1. Introduction

Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), belonging to the family of

Picornaviridae, is a human enterovirus that contains small RNA molecule as a genome. Human enteroviruses are classified into 4 different species,

Enterovirus A to

D are ubiquitous infection agents and infect many organs from the human body systems. Coxsackieviruses (CVB) are mainly transmitted by fecal oral route [

1]. Infections by CVB are highly prevalent but are usually subclinical or cause a mild flu-like illness. The association of CVB with heart and pancreas diseases is evident. Several studies demonstrated that CVB are the most common cause of acute viral myocarditis, pancreatitis, Type 1 diabetes (T1D) and chronic cardiomyopathy [

2,

3]. The genome of CVB3 is a positive-stranded RNA segment with approximately 7500 nucleotides long. The single ORF (Open Reading Frame) is flanked by a 5’ non-translated Region (5’NTR) and a 3’NTR which terminates in a poly (A) tract. The two regions in 5’NTR and 3’NTR are highly conserved among the RNA sequence and structure. These regions have been revealed important for virus replication, translation and pathogenesis. The viral genome of CVB3 encodes for a single ORF (Open Reading Frame) to finally synthetize during translation a viral polyprotein constituted by 2185 amino acids. This polyprotein is cleaved by viral enzymes into viral sub-proteins P1, P2 and P3. Sub-proteins are cleaved then by viral proteases to produce several structural viral proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3 andVP4) and viral enzymes. The structural proteins VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4 form protomers and five of these protomers assemble into a pentamer. Finally, an icosahedral capsid approximately 30 nm in diameter consists of 12 pentamers. Whereas VP4 is an internal protein, VP1, VP2 and VP3 are exposed on the particle surface [

4,

5]. Several studies revealed that VP1 viral protein is the most exposed on viral capsid and contains the most and major neutralization epitopes and virulence determinants [

6,

7]. This viral protein have been widely used to investigate virus evolution, serotype identification, and pathogenesis in addition to its potential use in the diagnosis and vaccine development against coxsackieviruses [

8,

9]. Using intraperitoneal or

per os routes of infection, several studies demonstrated that CVB3 wild type and pathogenic strains replicate in mice model host and induce murine diseases, which mimic those in humans [

10,

11]. The experimental intraperitoneal Balb/c mice model was useful for the study of CVB3 pathogenesis although the natural route of CVB3 infection in human is the oral one.

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are complex nanostructures that mimic the structure of infectious viruses but lack genetic material. These particles self-assemble from multiple proteins to replicate the conformation of authentic viruses [

12,

13]. VLP-based vaccines, such as those for human papillomavirus (HPV) [

14,

15] and hepatitis B virus (HBV) [

16], have demonstrated exceptional safety and efficacy, making VLP-based vaccine technology an appealing approach for the prevention of enterovirus infections. Traditional vaccine technologies have limitations, especially in terms of production efficacy and safety [

17,

18]. However, VLP technology can be applied more broadly than traditional technologies including viruses that do not grow in cell cultures. Although VLP structurally resemble native viruses, they are incapable of replicating owing to the lack of a genetic material making them safer than traditional vaccines. Recently, self-assembled peptides have attracted considerable attention for their ease of synthesis, excellent biocompatibility, tunable structural design and the ability to form highly ordered architectures. These peptides have found wide application in biomedical and material sciences and are increasingly recognized as a promising platforms for the development of vaccines [

19,

20].

Although vaccination against coxsackieviruses and especially CVB3 serotype could reduce the incidence and the severity of acute and chronic human cardiac and pancreas diseases caused by this virus, there is currently no therapeutic drugs or vaccines to be used as clinical therapeutic or prophylactic. In the current study, we report our contribution towards the design and the development of a VP1 self-assembled VLP-based vaccine. Our results highlighted the protective humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by the intraperitoneal administration of the vaccine candidate in Balb/c mice model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice Experiments Ethics

The mice model study of the present study has been carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the King Faisal University Committee of Ethics (Deanship of Scientific Research KFU-DSR) as described in the DSR-Ethics guide for animal experimentations (Agreement# KFU-REC-OCT-ETHICS247). The Ethics Committee supervised the protocol. All mice experiments were conducted making efforts to minimize suffering Balb/c mice during anesthesia and blood collection. Balb/c mice bred in the college of science animal facility. All described mice experiments complied with the recommendations of the Committee of Ethics of the DSR. The Ethics Committee approved and supervised the designed protocol.

2.2. Cells, Media and CVB3 Virus Strains

HEK293T cells (ATCC CRL-11268) were cultured in MEM (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 7% of FCS (Invitrogen), 1% L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 µg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen), 25 UI/mL of penicillin (Invitrogen), 1% non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen) and 0.1% of Amphotericin B (Invitrogen) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO

2 at 37 °C. Supernatants were collected few days after inoculation, clarified by centrifugation and divided into aliquot stocks and stored at -80 °C until using. For VLP production in eucaryotic system, Sf9 insect cells (

Spodoptera frugiperda, ATCC CRL-1711) were cultured in suspension and grown at a non-humidified shaker at 28 °C in TC-100 Insect Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen), 10,000 UI/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen), 50 mg/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), 25 UI/mL Amphotericin (Invitrogen). The two cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cardiopathogenic CVB3/Nancy wild type and the myocardic CVB3/20 strains were kindly provided by Professor Steven Tracy from the Enterovirology laboratory, College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC, Omaha, NE, USA) were propaged and maintained on HEK293T cell cultures. Virus titers were determined using the limiting dilution assays for 50% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID

50) according to Reed & Muench assay [

21].

