1. Introduction

Cancers such as Melanoma (Mel) and Bladder Cancer (BC) might not be comparable cancers but on closer perusal it may be confirmed that there is a relatively high mutational burden shared by these 2 tumors with BRAF (B-rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma) and MEK (mitogen-activated kinase) also known as Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase and MAP2K, an alternative pathway in Mel [

1]. Other pathways involved in Mel include uveal GNA11, GNAQ; KIT or NRAS protein (mucosal and skin) (

https://www.curemelanoma.org/blog/mutations-and-melanoma) accessed 8/6/25. In the broader context, there are many actionable mutations in BC including FGFR3; Nectin 4; TROP-2; Micro satellite instability (MSI); GATA3, FOXA1 FGFR3, CK20, Uroplakin-2; Vimentin, desmin, SMA; CK5/6, CK14, Desmoglein 3, STAT3; INSM1, Synaptophysin, Chromogranin, CD56 and many others for targeting, depending on the tumor subtype [

2]. The aim of the work was to use novel innate immune system (InImS) biomarkers like the FERAD ratio (blood ferritin:p87fecalexpression) and acknowledged prognostic markers such as the neutrophil:leukocyte ratio, to establish a biological role within specific cancer types known to be related to the InImS. The initial attempts at using immunotherapy were slow to advance, published in 1974 [

3] after energetic attempts to use immune stimulants such as BCG and 2,000µg of dinitrochlorobenzine (DNCB) to evoke delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. A number of study investigators were able to consistently achieve a complete regression in 15-25% of melanotic nodules after direct injection with DCNB or tuberculin [

3]. This was reproduced by other participants using BCG [

4,

5,

6] with 90% regression of injected lesions and 17% of un-injected lesions in immunocompetent study participants. One quarter of these patients remained disease-free for 1-6 years. It was felt that stage 2 patients had a better survival rate but because patients were not randomized, the results were not judged to be definitive. BCG was the first agent successfully used in these two tumors, but we did not have any patient data as our study was conducted largely in the ICI era. However, the FERAD ratio is unique and correlating it with the older NLR prognostic marker did afford some validation.

In our current study, we found that there is a inverse correlation of the FERAD ratio and NLR in patients with diverse cancers [

7]. In that paper we found that there was a trend between PDL-1 response and the FERAD ratio, and a direct and significant correlation between shed p87 and p87 band intensity in the stool. This article also showed a direct correlation of NLR with the 5-year survival rates in patients without distant metastasis with Mel or BC.

2. Materials and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval we publicized a study with a recruitment goal of 2,500 patients based on a questionnaire that was heavily weighted to enroll patients at above average risk for colorectal cancer (CRC). We advertised this study (Non-invasive Prediction of Colorectal Neoplasia-NIPCON) and published the results in 2023 [

8]. Over the course of almost 3 decades 1995 to 2022, we enrolled over 2,200 patients at high risk of CRC and prospectively noted those who contracted malignancy on follow up. We compared the historic, premorbid biomarker response from the time of enrolment, primarily using the FERAD ratio. This ratio was derived by dividing the plasma ferritin concentration by the denominator of the p87 fecal shedding of a Paneth cell marker. We compared the FERAD response to the absolute neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a well-known prognostic biomarker as described above. As a surrogate OvCa population, we mainly used first degree relatives of OvCa, and to a lesser extent Mel patient relatives, a novel approach. Amongst the controls few patients developed CRC, approximately 2%.Unfortunately, markers like BRACa1 were not available, neither did we collect data on the clinical staging of other cancers before and after treatment or the types of therapeutic interventions.

2.1. Sample Collection

Briefly, stool and other bodily fluids(effluent (colonic washings), saliva, and urine, were obtained after obtaining written informed consent after the participant read the document and then signed the form. The inclusion criteria were an ability and willingness to participate in a long-term observational study, to undergo a colonoscopy ordered by a primary-care provider (PCP). There was also a phase-2 part of the study where 10% of enrollees were asked to allow us to obtain regional biopsies from their colons taken by a cold forceps biopsy for immunohistochemistry and non-fixed tissue extraction. The timing of the 2nd colonoscopy was left to the shared discretion of the PCP and the patient. Thus, the intervals for voluntary procedures differed widely but almost 50% of the enrollees complied and the average between the intervals was 10.8 years.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

These were based on a reasonable state of health of the patient that otherwise may have excluded the possibility of a colonoscopy, including the inability to inscribe the date on the stool cards, or not to be in compliance with the study protocols. Colonic washings (also referred to as effluent) were collected at the time of the endoscopy from rectal pooling.

2.3. Storage and Other Samples

Salivary and urinary samples were also collected and all samples, where appropriate, were stored at −70 °C. We were able to show in our preliminary reports that stored samples gave identical results after 10 years of storage [

7]. We were also able to show that the p87 protein was not adversely affected after being held at room temperature for 6 days. This was important as most participants mailed in their stool cards and the outer limit of mail delivery in our locale was 5 days.

2.4. ELISA

(Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay) and Antibodies: The ELISA was performed in accordance with the manufacturers’ directions and involved the determination of the protein content of stool diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) which allowed us to plate 5μg of protein per well of a 96-well (Nunc microtiter plate Catalogue GS-120030 from Oldsmar, FL, USA). The microtiter plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C and the Adnab-9 antibody (titer dilution 1:500) that recognizes the p87 antigen was placed on half of the plate which had been blocked overnight with a 5% bovine serum albumin solution. All washes between the primary and secondary antibodies were performed with PBS and 5% Tween-20 (MilliporeSigma, Catalogue 93773, Burlington, MA, USA). The reagents were supplied by Vector Laboratories (Catalogue SA-5014-1, Newark CA, USA) for immunohistochemistry by the ABC technique using the manufacturer’s instructions, The ELISA was developed by adding 40 μL of p-nitro-phenyl phosphate (MilliporeSigma, Catalogue N7653, Burlington, MA, USA) to develop a yellow color that was read on a Thermo-Fisher cyto-spectrophotometer at 405 nm. The negative control antibody, UPC10 (MilliporeSigma, Catalogue M9144, Burlington, MA, USA), was an indifferent antibody with the same isotype (IgG2a) as the Adnab-9 monoclonal, was used on half the microtiter plate to determine the background. The results were expressed as the optical density (OD) minus the background. For the serum assay using in-house samples as performed by Clinical Genomics (Macquarie Park NSW 2113,Australia). An indirect ELISA the monoclonal Adnab-9 antibody was used as a 1:500 dilution and a secondary HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG antibody was used as a 1:1000 dilution.

3. Results

Table 1 below displays the known demographics of the 3 groups analyzed.

We were also interested in the familial aspects of BC, Mel and OvCa shown in

Table 2 below.

