Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

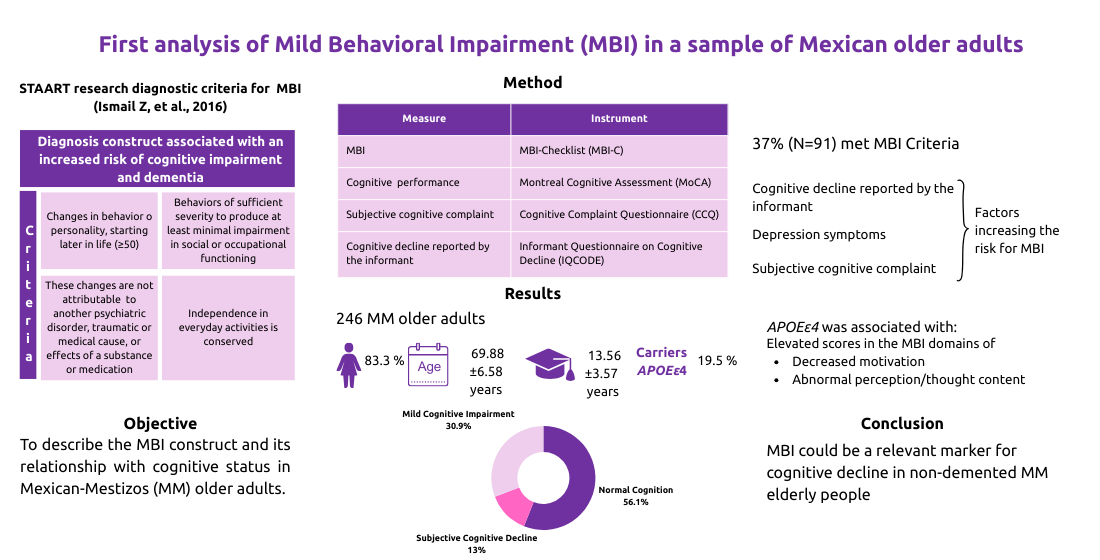

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

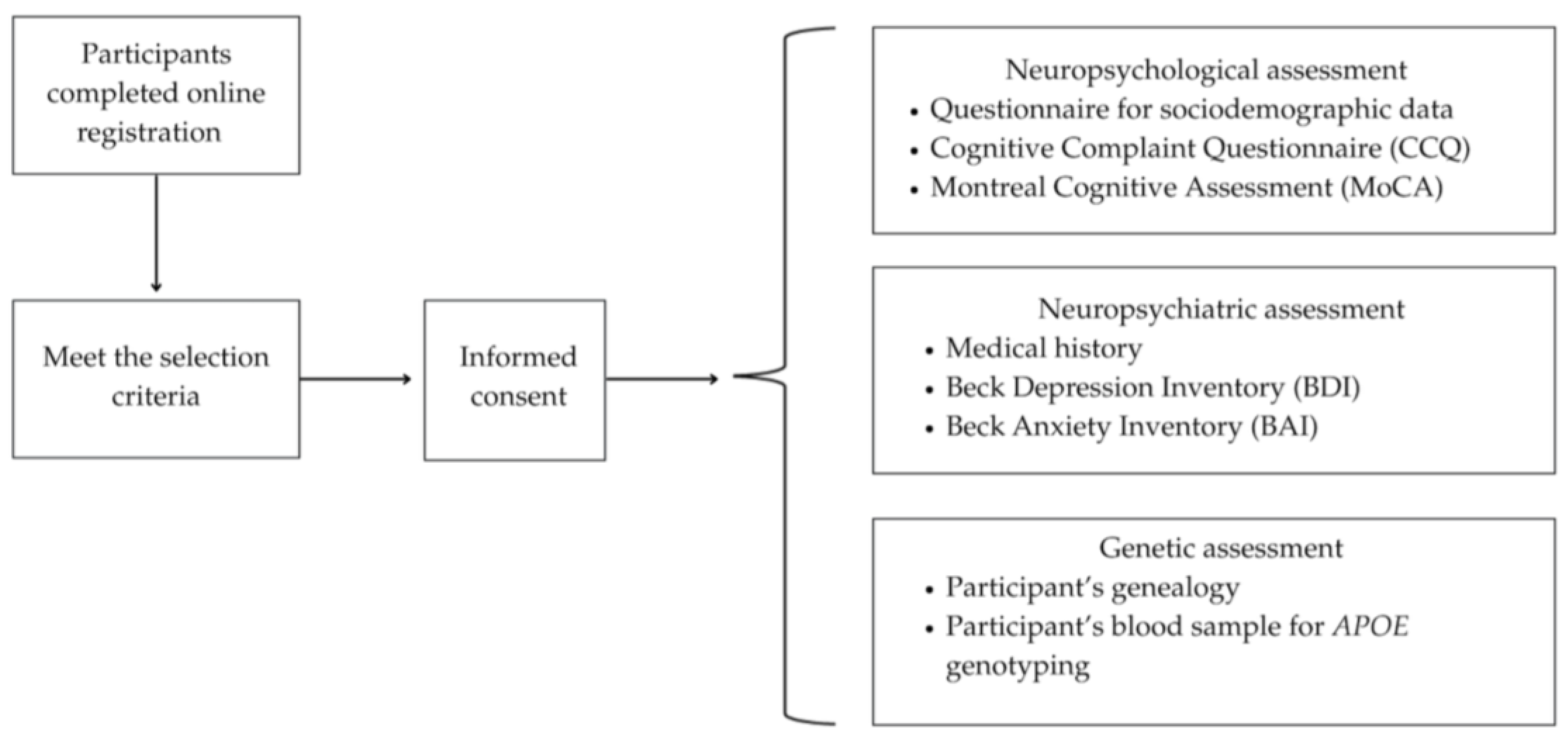

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments

2.1. Classification of Cognitive Status

2.2. Genetic Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic, Cognitive, Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. MBI Characteristics and its Frequency in the Cohort

