1. Introduction

Repeating someone’s name aloud right after you’re introduced (e.g., “Nice to meet you, Alex!”) is a common social interaction strategy in some cultures, and it serves several overlapping purposes. First, it signals attention and respect, helping to establish rapport quickly. It also confirms that you heard the name correctly and provides a smooth transition into the conversation.

Saying the name aloud reinforces memory as well. Names are particularly easy to forget because they’re arbitrary and carry little inherent meaning but saying them aloud engages multiple contextual features at once—e.g., auditory stimulation, articulatory actions, and social bonds—making it far more likely that you’ll remember the person later. However, what might otherwise be considered a simple manifestation of a cultural or personal preference represents a fundamental cognitive phenomenon of language production and memory that has been scarcely investigated: the production effect.

1.1. The Production Effect: Definition and Experimental Evidence

Visually recognizing words stored in episodic memory—for example, recognizing at test time (t = 2) whether a word was visually presented at study time (t = 1)—is facilitated when the target word is encoded along with contextual features during the study phase. The cognitive psychology of memory, and especially associative cued-retrieval theories, refer to this phenomenon as the encoding specificity principle [

1,

2].

In the area of language and memory, higher accuracy in word recognition occurs when participants previously speak a word aloud rather than silently rehearse it. The language and memory literature refers to this phenomenon as the production effect [

3]. The production effect occurs not only in the context of spoken words but also in the context of written words [

4]. For example, partially typing a word during the study phase negatively affects the production effect at test time [

5]. However, the strength of the production effect differs across production modalities. Specifically, even when a word is entirely typed during the production phase, the production effect is weaker than when the word is entirely spoken, constituting a superior production effect of speaking over writing. From an evolutionary perspective, this superior effect likely reflects the earlier emergence of spoken language compared to the later emergence of written language [

6].

The distinctiveness account to memory encoding [

7,

8] applied to the production effect [

3,

9] indicates that, for example, the motoric act or the auditory perception of the spoken word (and analogously the tactile perception of key presses) represent distinct item-specific contextual features (CF) that the participant encodes along with the target item (I) at study time, constituting joint memory traces (CF, I). This implies that the probability of item recognition (IR) given (CF, I) at test time is greater than the probability of IR given the encoding of I only: p(IR | I, CF) > p(IR | I). Therefore, the distinctiveness account to the production effect positions the production effect as a special case of the encoding specificity principle.

1.2. Towards a Causal Explanation of the Production Effect

The production effect literature either implicitly or explicitly states a causal relationship between contextual features (CF) encoded at study time and item recognition (IR) at test time. For example, MacLeod, Gopie, Hourihan, Neary and MacLeod, Gopie, Hourihan, Neary and Ozubko [

3] and Forrin, MacLeod and Ozubko [

4] consistently use causal discourse markers [

10], such as “produces” and “enhances,” to refer to the production effect. Conforming to this causal discourse, research on the production effect has steadily moved from experimental interventions described through linear models (e.g., t tests, ANOVA, and regression) to explanatory computational models. The first steps in this direction have focused on extensions of models originally formulated within the global-matching framework of memory retrieval [

11], in which the encoding specificity principle is a special case.

The global-matching framework refers to a class of computational models of recognition memory that assume that a retrieval cue (e.g., a target word as a concrete I) is compared simultaneously to all stored memory traces and that recognition decisions depend on the aggregate (global) similarity between the cue and the entire memory system. In the special case of the production effect, producing a word aloud creates a memory trace with a greater number of contextual features (CF)—typically operationalized as increased noise-free features or higher encoding strength—compared to silently reading it. During recognition, the probe word (i.e., I) activates all stored traces, and items encoded aloud produce a larger and more salient match signal because their traces are more distinctive.

Drawing on the global-matching framework, the MINERVA 2 model [

12] and the REM model [

13] have been applied to explain the production effect [

14,

15]. In MINERVA 2, the activation of stored traces is implemented as a more salient and greater echo intensity due to the presence of more unique features in aloud-encoded traces, whereas in REM the aloud condition generates higher-probability feature matches and lower confusion probabilities in the likelihood ratio driving recognition decisions. Consequently, in both models, production-enhanced traces are more discriminable from lures, leading to higher recognition accuracy. These implementations show that the production effect can be modeled as a distinctiveness-driven increase in the mnemonic signal produced by aloud-encoded items within an associative global-matching architecture. While the global-matching framework has provided an explanatory account of the production effect, relevant computational models such as MINERVA and REM have four main limitations.

