1. Introduction

Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and dependency among older adults worldwide, and its prevalence continues to rise due to global population aging [

1,

2]. An estimated 55 million people currently live with dementia, with over 60% residing in low- and middle-income countries [

1]. This growing burden underscores the urgent need for early detection strategies, as timely identification of cognitive impairment can facilitate interventions that preserve function and improve quality of life [

3].

Neuropsychological screening tools play a pivotal role in the early identification of cognitive decline [

4]. Among them, the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) [

5] is the most widely used and validated instrument in clinical and research settings [

6,

7]. Its ease of administration and broad application contribute to its utility in routine screening. However, several studies have raised concerns about its sensitivity in detecting early-stage dementia, particularly among individuals with low educational attainment [

8,

9,

10].

To overcome such limitations, alternative tools like the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) [

11] have been developed. MoCA offers broader coverage of cognitive domains, including executive function, visuospatial ability, and memory, and has demonstrated superior sensitivity in detecting mild cognitive impairment [

12,

13,

14]. Comparative studies indicate that MoCA may outperform MMSE in various populations, with stronger correlations to comprehensive neuropsychological batteries [

15,

16,

17].

Despite this evidence, there remains no consensus regarding optimal cut-off scores for these instruments, and performance may vary significantly based on sociodemographic factors such as education level [

11,

13]. Moreover, few studies have simultaneously examined the accuracy of MMSE and MoCA using educational adjustments in diverse older adult populations, highlighting the need for further comparative validation [

14,

18].

Therefore, this preliminary study aims to evaluate and compare the diagnostic accuracy of MMSE and MoCA in identifying cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Importantly, the analysis includes comparisons of standard and education-adjusted cut-offs to determine which approach provides greater sensitivity and specificity in early detection. These findings may guide future clinical decision-making and contribute to improving cognitive screening strategies in primary care and geriatric settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This comparative analytical study was conducted between January and September 2022 with a sample of 90 community-dwelling older adults (aged 60 years or older) receiving care at the University Hospital of the Federal University of the São Francisco Valley (HU-UNIVASF), managed by the Brazilian Company of Hospital Services (EBSERH). The study followed the translated and updated versions of the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement [

19,

20], following international guidelines for reporting observational research [

21].

The required sample size was estimated using G*Power software (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany, version 3.1.9.4, 2019). For a two-tailed independent samples t-test with an expected medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.50), α = 0.05, and statistical power (1−β) of 0.80, a minimum of 64 participants (32 per group) was required. To account for potential data loss or ineligibility, the sample was increased by approximately 40%, resulting in a final sample of 90 older adults. This sample size was sufficient to detect statistically meaningful differences in cognitive performance and diagnostic accuracy between groups.

Eligible participants included male and female outpatients aged ≥60 years, with at least four years of formal education, regardless of marital status or family income. Recruitment occurred at the HU-UNIVASF Polyclinic outpatient center.

Inclusion criteria comprised the absence of Parkinson’s disease, history of stroke, motor or sensory deficits, recent changes in medication regimens, hypertension, or current use of more than three medications for cardiovascular disease. Additionally, participants were required to score >18 on the Beck Depression Inventory [

22]. Individuals who declined to provide informed consent or did not complete all study procedures were excluded.

Cognitive status was determined by a psychiatrist using the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale [

23,

24]. Participants with CDR = 0 were classified as cognitively preserved and allocated to the control group (n = 39), while those scoring between 0.5 and 2 were categorized as cognitively impaired (n = 51).

The study followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, revised in 2013) and complied with the regulations established in Resolutions 466/2012 and 510/2016 of the Brazilian National Health Council. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medical Sciences of Pernambuco under evaluation report No. 4.389.686 and certificate of presentation for ethical appraisal (CAAE) No. 38942320.4.0000.5192. All participants provided written informed consent by signing the informed consent form before enrolment.

2.2. Sociodemographic and Health Status Assessment

Sociodemographic and economic data were collected using standardized questionnaires based on Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) criteria. Variables included age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity (self-reported), occupation, educational attainment, and household income (expressed in minimum wages).

General health status was assessed using a structured questionnaire encompassing medical history, current health conditions, and medication use. Two trained research assistants administered all interviews, which were conducted face-to-face in a private setting and lasted approximately 20–30 minutes.

