1. Introduction

The prevalence of ocular pathologies that include dry eye disease (DED), age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), glaucoma and other ocular conditions is on the rise, and these can lead to vision impairment or blindness. [

1,

2,

3,

4] Within the human intestine lives a highly complex ecosystem of trillions of microorganisms that are crucial in regulating host physiology and overall health. It influences metabolism, immune function and inflammatory processes. Disturbances in this complex ecosystem is linked with various systemic conditions. Emerging scientific findings demonstrate a significant link between the gut microbiota and intestinal diseases such as Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, colorectal cancer and gastric cancer as well as conditions pertaining to other organs such as liver, lungs, heart and brain including the eye. Although research in this field is still emerging and while studies are still few, studies in both animal models and human have revealed that gut microbiome is significantly associated with ocular conditions such as Sjögren syndrome (SS), uveitis, keratitis, AMD, glaucoma, DR and chalazion.[

5,

6] The exact mechanism remains unclear and is possibly due to the proposed concept of gut-eye axis.[

7,

8]. This review examines how alterations in the gut microbial ecosystem and dietary patterns contribute to ocular disease processes and evaluates the therapeutic potential of microbiota-targeted interventions in ocular disease management.

2. The Gut Microbiome and the Gut-Eye Axis: How the Microbiome Affects Ocular Health

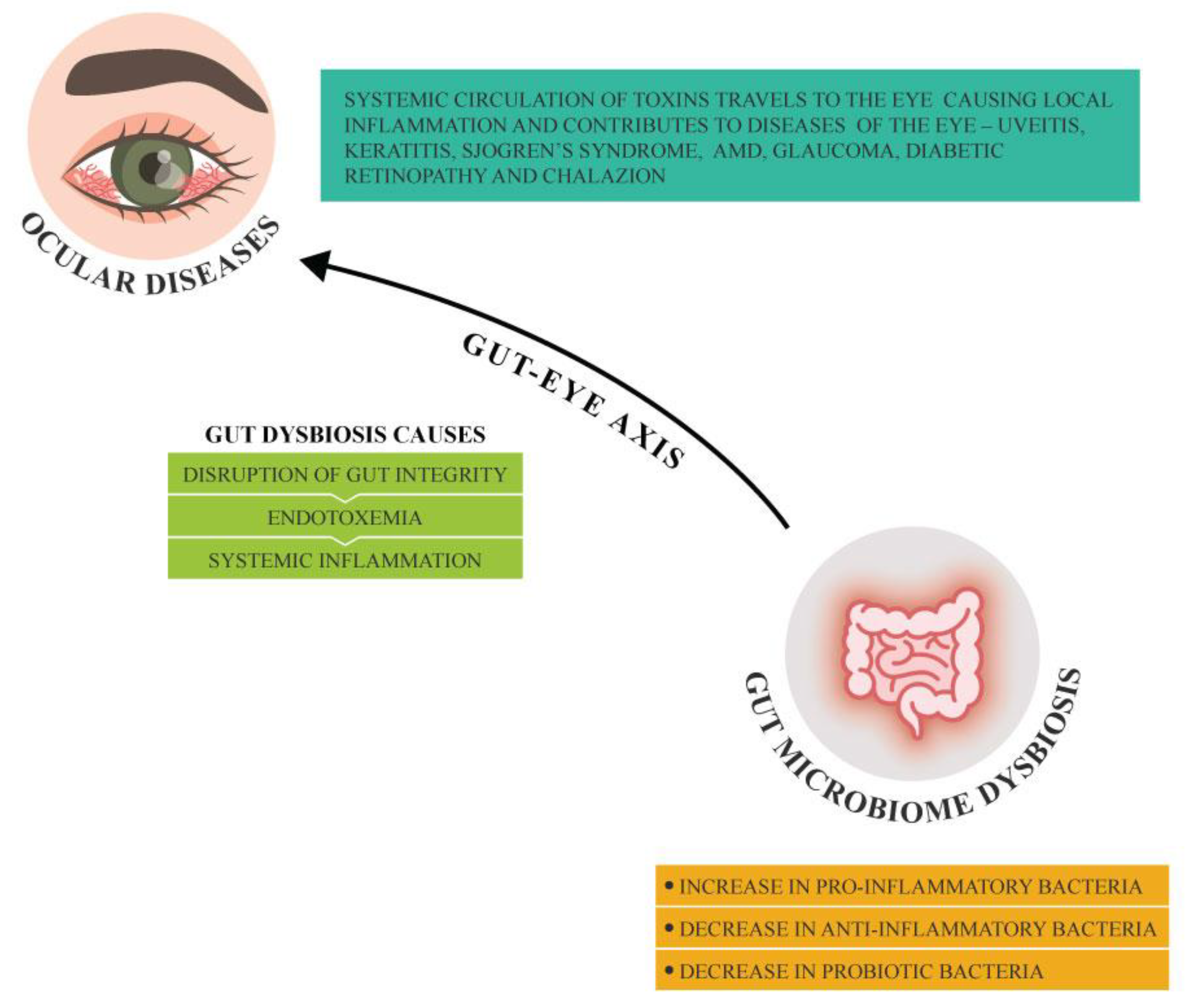

Our intestines are inhabited by largest colony of microorganisms in the body known as gut microbiota which are intrinsically linked with overall health benefits. [

7,

9] Any alteration in the gut microbiota and its metabolites known as gut dysbiosis affects the host immune system responses. An increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria in comparison to anti-inflammatory bacteria in the gut microbiota causes disruption of gut barrier integrity allowing leakage of pathogenic bacteria and its toxins from the intestinal lumen to the bloodstream leading to endotoxemia and systemic inflammation. The toxins in the systemic circulation can travel to the eye and induce ocular inflammation and can in turn exacerbate any prevailing ocular conditions.[