First, both schemes are predictive models of associative memory—mapping stimuli to responses—rather than generative causal models comprising latent causal variables (i.e., the unobservable cognitive processes that cause memory retrieval). More specifically, they contain assumptions about how memory traces correlate with each other, but they do not establish cause–effect relations in the way generative models do. It is worth noting, however, that their assumptions are congruent with the traditional notion of memory retrieval and recognition in the cognitive psychology literature [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Second, the application and interpretability of these models are limited to the memory domain rather than extending to general cognition and brain function.

Third, when applied to the production effect, both models focus only on response accuracy. Although most production-effect research has relied on response accuracy (e.g., proportion of correct probes) as the most important response variable of interest, a few experimental studies have recently incorporated recognition time (indexed by response time) as a secondary dependent measure. For example, recognition time is shorter in self-produced speaking conditions than when production is performed by another participant and faster when compared with silent study [

15]. As in any memory-related cognitive phenomenon, accuracy and response times are interdependent variables, and we cannot understand any generative cognitive process of behavior without considering the time these hypothetical processes take [

20]. Therefore, relevant computational models are more informative when they account for this interdependence (e.g., the drift diffusion model of memory retrieval) [

21].

A fourth limitation of these models refers to the fact that they simulate in silico the recognition effect of CF on I but are not applied to empirical data.

Based on the limitations of the global-matching models, a natural next step in the causal agenda of the production effect is to address the question of how CF relevant to the production modality (e.g., speaking and writing words) cause the retrieval of words in a recognition task. We attempt to answer this question experimentally and computationally within the context of perceptual (static) active inference and a Markov decision process (MDP).