2.3. Functional and Clinical Evaluation

Functional assessment was conducted using the Katz index of independence in activities of daily living [

25] and the Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale [

26], with the latter adapted for use in the Brazilian older adult population [

27].

The Katz index evaluates an individual’s level of independence in performing basic activities of daily living (ADLs). It assesses six self-care tasks, arranged hierarchically by complexity: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding. Each task is scored dichotomously—independent (1 point) or dependent (0 points)—yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 6 [

25]. A score of 6 indicates full independence, whereas a score of 0 reflects total dependence across all assessed activities.

By contrast, the Lawton scale evaluates an individual’s ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), which require greater cognitive and physical capacity [

26]. The version used in this study was the Brazilian adaptation [

27], comprising nine items that assess competencies such as telephone use, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, transportation, medication management, financial handling, and minor household repairs. Scores range from 9 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater functional independence.

2.4. Cognitive Assessment

Cognitive function was assessed using the MMSE and the MoCA. The MMSE evaluates multiple cognitive domains, including orientation, memory, attention, language, and visuoconstructional skills [

5]. Cognitive impairment was initially classified based on the standardized cutoff score of <24 points [

5]. Additionally, we employed education-adjusted cutoff scores recommended by Brucki et al. [

28]: 25 points for individuals with 1–4 years of education, 26.5 points for those with 5–8 years, 28 points for those with 9–11 years, and 29 points for participants with ≥12 years of formal education.

The MoCA was used to provide a more comprehensive assessment of cognitive abilities, particularly executive function, abstraction, memory, attention, visuospatial skills, naming, orientation, and language [

11]. The standard cutoff score for cognitive impairment detection was <26 points, with one additional point added to scores for individuals with ≤12 years of education [

11]. Furthermore, education-adjusted cutoff values proposed by Pinto et al. [

29] were also applied: scores ≤21 points for participants with ≥12 years of schooling and ≤20 points for those with 4–12 years of education were considered indicative of cognitive impairment.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were double-entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States of America [USA], release 16.0.2, 2007) to ensure accuracy and consistency. Descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the sample: categorical variables were presented as absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%), and continuous variables as means ± standard deviations (SD). Normality of distribution was verified using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Between-group comparisons were conducted using independent samples t-tests for continuous variables. Pearson’s chi-square test (χ²) or Fisher’s exact test was employed as appropriate for categorical variables.