2.3. Generation, Purification and Characterization of the Self-Assembled VP1 of CVB3

The baculoviral transfer vector pFastBac1 (Invitrogen) containing the total gene encoding the CVB3 Nancy wild type VP1 capsid protein, previously cloned was used in this study. Generation of VLP-based VP1 self-assembled viral protein was conducted using the Bac-to-Bac vector system from recombinant baculovirus cultured in Sf9 infected insect cells (Invitrogen). Briefly, Sf9 cells cultured in media without FCS at 30 °C were co-infected with recombinant baculoviruses containing the total gene of the CVB3 VP1 capsid protein. Cell supernatants expressing VLP generated by self-assembled VP1 protein were collected and purified successively by centrifugation at 5000 x g for 20 min and by ultracentrifugation at at 200,000 x g for 60 min using discontinuous sucrose gradients with SW55 Ti Swinging-Bucket Rotor (Backman Coulter). Ultracentrifugation products collected and purified with ion-exchange chromatography, using Sepharose High Performance (HiLoad™ Q, Cytiva) and Sepharose XL (HiTrap Q, Cytiva) columns for impurities remove. Final concentrated VLP preparations were mixed and stored in 100 µL TBS Buffer at -80 °C. Structural integrity and purity of the ultracentrifuged and purified CVB3 VLP were analyzed using multiple biochemical and biophysical assays. Generated VLP were first charcterized by runing on 12% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad) and then analyzed by WB (Western Blotting, Bio-Rad), using the mouse monoclonal antibody mAb anti-enterovirus VP1 (clone 5-D8/1, Dako) at dilution of 1:4000, followed by incubation with a secondary goat antibody coupled to AlexaFluor 488 against mouse immunoglobulins (Dako) diluted at 1:15,000. Stained Sf9 infected cells were daily examined using immunofluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio, Imager 2). Morphological characterization of generated VLP was performed with Talos F200C TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy, Thermo Fisher). Purity of VLP was evaluated by residual dsDNA content quantification using the Quant-iT dsDNA high-sensitivity kit (Thermo Fisher) and by detection of residual baculovirus particles using mouse monoclonal antibody anti-gp64 mAb (Dako) diluted at 1:2000, followed by an IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG as a secondary antibody (Dako) diluted at 1:40,000.

2.4. Balb/c Mice Immunization Design and Challenge Strategies

Four-weeks-old female Balb/c mice were treated according to the general ethic rules of KFU-DSR ethical committee and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions with unlimited access to food and water. Balb/c mice were monitored daily for body weight, clinical signs and mortality. Mice were divided randomly into 8 groups (G1 to G8), each group with 6 mice (n=6). Group 1 and Group 2 Balb/c mice received a prime intraperitoneal inoculation with 12 µg of VP1 self-assembled based vaccine at day 0, then challenged successively at week 4 with 3.2 x 105 TCID50 of CVB3 wild type and 1.28 x 105 TCID50 of CVB3/20 strains. Group 3 and Group 4 Balb/c mice received first a prime-boost regimen at day 0 and week 3 with 12 µg of VP1 self-assembled based vaccine, then challenged at week 4 successively with the same doses of CVB3 wild type and CVB3/20 strains. Balb/c mice belonging to Group 5 received just a prime regimen at day 0 with 12 µg of VP1 self-assembled based vaccine. However, Group 6 and Group 7 Balb/c mice were used as positive control. mice of these groups were inoculated intraperitoneally by PBS at days 0 and week 3, then challenged at week 4 respectively with CVB3 wild type and CVB3/20 strains with the same dose mentionned above. Group 8 Balb/c mice represents the negative control group. It regroups the naive control non-infected mice receiving a prime inoculation with PBS.

Heart and pancreas organs were collected from euthanasized mice at the end of the study (Week 6). Organ tissues were rinsed with PBS and stored at -80 °C in liquid nitrogen for virus titration assays. At weeks 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 post prime-inoculation, bloods were collected from mice tails for specific neutralizing antibody and cytokine interferon gamma (INF-γ) quantification assays. However, at week 6 (The end of study), blood samples from mice were collected during the final euthanasia directly from the mice hearts and not from tails.

2.5. Neutralizing Antibody Titration Assay

HEK293T cells were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates at 6 x 10

3 cells/well with 50 µL of MEM supplemented with 7% of FCS, 1% L-glutamine, 50 µg/mL of streptomycin, 25 UI/mL of penicillin, 1% non-essential amino acids and 0.1% of Amphotericin B. Cells were then incubated for 16 to 20 h at 37 °C in humidified incubator with 5% CO

2. Serum samples derived from immunized Balb/c mice were first inactivated for 30 min at 56 °C, then diluted at serial two-fold dilutions with bovine serum albumin (BSA). The titrations of specific neutralizing antibodies present in serum samples were quantified by the micro-neutralization assay based on cell viability in HEK293T cells as described previously [

22]. Briefly, 50 µL of two-fold serial serum dilutions were incubated, respectively with 50 μl of 100 TCID

50 CVB3 wild type or CVB3/20 strains at 37 °C for 1h, followed by the addition of HEK293T cells (concentration of 6 × 10

3 cells/well). After 46h of incubation at 37 °C, cell viability was determined with alamar-blue reagent. Neutralizing antibodies were determined by calculating IC

50 (Inhibition Concentration) titers from sample-specific neutralization curves. Neutralizing antibody titer is the highest dilution of serum that inhibited the CPE (cytopathic effect) of the virus strain.

2.6. IFN-γ Concentration Assay

Sera from immunized and challenged Balb/c mice groups and from naive non-inoculated Balb/c mice group G1 to G8 were collected at weeks 1 to 6 after the prime immunization. IFN-γ concentrations were evaluated by ELISA assay, using a murine IFN-γ platinum ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher) as described previously [

22].

