Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

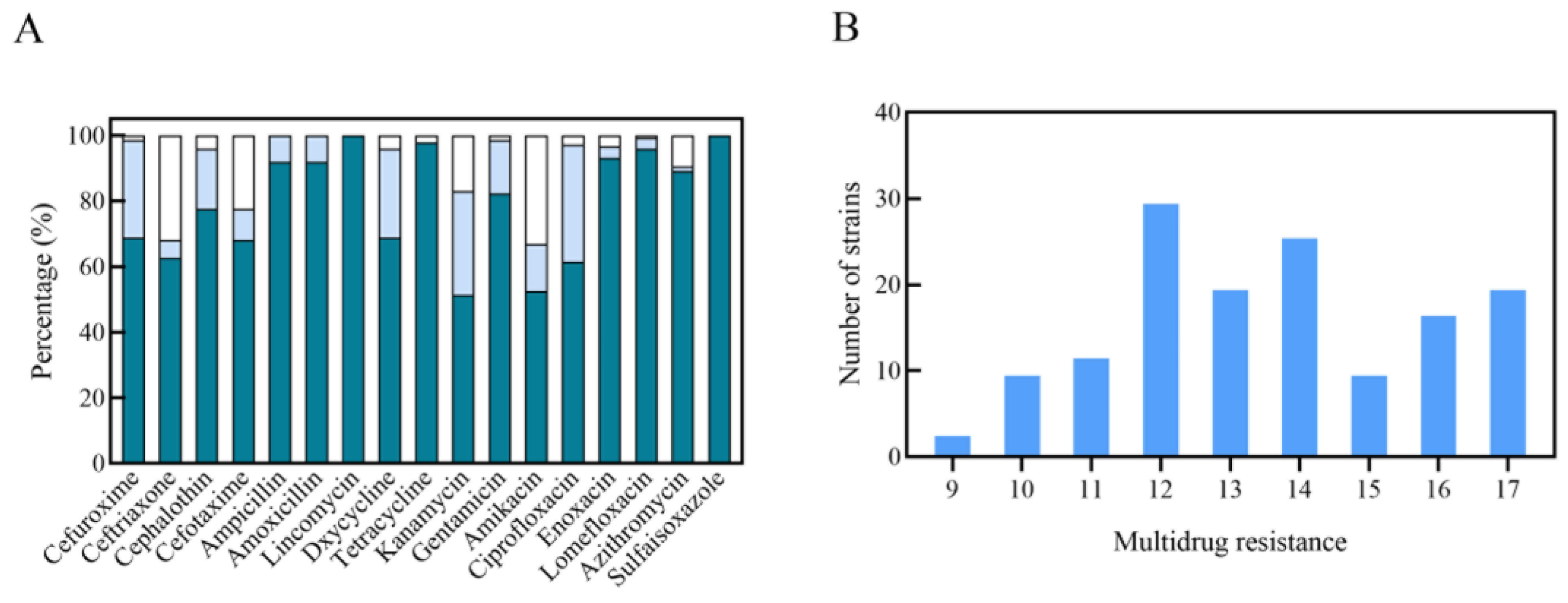

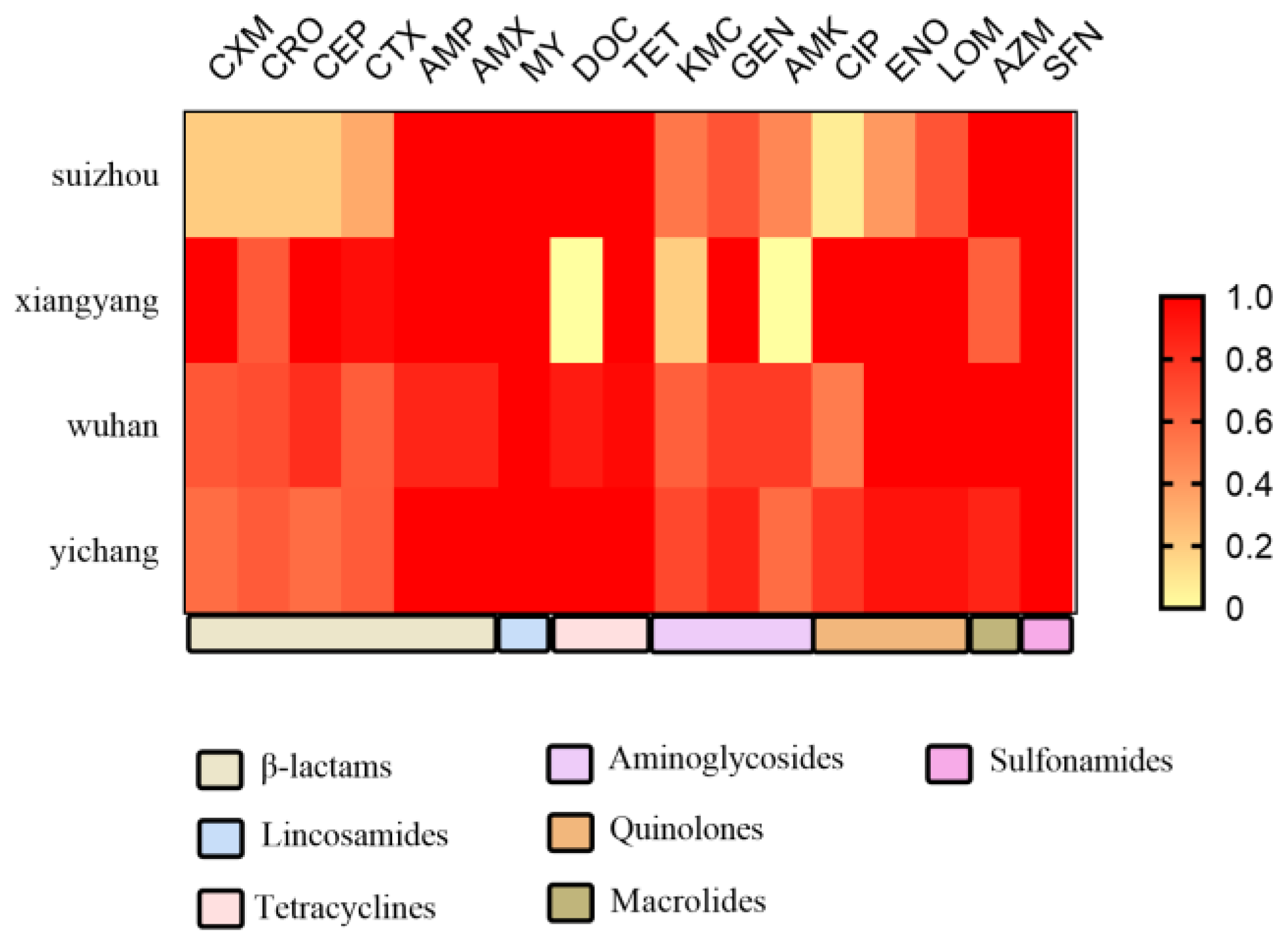

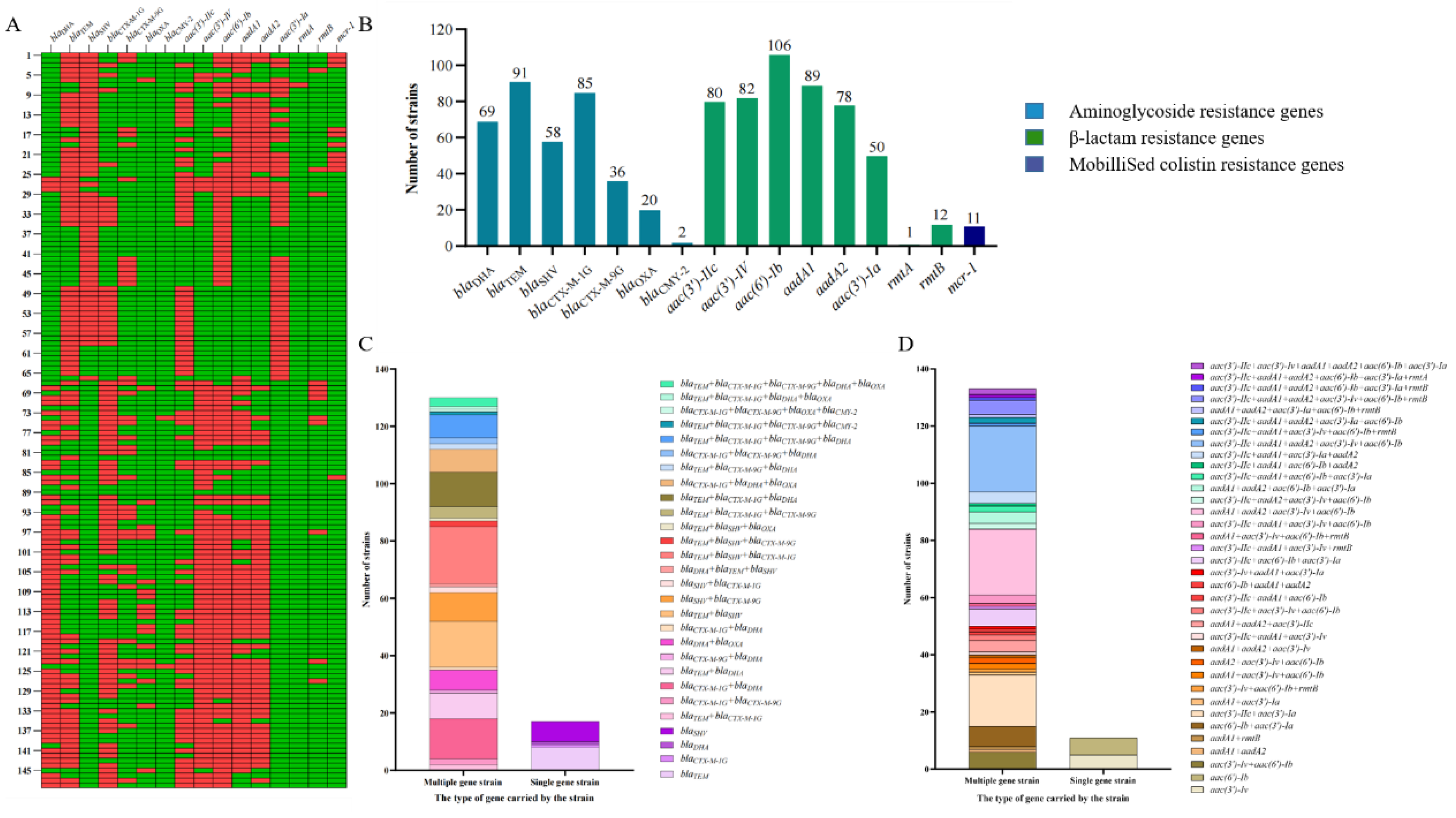

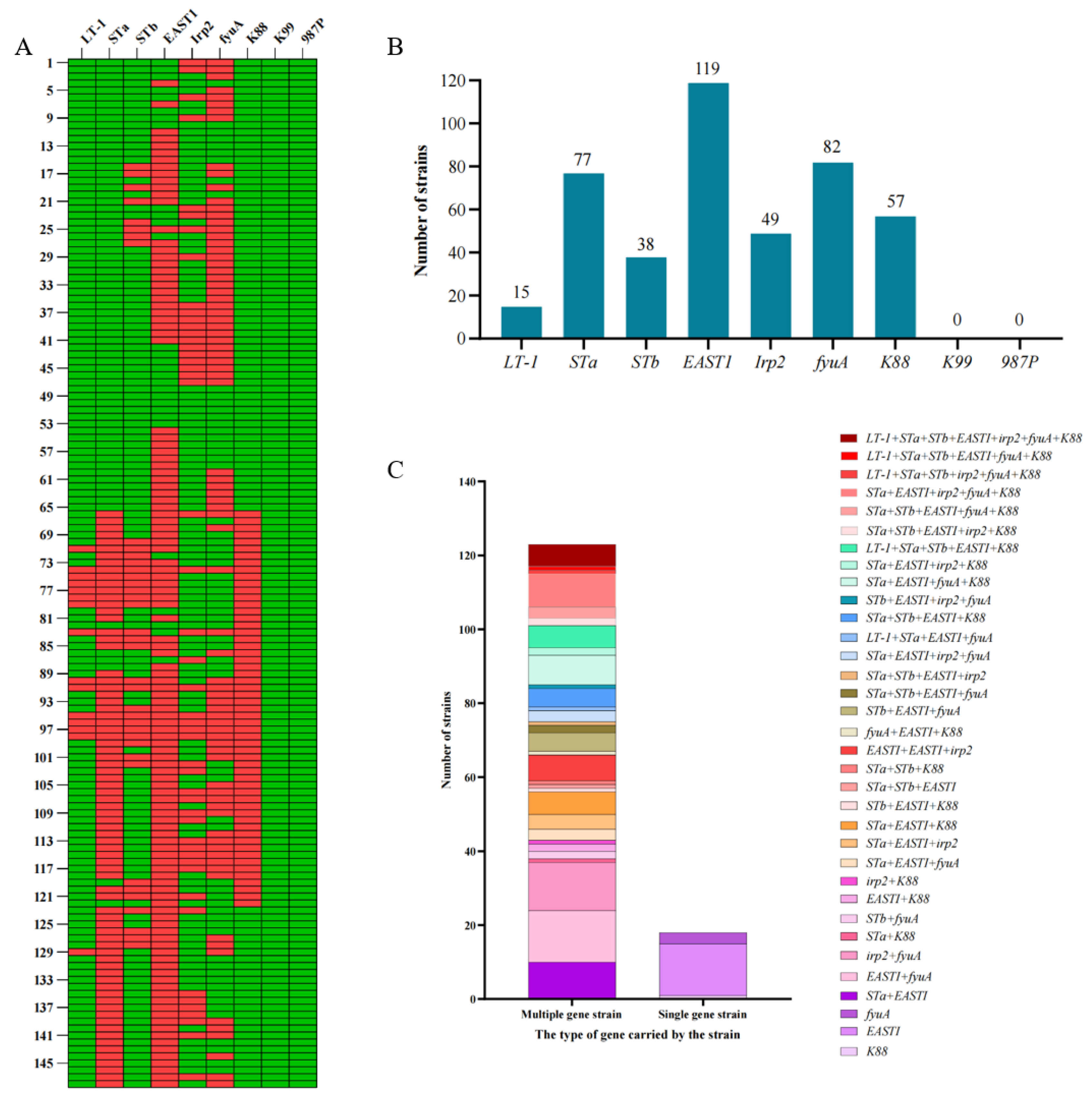

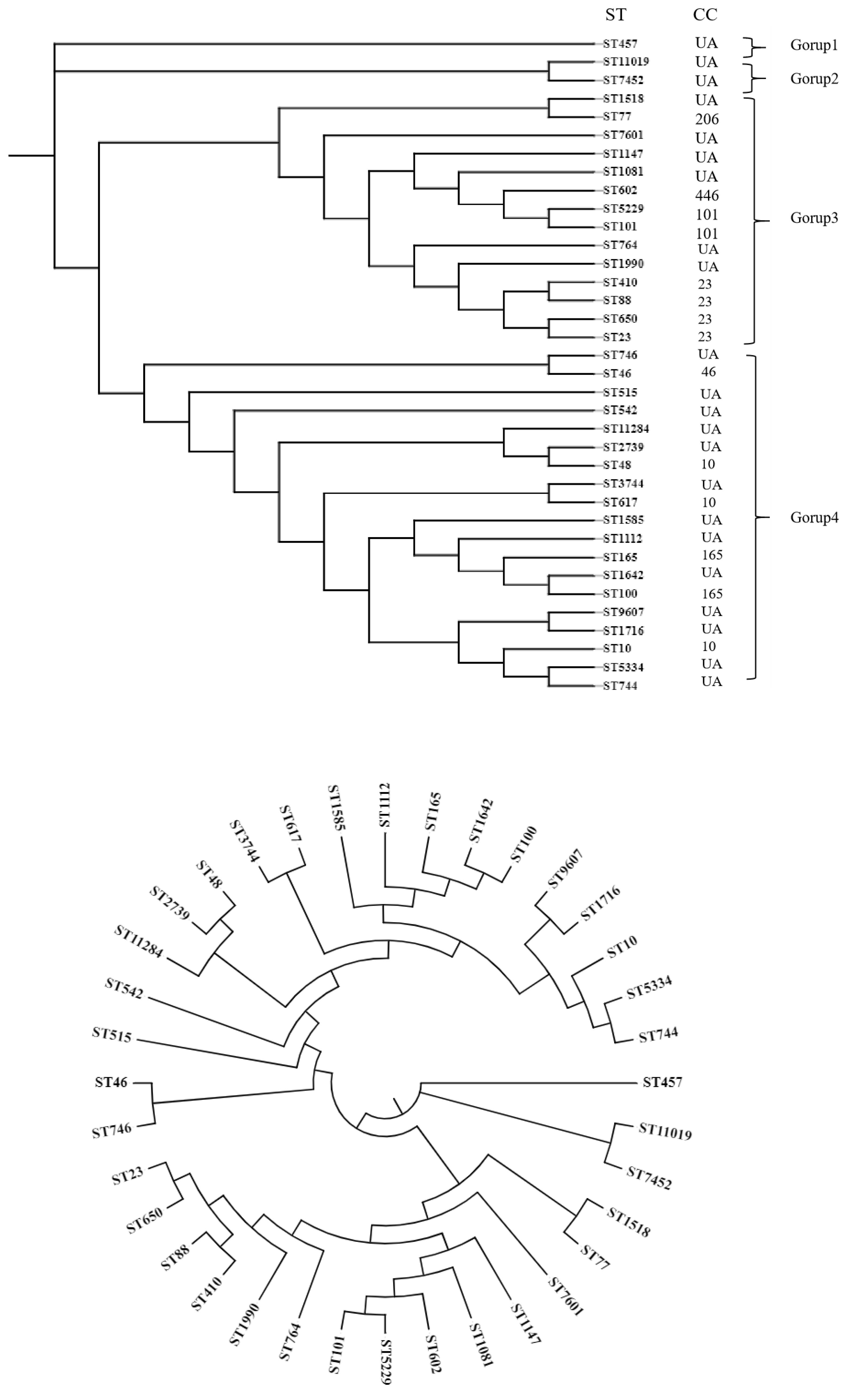

The indiscriminate and excessive use of antimicrobial agents in livestock production constitutes a significant contributor to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), posing substantial threats to global public health. Despite this critical concern, the genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance patterns of Escherichia coli (E. coli) in regional ecosystems remain insufficiently