Submitted:

13 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Process of Selecting Studies

2.4. Synthesis of Data

3. Physiology and Function of Gut Microbiota

4. Unique Characteristics of the Pediatric Gut Microbiota

5. Disruption of the Gut Microbiota in Intestinal Paediatric Surgical Diseases

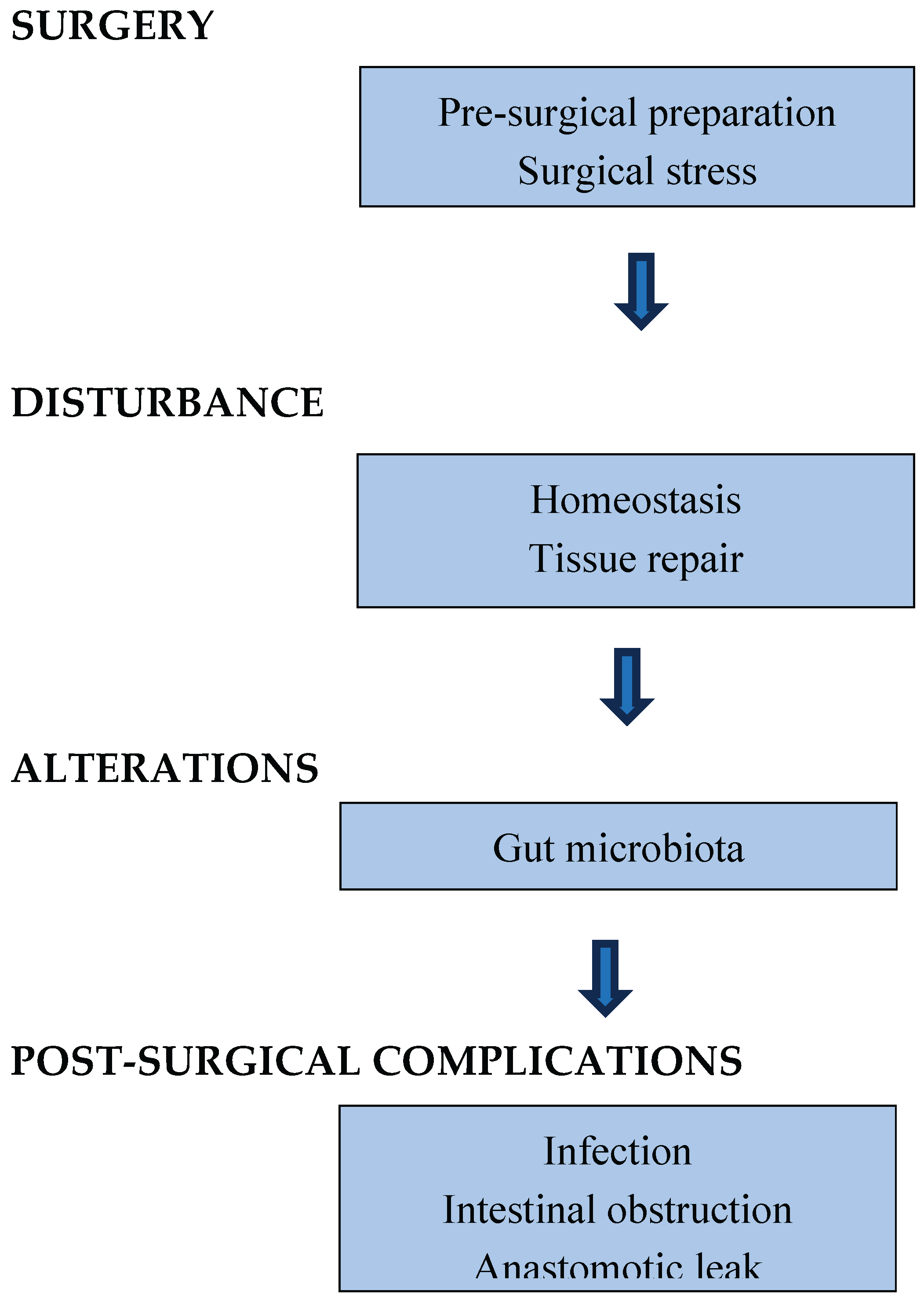

6. Impact of Surgical Stress on Gut Microbiota in Paediatric Patients

7. Alterations of Gut Microbiota After Intestinal Surgery in Paediatric Diseases

7.1. Necrotizing Enterocolitis

7.2. Hirschsprung’s Disease and Hirschsprung’s-associated Enterocolitis

7.3. Inflammatory Bowel Disease

7.4. Short Bowel Syndrome

8. GM-Related Post-surgical Complications of Intestinal Surgery in Paediatric Patients

8.1. Infection

8.2. Intestinal Obstruction

8.3. Anastomotic Leak

9. Future Research

9.1. Elucidating Causal Mechanisms Through Germ-free Models

9.2. The Pre-surgical Microbiota Profile: An Indicator for Surgical Readiness

9.2.1. Dietary Prehabilitation and Stools Biomarkers

9.2.2. Precision Antimicrobial Therapy

9.2.3. Probiotics, Prebiotics, Synbiotics

9.2.4. Immunonutrition

9.3. Precision Microbiota Engineering

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GM | Gut microbiota |

| NEC | Necrotizing enterocolitis |

| HD | Hirschsprung’s disease |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| SBS | Short bowel syndrome |

| HAEC | Hirschsprung’s-associated-enterocolitis |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| SCFAs | Short-chains fatty acids |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CD | Chron’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| IO | Intestinal obstruction |

| AL | Anastomotic leak |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureous |

References

- Takisha, T.; Fenero, C.I.M.; Câmara, N.O.S. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1373208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankole, T.; Li, Y. The early-life gut microbiome in common pediatric diseases: roles and therapeutic implications. Front Nutr. 2025, 12, 1597206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamanga, N.H.B.; Thomas, R.; Thandrayen, K.; Velaphi, S.C. Risk factors and outcomes of infants with necrotizing enterocolitis: a case-control study. Front Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1611111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini Prato, A.; Rossi, V.; Avanzini, S.; Mattioli, G.; Disma, N.; Jasonni, V. Hirschsprung's disease: what about mortality? Pediatr Surg Int. 2011, 27, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolho, KL.; Nikkonen, A.; Merras-Salmio, L.; Molander, P. The need for surgery in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with biologicals. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024, 39, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Z.; O'Daniel, E.L. Updates in intestinal failure management. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decembrino, N.; Scuderi, M.G.; Betta, P.M.; Leonardi, R.; Bartolone, A.; Marsiglia, R.; Marangelo, C.; Pane, S.; De Rose, D.U.; Salvatori, G.; Grosso, G.; Di Domenico, F.M.; Dotta, A.; Putignani, L.; Capolupo, I.; Di Benedetto, V. Microbiota-Modulating Strategies in Neonates Undergoing Surgery for Congenital Gastrointestinal Conditions: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibiino, G.; Binda, C.; Cristofaro, L.; Sbrancia, M.; Coluccio, C.; Petraroli, C.; Jung, C.F.M.; Cucchetti, A.; Cavaliere, D.; Ercolani, G.; Sambri, V.; Fabbri, C. Dysbiosis and Gastrointestinal Surgery: Current Insights and Future Research. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cui, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, D.; Wang, K.; Hou, S. Role of gut microbiota in postoperative complications and prognosis of gastrointestinal surgery: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e29826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Shi, L.; Shi, W.; Du, L.; Ni, Y. Alteration of the gut microbiota after surgery in preterm infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. Front Pediatr. 2023, 11, 993759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuvonen, MI.; Korpela, K.; Kyrklund, K.; Salonen, A.; de Vos, W.; Rintala, R.J.; Pakarinen, M.P. Intestinal Microbiota in Hirschsprung Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018, 67, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thänert, R.; Thänert, A.; Ou, J.; Bajinting, A.; Burnham, C.D.; Engelstad, H.J.; Tecos, M.E.; Ndao, I.M.; Hall-Moore, C.; Rouggly-Nickless, C.; Carl, M.A.; Rubin, D.C.; Davidson, N.O.; Tarr, P.I.; Warner, B.B.; Dantas, G.; Warner, B.W. Antibiotic-driven intestinal dysbiosis in pediatric short bowel syndrome is associated with persistently altered microbiome functions and gut-derived bloodstream infections. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1940792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleminson, J.S.; Thomas, J.; Stewart, C.J.; Campbell, D.; Gennery, A.; Embleton, N.D.; Köglmeier, J.; Wong, T.; Spruce, M.; Berrington, J.E. Gut microbiota and intestinal rehabilitation: a prospective childhood cohort longitudinal study of short bowel syndrome (the MIRACLS study): study protocol. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2024, 11, e001450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packey, C.D.; Sartor, R.B. Commensal bacteria, traditional and opportunistic pathogens, dysbiosis and bacterial killing in inflammatory bowel diseases. CurrOpin Infect Dis. 2009, 22, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimura, T.; Rizzello, F.; Helwig, U.; Poggioli, G.; Schreiber, S.; Talbot, I.C.; Nicholls, R.J.; Gionchetti, P.; Campieri, M.; Kamm, M.A. Once daily high dose probiotic therapy (VSL#3) for maintaining remission in recurrent or refractory pouchitis. Gut. 2004, 53, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Feng, J. Probiotics prevent Hirschsprung's disease-associated enterocolitis: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015, 30, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Haens, G.R.; Vermeire, S.; Van Assche, G.; Noman, M.; Aerden, I.; Van Olmen, G.; Van Olmen, G.; Rutgeerts, P. Therapy of metronidazole with azathioprine to prevent postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a controlled randomized trial. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, M.H.; Soraisham, A.; Bagga, N.; Massieu, L.A.; Maheshwari, A. Nutritional Management of Short Bowel Syndrome. Clin Perinatol. 2022, 49, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464(7285), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.F.; Lee, Y.Y. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Health, Diet, and Disease with a Focus on Obesity. Foods 2025, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazinet, AL; Cummings, MP. A comparative evaluation of sequence classification programs. BMC Bioinformatics 2012, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugon, P; Dufour, JC; Colson, P; Fournier, PE; Sallah, K; Raoult, D. A comprehensive repertoire of prokaryotic species identified in human beings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015, 15, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.M.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011, 473(7346), 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laterza, L.; Rizzatti, G.; Gaetani, E.; Chiusolo, P.; Gasbarrini, A. The Gut Microbiota and Immune System Relationship in Human Graft-versus-Host Disease. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016, 8, e2016025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariat, D; Firmesse, O; Levenez, F; Guimarăes, V; Sokol, H; Doré, J; Corthier, G; Furet, JP. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.V.; Macpherson, A.J. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010, 10, 59–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J; Thiele, I; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur J Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krautkramer, K.A.; Fan, J.; Bäckhed, F. Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; Pomare, E.W.; Branch, W.J.; Naylor, C.P.; Macfarlane, G.T. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987, 28, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascale, A; Marchesi, N; Marelli, C; Coppola, A; Luzi, L; Govoni, S; Giustina, A; Gazzaruso, C. Microbiota and metabolic diseases. Endocrine 2018, 61, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; He, L.H.; Xu, L.J.; Li, S.B. Short-chain fatty acids: bridges between diet, gut microbiota, and health. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1728–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuy-Aubert, V.; Ravussin, Y. Short chain fatty acids: the messengers from down below. Front Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1197759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, L.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. The role of short-chain fatty acids in intestinal barrier function, inflammation, oxidative stress, and colonic carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Res. 2021, 165, 105420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MogoşGFR; ManciuleaProfir, M; Enache, RM; Pavelescu, LA; Popescu Roşu, OA; Cretoiu, SM; Marinescu, I. Intestinal Microbiota in Early Life: Latest Findings Regarding the Role of Probiotics as a Treatment Approach for Dysbiosis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, G.; Collins, S.M.; Bercik, P. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enaud, R.; Prevel, R.; Ciarlo, E.; Beaufils, F.; Wieërs, G.; Guery, B.; Delhaes, L. The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.K.; Azmal, M.; Haque, A.S.N.B.; Meem, M.; Talukder, O.F.; Ghosh, A. Unlocking the secrets of the human gut microbiota: Comprehensive review on its role in different diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 99913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.W.; Chen, M.J. Exploring the Preventive and Therapeutic Mechanisms of Probiotics in Chronic Kidney Disease through the Gut-Kidney Axis. J Agric Food Chem. 2024, 72, 8347–8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliocca, G.; Mone, P.; Di Iorio, B.R.; Heidland, A.; Marzocco, S. