Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Gas Exchangers

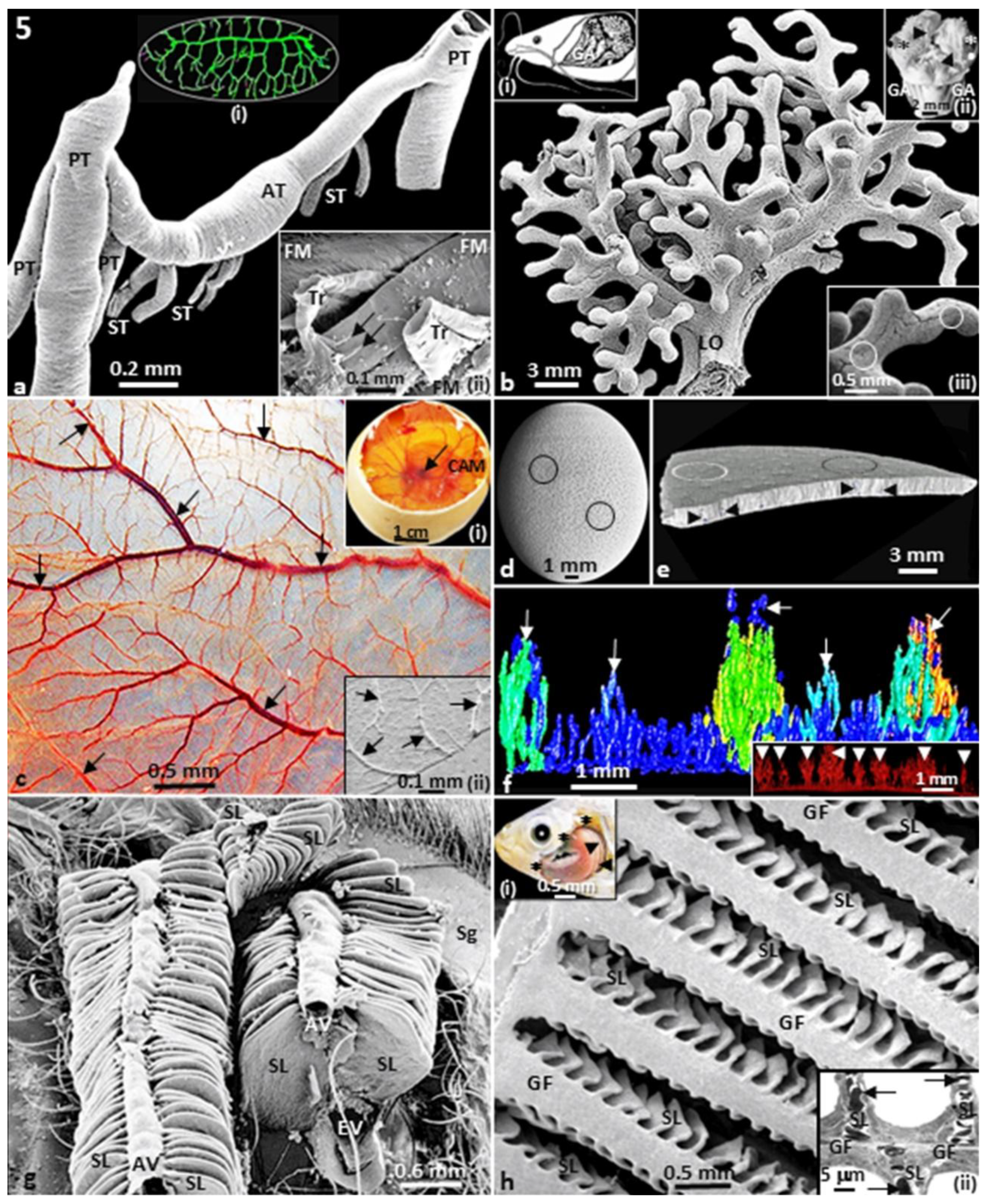

2.1. Bronchioalveolar (Mammalian) Lung

2.2. Parabronchial (Avian) Lung

2.3. Insectan Tracheal System

2.4. Labyrinthine Organs of Catfishes

2.5. Chorioallantoic Membrane of the Avian Egg

2.6. Pores of the Ostrich Egg-Shell

2.7. External Gills

3. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

References

- Korolj A, Wu HT, Radisic M. A healthy dose of chaos: using fractal frameworks for engineering higher-fidelity biomedical systems. Biomaterials 2019; 219:119363. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot B. How long is the coast of Britain? Statistical self-similarity and fractional dimension. Science 1967; 156:636–638. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot B. Form, chance, and dimension. New York, Freeman; 1977.

- Mandelbrot B. The fractal geometry of nature. New York, Freeman; 1983.

- Eshel A. On the fractal dimensions of a root system. Plant, Cell Environm. 1998; 21:247–251. [CrossRef]

- Brown JH et al. The fractal nature of nature: power laws, ecological complexity and biodiversity.Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2002; 357:619–626. [CrossRef]

- Weibel E. Mandelbrot’s fractals and the geometry of life: a tribute to Benoit Mandelbrot on his 80th birthday. Fractals Biol. Med. 2005; 4:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Losa GA. The living realm depicted by the fractal geometry. Fractal Geometry and Nonlinear Anal in Med. and Biol. 2015; 1:11–15. [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot B. Is nature fractal? Science 1998; 279:783–784.

- Weibel ER. Design of biological organisms and fractal geometry. In: Nonnenmacher TF, Losa GA, Weibel ER, Editors. Fractals in biology and medicine, mathematics and biosciences in interaction. Basel, Birkhäuser, 1993. pp. 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Ball P. The self-made tapestry: pattern formation in nature. Tequests (FL): The Booksellers; 2001.

- Ball P. Patterns in nature: why the natural world looks the way it does. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press; 2016.

- Göran P, Nachtigall W. Biomimetics for architecture and design: nature – analogies – technology. Switzerland: Springer (Cham); 2015.

