1. Introduction: The Biological Imperative of Erasure

Memory and forgetting are biological systems that are tightly coupled, and they enable organisms to respond to dynamic environments. Although classical theories defined forgetting as an explicit passive loss of information, there is a consistent body of evidence that shows that the brain actively engages in a specific set of molecular and circuit-based mechanisms to dismantle or weaken traces of memory. The mechanisms overcome interference, avoid mnemonic overload and ensure the flexibility necessary to support continuous learning. In this perspective, forgetting does not represent a blemish, but a preserved homeostatic process that, in a continuous way, keeps the stability of experiences that are stored [

1].

An independent line of evidence has found that consolidated memories are not fixed. When recollected, numerous memories dissolve back to a transient destabilised state, which needs restabilisation through protein synthesis. This prediction error-gated reconsolidation window presents a time opportunity for an exceptionally known exactness with which the underlying engram can be altered or dysfunctional. Combined, these findings completely transform the conceptual and translational environment of the science of memory: the biological processes involved in executing specific forgetting are already present in the brain [

3].

The thesis presented in this review is that endogenous processes of active forgetting form the mechanistic basis on which engineered memory-deletion interventions can be based. We describe the architectural pathways of the Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS) of synthesising molecular pathways of synaptic weakening; circuit-level regulation of engram accessibility, and the boundary condition of reconsolidation with new neurotechnology [

4].

The review is conducted in four sections. We come to first describe the molecular mechanisms that destabilise the synapses and facilitate active forgetting. Second, we are going to describe the circuit-level dynamics of engram accessibility. Third, we discuss the conditions at the border of reconsolidation and prediction error conditions of memory lability. Fourth, we combine these biological principles and new neurotechnology to suggest a four-stage TMDS model, and then an ethical assessment.

Through these areas coming together, active forgetting is no longer a pathology but a biologically inscribed opportunity, a backdoor, whereby, with more precise memory modification aimed, it could become possible in a clinical setting.

Nevertheless, regardless of the tremendous gains made in molecular, systems, and computational neuroscience, active forgetting, engram accessibility, prediction-error-gated reconsolidation, and emerging neurotechnology have not been merged into a framework to explain how targeted memory deletion can be achieved. This gap in ideas restricts the discipline in determining the practicability and morality of engineered remembrance change.

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Active Forgetting

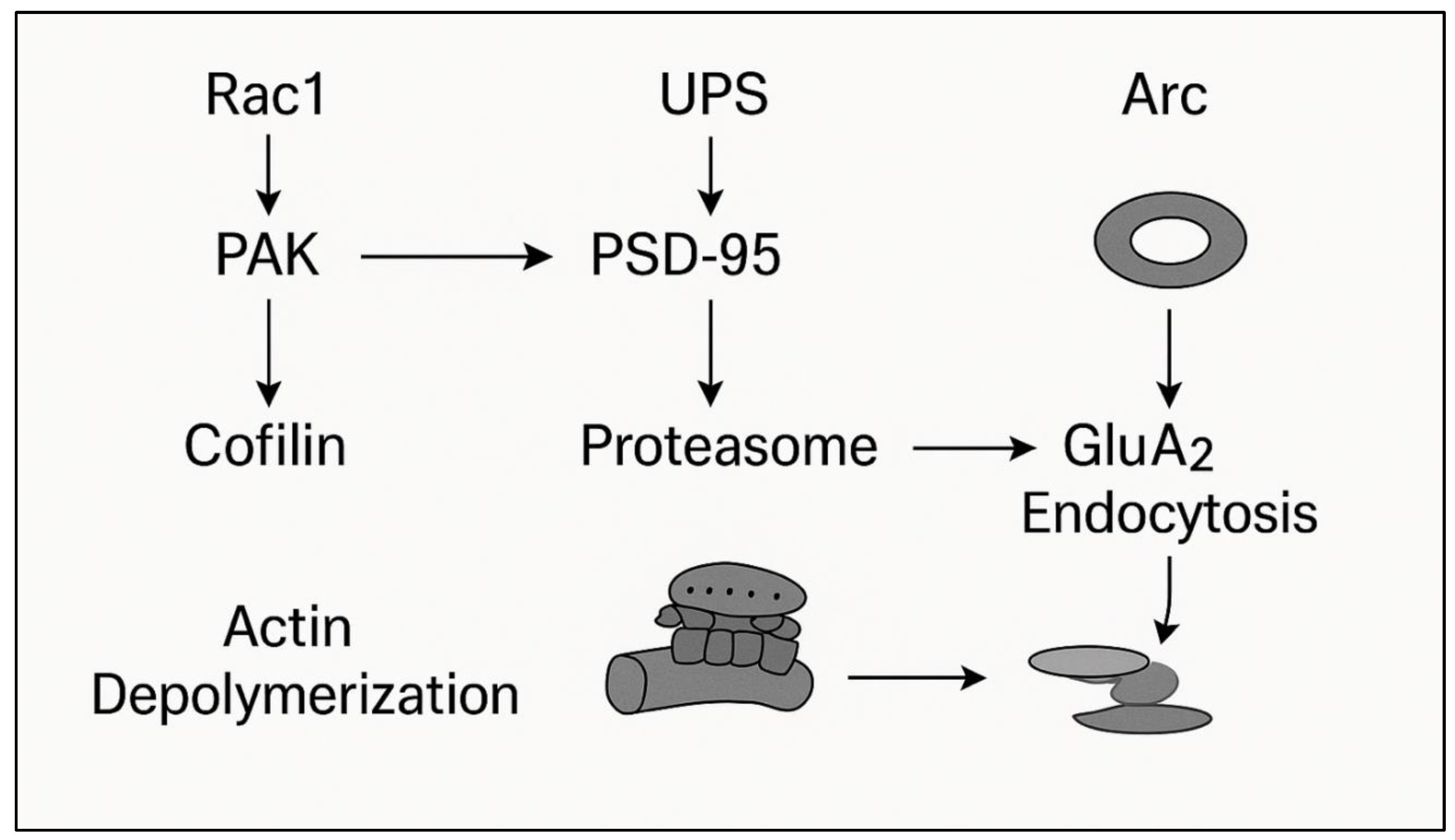

Active forgetting is achieved through a series of coordinated molecular activities that cause weakening of synaptic connections, remodelling of dendritic spines, and weakening long-term potentiation at the same time. These processes include: Rac1-mediated actin remodelling, proteasomal protein degradation, AMPA receptor endocytosis by GluA2, and Arc-mediated weakening of synapses are part of the biological pathways that stabilise, make a memory labile, or erase it. Every mechanism presents a possible site of leverage among a Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS), which attempts to take advantage of endogenous destabilisation pathways in a controlled and memory-specific fashion.

2.1. The Rac1-Scribble-Cofilin Signalosome: The Structural Eraser

Rac1 is a small GTPase that works as a global controller of spine dynamics and intrinsic forgetting. High levels of Rac1 increase the rate of spine shrinkage and memory degradation, and the absence of Rac1 increases memory retention. Rac1 is activated, which recruits a signalling complex organised by Scribble and results in the activation of p21-activated kinase (PAK), resulting in the eventual activation of Cofilin. The Cofilin divides F-actin filaments of the dendritic spines and triggers a quick structural destabilisation.

