1. Introduction

Sea buckthorn (

Hippophae rhamnoides L.) is a dicotyledonous woody oil plant belonging to the Elaeagnaceae family. It grows in the wild across much of Eurasia, from the Himalayas and Central Asia to Russia and most of Europe [

1]. It is cultivated in China, Russia, Romania, Mongolia, and several other countries [

1]. Its fruit and leaves contain various biologically active compounds, including carotenoids, flavonoids, tocopherols, essential fatty acids, and vitamins C, K, and E [

2,

3]. Due to their unique biochemical composition, sea buckthorn extracts exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties, as well as protective effects on the nervous and cardiovascular systems [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Additionally, sea buckthorn is highly adaptive to adverse environmental conditions, such as saline soils and low temperatures, which makes it a promising candidate for protecting against soil erosion, stabilizing sand dunes, and reclamating land [

1,

8,

9].

Despite the great potential for using of sea buckthorn fruits in food and pharmaceuticals, modern breeding approaches, such as marker-assisted and genomic selection, are not widely used [

1]. This issue is likely due to the insufficient genetic research on this plant. Only a few DNA markers have been proposed for the

Hippophae species. These markers are predominantly associated with the sex of plants (male or female) and frequently work only on specific populations [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Accurate and complete genome assemblies are essential for many plant studies, including transcriptomic analyses, gene family identification, repetitive element representation estimation, valuable trait DNA marker development, genome editing, and pangenome creation [

17,

18,

19,

20]. In recent years, tremendous advances have occurred in third-generation sequencing technologies, providing tools for obtaining continuous, chromosome-level plant genome assemblies [

21,

22,

23,

24]. These advances have enabled high-quality genome assemblies of

H. rhamnoides and other

Hippophae species, predominantly obtained using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) platform, with the size from 716 to 1453 Mb [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. These assemblies are necessary for the molecular genetic studies of sea buckthorn and for using genetic tools to breed this valuable oil crop. However,

Hippophae is characterized by high genetic diversity; even different subspecies of

H. rhamnoides, such as

H. rhamnoides ssp.

mongolica Rousi and

H. rhamnoides ssp.

sinensis Rousi, differ greatly in characteristics [

1]. The present study aimed to obtain the T2T (telomere to telomere) genome of

H. rhamnoides ssp.

mongolica from Russian breeding programs, which have traditionally focused on developing high-yielding varieties with large, high-oil fruits. We used the Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) platform for genome sequencing due to of the significant progress this technology has made in recent years. This progress has enabled the assembly of telomere-to-telomere (T2T) genomes, suggesting that ONT data can be used as effectively as PacBio data for genome assembly [

32,

33,

34,

35].

2. Results

2.1. De Novo Genome Assembly

DNA sequencing of the variety Triumf of H. rhamnoides ssp. mongolica on the ONT platform produced 155 Gb of raw reads with an N50 of 31.4 kb. Reads of at least 10 kb with Q10 or higher score (126 Gb in total) were then used for genome assembly with Hifiasm.

The obtained Triumf genome assembly was 1,171.9 Mb in length and consisted of 13 contigs. The chromosome number of

H. rhamnoides is known to be 2n = 24 [

36,

37]. Thus, we suggested that the genome was assembled into eleven complete chromosomes and one chromosome (Chr 3) consisting of two contigs. GC content of the Triumf genome assembly was 29.05%. The assembly had a high BUSCO score of 96.8%, with 85.3% of the BUSCOs being complete and single-copy, and 11.5% being complete and duplicated. The mapping rate of Illumina WGS reads (83.4 million 150+150 bp reads, NCBI SRA PRJNA1177110) to the Triumf genome assembly was high – 99.56%, and 94.69% of the assembly was covered by the Illumina reads. Repetitive elements accounted for 66.9% of the Triumf genome as determined by the k-mer analysis.

2.2. Comparison of Hippophae Genome Assemblies

We compared the obtained genome assembly of

H. rhamnoides ssp.

mongolica with the available assemblies of the genus

Hippophae. The Triumf assembly was longer than genome assemblies of most other

Hippophae species [

25,

26,

27,

29,

30,

31], but shorter than the

H. tibetana assembly from the study by Wang et al. [

28] (

Table 1). According to the contig N50 parameter, the Triumf assembly was the best among the available genome assemblies of

Hippophae species (as of 25 August 2025).