1.3. The Current Work

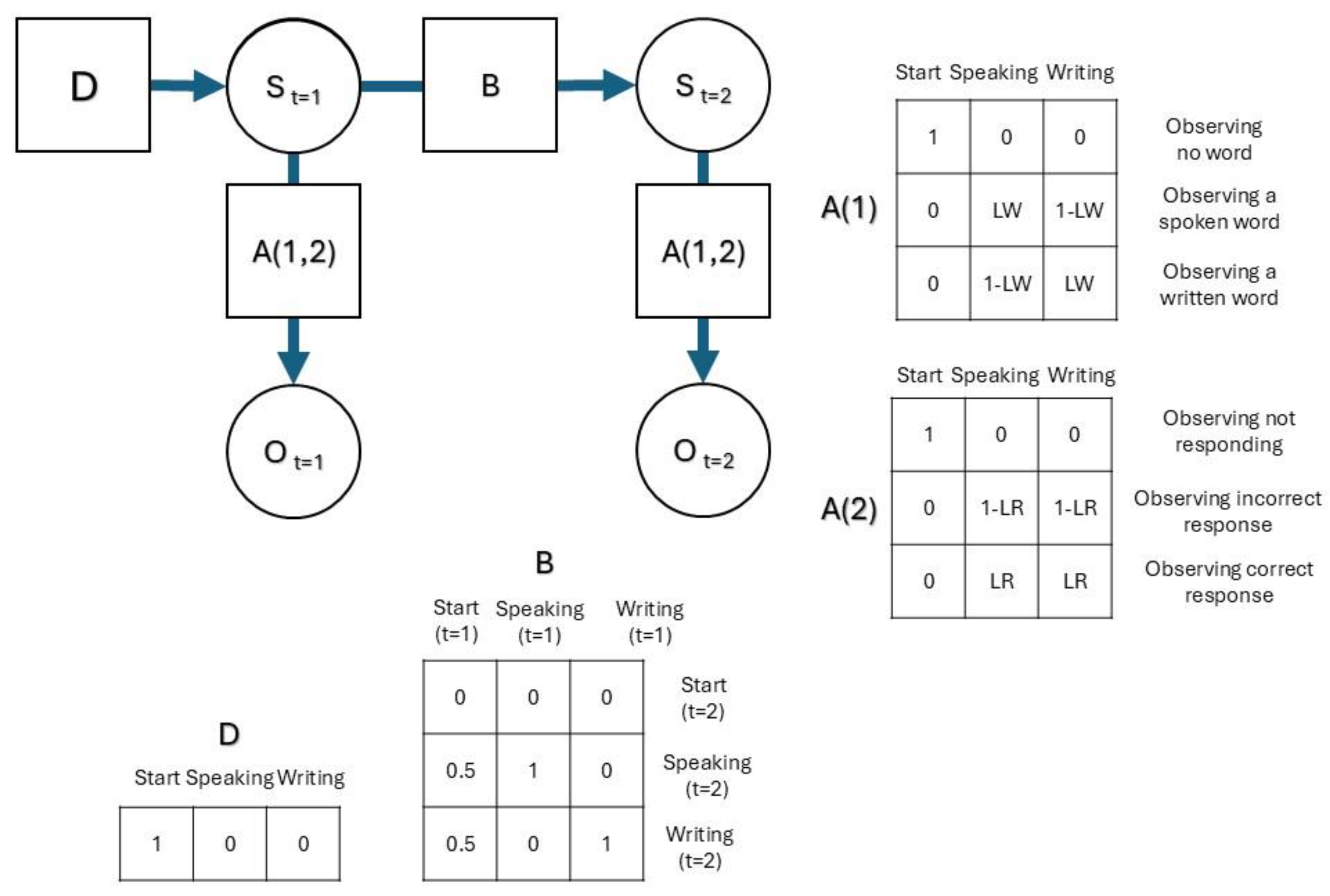

Within the framework of perceptual active inference (cf. predictive coding for perception) [

22,

23], formalized as a Markov decision process (MDP), we cast cue-dependent retrieval as inference over hidden states that encode contextual episodic features—here, whether a word was previously encoded in a spoken or written context—given the word as the sensory observation. Driven by the task instruction “respond whether you spoke or wrote the word,” the agent embodies a generative model of the causes of its sensory input. This generative model comprises hidden states corresponding to CF (i.e., speaking and writing production modalities) and outcome modalities encoding the observed visual words and the self-observation of responses at test time. Based on these observations, the agent updates its beliefs about the latent CF by inverting the generative model, selecting the CF state that minimizes variational free energy. From this perspective, what is treated as cue-dependent retrieval in the global-matching framework corresponds, in our causal generative model, to belief selection that maximizes model evidence by favoring the spoken or written CF state whose predicted sensory consequences best account for the observed word and the self-observed response. This formulation thus provides an active-inference realization of the encoding specificity principle in terms of state estimation under an MDP.

The current work builds on previous findings showing that recognition accuracy is higher for spoken than for written words [

4,

6]. Extending these results, we incorporate within a single model a parameter capturing the hypothesis that the stronger production effect observed in the spoken modality is also associated with shorter response times (RTs). We reiterate that influential cognitive models of memory recognition such as the drift diffusion model [

21] account for both accuracy and response times within a unified framework, reflecting their interdependence (e.g., the speed–accuracy trade-off). Accordingly, we test the hypothesis that RTs are shorter when recognizing words encoded in the spoken CF than in the written CF. In essence, by specifying a single perceptual model, we simultaneously test the novel hypothesis that recognition is faster in the speaking condition than in the writing condition and that a causal generative model provides a better explanation of the data than simple statistical linear models.

