Submitted:

22 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

1.1. Background

Methodology

2.1. Study Site Description

2.2. Study Design and Approach

2.3. Study Population

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Sampling

2.5. Study Variables

2.6. Data Collection Techniques and Tools

2.7. Data Analysis

2.7.1. Determining the Spatial Distribution of the TB Cases

2.7.2. Determining the Trend of TB Treatment Outcomes over Time

2.7.3. Determining the Predictors of TB Treatment Outcomes

2.8. Ethical Considerations

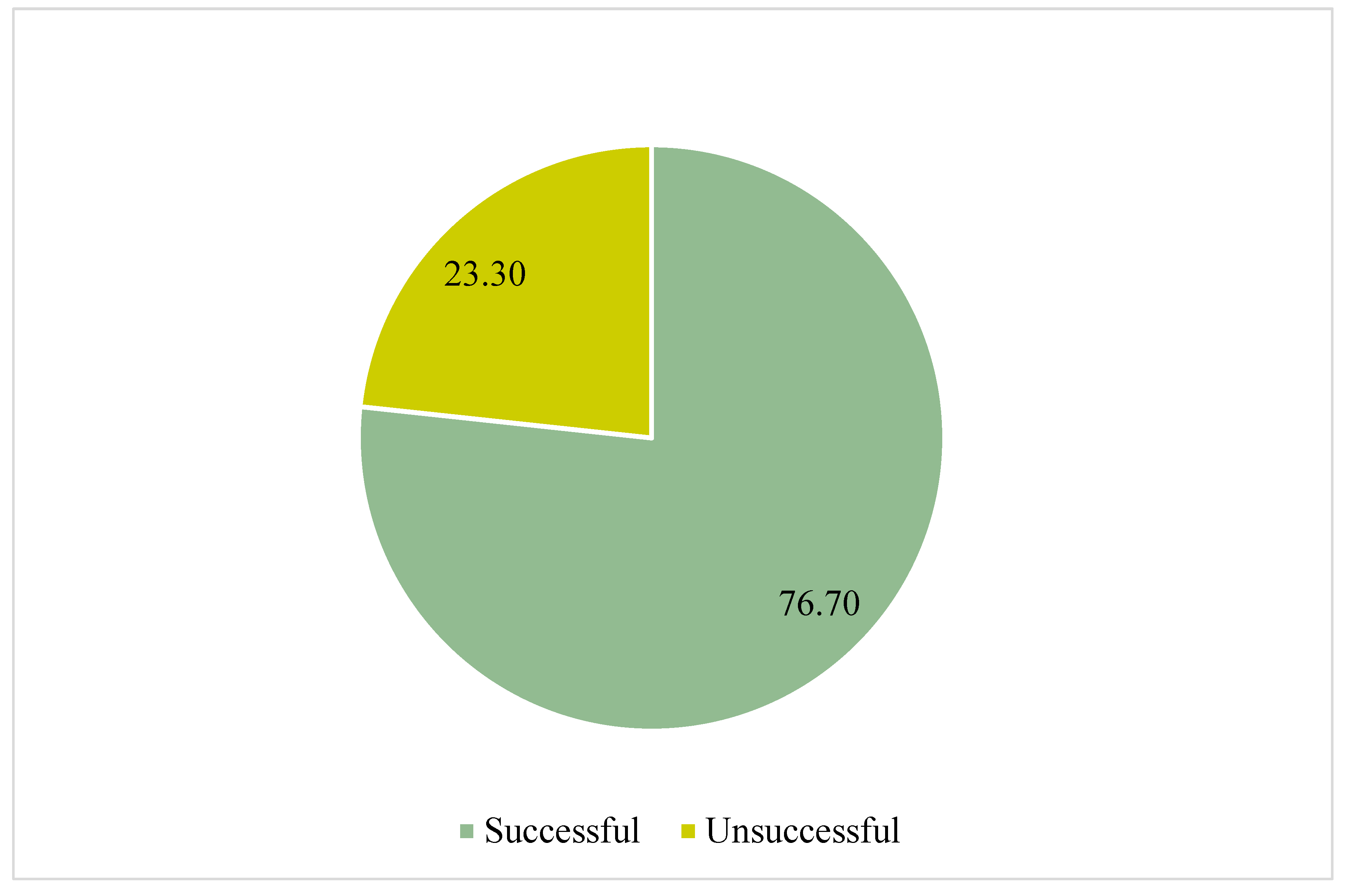

Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Medical Information of the Cohort

