | 132 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Are all the water containers clean? | Yes | 138 | 437 | 1.2 (0.89, 1.6) | 0.237 | 0.63 (0.2, 1.9) | 0.414 |

| No | 99 | 374 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Vulume of water used per capita per day | < 20 liter | 202 | 736 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥ 20 liter per day | 35 | 75 | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 0.016 | 2.04 (0.5, 7.8) | 0.296 | |

| Do you treat your drinking water | Yes | 20 | 122 | 0.52 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.010 | 0.42 (0.03, 5.2) | 0.506 |

| No | 217 | 689 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Water shortage in the previous one month | Yes | 131 | 567 | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.000 | 0.59 (0.17, 2.0) | 0.402 |

| No | 106 | 244 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Satisfaction with the current water service | Satisfied | 105 | 213 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Not satisfied | 132 | 598 | 0.45 (0.3, 0.6) | 0.000 | 4.3 (0.84, 22.4) | 0.080 | |

| Presence of feces in the floor of the toilet | Yes | 92 | 195 | 2 (1.4, 2.7) | 0.000 | 0.56 (0.19, 1.6) | 0.293 |

| No | 100 | 417 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Presence of flies in the toilet | Yes | 165 | 416 | 2.9 (1.8, 4.4) | 0.000 | 1.5 (0.19, 12.0) | 0.694 |

| No | 27 | 196 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Presence of faces in the ground of the compound | Yes | 106 | 472 | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 131 | 339 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) | 0.000 | 1.9 (0.59, 6.3) | 0.278 | |

| Do the family use animal dug as fertilizer? | Yes | 89 | 269 | 0.3 (0.22, 0.5) | 0.000 | 0.33 (0.1, 1.1) | 0.077 |

| No | 49 | 51 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Presence of waste water discharge in the compound | Yes | 162 | 411 | 2.1 (1.5, 2.8) | 0.000 | 1.7 (0.52, 5.5) | 0.385 |

| No | 75 | 399 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Often use street vender food | Yes | 90 | 258 | 1.3 (0.97, 1.77) | 0.077 | 1.5 (0.5, 4.7) | 0.454 |

| No | 147 | 553 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Presence of flies in the kitchen | Yes | 192 | 551 | 2 (1.4. 2.9) | 0.000 | 0.44 (0.09, 2.3) | 0.330 |

| No | 45 | 260 | 1 | ||||

| Are you a regular health insurance user? | Yes | 193 | 583 | 1.7 (1.19, 2.4) | 0.003 | 1.7 (0.27, 10.3) | 0.585 |

| No | 44 | 228 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Does the health care cost influnces the choice of health institution? | Yes | 116 | 451 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Some what | 99 | 282 | 1.4 (1.0, 1.8) | 0.047 | 1.8 (0.56, 5.5) | 0.333 | |

| No | 22 | 78 | 1.1 (0.6, 1.8) | 0.726 | 1.7 (0.28, 10.2) | 0.556 | |

| Awerness about NTDs | Yes | 45 | 102 | 1.6 (1.1, 2.4) | 0.013 | 1.6 (0.5, 5.1) | 0.395 |

| No | 192 | 709 | 1 | ||||

| Did the child have any NTD within the previous two months | Yes | 45 | 102 | 0.7 (0.45, 1.2) | 0.241 | 2.8 (0.85, 9.1) | 0.091 |

| No | 192 | 709 | 1 | 1 | |||

4. Discussions

5. Conlusions

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| CDLQI | Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease-19 |

| HCFs | HealthCare Facilities |

| HHCs | Household Contacts |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| NTDs | Neglected Tropical Diseases |

| SAFE | Surgery, Antibiotics, Facial Cleanliness, and Environmental Hygiene |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| sNTD | Skin Related Neglected Tropical Diseases |

| STHs | Soil-Transmitted Helminthiases |

| WASH | Water, Sanitation and Hygiene |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- S. Zaman et al., "Severely stigmatised skin neglected tropical diseases: a protocol for social science engagement," vol. 114, no. 12, pp. 1013-1020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Koffi et al., "Integrated approach in the control and management of skin neglected tropical diseases in three health districts of Côte d’Ivoire," vol. 20, pp. 1-9, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. J. P. N. T. D. PJ, "Neglected tropical diseases in sub-saharan Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease burden," vol. 3, p. e412, 2009.

- K. J. E. Worku, "Neglected tropical diseases program in ethiopia, progress and challenges," vol. 55, no. 4, 2017.