8] The ocular surface microbiome, the small intricate microbial community that live on conjunctiva and cornea, are involved in maintaining homeostasis and modulating immune function.[

10] An imbalance/dysbiosis in the ocular surface microbiome can be a result of infections, antibiotic use and gut microbiome dysbiosis. The imbalance in the ocular surface microbiome, the inflammation and the dysregulation of the immune system contribute to the development of ocular conditions (

Figure 1).

The gut microbiota can exert its influence in ocular diseases via various mechanisms that primarily involve metabolite production and immune balance. Gut dysbiosis results in reduced production of SCFAs, microbiome-derived metabolites such as butyrate which has an anti-inflammatory effect. This can lead to increased systemic inflammation contributing to development of ocular diseases such as uveitis and AMD. Furthermore, disrupted gut barrier function due to alterations in the gut microbiome can permit translocation of microbial endotoxin molecules including lipopolysaccharides to enter the bloodstream (the process known as endotoxemia) which in addition triggers systemic inflammation and exacerbates ocular inflammation. Lymphoid tissues that are associated with gut may also be affected by gut dysbiosis which can in addition influence systemic immune response contributing to autoimmune ocular conditions. Gut dysbiosis impacts production of cytokines and other immune mediators thereby influencing the inflammatory mechanisms involved in ocular pathology.[

8] In the eye, SCFAs can, in addition, disrupt blood-retina barrier leading to retinal vascular leakage contributing to ocular conditions. Dysbiosis increases oxidative stress leading to neurodegeneration of retinal cells. While variations in host genetics contribute to vulnerability to ocular pathologies, the gut microbiota may modify this risk through epigenetic mechanisms that influence gene expression related to inflammatory responses and oxidative stress mechanisms within the ocular microenvironment.