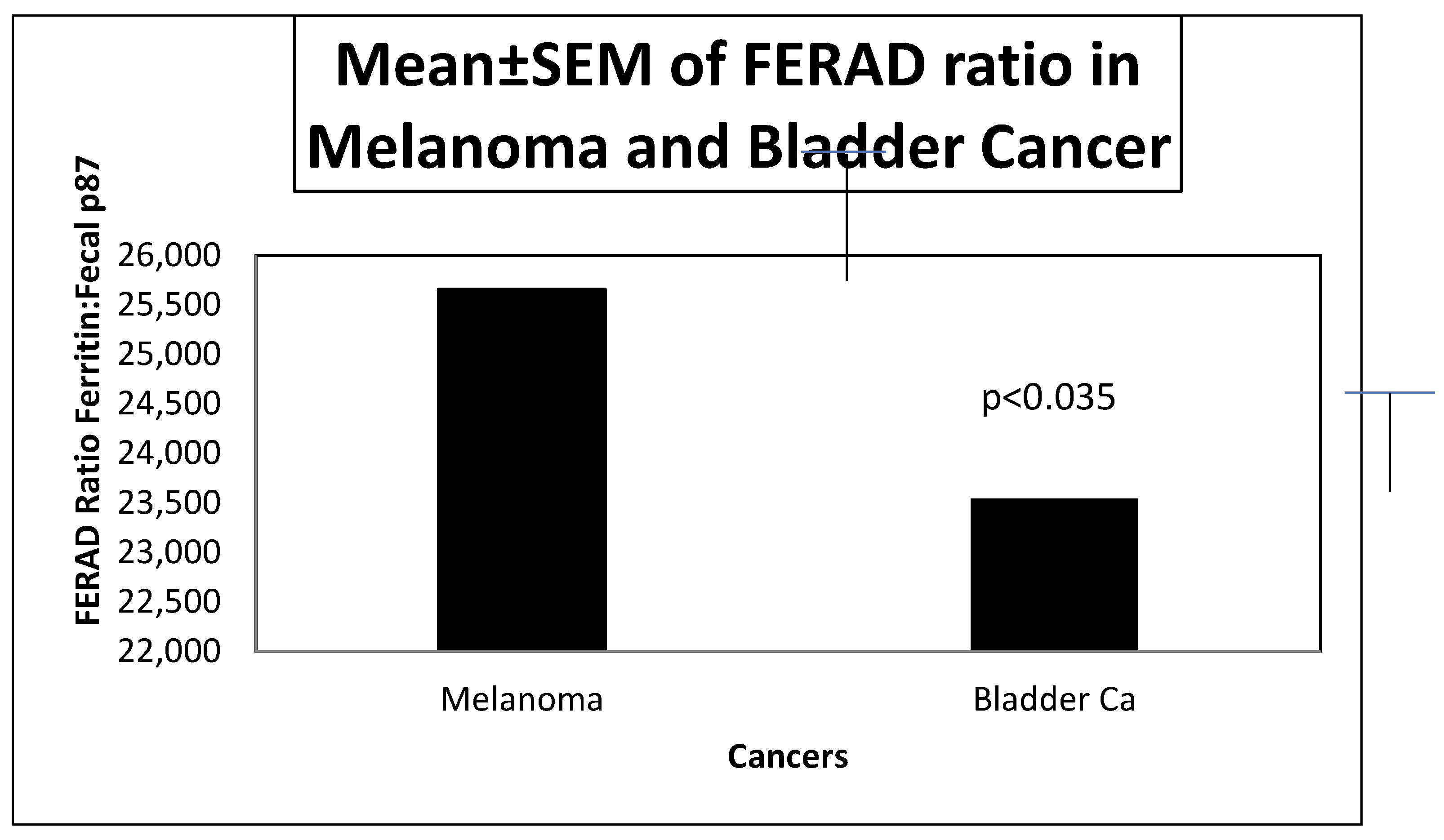

We compared FERAD ratios in BC and Mel patients as these cancers are closely related to the InImS (see

Figure 1 below.)

The figure shows that there is statistical significance between the mean FERAD ratios in BC and Mel.

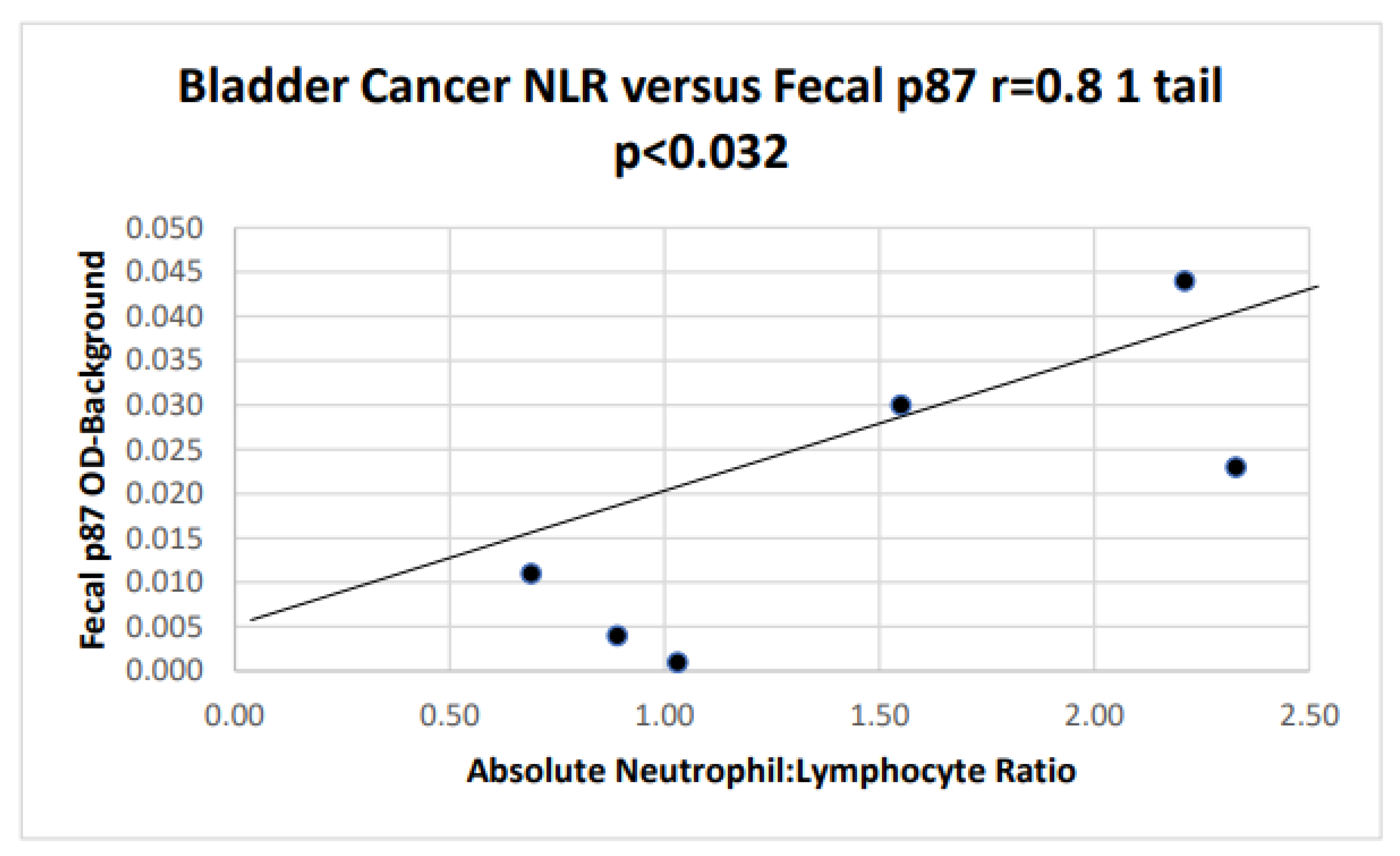

We compared fecal p87, the denominator component of FERAD with the absolute neutrophil:absolute lymphocyte ratio (NLR) to for biomarker survival correlations (

Figure 2).

When NLR and fecal p87 are correlated in patients with BC and Mel, the relationship is. The patients were depicted only if data was available for both p87 and NLR, hence the relatively small number. The patients were not randomly selected.

The composite graph data are drawn from all patients with the requisite paired data