- Bassingthwaighte JB. Fractal vascular growth patterns. Acta Stereol. 1992;11:305–319.

- Bassingthwaighte JB, Liebovitch LS, West BJ. Fractal physiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994.

- West BJ. Deering W. Fractal physiology for physicists: Lévy statistics. Physics Reports 1994; 246:1–100. [CrossRef]

- Peters E. Chaos and order in the capital markets: a new view of cycles, prices, and market volatility. New York: Wiley; 1996.

- Altemeier WA, McKinney S, Glenny T.W. Fractal nature of regional ventilation distribution. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000; 88:1551–1557. [CrossRef]

- Oczeretko E, Juczewska M., Kasacka J. Fractal geometric analysis of lung cancer angiogenic patterns. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2001; 39:75–76.

- Goldberger AL et al. Fractal dynamics in physiology: alterations with disease and aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. (USA) 2002; 99:2466–2472. [CrossRef]

- Vlad MO et al. Functional, fractal nonlinear response with application to rate processes with memory, allometry, and population genetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2007; 104:4798–4803. [CrossRef]

- Delsanto PP et al. multilevel approach to cancer growth modelling. J. Theor. Biol. 2008; 250:16–24. [CrossRef]

- King RD et al. The Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative: characterization of atrophic changes in the cerebral cortex using fractal dimensional analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2009;3:154–166. [CrossRef]

- Popescu DP et al. Signal attenuation and box-counting fractal analysis of optical coherence tomography images of arterial tissue. Biomed. Optics Express 2010; 1:268–277. [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri M et al. Fractal analysis in a systems biology approach to cancer. Sem. Cancer Biol. 2011; 3:175–182. [CrossRef]

- Yanguang, C. Modeling fractal structure of city-size distributions using correlation functions. PLoS One 2011; 6:e24791. [CrossRef]

- Zdenek CC. The fractal nature of human consciousness, the evolution of the ‘global human’ and the driving forces of history. J. Conscious Evol. 2018; 4(4). https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol4/iss4/4.