3. Gut Dysbiosis and Ocular Diseases: The Evidence

3.1. Dry Eye Disease (DED)

Dry eye disease refers to conditions affecting the tear film leading to dryness and visual disturbances. Studies have shown that gut microbiota shifts are evident in DED patients with more pronounced shifts noted in ones having Sjögren syndrome (SS), a prevalent autoimmune disorder causing severe dry eyes and dry mouth. Aberrations in the gut and oral microbiota is noted in these individuals.[

1,

8,

9] Studies have shown moderate decrease in alpha diversity and a significant shift in beta diversity in patients with SS in comparison with healthy control group with a decline in beneficial taxa such as

Faecalibacterium and

Bacteriodes along with enrichment of pathogenic species including

Streptococcus and

Escherichia/Shigella.[

9] Enrichment of

Prevotella has been correlated with decreased tear secretion and greater severity of dry eye.[

9] Nevertheless, the nature of association between the gut microbiota and dry eye disease remains incompletely understood and warrants further investigations .

3.2. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

AMD is a degeneration of the retina that occurs with age and can cause rapid and permanent central loss of vision and is frequently responsible for blindness in older adults. The development of this condition is influenced by factors such as diet, inflammation and genetic susceptibility. Emerging evidence from both preclinical and clinical studies indicate a connection between gut microbiota and the condition. Diet such as a high glycaemic index diet can alter gut microbiota composition and in turn affect progression of AMD. Furthermore, it was observed that when mice were put on low-glycaemic index diet, AMD was reverted. In addition, high-fat diet can alter gut microbiota and deteriorate choroidal neovascularization, a consequence of AMD. High-fat diet also increases intestinal permeability and has a pro-inflammatory effect. AMD is linked to elevated level of bacteria which are pro-inflammatory in nature such as

Anaerotruncus and

Oscillibacter;

Ruminococcus torques and

Eubacterium ventriosum while

Bacteroides eggerthii was decreased in AMD patients. Individuals with advanced AMD exhibited increased prevalence of

Prevotella.[

7,

10,

11]

3.3. Uveitis

Uveitis refers to inflammation of the middle layer of the eye known as uvea. This condition can affect individuals of all ages and might include one or both eyes leading to eye redness, pain, and blurring of vision. It is an alarming eye condition and ranks among the major causes of blindness. The main causes of uveitis include infection, injury or abnormal autoimmune responses and inflammation. Recent studies in human and animal models have noted a link between uveitis and reduced number and diversity of gut microbiota particularly reduction in beneficial bacteria involved in butyrate production and anti-inflammatory action when compared to healthy control groupsuch as

Lachnospira,

Dialister,

Dorea,

Blautia,

Clostridium,

Coprococcus,

Odoribacter,

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

Akkermansia muciniphila,

Mitsuokella,

Magasphaera and

Roseburia. Additionally microbiomes having probiotic effects such as

Ruminococcus,

Bacteroides,

Bifidobacterium adolescentis,

Oscillospira and

Veillonella dispar were reduced substantially in uveitis in comparison to healthy control group. Mice with experimental autoimmune uveitis showed increased gut abundance of

Prevotella,

Lactobacilli,

Anaeroplasma,

Parabacteroides and

Clostridium.[

7] These studies imply that gut dysbiosis can contribute or exacerbate uveitis. Furthermore, alteration of gut microbiota by antibiotics (ampicillin, metronidazole, neomycin and vancomycin) led to reduction of the severity of uveitis possibly due to increase in regulatory T cells (Tregs). Similarly, alteration of gut microbiota by administration of SCFAs reduced the severity of uveitis.[

7,

11]

3.4. Keratitis

Keratitis is an inflammatory condition of the cornea that may be associated with infection – bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic. Bacterial and fungal keratitis if not appropriately treated can become a serious condition and can result in corneal blindness. Studies have noted an imbalance in gut microbiota of individuals with bacterial keratitis when compared to healthy individuals.[

7,

12] There was an increase in pro-inflammatory bacteria while anti-inflammatory or probiotic bacteria decreased in individuals with bacterial keratitis.[

