Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Phase Noise and Its Characterization

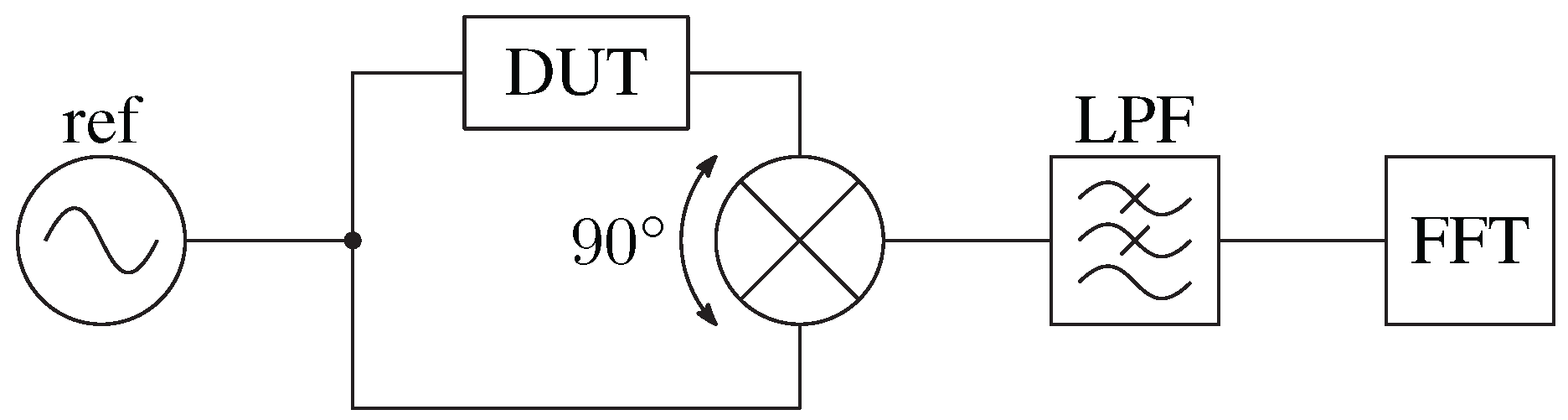

2.1. Measurement Methods

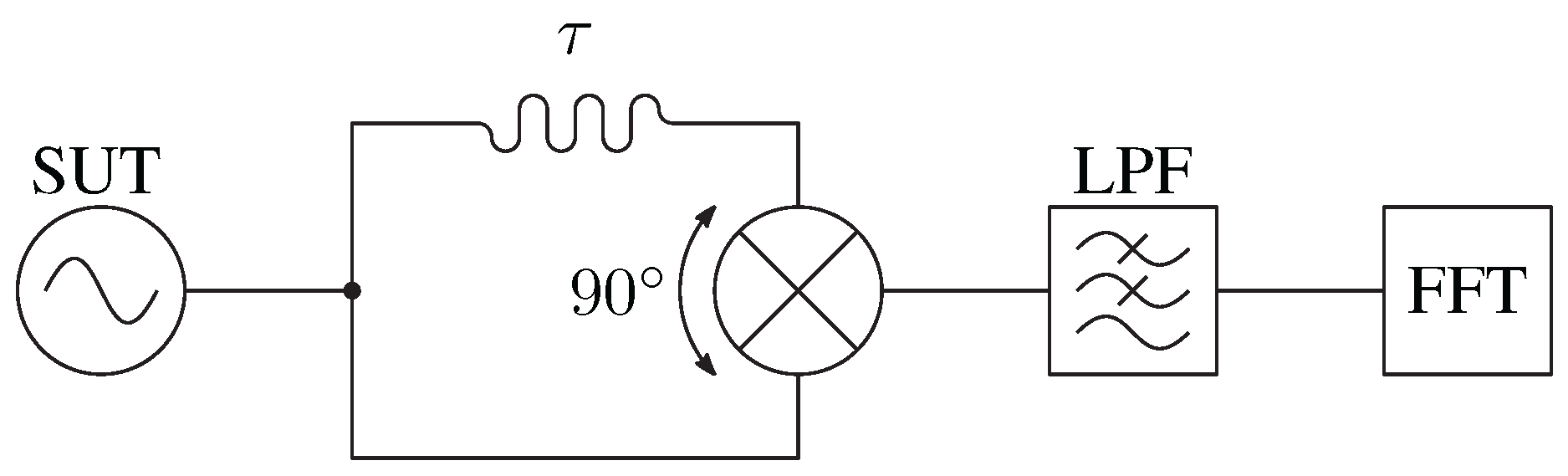

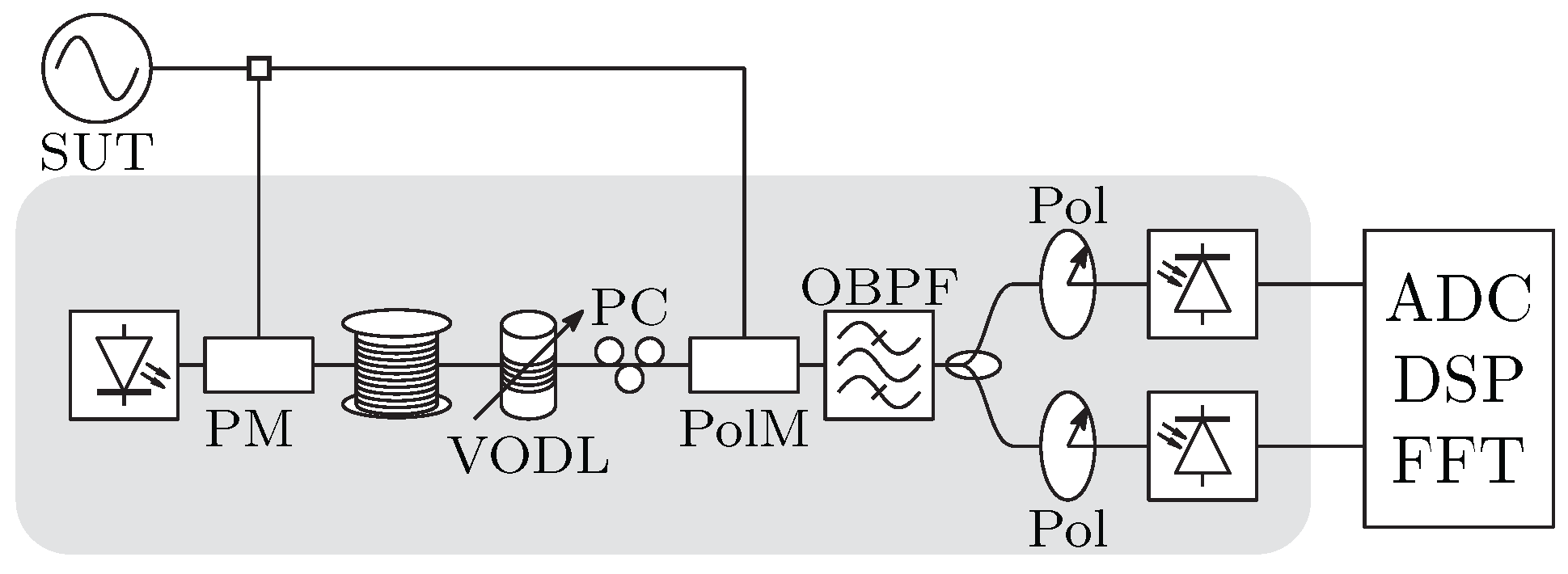

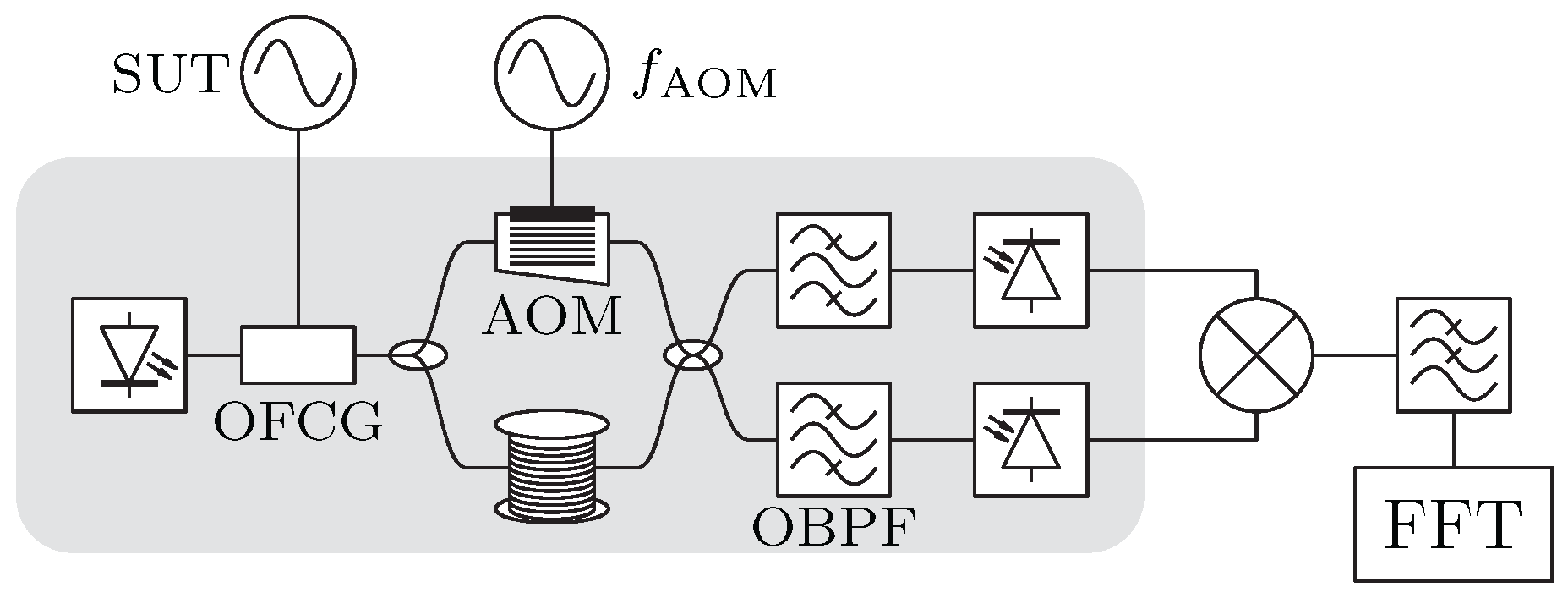

3. Fiber-Optic Delay-Line Method

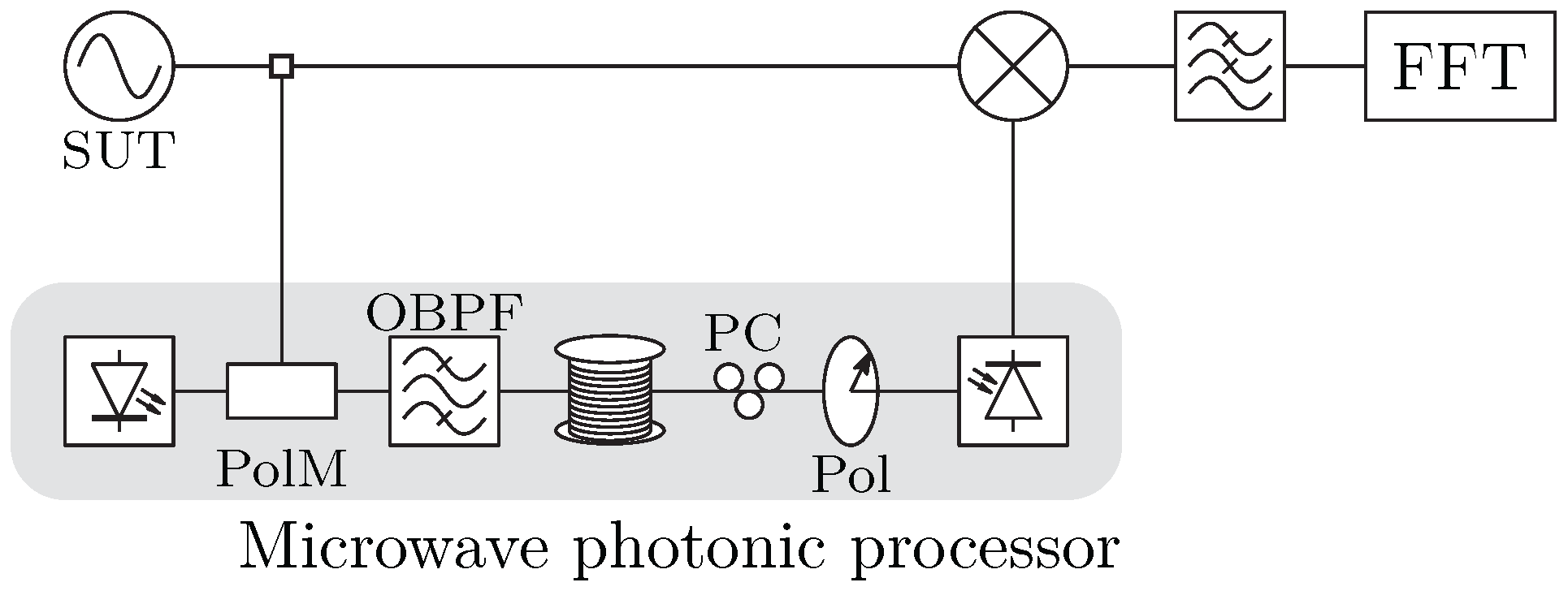

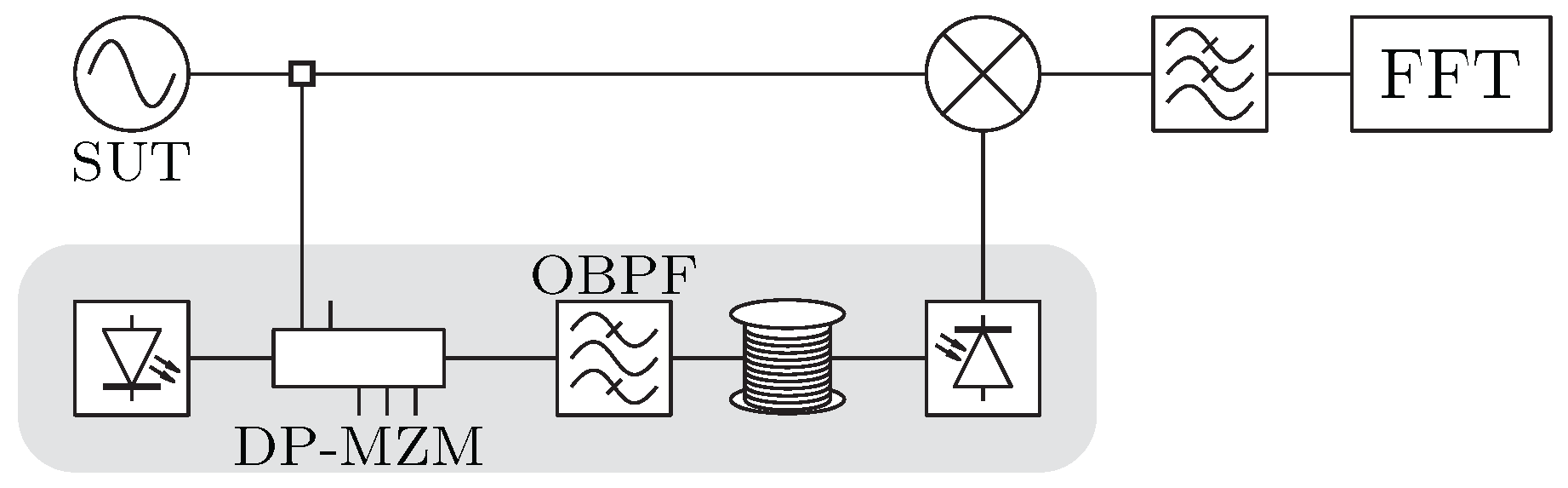

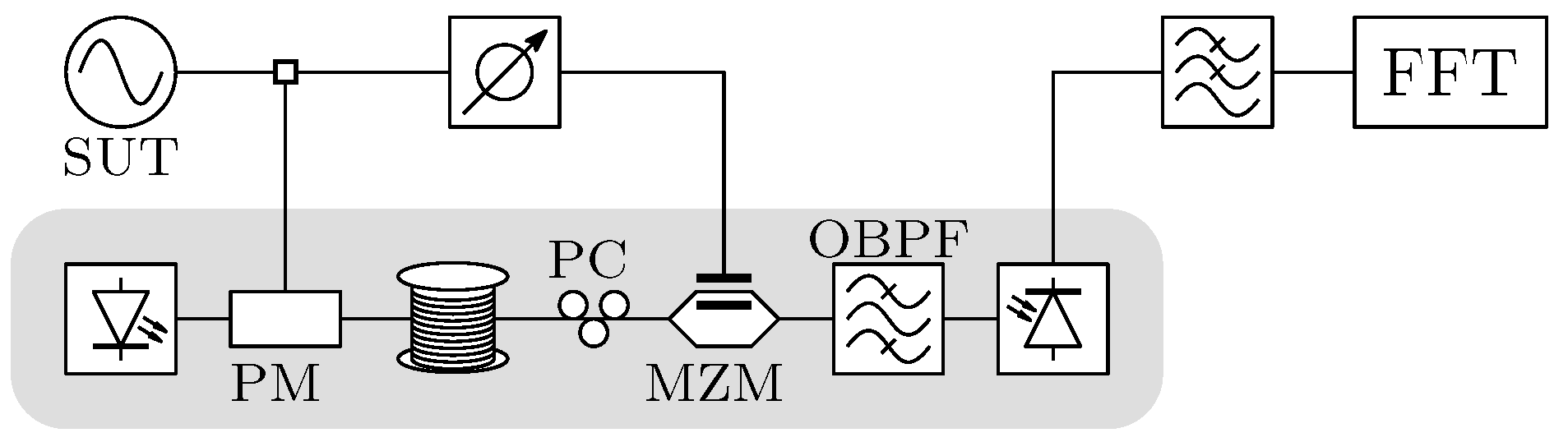

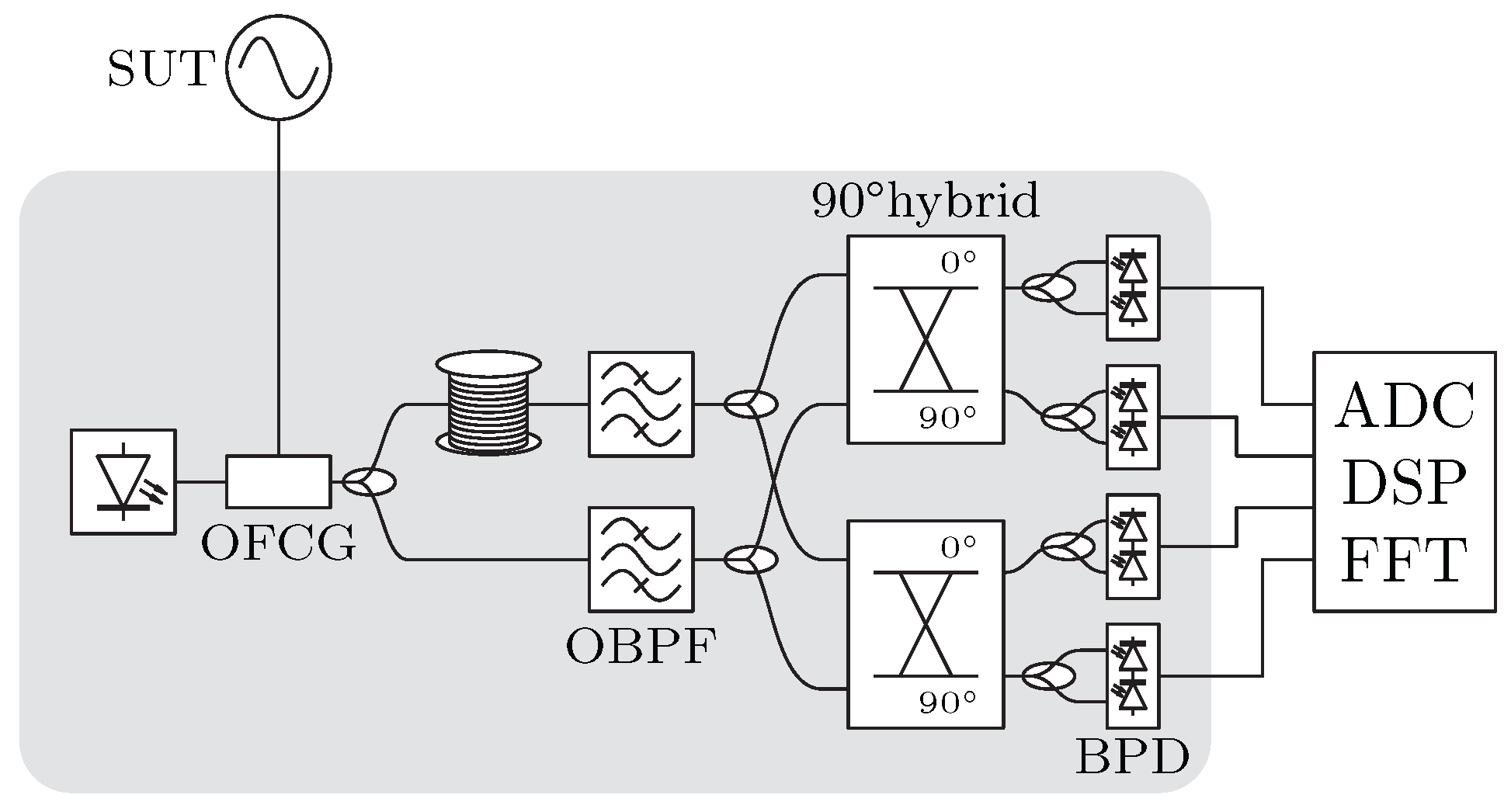

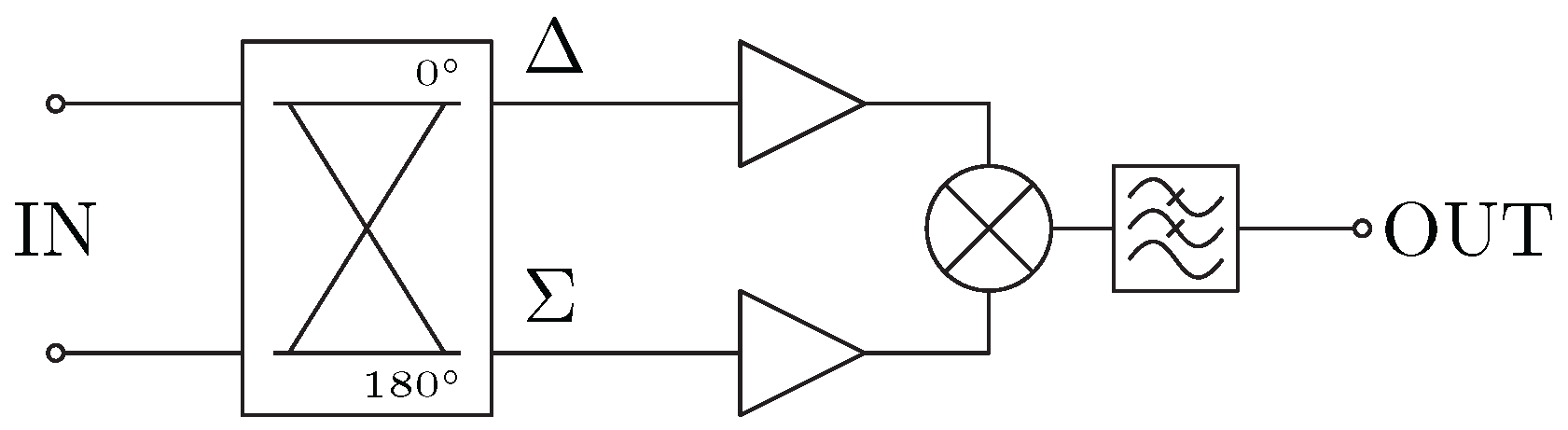

3.1. Photonic Processing

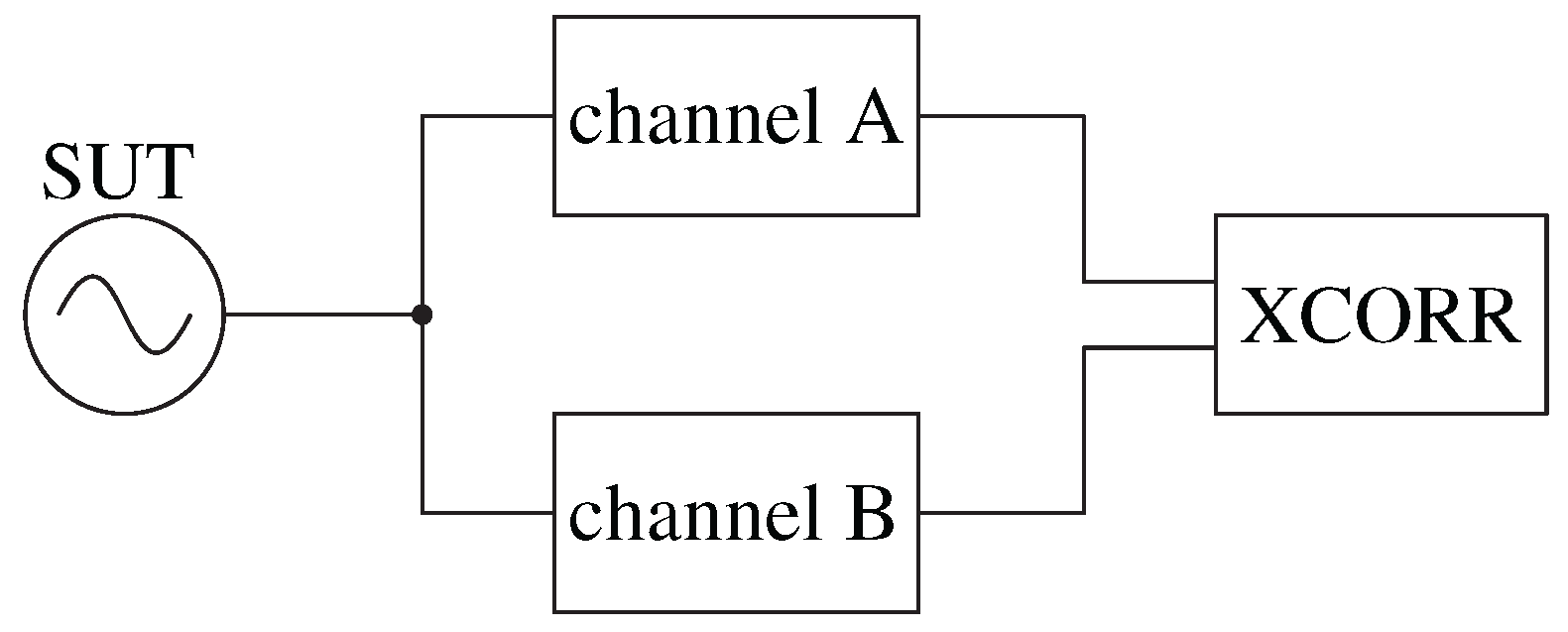

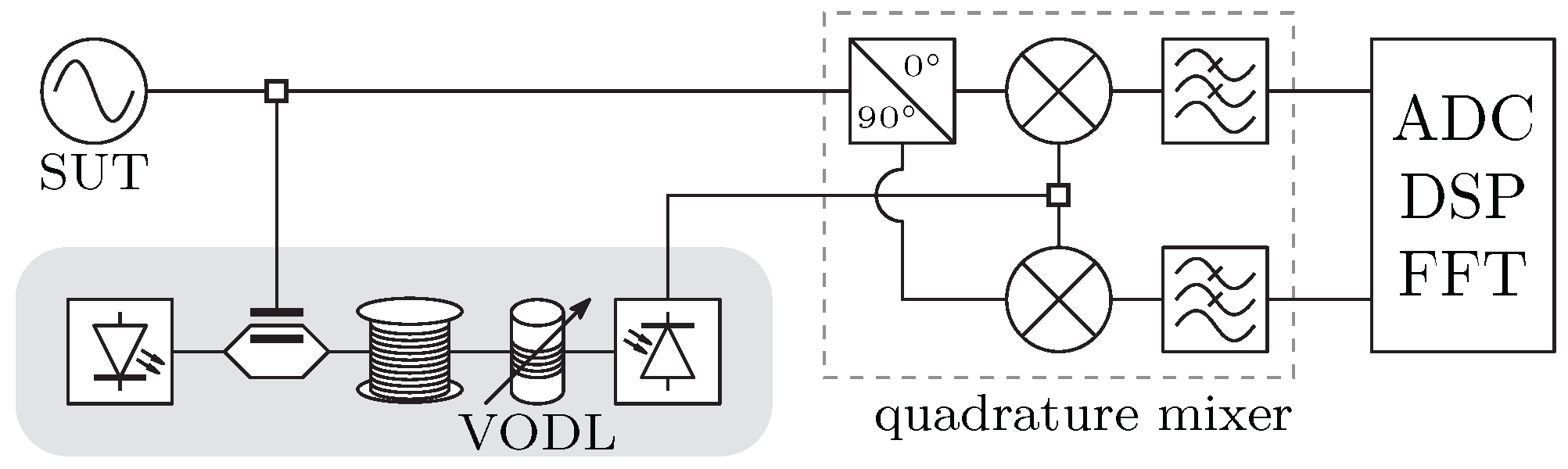

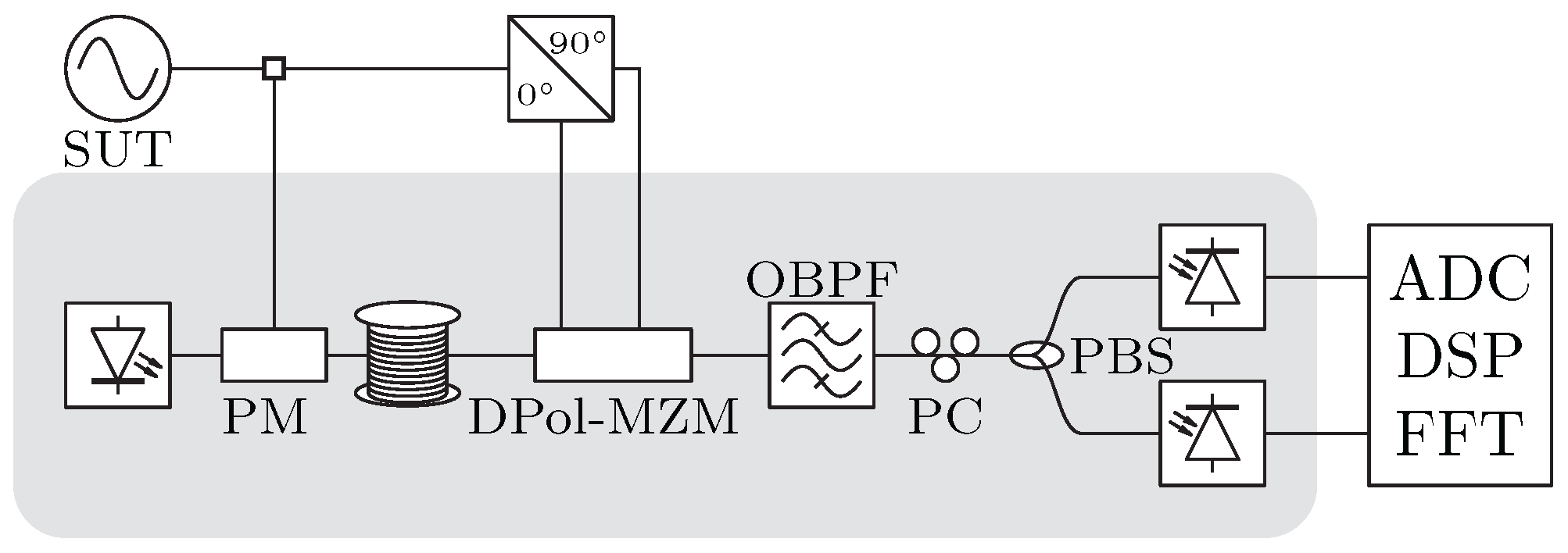

3.2. Sensitivity Improvements

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hilt, A. Throughput Estimation of K-zone Gbps Radio Links Operating in the E-band. In Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials; Drustvo MIDEM, 2022; Volume 