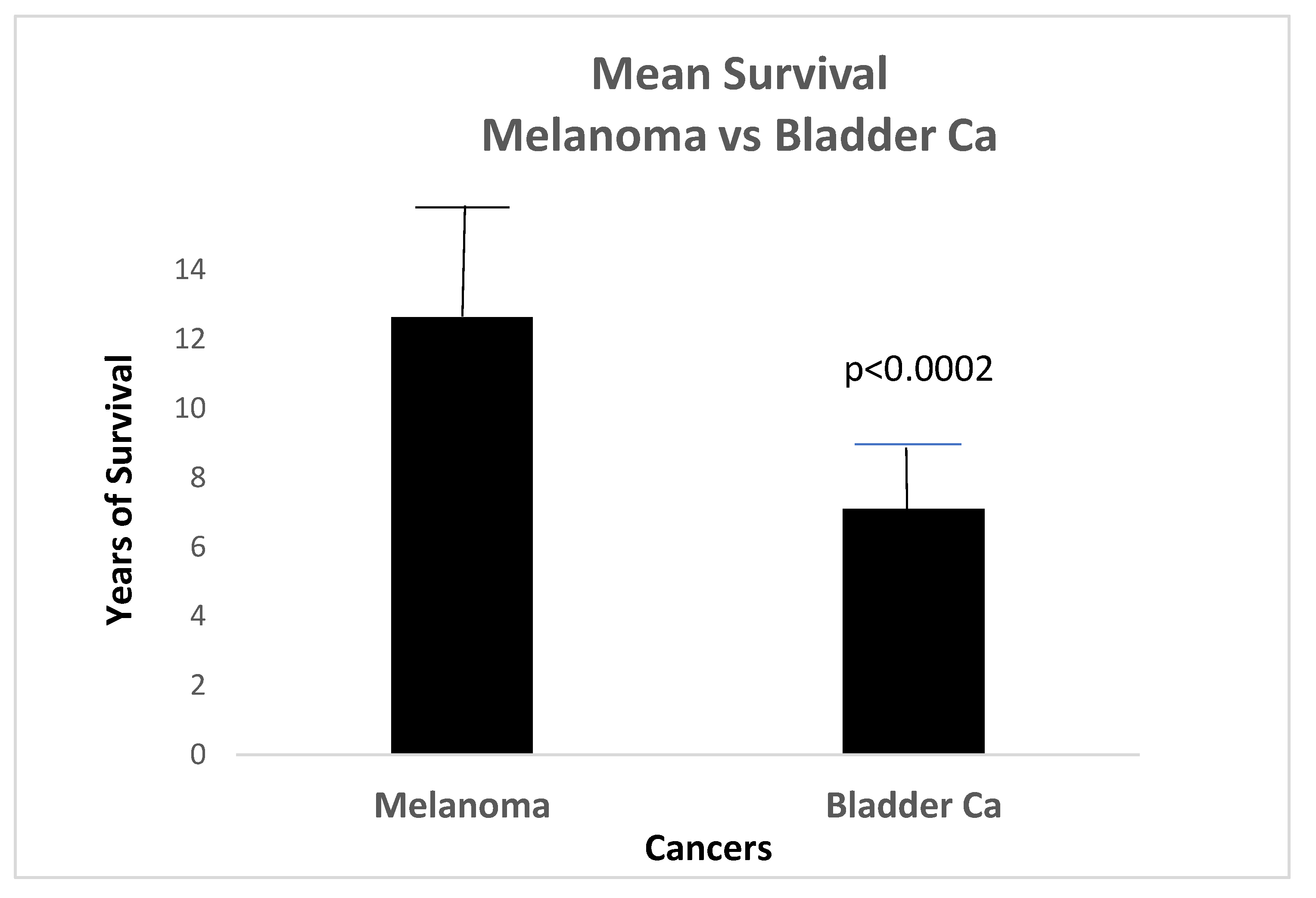

Our data from the available database showed a higher survival rate in patients with Mel than BC as can also be seen in

Figure 3 with additional insights in

Table 1.

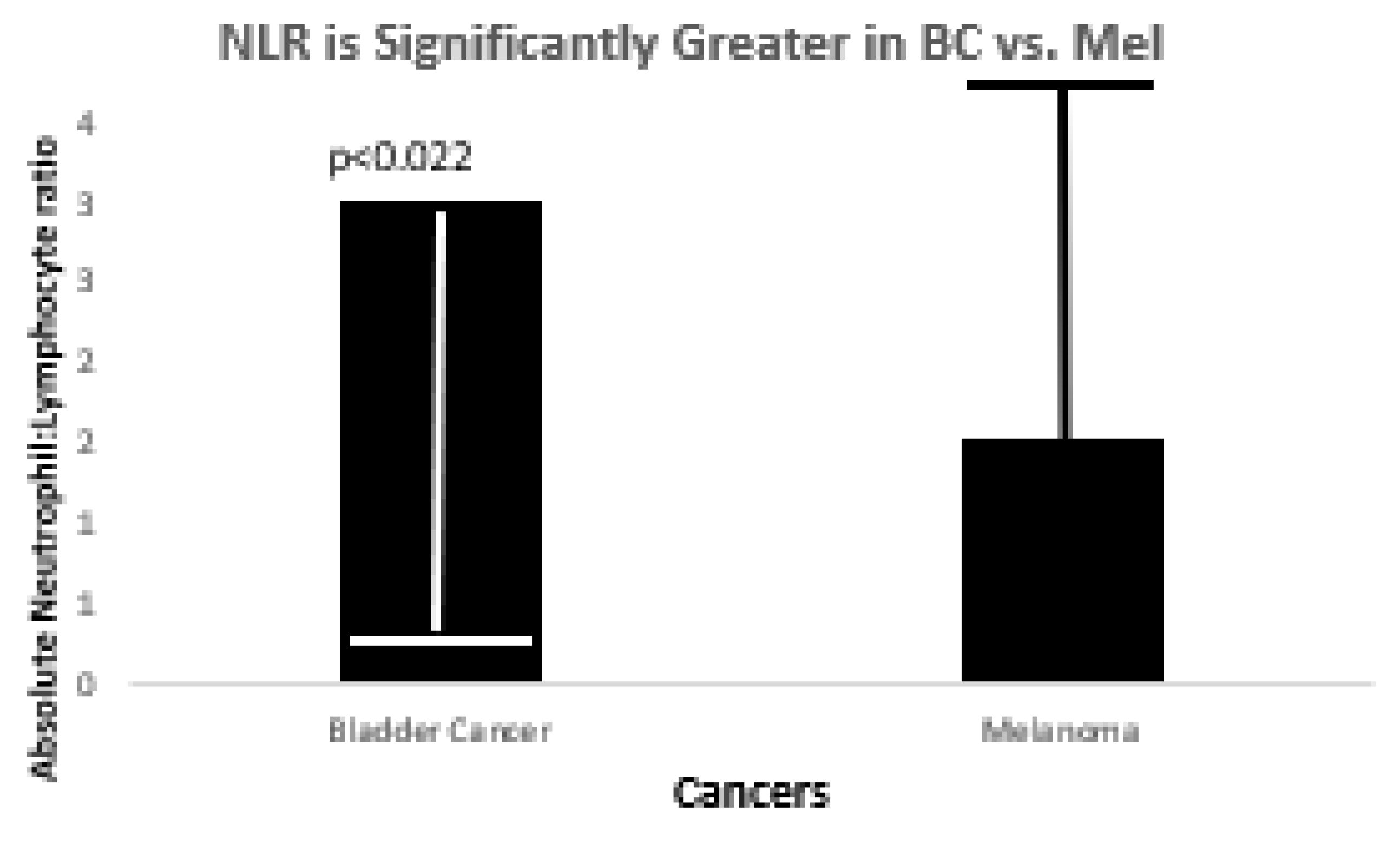

In light of the facts that ICI therapy has boosted Mel survival in the modern era to >93%, we wished to show the prognostic ability of NLR ratio in this scenario shown below in

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A Bar Diagram Showing the Significant Depiction of NLR Ability to Prognosticate in BC.

Figure 4.

A Bar Diagram Showing the Significant Depiction of NLR Ability to Prognosticate in BC.

