Federal Grants, Racialized Eligibility, and Ideological Control: The New (E)quality Politics of Higher Education

Never before has the role of the federal government in underwriting U.S. higher education been more visible than in the early months of the second Trump Administration. The Administration’s executive orders (EOs) targeting education and agency actions--including the “Dear Colleague” letter (DCL) on the chilling extension of the

SFFA v. Harvard decision

1—have banished the old refrain from scholarly vernacular that higher education policy is largely an issue of the states. In addition to the substantial resources delivered via federal student financial aid, the Administration’s aggressive anti-Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

2 and anti-science attacks have exposed the reliance within higher education, especially among research institutions, on federal grantmaking infrastructure. Higher education institutions’ responses to these attacks have been mixed and disjointed, and these responses matter to the day-to-day persistence of equity work on college campuses and in classrooms (Pedota et al., 2025). Some orders have sparked immediate lawsuits--e.g., the proposed National Institutes for Health (NIH) indirect cost (IDC) cap—while others have been met with crickets and anticipatory overcompliance (Garces et al., 2021; Briscoe et al., 2025) --e.g., the executive order banning federal funding for so-called DEI programming and research. Many scholars and policy analysis in the field describe these attacks as unprecedented, and perhaps that is reason enough for the dearth of organized resistance at affected institutions of higher education (IHEs).

Although the recent wave of executive orders includes some unprecedented elements, the underlying ideological tactics are largely recycled from earlier periods of post–civil rights backlash, most notably during the Nixon and Reagan administrations, when similar strategies were used to undermine progressive visions for a robust federal education infrastructure. In this paper, we use the (e)quality politics framework to analyze both the Trump administration’s assault on federal grantmaking infrastructure and the responses of targeted institutions and advocacy organizations. As defined by McCambly and Mulroy (2024), (e)quality politics is a four-stage regressive model of political backlash in which a new policy paradigm reframes equity goals around the need to protect the perceived “quality” of institutions or sectors, particularly in education.

Grounded in historical patterns of racialized policy backlash, the (e)quality politics framework provides a strong analytic foundation for examining the Trump administration’s coordinated backlash against college campuses. Using this framework allows us to not only parse the underlying, racialized ideology of these political moves, but also to anticipate mechanisms for resistance that will be more or less effective at preventing or slowing the crystallization of a new status quo. We use a comparative case study approach to ask:

1) How is the Administration framing and operationalizing its policy attacks on the work of higher education (research, teaching, community engagement/mission)?

2) How are institutions and advocates framing and operationalizing their responses or resistance to these policies?

3) How do responses from institutions and advocates counter the Administration’s attacks in ways that will either slow or advance the progression away from higher education’s engagement with equitable educational opportunities?

We find that the Administration’s anti-DEI policy moves mark a decisive shift in the operation of (e)quality politics: away from stratifying advantage among elite institutions and toward a systematic project of political purification in higher education, driven by white racial resentment (Taylor et al., 2020). Across institutional sectors, the Administration’s agenda targets equity-oriented programs, scholarship, leadership, and curricula as objects of elimination rather than redistribution. By juxtaposing these racialized attacks with successful collective resistance to proposed federal research funding caps, we expose the asymmetry in how IHEs defend science but often abandon equity. Finally, we show that the Administration’s deliberately vague and coercive use of (e)quality politics fragments institutional solidarity and installs a racialized compliance regime that reshapes institutional legitimacy, compresses academic freedom, and steers higher education governance toward authoritarian rule.

Federal Grantmaking and Higher Education

Long before this political moment, grantmaking has been a powerful tool for shaping education policy in moving towards (or away from) educational equity (Loss, 2014; McCambly & Colyvas, 2022; Natow, 2022; Williams, 1991). As a mechanism, grantmaking—which the federal government is by far the largest player in the grantmaking game—is powerful both because of the material resources it provides as well as how those resources shape the networks of stakeholders empowered to influence change, the designs seen as legitimate, and public conversations around pathways forward relating to equity and inequity (Reckhow & Tompkins-Stange, 2018; Tompkins-Stange, 2016). This small but growing body of scholarship tracking the influence and impacts of grantmaking in education has only recently taken up questions about the role of racialization

3 and grantmaking’s role in shifting or (re)creating inequalities via racialized funding strategies (e.g., Francis, 2019; McCambly & Colyvas, 2022; McCambly et al., 2025; McCambly & Aguilar-Smith, 2024, Wooten, 2010). In the context of this paper, we focus specifically on federal grantmaking including programs explicitly concerned with education (e.g., the grants delivered via the Institute for Education Sciences out of ED) and those that implicitly underwrite the research functions of IHEs (e.g., NSF and NIH grants).

For decades, the Department of Education (ED), as the federal government’s education arm, has had at least an ostensive interest in equal opportunity and broadening participation in the education pipeline--no matter how imperfect, underfunded, or incomplete (Baker, 2019; Graham, 1992; Loss, 2014; Melnick, 2018). Beginning in 1968, even before the creation of ED, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) has been charged with collecting data and investigating civil rights violations in schools; this commitment has taken new forms over time. Indeed, ED and OCR have historically played a critical role in ensuring civil rights compliance, in particular in states opposed to doing so (Lewis et al., 2019). ED’s role in supporting educational equity has also included other instantiations over time, such as the suite of TRiO programs, the introduction of multiple developing minority-serving institution programs, as well as new initiatives developed during the Obama Administration under the auspices of economic development, innovation, and global competition (Boland, 2018; Gasman et al., 2015; McCambly & Colyvas, 2022; McElroy & Armesto, 1998). Many of these policy imperatives have been underwritten via federal grant programs ranging from the Institute for Education Sciences’ research grants to Title X to the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) education portfolio. In sum, the postsecondary educational ecosystem has become dependent on these sources of funding in ways that often go unexamined. To this end, recent executive orders curtailing federal grantmaking even tangentially related to equity struck a chord within the academic community, waking some up to just how vulnerable our research, institutions, and programming are to extreme ideologies under this administration.

Contrary to current regressive narratives that accuse agencies like IES and NSF of unfairly favoring “woke” projects and undeserving PIs of color, there is no evidence that federal funding has been hijacked undeservedly by PIs of Color, nor that the PIs of Color who have been funded are in any way undeserving (U.S Department of Education, 2025). Quite the opposite. The field of academic knowledge production continues to favor white epistemologies and forms of scholarship (Gonzales et al., 2013, 2024; Settles et al., 2022). Certainly, if DEI policies were effectively overriding the “highest quality” institutions and PIs in federal grantmaking, then we would see PIs of Color and Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) eating up a disproportionate share of federal research funds. But of course, that has never been the case. For as long as the federal government has been in the research grant game, there has been disproportionality in the use of funds in favor of white and male PIs and the most elite and white-serving institutions (Chen et al., 2022; McCambly & Colyvas, 2022; Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). That is not to say that this disproportionality has been static across all funders. NSF, for instance, through its education research programs has directed a slowly growing proportion of its funds to PIs of Color and MSIs

4. Most of these gains have indeed been made through programs that center either the development and investment in MSIs and/or research intended to “broaden participation”—the language and criteria introduced at NSF in 1997 to indicate interest in achieving equity in the participation in and success of marginalized groups in the sciences (McNeely & Fealing, 2018). In other words: research that either incorporates or at least gestures at DEI.

Over the last 25-plus years, the broadening participation aim has provided direct incentive to countless women and Scholars of Color to invest time into work at the intersection of equity and the sciences as a contribution to a thriving democracy and a stronger economy. But now, the same window through which many Scholars of Color have gained access to federal research dollars is being used as a guillotine to abruptly cut off their influence in the future of the academy and knowledge production. And to be clear, this strategy could make a clean and devastating cut. As researchers, our careers, labs, and ability to train students can hinge on access to grant funds--the most robust of these funds come from the federal government (Mathews, 2012; Blume-Kohout et al., 2014; Graddy-Reed et al., 2018). As such, the years of funneling Scholars of Color into the (meaningful and important) work of “DEI” have also made Scholars of Color an easy and accessible target for the Trump administration’s material punishment.

Equity-Quality Tensions and Racialization in Education

As alarming as the Trump Administration’s pronouncements may be to some, these claims of the decline of excellence and merit in higher education as a result of the supposedly corrosive effects of equity programs on college campuses are not new (see, e.g., Jabbar et al., 2022; López, 2013; McCambly et al., 2025; McCambly & Mulroy, 2024). What we see in the anti-DEI movement of 2021-2025 is not really a battle over the effectiveness of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives on educational outcomes. If this were the case, the Administration would be arguing with greater evidence and specificity that DEI policies are failing to achieve their goals. Instead, this is an organized political strategy to discredit and reset the terms of policy debate in higher education (McCambly & Mulroy, 2024). The current political discourse is taking a different, more urgent tone and doing so contrary to all empirical evidence by claiming that DEI policies threaten the excellence and fairness of U.S. higher education by disadvantaging white people and especially white men. We see, for example, these same false claims about threats to educational quality or meritocracy emerge in the rhetoric motivating the state-level anti-DEI and anti-CRT legislation that has been the proving ground for emergent federal actions (Hazel, 2025; Shook & Lizarraga-Dueñas, 2024).