2.7. Viral Titration in Mice Organ Tissues by TCID Assay

Heart and pancreas tissue portions from Balb/c mice euthanasized at week 6 were removed from animal and rinsed with PBS. Snap-frozen tissues were weighted, crushed using a tissue

homogenizer (Qiagen), centrifugated at 2,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C and homogenated in PBS with 1% antibiotics (penecillin and streptomycin) and stored at -80 °C in liquid nitrogen for virus titrations. HEK293T cells were used as a propagation system for growth of the viral strains. HEK293T cells were seeded at 3 × 10

6 on a six-well plate in MEM (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 7% of FCS (Invitrogen), 1% L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 50 µg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen), 25 UI/mL of penicillin (Invitrogen), 1% non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen) and 0.1% of Amphotericin B (Invitrogen) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO

2 at 37 °C for 24 to 48 h until 90% confluence.

Viral supernatants from centrifuged snap-frozen mice tissues were inoculated to HEK293T cells. Cultures were then daily examined by light microscope for the enterovirus cytopathic effect (CPE) until day 7 post infection. Virus titers were determined by the Reed and Muench assay [

21] and expressed as TCID

50 by mg tissue values. Blind passages were systematically performed for negative samples and non-infected HEK293T cells cultures were used as negative control.

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical and Biophysical Characterization of the Self-Assembled Recombinant VP1 Protein

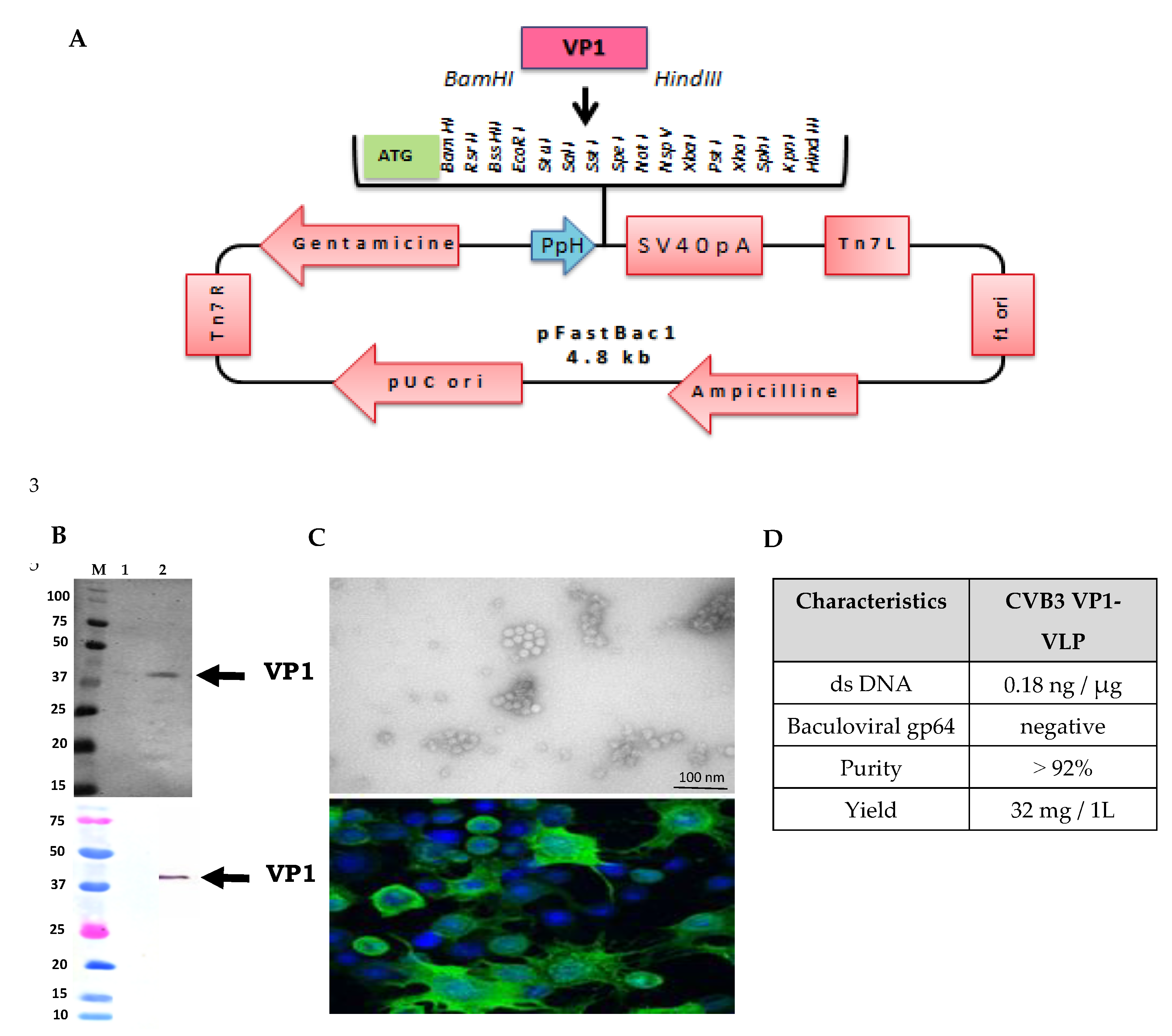

The recombinant self-assembled major viral protein VP1 of CVB3 wild type strain, forming VLP particles was produced and purified using the Bac-to-Bac recombinant baculovirus system as described in the Materials and Methods section. The baculoviral transfer vector pFastBac1 (Invitrogen) contained expression cassette of the CVB3 VP1 protein (under the strong polyhedron promoter PpH) (