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, D.B.; Johnson, G.F. Short-term stability for a Doppler radar: Requirements, measurements, and techniques. In Proceedings of the IEEE; Publisher; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 1966; Volume 54, pp. 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podbregar, L.; Batagelj, B.; Blatnik, A.; Lavrič, A. Advances in and Applications of Microwave Photonics in Radar Systems: A Review. Photonics 2025, 12, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Chen, A.Y.K. Low-Phase-Noise and Low-Jitter Signal Generation Techniques for 5G/6G and Quantum Computing Applications. IEEE Microwave Magazine 2025, 26, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Xue, K.; Long, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Simulation of Heterodyne Signal for Science Interferometers of Space-Borne Gravitational Wave Detector and Evaluation of Phase Measurement Noise. Photonics 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratnik, J.; Lemut, P.; Vidmar, M. Time-transfer and synchronization equipment for high-performance particle accelerators. Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials 2012, 42, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Su, X.; Yu, J.; Luo, H.; Gao, Y.; Han, X.; Huang, C. A Distributed Microwave Signal Transmission System for Arbitrary Multi-Node Download. Photonics 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidmar, M. Extending Leeson’s Equation. In Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials; Drustvo MIDEM, 2021; Volume 51, pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.S.; Maleki, L. Optoelectronic microwave oscillator. In Journal of the Optical Society of America B; Optica Publishing Group, 1996; Volume 13, p. 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidmar, M. Optical-fiber Communications: Components and Systems. Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials 2001, 31, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Batagelj, B.; Pavlovič, L.; Naglič, L.; Tomažič, S. Convergence of fixed and mobile networks by radio over fibre technology. Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials 2011, 41, 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.; Lu, B.; Pan, W.; Yan, L.; Stöhr, A.; Yao, J. Photonics for microwave measurements. In Laser & Photonics Reviews; Wiley, 2016; Volume 10, pp. 711–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Yao, J. Photonics-Based Broadband Microwave Measurement. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2017; Volume 35, pp. 3498–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tu, B.; Wang, Y. Photonics-Enabled High-Sensitivity and Wide-Bandwidth Microwave Phase Noise Analyzers. In Photonics; MDPI AG, 2025; Volume 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, D.B. Oscillator Phase Noise: A 50-Year Review. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2016, 63, 1208–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, E. Phase noise and frequency stability in oscillators; The Cambridge RF and microwave engineering series; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, E.; Vernotte, F. The Companion of Enrico’s Chart for Phase Noise and Two-Sample Variances. In IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2023; Volume 71, pp. 2996–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1139-2022 - IEEE Standard Definitions of Physical Quantities for Fundamental Frequency and Time Metrology–Random Instabilities - Redline. IEEE, 2022. [PubMed Central]

- Rohde, U.L.; Poddar, A.K.; Apte, A.M. Getting Its Measure: Oscillator Phase Noise Measurement Techniques and Limitations. In IEEE Microwave Magazine; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2013; Volume 14, pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.A.; Chi, A.R.; Cutler, L.S.; Healey, D.J.; Leeson, D.B.; McGunigal, T.E.; Mullen, J.A.; Smith, W.L.; Sydnor, R.L.; Vessot, R.F.C.; et al. Characterization of Frequency Stability. In IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 1971; Volume IM-20, pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, A.L.; Seal, W.D.; Labaar, F. Phase noise and AM noise measurements in the frequency domain. Infrared and Millimeter Waves 1984, 11, 239–289. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Xu, Y.; Guo, R.; Du, H.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z. High sensitivity microwave phase noise analyzer based on a phase locked optoelectronic oscillator. In Optics Express; Optica Publishing Group, 2019; Volume 27, p. 18910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase Noise Characterization: Frequency Discriminator Method: Product Note 11729C-2. 1985.