The implied link between educational quality and equity is deeply rooted in the history of racial segregation in American educational policy. Generations of unequal public investment in segregated school systems created stark material differences between "white" and "Black" schools, shaping perceptions of their relative quality and, by extension, the students they served (Freidus, 2022; Massey, 2007; Massey & Denton, 1993; Trounstine, 2018). The Supreme Court, in its landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, explicitly acknowledged this dynamic, stating that racial separation was widely interpreted as a sign of Black inferiority. While some viewed integration as essential for ensuring high-quality education for Black students, others expressed concerns about its potential negative impact on white schools. Such rhetoric, shifted policy discussions away from structural solutions like resource redistribution through desegregation and toward cultural explanations that attributed educational disparities to student characteristics (Freidus, 2022; Freidus & Ewing, 2022). As a result, we often see opposition to affirmative action and equal opportunity policies in the political sphere framed as a defense of educational quality and excellence (Augoustinos et al., 2005; Baker, 2019; Morrison, 1993; Sulé et al., 2017). This comes despite decades of empirical research debunking fears that racial integration diminishes educational quality (e.g., Jackson, 2009; Jencks & Brown, 1975; Reber, 2010; Tuttle, 2019; Weinberg, 1975). To the contrary, extensive interest-convergent research has demonstrated the benefits to white students of learning in racially diverse postsecondary environments (Locks et al., 2010; Jayakumar, 2015).

Many scholars have noted that these racist assignments of quality deficits are managed and facilitated at the level of organizations rather than individual bias (Wooten and Couloute, 2017; Ray, 2019). The foundation of U.S. educational institutions in the period of de jure segregation of social goods in the U.S. resulted in the creation of separate organizations to serve minority communities (Wooten and Couloute, 2017; Ray and Purifoy, 2018). As a result, these organizations were ascribed a racialized identity (Ray, 2019). This identity then facilitated de facto systemic disparity in the delivery of resources, sometimes referred to as an inequality regime (Acker, 2006, see also Ray, 2019; Wooten & Couloute, 2017), in which racialized organizations are constructed as undeserving of resources or recognition. In so doing, “racialized inequality regimes give credence to claims that organizations not serving the White racial project deserve fewer financial and political resources than those that do” (Wooten & Couloute, 2017; see also Omi and Winant, 1986). Wooten (2015), for example, points to the privilege afforded to primarily white colleges, regardless of their ability to serve Black students, as an underlying driver of poor political support for HBCUs. In other words, inequality regimes can, among other things, legitimize resource inequality by building on assumptions of inferior deservingness.

Much like the notion of racialized inequality regimes, Ray’s (2019) Theory of Racialized Organizations (TRO) proposes that racialized organizations create rules and norms that legitimate inequitable resource distribution by differentiating white and minoritized organizational types. In practice, this means an organization’s claim or proximity to whiteness ascribes status that legitimates “bureaucratic means of allocating resources by merit” (Ray, 2019, p. 41). Recent work has demonstrated how these bureaucratic means for racialized resource distribution can be managed and maintained through the instantiation of norms and metrics that systematically favor white organizations without having to name race (McCambly & Mulroy, 2024; McCambly et al., 2024). For example, at the turn of the 20th century, Black medical schools were either shut down or relegated to lower-tier status through the creation of quality metrics that were based on the resources possessed by the most elite, white medical schools (McCambly et al., 2024). These metrics were institutionalized and legitimized unequal investment on the premise that only the highest-quality” schools were “good” investments by major philanthropic players. In turn, inequitable long-term investments actually crystallize the place of white institutions as the most deserving for decades to come.

(E)Quality Politics as a Historically Grounded Framework

Building on this understanding of American higher education’s stratification as racialized from the start (see, e.g., Bastedo & Gumport, 2003; Bastedo & Jaquette, 2011; McCambly et. al, 2023), we can begin to understand how political calls back to “quality” preservation can be, in material terms, racist dog whistles (Lopez, 2013). Indeed, much of the current political discourse linking equity reforms to institutional quality decline is actually recycled from an anti-equity playbook developed during the 1960s-80s (McCambly & Mulroy, 2024). Both then and now, this discourse has served as a powerful tool of racial backlash to civil rights transformations. For example, in the 1960s-1980s to federal student aid policies that expanded access to higher education; and today to the renewed attention granted to matters of racial equity in response to the Movement for Black Lives, as evidenced by the proliferation of public-facing university DEI statements, heightened media coverage of postsecondary policy issues (Baker et al., 2023), and shifts in philanthropic funding priorities (McCambly, 2023).

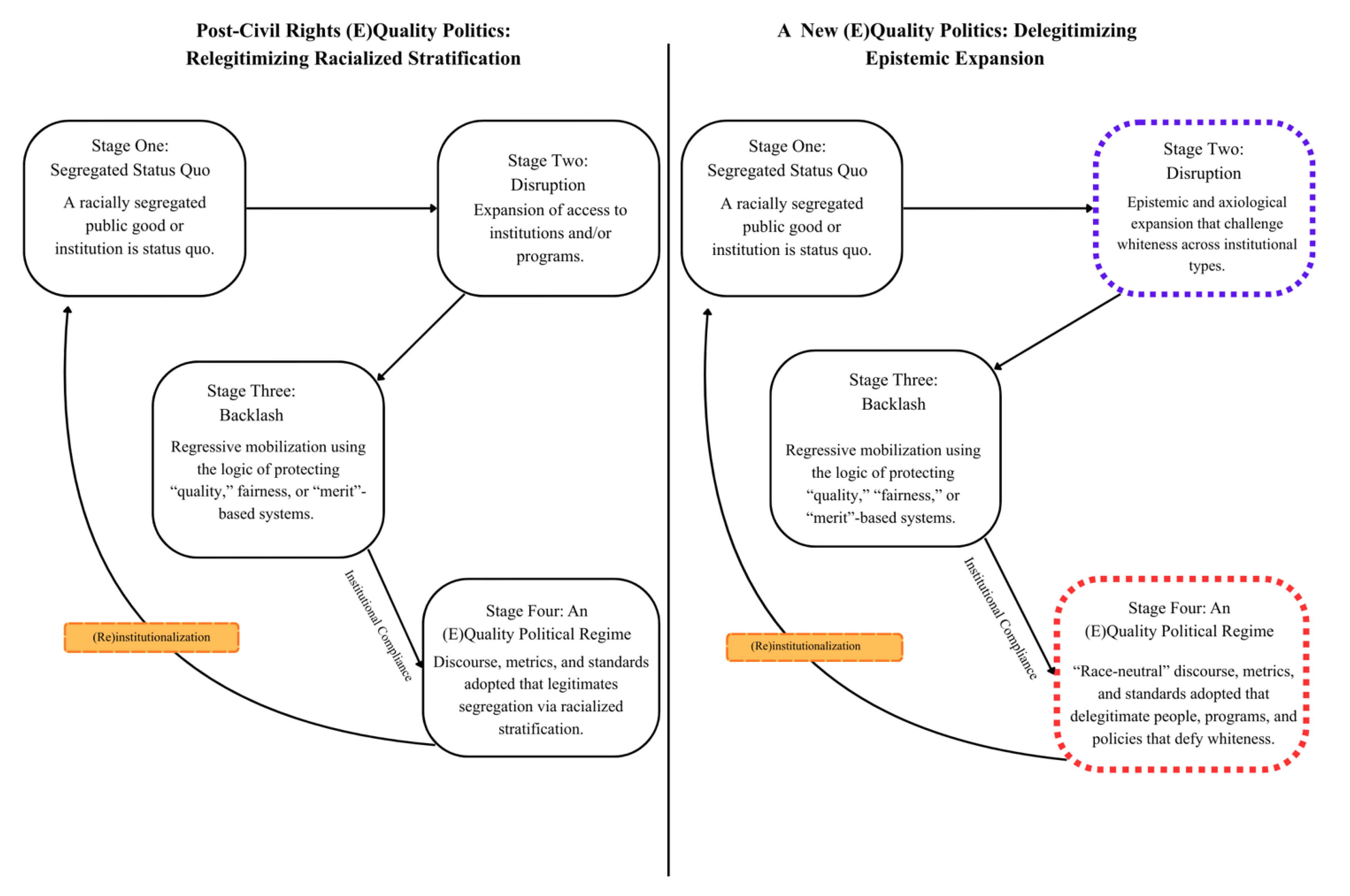

The Reagan administration was particularly successful in its use of this anti-equity playbook to shape federal education policy; even the rollback of federal financial aid could be linked to racialized rhetoric about “low-quality” institutions and “militant,” or “undeserving” postsecondary students (Loss, 2014; McCambly & Mulroy, 2024; McIntush, 2000). Analyzing discourse from this era, McCambly & Mulroy (2024) developed the (e)quality politics framework as a model for understanding the regressive political backlash pattern. (E)quality politics is characterized by the introduction of a policy paradigm that eschews equity commitments in favor of fear-based and white-supremacist policymaking that framed as the protection of educational quality. Under this model, a racially inequitable status quo (first stage) in a policy area is disrupted by the introduction of policies that promote equal access or delegitimize racial exclusion (second stage). One can point to the rise in the late 2010s, reaching its apex in 2020, of support for and attention to racial equity programs, policy, expertise, and curriculum in higher education as this second-stage disruption.

