Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

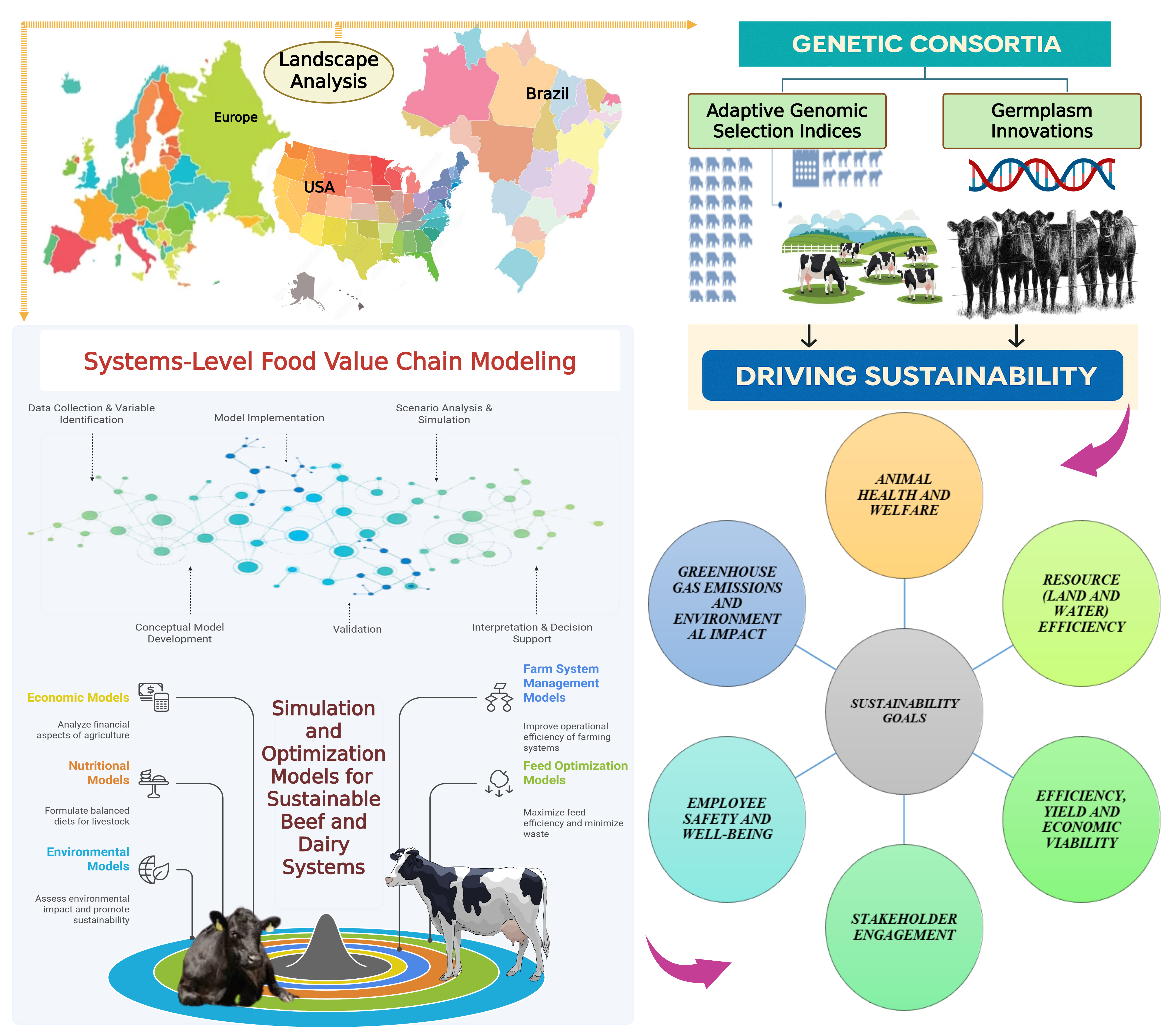

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

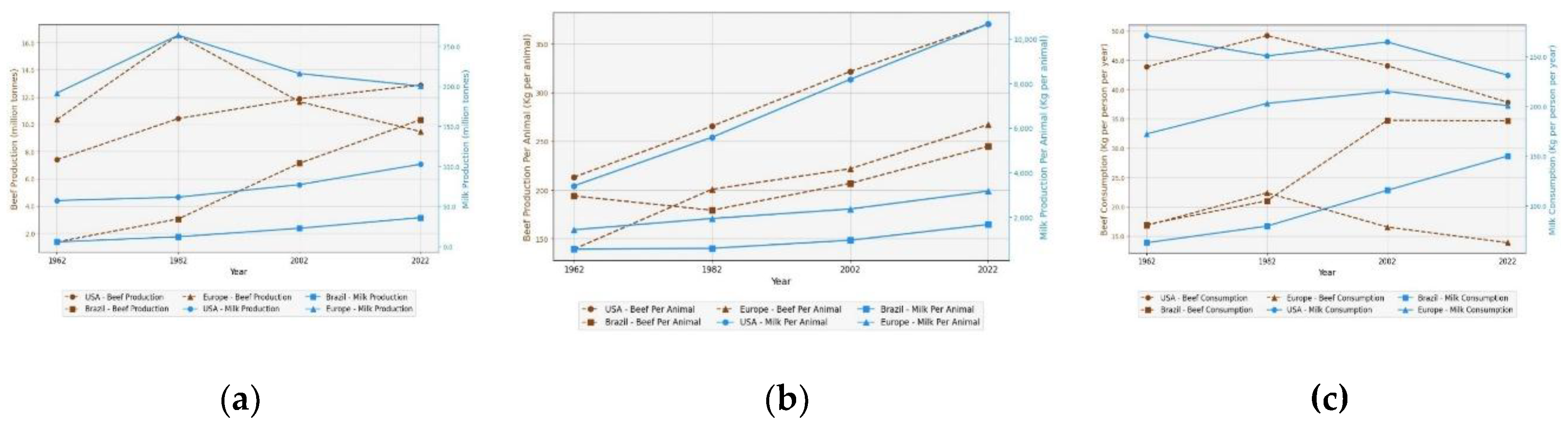

2. Regional Trends in Beef and Dairy Population, Production and Consumption Patterns in the USA, Europe and Brazil