This direction proves that forgetting is not the process of active decay but is an energy-consuming process organised. In the case of TMDS, Rac1 -Cofilin signalling is a drugable axis that can elicit specific engram weakening. Any subsequent clinical application, however, should concern the issue of cell-type and engram-specific activation, since non-specific Rac1 activation may cause global synaptic dysregulation.

2.2. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS): The Synaptic Cleaner

This erasure of the protein level of the postsynaptic density is furnished by the UPS. Proteasomal degradation occurs as a result of ubiquitination of scaffolding proteins, including PSD 95, SHANK and GKAP and decreases synaptic strength, allowing memory destabilisation. Pharmacological inhibition of the proteasome inhibits memory labilisation during retrieval, which implies that proteolysis plays an obligatory role in reconsolidation [

8].

UPS work has a spatial constraint, which enables selective deletion with all-spatial cognitive deficit, i.e., synapse-specific weakening. In TMDS, the UPS forms the mechanistic target molecule of Phase 3 (Intervention): the drugs or neuromodulator procedures will need to exploit this local proteolysis to make sure that destabilised memories do not restabilise [

9].

2.3. GluA2 Endocytosis: The Gateway to Lability

Postsynaptic deactivation of GluA2-containing AMPA receptors on the postsynaptic membrane is the key to long-term depression (LTD) and destabilisation in reconsolidation-dependent processes. Endocytosis of GluA2 through retrieval reduces the synaptic efficacy, thus indicating that an engram is in a modifiable state. Blocking this process using particular peptides, like the GluA23Y, blocks memory lability; this gives good evidence that AMPAR trafficking is a biophysical gateway that allows an engram to be updated or eliminated. In the therapeutic context of Targeted Memory Deletion Systems (TMDS), GluA2 endocytosis of a memory is a well-defined point at which the memory has been stored once it is in the endocytosis, such that when the carriers of protein synthesis are blocked, or the interruption of synaptic restabilization is achieved, the trace can be eliminated selectively. On the contrary, the inability the evocation the GluA2 internalisation makes the subsequent interventions ineffective [

10,

13].

Figure 1.

Molecular Pathways of Active Forgetting.

Figure 1.

Molecular Pathways of Active Forgetting.

2.4. Arc: The Immediate Early Gene of Forgetting

Arc (activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) is an expression of neuronal activity that is critical in AMPAR endocytosis and homeostatic synaptic scaling. Arc recruits endocytic machinery to enable a large-scale down-regulation of synaptic strength and can organise the ensemble-level down-regulation of memory traces. New evidence suggests that Arc may differentiate virus-like capsids with the ability to transfer RNA between cells, which may be used to modify engrams distributed. These findings are, however, preliminary and can be regarded as speculative in a clinical setting. In the case of TMDS, Arc is a molecular amplifier of forgetting mechanisms, and this offers a natural mechanism through which destabilised synapses can experience sustained weakening [

17].

2.5. Summary

Molecular Constraints towards TMDS Design. All these processes, Rac1-mediated actin remodelling, UPS-mediated proteolysis, GluA2 endocytosis, and Arc expression, define the synaptic environment in which memories are either made or lost. An effective TMDS should connect to these molecular pathways by:

causing controlled destabilisation,

maintaining local proteolysis, and

Inhibition of synaptic restabilisation at reconsolidation.

These mechanisms provide the biological rationale of the circuit-level and technological strategies, which are addressed in later sections.

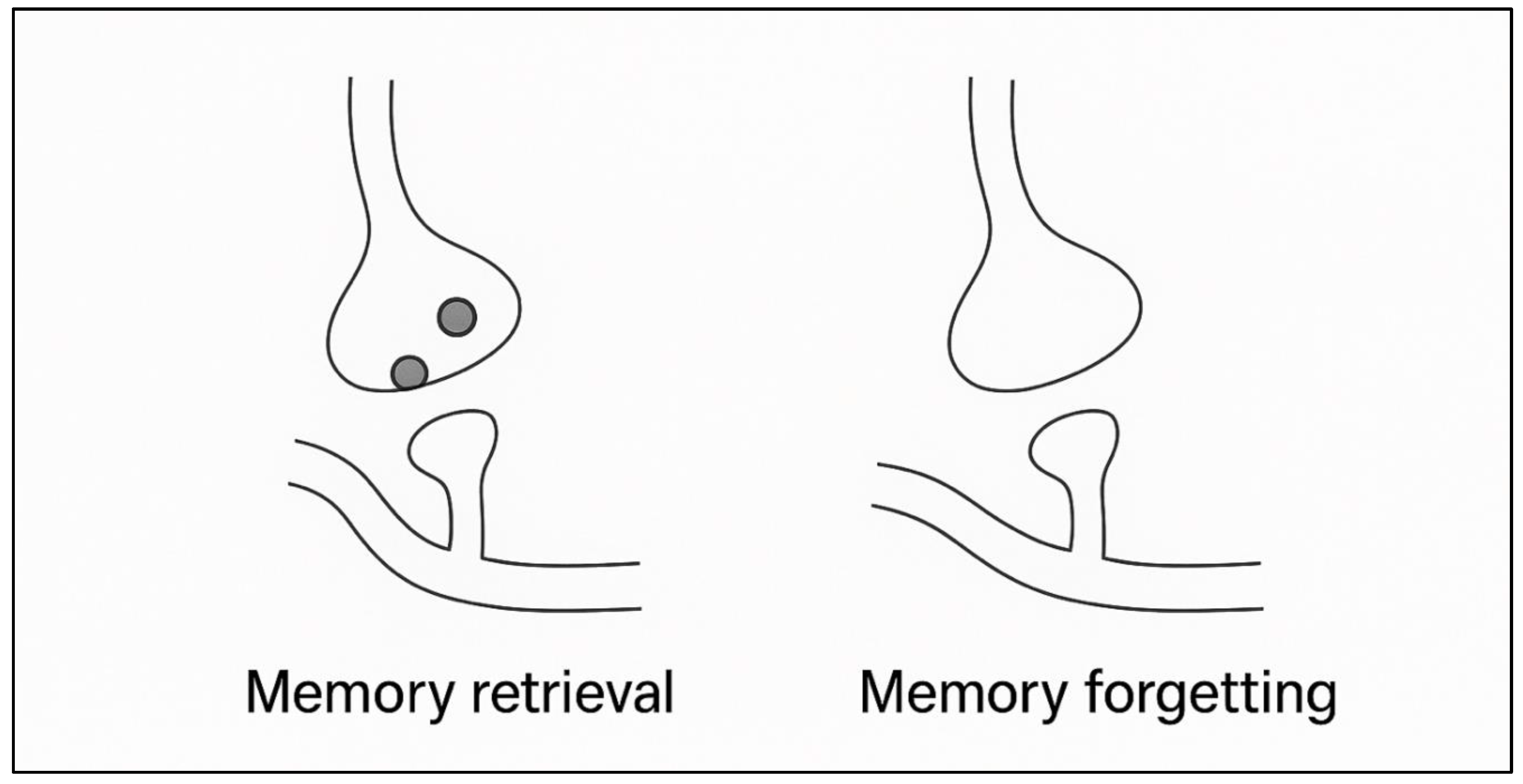

3. Circuit Dynamics: The Engram and Its Regulation

The synaptic processes of the active forgetting act in an ensemble of distributed neural networks, called engrams, which encode particular experiences. Such groups show dynamic access to information controlled by hippocampal-prefrontal networks, thalamic coordination and structural remodelling processes. This is important because to design a Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS), awareness of these circuit-level constraints is required, enabling a specific engram to be destabilised without impacting other engrams.