However, equitable expansion provokes a third stage: organized coalitions accustomed to exclusive access to public goods—in the present case conservative politicians and other members of the emergent white nationalist movement—use fear-based rhetoric to argue that changes will or have compromised educational or institutional quality. Subsequently, the progression of backlash politics involves, in the fourth stage, the development and eventual predominance of “quality” or “merit”-centered objectives and standards that redirect that activity of organizations charged with implementing equity policies. These objectives become institutionalized through new criteria, standards, and metrics that govern the future distribution of resources.

Critically, McCambly & Mulroy (2024) found that a driving mechanism of these backlash politics was the successful creation of a fear-driven discourse that relies on the construction of a resonant and contrastive pairing of a worthy policy beneficiary whose interests are threatened by some emergent, oppositional population. This regressive pairing—or beneficiary-threat dyad—can be used to justify the initiation of threat-based policy rhetoric that positions, for example, elite, white IHEs (beneficiaries of policy) as the standard bearers of educational quality essential to American prosperity. In the post-civil rights context, elite IHEs were then pitted against the incoming threat population (e.g., Students of Color) created by the expansion of educational access. The right’s rhetoric justified policy proposals that institutionalized and rewarded features and metrics of white institutions to protect educational quality and American exceptionalism. By contrast, the progressive policy actors of the day failed to counter the right’s compelling beneficiary-threat dyad and instead attempted to adopt quality rhetoric while quietly merging their own civil rights goals into their definition of quality--a move that did not delegitimate the racialized elements of the right’s policy proposals. Using a comparative case study approach, we will extend the (e)quality politics framework to examine the current administration's regressive and destabilizing political regime.

Study Context

Project 2025 (also known as the Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise), which served as an extensive blueprint for the second Trump Administration’s policymaking, laid out a plan to overhaul, among other things, U.S. higher education. Project 2025 aimed to remove “radical ideology” from all educational settings and to embed its priorities into existing structures such as accreditation (see, e.g., the Project 2025 section labeled “Attacking the Accreditation Cartel”), eliminating external influences on funding, and reforming “area studies” funding. Importantly, regressive state-level anti-DEI action and legislation has been an intentional staging ground for the development of Project 2025 involving many of the same political actors and conservative think tanks (Jones & Briscoe, 2025). Once in office, the Trump Administration launched directly into these reforms, attacking federal higher education research funding, accreditation, and DEI policies. Much of this rhetoric echoes the “quality-focused” talking points carefully crafted decades prior by Nixon- and Reagan-era officials. This rhetoric, then and now, decries the erosion of educational standards that, they argue, result from admitting more diverse students, making DEI investments, or incorporating “partisan” curricula like critical race theory, Black studies, or feminist and queer theories (i.e., “area” studies). Today’s (e)quality rhetoric delegitimizes anti-racist pedagogies, expertise, and policies as real and present threats without evidence that any measurable public good has, in fact, been damaged.

Despite similarities in rhetoric to past instantiations, the Trump Administration is advancing these regressive political goals via new policy mechanisms. Unlike historical disruptions, which focused on equalizing access to higher education, the most recent pro-equity disruption was not limited to the expansion of access, which largely focuses on the expansion of more open-access institutions. Instead, the equity advances of 2018-2022 legitimated the intellectual and ideological place of minoritized communities across institutional strata from community colleges through Ivy League institutions (Meikle & Morris, 2022). We come to the current process in the midst of the third—the backlash and threat (See

Figure 1 in the Discussion)—stage, but have not yet reached the institutionalized redirection of equity policies via new criteria, policies, or norms. We are, however, frighteningly close.

Data and Methodology

We use a comparative case study design looking at federal policy threats and public responses to those threats from 18 IHEs as well as 11 advocacy organizations to support in-depth analysis of patterns within and across bounded systems (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016; Yin, 2018). Rather than comparing across IHEs, although we consider variation among them, the focus of our comparative analysis is looking at IHE responses to attacks on IDC rates v. attacks on “DEI” and all forms of institutionalized equity work. A comparative case approach focuses on testing theoretical propositions across similar, yet strategically varied contexts (Yin, 2018). This approach helps us expansively analyze dynamics of institutional positioning and emergent compliance or resistance logics in the context of federal financial threats.

To examine the underlying political ontology of the Trump Administration’s attacks on DEI, particularly through federal postsecondary grantmaking policy, we collected data for comparative purposes on the Administration’s policymaking about two high-profile and simultaneous moves to curb the generosity of federal grant dollars to IHEs: 1) emergent policies out of the National Institutes for Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation capping IDC at 15% (which would result in billions of dollars in cuts to IHEs), as well as 2) the anti-DEI Dear Colleague Letter (DCL) out of the U.S. Department of Education (ED) and three executive orders (EO) targeting DEI-related projects, contracts, and grants more broadly, including at IHEs and accreditors. We look not only at the administration’s political tactics, but also at documents that speak to institutional responses and non-responses to both the IDC-reduction and the anti-DEI threats to federal funding to IHEs. We look at individual institutional responses and at what we call “organized” responses--that is, guidance, advocacy, advisement, or direct action/litigation taken by a collective of institutions, experts, or association(s) to both the IDC-reduction policy and anti-DEI orders and guidance.

In the sections that follow we first describe our approach to identifying public-facing artifacts out of the Trump Administration, our use of a congressionally assembled public database to create a stratified sample of IHEs from which to collect data, and how we supplemented these data with other advocacy organizations’ formal responses to federal attacks on higher education infrastructure. We then detail a multi-step critical policy discourse analysis used to surface both the nature of the policy proposals and responses and how each type of actor--government, organized advocates, and IHEs--leveraged, or not, (e)quality political ideology to mobilize policy benefits and burdens.

Data Collection and Initial Coding

Data collection began with a search of Trump Administration EOs from January 18th, 2025, to May 2nd, 2025, as well as agency directives for policymaking artifacts directed at creating new federal restrictions on grantmaking to IHEs. These documents included two executive orders, proposed anti-DEI legislation, new NIH and ED guidance artifacts, and a Trump Administration FAQ. To understand the resistance or compliance of the field, broadly defined, we expanded our archive in two ways. First, we utilized the publicly available federal funding database

5 published by the U.S Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, & Transportation. This database was the product of an investigation led by Senate Commerce Committee Chairman Ted Cruz to identify “woke DEI grants” distributed across federal grantmaking mechanisms. This report claimed that federal funding agencies were supporting “questionable projects that promoted Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) or advanced neo-Marxist class warfare propaganda.”