Figure 1A). Recombinant baculoviruses were amplified in Sf9 (

Spodoptera frugiperda) insect cells. CVB3 VP1-VLP were expressed in Sf9 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 TCID

50/cell. Three days post infection, culture supernatants containing VP1-VLP were ultracentrifuged, collected and purified as described in the Methods section. Purified VP1-VLP were characterized by SDS-PAGE, Western blot (WB), Immunofluorescence (IF) staining and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Results of the SDS-PAGE assay revealed that the molecular weight (MW) of the produced recombinant viral protein rVP1 matched with the theoretical prediction witch is equal to 33 kD (

Figure 1B). Using the WB method, self-assembled VP1-VLP produced particles were recognized by the 5D-8/1 mAb (Dako) prepared against enterovirus VP1 viral protein, matching with the same MW (

Figure 1B). TEM examination of purified VLP demonstrated that generated particles were intacts and with the expected spherical shape capsid reassembling to the native CVB3 strain particles with a diameter approximately of 25 nm as seen in the TEM micrograph presented in

Figure 1B.

For further additional quality assessments of generated VP1-VLP particles, we evaluated the purity of particle stocks by residual dsDNA content quantification and by the detection of residual baculovirus particles. Results confirmed the absence of residual dsDNA contaminants deriving from the cell culture production processes. Results demonstrated that residual dsDNA level was 0.18 ng/μg, that is considered acceptable (acceptation limit is 10 μg/dose) according to a previously study [

23]. In addition, the detection by the mAb directed against baculoviral gp64 protein in WB assay were negative. The yield of VP1-VLP was evaluated at 32 mg/1L and the purity was at more than 92% (

Figure 1D). Our results confirmed that the generated CVB3 VP1-VLP stock is pure, with a sufficient quantity, free of baculoviral gp64 glycoprotein and with residual dsDNA level that fit well within acceptable limits to be useful for further immunization experiments in Balb/c mice model.

3.2. Neutralizing Antibodies and IFN-γ Cytokine Responses Induced by Self-Assembled CVB3 VP1-VLP Immunization in Balb/c Mice Model

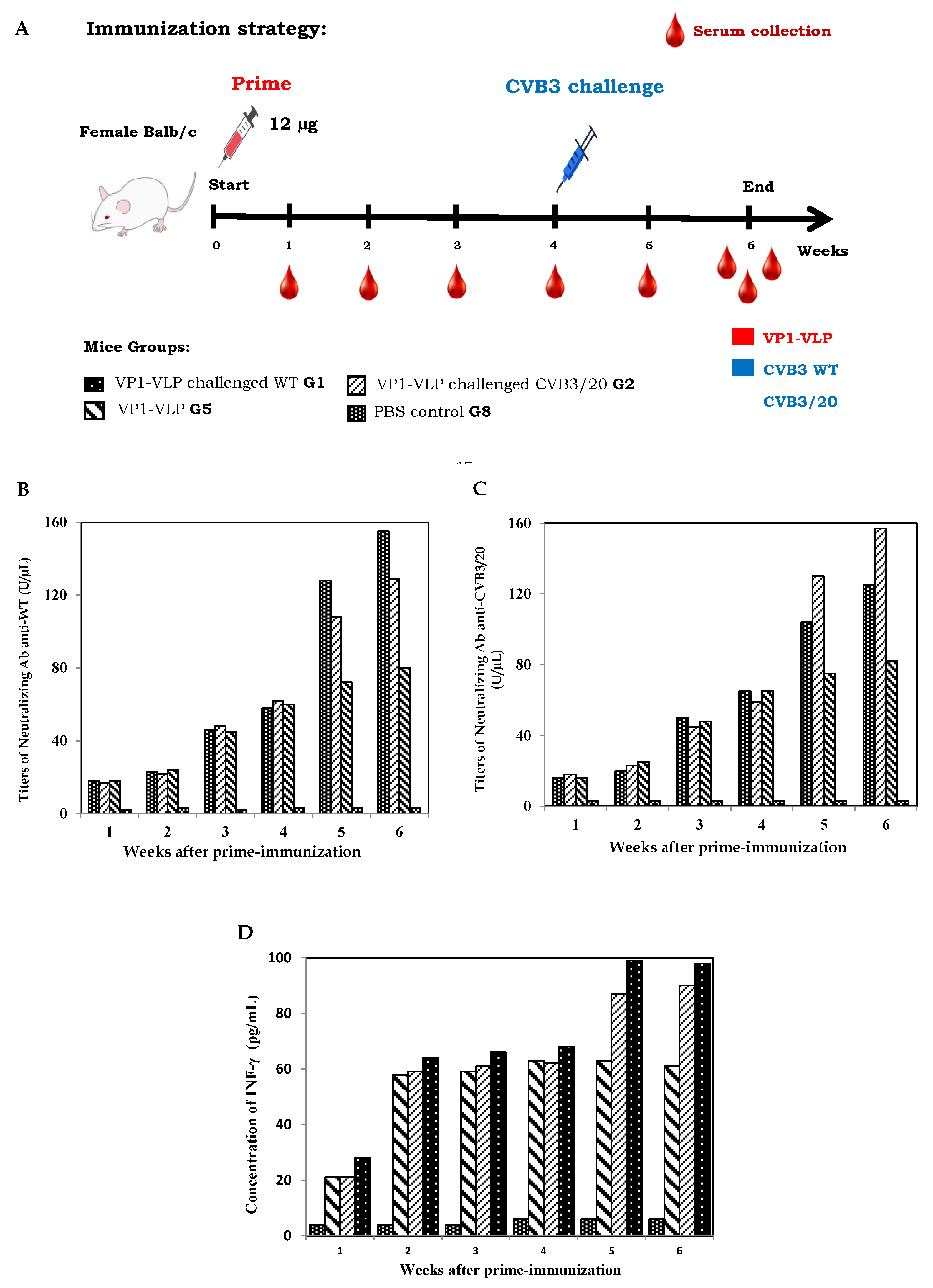

To investigate wether the generated self-assembled CVB3 VP1-VLP vaccine candidate

can induce a humoral and cellular response in vivo using a BALB/c mouse model, we evaluated first the titers of specific neutralizing antibodies and the concentrations of IFN-γ in sera of groups 1, 2, 5 and 8 (G1, G2, G5 and G8) from week 1 to week 6 (