Figure 2.

Circuit-Level Model of Engram Accessibility.

Figure 2.

Circuit-Level Model of Engram Accessibility.

3.1. Silent Engrams vs. True Erasure

Optogenetic experiments show that the memories that become unreachable due to the effects of a pharmacological blockade (such as anisomycin-induced amnesia) can be restored by stimulating the original engram cells directly. The connectivity underlying is still maintained despite the failure of natural cues to recall the memory. This differentiation shows two dissociable elements of a memory trace:

A TMDS then has to consider this duality. Interventions that do not alter synaptic potentiation can result in silent engrams, which can subsequently be reinstated later with exposure to stress. The requirement that a permanent deletion be reliable requires either the destruction of the connectivity per se or a permanently irreversible loss of engram excitability. These are taken into account when designing the protocols of TMDS verification, distinguishing between suppression and erasure.

3.2. Neurogenesis-Induced Forgetting

Adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus introduces new granule cells in the adult dentate gyrus, triggering the reallocation of synapses and remodelling at the network level. This operation damages the representation of older dentate gyrus-reliant memories by transforming input-output patternings in the circuit. Infantile amnesia is a result of high rates of neurogenesis during early development, and the rate of neurogenesis is experimentally increased to accelerate forgetting of contextual fear memories in adults [

26].

Although neurogenesis is an extremely potent way of forming circuits, its low rate and widespread effect in the network restrict its accuracy in deleting a particular memory. In the case of TMDS, neurogenesis is more appropriately understood as a supportive effect- a possible long-term stabilisation of deletion effects and not an acute intervention with specific effects on memory [

28,

29].

3.3. The Nucleus Reuniens: Orchestrating Specificity

The thalamic nucleus reuniens coordinates hippocampal and medial prefrontal cortical activity with the help of the theta oscillations, which allow the coordinated retrieval and discrimination of the context. Reinforcement inactivation leads to loss of the capacity to differentiate similar contexts and high-fidelity memory retrieval, which enhances generalisation. Reuniens, therefore, is a circuit-level control in memory accuracy. The destabilisation would be possible by temporarily disrupting its activity during a reconsolidation window, through greater or lesser non-invasive techniques, like focused ultrasound, to degrade the contextual or emotional specificity of a target memory. In the case of TMDS, reuniens is a possible neuromodulatory target that is capable of transiently damaging the integrative mechanisms that stabilise the process of reactivating engrams [

31,

33,

34].

3.4. Pattern Separation and Sparse Coding

The Pattern separation is maintained by the dentate gyrus, which converts similar signals into non-overlapping neuronal groups that are minimal. Engram representations in this part are very sparse and may consist of less than 2% of granule cells. Sparse coding makes it easier to increase the specificity of memory, but difficult to specifically manipulate: interventions that include large tissue volumes, like global neuromodulation, can interfere with irrelevant memories [

37]. The sparse engram architecture has a basic limitation on TMDS: deletion can only be effectively done by high-precision tagging of a particular neuronal subpopulation that is becoming active when memory is being retrieved. This can be done by activity-dependent labelling methods (such as c-Fos/ Arc gene expression patterns) or by real-time monitoring of memory-related activation states [

38].

3.5. Summary

Circuit Requirement TMDS. In hippocampal, thalamic and prefrontal circuitries, the accessibility of memory depends on the interaction between ensemble connectivity, synaptic strength, circuit coordination and structural remodelling. A TMDS that is clinically viable should:

distinguish between erased and silent engrams,

minimise disruption of the off-target circuit,

distort retrieval pathways temporarily to destabilise it,

should be able to achieve engram-level accuracy with sparse coding.

These clues mediate the biological forgetting processes with the temporal aspects of reconsolidation that will be discussed in the next section.