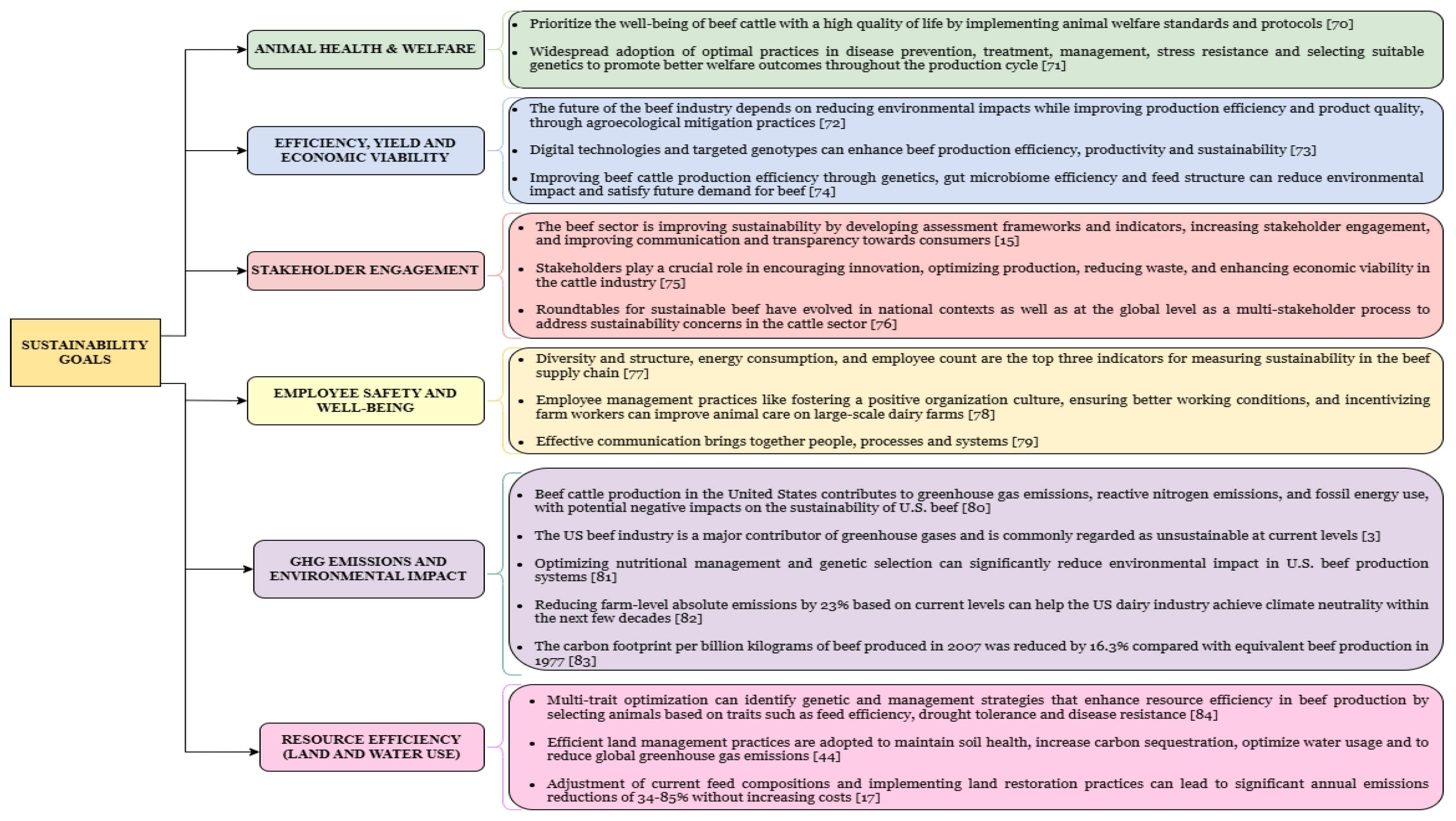

3. Multidimensional Sustainability Analysis in Beef Production: insights from the USA, Europe and Brazil

4. Innovations in Dairy Production: Enhancing Cattle Welfare, Genetic Improvements, Technological Advancements and Herd Management Strategies for Dairy Sustainability