11] An increase in potentially harmful bacteria including

Prevotella copri,

Bilophila,

Enterococcus,

Bacteroides fragilis, genera CF231, and

Dysgonomonas was observed in gut microbiome of individuals with bacterial keratitis.[

11] Bacteria having anti-inflammatory effects including

Dialister,

Megasphaera,

Faecalibacterium,

Lachnospira,

Ruminococcus and

Mitsuokella and members of

Firmicutes,

Veillonellaceae,

Ruminococcaceae and

Lachnospiraceae were enriched in healthy subjects; however a decline in

Mortierella,

Rhizopus,

Kluyveromyces,

Embellisia and

Haematonectria and an enrichment of pathogenic fungi

Aspergillus and

Malassezia was noted in individuals with bacterial keratitis. .[

12] Bacteria having anti-inflammatory effects-

Megasphaera,

Ruminococcus,

Roseburia,

Lachnospira,

Acidaminococcus,

Clostridium,

Dialister,

Dorea,

Mitsuokella multacida and

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were reduced in comparison to healthy individuals whereas probiotic bacteria such as

Lactobacillus,

Bacteroides plebeius and

Bifidobacterium adolescentis were decreased with a further increase in pro-inflammatory

Shigella and

Treponema leading to exacerbation of inflammation.[

11] Similar to bacterial keratitis, fungal keratitis is associated with an increase in pro-inflammatory and pathogenic bacteria including

Enterobacteriaceae, Shigella,

Treponema and

Bacteroides fragilis production;

Shigella in particular is associated with decrease in butyrate production. Fungal keratitis also showed a decrease in

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

Megasphaera,

Mitsuokella multacida and

Lachnospira.[

7,

13]

3.5. Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a most common complication of diabetes that can lead to vision loss.[

12] Its pathogenesis, in recent studies, has been linked to gut microbiota and their metabolites and that gut microbiota could be an early diagnostic marker for diabetic retinopathy. Many studies have strongly linked gut microbiota dysbiosis with metabolic conditions such as diabetes and obesity. Individuals with DR have an altered gut microbiota in terms of diversity and abundance and changes in bacteria at the species or genus levels in comparison to healthy individuals.[

13,

14] Changes in the composition of gut microbes can trigger a low-grade chronic inflammation which can affect the onset and progression of diabetes. Increased permeability in the gut can eventually result in bacterial translocation and microbiota-derived metabolites into the blood subsequently reaching the retina and possibly altering blood–retina barrier and thus affecting the eye via the gut-retina axis and other mechanisms. [

13,

14,

15] There was reduced abundance of

Firmicutes and a high abundance of

Bacteroidetes in the DR individuals.[

14,

16] In addition, reduced SCFAs, gut microbial metabolites, have also been strongly linked with development of DR.[

13] Studies have found that individuals with DR have decreased abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria which have anti-inflammatory action.[

14] Thus, treatment aimed at restoring the gut dysbiosis in DR patients with probiotics, metabolites or FMT may offer effective therapeutic modality; however, more research is needed to fully understand the role of gut microbiota in pathogenesis, disease progression as well as treatment of DR.

3.6. Chalazion

Chalazion is an eyelid cyst caused due to clogged gland near eyelashes. Multiple factors have been linked with pathogenesis of chalaziosis and includes skin conditions, hormonal factors, immunological factors, irritable bowel disease, infectious diseases, vitamin A deficiency, high fat diet and diabetes. In addition, ocular surface microbiome dysbiosis can contribute to the pathogenesis. In a pilot study involving children with chalaziosis, it was observed that probiotics used along with medical therapy helped in complete resolution of chalazion faster than medical therapy alone possibly by restoring intestinal and immune homeostasis. Further larger well-designed studies are necessary to establish therapeutic safety and efficacy of probiotics in ocular conditions.[

17]

