Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

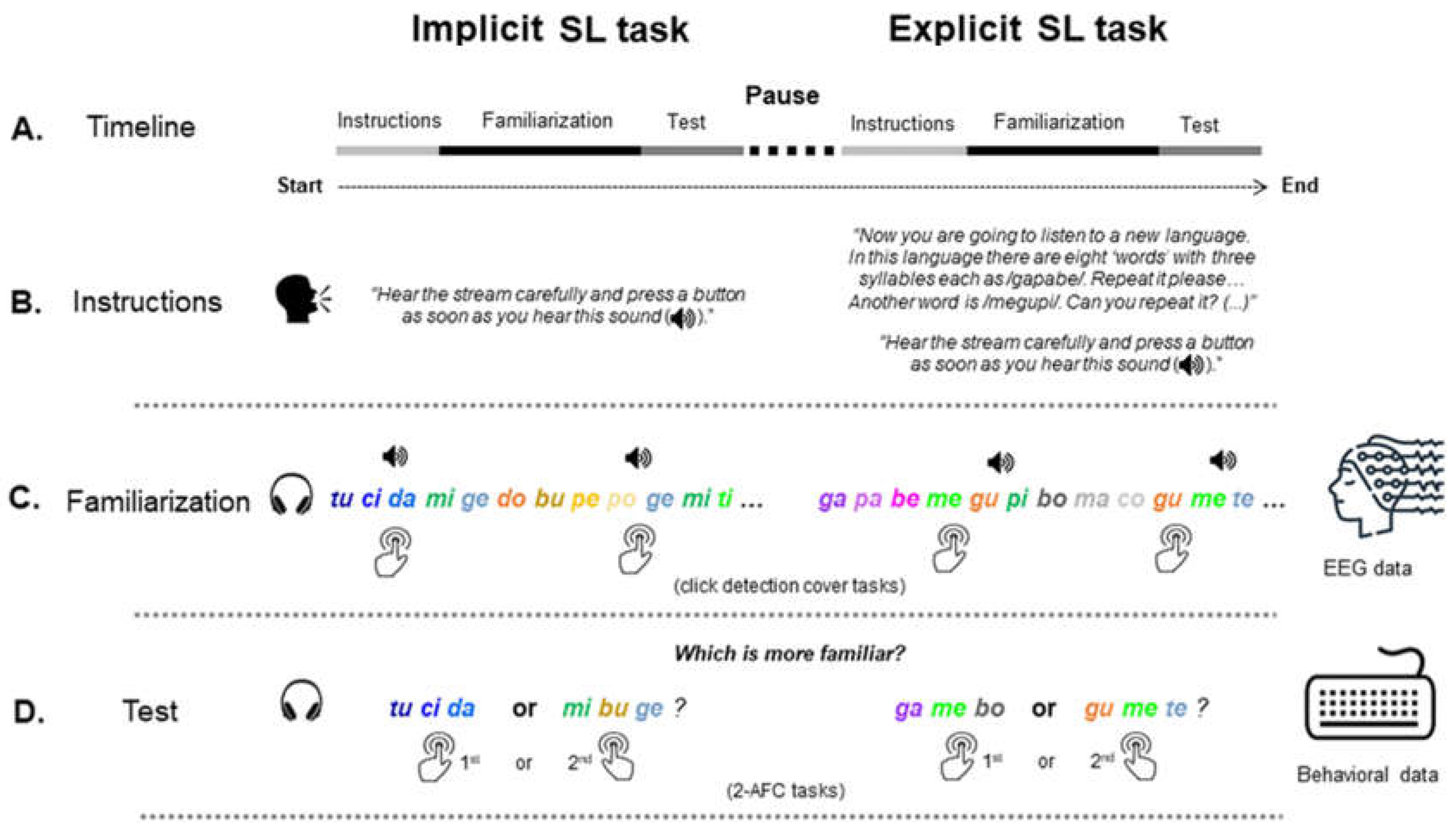

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli

2.3. Procedure

2.4. EEG Data Acquisition and Processing

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Data

3.2. Electrophysiological Data

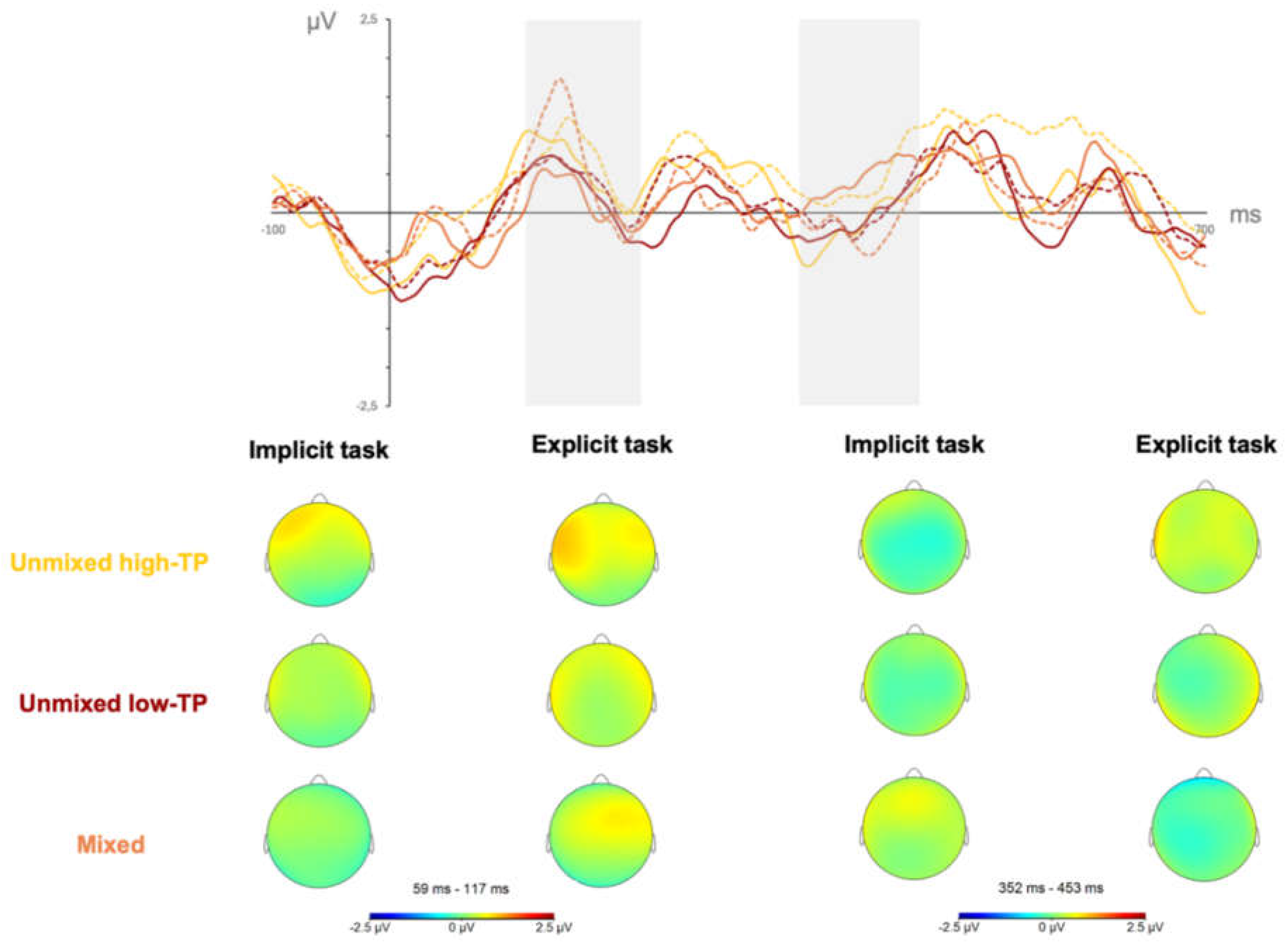

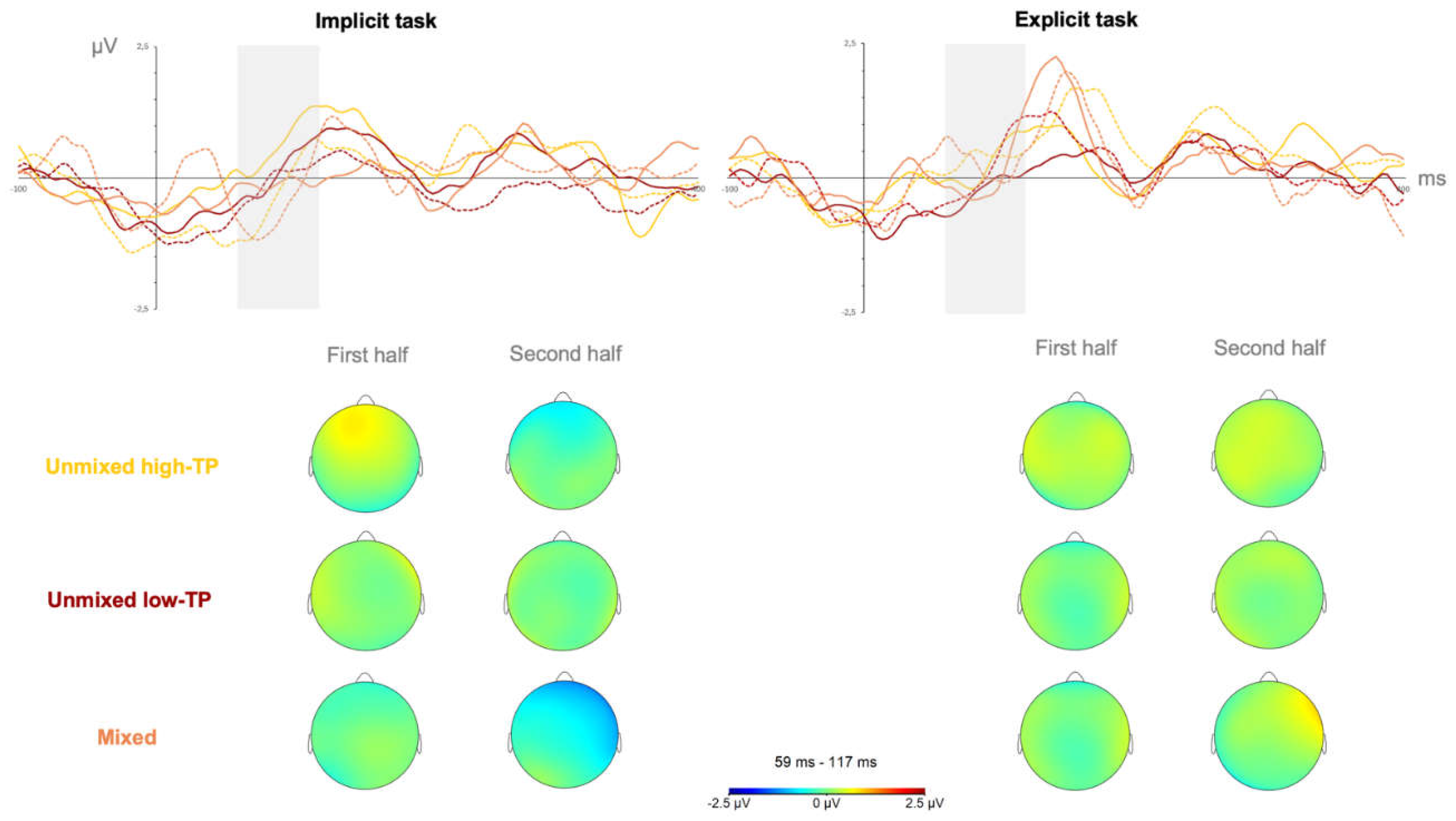

3.2.1. N100

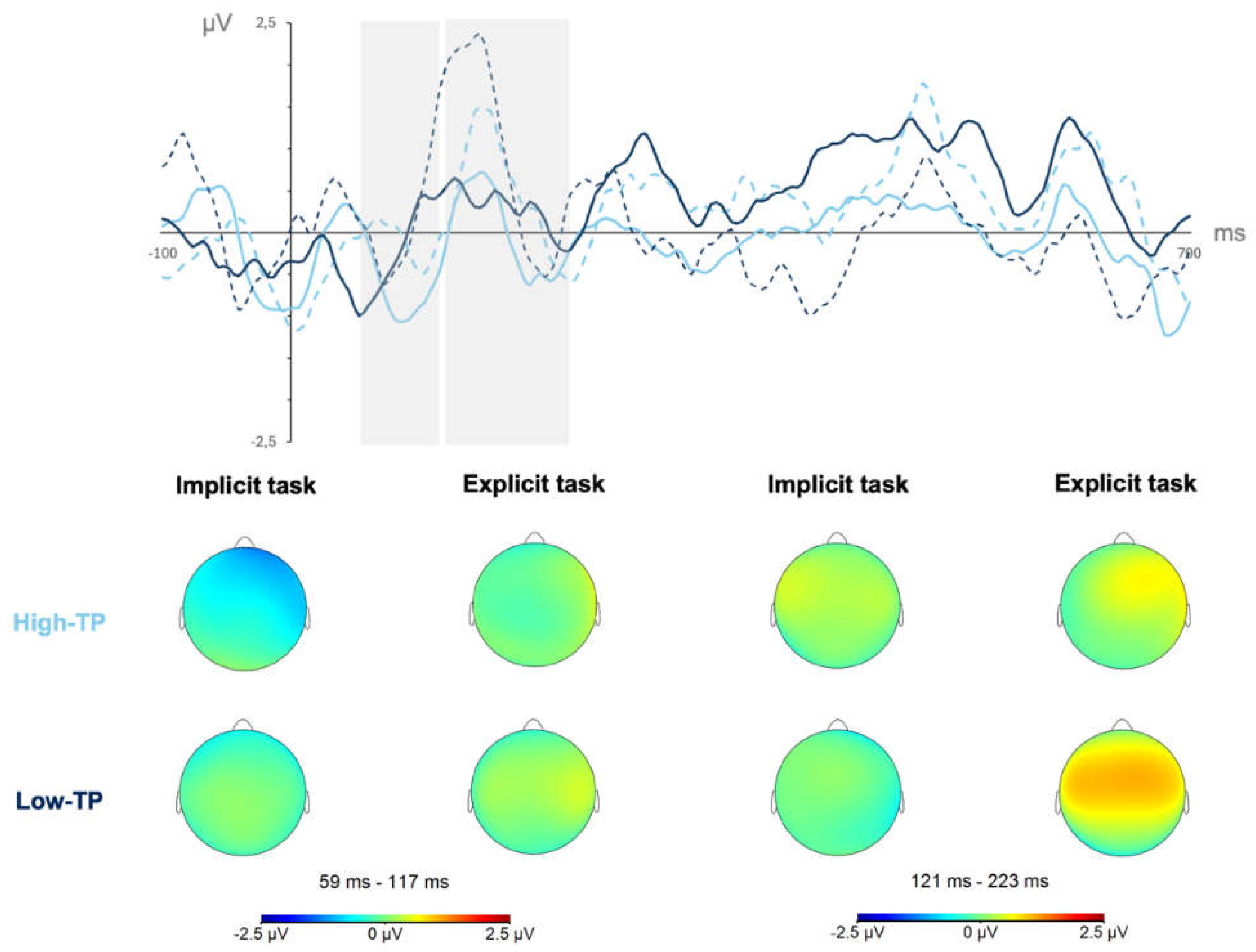

3.2.2. P200

3.2.3. N400

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saffran, J.R.; Aslin, R.N.; Newport, E.L. Statistical learning by 8-month-old infants. Science 1996, 274, 1926–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, E.; Pomper, R.; Saffran, J. Phonological learning influences label-object mapping in toddlers. