1. Introduction

Endometriosis is considered as common public health problem, affecting 10-12% of women at different age whose prevalence increases to 20–50% in infertile women [

1]. It is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity, and can result in infertility and pelvic pain. These symptoms can significantly impact patient’s quality of life [

2].

The predominant symptom is recurrent pelvic pain, which can be particularly acute during menstruation. The lesions are sensitive to estrogen and thus undergo proliferation, hemorrhage and the formation of fibrous scarring with each menstrual cycle. In addition to menstruation, patients may experience discomfort during sexual intercourse (dyspareunia) or when urinating or defecating [

3]. Endometriosis has been shown to significantly impact physical and psychological well-being, often resulting in adverse effects such as depression, anxiety and impaired social relationships [

3,

4]. As asserted by Della Corte et al. (2020) [

4], endometriosis has a detrimental effect on patients’ sex lives and social relationships.

As an estrogen dependent disorder, endometriosis causes a systemic immune inflammatory syndrome that becomes the origin of energy imbalance, mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolomics disorder, peripheral and local cells apoptosis in combination with epigenetic profile changes [

5,

6].

It has been reported that women with severe endometriosis suffer from elevated oxidative stress and elevated free circulating DNA fragments in the bloodstream [

7].

Our previous study [

1] reported high level of free circulating DNA (fcDNA) as a consequence of apoptosis and differential methylation changes of a group of genes in patients with endometriosis compared to the control group.

In rare cases, the disease may be completely asymptomatic. In such cases, the condition is usually diagnosed when the patient seeks treatment for infertility. The scientific explanation for this association is yet to be elucidated.

Today endometriosis is primarily diagnosed through laparoscopy, with subsequent confirmation derived from analyzing the obtained lesions. For cases classified as mild to moderate (stages I and II), the therapeutic approach is predominantly medical. For cases classified as severe (stages III and IV), the therapeutic approach involves surgical intervention or, alternatively, the initiation of hormone therapy [

8].

As for other noninvasive biomarkers for endometriosis diagnosis, CA 125 is often elevated in advanced endometriosis, but the low sensitivity of this diagnostic assay limits its usefulness for detecting minimal and mild stages of endometriosis (stage I and II)

Recently many studies have focused on the identification of reliable biomarkers for early endometriosis diagnostic such as immunologic, as well as genetic and biochemical markers, including specific cytokines, microRNAs, lncRNAs, circulating and mitochondrial nucleic acids, along with some hormones, glycoproteins and signaling molecules [

9,

10,

11]

In 2025 we proposed novel noninvasive biomarkers for endometriosis using quantification of free circulating DNA and reanalyzing the differential methylation profile of specific genes involved in endometriosis pathophysiology. We observed nearly 4 times as much fcDNA in the serum and differential methylation profile of nine genes of patients with endometriosis compared to the control group [

1].

As a response to the systemic chronic inflammatory condition, common in endometriosis with high levels of fcDNA, the natural physiological endonuclease DNase I cleaves excess DNA fragments, facilitating their elimination from the bloodstream, liver, and urine to minimize the negative immunopathology impact of abnormal high level of free circulating DNA. The shelf-life of human DNase in peripheral blood was estimated to be around 30 minutes, due to its rapid degradation by proteases, renal and/or hepatic clearance. The in vitro half-life is estimated to be between three and six hours. At physiological level, DNase I plays a pivotal role in the process of clearing of free DNA generated by excessive cell death in endometriosis.

In clinical medicine, the human recombinant form of deoxyribonuclease I (Pulmozyme®) is the most common mucolytic agent used for long-term daily treatment of cystic fibrosis. The use of DNase I for patients undergoing IVF/ICSI with repeated implantation failure and high circulating fc DNA showed that a daily injection of 2500 IU DNase I for a month reduced fcDNA by 40% with improvement of embryo implantation [

12].

DNase I is an enzyme that catalyses the breakdown of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) into nucleotides or polynucleotides.

DNase I has been shown to facilitate the elimination of extracellular DNA, a process that is particularly pronounced during inflammatory responses.

To date, no studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of DNase I in alleviating the pain and inflammation associated with moderate to severe endometriosis. The direct connection between DNase and endometriosis remains an active area of research.

Managing excess fcDNA and inflammation could have implications for understanding the chronic inflammatory nature of endometriosis and designing potential therapeutic approaches.

The objective of the present preliminary prospective study was to administer a synthetic endonuclease to women diagnosed with endometriosis, as confirmed by bio-clinical ultrasound and laparoscopy, at any stage of the disease, in order to evaluate the effect of this treatment on CfDNA reduction and differential methylation of a group of genes involved in endometriosis [

1].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Patients

From infertile women’s consulting for infertility, sixteen patients with endometriosis were enrolled for the study. The patients with primary infertility and algic symptoms, with laparoscopically proven endometriosis, agreed to receive exogenous DNase I therapy for one month. The average age of the patients was 34, years and they all suffered from chronic abdominal-pelvic pain and excessive bleeding during their menstrual cycles.

The patients had at least stage II pelvic endometriosis or higher (stage III and IV); schematically, stage II is localized to the peritoneum and/or utero-sacral ligaments; utero-sacral ligaments or fallopian tubes; stage III involves the ovaries and stage IV the digestive tract, particularly the recto-vaginal septum. They had no other pathology or current medical treatment for more than three months and were not required to take any painkillers during their DNase treatment.