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Chronic Kidney Disease: Focus on Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ning, X.; Liu, B.; Dong, R.; Bai, M.; Sun, S. Specific alterations in gut microbiota in patients with chronic kidney disease: an updated systematic review. Ren Fail. 2021, 43, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrio, F; Martini, S; Francavilla, R; Corvaglia, L; Cristofori, F; Mastrolia, SA; Neu, J; Rautava, S; Russo Spena, G; Raimondi, F; Loverro, G. Epigenetic Matters: The Link between Early Nutrition, Microbiome, and Long-term Health Development. Front Pediatr. 2017, 5, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavineni, M.; Wassenaar, T.M.; Agnihotri, K.; Ussery, D.W.; Lüscher, T.F.; Mehta, JL. Mechanisms linking preterm birth to onset of cardiovascular disease later in adulthood. Eur Heart J. 2019, 40, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker-Tejeda, T.C.; Zubeldia-Varela, E.; Macías-Camero, A.; Alonso, L.; Martín-Antoniano, I.A.; Rey-Stolle, M.F.; Mera-Berriatua, L.; Bazire, R.; Cabrera-Freitag, P; Shanmuganathan, M.; Britz-McKibbin, P.; et al. Comparative characterization of the infant gut microbiome and their maternal lineage by a multi-omics approach. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Shi, Z.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Li, X. Research focus and emerging trends of the gut microbiome and infant: a bibliometric analysis from 2004 to 2024. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1459867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R; Wang, Y; Ying, Z; Shi, Z; Song, Y; Yan, J; Hou, S; Zhao, Z; Hu, Y; Chen, Q; Peng, W; Li, X. Inspecting mother-to-infant microbiota transmission: disturbance of strain inheritance by cesarian section. FrontMicrobiol 2024, 15, 1292377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmakers, S.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.; Faas, M. The matter of the reproductive microbiome. Obstet Med. 2019, 12, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaard, K.; Ma, J.; Antony, K.M.; Ganu, R.; Petrosino, J.; Versalovic, J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014, 6(237), 237ra65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, E.; Fernández, L.; Marín, M.L.; Martín, R.; Odriozola, J.M.; Nueno-Palop, C.; Narbad, A.; Olivares, M.; Xaus, J.; Rodríguez, J.M. Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section. CurrMicrobiol 2005, 51, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinson, L.F.; Payne, M.S.; Keelan, J.A. Planting the seed: Origins, composition, and postnatal health significance of the fetal gastrointestinal microbiota. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2017, 43, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Mao, L.; Yu, M.; Xu, J. The Placental Microbiome Varies in Association with Low Birth Weight in Full-Term Neonates. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6924–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; Alvarez, A.S.; de Vos, W.M. The Gut Microbiota in the First Decade of Life. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlisle, E.M.; Morowitz, M.J. Pediatric surgery and the human microbiome. J Pediatr Surg. 2011, 46, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.B.; Konya, T.; Maughan, H.; Guttman, D.S.; Field, C.J.; Chari, R.S.; Sears, M.R.; Becker, A.B.; Scott, J.A.; Kozyrskyj, A.L. CHILD Study Investigators. Gut microbiota of healthy Canadian infants: profiles by mode of delivery and infant diet at 4 months. CMAJ 2013, 185, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penders, J.; Thijs, C.; Vink, C.; Stelma, F.F.; Snijders, B.; Kummeling, I.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Stobberingh, EE. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed, F.; Roswall, J.; Peng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Jia, H.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Li, Y.; Xia, Y.; Xie, H.; Zhong, H.; et al. Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe. 2015, 17, 690–703, Erratum in: Cell Host Microbe. 2015,17, 852. Jun, Wang [corrected to Wang, Jun]. Erratum in: Cell Host Microbe. 2015,17,852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozé, J.C.; Ancel, P.Y.; Marchand-Martin, L.; Rousseau, C.; Montassier, E.; Monot, C.; Le Roux, K.; Butin, M.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Aires, J.; et al. Assessment of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Practices and Preterm Newborn Gut Microbiota and 2-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2020, 3, e2018119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Xun, P.; Wang, X.; He, K.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Tang, W.; Lu, L.; Yan, W.; Wang, W.; Hu, T; Cai, W. Impact of Postnatal Antibiotics and Parenteral Nutrition on the Gut Microbiota in Preterm Infants During Early Life. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020, 44, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hooi, S.L.; Choo, Y.M.; The, C.S.J.; Toh, K.Y.; Lim, L.W.Z.; Lee, Y.Q.; Chong, C.W.; Ahmad Kamar, A. Progression of gut microbiome in preterm infants during the first three months. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 12104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.J.; Ajami, N.J.; O'Brien, J.L.; Hutchinson, D.S.; Smith, D.P.; Wong, M.C.; Ross, M.C.; Lloyd, R.; Doddapaneni, H.; Metcalf, G.A.; et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018, 562(7728), 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsunenko, T; Rey, FE; Manary, MJ; Trehan, I; Dominguez-Bello, MG; Contreras, M; Magris, M; Hidalgo, G; Baldassano, RN; Anokhin, AP; Heath, AC; Warner, B; Reeder, J; Kuczynski, J; Caporaso, JG; Lozupone, CA; Lauber, C; Clemente, JC; Knights, D; Knight, R; Gordon, JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012, 486(7402), 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, E.B.; Riehle, K.; Luna, R.A.; Weidler, E.M.; Rubio-Gonzales, M.; Mistretta, T.A.; Raza, S.; Doddapaneni, H.V.; Metcalf, G.A.; Muzny, D.M.; et al. Structure and function of the healthy pre-adolescent pediatric gut microbiome. Microbiome 2015, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyton, K; Alverdy, J.C. The gut microbiota and gastrointestinal surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017, 14, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morowitz, MJ; Babrowski, T; Carlisle, EM; Olivas, A; Romanowski, KS; Seal, JB; Liu, DC; Alverdy, JC. The human microbiome and surgical disease. Ann Surg. 2011, 253, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Shao, K.; Zhu, X.; Cong, Y.; Zhao, X. Gut microbiota and butyrate contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopause due to estrogen deficiency. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0262855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharairi, N.A. Therapeutic Potential of Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolite Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, L.; Troester, A.; Jahansouz, C. The Impact of Surgical Bowel Preparation on the Microbiome in Colon and Rectal Surgery. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 23(13), 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalluri, H; Kizy, S; Ewing, K; Luthra, G; Leslie, DB; Bernlohr, DA; Sadowsky, MJ; Ikramuddin, S; Khoruts, A; Staley, C; Jahansouz, C. Peri-operative antibiotics acutely and significantly impact intestinal microbiota following bariatric surgery. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 20340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, L.; Yu, G.; Li, Y.; Wei, K.; Lin, L.; Ye, Y. Interaction between gut microbiota and anesthesia: mechanism exploration and translation challenges focusing on the gut-brain-liver axis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1626585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.; Shorten, G.D.; O'Mahony, S.M. Postoperative pain and the gut microbiome. Neurobiol Pain 2021, 10, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, Z.E.; DiBaise, J.; Dautel, S.E.; Isern, N.G.; Kim, Y.M.; Hoyt, D.W.