3.3. Sociodemographic, Clinical Characteristics and APOEε4 Status Between Participants With and Without MBI

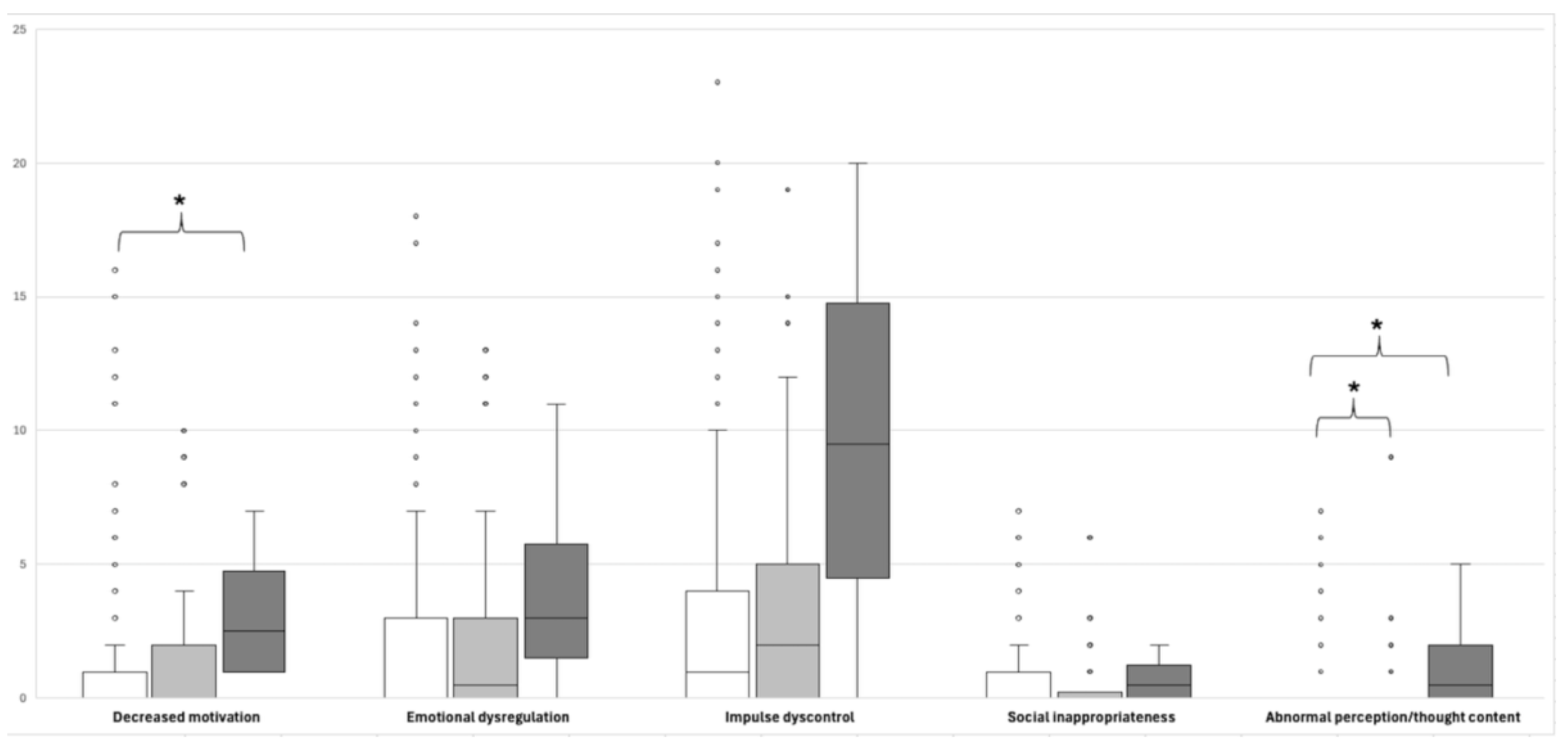

3.4. Comparison of MBI-C Domain Scores According to the Participants’ APOEε4 Carrier Status