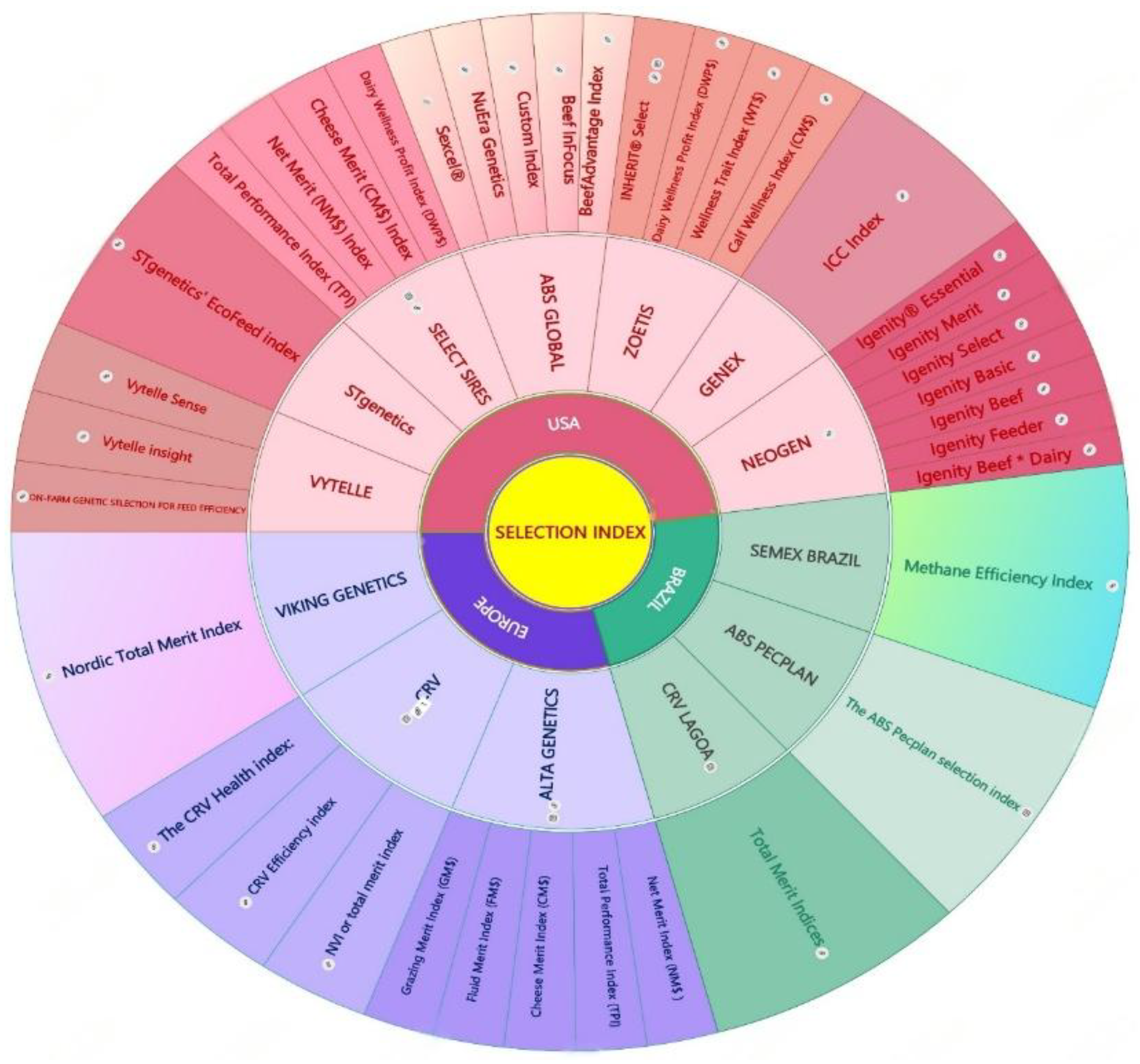

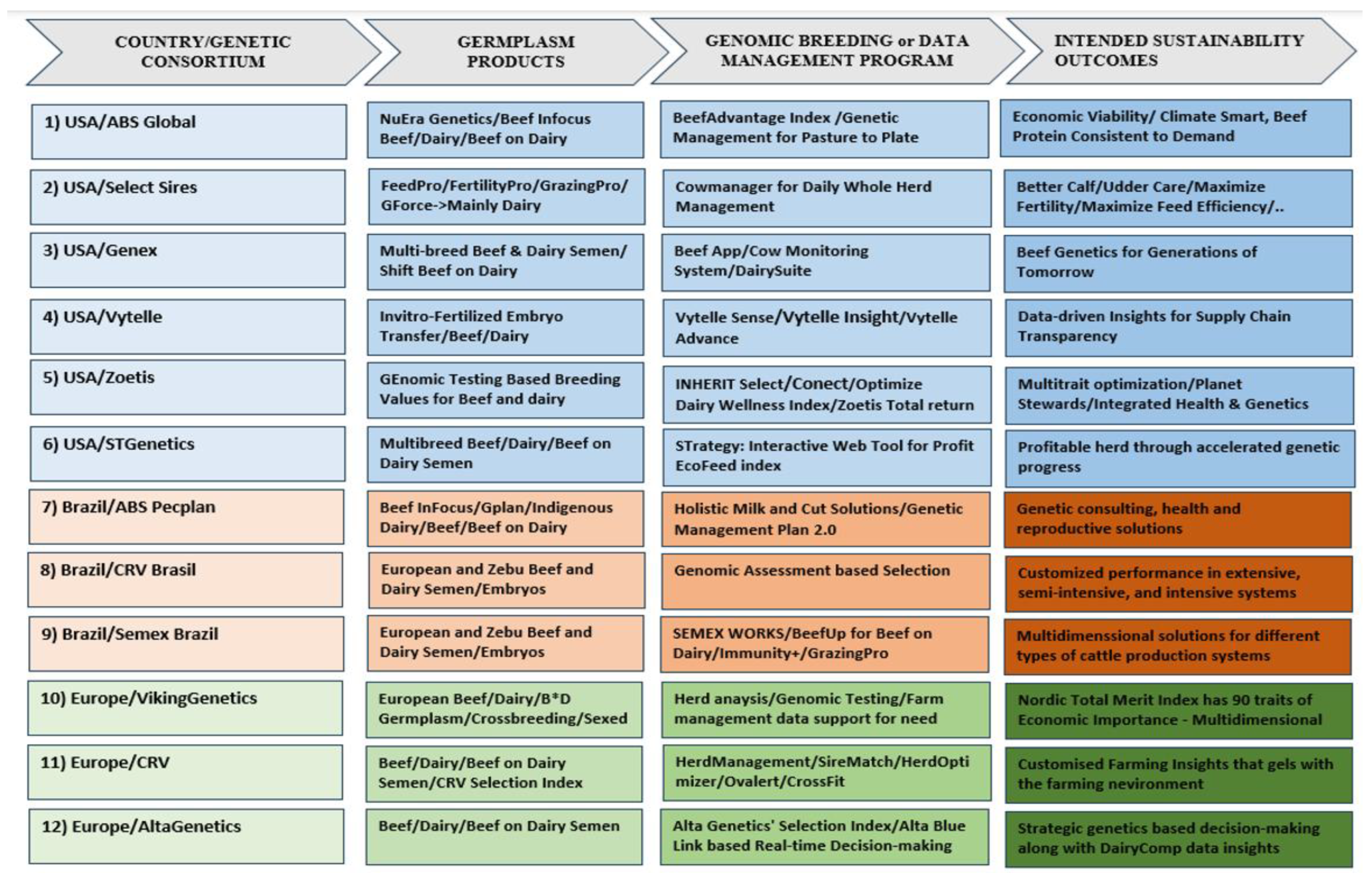

5. Landscape Analysis of Genetic Consortia in the Beef and Dairy Industries of the USA, Europe and Brazil: Driving Sustainability Through Adaptive Genomic Selection Indices and Germplasm Innovations

6. Decision-Making for Beef and Dairy Sustainability: The Need for Systems-Level Food Value Chain Modeling

| MODELS | PREDICTIVE VARIABLES AND SUSTAINABILITY OUTCOMES | REGION | FARM TYPE | METHODOLOGY AND SCOPE | |

| Economic Models | |||||

| Farm Model (FM) [123] | Evaluate dairy farm resilience by simulating production plan adjustments to adapt to external challenges and uncertainties | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization | |

| Bio-Economic model implemented using GAMS (General Algebraic Modeling System) software [124] | Assess farmers' adoption of precision agriculture practices by evaluating its economic and biological impacts on Greek dairy cattle farms. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization | |

| ScotFarm [125] | Assess the financial vulnerability of Scottish dairy farms by simulating Johne's disease and payment support impacts to optimize economic resilience and sustainability. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization | |

| Dynamic stochastic simulation model [126] | Optimize dry period decisions in dairy herds by simulating impacts on milk production, cash flow, and emissions, accounting for farm variability. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Moorepark Dairy Systems Model (MDSM) [127] | Evaluate the financial performance of Holstein Friesian strains in different systems to identify the most profitable breeding and management strategies | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation | |

| Dairy Farm Model [128] | Evaluate manure policy impacts on profitability, nutrient management, and emissions after milk quota abolition. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization | |

| A mathematical programming model [129] | Optimize dairy management to meet somatic cell count targets, improving milk quality and profitability while reducing mastitis control costs. | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

|

| A dynamic cattle growth model Discounted cash flow (DCF) models [130] |

Evaluate profitability, risk, and cash flow in cow-calf operations by simulating cattle growth and financial performance to guide investment decisions. | USA | Beef | Intrafarm Simulation; optimization |

|

| The Forage and Cattle Analysis and Planning (FORCAP) model [120] | Simulate and evaluate the feasibility of dual-use forage systems in cow-calf operations to optimize management for profitability and sustainability. | USA | Beef; dairy | Whole farm Simulation |