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Brewer, H.M.; Weitz, K.K.; et al. Temporospatial shifts in the human gut microbiome and metabolome after gastric bypass surgery. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paine, H.; Jones; Kinross, J. Preparing the Bowel (Microbiome) for Surgery: Surgical Bioresilience. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2023, 36, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, NK.; Al-Beltagi, M.; Bediwy, A.S.; El-Sawaf, Y.; Toema, O. Gut microbiota in various childhood disorders: Implication and indications. World J Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1875–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihekweazu, F.D.; Versalovic, J. Development of the Pediatric Gut Microbiome: Impact on Health and Disease. Am J Med Sci. 2018, 356, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; LI, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Lv, J.; Li, Q.; L, Y. Intestinal microecology in pediatric surgery-related diseases: Current insights and future perspectives. J Pediatr Surg Open. 2024, 6, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.C.; Esvaran, M.; Patole, S.K.; Simmer, K.N.; Gollow, I.; Keil, A.; Wemheuer, B.; Chen, L.; Conway, P.L. Gut microbiota in neonates with congenital gastrointestinal surgical conditions: a prospective study. Pediatr Res. 2020, 88, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, F.; Gao, T.; Liu, T.; Zhu, H.; Sheng, Q.; Liu, J.; Lu, L.; Lv, Z. Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio as an early biomarker for NEC development in preterm infants. J PediatrSurg 2025, 60, 162606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.S.; Cowles, R.A. Butyrate and the Intestinal Epithelium: Modulation of Proliferation and Inflammation in Homeostasis and Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Mukherjee, S.; DesMarais, V.; Albanese, J.M.; Rafti, E.; Draghi, Ii. A.; Maher, L.A.; Khanna, K.M.; Mani, S.; Matson, A.P. Targeting the PXR-TLR4 signaling pathway to reduce intestinal inflammation in an experimental model of necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res. 2018, 83, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Poroyko, V.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, L.; Wang, J.; Bao, N.; Hong, L. Characterization of the intestinal microbiome of Hirschsprung's disease with and without enterocolitis. BiochemBiophys Res Commun. 2014, 445, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budianto, I.R.; Kusmardi, K.; Maulana, A.M.; Arumugam, S.; Afrin, R.; Soetikno, V. Paneth-like cells disruption and intestinal dysbiosis in the development of enterocolitis in an iatrogenic rectosigmoid hypoganglionosis rat model. Front Surg. 2024, 11, 1407948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, A.P.; Hascoet, J.; Berneau, P.; LeGouevec, F.; Georges, J.; Randuineau, G.; Formal, M.; Henno, S.; Boudry, G. A piglet model of iatrogenic rectosigmoid hypoganglionosis reveals the impact of the enteric nervous system on gut barrier function and microbiota postnatal development. J Pediatr Surg. 2021, 56, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yan, H.; Jia, W.; Huang, J.; Fu, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, H.; Yang, W.; Pan, W.; Zheng, B.; et al. Association between gut microbiota and Hirschsprung disease: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1366181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, B.; Liu, X.; Li, A. The mediating role of metabolites between gut microbiome and Hirschsprung disease: a bidirectional two-step Mendelian randomization study. Front Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1371933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X; Liu, C; Zhan, S; Tian, Z; Li, N; Mao, R; Zeng, Z; Chen, M. Gut Microbiota Profile in Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Front Pediatr. 2021, 9, 626232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondheimer, JM; Asturias, E; Cadnapaphornchai, M. Infection and cholestasis in neonates with intestinal resection and long-term parenteral nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998, 27, 131–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meehan, JJ; GeorgesonKE. Prevention of liver failure in parenteral nutrition-dependent children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 1997, 32, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrand, Lilja. H; Wefer, H.; Nyström, N.; Finkel, Y.; Engstrand, L. Intestinal dysbiosis in children with short bowel syndrome is associated with impaired outcome. Microbiome 2015, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, H.G.; Fan, D.; Coughlin, L.A.; Ho, E.X.; McDaniel, M.M.; Channabasappa, N.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Zhan, X.; Xie, Y.; Koh, A.Y. Severe Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Is Associated With Poor Growth in Patients With Short Bowel Syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017, 41, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovics, Z.H.; Carter, B.A.; Luna, R.A.; Hollister, E.B.; Shulman, R.J.; Versalovic, J. The Fecal Microbiome in Pediatric Patients With Short Bowel Syndrome. JPEN J Parenter EnteralNutr 2016, 40, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, S.; Mongodin, E.F.; Hittle, L.; Huang, S.H.; Torres, C. The bacterial communities of the small intestine and stool in children with short bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0215351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phyo, L.Y.; Singkhamanan, K; Laochareonsuk, W.; Surachat, K.; Phutong, N.; Boonsanit, K.; Chiengkriwate, P.; Sangkhathat, S. Fecal microbiome alterations in pediatric patients with short bowel syndrome receiving a rotating cycle of gastrointestinal prophylactic antibiotics. Pediatr Surg Int. 2021, 37, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shogan, BD; Smith, DP; Christley, S; Gilbert, JA; Zaborina, O; Alverdy, JC. Intestinal anastomotic injury alters spatially defined microbiome composition and function. Microbiome 2014, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, J; Ericsson, A; Price, A; Manithody, C; Murry, DJ; Chhonker, YS; Buchanan, P; Lindsey, ML; Singh, AB; Jain, AK. Dysbiosis and Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Pediatric Congenital Heart Disease Is Exacerbated Following Cardiopulmonary Bypass. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2021, 6, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derikx, JP; Luyer, MD; Heineman, E; Buurman, WA. Non-invasive markers of gut wall integrity in health and disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 5272–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z; Ding, L; Lu, Q; Chen, YH. Claudins in intestines: Distribution and functional significance in health and diseases. Tissue Barriers 2013, 1, e24978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, JM; Plunkett, E; Galanko, J; Lichtman, S; Taylor, L; Maynor, A; Weiner, T; Freeman, K; GuariscoJL; Wu, GY. Serum citrulline levels correlate with enteral tolerance and bowel length in infants with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr. 2005, 146, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Gao; Xie, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Feng, X. Impact of Repeated Infantile Exposure to Surgery and Anesthesia on Gut Microbiota and Anxiety Behaviors at Age 6-9. J Pers Med. 2023, 13, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traini, I.; Chan, S.Y.; Menzies, J.; Hughes, J.; Coffey, M.J.; McKay, I.R.; Ooi, C.Y.; Leach, S.T.; Krishnan, U. Intestinal dysbiosis and inflammation in children with repaired esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2023, 78, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doğan, G.; İpek, H. The Development of Necrotizing Enterocolitis Publications: A Holistic Evolution of Global Literature with Bibliometric Analysis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2020, 30, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claud, E.C.; Walker, W.A. Hypothesis: inappropriate colonization of the premature intestine can cause neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coggins, S.A.; Wynn, J.L.; Weitkamp, J.H. Infectious causes of necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Perinatol. 