3.7. Glaucoma and Neurodegeneration

Glaucoma is an ocular condition characterised by damage to the optic nerve which can lead to irreversible blindness. Major contributors to glaucoma risk are older age, presence of systemic comorbidities such as metabolic and vascular diseases and genetic predisposition. One of the major risk factors includes age

and high intraocular pressure (IOP). Aging is associated with decreased bacterial diversity, fewer SCFA producing bacteria and more pathogenic bacteria that predispose older adults to inflammation and altered immune response making them susceptible to detrimental retinal health. Patients with glaucoma also have increased IOP along with increase in proinflammatory cytokines.[

18] Long term high IOP can cause mechanical damage, oxidative stress and inflammation of the optic nerve. Studies have associated glaucoma to ocular surface dysbiosis.[

19] Some studies have linked glaucoma with gut microbiota especially increase in

Bacteroides and Prevotella and shifts in gut microbiome patterns can contribute to neuroinflammation and thus pathogenesis of glaucoma. Glaucoma has also been associated with

Helicobacter pylori infections, oral conditions and long-standing low-grade inflammation caused by dysbiosis of oral microbial composition [

20] Research observed that glaucoma patients have dysbiosis in ocular surface, intraocular, oral, gastric as well as gut microbiota hence targeting the microbiota can help individuals with glaucoma.