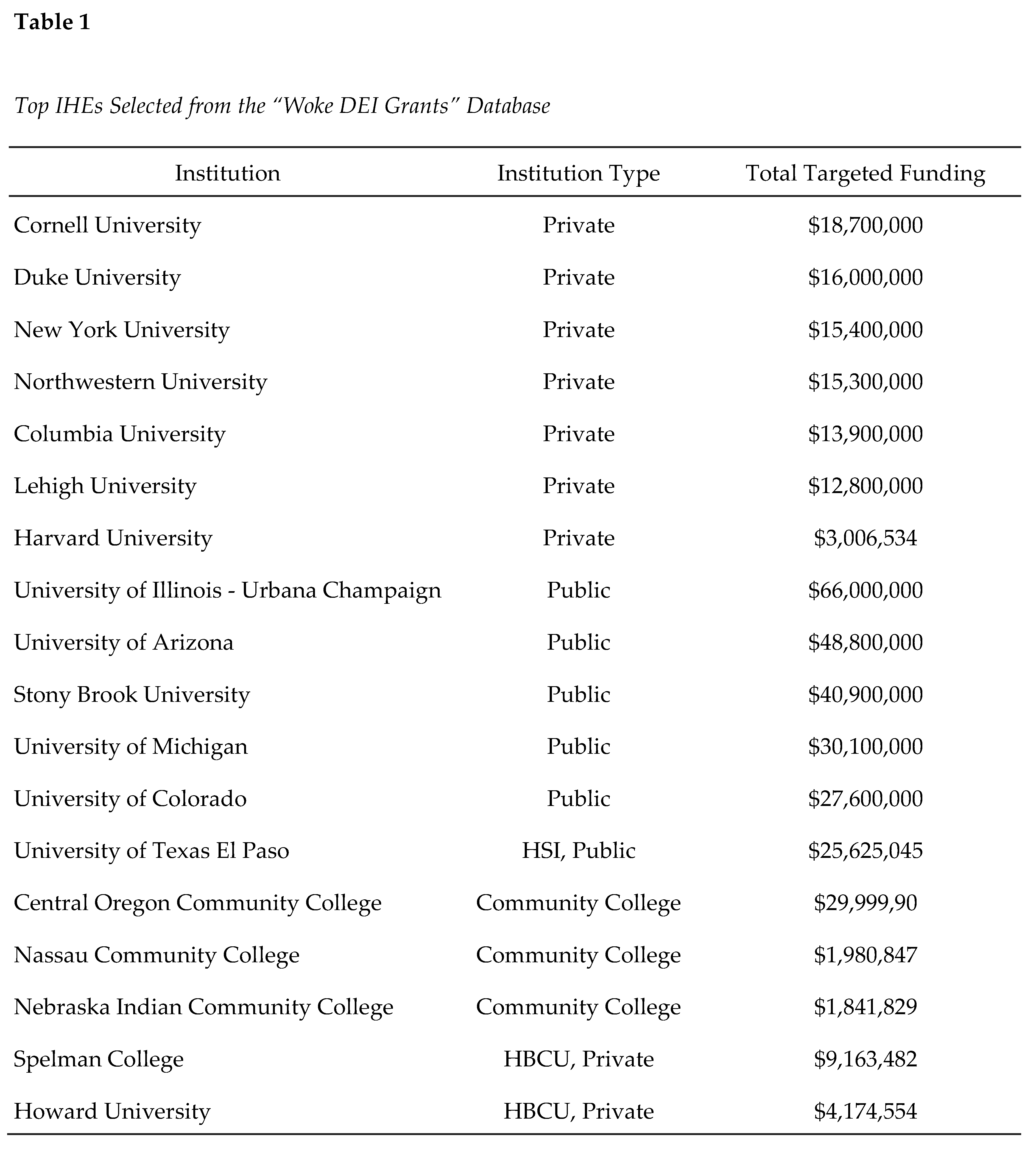

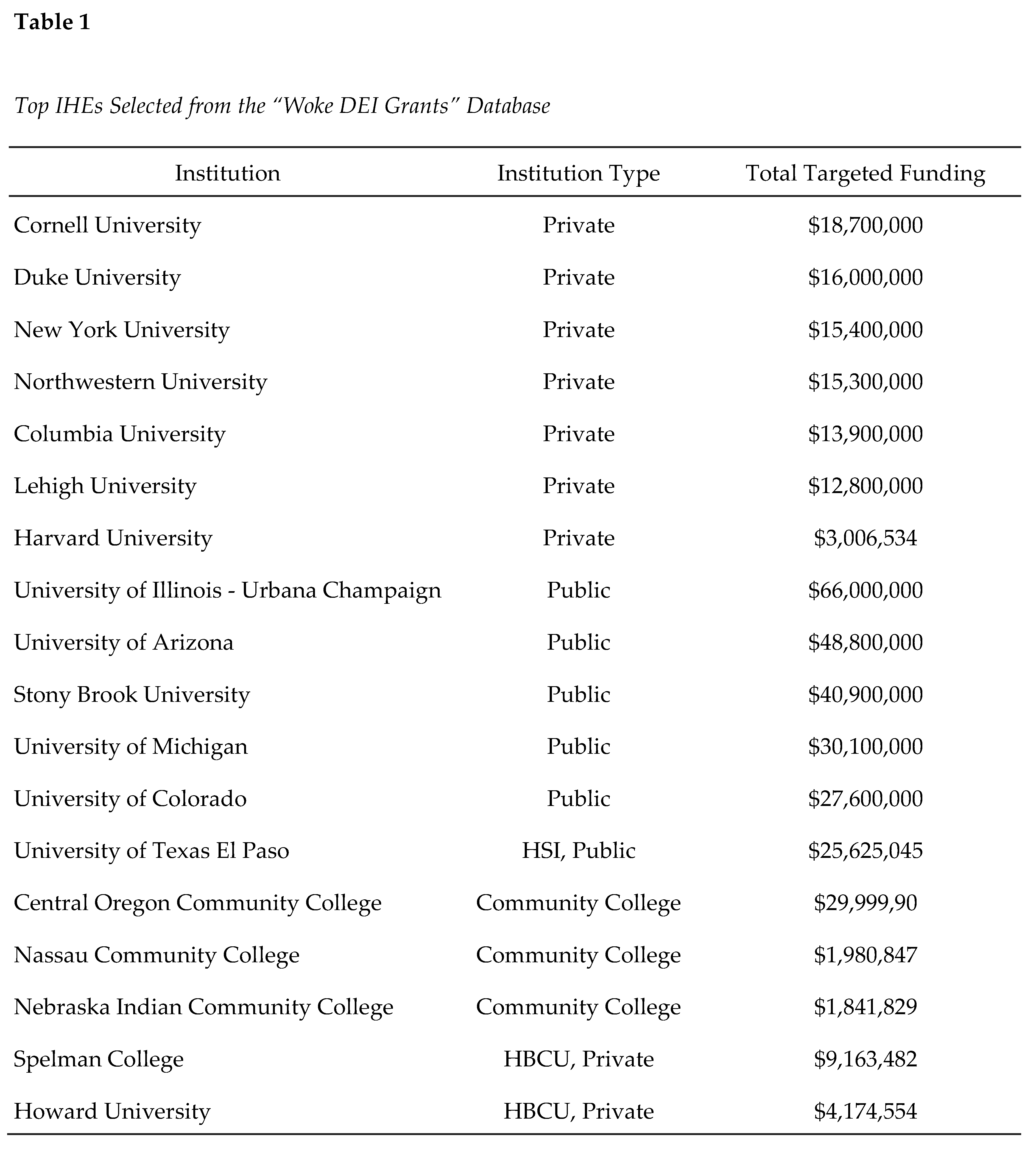

We used this database to help us identify a sample of IHEs likely to be experiencing significant, direct anti-DEI threats. We did so by summing the total awarded grant dollars by institution (e.g., creating a single total for the University of Michigan across all grants listed as “woke” on this database) and rank-ordered the institutions to select the top five public and private institutions according to their grant totals. This list only included one HSI and no HBCUs or community colleges. Given our assumption that these types of racialized organizations might respond differently than PWI-R1s, we expanded our list to add one additional HSI, the top two HBCUs, and the top two community colleges on the list. We also added Harvard University and Columbia University to our sample, given the Administration’s focused targeting of these institutions, which brought our total sample to 18 IHEs.

From there, our data collection process began with a comprehensive search of all 18 university websites using the search terms executive orders, federal funding, federal research funding, federal guidance, and policy change. We saved PDF screen captures of any relevant communications or webpages focused on recent administrative and agency actions. We conducted parallel searches using Google News to identify announcements or news stories not properly indexed on the university website. We organized these materials by site into chronological archives, eliminating any documents that were superfluously included but did not address federal research funding cuts or anti-DEI legislation. These searches yielded 68 documents meeting our inclusion criteria.

We recognized, however, that individual IHEs are not the only actors that can respond to such political attacks. They may also respond as members of collectives through litigation and/or through various membership organizations or expert bodies. To this end, we expanded our dataset by identifying high-profile, organized responses to these specific executive orders and agency directives for instances of collective organizational or political tactics.

In total, we collected 95 documents ranging in length from one to 49 pages. See

Appendix A for a complete list of all federal and field-response documents with public access links. We converted all of our data to .doc format and uploaded each document to Dedoose--a cloud-based qualitative coding software. We applied document-level codes to identify each text according to its assigned actor type: administration, university response, advocate, or organized responses.

Critical Political Discourse Analysis

Aligned to our research questions, we combined features of critical discourse and policy analysis. In the tradition of critical discourse analysis, we treat discourse as a process and output of the social and political construction of meanings (Gee, 2004; Howarth & Stavrakakis, 2000). Discourses confer politicized identities onto things (e.g., student loans) and people (e.g., student debtors) by giving each meaning. These meanings are not organically emergent but rather are a product of purposive political action conducted via discursive activities, with implications for the distribution of social goods (Gee, 2004). These discursive activities—and the tools they create—shape knowledge systems and existing power structures and positionalities (Fairclough, 2013). Of particular importance to the creation of ongoing sources of power (and therefore inequity) is the process of naturalization (Fairclough, 1989), in which language is used to condition members of society to accept particular conventions or practices, even those that are not in their best interest.

Our research questions are fundamentally concerned not only with the discursive moves underlying the current anti-DEI attacks and responses, but the formal policies being advanced by these discourses (Anderson, 2012; Fairclough, 2013). To this end we deploy a critical policy lens, derived from the (e)quality politics framework (McCambly & Mulroy, 2024), attuned to the relationship between elements of discourse--in this case the socially constructed policy beneficiary and threat populations (which paired together become a beneficiary-threat dyad) --and the promoted policy proposals (Hyatt, 2013).