- A. T. van ‘t Noordende, M. W. Aycheh, and A. J. P. n. t. d. Schippers, "The impact of leprosy, podoconiosis and lymphatic filariasis on family quality of life: A qualitative study in Northwest Ethiopia," vol. 14, no. 3, p. e0008173, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. R. J. T. m. Yotsu and i. disease, "Integrated management of skin NTDs—lessons learned from existing practice and field research," vol. 3, no. 4, p. 120, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Aborode et al., "Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) and COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: Special focus on control strategies," vol. 25, no. 14, pp. 2387-2390, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Hotez, A. Fenwick, L. Savioli, and D. H. J. T. L. Molyneux, "Rescuing the bottom billion through control of neglected tropical diseases," vol. 373, no. 9674, pp. 1570-1575, 2009. [CrossRef]

- D. G. J. P. N. T. D. Addiss, "Global elimination of lymphatic filariasis: addressing the public health problem," vol. 4, no. 6, p. e741, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Taylor, A. Hoerauf, and M. J. T. L. Bockarie, "Lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis," vol. 376, no. 9747, pp. 1175-1185, 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Liese, M. Rosenberg, and A. J. T. L. Schratz, "Programmes, partnerships, and governance for elimination and control of neglected tropical diseases," vol. 375, no. 9708, pp. 67-76, 2010. [CrossRef]

- W.-t. J. F. W. H. O. Helminthiases, "Eliminating soil-transmitted helminthiases as a public health problem in children: progress report 2001–2010 and strategic plan 2011–2020," vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 19-29, 2012.

- WHO, "Overview and Burden of Trachoma. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.," Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trachoma. Accessed December 12, 2023, 2020.

- M. W. Kassaw, A. M. Abebe, K. D. Tegegne, M. A. Getu, and W. T. Bihonegn, "Prevalence and Risk Factors of Active Trachoma among Rural Preschool Children in Wadla District, Northern Ethiopia: A Community Based Cross-Sectional Study," 2019.

- WHO, "GET17 Report Final. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.," Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/382302091/GET17Report-Final. Accessed December 12, 2023. , 2013.

- K. Ayelgn, T. Guadu, and A. J. I. J. o. P. Getachew, "Low prevalence of active trachoma and associated factors among children aged 1–9 years in rural communities of Metema District, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study," vol. 47, no. 1, p. 114, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Alambo, E. A. Lake, S. Bitew Workie, and A. Y. J. I. P. o. I. D. Wassie, "Prevalence of active trachoma and associated factors in Areka Town, south Ethiopia, 2018," vol. 2020, no. 1, p. 8635191, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Sara, Y. Haji, A. J. D. r. Gebretsadik, and practice, "Scabies outbreak investigation and risk factors in East Badewacho District, Southern Ethiopia: unmatched case control study," vol. 2018, no. 1, p. 7276938, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Misganaw, S. G. Nigatu, G. N. Gebrie, and A. A. J. P. o. Kibret, "Prevalence and determinants of scabies among school-age children in Central Armachiho district, Northwest, Ethiopia," vol. 17, no. 6, p. e0269918, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. L. R. H. W. J. T. L. R. H. W. P. Pacific, "To end the neglect of neglected tropical diseases," vol. 18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Ventura-Garcia et al., "Socio-cultural aspects of Chagas disease: a systematic review of qualitative research," vol. 7, no. 9, p. e2410, 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. Ganasegeran, S. A. J. N. T. D. Abdulrahman, and P. i. D. Discovery, "Epidemiology of Neglected Tropical Diseases," pp. 1-36, 2021.

- C. Eiser and R. J. H. t. a. Morse, "Quality-of-life measures in chronic diseases of childhood," vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1-157, 2001. [CrossRef]

- P. Djossou et al., "Integrated approach in the control of neglected tropical diseases with cutaneous manifestations in four municipalities in Benin: A cross-sectional study," vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 184-191, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Deribew et al., "Mortality and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for common neglected tropical diseases in Ethiopia, 1990-2015: evidence from the global burden of disease study 2015," vol. 55, no. Suppl 1, p. 3, 2017.

- T. Eyayu et al., "Prevalence, intensity of infection and associated risk factors of soil-transmitted helminth infections among school children at Tachgayint woreda, Northcentral Ethiopia," vol. 17, no. 4, p. e0266333, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Zeynudin, T. Degefa, S. Suleman, A. Abamecha, Z. Hajikelil, and A. J. J. o. T. M. Wieser, "Prevalence and Determinants of Geohelminthiasis among School-Age Children in Jimma City, Ethiopia," vol. 2023, no. 1, p. 8811795, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Thylefors, C. R. Dawson, B. R. Jones, S. K. West, and H. R. J. B. o. t. W. H. O. Taylor, "A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications," vol. 65, no. 4, p. 477, 1987.