Patients were tested using an electrical neural stimulation ENS numerical scale to evaluate pain intensity (0 to 10) where 0 means no pain, and 10 maximal and unsupportable pain and a HRQoL (Health-Related Quality of Life) questionnaire to assess quality of life (1 to 10) where 1 means the best quality of life and 10 the worst.

Each endometriosis patient was given a 2,500 IU ampoule of Pulmozyme (synthetic DNase, Roche Laboratories, Switzerland) subcutaneously every 2 days for one month. Women taking part in the study were given information about the treatment and follow-up.

Ten ml of peripheral blood were sampled from each patient in an EDTA tube before and after treatment. The samples were labelled and immediately centrifuged. The obtained serum was frozen at -80 °C and stored for free DNA quantification and gene methylation profiling assessment.

2.2. Cf-DNA Extraction

Nucleic acids were extracted from 1 mL of frozen–thawed serum using a Qiagen QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit from Qiagen, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France, closely following the Handbook extraction protocol (10/2019). Briefly, 40 µL of proteinase K (concentration 600 mAU/mL) was added to the 1 mL of thawed serum. Then, 1 mL of lysis buffer containing 1.0 µg of carrier RNA (Qiagen ACL buffer) was added to the mix of the serum and proteinase K and vortexed for 30 s before incubation at 56 ◦C for 10 min. Then, 840 µL of ACB buffer was added to the lysate, mixed thoroughly by pulse-vortexing for 15–30 s, and incubated for 5 min on ice. The lysate–ACB buffer solution was carefully applied to the QiaAmp Mini column from Qiagen, Sant Quentin Fallavier, France to be drawn completely. After that, the column was washed and drawn successively with ACW1 and ACW2 buffers and ethanol (96–100%). Then, the QIAamp mini-column was placed in a clean 2 mL collection tube and centrifuged at full speed (14,000 rpm) for 3 min, transferred to a new collection tube, and incubated for 10 min at 56◦ to be dried. Finally, cell-free DNA (Cf-DNA) was eluted twice with 25 µL of TE buffer (Tris/EDTA 1 mM/0.1 mM) using 1 min of full-speed centrifugation (14,000 rpm).

2.3. Cf-DNA Quantification via Reverse Real-Time PCR

Rpp30 (NM_006413) is commonly chosen to measure cfDNA levels in serum due to its role as a stable, single-copy housekeeping gene. As a robust internal control, Rpp30 ensures accurate and reproducible Cf-DNA measurements. Rpp30 DNA (NM_006413) was quantified using qPCR genes from human serum samples. This highly conserved endoribonuclease is present in all living cells in the body. Triplicates of 5 µL of Cf-DNA were added to 20 µL of PCR Light Cycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Cat. no 04707516001) with 2.5 mM of MgCl2 and 0.5 mM of each forward and reverse RNase P primers (primer sequences: RNP30 Forward—AGATTTGGACCTGCGAGCG; RNP30 Reverse—GAAGCCGGGGCAACTCAC). A PCR product of 86 base pair regions spanning exon 1 and intron 2 of the Homo sapiens ribonuclease P/MRP subunit p30 gene (NM_006413 and ENST00000371703.7) was obtained. The amplification was performed on a Light Cycler 480 II (Roche) as follows: 35 cycles of 95 ◦C for 10 s, 59 ◦C for 20 s, and 72 ◦C for 15 s, followed by an elongation step of 5 min at 72 ◦C. Positive DNA controls at various concentrations and non-template controls were added to each run. Cycle threshold values were reported against a standard concentration curve, and Cf-DNA concentration was reported as the mean value of the triplicate

2.4. Cf-DNA Methylation Analysis and Sequencing

Bisulfite DNA treatment was performed using an EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) following manufacturer recommendations. According to the initial concentrations, 35 µL of DNA sample was used for the reaction. At the end of the treatment, DNA was eluted with 25 µL of elution buffer and then diluted using 10 µL of H2O. Gene-specific PCR reactions were performed using Taq’Ozyme HS Mix (Ozyme, Saint-Cyr-l’École, France), 1 µL of bisulfite-treated DNA, and the final primers, each at a concentration of 0.4 µM, in a 20 µL final reaction volume using a C-100 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The cycling conditions were 95 ◦C/1 min; (95 ◦C/15 s–58 ◦C/15 s–72 ◦C/30 s) × 34; and 72 ◦C/5 s. All amplicon sizes were checked and validated via electrophoresis before sequencing, and sequencing was performed in the paired-end mode (2 × 150 bp) on the NextSeq Illumina Platform following the manufacturer’s protocol (BioProject record (NCBI): 1063938).