characterized. This study investigated the prevalence of antibiotic resistance, transmission mechanisms, and molecular epidemiology of E. coli strains isolated from swine farms in Hubei Province, China, while simultaneously analyzing their clonal and genetic diversity. A total of 148 E. coli isolates were collected from porcine sources in central China, revealing distinct regional variations in genetic diversity. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis identified 38 sequence types (STs) distributed across 7 clonal complexes (CCs) and several unassigned clones. ST46 emerged as the predominant sequence type (19.6% prevalence), followed by ST23 and ST10. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing demonstrated universal resistance to lincosamides and sulfonamides, with all isolates exhibiting multidrug resistance (MDR) to ≥9 antimicrobial classes. Genetic characterization detected 16 resistance determinants, with individual isolates carrying 5-7 resistance genes on average. The resistance profile included:Seven β-lactamase genes: blaTEM (61.5%), blaCTX-M-1G (57.4%), blaDHA (46.6%), blaSHV (39.2%), blaCTX-M-9G (24.3%), blaOXA (13.5%), and blaCMY-2 (1.4%). Eight aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes, polymyxin resistance gene mcr-1 (7.4%).Virulence factor screening through PCR detected nine associated genes, with EAST1, fyuA, STa, K88, STb, Irp2, and LT-1 present in 95.3% of isolates, while K99 and 987P were absent in all specimens. This investigation documents alarmingly high antimicrobial resistance rates in swine-derived E. coli populations while elucidating their genetic diversity. The findings suggest that intensive antibiotic use in porcine production systems has driven the evolution of extensively drug-resistant bacterial strains. These results emphasize the urgent need for implementing antimicrobial stewardship programs in livestock management to mitigate AMR proliferation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Isolation of E. coli