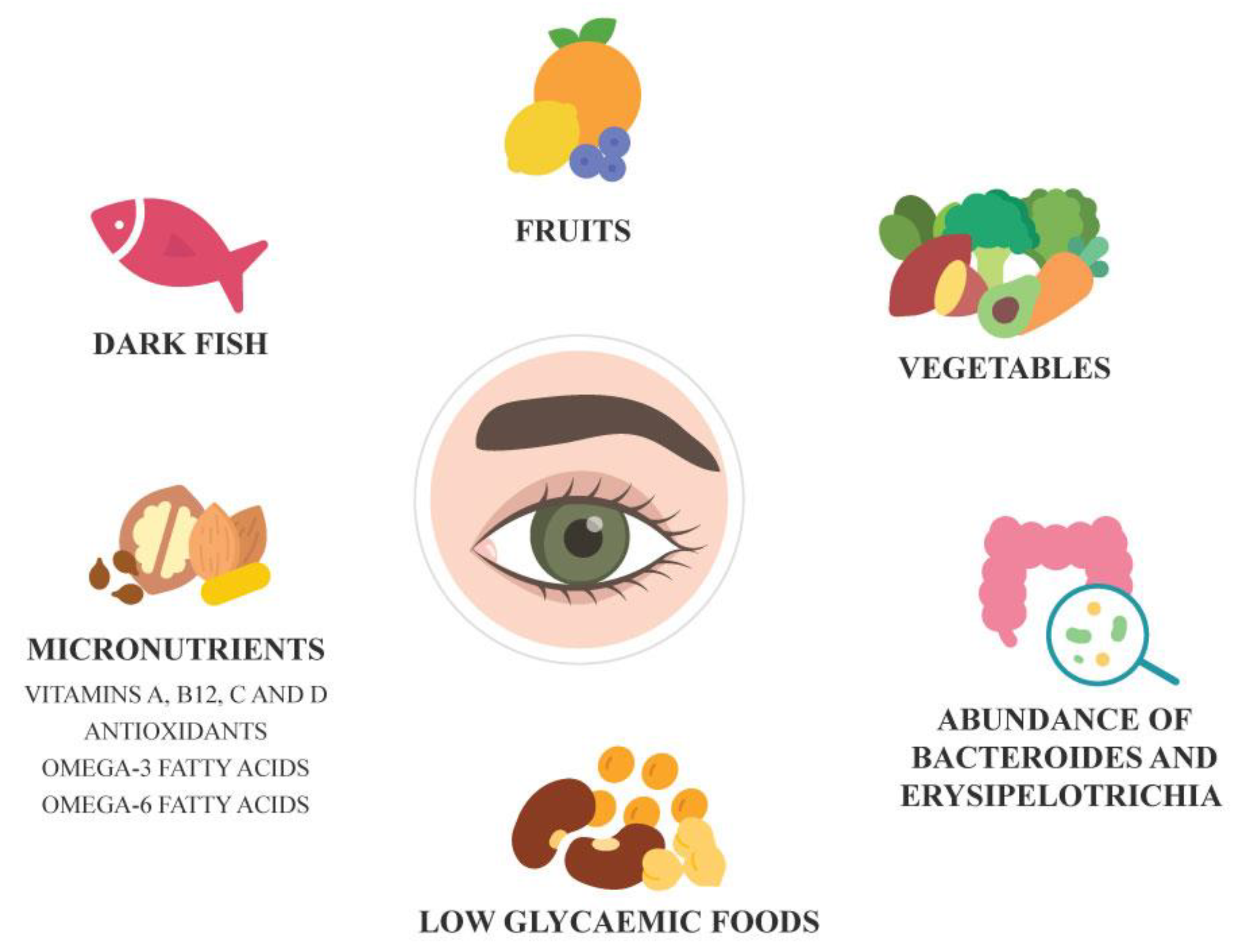

4. Diet, Microbiome, and Eye Health

Gut microbiota dysbiosis has been closely linked with inflammation and systemic diseases. Adequate nutrition is important to maintain ocular surface health. A diet rich in dark fish, fruits and vegetables and foods low in glycaemic index supports retinal health and may help prevent AMD. Conversely, poor nutrition is known to increase risk of some systemic conditions. Certain systemic conditions and pharmacological treatments can affect proper digestion and nutrient absorption causing nutritional deficiencies that can adversely impact ocular surface health. Vitamin A, B12, C and D deficiencies have been associated with ocular surface diseases. Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids appear to support ocular surface health in individuals with dry eyes and meibomian gland dysfunction.[

21,

22] Regular consumption of omega-3 fatty acids is also associated with lower risk of AMD and antioxidant treatment in AMD prevents AMD progression. Individuals with gut microbiota enriched with bacteria having antioxidant properties such as

Bacteroides and

Erysipelotrichi had lower risk of AMD.[

23] Better high-quality studies are needed to deepen our understanding of the interplay between gut microbiota, nutrition and ocular health and conditions.

Figure 2.

Dietary and Microbiome factors associated with Eye Health.

Figure 2.

Dietary and Microbiome factors associated with Eye Health.

5. The Role of Gut-Targeted Therapies in Ocular Disease Management

The gut microbiota, through its influence on many ocular inflammatory conditions, represents a potential target for developing therapeutic strategies for treatment of several ocular diseases. The gut-eye axis concept was supported in an animal model study in which interventions such as probiotics and FMT targeting the gut microbiome improved ocular signs and symptoms reinforcing the concept of gut-eye axis and its influence on ocular diseases. Probiotics, in animal studies, are observed to improve symptoms of inflammatory eye disorder symptoms, dry eye, uveitis and diabetic retinopathy.[

24,

25] Pilot studies on children with chalazion as well as adults with small chalazion have shown significant faster complete resolution of chalazion in subjects on oral probiotics with medical therapy compared to those on medical therapy alone emphasizing the influence of gut-eye axis.[

17,

26] Probiotics also reduced dry eye symptoms, uveitis and biomarkers of AMD.[

24,

25,

27] The benefits of probiotics are associated with decreased inflammation and cytokine secretion, reduced growth of pathogenic bacteria, increased SCFA production and improvement in the integrity of epithelial barrier. Symbiotics (probiotics with prebiotics) reduced uveitis, dry eye, ocular surface diseases, decreased cytokinin production, increased intestinal homeostasis and increased tear secretion.[

24,

25] A pilot study demonstrated that usage of probiotic in form of eye drops for a period of one month lead to improvement in clinical signs and symptomatic burden of vernal keratoconjunctivitis.[

28] More double-blind controlled clinical trials with a larger sample size are necessary to confirm the efficacy and safety of probiotics in treating ocular conditions.