- Vrdoljak A, Miletić K. Principles of fractal geometry and applications in architecture and civil engineering. e-zb., Elektron. zb. rad. 2019; 17:40–51.

- Pethick J, Winter SL, Burnley M. Did you know? Using entropy and fractal geometry to quantify fluctuations in physiological outputs. Acta Physiologica 2021; 233:e13670. [CrossRef]

- Smith TG et al. A fractal analysis of cell images. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1989; 27:173–180. [CrossRef]

- Goldberger AL, West BJ. Fractals in physiology and medicine. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1987; 60:421–435. [CrossRef]

- Weibel ER. Fractal geometry: a design principle for living organisms. Am. J. Physiol. 1991; 261: L361–L369. [CrossRef]

- Losa GA, Nonnenmacher TF. Self-similarity and fractal irregularity in pathologic tissues. Mod. Pathol. 1996; 9:174–182.

- Captur G et al. The fractal heart – embracing mathematics in the cardiology clinic. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017; 14:56–64. [CrossRef]

- Shah RG et al. Fractal dimensions and branching characteristics of placental chorionic surface arteries. Placenta 2018; 70:4–6. [CrossRef]

- Vicsek T. Fractal growth phenomena. 2nd Ed. Singapore: World Scientific Book; 1992. [CrossRef]

- Falconer K. Fractal geometry: mathematical foundations and applications. New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 2003.

- Essay M, Maina JN. Fractal analysis of concurrently prepared latex rubber casts of the bronchial and vascular systems of the human lung. Open Biol. 2020; 10:190249. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano G, Fasciolo G, Venditti P. The ambiguous aspects of oxygen. Oxygen 2022; 2:382–409. [CrossRef]

- Skulachev V et al. Six functions of respiration: Isn't it time to take control over ROS production in mitochondria, and aging along with it? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023; 24:12540. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez AJ. Respiration-induced biofilm formation as a driver for bacterial niche colonization. Trends in Microbiol. 2023; 31:120–134. [CrossRef]

- Myers RM. What is respiration? School Sci. Math. 1946; 46:691–792.

- Maina JN. The gas exchangers: structure, function, and evolution of the respiratory processes.Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1998.

- Perry SF, Burggren WW. Why respiratory biology? The meaning and significance of respiration and its integrative study. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2007; 47:506–509. [CrossRef]

- Webster LR, Karan S. The physiology and maintenance of respiration: a narrative review. Pain Ther. 2020; 9:467–486. [CrossRef]

- Danovaro R et al. The first metazoa living in permanently anoxic conditions. BMC Biology 2010; 8:30. [CrossRef]

- Kleiber M. The fire of life. New York: Wiley; 1961.

- Maina JN. Comparative respiratory morphology: themes and principles in the design and construction of the gas exchangers. Anat. Rec. 2000; 261:25-44. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. Fundamental structural aspects and features in the bioengineering of the gas exchangers: comparative perspectives. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 2002; 163:1–108.

- Jürgens KD, Gros G. Phylogenese der Gasaustauschsysteme [Phylogeny of gas exchange systems]. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notfallmed. Schmerzther. 2002; 37:185–198.

- Brown JH. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 2004; 85:1771–1789. [CrossRef]

- Glazier DS. Metabolic scaling in complex living systems. Systems 2014; 2:451–540. [CrossRef]

- Wilson DF, Matschinsky FM. Metabolic homeostasis in life as we know it: its origin and thermodynamic basis. Front. Physiol. 12:658997, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wilson TA. Design of the bronchial tree. Nature Lond. 1967; 213:668–669. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald N. Trees and networks in biological models. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. [CrossRef]

- Mainster MA. The fractal properties of retinal vessels: embryological and clinical implicationsEye 1990; 4:235–241. [CrossRef]

- Turcotte DL, Pelletier JD, Newman WI. Networks with side branching in biology. J. Theor. Biol. 1998; 193:577–592. [CrossRef]

- Glenny, R.W. Emergence of matched airway and vascular trees from fractal rules. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011; 110:1119–1129. [CrossRef]

- Miguel AM. Dendritic design as an archetype for growth patterns in nature: fractal and constructal views. Front. Phys. 2014; 2:9. [CrossRef]

- Weibel ER, Gomez DM. Architecture of the human lung. Science 1962; 137: 577–585. [CrossRef]

- Weibel ER. Morphometry of the human lung. New York: Academic Press; 1963.