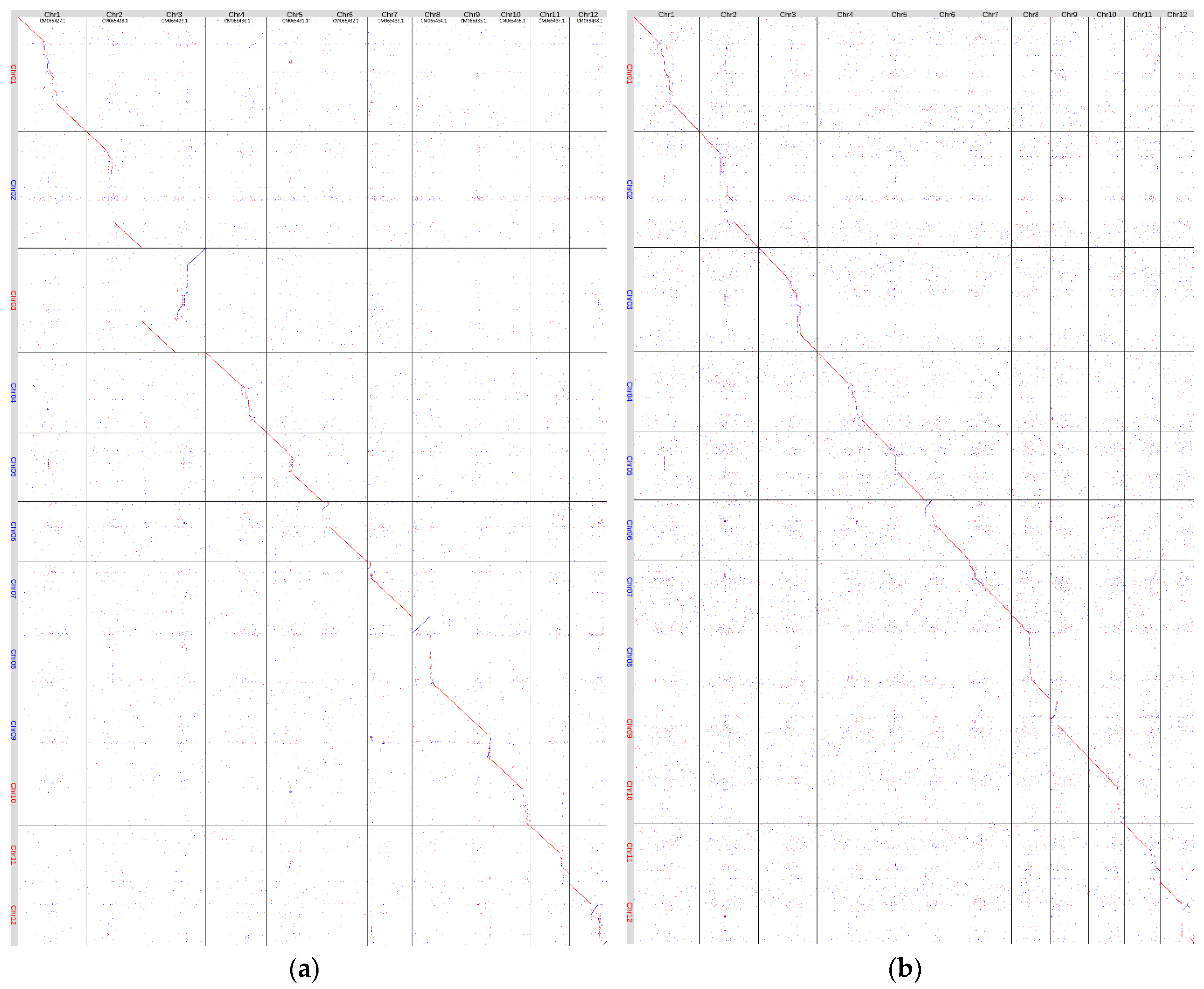

We compared the variety Triumf genome assembly (

H. rhamnoides ssp.

mongolica) with the genome assemblies of

H. rhamnoides ssp.

mongolica ×

H. rhamnoides ssp.

sinensis [

27] (NCBI, GCA_033030585.1,

Figure 1 (a)) and

H. rhamnoides [

26] (CNGB, CNP0001846,

Figure 1 (b)). The

H. rhamnoides ssp

. mongolica genome [

25] was unavailable for download (

http://hipp.shengxin.ren/, accessed on 25 August 2025). The alignment proved that 11 of 12 assembled contigs represented whole chromosomes, and the rest two contigs were scaffolded in Chr3. The regions of the Triumf genome assembly that made it longer than the other two available

H. rhamnoides assemblies were predominantly located in the likely centromeric and pericentric regions of chromosomes. The greatest differences in length were characteristic of chromosomes Chr1, Chr2, Chr3, Chr4, and Chr8.