- World Health Organization, WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. World Health Organization, 2006.

- L. Keller et al., "Performance of the Kato-Katz method and real time polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of soil-transmitted helminthiasis in the framework of a randomised controlled trial: treatment efficacy and day-to-day variation," vol. 13, pp. 1-12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. AnthroPlus, "for Personal Computers," 2009.

- D. A. Bitew, D. B. Asmamaw, T. B. Belachew, and W. D. J. H. Negash, "Magnitude and determinants of women's participation in household decision making among married women in Ethiopia, 2022: Based on Ethiopian demographic and health survey data," vol. 9, no. 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Thumbi et al., "Linking human health and livestock health: a “one-health” platform for integrated analysis of human health, livestock health, and economic welfare in livestock dependent communities," vol. 10, no. 3, p. e0120761, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. o. H. Ethiopia, "The third national neglected tropical diseases strategic plan 2021-2025," ed: Ministry of Health Ethiopia Addis Ababa, 2021.

- D. J. González Quiroz et al., "Prevalence of soil transmitted helminths in school-aged children, Colombia, 2012-2013," vol. 14, no. 7, p. e0007613, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. W. Kihoro et al., "Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminthiasis among school-aged children in pastoralist communities of Kenya: A cross-sectional study," vol. 19, no. 5, p. e0304266, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Shimelash et al., "Prevalence of active trachoma and associated factors among school age children in Debre Tabor Town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019: a community based cross-sectional study," vol. 48, no. 1, p. 61, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. D. King et al., "Trachoma among children in community surveys from four African countries and implications of using school surveys for evaluating prevalence," vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 280-287, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Genet et al., "Prevalence of active trachoma and its associated factors among 1–9 years of age children from model and non-model kebeles in Dangila district, northwest Ethiopia," vol. 17, no. 6, p. e0268441, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Getachew et al., "High prevalence of active trachoma and associated factors among school-aged children in Southwest Ethiopia," vol. 17, no. 12, p. e0011846, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Asmare et al., "Prevalence and associated factors of active trachoma among 1–9 years of age children in Andabet district, northwest Ethiopia, 2023: A multi-level mixed-effect analysis," vol. 17, no. 8, p. e0011573, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Tuke, E. Etu, E. J. T. A. J. o. T. M. Shalemo, and Hygiene, "Active trachoma prevalence and related variables among children in a pastoralist community in southern Ethiopia in 2021: a community-based cross-sectional study," vol. 108, no. 2, p. 252, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Anteneh, W. Y. J. T. d. Getu, travel medicine, and vaccines, "Prevalence of active trachoma and associated risk factors among children in Gazegibela district of Wagehemra Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study," vol. 2, pp. 1-7, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Mohamed, F. Weldegebreal, J. Mohammed, A. J. E. A. J. o. H. Gemechu, and B. Sciences, "Trachoma and Associated Factors among School Age Children 4-9 Years in Dire Dawa Administration, Eastern Ethiopia," vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 45-54, 2019.

- N. Assefa, A. A. Roba, T. Abdosh, J. Kemal, and E. J. O. R. A. I. J. Demissie, "Prevalence and factors associated with trachoma among primary school children in Harari region, eastern Ethiopia," vol. 7, no. 3, p. OR. 37212, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Traoré et al., "Prevalence of trachoma in the Kayes region of Mali eight years after stopping mass drug administration," vol. 12, no. 2, p. e0006289, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Wu, Z. L. Hu, D. He, W. R. Xu, and Y. J. B. o. Li, "Trachoma in Yunnan province of southwestern China: findings from trachoma rapid assessment," vol. 18, pp. 1-6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Favacho et al., "Prevalence of trachoma in school children in the Marajó Archipelago, Brazilian Amazon, and the impact of the introduction of educational and preventive measures on the disease over eight years," vol. 12, no. 2, p. e0006282, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Khokhar, S. Sabar, and N. J. J. T. J. o. t. P. M. A. Lateef, "Active trachoma among children of District Dera Ghazi Khan, Punjab, Pakistan: A cross sectional study," vol. 68, no. 9, pp. 1300-1303, 2018.

