4. De Facto to In Silico Progression—The Advance of the LLM Family

Conversely, the proposal for a LLM family has a much shorter history, having itself developed from the previously used similar term ‘bacterial luciferase family’, introduced in 2004 by Aufhammer

et al. [

24]. Despite the then current biochemical knowledge confirming that all known bacterial luciferases are heterodimeric oxybiotic FMN-dependent bioluminescent enzymes, the term was chosen to correlate a small number of previously recognised homodimeric anoxybiontic F

420-dependent enzymes essential to promote methanogenesis by non-bioluminescent anaerobic prokaryotes such as

Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum [

25]. Focussing on exemplar deazaflavin-dependent enzymes that could be sufficiently highly purified, Aufhammer

et al.’s. initial 2004 stud

y succeeded in establishing the crystal structure of the homodimeric secondary alcohol dehydrogenase Adf from

Methanocellus thermophillicus. They quickly followed this up by establishing the crystal structure of the homotetrameric methylenetetrahydromethanopterin reductase bMer from

Methanosarcina barkeri [

26]. Further, despite being of limited relevance (

vide supra), in both cases Aufhammer

et al. made specific reference to significance of the shared similarity of the (β/α)

8 TIM-barrel structures of these anoxybiontic enzymes with the established crystal structure of the oxybiontic luciferase from

V. harveyi [

19] to substantiate his proposal for the bacterial luciferase family

Following Aufhammer

et al.’s initial proposal, the related concept of a larger LLM family to collate an expanded group of deazaflavin- and flavin-dependent enzymes subsequently evolved out of a 2010 study by Selengut and Haft [

5]. They developed an

in silico phylogenetic profiling programme (PPP) based on the known genomic information for the biosynthetic pathway enzymes for F

420 present in the facultative anaerobic prokaryote

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other related actinobacteria. The outputs suggested by PPP were then reviewed with the aim of constructing defining protein families based on full-length multiple sequence alignments. This resulted in the identification of a total of 63 top hits belonging to three homology families, each of which included known (deaza)flavin-binding proteins from archaea, actino- and other eubacteria. Because one of the entries in the largest homology family (44 entries) was the luciferase from

V. harveyi, all 44 were collectively named the LLM family. It comprised either F

420- or FMN-dependent enzymes exhibiting differing degrees of similarity to

V. harveyi luciferase based on further analysis using Selengut and Haft’s additional SIMBAL sequence analysis tool. The resultant data indicated that the larger subset of the LLM family comprised anoxybiontic F

420-dependent redox enzymes that deploy the reduced deazaflavin as a prosthetic group tightly bound within the TIM-barrel fold. The remainder were all oxybiontic enzymes. Of these, with the exception of the atypical monooxygenase from

Acinetobacter baumanii that can function equally effectively with both FMNH

2 and FADH

2 [

27], the others were monooxygenases that bind FMNH

2, sourced from a separate flavin reductase, as an active site-bound cosubstrate. Relevant data for the LLM family (short name Bac_luciferase) was subsequently lodged on-line with the intention that it would be further developed into the continuously updated catalogue InterPro IPRO036661 (Pfam PF0296, PROSITE PD016048, SCOP2, and 1nfp).

When considering the LLM family from a conventional biochemical standpoint, the FMN-dependent monooxygenases are the better characterised subset. In addition to the bacterial luciferases (EC 1.14.14.3;

vide supra), the easily purified 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase from

Acinetobacter baumanii (EC 1.14.14.9 [

27]), alkanesulfonate monooxygenase (SsuD) from

Escherichia coli (EC 1.14.14.5; [

28]), and nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase (NTA-MO) from

Chelatobacter heinzi (EC 1.14.14.10 [

29]) have each been extensively researched (

vide infra). While all of these oxybiontic enzymes share much common biochemistry, the bacterial luciferases are unique in being the only bioluminescent members of the entire LLM family. Although historically less well studied, a number of recent reviews have helped considerably to consolidate the known biochemistry and enzymology of several F

420-dependent members of the LLM family [

11,

30], confirming some idiosyncratic mode of action characteristics. The two predominant enzyme types are methylene-H

4MPT reductases (MERs) and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenases (FGDs). In strict contrast to the FMN-dependent subset which are oxybiontic enzymes that deploy the flavin as a cosubstrate, the F

420-dependent subset are anoxybiontic redox enzymes that deploy the deazaflavin as an active site-bound prosthetic group/cofactor. In turn, these significant functional differences between the F

420-dependent and FMN-dependent subsets of the LLM family provide directly relevant perspectives that resonate with the previously raised questions concerning the validity of the currently constituted LLM family (

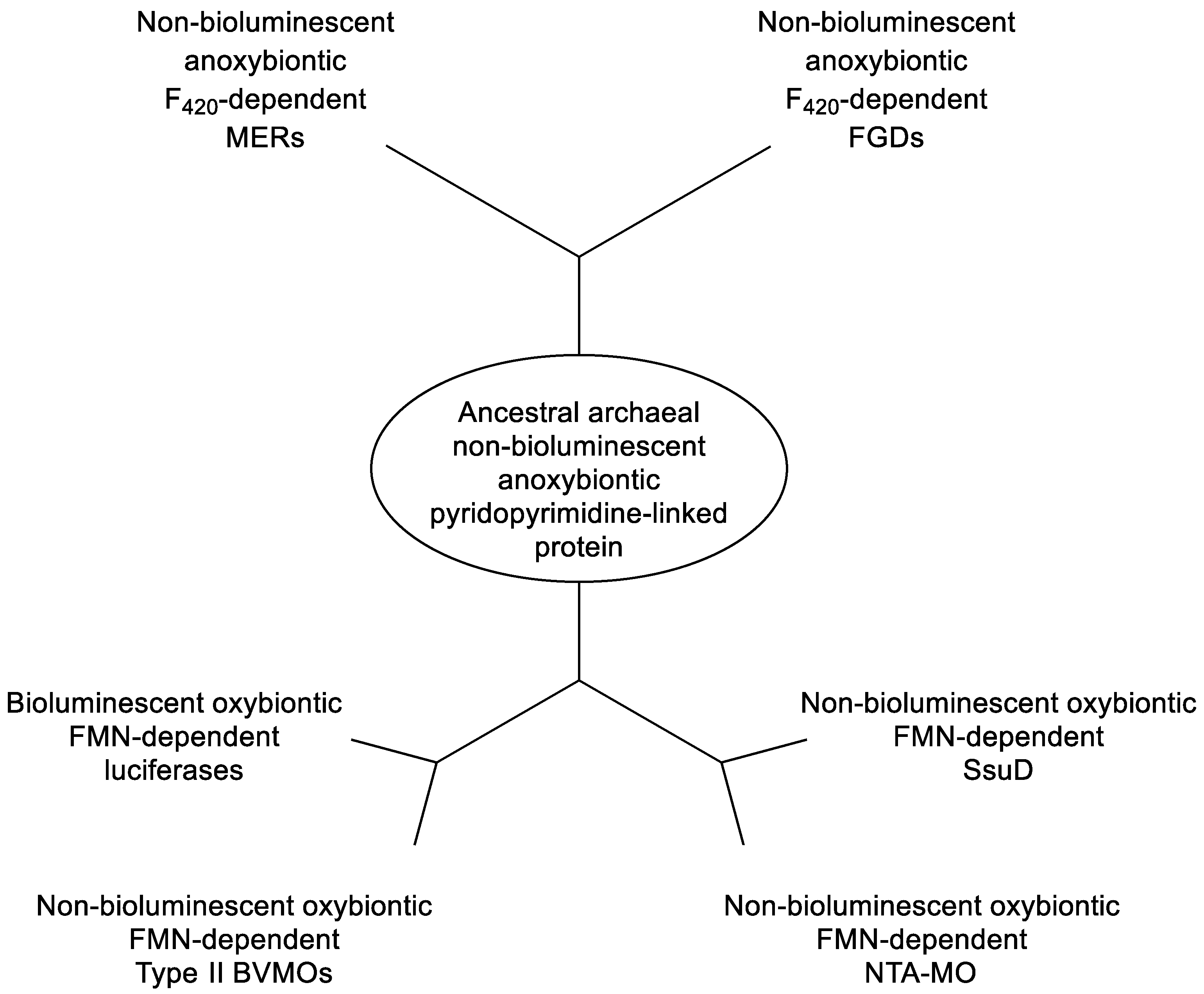

vide supra). Interestingly, two recent reviews focussed on relevant i

n silico issues have both commented on the difficulty of bringing together these two diverse groups of enzymes that were shown by molecular evolution profiling to have diverged from a common ancestor [

4,

31]. Viewed from a functional perspective, equivalent inferred divergent evolutionary relationships of the LLM family members can be suggested (

Figure 2) taking into account the biochemical characteristics of bioluminescence vs non-bioluminescence, FMN- vs F

420-dependence, and oxybiontic vs anoxybiontic dependency. The differential biochemical relationship to dioxygen itself reflects the ancient defining impact that resulted from the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis in the ancestors of modern cyanobacteria, an outcome that served to transform the environmental landscape dramatically and irreversibly [

32]. These divergent relationships and associated epistasis (evolutionary entrenchment; [

33,

34,

35,

36]), argue strongly that the current concept of a unified luciferase-like family is misleading, and should be replaced by separate terminologies that clearly signal the significant biochemical differences between the two diverse groups of enzymes. While the descriptor ‘F

420-dependent oxidoreductases’ accurately serves such a role for the predominant non-bioluminescent anoxybiontic subgroup, reviewing in greater depth the development of our contemporary understanding of the biochemistry of the bioluminescent and non-bioluminescent FMN-dependent monooxygenases will serve to identify an equivalent descriptor that suitably reflects the distinct unifying functional characteristics of the smaller oxybiontic subgroup.

5. The Emergence of a Functional Understanding of the Bacterial Luciferases

It was mankind’s enduring fascination with the phenomenon of bioluminescence, traceable back to earliest recorded observations of ‘cold fire’ by the Ancient Greek philosophers Aristotle and Pliny the Elder [

37], that inevitably resulted in the luciferases being the first FMN-dependent monooxygenases to be fully characterised biochemically. However, the current detailed understanding has a long and chequered history that has included a number of significant changes in both perception and nomenclature along the way. While Dubois’s pioneering1887 luciferin-luciferase research was eventually confirmed nearly four decades later by E. Newton Harvey using hot- and cold-water extracts of various species of fireflies [

38], serial attempts throughout the first half of the 20th century to conclusively demonstrate bioluminescence with equivalent extracts of various relevant bacteria all reported negative results [

37]. However, finally in 1953 bioluminescence was demonstrated but only after specifically adding NADH to a cell-free extract of the luminous bacterium

Achromobacter (=

Vibrio) fischeri [

39]: further, the recorded spectrophotometric changes suggested an undefined involvement of flavin nucleotide biochemistry. A flurry of research activity then quickly confirmed that bioluminescence by the system was stimulated a further 7-fold by the combined addition of FMN [

40] plus an extract sourced from powdered kidney cortex termed ‘kidney cortex factor’ [

41]. KCF was then subsequently identified as hexadecanal [

42], an authentic sample of which was shown to substitute for KCF in promoting bioluminescence in the cell-free extracts of the bacterium. Additional directly related research then further confirmed that hexadecanal could be substituted with any one of the series of C7 to C15 saturated straight-chain aldehydes, albeit with varying degrees of effectiveness: in each case, production of the corresponding carboxylic acid was confirmed [

43]. Collectively, this series of outcomes served to generate the consensus seminal proposal that contra to Dubois’s suggestion that ‘luciferase’ was a single functional entity (

vide supra), the activity of this novel bacterial system resulted from two separate cooperating enzyme systems - an FMN reductase and a separate biooxygenating enzyme which jointly promoted flavin-dependent bacterial bioluminescence [

44].

