Submitted:

05 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

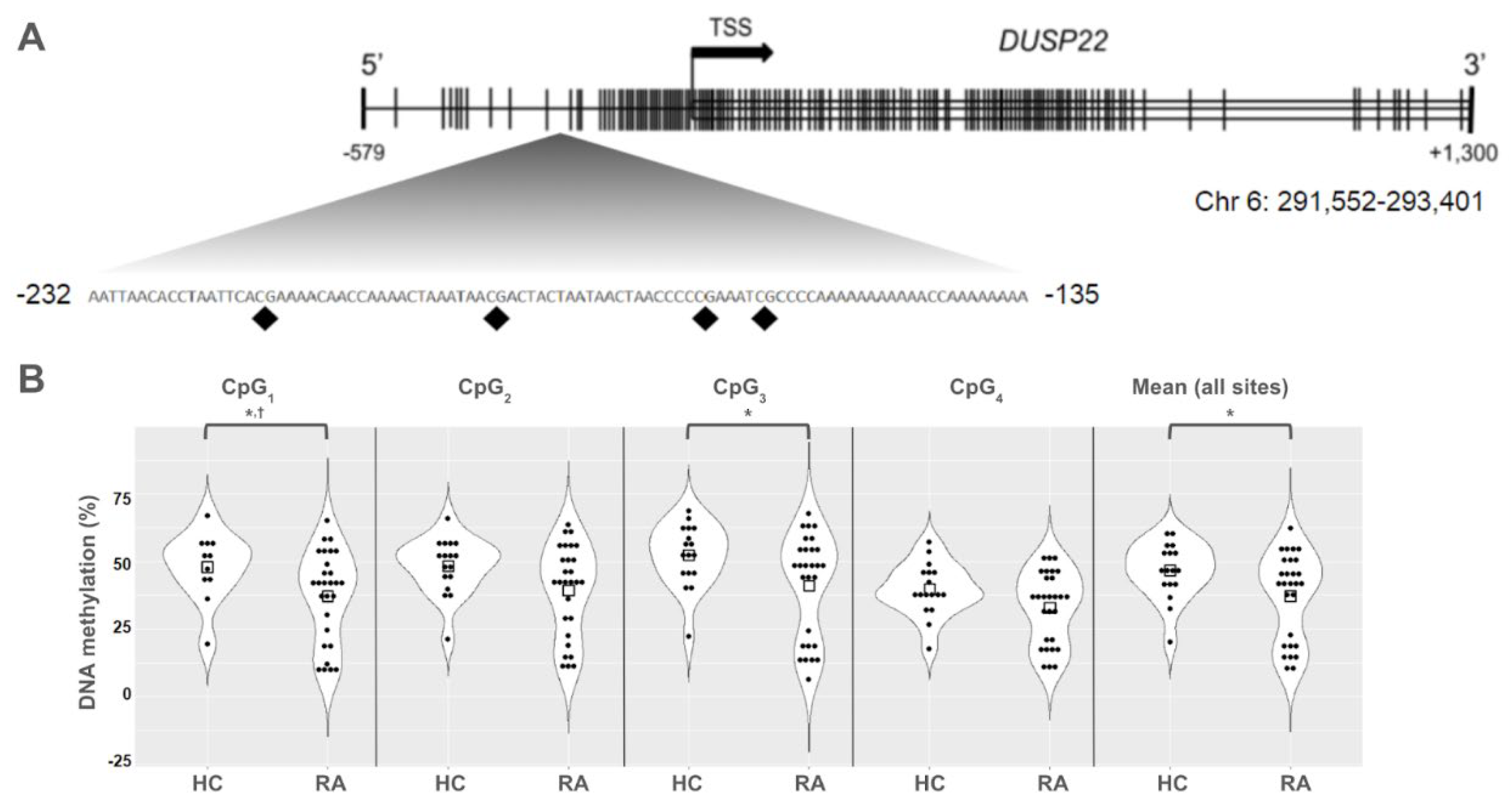

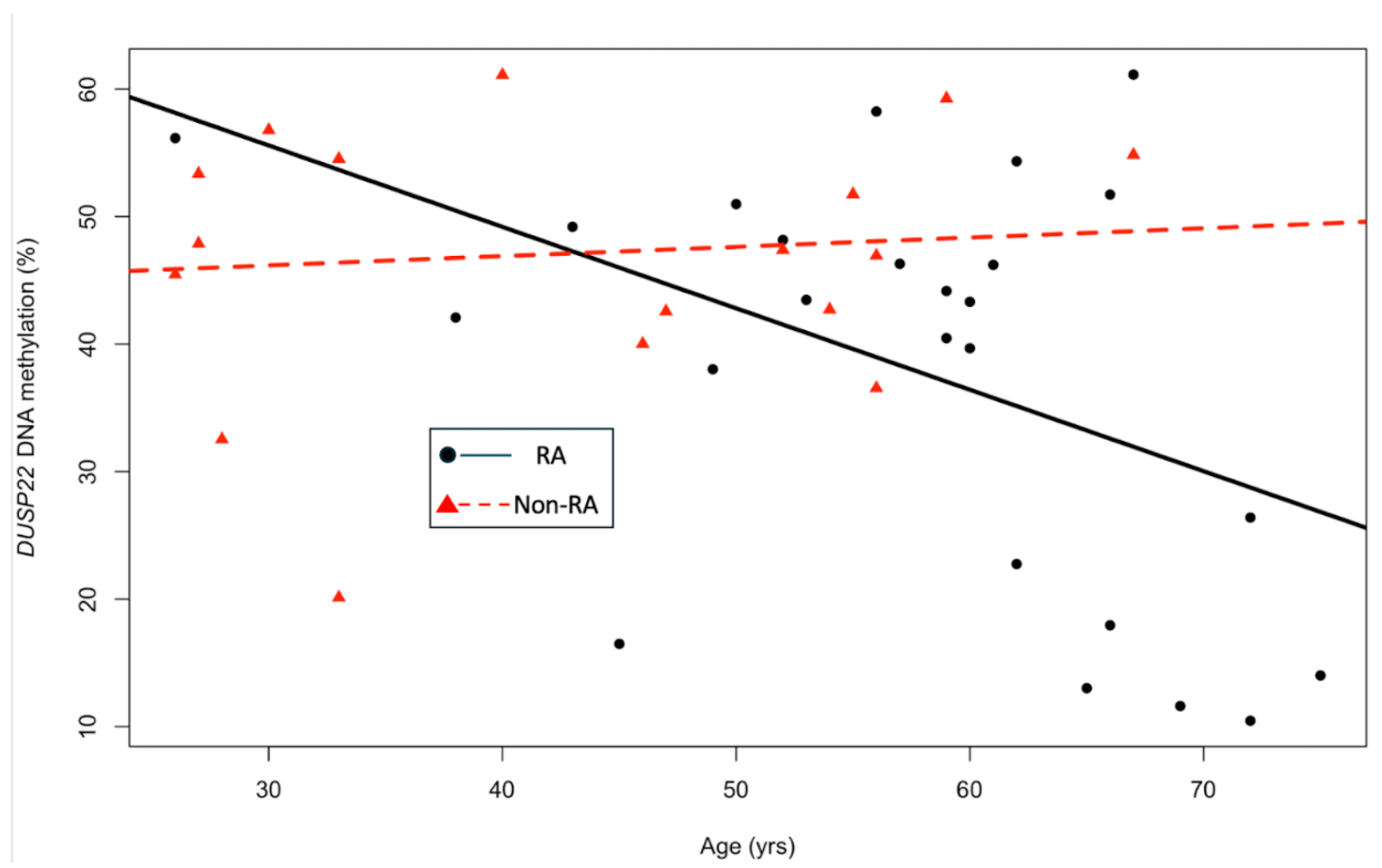

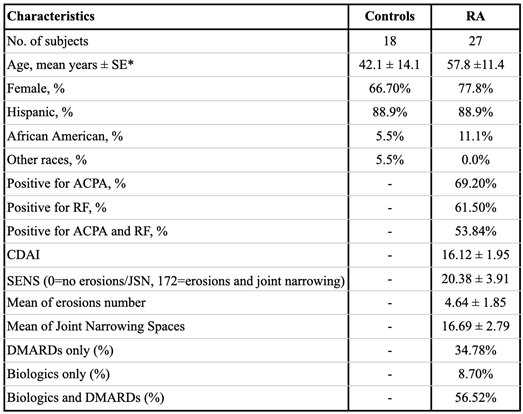

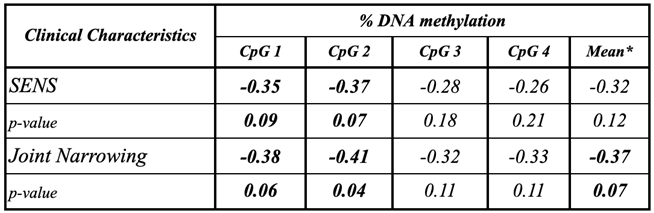

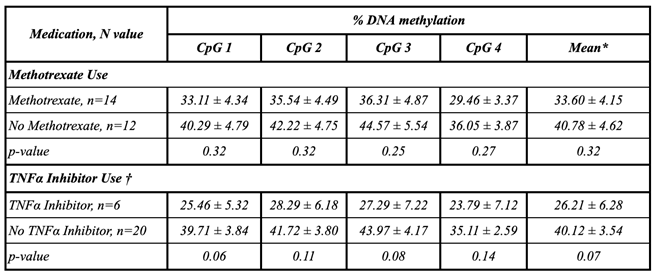

Background/Objective: While several advances have been made in the last decade, reliable biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and especially for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have yet to be identified. In previous studies, DUSP22 DNA methylation changes were found to be associated with RA and erosive disease. We conducted a pilot study to investigate plasma cell-free DNA (cfDNA) methylation in DUSP22 in a cohort of RA patients and healthy controls. We also investigate DUSP22 DNA methylation associations with RA clinical characteristics and treatment. Methods: DNA was isolated from plasma from twenty-seven RA patients who satisfied the ACR criteria, and eighteen healthy controls. DUSP22 DNA methylation was determined by pyrosequencing. Statistical analysis identified group differences and associations with RA clinical measures. Results: RA patients had lower mean promoter cfDNA DUSP22 DNA methylation when compared to controls (36.47±16.17% vs. 47.05±10.28%, p=0.025). Hypomethylation of one CpG site in this region was also associated with increased joint space narrowing (ρCpG2=-0.41, p=0.04). Conclusion: Our pilot study is the first to show that cfDNA methylation might be an important biomarker in RA. Our hypothesis-generating findings suggest that hypomethylation of DUSP22 in cfDNA is associated with RA, and if replicated in future studies, our results point to the potential of cfDNA methylation to be a non-invasive biomarker for this disease.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Clinical Measures