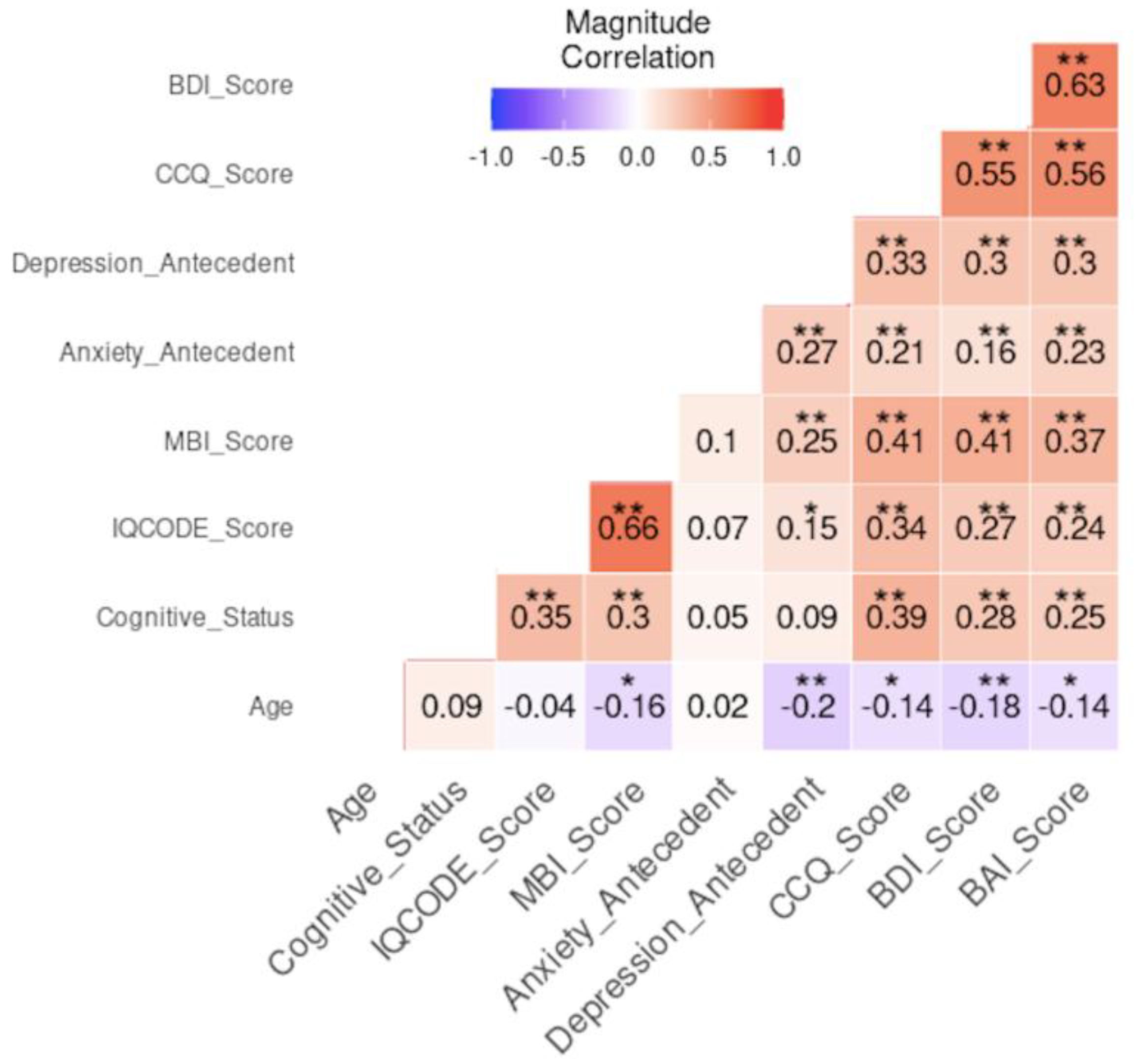

3.5. Risk Association and Multivariate Correlation Analysis

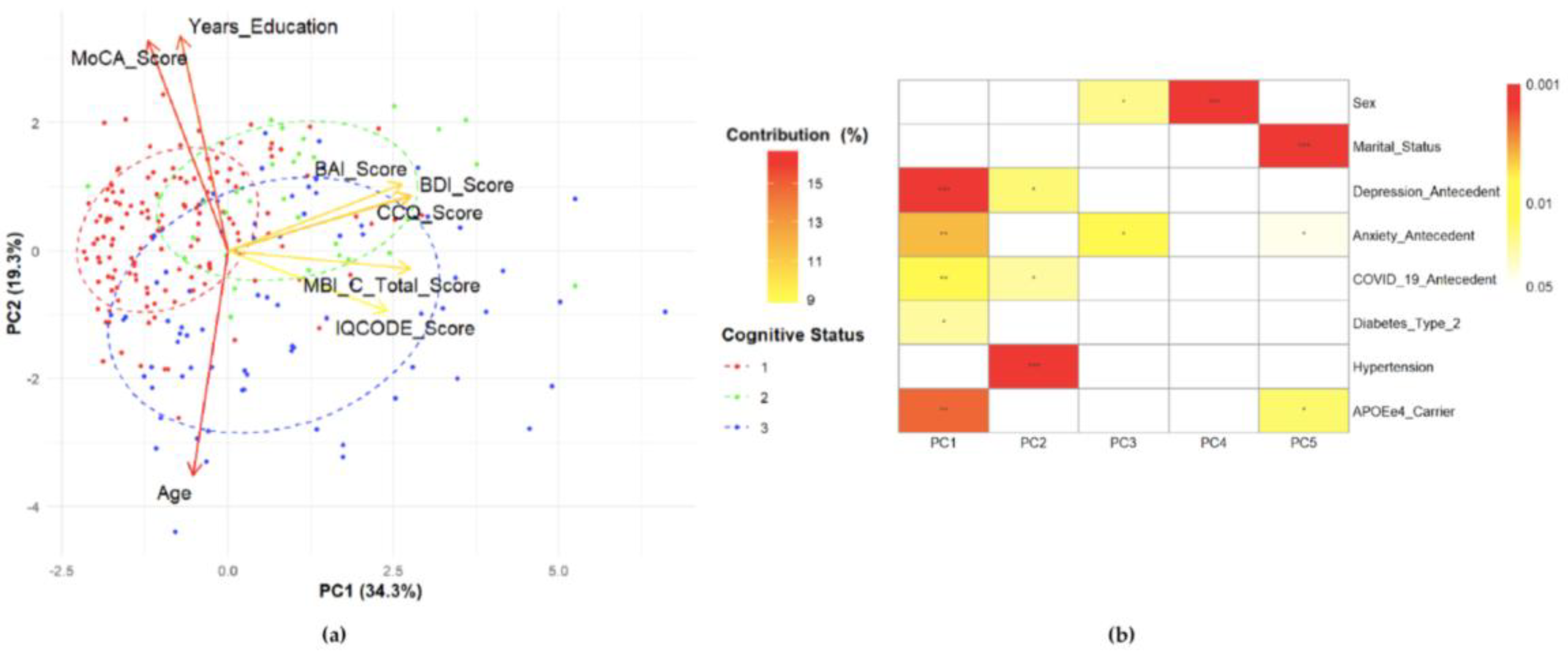

3.6. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| CCQ | Cognitive Complaint Questionnaire |

| CTAD | Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease Conference |

| INAPAM | Instituto Nacional de las Personas Adultas Mayores |

| INNNMVS | Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía, Manuel Velasco Suárez |