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2019, 62, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, K.G.; Evans, J.L.; Alibali, M.W.; Saffran, J.R. Can infants map meaning to newly segmented words? Statistical segmentation and word learning. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, J.F.; Pelucchi, B.; Estes, K.G.; Saffran, J.R. Linking sounds to meanings: Infant statistical learning in a natural language. Cogn. Psychol. 2011, 63, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, T.H. Frequent frames as a cue for grammatical categories in child directed speech. Cognition 2003, 90, 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, P.; Christiansen, M.H.; Chater, N. The phonological-distributional coherence hypothesis: Cross-linguistic evidence in language acquisition. Cogn. Psychol. 2007, 55, 259–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, R.; Maye, J. The developmental trajectory of nonadjacent dependency learning. Infancy 2005, 7, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.; Tomblin, J.; Christiansen, M. Impaired statistical learning of non-adjacent dependencies in adolescents with specific language impairment. Front. Psychol. 2004, 5, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, E. Implicit statistical learning is directly associated with the acquisition of syntax. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newport, E.L.; Aslin, R.N. Learning at a distance I. Statistical learning of non-adjacent dependencies. Cogn. Psychol. 2004, 48, 127–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arciuli, J.; Simpson, I.C. Statistical learning is related to reading ability in children and adults. Cogn. Sci. 2012, 36, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lages, A.; Oliveira, H.M.; Arantes, J.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.J.; Soares, A.P. Drawing the links between statistical learning and children’s spoken and written language skills. In International Handbook of Clinical Psychology, 1st ed; Buela-Casal, G., Ed.; Thomson Reuters Editorial, 2022. ISBN: 978-84-1390-874-8.