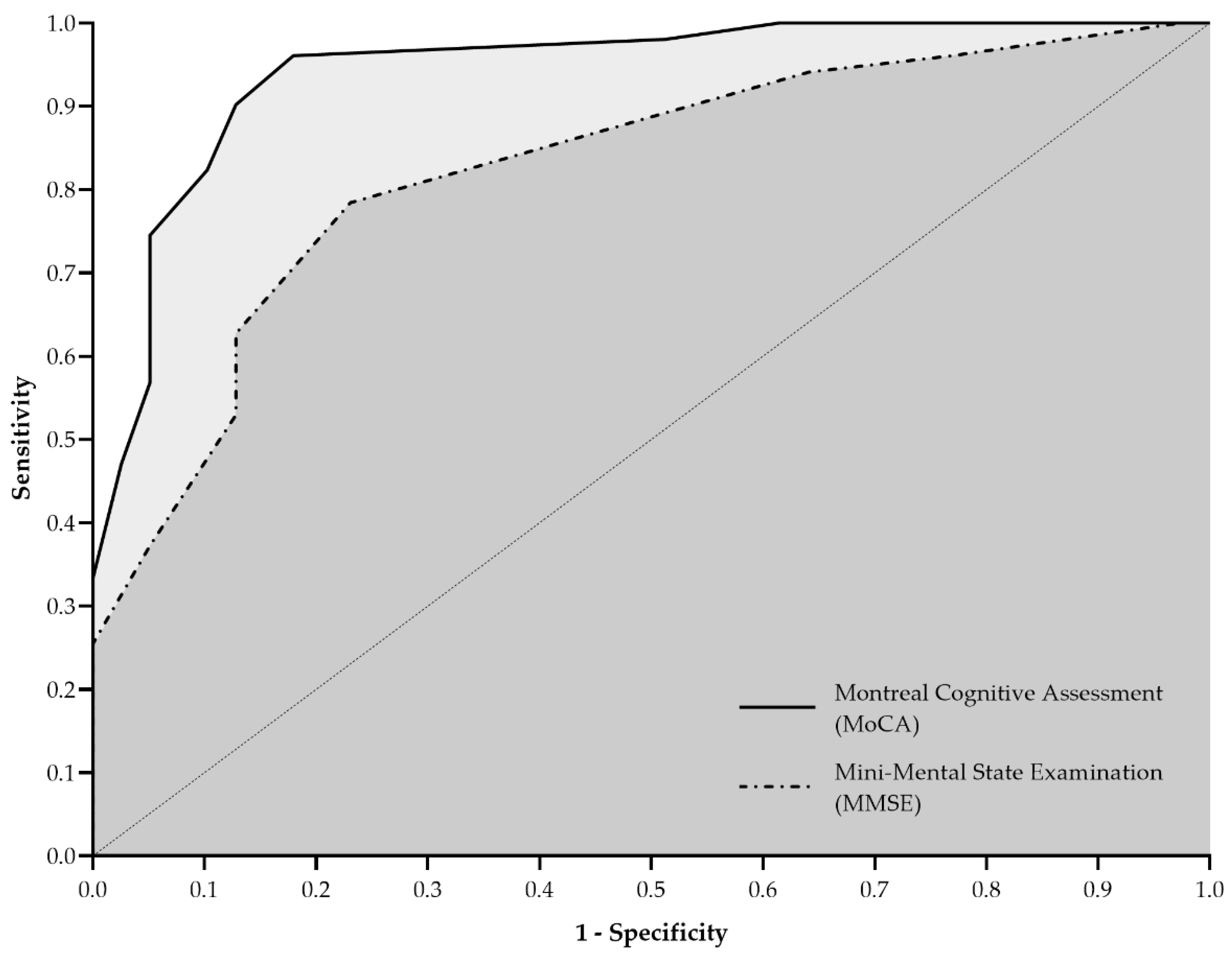

Diagnostic accuracy for MMSE and MoCA was evaluated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses. The areas under the ROC curve (AUC) were calculated along with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and standard errors (SE). Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPV), and negative predictive values (NPV) were computed for both screening instruments, considering standard and education-adjusted cutoff scores. Agreement between the cognitive impairment classification based on MMSE/MoCA scores and the CDR classification (reference standard) was assessed using Cohen’s kappa (κ). Interpretation of κ values was as follows: <0.40 indicated poor agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 good agreement, and >0.80 very good agreement. All p-values and 95% CIs were calculated and reported with exact values. A two-tailed significance level of 5% (p ≤ 0.05) was adopted for all statistical tests.

3. Results

The study included 90 older adults ranging from 60 to 90 years, with an average age of 69.0 ± 6.5 years. Most participants were female (n = 62; 68.9%) and reported a monthly income equal to or lower than two minimum wages (n = 64; 71.1%). Participants with cognitive impairment were significantly older (p < 0.001), had fewer years of education (p = 0.001), and reported lower monthly income (p = 0.026) compared to those without cognitive impairment (

Table 1). Additionally, the cognitively impaired group presented lower functional independence, demonstrated by poorer scores in ADL and IADL (both p < 0.001). MMSE and MoCA cognitive screening results were also significantly lower among participants with cognitive impairment (p < 0.001).

Figure 1 illustrates the ROC curves for MMSE and MoCA. The MMSE yielded an AUC of 0.826 (95% CI: 0.740–0.911; SE: 0.044; p < 0.001), with sensitivity and specificity of 78.4% (95% CI: 65.4–87.5%) and 76.9% (95% CI: 61.7–87.4%), respectively. MoCA demonstrated superior discriminative ability, presenting an AUC of 0.943 (95% CI: 0.896–0.991; SE: 0.024; p < 0.001), with higher sensitivity (90.2%; 95% CI: 79.0–95.7%) and specificity (87.2%; 95% CI: 73.3–94.4%).

Using standardized cutoff scores, the overall diagnostic accuracy for cognitive impairment was 73.3% (95% CI: 63.0–82.1%) for MMSE and 62.2% (95% CI: 51.4–72.2%) for MoCA (

Table 2). MMSE exhibited a PPV of 0.87 and an NPV of 0.64, whereas MoCA displayed a PPV of 0.60 and an NPV of 1.00.