This important outcome from seven decades ago represents the origin of the recognition that bacterial luciferases function biochemically as two-component oxygen-dependent enzymes (TC-ODEs). In turn this further served to distinguish the

V. fischeri luciferase from ‘mushroom phenolase’, a contemporaneously reported but clearly functionally different single-component monooxygenase [

45]. While the TC-ODE concept remains equally valid to this day, the suggestion that it could serve as a possible descriptor to collate the bacterial luciferases and the other related two-component FMN-dependent monooxygenases is deficient because it fails to convey other relevant definitive elements of functional information.

The next sequence of important developments that led to a more comprehensive understanding of bacterial luciferases were all greatly influenced by the outcomes of a concerted programme of relevant structural and functional research initiated by the American biochemist Woodland Hastings, a colossus in the field of bacterial bioluminescence. His decade-long studies collectively served to define the molecular mode of action of the bacterial luciferases. From a structural point of view, his initial seminal contribution established that the O

2-dependent component of the luciferase activity detected

V fischeri (LuxAB

Vf) was a 1:1 α/β heterodimer [

46], an outcome that has proved to be a characteristic of all other subsequently studied bacterial luciferases [

21]. Functionally, comparisons with existing precedents [

47] enabled him to further propose that the dimeric biooxygenating protein should be formally classified as a monooxygenase. Additionally, an extensive spectrophotometric study [

48] undertaken in the presence and absence of the thiol group inhibitors sodium arsenite and iodoacetic acid encouraged Hastings to advance a proposal that flavin-dependent peroxidation of the biooxygenating enzyme itself would prove to be a key feature of bacterial bioluminescence. However, the biochemistry of flavins is complex as reflected by the uncertainty that has thwarted efforts to understand relevant mechanisms [

9]. Hastings’ initial suggestion was that the sole role of FMNH

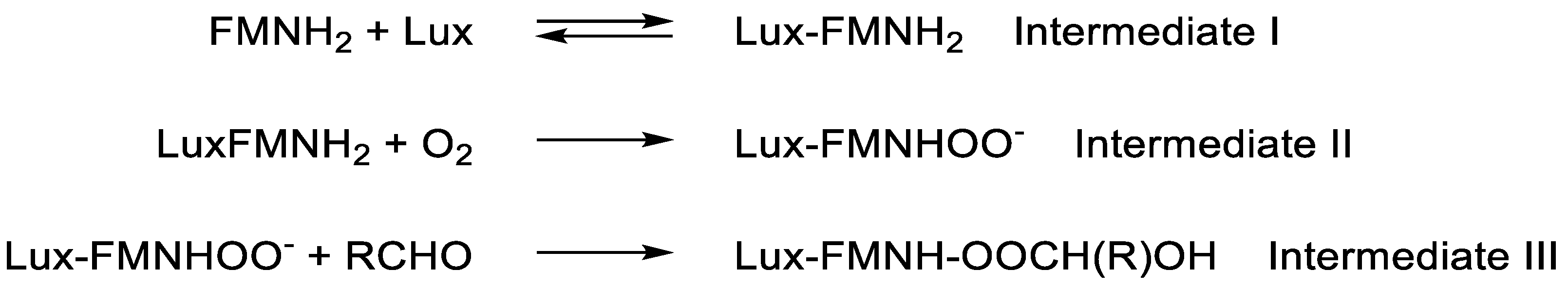

2 was to reduce a cysteine-cysteine disulfide bridge of the α-subunit of luciferase to generate the equivalent dithiol enzyme that he termed Intermediate I. Subsequent peroxidation of one of the resultant thiol groups by dioxygen would then yield Intermediate II, which further interacted with the aldehyde substrate to generate the transitory unstable Intermediate III. Finally, the rapid decay of Intermediate III resulted in both the emission of visible light and a return of the luciferase to a disulfide-bridged protein. Concommitantly, a significant feature of this initial 1964 proposal was the absence of any suggested direct involvement of the flavin cosubstrate in the relevant aldehyde oxygenation step. However, after further extensive studies with more highly purified enzyme activities isolated from the same bacterium, Hastings then put forward a significantly different proposal (

Figure 3; [

49]) that redefined the roles of FMNH

2, luciferase, and Intermediates I - III.

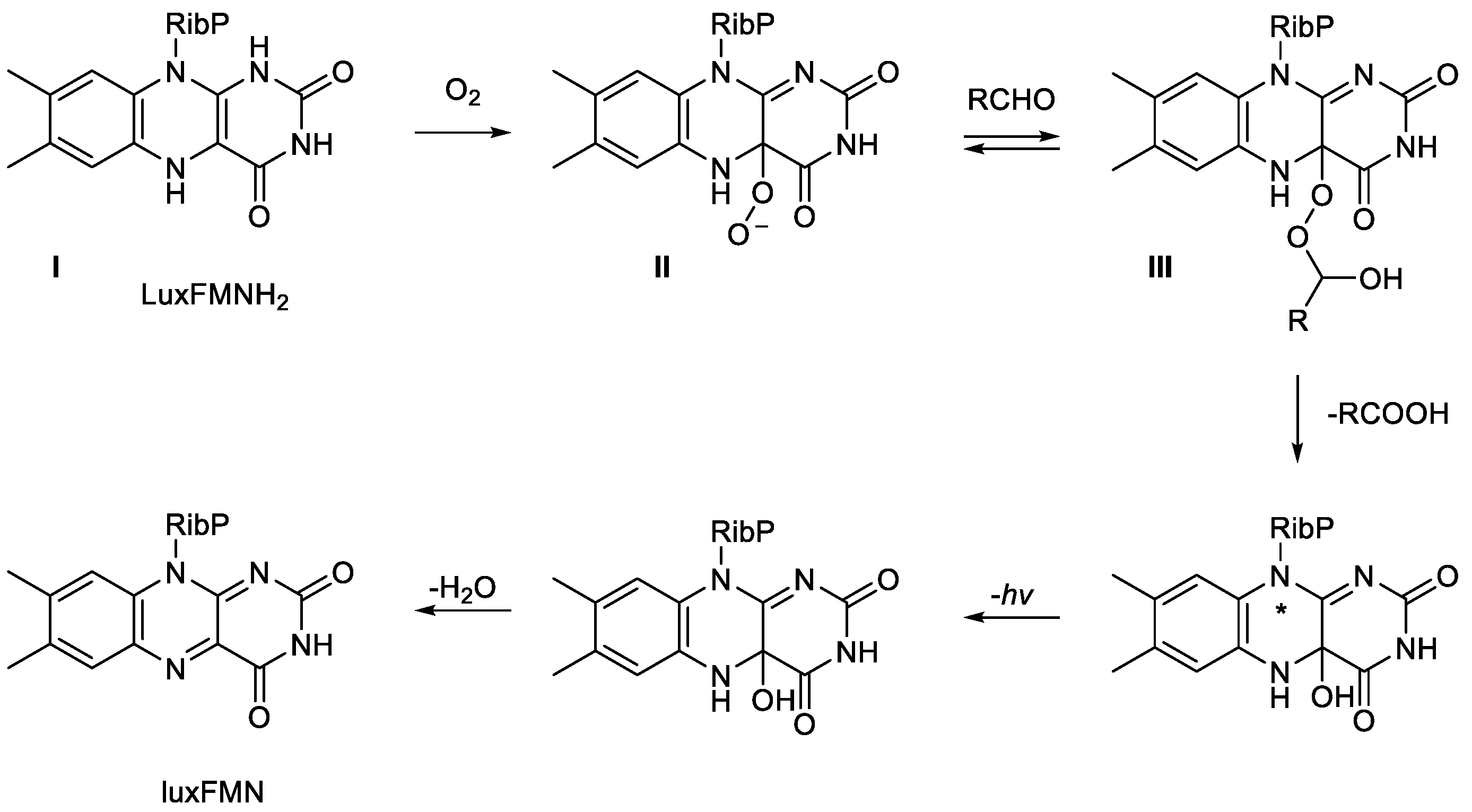

The novel feature of this proposal was that for the first time a specific defined role was proposed for peroxidation biochemistry of the FMNH

2 bound as a cosubstrate in the active site of the luciferase. It was envisaged that the biooxygenating subunit functioned with the reduced flavin nucleotide delivered by the FMN reductase to generate Intermediate I, which then reacted directly with dioxygen to generate a key nucleophilic peroxyflavin corresponding to Intermediate II. Further active site interaction with the aldehyde substrate then generated the transitory unstable Intermediate III. Convinced of the validity of the newly defined roles of each of the Intermediates in this revised outline schematic, Hastings and Eberhard then deployed an extensive stopped-flow spectrophotometric kinetic study to refine and expand these proposals further (

Figure 4; [

50]). They reiterated the key role played by the formation of Intermediate II, which they chemically characterised more fully as a C(4a)-peroxyflavin anion. In turn, the anion then served to directly react with n-hexadecanal, the archetypal aldehyde substrate of the luciferase, thereby forming a C(4a)-peroxyhemiacetal (Intermediate III). Intermediate III then decomposes to release the corresponding carboxylic acid and an excited state of the C(4a)-hydroxyflavin intermediate, which in turn emits blue-green light on returning to the ground-state species. Significantly, this proposed biochemistry that characterises the emission of visible light by bacterial luciferases remains valid nearly five decades later [

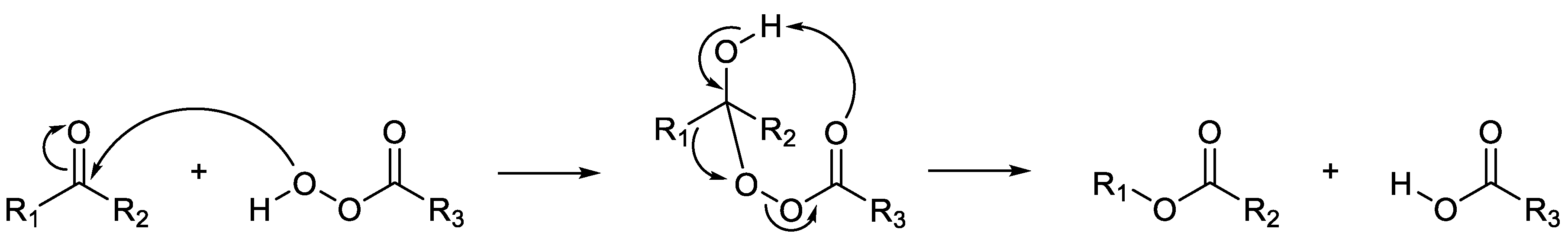

51]. Hastings considered that this proposed multi-step mechanism bore some similarity to the schematic previously suggested by Rudolf Criegee in1948 to explain the abiotic oxidation of ketones to their corresponding esters by peracids (

Figure 5; [

52], a chemical reaction first reported by Adolf von Baeyer and Victor Villiger in 1899 [

53]. Criegee’s model envisaged a chemical oxidation that resulted in the cleavage of the bond between a carbonyl carbon and a neighbouring carbon atom, followed by the subsequent insertion of an oxygen atom. By analogy, Hastings’ proposed LuxAB

Vf luciferase model deploys a C(4a)-peroxyflavin intermediate to biooxidise n-hexadecanal to the corresponding carboxylic acid.This suggested mechanism comprised a progressive sequence of electron transfers and rearrangements that involved the cleavage of the bond between the terminal carbon and hydrogen atoms of the aldehyde. While acknowledging that his proposal did differ from Criegee’s model in some respects, Hastings was sufficiently persuaded in his own mind to commence referring to bacterial luciferases as Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases (BVMOs).