2.5. Statistical Analysis of the Rpp30 Quantification

Statistical analysis was performed with R software v.1. We first compared the quantification of RPP30 of the patient group with the control group by the ANOVA test. 2.4. Bioinformatic Data Analysis of the Methylation A post-sequencing quality check was performed with the “FastQC” software (version 0.11.8), and sequence cleaning and paired-end read merging were performed using the “fastp” software (version 0.21.0). Then, a post-cleaning/merging quality check was performed with the “FastQC” software. The targeted gene sequences were extracted and sorted using custom “blast” software v.1. Finally, the frequency of C nucleotides versus the total number of C and T for each targeted position after bisulfite treatment was used to measure the rate of DNA methylation. Methylated and unmethylated read counts were summed to calculate the total coverage at each CpG site, filtering out sites with fewer than 8 reads per sample or with constant methylation (fully methylated/unmethylated). Library sizes were normalized using the average total read count. A chi-square test of homogeneity was applied to each targeted sequence to assess differences in C and T nucleotide distributions between the control and endometriosis groups (alpha = 0.05). The analyses used R (4.3.1) and EdgeR (3.42).

We targeted the changes of the differential methylation Targets CpG sites of 9 genes selected by ENDOLIFE: CALD1, RRP1, FN1, DIP2C, RMI2, TDRD5, USP1, HDAC1, DNMT1 before and after treatment

3. Results

3.1. Data from Clinical Questionnaire for Quality of Life

Fifteen of the 16 participants reported a significant reduction in pain, as well as an improvement in their ability to assume professional activity and less difficult sexuality

Table 1.

Pain and Quality of life evaluation in 16 endometriosis patients before and after treatment.

Table 1.

Pain and Quality of life evaluation in 16 endometriosis patients before and after treatment.

| Patient number |

AGE |

Endometriosis stage |

ENS (1 to 10)

|

HRQoL (1 to 10)

|

| Before tt |

After tt |

Before tt |

After tt |

| 1 |

31 |

3 |

5 |

5 |

7,5 |

4 |

| 2 |

28 |

3-4 |

3 |

2 |

7,5 |

6 |

| 3 |

39 |

4 |

6 |

4 |

9 |

5 |

| 4 |

29 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

4 |

| 5 |

36 |

4 |

7 |

|

6 |

3 |

| 6 |

36 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

9 |

5 |

| 7 |

39 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

3 |

| 8 |

30 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

| 9 |

37 |

2 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

| 10 |

41 |

4 |

9,5 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

| 11 |

35 |

4 |

9 |

3 |

7 |

3 |

| 12 |

41 |

2 |

8 |

|

1 |

1 |

| 13 |

29 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

10 |

6 |

| 14 |

28 |

2 |

9,5 |

8 |

3 |

3 |

| 15 |

34 |

4 |

9,7 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

| 16 |

31 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

9,5 |

6 |

HRQoL (Health Related Quality of Life) is a multi-dimensional concept, commonly used to examine the impact of health status on quality of life. It is measured by four core questions that asked about general health status and number of unhealthy days in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BFRSS)