When cutoff scores were adjusted according to years of education, MMSE classified 70.0% (n = 63) of older adults as cognitively impaired, compared to 64.4% (n = 58) by MoCA. With education-adjusted cutoffs, MoCA accuracy improved markedly to 87.8% (95% CI: 79.2–93.7%), surpassing MMSE accuracy at 71.1% (95% CI: 60.6–80.2%). The PPV and NPV values were notably higher for MoCA (PPV = 0.85; NPV = 0.94) compared to MMSE (PPV = 0.70; NPV = 0.74).

Finally, the agreement between cognitive screening tests and CDR varied. MMSE showed moderate agreement with standardized cutoffs (κ = 0.479), but poor agreement when using education-adjusted cutoffs (κ = -0.132). In contrast, MoCA demonstrated poor agreement with standardized cutoffs (κ = -0.053) but good agreement (κ = 0.746) when adjusted for educational level, highlighting the importance of education-adjusted criteria.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that the MoCA outperformed the MMSE in screening cognitive impairment among older adults, exhibiting superior diagnostic accuracy in terms of both sensitivity (74.5% vs. 62.8%) and specificity (94.9% vs. 87.2%). Furthermore, MoCA achieved an AUC above 0.90, indicating excellent discriminative capacity for detecting early neurocognitive decline. These findings align closely with previous evidence suggesting that MoCA is more sensitive than MMSE in detecting subtle cognitive deficits, particularly in the initial stages of impairment [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Several factors are likely to contribute to the superior performance of MoCA. This instrument includes a broader assessment of executive functions, attention, visuospatial abilities, and abstraction, domains often impaired early in cognitive decline [

11]. Previous research has consistently highlighted that MoCA contains tasks with a higher difficulty level, effectively capturing mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cases that MMSE might overlook [

34,

35]. Moreover, Nagaratnam et al. [

36] noted that MMSE tends to have limited sensitivity and is best suited for assessing more advanced cognitive impairment or dementia, whereas MoCA is advantageous for detecting mild and subtle changes across multiple cognitive domains.

The current results are consistent with growing evidence that supports the superior diagnostic performance of the MoCA over the MMSE in detecting early cognitive changes, particularly MCI. As emphasized by Breton, Casey, and Arnaoutoglou [

32], MoCA is more adept at capturing cognitive heterogeneity among older adults, enhancing its sensitivity to early and subtle impairments. Recent meta-analytical data reinforce this assertion. For instance, Malek-Ahmadi and Nikkhahmanesh [

37] highlighted MoCA’s higher diagnostic accuracy in identifying amnestic MCI, a precursor of Alzheimer’s disease. Complementing these findings, the comprehensive review by Oleksy et al. [

33] concluded that MoCA consistently outperforms MMSE across a variety of clinical scenarios, particularly in cases where executive dysfunction, visuospatial deficits, or attention-related disturbances are predominant. Notably, their synthesis of over 60 studies showed MoCA’s AUC ranging from 0.84 to 0.94 for MCI detection, compared to lower and more variable MMSE estimates, confirming MoCA’s clinical superiority.

Educational level is widely recognized as a critical confounder in cognitive testing, affecting both raw scores and diagnostic thresholds. This issue was carefully addressed in the present study by implementing education-adjusted cutoff scores for both MMSE and MoCA. As observed here and in prior studies [

14,

29,

33], older adults with fewer years of formal education exhibited significantly lower cognitive performance, underscoring the role of education as a proxy for cognitive reserve. Xu et al. [

38], in a large-scale meta-analysis, confirmed a clear dose-response relationship between years of education and reduced dementia risk. More recently, Lövdén et al. [

39] have expanded on this evidence, demonstrating that longer formal education enhances resilience against cognitive decline across multiple domains, including working memory, processing speed, and verbal fluency. The incorporation of education-adjusted cutoffs thus minimizes misclassification and enhances diagnostic accuracy, particularly when using MoCA, which retained stronger agreement with CDR classifications in this study.

Adjusting neuropsychological test scores based on educational attainment significantly reduces misclassification bias in cognitive assessments. In this study, MoCA maintained a stronger agreement with the CDR scale than MMSE when education-adjusted cutoffs were applied, reinforcing its superior discriminative performance. These findings are consistent with recent evidence from Kistler-Fischbacher et al. [

40], who demonstrated that both MMSE and MoCA scores vary meaningfully according to years of formal education. In their large, multicenter European study, older adults with lower educational levels (≤12 years) consistently showed lower MoCA median scores compared to those with higher education. This underscores the need to account for educational background when interpreting cognitive screening results. Educational adjustment helps prevent overdiagnosis of cognitive impairment, particularly among individuals with limited formal education, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy and equity in diverse populations.