3.3. Spatial Distribution of the TB Cases

3.3.1. Global Moran’s I Summary

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Moran's Index | 0.03 |

| z-score | 19.04 |

| p-value | 0.00 |

3.3.2. Case Density and Hotspots

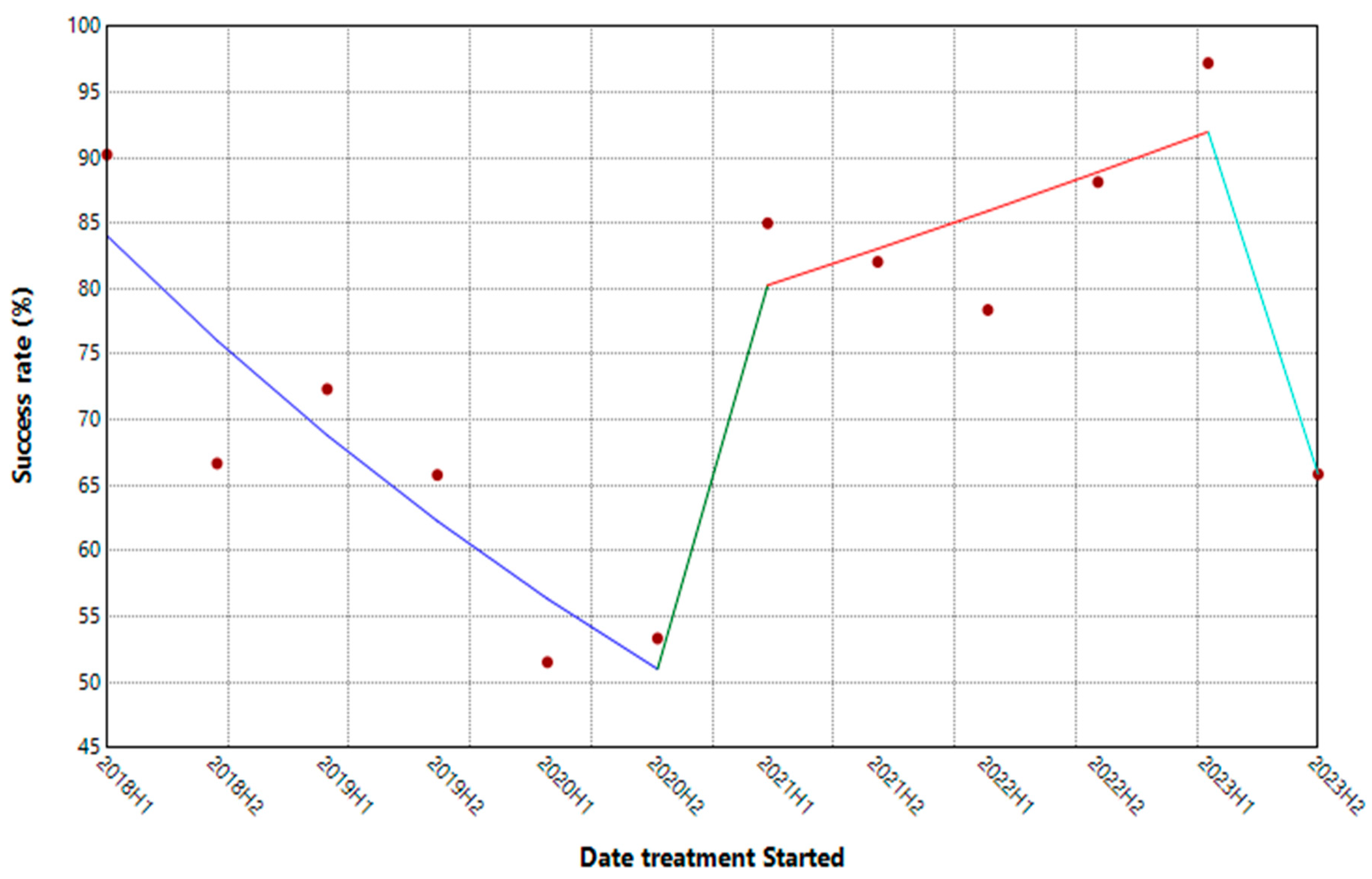

3.4. Tuberculosis Outcomes Treatment over Time

| Segment | HPC | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018H1 - 2020H2 | -18.12* | -29.25, -9.03 | 0.03 |

| 2020H2 - 2021H1 | 147.88 | -29.53, 236.13 | 0.14 |

| 2021H1-2023H1 | 7.04 | -3.20, 140.58 | 0.14 |

| 2023H1-2023H2 | -48.74* | -65.59, -6.79 | 0.00 |

3.5. Predictors of Successful TB Treatment Outcome

3.5.1. Cross-Tabulation of Demographics and Treatment Outcome

3.5.2. Cross-Tabulation of Medical Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes

3.5.3. Binary Logistics Regression Predicting the Factors Associated with Unsuccessful TB Treatment Outcome

Discussion

4.1. Geospatial Distribution of the TB Cases

4.2. Trend of TB Treatment Outcomes

4.3. Predictors of Tuberculosis Treatment Outcomes

Conclusion and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Limitations of the Study

- The complete use of secondary data for this study may have introduced potential biases due to the data accuracy. However, the data was extracted twice by two groups, which was validated, and any errors found were duly amended as appropriate. This would limit the potential biases that could have been introduced during the data collection.

- The study may not have fully accounted for potential confounding variables due to the sole use of secondary data, which does not capture the wider determinants.

5.3. Recommendations

5.3.1. For Policymakers

- Implement focused TB control measures in hotspot zones, especially in densely populated and mining communities, including increased screening, awareness campaigns, and community engagement to reduce transmission rates.