Research has shown that FMT is highly effective and promising for treating of

C. difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease; however, studies on ocular conditions in humans are still unavailable. FMT improved ocular symptoms in germ-free mice with SS. This effect may be attributed to the protective role of the gut microbiota in SS via anti-inflammatory effects and the regulating effect on ocular immune cells bringing about a balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cells. Thus strategies to modulate gut microbiota and establish microbial balance may be an effective prevention approach for SS.[

8]

The growing evidence in favour of the significance of the gut microbiome in ocular disease pathogenesis and management necessitates further large-scale human studies across diverse populations. Advanced microbiome sequencing technologies can aid in diagnosis and deeper understanding of ocular disease diagnostics. Further investigations are essential to determine both the therapeutic efficacy and safety of microbiome-based therapies.

6. Conclusions

Recent studies have revealed significant alteration in the gut microbiome in individuals diagnosed with ocular diseases in contrast to healthy subjects emphasising the crucial role played by the gut eye axis in the onset and/or progression of ocular conditions.[

8] Current evidence suggests that

Bacteroides and

Erysipelotrichi and diets rich in dark fish, fruits and vegetables, vitamins A, B12, C and D and omega 3- and -6 fatty acids are associated with ocular health and prevention of ocular diseases and its progression. As the research is in its preliminary stage, there is a need for further longitudinal studies in heterogeneous populations to fully elucidate the precise mechanisms and identify specific biomarkers involved in ocular conditions.[

12] Moreover, gut-targeted therapeutic approaches including prebiotics, probiotics and faecal microbiota transplantation show considerable promise in restoring microbial homeostasis and improving clinical outcomes across a range of ocular diseases. However, further large-scale, multicentric longitudinal studies and advances in microbiome sequencing technologies are essential to validate these associations and refine diagnostic and therapeutic applications.[

12] A deeper understanding of the gut-eye axis offers new insights into the crucial influence of gut microbiome in ocular health and disease and supports the integration of nutrition and microbiome-targeted strategies to restore microbial balance and improve outcomes in ocular diseases.