Figure 2A). Mice groups G1 and G2 were immunized intraperitoneally at day 0 with 12 µg of purified vaccine particles VP1-VLP candidate and then challenged successively at week 4 with CVB3 wild type (WT) and CVB3/20 strains. Mice group G5 were not challenged with virus strains as mentioned in Materials & Methods section. Mice group G8 control naive mice were however injected with PBS. Specific neutralizing Ab anti-WT and anti-CVB3/20 titer changes and concentrations of IFN-γ were examined and calculated in mice group sera at weeks 1 to 6.

As shown in

Figure 2B and

Figure 2C, results showed that the neutralizing Ab targeting the VP1 protein titers of all immunized mice groups except the naive control group 8 (G8) exhibited a significant increase progressively after prime vaccination with VP1-VLP for both assays (Neutralizing Ab anti-WT and anti-CVB3/20). Interestingly, the level of produced neutralizing Ab (in U/µL) in sera of mice groups challenged at week 4 by CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 (G2 and G3) exhibeted a remarkable increase revealed at weeks 5 and 6 post prime-immunization due to the challenge with WT and CVB3/20 strains.

In addition, when studying the production of IFN-γ using mice group sera, results presented in

Figure 2D showed clearly that the IFN-γ concentrations (in pg/mL) among the different immunizated mice groups (G1, G2 and G5) increased significantly in comparison with the naive control mice group (G8). In the same way, IFN-γ levels revealed an important increasing in concentration between 68% and 72% at weeks 5 and 6 post prime-immunization for mice groups challenged at week 4 by CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 (G2 and G3). The evaluation of neutralizing Ab and IFN-γ concentrations in sera of the different studied mice groups demonstrated that a single dose immunization with the self-assembled VP1-VLP vaccine candidate could induce an effective humoral and cellular immune responses in Balb/c mice model.