Antibiotic Resistance Profiles

Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes

Detection of Virulence-Associated Genes

MLST and Phylogenetic Tree

Statistics Analysis

3. Result

Isolation of E. coli Strains and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profile of E. coli Isolates

Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

Various Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Genes Were Present in the Isolates

Various Extended-Spectrum Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzyme Genes Were Present in the Isolates

Prevalence of Virulence Genes in E. coli Isolates from Pigs

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST)

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marques C, Belas A, Franco A, Aboim C, Gama LT, Pomba C. Increase in antimicrobial resistance and emergence of major international high-risk clonal lineages in dogs and cats with urinary tract infection: 16 year retrospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(2):377-84;. [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother JM, Nadeau E, Gyles CL. Escherichia coli in postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Anim Health Res Rev. 2005;6(1):17-39;. [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara M, Clark AE, Wolk DM, Carman A, Rosenbaum PF, Shaw J. Molecular Characterization of Invasive Staphylococcus aureus Infection in Central New York Children: Importance of Two Clonal Groups and Inconsistent Presence of Selected Virulence Determinants. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2013;2(1):30-9;. [CrossRef]

- Moore JE, Watabe M, Millar BC, Rooney PJ, Loughrey A, Goldsmith CE. Direct molecular (PCR) detection of verocytotoxigenic and related virulence determinants (eae, hyl, stx) in E. coli O157:H7 from fresh faecal material. Br J Biomed Sci. 2008;65(3):163-5;. [CrossRef]

- Casey WT, McClean S. Exploiting molecular virulence determinants in Burkholderia to develop vaccine antigens. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22(14):1719-33;. [CrossRef]

- Yang SC, Lin CH, Aljuffali IA, Fang JY. Current pathogenic Escherichia coli foodborne outbreak cases and therapy development. Arch Microbiol. 2017;199(6):811-25;. [CrossRef]

- Beasley DW, Davis CT, Whiteman M, Granwehr B, Kinney RM, Barrett AD. Molecular determinants of virulence of West Nile virus in North America. Arch Virol Suppl. 2004;(18):35-41;. [CrossRef]

- Umpierrez A, Bado I, Oliver M, Acquistapace S, Etcheverria A, Padola NL, et al. Zoonotic Potential and Antibiotic Resistance of Escherichia coli in Neonatal Calves in Uruguay. Microbes Environ. 2017;32(3):275-82;. [CrossRef]

- Enne VI, Cassar C, Sprigings K, Woodward MJ, Bennett PM. A high prevalence of antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli isolated from pigs and a low prevalence of antimicrobial resistant E. coli from cattle and sheep in Great Britain at slaughter. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;278(2):193-9;. [CrossRef]

- Tauch A, Burkovski A. Molecular armory or niche factors: virulence determinants of Corynebacterium species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015;362(23):fnv185;. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Sun YH, Wang JY, Chang MX, Zhao QY, Jiang HX. A Novel Structure Harboring blaCTX-M-27 on IncF Plasmids in Escherichia coli Isolated from Swine in China. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(4);. [CrossRef]

- De Waele JJ, Boelens J, Leroux-Roels I. Multidrug-resistant bacteria in ICU: fact or myth. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2020;33(2):156-61;. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho I, Tejedor-Junco MT, Gonzalez-Martin M, Corbera JA, Suarez-Perez A, Silva V, et al. Molecular diversity of Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from vultures in Canary Islands. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2020;12(5):540-7;. [CrossRef]

- Ghafourian S, Sadeghifard N, Soheili S, Sekawi Z. Extended Spectrum Beta-lactamases: Definition, Classification and Epidemiology. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2015;17:11-21.

- Peirano G, Pitout JDD. Extended-Spectrum beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: Update on Molecular Epidemiology and Treatment Options. Drugs. 2019;79(14):1529-41;. [CrossRef]

- Cheng P, Yang Y, Cao S, Liu H, Li X, Sun J, et al. Prevalence and Characteristic of Swine-Origin mcr-1-Positive Escherichia coli in Northeastern China. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:712707;. [CrossRef]

- Hu Z, Peng Z, Zhang X, Li Z, Jia C, Li X, et al. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia coli in Pig Farms, Slaughterhouses, and Terminal Markets in Henan Province of China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2021;18(10):733-43;. [CrossRef]

- Barros MM, Castro J, Araujo D, Campos AM, Oliveira R, Silva S, et al. Swine Colibacillosis: Global Epidemiologic and Antimicrobial Scenario. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12(4);. [CrossRef]

- Tran-Mai AP, Tran HT, Mai QG, Huynh KQ, Tran TL, Tran-Van H. Flagellin from Salmonella enteritidis Enhances the Immune Response of Fused F18 from Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Trop Life Sci Res. 2022;33(3):19-32;. [CrossRef]

- Luo X, Wu S, Jia H, Si X, Song Z, Zhai Z, et al. Resveratrol alleviates enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88-induced damage by regulating SIRT-1 signaling in intestinal porcine epithelial cells. Food Funct. 2022;13(13):7346-60;. [CrossRef]