- A. Hansmann et al., "Low prevalence of scabies and impetigo in Dakar/Senegal: a cluster-randomised, cross-sectional survey," vol. 4, no. 2, p. e0002942, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Schneider, J. Wu, L. Tizek, S. Ziehfreund, A. J. J. o. t. E. A. o. D. Zink, and Venereology, "Prevalence of scabies worldwide—An updated systematic literature review in 2022," vol. 37, no. 9, pp. 1749-1757, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Haile, T. Sisay, and T. J. P. A. M. J. Jemere, "Scabies and its associated factors among under 15 years children in Wadila district, Northern Ethiopia, 2019," vol. 37, no. 1, 2020.

- G. Ararsa, E. Merdassa, T. Shibiru, and W. J. P. o. Etafa, "Prevalence of scabies and associated factors among children aged 5–14 years in Meta Robi District, Ethiopia," vol. 18, no. 1, p. e0277912, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Andrews, J. McCarthy, J. R. Carapetis, and B. J. J. P. C. Currie, "Skin disorders, including pyoderma, scabies, and tinea infections," vol. 56, no. 6, pp. 1421-1440, 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. Hajissa, M. A. Islam, A. M. Sanyang, and Z. J. P. n. t. d. Mohamed, "Prevalence of intestinal protozoan parasites among school children in africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis," vol. 16, no. 2, p. e0009971, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Dagne and A. J. J. o. P. R. Alelign, "Prevalence of intestinal protozoan parasites and associated risk factors among school children in merhabete District, Central Ethiopia," vol. 2021, no. 1, p. 9916456, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Tegen, D. J. C. J. o. I. D. Damtie, and M. Microbiology, "Prevalence and risk factors associated with intestinal parasitic infection among primary school children in Dera district, northwest Ethiopia," vol. 2021, no. 1, p. 5517564, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Chilot, D. G. Belay, K. Shitu, B. Mulat, A. Z. Alem, and D. M. J. B. o. Geberu, "Prevalence and associated factors of common childhood illnesses in sub-Saharan Africa from 2010 to 2020: a cross-sectional study," vol. 12, no. 11, p. e065257, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Simionato de Assis et al., "Social determinants, their relationship with leprosy risk and temporal trends in a tri-border region in Latin America," vol. 12, no. 4, p. e0006407, 2018.

- T. A. Houweling et al., "Socioeconomic inequalities in neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review," vol. 10, no. 5, p. e0004546, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Klingele, Hararghe Farmers on the Cross-roads Between Subsistence & Cash Economy. United Nations Development Programme, Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia, 1998.

- B. A. Rahimi et al., "Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and associated risk factors among primary school children in Kandahar, Afghanistan: A cross-sectional analytical study," vol. 17, no. 9, p. e0011614, 2023.

- I. B. Y. Brahmantya, H. H. P. Iqra, I. G. N. B. R. Mulya, I. A. W. Anjani, I. M. Sudarmaja, and C. J. O. A. M. J. o. M. S. Ryalino, "Risk factors and prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infections," vol. 8, no. A, pp. 521-524, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Samuel, A. Demsew, Y. Alem, and Y. J. B. P. H. Hailesilassie, "Soil transmitted Helminthiasis and associated risk factors among elementary school children in ambo town, western Ethiopia," vol. 17, pp. 1-7, 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Waite, G. Woods, Y. Velleman, and M. C. J. I. h. Freeman, "Collaborating to develop joint water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and neglected tropical disease (NTD) sector monitoring: an expert consultation," vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 215-225, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. J. G. W. H. O. Water, "sanitation and hygiene for accelerating and sustaining pro-gress on neglected tropical diseases," pp. 1-6, 2015.

- Z. Salou Bachirou et al., "WASH and NTDs: Outcomes and lessons learned from the implementation of a formative research study in NTD skin co-endemic communities in Benin," vol. 10, p. 1022314, 2023. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Responses categories | Urban | Rural | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | ||

| Caregivers’ age category | 15 to 29 years | 200 | 39 | 193 | 36 | 393 | 38 |

| 30 to 44 years | 256 | 50 | 313 | 58 | 569 | 54 | |

| 45 and above years | 56 | 11 | 30 | 6 | 86 | 8 | |

| Caregivers’ education status | No formal education | 172 | 33 | 376 | 70 | 548 | 52 |

| Read and write | 155 | 30 | 55 | 10 | 210 | 20 | |

| Primary school | 63 | 12 | 40 | 7.5 | 103 | 10 | |

| Secondary school | 14 | 3 | 39 | 7.5 | 53 | 5 | |

| College and above | 108 | 21 | 26 | 5 | 134 | 13 | |

| Caregivers’ marital status | Single | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Married | 455 | 89 | 509 | 95 | 964 | 92 | |