| IQCODE | Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline |

| ISTAART | International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment |

| MBI | Mild Behavioral Impairment |

| MBI-C | Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist |

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| MM | Mexican-Mestizos |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| NC | Normal Cognition |

| NPS | Neuropsychiatric symptoms |

| PCA | Principal Components Analysis |

| SCD | Subjective cognitive decline |

| SECIHTI | Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación |

| SNV | Single Nucleotide Variants |

| UAM | Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana |

| UNAM | Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México |

References

- Cummings, J. The Role of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Research Diagnostic Criteria for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021, 29(4), 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: Provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Demen 2016, 12(2), 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.; Rosenberg, P.; Ballard, C.; Vellas, B.; Miller, D.; Gauthier, S.; Carrillo, M. C.; Lyketsos, C.; Ismail, Z. CTAD Task Force Paper: Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in AD: Clinical Trials Targeting Mild Behavioral Impairment: A Report from the International CTAD Task Force. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2024, 11(1), 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo-Ortega, E.A. Are we missing detection of dementia at early stages in Mexico? A survey of dementia experts. Rev Invest Salud Publica 2024, 66(6), 897–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banning, L.C.P.; Ramakers, I.H.G.B.; Köhler, S.; Bron, E. E.; Verhey, F. R. J.; de Deyn, P. P.; Claassen, J. A. H.R.; Koek, H. L.; Middelkoop, H. A. M.; van der Flier, W. M.; van der Lugt, A.; Aalten, P. Initiative, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Group. The Association Between Biomarkers and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Across the Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020, 28(7), 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozza, M.; Boccardi, V. A narrative review on mild behavioural impairment: an exploration into its scientific perspectives. Aging Clin Exp Res 2023, 35(9), 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikostopoulos, A. Mapping the Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease Using Biomarkers, Cognitive Abilities, and Personality Traits: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15(9), 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.A.; Macedo, L.B.C.; Foss, M.P. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as a prodromal factor in Alzheimer’s type neurodegenerative disease: A scoping review. Clin Neuropsychol 2023, 38(5), 1031–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, Z.; McGirr, A.; Gill, S.; Hu, S.; Forkert, N. D.; Smith, E. E. Mild Behavioral Impairment and Subjective Cognitive Decline Predict Cognitive and Functional Decline. J Alzheimers Dis 2021, 80(1), 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, Z. The Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist (MBI-C): A Rating Scale for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Pre-Dementia Populations. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 56(3), 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, P. A review of current evidence for mild behavioral impairment as an early potential novel marker of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1099333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.X.; Rehman, T.; Nathan, S.; Durrani, R.; Potvin, O.; Duchesne, S.; Pike, G. B.; Smith, E. E.; Ismail, Z. Neuropsychiatric symptoms: Risk factor or disease marker? A study of structural imaging biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and incident cognitive decline. Hum Brain Mapp 2024, 45(13), e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, M.; Smith, E.E.; Ismail, Z. Improving dementia prognostication in cognitively normal older adults: conventional versus novel approaches to modelling risk associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Br J Psychiatry 2025, 226(3), 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z. Affective and emotional dysregulation as pre-dementia risk markers: exploring the mild behavioral impairment symptoms of depression, anxiety, irritability, and euphoria. Int Psychogeriatr 2018, 30(2), 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creese, B.; Griffiths, A.; Brooker, H.; Corbett, A.; Aarsland, D.; Ballard, C.; Ismail, Z. Profile of mild behavioral impairment and factor structure of the Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist in cognitively normal older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2020, 32(6), 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-García, P.; López-Antón, R.; de la Cámara, C.; Santabárbara, J.; Lobo, E.; Lobo, A. Mild behavioral impairment in the general population aged 55+ and its association with incident dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 16(4), e12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortby, M.E.; Ismail, Z.; Anstey, K.J. Prevalence estimates of mild behavioral impairment in a population-based sample of pre-dementia states and cognitively healthy older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2018, 30(2), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Shea, Y. F.; Li, S.; Chen, R.; Mak, H. K.; Chiu, P. K.; Chu, L. W.; Song, Y. Q. Prevalence of mild behavioural impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics 2021, 21(1), 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.I.; ADNI. Prevalence of mild behavioural impairment and its association with cognitive and functional impairment in normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, and mild Alzheimer’s dementia. Psychogeriatrics 2024, 24(3), 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasutto, B.; Fattapposta, F.; Casagrande, M. Mild Behavioral Impairment and cognitive functions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2025, 105, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, H.J. Impact of Mild Behavioral Impairment on Longitudinal Changes in Cognition. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2024, 79(1), glad098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.L. Risk factors of mild behavioral impairment: a systematic review. Front Psychol 2025, 16, 1586418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuskova, V. Mild behavioral impairment in early Alzheimer’s disease and its association with APOE and BDNF risk genetic polymorphisms. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuermann, J.S. Mild behavioral impairment in people with mild cognitive impairment: Are the two conditions related? J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 102(3), 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.J.; Hyman, B.T.; Serrano-Pozo, A. Multifaceted roles of APOE in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2024, 20(8), 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genis-Mendoza, A.D. Programa de detección del alelo APOE-E4 en adultos mayores mexicanos con deterioro cognitivo. Gac Med Mex 2018, 154(5), 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, E. Exploring the Genetic Landscape of Mild Behavioral Impairment as an Early Marker of Cognitive Decline: An Updated Review Focusing on Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25(5), 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, D. Apathy and APOE in mild behavioral impairment, and risk for incident dementia. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2022, 8(1), e12370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyawong, W. Mild Behavioral Impairment as a Mediator of the Relationships Among Perceived Stress, Social Support, Physical Activity, and Cognitive Function in Older Adults with Transitional Cognitive Decline: A Structural Equation Modelling Analysis. Can J Aging 2025, 44(3), 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.X. Vascular risk factor associations with subjective cognitive decline and mild behavioral impairment. Brain Commun 2025, 7(3), fcaf163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creese, B. Genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease, cognition, and mild behavioral impairment in healthy older adults. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2021, 13(1), e12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Orduña, I. Detecting MCI and dementia in primary care: effectiveness of the MMS, the FAQ and the IQCODE. Fam Pract 2012, 29(4), 401–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, S.L.; Bruno, D. Validación del Cuestionario de Quejas Cognitivas. Neurología Argentina 2021, 13(3), 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Navarro, S.G. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for the Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Mexico. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr (Engl Ed) 2018, 47(4), 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N. Accuracy of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment tool for detecting mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19(7), 3235–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, E.A. Effects of Normative Adjustments to the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018, 26(12), 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, S. La estandarización del Inventario de Depresión de Beck para los residentes de la Ciudad de México. Salud Ment 1998, 21(3), 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, R. Versión mexicana del Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck: propiedades psicométricas. Rev Mex Psicol 2001, 18(2), 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Ser, T. Application of a Spanish version of the “Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly” in the clinical assessment of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997, 11(1), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguera-Ortiz, L.F. Mild behavioural impairment as an antecedent of dementia: presentation of the diagnostic criteria and the Spanish version of the MBI-C scale for its evaluation. Rev Neurol 2017, 65(7), 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y. Reliability and Validity of the Chinese Version of the Mild Behavioral Impairment Checklist for Screening for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2019, 70(3), 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, T. Relationship between Loneliness and Mild Behavioral Impairment: Validation of the Japanese Version of the MBI Checklist and a Cross-Sectional Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 97(4), 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20(8), 5143–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018, 14(4), 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19(3), 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016, 22(2 Dementia), 404–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winblad, B. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Internal Medicine J Intern Med 2004, 256(3), 240–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M.; Groenen, P.J.F; Hastie, T; Iodice D’Enza, A.; Markos, A.; Tuzhilina, H. Principal Component Analysis. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2(1), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Dal’Col Lúcio, A. metan: An R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Methods Ecol Evol 2020, 11(6), 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberena-Jonas, C. Genetic analysis of APOE reveals distinct origins and distribution of ancestry-enrichment haplotypes in the Mexican Biobank. Genes Dis 2025, 13(1), 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M. Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele is associated with Parkinson disease risk in a Mexican Mestizo population. Mov Disord 2007, 22(3), 417–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Magaña, J.J. Association between APOE polymorphisms and lipid profile in Mexican Amerindian population. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2019, 7(11), e958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, F. Prevalence of mild behavioral impairment in mild cognitive impairment and subjective cognitive decline, and its association with caregiver burden. Int Psychogeriatr 2018, 30(2), 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, Y.J. Mild Behavioral Impairment and Cerebrovascular Profiles Are Associated with Early Cognitive Impairment in a Community-Based Southeast Asian Cohort. Alzheimers Dis 2024, 97(4), 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. Prevalence of mild behavioural impairment domains: a meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics 2022, 22(1), 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, E.A. Time course of neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive diagnosis in National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centers volunteers. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2019, Apr18(11), 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H. Late-life emergence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and risk of cognitive impairment in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21(8), e70619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallo, S.C. Assessing mild behavioral impairment with the mild behavioral impairment checklist in people with subjective cognitive decline. Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31(2), 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taragano, F.E. Mild behavioral impairment and risk of dementia: a prospective cohort study of 358 patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2009, 70(4), 584–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R. Behavioural issues in late life may be the precursor of dementia- A cross sectional evidence from memory clinic of AIIMS, India. PLoS One 2020, 15(6), e0234514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E. Anxiety as a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Br J Psychiatry 2018, 213(5), 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creese, B.; Ismail, Z. Mild behavioral impairment: measurement and clinical correlates of a novel marker of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 2022, 14(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.N. Comorbid cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative burden in mild behavioural impairment and their impact on clinical trajectory. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2025, Mar 13, 37, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R. White matter hyperintensities and mild behavioral impairment: Findings from the MEMENTO cohort study. Cereb Circ Cogn Behav 2021, Sep 14:2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Smith, C.; Dichgans, M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurology Lancet Neurol 2019, 18(7), 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404(10452), 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NC (N=138) |