- Jerez-Bogota K, Jensen M, Hojberg O, Cormican P, Lawlor PG, Gardiner GE, et al. Antibacterial plant combinations prevent postweaning diarrhea in organically raised piglets challenged with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli F18. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1095160;. [CrossRef]

- Fiil BK, Thrane SW, Pichler M, Kittila T, Ledsgaard L, Ahmadi S, et al. Orally active bivalent V(H)H construct prevents proliferation of F4(+) enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in weaned piglets. iScience. 2022;25(4):104003;. [CrossRef]

- Duan Q, Wu W, Pang S, Pan Z, Zhang W, Zhu G. Coimmunization with Two Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Fimbrial Multiepitope Fusion Antigens Induces the Production of Neutralizing Antibodies against Five ETEC Fimbriae (F4, F5, F6, F18, and F41). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86(24);. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Duan Q, Zhang W. Significance of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Heat-Labile Toxin (LT) Enzymatic Subunit Epitopes in LT Enterotoxicity and Immunogenicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84(15);. [CrossRef]

- Joffre E, Sjoling A. The LT1 and LT2 variants of the enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) heat-labile toxin (LT) are associated with major ETEC lineages. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(1):75-81;. [CrossRef]

- Tobias J, Von Mentzer A, Loayza Frykberg P, Aslett M, Page AJ, Sjoling A, et al. Stability of the Encoding Plasmids and Surface Expression of CS6 Differs in Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) Encoding Different Heat-Stable (ST) Enterotoxins (STh and STp). PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152899;. [CrossRef]

- Vereecke N, Van Hoorde S, Sperling D, Theuns S, Devriendt B, Cox E. Virotyping and genetic antimicrobial susceptibility testing of porcine ETEC/STEC strains and associated plasmid types. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1139312;. [CrossRef]

- Guerra JA, Romero-Herazo YC, Arzuza O, Gomez-Duarte OG. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli clinical isolates from northern Colombia, South America. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:236260;. [CrossRef]

- Yun KW, Kim DS, Kim W, Lim IS. Molecular typing of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from Korean children with urinary tract infection. Korean J Pediatr. 2015;58(1):20-7;. [CrossRef]

- Yang GY, Guo L, Su JH, Zhu YH, Jiao LG, Wang JF. Frequency of Diarrheagenic Virulence Genes and Characteristics in Escherichia coli Isolates from Pigs with Diarrhea in China. Microorganisms. 2019;7(9);. [CrossRef]

- Noah DL, Krug RM. Influenza virus virulence and its molecular determinants. Adv Virus Res. 2005;65:121-45;. [CrossRef]

- Song H, Santi N, Evensen O, Vakharia VN. Molecular determinants of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus virulence and cell culture adaptation. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10289-99;. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Wang L, Zhou Y, Miao Z. Prevalence and characterization of virulence genes in Escherichia coli isolated from piglets suffering post-weaning diarrhoea in Shandong Province, China. Vet Med Sci. 2020;6(1):69-75;. [CrossRef]

- Osman KM, Mustafa AM, Aly MA, AbdElhamed GS. Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from mastitic milk relevant to human health in Egypt. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12(4):297-305;. [CrossRef]

- Cheng D, Sun H, Xu J, Gao S. PCR detection of virulence factor genes in Escherichia coli isolates from weaned piglets with edema disease and/or diarrhea in China. Vet Microbiol. 2006;115(4):320-8;. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Yuan C, Meng X, Du Y, Gao R, Tang J, et al. Frequency of virulence factors in Escherichia coli isolated from suckling pigs with diarrhoea in China. Vet J. 2014;199(2):286-9;. [CrossRef]

- Zhao S, Blickenstaff K, Bodeis-Jones S, Gaines SA, Tong E, McDermott PF. Comparison of the prevalences and antimicrobial resistances of Escherichia coli isolates from different retail meats in the United States, 2002 to 2008. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(6):1701-7;. [CrossRef]

- Zhao QY, Li W, Cai RM, Lu YW, Zhang Y, Cai P, et al. Mobilization of Tn1721-like structure harboring blaCTX-M-27 between P1-like bacteriophage in Salmonella and plasmids in Escherichia coli in China. Vet Microbiol. 2021;253:108944;. [CrossRef]

- Hatta M, Kawaoka Y. [Molecular determinants associated with high virulence of influenza A virus]. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso. 2007;52(10 Suppl):1237-41.