| Separated/divorced | 57 | 11 | 26 | 4.8 | 83 | 7.9 | |

| Occupation of caregivers | Farmer | 6 | 1 | 244 | 45 | 230 | 22 |

| Merchant | 160 | 31 | 23 | 4 | 183 | 34 | |

| Employed | 167 | 33 | 36 | 7 | 203 | 194 | |

| Housewife | 69 | 13 | 206 | 38 | 275 | 26 | |

| Others | 110 | 21 | 27 | 5 | 137 | 13 | |

| Monthly income | Low income | 148 | 29 | 429 | 80 | 577 | 55 |

| Good income | 364 | 71 | 107 | 20 | 471 | 45 | |

| Type of energy source for cooking | Wood/animal mud | 268 | 52 | 532 | 99 | 800 | 76 |

| Electricity | 244 | 48 | 4 | 1 | 248 | 24 | |

| Family size | 0 to 5 years | 324 | 63 | 205 | 38 | 529 | 50.5 |

| ➢ 5 years | 188 | 37 | 331 | 62 | 519 | 49.5 | |

| Number of children | 1 to 3 | 372 | 73 | 253 | 47 | 625 | 60 |

| ≥ 4 | 140 | 27 | 283 | 53 | 423 | 40 | |

| Child birth order | 1st | 172 | 33 | 152 | 28 | 324 | 309 |

| 2nd | 164 | 32 | 129 | 24 | 293 | 55 | |

| 3rd | 115 | 22 | 115 | 21 | 230 | 22 | |

| 4th and above | 61 | 12 | 140 | 26 | 201 | 19 | |

| Child sex | Male | 273 | 53 | 252 | 47 | 525 | 50.1 |

| Female | 239 | 47 | 284 | 53 | 523 | 49.9 | |

| Child age catagories | 0 to 5 years | 178 | 35 | 205 | 4 | 383 | 36 |

| 6 to 10 years | 207 | 40 | 225 | 42 | 432 | 40 | |

| 11 to 15 years | 102 | 20 | 97 | 18 | 199 | 19 | |

| 16 to 18 years | 25 | 5 | 9 | 1.5 | 34 | 3 | |

| Child education | Under School | 91 | 18 | 114 | 21 | 205 | 19 |

| Primary School | 293 | 57 | 301 | 56 | 594 | 57 | |

| Secondary School | 24 | 5 | 3 | 0.5 | 27 | 2 | |

| Not Attending School | 104 | 20 | 118 | 22 | 222 | 21 | |

| Variable | Responses catagories | Urban | Rural | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | ||

| Sharing clothes | Yes | 270 | 52.7 | 408 | 76 | 678 | 64.7 |

| No | 242 | 47.3 | 128 | 24 | 370 | 35.3 | |

| Waring shoes | Yes | 381 | 74.4 | 335 | 62 | 716 | 68.3 |

| No | 131 | 25.6 | 201 | 38 | 332 | 31.7 | |

| Child nail trimmed | Yes | 308 | 60 | 244 | 45 | 552 | 52.7 |

| No | 204 | 40 | 292 | 55 | 496 | 47.3 | |

| Child playing habit with soil | Yes | 217 | 42.4 | 396 | 74 | 613 | 58.5 |

| No | 295 | 56.6 | 140 | 26 | 435 | 41.5 | |

| Raw vegitable eating habit | Yes | 319 | 62 | 208 | 39 | 527 | 50.3 |

| No | 193 | 38 | 328 | 61 | 521 | 49.7 | |

| Number of critical times of child hand washing | One critical time | 79 | 15 | 279 | 52 | 358 | 34 |

| Two critical times | 223 | 43 | 193 | 36 | 416 | 40 | |

| Three or more critical times | 210 | 42 | 64 | 12 | 274 | 26 | |

| Frequency of washing child face per day | Once | 79 | 15 | 319 | 59 | 398 | 38 |

| Twowice | 202 | 39 | 144 | 27 | 346 | 33 | |

| Three or more times | 231 | 45 | 73 | 14 | 304 | 29 | |

| How do the child wash his/her face | Water only | 238 | 46.5 | 416 | 78 | 654 | 62 |