- Strengthen the role of TB treatment supporters to improve adherence and treatment success. Training and deploying community health workers to provide support and follow-up can be crucial in these high-risk areas.

- Ensure that patients have at least one follow-up laboratory test during their treatment. This can help detect adverse treatment outcomes early and adjust therapy as needed.

- Incorporating multisectoral approaches, such as involving mining companies in formulating and implementing TB control strategies.

5.3.2. For Future Research

- Prospective studies using primary data are recommended in future research to identify the wider determinants of TB treatment outcomes.

- Future research should expand the geographical area and use a longer period to capture more comprehensive trends and variations in TB incidence and treatment outcomes.

References

- World Health Organisation. Global tuberculosis report 2024 [Internet]. Geneva: 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports.

- Talip BA, Sleator RD, Lowery CJ, Dooley JSG, Snelling WJ. An Update on Global Tuberculosis (TB). Infectious Diseases: Research and Treatment [Internet] 2013;6(1):39–50. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3988623/.

- Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling. PLoS Med [Internet] 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. [CrossRef]

- Cohen A, Mathiasen VD, Schön T, Wejse C. The global prevalence of latent tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2019;54(3):1900655. [CrossRef]

- Behr MA, Edelstein PH, Ramakrishnan L. Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis. BMJ 2018;362(1):k2738. [CrossRef]

- Brett K, Dulong C, Severn M. Tuberculosis in People with Compromised Immunity: A Review of Guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2020. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562936/.

