Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

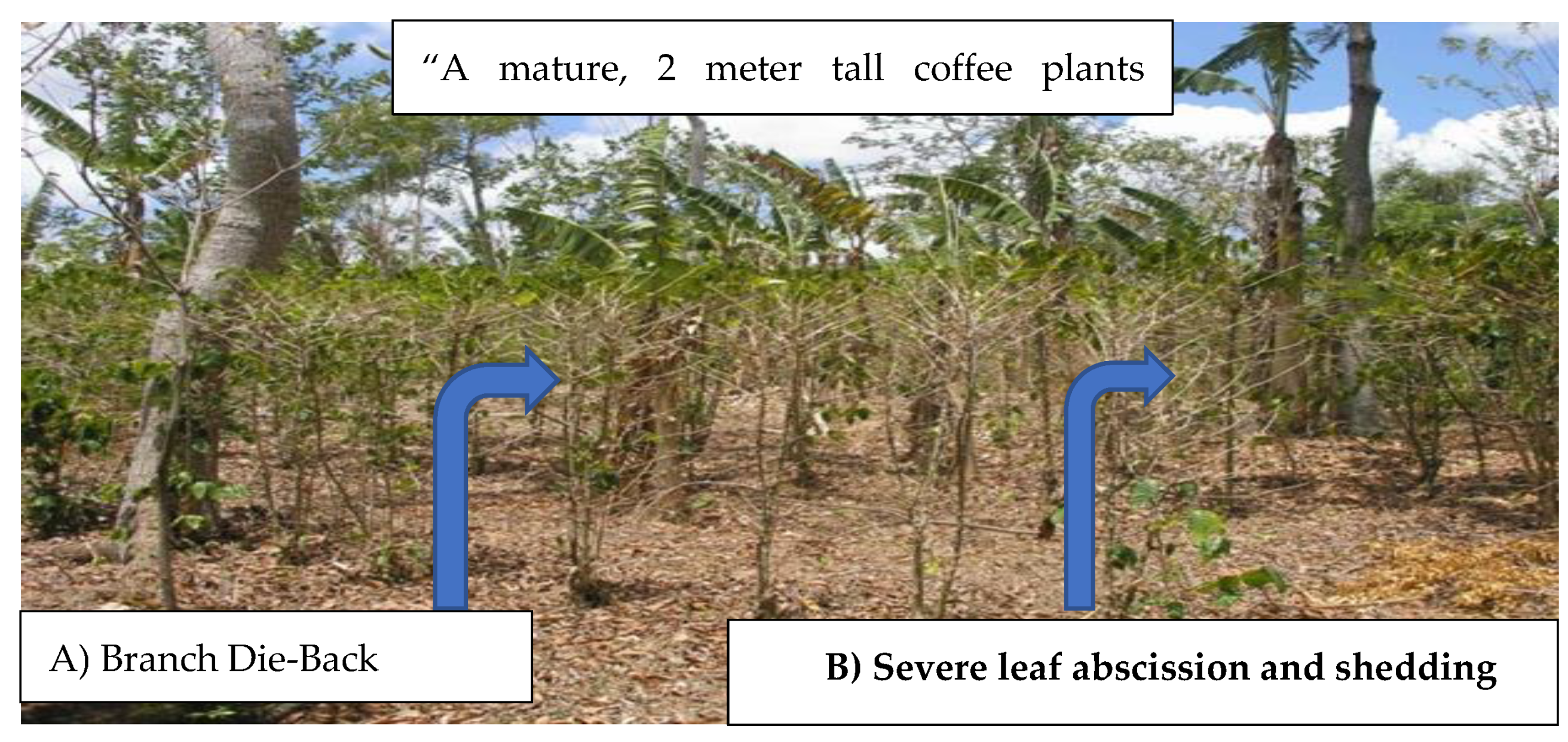

2. Effects of Drought Stress on Coffee

2.1. Physiological and Growth Impacts of Drought. Stress

2.1.1. Primary Physiological Disruptions

2.1.2. Consequences on Plant Growth and Biomass Partitioning

2.2. Effects of Drought on Yield and Quality

2.3. Effects of Drought on Coffee Pests and Diseases

2.4. Effects of Drought on Suitable Area for Coffee Cultivation

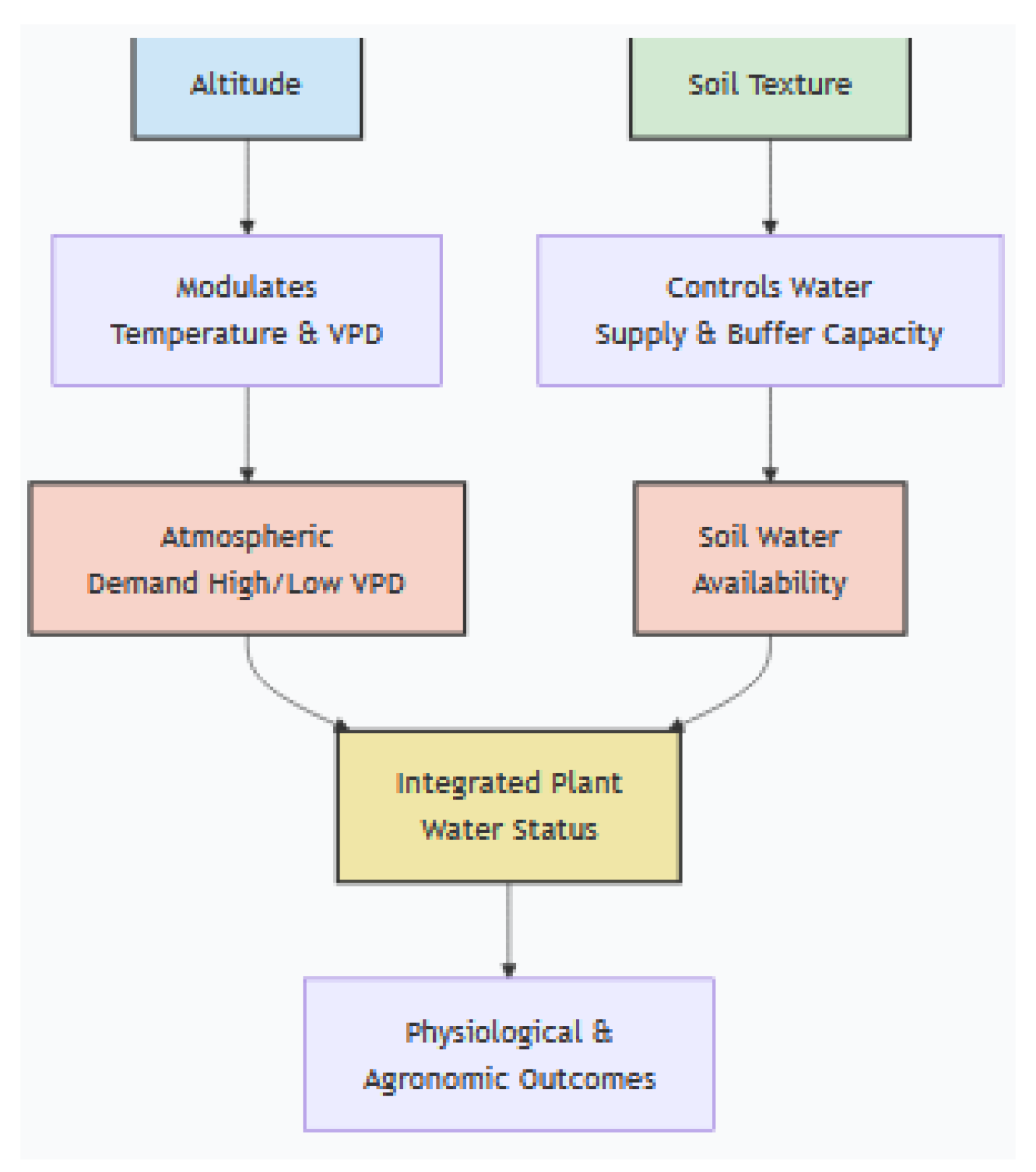

3. Determinants of Drought Impacts on Coffee

3.1. Duration, Severity, and Intensity of Drought

| Determinant Factors | Outcomes of the Factors | References |

|---|---|---|

| Duration, Severity, Intensity | Longer, more severe or intense, lead to oxidative stress, reproductive failure, and lead to yield loss | [2,10,63,64,65,66,67] |

| Species and Cultivar | Tolerant varieties exhibit longer roots; close stomata and higher water use efficiency, osmolyte accumulation, and delayed wilting. | [15,23,28,29,30,31,68,69,70] |

| Temperature | Synergistically worsening drought impacts | [9,10,12,30,75,76] |

| Sunshine, Humidity & Wind | High solar radiation, low humidity, and strong winds increase atmospheric demand and evapotranspiration, rapidly depleting soil moisture. | [30,66,75,77,78,79,80] |

| Slope, Aspect, Curvature | Steep slopes and convex ridges increase runoff worsen drought impact; west-facing slopes are drier. Gentle, concave, and lower slopes retain more water better alleviate drought impacts. | [30,66,68,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] |

| Soil Fertility | Degraded soils aggravate drought impacts as compared to fertile soil . | [104,105,106,107,108,109] |

| Farm Management | Practices like agroforestry, conservation, and precision soil and water management enhance drought resilience, while ignored fields are more prone to drought impacts. | [10,111,112,113,114,115] |

3.2. Genetic Factors

3.3. Environmental Factors

3.3.1. Temperature

3.3.2. Sunshine, Relative Humidity and Wind

3.4. Topographic and Edaphic Factors

3.4.1. Elevation

3.4.2. Slope, Aspect and Curvature of the Land

3.4.3. Soil Type and Fertility Status