6. Beyond Bacterial Luciferases—The Discovery of Functionally Related Non-Bioluminescent Monooxygenases

In advancing his radical FMN reductase plus BVMO-based proposal, Hastings received considerable encouragement from the eminent biochemist Irwin Gunsalus, a long-standing friend from when Hastings was appointed an Associate Professor in the Biochemistry Department at the University of Illinois by Gunsalus in the 1950s. Gunsalus, a renowned authority on multiple aspects of microbial biooxygenation [

54], could see some directly relevant parallels between Hastings’ newly proposed two-component BVMO-based luciferase biooxygenation strategy and some of his own prior research. Gunsalus had previously reported that the addition of FMN and NADH to a combination of two inducible activities sourced from a cell-free extract of the non-bioluminescent camphor-grown bacterium

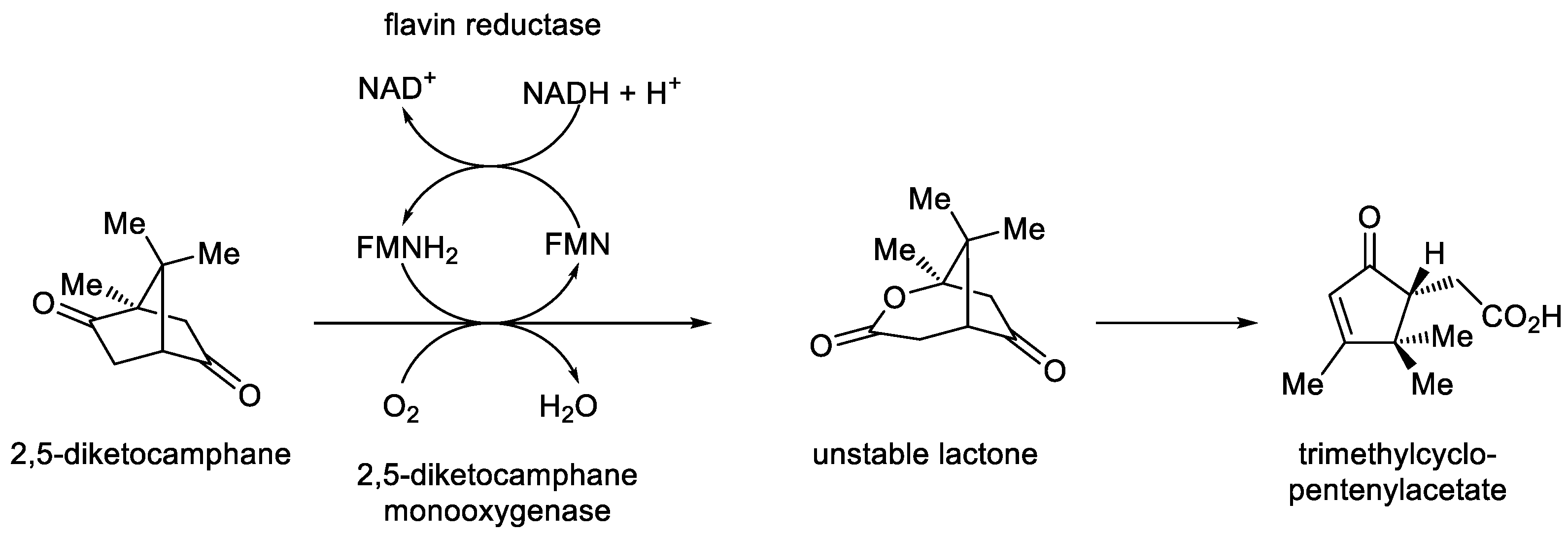

Pseudomonas putida promoted the biooxygenation of 2,5-diketocamphane, a key intermediate of the (+)-camphor degradation pathway, to the corresponding chemically unstable 2-oxa-lactone (

Figure 6; [

55]). Gunsalus initially termed the concerted outcome ‘cyclic lactonization by a ketolactonase’, specially referring to the initiating flavin reducing activity as an NADH-dependent flavin reductase, which served to generate the FMNH

2 that facilitated lactone formation by the complementary monooxygenase activity. Following additional confirmatory studies, Gunsalus subsequently commenced referring to the biooxygenating activity from camphor-grown

P. putida as ‘2,5-diketocamphane monooxygenase, the first confirmed biological Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase’ [

56]. Acknowledging Gunsalus’ significant encouragement and intellectual support, Hastings was sufficiently emboldened to then propose this correlation between the LuxAB

Vf and 2,5-DKCMO as the first indirect evidence of a functional association between the bioluminescent enzyme and another mechanistically-related but non-bioluminescent bacterial enzyme [

57]. However, notable in this respect, and with particular relevance to this Review, it is highly significant that neither eminent scientist ever directly referred to 2,5-DKCMO as a luciferase-like monooxygenase. Possibly because of the radical nature of his proposal, it was notable that Hastings’ rhetoric did include a caveat alluding to the mechanistic differences between the two activities, and indeed in a subsequent study undertaken with LuxAB

Vf and various flavin analogues, he reported evidence for an intermolecular electron exchange that was not compatible with a Baeyer-Villiger mechanism [

58]. Contrastingly, some further significant elements of support for Hastings’ two-component BVMO-based proposals for the mode of action of bacterial luciferases were advanced in studies undertaken in subsequent years.

Firstly, in 1983 Suzuki

et al. [

59] used an established radiolabelling technique for characterising monooxygenases [

60] to confirm the BVMO-type outcome from using

18O

2 to promote the biooxygenation of dodecanal by cell-free extract of the bioluminescent bacterium

Photobacterium (=

Vibrio)

phosphoreum. The combined action of the flavin reductase and monooxygenase activities resulted in one atom of molecular oxygen being inserted directly adjacent to the carbonyl group of dodecanal, thereby generating lauric acid: significantly, the amount of acid formed was confirmed to be directly proportional to the amount of light emitted:

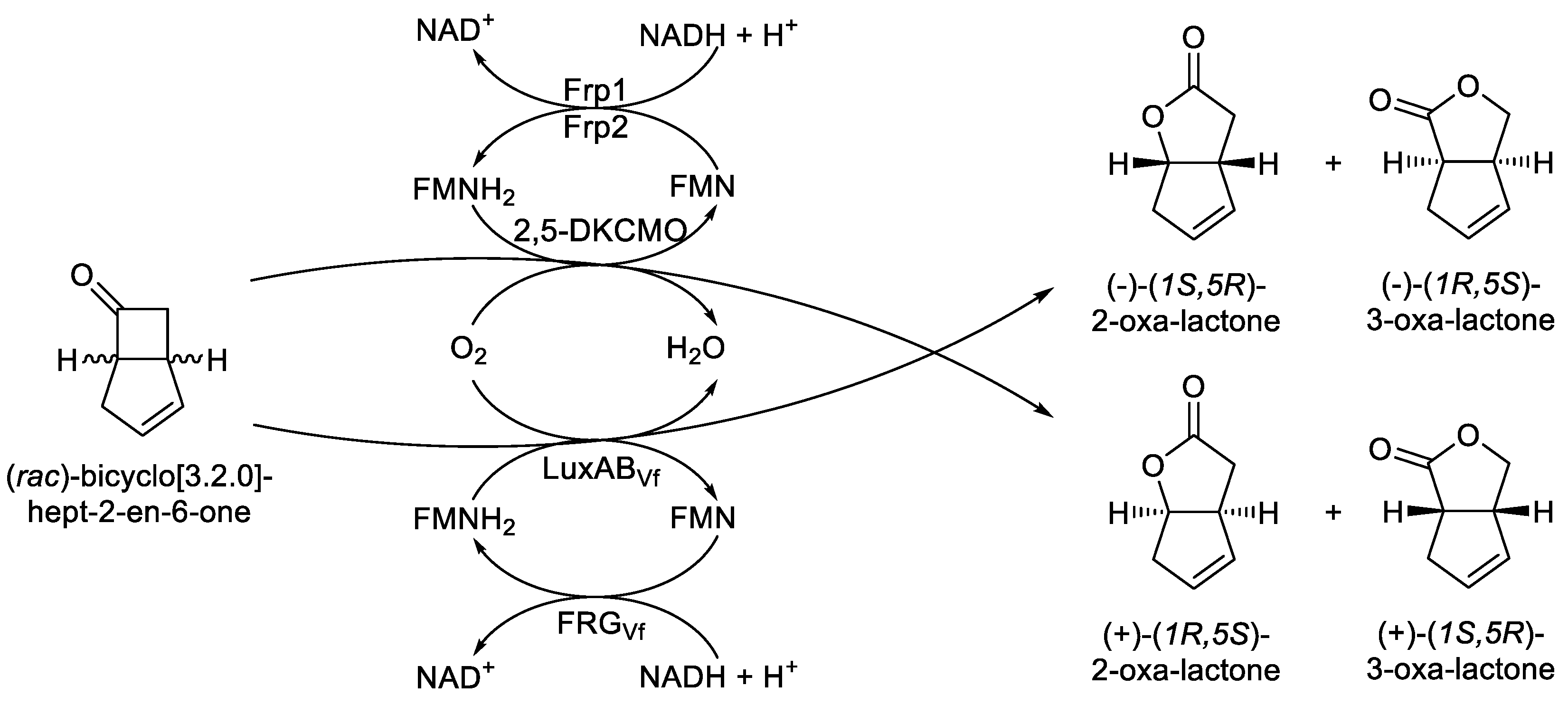

Then just over a decade later, strong direct evidence of the functional correlation between a bacterial luciferase and an acknowledged bacterial BVMO emerged from a related series of studies undertaken at the University of Exeter in the 1990s [

61,

62] which focussed on extending Gunsalus’pioneering studies with 2,5-DKCMO from camphor-grown

P. putida [

55,

56]. Significantly, the Exeter research confirmed that the ketone (

rac)-bicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-one was biooxygenated to a mixture of the corresponding (+)-2-oxa- and (+)-3-oxa-bicyclo[3.3.0]-oct-3-en-7-one lactones by part-purified preparations of the CAM plasmid-coded 2,5-DKCMO functioning in cooperation with the native chromosome-coded flavin reductase activities (

Figure 7), subsequently confirmed as Frp1 and Frp2 [

63]. A key 1997 Exeter University study undertaken with LuxAB

Vf of

Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744 demonstrated that when a similar part-purified preparation of the

luxAB chromosome-coded luciferase retaining some FRG

Vf, the native flavin reductase activity coded for by the proximal

luxG gene, was challenged with FMN, NADH, and the same bicyclic ketone test substrate, this yielded both corresponding regioisomeric 2-oxa- and 3-oxa-lactones, albeit in the opposite enantiomeric series [

64]. These outcomes, signalling equivalent cyclic lactonizations of the same carbonyl substrate via a BVMO-type biooxidation mechanism by both 2,5-DKCMO and LuxAB

Vf, were significant in that they represented the first direct confirmed functional equivalence between a bacterial luciferase and a corresponding non-bioluminescent bacterial enzyme. As a consequence, both two-component monooxygenases were classed together as FMN + NADH-dependent Type II BVMOs [

62]. This new terminology was introduced specifically to distinguish them from another bacterial lactonizing enzyme, the clearly distinct cyclohexanone monooxygenase (CHMO)

Acinetobacter calcoaceticus [

65], this being an NADPH-dependent single component FAD-bound true flavoprotein consequently classed as the prototype Type I BVMO.