- Tadesse DA, Zhao S, Tong E, Ayers S, Singh A, Bartholomew MJ, et al. Antimicrobial drug resistance in Escherichia coli from humans and food animals, United States, 1950-2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(5):741-9;. [CrossRef]

- Brand P, Gobeli S, Perreten V. Pathotyping and antibiotic resistance of porcine enterovirulent Escherichia coli strains from Switzerland (2014-2015). Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2017;159(7):373-80;. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H-X, Lü D-H, Chen Z-L, Wang X-M, Chen J-R, Liu Y-H, et al. High prevalence and widespread distribution of multi-resistant Escherichia coli isolates in pigs and poultry in China. The Veterinary Journal. 2011;187(1):99-103;. [CrossRef]

- Zhang A, He X, Meng Y, Guo L, Long M, Yu H, et al. Antibiotic and Disinfectant Resistance of Escherichia coli Isolated from Retail Meats in Sichuan, China. Microb Drug Resist. 2016;22(1):80-7;. [CrossRef]

- Zhang P, Shen Z, Zhang C, Song L, Wang B, Shang J, et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance among Escherichia coli from chicken and swine, China, 2008-2015. Vet Microbiol. 2017;203:49-55;. [CrossRef]

- Poirel L, Madec JY, Lupo A, Schink AK, Kieffer N, Nordmann P, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr. 2018;6(4);. [CrossRef]

- Gelalcha BD, Kerro Dego O. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases Producing Enterobacteriaceae in the USA Dairy Cattle Farms and Implications for Public Health. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(10);. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan M, Ramachandran B, Barabadi H. The prevalence and drug resistance pattern of extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) producing Enterobacteriaceae in Africa. Microb Pathog. 2018;114:180-92;. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik AF, Alswailem AM, Shibl AM, Al-Agamy MH. Prevalence and genetic characteristics of TEM, SHV, and CTX-M in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Saudi Arabia. Microb Drug Resist. 2011;17(3):383-8;. [CrossRef]

- Dirar MH, Bilal NE, Ibrahim ME, Hamid ME. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and molecular detection of blaTEM, blaSHV and blaCTX-M genotypes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates from patients in Khartoum, Sudan. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:213;. [CrossRef]

- Yu B, Zhang Y, Yang L, Xu J, Bu S. Analysis of antibiotic resistance phenotypes and genes of Escherichia coli from healthy swine in Guizhou, China. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2021;88(1):e1-e8;. [CrossRef]

- Perez F, Endimiani A, Hujer KM, Bonomo RA. The continuing challenge of ESBLs. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7(5):459-69;. [CrossRef]

- Gad GF, Mohamed HA, Ashour HM. Aminoglycoside resistance rates, phenotypes, and mechanisms of Gram-negative bacteria from infected patients in upper Egypt. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17224;. [CrossRef]

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161-8;. [CrossRef]

- Hussein NH, Al-Kadmy IMS, Taha BM, Hussein JD. Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: a comprehensive review. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(3):2897-907;. [CrossRef]

- Moosavian M, Emam N. The first report of emerging mobilized colistin-resistance (mcr) genes and ERIC-PCR typing in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates in southwest Iran. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1001-10;. [CrossRef]

- Luppi A. Swine enteric colibacillosis: diagnosis, therapy and antimicrobial resistance. Porcine Health Manag. 2017;3:16;. [CrossRef]

- Kwon D, Choi C, Jung T, Chung HK, Kim JP, Bae SS, et al. Genotypic prevalence of the fimbrial adhesins (F4, F5, F6, F41 and F18) and toxins (LT, STa, STb and STx2e) in Escherichia coli isolated from postweaning pigs with diarrhoea or oedema disease in Korea. Vet Rec. 2002;150(2):35-7;. [CrossRef]

- Do TN, Cu PH, Nguyen HX, Au TX, Vu QN, Driesen SJ, et al. Pathotypes and serogroups of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from pre-weaning pigs in north Vietnam. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 1):93-9;. [CrossRef]

- Yu T, He T, Yao H, Zhang JB, Li XN, Zhang RM, et al. Prevalence of 16S rRNA Methylase Gene rmtB Among Escherichia coli Isolated from Bovine Mastitis in Ningxia, China. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12(9):770-7;. [CrossRef]

- Pai H, Seo MR, Choi TY. Association of QnrB determinants and production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases or plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(1):366-8;. [CrossRef]

- Yan JJ, Hong CY, Ko WC, Chen YJ, Tsai SH, Chuang CL, et al. Dissemination of blaCMY-2 among Escherichia coli isolates from food animals, retail ground meats, and humans in southern Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(4):1353-6;. [CrossRef]

- Weill FX, Demartin M, Tande D, Espie E, Rakotoarivony I, Grimont PA. SHV-12-like extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing strains of Salmonella enterica serotypes Babelsberg and Enteritidis isolated in France among infants adopted from Mali. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(6):2432-7;. [CrossRef]

- Brinas L, Moreno MA, Teshager T, Saenz Y, Porrero MC, Dominguez L, et al. Monitoring and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli strains from healthy and sick animals in Spain in 2003. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(3):1262-4;. [CrossRef]

- Liu JH, Wei SY, Ma JY, Zeng ZL, Lu DH, Yang GX, et al. Detection and characterisation of CTX-M and CMY-2 beta-lactamases among Escherichia coli isolates from farm animals in Guangdong Province of China. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29(5):576-81;. [CrossRef]

- Colom K, Pérez J, Alonso R, Fernández-Aranguiz A, Lariño E, Cisterna Rn. Simple and reliable multiplex PCR assay for detection of blaTEM, blaSHV and blaOXA-1 genes in Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2003;223(2):147-51;. [CrossRef]

