Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

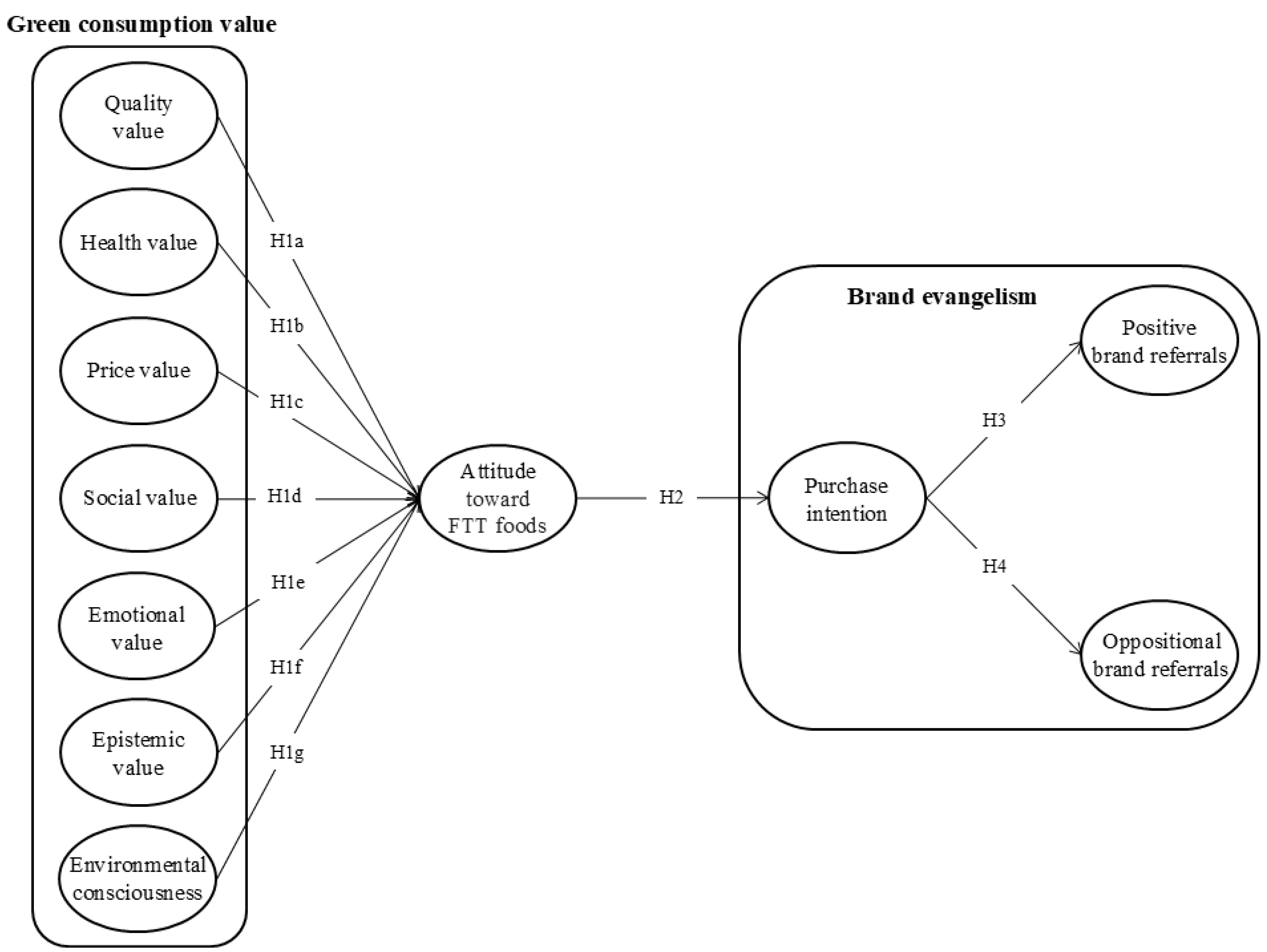

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Green Consumption Value

2.2. Relationship Between Green Consumption Value and Attitude Toward FTT Foods

2.3. Relationship Between Attitude toward FTT Foods and Purchase Intentions of Brand Evangelism

2.4. Relationship Between Sub-Variables in Brand Evangelism

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Instrument

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. CFA of the Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model Hypothesis Testing and SEM

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Informamarkets. What is Farm to Table. Available online: https://foodnhotelasia.com/glossary/fnb/farm-to-table/ (accessed 3 August 2025).