Subsequently, a growing awareness of the potential wider occurrence of bacterial FMN + NADH-dependent two-component monooxygenases then resulted in the late 1990s in the discovery and characterisation of nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase (NTA-MO; EC 1.14.14.10) from

Chelatobacter heinzi [

66,

67,

68], and alkanesulfonate monooxygenase (SsuD); EC 1.14.14.5) from

Escherichia coli [

69,

70,

71], both non-bioluminescent bacteria. NTA-MO is a large (99 kDa) homodimeric enzyme that catalyses the oxybiontic cleavage of one of the C-N bonds of the chelating agent NTA, resulting in the release of glyoxylate. Functionally, it is closely related to EDTA monooxygenase (EDTA-MO; EC 1.14.14.33), a monomeric enzyme isolated from various

Mesorhizobium and

Agrobacterium spp that successively cleaves two of the C-N bonds of the related chelating agent EDTA [

72]. Although a full understanding of the oxybiontic catalytic mechanism of these C-N cleaving enzymes remains to be established, in each case flavin reductase-generated FMNH

2 serves as a cosubstrate in generating corresponding unstable α-hydroxylated intermediates that then degrade spontaneously [

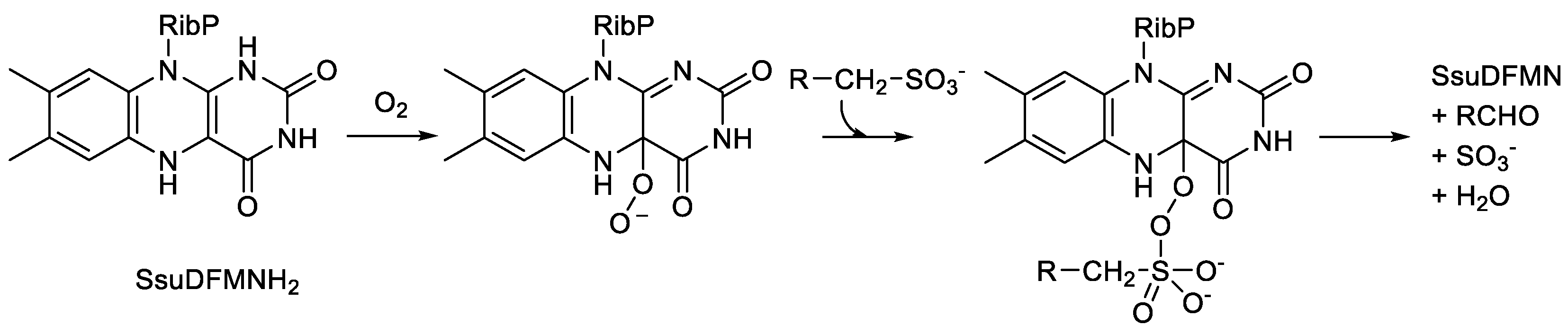

29]. Contrastingly, SsuD is a homotetrameric enzyme that catalyses the oxybiontic cleavage of the C-S bond of short-chain alkanesulfonates homologues to release sulphite and generate the corresponding aldehyde. By deploying a highly purified preparation of the

E. coli enzyme, it has been shown that the catalytic mechanism involves a C(4a)-peroxyflavin intermediate which makes a nucleophilic attack on the sulfonate group thereby forming an initial alkanesulfonate peroxyflavin intermediate (

Figure 8). Subsequently, the flavin adduct undergoes a Baeyer-Villiger-type rearrangement which serves to generate the aldehyde and sulphite products [

73]. Relevant genomic analysis of

E.coli confirmed that the FMNH

2 necessary to promote SsuD monooxygenase activity is principally provided by the flavin reductase SsuE, coded for a neighbouring gene on the same operon [

69]. This proximal location of the

SsuD and

SsuE genes on the same operon of

E.coli probably reflects the logistics of transferring FMNH

2 from SsuE to SsuD. While the equivalent genes that constitute the luciferase activity of

A. harveyi exhibit a similar close genomic relationship [

18], this clearly contrasts with the distal relationship of the equivalent CAM plasmid- and chromosome-located genes that code for the functioning enzymes that constitute the functional 2,5-DKCMO activity of

P. putida [

63].

homologues by SsuD, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Escherichia coli.

Methanesulfonate monooxygenase (MusD; EC 1.14.14.34) is a closely related homotetrameric monooxygenase isolated from

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

74], but notable for being a less catholic activity, with methanesulfonate serving as the principal substrate. Its activity is supported by the FMN-dependent flavin reductase MsuE. Like SsuD, the catalytic mechanism of MusD has been reported to involve a C(4a)-peroxyflavin intermediate [

75], but differing in some detail as a result of methanesulfonate being more reduced than the product formaldehyde. While collectively the outcomes from these various studies on 2,5-DKCMO, SsuD, and MusD suggest that Type II BVMO could be considered as a potential new mechanism-based moniker for the bacterial luciferases and related monooxygenases, it fails to convey either their two-component or FMN-dependent nature, which are both important characteristic features of this family of related enzymes.

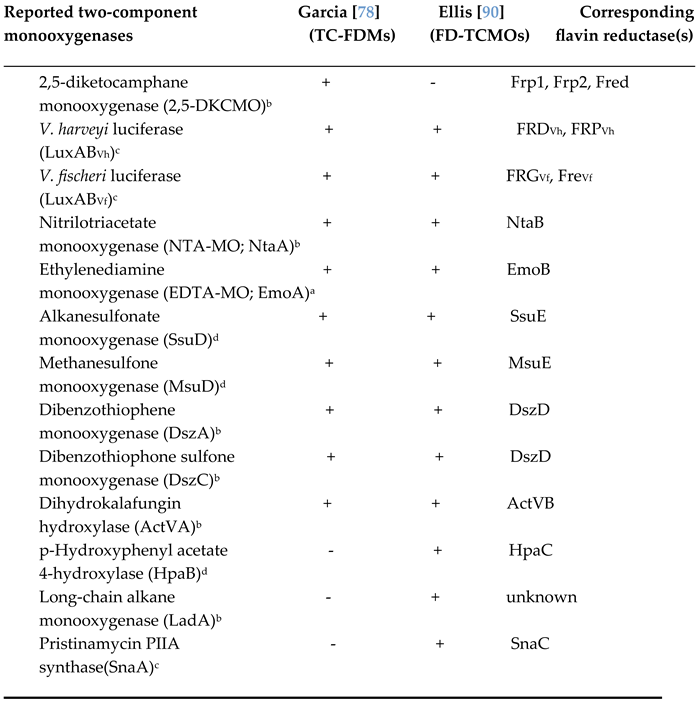

This flurry of activity reporting various bacterial two-component oxybiontic enzymes in the years leading up to the new millennium prompted a further relevant development by José Garcia. Having had prior experience with FAD + NADH-dependent 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase isolated from

E.coli [

76,

77], Garcia recognised the parallels between this enzyme and the growing number of reported FMN + NADH-dependent two-component monooxygenases. He became interested in the possibility that this may signal the existence of other similar microbial enzymes, functioning via FMN-derived C(4a)-(hydro)peroxyflavin biochemistry as what he termed the two-component non-heme flavin-diffusible monooxygenase (TC-FDM) family [

78]. Treating the flavin reductase and monooxygenase subunits separately, he developed BLASTP and BLASTX

in silico analyses of extant data which could be combined to identify both potential FAD + NADH- and FMN + NADH-dependent oxybiontic enzymes. With specific respect to the FMN + NADH-dependent activities, the combined outcome was to confirm that the previously well characterised bacterial luciferases, 2,5-DKCMO, NTA-MO, EDTA-MO, SsuD, and MsuD activities constituted the founder members of the FMN-specific TC-FDM family. Further, he proposed that three additional previously reported enzyme activities (ActVA, DszA, and DszC) should be included in this newly defined grouping (

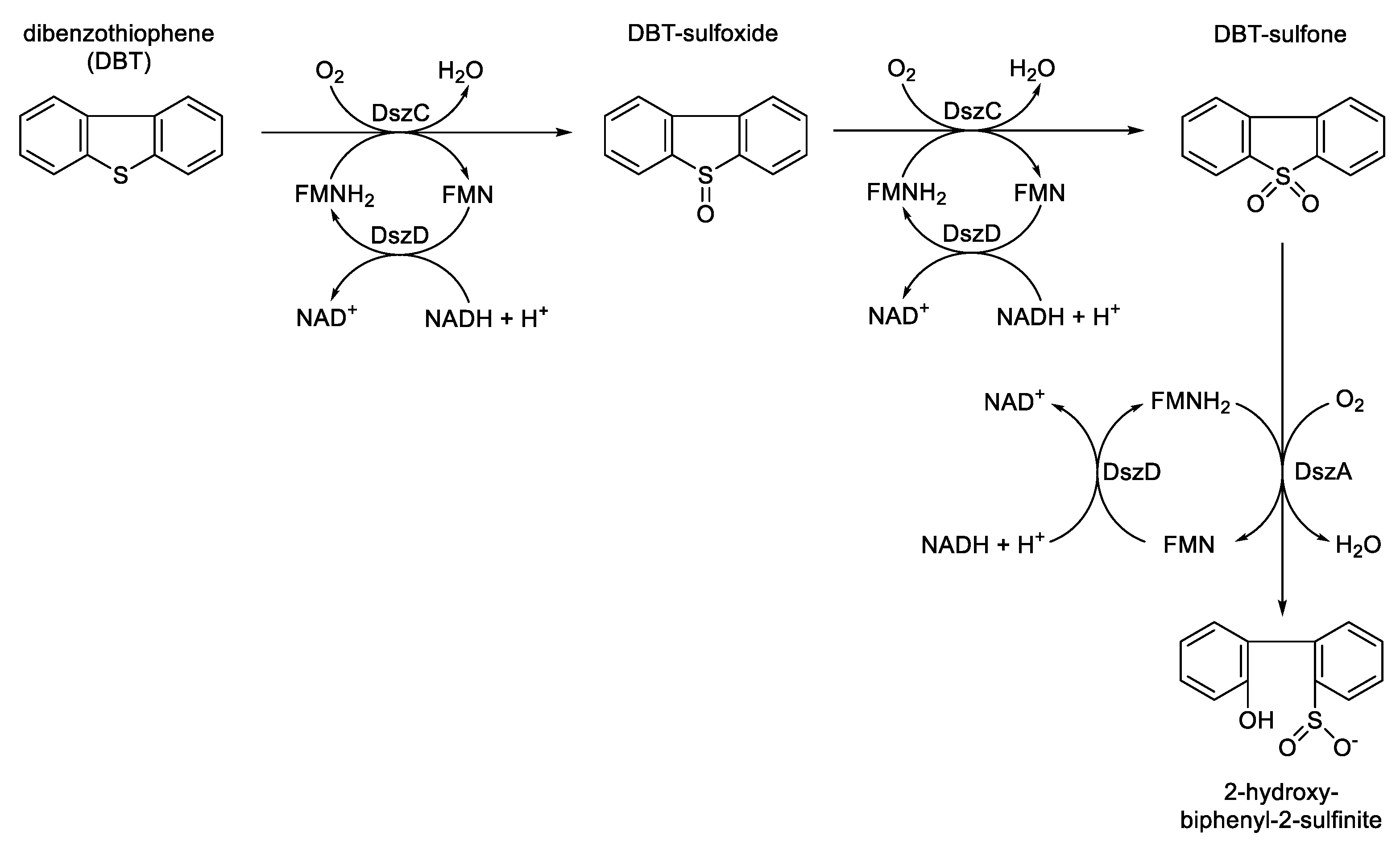

Table 1). Interestingly, Garcia remarked that he considered the bacterial luciferases to be atypical TC-FDMs because they are composed of two structurally different types of monomers. As well as simply expanding the number of recognised FMN-specific TC-FDMs, Garcia’s newly assigned activities introduced further avenues of interest with respect to range of functional biochemistries exhibited by this type of oxybiontic enzyme. DszC (EC 1.14.14. 21) and DszA (EC 1.14.14. 22) are two homodimeric monooxygenases isolated from