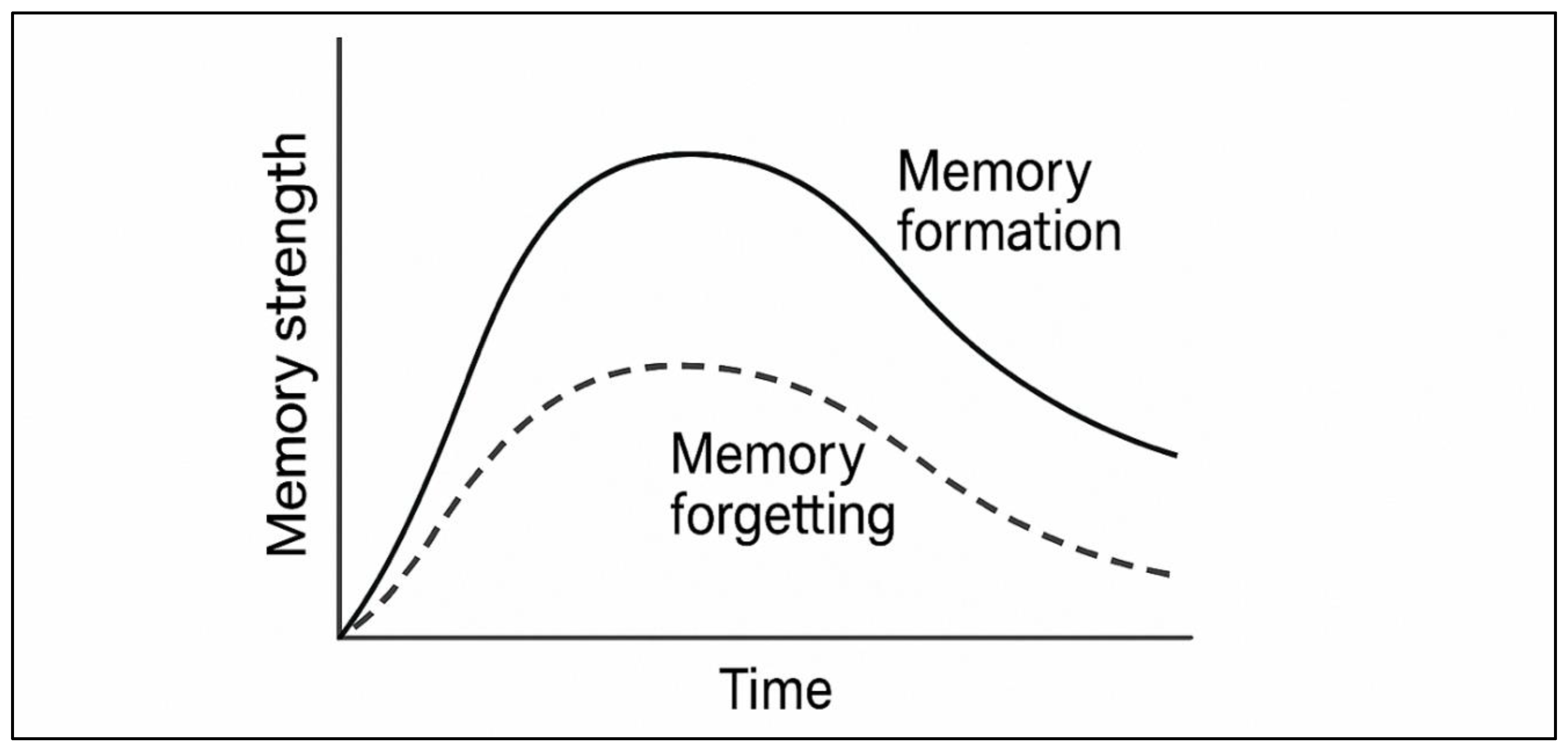

4. Reconsolidation: The Temporal Window of Vulnerability

Reconsolidation theory supports the idea that consolidated memories can revert to a temporary, labile state under certain conditions of reactivation. The molecular processes maintaining long-term synaptic stability are reversed in part during this window, permitting the underlying engram to be changed, weakened, or erased. Reconsolidation, therefore, constitutes the temporal basis of a Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS); otherwise, downstream interventions cannot modify the trace. On the other hand, too much disturbance can cause extinction instead of erasure. Consequently, to be more exact with memory engineering, it is important to understand the boundary conditions on which the lability is defined.

4.1. Prediction Error (PE): The Boundary Condition

Recalling memories does not necessarily lead to reconsolidation. Rather, destabilisation only starts when the retrieval experience creates a prediction error (PE), one that is a difference between the expected and actual results. PE is an adaptive filter that is energy-saving, and it only updates memory when contingencies in the environment vary. The practical results of PE may be summarised in the following way:

No PE (Stability): A perfectly aligned retrieval generates no changes in the memory. The engram does not destabilise, and the continuation of the trace does not require the production of proteins.

Moderate PE (Lability): The endocytosis of GluA2-AMPAR and ubiquitin-proteasome system-mediated proteolysis triggered by partial violations of expectation creates a reversible destabilisation window. This is the opportunity TMDS will not have.

Excessive PE (Extinction): The existence of large discrepancies brings new learning of an inhibitory nature and not destabilisation of the original memory. The initial engram is retained, but through IL-ITC pathways, it is suppressed.

This is a non-linear PE-lability relationship that gives the basic engineering problem of TMDS: the retrieval process should be consistently able to generate moderate PE. When PE is too weak, the memory will not be unlocked (the system will not create an extinction memory); when it is too strong, the original memory will not be destroyed but a new one developed. PE needs algorithmic tuning, which may be possible with virtual reality, virtual-controlled cue violation, or physiological feedback.

Figure 3.

Prediction Error Window for Reconsolidation.

Figure 3.

Prediction Error Window for Reconsolidation.

Table 1.

The Prediction Error Spectrum and Memory Fate.

Table 1.

The Prediction Error Spectrum and Memory Fate.

| PE Magnitude |

Memory State |

Outcome |

Mechanism |

| Zero / Low |

Stable |

Persistence |

No protein synthesis required. |

| Moderate |

Labile |

Update / Erasure |

GluA2 endocytosis; UPS degradation. |

| High |

Stable (Inhibited) |

Extinction |

New inhibitory circuit (IL-mPFC -> ITC). |

4.2. Molecular Blockade of Restabilisation

The molecular signature of destabilisation is demonstrated by the presence of molecules.

In case moderate PE is achieved, destabilisation is characterised by:

GluA2 -AMPAR endocytosis, synaptic efficacy decreases;

PSD scaffolds degenerate under the influence of UPS.

Stabilisation proteins are removed depending on the proteasome.

Activation of actin-remodelling pathways, including Rac1-Cofilin;

De novo protein synthesis is required in restabilisation.

In case any of these processes are inhibited, e.g., by blocking GluA2 endocytosis or the proteasome, retrieved memories become unable to destabilise and are unable to resist modification. In the case of TMDS, the mechanisms define the molecular preconditions that should exist before the activation of Phase 3 (Intervention).

4.3. Pharmalogical Blockade of Restabilisation

To interrupt the process of restabilisation, the following pharmacological agents may be utilised: Neurotransmitters. Inhibiting the reabsorption of 5-HT3B receptors citation.

After being destabilised, a memory requires reconsolidation, which is dependent on protein synthesis to maintain itself indefinitely. This restabilisation process can be prevented by pharmacological agents, and basically, the process effectively leaves the destabilised state orphaned and resulting in loss of memory.

Propranolol (β-adrenergic blockage)

Propranolol is selective in attenuating the noradrenergic signalling in the amygdala. Human research indicates that propranolol intake during the pre-retrieval period may be used to remove the emotional display of traumatic memories without impacting the declarative information. This makes propranolol especially appropriate in valence deletion, which is a partial form of memory modification of clinical importance.

Rapamycin (mTOR inhibition)

Rapamycin disrupts mTOR-dependent translation of synaptic proteins needed in reconsolidation. Animal work exhibits a strong erasure in the case of rapamycin administration following destabilising retrieval. There is clinical trial evidence of possible efficacy in pathological reward or fear memories. Rapamycin is an ideal TMDS Phase 3 delivery option because it is FDA-approved and has a good safety profile compared to general translation inhibitors.

The problem facing TMDS is not that these drugs can weaken memories- they can- but how to provide them selectively to a specific engram. This is tackled in the technological vectors that are discussed in the following section.

4.4. Constraints and Failure Modes of Reconsolidation-Based Interventions

Reconsolidation failure is common in both animals and humans. Major reasons include:

Insufficient PE, preventing destabilisation.

Overlong retrieval causes extinction rather than reconsolidation.

Memory age or strength which can raise the PE threshold for lability.

Boundary conditions that vary by memory type (episodic vs procedural vs emotional).

Inconsistent mapping between retrieval cues and engram activation, especially in humans.

In the case of TMDS, these limitations would mean that Phase 2 (Destabilisation) would include the real-time observation of physiological and neural indicators of PE, such as pupil dilation, skin conductance, or pattern drift during fMRI, to determine that one is in the labile window.

5. Technological Vectors for Delivery

Active forgetting and reconsolidation have a basis in the molecular and circuitry events that enable the provision of the biological basis of active forgetting and reconsolidation, making available the target of memory modification. New neurotechnologies put forward discrete pathways to selectively regulate engram stability, induce destabilisation, or disrupt later restabilization. These modalities are used in a Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS) as modulation mechanisms on individual pipeline phases delivered by the engram. The current review assesses the most promising ones (decoded neurofeedback, targeted memory reactivation during sleep, optogenetic principles, non-invasive neuromodulation, and focused ultrasound) in terms of their mechanistic aptitude, translational preparedness, and inherent constraints.

5.1. Decoded Neurofeedback (DecNef): Implicit Modulation of Engram Probability Distributions

Decoded neurofeedback enables the conditioning of certain multivoxel patterns of activation without the knowledge of the subject. DecNef has the power to reformat perceptual representations, threat reactions, and affective ratings by rewarding the spontaneous emergence of a target pattern. Evidence: The ability to sculpt neural activity in fear responses to specific conditioned stimuli has been proven in proof-of-concept studies despite the lack of explicit memory reactivation.