- Wilson, D. Chemical sensors for farm-to-table monitoring of fruit quality. Sensors 2021, 21, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.F.P.D.; Chin, W.L. The role of farm-to-table activities in agritourism towards sustainable Development. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Hassan, S.S.; Fayyad, S. Farm-to-fork and sustainable agriculture practices: perceived economic benefit as a moderator and environmental sustainability as a mediator. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.M.; Liu, C.R.; Wang, Y.C.; Chen, H. Sensory experience at farm-to-table events (SEFTE): conceptualization and scale development. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruetharadhol, P.; Gebsombut, N. A bibliometric analysis of food tourism studies in Southeast Asia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1733829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Huang, R. Is food tourism important to Chongqing (China)? J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Soltani Nejad, N.; Taheri Azad, F.; Taheri, B.; Gannon, M. J. Food consumption experiences: a framework for understanding food tourists’ behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Consumption values and market choices: theory and applications.; South-Western Pub: Cinicinnati, OH, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ruiz, M.P.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Izquierdo-Yusta, A.; Pick, D. The influence of food values on satisfaction and loyalty: evidence obtained across restaurant types. Int. J. Gast. Food Sci. 2023, 33, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, A.; Jamshidi, D. Food tourism value: investigating the factors that influence tourists to revisit. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 26, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Ghuman, K. The value proposition of food delivery apps from the perspective of theory of consumption value. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag 2021, 33, 1129–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.J.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, M.; Wang, P.; Kuah, A.T.H. Why wouldn’t green appeal drive purchase intention? Moderation effects of consumption values in the UK and China. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Antecedents to consumers’ green hotel stay purchase behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: the influence of green consumption value, emotional ambivalence, and consumers’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. Persp. 2023, 47, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, K.; Kishor, N. Influence of customer perceived values on organic food consumption behaviour: mediating role of green purchase intention. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2022, Online Published. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Galati, A.; Sharma, S. Explore, eat and revisit: does local food consumption value influence the destination’s food image? British Food J. 2023, 125, 4639–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Casidy, R. The role of brand reputation in organic food consumption: a behavioral reasoning perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laheri, V.K.; Lim, W.M.; Arya, P.K.; Kumar, S. A multidimensional lens of environmental consciousness: towards an environmentally conscious theory of planned behaviour. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Moon, H.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The effect of environmental values and attitudes on consumer willingness to pay more for organic menus: a value-attitude-behavior approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017a, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Pichler, E.A.; Hemetsberger, A. Who is spreading the word? the positive influence of extraversion on consumer passion and brand evangelism. In Proceedings of the American Marketing Association Winter Conference, 2007; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mvondo, G.F.N.; Jing, F.; Hussain, K.; Jin, S.; Raza, M.A. Impact of international tourists’ co-creation experience on brand trust, brand passion, and brand evangelism. Frontiers in Psychol. 2022a, 13, 866362. [Google Scholar]