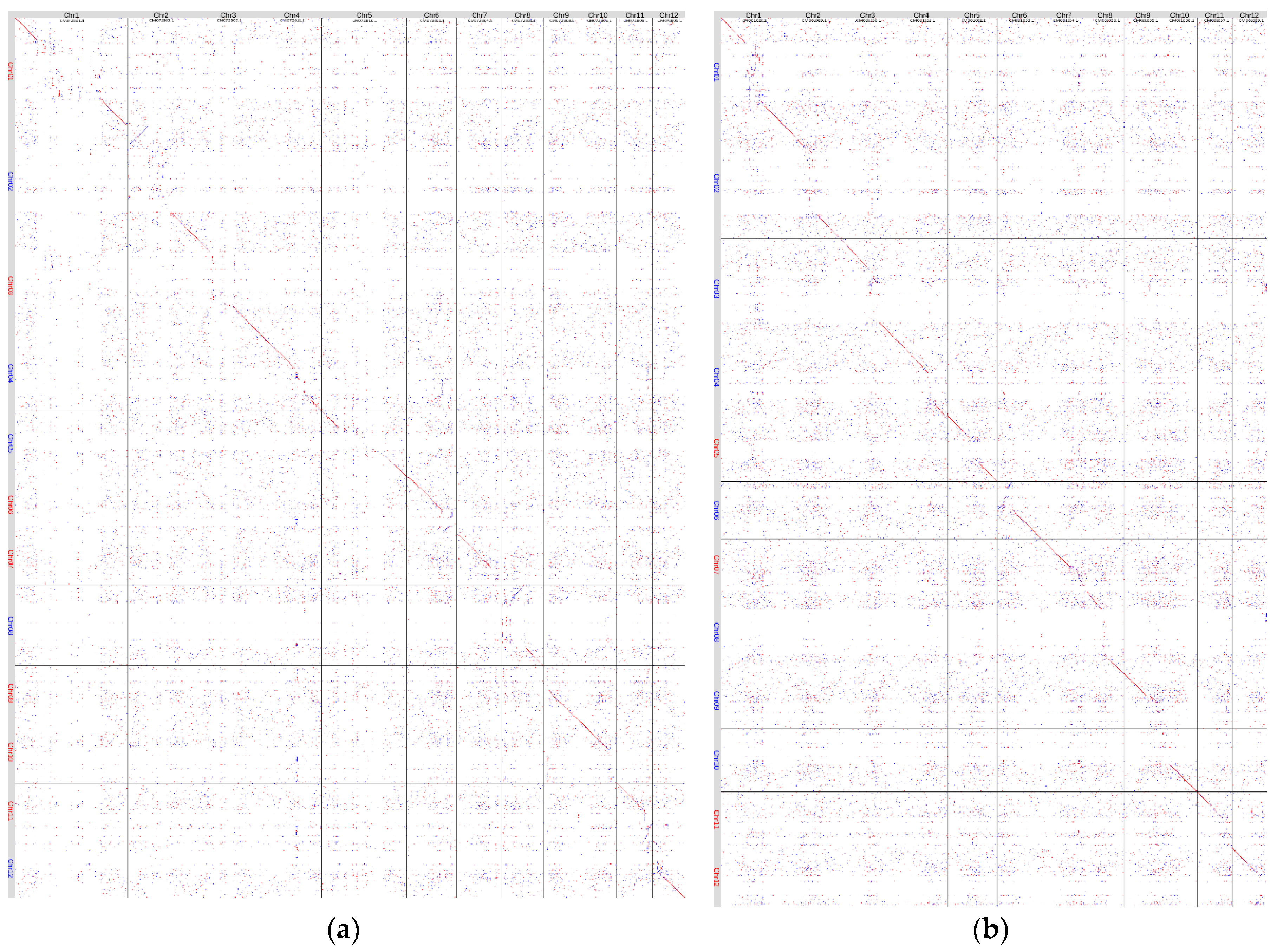

We also compared the genome assembly of Triumf with those of

H. tibetana [

29] (NCBI, GCA_037013495.1 (

Figure 2 (a)) and

H. gyantsensis [

30] (NCBI, GCA_030763125.1 (

Figure 2 (b)). Similar to the comparison with

H. rhamnoides genome assemblies, the main differences were present in the likely centromeric and pericentric regions of chromosomes. However, we also observed more noise – mapping of small fragments to other parts of the assemblies. This is likely because of the significant genetic differences between the species being compared.

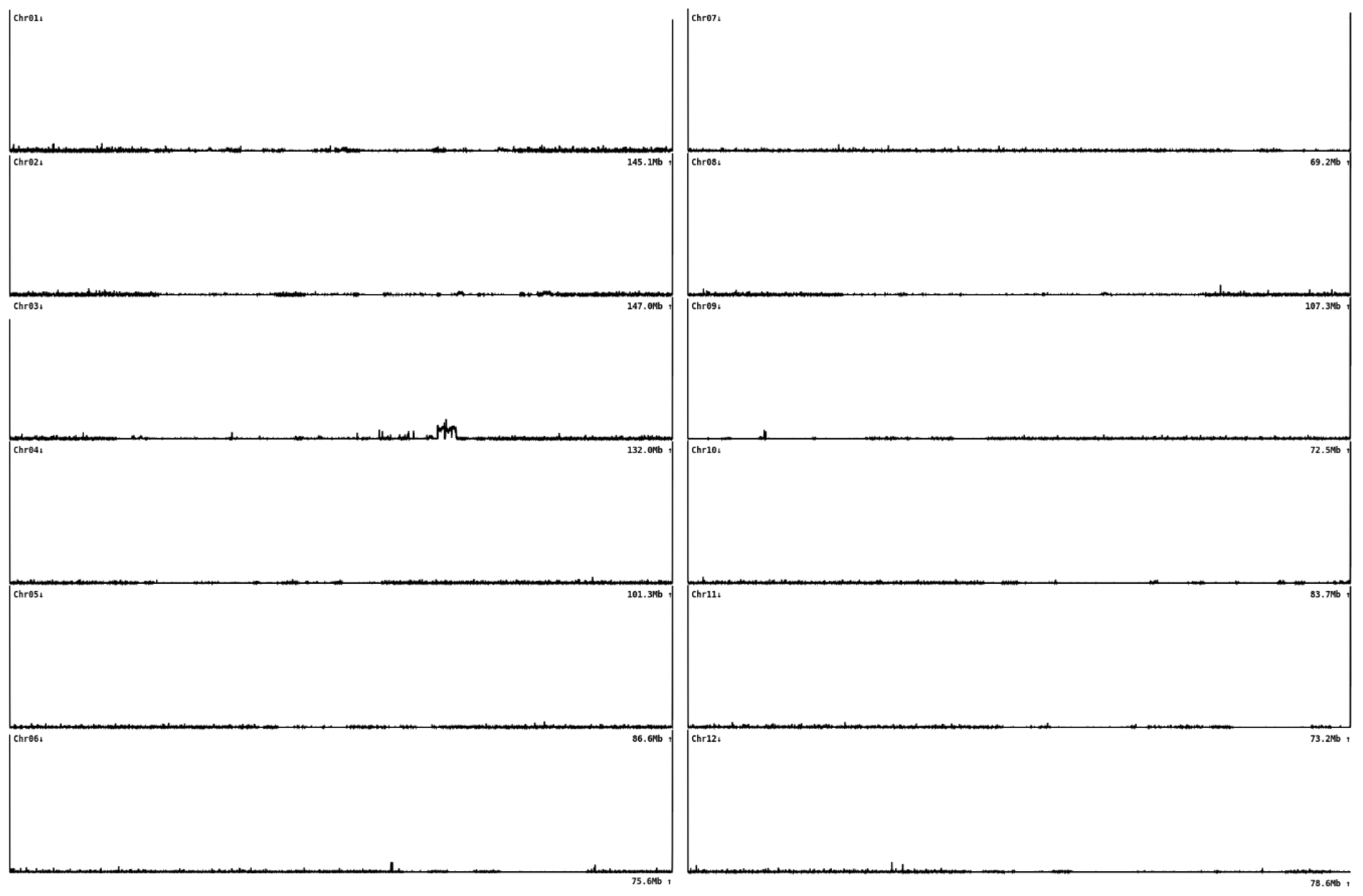

In the Triumf genome assembly, eleven chromosomes had pronounced telomeric repeats at both ends and were assembled as telomere-to-telomere (T2T); one chromosome (Chr 12) had telomeres only at one end (

Figure 3). This result supported the high quality of the Triumf genome assembly. We also analyzed the presence of telomeric repeats in other available sea buckthorn genome assemblies (

Figure S1). The absence of telomeric repeats at the ends of chromosomes or their mislocation were very common. This may indicate incomplete or erroneous assemblies.