In the context of TMDS, DecNef is mainly used in Phase 1(Mapping) and Phase 3 (Intervention). Neural fingerprints derived through MVPA can be used to detect the engram patterns of a candidate during mapping. In the process of intervention, DecNef gums the system against a reconsolidation-based restabilization process by strengthening competing neural states or depressing engram-related patterns. The main weakness of this method is that it relies upon the fMRI resolution, which is rather poor in relation to the sparseness of the engram representations.

5.2. Targeted Memory Reactivation (TMR) In Sleep: Cue-Driven Modulation of Consolidation and Updating

Memory traces are spontaneously reactivated during sleep in hippocampal-neocortical loops. TMR takes advantage of this fact and introduces the sensory signals associated with a learned memory when a person is in slow-wave sleep, which predisposes replay processes. This intervention can either strengthen or weaken or qualitatively alter memory expression depending on the parameters of timing and cues [

60].

TMR is especially appropriate to Phase 3 (Interference). In the conditions of destabilisation induced by TMDS, cue-induced reactivation during sleep may guide a replay in a downscaling or overwriting direction, particularly in domains of emotional or associative memory. Limitations are interindividual differences in the transitions between sleep stages and the inability to accurately determine the time to match reconsolidation periods [

61,

63].

5.3. Optogenetically Inspired Principles: Proof-of-Concept for Engram-Specific Modulation

The study of optogenetics has explained two basic facts about memory:

Although optogenetics is not clinically viable yet, the concepts are used to design TMDS. The LTD induced optogenetically provides a Phase 3 (Intervention) mechanistic analogue to show that target weakening of a given ensemble is enough to cause functional deletion. In addition, the optogenetic recovery of silent engrams highlights the need for Phase 4 (Verification) to confirm the actual erasure as opposed to suppression [

64,

65,

66].

5.4. Non-Invasive Neuromodulation: Interfering with Coordinated Activity to Impair Restabilisation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) are neuromodulation devices that are able to adjust network synchrony, excitability, and phase coupling. As an example, theta-frequency tACS can interfere with hippocampal-prefrontal coherence, an essential element in fear memory reconsolidation.

Regarding the TMDS, the techniques can assist Phase 3 by disrupting the coordinated oscillatory patterns of the engram restabilisation process. Nevertheless, they do not have a sufficiently high resolution to do any manipulations specific to engrams, and thus perform best in combination with narrow retrieval cues that limit the active subpopulation of neurons during intervention.

5.5. Further Research on Focused Ultrasound (FUS): Deep and Focal Neuromodulation with Translational Potential

Low-intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) grants the possibility to control deep brain structures with millimetre precision and non-invasively. Under the right stimulation conditions, FUS may produce a momentary inhibition or excitation of neural groups, adjustment of synaptic plasticity, or delivery of drugs by opening the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Repeated BBB opening is shown to be safe and produces a modulation effect upon fear circuitry, as confirmed by clinical studies.

In the case of TMDS, FUS is one of the best Phase 2 (Destabilisation) and Phase 3 (Intervention). During Phase 2, prediction error can be intensified in response to transient disruption of particular connectivity, amygdala-prefrontal, whilst destabilisation can be strengthened. Phase 3 Localised BBB opening allows direct delivery of agents like propranolol, rapamycin or next-generation protein synthesis blockers to the active engram region. Its major issues are the maintenance of thermal safety margins, the reduction of off-target acoustic impact, and the real-time control of the delivery of FUS in order to synchronise the delivery of FUS with an engram activation triggered by its retrieval.

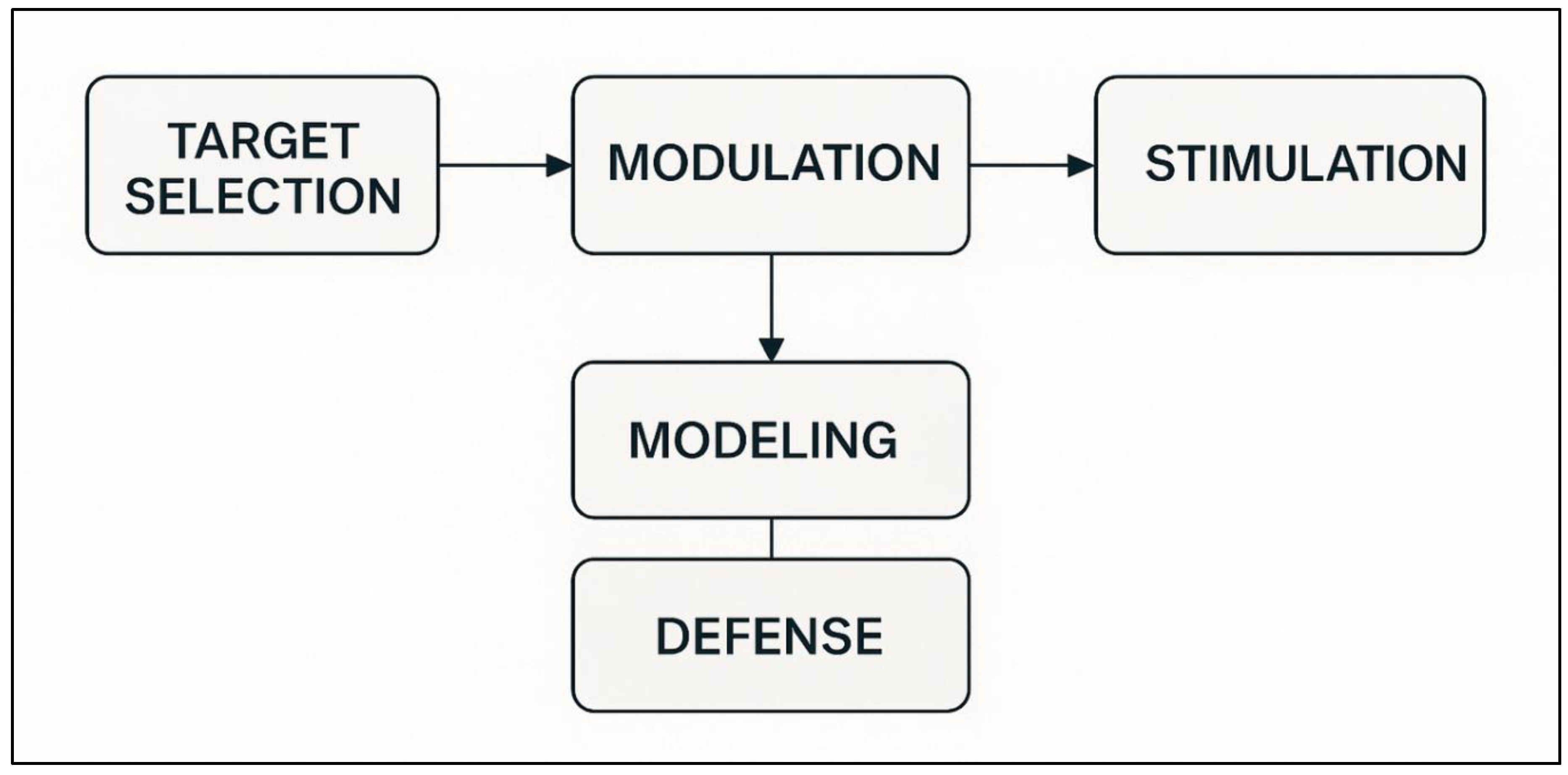

6. The Conceptual Architecture of the TMDS (4-Phase Framework)

The theoretical basis of a technology aimed at selectively attenuating or destroying maladaptive memories is the advances in the neuroscience of forgetting, engram dynamics and reconsolidation. The Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS) converts these empirical findings into a practical, four-step model: (1) identification of the target memory, (2) induction of an artificially controlled period of destabilisation, (3) focused interference to hamper reconsolidation and (4) deletion verification. Despite its current conceptual base, the framework will be based on the biological principles that are already tested and the latest technologies of neuromodulation.