- Weibel ER. The pathways for oxygen: structure and function in the mammalian respiratory system. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1984.

- Losa GA. The fractal geometry of life. Riv. Biol. 2009; 102:29-59.

- Murray CD. The physiological principle of minimum work applied to the angle of branching of arteries. J. Gen. Physiol. 1926; 9:835–841. [CrossRef]

- Uylings HB. Optimization of diameters and bifurcation angles in lung and vascular tree structures. Bull. Math. Biol. 1977; 39:509–520. [CrossRef]

- Kassab GS. Scaling laws of vascular trees: of form and function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006; 290:H894–H903. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson D et al. Generalizing Murray’s law: an optimization principle for fluidic networks of arbitrary shape and scale. J. Appl. Phys. 2015; 118:174302. [CrossRef]

- Hughes AD. Optimality, cost minimization and the design of arterial networks. Artery Res. 2015; 10:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson D, Lockerby DA. A generalized optimization principle for asymmetric branching in fluidic networks. Proc. R. Soc. A 2016; 472:20160451. [CrossRef]

- Kamiya A, Takahashi T. Quantitative assessments of morphological and functional properties of biological trees based on their fractal nature. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007; 102:2315–2323. [CrossRef]

- West JB. Respiratory physiology: the essentials. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Gehr P, Bachofen M, Weibel ER. The normal human lung: ultrastructure and morphometric estimation of diffusion capacity. Respir. Physiol. 1978; 32:121–140. [CrossRef]

- Rao AA, Johncy S. Tennis courts in the human body: A review of the misleading metaphor in medical literature. Cureus 2022; 14:e21474. [CrossRef]

- Weibel ER. What makes a good lung? Swiss Med. Wkly. 2009; 139:375–386.

- Lefevre J. Teleonomical optimization of a fractal model of the pulmonary arterial bed. J. Theor. Biol. 1983; 102:225–248. [CrossRef]

- Miguel AF. A general model for optimal branching of fluidic networks. Physica A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2018; 512:665–674. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins SR. Ventilation/perfusion relationships and gas exchange: measurement approaches. Compr. Physiol. 2020; 10:1155–1205. [CrossRef]

- Powers KA, Dhamoon AS. Physiology, pulmonary ventilation and perfusion. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539907/.

- Metzger RJ, Krasnow MA. Genetic control of branching morphogenesis. Science 1999; 284:1635–1639. [CrossRef]

- Warburton D. Developmental biology: order in the lung. Nature 2008; 453:733–735.

- Warburton D et al. Growth factor signaling in lung morphogenetic centers automaticity, stereotypy and symmetry. Respir. Res. 2003; 19:294-315. [CrossRef]

- Metzger RJ et al. The branching programme of mouse lung development. Nature 2008; 453:745–750. [CrossRef]

- Hannezo E, Simons BD. Multiscale dynamics of branching morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2019; 60:99–105. [CrossRef]

- Burri PH. Lung development and pulmonary angiogenesis. In: Gaultier CJ, Post M, editors. Lung disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 122–151.

- Ochs M et al. The number of alveoli in the human lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004; 169, 120 –124. [CrossRef]

- Schittny JC, Burri PH. Development and growth of the lung. In: Fishman AP, Elias JA, Fishman JA, Grippi MA, Kaiser, Senior RM, editors. Fishman’s pulmonary diseases and disorders. New-York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 91–114.

- Schittny JC. Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 2017; 367:427–444.