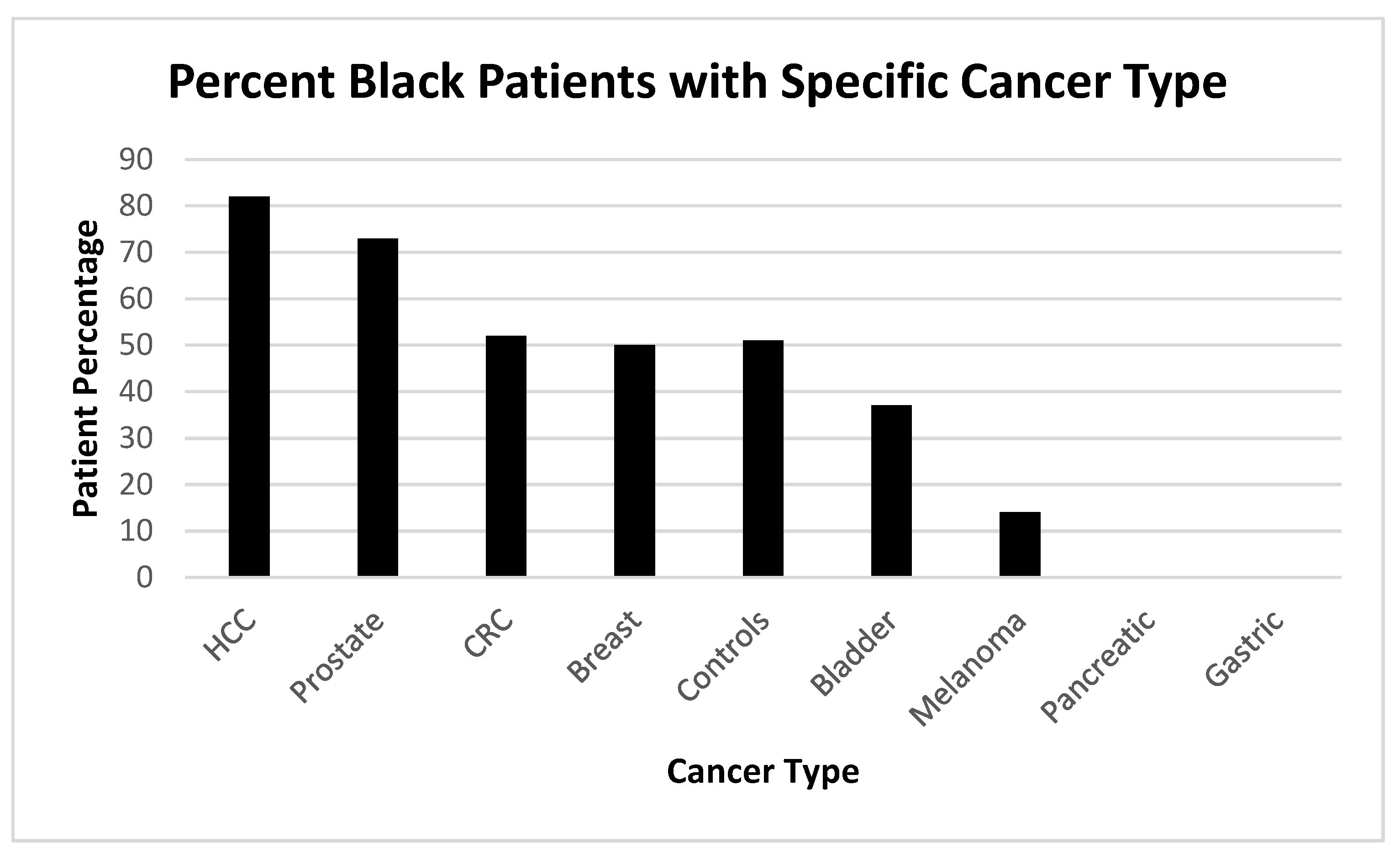

Figure 5.

shows the Spectrum of Prevalence of Cancers Within the Black Population.

Figure 5.

shows the Spectrum of Prevalence of Cancers Within the Black Population.

Given the results in these cancers and we sought to demonstrate the cancers that effect our relatively large demographic of Black patient as can be seen below in

Figure 8.

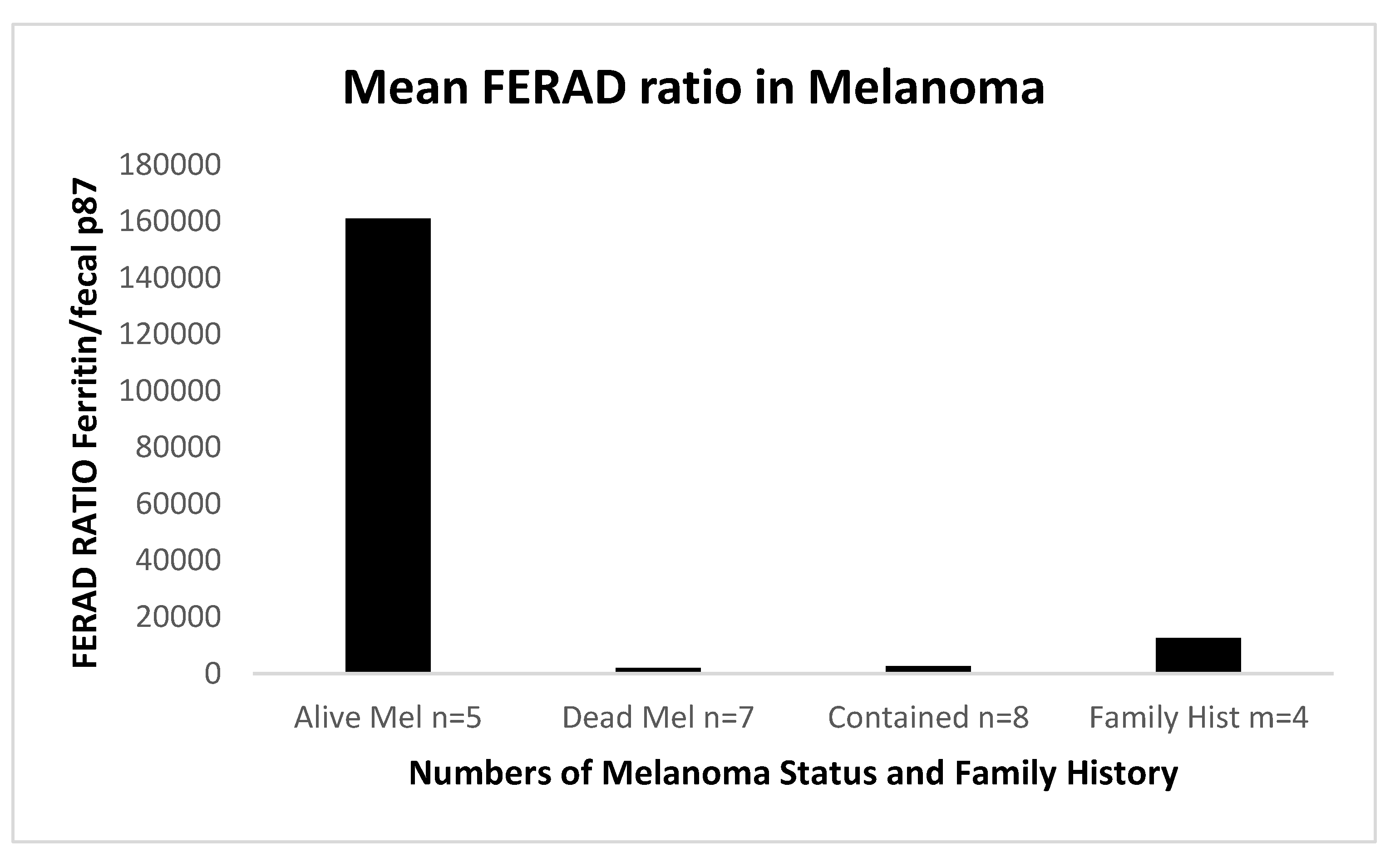

In comparing the various response of the FERAD ratio to Mel, we were able to show that patients treated and doing well with ICI had higher FERAD ratios than those who died. This was not different than the patients whose disease was “contained” but still had some residuum of disease, with very low levels in patients without disease but having a family history as shown in

Figure 6 below.

Table 2 also provides some insights.

Currently, five surviving melanoma patients had the highest values. This may bode well when immune checkpoint inhibition therapy is applied. Theoretically, keeping p87 low may help sustain a high FERAD ratio, which may be beneficial. Vitamins such as folates may lower p87 when taken in doses of 5mg/day rather than the usual 1mg [

9]. A search of the literature shows that this vitamin group is recommended for melanoma, but obviously this will not replace the usual chemotherapy and/or PD-L1 treatment, a current mainstay. On the other hand, turmeric can also be found recommended in the literature, but this supplement increases p87 and may theoretically reduce FERAD values.