Figure 4.

TMDS Architecture.

Figure 4.

TMDS Architecture.

TMDS begins with the identification of the engram, which is necessary to reduce the size of the neural ensemble involved in the intervention. Direct molecular tagging is limited only to animal models; however, methods compatible with humans, like multivoxel pattern analysis and decoded neurofeedback, can be used to form probabilistic neural fingerprints of the target memory. Engram activation further becomes selective to the relevant associative network by retrieval protocols mediated by virtual reality or by the modulation of sensory cues. These approaches do not accurately capture engrams but offer a feasible level of specificity to be used in translation.

After a reliable engagement of a memory, TMDS will then cause controlled destabilisation. This step is dependent on the development of an accurately tuned prediction error level, neither too large to induce GluA2 -AMPAR endocytosis and ubiquitin -proteasome -system -mediated proteolysis, nor too large to cause extinction learning. VR-induced mismatch signals, partial reinforcement errors, or controlled distortions of hippocampal-prefrontal coherence (e.g., using focused ultrasound) are possible ways of realising such an intermediate error of prediction. Automatic reactivity, changes in neural pattern, and pupil dilation are physiological indicators that provide real-time information on whether destabilisation has taken place. This step is the most substantiated part of TMDS mechanistically because the molecular machinery that controls memory lability is well-characterised.

The third element is a direct interference during the period of reconsolidation, the period at which the weakened or inhibited destabilised trace may be achieved. Modes of interference include pharmacological, neuromodulatory, or replay-based modes of interference. Propranolol is able to suppress the emotional reaction of fear memories, and mTOR inhibitors like rapamycin can block the process of de novo protein synthesis needed to maintain the restitution. The temporary opening of the blood-brain barrier in a localised area could be achieved with focused ultrasound, allowing the delivery of drugs that are limited to a localised foci or engram. e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation, or theta-phase transcranial alternating current stimulation. Non-invasive neuromodulation may interfere with coordinated oscillatory activity (e.g., reconsolidation) that is required. Sleep-based targeted memory reactivation can also induce additional bias on replay to downscale. These techniques differ in their invasiveness and specificity, but all focus on inhibiting the molecular cascade that would otherwise re-stabilise the engram.

Lastly, TMDS has a verification phase that is used to filter out the event of actual deletion besides transient suppression. Preliminary evidence of deletion is through behavioural tests, e.g., absence of spontaneous recovery, reinstatement or context-dependent renewal. The result of neural confirmation is the representational similarity analysis, reduced reactivation of neural fingerprints, and the lack of engram-like activity, even with the dominating retrieval cues. The ability to re-instatement of suppression-induced silent engrams is a property that requires TMDS to be multi-level validated to ensure that the underlying connectivity or excitability of the trace has not been permanently damaged.

The combination of these stages creates a logical translational extension between fundamental processes of forgetting and useful technologies in the field of therapeutic memory restructuring. Some of them, including destabilisation through prediction error and interference as a result of pharmacological reconsolidation, have strong empirical support. The other elements, such as accurate engram mapping, focal drug delivery, and universal neural biomarkers of deletion, are developing issues. As a result, TMDS is more of a blueprint than a complete technology, just a mechanism that defines where current ability is consistent with biological feasibility and where innovation must be undertaken further.

Table 2.

The TMDS Clinical Pipeline.

Table 2.

The TMDS Clinical Pipeline.

| Phase |

Objective |

Biological State |

Technological Vector |

Success Metric |

| 1. Mapping |

Identify Trace |

Stable Engram |

fMRI + MVPA |

>90% Classifier Accuracy |

| 2. Destabilization |

Open Window |

Labile (GluA2 Endocytosis) |

VR + Prediction Error |

Moderate Arousal Spike |

| 3. Intervention |

Block Restabilization |

Protein Synthesis Inhibition |

FUS + Rapamycin / DecNef |

Synaptic Depotentiation |

| 4. Verification |

Confirm Deletion |

Silent / Erased |

Spontaneous Recovery Test |

No Reinstatement |

7. Ethical Analysis: The Rights to Memory and Mind

The possibility of selectively altering or eliminating the memories of humans creates immense ethical and governance issues. In contrast to the general forms of therapeutic intervention, memory editing changes the source of individual identity, emotional continuity, and narrative integrity. Since TMDS integrates molecular destabilisation, circuit modulation, and targeted pharmacology into a coordinated system, the ethical reflection will have to go beyond abstract issues of neurotechnology and look at the actual impacts that each step of the deletion process will have.

One of the key concerns is cognitive liberty, the right to regulate individual mental states and neural activities. TMDS gets in at the very point when a memory is in a state of instability and uniquely vulnerable, and therefore puts an inordinately heavy responsibility upon making sure that the consent is informed, voluntary, and reversible. Since reconsolidation blockade is capable of causing permanent alterations, one should have a full understanding of what elements of a memory can be modified: emotional, contextual or semantic. This is not limited to the normal disclosure of medical information but also to uncertainty about boundary conditions, risk of partial deletion and the possibility of creation of silent engrams.

The second challenge is narrative identity. The continuity provided by autobiographical memory is that which assists people to conceptualise themselves; by picking and choosing portions of that text, we may threaten to disrupt personal continuity. Though TMDS will, in the meantime, hardly successfully remove the intricate episodic frameworks, even valence-specific deletion (e.g., eliminating the emotive content of a traumatic memory) will reconfigure moral appraisals, individual growth paths, and subsequent decision-making. The therapeutic usage will therefore require a careful evaluation of whether the alteration will improve the well-being without compromising on reflective authenticity.

Another issue connected to it is the mental integrity - the right not to have the psychological architecture changed without a reason. As TMDS operates based on the intentional destabilisation of neural representations, TMDS makes it difficult to draw the line between healing and manipulation. Protective measures should make sure that interventions are not used in a coercive manner, in a law-related environment, in the military, or in relationships where the power balance is established. A possible advantage of taking advantage of the reconsolidation window to have a non-therapeutic influence makes this risk ethically important.

The deletion of memory also overlaps with the obligation to remember, especially in a situation of social responsibility or justice. In the case of violence victims, full removal of emotional or situational organisation of traumatic records may act as an obstacle to testimony, accountability, or healing of the society in the long term. Any application of TMDS has to be based on the premise of weighing personal therapeutic utility against more expansive moral/civic considerations of changing historically resonant memories.