3.5. Management Factors

4. Adaptation and Coping Measures to Drought Stress

4.1. Breeding and Cultivar Selection

| Variety/Clone (Species) | Key Drought-Resistance Traits | References |

|---|---|---|

| Apoatã IAC 2258 (C. canephora) | Deep & Prolific Root System (Primary trait) | [23,120] |

| Sarchimor (e.g., T5296, Costa Rica 95) (C. arabica) | Stomatal Regulation (Early closure) Osmotic Adjustment (Accumulation of solutes) Compact Structure (Lower leaf area) |

[12,129,135] |

| Icatu (C. arabica) | Leaf Traits (Thicker leaves, waxier cuticles) Robust Root System (From Robusta parentage) Control of oxidative stress |

[41,129,130] |

| Caturra | Stomatal Regulation (Early closure) High ware use efficiency |

[129,131,132] |

| Castillo / Centroamericano (C. arabica) | Osmotic Adjustment (Primary trait) Stomatal Regulation |

[131] |

| IAPAR 59 (C. arabica) | Vigorous Root System (From Robusta parentage) Leaf Shedding Mechanism (Reduces transpirational area) |

[68,133] |

| F1 Hybrids (e.g., Starmaya) (C. arabica) | Hydraulic Conductance (Efficient water transport - from heterosis) Robust Root System (From heterosis) |

[134,135] |

| F1 Hybrids (e.g., Mundo Maya) | Maintenance of photosynthesis Enhanced root density |

[134,135] |

4.2. Preconditioning

4.3. Plant Nutrition

4.4. Irrigation

4.5. Soil and Water Conservation

4.6. Agroforestry and Shade Management

4.7. Crop Management and Diversification

4.8. Training and Extension Services

4.9. Policy Development and Institutional Support

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, AP.; Gole, TW.; Baena, S.; Moat, J. The impact of climate change on indigenous Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.): predicting future trends and identifying priorities. PloS one 2012, 7(11), e47981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, FM.; Ronchi, CP.; Maestri, M.; Barros, RS. Coffee: Environment and Crop Physiology. In Ecophysiology of Tropical Tree Crops; DaMatta, F.M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 181–216. [Google Scholar]

- ICO. World Coffee Production. 2023. Available online: www.ico.org (Accessed: 15 June 2024).