As in much qualitative research, our data collection co-occurred with the analysis process (Tisdell et al., 2025). Sensemaking began for us as early as developing data collection protocols and gathering initial data sources. To this end, we used the (e)quality politics framework to make sense of our initial read of our data and established finer-grained analytic questions that would inform our first-round, deductive coding (Miles et al., 2013). These analytic questions were: 1) In what ways, if any, are actors using quality and equity concepts in their policy arguments and proposals? 1a) Who or what is being positioned as the beneficiary of the policy? 1b) Who or what is the threat? 1c) What policy mechanisms or proposals are actors advancing? 2) How do these constellations of threats, beneficiaries, and policy proposals vary by actor type? We designed our codebook to be responsive to these analytic questions and were able to sort and view responses based on actor type.

We calibrated our application of the coding scheme by coding sets of two to three transcripts individually and meeting to discuss inconsistencies. At each step of the coding process, we conducted multiple, iterative synchronous calibration meetings in which we discussed discrepancies in code applications and refined our respective interpretations of the codes. Every document in our corpus was coded separately by two of the authors, with any discrepancies reviewed and resolved.

Motivated by our research questions, we conducted a second round of axial coding in which we inductively characterized, for each actor type, the range and density of specific threat populations, threat mechanisms, beneficiary populations, objects of benefit, and policy proposals to identify common constellations of beneficiary/threat dyadic pairings with policy responses that we characterized according to inductively grouped policy mechanisms (e.g., legislation, litigation, compliance, direct (illegal) agency action, intimidation).

Findings

First, we present our findings about both the Administration’s approach to framing and operationalizing its policy attacks and institutional responses in the case of NIH and NSF IDC cuts. Second, we move to the same in the context of anti-DEI attacks made through EOs and the DCL, and institutional responses. We note that the Administration’s approach to threaten higher education institutions of all types and across strata is similar in both its racialized and (nonracialized) attack on funding. Despite this similarity, our analysis of the underlying discourse and linked policy mechanisms reveals critical differences derived from the threat-based and racialized discourse surrounding anti-DEI policy adoption. These differences, in turn, may be related to the divergent responses and resistance from IHEs and other actors when comparing responses to the IDC (nonracialized) versus anti-DEI (racialized) administrative policy actions. We argue that while both the IDC and anti-DEI actions threaten university coffers across organizational strata, the Administration identifies within IHEs a threat, in the form of “DEI,” to educational quality and “meritorious” Americans that can be weeded out. As such, the policy provides the opportunity to comply to eliminate this threat and avoid (unlawful) punishment. The Administration does not, however, construct a similar threat in its attempt to roll back IDC generosity--a difference that we posit is critical in terms of how IHEs discursively and materially fought back.

Research IDC Rollbacks: Another Efficiency Fight

Our analysis of NIH and NSF guidance reveals a clear appeal for efficiency by the administration in arguments developed around new policies that slashed billions from university research budgets via IDC rates. The NIH announcement, the first move on IDC which came just 18 days after the start of the administration, placed a cap of 15% on indirect costs for all future grants. In this announcement, the administration framed inefficiency and potential misuse of funds as threat to government efficiency and ultimately the taxpayer. Later, on May 2, 2025, new NSF guidance echoed the NIH announcement with the new policy’s stated goal to “streamline funding practices, increase transparency, and ensure that more resources are directed toward direct scientific and engineering research activities” (National Science Foundation, 2025). The central objection to IDC stems largely from a concern that indirect costs pose an oversight problem– “indirect costs are not readily assignable to the cost objectives specifically benefitted and are therefore difficult for NIH to oversee” (Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement). The NIH’s duty is framed as to “carefully steward grant awards to ensure taxpayer dollars are used in ways that benefit the American people” which means that difficult to regulate indirect funds need to be cut “to ensure that as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead.” It is implied, then that IDC have no direct benefit to the American people.

The NIH goes on to explain the rationale for IDC cuts by noting that “most private foundations that fund research provide substantially lower indirect costs than the federal government, and IHEs readily accept grants from these foundations….the most common rate of indirect rate reimbursement by foundations [is] 0%, meaning many foundations do not fund indirect costs whatsoever. In addition, many of the nation’s largest funders of research have a maximum indirect rate of 15%.” Implied here is the stance that the federal government has no obligation to pay more in indirect costs than any other organization.

In short, in its attempt to roll back IDC generosity, the Administration’s policy discourse implies a policy problem in higher education--a failure of efficiency and oversight--but not a clearly constructed beneficiary-threat dyad. That is, the proposed policies and surrounding rhetoric are not clear on who is being harmed and who is doing the harm. These attacks are directed indiscriminately against all eligible IHEs, and implicitly individual researchers as well. The policy problem, ostensibly named as the inability to provide sufficient oversight to ensure that indirect funds directly benefit the American people, implicitly positions taxpayers as the potential beneficiaries of a policy change, but even that argument is indirect. Without an identified threat, the proposed policy itself is thus an immediate and across-the-board cut to benefits. Critically, the immediacy and (nonracialized) universality of this policy move offers no quarter to institutions willing to comply or change to avoid negative funding consequences.

IHEs and Advocates Unite and Respond

Institutions’ and advocacy organizations’ responses to NSF and NIH funding threats was swift, united, and constructed around a compelling beneficiary-threat dyad. Within three days of the February 7, 2025 announcement of the initial IDC cuts, the American Association of Universities (AAU)-considered by some the most powerful of university associations--along with the American Council on Education (ACE), the Association of Public Land-Grant Universities (APLU), and a collective of high-profile research universities joined together in a lawsuit against the NIH. This lawsuit not only pushed back on the unlawful nature of the policy but also framed the NIH policy as an unequivocal threat to the good of the American people. A similar lawsuit, with many of the same plaintiffs, including the AAU, APLU, and ACE, was filed after the May 2, 2025, rollout of a nearly identical IDC reduction at the NSF. Discursive responses centered the scientific enterprise as inseparable from the university mission and position the Administration’s efforts as a threat to society in sweeping terms. For example, the plaintiffs argued that the NIH cuts

“will devastate medical research at America’s universities. Cutting-edge work to cure disease and lengthen lifespans will suffer, and our country will lose its status as the destination for solving the world’s biggest health problems. At stake is not only Americans’ quality of life, but also our Nation’s enviable status as a global leader in scientific research and innovation.”

Plaintiff’s language with regard to NSF was nearly identical, lifting the “global leader” and “scientific research and innovation” language directly, while focusing on scientific innovation and contributions to industry rather than health science specifically. The NSF lawsuit also sought to myth-bust by quantifying the significant investment that American IHEs already contribute to cover IDC, arguing that in the “2023 fiscal year, universities bore $6.8 billion in unrecovered indirect costs.”

The university and Association plaintiffs in both lawsuits did not limit the threat to the medical and scientific well-being of the Nation, but also named the move as “an affront to the separation of powers,” stating that before this mandate Congress had

“exercised its constitutional power of the purse and forbade the executive from expending appropriated funds on trying to do so again. Yet NIH defied Congress’s express directives as to this core congressional power and issued the February 7th directive anyway—and NIH will continue to violate Congress’s express commands so long as the directive remains in force.”

Similarly, institutions in the sample expressed immediate concern and named the Administration’s stances on IDC as imminently harmful to their own institutions but also to communities and to scientific innovation more broadly. By participating in litigation and through their public-facing materials, institutions responded to IDC-reduction attacks in public ways both discursively and materially. For example, Duke University argued that

“Much is at stake. Our nation’s world-leading research enterprise has been enabled by—and will only be sustained by—partnership and co-investment from both the government and higher education. If these large funding reductions are allowed to stand, they will necessitate careful planning and difficult decisions.”

Tying university research to societal wellbeing, medical advancement, and maintaining the U.S. as a global power, while positioning the NIH policy change as a direct threat to that wellbeing, is a unifying theme across institutional responses. In another example, Cornell emphasized that IDC is

“…an essential component of the decades-long partnership between the federal government and universities to conduct research that saves and improves lives and adds immeasurably to our economy. Federal cost sharing extends to many government agencies, and we are concerned that each of them may, in turn, be affected. These cuts violate this extraordinarily successful partnership and, if enacted, will irrevocably harm U.S. research and financially destabilize Cornell and universities across the nation.”

Materially, institutions banded together and worked with major associations to litigate and seek a legal remedy that would return funding policy to the status quo.

The Administration’s Attacks on DEI: A Fight Over the Future of Eligibility

The U.S. Department of Education (ED) and the Trump Administration (through EOs and the DCL) leveraged attacks on IHEs by introducing new eligibility requirements for federal funding streams, including but not limited to major federal grants. Our analysis surfaced how this attack was framed as a response to a threat to the American people, driven by ideology that harms quality in curriculum, students, research, and public value. The administration thus framed policies, programs, and practices motivated by DEI concerns as a way that IHEs have “[smuggled] racial stereotypes and explicit race-consciousness into everyday training, programming, and discipline” (DCL).