- Pan H, Deutsch GH, Wert SE. Comprehensive anatomic ontologies for lung development: a comparison of alveolar formation and maturation within mouse and human lung. J. Biomed. Semantics 2019; 10:18. [CrossRef]

- Horsfield TK. Morphometry of the small pulmonary arteries in man. Circ. Res. 1978;42:593–597. [CrossRef]

- Horsfield K, Gordon WI. Morphometry of pulmonary veins in man. Lung 1981; 159:211-218. [CrossRef]

- Horsfield, K. Functional morphology of the pulmonary vasculature. In: Chang HK, Paiva MŽ, editors. Respiratory physiology: an analytical approach. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1989. pp. 499–531, 1989.

- Singhal S et al. Morphometry of the human pulmonary arterial tree. Circ. Res. 1973; 33:190–197. [CrossRef]

- Huang W et al. Morphometry of the human pulmonary vasculature. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996; 81:2123–2133. [CrossRef]

- Horsfield K, Cumming G. Morphology of the bronchial tree in man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1968; 24: 373–383. [CrossRef]

- Horsfield K, Relea FG, Cumming G. Diameter, length and branching ratios in the bronchial tree. Respir. Physiol. 1976; 26:351–356. [CrossRef]

- Thurlbeck A, Horsfield K. Branching angles in the bronchial tree related to order of branching. Respir. Physiol. 1980; 41:173–181. [CrossRef]

- Krenz GS, Linehan JH, Dawson CA. A fractal continuum model of the pulmonary arterial tree. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992; 72:2225–2237. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN, van Gils P. Morphometric characterization of the airway and vascular systems of the lung of the domestic pig, Sus scrofa: comparison of the airway, arterial and venous systems. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001; 1130:781–798. [CrossRef]

- Rashevsky N. Mathematical biophysics: physico-mathematical foundations of biology. New York: Dover; 1960.

- King AS. Structural and functional aspects of the avian lung and its air sacs. Intern. Rev. Gen. Exp. Zool. 1966; 2:171–267.

- Duncker HR. The lung-air sac system of birds. A contribution to the functional anatomy of the respiratory apparatus. Ergeb. Anat. Entwicklung 1971; 45:1–171.

- Scheid P. Mechanisms of gas exchange in bird lungs. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1979; 86:137–186, 1979. [CrossRef]

- McLelland J. Anatomy of the lungs and air sacs. In: King AS. McLelland J, editors. Form and function in birds, vol. IV. London: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 221–279.

- Maina JN. The lung-air sac system of birds: development, structure, and function. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2025. [CrossRef]

- Powell FL. Respiration. In: Scanes CG, editor. Sturkie’s avian physiology, 6th edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 301–336.

- King AS, McLelland J. Birds: their structure and function, 2nd edition. London: Bailliéle Tindall; 1984.

- Horsfield K. Diameters, generations, and orders of branches in the bronchial tree. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985; 68:457–461. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. A systematic study of the development of the airway (bronchial) system of the avian lung from days 3 to 26 of embryogenesis: a transmission electron microscopic study on the domestic fowl, Gallus gallus variant domesticus. Tissue Cell 2003: 35:375–391. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. Developmental dynamics of the bronchial (airway)- and air sac systems of the avian respiratory system from days 3 to 26 of life: A scanning electron microscopic study of the domestic fowl, Gallus gallus variant domesticus. Anat. Embryol. 2003; 207:119–134. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. The morphometry of the avian lung. In: King AS, McLelland J, editors. Form and function in birds, vol.4. London: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 307–368.

- Maina JN, King AS, Settle G. An allometric study of the pulmonary morphometric parameters in birds, with mammalian comparison. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1989; 326B:1–57. [CrossRef]

- West NH, Bamford OS, Jones DR. A scanning electron microscope study of the microvasculature of the avian lung. Cell Tissue Res. 1977; 176:553–564. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. Scanning electron microscopic study of the spatial organization of the air- and bloodconducting components of the avian lung (Gallus gallus domesticus). Anat. Rec. 1988; 222:145–153. [CrossRef]

- Abdalla MA. The blood supply to the lung. In: King AS, McLelland J, editors. Form and function in birds, vol. 4. London: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 281–306.