- DaMatta, FM.; Rahn, E; Läderach, P; Ghini, R; Ramalho, JC. Why could the coffee crop endure climate change and global warming to a greater extent than previously estimated? Climatic Change 2019, 152, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, JN.; Rodrigues, AP.; Lidon, FC.; Pais, IP.; Marques, I.; Gouveia, D.; Armengaud, J.; Silva, MJ.; Martins, S.; Semedo, MC.; Dubberstein, D.; Partelli, FL.; Reboredo, FH.; Scotti-Campos, P.; Ribeiro-Barros, AI.; DaMatta, FM.; Ramalho, JC. Intrinsic non-stomatal resilience to drought of the photosynthetic apparatus in Coffea spp. is strengthened by elevated air [CO2]. Tree Physiology 2021, 41, 708–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ECTA, Annual Report 2023.

- Worku, M. Production, productivity, quality and chemical composition of Ethiopian coffee. Cogent Food and Agriculture 2023, 9, 2196868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, W. Photosynthesis as a tool for indicating temperature stress events. In Ecophysiology of photosynthesis; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1995; pp. 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Moat, J.; Williams, J.; Baena, S.; Wilkinson, T.; Demissew, S.; Challa, ZK.; Davis, AP. Resilience potential of the Ethiopian coffee sector under climate change. Nature Plants 2017, 3(4), 17081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DaMatta, FM.; Ramalho, JDC. Impacts of drought and temperature stress on coffee physiology and production: a review. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology 2006, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruta, R.D.; Mereu, V.; Spano, D.; Marras, S.; Vezy, R.; Trabucco, A. Projecting trends of arabica coffee yield under climate change: A process-based modelling study at continental scale. Agricultural Systems 2025, 104353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, FM.; Avila, RT.; Cardoso, AA.; Martins, SC.; Ramalho, JC. Physiological and agronomic performance of the coffee crop in the context of climate change and global warming: A review. J. Agric Food Chem.;PubMed 2018, 66, 5264–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, C.; El Chami, D.; Mereu, V.; Trabucco, A.; Marras, S.; Spano, D. A Systematic Review on Impacts of Climate Change on Coffee Agroecosystems. Plants 2023, 12, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Reinoso, AD.; Ávila-Pedraza, EÁ.; Lombardini, L.; Restrepo-Díaz, H. The application of coffee pulp biochar improves the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of soil for coffee cultivation. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2023, 23(2), 2512–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekol, H.; Warkineh, B.; Shimber, T.; Mierek-Adamska, A.; Dąbrowska, G.B.; Degu, A. Drought stress responses in Arabica coffee genotypes: Physiological and metabolic insights. Plants 2024, 13(6), 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, CA.; Manivannan, P.; Wang, HZ. Water-deficit stress effects on plant growth, photosynthesis, and lipid peroxidation in coffee. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2009, 47(2), 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Mingchi, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhao, F. The impact of drought on coffee growth and yield. Plant Growth Regulation 2010, 60(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Din, J.; Khan, SU.; Ali, I.; Gurmani, AR. Physiological and agronomic response of canola varieties to drought stress. The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences 2011, 21(1), 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends in Plant Science 2002, 7(9), 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, M.E.A. ‘Photosynthesis and photoinhibition’. In Plant Responses to Air Pollution; 2008; pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulos, SA.; Sari, FM.; Papadopoulos, IA. Dry matter partitioning and stress adaptation in coffee plants. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2008, 194(3), 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, QS.; Xia, RX.; Zou, YN. Improved soil structure and citrus growth after inoculation with three arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under drought stress. European Journal of Soil Biology 2008, 44(1), 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, HA.; DaMatta, FM.; Chaves, ARM.; Loureiro, ME; Ducatti, C. Drought tolerance is associated with rooting depth and stomatal control of water use in clones of Coffea canephora. Annals of Botany 2005, 96, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Builes, VH.; Küsters, J.; Thiele, E.; Lopez-Ruiz, JC. Physiological and Agronomical Response of Coffee to Different Nitrogen Forms with and without Water Stress. Plants 2024, 13(10), 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan, D; Ramaiah, PK. Osmotic adjustments under water stress in coffee. Proceeding of the12th Interna-tional Scientific Colloquium on coffee (ASIC) conferences, Montreux, Switzerland, 1987; pp. 493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer, FC; Saliendra, NZ; Crisosto, CH. Carbon iso-tope discrimination and gas exchange in Coffea arabica during adjustment to different soil moisture regimes. Australian J. Plant. Physiol. 1992, 19, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M. Exploring drought tolerance in coffee: A physiological approach with some insights for plant breeding. Brazil Journal of Plant Physiology 2004, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, M.; Astatkie, T. Dry matter partitioning and physiological responses of Coffea arabica varieties to soil moisture deficit stress at the seedling stage in Southwest Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2010a, 5(15), 2066–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Worku, M.; Astatkie, T. Growth responses of arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.) varieties to soil moisture deficit at the seedling stage at Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Journal of Food, Agriculture and Environment 2010b, 8(1), 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye, M.; Ismail, S.; Asfaw, Z. Coffee production constraints and opportunities in Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2013, 8(50), 6674–6681. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, M.; Worku, M.; Shimbir, T.; Astatkie, T. Root traits and biomass production of drought-resistant and drought-sensitive Arabica coffee varieties growing under contrasting watering regimes. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2024, 7(2), p.e20488. no doi?? [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, C.; Läderach, P.; Ovalle Rivera, O.; Kirschke, D. A bitter cup: climate change profile of global production of Arabica and Robusta coffee. Climatic change 2015, 129(1), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, J.; Muchugu, E.; Vega, FE.; Davis, A.; Borgemeister, C.; Chabi-Olaye, A. Some like it hot: the influence and implications of climate change on coffee berry borer (Hypothenemus hampei) and coffee production in East Africa. PLoS one 2013, 8(11), e88867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, MKV. The water relations and irrigation requirements of coffee. Experimental agriculture 2001, 37(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, C.; Estrada, F.; Conde, C.; Eakin, H.; Villers, L. Potential impacts of climate change on agriculture: A case of study of coffee production in Veracruz, Mexico. Climatic Change 2006, 79(3-4), 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, CW. Effects of water stress on coffee bean quality. Journal of Coffee Science 2007, 9(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Damayanti, MH.; Rachman, MS. Drought Adaptation and Coping Strategies among Coffee Farmers in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. ResearchGate. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/.