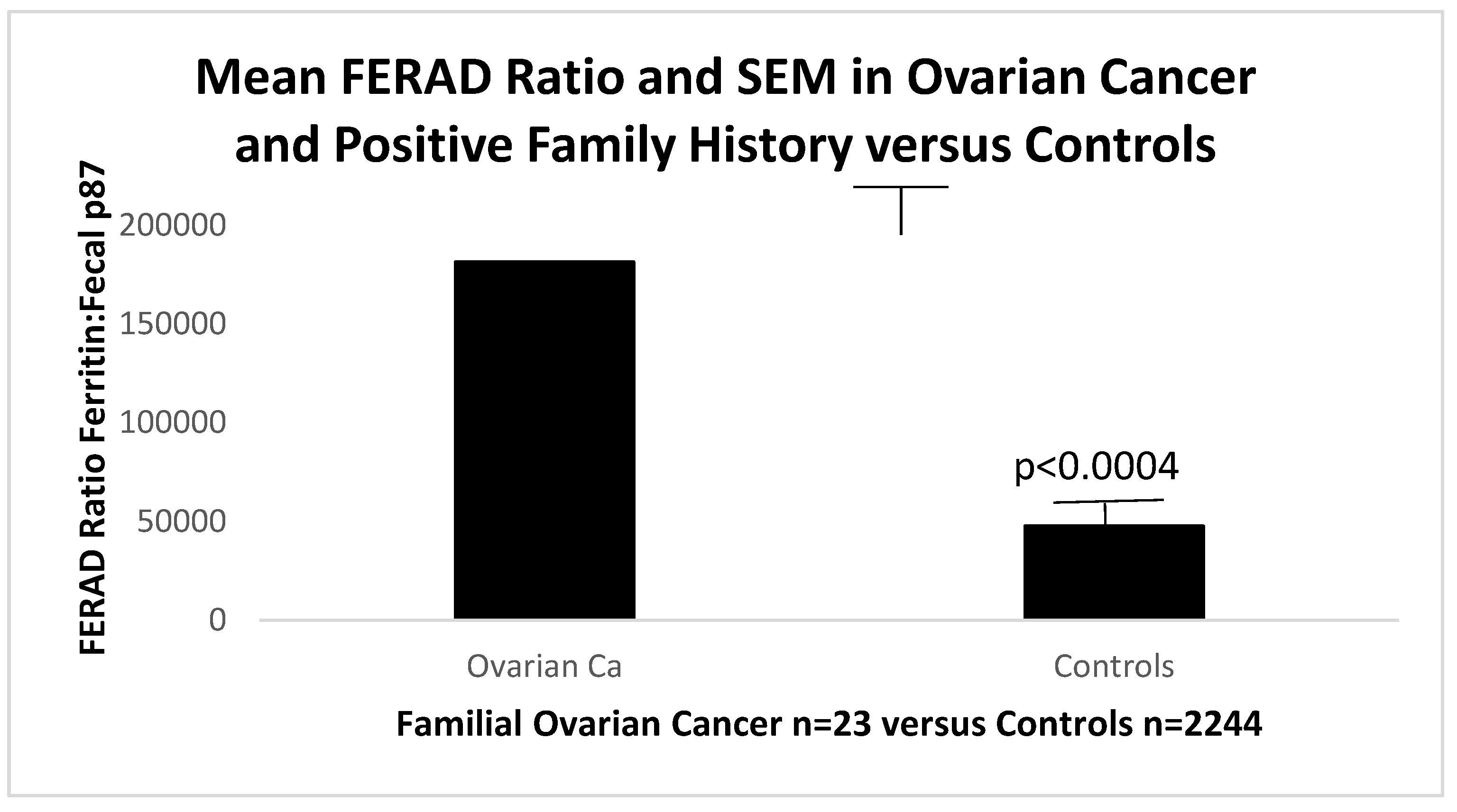

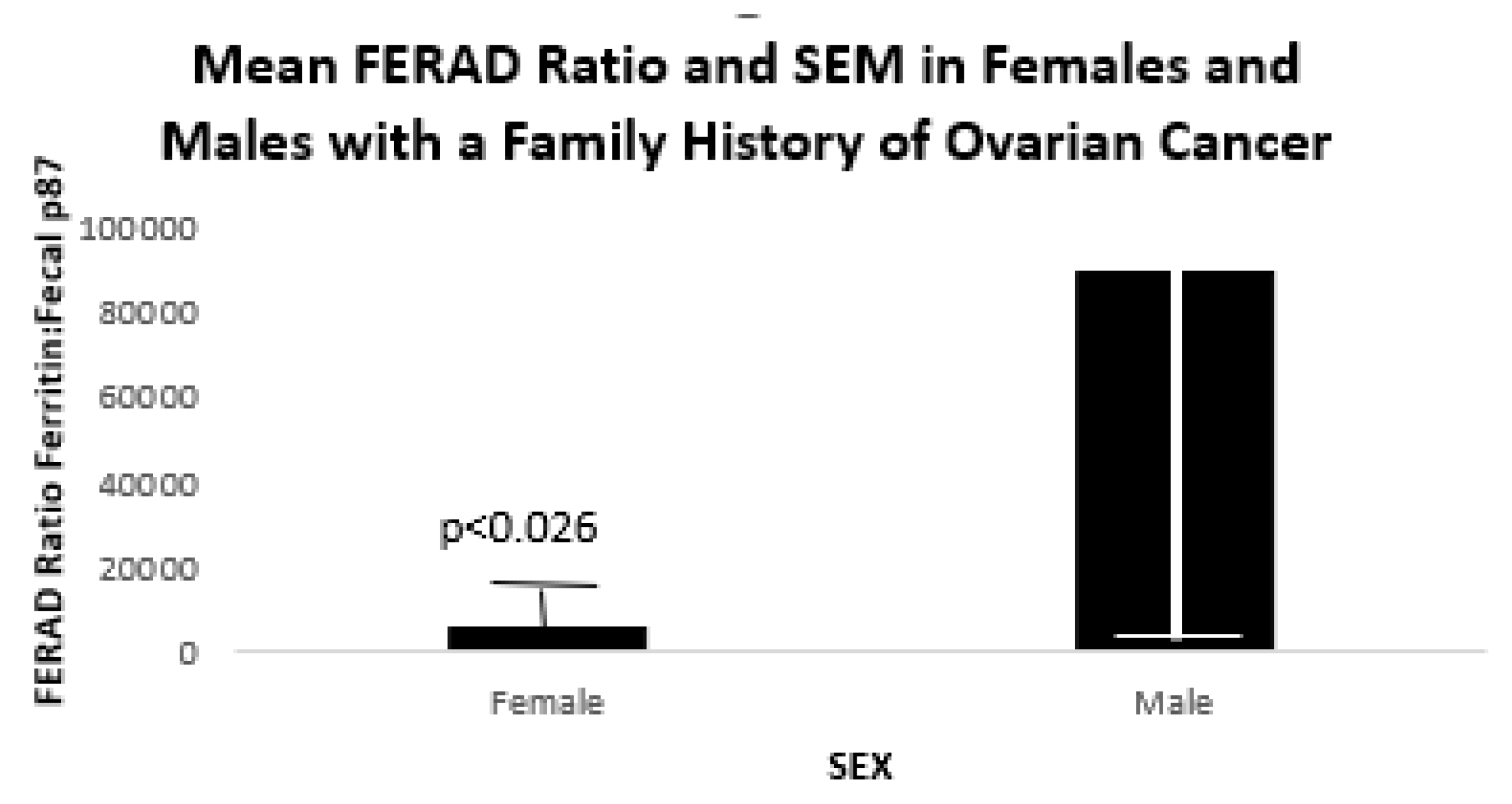

Figure 7 below shows FERAD ratios in 5 female and 17 male patients with a familial history of OvCa.

We also looked at ferritin levels and found that ferritin levels differed in relatives by only a trend p=0.09 in patients with OvCa family history versus controls. The mean and standard deviations were 297±281 192±249 in controls, respectively.

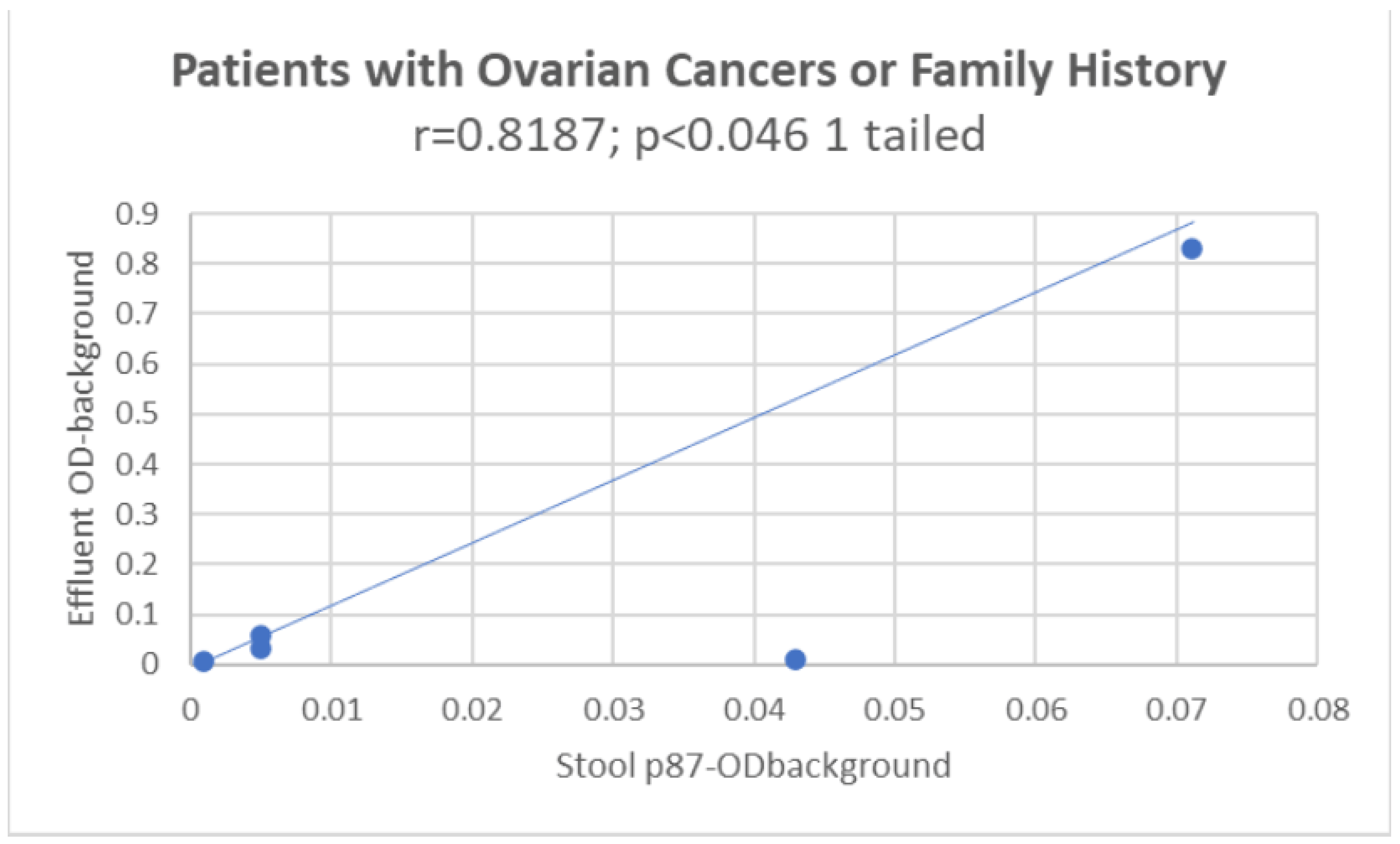

Figure 8 shows a positive direct correlation between p87 in the colonic effluent and stool.