Rhodococcus erythropolis [

79] that both shared the same proximally located DszD flavin reductase. They act in concert to progressively metabolise dibenzothiophene (DBT) to 2-hydroxybiphenyl-2-sulfinite (

Figure 9). The intermediary formation of DBT sulfoxide followed by DBT sulfone both introduce sulfoxidation as a new functional role in the portfolio of FMN-specific TC-FDM activities.

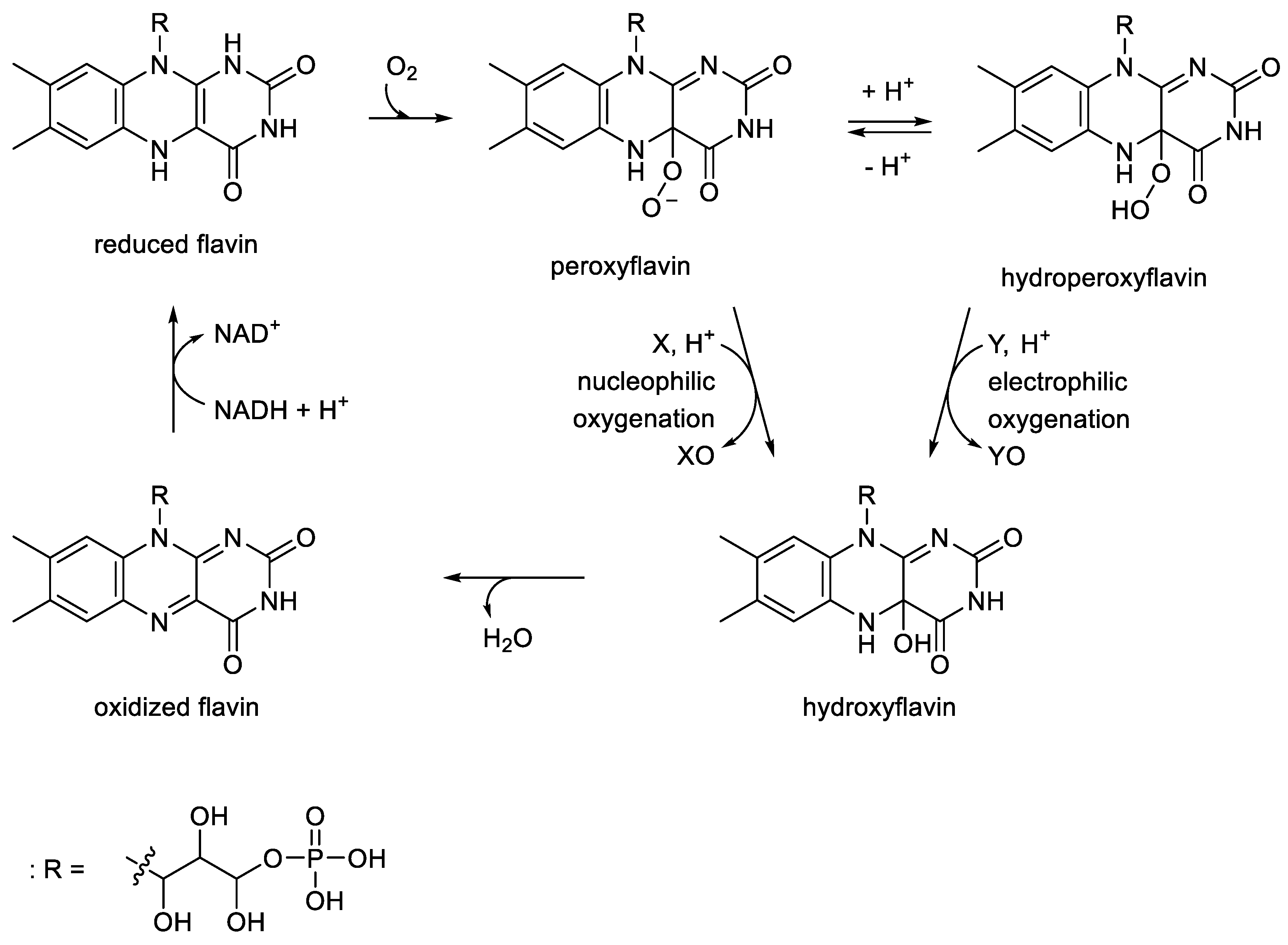

These oxybiontic steps involve two successive electrophilic substitutions by a C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin intermediate (

Figure 10) which clearly contrasts with Hastings’ original proposal that the role of the flavin in bacterial luciferases is to promote nucleophilic substitution by a C(4a)-peroxyflavin intermediate (

vide supra,

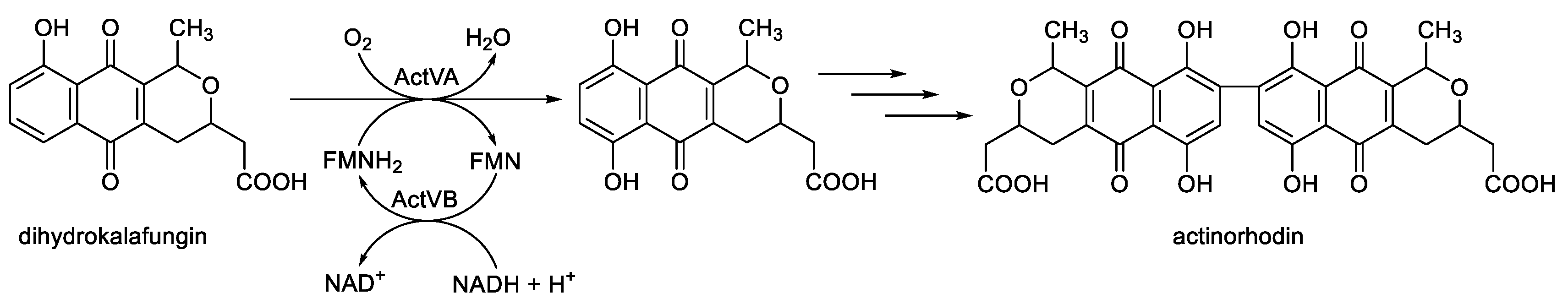

Figure 4). Although less well understood, the ActVA monooxygenase isolated from

Streptomyces coelicolor [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84] is a homodimeric enzyme specifically induced by the bacterium at the onset of secondary metabolism. Together with the distally coded flavin reductase ActBV, it functions as a TC-FDM to hydroxylate dihydrokalafungin (DKF), with the hydroxylated product then serving as a precursor for the synthesis of the polypeptide antibiotic actinorhodin (

Figure 11). Like DszC and DszA, the catalytic reaction mechanism of ActVA is believed to involve an electrophilic substitution, suggesting that the oxygenating intermediate is a C(4a)-hydroperoxyflavin [

85]. Oxybiontic hydroxylation thus further expands the confirmed functional portfolio of the FMN-specific TC-FDMs. Garcia’s recognition of the role of ActVA in the biosynthesis of the secondary metabolite actinorhodin by

S. coelicolor then encouraged him even further to use his combined data screen to speculate whether equivalent then as yet uncharacterised FMN-specific TC-FDMs may function in the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites. This perceptive initiative was undertaken a number of years before the significance of TC-FDMs and other monooxygenases in microbial secondary metabolism was more widely recognised [

86,

87]. One of the more obvious possibilities he suggested was that a TC-FDM may play a key oxybiontic role in the biosynthesis of granaticin by

Streptomyces violaceoruber [

88], this being a polypeptide antibiotic believed to share the same initial pathway to hydroxylated DKF as characterised in

S. coelicolor. Garcia’s development of the concept of the TC-FDMs clearly served a role in bringing together a number of functionally related flavin-dependent monooxygenases. However, by including the undefined term ‘flavin’, it failed to make the important distinction between the relevant FMN-dependent monooxygenases and the corresponding FAD-dependent enzymes that traditionally have been grouped separately [

89].

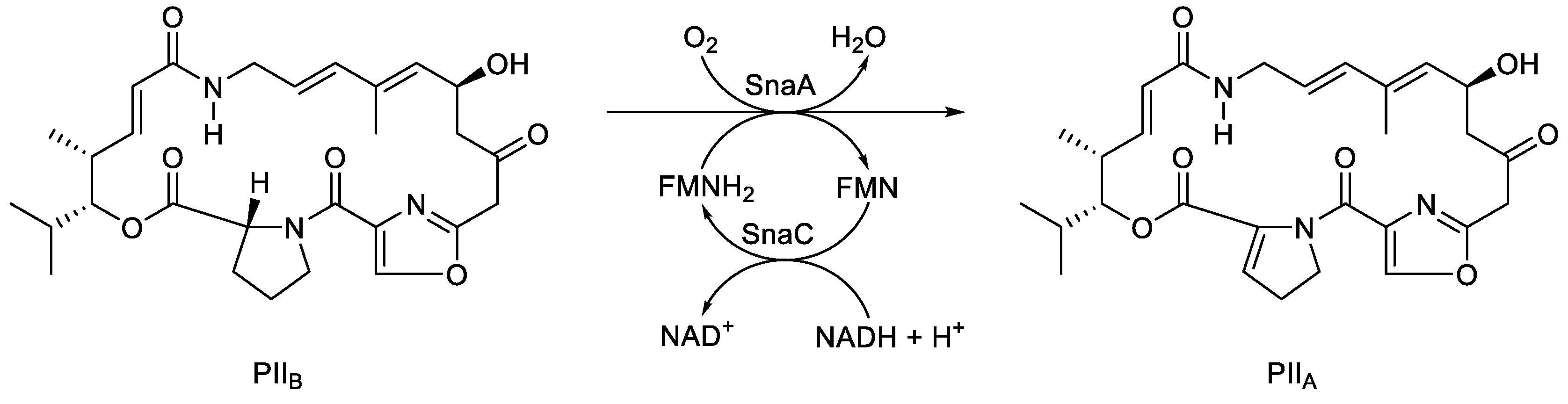

Another decade would then elapse before Holly Ellis [

90] undertook a subsequent, and currently the last, comparative study that considered again both the functional and structural characteristics of the bacterial luciferases in the context of other known related two-component monooxygenases. Ellis introduced her own alternative terminology, the FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase (FD-TCMO) family, to categorise these obligate oxybiontic microbial enzymes listed in her comprehensive review. The functional importance of the flavin cosubstrate was reflected in her equal emphasis on the activities of both the participating flavin reductases and monooxygenases, the first time that such a comprehensive examination of the relevant known reductase enzymes had been conducted. This part of her review provided a valuable explanation of not only the alternative mechanistically different types of flavin reductases known to serve as the partner enzymes for the various FD-TCMOs, but also their relevant structural properties. Like Garcia previously [