The Administration first articulated this alleged threat in a Dear Colleague Letter (DCL) issued by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights on February 14, 2025. The DCL, which ostensibly draws on legal precedent from Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, characterizes a wide range of DEI-related practices—such as the elimination of standardized testing, the use of diversity statements, and decisions affecting student, academic, and campus life—as discriminatory and as threats to students’ right to “a school environment free from discrimination.” The letter explicitly claims that “American educational institutions have discriminated against students on the basis of race, including white and Asian students,” thereby reframing DEI—whose stated purpose is to remediate racial inequality—as a source of harm to these groups. While the formal justification for dismantling DEI policies is framed as protecting students from racial discrimination, the DCL simultaneously seeks to prohibit teaching that “the United States is built upon systemic and structural racism” and to bar instruction suggesting that “certain racial groups bear unique moral burdens that others do not.”

This letter was also the first to call out that the administration intended to take “appropriate measures to assess compliance with the applicable statutes and regulations… embodied in this letter… including anti-discrimination requirements that are a condition of receiving federal funding.” (DCL). After using the DCL to put the entire field on notice, the Administration went on to rattle IHEs metaphorical cages via targeted attacks on high-profile institutions. For example, the administration’s April 11, 2025, letter to Harvard outlines a series of demands as well as the consequences of failing to satisfy “with the intellectual and civil rights conditions that justify federal investment.” The letter demands that Harvard must restructure its governance so that authority rests with tenured faculty dedicated to the university’s scholarly mission, while reducing the power of activist-oriented students, untenured faculty, and duplicative committees. Additionally, it must eliminate all race-, religion-, sex- or nationality-based preferences, institute purely merit-based hiring and admissions, open these processes to federal data audits, and run yearly external audits to ensure viewpoint diversity across every academic unit. In addition, Harvard was asked to immediately close all DEI offices, overhaul its disciplinary system, and file regular transparency reports.

Much like the NIH and NSF IDC cuts, the Administration’s DCL, anti-DEI EOs, and proposed anti-DEI legislation threatens institutions across stratified types (e.g., Ivy Leagues, MSIs, or Regional Comprehensive Universities). The anti-DEI policy artifacts, however, deviate from the NIH guidance in two material ways. First, the Administration motivated anti-DEI policy proposals via the construction of a clear beneficiary-threat dyad that positioned DEI as an existential and material threat to the American people writ large and educational quality and merit more specifically. And second, the Administration uses this threat to legitimize dramatic anti-DEI policy proposals that disincentivize collective action by opening the door to voluntary compliance to avoid possible harm.

As an example of how the Administration constructed a beneficiary-thread dyad, the “Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity” EO posits that the “critical and influential institutions of American society, including… institutions of higher education have adopted and actively use dangerous, demeaning, and immoral race- and sex-based preferences under the guise of so-called “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI).”

According to the Administration, DEI diverts government agencies, including ED, from its appropriate goals of quality “ahead of divisive ideology in our schools.”

DEI is thus positioned as materially dangerous as it threatens the role of merit in domains of American society where

“DEIA policies [diminish] the importance of individual merit, aptitude, hard work, and determination when selecting people for jobs and services in key sectors of American society… Yet in case after tragic case, the American people have witnessed first-hand the disastrous consequences of illegal, pernicious discrimination that has prioritized how people were born instead of what they were capable of doing.”

This argumentation asserts, without evidence, that DEI threatens the selection of meritorious individuals across contexts, including roles key to societal safety. And second, this beneficiary-threat dyad motivates a policy proposal best characterized as both intentionally vague and chilling in a way that disincentivizes collective action (see also, Garces et al., 2021). First, DEI as the policy target, and implicitly the institutions that have adopted it, is defined in vague yet menacing terms. For example, DEI policies are described as “[undermining] our national unity, as they deny, discredit, and undermine the traditional American values of hard work, excellence, and individual achievement in favor of an unlawful, corrosive, and pernicious identity-based spoils system.” A characterization made without identifying the specific and structural markers of DEI policies or programs that would be considered indefensible. Importantly, these descriptions are not backed by either evidence or extant laws or policies. The breadth of the Administration’s vague description is a message to institutions that any grants, contracts, programming, language, policy, or position directed in any way at equality, equity, inclusion, or specific populations put institutions in a position of risk for direct cuts (in the case of grants or contracts) or for losing their eligibility for all federal funding.

Our analysis also differentiates these anti-DEI policy mechanisms from those used by the NIH as having an intentionally chilling effect on collective action. The Administration did so by focusing the DCL and the EOs on the threat of vigorous enforcement that can be avoided if institutions comply in advance of potential administrative action. For example, plans for enforcement were described as identifying “the most egregious and discriminatory DEI practitioners in each sector of concern… each agency shall identify up to nine potential civil compliance investigations of… institutions of higher education with endowments over 1 billion dollars.” This threat signals to institutions that at any moment, they could be in the crosshairs to lose federal funding eligibility. And moreover, the emphasis on large-endowment institutions curtails the likelihood that the field’s most high-profile institutions will feel immune to this policy threat.

Building on its moves against Harvard and Columbia to instill direct regulatory pressure, the April 23, 2025, EO entitled “Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education,” foreshadows the Administration’s momentum towards formalizing its anti-DEI sentiments into stable funding criteria. The EO took aim at accreditors’ inclusion in recent years of equity concerns and reporting in their accreditation standards. The Administration framed these standards as deviating from concerns of “quality” and concluded that they must move away from “requiring unlawful discrimination.” The EO goes on to claim that “American students and taxpayers deserve better, and my Administration will reform our dysfunctional accreditation system so that colleges and universities focus on delivering high-quality academic programs at a reasonable price.” In response, the Administration proposes policy to both weaken individual accreditors hold over institutional accountability, tying their hands on the inclusion, to any degree, of equity concerns in their institutional review processes, and conscripting them into carrying out the administration’s anti-DEI agenda by stating that accreditors must require “higher education institutions to provide high-quality, high-value academic programs free from unlawful discrimination.” As we know, unlawful discrimination is being used as a synonym for all equity and justice policy and programs in this context.

IHEs and Advocates Divided and Scared to Say “Racism”

In contrast to IHEs’ more litigious response to the IDC reduction policies, institutions have largely responded to anti-DEI attacks through discursive and material evasion of the threats via compliance--both anticipatory and conciliatory. This compliance moves institutions toward the ultimate goal of the Administration’s attacks by eroding the place of racialized people, curriculum, and programs within IHEs in real time.

While institutions responded both individually and in their legal offensive alongside external advocates by framing threats to IDC funding as detrimental to national wellbeing, they were relatively silent and even hypercompliant in their response to anti-DEI EOs and the DCL. Many institutions included in the sample have now scrubbed or modified DEI-focused programs, jobs, and initiatives from public-facing webpages. The University of Arizona, for example, opted to inventory their “DEIA-oriented… programs, jobs and activities” to immediately move into compliance with the EO’s without significantly questioning their legality stating that

“as a public institution… we are taking a measured approach toward ensuring compliance with new policies and procedures that will impact higher education institutions in the coming weeks and months.”

Compliance-focused responses like Arizona’s were nearly ubiquitous within our sample. Notably, the HBCUs, HSIs, and community colleges in our sample had the fewest DEI-related response documents with no public artifacts on this topic from the HBCUs and community colleges at all. This response, or lack thereof, may be reflective of MSIs’ relative vulnerability to racialized attacks given their dependence on multiple streams of resources that could be identified as DEI-focused and their lesser reserves in the form of endowment funds (McCambly & Aguilar-Smith, 2024). As federal funding maintains inequitable and racialized patterns of grantmaking, especially favoring white serving institutions, racialized institutions are left to fight on multiple fronts.

Among institutions with public responses, we did not find evidence of attempts to construct the policy or the Administration as posing a threat to the institutional mission, functions, or larger community in the way evidenced in responses to IDC rate cuts. Through quiet compliance, institutions offered no alternative policy frame to the Administration’s claim that DEI work had harmed “hardworking Americans” or “qualified candidates” --the implication being that white people and men who do not benefit from DEI policies or programs are inherently more qualified or hardworking. Institutions in the sample have, by and large, accepted the Administration’s anti-DEI EOs and the DCL as legitimate policy and, through acceptance, have to a degree, made them so.

The Administration’s announcement of federal funding freezes at Harvard ($2.2 billion) and Columbia ($400 million) is a startling display of the Administration’s tactics to bring higher education to heel. These funding freezes, and later threats to accreditation, sent a message that not even the most elite IHEs would be exempt from the Administration’s erasure of racialized peoples, programs, and curricula in higher education. While Columbia almost immediately buckled, Harvard put up a fight via both a lawsuit and a series of official public statements in response to the Administration’s attacks. Similar to other IHEs in our sample, Harvard constructed attacks on federal funding as precedent and a detrimental attack on First Amendment rights. In a statement made by the university, Harvard stated, “we have informed the administration through our legal counsel that we will not accept their proposed agreement. The University will not surrender its independence or relinquish its constitutional rights.” In particular, the university evoked language that points to legal and constitutional rights, asserting that the university would continue to

“[N]urture a thriving culture of open inquiry on our campus; develop the tools, skills, and practices needed to engage constructively with one another; and broaden the intellectual and viewpoint diversity within our community; affirm the rights and responsibilities we share; respect free speech and dissent while also ensuring that protest occurs in a time, place, and manner that does not interfere with teaching, learning, and research; and enhance the consistency and fairness of disciplinary processes; and work together to find ways, consistent with law, to foster and support a vibrant community that exemplifies, respects, and embraces difference. As we do, we will also continue to comply with Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which ruled that Title VI of the Civil Rights Act makes it unlawful for IHEs to make decisions “on the basis of race.”