5. Discussion

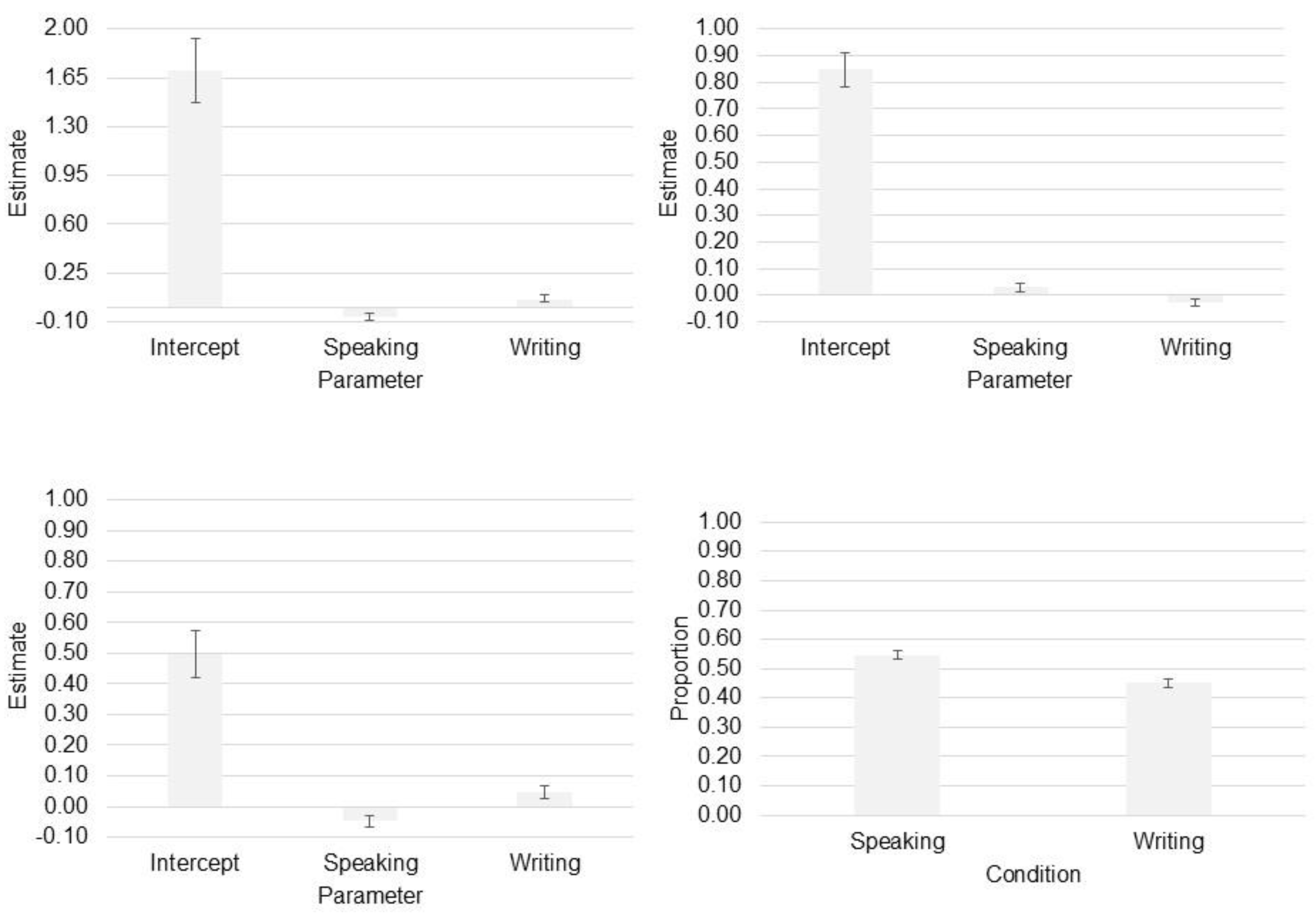

We put forward the idea that the MDP embodies the theoretical construct that production modality is a hidden cause of word memory retrieval. The superior model evidence for the MDP, relative to a simple statistical description model, provides computational support for the construct validity of this hidden-state formulation. The reported MDP model also provides evidence that speaking words aloud reduces word retrieval time compared to typing words. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to explain the production effect using computational models specified within the active inference framework, albeit at the level of static perception or predictive coding.

Within the field of computational models of cognition, many authors argue that such models provide a deeper understanding of cognitive phenomena than descriptions based solely on statistical models [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. However, direct comparisons between computational models and statistical models remain scarce. Crucially, this study provides the first direct model comparison of the production effect and, to our knowledge, the first comparison between linear models estimated using VL and MDP evaluated via Bayesian model selection.