- Sawi, O.M.; Rueckl, J. Reading and the neurocognitive bases of statistical learning. Sci. Stud. Read. 2019, 23, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Kaschak, M.P.; Jones, J.L.; Lonigan, C.J. Statistical learning is related to early literacy-related skills. Read. Writ. 2015, 28, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegelman, N. Statistical learning abilities and their relation to language. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2020, 14, e12365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.K. Bootstrapping language: Are infant statisticians up to the job? In Statistical learning and language acquisition; Rebuschat, P., Williams, J., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyter, 2012, pp. 55–89. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.D. Universal grammar, statistics or both? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004, 8, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterink, L.J.; Paller, K.A. Online neural monitoring of statistical learning. Cortex 2017, 90, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterink, L.J.; Reber, P.J.; Paller, K.A. Functional differences between statistical learning with and without explicit training. Learn. Mem. 2015, 22, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterink, L.; Reber, P.J.; Neville, H.; Paller, K.A. Implicit and explicit contributions to statistical learning. J. Mem. Lang. 2005, 83, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunillera, T.; Càmara, E.; Toro, J.M.; Marco-Pallares, J.; Sebastián-Galles, N.; Ortiz, H. Time course and functional neuroanatomy of speech segmentation in adults. Neuroimage 2009, 48, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, L.D.; Ameral, V.; Sayles, K. Event-related potentials index segmentation of nonsense sounds. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 1183–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.P.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.; Vasconcelos, M.; Oliveira, H.M.; Tomé, D.; Jiménez, L. Not all words are equally acquired: Transitional probabilities and instructions affect the electrophysiological correlates of statistical learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 577991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipf, G. The Psychobiology of Language; Routledge: London, England, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi, S.T. Zipf’s word frequency law in natural language: A critical review and future directions. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2014, 21, 1112–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.P.; Iriarte, A.; Almeida, J.J.; Simões, A.; Costa, A.; França, P.; Machado, J.; Comesaña, M. Procura-PALavras (P-PAL): Uma nova medida de frequência lexical do português europeu contemporâneo. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2014, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.P.; Lages, A.; Silva, A.; Comesaña, M.; Sousa, I.; Pinheiro, A.P.; Perea, M. Psycholinguistics variables in the visual-word recognition and pronunciation of European Portuguese words: A megastudy approach. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 34, 689–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.D.; Oliveira, H.M.; Soares, A.P. The role of syllables in intermediate-depth stress-timed languages: Masked priming evidence in European Portuguese. Read. Writ. 2018, 31, 1209–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, E.D.; Kronstein, A.T.; Hufnagle, D.G. The extraction and integration framework: A two-process account of statistical learning. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 792–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasson, U. The neurobiology of uncertainty: implications for statistical learning. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2017, 372, 20160048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stärk, K.; Kidd, E.; Frost, R.L. The effect of children’s prior knowledge and language abilities on their statistical learning. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2022, 43, 1045–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegelman, N.; Bogaerts, L.; Elazar, A.; Arciuli, J.; Frost, R. Linguistic entrenchment: Prior knowledge impacts statistical learning performance. Cognition 2018, 177, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunillera, T.; Laine, M.; Càmara, E.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A. Bridging the gap between speech segmentation and word-to-world mappings: Evidence from an audiovisual statistical learning task. J. Mem. Lang. 2010, 63, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, L.; Siegelman, N.; Frost, R. Splitting the variance of statistical learning performance: a parametric investigation of exposure duration and transitional probabilities. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 23, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.J.; Lages, A.; Oliveira, H.M.; Soares, A.P. Neural signature of statistical learning: Proposed signs of typical/atypical language functioning from EEG time-frequency analysis. In International Handbook of Clinical Psychology, 1st ed; Buela-Casal, G., Ed.; Thomson Reuters Editorial, 2022. ISBN: 978-84-1390-874-8.