References

- Burton, MJ; Ramke, J; Marques, AP; Bourne, RRA; Congdon, N; Jones, I; et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob Health 2021, 9, e489–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S; Ren, J; Chai, R; Yuan, S; Hao, Y. Global burden of low vision and blindness due to age-related macular degeneration from 1990 to 2021 and projections for 2050. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blindness and vision impairment. n.d. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Bourne, RRA; Steinmetz, JD; Saylan, M; Mersha, AM; Weldemariam, AH; Wondmeneh, TG; et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health 2021, 9, e144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X; Tan, H; Huang, L; Chen, W; Ren, X; Chen, D. Gut microbiota and eye diseases: a bibliometric study and visualization analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1225859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y; Chan, YK; Wong, HL; Poon, SHL; Lo, ACY; Shih, KC; et al. A Review of the Impact of Alterations in Gut Microbiome on the Immunopathogenesis of Ocular Diseases. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J; Dong, H; Wang, T; Yu, H; Yu, J; Ma, S; et al. What is the impact of microbiota on dry eye: a literature review of the gut-eye axis. BMC Ophthalmol 2024, 24, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammoun, S; Rekik, M; Dlensi, A; Aloulou, S; Smaoui, W; Sellami, S; et al. The gut-eye axis: the retinal/ocular degenerative diseases and the emergent therapeutic strategies. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18, 1468187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tîrziu, AT; Susan, M; Susan, R; Sonia, T; Harich, OO; Tudora, A; et al. From Gut to Eye: Exploring the Role of Microbiome Imbalance in Ocular Diseases. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, MW; Muste, JC; Kuo, BL; Wu, AK; Singh, RP. Clinical trials targeting the gut-microbiome to effect ocular health: a systematic review. Eye 2023, 37, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaji, S. A systematic review of gut microbiome and ocular inflammatory diseases: Are they associated? Indian J Ophthalmol 2021, 69, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, LIM; Varesi, A; Barbieri, A; Marchesi, N; Pascale, A. Targeting the Gut–Eye Axis: An Emerging Strategy to Face Ocular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y; Kang, Y. Gut microbiota and metabolites in diabetic retinopathy: Insights into pathogenesis for novel therapeutic strategies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 164, 114994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J; Wan, Z; Zhang, Y; Wang, T; Xue, Y; Peng, Q. Composition and diversity of gut microbiota in diabetic retinopathy. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 926926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, R; Asare-Bediko, B; Harbour, A; Floyd, JL; Chakraborty, D; Duan, Y; et al. Microbial Signatures in The Rodent Eyes With Retinal Dysfunction and Diabetic Retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2022, 63, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, D; Dascalu, AM; Arsene, AL; Tribus, LC; Vancea, G; Pantea Stoian, A; et al. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Diabetic Retinopathy—Current Knowledge and Future Therapeutic Targets. Life 2023, 13, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippelli, M; dell’Omo, R; Amoruso, A; Paiano, I; Pane, M; Napolitano, P; et al. Intestinal microbiome: a new target for chalaziosis treatment in children? Eur J Pediatr 2021, 180, 1293–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J; Chen, DF; Cho, KS. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Glaucoma Progression and Other Retinal Diseases. Am J Pathol 2023, 193, 1662–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L; Hong, Y; Fu, X; Tan, H; Chen, Y; Wang, Y; et al. The role of the microbiota in glaucoma. Mol Aspects Med 2023, 94, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, P; Filippelli, M; Davinelli, S; Bartollino, S; dell’Omo, R; Costagliola, C. Influence of gut microbiota on eye diseases: an overview. Ann Med 2021, 53, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoulli, M; Ahmad, S; Arcot, J; Arita, R; Benitez-del-Castillo, J; Caffery, B; et al. TFOS Lifestyle: Impact of nutrition on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf 2023, 29, 226–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, MB; Bernstein, PS; Boesze-Battaglia, K; Chew, E; Curcio, CA; Kenney, MC; et al. Inside out: Relations between the microbiome, nutrition, and eye health. Exp Eye Res 2022, 224, 109216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y; Li, Y; Gkerdi, A; Reilly, J; Tan, Z; Shu, X. Association of Nutrients, Specific Dietary Patterns, and Probiotics with Age-related Macular Degeneration. Curr Med Chem 2022, 29, 6141–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, LIM; Varesi, A; Barbieri, A; Marchesi, N; Pascale, A. Targeting the Gut–Eye Axis: An Emerging Strategy to Face Ocular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunardi, TH; Susantono, DP; Victor, AA; Sitompul, R. Atopobiosis and Dysbiosis in Ocular Diseases: Is Fecal Microbiota Transplant and Probiotics a Promising Solution? J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2021, 16, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippelli, M; dell’Omo, R; Amoruso, A; Paiano, I; Pane, M; Napolitano, P; et al. Effectiveness of oral probiotics supplementation in the treatment of adult small chalazion. Int J Ophthalmol 2022, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ria, F; Deeg, C; Reynolds, AL; Caspi, RR; Horai, R; Salvador, R; et al. Microbiota as Drivers and as Therapeutic Targets in Ocular and Tissue Specific Autoimmunity. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 8, 606751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovieno, A; Lambiase, A; Sacchetti, M; Stampachiacchiere, B; Micera, A; Bonini, S. Preliminary evidence of the efficacy of probiotic eye-drop treatment in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008, 246, 435–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).