3.3. Balb/c Mice Protection Against CVB3 Lethal Challenges by the Self-Assembled VP1-VLP Vaccination

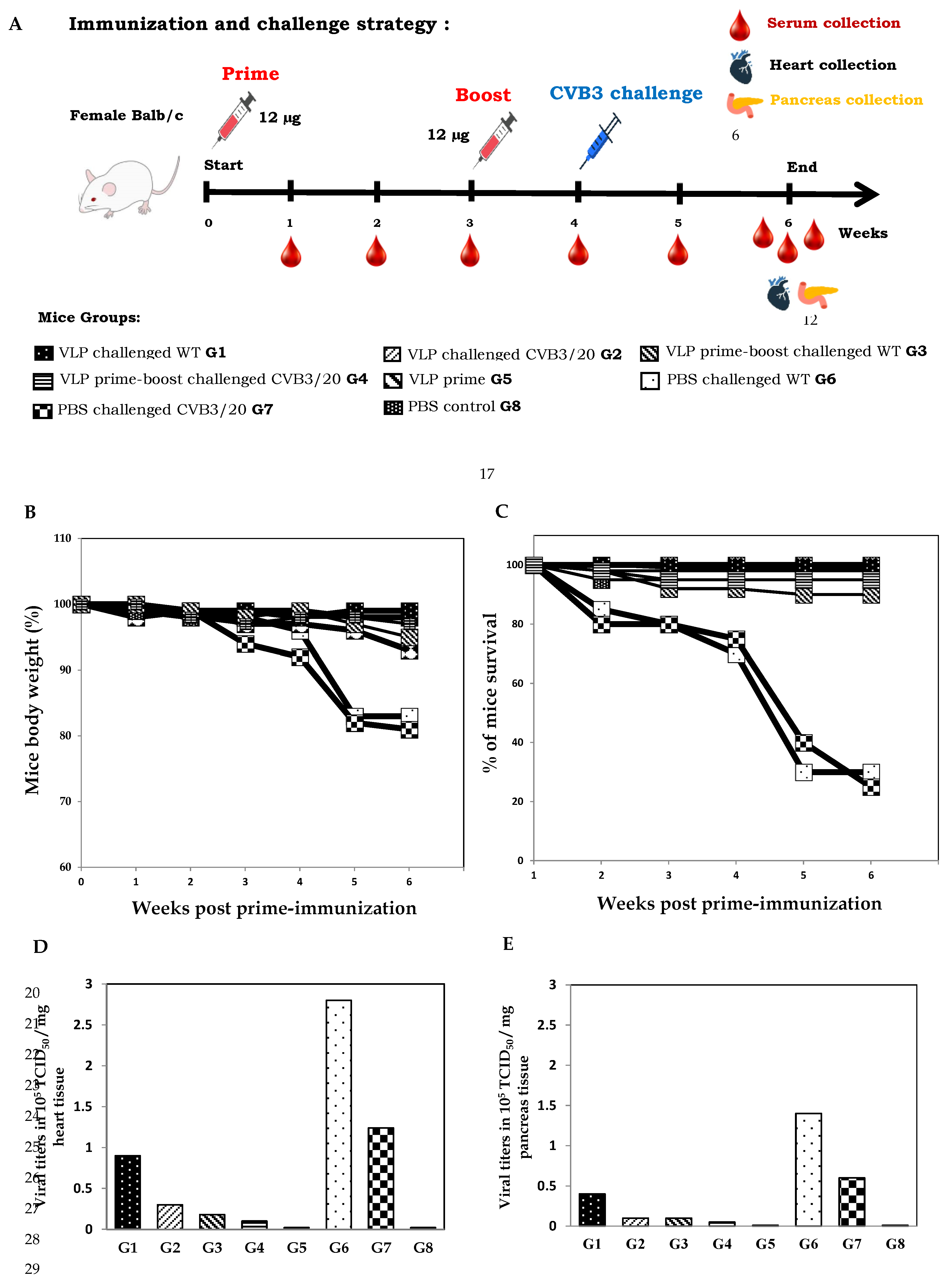

We evaluated the immunogenicity of the CVB3 VP1-VLP vaccine candidate and determined whether an immunization boost with the self-assembled viral protein VP1 protected mice or not from virus challenges with WT and CVB3/20 pathogenic strains. The adopted immunization strategy presented in

Figure 3A. Balb/c mice groups 3 and 4 (G3 and G4) were immunized with 12-μg dose of vaccine candidate twice at day 0 and week 3. Mice groups were, then successively challenged with pathogenic CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains at week 4-post prime-immunization. Groups 6 and 7 (G6 and G7) served as control non-immunized and non-boosted mice groups. However, both groups G6 and G7 were challenged at week 4 with pathogenic virus strains. Mice groups G1, G2, G5 and G8 were subjected to the same immunization strategy described in section 3.2.

All Balb/c mice groups were monitored daily during the study period (from day 0 to week 6) for disease clinical signs, body weight changes (

Figure 3B) and mortality (

Figure 3C). Decreasing in body weight and mortality was used as an indicator for viral severity infection. Following viral challenge, average body weights of mice groups G6 and G7 declined substantially by weeks 5 and 6 post-immunization with only PBS which correspond to weeks 1 and 2 post-challenge. However, Mice of G6 and G7 rapidly lost considerably weight (more than 18%), due to the evolution of virus infection, making the animals feel sick and eat less. Mice G5 receiving prime dose vaccination without any challenge showed moderate weight loss less than 5% in body weight. No significant loss in body weight was observed for mice groups G1 to G4 prime-immunized or prime boost immunized with vaccine candidate. Control PBS group mice belonging to group G8 and prime-immunized group G5 mice non-challenged maintained their weights (

Figure 3B).

Due to severe clinical signs and the rapid evolution of diseases within some mice groups, we noted during the study the death of some mice. The percentage of mice survival was variable among the different mice groups, receiving or not lethal doses of CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains. Mice groups G1 and G2 prime-immunized and then challenged successively with the WT lethal dose of 3.2 x 10

5 TICD

50 and with CVB3/20 lethal dose of 1.28 x 10

5 TICD

50 demonstrated a protective efficacy of 90%. However, mice groups G3 and G4 prime-boosted with vaccine dose and challenged with lethal doses of CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains showed in contrast a protective efficacy of 100%. The naive mice groups G6 and G7 challenged successively with lethal doses of CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains and prime-boosted with PBS revealed a protective efficacy of only 22%, demonstrating the most elevated percentage of mortality at weeks 5 and 6 post-prime-immunization. However, naive PBS control mice groups G5 and G8 showed no significant mortality during the studied period (

Figure 3C).

In order to correlate the percentage of mice mortality with the pathogenic viral replication in mice, we evaluated the viral loads in heart and pancreas organ tissues of all mice groups at week 6 post-first immunization. All survival mice were euthanized at the end of the study. Hearts and pancreas organ portions were collected and CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 titers were calculated seperately on HEK293T cell cultures, using the Reed and Muench assay. The viral titers were quantified by the tissue culture infectious doses in a given weight of organ tissues (TCID

50/mg of tissues).

Figure 3D and

Figure 3E present the viral yields successively in heart and pancreas tissues of all Balb/c mice groups G1 to G8. Interestingly, The viral loads in both heart and pancreas tissues among mice groups G3 and G4 prime-boosted with vaccine candidate then challenged with pathogenic CVB3 strains were significantly lower than among mice groups G1 and G2 prime-immunized with VP1-VLP vaccine candidate and challenged with CVB3 strains. Indeed, viral titers in mice groups G3 and G4 showed a substantial reduction successively of 25% and 72% compared to thoses in G1-G2 and G6-G7 mice groups, demonstrating that the boost immunization with VP1-VLP vaccine candidate at week 3 could enhance the protective immune responses elucited by the vaccine candidate and protect Balb/c mice from the viral lethal challenges. As expected, the viral titers of CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains in the naive challenged mice G6-G7 groups was considerably high.

4. Discussion

Vaccines have been effectively used since many times to reduce the incidence of viral infectious diseases. Recently, several technological advances have led to the conception of new generations of vaccines that they are developed in the last period. VLP are a form of subunit vaccines consisting of one or more viral structural proteins. VLP-based vaccines are considered as safer, more stable and immunogenic than conventional vaccines. A wide range of expression systems were utilized to generate VLP-based vaccines, including bacteria, yeast, baculovirus/insect cells, plants, and mammalian cells without the need of propagating pathogenic viruses [

23,

24]. Some vaccines based on VLP against various infectious pathogens (such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B) have already been licensed for human use and are available in the commercial market. Expression and self-assembled of the viral structural proteins, generating VLP can take place in various living cell expression systems after which the viral structures can be assembled and reconstructed. These self-assembled viral proteins are highly immunogenic and are able to elicit both the antibody- and cell-mediated immune responses by pathways different from those elicited by conventional inactivated or live-attenuated viral vaccines [

25].