2.3. DNA Extraction and Methylation Analysis of DUSP22

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mori, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Yoshida, H.; Asakawa, M.; Kawasumi, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Morioka, H.; Chiba, K.; Toyama, Y.; Yoshimura, A. IL-1β and TNFα -initiated IL-6-STAT3 pathway is critical in mediating inflammatory cytokines and RANKL expression in inflammatory arthritis. Int. Immunol. 2011, 23, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symmons, D.P. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: determinants of onset, persistence and outcome. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2002, 16, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.; Schmidt, E.M.; Cribbs, A.P.; Penn, H.; Amjadi, P.; Syed, K.; Read, J.E.; Green, P.; Gregory, B.; Brennan, F.M. A novel upstream enhancer of FOXP3, sensitive to methylation-induced silencing, exhibits dysregulated methylation in rheumatoid arthritis Treg cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 2968–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossop, J.R.; Emes, R.D.; Nixon, N.B.; E Haworth, K.; Packham, J.C.; Dawes, P.T.; A Fryer, A.; Mattey, D.L.; E Farrell, W. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling in rheumatoid arthritis identifies disease-associated methylation changes that are distinct to individual T- and B-lymphocyte populations. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossop, J.R.; Emes, R.D.; Nixon, N.B.; Packham, J.C.; A Fryer, A.; Mattey, D.L.; E Farrell, W. Genome-wide profiling in treatment-naive early rheumatoid arthritis reveals DNA methylome changes in T and B lymphocytes. Epigenomics 2015, 8, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Almgren, M.; Sjöholm, L.K.; Hensvold, A.H.; Ringh, M.V.; Tryggvadottir, R.; Kere, J.; Scheynius, A.; Acevedo, N.; Reinius, L.; et al. High-specificity bioinformatics framework for epigenomic profiling of discordant twins reveals specific and shared markers for ACPA and ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossop, J.R.; Nixon, N.B.; Emes, R.D.; Sim, J.; Packham, J.C.; Mattey, D.L.; E Farrell, W.; A Fryer, A. DNA methylation at diagnosis is associated with response to disease-modifying drugs in early rheumatoid arthritis. Epigenomics 2016, 9, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Too, C.L.; Uebe, S.; Jagodic, M.; Kockum, I.; Murad, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Alfredsson, L.; et al. DNA methylation mediates genotype and smoking interaction in the development of anti-citrullinated peptide antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, A.; Rhead, B.; Holingue, C.; Shao, X.; Quach, H.L.; Quach, D.; Sinclair, E.; Graf, J.; Imboden, J.; Link, T.; et al. Hypomethylation of CYP2E1 and DUSP22 Promoters Associated With Disease Activity and Erosive Disease Among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 70, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhead, B.; Holingue, C.; Cole, M.; Shao, X.; Quach, H.L.; Quach, D.; Shah, K.; Sinclair, E.; Graf, J.; Link, T.; et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis Naive T Cells Share Hypermethylation Sites With Synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 69, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawtree, S.; Muthana, M.; Wilson, A.G. The role of histone deacetylases in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K.; Whitaker, J.W.; Boyle, D.L.; Wang, W.; Firestein, G.S. DNA methylome signature in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rica, L.; et al. Identification of novel markers in rheumatoid arthritis through integrated analysis of DNA methylation and microRNA expression. J. Autoimmun. 2013, 41, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martell, K.J.; Angelotti, T.; Ullrich, A. The "VH1-like" Dual-Specificity Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases. Mol. Cells 1998, 8, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.J.; Zhou, G.; Juan, T.; Colicos, S.M.; Cannon, J.P.; Cabriera-Hansen, M.; Meyer, C.F.; Jurecic, R.; Copeland, N.G.; Gilbert, D.J.; et al. The Dual Specificity JKAP Specifically Activates the c-Jun N-terminal Kinase Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 36592–36601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekine, Y.; Tsuji, S.; Ikeda, O.; Sato, N.; Aoki, N.; Aoyama, K.; Sugiyama, K.; Matsuda, T. Regulation of STAT3-mediated signaling by LMW-DSP2. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5801–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-P.; Yang, C.-Y.; Chuang, H.-C.; Lan, J.-L.; Chen, D.-Y.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, X.; Chen, A.J.; Belmont, J.W.; Tan, T.-H. The phosphatase JKAP/DUSP22 inhibits T-cell receptor signalling and autoimmunity by inactivating Lck. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