| Water and soap | 274 | 53.5 | 120 | 22 | 394 | 38 | |

| Are there flies on child face? | Yes | 126 | 24.6 | 337 | 63 | 463 | 44 |

| No | 386 | 75.4 | 199 | 37 | 585 | 56 | |

| Where does the child deficate last time? | Potty/diaper | 101 | 19.6 | 10 | 1.9 | 111 | 10.6 |

| Toilet | 18 | 3.4 | 7 | 1.3 | 25 | 24 | |

| Open ground | 123 | 24.3 | 365 | 68.1 | 488 | 45.6 | |

| Others | 270 | 52.7 | 154 | 28.7 | 424 | 40.4 | |

| When does the water container cleaned? | Today or yesterday | 37 | 7 | 43 | 9 | 80 | 7.6 |

| Three to seven days before | 269 | 52 | 196 | 36 | 465 | 44.4 | |

| Before a week | 193 | 38 | 168 | 31 | 361 | 34 | |

| Don’t remember | 13 | 3 | 129 | 28 | 142 | 13.5 | |

| Are all water containers clean? | Yes | 344 | 67 | 231 | 43 | 575 | 55 |

| No | 168 | 33 | 305 | 57 | 473 | 45 | |

| Where does the child take bath usually? | Bathroom | 18 | 3.5 | 4 | 0.7 | 22 | 2 |

| Toilet | 177 | 34.5 | 22 | 4 | 199 | 19 | |

| Inside home | 265 | 52 | 293 | 55 | 558 | 53 | |

| Others | 52 | 10 | 217 | 40 | 269 | 26 | |

| How do you wash kitchen utinsils? | With cold water only | 144 | 28 | 405 | 75 | 549 | 52 |

| Hot water only | 16 | 3 | 9 | 1.7 | 25 | 2.1 | |

| Cold water with soap | 343 | 66.8 | 121 | 22.6 | 464 | 44 | |

| Hot water with soap | 9 | 0,2 | 1 | 0.2 | 10 | 0.9 | |

| Do you often buy food from street venders for your children? | Yes | 205 | 40 | 143 | 26.7 | 348 | 33 |

| No | 307 | 60 | 393 | 73.3 | 700 | 67 | |

| Do you use animal face fertilizer? | Yes | 13 | 30 | 345 | 83 | 358 | 78 |

| No | 30 | 70 | 70 | 17 | 100 | 22 | |

| Variable | Responses catagories | Urban | Rural | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | ||

| Type of drinking water source | Improved | 502 | 98 | 386 | 72 | 888 | 84.7 |

| Unimproved | 10 | 2 | 150 | 28 | 160 | 15.3 | |

| Type of water container used | Noarrow mouthed | 353 | 69 | 502 | 94 | 855 | 81.6 |

| Wide mouthed | 20 | 3.9 | 11 | 2 | 31 | 3 | |

| Both type | 139 | 27.1 | 23 | 4 | 162 | 15.4 | |

| Does all water containers covered? | Yes | 261 | 51 | 176 | 32.8 | 437 | 41.7 |

| No | 239 | 46.7 | 336 | 62.7 | 575 | 54.9 | |

| Some only | 12 | 2.3 | 24 | 4.5 | 36 | 3.4 | |

| Methods of withdrawing water | Pouring | 342 | 66.8 | 464 | 86 | 806 | 77 |

| Dipping with cup | 9 | 1.7 | 30 | 5.6 | 39 | 3.7 | |

| Both pouring and dipping | 138 | 2.7 | 39 | 7.3 | 177 | 16.9 | |

| Using spigot/tap | 23 | 4.5 | 3 | 0.6 | 26 | 2.5 | |

| Amount of water used per day per capita | < 20 litter | 464 | 90.6 | 474 | 88 | 938 | 89 |

| > 20 litters | 48 | 9.4 | 62 | 11 | 110 | 10.5 | |

| Do you treat your drinking water? | Yes | 128 | 25 | 14 | 2.6 | 142 | 13.5 |

| No | 384 | 75 | 522 | 97.4 | 906 | 76.5 | |

| Did you experience any water shortage within the previous one months? | Yes | 420 | 82 | 278 | 51.9 | 698 | 66.6 |

| No | 92 | 18 | 258 | 48.1 | 350 | 33.4 | |

| Have you satisfied with the existing water service | Yes | 43 | 8.4 | 275 | 51 | 318 | 30.3 |