- Woodward JD, Maina JN. A 3D digital reconstruction of the components of the gas exchange tissue of the lung of the muscovy duck, Cairina moschata. J. Anat. 2005; 206:477–492. [CrossRef]

- Woodward JD, Maina JN. Study of the structure of the air and blood capillaries of the gas exchange tissue of the avian lung by serial section three-dimensional reconstruction. J. Microsc. 2008; 230:84–93. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN, Woodward JD. Three-dimensional serial section computer reconstruction of the arrangement of the structural components of the parabronchus of the ostrich, Struthio camelus. Anat. Rec. 2009; 292:1685–1698. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN et al. 3D Computer reconstruction of the airway and the vascular systems of the lung of the domestic fowl, Gallus gallus variant domesticus. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021; 5:89–104. [CrossRef]

- Thorpe WH, Crisp DJ. Studies on plastron respiration. II. The respiratory efficiency of the plastron in Amphelocheirus. J. Exp. Biol. 1941; 24:270–303. [CrossRef]

- Wigglesworth VB. Insect physiology, 7th edition. London: Chapman and Hall; 1984.

- Wigglesworth VB, Lee WM. The supply of oxygen to the flight muscles of insects: a theory of tracheole physiology. Tissue Cell 1982; 14:501–518. [CrossRef]

- Harrison JF. Tracheal system. In: Resh VH, Cardé RT, editors. Encyclopedia of insects, 2nd Edition. San Diego: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 1011–1015.

- Steen JB. Comparative physiology of respiratory mechanisms. London: Academic Press; 1971.

- Edwards GA, Ruska H, Harven de E. The fine structure of insect tracheoblasts, tracheae and tracheoles. Arch. Biol. 1958; 69:351–369.

- Centanin L, Gorr TA, Wappner P. Tracheal remodelling in response to hypoxia. J. Insect Physiol. 2010; 56:447–454. [CrossRef]

- Scheid P, Hook C. Bridges CR. Diffusion in gas exchange of insects. Fed. Proc. Fed. Am. Soc. Expl. Biol. 1982; 30:1032–1034.

- Snyder GK. et al. Gas exchange in the insect tracheal system. J. Theor. Biol. 1995; 172:199–207. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. A scanning and transmission electron microscopic study of the tracheal air-sac system in a grasshopper (Chrotogonus senegalensis, Kraus)- (Orthoptera: Acrididae: Pygomorphinae). Anat. Rec. 1989; 223:393–405. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. Comparative molecular developmental aspects of the mammalian- and the avian lungs, and the insectan tracheal system by branching morphogenesis: recent advances and future directions. Front. Zool. 2012; 9:16. [CrossRef]

- Samakovlis C. et al. Development of the Drosophila tracheal system occurs by a series of morphologically distinct but genetically coupled branching events. Development 1996; 122:1395–1407. [CrossRef]

- Affolter M, Caussinus E. Tracheal branching morphogenesis in Drosophila: new insights into cell behaviour and organ architecture. Development 2008; 135:2055–2064. [CrossRef]

- Graham JB. Air breathing fishes: evolution, diversity and adaptation. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997.

- Maina JN, Maloiy GMO. The morphology of the respiratory organs of the African air-breathing catfish (Clarias mossambicus): a light, and electron microscopic study, with morphometric observations. J. Zool. Lond. 1986; 209:421–445. [CrossRef]

- Mbanga B, van Dyk C. Maina JN. Morphometric and morphological study of therespiratory organs of the bimodally-breathing African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus): Burchell (1822). Zoology 2018; 130: 6–18. [CrossRef]

- Maina JN. Functional morphology of the respiratory organs of the air-breathing fish with particular emphasis on the African catfishes, Clarias mossambicus and C. gariepinus. Acta Histochem. 2018; 120:613–622. [CrossRef]

- Munshi JSD, Hughes GM. Air breathing fishes of india: their structure, function and life history. Rotterdam: AA Balkema Uitgevers; 1992.