CVB3, belonging to the family of

Picornaviridae and the genus of

Enterovirus is a ubiquitous infection agent that infects many organs from the human body systems [

1,

2,

3]. The association of CVB3 with heart diseases and type 1 diabetes (T1D) is evident. Several studies demonstrated that CVB3 is the most common cause of acute viral pancreatitis, myocarditis and chronic cardiomyopathy (CMD). The mode of contamination of CVB3 strains is mainly the fecal oral route (digestive tract). Natural infection in humans and experimental infection in mice (intraperitoneal route) provoke the synthesis of both neutralizing antibodies and interferon gamma cytokine detected in the serum (systemic antibodies). Viral capsid protein 1 (VP1) is the most exposed and contains major neutralization epitopes. Several studies have shown the potential of this viral protein VP1 in both the diagnosis developing assays and vaccine design against enteroviruses [

26].

In the present study, we have generated and characterized VLP particles issued by the expression of the recombinant self-assembled viral protein VP1 of CVB3 wild type strain using the well known Bac-to-Bac recombinant baculovirus system cultured in Sf9 insect cells. We have shown that the generated VP1-VLP were stable and highly purified by ultracentrifugation and ion exchange chromatography. When examined by several biochemical and biophysical methods (SDS–PAGE, WB and TEM), The generated VP1-VLP were indistinguishable from the CVB3 native virus in size, morphology, composition and appearance. Additional quality assessments confirmed that the generated CVB3 VP1-VLP stocks are pure, with a sufficient yield, free of baculoviral gp64 glycoprotein and residual dsDNA. Results of quality control fitted well with acceptable limits, encouraging us to conduct mice immunization experiments using the generated VP1-VLP as vaccine candidate.

In Balb/c mice model, the lethal challenge assays with 2 different pathogenic CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains were used to evaluate the immune humoral and cellular responses. Using different strategies of immunization and lethal challenges, we demonstrated that immunization with CVB3 VP1-VLP could effectively induce the synthesis of specific neutralizing antibodies against both virus pathogenic strains and the production of IFN-γ cytokine. Interestingly, the antibodies anti-VP1 collected from the different mice groups sera raised by VLP-VP1 prime or prime-boost immunization exhibited a strong neutralizing capacity against both CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 strains. Titers of specific neutralizing antibodies anti-CVB3 WT and anti-CVB3/20 increased progressively after prime-boost regimen and notably after challenges with pathogenic strains. Results of the specific humoral responses in the present study are very similar to several previous studies showing the same efficacy of enteroviral VLP as immunogens [

27,

28,

29]. In our study, we evaluated the effect of the prime-boost regimen of immunization whereas in other studies, researchers used adjuvants. We demonstrated that specific neutralizing antibody titers and IFN-γ cytokine concentrations were increased without using any adjuvant, thus enhancing both the humoral and cellular immune responses. In parallel of these studies, we have evaluated the immunized and challenged mice groups body weight changes and the percentage of survival mice. Our results demonstrated that the body weight loss among PBS control mice and challenged with CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 pathogenic strains was significant, making animals feel sick and eat less. No body weight change was observed in prime-boost immunized and challenged mice groups compared to naive control mice group. In addition, we have examined the survival rates of the different studied mice groups, our results revealed that the prime-boost immunized and challenged mice groups demonstrated a protective efficacy of 100%. However, a notable death rates was observed among mice groups not immunized and challenged with CVB3 WT and CVB3/20 pathogenic strains. Taken together, our results suggest that the prime-immunization and particularly the prime-boost immunization with the self-assembled generated VP1-VLP could protect Balb/c mice against lethal challenges with the two tested pathogenic strains CVB3 WT and CVB3/20.

5. Conclusion

Several vaccines against enterovirus serotypes have been developed and studied in animal models and human clinical trials and have yielded promising results. However, such success in the development of a CVB3 vaccine have not been made to date. Our present study presents results of the design and the production of an effective and protective vaccine candidate for CVB3 infections based in self-assembled VP1-VLP protein. We highlighted in this study the efficacy of the designed vaccine candidate to induce a immune response and protect Balb/c mice against lethal challenges, making it as a potential vaccine candidate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.; M.A.A. and M.B.M.; Methodology, I.H.H.; M.H. and M.B.M; Writing, I.H.H; M.H.; M.A.A.; M.B.M and J.G.; Funding Acquisition, M.B.M. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research DSR, Vice-Presidency of Graduated Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University (Grant # ……).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol in this work has been carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations of the Committee of Ethics of the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Faisal University (DSR, KFU) described in their guide for the use of experimentations with animal models (Agreement KFU-REC-ETHICS247). Animal experiences were conducted making all efforts to minimize suffering animals during anesthesia. Mice controls were bred in the KFU (College of science) animal facility.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research DSR, Vice-Presidency of Graduated Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University.

Conflicts of Interest

The manuscript is an original work and has not been published or is under consideration for publication in another journal. The study complies with current ethical consideration. We confirm that all the listed authors have participated actively in the study, and have seen and approved the submitted manuscript. The authors do not have any possible conflicts of interest.