- Sun N, Liu JH, Yang F, Lin DC, Li GH, Chen ZL, et al. Molecular characterization of the antimicrobial resistance of Riemerella anatipestifer isolated from ducks. Vet Microbiol. 2012;158(3-4):376-83;. [CrossRef]

- Park CH, Robicsek A, Jacoby GA, Sahm D, Hooper DC. Prevalence in the United States of aac(6’)-Ib-cr encoding a ciprofloxacin-modifying enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(11):3953-5;. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Zhao S, White DG, Schroeder CM, Lu R, Yang H, et al. Characterization of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant salmonella serovars isolated from retail meats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(1):1-7;. [CrossRef]

drug resistance rate;

drug resistance rate;  drug intermediation rate;

drug intermediation rate;  drug sensitivity rate).

drug sensitivity rate).

drug resistance rate;

drug resistance rate;  drug intermediation rate;

drug intermediation rate;  drug sensitivity rate).

drug sensitivity rate).

| Genes | Primer sequence (5 ʹ -3 ʹ) | Size of product (base pairs) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| blaDHA | F: AACTTTCACAGGTGTGCTGT R: CCGTACGCATACTGGCTTTC |

387 | Pai, Seo & Choi, 2007[60] |

| blaCMY-2 | F: ATGATGAAAAAATCGTTATGC R: TTGCAGCTTTTCAAGAATGCG |

1143 | Yan et al. 2004[61] |

| blaTEM | F: ATAAAATTCTTGAAGACGAAA R: GACAGTTACCAATGCTTAATC |

1080 | Weill et al. 2004[62] |

| blaSHV | F: CACTCAAGGATGTATTGTG R: TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG |

885 | Brinas et al. 2005[63] |

| blaCTX-M-1G | F: CTTCCAGAATAAGGAATCCC R: CGTCTAAGGCGATAAACAAA |

949 | Liu et al. 2007[64] |

| blaCTX-M-9G | F: TGACCGTATTGGGAGTTTG R: ACCAGTTACAGCCCTTCG |

902 | Liu et al. 2007[64] |

| blaOXA | F: ATATCTCTACTGTTGCATCTCC R: AAACCCTTCAAACCATCC |

619 | Colom et al. 2003[65] |

| aac(3′)-Ia | F: TTACGCAGCAGCAACGATGT R: GTTGGCCTCATGCTTGAGGA |

402 | Sun et al. 2012[66] |

| aac(3′)-IIc | F: AACCGGTGACCTATTGATGG R: TGTGCTGGCACGATCGGAGT |

774 | Sun et al. 2012[66] |

| aac(3′)-IV | F: GGCCACTTGGACTGATCGAG R: GCGGATGCAGGAAGATCAAC |

609 | Sun et al. 2012[66] |

| aac(6′)-Ib | F: TTGCGATGCTCTATGAGTGGCTA R: CTCGAATGCCTGGCGTGTTT |

482 | Park et al. 2006[67] |

| aadA1 | F: AGGTAGTTGGCGTCATCGAG R: CAGTCGGCAGCGACATCCTT |

589 | Sun et al. 2012[66] |

| aadA2 | F: GGTGCTAAGCGTCATTGAGC R: GCTTCAAGGTTTCCCTCAGC |

470 | Sun et al. 2012[66] |

| rmtA | F: CTAGCGTCCATCCTTTCCTC R: TTGCTTCCATGCCCTTGCC |

635 | Chen et al. 2004[68] |

| rmtB | F: ACATCAACGATGCCCTCAC R: AAGTTCTGTTCCGATGGTC |

724 | Chen et al. 2004[68] |

| mcr-1 | F: CGGTCAGTCCGTTTGTTC R: CTTGGTCGGTCTGTAGGG |

309 | Liu et al. 2016[53] |

| Virulence factors | Primer sequence (5 ʹ -3 ʹ) | Size of product (base pairs) |

|---|---|---|

| LT-1 | F: TAGAGACCGGTATTACAGAAATCTGA | 282 |

| R: TCATCCCGAATTCTGTTATATATGTC | ||

| STa | F: GGGTTGGCAATTTTTATTTCTGTA | 183 |

| R: ATTACAACAAAGTTCACAGCAGTA | ||

| STb | F: ATGTAAATACCTACAACGGGTGAT | 300 |

| R: TATTTGGGCGCCAAAGCATGCTCC | ||

| EAST1 | F: ATGCCATCAACACAGTATATC | 117 |

| R: TCAGGTCGCGAGTGACGG | ||

| irp2 | F: AAGGATTCGCTGTTACCGGAC | 301 |

| R: TCGTCGGGCA GCGTTTCTTCT | ||

| fyuA | F: TGATTAACCCCGCGACGGGAA | 787 |

| R: CGCAGTAGGCACGATGTTGTA | ||

| K88 | F: GATGAAAAAGACTCTGATTGCA | 841 |

| R: GATTGCTACGTTCAGCGGAGCG | ||

| K99 | F: CTGAAAAAAACACTGCTAGCTATT | 543 |

| R: CATATAAGTGACTAAGAAGGATGC | ||

| 987P | F: GTTACTGCCAGTCTATGCCAAGTG | 463 |

| R: TCGGTGTACCTGCTGAACGAATAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).