- Lavi-Rotbain, O.; Arnon, I. The learnability consequences of Zipfian distributions in language. Cognition 2022, 223, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegelman, N.; Bogaerts, L.; Frost, R. Measuring individual differences in statistical learning: current pitfalls and possible solutions. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, L.; Siegelman, N.; Christiansen, M.H.; Frost, R. Is there such a thing as a ‘good statistical learner’? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.P.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.J.; Lages, A.; Oliveira, H.M.; Vasconcelos, M.; Jiménez, L. Learning Words While Listening to Syllables: Electrophysiological Correlates of Statistical Learning in Children and Adults. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 805723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.P.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.; Oliveira, H.M.; Lages, A.; Guerra, N.; Pereira, A.R.; Tomé, D.; Lousada, M. Explicit instructions do not enhance auditory statistical learning in children with developmental language disorder: Evidence from ERPs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 905762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.P.; Lages, A.; Oliveira, H.M.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.J. Extracting word-like units when two concurrent regularities collide: Electrophysiological evidence. In Proceedings of 12th International Conference of Experimental Linguistics, Athens, Greece, 11-13 October, 2021; Botinis, A., Ed.; ExLing Society, Athens, Greence, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.P.; Lages, A.; Oliveira, H.M.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.J. Can explicit instructions enhance auditory statistical learning in children with Developmental Language Disorder? In International Handbook of Clinical Psychology, 1st ed; Buela-Casal, G., Ed.; Thomson Reuters Editorial, 2022. ISBN: 978-84-1390-874-8.

- Bishop, D.V.M.; Snowling, M.J.; Thompson, P.A.; Greenhalgh, T. ; The CATALISE Consortium Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.P.; Lousada, M.; Ramalho, M. Perturbação do desenvolvimento da linguagem: Terminologia, caracterização e implicações para os processos de alfabetização [Language development disorder: Terminology, characterization and implications for literacy]. In Alfabetização Baseada na Ciência; Alves, R.A., Leite, I., Eds; CAPES, 2021, pp. 441–471, ISBN: 978-65-87026-86-2.

- Soares, A.P.; França, T.; Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F.; Sousa, I. & Oliveira, H.M. As trials goes by: Effects of 2-AFC item repetition on SL performance for high- and low-TP ‘Words’ under implicit and explicit conditions. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 2022, 77, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abla, D.; Katahira, K.; Okanoya, K. On-line assessment of statistical learning by event-related potentials. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2008, 20, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukács, Á.; Lukics, K.S.; Dobó, D. Online Statistical Learning in Developmental Language Disorder. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 715818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, L.; Arnon, I. The developmental trajectory of children’s auditory and visual statistical learning abilities: modality-based differences in the effect of age. Dev. Sci. 2018, 21, e12593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Witteloostuijn, M.; Lammertink, I.; Boersma, P.; Wijnen, F.; Rispens, J. Assessing visual statistical learning in early-school-aged children: The usefulness of an online reaction time measure. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.P.; Silva, R.; Faria, F.; Mendes, H.O.; Jiménez, L. Literacy effects on artificial grammar learning (AGL) with letters and colors: Evidence from preschool and primary school children. Lang. Cogn. 2021, 13, 534–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daikoku, T.; Yatomi, Y.; Yumoto, M. Statistical learning of an auditory sequence and reorganization of acquired knowledge: A time course of word segmentation and ordering. Neuropsychologia 2017, 95, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegelman, N.; Bogaerts, L.; Frost, R. What Determines Visual Statistical Learning Performance? Insights From Information Theory. Cogn. Sci. 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. Claude Shannon. Information Theory 1948, 3, 224. [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku, T.; Yumoto, M. Order of statistical learning depends on perceptive uncertainty. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 2023, 4, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslin, R.N.; Newport, E.L. Statistical learning: From acquiring specific items to forming general rules. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubit, L.S.; Canale, R.; Handsman, R.; Kidd, C.; Bennetto, L. Visual Attention Preference for Intermediate Predictability in Young Children. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiser, J.; Aslin, R.N. Statistical learning of higher-order temporal structure from visual shape sequences. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2002, 28, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, C.; Piantadosi, S.T.; Aslin, R.N. The Goldilocks Effect: Human Infants Allocate Attention to Visual Sequences That Are Neither Too Simple Nor Too Complex. PloS ONE 2012, 7, e36399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegelman, N.; Bogaerts, L.; Frost, R. Measuring individual differences in statistical learning: Current pitfalls and possible solutions. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, S.; Kidd, C. The role of prior knowledge and curiosity in learning. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2019 26, 1377–1387. [CrossRef]