SCD (N=32) |

MCI (N=76) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sex (%) Male Female |

22 (15.9) 116 (84.1) |

4 (12.5) 28 (87.5) |

15 (19.7) 61 (80.3) |

0.616 |

|

Age (in years) μ ±SD Range |

69.42±6.27 60 – 87 |

69.4±74.08 60 – 87 |

70.91±6.40 60 – 85 |

0.277 |

|

Y. education μ±SD Range |

14.11±3.22 6 – 22 |

14.05±2.70 9 – 19 |

12.34±4.19 6 – 22 |

0.004** |

|

Marital status (%) W/o partner With partner |

81 (58.7) 57 (41.3) |

23 (71.9) 9 (28.1) |

40 (52.6) 36 (47.5) |

0.179 |

|

MoCA μ±SD Range |

26.72±1.65 25 – 30 |

26.94±1.41 25 – 30 |

21.26±2.31 12 – 24 |

≤0.001*** SCD vs MCI≤0.001*** NC vs MCI≤0.001*** |

|

CCQ μ±SD Min-Max |

10.04±6.04 0 – 21 |

28.31±5.99 22 – 43 |

18.07±12.57 0 – 54 |

≤0.001*** |

|

IQCODE μ±SD Range |

81.67±5.12 66 – 117 |

83.88±9.79 40 – 101 |

86.70±8.57 78 – 125 |

≤0.001*** NC vs SCD=0.004** NC vs MCI≤0.001*** |

|

BDI μ±SD Range |

4.31±4.31 0 – 22 |

8.22±5.98 1 – 23 |

7.78±6.50 0 – 25 |

≤0.001*** NC vs SCD≤0.001*** NC vs MCI≤0.001*** |

|

BAI μ±SD Range |

3.18±4.19 0 – 23 |

8.09±6.32 0 – 21 |

5.66±5.95 0 – 29 |

≤0.001*** NC vs SCD≤0.001*** NC vs MCI=0.004** |

|

APOE N (%) Allele ε2 Allele ε3 Allele ε4 |

5 (1.81) 250 (90.58) 21 (7.61) |

2 (3.13) 51 (79.69) 11 (17.18) |

3 (1.97) 129 (84.87) 20 (13.16) |

0.793 NC vs SCD&MCI=0.021 SCD vs NC&MCI=0.018 |

| Characteristic | Total (N= 246) |

MBI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=91) | No (N=155) | |||

|

Cognitive status (%) NC SCD MCI |

138 32 76 |

36 (26.1) 19 (59.4) 36 (47.4) |

102 (73.9) 13 (40.6) 40 (52.6) |

≤0.001*** ≤0.001*** 0.006** 0.032* |

|

Sex (%) Male Female |

41 205 |

19(46.3) 72 (35.1) |

22 (53.7) 133 (64.9) |

0.215 |

|

Age (years) |

μ±SD Range |

68.48±6.42 60 – 84 |

70.70±6.60 60 – 87 |

0.009** |

|

Y. education |

μ±SD Range |

13.73±3.79 6 – 22 |

13.46±3.44 6 – 22 |

0.379 |

|

Marital status (%) With partner W/o partner |

102 144 |

44 (48.4) 47 (51.6) |

58 (37.4) 97 (62.6) |

0.108 |

|

Antecedents (%)§ Depression Anxiety Diabetes type 2 Hypertension COVID-19 |

100 70 61 106 139 |

49 (53.8) 33 (36.3) 22 (24.2) 46 (50.5) 56 (61.5) |

51 (32.9) 37 (23.9) 39 (25.2) 60 (38.7) 83 (53.5) |

0.002* 0.041* 1.000 0.083 0.234 |

|

Clinical scales (μ±SD) MoCA CCQ IQCODE BDI BAI |

25.06±3.14 14.89±10.64 83.51±7.38 5.89±5.57 4.59±5.37 |