- Nuryanti, S.; Siregar, N.; Darusman, D.; Sudarsono, S. Impact of Climate Change on Coffee Quality and Yield. East African Scholars Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences 2021, 3(11), 1–8. Available online: https://www.easpublisher.com/get-articles/4388.

- Carmo-Silva, E.; Scales, JC.; Parker, P. The effects of drought on coffee plant physiology. Journal of Experimental Botany 2017, 68(16), 4623–4634. [Google Scholar]

- Flexas, J.; Bota, J.; Escalona, J. M. Effects of drought on photosynthesis in coffee plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2006, 57(15), 3713–3722. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, JC.; Rodrigues, AP.; Lidon, FC.; Marques, LM.; Leitão, AE.; Fortunato, AS.; Pais, IP.; Silva, MJ.; Scotti-Campos, P.; Lopes, A.; Reboredo, FH. Stress cross-response of the antioxidative system promoted by superimposed drought and cold conditions in Coffea spp. PLoS one 2018, 13(6), e0198694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz de Carvalho, MH. Drought stress and reactive oxygen species: production, scavenging and signaling. Plant signaling & behavior 2008, 3(3), 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Moller, IM.; Jensen, PE.; Hansson, A. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in plant cells. Annual Review of Plant Bi-ology 2007, 58, 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter, H.; Nagel, O. The role of biomass allocation in the growth response of plants to different levels of light, CO2, nutrients and water: a quantitative review. Functional Plant Biology 2000, 27(12), 1191–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, PC.; Araujo, WL.; Moraes, GABK.; Barros, RS.; DaMatta, FM. Morphological and Physiological Responses of Two Coffee Progenies to Soil Water Availability. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 164, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, CD.; Berkowitz, AR.; Kelly, VR.; Lovett, GM.; Ollinger, SV.; Schnurr, J. Biomass allocation and multiple resource limitation in tree seedlings. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 1996, 26(9), 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leport, L.; Turner, NC.; Davies, SL.; Siddique, KHM. Variation in pod production and abortion among chickpea cultivars under terminal drought. European Journal of Agronomy 2006, 24(3), 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J. Effects of drought stress on root and shoot biomass in coffee plants. Plant Growth Regu-lation 2014, 73(2), 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Komor, E. Source physiology and assimilate transport: the interaction of sucrose metabolism, starch storage and phloem export in source leaves and the effects on sugar status in phloem. Functional Plant Biology 2000, 27(6), 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, SW.; Lee, SK.; Jeong, HJ.; An, G.; Jeon, JS.; Jung, KH. Crosstalk between diurnal rhythm and water stress reveals an altered primary carbon flux into soluble sugars in drought-treated rice leaves. Scientific Reports 2017, 7(1), 8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinselmeier, C.; Jeong, BR.; Boyer, JS. Starch and the control of kernel number in maize at low water potentials. Plant physiology 1999, 121(1), 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, JR.; Silva, CM.; de Almeida, RF. Climate change impacts on coffee yield and quality. Agricultural Meteorology 2018, 254, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Byrareddy, V.; Kouadio, L.; Mushtaq, S.; Kath, J.; Stone, R. Coping with drought: Lessons learned from Robusta coffee growers in Vietnam. Climate Services 2021, 22, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, TI. Abundance of pests and diseases in Arabica coffee production systems in Uganda-ecological mechanisms and spatial analysis in the face of climate change. Doctoral dissertation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil, M.; Rao, AN. Influence of drought on coffee pests and diseases. Tropical Agriculture 1998, 75(2), 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, S.; Gómez, M.; Fernández, A. Increased incidence of pests and diseases in drought-stressed coffee plants. Plant Pathology Journal 2018, 37(4), 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, A.; Senthil-Kumar, M. Drought: a context-dependent damper and aggravator of plant diseases. Plant, Cell & Environment 2024, 47(6), 2109–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Y.; Reardon-Smith, K.; Mushtaq, S.; Cockfield, G. The impact of climate change and variability on coffee production: a systematic review. Climatic Change 2019, 156, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrach, A; Ghazoul, J. Climate and Pest-Driven Geographic Shifts in Global Coffee Production: Implications for Forest Cover, Biodiversity and Carbon Storage. PLoS One 2015, 15;10(7), e0133071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ovalle-Rivera, O; Läderach, P; Bunn, C; Obersteiner, M; Schroth, G. Projected shifts in Coffea arabica suitability among major global producing regions due to climate change. PLoS One 2015, 14;10(4), e0124155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malhi, Y.; Roberts, J. T.; Rippel, C. The changing dynamics of coffee production in the context of climate change. Agricultural Systems 2017, 157, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Klaus, M.; Khoury, CK.; Andersson, M. Coffee cultivation shifts to higher altitudes in response to climate change. Agricultural Systems 2016, 144, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessmentreport/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf.