2015, 42, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, D.; Stolfi, I.; Lana, S.; Moro, M.L. Nosocomial necrotizing enterocolitis outbreaks: epidemiology and control measures. Eur J Pediatr. 2001, 160, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, A.L.; Lagomarcino, A.J.; Schibler, K.R.; Taft, D.H.; Yu, Z.; Wang, B.; Altaye, M.; Wagner, M.; Gevers, D.; Ward, D.V.; et al. Early microbial and metabolomic signatures predict later onset of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Microbiome 2013, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hoenig, J.D.; Malin, K.J.; Qamar, S.; Petrof, E.O.; Sun, J.; Antonopoulos, D.A.; Chang, E.B.; Claud, E.C. 16S rRNA gene-based analysis of fecal microbiota from preterm infants with and without necrotizing enterocolitis. ISME J. 2009, 3, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Biton, M.; Haber, A.L.; Gunduz, N.; Eng, G.; Gaynor, L.T.; Tripathi, S.; Calibasi-Kocal, G.; Rickelt, S.; Butty, V.L.; et al. Ketone Body Signaling Mediates Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Adaptation to Diet. Cell. 2019, 178, 1115–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, T.M.; Wheaton, J.D.; Houtz, G.M.; Ciofani, M. JunB promotes Th17 cell identity and restrains alternative CD4+ T-cell programs during inflammation. Nat Commun. 2017, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermayr, F.; Hotta, R.; Enomoto, H.; Young, H.M. Development and developmental disorders of the enteric nervous system. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013, 10, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosain, A. Established and emerging concepts in Hirschsprung's-associated enterocolitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016, 32, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.E.; Coffey, M.J.; Chen, Q.; Adams, S.; Ooi, C.Y.; van Dorst, J. Altered Development of Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Inflammation in Children with Post-Operative Hirschsprung's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 10570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini Prato, A.; Bartow-McKenney, C.; Hudspeth, K.; Mosconi, M.; Rossi, V.; Avanzini, S.; et al. A Metagenomics Study on Hirschsprung's Disease Associated Enterocolitis: Biodiversity and Gut Microbial Homeostasis Depend on Resection Length and Patient's Clinical History. Front Pediatr. 2019, 7, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, N.L.; Pieretti, A.; Dowd, S.E.; Cox, S.B.; Goldstein, A.M. Intestinal aganglionosis is associated with early and sustained disruption of the colonic microbiome. NeurogastroenterolMotil 2012, 24, 874–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykman, P.K.; Nordenskjöld, A.; Kawaguchi, A.; Hui, T.T.; Granström, A.L.; Cheng, Z.; Tang, J.; Underhill, D.M.; Iliev, I.; Funari, V.A.; et al. HAEC Collaborative Research Group (HCRG). Characterization of Bacterial and Fungal Microbiome in Children with Hirschsprung Disease with and without a History of Enterocolitis: A Multicenter Study. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0124172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W; Su, Y; Yuan, C; Zhang, Y; Zhou, L; Peng, L; Wang, P; Chen, G; Li, Y; Li, H; Zhi, Z; Chang, H; Hang, B; Mao, JH; Snijders, AM; Xia, Y. Prospective study reveals a microbiome signature that predicts the occurrence of post-operative enterocolitis in Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) patients. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plekhova, V.; De Paepe, E.; Van Renterghem, K.; Van Winckel, M.; Hemeryck, L.Y.; Vanhaecke, L. Disparities in the gut metabolome of post-operative Hirschsprung's disease patients. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 16167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, J.J.; Rabah, R.; Hirschl, R.B.; Maspons, A.; Meier, D.; Teitelbaum, D.H. Anti-TNF-α treatment for post-anastomotic ulcers and inflammatory bowel disease with Crohn's-like pathologic changes following intestinal surgery in pediatric patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015, 31, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, R.S.; Sanderson, I.R.; Claesson, M.J. Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease and its Relationship with the Microbiome. Microb Ecol. 2021, 82, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelay, A.; Tullie, L.; Stanton, M. Surgery and paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. TranslPediatr 2019, 8, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Elijah, E.; Vargas, F.; Ackermann, G.; Humphrey, G.; Lau, R.; Weldon, K.C.; Sanders, J.G.; Panitchpakdi, M; et al. Gastrointestinal Surgery for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Persistently Lowers Microbiome and Metabolome Diversity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neut, C.; Bulois, P.; Desreumaux, P.; Membré, J.M.; Lederman, E.; Gambiez, L.; Cortot, A.; Quandalle, P.; van Kruiningen, H.; Colombel, J.F. Changes in the bacterial flora of the neoterminal ileum after ileocolonic resection for Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marteau, P.; Lémann, M.; Seksik, P.; Laharie, D.; Colombel, J.F.; Bouhnik, Y.; Cadiot, G.; Soulé, J.C.; Bourreille, A.; Metman, E.; et al. Ineffectiveness of Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 for prophylaxis of postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled GETAID trial. Gut. 2006, 55, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondot, S.; Lepage, P.; Seksik, P.; Allez, M.; Tréton, X.; Bouhnik, Y.; Colombel, J.F.; Leclerc, M.; Pochart, P.; Doré, J.; et al. GETAID. Structural robustness of the gut mucosal microbiota is associated with Crohn's disease remission after surgery. Gut 2016, 65, 954–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulet, O.; Abi Nader, E.; Pigneur, B.; Lambe, C. Short Bowel Syndrome as the Leading Cause of Intestinal Failure in Early Life: Some Insights into the Management. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019, 22, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massironi, S.; Cavalcoli, F.; Rausa, E.; Invernizzi, P.; Braga, M.; Vecchi, M. Understanding short bowel syndrome: Current status and future perspectives. Dig Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastl, A.J, Jr.; Terry, N.A.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.G. The Structure and Function of the Human Small Intestinal Microbiota: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 9, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommovilla, J.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, R.C.; Choi, P.M.; Diaz-Miron, J.; Shaikh, N.; Sodergren, E.; Warner, B.B.; Weinstock, G.M.; Tarr, P.I.; et al. Small bowel resection induces long-term changes in the enteric microbiota of mice. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015, 19, 56–64, discussion 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Bando, Y.; Kurihara, H.; Satomi, K.; Nonoyama, K.; Matsuura, N. Fecal microflora in a patient with short-bowel syndrome and identification of dominant lactobacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35, 3181–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleminson, J.S.; Young, G.R.; Campbell, D.I.; Campbell, F.; Gennery, A.R.; Berrington, J.E.; Stewart, C.J. Gut microbiome in paediatric short bowel syndrome: a systematic review and sequencing re-analysis. Pediatr Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Steeg, H.J.J.; Hageman, I.C.; Morandi, A.; Amerstorfer, E.E.; Sloots, C.E.J.; Jenetzky, E.; Stenström, P.; Samuk, I.; Fanjul, M.; Midrio, P.; et al. ARM-Net Consortium. Complications After Surgery for Anorectal Malformations: An ARM-Net consortium Registry Study. J Pediatr Surg. 2025, 60, 162403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilms, M.; Mãrzheuser, S.; Jenetzky, E.; Busse, R.; Nimptsch, U. Treatment of Hirschsprung's Disease in Germany: Analysis of National Hospital Discharge Data From 2016 to 2022. J Pediatr Surg. 2024, 59, 161574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickler, S.W.; Rode, H. Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 829–835. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabaleyan, P.; Kaalby, L.; Deding, U.; Al-Najami, I.; Ellebæk, M.B. Mortality in patients with secondary peritonitis treated by primary closure or vacuum-assisted closure: nationwide register-based cohort study. BJS Open. 2025, 9, zraf118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, B.X. Promoting wound recovery through stable intestinal flora: Reducing post-operative complications in colorectal cancer surgery patients. Int Wound J. 2024 Mar;21(3):e14501. Epub 2023 Dec 4. Retraction in: Int Wound J. 2025, 22, e70472. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, W. The implication of gut microbiota in recovery from gastrointestinal surgery. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnes, A.; Puccioni, C.; D'Ugo, D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Biondi, A.; Persiani, R. The gut microbiota and colorectal surgery outcomes: facts or hype? A narrative review. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigalou, C.; Paraschaki, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Aftzoglou, K.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; Tsakris, Z.; Vradelis, S.; Stavropoulou, E. Alterations of gut microbiome following gastrointestinal surgical procedures and their potential complications. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1191126, Erratum in: Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023, 13,1281527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krezalek, M.A.; Hyoju, S.; Zaborin, A.; Okafor, E.; Chandrasekar, L.; Bindokas, V.; Guyton, K.; Montgomery, C.P.; Daum, R.S.; Zaborina, O.; et al. Can Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Silently Travel From the Gut to the Wound and Cause Postoperative Infection? Modeling the "Trojan Horse Hypothesis. Ann Surg. 2018, 267, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, G.P.; Lee, S.M.; Mazmanian, S.K. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborin, A.; Smith, D.; Garfield, K.; Quensen, J.; Shakhsheer, B.; Kade, M.; Tirrell, M.; Tiedje, J.; Gilbert, J.A.; Zaborina, O.; et al. Membership and behavior of ultra-low-diversity pathogen communities present in the gut of humans during prolonged critical illness. mBio 2014, 5, e01361-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krezalek, M.A.; DeFazio, J.; Zaborina, O.; Zaborin, A.; Alverdy, J.C. The Shift of an Intestinal "Microbiome" to a "Pathobiome" Governs the Course and Outcome of Sepsis Following Surgical Injury. Shock. 2016, 45, 475–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P. The microbiome and critical illness. Lancet Respir Med. 2016, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogi, S.; Banerjee, A.; Panda, S.S.; Ratan, S.K.; Narang, R. Laparoscopic versus open appendicectomy for complicated appendicitis in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2022, 57, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Lv, Y.; Chen, K. Laparoscopic versus open repair of congenital duodenal obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022, 38, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venara, A.; Neunlist, M.; Slim, K.; Barbieux, J.; Colas, P.A.; Hamy, A.; Meurette, G. Postoperative ileus: Pathophysiology, incidence, and prevention. J Visc Surg. 2016, 153, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alverdy, J.C.; Hyoju, S.K.; Weigerinck, M.; Gilbert, J.A. The gut microbiome and the mechanism of surgical infection. Br J Surg. 2017, 104, e14–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehane, A.; Perez, M.; Smith, C.; Tian, Y.; Holl, J.L.; Raval, M.V. Slow Down Fluids to Speed Up the Intestine - Exploring Postoperative Ileus in Pediatric Gastrointestinal Surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 2025, 60, 162153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Geng, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Jin, X.; Zhao, F.; Feng, J.; Wei, Y. Prediction of Postoperative Ileus in Patients With Colorectal Cancer by Preoperative Gut Microbiota. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 526009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A.; Rogers, M.B.; Firek, B.; Neal, M.D.; Zuckerbraun, B.S.; Morowitz, M.J. Dysbiosis Across Multiple Body Sites in Critically Ill Adult Surgical Patients. Shock. 2016, 46, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, S.; Martín, R.; Bridonneau, C.; Robert, V.; Sokol, H.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Thomas, M.; Langella, P. Ecology and metabolism of the beneficial intestinal commensal bacterium Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 146–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzosek, L.; Miquel, S.; Noordine, M.L.; Bouet, S.; Joncquel Chevalier-Curt, M.; Robert, V.; Philippe, C.; Bridonneau, C.; Cherbuy, C.; Robbe-Masselot, C.; et al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Faecalibacteriumprausnitzii influence the production of mucus glycans and the development of goblet cells in the colonic epithelium of a gnotobiotic model rodent. BMC Biol. 2013, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türler, A.; Schwarz, N.T.; Türler, E.; Kalff, J.C.; Bauer, A.J. MCP-1 causes leukocyte recruitment and subsequently endotoxemic ileus in rat. Am J PhysiolGastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002, 282, G145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, A.B.; Jonsson, I.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Brandstrup, B. Collagenase-producing bacteria are common in anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023, 38, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershuni, V.M.; Friedman, E.S. The Microbiome-Host Interaction as a Potential Driver of Anastomotic Leak. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, V.E.; Castro, P.A.S.V.; Padilha, H.T.; Pillar, L.V.; Godinho, L.B.R.; Tinoco, A.C.A.; Amil, R.D.C.; Soares, A.N.; Cruz, G.M.G.D.; BezerraJMT; et al. Preoperative risk factors associated with anastomotic leakage after colectomy for colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2022, 49, e20223363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Gauda, E.B.; Chiu, P.P.L.; Moore, A.M. Risk factors for prolonged mechanical ventilation in neonates following gastrointestinal surgery. TranslPediatr 2022, 11, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.O.; Nwomeh, B.C. Complications in children with ulcerative colitis undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2017, 26, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Wei, Y. New understanding of gut microbiota and colorectal anastomosis leak: A collaborative review of the current concepts. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1022603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Bothin, C.; Kanazawa, K.; Midtvedt, T. Experimental study of the influence of intestinal flora on the healing of intestinal anastomoses. Br J Surg. 1999, 86, 961–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christley, S.; Shogan, B.; Levine, Z.; Koo, H.; Guyton, K.; Owens, S.; Gilbert, J.; Zaborina, O.; Alverdy, J.C. Comparative genetics of Enterococcus faecalis intestinal tissue isolates before and after surgery in a rat model of colon anastomosis. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0232165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano, D.; Ivulic, D.; Viver, T.; Morales, F.; López-Kostner, F.; Vidal, R.M. Microbiota Phenotype Promotes Anastomotic Leakage in a Model of Rats with Ischemic Colon Resection. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boatman, S.; Kaiser, T.; Nalluri-Butz, H.; Khan, M.H.; Dietz, M.; Kohn, J.; Johnson, A.J.; Gaertner, W.B.; Staley, C.; Jahansouz, C. Diet-induced shifts in the gut microbiota influence anastomotic healing in a murine model of colonic surgery. Gut Microbes. 