24.85±3.24 20.12±11.77 88.56±8.36 8.58±6.36 6.70±6.17 |

25.19±3.09 11.83±8.58 80.54±4.66 4.31±4.36 3.34±4.40 |

0.440 ≤0.001*** ≤0.001*** ≤0.001*** ≤0.001*** |

|

APOE alleles (%) ε2 ε3 ε4 # copies of ε4 allele 01 2 |

10 430 47 198 44 4 |

3 (1.65) 157 (86.26) 22 (12.09) 72 (79.1) 16 (17.6) 3 (3.3) |

7 (2.26) 273 (88.06) 30(9.68) 126 (81.3) 28(18.1) 1 (0.67) |

0.751 0.576 0.448 0.284 |

| MBI-C scoring (μ±SD) |

Carrier of APOEε4 allele | Number of copies of APOEε4 allele | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=48) |

No (N=198) |

p- value |

0(N=198) | 1 (N=44) |

2 (N=4) |

p-value | |

| Total MBI-C | 9.46±12.58 | 7.21±11.17 | 0.109 | 7.21±11.17 | 8.55± 11.70 | 19.50±19.28 | 0.114 |

| Decreased motivation | 1.75±2.92 | 1.33 ±2.92 | 0.129 | 1.33±2.92 | 1.61±2.80 | 3.25±2.87 | 0.039*↟ |

| Affective and emotional dysregulation | 2.50±3.81 | 2.24±3.67 | 0.716 | 2.24±3.67 | 2.34±3.74 | 4.25±4.79 | 0.456 |

| Impulse dyscontrol | 4.21±5.40 | 2.72 ±4.06 | 0.054 | 2.72±4.03 | 3.70±4.85 | 9.75 ±8.66 | 0.069 |

| Social inappropriateness | 0.56±1.17 | 0.57 ±1.24 | 0.848 | 0.57±1.23 | 0.55±1.19 | 0.75 ±0.58 | 0.626 |

| Abnormal perception or thought content |

0.44±1.54 | 0.36 ±1.19 | 0.932 | 0.36±1.19 | 0.34±1.44 | 1.50±2.38 | 0.063↡ |

| Variable | Odds Ratio [CI 95%] | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| NC SCD |

0.340 [0.199 - 0.581] 2.883 [1.348 - 6.166] |

< 0.001*** 0.006** |

| MCI Age≥70 years Age <70 years Subjective Cognitive Complaint (by CCQ) Informant Cognitive Complaint (by IQCODE) |

1.882 [1.082 - 3.272] 0.550 [0.325 - 0.929] 1.819[1.076 - 3.074] 4.706 [2.569 - 8.623] 15.889 [7.729 - 32.665] |

0.025* 0.025* 0.025* < 0.001*** < 0.001*** |

| Antecedent of depression | 2.379 [1.399 - 4.047] | < 0.001*** |

| Depression (by BDI) Antecedent of anxiety |

4.905 [2.595 - 9.271] 1.815 [1.032 - 3.192] |

< 0.001*** 0.039* |

| Anxiety (by BAI) | 2.833 [1.625 - 4.939] | < 0.001*** |

| Variable | Component | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Eigenvalue | 2.74 | 1.55 | 1.15 |

| % Variance Component | 34.3 | 19.3 | 14.4 |

| % Variance Variable CCQ BDI MBI-C BAI IQCODE MoCA Years of education Age |

20.276 20.146 20.113 18.293 15.323 3.800 1.328 0.719 |

1.940 1.982 0.204 2.865 2.337 28.340 29.767 32.564 |

1.359 14.992 19.506 20.181 35.246 0.313 3.173 5.231 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).