|

| Bioeconomic model [100] | Simulate the economic and biological impacts of tick infestations on Brazilian beef systems to optimize management, reduce losses, and improve cattle health. | Brazil | Beef | Whole farm Simulation |

|

| A bio-economic farm model [131] | Assess the viability of conservation agriculture in Brazil's mixed crop-livestock systems by optimizing resource use for profitability and ecological resilience | Brazil | Beef; dairy | Whole farm Optimization |

|

| Nutritional/Farm System Management Models | |||||

| DigiMilk model [113] | Optimize the dairy supply chain by integrating digital technologies to enhance traceability, resource efficiency, and sustainability in milk production and distribution. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation | |

| Pasture-Based Herd Dynamic Milk Model (PBHDM) [114] | Simulate and predict milk production in pasture-based dairy systems, considering herd size, pasture availability, and seasonal variations. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation | |

| Dairy Wise [132] | Simulate dairy farm processes to optimize herd management, improve profitability, and reduce gastrointestinal nematode risk under varying conditions | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation | |

| Multiscale agent-based simulation model of a dairy herd (MABSDairy) [133] | Simulate interactions between animals, herd dynamics, and management to optimize dairy herd health, productivity, and economic outcomes. | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Stochastic dynamic simulation modelling [134] | Evaluate reproduction and selection strategies in dairy herds to optimize performance and economic outcomes, considering farm uncertainty and variability. | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| A multi-objective mixed-integer nonlinear fractional programming (MINLFP) model [135] | Optimize organic mixed farming by balancing profitability, resource efficiency, and sustainability through nutrient recycling. | USA | Beef; Dairy | Whole farm Optimization |

|

| Farm System Management Models | |||||

| Mathematical model developed in the Czech University [136] | Optimize milking parlor performance by simulating management scenarios to enhance efficiency and profitability in dairy farms. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Moorepark Dairy Systems Model (MDSM) Pasture-Based Herd Dynamic Milk Model (PBHDM) [137] |

Simulate pasture-based dairy systems to optimize herd management, maximizing milk production and profitability | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation | |

| The mathematical model created in the Czech Republic [138] | Improve operational efficiency and economic performance by simulating different milking systems under farm-specific conditions. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| The farm optimization model FARMDYN [105] | Simulate and optimize farm decisions by integrating economic, environmental, and social sustainability in European beef systems. | Europe | Beef; dairy | Whole farm Optimization & simulation |

|

| Deterministic whole herd simulation model [119] | Optimize dairy herd management by simulating milking capacity, housing, and fat quota impacts on economics, productivity, and herd dynamics | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

|

| Organic Dairy Model [139] | Optimize forage and supplement use on southeastern U.S. organic dairy farms to enhance profitability, sustainability, and resource efficiency | USA | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization |

|

| Nutritional Models | |||||

| Stochastic and dynamic mathematical model [140] | Simulate dairy farm performance under varying management and environmental conditions to optimize decision-making amid operational uncertainty. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Nordic Dairy Cow Model, Karoline [141,142] | Simulate digestion, metabolism, and nutrient use in dairy cows to optimize feeding and improve milk efficiency in Nordic systems. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation | |

| Molley Model [143] | Simulate metabolic processes in lactating cows to optimize feeding and improve milk production efficiency. | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Feed Optimization Models | |||||

| A feed pusher robot, designed and simulated using Simulink tools [144] | Automate feed pushing process to improve efficiency and reduce labour in dairy and livestock farms. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Linear Program Optimization (LPO) Model [145] | Optimize nutritional resource allocation in a dairy herd by minimizing feed costs while meeting dietary, health, and farm constraints efficiently. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization; | |

| Linear programming (LP) and weighted goal programming (WGP) techniques [146] | Optimize dairy cow rations on organic farms by balancing feed costs, nutrition, and organic farming constraints | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization | |

| Nordic Feed Evaluation System (NorFor Model) [110] | Optimize ruminant feeding by predicting nutrient needs and feed use to improve milk, meat production efficiency, and farm profitability. | Europe | Beef; dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Rostock Feed Evaluation System [147,148] | Assess nutrient supply and utilization in ruminants by modeling digestion to optimize feeding efficiency and improve livestock productivity and sustainability. | Europe | Beef; dairy | Intrafarm evaluation model with simulation components | |

| A multi-period LP feed model [149] | Optimize dairy feed selection by evaluating economic and nutritional trade-offs over time to improve profitability and efficiency | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

|

| Farm-scale diet optimization model [150] | Optimize energy and protein efficiency in dairy diets to reduce land, water use, emissions, and enhance sustainability and profitability. | USA | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation |

|

| The Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS) [151,152,153,154] | Predict ruminant nutrient needs by modeling digestion and metabolism to optimize diets for improved performance and efficiency | USA | Dairy; Beef | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Ruminant Nutrition System (RNS) [155] | Predict ruminant nutrient needs, intake, and performance, optimizing diets for productivity and sustainability | USA | Dairy; Beef | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Environmental Models | |||||

| Financial and Renewable Multi-objective Optimization (FARMOO) Model [156] | Integrate economic profitability with environmental sustainability by maximizing financial returns, minimizing carbon footprint, and optimizing renewable energy in agricultural systems. | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization | |

| HolosNor [157] | Assess mitigation strategies to reduce emissions intensity while maintaining or improving farm economic performance. | Europe | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization and simulation | |

| Optimization of Ruminant Farm for Economic and Environmental assessment (Orfee) [106] | Optimize biotechnical and economic performance of mixed herds by balancing profitability and sustainability under different management strategies. | Europe | Beef; dairy | Whole farm Optimization | |

| Pasture Simulation Model (PaSim) [109] |

Simulate climate, soil, and pasture interactions to assess livestock production, emissions, and carbon sequestration under various management and climate scenarios. | Europe | Beef; dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

|

| Integrated Farm System Model (IFSM) [158] | Simulate environmental and economic impacts of farm practices, focusing on sustainability metrics like emissions, nutrient cycling, and resource efficiency in grazing dairy farms. | USA | Dairy | Whole farm Simulation and optimization |

|

| N-CyCLES (nutrient cycling: crops, livestock, environment, and soil) [159] | Optimize nutrient cycling between crops, livestock, soil, and environment to reduce nutrient imbalances and enhance sustainability and profitability on dairy farms. | USA | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization |

|

| A linear programming mathematical model [101] | Optimize livestock-crop systems by efficiently allocating resources to maximize profitability while considering environmental sustainability | Brazil | Dairy | Whole farm Optimization |

|

| Economic, Environmental and Feed Optimization Models | |||||

| Nonlinear multiobjective diet optimization | Optimize cattle feeding by minimizing costs and GHG emissions while maximizing productivity and nutritional efficiency | Europe | Beef | Intrafarm Optimization | |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NASS | National Agricultural Statistics Service |

| SFA | Sustainable Food and Agriculture |

| GRSB | Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| MM | Mathematical modelling |

| CNCPS | Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System |

| MOLP | Multi-objective linear programming |

| FORCAP | Forage and Cattle Analysis and Planning |

| FARMOO | Financial and Renewable Multi-objective Optimization |

References

- Bishop, S.C.; Woolliams, J.A. Genetic approaches and technologies for improving the sustainability of livestock production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeten, J.M. Environmental management for the beef cattle industry. In Proceedings of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners Conference, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Firbank, L.G. The beef with sustainability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 2, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, P.J.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.I.; Falcucci, A.; Teillard, F. Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, F.P.; Meuwissen, M.P.; Lansink, A.O. Evaluation of beef sustainability in conventional, organic, and mixed crop–beef supply chains. Unpublished work.