- Heinks-Maldonado, T.H.; Mathalon, D.H.; Gray, M.; Ford, J.M. Fine-tuning of auditory cortex during speech production. Psychophysiology 2005, 42, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegelman, N.; Bogaerts, L.; Christiansen, M.H.; Frost, R. Towards a theory of individual differences in statistical learning. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2017, 372, 20160059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldfield, R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espirito-Santo, H.; Pires, C.F.; Garcia, I.Q.; Daniel, F.; Silva, A.G.D.; Fazio, R.L. Preliminary validation of the Portuguese Edinburgh Handedness Inventory in an adult sample. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2017, 24, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Diego Balaguer, R.; Toro, J.M.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A.; Bachoud-Lévi, A. Different neurophysiological mechanisms underlying word and rule extraction from speech. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunillera, T.; Toro, J.M.; Sebastián-Gallés, N.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A. The effects of stress and statistical cues on continuous speech segmentation: an event-related brain potential study. Brain Res. 2006, 1123, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, C.; Teixidó, M.; Takerkart, S.; Agut, T.; Bosch, L.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A. Enhanced Neonatal Brain Responses To Sung Streams Predict Vocabulary Outcomes By Age 18 Months. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, L.J.; Tague, E.C.; Nelson III, C.A. Maternal stress predicts neural responses during auditory statistical learning in 26-month-old children: an event-related potential study. Cognition 2021, 213, 104600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakin, D.K.; Smith, R. Retroactive interference effects in implicit memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2012, 38, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, L.; Vaquero, J.M.M.; Lupiáñez, J. Qualitative differences between implicit and explicit sequence learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2006, 32, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustig, C.; Hasher, L. Implicit memory is not immune to interference. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero, J.M.M.; Lupianez, J.; Jiménez, L. Asymmetrical effects of control on the expression of implicit sequence learning. Psychol. Res. 2019, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Syllabary A | Syllabary B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of stream | “Words” | Foils | “Words” | Foils |

| unmixed high-TP | tucida | tubago | todidu | tomabe |

| bupepo | bucica | cegita | cedico | |

| modego | mopeda | gapabe | gagidu | |

| bibaca | bidepo | bomaco | bopata | |

| unmixed low-TP | dotige | dogeti | pitegu | pigute |

| tidomi | timido | tepime | temepi | |

| migedo | midoge | megupi | mepigu | |

| gemiti | getimi | gumete | guteme | |

| mixed A | migedo | gebado | megupi | gumapi |

| gemiti | mogeti | gumete | gagute | |

| modego | bimigo | gapabe | bomebe | |

| bibaca | mideca | bomaco | mepaco | |

| mixed B | dotige | docimi | pitegu | tegigu |

| tidomi | budoge | tepime | toteme | |

| tucida | tutipo | todidu | cepidu | |

| bupepo | tipeda | cegita | pidita | |

| SL Task | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of stream | Implicit | Explicit |

| Unmixed high-TP | 61.3 (11.5) | 71.5 (12.3) |

| Unmixed low-TP | 55.9 (8.7) | 64.1 (13.4) |

| Mixed | 62.2 (15.1) | 69.6 (17.4) |

| SL Task | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of word | Implicit | Explicit |

| High-TP | 65.8 (23.0) | 75.0 (21.7) |

| Low-TP | 58.7 (18.6) | 64.1 (19.0) |

| 1 | The studies conducted with children ([39-42]) showed that performance was not significantly different from chance, which was in line with other studies indicating that the 2-AFC task is not suited for children below six years of age (e.g., [47,48,49] - see also [50] for similar findings in the context of the artificial grammar learning [AGL] task). |

| 2 | These values were obtained through the computation of the Markov’s entropy formula, i=1np(i)j=1npi*logp(j|i) taking TPs for all possible transitions (syllable pairs) in each of the streams into account. This formula sums, for each transition (i, j), the product of the distributional probability of i [p(i)], with the conditional probability of i|j [p(j|i)], and its logarithm [logp(j|i )]. Both a higher number of triplets and lower TPs increase entropy. A higher number of triplets increases entropy through the decrease of predictability in “word” boundaries since each “word” can be followed by n-1 “words”, or n-2 for low-TP “words”. Lower TPs increase the level of “surprisal” for the syllable transition. This concept proves useful for better detailing the predictability of a set of stimuli in a stream, giving us a more complete and unified assessment of predictability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).