78], Ellis emphasised the importance of the FMN-derived C(4a)-(hydro)peroxyflavin intermediate in the biochemistry of the this family of prokaryotic monooxygenases. Ellis’s FD-TCMO catalogue (

Table 1) included a number of activities previously listed as FMN-dependent TC-FDMs by Garcia (

vide supra), although notably absent was 2,5-DKCMO, the well established FMN + NADH-dependent two-component Type II BVMO reported many years previously [

62]. However, Ellis did include three newly proposed FD-TCMOs, each of which exhibited interesting idiosyncrasies. The enzyme PII

A synthase, considered but not included previously by Garcia, is induced during secondary metabolism by a number of different

Streptomyces spp. [

91], It is a two-component bioxygenating activity comprising the monooxygenase SnaA and the flavin reductase SnaC, coded for by two corresponding proximal genes [

92]. Like the bacterial luciferases, the monooxygenase component is an α/β-heterodimer. Atypically, the PII

A synthase-catalysed reaction is not an oxygenation, but an oxidation of the dehydroproline residue of PII

B (

Figure 12) to form the unsaturated cyclic peptolide pristinamycin II

A (PII

A). C2 monooxygenase (

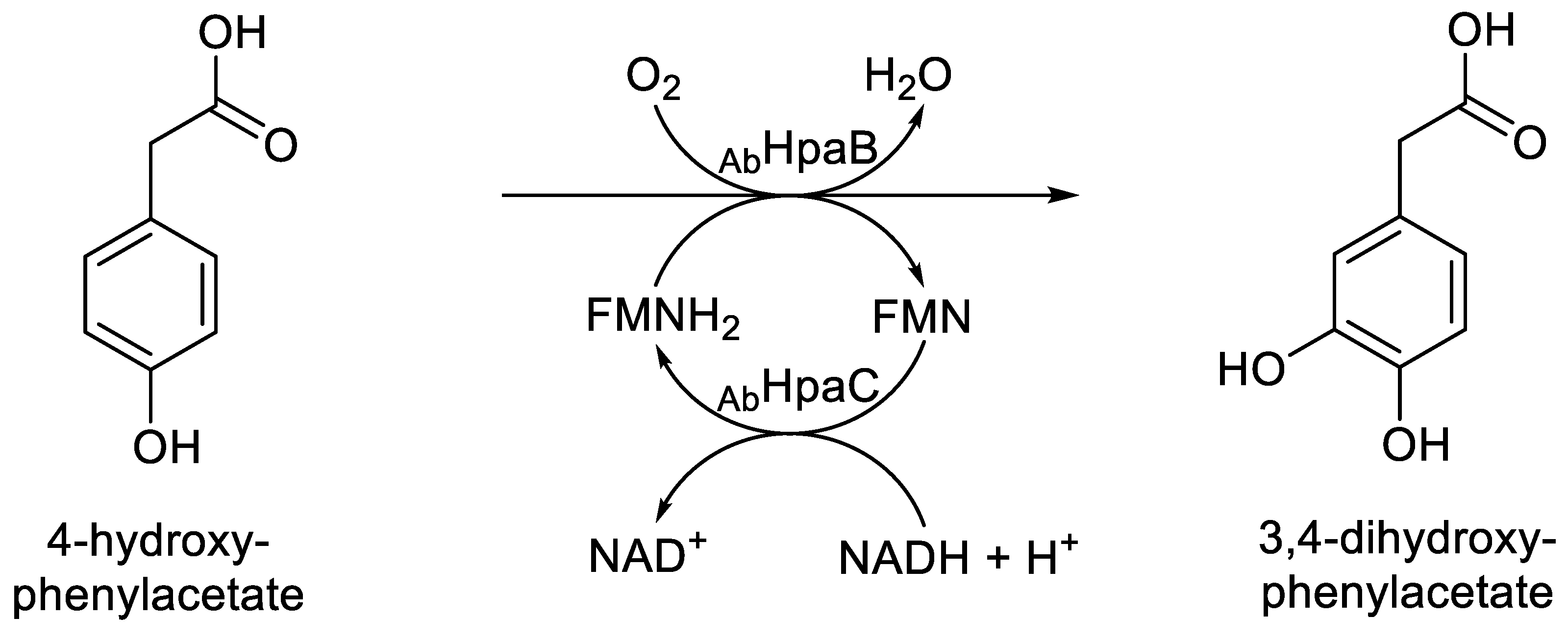

AbHpaB) is the homotetrameric oxybiontic component of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (EC 1.14.14.9), an FD-TCMO isolated from

Acinetobacter baumanii [

93]. Like ActVA, it uses a C(4a)-hydroxyperoxy intermediate-dependent electrophilic mechanism to catalyses the hydroxylation reaction that yields 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl acetate (

Figure 13). However, as first signalled by Selengut and Haft’s 2010

in silico study that originally defined the LLM family (

vide supra; [

5]), it is an atypical two-component monooxygenase. When purified and tested in isolation, it can use either FNMH

2 or FADH

2 equally effectively to catalyses the hydroxylation reaction that yields 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl acetate, although the corresponding native flavin reductase (

AbHpaC) is considered to be FMN-specific [

27]. LadA is a homodimeric monooxygenase from

Geobacillus thermodenitrificans that catalyses the initial reaction in the terminal oxidation pathway of long-chain alkanes (C15-C36) to equivalent primary alcohols [

94,

95]. While

in silico analysis indicated that it is an FMN-dependent monooxygenase closely related to SsuD, significantly no corresponding native flavin reductase activity could be identifed at the time, an outcome reinforced by a subsequent comprehensive review of aliphatic hydrocarbon biodegradability by bacteria [

96]. Accordingly, functional studies with the purified enzyme obligately required the addition of preformed FMNH

2, suggesting further clarification is required for inclusion of LadA with the other characteristic FD-TCMOs

7. What’s in a Name? The Established Value of FD-TCMO as a Moniker, and Its Relevance to Further More Recent Studies

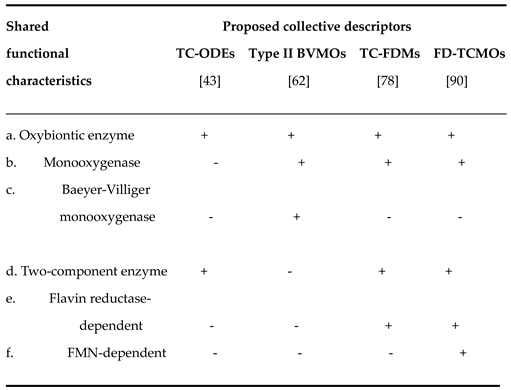

Putting into perspective the last 70+ years of the history of investigating the molecular mode of action of the bacterial luciferases and other directly related enzymes, Ellis’s term FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases (FC-TCMOs), included in her seminal 2010 review [

90], clearly serves as a valuable collective descriptor (

Table 2) for the FMN-dependent subgroup currently included within Selengut and Haft’s luciferase-like monooxygenase (LLM) superfamily [

5]. Compared to the three previously introduced alternatives (TC-ODEs, Type II BVMOs, and TC-FDMs) the FD-TCMOs is notable for providing the most comprehensive and accurate summary of the key biochemical characteristics that unify both the relevant bioluminescent and non-bioluminescent prokaryotic enzymes.

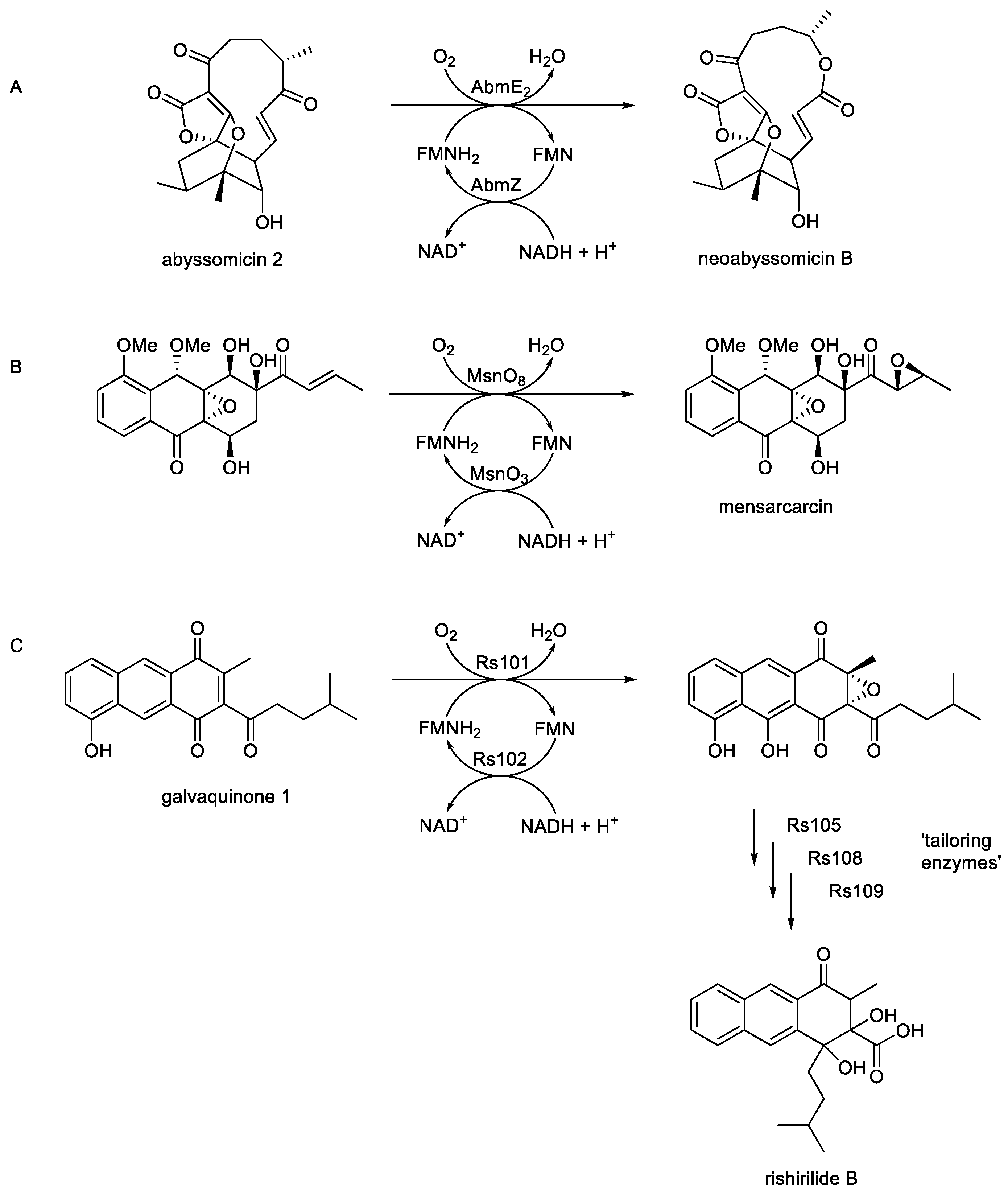

Further support for the representational value of Ellis’s FD-TCMO moniker can be garnered by reviewing a number of post-2010 studies conducted on functionally characterised two-component prokaryotic enzymes that were reported at the time to be LLM homologues. These are oxybiontic enzymes almost exclusively reported to catalyse reactions of secondary metabolism, being induced exclusively during idiophasic growth of the competent bacterial species. Monooxygenases of various different functional types serve a wide variety of real and proposed roles in microbial secondary metabolism [