- Lerma, L.M.; Díaz Baca, M.F.; Burkart, S. Sustainable beef labelling in Latin America and the Caribbean: Initiatives, developments, and bottlenecks. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, P.; Bréchet, T. Models for policy-making in sustainable development: The state of the art and perspectives for research. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrieciu, S.; Varga, L.; Zimmermann, N.; Chalabi, Z.; Freeman, R.; Dolan, T.; Borisoglebsky, D.; Davies, M. An inquiry into model validity when addressing complex sustainability challenges. Complex. 2022, 1193891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.S.; Zahid, A.; Das, A.K.; Muzammil, M.; Khan, M.U. A systematic literature review on deep learning applications for precision cattle farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.; Petrovic, V.; Gorlov, I.; Slozenkina, M.; Selionova, M.; Nikolaevna, I.; Itckovich, Y. Perspectives and challenges of global cattle and sheep meat and milk production. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Russia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-ERS. Farm income and wealth statistics: U.S. and state-level farm income and wealth statistics. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Per capita consumption of other meat – FAO. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-meat-consumption-by-type-kilograms-per-year (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Daniel, C.; Cross, A.; Koebnick, C.; Sinha, R. Trends in meat consumption in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 14, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henchion, M.; Moloney, A.; Hyland, J.; Zimmermann, J.; McCarthy, S. Trends for meat, milk and egg consumption for the next decades and the role played by livestock systems. Anim. 2021, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.; Petre, R.; Jackson, F.; Hadarits, M.; Pogue, S.; Carlyle, C.; Bork, E.; McAllister, T. Sustainability enhancements in the beef value chain: State-of-the-art and recommendations. Anim. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, D. Sustainability of the beef industry. In Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics; Springer: Location, Country, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castonguay, A.C.; Polasky, S.; Holden, M.H.; et al. Navigating sustainability trade-offs in global beef production. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, J.; Calvo-Lorenzo, M. Practical developments in managing animal welfare in beef cattle: what does the future hold? J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 5334–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshel, G.; Shepon, A.; Shaket, T.; et al. A model for "sustainable" US beef production. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 2, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezenova, N.; Agafonova, S.; Mezenova, O.; et al. Potential of protein nutraceuticals from collagen-containing beef raw materials. Theory Pract. Meat Process. 2021, 6, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbart, J.A.; Blake, N.; Holásková, I.; et al. Challenges in sustainable beef cattle production: A subset of needed advancements. Challenges 2023, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahmani, P.; Ponnampalam, E.; Kraft, J.; et al. Bioactivity and health effects of ruminant meat lipids. Meat Sci. 2020, 165, 108114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N.; DeVuyst, E.; Brorsen, B.; Lusk, J. Yield and quality grade outcomes influenced by molecular breeding values. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 2045–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouillard, J. Current situation and future trends for beef production in the United States. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.; Ellies-Oury, M.; Lherm, M.; et al. Current situation and future prospects for beef production in Europe. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.; Chatellier, V. Prospects for the European beef sector over the next 30 years. Anim. Front. 2011, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagranda, Y.G.; Wiśniewska-Paluszak, J.; Paluszak, G.; et al. Emergent research themes on sustainability in the Brazilian beef cattle industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.; Oliveira, T.; Oliveira, J. Sustainability in the Brazilian pampa biome: A composite index to integrate beef production, social equity, and ecosystem conservation. Ecol. Indic. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, P.; Gibbs, H.; Vale, R.; et al. The expansion of intensive beef farming to the Brazilian Amazon. Glob. Environ. Change 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, G.; Alves, E.; Contini, E. Land-saving approaches and beef production growth in Brazil. Agric. Syst. 2012, 110, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguelangelo, G.; Gianezini, J.; Otávio, J.; et al. Sustainability and market orientation in the Brazilian beef chain. Unpublished work.

- Smith, S. Muscle biology and meat quality – challenges, innovations, and sustainability. In Book Title; Elsevier: Location, Country, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S.; Miller, M.; Amy, M.S. Beef production: Human and environmental impacts. Nutr. Today 2020, 55, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.; Henchion, M.; Hyland, J.J.; Gutiérrez, J.A. Creating a rainbow for sustainability: The case of sustainable beef. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, M.; Boer, I. Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackhouse-Lawson, K.R.; Thompson, L.R. Climate change and the beef industry: A rapid expansion. J. Anim. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, L.; van Marle-Köster, E. Moving towards sustainable breeding objectives and cow welfare in dairy production: A South African perspective. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.; Beauchemin, K. A holistic perspective of the societal relevance of beef production and its impacts on climate change. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, C.; Asem-Hiablie, S.; Dillon, J.; Bonifacio, H. Cradle-to-farm gate environmental footprints of beef cattle production in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 2509–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotz, C.; Isenberg, B.; Stackhouse-Lawson, K.; Pollak, E. A simulation-based approach for evaluating environmental footprints of beef production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5427–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgar-Komleh, S.; Beldman, A. Literature review of beef production systems in Europe. Unpublished work.