3.2. Biological Data

3.2.1. Rpp30 QPCR Absolute Quantification

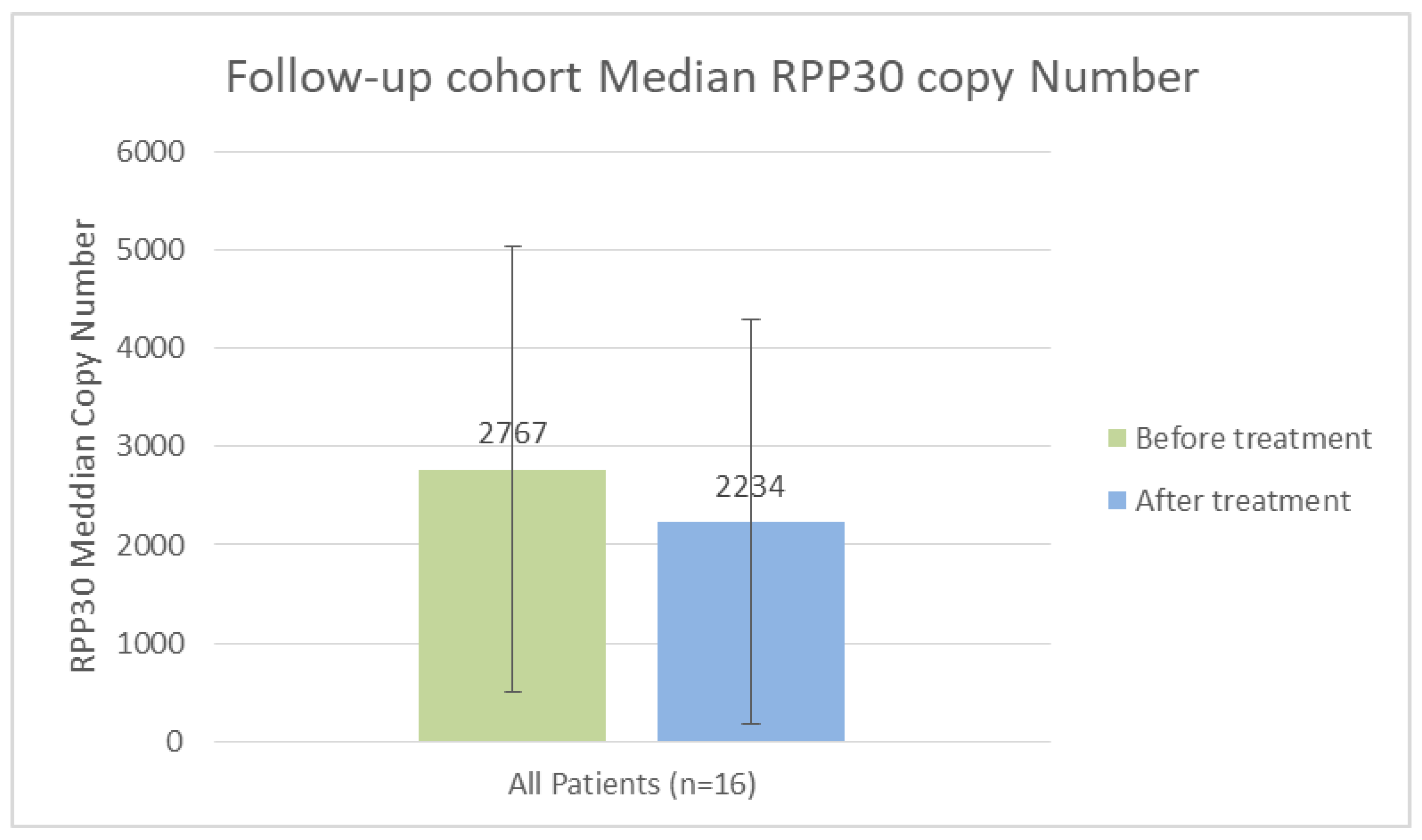

To quantify the absolute amount of the Hs_Rpp30 gene in a 1-mL serum sample, we calculated a standard curve using a plasmid containing a portion of the Rpp30 gene, a single-copy gene present in the human genome. The Hs_Rpp30-positive control (IDT, ref. 10006626) is calibrated at a concentration of 200,000 copies/µL in Tris/EDTA at a pH of 8.0. The absolute quantification and mean absolute quantification from the 16 endometriosis patients before and after DNase I Therapy. (see

Figures 1)