Lastly, governance has to deal with accuracy, transparency, and oversight. Since TMDS is used at both molecular and circuit, and computational levels, it becomes essential to ensure the real deletion. The lack of differentiation between suppression and erasure may confuse the therapeutic consequences or the false hope that it is possible to take the negative memories out safely. Regulatory frameworks, then, should require stringent post-intervention evaluations, periodic monitoring, as well as straightforward reporting requirements.

All these factors suggest that the Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS) cannot be assessed as a biomedical instrument only. It is a transformation of the neuroscience ethical environment, which requires the creation of new protective measures to safeguard autonomy, identity and social integrity and allow the alleviation of debilitating memory-based disorders. Since the technological base of TMDS is coming of age, the governance frameworks need to be adjusted accordingly so that the practice of memory editing is not based on the opportunistic use of human-rights-centred conceptions but instead on human-rights-based principles.

8. Conclusion

It is the modern neuroscience of forgetting that has shown that memories are dynamic constructs and not fixed entities, but are influenced by the molecular turnover, reconfiguration of synapses and competition between circuits. Caused by Rac1 actin remodelling, UPS-dependent degradation, GluA2-AMPAR endocytosis, and Arc-mediated synaptic weakening, all these processes provide the cellular machinery in the course of which engrams become unstable. These processes, in their turn, work in the distributed networks, the accessibility of which is regulated by sparse coding, remodelling induced by neurogenesis, and thalamocortical coordination. The studies on reconsolidation show that remembering not only exposes the memory but also temporarily presents it to change when it is evoked at moderate errors of prediction. A combination of these principles places forgetting not in opposition to retention but in a biologically conserved position of adaptive updating (and possibly of therapeutic deletion).

The Targeted Memory Deletion System (TMDS) suggested in this review is a continuation of these findings. TMDS proposes a viable translational course towards selective modification of maladaptive memories by incorporating engram identification, controlled destabilisation, interference during the reconsolidation window and rigorous verification. Some of the components already tested are validated, including prediction-error-dependent lability and pharmacological reconsolidation blockade, but some involve large amounts of innovation. Real-time and high-resolution engram mapping, safe and focal neuromodulatory delivery, and universal biomarkers of actual deletion are also still critical issues of clinical implementation.

There are four directions that future research should focus on. To begin with, the limitation of specificity in memory editing will be outlined by improving human-compatible identification of engrams using the tools of neuroimaging, representational modelling, and activity-informed decoding. Second, elaborating precision destabilisation techniques, including algorithmically-adjusted prediction-error paradigms that are accompanied by physiological monitoring, will enhance reliability in people and memory types. Third, optimising targeted delivery technologies, such as next-generation focused ultrasound, and localised pharmacology will ensure that interventions can be engram-selective, but not global disruptors. Lastly, the creation of strong verification criteria is necessary in order to delineate what is real erasure versus suppression, and as such, avert the interpretation of the clinical outcomes and safeguard long-term safety.

The ethical implications of memory editing technologies are enormous, but the progress of this technology is not hypothetical or far-off. With the evolution of the mechanistic knowledge of forgetting and the development of new technologies becoming more accurate, the future of the deliberate forced removal of memory becomes even more concrete. TMDS offers a model of responsible development of such interventions, which is based on scientificity, clinical utility, and ethical protection of autonomy and narrative identity.

This review will place active forgetting as the conceptual framework through which the basic memory processes are mediated to future therapeutic technologies by combining molecular biology, systems neuroscience, reconsolidation theory, and neurotechnology. The difficulty herein remains to put this mechanistic knowledge into devices that would selectively transform the memory whilst maintaining the structural integrity of the mind.

References

- Shuai Y, Lu B. Hippocampal Activation of Rac1 Regulates the Forgetting of Object Recognition Memory. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10838. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27593377/.

- Shuai Y, Lu B. Roles of Rac1-Dependent Intrinsic Forgetting in Memory-Related Brain Disorders: Demon or Angel? Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1172371. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10341513/.

- Nader K, Schafe GE, LeDoux JE. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature. 2000;406(6797):722–726. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair AH, Barense MD. Prediction Error and Memory Reactivation: How Incomplete Reminders Drive Reconsolidation. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42(10):733–745. Available from: https://barense.psych.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019_Sinclair_Barense_TINs.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Merlo E, Milton AL, Goozée ZY, Theobald DE, Everitt BJ. Reconsolidation and extinction are dissociable and mutually inhibitory processes: Behavioral and molecular evidence. J Neurosci. 2014;34(7):2422–2431. [CrossRef]

- Penn AC, Zhang CL, Georges F, Royer L, Breillat C, Hosy E, et al. GluA2-dependent AMPA receptor endocytosis and the decay of long-term potentiation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1633):20130141. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2013.0141. [CrossRef]

- Shuai Y, Hu Y, Qin H, Campbell RA, Zhong Y. Scribble scaffolds a signalosome for active forgetting. Nature. 2015;520(7548):420–423. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27263975/.

- Gao Y, Li M, Chen W, Li H, Li W. Inhibition of Rac1-dependent forgetting alleviates memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease models. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14(1):20. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6776562/.

- Frankland PW, Köhler S, Josselyn SA. Hippocampal neurogenesis and forgetting. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(9):497–503.

- Jarome TJ, Helmstetter FJ. The ubiquitin–proteasome system as a critical regulator of synaptic plasticity and long-term memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;105:107–116. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3786694/. [CrossRef]

- Reichelt AC, Lee JLC. Memory reconsolidation in humans: A sensitive period for updating memory. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20(1):168–176.

- Stemerding S, Stibbe A. Demarcating the Boundary Conditions of Memory Reconsolidation: An Unsuccessful Replication. Learn Mem. 2024. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Demarcating-the-boundary-conditions-of-memory-An-Stemerding-Stibbe/ec945dcf2895a79df4ea5545131d9971a11dc1f0.

- Kroes MCW, Schiller D, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA. Targeting reconsolidation: A route to modify emotional memories. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1369(1):17–28. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5424072/.

- Ryan TJ, Roy DS, Pignatelli M, Arons A, Tonegawa S. Memory. Engram cells retain memory under retrograde amnesia. Science. 2015;348(6238):1007–1013. [CrossRef]

- Nabavi S, Fox R, Proulx CD, Lin JY, Tsien RY, Malinow R. Engineering a memory with LTD and LTP. Nature. 2014;511(7509):348–352. [CrossRef]

- Josselyn SA, Frankland PW. Memory Allocation: Mechanisms and Function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2018;41:389–413. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd JD, Bear MF. New views of Arc, a master regulator of synaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):279–284. [CrossRef]

- Pastuzyn ED et al. The neuronal gene Arc encodes a repurposed retrotransposon Gag protein that mediates intercellular RNA transfer. Cell. 2018;172(1–2):275–288.e18. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Kwon JT, Kim HS. Engram competition and systems consolidation as mediators of forgetting. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3587.

- Guo N, Soden ME, Herber C, Kim MT, Besnard A, Lin P, et al. Robustness of retrieval and updating of fear memory via optogenetic rewiring of hippocampal engram circuits. Neuron. 2018;97(1):1–17.