We were also able to show that the FERAD ratio in patients with a family history of OvCa had a significantly higher FERAD ratio than controls.

Figure 9.

The Bar Diagram Shows Patients with OvCa Family History Have a Higher FERAD ratio than Controls.

Figure 9.

The Bar Diagram Shows Patients with OvCa Family History Have a Higher FERAD ratio than Controls.

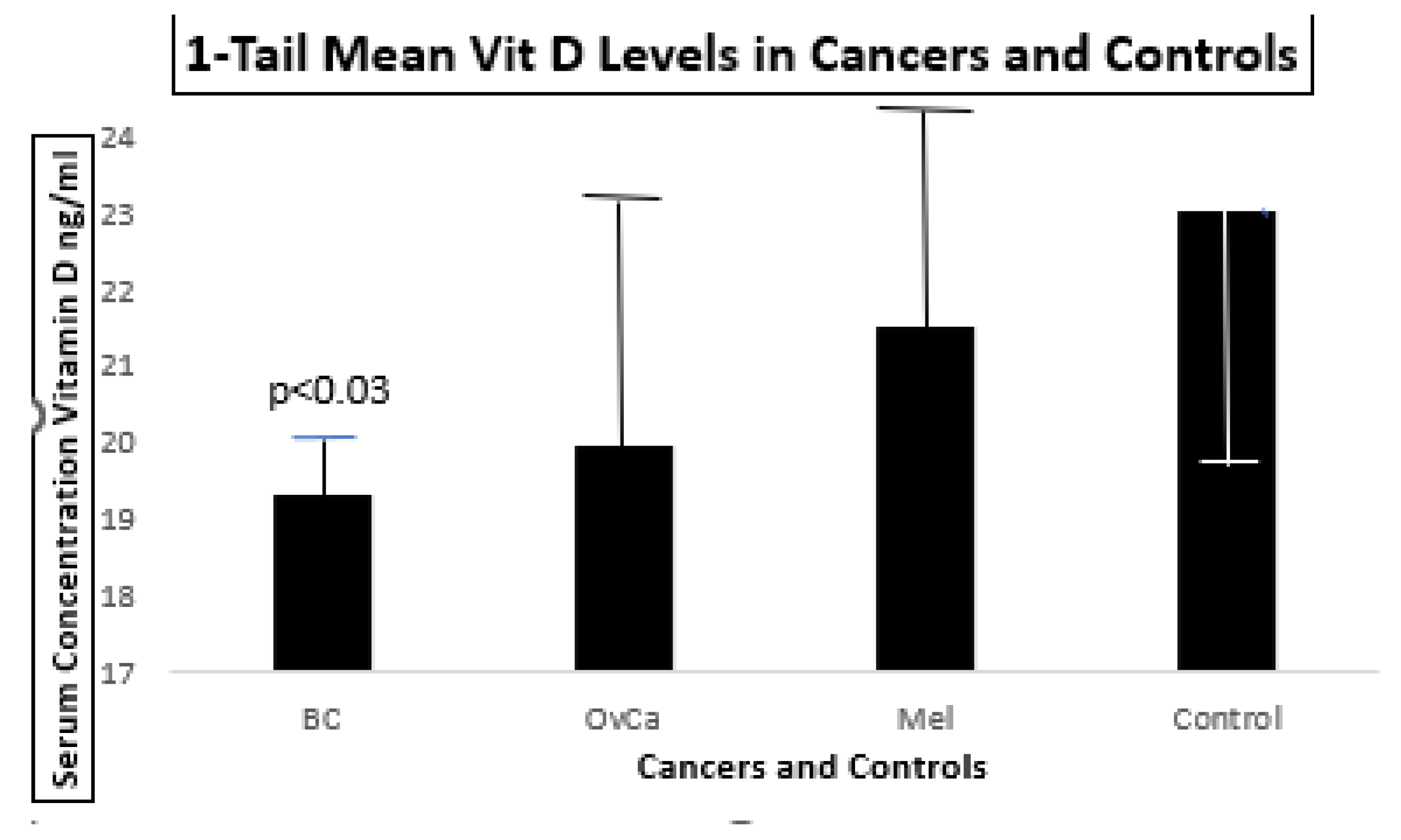

Figure 10.

shows that blood vitamin D levels are significantly lower than that of controls. Normal levels of Vitamin D are typically >30ng/ml. The data are summarized in

Table 3 below.

Figure 10.

shows that blood vitamin D levels are significantly lower than that of controls. Normal levels of Vitamin D are typically >30ng/ml. The data are summarized in

Table 3 below.

The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. Only the BC patients had lower concentrations when compared to a group of 2,453 controls.

The data are summarized in the table below.