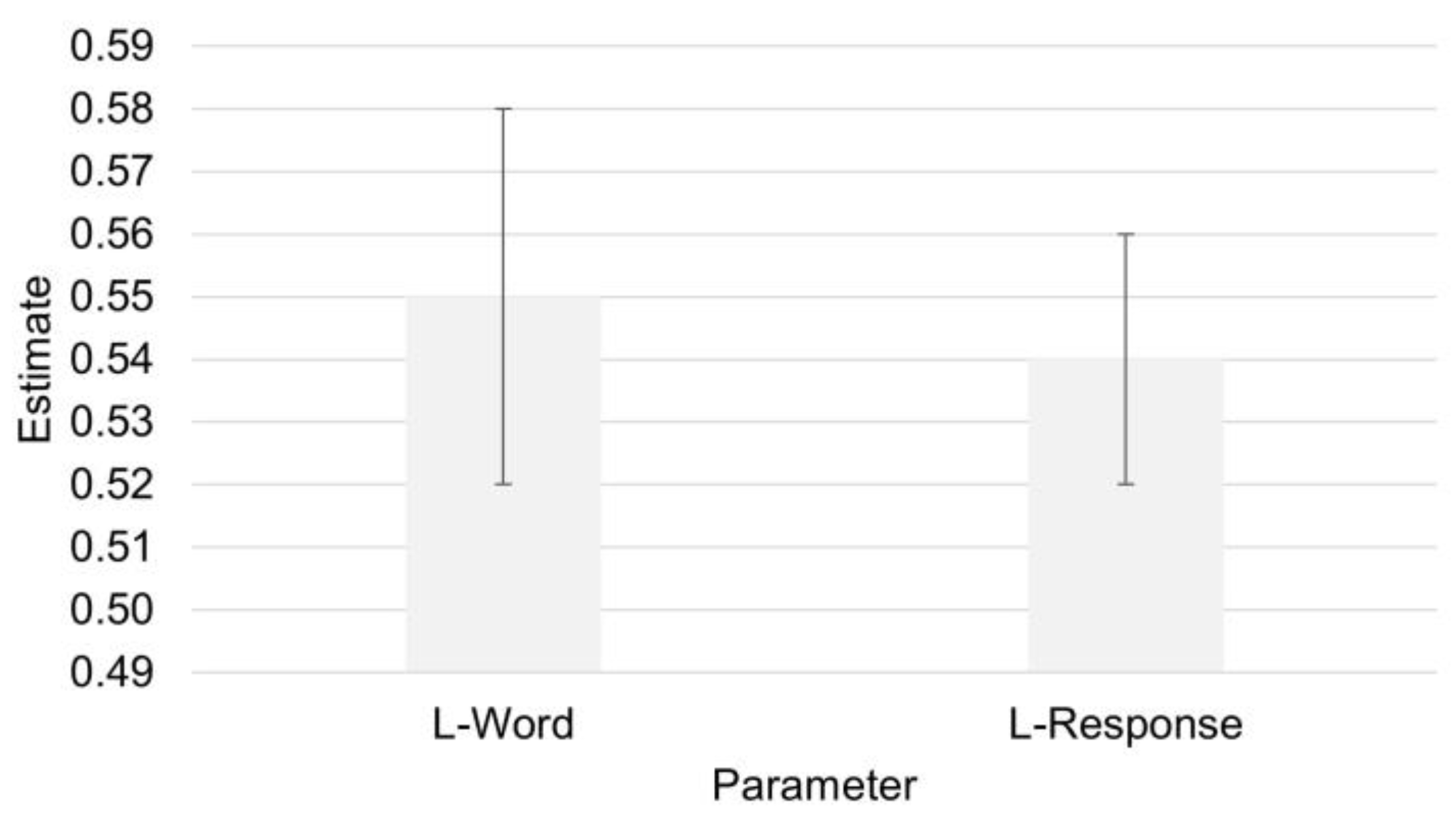

Crucially, the MDP model confirms the reliability paradox of statistical models, whereby consistent group effects [….] do not accurately reflect individual differences [

33]. The 95% credible intervals for both the L-Word and L-Response parameters indicate that the group-level parameters exceed p = 0.5. Although the effect sizes appear small when expressed in terms of probabilities, they correspond to moderate-to-large and large effects in standardized terms. For context, consider the equivalent frequentist null-hypothesis tests at the group level: for L-Word, t(15) = 4.1, p < 0.001, CI [0.02, 0.06]; and for L-Response, t(15) = 2.8, p = 0.012, CI [0.012, 0.081]. The corresponding Cohen’s d values are 0.71 for the L-Word parameter (medium-to-large effect size) and 1.03 for the L-Response parameter (large effect size). The robust group-level effect sizes do not mask individual variability. Specifically, we identified two participants who showed higher precision in the writing contextual state and one participant who showed higher precision in the self-observation of incorrect responses (

Table 2). These individual differences raise at least two questions regarding the production effect.

First, differences in the L-Response parameter indicate inter-individual variability in the precision of self-monitoring of response outcomes. Most participants showed relatively reliable inference about their own performance, whereas two participants exhibited noisier self-evaluation. Such results provide a basis for characterizing individual cognitive phenotypes. One possible interpretation is that these participants are more prone to detecting their errors than their successes during language production, a distinction that, as elaborated upon below, is particularly relevant in the context of language learning.