- Silva, PEM.; Cavatte, PC.; Morais, L.; Medina, EF.; DaMatta, FM. The functional divergence of biomass partitioning, carbon gain and water use in Coffea canephora in response to the water supply: Implications for breeding aimed at improving drought tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 87, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, SCL.; Soares, FF.; Rossi, TRA.; Cangussu, MCT.; Figueiredo, ACL.; Cruz, DN.; Cury, PR. Características do acesso e utilização de serviços odontológicos em municípios de médio porte. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 2012, 17, 3115–3124. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, SC.; Galmes, J.; Cavatte, PC.; Pereira, LF.; Ventrella, MC.; DaMatta, FM. Understanding the low photo-synthetic rates of sun and shade coffee leaves: Bridging the gap on the relative roles of hydraulic, diffusive and biochemical constraints to photosynthesis. In PLoS ONE; PubMed, 2014; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, W.P.; Martins, M.Q.; Fortunato, A.S.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Semedo, J.N.; Simões-Costa, M.C.; Pais, I.P.; Leitão, A.E.; Colwell, F.; Goulao, L.; Máguas, C. Long-term elevated air [CO2] strengthens photosynthetic functioning and mitigates the impact of supra-optimal temperatures in tropical Coffea arabica and C. canephora species. Global change biology 2016, 22(1), 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, PCD.; Junior, WQR.; Ramos, MLG.; Rocha, OC.; Veiga, AD.; Silva, NH.; Brasileiro, LDO.; Santana, CC.; Soares, GF.; Malaquias, JV.; Vinson, CC. Physiological changes of Arabica coffee under different intensities and durations of water stress in the Brazilian Cerrado. Plants 2022, 11(17), 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, RT.; Cardoso, AA.; de Almeida, WL.; Costa, LC.; Machado, KL.; Barbosa, ML.; de Souza, RP.; Oliveira, LA.; Batista, DS.; Martins, SC.; Ramalho, JD. Coffee plants respond to drought and elevated [CO2] through changes in stomatal function, plant hydraulic conductance, and aquaporin expression. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2020, 177, 104148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutouleas, A.; Sarzynski, T.; Bordeaux, M.; Bosselmann, AS.; Campa, C.; Etienne, H.; Turreira-García, N.; Rigal, C.; Vaast, P.; Ramalho, JC.; Marraccini, P. Shaded-coffee: A nature-based strategy for coffee production under climate change? A review. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6, 877476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Lisar, SY.; Bakhshayeshan-Agdam, H. Drought stress in plants: causes, consequences, and tolerance. In Drought stress tolerance in plants;physiology and biochemistry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; Vol 1, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- McKersie, BD.; Leshem, YY. Water and drought stress. In Stress and stress coping in cultivated plants; Kiuwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1994; pp. pp 148–180. [Google Scholar]