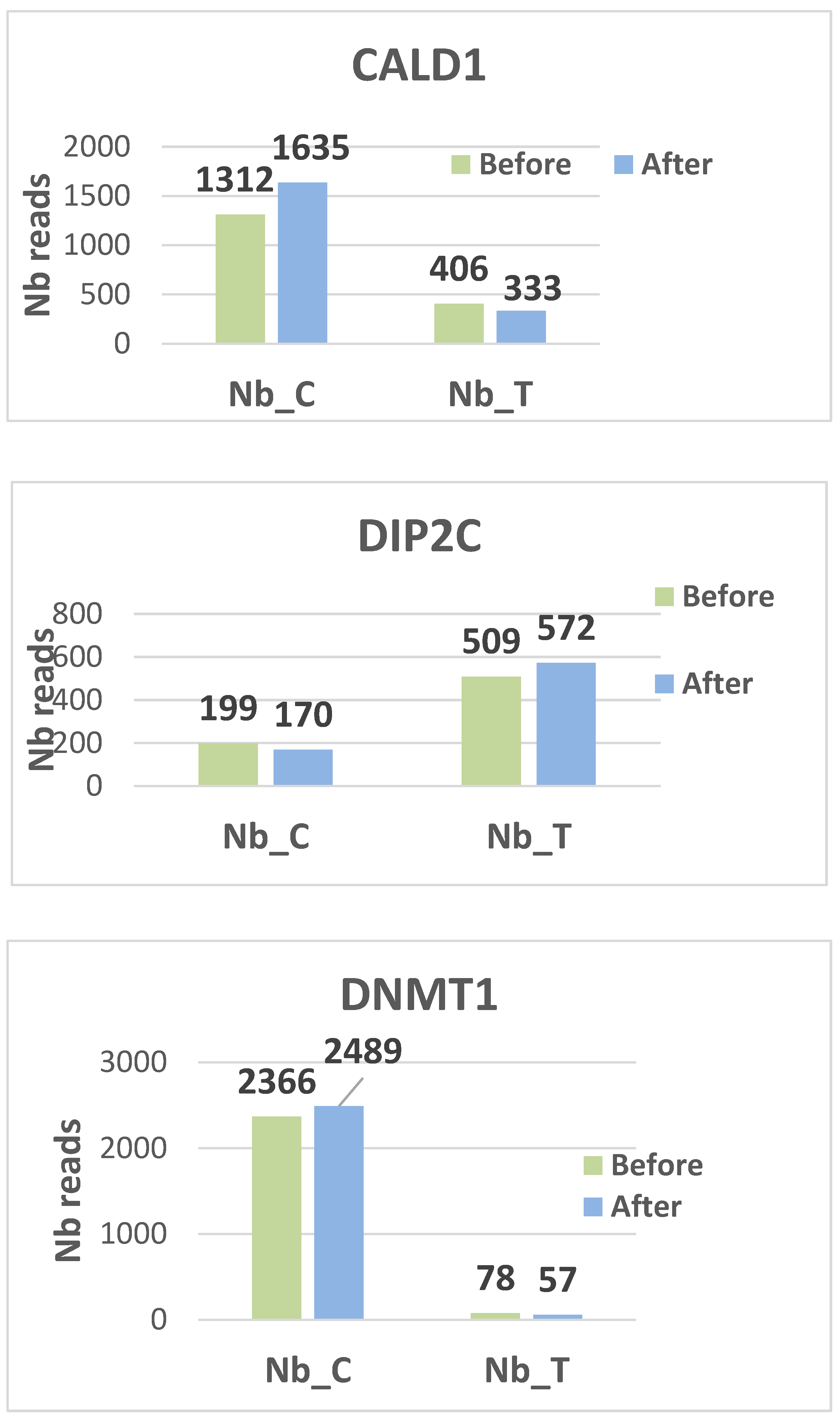

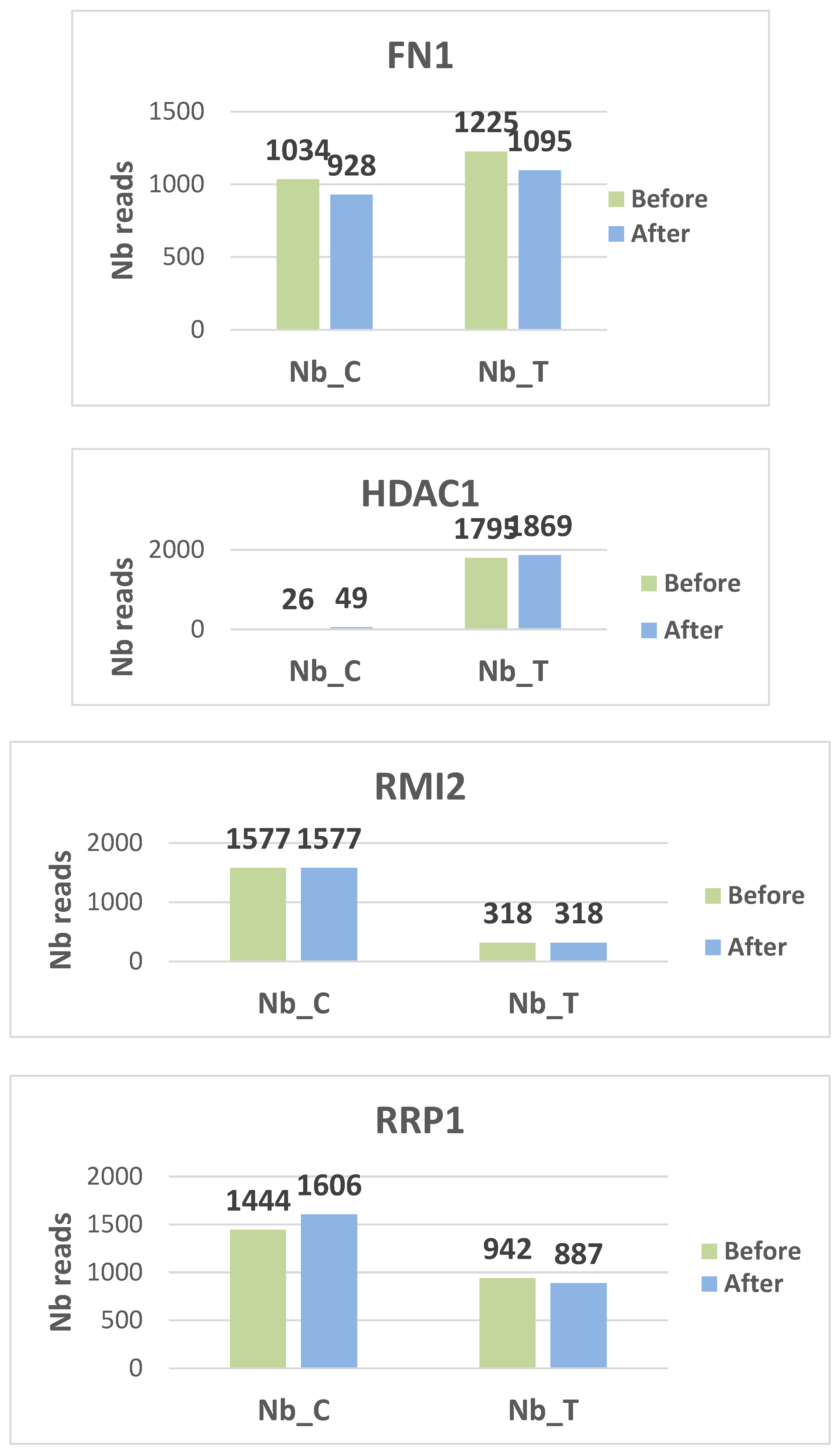

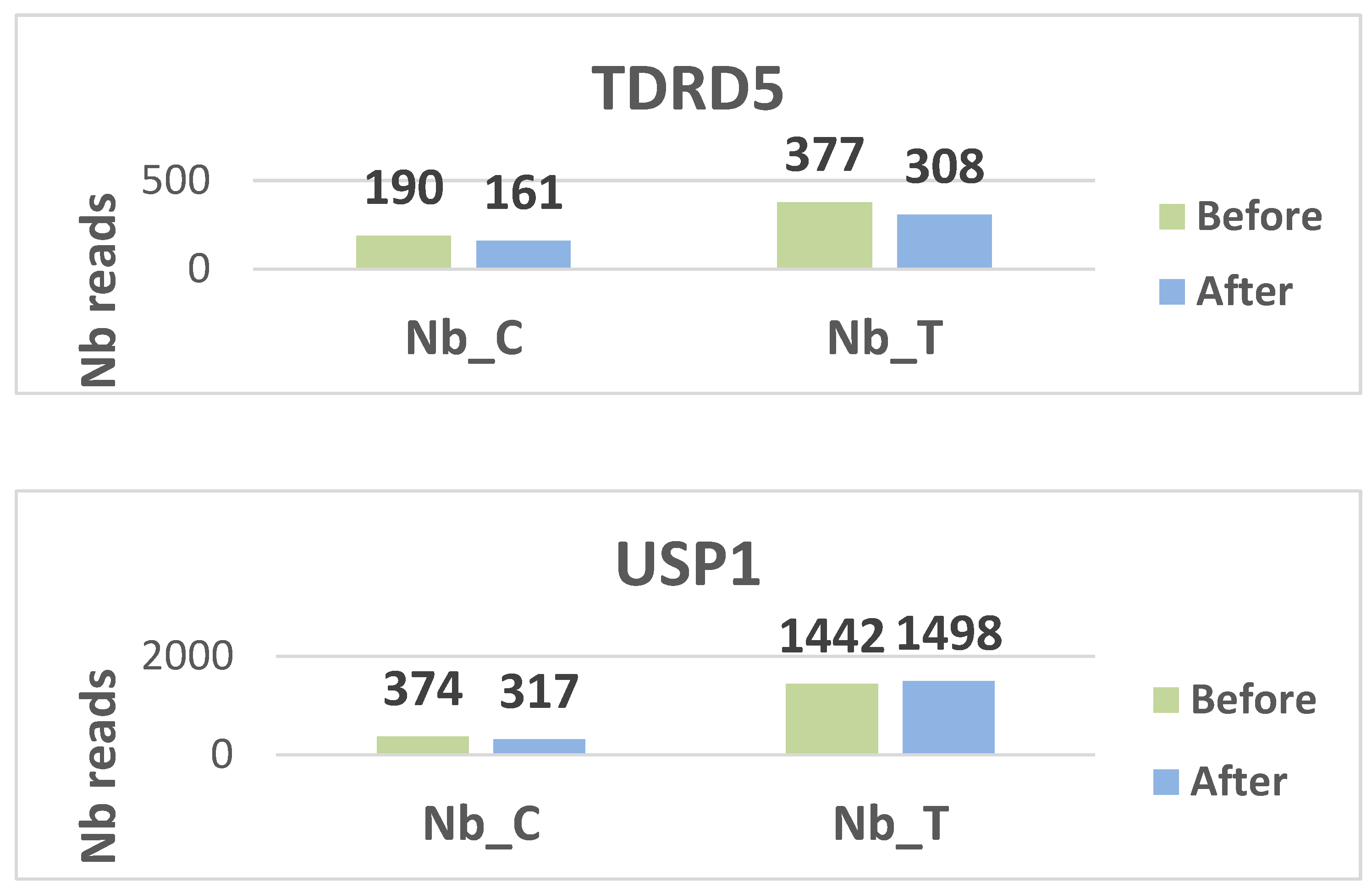

3.2.2. Targeted Genes and Differential Methylation

After gene depletion and selection, we analyzed the differential methylation status of nine targeted genes (CALD1, RRP1, FN1, DIP2C, RMI2, TDRD5, USP1, HDAC1, and DNMT1) before and after treatment (see the details in

Table 2)

Differential methylation profiling

For each targeted genes we used a chi square test of homogeneity as our primary choice of statistical tool. This test resulting in a p value which will define for each targeted sequences if the distribution of C and T nucleotide is the same when comparing the control group and the endometriosis group. P value type 1 error alpha is set to 0.05.

The data reported that 6 genes where the methylation is significantly different for CALD1, DIP2C, DNMT1, HDAC1, RRP1 and USP1. The green color of the p values indicates that there is an HYPOMETHYLATION and the red color indicates an HYPERMETHYLATION in the after-treatment group compared to the before treatment group.

Table 2.

p values of the chi square test of homogeneity.

Table 2.

p values of the chi square test of homogeneity.

| Target |

Khi2.pval |

| CALD1 |

4.76E-07 |

| DIP2C |

0.02707 |

| DNMT1 |

0.047 |

| FN1 |

0.9722 |

| HDAC1 |