Again, similar to other institutions, the response to anti-DEI policy action is vague and relies on the construction of legal or constitutional rights of a university as the primary point of their resistance.

In contrast to individual institutional responses, several organized and collective responses from the field--including letters, opinions, and calls to action written by state attorneys general, major education professional associations, legal and education experts, and some members of Congress--have pushed back on the administration’s anti-DEI stance. First, advocates across these texts have insisted that DEI programs, curriculum, and language are all legally defensible and have provided in-depth analysis of the narrow circumstances under which this would not be so. These assertions include critiques by the National Education Association of the DCL whose “substance is contrary to the constitutional rights of academic institutions and educators.” Across advocacy documents, we found claims based in both law and empirical evidence that the sweeping accusations at the heart of the Administration’s anti-DEI stances not only run contrary to current laws and policies from ESSA to the separation of powers, but are wholly undocumented. There are also multiple instances across advocacy documents of legal analysis pointing to the overreach of the EO and the misreading of the SFFA verdict. Instead, a collective of state attorneys general specifies that the DCL, for instance,

“incorrectly suggests that it would be unlawful for educational institutions to implement a race-neutral policy in order to increase racial or other forms of diversity. SFFA did not hold race-neutral policies unlawful, and in fact, the Supreme Court has encouraged “draw[ing] on the most promising aspects of . . . race-neutral alternatives” to achieve “the diversity the [institution] seeks”

As such, an alliance of law professors beseeched institutions to remember that “federally funded institutions should not, however, interpret the J21 EO and related communications as requiring the elimination or curtailment of existing DEI initiatives.” Indeed, this same cadre of law professors makes the point that the DCL and the anti-DEI EOs rest on a premise that could itself violate civil rights law. The open letter argues that the administration

“[B]lames ‘illegal DEI and DEIA policies’ for ‘case after tragic case’ of unspecified catastrophe leading to “disastrous consequences.” This language invokes the talking point that DEI is responsible for essentially every human-made disaster and relies on the empirically fraught claim that DEI policies, because they attend to identity and promote inclusion, compromise ‘merit’ by placing women and Black people into positions for which they are ‘unqualified.’ This theory, in turn, rests on the stereotype that women and Black people are presumptively incompetent and intellectually inferior to white men.”

Across advocacy artifacts, we see arguments that point out both the illegality and the fundamentally racialized nature of the anti-DEI attacks as an attempt by the Administration to eradicate equal opportunity programs and silence academics in ways that are likely to either silence or push students, faculty, and staff of color off of college campuses.

Critically, outside of the NEA’s lawsuit filed by the ACLU and the letter written by members of Congress asking ED to rescind the DCL, the remaining advocacy documents are largely aimed at beseeching IHEs not to silently comply with these anti-DEI directives. Indeed, the Administration’s use of EOs and the DCL effectively circumvented institutionally accepted modes of policy change, taking the fight directly to the door of individual higher education institutions. As such, advocacy organizations can call for the Administration to rescind these documents, but without institutional refusal or resistance, these edicts, even if not formally legitimate, are nonetheless effective racialized policymaking. To this end, we also analyzed one of the few organized, united responses from higher education leaders--an open letter from the Association of American Colleges & Universities signed by over 200 university presidents. While this statement advocated for “open inquiry” and the “pursuit of truth” and asserted postsecondary institutions as “essential to American prosperity,” it failed to name the Administration’s threats to DEI work nor did the letter assert the right or intention of institutions to maintain racial equity or justice in their missions. Not only were statements of commitment lacking, but many of the signatories had already materially rolled back DEI commitments on their own campuses.

Discussion and Conclusion

Prior studies of (e)quality politics have found that regressive policy attacks focused on threats to educational quality or merit work to reestablish or crystallize institutional stratification via the concentration of resources at elite, white institutions. Our findings reveal a significant shift in the operation of this backlash. Rather than maintaining white supremacy by hoarding resources and prestige via racialized stratification, the Administration’s contemporary anti-DEI project is organized around a systemwide purge targeting even nominally antiracist programs, scholarship, leadership, curriculum, and policy across all institutional types, from Ivy League universities to HBCUs to community colleges (see

Figure 1). In this way, the current backlash is not simply about where resources flow, but about which ideas, people, and political commitments are allowed to exist at all within the ivory tower.

(E)Quality Politics Then and Now

By analyzing the proposed IDC caps as a parallel, non-racialized policy threat, we further demonstrate that the Administration’s anti-DEI strategy represents a distinct ideological formation. Research universities successfully mobilized collective resistance to the proposed funding caps by framing the policy as a threat to national well-being, scientific capacity, and the public good. In sharp contrast, institutional responses to anti-DEI attacks have largely failed to produce an equally compelling counternarrative to the Administration’s framing of DEI as a threat to excellence, merit, and fair opportunity for the “everyman.” This asymmetry is not accidental—it reflects a historically familiar vulnerability in equity policymaking, in which institutions retreat rather than contest the racialized redefinition of quality.

Situating the current moment as a new instantiation of (e)quality politics provides crucial analytic leverage. The framework clarifies how today’s attacks can be understood as part of a four-stage pattern of racialized backlash, while also revealing what is newly dangerous about the present configuration. We argue that we are now firmly in the third stage of (e)quality politics, in which regressive actors work to delegitimize prior equity “wins” through unsubstantiated claims that justice-oriented reforms undermine quality and excellence. Historically, this stage has paved the way for the fourth: the institutionalization of whiteness as the implicit standard of educational quality through policy design that never explicitly names race. In earlier eras, this logic allowed elite white institutions to serve as the silent benchmark through which racialized advantages were secured via ostensibly neutral standards. As others have theorized, it is precisely this process—the institutionalization of whiteness as credential and as property—that hardens backlash into durable policy regimes (e.g., Ray, 2019; Harris, 1993; McCambly et al., 2024; Wooten & Couloute, 2017).

Yet, our analysis also identifies critical departures from the “typical” (e)quality politics trajectory that redefine both the risks and the possibilities of the present moment. First, the Administration is bypassing conventional legislative and judicial pathways by taking the fight directly to institutions through executive action, funding eligibility rules, and accreditation pressures—effectively circumventing constitutional checks and balances. Second, whereas earlier deployments of (e)quality politics sought to deepen white supremacy through stratification across institutional tiers, the contemporary strategy seeks to eliminate equity-oriented programming, knowledge, and personnel across all sectors of higher education. And indeed, this is a reflection of the nature of the equity expansion that sparked this backlash--the expansions of epistemological and axiological inclusion of the late 2010s and early 2020s.

Extending the framework of repressive legalism (Garces et al., 2021; Pedota et al., 2025), we find that the Administration deliberately weaponized vagueness and coercion to fracture institutional solidarity and preempt collective resistance, but only in the racialized policy domain. Proposed IDC cuts, for example, posed an indiscriminate and structurally uniform threat to all IHEs dependent on federal funding from NIH, NSF, and other agencies—conditions that enabled rapid, coordinated opposition. By contrast, the Administration’s anti-DEI campaign relied on intentionally vague, legally tenuous, and overtly fear-producing threats. Institutions were first placed on notice through the DCL, then subjected to the trauma of grant claw backs targeting DEI-related scholars and programs as unscientific and non-meritorious, and finally confronted with the execution of direct, unconstitutional funding freezes at high-profile universities. These escalating moves staged a series of standoffs in which the federal government positioned itself as holding unilateral power, deliberately signaling that no institution would be spared.

Through this manufactured climate of legal uncertainty and economic terror, the Administration used (e)quality political logics as its foundation for the construction of a racialized compliance regime. Under such a regime, funding and accreditation eligibility would hinge on emergent metrics and standards of ideological “neutrality” engineered to expel the very people, programs, policies, and expertise that would otherwise sound the alarm on this false neutrality as a guise for white supremacy. The result is not merely regulatory pressure, but a strategy designed to make institutions too isolated, too exposed, and too afraid to act—precisely when collective resistance is their only meaningful defense.

This transformation marks a critical escalation. If these racialized compliance metrics become normalized as permanent features of federal grants eligibility and accreditation, then the Administration’s racial ideology—and its violations of First Amendment protections—will be effectively institutionalized as the new status quo of U.S. higher education governance. The implications extend far beyond diversity offices or a subset of academic programs. What is at stake is whether IHEs retain any meaningful capacity to define their contributions and commitments to educational quality, scientific excellence, the public good, and advancing a more just and inclusive society independent of authoritarian political control.