- López, J.; Way, D.A.; Sadok, W. Systemic effects of rising atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on plant physiology and productivity. Global Change Biology 2021, 27(9), 1704–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, HS.; Singh, G.; Sharma, P.; Bains, TS. Water Use Efficiency Under Stress Environments In: Climate Change and Management of Cool Season Grain Legume Crops; Yadav, SS., Mc Neil, DL., Redden, R., Patil, SA., Eds.; Springer Press: Dordrecht-Heidelberg-London-New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, A.; Mariani, L. Agronomic management for enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stresses: High and low values of temperature, light intensity, and relative humidity. Horticulturae 2018, 4(3), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A. Yale program on climate change communication. Journal of Applied Communication Research 2025, 53(1), 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzynski, T.; Vaast, P.; Rigal, C.; Marraccini, P.; Delahaie, B.; Georget, F.; Nguyen, CTQ.; Nguyen, HP.; Nguyen, HTT.; Ngoc, QL.; Ngan, GK. Contrasted agronomical and physiological responses of five Coffea arabica genotypes under soil water deficit in field conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1443900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, MB.; Marcelo, BP. The impact of climatic variability in coffee crop. International Conference on Coffee Science, 22nd, Campinas, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lince-Salazar, LA.; Sadeghian, KS. Soil taxonomy, consideration for the coffee regions of Colombia. Boletín Técnico Cenicafé (In Spanish). 2021, 45, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Baik, J.; Fred, S.; Choi, M. Comparative analysis of two drought indices in the calculation of drought recovery time and implications on drought assessment: East Africa’s Lake Victoria Basin. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 2022, 36(7), 1943–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gichimu, B.M.; Cheserek, J.J. Drought and heat tolerance in coffee: a review. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, BP.; Klittich, WM.; Horton, R.; Vangenuchten, MT. Spatiotemporal variability of soil-temperature within land areas exposed to different tillage systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1995, 59(3), 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, JS.; Rudnicki, JW.; Rodell, M. Variability in surface moisture content along a hillslope transect: Rattlesnake Hill, Texas. J. Hydrol. 1998, 210(1-4), 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Fu, BJ.; Wang, J.; Chen, LD. Soil moisture variation in relation to topography and land use in a hillslope catchment of the Loess Plateau. China. J. Hydrol. 2001, 240(3-4), 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, AW.; Zhou, SL.; Grayson, RB.; McMahon, TA.; Blöschl, G.; Wilson, DJ. Spatial correlation of soil moisture in small catchments and its relationship to dominant spatial hydrological processes. Journal of Hydrology 2004, 286(1-4), 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, BN.; Meyer, GA.; McFadden, LD. Aspect-related microclimatic influences on slope forms and processes, northeastern Arizona. J. Geophys. Res.-Earth 2008, 113(F3), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroy, IJ.; et al. Aspect influences on soil water retention and storage. Hydrol. Process 2011, 25(25), 3836–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Jurado, HA.; Vivoni, ER. Ecogeomorphic expressions of an aspect-controlled semiarid basin: I. Topo-graphic analyses with high-resolution data sets. Ecohydrology 2013, 6(1), 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Tao, W.; Qin, G.; Hopkins, I.; et al. ‘Soil micro-climate variation in relation to slope aspect, position, and curvature in a forested catchment’. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2020, 290, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, SN.; Strohmeier, S.; Klik, A.; Singh, RM. Advances in soil moisture retrieval from multispectral remote sensing using unoccupied aircraft systems and machine learning techniques. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2021, 25(3), 2739–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndabasanze, P. Suitability analysis of coffee growing area in the Context of climate change in Nyaruguru District, Rwanda. Doctoral dissertation, University of Rwanda, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mallet, F.; Marc, V.; Douvinet, J.; Ruy, S. ‘Assessing soil water content variation in a small mountainous catchment over different time scales and land covers using geographical variables’. Journal of Hydrology 2020, 590, 125492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, R.; Aron, RH.; Todhunter, P. The climate near the ground; Rowman & Littlefield, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenbergerová, L.; Klimková, M.; Cano, Y.G.; Habrová, H.; Lvončík, S.; Volařík, D.; Khum, W.; Němec, P.; Kim, S.; Jelínek, P.; Maděra, P. ‘Does shade impact coffee yield, tree trunk, and soil moisture on Coffea canephora plantations in Mondulkiri, Cambodia?’. Sustainability 2021, 13(24), 13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crave, A.; Gascuel-Odoux, C. The influence of topography on time and space distribution of soil surface water content. Hydrological processes 1997, 11(2), 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lannoy, GJM.; Verhoest, NEC.; Houser, PR.; Gish, TJ.; Van Meirvenne, M. Spatial and temporal characteristics of soil moisture in an intensively monitored agricultural field (OPE3). J. Hydrol. 2006, 331(3-4), 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Nie, XF.; Zhou, XB.; Liao, KH.; Li, HP. Soil moisture response to rainfall at different topographic positions along a mixed land-use hillslope. Catena 2014, 119, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, ZY.; Wang, XD.; Zhang, SY.; He, B.; Zhao, XL.; Kong, FL.; Feng, D.; Zeng, YC. ‘Response of soil water dynamics to rainfall on a collapsing gully slope: based on continuous multi-depth measurements’. Water 2020, 12(8), 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.R.; Erskine, R.H. Measurement and inference of profile soil-water dynamics at different hillslope positions in a semiarid agricultural watershed. Water Resources Research 2011, 47(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, TP.; Butcher, DP. Topographic controls of soil-moisture distributions. J. Soil Sci. 1985, 36(3), 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, ID.; Burch, GJ.; Mackenzie, DH. Topographic effects on the distribution of surface soil-water and the location of ephemeral gullies. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1988, 31(4), 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Tanzi, S.; Dietsch, T.; Urena, N.; Vindas, L.; Chandler, M. Analysis of management and site factors to improve the sustainability of smallholder coffee production in Tarrazú, Costa Rica. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2012, 155, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Kobusinge, J.; Twesigye, CK.; Kagezi, GH.; Ssembajwe, R.; Arinaitwe, G. Soil Moisture Content Suitability for Coffee Growing under Climate Change Scenarios in Uganda. PhD Thesis, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Merga, D.; Beksisa, L. Mechanisms of drought tolerance in coffee (Coffea Arabica L.): implication for genetic im-provement program. American Journal of BioScience 2023, 11(3), 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, BM.; de Oliveira, GC.; Serafim, ME.; Carducci, CE.; da Silva, ÉA.; Barbosa, SM.; de Melo, LBB.; dos Santos, WJR.; Reis, THP.; de Oliveira, CHC.; Guimarães, PTG. Soil management and water-use efficiency in Brazilian coffee crops. In Coffee-Production and Research; IntechOpen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chemura, A. The growth response of coffee (Coffea arabica L) plants to organic manure, inorganic fertilizers and integrated soil fertility management under different irrigation water supply levels. International Journal of Recycling of Organic Waste in Agriculture 2014, 3(2), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudjabi, S.; Ababsa, N.; Chenchouni, H. Enhancing soil resilience and crop physiology with biochar application for mitigating drought stress in durum wheat (Triticum durum). Heliyon 2023, 9(12), e22909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, R.; Jahan, S.; Zafar, M.; Naeem, M.B.; Usman, S.; Shah, A.A.; Nazim, M.; Alsahli, A.A. Organic amendments optimize Triticum aestivum var Zincol-16 performance under water stress through enhancement in physiobiochemical traits, secondary metabolites and yield. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 17995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, FM.; Chaves, ARM.; Pinheiro, HA.; Ducatti, C.; Loureiro, ME. Drought tolerance of two field-grown clones of Coffea canephora. Plant Science 2003, 164, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefa, A. Impact of Water Stress and Irrigation Scheduling on Arabica coffee at Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia: A Review. Int.J.Curr.Res.Aca.Rev 2023, 11(08), 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, P.; Burgess, PJ.; Girkin, NT. Opportunities for enhancing the climate resilience of coffee production through improved crop, soil and water management. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 47(8), 1125–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Barron, J. A reply to Lankford and Agol (2024). Irrigation is more than irrigating: agricultural green water interventions contribute to blue water depletion and the global water crisis. Water International 2025, 50(1), 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, L.; Ferrante, A. Agronomic management for enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stresses—drought, salinity, hypoxia, and lodging. Horticulturae 2017, 3(4), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Herrera, DF.; Sánchez-Reinoso, AD.; Lombardini, L.; Restrepo-Díaz, H. Physiological responses of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) plants to biochar application under water deficit conditions. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2023, 51(3), 12873–12873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sott, M.K.; Furstenau, L.B.; Kipper, L.M.; Giraldo, F.D.; Lopez-Robles, J.R.; Cobo, M.J.; Zahid, A.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Imran, M.A. Precision techniques and agriculture 4.0 technologies to promote sustainability in the coffee sector: state of the art, challenges and future trends. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 149854–149867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletić, RPR.; Dodig, D.; Milutinović, S.; Mihajlović, I.; Nikodijević, SM. Strategies for solving the problem of drought in Eastern crop.icidonline.org/40doc.pdf. 2010.