0.01928 |

| RMI2 |

1 |

| RRP1 |

0.005371 |

| TDRD5 |

0.8327 |

| USP1 |

0.0183 |

Hyper methylation of genes stops transcriptional capacity. Hypo methylation, on the other hand, operates in the opposite way.

Histograms display the distribution of methylated (C) and unmethylated (T) read counts for all nine targeted CpG loci (CALD1, RRP1, FN1, DIP2C, RMI2, TDRD5, USP1, HDAC1, and DNMT1) across the analyzed samples. Each panel illustrates the relative proportions of C and T nucleotides obtained after bisulfite sequencing, providing a visual overview of methylation patterns for each gene target. The histograms summarize the variability in read composition among participants and allow qualitative comparison of methylation profiles between the examined loci. (see

figures 2 for the different histograms)

Two genes, DIP2C and USP1, are hypo methylated. DIP2C (Disco Interacting Protein 2 Homolog C) is a gene that encodes a protein. The protein interacts with the disco transcription factor and is expressed in the nervous system. USP1 is a negative regulator of DNA damage repair. It is also involved in PCNA-mediated translational synthesis (TLS) by deubiquitinating mon oubiquitinated PCNA. The hypo methylation status of these two genes gives them a major expression potential. They are expressed equivalently before and after treatment.