- Desjardins, R.; Worth, D.; Vergé, X.; et al. Carbon footprint of beef cattle. Sustainability 2012, 4, 3279–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, M.; Steyn, Y.; Marle-Köster, E.; Theron, H. Improved production efficiency in cattle to reduce carbon footprint. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 42, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, D.; Kazanski, C.; Hedgpeth, A.; et al. Reducing climate impacts of beef production: A synthesis of life cycle assessments across management systems. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1721–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Kreuter, U.; Davis, C.; Cheye, S. Climate impacts of alternative beef production systems depend on the functional unit used. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2321245121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.J.; Lewin, H.A.; Goddard, M. The future of livestock breeding: Genomic selection for efficiency, reduced emissions intensity, and adaptation. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragaglio, A.; Braghieri, A.; Pacelli, C.; Napolitano, F. Environmental impacts of beef corrected for ecosystem services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 93828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, D.; Putman, B.; Thoma, G. Life cycle assessment of forage-based livestock production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Ge, D. Optimization of sustainable land use management in water source areas using water quality dynamic monitoring model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 3881092, (Retracted.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridoutt, B.; Sanguansri, P.; Harper, G. Comparing carbon and water footprints for beef cattle production in Southern Australia. Sustainability 2011, 3, 2443–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.; Murphy, B.; Cowie, A. Sustainable Land Management for Environmental Benefits and Food Security. A Synthesis Report for the GEF; Global Environment Facility: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; 127p. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, B.; Briggs, K.; Nydam, D. Dairy production sustainability through a one-health lens. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2022, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Briggs, K.R.; Eicker, S.; Overton, M.; Nydam, D.V. Herd turnover rate reexamined: A tool for improving profitability, welfare, and sustainability. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskó, B. An analysis of the Hungarian dairy industry in the light of sustainability. Reg. Bus. Stud. 2011, 3, 699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A. Sustainable dairy breeding: Working within the US national evaluation system. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesogan, A.; Dahl, G. MILK Symposium introduction: Dairy production in developing countries. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103(11), 9677–9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greblikaite, J.; Astrovienė, J.; Rakštys, R. Analysis of sustainable dairy farming practices in the EU and foreign countries. Rural Dev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauly, M.; Bollwein, H.; Breves, G.; Brügemann, K.; Dänicke, S.; Daş, G.; Demeler, J.; Hansen, H.; Isselstein, J.; König, S.; et al. Future consequences and challenges for dairy cow production systems arising from climate change in Central Europe—A review. Anim. 2013, 7, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Barraj, L.; Toth, L.; Harkness, L.; Bolster, D. Daily intake of dairy products in Brazil and contributions to nutrient intakes: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 19, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.; Alves, E.; Melo, F.; Barroso, I.; Soares, A.; Imazaki, P.; Medeiros, E. Overview of the milk production chain in Brazil: Development and perspectives. Rev. Cient. Multidiscip. Núcleo Conhecimento 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, R.; Fregonesi, J.A.; Vieira, A.D. Sustainable dairy cattle production in Southern Brazil: A proposal for engaging consumers and producers to develop local policies and practices. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Hötzel, M.; Longo, C.; Balcão, L. A survey of management practices that influence production and welfare of dairy cattle on family farms in southern Brazil. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankuti, F.; Prizon, R.; Damasceno, J.; De Brito, M.; Pozza, M.; Lima, P. Farmers’ actions toward sustainability: A typology of dairy farms according to sustainability indicators. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borawski, P.; Kalinowska, B.; Mickiewicz, B.; Parzonko, A.; Klepacki, B. Changes in the milk market in the United States on the background of the European Union and the world. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Dairy. Environmental sustainability. U.S. Dairy. Available online: https://www.usdairy.com/sustainability/environmental-sustainability (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy. 2021–2022 U.S. Dairy Sustainability Report. Available online: https://2021-2022report.usdairy.com/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Berry, D.P. Invited review: Beef-on-dairy—The generation of crossbred beef × dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104(4), 3789–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, A.; Ott, T.; Tricarico, J.; Rotz, A.; Waghorn, G.; Adesogan, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Montes, F.; Oh, J.; Kebreab, E.; et al. Special topics—Mitigation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from animal operations: III. A review of animal management mitigation options. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5095–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Hermansen, J.; Mogensen, L. Environmental consequences of different beef production systems in the EU. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, E.; Mullan, S. Advancing a “good life” for farm animals: Development of resource tier frameworks for on-farm assessment of positive welfare for beef cattle, broiler chicken and pigs. Anim. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compiani, R. Strategies to optimize the productive performance of beef cattle. Ph.D. Thesis, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulina, G.; Acciaro, M.; Atzori, A.S.; Battacone, G.; Crovetto, G.M.; Mele, M.; Pirlo, G.; Rassu, S.P. Animal board invited review—Beef for future: Technologies for a sustainable and profitable beef industry. Anim. 2021, 15, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P. Review: An overview of beef production from pasture and feedlot globally, as demand for beef and the need for sustainable practices increase. Anim. 2021, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T.; Basarab, J.; Guan, L. 177 Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikin, Z.; Baker, D.; Villano, R.; Daryanto, A. Business models and innovation in the Indonesian smallholder beef value chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.J.; Newton, P.; Gibbs, H.K.; McConnel, I.; Ehrmann, J. Pursuing sustainability through multi-stakeholder collaboration: A description of the governance, actions, and perceived impacts of the roundtables for sustainable beef. World Dev. 2019, 121, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanty, A.; Puspitasari, N.; Purwaningsih, R.; Hazazi, H. Prioritization of an indicator for measuring sustainable performance in the food supply chain: Case of beef supply chain. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), 2019; pp. 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; von Keyserlingk, M.; Magliocco, S.; Weary, D. Employee management and animal care: A comparative ethnography of two large-scale dairy farms in China. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchio-Sadus, A.; Griffiths, S. Marketing strategies for enhancing safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, C.; Asem-Hiablie, S.; Place, S.; Thoma, G. Environmental footprints of beef cattle production in the United States. Agric. Syst. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; Brady, M.; Capper, J.; McNamara, J.; Johnson, K. Cow–calf reproductive, genetic, and nutritional management to improve the sustainability of whole beef production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3197–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S.; McCabe, C.; Mitloehner, F. Symposium review: Defining a pathway to climate neutrality for US dairy cattle production. J. Dairy Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, J. The environmental impact of beef production in the United States: 1977 compared with 2007. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89(12), 4249–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, S.; Basarab, J.; Guan, L.; McAllister, T. Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 101, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietala, P.; Juga, J. Impact of including growth, carcass and feed efficiency traits in the breeding goal for combined milk and beef production systems. Anim. 2017, 11, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Tzimiropoulos, G. Novel monitoring systems to obtain dairy cattle phenotypes associated with sustainable production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.; Bédère, N.; Douhard, F.; Oliveira, H.; Arnal, M.; Peñagaricano, F.; Schinckel, A.; Baes, C.; Miglior, F. Review: Genetic selection of high-yielding dairy cattle toward sustainable farming systems in a rapidly changing world. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci 2021, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Y.D.; Pszczoła, M.; Soyeurt, H.; Wall, E.; Lassen, J. Invited review: Phenotypes to genetically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in dairying. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Y.; Veerkamp, R.; Jong, G.; Aldridge, M. Selective breeding as a mitigation tool for methane emissions from dairy cattle. Anim. 2021, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renand, G.; Vinet, A.; Decruyenaere, V.; Maupetit, D.; Dozias, D. Methane and carbon dioxide emission of beef heifers in relation with growth and feed efficiency. Animals 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzanilla-Pech, C.; Løvendahl, P.; Gordo, D.; Difford, G.; Pryce, J.; Schenkel, F.; Wegmann, S.; Miglior, F.; Chud, T.; Moate, P.; et al. Breeding for reduced methane emission and feed-efficient Holstein cows: An international response. J. Dairy Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Jauernik, G. Selecting the “sustainable” cow using a customized breeding index: Case study on a commercial UK dairy herd. Agriculture 2023, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger-Danner, C.; Cole, J.; Pryce, J.; Gengler, N.; Heringstad, B.; Bradley, A.; Stock, K. Invited review: Overview of new traits and phenotyping strategies in dairy cattle with a focus on functional traits. Anim. 2014, 9, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; MacNeil, M.; Dekkers, J.; Crews, D.; Rathje, T.; Enns, R.; Weaber, R. Life-cycle, total-industry genetic improvement of feed efficiency in beef cattle: Blueprint for the Beef Improvement Federation. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.; May, K. Invited review: Phenotyping strategies and quantitative-genetic background of resistance, tolerance and resilience-associated traits in dairy cattle. Anim. 2019, 13, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boichard, D.; Brochard, M. New phenotypes for new breeding goals in dairy cattle. Anim. 2012, 6(4), 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miglior, F.; Fleming, A.; Malchiodi, F.; Brito, L.; Martin, P.; Baes, C. A 100-year review: Identification and genetic selection of economically important traits in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10251–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, K.; Smith, C. Abstraction and modelling of agri-food chains as complex decision making systems. In Proceedings; 2008; Volume 2, pp. 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Menendez, H.M., III. Mathematical modelling in animal production. In Animal Agriculture; Academic Press: Place, Country, 2020; pp. 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvano, M.P.C.; Brumatti, R.C.; Barros, J.C.; Garcia, M.V.; Martins, K.R.; Andreotti, R. Bioeconomic simulation of Rhipicephalus microplus infestation in different beef cattle production systems in the Brazilian Cerrado. Agric. Syst. 2021, 194, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, A.; Rocco, C.; Caixeta Filho, J. Linear programming in the economic estimate of livestock-crop integration: Application to a Brazilian dairy farm. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2016, 45, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarraghy, S.; Ólafsdóttir, G.; Kazakov, R.; Huber, É.; Loveluck, W.; Gudbrandsdottir, I.; Čechura, L.; Esposito, G.; Samoggia, A.; Aubert, P.; et al. Conceptual system dynamics and agent-based modelling simulation of interorganisational fairness in food value chains: Research agenda and case studies. Agriculture 2022, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, P.A.; Davis, M.E.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Rutledge, J.J.; Cundiff, L.V. A mathematical nutrition model adequately predicts beef and dairy cow intake and biological efficiency. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txab230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaking, P.; Suryani, E. Beef supply chain analysis to improve availability and supply chain value using system dynamics methodology. IPTEK J. Proc. Ser. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokemohr, L.; Escobar, N.; Mertens, A.; Mosnier, C.; Pirlo, G.; Veysset, P.; Kuhn, T. Life cycle sustainability assessment of European beef production systems based on a farm-level optimization model. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakité, Z.; Mosnier, C.; Baumont, R.; Brunschwig, G. Biotechnical and economic performance of mixed dairy cow–suckler cattle herd systems in mountain areas: Exploring the impact of herd proportions using the Orfee model. Livest. Sci. 2019, 229, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, B.; Bernardes, E.; Rodrigues, B.; Gameiro, A.; Sarturi, J. Development of a mathematical model for cost calculation and sustainability analysis of beef cattle grazing systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, M.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.; Vorst, J. Modelling food logistics networks with emission considerations: The case of an international beef supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graux, A.I.; Gaurut, M.; Agabriel, J.; Baumont, R.; Delagarde, R.; Delaby, L.; Soussana, J.F. Development of the Pasture Simulation Model for assessing livestock production under climate change. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 144, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volden, H. NorFor – The Nordic Feed Evaluation System; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, V.; Fernandes, A.; Passafaro, T.; Acedo, J.; Dias, F.; Dórea, J.; Rosa, G. Forecasting beef production and quality using large scale integrated data from Brazil. J. Anim. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilova, E.; Vaklieva-Bancheva, N.; Vladova, R.; Petrova, T.; Ivanov, B.; Nikolova, D.; Dzhelil, Y. An approach for sustainable decision-making in product portfolio design of dairy supply chain in terms of environmental, economic and social criteria. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 24, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosona, T.; Gebresenbet, G. Multipurpose simulation model for pasture-based mobile automated milking and marketing system, Part I: Pasture, milk yield, and milk marketing characteristics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A. A model to describe and predict the production and food intake of the dairy cow. Acta Agric. Scand. 1986, 36, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, M.; Agrusti, M.; Benni, S.; Torreggiani, D.; Tassinari, P. Random forest modelling of milk yield of dairy cows under heat stress conditions. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, L.; Kakhki, M.; Sabouni, M.; Ghanbari, R. The optimization of resilience and sustainability using mathematical programming models and metaheuristic algorithms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayssières, J.; Guerrin, F.; Paillat, J.; Lecomte, P. GAMEDE: A global activity model for evaluating the sustainability of dairy enterprises. Part I—Whole-farm dynamic model. Agric. Syst. 2009, 101, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddoha, M.; Nasir, T.; Hossain, N. A sustainable supply chain framework for dairy farming operations: A system dynamics approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattamanont, P.; De Vries, A. Effects of limits in milking capacity, housing capacity, or fat quota on economic optimization of dry period lengths. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 11715–11737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popp, M.; Ashworth, A.; West, C. Simulating the feasibility of dual use switchgrass on cow–calf operations. Energies 2021, 14, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelle, E.; Shalloo, L.; Butler, S. Economic impact of different strategies to use sex-sorted sperm for reproductive management in seasonal-calving, pasture-based dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 11747–11758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, L. Assessment of the adequacy of mathematical models. Agric. Syst. 2006, 89, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecnik, Z.; Zgajnar, J. Resilience of dairy farms measured through production plan adjustments [Odpornost kmetij s prirejo mleka z različnimi prilagoditvami proizvodnega načrta]. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2022, 23, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleftodimos, G.; Kyrgiakos, L.; Kleisiari, C.; Tagarakis, A.; Bochtis, D. Examining farmers’ adoption decisions towards precision-agricultural practices in Greek dairy cattle farms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Ahmadi, B.; Barratt, A.; Thomson, S.; Stott, A. Financial vulnerability of dairy farms challenged by Johne’s disease to changes in farm payment support. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, A.; Van Middelaar, C.; Mostert, P.; Van Knegsel, A.; Kemp, B.; De Boer, I.; Hogeveen, H. Effects of dry period length on production, cash flows and greenhouse gas emissions of the dairy herd: A dynamic stochastic simulation model. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, M.; Shalloo, L.; Roberts, D.; Ryan, W. Financial evaluation of Holstein Friesian strains within composite and housed UK dairy systems. Livest. Sci. 2017, 200, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klootwijk, C.; Van Middelaar, C.; Berentsen, P.; de Boer, I. Dutch dairy farms after milk quota abolition: Economic and environmental consequences of a new manure policy. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8384–8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troendle, J.; Tauer, L.; Gröhn, Y. Optimally achieving milk bulk tank somatic cell count thresholds. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trejo-Pech, C.; Bruhin, J.; Boyer, C.; Smith, S. Profitability, risk and cash flow deficit for beginning cow–calf producers. Agric. Finance Rev. 2022, 82, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alary, V.; Corbeels, M.; Affholder, F.; Alvarez, S.; Soria, A.; Valadares Xavier, J.; da Silva, F.; Scopel, E. Economic assessment of conservation agriculture options in mixed crop–livestock systems in Brazil using farm modelling. Agric. Syst. 2016, 144, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Voort, M.; Van Meensel, J.; Lauwers, L.; de Haan, M.; Evers, A.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Charlier, J. Economic modelling of grazing management against gastrointestinal nematodes in dairy cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 2017, 236, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamun, M.; Grohn, Y. Mabsdairy: A multiscale agent-based simulation of a dairy herd. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Simulation Symposium, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 2017; Volume 49, pp. 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniyamattam, K.; Elzo, M.A.; Cole, J.B.; De Vries, A. Stochastic dynamic simulation including multitrait genetics to estimate genetic, technical, and financial consequences of dairy farm reproduction and selection strategies. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 8187–8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wai Hui, C.; You, F. Multi-objective economic–resource–production optimization of sustainable organic mixed farming systems with nutrient recycling. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 304–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumenti, A.; da Borso, F.; Chiumenti, R.; Kic, P. Applying a mathematical model to compare, choose, and optimize the management and economics of milking parlors in dairy farms. Agriculture 2020, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelle, E.; Delaby, L.; Wallace, M.; Shalloo, L. Using models to establish the financially optimum strategy for Irish dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada, O.; Leola, A.; Kic, P. Choosing and evaluation of milking parlours for dairy farms in Estonia. Agron. Res. 2016, 14, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, J.; Burdine, K.; Dillon, C.; Smith, S.; Butler, D.; Bates, G.; Pighetti, G. Optimal forage and supplement balance for organic dairy farms in the Southeastern United States. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calsamiglia, S.; Astiz, S.; Baucells, J.; Castillejos, L. A stochastic dynamic model of a dairy farm to evaluate the technical and economic performance under different scenarios. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101(8), 8357–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danfaer, A.; Huhtanen, P.; Udén, P.; Sveinbjörnsson, J.; Volden, H. The Nordic dairy cow model, Karoline—Description. Agric. Food Sci. 2006, 15 (Suppl. 1), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Danfaer, A.; Sveinbjörnsson, J.; Huhtanen, P.; Udén, P.; Volden, H. The Nordic dairy cow model, Karoline—Evaluation. Agric. Food Sci. 2006, 15 (Suppl. 1), 25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.L.; France, J.; Gill, M. Metabolism of the lactating cow. Part II. Digestive elements of a mechanistic model. J. Dairy Res. 1987, 54, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavkin, D.; Shilin, D.; Nikitin, E.; Kiryushin, I. Designing and simulating the control process of a feed pusher robot used on a dairy farm. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingeri, A.; Gallo, A.; Liang, D.; Masoero, F.; Cabrera, V. Development of a linear programming model for the optimal allocation of nutritional resources in a dairy herd. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103(11), 10898–10916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisenk, J.; Turk, J.; Pazek, K. Multi-goal optimization process for formulation of daily dairy cow rations on organic farms: A Slovenian case study. Anim. Nutr. Feed Technol. 2016, 16, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudy, A. Rostock Feed Evaluation System—An example of the transformation of energy and nutrient utilization models to practical application. In Nutrient Digestion and Utilization in Farm Animals: Modelling Approaches; Kebreab, E., Dijkstra, J., Bannink, A., Gerrits, W.J.J., France, J., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 366–382. [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch, W.; Chudy, A.; Beyer, M. Rostock Feed Evaluation System: Reference Numbers of Feed Value and Requirement on the Base of Net Energy; Plexus Verlag: Miltenberg-Frankfurt, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alqaisi, O.; Moraes, L.; Ndambi, O.; Williams, R. Optimal dairy feed input selection under alternative feeds availability and relative prices. Inf. Process. Agric. 2019, 6(4), 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. Increasing energy and protein use efficiency improves opportunities to decrease land use, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions from dairy production. Agric. Syst. 2016, 146, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.; Sniffen, C.; O’Connor, J.; Russell, J.; Van Soest, P. A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluating cattle diets. Part III. Cattle requirements and diet adequacy. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 3578–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.D.; Sniffen, C.J.; Fox, D.G.; Chalupa, W. A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluating cattle diets: IV. Predicting amino acid adequacy. J. Anim. Sci. 1993, 71, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.; O’Connor, J.; Fox, D.; Van Soest, P.; Sniffen, C. A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluating cattle diets. Part I. Ruminal fermentation. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 3551–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniffen, C.; O’Connor, J.; Van Soest, P.; Fox, D.; Russell, J. A net carbohydrate and protein system for evaluating cattle diets. Part II. Carbohydrate and protein availability. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 3562–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Fox, D.G. The Ruminant Nutrition System: An Applied Model for Predicting Nutrient Requirements and Feed Utilization in Ruminants, 2nd ed.; XanEdu: Acton, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, M.; Upton, J.; Murphy, M. Photovoltaic systems on dairy farms: Financial and renewable multi-objective optimization (FARMOO) analysis. Appl. Energy 2020, 278, 115534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülzari, S.; Vosough Ahmadi, B.; Stott, A. Impact of subclinical mastitis on greenhouse gas emissions intensity and profitability of dairy cows in Norway. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 150, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Downing, M.; Nejadhashemi, A.; Elahi, B.; Cassida, K.; Daneshvar, F.; Hernandez-Suarez, J.; Abouali, M.; Herman, M.; Dawood Al Masraf, S.; Harrigan, T. Food footprint as a measure of sustainability for grazing dairy farms. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, D.; Charbonneau, E.; Fadul-Pacheco, L.; Soucy, O.; Wattiaux, M. Economic effect of reducing nitrogen and phosphorus mass balance on Wisconsin and Québec dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 8614–8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.; de Oliveira Silva, R.; Barioni, L.; Hall, J.; Fossaert, C.; Tedeschi, L.; Garcia-Launay, F.; Moran, D. Evaluating environmental and economic trade-offs in cattle feed strategies using multiobjective optimization. Agric. Syst. 2022, 195, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).