In the second language acquisition (SLA) literature, learners differ systematically in their sensitivity to negative evidence, with some individuals exhibiting an error-oriented self-monitoring style in which deviations from target forms are more salient than successful productions. This phenomenon has been discussed under labels such as heightened responsiveness to negative evidence, over-monitoring, and differential noticing of errors, particularly in research on focus on form and feedback processing [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

From the perspective of static perception or predictive coding, however, such individual differences do not need to be framed as strategic choices or motivational dispositions, but can instead be understood as differences in the precision-weighting of self-generated prediction errors during perceptual inference [

41,

42]. In a perceptual Markov decision process, self-evaluative outcomes—such as perceived correctness or incorrectness of a response—are treated as observations generated by latent performance states. Learners who are more error-oriented can thus be modeled as assigning higher precision to error-related self-observations, such that prediction errors signaling incorrect performance exert a stronger influence on posterior beliefs than signals of success. Conversely, learners who are less focused on errors effectively down-weight these prediction errors, treating them as noisier or less informative. This computational account reframes SLA notions of error orientation and sensitivity to negative evidence not as a bias toward negative outcomes per se, but as principled differences in perceptual precision within a Bayesian generative model, thereby providing a mechanistic explanation for individual differences in self-monitoring during second language learning.

Second, most participants were more likely to infer the production modality of spoken words than that of written words, as indicated by the group-level L-Word parameter, leading to faster recognition times. Why, then, did participants take longer to recognize written words? As noted in the Introduction, evolutionary and cultural factors may help explain the superior production effect of spoken words, for which fast and brief utterances are common. Written language, by contrast, was not culturally developed to facilitate rapid communication. Writing is inherently time-consuming because it is closely tied to the exploration and generation of knowledge. In other words, spoken language tends to be less elaborate and typically shorter in informational content and lexical density than written texts such as textbooks and academic prose [

43].

Furthermore, although retrieving individual words is a prerequisite for language production, it is not necessarily indicative of knowledge generation, which is a core function of written language. Writing is therefore a slower process, a property that is congruent with active inference accounts emphasizing exploratory behavior. A natural follow-up question is whether producing more complex registers (e.g., sentences combining multiple words) in spoken language confers advantages over writing [

44] in memory retrieval of individual words. That is, language users may be more accustomed to producing written registers to communicate extended bodies of knowledge or to generate new knowledge. While this explanation offers a computational perspective on evolutionary and cultural differences across language modalities, it also opens the possibility that slower recognition times in the writing condition constitute a computational advantage from the perspective of the exploration–exploitation dilemma. In this view, the few participants who showed faster recognition times in the writing modality may have resolved this dilemma in line with their individual preferences. This point highlights one of several limitations of the current model and experimental task, which speaks to future improvements.

First, as a static perceptual model, it does not exploit the full computational and theoretical capabilities of the active inference framework, particularly the possibility of a speaking–writing trade-off between exploration and exploitation. Addressing this trade-off would require introducing a third timestep in the model, in which participants could choose not to respond at t = 2 and respond at t = 3 (corresponding to late responses), or respond at t = 2 (corresponding to early responses). Incorporating these possible actions would also require specifying at least two shallow policies (i.e., wait and respond). Future work should explore this extended active inference scheme.

Second, we discretized response times (RTs). However, the memory research literature has long emphasized the value of analyzing the full RT distribution. This is feasible within the active inference framework. Future work could, for example, directly compare a model using discretized RTs with a continuous-state model.

Third, the present study compared a perceptual model with a linear model, demonstrating a better account of the data and stronger causal construct validity. However, this model should also be directly compared with established memory models of the production effect (e.g., MINERVA and REM).

Finally, from an experimental task design perspective, this study focused on a specific hypothesis concerning the superior production effect of speaking over writing (i.e., a relative production effect). However, it did not address the absolute production effect of either modality by including a control condition (e.g., silently reading words).

Conclusions

While previous research has provided experimental evidence for the production effect and initial computational accounts of its dynamics, the present work advances the understanding of this language and memory phenomenon by proposing a generative model of the causes underlying faster retrieval times for spoken compared with written words. The study also provides direct evidence for the superior explanatory power of active inference models relative to simpler statistical models. Notably, this comparison represents the first use of a linear model estimated under the VL scheme for this purpose. Importantly, the proposed model simultaneously identifies group-level parameters that capture the general dynamics of the production effect and reveals individual differences in parameter estimates, with potential implications for language learning and knowledge generation through writing.