- Guanqi, Z.; Nisa, Z.U. Prospective effects of food safety trust on brand evangelism: a moderated-mediation role of consumer perceived ethicality and brand passion. BMC Pub. Health 2023, 23, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Li, F.S. How does ritualistic service increase brand evangelism through E2C interaction quality and memory? the moderating role of social phobia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 116, 103624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, T.K.; Kumar, A.; Jakhar, S.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kazancoglu, I.; Nayak, S.S. Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, S.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Das, M.; Sigurdsson, V. The effect of customers’ brand experience on brand evangelism: the case of luxury hotels. Tour. Manag. Persp. 2023, 46, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, E.P.; Badrinarayanan, V. Influence of brand trust and brand identification on brand evangelism. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2013, 22, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: a review. Food Qual. Pref. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, Y.G. Consumer attitudes and buying behavior for green food products: from the aspect of green perceived value (GPV). British Food J. 2019, 121, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagarsamy, S.; Mehrolia, S.; Mathew, S. How green consumption value affects green consumer behaviour: the mediating role of consumer attitudes towards sustainable food logistics practices. Vision 2021, 25, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Paul, J.; Khan, T.; Abukhait, R.; Hussain, D. Customer evangelists: elevating hospitality through digital competence, brand image, and corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 126, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Das, B.; She, L. What affects consumers' choice behaviour towards organic food restaurants? by applying organic food consumption value model. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 2582–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, B.N. The defining role of environmental self-identity among consumption values and behavioral intention to consume organic food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Green purchase and sustainable consumption: a comparative study between European and non-European tourists. Tour. Manag. Persp. 2022, 43, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Gao, J. Effect of green consumption value on consumption intention in a pro-environmental setting: the mediating role of approach and avoidance motivation. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.A.; Lang, B.; Conroy, D.M. Are trust and consumption values important for buyers of organic food? a comparison of regular buyers, occasional buyers, and non-buyers. Appetite 2021, 161, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. Proc. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. Consumers’ willingness to patronize locally sourced restaurants: the impact of environmental concern, environmental knowledge, and ecological behaviour. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017b, 26, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, L.V.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Long, P.H.; Thi, P.Q.P.; Pham, N.T. Going green: predicting tourists' intentions to stay at eco-friendly hotels–the roles of green attitude and environmental concern. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 2723–2741. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, B.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers' attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Ruiz, M.P.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Izquierdo-Yusta, A.; Pick, D. The influence of food values on satisfaction and loyalty: evidence obtained across restaurant types. Int. J. Gast. Food Sci. 2023, 33, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvola, A.; Vassallo, M.; Dean, M.; Lampila, P.; Saba, A.; Lahteenmaki, L. Predicting intentions to purchase organic food: the role of affective and moral attitudes in the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2008, 50, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Guo, J.; Turel, O.; Liu, S. Purchasing organic food with social commerce: an integrated food technology consumption values perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Akram, M.; Asif, M. Investigating the influence of consumption values on healthy eating choices: the moderating role of healthy food awareness. DLSU Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 31, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Abbasi, A.Z.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Schultz, C.D.; Ting, D.H.; Ali, F. Local food consumption values and attitude formation: the moderating effect of food neophilia and neophobia. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 464–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: the development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Huang, Y.H. The influence factors on choice behavior regarding green products based on the theory of consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Weng, L. How do tourists’ value perceptions of food experiences influence their perceived destination image and revisit intention? a moderated mediation model. Foods 2024, 13, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Kim, W. G.; Anwer, Z.; Zhuang, W. Schwartz personal values, theory of planned behavior and environmental consciousness: how tourists’ visiting intentions towards eco-friendly destinations are shaped. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Haq, I.U.; Nadeem, H.; Albasher, G.; Alqatani, W.; Nawaz, A.; Hameed, J. How environmental awareness relates to green purchase intentions can affect brand evangelism? altruism and environmental consciousness as mediators. Revista Argentina de Clinica Psicologica 2020, 29, 811–825. [Google Scholar]