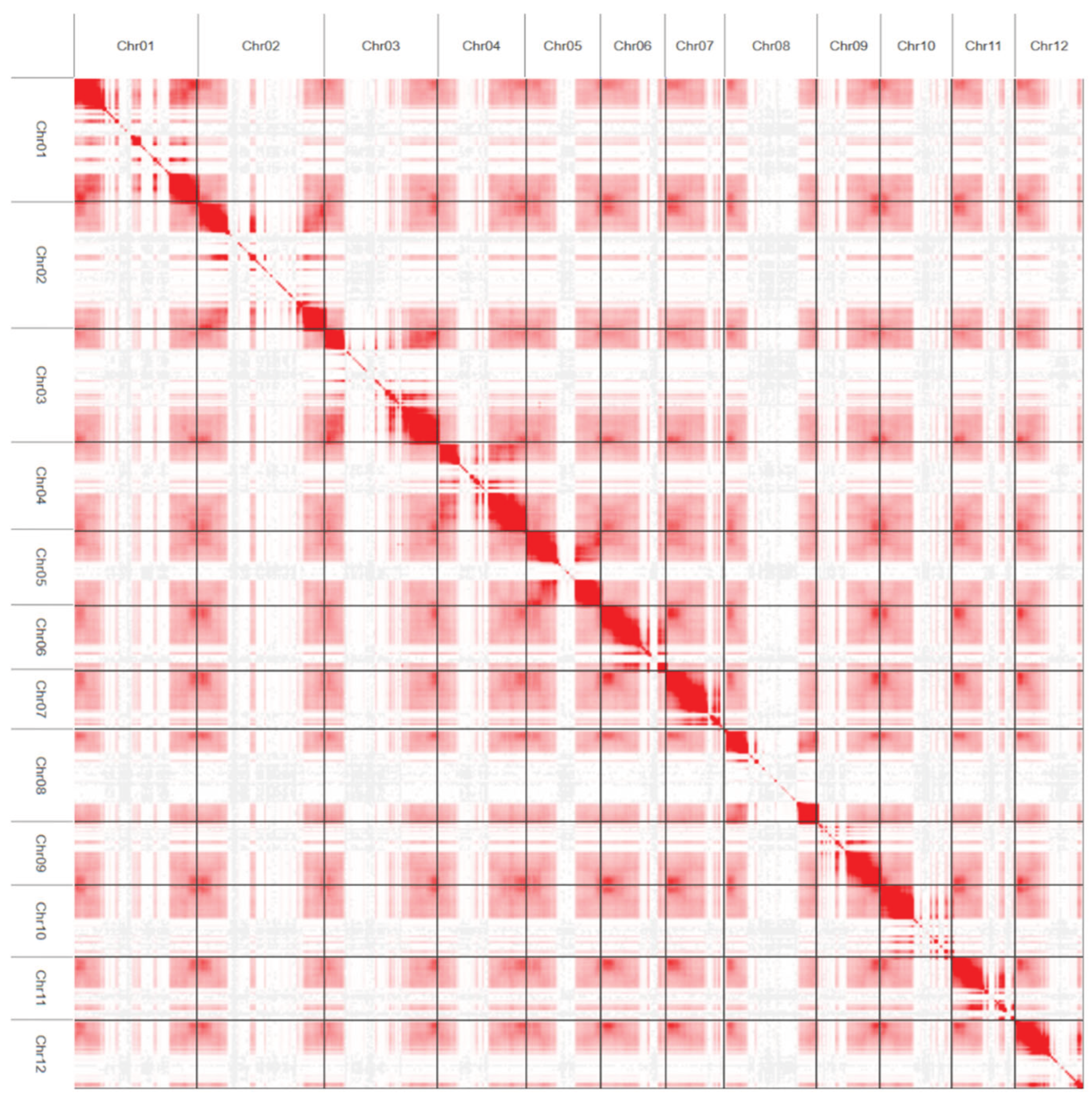

We generated 110.9 Gb of Hi-C genomic data (95× coverage) for the variety Triumf and constructed a Hi-C interaction heatmap (

Figure 4). The interaction heatmap showed no significant contacts outside the main diagonal, which confirmed the accuracy of the obtained genome assembly.

2.3. Annotation of the Variety Triumf Genome

Using genomic (NCBI SRA PRJNA1177110) and transcriptomic (NCBI SRA PRJNA1163394) data that we obtained earlier for the variety Triumf on the Illumina platform [

38], we predicted 24,761 gene and 27,949 transcript models in the obtained genome assembly.

A total of 2,259,619 repetitive elements were annotated, with a combined length of about 793.5 Mb, accounting for 66.9% of the assembly length. Retrotransposons comprised 41.5% of the length; DNA transposons accounted for 1.6%; and 21.8% of the assembly consisted of unclassified repetitive elements.

Among transposable elements, long terminal repeat elements presented 40.1% of the assembly length, with the Copia and Gypsy repeat families comprising 15.4% and 14.4%, respectively.

3. Discussion

We obtained a near-T2T genome assembly of the variety Triumf of H. rhamnoides ssp. mongolica using ONT sequencing and Hifiasm genome assembler optimized for ONT data. The initial assembly consisted of 13 contigs – eleven complete chromosomes and one chromosome in two parts, which were then scaffolded.