- Dehadrai PV, Tripathi SD. Environment and ecology of freshwater air-breathing teleosts. In: Hughes GM, editor. Respiration of amphibious vertebrates. London: Academic Press; 39–72, 1976.

- Hughes GM, Munshi J.S.D. Fine structure of the respiratoty surfaces of an air-breathing fish, the climbing perch, Anabas testudineus (Bloch). Nature, Lond. 1968; 219:1382–1384. [CrossRef]

- Hughes GM, Singh BN. Respiration in air-breathing fish, the climbing perch, Anabas testudineus II. Respiratory patterns and the control of breathing. J. Exp. BioI. 1970; 53:281–298. [CrossRef]

- Coleman JR, Terepka AR. Fine structural changes associated with the onset of calcium, sodium and water transport by the chick chorioallantoic membrane. J. Membr. Biol. 1972; 7: 111–217. [CrossRef]

- Maksimov VF, Korostyshevskaya IM, Kurganov SA. Functional morphology of chorioallantoic vascular network in chicken. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006; 142:367–371. [CrossRef]

- Chien YC, Hincke MT, McKee MD. Ultrastructure of avian egg-shell during resorption following egg fertilization. J. Struct. Biol. 2009; 168:527–538. [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli MG, Accili D. The chick chorioallantoic membrane: a model of molecular, structural, and functional adaptation to transepithelial ion transport and barrier function during embryonic development. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010; 2010:940741, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Romanoff AL. The extraembryonic membranes. In: Romanoff AL, editors. The avian embryo: structural and functional development. New York: The Macmillan Company. 1960. pp. 1039–140, 1960.

- Makanya AN. et al. Dynamics of the developing chick chorioallantoic membrane assessed by stereology, allometry, immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis. PLoS One 2012; 11:e0152821. [CrossRef]

- Makanya AN, Jimoh SA, Maina JN. Methods of in ovo and ex ovo ostrich embryo culture with observations on the development and maturation of the chorioallantoic membrane. Microsc. Microanalysis 2023; 29:1523–1530. [CrossRef]

- Willoughby B. Morphological and morphometric study of the ostrich egg-shell with observations on the chorioallantoic membrane: a μct-, scanning electron microscope, and histological study. B.Sc. Honours Dissertation, University of Johannesburg; 2015.

- Maina JN. Structure and function of the shell and the chorioallantoic membrane of the avian egg: embryonic respiration. In: Maina JN editor. The biology of the avian respiratory system.Cham (Switzerland): Springer; 2017. pp. 219–247. [CrossRef]

- Makanya AN. et al. Microvascular endowment in the developing chicken embryo lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007; 292:L1136–46. [CrossRef]

- Willoughby B et al. Micro-focus X-ray tomography study of the microstructure and morphometry of the egg-shell of ostriches (Struthio camerus). Anat. Rec. 2016; 299:1015–1026. [CrossRef]

- Hughes GM, Morgan M. The structure of the gills in relation to their respiratory function. Biol. Rev. 1973; 48:419–475. [CrossRef]

- Laurent P. Morphology and physiology of organs of aquatic respiration in vertebrates: the gill. J. Physiol. 1984; 79:98 –112.

- Maina JN. A study of the morphology of the gills of an extreme alkalinity and hyperosmotic adapted teleost Oreochromis alcalicus grahami (Boulenger) with particular emphasis on the ultrastructure of the chloride cells and their modifications with water dilution. Anat. Embryol. 1990; 181:83–98. [CrossRef]

- Wilson JM, Laurent P. Fish gill morphology: inside out. J. Exp. Zool. 2002; 293:192–213. [CrossRef]

- Evans DH, Piermarini PM, Choe KP. The multifunctional fish gill: dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid-base regulation, and excretion of nitrogenous waste. Physiol. Rev. 2005; 85:97–177. [CrossRef]

- Wegner NC, Farrell AP. Plasticity in gill morphology and function. In: Alderman SL, Gillis TE, editors. Encyclopedia of fish physiology, 2nd edition. Academic Press, Oxford, 762–779, 2024.