- Amani, D. Love is a verb: bolstering destination evangelism through the interplay of destination brand love and destination psychological ownership. J. Human. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2025, Online Published. [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Paul, J. Mass prestige, brand happiness and brand evangelism among consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvondo, G.F.N.; Jing, F.; Hussain, K.; Raza, M.A. Converting tourists into evangelists: exploring the role of tourists’ participation in value co-creation in enhancing brand evangelism, empowerment, and commitment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022b, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.L.; Cheung, C.T.Y.; Lit, K.K.; Wan, C.; Choy, E.T.K. Green consumption and sustainable development: the effects of perceived values and motivation types on green purchase intention. Bus. Strategy and the Environ. 2024, 33, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigit, I.; Atmaja, F.T. Analysis of the influence of brand attitude and brand engagement on positive brand referral Kopiko brand. Manag. Anal. J. 2024, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behaviour. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Wang, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Han, H. Nature-based solutions, mental health, well-being, price fairness, attitude, loyalty, and evangelism for green brands in the hotel context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduranga Arachchi, H.A.D.; Samarasinghe, G.D. Do fear-of-COVID-19 and regional identity matter for the linkage between perceived CSR and brand evangelism? a comparative analysis in South Asia. Europ. J. Manag. Stud. 2024, 29, 361–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swimberghe, K.; Darrat, M.A.; Beal, B.D.; Astakhova, M. Examining a psychological sense of brand community in elderly consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modelling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory.; McGraw Hill: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), Sage, Los Angeles, CA, 2016.

- Fornell, C.R.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.S.; Hou, F.; Kim, W.G.; Ahmad, W.; Ashraf, R.U. Modelling tourists' visiting intentions toward ecofriendly destinations: implications for sustainable tourism operators. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnou-Laaroussi, S.; Rjoub, H.; Wong, W.K. Sustainability of green tourism among international tourists and its influence on the achievement of green environment: evidence from North Cyprus. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Kudinova, I.; Samsonova, V.; Kawẹ, N. Innovative development of rural green tourism in Ukraine. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables and Items | SL | CR | AVE |

| Quality value (QUV) (α=0.863) | |||

| FTT foods provide a high standard of quality. | 0.808 | 0.903 | 0.700 |

| FTT foods provides good quality ingredients. | 0.818 | ||

| FTT foods are tasty. | 0.761 | ||

| FTT foods are prepared from fresh and aromatic ingredients. | 0.735 | ||

| Health value (HEV) (α=0.849) | |||

| FTT foods are hygienic. | 0.829 | 0.936 | 0.789 |

| FTT foods make me healthy. | 0.803 | ||

| FTT foods are safe. | 0.889 | ||

| FTT foods provide good nutrition. | 0.611 | ||

| Price value (PRV) (α=0.871) | |||

| FTT foods are reasonably priced. | 0.812 | 0.881 | 0.651 |

| FTT foods offer value for money. | 0.895 | ||

| FTT foods are a good product for the price. | 0.792 | ||

| The ingredients from this farm are relatively cheaper than those from regular markets. | 0.696 | ||

| Social value (SOV) (α=0.890) | |||

| Experiencing FTT foods help me to feel acceptable. | 0.660 | 0.910 | 0.629 |

| Experiencing FTT foods improve the way that I am perceived. | 0.744 | ||

| Experiencing FTT foods make a good impression on other people. | 0.753 | ||

| Experiencing FTT foods gives me prestige. | 0.792 | ||

| My friendship or kindship with my travel companion has increased while experiencing FTT foods. | 0.760 | ||

| Experiencing FTT foods helps me to interact with the people I travel with. | 0.747 | ||

| Emotional value (EMV) (α=0.839) | |||

| FTT foods can make me feel happy. | 0.649 | 0.900 | 0.644 |

| FTT foods can give me pleasure. | 0.723 | ||

| FTT foods make me feel excited. | 0.745 | ||

| FTT foods make me crave it. | 0.716 | ||

| FTT Foods make me feel relaxed. | 0.699 | ||

| Epistemic value(EPV) (α=0.796) | |||

| I would research FTT foods well before purchasing them. | 0.642 | 0.866 | 0.618 |

| I’m interested in learning more about FTT foods. | 0.700 | ||

| I enjoy looking for new and unique foods. | 0.738 | ||

| Before purchasing FTT foods, I would conduct a comprehensive search of all accessible possibilities. | 0.732 | ||

| Environmental consciousness (ENC) (α=0.795) | |||

| Strict global measures must be taken immediately to halt environmental decline. | 0.707 | 0.887 | 0.666 |

| While experiencing FTT foods, I realized that the environment is one of the most important issues facing society today. | 0.736 | ||