- Faraz, M.; Mereu, V.; Spano, D.; Trabucco, A.; Marras, S.; El Chami, D. A systematic review of analytical and mod-elling tools to assess climate change impacts and adaptation on coffee agrosystems. Sustainability 2023, 15(19), 14582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, A.; Ferreira, SG.; Machado, SR. Strategies for managing coffee under drought conditions. Agricultural Water Management 2020, 239, 106248. [Google Scholar]

- Sisay, BT. Coffee production and climate change in Ethiopia. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Climate Impact on Agriculture, 2018; Volume 33, pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho, JC; Marques, I; Pais, IP; Armengaud, J; Gouveia, D; Rodrigues, AP; Dubberstein, D; Leitão, AE; Rakočević, M; Scot-ti-Campos, P; Martins, S; Semedo, MC; Partelli, FL; Lidon, FC; DaMatta, FM; Ribeiro-Barros, AI. Stress resilience in Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora under harsh drought and/or heat conditions: selected genes, proteins, and lipid integrated responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1623156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, BP.; Martinez, HEP.; de Carvalho, FP.; Loureiro, ME.; Sturião, WP. Gas Exchanges and Chlorophyll Fluorescence of Young Coffee Plants Submitted to Water and Nitrogen Stresses. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 43, 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazuoli, LC.; Braghini, MT.; Silvarolla, MB.; Gonçalves, W.; Mistro, JC.; Gallo, PB.; Guerreiro Filho, O. IAC. Catuaí SH3—A Dwarf Arabica Coffee Cultivar with Leaf Rust Resistance and Drought Tolerance. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Pereira, J.S.; Maroco, J. Understanding plant responses to drought from genes to the whole plant. Functional Plant Biology 2003, 30, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounekti, T.; Mahdhi, M.; Al-Turki, TA.; Khemira, H. Water relations and photo-protection mechanisms during drought stress in four coffee (Coffea Arabica L.) cultivars from southwestern Saudi Arabia. South African journal of botany 2018, 117, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, I.R.; da Silva Ferreira, M.F.; do Couto, D.P.; Santos, J.G.; Silva, M.A.; Canal, G.B.; de Oliveira Bernardes, C.; Azevedo, C.F.; Ferreira, A. Genome-wide association analysis of traits related to development, abiotic and biotic stress re-sistance in Coffea canephora. Scientia Horticulturae 2025, 341, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.B.; Mazzafera, P. Dehydrins are highly expressed in water-stressed plants of two coffee species. Tropical plant biology 2012, 5(3), 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, G.S.; Rocha, D.C.; Santos, L.N.D.; Contiliani, D.F.; Nobile, P.M.; Martinati-Schenk, J.C.; Padilha, L.; Maluf, M.P.; Lubini, G.; Pereira, T.C.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B. CRISPR technology towards genome editing of the perennial and semi-perennial crops citrus, coffee and sugarcane. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 14, 1331258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Lozano, E.L.I.A.N.A.; Barraza-Celis, A.A.R.O.N.; Ibarra-Rendon, J.O.R.G.E.; Cabrera-Ponce, J.L. Tran-scriptome Analysis of Coffee Coffea arabica L. Drought Tolerant Somatic Embryogenic Line, Mediated by Antisense Trehalase. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tezara, W.; Loyaga, D.W.; Reynel Chila, V.H.; Herrera, A. Photosynthetic Limitations and Growth Traits of Four Arabica Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Genotypes under Water Deficit. Agronomy 2024, 14(8), 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.; Gouveia, D.; Gaillard, J.C.; Martins, S.; Semedo, M.C.; Lidon, F.C.; DaMatta, F.M.; Ribeiro-Barros, A.I.; Armengaud, J.; Ramalho, J.C. Next-generation proteomics reveals a greater antioxidative response to drought in Coffea arabica than in Coffea canephora. Agronomy 2022, 12(1), 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Cortés, S. A Coffee Hope Tale: Coffea arabica Castillo and Caturra varieties survive in a drier world. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, D.; Rivera, R.M. Identifying Coffea genotypes tolerant to water deficit. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.G.; Sera, G.H.; Andreazi, E.; Sera, T.; Fonseca, I.D.B.; Carducci, F.C.; Shigueoka, L.H.; Holderbaum, M.M.; Costa, K.C. Drought tolerance in seedlings of coffee genotypes carrying genes of different species. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Turreira-García, N. Farmers’ perceptions and adoption of Coffea arabica F1 hybrids in Central America. World De-velopment Sustainability 2022, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzynski, T.; Vaast, P.; Rigal, C.; Marraccini, P.; Delahaie, B.; Georget, F.; Nguyen, C.T.Q.; Nguyen, H.P.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Ngoc, Q.L.; Ngan, G.K. Contrasted agronomical and physiological responses of five Coffea arabica genotypes under soil water deficit in field conditions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1443900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sseremba, G.; Tongoona, P.B.; Musoli, P.; Eleblu, J.S.Y.; Melomey, L.D.; Bitalo, D.N.; Atwijukire, E.; Mulindwa, J.; Aryatwijuka, N.; Muhumuza, E.; Kobusinge, J. Viability of deficit irrigation pre-exposure in adapting robusta coffee to drought stress. Agronomy 2023, 13(3), 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, TJ.; Matthes, MC.; Napier, JA.; Pickett, JA. Stressful “memories” of plants: evidence and possible mechanisms. Plant science 2007, 173(6), 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, D.; Li, N.; Zhu, G.; Li, C.; Wang, W. Phosphoproteomic analysis of the response of maize leaves to drought, heat and their combination stress. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 6, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Silva, PE.; Sanglard, LM.; Ávila, RT.; Morais, LE.; Martins, SC.; Nobres, P.; Patreze, CM.; Ferreira, MA.; Araújo, WL.; Fernie, AR.; DaMatta, FM. Photosynthetic and metabolic acclimation to repeated drought events play key roles in drought tolerance in coffee. Journal of experimental botany 2017, 68(15), 4309–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Paszkowski, J. Epigenetic memory in plants. The EMBO journal 2014, 33(18), 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta-Soriano, E.; Munné-Bosch, S. Stress memory and the inevitable effects of drought: a physiological perspective. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraich, EA.; Ahmad, R.; Ashraf, MY. Role of mineral nutrition in alleviation of drought stress in plants. Aust J Crop Sci 2011, 5(6), 764–777. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: San Diego, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, WA.; Hossner, LR.; Onken, AB.; Wedt, CW. Nitrogen and phosphorous uptake in pearl millet and its relation to nutrient and transpiration efficiency. Agron J 1995, 87, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raun, WR.; Johnson, GV. Improving nitrogen use efficiency for cereal production. Agron J 1999, 91, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufty, TW.; Huber, SC.; Volk, RJ. Alterations in leaf carbohydrate metabolism in response to nitrate stress. Plant Physiol 1988, 88, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, L.; Rabêlo, F.H.S.; Marchiori, P.E.R.; Guilherme, L.R.G.; Guerra-Guimarães, L.; Resende, M.L.V.D. Impact of drought, heat, excess light, and salinity on coffee production: strategies for mitigating stress through plant breeding and nutrition. Agriculture 2024, 15(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, LB. Changes in the phosphorus content of Capsicum annuum leaves during water-stress. J Plant Physiol 1985, 121, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, C. Interactive effects of N-P-K-nutrition and water stress on the development of young maize plants. Ph.D. Thesis, ETHZ, Zurich, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson, RC. Osmoregulation in cotton in response to water-stress. Effects of phosphorus fertility. Plant Physiol 1985, 77, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, BK.; Burman, U.; Kathju, S. The influence of phosphorus nutrition on the physiological response of mothbean genotypes to drought. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 2004, 167, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, H.; Payne, WA.; Sattelmacher, B. Effects of phosphorus and water supply on yield, transpirational water-use efficiency, and carbon isotope discrimination of pearl millet. Crop Sci 2000, 40, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawwan, J.; Shibli, RA.; Swaidat, I.; Tahat, M. Phosphorus regulates osmotic potential and growth of African violet under in vitro-induced water deficit. J Plant Nutr 2000, 23, 759 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilbeam, DJ.; Cakmak, I.; Marschner, H.; Kikby, EA. Effect of withdrawal of phosphorous on nitrate assimilation and PEP carboxylase activity in tomato. Plant Soil 1993, 154, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Engels, C. Role of mineral nutrients in photosynthesis and yield formation, in Rengel, Zn Mineral Nutrition of Crops: Mechanisms and Implications; The Haworth Press: New York, USA, 1999; pp. 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, C.; Van-Montagu, M.; Inze, D. Superoxide dismutase and stress tolerance. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol Biol 1992, 43, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, EF.; Osswald, W. Mechanism of oxygen activation during plant stress. Proc. Royal Soc. Edinburgh, Section-B 1994, 102, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, CH.; Lelandais, M.; Kunert, KJ.; Gadgil. Photooxidative stress in plants. Physiol Plant 1994, 92, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengel, K.; Kirkby, EA.; Kosegarten, H.; Appel, T. The soil as a plant nutrient medium. In Principles of plant nutrition; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2001; pp. 15–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sen Gupta, A.; Berkowitz, GA.; Pier, PA. Maintenance of photosynthesis at low leaf water potential in wheat. Plant Physiol 1989, 89, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangakkara, UR.; Frehner, M.; Nosberger, J. Effect of soil moisture and potassium fertilizer on shoot water potential, photosynthesis and partitioning of carbon in mungbean and cowpea. J Agron Crop Sci 2000, 185, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustr, M.; Soukup, A.; Tylova, E. Potassium in root growth and development. Plants 2019, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, E.; Tadesse, M.; Asefa, A.; Admasu, R.; Shimbir, T. Determination of optimal irrigation scheduling for coffee (Coffee arabica L.) at Gera, South West of Ethiopia. International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences 2021, 7(1), 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintgens, J.N. Coffee: growing, processing, sustainable production. A guidebook for growers, processors, traders, and researchers; WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.O.; Arruda, V.R.S.D.; Barbosa, F.R.S.; Firmino, M.W.M.; Pedrosa, A.W.; Cunha, F.F.D. Water Management of Arabica Coffee Seedlings Cultivated with a Hydroretentive Polymer. Agronomy 2025, 15(1), 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A.; Haile, M.; Tesfaye, M. Coffee-based agroforestry systems for enhancing ecosystem services and resilience to climate change in Ethiopia. Sustainability 2019, 11(3), 683. [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren, M. Combined effects of shade and drought on tulip poplar seedlings: trade-off in tolerance or facilitation? Oikos 2000, 90(1), 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaast, P.; Somarriba, E. Trade-offs between crop intensification and ecosystem services: The role of agroforestry in coffee agroecosystems. Agricultural Systems 2014, 134, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, P.C.; Ribeiro Junior, W.Q.; Ramos, M.L.G.; Lopes, M.F.; Santana, C.C.; Casari, R.A.D.C.N.; Brasileiro, L.D.O.; Veiga, A.D.; Rocha, O.C.; Malaquias, J.V.; Souza, N.O.S. Multispectral Images for Drought Stress Evaluation of Arabica Coffee Genotypes Under Different Irrigation Regimes. Sensors 2024, 24(22), p7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).