- World Health Organisation. Implementing the TB strategy: The Essentials, 2022 update [Internet]. Geneva: 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240065093.

- Ministry of Health. 2022 Holistic Assessment Report [Internet]. Accra: 2023. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.gh/annual-reviews/.

- Agyare SA, Osei FA, Odoom SF, Mensah NK, Amanor E, Martyn-Dickens C, et al. Treatment Outcomes and Associated Factors in Tuberculosis Patients at Atwima Nwabiagya District, Ashanti Region, Ghana: A Ten-Year Retrospective Study. Tuberc Res Treat 2021;2021(1):9952806. [CrossRef]

- Bonsu EO, Addo IY, Adjei BN, Alhassan MM, Nakua EK. Prevalence, treatment outcomes and determinants of TB–HIV coinfection: a 10-year retrospective review of TB registry in Kwabre East Municipality of Ghana. BMJ Open [Internet] 2023;13(3):e067613. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/13/3/e067613.

- Chimeh RA, Gafar F, Pradipta IS, Akkerman OW, Hak E, Alffenaar JWC, et al. Clinical and economic impact of medication non-adherence in drug-susceptible tuberculosis: a systematic review. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2020;24(8):811–9. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Zhu Z, Dulberger D, Stanley S, Wilson W, Chung C, et al. Tuberculosis treatment failure associated with evolution of antibiotic resilience. Science (1979) [Internet] 2022;378(6624):1111–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq2787. [CrossRef]

- Soedarsono S, Mertaniasih NM, Kusmiati T, Permatasari A, Ilahi WK, Anggraeni AT. Characteristics of Previous Tuberculosis Treatment History in Patients with Treatment Failure and the Impact on Acquired Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Antibiotics 2023;12(3):598. [CrossRef]

- Nzema East Health Administration. 2023 Annual Report. 2024.

- Camargo LMA, Silva RPM, Meneguetti DUDO. Research methodology topics: Cohort studies or prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Journal of Human Growth and Development 2019;29(3):433–6. [CrossRef]

- Pearson DR, Werth VP. Geospatial Correlation of Amyopathic Dermatomyositis With Fixed Sources of Airborne Pollution: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6(1):85. [CrossRef]

- Xu W, Zhao Y, Nian S, Feng L, Bai X, Luo X, et al. Differential analysis of disease risk assessment using binary logistic regression with different analysis strategies. Journal of International Medical Research 2018;46(9):3656. [CrossRef]

- Zabor EC, Reddy CA, Tendulkar RD, Patil S. Logistic Regression in Clinical Studies. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics 2022;112(2):271.

- Chowdhury MZI, Turin TC. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8(1):e000262. [CrossRef]

- Tomita A, Smith CM, Lessells RJ, Pym A, Grant AD, Oliveira T De, et al. Space-time clustering of recently-diagnosed tuberculosis and impact of ART scale-up: Evidence from an HIV hyper-endemic rural South African population. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):10724. [CrossRef]

- Iddrisu AK, Amikiya EA, Bukari FK. Spatio-temporal characteristics of Tuberculosis in Ghana. F1000Res 2023;11(1):200.

- Abdul IW, Ankamah S, Iddrisu AK, Danso E. Space-time analysis and mapping of prevalence rate of tuberculosis in Ghana. Sci Afr [Internet] 2020;7(2):e00307. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468227620300454. [CrossRef]

- Teibo TKA, Andrade RLDP, Rosa RJ, Tavares RBV, Berra TZ, Arcêncio RA. Geo-spatial high-risk clusters of Tuberculosis in the global general population: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023;23(1):1586. [CrossRef]

- Coleman M, Martinez L, Theron G, Wood R, Marais B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Transmission in High-Incidence Settings—New Paradigms and Insights. Pathogens 2022;11(11):1228. [CrossRef]