The Triumf genome assembly was longer than previous

H. rhamnoides assemblies [

25,

26,

27]: 1,171.9 Mb versus 730.5, 752.1, and 849.0 Mb. Comparison of the genome assembly of Triumf with those of other available

Hippophae species revealed that the main differences were associated with the centromeric and pericentric regions of chromosomes. The PacBio reads, predominantly used to assemble the

Hippophae genomes [

25,

26,

28], were shorter than the ONT reads [

39]. The shorter read length could result in problems when assembling extended genomic regions rich in repetitive sequences [

40]. Therefore, the centromeric and pericentric regions, which contain repeats [

41,

42], may be underrepresented in

Hippophae genomes initially assembled using only PacBio reads and then scaffolded with Hi-C data. To assemble the

Hippophae genomes from ONT reads, NextPolish [

30] and NextDenovo [

27] algorithms were used. However, as of 25 August 2025, ONT recommends using the Hifiasm (ONT) algorithm to obtain near-T2T genomes from standard ONT Simplex reads based on a recent study [

32] (

https://nanoporetech.com/news/breakthrough-algorithm-enables-partially-phased-near-telomere-to-telomere-assembly-using-standard-oxford-nanopore-simplex-reads, accessed on 25 August 2025). For the variety Triumf genome assembly, we used Hifiasm (ONT) and obtained excellent results. Furthermore, we generated ONT reads with a high N50 parameter (31.4 kb) and a significant proportion of reads exceeding 50 kb. This could positively impact the quality of the obtained assembly. Therefore, the variety Triumf assembly may contain repeated regions of the genome that were not assembled in previous

H. rhamnoides studies, surpassing previous assemblies in contiguity. We also obtained Hi-C reads and the contact map confirmed the accuracy of the Triumf genome assembly.

The analysis of telomeric repeats, which are located at the ends of chromosomes, also supported the high quality of the variety Triumf genome assembly. Eleven of the twelve chromosomes had telomeres at both ends, and one chromosome had a telomere at one end. In contrast, analysis of other Hippophae genome assemblies revealed errors in the location of telomeric repeats (i.e., within the chromosomes rather than at their ends) or their near absence. This discrepancy may be because of the initial incompleteness of the genome assemblies followed by merging contigs into scaffolds using Hi-C data.

T2T genomes are becoming the new standard for genome assemblies, not only for model organisms but also for a wide range of crop species. T2T genomes provide insights into genome organization and function, the distribution of repetitive elements, polyploid features and evolution, genetic diversity, and host-pathogen interactions [

18,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Thus, we obtained a near-T2T genome of H. rhamnoides ssp. mongolica variety Triumf using only ONT sequencing data. It became possible due to significant advancements in ONT technology and genome assembly tools. The variety Triumf was created as a part of the Russian breeding program and differs from the H. rhamnoides genotypes used in previous genome studies. The Triumf genome can be useful for identifying differences between genetically distant genotypes at the whole-genome level. Furthermore, Triumf is a high-quality fruit variety, and its genome can be valuable for identifying gene variants that determine important characteristics of sea buckthorn fruits for food and pharmaceutical applications. The variety Triumf genome also provides a solid foundation for studying particular gene families, including their representation and structure. It is also an essential tool for various basic and applied studies, as well as for genome editing of H. rhamnoides.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. DNA Extraction and ONT Sequencing

The variety Triumf was selected for the study. It is characterized by high yields and large, cylindrical, red fruits with dense flesh, firm skin, and high carotenoid content.

Nuclei isolation was performed using the LN2 Plant Tissue Protocol (

https://www.pacb.com/wp-content/uploads/Procedure-checklist-Isolating-nuclei-from-plant-tissue-using-LN2-disruption.pdf, accessed on 25 August 2025) with some modifications. Young sea buckthorn leaves weighing 0.5 g were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in a mortar for 20 minutes. The resulting powder was transferred to 25 mL of ice-cold NIB buffer consisting of 1× HB buffer (10 mM Tris pH 9.4 (Diaem, Moscow, Russia), 80 mM KCl (Helicon, Moscow, Russia), and 10 mM EDTA (Diaem)), supplemented with 0.5 M sucrose (Merck, Rahway, NJ, USA), 1% Triton X-100 (Diaem), 1% β-mercaptoethanol (NeoFroxx, Einhausen, Germany), 2% PVP K30 (CDH, New Delhi, India), and 100 mM spermine and spermidine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The suspension was placed on ice and stirred on a rocker at 100 rpm for 15-20 minutes. Then, it was centrifuged at 3,000 g and 4 °C for 20 minutes. The supernatant was carefully removed and the precipitate was resuspended in 4 mL of a 36% iodixanol solution (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× HB buffer. The solution was then centrifuged for 30 minutes at 5,000 g and 4 °C. The upper phase was transferred to a new tube and resuspended in 12.5 mL of NIB buffer. The tube was then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3,000 g and 4 °C. The supernatant was then removed. Washing in NIB buffer was repeated one more time. The resulting precipitate was washed with 1 mL of HB buffer and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3,000 g and 4 °C.

To lyse the nuclei, the precipitate was transferred to 1 mL of Carlson buffer prewarmed to 65 °C containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5 (Diaem), 2% CTAB (Helicon), 1.4 M NaCl (Diaem), 1% PEG-8000 (PanReac AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany), 20 mM EDTA (Diaem), 3 μL β-mercaptoethanol (NeoFroxx), 1% PVP K30 (CDH), and 4 μL RNase A (100 mg/mL; 7,000 units/mL; Qiagen, Chatsworth, MD, USA). The mixture was incubated at 65 °C for one hour, then cooled to room temperature. Then, an equal volume of chloroform (Diaem) was added to the homogenate. The tube was gently inverted ten times until a homogeneous emulsion formed. The mixture was then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3,000 g and 4 °C. The aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a new tube, and the chloroform extraction procedure was repeated.

DNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with 0.7 volumes of isopropanol (VWR Chemicals, Radnor, PA, USA). The tube was then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3,000 g and 4 °C. The supernatant was subsequently removed. The DNA was air-dried for 2 minutes, dissolved in 2 mL of G-buffer (Blood & Cell Culture DNA Mini Kit, Qiagen), and 25 μL of proteinase K (>600 mU/mL; Qiagen) was added. The mixture was incubated at 56 °C overnight. Then, the DNA was purified using Blood & Cell Culture DNA Mini Kit columns (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The quality and concentration of the DNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Similarity of the DNA concentration values obtained by the two methods served as an additional criterion for sample purity. The sizes of the isolated DNA fragments were evaluated by electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel (Diaem).

The SQK-LSK114 kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) was used to prepare the DNA library for ONT sequencing. Genome sequencing was performed using a PromethION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) with two R10.4.1 flow cells (Oxford Nanopore Technologies).

4.2. Construction and Sequencing of Hi-C Library

Vacuum infiltration with formaldehyde was used to fix the chromatin. Next, nuclei were isolated from the fixed leaves as described above. At the final stage, the resulting precipitate was washed with PBS. According to the optimized protocol [

51], the following steps were performed: restriction with DpnII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA); biotin labeling with Biotin-15-dCTP (Biosan, Novosibirsk, Russia); and subsequent ligation of DNA fragments with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs). The DNA was then isolated using phenol-chloroform extraction. Additionally, DNA purification was performed using MagicPure DNA beads (Transgen, Beijing, China). Biotin was then removed from the unligated ends of the DNA fragments. The Hi-C library was prepared using the Qiaseq FX DNA kit (Qiagen) up to the amplification step. Next, Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (New England Biolabs) were used to enrich the biotinylated fragments. Finally, the obtained Hi-C library was amplified. The quality of the library was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the concentration was measured with a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequencing was performed on a NovaSeq X Plus instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with of 150 + 150 nucleotide reads.

4.3. Data Analysis

Basecalling of ONT data was performed using the Dorado software package (dorado basecaller v.1.0.2,

https://github.com/nanoporetech/dorado, accessed on 25 August 2025) with a minimum average read quality of Q10 (--min-qscore 10). The most accurate model, dna_r10.4.1_e8.2_400bps_sup@v5.2.0 (sup), was used for this purpose. The length and quality of the resulting ONT reads were assessed via NanoPlot (v.1.44.1) [

52].

The genome assembly was performed using the Hifiasm algorithm (v.0.25.0) [

32] with a parameter set optimized for ONT reads (--ont). The ONT reads were filtered to a minimum length of 10 kb. The following assembly parameters were used: --telo-m CCCTAAA.

Basic assembly parameters, such as length, number of contigs, etc. were obtained and visualized using QUAST (v.5.3.0) [

53]. BUSCO (v.5.8.3) [

54] was used to evaluate the completeness of the genome assembly using the eudicots_odb10 database of universal single-copy orthologs. BUSCO was used in the eukaryotic genomic data analysis mode (--genome).

Global alignment of the genome assemblies was performed using LAST (v.1639) [

55]. Only contigs 10 Mb or longer were considered for alignment. The --uRY128 option, which was designed for whole-genome comparisons, was used for alignment; initial matches between query and reference sequences were searched at ~1/128 of positions in each sequence. Only the best alignment for each reference contig was visualized.

The TIDK software package (v.0.2.64) [

56] was used to detect telomeric sequences in the assemblies. The CCCTAAA telomeric motif, characteristic of sea buckthorn, was searched and visualized.

Hi-C reads were aligned to the obtained Triumf genome assembly using bwa mem (v.0.7.19) [

57] with the following parameters: –5SP. The ligation site detection was performed using pairtools (v.1.1.3) [

58] following Omni-C pipeline recommendations (

https://omni-c.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html, accessed on 25 August 2025). Contact maps were generated with Juicer Tools (v.1.22.01) and visualized with Juicebox (v.1.11.08) [

59].

Illumina genome sequencing data (NCBI SRA PRJNA1177110, obtained for variety Triumf) were used to validate the assembly quality with the following approaches: read mapping using bwa mem (v.0.7.19) [

57] (accessed on 25 August 2025) and k-mer distribution analysis with Jellyfish (v.2.3.1) [

60]. For the k-mer analysis, the high count of histogram was set at 1,000,000 as recommended for highly repetitive genomes. Genome size and duplication rate estimation was performed with GenomeScope2 (v.2.0.1) [

61].

Repetitive genomic region annotation and genome masking were performed with RepeatModeler and RepeatMasker [

62]. RepeatModeler was used with the -LTRStruct option enabling the LTR structural discovery pipeline. Structural annotation of the assembly was performed with the Braker3 pipeline (v.3.0.8) [

63] using the Viridiplantae protein database [

64] and Illumina transcriptome sequencing data (NCBI SRA PRJNA1163394, obtained for variety Triumf).

Both the genome and transcriptome Illumina reads were trimmed and filtered with fastp (v.1.0.1) using default parameters [