97], and while some of these activities correspond to extant functionally active proteins, exclusively induced during idiophasic growth, others are encoded in cryptic or silent genes initially detected by

in silico screening [

98,

99]. Considering firstly the relatively few examples of reported idiophasic LLMs that have been extensively studied

in vitro, they all function biochemically in a way that conforms explicitly to Ellis’ definition as FD-TCMOs (

Figure 1A-C). One such bacterial FD-TCMO-catalysed biotransformation has been confirmed as a key fully characterised step in the biosynthesis of the secondary metabolite neoabssyomicin B, a valuable bioactive antibiotic produced during idiophasic growth by various

Streptomyces and

Verrucosispora spp. (

Figure 1A; [

6,

100,

101]). The relevant genes (

abmE2 and

abmZ) have been isolated from

Streptomyces koyangensis SCSIO 5802, over expressed in

E.coli BL21, and the resultant monoxygenase (AbmE2) and flavin reductase (AbmZ) enzymes purified and confirmed to function cooperatively as a two-component NADH + FMN-dependent monooxygenase that efficiently bioxygenates abyssomicin 2 to neoabyssomicin B. In principle, this coordinated activity by AbmE2/AbmZ is equivalent to the cyclic lactonization activity of 2,5-DKCMO from

P. putida first recorded by Gunsalus in the early 1960s (

vide supra; Figure 5), an activity subsequently designated as a Type II BVMO [

62] prior to the introduction of Ellis’s FD-TCMO definition in 2010 [

90]. Similarly, a well researched biooxygenation is a key step in the biosynthesis of the secondary metabolite mensacarcin (

Figure 1B), a proven powerful anti-tumor drug, by

Streptomyces bottropensiss [

7,

102]. By initially constructing cosmid cos2 which included almost the complete type II polymerise synthase gene cluster, and then using selective deletion and complementation in a heterologous expression system, they were able to show that the

msnO3-coded flavin reductase and the

msnO8-coded monooxygenase function as an FD-TCMO to catalyse the final step in the biosynthesis of mensacarcin. Interestingly, this oxybiontic step results in the introduction of an epoxy group into the side chain of the relevant mensacarcin precursor. This outcome is notable, because although there are a very few isolated reports of epoxidation reactions undertaken by monomeric FAD-bound Class I BVMOs such as CHMO [

103], it represents the first time that epoxidation has been reported as an attribute of an FMN-dependent TCMO. While the relevant mechanistic events in the active site of MsnO8 remain currently unknown, epoxidation and carbonate formation are recognised outcomes of some peracid-catalysed chemical Baeyer-Villiger rearrangements [

104,

105]. Related studies undertaken using a similar programme of research with

S. bottropensis [

8] have confirmed that an equivalent biooxygenation catalysed by the concerted activities of Rs101 and Rs102 promotes epoxidation as a key intermediary step in the biosynthesis of rishirilide B, one of a number of tricyclic aromatic Type II polypeptides produced exclusively during idiophasic growth by this bacterium.(

Figure 1C). This consolidates the recognition that some reported LLMs function as confirmed FD-TCMOs in bacterial secondary metabolism.

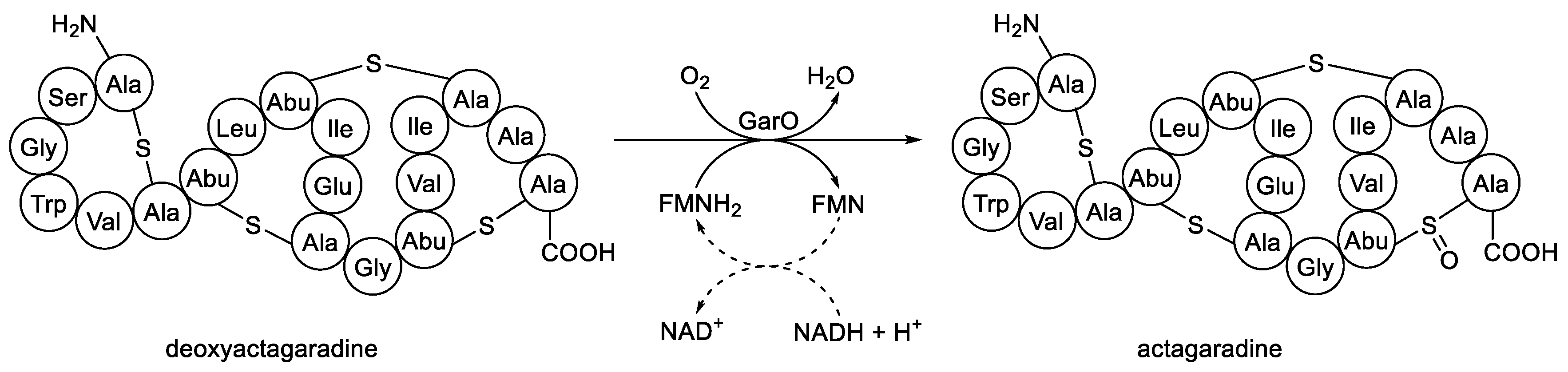

As well as these characterised idiophasic FD-TCMOs for which both participating native enzymes of the functioning partnership have been identified, there are a number of other equivalent candidate activities originally reported as LLMs, but for which there is less definitive evidence for the requisite monooxygenase and/or flavin reductase moieties. An interesting illustrative example is the 2012 study by van der Donk’s research group on the biosynthesis of actagardine (

Figure 14) and related lantibiotic secondary metabolites which included a reported LLM activity [

106]. Actagardine, isolated from

Actinoplanes garbadinensis [

107], is a tetracyclic 19-amino acid ribosomally-synthesised peptide that includes four intramolecular thioether linkages (lanthionine bridges). Prior deletion-based genomic studies [

108] have confirmed that the

garO gene of

A. garbadinensis codes for a corresponding GarO monooxygenase that catalyses the sulfoxidation of the 14-S-19 lanthionine bridge of deoxyactagardine to yield actagaradine, the only known lantibiotic containing a sulfoxide group. Based on their previous success in producing other prokaryotic lanthionone bridge-containing peptides by heterologously expressing the corresponding modification enzymes [

109,

110,

111,

112], van der Donk’s group firstly generated a source of GarO by cloning

garO into a pET28b vector which was then expressed in

E.coli [

106]. The activity was then purified, and confirmed as monomeric by gel filtration. When the purified GarO monooxygenase was incubated with FMN, NADH and deoxyactagardine, and the stopped reaction mixture then analysed, ‘the mass of the resulting … peptide was increased by 16 Da, consistent with the formation of one sulfoxide group’. It was this outcome that prompted Shi

et al.s’ claim [

106]that ‘GarO is a luciferase-like monoxygenase that introduces the unique sulfoxide group of actagardine’. While prior studies have reported sulfoxidation as a confirmed activity of both DszC (EC 1.14.14. 21) and DszA (EC 1.14.14. 22), two FD-TCMOs isolated from

Rhodococcus erythropolis, these are activities with a shared dependency on the same DszD flavin reductase as the obligate source of NADH (

vide supra; Figure 9). However, no native

A. garbadinensis flavin reductase was knowingly included by Shi

et al. in their assay system, nor was the implied involvement of a flavin reductase activity in facilitating their recorded outcome addressed. So from that point of view, the reassignment of the reported sulfoxidation outcome as a definitive FD-TCMO activity remains problematical. In retrospect, it can be speculated that one or more of the known native flavin reductase enzymes of the

E. coli expression system such as Fre

Ec [

113] could have cooperated with the GarO monooxygenase, thereby supporting the recorded sulfoxidation activity by a hybrid FD-TCMO. Such a proposed hybrid FD-TCMO would not be unprecedented, as 2,5-DKCMO was confirmed to function efficiently as a hybrid FD-TCMO when the relevant gene was expressed in

E. coli and the lactonizing activity of the cloned monooxygenase then tested on a range of alicyclic ketones [

114], although again the identity of the relevant flavin reductase(s) was not confirmed. In another recent and more extensively characterised relevant study, the hybrid FD-TCMO concept was confirmed with both purified 2,5-DKCMO and LuxAB

Vf [

115]. Highly purified preparations of both monooxygenases were confirmed to catalyse more efficient lactonization of (

rac)-bicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-one when functioning as hybrid FD-TCMOs coupled with a number of different non-native flavin reductases, including most effectively with FRD

Aa from

Aminobacter aminovorans.