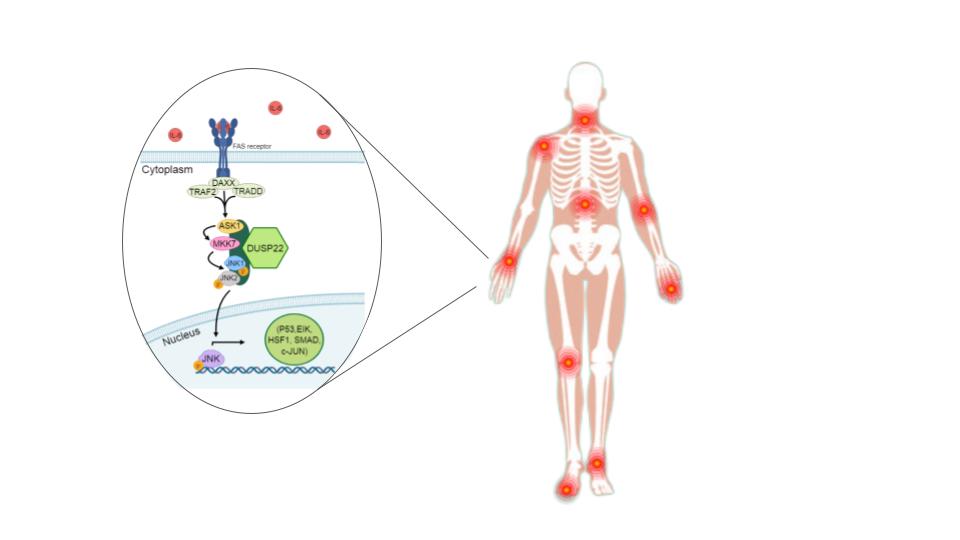

- Ju, A.; Cho, Y.-C.; Kim, B.R.; Park, S.G.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.; Park, B.C.; Cho, S.; Papa, S. Scaffold Role of DUSP22 in ASK1-MKK7-JNK Signaling Pathway. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0164259–e0164259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoloni, E.; Ludovini, V.; Alunno, A.; Pistola, L.; Bistoni, O.; Crinò, L.; Gerli, R. Increased levels of circulating DNA in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases: A possible marker of disease activity in Sjögren’s syndrome. Lupus 2011, 20, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.A.; Meister, S.; Urbonaviciute, V.; Rödel, F.; Wilhelm, S.; Kalden, J.R.; Manger, K.; Voll, R.E. Sensitive detection of plasma/serum DNA in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity 2007, 40, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, M.; Giuliano, T.; Cuomo, G.; Doveri, M.; Tani, C.; Curcio, M.; Abignano, G.; De Feo, F.; Bazzichi, L.; Della Rossa, A.; et al. Cell-free DNA in the plasma of patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2009, 28, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykova, E.; Sizikov, A.; Roggenbuck, D.; Antonenko, O.; Bryzgalov, L.; Morozkin, E.; Skvortsova, K.; Vlassov, V.; Laktionov, P.; Kozlov, V. Circulating DNA in rheumatoid arthritis: pathological changes and association with clinically used serological markers. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, S.; DeGroot, J.; TeKoppele, J.M.; Tarkowski, A.; Collins, L.V. Extracellular mitochondrial DNA and oxidatively damaged DNA in synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2003, 5, R234–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.-Y.; von MühLenen, I.; Li, Y.; Kang, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Tyndall, A.; Holzgreve, W.; Hahn, S.; Hasler, P. Increased concentrations of antibody-bound circulatory cell-free DNA in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Chem. 2007, 53, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Yoshida, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Nakai, A.; Kaneshiro, K.; Suzuki, K.; Kawasaki, Y.; Shibanuma, N.; Hashiramoto, A. Circulating cell free DNA: a marker to predict the therapeutic response for biological DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 20, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2005, 23, S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boini, S.; Guillemin, F. Radiographic scoring methods as outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis: properties and advantages. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2001, 60, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijde, D.; Dankert, T.; Nieman, F.; Rau, R.; Boers, M. Reliability and sensitivity to change of a simplification of the Sharp/van der Heijde radiological assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 1999, 38, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altorok, N.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in naive CD4+ T cells from patients with primary Sjögren ’ s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-M.; Hung, W.-T.; Li, J.-P.; Chen, D.-Y.; Lan, J.-L.; Tan, T.-H. Downregulation of the phosphatase JKAP/DUSP22 in T cells as a potential new biomarker of systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57593–57605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribbs, A.P.; Kennedy, A.; Penn, H.; Amjadi, P.; Green, P.; Read, J.E.; Brennan, F.; Gregory, B.; Williams, R.O. Methotrexate Restores Regulatory T Cell Function Through Demethylation of the FoxP3 Upstream Enhancer in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andres, M.C.; et al. Assessment of global DNA methylation in peripheral blood cell subpopulations of early rheumatoid arthritis before and after methotrexate. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guderud, K.; Sunde, L.H.; Flåm, S.T.; Mæhlen, M.T.; Mjaavatten, M.D.; Lillegraven, S.; Aga, A.-B.; Evenrød, I.M.; Norli, E.S.; Andreassen, B.K.; et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients, Both Newly Diagnosed and Methotrexate Treated, Show More DNA Methylation Differences in CD4+ Memory Than in CD4+ Naïve T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Chang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Huang, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. JNK Pathway-Associated Phosphatase/DUSP22 Suppresses CD4+ T-Cell Activation and Th1/Th17-Cell Differentiation and Negatively Correlates with Clinical Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, E.D.; et al. A subset of methylated CpG sites differentiate psoriatic from normal skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012, 132 Pt 1, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guma, M.; Firestein, G.S. c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase in Inflammation and Rheumatic Diseases. Open Rheumatol. J. 2012, 2, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.-Q.; Zhou, L.-F. MAPK/JNK signalling: a potential autophagy regulation pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vomero, M.; Barbati, C.; Colasanti, T.; Perricone, C.; Novelli, L.; Ceccarelli, F.; Spinelli, F.R.; Di Franco, M.; Conti, F.; Valesini, G.; et al. Autophagy and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Current Knowledges and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; He, Z.; Qin, Y.; Shen, Q. The Autophagy Level Is Increased in the Synovial Tissues of Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis and Is Correlated with Disease Severity. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClay, J.L.; Aberg, K.A.; Clark, S.L.; Nerella, S.; Kumar, G.; Xie, L.Y.; Hudson, A.D.; Harada, A.; Hultman, C.M.; Magnusson, P.K.; et al. A methylome-wide study of aging using massively parallel sequencing of the methyl-CpG-enriched genomic fraction from blood in over 700 subjects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 23, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florath, I.; Butterbach, K.; Müller, H.; Bewerunge-Hudler, M.; Brenner, H. Cross-sectional and longitudinal changes in DNA methylation with age: an epigenome-wide analysis revealing over 60 novel age-associated CpG sites. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 23, 1186–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Pan, C.-L.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liu, B.-Q.; Han, Y.; Hu, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Qu, J.-W.; Liu, W.-T. Selective suppression of the JNK-MMP2/9 signal pathway by tetramethylpyrazine attenuates neuropathic pain in rats. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawatkar, A.A.; Gabriel, S.E.; Jacobsen, S.J. Secular trends in the incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis within members of an integrated health care delivery system. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arhtritis patients. Am J Med 2013, 126, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, R.; del Rincon, I.; Farook, V.S.; Restrepo, J.F.; A Winnier, D.; Fourcaudot, M.J.; Battafarano, D.F.; de Almeida, M.; Kumar, S.; E Curran, J.; et al. Genetic Variants Influencing Joint Damage in Mexican Americans and European Americans With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Genet. Epidemiology 2015, 39, 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Rincón, I.; Battafarano, D.F.; Arroyo, R.A.; Murphy, F.T.; Fischbach, M.; Escalante, A. Ethnic variation in the clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: Role of HLA–DRB1 alleles. Arthritis Care Res. 2003, 49, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).