65].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Density of telomeric repeats in the analyzed genome assemblies of Hippophae species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.V.M. and A.A.D.; performing experiments, N.L.B., E.N.P., V.V.B., V.L.K., N.M.B., D.A.K., and E.V.B.; data analysis, A.A.A., Y.A.Z., F.D.K., E.A.I., E.M.D., K.M.K., N.V.M., and A.A.D.; writing, A.A.A., E.N.P., N.V.M., and A.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available at NCBI under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1177110 (linked to BioSample SAMN46736376).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nybom, H.; Ruan, C.; Rumpunen, K. The Systematics, Reproductive Biology, Biochemistry, and Breeding of Sea Buckthorn-A Review. Genes 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesarova, Z.; Murkovic, M.; Cejpek, K.; Kreps, F.; Tobolkova, B.; Koplik, R.; Belajova, E.; Kukurova, K.; Dasko, L.; Panovska, Z.; et al. Why is sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) so exceptional? A review. Food research international 2020, 133, 109170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasniewska, A.; Diowksz, A. Wide Spectrum of Active Compounds in Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) for Disease Prevention and Food Production. Antioxidants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Ding, J.; Lu, S.; Wen, X.; Hu, J.; Ruan, C. Identification of the key flavonoid and lipid synthesis proteins in the pulp of two sea buckthorn cultivars at different developmental stages. BMC plant biology 2022, 22, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Wei, P.; Chai, X.; Hou, G.; Meng, Q. Phytochemistry, health benefits, and food applications of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.): A comprehensive review. Frontiers in nutrition 2022, 9, 1036295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; He, W.; Cao, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, C. Research progress of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 2024, 11, 1477636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatlan, A.M.; Gutt, G. Sea Buckthorn in Plant Based Diets. An Analytical Approach of Sea Buckthorn Fruits Composition: Nutritional Value, Applications, and Health Benefits. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stobdan, T.; Dolkar, P.; Chaurasia, O.; Kumar, B. Seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) in trans-Himalayan Ladakh, India. Defence Life Science Journal 2017, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.G.; He, N.X.; Huang, H.L.; Fu, X.M.; Zhang, Z.L.; Shu, J.C.; Wang, Q.Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, G.; Zhu, M.N.; et al. Hippophae rhamnoides L.: A Comprehensive Review on the Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytonutrients, Health Benefits, Quality Markers, and Applications. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2023, 71, 4769–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Norbu, N.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Qiong, L. Development of sex-specific molecular markers for early sex identification in Hippophae gyantsensis based on whole-genome resequencing. BMC plant biology 2024, 24, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhang, W.; Qiong, L. Development and validation of sex-linked molecular markers for rapid and accurate identification of male and female Hippophae tibetana plants. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 19243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ruan, C.J.; Guan, Y.; Shan, J.Y.; Li, H.; Bao, Y.H. Characterization and identification of ISSR markers associated with oil content in sea buckthorn berries. Genetics and molecular research: GMR 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korekar, G.; Sharma, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Meenu; Bisht, N.C.; Srivastava, R.B.; Ahuja, P.S.; Stobdan, T. Identification and validation of sex-linked SCAR markers in dioecious Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Elaeagnaceae). Biotechnology letters 2012, 34, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Tan, X.; Tso, N.; Shang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Qiong, L. Development and application of sex-specific indel markers for Hippophae salicifolia based on third-generation sequencing. BMC plant biology 2025, 25, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Luan, G.; Chen, S.; Meng, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, N.; Suo, Y. Molecular Sex Identification in Dioecious Hippophae rhamnoides L. via RAPD and SCAR Markers. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ruan, C.J.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Liu, B.Q. Associations of SRAP markers with dried-shrink disease resistance in a germplasm collection of sea buckthorn (Hippophae L.). Genome 2010, 53, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Gallardo, J.J.; de Folter, S. Plant genome information facilitates plant functional genomics. Planta 2024, 259, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.; Bohra, A.; Mascher, M.; Spannagl, M.; Xu, X.; Bevan, M.W.; Bennetzen, J.L.; Varshney, R.K. Unlocking plant genetics with telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies. Nature genetics 2024, 56, 1788–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladman, N.; Goodwin, S.; Chougule, K.; Richard McCombie, W.; Ware, D. Era of gapless plant genomes: innovations in sequencing and mapping technologies revolutionize genomics and breeding. Current opinion in biotechnology 2023, 79, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakodi, M.; Shim, H.; Mascher, M. What Are We Learning from Plant Pangenomes? Annual review of plant biology 2025, 76, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medhi, U.; Chaliha, C.; Singh, A.; Nath, B.K.; Kalita, E. Third generation sequencing transforming plant genome research: Current trends and challenges. Gene 2025, 940, 149187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, A.A.; Pushkova, E.N.; Melnikova, N.V. [Plant Genome Sequencing: Modern Technologies and Novel Opportunities for Breeding]. Molekuliarnaia biologiia 2022, 56, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucker, B.; Irisarri, I.; de Vries, J.; Xu, B. Plant genome sequence assembly in the era of long reads: Progress, challenges and future directions. Quantitative plant biology 2022, 3, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shang, L.; Zhu, Q.H.; Fan, L.; Guo, L. Twenty years of plant genome sequencing: achievements and challenges. Trends in plant science 2022, 27, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Diao, S.; Zhang, G.; Yu, J.; Zhang, T.; Luo, H.; Duan, A.; Wang, J.; He, C.; Zhang, J. Genome sequence and population genomics provide insights into chromosomal evolution and phytochemical innovation of Hippophae rhamnoides. Plant biotechnology journal 2022, 20, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Pan, Y.; Feng, H.; Fang, D.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Sahu, S.K.; Liu, J.; et al. Genome of Hippophae rhamnoides provides insights into a conserved molecular mechanism in actinorhizal and rhizobial symbioses. The New phytologist 2022, 235, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Luo, S.; Yang, S.; Duoji, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Yang, D.; Yang, T.; Wan, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae rhamnoides variety. Scientific data 2024, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wu, B.; Jian, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Song, Z.; Zhang, W.; Qiong, L. How to survive in the world’s third poplar: Insights from the genome of the highest altitude woody plant, Hippophae tibetana (Elaeagnaceae). Frontiers in plant science 2022, 13, 1051587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Song, Y.; Chen, N.; Wei, J.; Zhang, J.; He, C. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae tibetana provides insights into high-altitude adaptation and flavonoid biosynthesis. BMC biology 2024, 22, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, D.; Yang, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, T.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Hippophae gyantsensis. Scientific data 2024, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zhang, G.Y.; Song, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.G.; He, C.Y. A chromosome-scale genome of Hippophae neurocarpa provides new insights into serotonin biosynthesis and chlorophyll-derived brown fruit coloration. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology 2025, 121, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Qu, H.; McKenzie, S.; Lawrence, K.R.; Windsor, R.; Vella, M.; Park, P.J.; Li, H. Efficient near telomere-to-telomere assembly of Nanopore Simplex reads. bioRxiv 2025, 2025.2004.2014.648685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liu, C.; Ji, W.; Xia, R.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Deng, X.W.; Li, B. Nanopore ultra-long sequencing and adaptive sampling spur plant complete telomere-to-telomere genome assembly. Molecular plant 2024, 17, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Li, H.; Jiang, M.; Hou, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Peng, K.; Liu, Y.X. Nanopore sequencing: flourishing in its teenage years. Journal of genetics and genomics = Yi chuan xue bao 2024, 51, 1361–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigova, E.A.; Dvorianinova, E.M.; Arkhipov, A.A.; Rozhmina, T.A.; Kudryavtseva, L.P.; Kaplun, A.M.; Bodrov, Y.V.; Pavlova, V.A.; Borkhert, E.V.; Zhernova, D.A.; et al. Nanopore Data-Driven T2T Genome Assemblies of Colletotrichum lini Strains. Journal of fungi 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchapov, N. Caryology of Hippophae rhamnoides L. 1979.