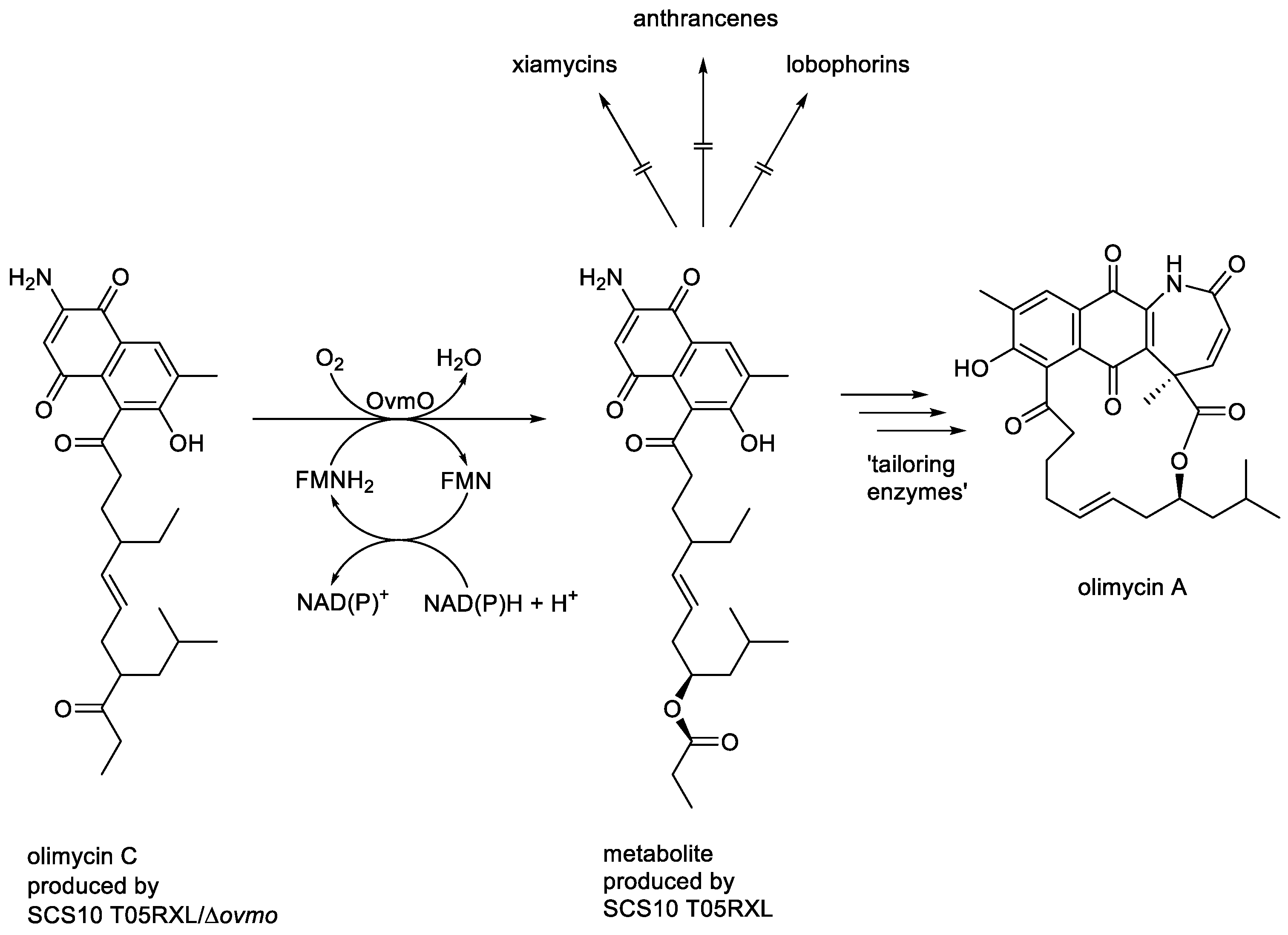

In addition to characterised FD-TCMOs coded for by corresponding genes in normally expressed bacterial genomes, such as SsuD from

E. coli (EC 1.14.14.5 [

28]), the current InterPro IPR0036661 catalogue contains many

in silico-identified entries of proposed LLMs coded for by cryptic genes included in larger clusters corresponding to silent bacterial secondary metabolic pathways. Many of these cryptic genes remain unexpressed, so the functional status of the coded activities is currently not known. One interesting exception is OvmO, coded for by

ovmo present in the normally silent

ovm biosynthetic gene cluster of

Streptomyces olivaceus SCS10 T05 that when activated by metabolic engineering resulted in the production of various lobophorins, anthrancenes and xiamycins [

116]. Subsequently, the silent gene cluster was then mutated and reconstructed to generate both

S. olivaceus SCS10 T05RXL, a triple-deletion strain mutated at the expense of the production of xiamycins, anthrancenes, and lobophorins, but which included an expressible copy of the

ovmo gene, and the corresponding T05RXL/Δ

ovmo strain which was additionaly devoid of the OvmO-coding gene [

117]. After culturing the two reconstructed strains for 8 days in separate aliquots of ISP3 medium, the metabolites present in each spent fermentation broth were isolated and characterised. This established olimycin C as the major recovered metabolite produced by SCS10 T05RXL/Δ

ovmo, whereas the directly corresponding ester was the major recovered metabolite produced by

SCS10 T05RXL, along with detectible traces of the macrocyclic lactone olimycin A (

Figure 15). This outcome prompted

Zhang

et al. to suggest that OvmO is ‘a luciferase-like monooxygenase … that catalyses a Baeyer-Villiger oxidation’. While all subsequent attempts to clone and overexpress

ovmo in

E. coli BL21(DE3) proved unsuccessful, thereby thwarting any attempt to establish the functionality of the monooxygenase directly,

in silico analysis indicated a close relationship to both 2,5-DKCMO from

P. putida, and Rs101 from

S bottropensis, two established FD-TCMOs (

vide supra). As in the case of GarO from

A. garbadinensis [

106], Zhang

et al. gave no evident consideration of the requisite involvement of a complementary flavin reductase activity to support their proposed OvmO monooxygenase activity in strain SCS10 T05RXL, thereby making the reassignment of the reported activity as a definitive FD-TCMO problematical. However, a number of constitutively-expressed flavin reductases have been reported subsequently in

S. olivaceus [

118]. This raises the possibility that the ’Baeyer-Villiger-type oxidation’ reported by Zhang

et al. may have resulted from the expressed OvmO functioning as an FD-TCMO in cooperation with one or more of these native flavin reductases, although this suggestions awaits relevant investigation.

In conclusion, research endeavours undertaken across nearly seven decades, from initial trials with acetone-dried powders of whole bacterial cells in the mid-1950s [

38] to the current use of selective gene deletion and complementation in heterologous expression systems [

8,

102], have served to establish the consensus biochemistry that consolidates the bacterial luciferases and functionally equivalent FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases as a discrete group of prokaryotic oxybiontic enzymes. The value of the corresponding abbreviated descriptor - the FD-TCMOs - is that it succinctly emphasises those canonical biochemical characteristics that serve to unite the group members, and which distinguish them fundamentally from the functionally unrelated anoxybiontic F

420-dependent redox enzymes.

Figure 1.

Key monooxygenase-dependent steps in the biosynthesis of (A) neoabyssomycin B, Song

et al. [

6]; (B) mensacarcin, Maier

et al. [

7]; (c) rishirilide B, Alali

et al. [

8].

Figure 1.

Key monooxygenase-dependent steps in the biosynthesis of (A) neoabyssomycin B, Song

et al. [

6]; (B) mensacarcin, Maier

et al. [

7]; (c) rishirilide B, Alali

et al. [

8].

Figure 2.

Inferred divergent evolutionary relationships of LLM family members taking into account their functional and biochemical characteristics.

Figure 2.

Inferred divergent evolutionary relationships of LLM family members taking into account their functional and biochemical characteristics.

Figure 3.

Hastings’ more developed proposal for the role of peroxidation biochemistry of luciferase-bound FMNH2 in bacterial bioluminescence.

Figure 3.

Hastings’ more developed proposal for the role of peroxidation biochemistry of luciferase-bound FMNH2 in bacterial bioluminescence.

Figure 4.

Hastings’ proposal for a defined role for a luciferase-bound proxide as a key intermediate in bacterial bioluminescence. The symbols I, II, and III are retained to enable comparison with

Figure 3. The symbol * indicates a not fully characterised excited state.

Figure 4.

Hastings’ proposal for a defined role for a luciferase-bound proxide as a key intermediate in bacterial bioluminescence. The symbols I, II, and III are retained to enable comparison with

Figure 3. The symbol * indicates a not fully characterised excited state.

Figure 5.

Criegee’s proposed mechanism for the abiotic oxidation of a ketone to its corresponding ester by peracid catalysis.

Figure 5.

Criegee’s proposed mechanism for the abiotic oxidation of a ketone to its corresponding ester by peracid catalysis.

Figure 6.

The established biochemistry of 2,5-diketocamphane 1,2-monooxygenase, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase induced in camphor-grown Pseudomonas putida ATCC 17453.

Figure 6.

The established biochemistry of 2,5-diketocamphane 1,2-monooxygenase, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase induced in camphor-grown Pseudomonas putida ATCC 17453.

Figure 7.

Comparing the fully characterised outcomes of the biooxidation of (rac)-bicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-one by 2,5-diketocamphane 1,2-monooxygenase from Pseudomonas putida ATCC 17453 and the luciferase from Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744.

Figure 7.

Comparing the fully characterised outcomes of the biooxidation of (rac)-bicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-one by 2,5-diketocamphane 1,2-monooxygenase from Pseudomonas putida ATCC 17453 and the luciferase from Vibrio fischeri ATCC 7744.

Figure 8.

The oxybiontic cleavage of the C-S bond of short-chain alkanesulfonate.

Figure 8.

The oxybiontic cleavage of the C-S bond of short-chain alkanesulfonate.

Figure 9.

The three-step sequential biooxidation of dibenzothiophene to 2-hydroxy-biphenyl-2-sulfinite by Rhodococcus erythropolis deploying successive actions of the FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases DszC and DszA, both functioning in cooperation with flavin reductase DszD.

Figure 9.

The three-step sequential biooxidation of dibenzothiophene to 2-hydroxy-biphenyl-2-sulfinite by Rhodococcus erythropolis deploying successive actions of the FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases DszC and DszA, both functioning in cooperation with flavin reductase DszD.

Figure 10.

Generalised summary of the relevant reactions undergone by the reduced flavin cosubstrate and dioxygen in the nucleophilic and electrophilic oxygenations catalysed by FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases. X =ketone; XO = lactone/aldehyde; Y = organosulfide/sulfoxide; YO = organosulfoxide/sulfone.

Figure 10.

Generalised summary of the relevant reactions undergone by the reduced flavin cosubstrate and dioxygen in the nucleophilic and electrophilic oxygenations catalysed by FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases. X =ketone; XO = lactone/aldehyde; Y = organosulfide/sulfoxide; YO = organosulfoxide/sulfone.

Figure 11.

The oxybiontic hydroxylation of dihydrokalafungin by ActVA, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Streptomyces coelicolor.

Figure 11.

The oxybiontic hydroxylation of dihydrokalafungin by ActVA, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Streptomyces coelicolor.

Figure 12.

The oxybiontic oxidation of PIIB to PIIA by PIIA synthase, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase isolated from various Streptomyces spp.

Figure 12.

The oxybiontic oxidation of PIIB to PIIA by PIIA synthase, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase isolated from various Streptomyces spp.

Figure 13.

The oxybiontic hydroxylation of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate by C2 (AbHpaB) monooxygenase, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Acinetobacter baumanii.

Figure 13.

The oxybiontic hydroxylation of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate by C2 (AbHpaB) monooxygenase, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Acinetobacter baumanii.

Figure 14.

The oxybiontic oxidation of deoxyactagaradine to actagaradine by GarO, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase isolated from Actinoplanes garbadinensis.

Figure 14.

The oxybiontic oxidation of deoxyactagaradine to actagaradine by GarO, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase isolated from Actinoplanes garbadinensis.

Figure 15.

The oxybiontic oxidation of olimycin C by OvmO, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Streptomyces olivaceus SCS10 T05.

Figure 15.

The oxybiontic oxidation of olimycin C by OvmO, an FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenase from Streptomyces olivaceus SCS10 T05.

Table 1.

Confirmed examples of FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases and their corresponding flavin reductase(s) cited by Garcia in 2000 and subsequently by Ellis in 2010. a = monomeric; b = homodimeric; c = heterodimeric; d = homotetrameric.

Table 1.

Confirmed examples of FMN-dependent two-component monooxygenases and their corresponding flavin reductase(s) cited by Garcia in 2000 and subsequently by Ellis in 2010. a = monomeric; b = homodimeric; c = heterodimeric; d = homotetrameric.

Table 2.

Shared functional characteristics of the bacterial luciferases and other directly related prokaryotic enzymes as reflected by the different proposed collective descriptors TC-ODEs, Type II BVMOs, TC-FDMs, and FD-TCMOs.

Table 2.

Shared functional characteristics of the bacterial luciferases and other directly related prokaryotic enzymes as reflected by the different proposed collective descriptors TC-ODEs, Type II BVMOs, TC-FDMs, and FD-TCMOs.