- Dunsmoor JE, Niv Y, Daw ND, Phelps EA. Rethinking Extinction. Neuron. 2015;88(1):47–63. [CrossRef]

- Kroes MCW, Fernández G. Dynamic memory updating: prediction error and reconsolidation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;23(3):1–7.

- Gisquet-Verrier P, Riccio DC. Memory integration: An alternative reconsolidation hypothesis. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:21.

- Schiller D, Monfils MH, Raio CM, Johnson DC, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA. Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms. Nature. 2010;463(7277):49–53. [CrossRef]

- Barrett AB, Barnett L, Seth AK. Multivoxel pattern analysis for engram identification: methodological considerations. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(8):542–554.

- Rasch B, Born J. About sleep’s role in memory. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(2):681–766.

- Oudiette D, Paller KA. Upgrading memory replay during sleep. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(2):145–147.

- Folloni D, Verhagen L, Mars RB, Fouragnan E, Constans C, Aubry JF, et al. Manipulation of subcortical and deep cortical activity in humans with transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation. Neuron. 2020;109(2):236–248.e5. [CrossRef]

- Redondo RL, Morris RG. Making memories last: the synaptic tagging and capture hypothesis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(1):17–30. [CrossRef]

- Liu X et al. Optogenetic stimulation of a hippocampal engram activates fear memory recall. Nature. 2012;484:381–385.

- Besnard A, Sahay A. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and mental health: A systematic review. Neuron. 2021;109(10):1507–1528.

- Davis RL, Zhong Y. The Biology of Forgetting—A Perspective. Neuron. 2017;95(3):490–503. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28772119/.

- Hardt O, Nader K, Nadel L. Decay happens: The role of active forgetting in memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(3):111–120. [CrossRef]

- Lee JLC, Nader K, Schiller D. An update on memory reconsolidation updating. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21(7):531–545. [CrossRef]

- Ji J, Maren S. Hippocampal involvement in contextual modulation of fear extinction. Hippocampus. 2007;17(9):749–758. [CrossRef]

- Likhtik E, Paz R. Amygdala–prefrontal interactions in (mal)adaptive learning. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38(3):158–166. [CrossRef]

- Deisseroth K. Optogenetics: 10 years of microbial opsins in neuroscience. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(9):1213–1225. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi-Takagi A et al. Labelling and optical erasure of synaptic memory traces in the motor cortex. Nature. 2015;525:333–338. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell C, Nolan MF. Tuning synaptic weights for biasing memory specificity. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(1):9–10.

- Ito HT et al. A prefrontal–thalamo–hippocampal circuit for goal-directed spatial navigation. Nature. 2015;522:50–55.

- McAvoy K, Sahay A. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and memory homeostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):233–255.

- Richards BA, Frankland PW. The persistence and transience of memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(2):109–118.

- Anderson MC, Hulbert JC. Active forgetting: Adaptation of memory by prefrontal control. Annu Rev Psychol. 2021;72:1–36. [CrossRef]

- Anderson MC, Hanslmayr S. Neural mechanisms of motivated forgetting. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(6):279–292. [CrossRef]

- Kroes MCW, Fernández G. How to erase memory: A practical review of reconsolidation interference. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;100:17–31.

- Shapiro ML, Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus as a memory map: Neural representation of space in rats. Nature. 1997;387:272–276.

- Oudiette D, Antony JW, Creery JD, Paller KA. The role of memory reactivation during wakefulness and sleep in strengthening memory. Curr Biol. 2013;23(19):R848–R850.

- Paller KA et al. Memory reactivation and consolidation during sleep. Learn Mem. 2021;28(11):395–403. [CrossRef]

- Ngo HV et al. Auditory closed-loop stimulation of sleep slow oscillations enhances memory. Neuron. 2013;78(3):545–553.

- Tuszynski MH, Weiner L, Fraenkel D, et al. FUS-mediated blood-brain barrier opening enhances neuroplasticity. J Neurosci. 2022;42(1):68–79.

- Sadtler PT et al. Neural constraints on learning. Nature. 2014;512(7515):423–426. [CrossRef]

- Shibata K, Watanabe T, Sasaki Y, Kawato M. Perceptual learning incepted by decoded fMRI neurofeedback. Science. 2011;334(6061):1413–1415. [CrossRef]

- Taschereau-Dumouchel V, Kawato M, Lau H. Multivoxel neurofeedback modulates confidence judgments while avoiding stimulus presentation. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2695.

- Fox MD, Buckner RL. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110(6):1528–1546.

- Reinhart RMG, Nguyen JA. Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(5):820–827. [CrossRef]

- Grossmann T. The neurobiology of human infant memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(7):307–313.

- Eichenbaum H. On the integration of space, time, and memory. Neuron. 2017;95(5):1007–1018. [CrossRef]

- Squire LR, Alvarez P. Retrograde amnesia and memory consolidation: A neurobiological perspective. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5(2):169–177. [CrossRef]

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Fear extinction as a model for psychotherapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):61–70.

- Tovote P, Fadok JP, Lüthi A. Neuronal circuits for fear and anxiety. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(6):317–331. [CrossRef]

- Armony JL, LeDoux JE. How the brain processes emotional information. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12(2):181–194. [CrossRef]

- Delgado MR, Olsson A, Phelps EA. Extending animal models of fear conditioning to humans. Biol Psychol. 2006;73(1):39–48. [CrossRef]

- Sah P, Faber ESL, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. The amygdaloid complex: Anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(3):803–834. [CrossRef]

- Bechmann M, Brand M. Autobiographical memory disturbance in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(10):567–582.

- Parfit D. Reasons and Persons. Oxford University Press; 1984.

- Schechtman M. The Constitution of Selves. Cornell University Press; 1996. [CrossRef]

- Metzinger T. Minimal phenomenal experience and self-model theory. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2020;375:20190367.

- Floridi L. The Logic of Being Informed. Synthese. 2011;190(20):3513–3520.

- Ienca M, Andorno R. Towards new human rights in the age of neuroscience and neurotechnology. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2017;13(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Bublitz JC, Merkel R. Crimes against minds: Mental interference and human rights. Crim Law Philos. 2014;8:51–77.

- Lavazza A. Erasing traumatic memories: ethics of reconsolidation therapies. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1170.

- Farah MJ. Neuroethics: The ethical, legal, and societal impact of neuroscience. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:571–591. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee A. The ethics of neuroenhancement. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:435–444.

- President’s Council on Bioethics. Beyond Therapy: Biotechnology and the Pursuit of Happiness. Washington, DC; 2003.

- McKinnon MC, Palombo DJ, Nazarov A, Kumar N, Kaniasty K, Freiburger O, et al. Autobiographical memory and PTSD. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(9):645–654.

- Dunn BD, Dalgleish T, Lawrence AD. The somatic marker hypothesis and memory. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(1):1–29.

- Brewin CR. Theoretical foundations of intrusive images in PTSD. Psychol Rev. 2014;121(3):338–363.

- Lonergan MH, Olivera-Figueroa LA, Pitman RK, Brunet A. Propranolol and trauma: a meta-analysis of emotional memory reconsolidation interference. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):1–10.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).