- Ohene SA, Bonsu F, Adusi-Poku Y, Dzata F, Bakker M. Case finding of tuberculosis among mining communities in Ghana. PLoS One 2021;16(3):e0248718. [CrossRef]

- Mbuya AW, Mboya IB, Semvua HH, Mamuya SH, Msuya SE. Prevalence and factors associated with tuberculosis among the mining communities in Mererani, Tanzania. PLoS One 2023;18(3):e0280396. [CrossRef]

- Osei E, Oppong S, Adanfo D, Doepe BA, Owusu A, Kupour AG, et al. Reflecting on tuberculosis case notification and treatment outcomes in the Volta region of Ghana: a retrospective pool analysis of a multicentre cohort from 2013 to 2017. Glob Health Res Policy 2019;4(1):37. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023 [Internet]. Geneva: 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023.

- Ebrahimpour S, Saleki K, Agazhu HW, Assefa ZM, Beshir T, Tadesse H, et al. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among tuberculosis patients attending Gurage Zone Public Hospital, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region, Ethiopia: an institution-based cross-sectional study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023;10(1):1105911.

- Torres NMC, Rodríguez JJQ, Andrade PSP, Arriaga MB, Netto EM. Factors predictive of the success of tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14(12):e0226507. [CrossRef]

- Alipanah N, Jarlsberg L, Miller C, Linh NN, Falzon D, Jaramillo E, et al. Adherence interventions and outcomes of tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials and observational studies. PLoS Med 2018;15(7):e1002595. [CrossRef]

- Maynard C, Tariq S, Sotgiu G, Migliori GB, van den Boom M, Field N. Psychosocial support interventions to improve treatment outcomes for people living with tuberculosis: a mixed methods systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine [Internet] 2023;61(1):102057. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589537023002341. [CrossRef]

- Appiah MA, Arthur JA, Asampong E, Kamau EM, Gborgblorvor D, Solaga P, et al. Health service providers’ perspective on barriers and strategies to tuberculosis treatment adherence in Obuasi Municipal and Obuasi East District in the Ashanti region, Ghana: a qualitative study. Discover Health Systems 2024;3(1).

- Faridi KF, Peterson ED, McCoy LA, Thomas L, Enriquez J, Wang TY. Timing of First Postdischarge Follow-up and Medication Adherence After Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol [Internet] 2016;1(2):147–55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0001. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=545) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years): | ||

| 4-14 | 8 | 1.47 |

| 15-24 | 60 | 11.01 |

| 25-34 | 116 | 21.28 |

| 35-44 | 150 | 27.52 |

| 45-54 | 130 | 23.85 |

| 55+ | 81 | 14.86 |

| Mean age (SD): | 41 (14.16) | |

| Gender: | ||

| female | 173 | 31.74 |

| male | 372 | 68.26 |

| Residence category: | ||

| rural | 327 | 60.00 |

| urban | 218 | 40.00 |

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=545) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Infection site: | ||

| extra Pulmonary | 14 | 2.57 |

| pulmonary | 531 | 97.43 |

| At least one follow-up lab: | ||

| no | 118 | 21.65 |

| yes | 427 | 78.35 |

| Year of treatment start: | ||

| 2018 | 68 | 12.48 |

| 2019 | 85 | 15.6 |

| 2020 | 63 | 11.56 |

| 2021 | 79 | 14.5 |

| 2022 | 96 | 17.61 |

| 2023 | 154 | 28.25 |

| HIV status: | ||

| negative | 497 | 91.19 |

| positive | 48 | 8.81 |

| Characteristics | Treatment Outcome | χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successful | Unsuccessful | |||