References

- Norris, J.M.; Dorman, J.S.; Rezers, M.; Porte, R.E. The epidemiology and genetics of insulindependent diabetes mellitus. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1987, 111, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karvonen, M.; Viik-Kajander, M.; Moltchanova, E.; Libman, I.; LaPorte, R.; Tuomilehto, J. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (Dia Mond) project Group. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyôty, H. Enterovirus infections and type 1 diabetes. Ann. Med. 2002, 34, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadj Hassine, I.; Gharbi, J.; Hamrita, B.; Almalki, M.; Rodriguez, J.F.; Ben M’hadheb, M. Characterization of Coxsackievirus B4 virus-like particles VLP produced by the recombinant baculovirus-insect cell system expressing the major capsid protein. Mol. Bio. Rep. 2020, 47, 2853–2843. [Google Scholar]

- Plevka, P.; Perera, R.; Cardosa, J.; Kuhn, R-J.; Rossmann, M-G. Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science 2012, 336, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muckelbauer, J.K.; Kremer, M.; Minor, I.; Diana, G.; Dutko, F-J.; Groarke, J.; et al. The structure of coxsackievirus B3 at 3.5 A resolution. Struct. Lond. Engl. 1993, 3, 653–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hassine, I.H.; Gharbi, J.; Hamrita, B.; Almalki, M.A.; Rodríguez, J.F.; Ben M’hadheb, M. Characterization of Coxsackievirus B4 virus-like particles VLP produced by the recombinant baculovirus-insect cell system expressing the major capsid protein. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2835–2843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acharya, R.; Fry, E.; Stuart, D.; Fox, G.; Rowlands, D.; Brown, F. The three-dimensional structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus at 2.9 Å resolution. Nature 1989, 337, 709–716. [Google Scholar]

- Oberste, M.S.; Maher, K.; Kilpatrick, D.R.; Flemister, M.R.; Brown, B.A.; Pallansch, M.A. Typing of human enteroviruses by partial sequencing of VP1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, A.; Zell, R.; Stelzner, A. DNA vaccine-mediated immune responses in Coxsackie virus B3-infected mice. Antiviral. Res. 2001, 49, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.F.; Chang, M.H.; Chiang, B.L.; Jeng, S.T. Oral immunizationof mice using transgenic tomato fruit expressing VP1 protein from enterovirus 71. Vaccine 2006, 24, 2944–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, M.O.; Zha, L.; Cabral-Miranda, G.; Bachmann, M.F. Major findings and recent advances in virus-like particle (VLP)-based vaccines. Semin. Immunol. 2017, 34, 123–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Liu, D.; Booth, G.; Gao, W.; Lu, Y. Virus-like particle engineering: from rational design to versatile applications. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kundi, M. New hepatitis B vaccine formulated with an improved adjuvant system. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2007, 6, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, J. Human papillomavirus vaccines: an updated review. Vaccines 2020, 8, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, G.M.; Noble, S. Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine (Engerix-B®). Drugs 2003, 63, 1021–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, L.C.; Hussain, Z.; Yeoh, S-F.; Koh, D.; Lee, K.S. Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus: a menace to the end game of polio eradication. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, P.L.; Caballero, M.T.; Polack, F.P. Brief history and characterization of enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2016, 23, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookstaver, M.L.; Tsai, S.J.; Bromberg, J.S.; Jewell, C.M. Improving Vaccine and Immunotherapy Design Using Biomaterials. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, E.F.; Freire Haddad, H.; Lazar, K.M.; Liu, P.Y.; Collier, J.H. Tuning Helical Peptide Nanofibers as a Sublingual Vaccine Platform for a Variety of Peptide Epitopes. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F-H.; Liu, X.; Fang, H-L.; Nan, N.; Li, Z.; Ning, N-Z.; Luo, D-Y.; Li, T.; Wang, H. VP1 of Enterovirus 71 Protects Mice Against enterovirus 71 and Coxsackievirus B3 in Lethal Challenge Experiment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2564–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBER. Guidance for Industry, Characterization and Qualification of Cell Substrates and Other Biological Materials Used in the Production of Viral Vaccines for Infectious Disease Indications. FDA; 2010 Feb.

- Tariq, H.; Batool, S.; Asif, S.; Ali, M.; Abbasi, B.H. Virus-Like Particles: Revolutionary Platforms for Developing Vaccines Against Emerging Infectious Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 4137–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Ma, X.; Sun, X.J.; Fan, J.B.; Wang, Y. Virus-like Particles as Antiviral Vaccine: Mechanism, Design, and Application. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2023, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braz Gomes, K.; Vijayanand, S.; Bagwe, P.; Menon, I.; Kale, A.; Patil, S.; Kang, S-M.; Uddin, M.N.; D’Souza, M.J. Vaccine-Induced Immunity Elicited by Microneedle Delivery of Influenza Ectodomain Matrix Protein 2 Virus-like Particle (M2e VLP)-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hassine, I.H.; Gharbi, J.; Hamrita, B.; Almalki, M.A.; Rodríguez, J.F.; Ben M’hadheb, M. Characterization of Coxsackievirus B4 Virus-like Particles VLP Produced by the Recombinant Baculovirus-Insect Cell System Expressing the Major Capsid Protein. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2835–2843. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Parham, N.J.; Zhang, F.; Aasa-Chapman, M.; Gould, E.A.; Zhang, H. Vaccination with Coxsackievirus B3 virus-like particles elicits humoral immune response and protects mice against myocarditis. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Yan, K.; Feng, Y.; Huang, X.; Ku, Z.; Cai, Y.; Liu, F.; Shi, J.; Huang, Z. A virus-like particle vaccine for Coxsackievirus A16 potently elicits neutralizing antibodies that protect mice against lethal challenge. Vaccine 2012, 30, 6642–6648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).