| No | 469 | 91.6 | 261 | 49 | 730 | 69.7 | |

| Availability of latrine? | Yes | 416 | 81 | 388 | 72 | 804 | 76.7 |

| No | 96 | 19 | 148 | 28 | 244 | 23.3 | |

| Type of latrine in use? | Improved latrine | 205 | 49 | 54 | 38 | 259 | 24.7 |

| Unimproved latrine | 211 | 51 | 334 | 62 | 545 | 75.3 | |

| Latrine distance from home | < 50 meters | 416 | 100 | 375 | 96.6 | 791 | 98.4 |

| >50 meters | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3.4 | 13 | 1.6 | |

| Latrine distance from the sirect water source | < 250 meter | 414 | 99.5 | 193 | 49.7 | 607 | 75.5 |

| > 250 meters | 2 | 0.5 | 195 | 50.3 | 197 | 24.5 | |

| Faces in the latrine ground | Yes | 89 | 21.4 | 198 | 63 | 287 | 35.7 |

| No | 327 | 78.6 | 190 | 37 | 517 | 64.3 | |

| Flies in the latrine | Yes | 224 | 53.8 | 357 | 92 | 581 | 72 |

| No | 192 | 46.2 | 31 | 8 | 223 | 28 | |

| Are there feces on the ground of the compound? | Yes | 333 | 65 | 245 | 25 | 578 | 55 |

| No | 179 | 35 | 291 | 75 | 470 | 45 | |

| Presence of animal dung in the compound | Yes | 79 | 16 | 415 | 77 | 494 | 47 |

| No | 433 | 84 | 121 | 23 | 554 | 53 | |

| Presence of liquid west in the compound | Yes | 206 | 40 | 367 | 68 | 573 | 54.7 |

| No | 306 | 60 | 168 | 32 | 474 | 45.3 | |

| Availability of hand washing set up | Yes | 2 | 0.4 | 8 | 1.5 | 32 | 3 |

| No | 488 | 99.6 | 528 | 98.5 | 1,016 | 97 | |

| Presence of livestock | Yes | 43 | 8.4 | 415 | 77 | 458 | 43.7 |

| No | 469 | 91.6 | 121 | 23 | 590 | 55.3 | |

| Variable | Responses catagories | Urban | Rural | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | ||

| Presence of any trauma | Yes | 12 | 97.6 | 26 | 4.8 | 38 | 4 |

| No | 500 | 2.4 | 510 | 95.2 | 1,010 | 96 | |

| History of NTDs | Yes | 57 | 11 | 100 | 18.7 | 157 | 15 |

| No | 455 | 89 | 436 | 81.3 | 891 | 85 | |

| Dewarming/anti parasitic drug within the previous two weeks | Yes | 480 | 95 | 501 | 93 | 981 | 93.6 |

| No | 32 | 5 | 35 | 7 | 67 | 6.4 | |

| Does any family member have beed diagnosed any NTD? | Yes | 77 | 15 | 185 | 34 | 262 | 25 |

| No | 435 | 85 | 351 | 66 | 786 | 75 | |

| Are you regular user of health insurance? | Yes | 283 | 55 | 493 | 92 | 776 | 74 |

| No | 229 | 45 | 43 | 8 | 272 | 26 | |

| Does the cost significantly influence your health care service? | Yes | 322 | 63 | 245 | 45.7 | 567 | 54 |

| Some what | 169 | 33 | 212 | 39.6 | 381 | 36.5 | |

| No | 21 | 4 | 79 | 14.7 | 100 | 9.5 | |

| Awarnes about NTDs | Yes | 383 | 74 | 326 | 60.8 | 709 | 67.6 |

| No | 129 | 26 | 210 | 39.2 | 339 | 32.4 | |

| From where you frequently got health care information | Health workers | 161 | 31 | 396 | 74 | 557 | 53 |

| Mass media | 234 | 46 | 10 | 2 | 244 | 44.3 | |

| Others | 17 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 28 | 2.7 | |

| Do any of the children have NTD in the previous two months? | Yes | 61 | 12 | 86 | 16 | 147 | 14 |