2023, 15, 2283147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Praagh, J.B.; de Goffau, M.C.; Bakker, I.S.; van Goor, H.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Olinga, P.; Havenga, K. Mucus Microbiome of Anastomotic Tissue During Surgery Has Predictive Value for Colorectal Anastomotic Leakage. Ann Surg. 2019, 269, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianos, G.D.; Frountzas, M.; Kyrochristou, I.D.; Sakarellos, P.; Tatsis, V.; Kyrochristou, G.D.; Bali, C.D.; Gazouli, M.; Mitsis, M.; Schizas, D. What Is the Role of the Gut Microbiota in Anastomotic Leakage After Colorectal Resection? A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Studies. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komen, N.; Slieker, J.; Willemsen, P.; Mannaerts, G.; Pattyn, P.; Karsten, T.; de Wilt, H.; van der Harst, E.; van Leeuwen, W.; Decaestecker, C.; et al. Polymerase chain reaction for Enterococcus faecalis in drain fluid: the first screening test for symptomatic colorectal anastomotic leakage. The Appeal-study: analysis of parameters predictive for evident anastomotic leakage. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmisano, S.; Campisciano, G.; Iacuzzo, C.; Bonadio, L.; Zucca, A.; Cosola, D.; Comar, M.; de Manzini, N. Role of preoperative gut microbiota on colorectal anastomotic leakage: preliminary results. Updates Surg. 2020, 72, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mima, K.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kosumi, K.; Ogata, Y.; Miyake, K.; Hiyoshi, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Baba, Y.; Iwagami, S.; et al. Mucosal cancer-associated microbes and anastomotic leakage after resection of colorectal carcinoma. Surg Oncol. 2020, 32, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, R.; Gonzalez, E.; Fragoso, G.; Oliero, M.; Alaoui, A.A.; Calvé, A.; VenninRendos, H.; Djediai, S.; Cuisiniere, T.; Laplante, P.; et al. Gut microbiota influence anastomotic healing in colorectal cancer surgery through modulation of mucosal proinflammatory cytokines. Gut. 2023, 72, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegerinck, M.; Hyoju, S.K.; Mao, J.; Zaborin, A.; Adriaansens, C.; Salzman, E.; Hyman, N.H.; Zaborina, O.; van Goor, H.; Alverdy, J.C. Novel de novo synthesized phosphate carrier compound ABA-PEG20k-Pi20 suppresses collagenase production in Enterococcus faecalis and prevents colonic anastomotic leak in an experimental model. Br J Surg. 2018, 105, 1368–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusela, P. Fibronectin binds to Staphylococcus aureus. Nature 1978, 276(5689), 718–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Fleury, C.; Jalalvand, F.; Riesbeck, K. Human pathogens utilize host extracellular matrix proteins laminin and collagen for adhesion and invasion of the host. FEMSMicrobiol Rev. 2012, 36, 1122–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildeboer, A.C.L.; van Helsdingen, C.P.M.; Gallé, C.G.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Derikx, J.P.M.; Bouvy, N.D. Enhancing intestinal anastomotic healing using butyrate: Systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental animal studies. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0286716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghighi, F.; Salami, M. What we need to know about the germ-free animal models. AIMS Microbiol. 2024, 10, 107–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, R.J.; Hunt, M.R.; Scull, B.P.; Simmons, J.G.; Speck, K.E.; Helmrath, M.A.; Lund, P.K. A new animal model of postsurgical bowel inflammation and fibrosis: the effect of commensal microflora. Gut 2009, 58, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyoju, S.; Machutta, K.; Krezalek, M.A.; Alverdy, J.C. What Is the Role of the Gut in Wound Infections? Adv Surg. 2023, 57, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, J.; Dziki, Ł.; Harmon, J.; Fichna, J. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the prehabilitation before colorectal surgery. CurrProbl Surg. 2025, 69, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskey, R.; Papazian, E.; Lam, A.; Toni, T.; Hyoju, S.; Thewissen, R.; Zaborin, A.; Zaborina, O.; Alverdy, JC. Defining Microbiome Readiness for Surgery: Dietary Prehabilitation and Stool Biomarkers as Predictive Tools to Improve Outcome. Ann Surg. 2022, 276, e361–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avis, T.; Wilson, F.X.; Khan, N.; Mason, C.S.; Powell, D.J. Targeted microbiome-sparing antibiotics. Drug Discov Today 2021, 26, 2198–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, K.A.; Ulrich, R.J.; Vasan, A.K.; Sinclair, M.; Wen, P.C.; Holmes, J.R.; Lee, H.Y.; Hung, C.C.; Fields, C.J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; et al. A Gram-negative-selective antibiotic that spares the gut microbiome. Nature. 2024, 630, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, H.; Hong, L.; Feng, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Shi, C.; Wu, W.; Gao, R.; et al. The effect of perioperative probiotics treatment for colorectal cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Oncotarget. 2016, 7, 8432–8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N.I.; Herrera Giron, C.G.; Arragan Lezama, C.A.; Frias Redroban, S.J.; Ventura Herrera, M.O.; SanicCoj, G.A. Timing and Protocols for Microbiome Intervention in Surgical Patients: A Literature Review of Current Evidence. Cureus 2025, 17, e86104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Han, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yang, L. Postoperative Probiotics Administration Attenuates Gastrointestinal Complications and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Caused by Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamori, Y; Sugiyama, M; Hashizume, K; Yuki, N; Morotomi, M; Tanaka, R. Experience of long-term synbiotic therapy in seven short bowel patients with refractory enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2004, 39, 1686–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K.; Takahashi, T.; Inoue, M.; Morotomi, M.; Otake, K.; Nakazawa, M.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Miki, C.; Kusunoki, M. Immunonutritional effects during synbiotics therapy in pediatric patients with short bowel syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007, 23, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Esvaran, M.; Chen, L.; Keil, A.D.; Gollow, I.; Simmer, K.; Wemheuer, B.; Conway, P.; Patole, S. Probiotic supplementation in neonates with congenital gastrointestinal surgical conditions: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Pediatr Res. 2022, 92, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.L.; Sun, Y.; Dong, X.; Ren, Z.; Li, B.; Yang, P.; et al. Infant feces-derived Lactobacillus gasseriFWJL-4 mitigates experimental necrotizing enterocolitis via acetate production. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2430541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, R.; Sagawa, M.; Sano, A.; Sakai, M.; Hiraoka, S.I.; Tabei, I.; et al. Impact of Perioperative Immunonutrition on Postoperative Outcomes for Patients Undergoing Head and Neck or Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgeries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg. 2024, 279, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhotnik, I.; Levi, R.; Moran-Lev, H. Impact of Dietary Protein on the Management of Pediatric Short Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, W.K.; Al Ali, A. The Gut Microbiome Advances Precision Medicine and Diagnostics for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 11259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Gan, G.; Cheng, J.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, G.; Liu, S.; Hu, J. Engineered Probiotics Enable Targeted Gut Delivery of Dual Gasotransmitters for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2025, 64, e202502588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y. Phage therapy as a revitalized weapon for treating clinical diseases. Microbiome Res Rep. 2025, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors (year) |