| Age group: | 8.19 | 0.14a | ||

| <15 | 6(1.44) | 2(1.57) | ||

| 15-24 | 49(11.72) | 11(8.66) | ||

| 25-34 | 85(20.33) | 31(24.41) | ||

| 35-44 | 122(29.19) | 28(22.05) | ||

| 45-54 | 102(24.40) | 28(22.05) | ||

| 55+ | 54(12.92) | 27(21.26) | ||

| Gender: | 1.04 | 0.31 | ||

| female | 128(30.62) | 45(35.43) | ||

| male | 290(69.38) | 82(64.57) | ||

| Residents’ category: | ||||

| rural | 243(58.13) | 84(66.14) | 2.60 | 0.11 |

| urban | 174(41.87) | 43(33.86) | ||

| Characteristics | Treatment Outcome | χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection site: | Successful | Unsuccessful | ||

| Extra Pulmonary | 12(2.87) | 2(1.57) | 0.65 | 0.33a |

| Pulmonary | 406(97.13) | 125(98.43) | ||

| At least one follow-up lab: | ||||

| no | 66(15.79) | 52(40.94) | 36.34 | 0.00* |

| yes | 352(84.21) | 75(59.06) | ||

| Year of treatment start: | ||||

| 2018 | 55(13.16) | 13(10.24) | 30.53 | 0.00* |

| 2019 | 59(14.11) | 26(20.47) | ||

| 2020 | 33(7.89) | 30(23.62) | ||

| 2021 | 66(15.79) | 13(10.24) | ||

| 2022 | 81(19.38) | 15(11.81) | ||

| 2023 | 124(29.67) | 30(23.62) | ||

| Treatment support: | ||||

| no | 34(8.13) | 23(18.11) | 10.35 | 0.00* |

| yes | 384(91.87) | 104(81.89) | ||

| HIV status: | ||||

| negative | 381(91.15) | 116(91.34) | 0.03 | 0.94 |

| positive | 37(8.85) | 11(8.66) | ||

| Characteristics | Treatment Outcome (Unsuccessful) | |

|---|---|---|

| cOR [95% CI] | aOR [95% CI] | |

| Age group: | ||

| <15 | 1.00(ref) | 1.00(ref) |

| 15-24 | 0.67 [0.12, 3.79] | 0.72[0.12, 4.47] |

| 25-34 | 1.09 [0.21, 5.71] | 0.95 [0.17, 5.42] |

| 35-44 | 0.69 [0.13, 3.59] | 0.70 [0.12, 3.99] |

| 45-54 | 0.82 [0.16, 4.31] | 0.86 [0.15, 4.91] |

| 55+ | 1.50 [0.28, 7.93] | 1.46 [0.25, 8.49] |

| Gender: | ||

| female | 1.00(ref) | |

| male | 0.80 [0.53, 1.22] | |

| Residents’ category | ||

| rural | 1.00(ref) | |

| urban | 0.71 [0.47, 1.08] | |

| Infection site: | ||

| extrapulmonary | 1.00(ref) | |

| pulmonary | 1.85 [0.41, 8.36] | |

| At least one follow-up lab: | ||

| no | 1.00(ref) | 1.00(ref) |

| yes | 0.27 [0.17, 0.42]* | 0.25 [0.15, 0.42]* |

| Year of diagnosis: | ||

| 2018 | 1.00(ref) | 1.00(ref) |

| 2019 | 1.86 [0.87, 3.99] | 1.90 [0.86, 4.24] |

| 2020 | 3.85 [1.76, 8.40]* | 2.97 [1.30, 6.81]* |

| 2021 | 0.83 [0.36, 1.95] | 0.78 [0.32, 1.89] |

| 2022 | 0.78 [0.35, 1.78] | 0.62 [0.26, 1.48] |

| 2023 | 1.02 [0.50, 2.11] | 0.65 [0.29, 1.42] |

| Treatment support: | ||

| no | 1.00(ref) | 1.00(ref) |

| yes | 0.40 [0.23, 0.71]* | 0.43 [0.23, 0.80]* |

| HIV status: | ||

| negative | 1.00(ref) | |

| positive | 0.98 [0.48, 1.98] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).