- Rubiola, E.; Vernotte, F. The cross-spectrum experimental method. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, E.; Giordano, V.; Groslambert, J. Very high frequency and microwave interferometric phase and amplitude noise measurements. Review of Scientific Instruments 1999, 70, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, E.; Giordano, V. Advanced interferometric phase and amplitude noise measurements. Review of Scientific Instruments 2002, 73, 2445–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudot, R.; Rubiola, E. Phase noise in RF and microwave amplifiers. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control 2012, 59, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssieux, D.; Callejo, M.; Millo, J.; Rubiola, E.; Boudot, R. Phase noise measurement of optical amplifiers. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisani, L.; D’Apuzzo, M.; D’Arco, M. A digital signal-processing approach for phase noise measurement. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2001, 50, 930–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisani, L.; Schiano Lo Moriello, R.; D’Arco, M.; Greenhall, C. A Digital Signal Processing Instrument for Real-Time Phase Noise Measurement. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2008, 57, 2098–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, P.; Mathis, H.; Kucera, J.; Dahinden, S. Implementation of a Cross-Spectrum FFT Analyzer for a Phase-Noise Test System in a Low-Cost FPGA. International Journal of Microwave Science and Technology 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visme, P.; Imbaud, J.; Holme, A.; Sthal, F. Comparison of an Affordable Open-Source Phase Noise Analyzer With Its Commercial Counterpart. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomponio, M.; Hati, A.; Nelson, C. Direct Digital Simultaneous Phase-Amplitude Noise and Allan Deviation Measurement System. IEEE Open Journal of Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 2024, 4, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Zhao, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, T.; Qi, Y.; Ding, J.; Yan, B.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Laser Linewidth Measurement Using an FPGA-Based Delay Self-Homodyne System. Photonics 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibar, D.; Chin, H.M.; Tong, Y.; Jain, N.; Guo, J.; Chang, L.; Gehring, T.; Bowers, J.E.; Andersen, U.L. Highly-Sensitive Phase and Frequency Noise Measurement Technique Using Bayesian Filtering. In IEEE Photonics Technology Letters; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2019; Volume 31, pp. 1866–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertenskötter, L.; Kantner, M. Frequency Noise Characterization of Narrow-Linewidth Semiconductor Lasers: A Bayesian Approach. IEEE Photonics Journal 2024, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebesehl, J.; Nak, D.C.; Zibar, D. Interference fringe mitigation in short-delay self-heterodyne laser phase noise measurements. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 43718–43731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilgaz, M.A.; Batagelj, B. Opto-Electronic Oscillators for Micro- and Millimeter Wave Signal Generation. Electronics 2021, 10, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Peng, J.; Yan, J. Optoelectronic Oscillators: Progress from Classical Designs to Integrated Systems. Photonics 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, D.; Song, H.; Guo, F.; Zhao, L. Frequency Stabilization of Wideband-Tunable Low-Phase-Noise Optoelectronic Oscillator Based on Fundamental and Subharmonic RF Injection Locking. Photonics 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, E.; Salik, E.; Huang, S.; Yu, N.; Maleki, L. Photonic-delay technique for phase-noise measurement of microwave oscillators. In Journal of the Optical Society of America B; Optica Publishing Group, 2005; Volume 22, p. 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onillon, B.; Constant, S.; Llopis, O. Optical links for ultra low phase noise microwave oscillators measurement. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium and Exposition, 2005, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2005; pp. 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Song, Z.; Li, N. A Compact Photonic-delay Line Phase Noise Measurement System Based on an Electro-absorption Modulated Laser. In Proceedings of the 2021 Photonics & Electromagnetics Research Symposium (PIERS), Hangzhou, China, 2021; pp. 801–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyssieux, D.; Millo, J.; Rubiola, E.; Boudot, R. Phase noise of a microwave photonic channel: direct-current versus external electro-optic modulation. In Journal of the Optical Society of America B; Optica Publishing Group, 2024; Volume 41, p. 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrič, A.; Batagelj, B.; Vidmar, M. Calibration of an RF/Microwave Phase Noise Meter with a Photonic Delay Line. In Photonics; Publisher; MDPI AG, 2022; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanser, K. Fundamental phase noise limit in optical fibres due to temperature fluctuations. Electronics Letters 1992, 28, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Okubo, S.; Kashiwagi, K.; Hong, F.L.; Hosaka, K.; Inaba, H. Evaluation of Fiber Noise Induced in Ultrastable Environments. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2019, 68, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Feng, Z.; Marpaung, D.; Zhang, X.; Komanec, M.; Suslov, D.; Dousek, D.; Zvanovec, S.; Fokoua, E.R.N.; Bradley, T.D.; et al. Optical Fiber Delay Lines in Microwave Photonics: Sensitivity to Temperature and Means to Reduce it. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Publisher; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2021; Volume 39, pp. 2311–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, B.; Pratap, R.; Ramachandran, H.; Venkitesh, D. Impact of Fiber Transport on Phase Noise in mmWave Band and Beyond. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2025, 73, 4074–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, P.; Zhu, D.; Pan, S. Wideband Phase Noise Measurement Using a Multifunctional Microwave Photonic Processor. In IEEE Photonics Technology Letters; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2014; Volume 26, pp. 2434–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, B.; Ban, D.; Jin, Y.; Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, N. High Precision Phase Noise Analysis Based on a Photonic-Assisted Microwave Phase Shifter Without Nonlinear Phase Distortion. In IEEE Photonics Journal; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2023; Volume 15, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.G.; Mei, H.; Sun, W.; Zhu, N. Photonic-Assisted Wideband Phase Noise Analyzer Based on Optoelectronic Hybrid Units. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2016; Volume 34, pp. 3425–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrič, A.; Batagelj, B.; Vidmar, M. Slovenia SI 26215 A; Postopek merjenja faznega šuma in naprava za izvedbo postopka. 2022.