| No | 451 | 88 | 450 | 84 | 901 | 86 | |

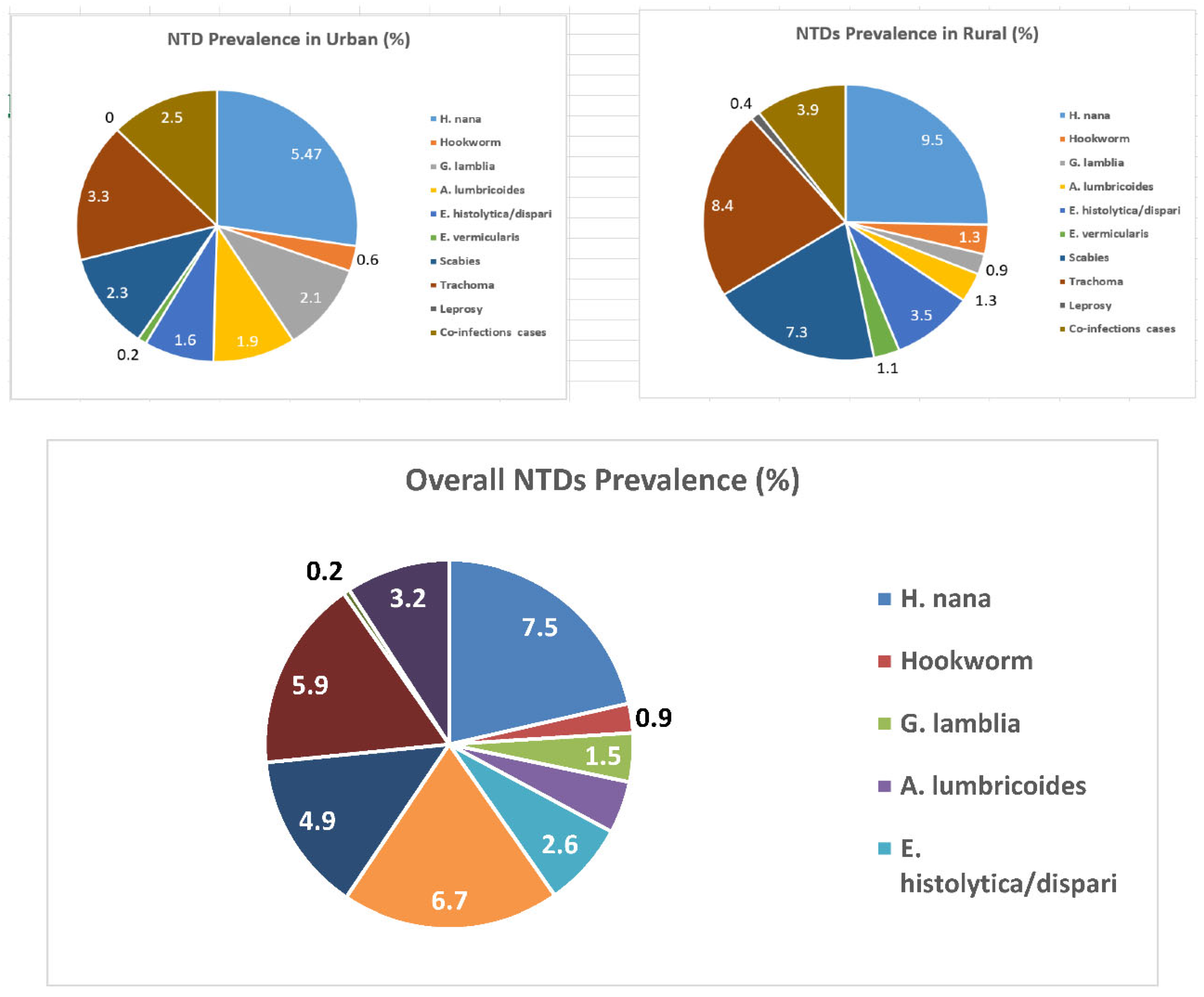

| Category of NTDs | Type of NTD diagnosed | Urban (Freq.) | Rural (Freq.) | Total (Freq.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STH | H. nana | 19 | 43 | 62 |

| Hookworm | 3 | 6 | 9 | |

| A. lumbricoides | 6 | 7 | 13 | |

| E. vermicularis | 1 | 6 | 7 | |

| Protozoa | E. histolytica/dispari | 5 | 13 | 18 |

| G. lamblia | 8 | 1 | 9 | |

| Eye infection | Trachoma | 13 | 35 | 48 |

| Skin diseases | Scabies | 9 | 26 | 35 |

| Leprosy | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mixed infections | A. lumbricoides and H.nona | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| A. lumbricoides and Scabies | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| H. nana and Scabies | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| H. nana and Trachoma | 3 | 5 | 8 | |

| E. histolytica/dispari and G. lamblia | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| E. histolytica/dispari and Trachoma | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| E. histolytica/dispari and Scabies | 0 | 3 | 3 | |

| Hookworm and Scabies | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Trachoma and Scabies | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Leprosy, Scabies and Trachoma | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total NTD positive cases | 77 | 159 | 236 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).