On the contrary, CALD1, DNMT1, HDAC1 and RRP1 are hyper methylated, blocking any possibility of transcription.

4. Discussion

As a systemic immune inflammatory syndrome, endometriosis causes mainly pelvic pain, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, adhesions with a high risk of infertility potential declining and epigenetic status changes in some genes.

For endometriosis symptom therapy there is an increase in clinical management options and the range of drugs available to reduce painful systemic immune inflammatory symptoms, improve social life conditions and fertility potential reservation [

13,

14,

15].

A correlation has been demonstrated between endometriosis and elevated levels of free DNA in the blood [

1,

16]. CfDNA is a complex biomarker that can be traced back to multiple sources, included cellular apoptosis, necrosis and active secretion, making it a valuable tool in noninvasive diagnostics such as oxidative stress, for example.

For the best of our knowledge, this preliminary study is the first one combining diagnosis and treatment of women suffering from endometriosis.

In a normal situation, an endonuclease ensures the elimination of excess free DNA. In endometriosis, this mechanism is unfortunately insufficient to ensure the removal of all of the cfDNA, which is significantly increased. Logically, an exogenous supply of synthetic DNase I has become necessary to help the body promote the faster excretion of necrotic and apoptotic DNA fragments. This reduces inflammation and its harmful effects, helping to alleviate pain and restore a better quality of life.

In our preliminary study, the results were very unexpected, with all but one patient experiencing an alleviation of pain and an improvement of quality of life.

However, when we compared our clinical results with the free DNA levels of all patients before and after treatment, we found no significant difference, despite the fact that the treated group had lower average levels after treatment. We can suggest several possible explanations. The first is a dose effect; given the product’s very short half-life, it is likely that 2,500 IU administered every other day is insufficient. A daily, or even twice-daily, dose would be more appropriate. For reasons of treatment compliance, we should consider designing a long-acting DNase.

A second possible explanation is that some patients may have had a viral or other infection during treatment that could have increased free DNA levels. Therefore, in a future controlled study, the treatment time should be shortened to 15 days to confirm a significant and objective effect on cfDNA levels.

A final possible explanation is that some patients with very high levels of cfDNA after treatment may have forgotten to take certain injections. This issue could be avoided by formulating DNase differently, for example as a delayed-release formulation.

Regardless of the level of free cfDNA, it is interesting to note that a minimal concentration of DNase substantially reduced pain in all but one patient. We have no explanation for these two contrasting effects. However, DNase may have a dose-dependent effect, resulting in apparent resistance to treatment due to a particular genomic profile.

The difficulty of this work lies in the treatment time, during which even the slightest viral or bacterial infection can cause an excessive increase in free DNA levels. This is why we believe that treatment could be more intense and shorter, or delivered in a long-acting form.

The rise in cfDNA levels should enable the progression of endometriosis to be monitored and, if necessary, indicate when treatment should be resumed.

The second difficulty will be to introduce a placebo arm, as the patients suffering from this condition are keen to receive symptomatic treatment. This will need to be done in our next study.

At the genetic level, a specific signature of necroptosis-related genes was reported by Wang et al. 2025 [

14], and a specific model analysis reported seven specific genes [

17] as diagnostic markers of endometriosis. Endometrial single-cell ribonucleic acid sequencing (scRNA-seq) [

18] and piwi RNA saliva-reverse transcription and sequencing [

19] were proposed as diagnostic signature of endometriosis

In our preliminary study, the two hypo methylated genes in the endometriosis group were DIP2C and USP1

Both, the USP1 and DIP2C genes can influence the ubiquitination state of histones, such as H2A or H2B. This is critical for chromatin remodeling, which can either facilitate or inhibit access of DNA methyl transferases (DNMTs) or other methyl transferases. In endometriosis, inflammatory processes may be aberrantly activated due to the over activity of hypo methylated genes. Four genes CALD1, DNMT1, HDAC1 and RRP1 are hyper methylated.

5. Conclusions

At our knowledge this is the unique study demonstrating the impact of DNase treatment on free circulating DNA levels and the changes between the differential methylation genomic profile of patients before and after treatment. The results are encouraging because of the clearly demonstrated clinical effect of the treatment, especially the patients’ comfort, likely to be related to an alleviation of the local inflammation status and pain, conditioned by excess cfDNA. These findings are even more encouraging given the relatively small number of patients enrolled in this study. Further research, including the modifications suggested in the discussion is warranted.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mohammed VI University of Health Sciences (Approval No. [CE/UM6SS/25/24]), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benkhalifa, M., Menoud, P. A., Piquemal, D., Hazout, J. Y., Mahjoub, S., Zarquaoui, M., Louanjli, N., Cabry, R., and Hazout, A., “Quantification of Free Circulating DNA and Differential Methylation Profiling of Selected Genes as Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Endometriosis Diagnosis,” Biomolecules, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2025, p. 69. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V. L., Barra, F., Chiofalo, B., Platania, A., Di Guardo, F., Conway, F., Di Angelo Antonio, S., and Lin, L.-T., “An Overview on the Relationship between Endometriosis and Infertility: The Impact on Sexuality and Psychological Well-Being,” Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2020, pp. 93–97. [CrossRef]