- ROUSI, A.; AROHONKA, T. C-bands and ploidy level of Hippophaë rhamnoides. Hereditas 1980, 92, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikova, N.V.; Arkhipov, A.A.; Zubarev, Y.A.; Novakovskiy, R.O.; Turba, A.A.; Pushkova, E.N.; Zhernova, D.A.; Mazina, A.S.; Dvorianinova, E.M.; Sigova, E.A.; et al. Genetic diversity of Hippophae rhamnoides varieties with different fruit characteristics based on whole-genome sequencing. Frontiers in plant science 2025, 16, 1542552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, C.; Veneruso, I.; De Simone, R.R.; Di Bonito, G.; Secondino, A.; D’Argenio, V. The Third-Generation Sequencing Challenge: Novel Insights for the Omic Sciences. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaushevska, M.; Alapont-Celaya, K.; Schack, A.K.; Krych, L.; Garrido Navas, M.C.; Krithara, A.; Madjarov, G. Get ready for short tandem repeats analysis using long reads-the challenges and the state of the art. Frontiers in genetics 2025, 16, 1610026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Pan, Z.; Nakagawa, T. Gross Chromosomal Rearrangement at Centromeres. Biomolecules 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naish, M. Bridging the gap: unravelling plant centromeres in the telomere-to-telomere era. The New phytologist 2024, 244, 2143–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Genome assembly in the telomere-to-telomere era. Nature reviews. Genetics 2024, 25, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Tan, K.; Huang, W.; Shi, J.; Li, T.; Hu, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Xin, B.; et al. A complete telomere-to-telomere assembly of the maize genome. Nature genetics 2023, 55, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ayhan, D.H.; Yi, S.; Yan, M.; Zhang, L.; Meng, T.; et al. Two telomere-to-telomere gapless genomes reveal insights into Capsicum evolution and capsaicinoid biosynthesis. Nature communications 2024, 15, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xu, S.; Ou, C.; Liu, X.; Zhuang, F.; Deng, X.W. T2T genomes of carrot and Alternaria dauci and their utility for understanding host-pathogen interactions during carrot leaf blight disease. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology 2024, 120, 1643–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Tan, J.; Huang, M.; Chu, X.; Li, Y.; Han, X.; Fang, T.; Tian, Y.; Jarret, R.; et al. Telomere-to-telomere Citrullus super-pangenome provides direction for watermelon breeding. Nature genetics 2024, 56, 1750–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xie, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H. The T2T genome assembly of soybean cultivar ZH13 and its epigenetic landscapes. Molecular plant 2023, 16, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Qin, H.; Hou, S.; Yang, X.; Jian, J.; Gao, P.; Liu, M.; Mu, Z. Telomere-to-telomere genome assembly of sorghum. Scientific data 2024, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Han, J.; Jin, S.; Han, Z.; Si, Z.; Yan, S.; Xuan, L.; Yu, G.; Guan, X.; Fang, L.; et al. Post-polyploidization centromere evolution in cotton. Nature genetics 2025, 57, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelenka, T.; Spilianakis, C. HiChIP and Hi-C Protocol Optimized for Primary Murine T Cells. Methods and protocols 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coster, W.; Rademakers, R. NanoPack2: population-scale evaluation of long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simao, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Molecular biology and evolution 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielbasa, S.M.; Wan, R.; Sato, K.; Horton, P.; Frith, M.C. Adaptive seeds tame genomic sequence comparison. Genome research 2011, 21, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.R.; Manuel Gonzalez de La Rosa, P.; Blaxter, M. tidk: a toolkit to rapidly identify telomeric repeats from genomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2025, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open2C; Abdennur, N.; Fudenberg, G.; Flyamer, I.M.; Galitsyna, A.A.; Goloborodko, A.; Imakaev, M.; Venev, S.V. Pairtools: from sequencing data to chromosome contacts. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.2002.2013.528389. [CrossRef]

- Durand, N.C.; Shamim, M.S.; Machol, I.; Rao, S.S.; Huntley, M.H.; Lander, E.S.; Aiden, E.L. Juicer Provides a One-Click System for Analyzing Loop-Resolution Hi-C Experiments. Cell systems 2016, 3, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcais, G.; Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranallo-Benavidez, T.R.; Jaron, K.S.; Schatz, M.C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M.; Hubley, R.; Goubert, C.; Rosen, J.; Clark, A.G.; Feschotte, C.; Smit, A.F. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117, 9451–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, L.; Bruna, T.; Hoff, K.J.; Ebel, M.; Lomsadze, A.; Borodovsky, M.; Stanke, M. BRAKER3: Fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome research 2024, 34, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsov, D.; Tegenfeldt, F.; Manni, M.; Seppey, M.; Berkeley, M.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. OrthoDB v11: annotation of orthologs in the widest sampling of organismal diversity. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D445–D451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).