- Gliese, U.; Norskov, S.; Nielsen, T. Chromatic dispersion in fiber-optic microwave and millimeter-wave links. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 1996, 44, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner-Nielsen, L.; Wandel, M.; Kristensen, P.; Jorgensen, C.; Jorgensen, L.; Edvold, B.; Palsdottir, B.; Jakobsen, D. Dispersion-compensating fibers. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Publisher; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2005; Volume 23, pp. 3566–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpagarajesh, G.; Blessie, A.; Krishnan, S. Performance Assessment of Dispersion Compensation Using Fiber Bragg Grating and Dispersion Compensation Fiber Technique. In Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials; Drustvo MIDEM, 2021; Volume 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy, K.; Poornachari, P.; Madhan, M.G. Performance Analysis of Dispersion Compensation Schemes with Delay Line Filter. In Informacije MIDEM - Journal of Microelectronics, Electronic Components and Materials; Drustvo MIDEM, 2021; Volume 50, pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrič, A.; Vidmar, M.; Batagelj, B. Dispersion-Compensation-Fiber-Enabled Photonic-Delay Phase-Noise Measurement. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics (MWP), Pisa, Italy, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrič, A.; Vidmar, M.; Batagelj, B. Dual-Fiber Wavelength-Tuned Photonic-Delay Phase-Noise Measurement. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, P.; Pan, S. Phase noise measurement of wideband microwave sources based on a microwave photonic frequency down-converter. In Optics Letters; Optica Publishing Group, 2015; Volume 40, p. 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, D.; Pan, S. Photonic-assisted wideband phase noise measurement of microwave signal sources. Electronics Letters 2015, 51, 1272–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Li, N. Wideband Microwave Phase Noise Analyzer Based on All-Optical Microwave Signal Processing. In IEEE Photonics Journal; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2022; Volume 14, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheidi, H.; Banai, A. Phase-Noise Measurement of Microwave Oscillators Using Phase-Shifterless Delay-Line Discriminator. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2010, 58, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, F.; Pan, S. Phase Noise Measurement of RF Signals by Photonic Time Delay and Digital Phase Demodulation. In IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2018; Volume 66, pp. 4306–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, J.; Pan, S. Wideband microwave phase noise measurement based on photonic-assisted I/Q mixing and digital phase demodulation. In Optics Express; Optica Publishing Group, 2017; Volume 25, p. 22760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, F.; Ben, D.; Pan, S. Wideband Microwave Phase Noise Analyzer Based on an All-Optical Microwave I/Q Mixer. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2018; Volume 36, pp. 4319–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Yin, L. Photonic-delay homodyne technology for low-phase noise measurement. Optik 2014, 125, 1868–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salik; Yu, E.; Nan; Maleki, L.; Rubiola, E. Dual photonic-delay line cross correlation method for phase noise measurement. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium and Exposition, 2004, Montreal, Canada, 2004; pp. 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volyanskiy, K.; Cussey, J.; Tavernier, H.; Salzenstein, P.; Sauvage, G.; Larger, L.; Rubiola, E. Applications of the optical fiber to the generation and measurement of low-phase-noise microwave signals. Journal of the Optical Society of America B 2008, 25, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliyahu, D.; Seidel, D.; Maleki, L. Phase noise of a high performance OEO and an ultra low noise floor cross-correlation microwave photonic homodyne system. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium, Honolulu, HI, 2008; pp. 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Liu, A.m.; Guo, J. Study on low-phase-noise optoelectronic oscillator and high-sensitivity phase noise measurement system. Journal of the Optical Society of America A 2013, 30, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Su, J.; Zhang, T.; Lin, Y. Phase noise measurement of an optoelectronic oscillator based on the photonic-delay line cross-correlation method. In Optics Letters; Optica Publishing Group, 2019; Volume 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, M.; Rauf, B.; Sperling, J.; Afrem, S.; Wendler, W.; Roth, A.; Kornprobst, J.; Peschl, S.; Schulz, J.; Schorer, J.; et al. Cross-Spectrum Phase Noise Measurements of Ultrastable Photonic Microwave Oscillators. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Su, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, N. Photonic-Delay Line Cross Correlation Method Based on DWDM for Phase Noise Measurement. In IEEE Photonics Journal; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2018; Volume 10, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzenstein, P.; Pavlyuchenko, E.; Hmima, A.; Cholley, N.; Zarubin, M.; Galliou, S.; Chembo, Y.K.; Larger, L. Estimation of the uncertainty for a phase noise optoelectronic metrology system. Physica Scripta 2012, T149, 014025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzenstein, P.; Pavlyuchenko, E. Uncertainty Evaluation on a 10.52 GHz (5 dBm) Optoelectronic Oscillator Phase Noise Performance. Micromachines 2021, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuse, N.; Fermann, M.E. Electro-optic comb based real time ultra-high sensitivity phase noise measurement system for high frequency microwaves. In Scientific Reports; Springer Science and Business Media LLC, 2017; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.N.; Nguyen, L.; Barry, L.P. Delayed Self-Heterodyne Phase Noise Measurements With Coherent Phase Modulation Detection. In IEEE Photonics Technology Letters; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2012; Volume 24, pp. 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duill, S.P.O.; Barry, L.P. Simplified Laser Frequency Noise Measurement Using the Delayed Self-Heterodyne Method. Photonics 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ben, D.; Sun, L.; Pan, S. Self-calibrating and high-sensitivity microwave phase noise analyzer applying an optical frequency comb generator and an optical-hybrid-based I/Q detector. In Optics Letters; Optica Publishing Group, 2018; Volume 43, p. 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiola, E.; Salik, E.; Yu, N.; Maleki, L. Phase noise measurements of low power signals. Electronics Letters 2003, 39, 1389–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, X.; Hao, P.; Feng, T.; Chen, X.; Chong, Y. Ultra-Low Phase Noise Measurement of Microwave Sources Using Carrier Suppression Enabled by a Photonic Delay Line. In Journal of Lightwave Technology; Publisher; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2021; Volume 39, pp. 7028–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi Barzegar, A.; Banai, A.; Farzaneh, F. Sensitivity Improvement of Phase-Noise Measurement of Microwave Oscillators Using IF Delay Line Based Discriminator. IEEE Microwave and Wireless Components Letters 2016, 26, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Li, N.; Pan, S. Microwave Phase Noise Analyzer Based on Photonic Delay-Matched Frequency Translation. In IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 2024; Volume 72, pp. 5498–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschapek, P.; Korner, G.; Carlowitz, C.; Vossiek, M. Detailed Analysis and Modeling of Phase Noise and Systematic Phase Distortions in FMCW Radar Systems. IEEE Journal of Microwaves 2022, 2, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Steve Yao, X. Transforming a Noisy RF Oscillator Into an Ultralow Phase Noise Signal Source With Photonic Delay-Lines. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2025, 73, 5340–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).