It is also important to highlight that educational attainment can influence cognitive biases during assessments, potentially leading to diagnostic confusion. Stanovich and West [

41] observed that although more educated individuals generally performed better on cognitive assessments, they remained susceptible to specific cognitive biases that could complicate diagnostic interpretation. Therefore, the educational adjustments applied in this study were crucial not only for reducing false positives but also for mitigating the potential effects of such biases, improving the reliability of cognitive impairment screening [

29,

30].

Beyond educational attainment, age and functional capacity emerged as important differentiators between groups. Older adults with cognitive impairment exhibited poorer performance in both basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL and IADL). These functional deficits reflect the broader clinical implications of cognitive decline, emphasizing the critical role of integrating functional assessments into cognitive screening processes to enhance diagnostic accuracy [

42,

43,

44]. Functional evaluations offer essential insights into the practical impact of cognitive impairment, highlighting the necessity of a multidimensional assessment approach.

This study’s strengths notwithstanding, certain limitations must be recognized. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, restricting the interpretation to associative relationships. The absence of randomization introduces potential selection biases, affecting the generalizability of findings to other populations. Additionally, this investigation did not classify cognitive impairment into specific subtypes, such as amnestic or non-amnestic, nor did it distinguish among major or mild neurocognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Lewy body dementia, vascular cognitive impairment, frontotemporal dementia, or traumatic brain injury. Future studies should incorporate a more detailed categorization of cognitive impairment, integrating neuroimaging or biomarkers to achieve greater diagnostic precision and potentially elucidate distinct pathological mechanisms underlying different neurocognitive disorders.

5. Conclusions

MoCA demonstrated greater sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic accuracy than MMSE for screening cognitive impairment among older adults, particularly when adjusting for education. These findings emphasize the critical need for appropriate selection and educational adjustment of cognitive assessment tools to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Additionally, integrating functional assessments into cognitive evaluations provides comprehensive insight into the clinical implications of cognitive changes, facilitating early identification, diagnosis, and intervention in neurocognitive disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.A.M., L.A.R.M., M.d.M.N., and P.A.S.; data curation: P.A.M. and L.R.R.d.S.M.; formal analysis: P.A.M., A.B.d.C.R., A.S.L.R., L.R.R.d.S.M., B.B.G., and P.A.S.; funding acquisition: P.A.S.; investigation: P.A.M., L.P.d.C.C., A.B.d.C.R., A.S.L.R., L.R.R.d.S.M., and M.d.M.N.; methodology: P.A.M., L.A.R.M., M.d.M.N., B.B.G., and P.A.S.; project administration: P.A.S.; resources: P.A.M., L.P.d.C.C., L.A.R.M., A.S.L.R., L.R.R.d.S.M., and M.d.M.N.; software: M.d.M.N., B. B. G., and P.A.S.; supervision: L.A.R.M., and M.d.M.N.; validation: P.A.M., L.P.d.C.C., A.B.d.C.R., B. B. G., and P.A.S.; visualisation: L.R.R.d.S.M.; writing—original draft: P.A.M., L.P.d.C.C., L.A.R.M., A.B.d.C.R., L.R.R.d.S.M. and P.A.S.; writing—review and editing: A.S.L.R., M.d.M.N., B.B.G., and P.A.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Pernambuco—FACEPE [grant numbers APQ-0246-4.06/14, APQ-1413-4.08/21]. This study also received partial financial support from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES) [Finance Code 001]. In addition, CAPES awarded a doctoral scholarship to Paula Andreatta Maduro and Leandro Paim da Cruz Carvalho, and Alaine Souza Lima Rocha was granted a doctoral scholarship by the FACEPE [grant number IBPG-0393-4.01/17]. Finally, Paulo Adriano Schwingel was awarded a Research Productivity Grant (BPP) from the FACEPE [grant number BPP-0003-4.01/24].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, revised in 2013) and complied with all regulatory requirements outlined in Resolutions 466/2012 and 510/2016 of the Brazilian National Health Council. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Medical Sciences of Pernambuco (CEP-FCM/PE) under Evaluation Report Number 4.389.686 and Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appraisal (CAAE) Number 38942320.4.0000.5192.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the study participants for their invaluable contributions. We would also like to thank Godson Sebastião Chaves Teixeira Junior, MD (HU-UNIVASF/EBSERH), whose data collection and ongoing support were instrumental to the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADLs |