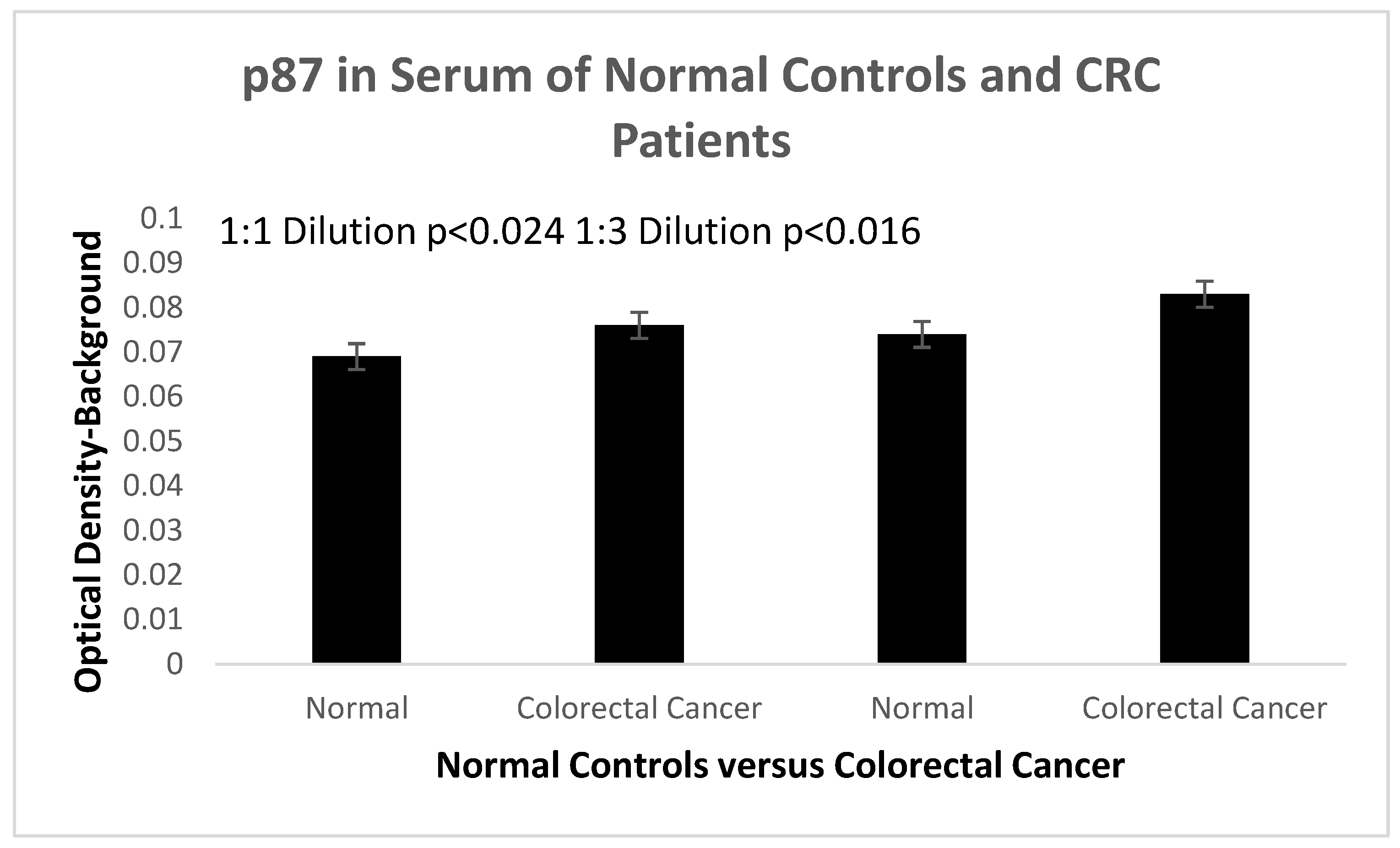

In order to work with serum to detect Adnab-9 which may be applicable to many existing cancer databanks we collaborated with Susanne Pedersen and Emily Wizgoft of Clinical Genomics to demonstrate that we could obtain sensitive and specific data from sera that could be used in the above cancers of interest. In this case we limited ourselves to CRC patient samples procured locally at Clinical Genomics as seen below in

Figure 11.

This is a proof of concept that this antibody may be used as a serum test in the 3 InImS -related cancers under consideration here, as it has been successfully used in CRC.

Table 4.

Demographics and Results Associated with

Figure 11.

Table 4.

Demographics and Results Associated with

Figure 11.

| Category |

CRC Patients n=20 |

Controls n=10 |

Significance |

| Age (yrs) mean±sd Ethnicity (%Whites) |

64.0±10.3

100% |

52.2±3.4

100% |

P<0.0021

NSS |

Gender (% Males)

Serum ELISA mean: |

58.8 |

50.50 |

NSS |

1:1 Dilution OD

1:3 Dilution OD |

0.076±0.007

0.083±0.008 |

0.069±0.006

0.074±0.004 |

P=0.024

P=0.016 |

4. Discussion

Bladder cancer is the 4

th most common cancer in males and expresses a spectrum of aggressive and indolent behaviors, depending on its type [

10]. Factors of advancing age, tobacco abuse and male gender puts this demographic at risk. The deciding factor for treatment decision is whether the cancer is invading the muscle. Endoscopic resection may suffice for non-muscle invasive cancers with adjuvant intravesical therapy. Surveillance with advanced cystoscopy reduces recurrence and standard immunotherapy with BCG may suffice lower risk non-muscle invasive cancers and still remains the state of the art for the past 5 decades. For muscle invasive cancers, aggressive surgery with urinary diversion, are the usual alternative, especially where BCG has failed in non-high risk non-muscle invasive cases, BCG is still an option in immunotherapy[

10], using checkpoint inhibition and other therapies. Recently, it has been suggested that the tumor microenvironment is adversely affected by hypoxia that impedes BC immunotherapy [

11] and biomarkers for hypoxia have been sought [

12] and TLR8 may be a potential target Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILS) correlate with cells of T-cell lineage, natural killer (NK) and dendritic cells (DC) and this activity correlates with the hypoxia risk score also related to immune checkpoint cell expression [

12]. Additional infiltrating cells such as cancer associated fibroblasts have been found to represent different functional subtypes in both muscle invasive and non-muscle invasive tumors that may influence of behavior of these Cancer-associated Fibroblast (CAF) subforms [

13]. Aging plays an important role in tumorigenesis, as p16

high senescent (p16

h-sn) fibroblasts multiply with age, allowing for increased cancer growth with aging mice expressing C-X-C motif chemokine 12 gene (Cxcl12), which serves as a growth promotor [

14].

The InImS and the BC cells participate in the anti-tumor effect in collusion with BCG which is taken up by these cells which prompts expression of cytokines in concert with the TILS noted above, which directly kill BLCA cells either directly by the effects of BCG or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) release [

15]. In an excellent summary of BCG by Singh, Netea and Bishai [

16], they point to the various roles of BCG starting as an anti-tuberculosis vaccine on July 18, 1921, but has had beneficial effects in autoimmune diseases, and cancer therapy both in BC and Mel.

In 86,058 patients of Swedish Cancer-Family database [

17], 7% were found an increased prevalence of familial cancers in bladder as well as shared cancer genes inscribed in red and additional shared and unshared genes can be seen in

Table 5. There is also evidence for BC familial clustering [

18] as well as Mel [

19] also associated with second primaries [

20].

Given the interest in predicting the response to ICI therapy, this appears to center of the Tumor mutation burden [

23]. There are however many familial genes studies associated with Mel [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Within the last 4 years, the role of innate immune lymphoid cells (ILCs) and their intricate applications to tumor generation and suppression has been further elucidated with a threefold classification of immunogenetic function [

35].The first (ILCs1) comprise NK, the second (2 ICLs) are limited to ILC2s, and the third (3ILCs) contain LTi and ILILC3s. Group 1 are anti-tumorigenic; Groups 2 and 3 are pro-tumorigenic. However, the behavior of these groups differ in function in various tumors they affect. The current efforts are focused on a number of solid and hematologic malignancies

inter alia BC and Mel.

While the above innate immune cells may be ambiguous there are other players that may be used for their anti-cancer effect. Of intense interest are Human endogenous retroviral (HERV) sequence which are fairly ubiquitous in human genomes (up to 8%) and may confer protection to patients at risk from Mel, BC and OvCa [

36] as summarized in

Table 6 below.

While the reliance on family history for OvCa rather than a cohort of patients with this cancer is a definite weakness, the fact that family members appear to fall into line with respect to FERAD ratios and NLR, suggests that they can serve as a familial surrogate. The relative strength is the large group of control patients with prolonged follow-up that we relied upon for comparative statistical analysis. Of interest is ACE inhibitors appear to be used significantly less in patients with a F/H of OvCa since there is a practical reason to be concerned with potential interreference of cis-platinum effectiveness with this class of medications [

37]. There is also an aspect of SARS-CoV-2 interaction with an OvCa patient that may alleviate aspects of the cancer and the severity of other types of cancer[

38]. While we were only able to show a trend for an increased difference of serum ferritin between patients with a family history of OvCa, it is well acknowledged that ferritin is deleterious for these patients [

39] but does have utility as a diagnostic biomarker in concert with other known biomarkers for OvCa.

5. Conclusions

At least 2 of 8 genes are shared between BLCA and Mel and thus share pathogenesis of disease. Additional work is need to confirm this association. There is little doubt however that ICI and BCG are highly effective in treating Mel and BLCa in the usual clinical context. Both these cancers share high mutation burdens (>10 mut/Mb) and they would fall within Federal Drug Administration cut-offs for ICI [

20] but there is a concern that many cancers would not qualify at this cut-off. To level the playing field, Zheng [

23] resampled 10,000 available cohorts to arrive at a more equitable way for arriving at a qualifying mutation burden. After the analysis it was suggested that category 1 cancer types have a reliable prediction based on mutational burden and likelihood of responding to ICI. Five tumors from this category were named which included Mel and BC where cutoffs were not affected (melanoma, CRC, bladder cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Interestingly, this approach might also benefit patients with cancer of unknown origin (HR 0.466 p<0.034), however in a database patient diagnosed with this condition, FERAD level was relatively low at 12,167. Since FERAD ratios align with NLR, FERAD should be evaluated for ability to predict ICI outcomes leading to a paradigm change that might allow greater numbers of patients with MEL, BC and OvCa to qualify for ICI. BRACA2 gene mutations while occuring in breast and ovarian cancer also are found in other cancers [

48].

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.T. and A.M.; methodology, M.T..; validation, M-P.M., Y.Y.; formal analysis, M.L., resources, B.M.; data curation, Y.Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing, N-F.R. M-P.M.; supervision, M.T.; project administration, D.E.; funding acquisition, B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wayne State University School of Medicine (protocol code) #H09-62-94, date of approval 14/14/1996).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written consent was given by all the participants in the NIPCON study in accordance with the Detroit and Wayne State University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. The H09-62-94 study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the above Institutional Review Boards for studies involving humans. Informed consent was taken from all the subjects involved in this study. Online data for the PD-L1 data sources are given in the body of the manuscript or in the References Section and were obtained during the month of November 2023. The views expressed herein are purely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Federal Government under whose auspices this study was conducted.