| Unless each of us recognizes the need to protect the environment, future generation will suffer the consequences. | 0.735 | ||

| While experiencing FTT foods, I realized that a substantial amount of money should be devoted to environmental protection. | 0.696 | ||

| Attitude toward FTT food (α=0.786) | |||

| Experiencing FTT foods is a valuable behavior. | 0.628 | 0.895 | 0.681 |

| Experiencing FTT foods is a beneficial behavior. | 0.716 | ||

| Experiencing FTT foods is a good idea. | 0.726 | ||

| I have a positive attitude toward FTT foods. | 0.702 | ||

| Purchase intention (PUI) (α=0.749) | |||

| I attend this event again and will purchase FTT foods because it is environmentally friendly. | 0.615 | 0.873 | 0.700 |

| I will participate in other FTT events to experience more diverse FTT foods. | 0.834 | ||

| I will visit my local FTT restaurants due to environmental concern. | 0.708 | ||

| Positive brand referrals (PBR) (α=0.714) | |||

| I will spread positive word of mouth about FTT foods and restaurants. | 0.757 | 0.825 | 0.613 |

| I would recommend FTT foods and restaurants. | 0.629 | ||

| If my friends are looking for a restaurant, I will tell FTT Restaurant them. | 0.601 | ||

| Oppositional brand referrals (OPR) (α=0.701) | |||

| I tell my friends not to visit to regular restaurants if possible. | 0.732 | 0.742 | 0.590 |

| I would likely spread negative word of mouth about regular grocery stores or restaurants. | 0.688 | ||

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 410 | 11 |

| 1. QUV | 0.837 | ||||||||||

| 2. HEV | 0.346 | 0.888 | |||||||||

| 3. PRV | -0.228 | -0.176 | 0.807 | ||||||||

| 4. SOV | 0.654 | 0.395 | -0237 | 0.793 | |||||||

| 5. EMV | 0.424 | 0.438 | -0.237 | 0.547 | 0.802 | ||||||

| 6. EPV | 0.431 | 0.275 | -0214 | 0.485 | 0.431 | 0.786 | |||||

| 7. ENC | 0.452 | 0.315 | -0.217 | 0.490 | 0.439 | 0.515 | 0.816 | ||||

| 8. ATT | 0.519 | 0.608 | -0.226 | 0.556 | 0.537 | 0.364 | 0.427 | 0.825 | |||

| 9. PUI | 0.308 | 0.443 | -0.163 | 0.375 | 0.446 | 0.260 | 0.361 | 0.510 | 0.837 | ||

| 10.PBR | 0.406 | 0.393 | -0.255 | 0.472 | 0.432 | 0.437 | 0.545 | 0.494 | 0.405 | 0.783 | |

| 11.OBR | 0.370 | 0.227 | -0.208 | 0.431 | 0.285 | 0.376 | 0.511 | 0.277 | 0.245 | 0.362 | 0.768 |

| Mean | 3.644 | 3.976 | 2.459 | 3.489 | 3.921 | 4.043 | 3.823 | 3.878 | 3.930 | 3.827 | 3.642 |

| S.D. | 0.694 | 0.552 | 0.821 | 0.691 | 0.583 | 0.616 | 0.575 | 0.518 | 0.551 | 0.556 | 0.730 |

| Hypotheses | β | t-value | Decision | |

| H1a | QUV → ATT | 0.177 | 3.204** | supported |

| H1b | HEV → ATT | 0.364 | 7.710** | supported |

| H1c | PRV → ATT | -0.036 | -1.055 | not suppoerted |

| H1d | SOV → ATT | 0.176 | 2.735** | supported |

| H1e | EMV → ATT | 0.240 | 4.235** | supported |

| H1f | EPV → ATT | 0.034 | 0.647 | not supported |

| H1g | ENC → PUI | 0.229 | 4.029** | supported |

| H2 | ATT → PUI | 0.962 | 7.322** | supported |

| H3 | ATT → PBR | 0.798 | 7.252** | supported |

| H4 | ATT → OBR | 0.555 | 6.104** | supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).