- McPeak, A. E., Allaire, C., Williams, C., Albert, A., Lisonkova, S., and Yong, P. J., “Pain Catastrophizing and Pain Health-Related Quality-of-Life in Endometriosis,” The Clinical Journal of Pain, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2018, pp. 349–356. [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, L., Di Filippo, C., Gabrielli, O., Reppuccia, S., La Rosa, V. L., Ragusa, R., Fichera, M., Commodari, E., Bifulco, G., and Giampaolino, P., “The Burden of Endometriosis on Women’s Lifespan: A Narrative Overview on Quality of Life and Psychosocial Wellbeing,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 17, No. 13, 2020, p. 4683. [CrossRef]

- Bedrick, B. S., Courtright, L., Zhang, J., Snow, M., Amendola, I. L. S., Nylander, E., Cayton-Vaught, K., Segars, J., and Singh, B., “A Systematic Review of Epigenetics of Endometriosis,” F&S Reviews, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2024, p. 100070. [CrossRef]

- Mariadas, H., Chen, J.-H., and Chen, K.-H., “The Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Endometriosis: From Basic Pathophysiology to Clinical Implications,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 6, 2025, p. 2458. [CrossRef]

- Clower, L., Fleshman, T., Geldenhuys, W. J., and Santanam, N., “Targeting Oxidative Stress Involved in Endometriosis and Its Pain,” Biomolecules, Vol. 12, No. 8, 2022, p. 1055. [CrossRef]

- Rosendo-Chalma, P., Díaz-Landy, E. N., Antonio-Véjar, V., Ortiz Tejedor, J. G., Reytor-González, C., Simancas-Racines, D., and Bigoni-Ordóñez, G. D., “Endometriosis: Challenges in Clinical Molecular Diagnostics and Treatment,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Vol. 26, No. 9, 2025, p. 3979. [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Moar, K.; Arora, T.K.; Maurya, P.K. Biomarkers of Endometriosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 549, 117563. [CrossRef]

- Ravagnini, G.; Coadă, C.A.; Mantovani, G.; De Leo, A.; de Biase, D.; Costantino, A.; Gorini, F.; Dondi, G.; Di Costanzo, S.; Mezzapesa, F.; Gomar, M.; Tallini, G.; Angelini, S.; Astolfi, A.; Strigari, L.; De Iaco, P.; Perrone, A.M. MicroRNA Profiling Reveals Potential Biomarkers for the Early Transformation of Endometriosis towards Endometriosis-Correlated Ovarian Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 25, 102367. [CrossRef]

- Nadifi, C.; Hilali, C.; Mbaye, M.M.; Zarqaoui, M.; Bouanani, N.; Halabi, M.K.; Louanjli, N.; Benkhalifa, M.; Lahlou, F.A. Endometriosis Physiopathology and Biomarkers: A Review of Immunological, Genetic, Hormonal and Metabolic Mechanisms. Reprod. Dev. Med. 2025, accepted.

- Hazout, A., Cell-free dna as a therapeutic target for female infertility and diagnostic markerJ. PCT Application N° PCT/IB2013/056321 ;August 2013.

- Saunders, P. T. K., and Horne, A. W., “Endometriosis: Etiology, Pathobiology, and Therapeutic Prospects,” Cell, Vol. 184, No. 11, 2021, pp. 2807–2824. [CrossRef]

- Sadłocha, M., Toczek, J., Major, K., Staniczek, J., and Stojko, R., “Endometriosis: Molecular Pathophysiology and Recent Treatment Strategies-Comprehensive Literature Review,” Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), Vol. 17, No. 7, 2024, p. 827. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Huang, Z., Chen, Y., Tian, H., Chai, P., Shen, Y., Yao, Y., Xu, S., Ge, S., and Jia, R., “Lactate and Lactylation in Cancer,” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2025, p. 38. [CrossRef]

- Zachariah, R., Schmid, S., Radpour, R., Buerki, N., Fan, AX., Hahn, S., Holzgreve, W., Zhong, X.Y., Circulating cell-free DNA as a potential biomarker for minimal and mild endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online,18(3):407-11(2009.

- Niharika, Asthana, S., Narayan Yadav, H., Sharma, N., and Kumar Singh, V., “A Compendium of Methods: Searching Allele Specific Expression via RNA Sequencing,” Gene, Vol. 936, 2025, p. 149102. [CrossRef]

- González-Martínez, S., Pérez-Mies, B., Cortés, J., and Palacios, J., “Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Endometrial Cancer: Exploring the Epithelial Cells and the Microenvironment Landscape,” Frontiers in Immunology, Vol. 15, 2024, p. 1425212. [CrossRef]

- Haase, A. D., Ketting, R. F., Lai, E. C., van Rij, R. P., Siomi, M., Svoboda, P., van Wolfswinkel, J. C., and Wu, P.-H., “PIWI-Interacting RNAs: Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How,” The EMBO Journal, Vol. 43, No. 22, 2024, pp. 5335–5339. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).