Data Availability Statement

Data-Sharing Statement The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author under the Data Transfer Agreement and all the following conditions apply. An application must contain statements to the effect of the following: what data are being requested; what data may be used; how will the data be used; who will access the data; and how the data will be accessed, stored, and safeguarded. The applicant must also address how the data will be disposed of, after the completion of the data review. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in the VHA directive 1200.12 of 3/9/2009. The VHA Handbook addresses both the use of data for research and the clinical and administrative data repositories for research. It also addresses the development and use of data research repositories.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Natie Gordon, Ruth Almeleh, Pena Sewata and Dr. Sumner Kraft, who died on 7/20/25 and helped develop the science underlying gastrointestinal immunology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Özdemir, D.; Büssgen, M. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of combination therapy versus monotherapy in malignant melanoma. J Pharm Policy Pract 2023, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cookson, M.S.; Guercio, B.J.; Cheng, L. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer. BMJ 2024, 384, e076743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.l.; Eilber, F.R.; Carmack Holmes, E.; et al. BCG Immunotherapy of Malignant Melanoma: Summary of a Seven-year Experience. Ann Surg 1974, 180, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, L. : Regression of Intradermal Malignant Melanoma after Intralesional Injection of BCG. Cancer Chemo. Rep. 1972, 56, 659. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky, C.; Hisschant, G.; Oettgen, H. Treatment of Malignant Melanoma by Intralesional Injection of BCC. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1972, 13, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Seigler, H.F.; Sbingleton, WV.; Metzgar, R.S.; et al. Non-specific and Specific Immunotherapy in Patients with Melanoma. Surgery 1972, 72, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobi, M.; Talwar, H.; Rossi, N.F.; Lockette, W.; McVicker, B. A Practical Format to Organize Cancer Constellations Using Innate Immune System Biomarkers: Implications for Early Diagnosis and Prognostication. Int J Transl Med (Basel) 2024, 4, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tobi, M.; Antaki, F.; Rambus, M.A.; Yang, Y.-X.; Kaplan, D.; Rodriguez, R.; Maliakkal, B.; Majumdar, A.; Demian, E.; Tobi, Y.Y.; et al. The Non-Invasive Prediction of Colorectal Neoplasia (NIPCON) Study 1995–2022: A Comparison of Guaiac-Based Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) and an Anti-Adenoma Antibody, Adnab-9. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tobi, M.; Khoury, N.; Al-Subee, O.; et al. Predicting Regression of Barrett's Esophagus-Can All the King's Men Put It Together Again? Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lenis, AT.; Lec, P.M.; Chamie, K. Bladder Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Hypoxia is correlated with the tumor immune microenvironment: Potential application of immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 22333–22353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Qi, Z.; et al. A Robust Hypoxia Risk Score Predicts the Clinical Outcomes and Tumor Microenvironment Immune Characters in Bladder Cancer. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 725223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caramelo, B.; Zagorac, S.; Corral, S.; Marqués, M.; Real, F.X. Cancer-associated Fibroblasts in Bladder Cancer: Origin, Biology, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Eur Urol Oncol;Epub 2023, 6, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meguro, S.; Johmura, Y.; Wang, T.W.; ey al. Preexisting senescent fibroblasts in the aged bladder create a tumor-permissive niche through CXCL12 secretion. Nat Aging;Epub 2024, 4, 1582–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Redelman-Sidi, G.; Glickman, M.S.; Bochner, B.H. The mechanism of action of BCG therapy for bladder cancer--a current perspective. Nat Rev Urol 2014, 11, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Netea, M.G.; Bishai, W.R. BCG turns 100: Its nontraditional uses against viruses, cancer, and immunologic diseases. J Clin Invest 2021, 131, e148291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, H.; Hemminki, O.; Försti, A.; Sundquist, K.; Hemminki, K. Familial Urinary Bladder Cancer with Other Cancers. Eur Urol Oncol 2018, 1, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Leiser, C.L.; O'Neil, B; et al. Familial Cancer Clustering in Urothelial Cancer: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018, 110, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Debniak, T. Familial malignant melanoma—Overview. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2004, 2, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schmid-Wendter, M.H.; Baumert, J.; Wendterb, C.M.; Plewig, G.; Volkenandt, M. Risk of second primary malignancies in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2001, 145, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Matin, S.F.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Roupret, M. Systematic Review: An Update on the Spectrum of Urological Malignancies in Lynch Syndrome. Bladder Cancer 2018, 4, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Necchi, A.; Madison, R.; Pal, S.K.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Upper-tract and Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus;Epub 2021, 7, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M. Tumor mutation burden for predicting immune checkpoint blockade response: The more, the better. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10, e003087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Robles-Espinoza, C.D.; et al. POT1 loss-of-function variants predispose to familial melanoma. Nature genetics 2014, 46, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.W.; et al. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013, 339, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolotto, C.; et al. A SUMOylation-defective MITF germline mutation predisposes to melanoma and renal carcinoma. Nature 2011, 480, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, V.R.; et al. Frequencies of NRAS and BRAF mutations increase from the radial to the vertical growth phase in cutaneous melanoma. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2009, 129, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannengiesser, C.; et al. New founder germline mutations of CDKN2A in melanoma-prone families and multiple primary melanoma development in a patient receiving levodopa treatment. Genes, chromosomes & cancer 2007, 46, 751–60. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.J.; Mihm, M.C. Melanoma. The New England journal of medicine 2006, 355, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, M.T.; et al. MC1R germline variants confer risk for BRAF-mutant melanoma. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2006, 313, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molven, A.; et al. A large Norwegian family with inherited malignant melanoma, multiple atypical nevi, and CDK4 mutation. Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer 2005, 44, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gray-Schopfer, V.C.; da Rocha Dias, S.; Marais, R. The role of B-RAF in melanoma. Cancer metastasis reviews 2005, 24, 165–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, K.Y.; Tsao, H. The genetics of skin cancer. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics 2004, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wu, P.; Chen, Y.; Chai, Y. Ambiguous roles and potential therapeutic strategies of innate lymphoid cells in different types of tumor. Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 1513–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schiavetti, F.; Thonnard, J.; Colau, D.; Boon, T.; Coulie, P.G. A human Endogenous Retroviral sequence encoding an antigen recognized on melanoma by cytolytic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 5510–5516. [Google Scholar]

- Cegolon, L.; Salata, C.; Weiderpass, E.; Vineis, P.; Palù, G.; Mastrangelo, G. Human endogenous retroviruses and cancer prevention: Evidence and prospects. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nagappan, A.; Kim, K.H.; Moon, Y. Caveolin-1-ACE2 axis modulates xenobiotic metabolism-linked chemoresistance in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Cell Biol Toxicol;Epub 2023, 39, 1181–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hayashi, T.; Sano, K.; Yaegashi, N.; Konishi, I. Pathological Evidence for Residual SARS-CoV-2 in the Micrometastatic Niche of a Patient with Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 5879–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Zou, X.; et al. Iron promotes ovarian cancer malignancy and advances platinum resistance by enhancing DNA repair via FTH1/FTL/POLQ/RAD51 axis. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L. Serum CA125 in combination with ferritin improves diagnostic accuracy for epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Biomed Sci 2018, 75, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musilová, P.; Kubícková, S.; Rubes, J. Assignment of porcine cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and oncogene c-mos (MOS) by nonradioactive nonfluorescence in situ hybridization. Anim Genet 2002, 33(2), 145–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pissa, M.; Helkkula, T.; Appelqvist, F.; et al. CDKN2A genetic testing in melanoma-prone families in Sweden in the years 2015-2020: Implications for novel national recommendations. Acta Oncol Epub. 2021, 60, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilluffo, D.; Barra, V.; Di Leonardo, A. P14ARF: The Absence that Makes the Difference. Genes 2020, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Hamed, M.; Emmert, S.; Wolkenhauer, O.; Fuellen, G.; Thiem, A. The Prognostic and Predictive Role of Xeroderma Pigmentosum Gene Expression in Melanoma Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 810058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamamoto, H.; Hirasawa, A. Homologous Recombination Deficiencies and Hereditary Tumors. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vahteristo, P.; Tamminen, A.; Karvinen, P.; Eerola, H.; Eklund, C.; Aaltonen, L.A.; Blomqvist, C.; Aittomäki, K.; Nevanlinna, H. p53, CHK2, and CHK1 genes in Finnish families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome: Further evidence of CHK2 in inherited cancer predisposition. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 5718–5722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thodi, G.; Fostira, F.; Sandaltzopoulos, R.; et al. Screening of the DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 in a Greek cohort of Lynch syndrome suspected families. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).