Type of study | Disease | Gut alterations | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lin et al. (2023) |

Prospective case control |

NEC |

↓ Alpha-diversity after full enteral nutrition. ↑ Methylobacterium, Clostridiumbutyricum, Acidobacteria. |

Enriched Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas; depleted Bacteroidales, Ruminococcaceae |

[10] |

|

Neuvonen et al. (2018) |

Prospective observational |

HD |

Enriched Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas; depleted Bacteroidales, Ruminococcaceae |

Baseline dysbiosis persists post-surgery, defining a state of ecological failure. |

[11] |

|

Pini Prato et al. (2019) |

Retrospective |

HD |

↓ Alpha diversity and altered beta diversity in total colonic aganglionosisvs rectosigmoid. |

The extent of aganglionosis directly shapes the GM ecosystem. |

[124] |

| Yan et al. (2014) | Cross -sectional | HAEC | Proteobacteria-dominated GM | Bacteroides-rich community in stable patients. | [91] |

|

Frykman et al. (2015) |

Cross-sectional |

HAEC |

Separate fungal dysbiosis: loss of diversity, bloom of Candida |

HAEC involves a disruption of both bacterial and fungal communities |

[126] |

|

Murphy et al. (2025) |

Prospective observational |

HD |

Absence of healthy developmental trajectory: No increase in alpha diversity with age vs healthy controls ↑Fusobacteria linkedtoinflammation. |

Disrupted GM maturation is linked to persistent GI inflammation and symptoms post-pull-through |

[123] |

|

Davidocs et al. (2016) |

Prospective observational |

SΒS |

↑ Escherichia coli/Shigella ↑ Streptococcus Relative abundance of Lactobacillus noted in patients with diarrhea. |

Associated with D-lactic acidosis due to high D-lactate production, leading to metabolic acidosis. |

[102] |

|

Cleminson et al. (2025) |

Systematic review | SBS |

Depletion of beneficial SCFA-producers: ↓ Dorea, ↓ Ruminococcus, ↓ Blautia (genera from Lachnospiraceae family) in children on TPN. |

Deficit of protective microbial metabolites, exacerbating mucosal inflammation. Likely driven by antibiotics and bacterial overgrowth. |

[141] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).