activities of daily living |

| AUC |

area under the curve |

| CAAE |

certificate of presentation for ethical appraisal |

| CDR |

Clinical Dementia Rating |

| EBSERH |

Brazilian Company of Hospital Services |

| HU-UNIVASF |

University Hospital of the Federal University of the São Francisco Valley |

| IADLs |

instrumental activities of daily living |

| IBGE |

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| MMSE |

mini-mental state examination |

| MoCA |

Montreal cognitive assessment |

| MW |

minimum wage |

| NPV |

negative predictive values |

| PPV |

positive predictive values |

| ROC |

receiver operating characteristic |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| SE |

standard error |

| STROBE |

strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology |

| USA |

United States of America |

References

- World Health Organization. Global status report on the public health response to dementia; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.; Ali, G.-C.; Guerchet, M.; Prina, A.M.; Albanese, E.; Wu, Y.-T. recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther 2016, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduro, P.A.; Alcides, L.; Maduro, R.; Lima, P.E.; Clara, A.; Silva, C.; De, R.; Montenegro Da Silva, C.; Souza, A.; Rocha, L.; et al. cardiac autonomic modulation and cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults: a preliminary study. Neurol Int 2025, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Lin, J.; Bat, B.K.K.; Chan, J.Y.C.; Tsoi, K.K.F.; Yip, B.H.K. Diagnostic accuracy of dementia screening tools in the Chinese population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 167 diagnostic studies. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska, N.; Sokołowski, R.; Mazur, E.; Podhorecka, M.; Polak-Szabela, A.; Kȩdziora-Kornatowska, K. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test better suited than the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) detection among people aged over 60? Meta-Analysis. Psychiatr Pol 2016, 50, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.H.; Yean Lee, W.; Hilal, S.; Saini, M.; Wong, T.Y.; Chen, C.L.H.; Venketasubramanian, N.; Ikram, M.K. Comparison of the Montreal cognitive assessment and the mini-mental state examination in detecting multi-domain mild cognitive impairment in a Chinese sub-sample drawn from a population-based study. Int Psychogeriatr 2013, 25, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aevarsson, Ó.; Skoog, I. A longitudinal population study of the mini-mental state examination in the very old: relation to dementia and education. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2000, 11, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borson, S.; Scanlan, J.; Brush, M.; Vitaliano, P.; Dokmak, A. The mini-cog: a cognitive “vital signs” measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000, 15, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Edwards, M.; Johnson, L.; Hall, J.; Gamboa, A.; O’jile, J. Texas mexican american adult normative studies: normative data for commonly used clinical neuropsychological measures for english- and spanish-speakers. Dev Neuropsychol 2018, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.; Simões, M.R.; Alves, L.; Santana, I. Montreal cognitive assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2013, 27, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, B.; Middleton, L.E.; Masellis, M.; Stuss, D.T.; Harry, R.D.; Kiss, A.; Black, S.E. Criterion and convergent validity of the Montreal cognitive assessment with screening and standardized neuropsychological testing. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013, 61, 2181–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Peng, A.; Lai, W.; Wu, J.; Ji, S.; Hu, D.; Chen, S.; Zhu, C.; Hong, Q.; Zhang, M.; et al. Impacts of education level on Montreal cognitive assessment and saccades in community residents from western China. Clin Neurophysiol 2024, 161, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julayanont, P.; Tangwongchai, S.; Hemrungrojn, S.; Tunvirachaisakul, C.; Phanthumchinda, K.; Hongsawat, J.; Suwichanarakul, P.; Thanasirorat, S.; Nasreddine, Z.S. The Montreal cognitive assessment-basic: a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in illiterate and low-educated elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015, 63, 2550–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, V.; Foroughan, M.; Chehrehnegar, N. Psychometric properties of the Persian Montreal Cognitive assessment in mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2021, 11, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Andersson, B.; Wong, G.H.Y.; Lum, T.Y.S. Longitudinal measurement properties of the Montreal cognitive assessment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2022, 44, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Yang, S.; Park, J.; Kim, B.C.; Yu, K.-H.; Kang, Y. Effect of education on discriminability of Montreal cognitive assessment compared to mini-mental state examination. Dement Neurocogn Disord 2023, 22, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; Blettner, M.; et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, M.; Cardoso, L.O.; Bastos, F.I.; Magnanini, M.M.F.; da Silva, C.M.F.P. STROBE initiative: guidelines on reporting observational studies. Rev Saude Publica 2010, 44, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; pp. 178–179. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.P.; Berg, L.; Danziger, W.L.; Coben, L.A.; Martin, R.L. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982, 140, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993, 43, 2412–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil; Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde; Departamento de Atenção Básica. Ageing and health of the elderly person; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, 2006; ISBN 85-334-1273-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brucki, S.M.D.; Nitrin, R.; Caramelli, P.; Bertolucci, P.H.F.; Okamoto, I.H. Suggestions for utilization of the mini-mental state examination in Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2003, 61, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.C.C.; Santos, M.S.P.; Machado, L.; Bulgacov, T.M.; Rodrigues-Junior, A.L.; Silva, G.A.; Costa, M.L.G.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Sougey, E.B. Optimal cutoff scores for dementia and mild cognitive impairment in the Brazilian version of the Montreal cognitive assessment among the elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2019, 9, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, T.C.C.; Machado, L.; Bulgacov, T.M.; Rodrigues-Júnior, A.L.; Costa, M.L.G.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Sougey, E.B. Is the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the elderly? Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, F.; Su, C.; Du, W.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Su, W.; et al. A comparison of the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) with the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, A.; Casey, D.; Arnaoutoglou, N.A. Cognitive tests for the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), the prodromal stage of dementia: meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019, 34, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksy, P.; Zieliński, K.; Buczkowski, B.; Sikora, D.; Góralczyk, E.; Zając, A.; Mąka, M.; Papież, Ł.; Kamiński, J. Cognitive function tests: application of MMSE and MoCA in various clinical settings- a brief overview. Quality in Sport 2024, 34, 56285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.A.; Almeida, A.L.M. de; Paraízo, M. de A.; Corrêa, J.O. do A.; Dias, D.D.S.; Fernandes, N. da S.; Ezequiel, D.G.A.; Paula, R.B. de; Fernandes, N.M. da S. Cross-sectional assessment of mild cognitive impairment in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease and its association with inflammation and changes seen on MRI: what the eyes cannot see. Braz J Nephrol 2022, 44, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecek, M.; Stepankova, H.; Lukavsky, J.; Ripova, D.; Nikolai, T.; Bezdicek, O. Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA): normative data for old and very old Czech adults. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2017, 24, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaratnam, J.M.; Sharmin, S.; Diker, A.; Lim, W.K.; Maier, A.B. Trajectories of mini-mental state examination scores over the lifespan in general populations: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin Gerontol 2022, 45, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malek-Ahmadi, M.; Nikkhahmanesh, N. Meta-analysis of montreal cognitive assessment diagnostic accuracy in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Front Psychol 2024, 15, 1369766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Tan, M.S.; Tan, L.; Li, J.Q.; Zhao, Q.F.; Yu, J.T. Education and risk of dementia: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Mol Neurobiol 2016, 53, 3113–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövdén, M.; Fratiglioni, L.; Glymour, M.M.; Lindenberger, U.; Tucker-Drob, E.M. Education and cognitive functioning across the life span. Psychol Sci Public Interest 2020, 21, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kistler-Fischbacher, M.; Gohar, G.; de Godoi Rezende Costa Molino, C.; Geiling, K.; Meyer-Heim, T.; Kressig, R.W.; Orav, E.J.; Vellas, B.; Guyonnet, S.; da Sliva, J.A.P.; et al. Cognitive function in generally healthy adults age 70 years and older in the 5-country DO-HEALTH study: MMSE and MoCA scores by sex, education and country. Aging Clin Exp Res 2025, 37, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanovich, K.E.; West, R.F. Natural myside bias is independent of cognitive ability. Think Reason 2007, 13, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekäläinen, T.; Luchetti, M.; Sutin, A.; Terracciano, A. Functional capacity and difficulties in activities of daily living from a cross-national perspective. J Aging Health 2023, 35, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ord, A.S.; Phillips, J.I.; Wolterstorff, T.; Kintzing, R.; Slogar, S.M.; Sautter, S.W. Can deficits in functional capacity and practical judgment indicate cognitive impairment in older adults? Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2021, 28, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.T.; Jang, Y.; Chang, W.Y. How do impairments in cognitive functions affect activities of daily living functions in older adults? PLoS One 2019, 14, e0218112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).