With these insights, we issue a field-wide call to action. Institutions must move beyond individualized risk management and develop a collective, public articulation of equity and justice as essential—not optional—to the democratic purpose of higher education. And here, we argue, is where leaders must resist and refuse both the false narratives that expanding equitable policies and access to racialized expertise in scholarship and classrooms erodes educational quality, as well as the funding and grant eligibility metrics that would institutionalize these ideas into durable structures. Equally important, we argue that in the current repressive legalistic context, quiet compliance is itself a regressive policy act. History shows that the greatest victories of (e)quality political backlash have not emerged solely from external coercion, but from institutional acquiescence that allows backlash to sediment into ordinary governance. Refusing that sedimentation—through coordinated resistance, clear counternarratives, and public defense of equity as a public good—is now the central task before the field.

Appendix A

Collected Federal Documents and Non-IHE Public Responses

Federal Documents

| Date |

Title |

Institution/Author |

Public Access |

| 12-Jun-24 |

Senate Bill 4516: Dismantle DEI Act of 2024 |

U.S. Congress |

https://www.congress.gov/index.php/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4516/text |

| 20-Jan-25 |

Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing |

White House |

https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/ending-radical-and-wasteful-government-dei-programs-and-preferencing/ |

| 21-Jan-25 |

Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity |

White House |

https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/ending-illegal-discrimination-and-restoring-merit-based-opportunity/ |

| 22-Jan-25 |

Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Protects Civil Rights and Merit-Based Opportunity by Ending Illegal DEI |

White House |

https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/01/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-protects-civil-rights-and-merit-based-opportunity-by-ending-illegal-dei/ |

| 23-Jan-25 |

U.S Department of Education Takes Action to Eliminate DEI |

Department of Education |

https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/us-department-of-education-takes-action-eliminate-dei |

| 4-Feb-25 |

Cloud and Schmitt Introduce Bill to Codify into Law Trump's Agenda Ending DEI in Federal Government |

Michael Cloud (RTX-27) and Eric Schmitt (R-MO) |

https://www.schmitt.senate.gov/media/press-releases/senator-schmitt-congressman-cloud-introduce-the-dismantle-dei-act/ |

| 7-Feb-25 |

Supplemental Guidance to the 2024 NIH Grants Policy Statement: Indirect Cost Rates |

National Institutes of Health |

https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-25-068.html |

| 14-Feb-25 |

Dear College Letter on SFFA v. Harvard |

Department of Education |

https://www.ed.gov/media/document/dear-colleague-letter-sffa-v-harvard-109506.pdf |

| 3-Mar-25 |

HHS, ED, and GSA Announce Additional Measures to End Anti-Semitic Harassment on College Campuses |

U.S General Services Administration |

https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/newsroom/news-releases/hhs-ed-and-gsa-announce-additional-measures-to-end-antisemitic-harassment-03032025 |

| 11-Mar-25 |

Letter to the Community |

Sethuraman Panchanathan, Director, U.S. National Science Foundation |

https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/files/Letter-to-the-Community.pdf |

| 13-Mar-25 |

Letter to Columbia |

U.S. General Services Administration |

https://president.columbia.edu/sites/president.columbia.edu/files/content/ltr.gsa_.hhs_.doe_.3-13-25.pdf |

| 11-Apr-25 |

Letter to Harvard |

U.S. General Services Administration |

https://www.harvard.edu/research-funding/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2025/04/Letter-Sent-to-Harvard-2025-04-11.pdf |

| 23-Apr-25 |

Reforming Accreditation to Strengthen Higher Education |

White House |

https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/reforming-accreditation-to-strengthen-higher-education/ |

| 2-May-25 |

NSF Policy Notice: Implementation of Standard 15% Indirect Cost Rate |

National Science Foundation |

https://www.nsf.gov/policies/document/indirect-cost-rate |

Non-IHE Public Responses

| Date |

Title |

Institution/Author |

Public Access |

| 10-Feb-25 |

Association of American Universities v. Department of Health & Human Services |

Association of American Universities, American Council on Education, Association of Public and Land Grand Universities, and 15 University Co-Plaintiffs |

https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/AAU-ACE-APLU-Complaint-NIH-Funding.pdf |

| 20-Feb-25 |

DEI Programs Are Lawful Under Federal Civil Rights Laws and Supreme Court Precedent |

A Coalition of Law Professors |

https://race.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Law-Professors-DEI-Executive-Orders-Memo.pdf |

| 25-Feb-25 |

Letter to ED on Behalf of Higher Education Associations in Response to the DCL |

American Council on Education and other Association Signatories |

https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Letter-ED-DCL-022525.pdf |

| 27-Feb-25 |

Letter to ED in Opposition to the Dear Colleague Letter |

Representative Summer Lee (D) and other Members of Congress Signatories |

https://summerlee.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/summerlee.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/rep-lee-letter-to-ed-ocr-re-dear-colleague-letter.pdf |

| 5-Mar-25 |

Letter to Institutions of Higher Education and K-12 Schools regarding recent EO and DCL |

The Offices of the Attorney General for the State of Illinois, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the State of New York |

https://illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/News-Room/Current-News/March%205%202025%20Updated%20Joint%20Guidance%20re%20School%20Programs%20Multistate.pdf?language_id=1 |

| 5-Mar-25 |

National Education Association v. United States Department of Education |

National Education Association |

https://www.aclu.org/cases/national-education-association-et-al-v-us-department-of-education-et-al?document=Complaint#legal-documents |

| 17-Mar-25 |

Letter to ED Questioning Massive Reduction in ED Workforce |

Patty Murray, Tammy Baldwin, and Roasa L. DeLauro, Members of Congress in their capacities of Committe on Appropriations |

https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/250317_letter_to_ed_final_re_rifs.pdf |

| Downloaded on 18-Mar-25 |

National DEI Defense Coalition Website and Materials |

Shaun Harper & Associates, University of Souther California Race & Equity Center |

https://race.usc.edu/coalition/ |

| 22-Apr-25 |

A Call for Constructive Engagement |

Association of American Colleges & Universities and University President Signatories |

https://www.aacu.org/newsroom/a-call-for-constructive-engagement |

| 25-Apr-25 |

A Deeper Dive: Background on Accreditation and President Trump’s Executive Order |

Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions |

https://www.c-rac.org/post/accreditors-react-to-president-trump-s-latest-executive-order-targeting-college-oversight |

| 5-May-25 |

Association of American Universities v. National Science Foundation |

Association of American Universities, American Council on Education, Association of Public and Land Grand Universities, and 13 University Co-Plaintiffs |

https://www.aau.edu/key-issues/legal-filings-submitted-aau-aplu-ace-and-13-universities-contesting-cuts-nsf-research |

References

- Anderson, G. M. Equity and critical policy analysis in higher education: A bridge still too far. The Review of Higher Education 2012, 36(1), 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. J. Pathways to Racial Equity in Higher Education: Modeling the Antecedents of State Affirmative Action Bans. American Educational Research Journal 2019, 56(5), 1861–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. J.; Shook, L. M.; Ramirez-Mendoza, J.; Bennett, C. T. Race below the fold: Race-evasiveness in the news media’s coverage of student loans. In EdWorkingPapers.com; Annenberg Institute at Brown University, 2023; Available online: https://edworkingpapers.com/index.php/ai23-771.

- Bastedo, M. N.; Gumport, P. J. Access to what? Mission differentiation and academic stratification in U.S. public higher education. Higher Education 2003, 46(3), 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastedo, M. N.; Jaquette, O. Running in place: Low-income students and the dynamics of higher education stratification. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 2011, 33(3), 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume-Kohout, M. E.; Kumar, K. B.; Sood, N. University R&D funding strategies in a changing federal funding environment. Science and Public Policy 2015, 42(3), 355–368. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, W. C. The Higher Education Act and minority serving institutions: Towards a typology of Title III and V funded programs. Education Sciences 2018, 8(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, K. L.; Garces, L. M.; Johnson, R. M. Introduction: Countering Legislative Attacks on Higher Education: Challenges, Strategies, and Future Directions. The Journal of Higher Education 2025, 96(7), 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Y.; Kahanamoku, S. S.; Tripati, A.; Alegado, R. A.; Morris, V. R.; Andrade, K.; Hosbey, J. Decades of systemic racial disparities in funding rates at the National Science Foundation

. OSF Preprints 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical discourse analysis and critical policy studies. Critical Policy Studies 2013, 7(2), 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M. M. The price of Civil Rights: Black lives, White funding, and movement capture. Law & Society Review 2019, 53(1), 275–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidus, A. Segregation, Diversity, and Pathology: School Quality and Student Demographics in Gentrifying New York. In Educational Policy; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Freidus, A.; Ewing, E. L. Good Schools, Bad Schools: Race, School Quality, and Neoliberal Educational Policy. In Educational Policy; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garces, L. M.; Johnson, B. D.; Ambriz, E.; Bradley, D. Repressive legalism: How postsecondary administrators’ responses to on-campus hate speech undermine a focus on inclusion. American Educational Research Journal 2021, 58(5), 1032–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasman, M.; Nguyen, T. H.; Conrad, C. F. Lives intertwined: A primer on the history and emergence of minority serving institutions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 2015, 8(2), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J. P. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 2004. [Google Scholar]