- Noffke N et al.. Microbially induced sedimentally structures recording an ancient ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 billion-year-old dresser formation, Pilbara, Western Australia. Astrobiology 2013; 13:1103–1124. [CrossRef]

- Ohtomo Y. et al. Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks. Nature Geoscience 2014; 7:25–28. [CrossRef]

- Fish FE. Biomimetics: Determining engineering opportunities from nature. In: Martín-Palma RJ, Lakhtakia A, editors. Biomimetics and bioinspiration. Proc. of SPIE 2017; 7401:740109, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Williams H. Biomimicry in bioengineering: learning from nature to engineer better solutions. Bio. Eng. Bio. Electron. 2024; 6:03.

- Valenzuela C. Nature's solutions: biomimetics and sustainable technology. J. Biomed. Syst.Emerg. Technol. 2024; 11:02.

- In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Mechanics, Electronics Engineering and Automation (ICMEEA 2024) AER 240; Yue Y (ed.). Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Mechanics, Electronics Engineering and Automation (ICMEEA 2024). AER 240. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy EM, Marting TA. Biomimicry: streamlining the front end of innovation for environmentally sustainable products: biomimicry can be a powerful design tool to support sustainability-driven product development in the front end of innovation. RTM 2016; 59:40-48. [CrossRef]

- Kantaros A. et al. Biomimetic additive manufacturing: engineering complexity inspired bynature’s simplicity. Biomimetics 2025; 10:453. [CrossRef]

- West BJ. Physiology in fractal dimensions: error tolerance. Ann. Biomed. Engineer. 1090; 18: 135–149. [CrossRef]

- Zueva MV. Fractality of sensations and the brain health: the theory linking neurodegenerative disorder with distortion of spatial and temporal scale-invariance and fractal complexity of the visible world. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7:135. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rico M et al. Fractal dimension reveals cellular morphological changes as early biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases: a narrative review. NeuroMarkers 2025; 2:100108. [CrossRef]

- Tanabe N et al. Fractal analysis of lung structure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front. Physiol. 2020; 11:603197. [CrossRef]

- John AM et al. The utility of fractal analysis in clinical neuroscience. Rev. Neurosci. 2015; 26:633-645.

- Uahabi KL, Atounti M. Applications of fractals in medicine. Annals of the University of Craiova, Mathematics and Computer Science Series 2015; 42:167174.

- Pirri C et al.. The value of fractal analysis in ultrasound imaging: exploring intricate patterns. Appl. Sci. 2024; 14:9750. [CrossRef]

- Marusina MY et al.. MRI image processing based on fractal analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017; 18:51-55. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz de Miras J et al.. Fractal dimension analysis of resting state functional networks in schizophrenia from EEG signals. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023; 17:1236832. [CrossRef]

- Albertovich TD, Rusanova IA. The fractal analysis of the images and signals in medical diagnostics: fractal analysis - applications in health sciences and social sciences. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Paun MA et al.. Fractal analysis in the quantification of medical imaging associated with multiple sclerosis pathology. Front. Biosci. 2022; 27:66. [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra K, Selvakumar R. Fractal dimension and entropy analysis of medical images for KNN-based disease classification. Baghdad Sci. J. 2025; 22: 27. [CrossRef]

- Yoder KJ et al.. Fractal dimension distributions of resting-state electroencephalography(EEG) improve detection of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease compared to traditional fractal analysis. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2024; 8:27. [CrossRef]

- Bayrak EA, Kirci P. Fractal analysis usage areas in healthcare. In: Zgurovsky M, Pankratova N, editors. System analysis and intelligent computing. SAIC 2020. Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol. 1022. Cham (Switzerland): Springer; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ziukelis ET et al. Fractal dimension of the brain in neurodegenerative disease and dementia: a systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022; 79:101651. [CrossRef]

- Li P et al. Interaction between the progression of Alzheimer's disease and fractal degradation. Neurobiol. Aging 2019; 83:21-30. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).